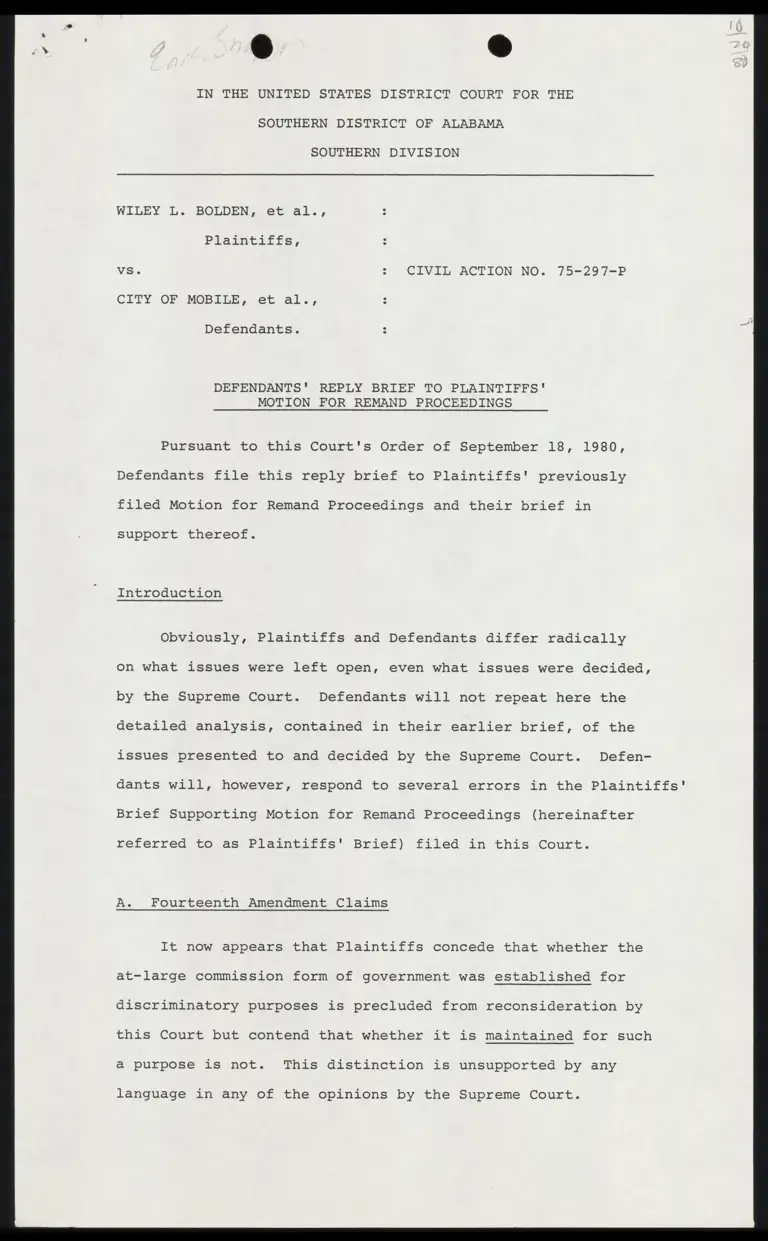

Defendants' Reply Brief to Plaintiffs' Motion for Remand Proceedings

Public Court Documents

October 24, 1980

14 pages

Cite this item

-

Case Files, Bolden v. Mobile Hardbacks and Appendices. Defendants' Reply Brief to Plaintiffs' Motion for Remand Proceedings, 1980. 5a0b1289-cdcd-ef11-8ee9-6045bddb7cb0. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/343644c3-237e-49ee-b9b6-bf1a736bc998/defendants-reply-brief-to-plaintiffs-motion-for-remand-proceedings. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE

SOUTHERN DISTRICT OF ALABAMA

SOUTHERN DIVISION

WILEY L. BOLDEN, et al.,

Plaintiffs, :

VS. CIVIL ACTION NO. 75-297~P

CITY OF MOBILE, eft al.,

Defendants.

DEFENDANTS' REPLY BRIEF TO PLAINTIFFS'

MOTION FOR REMAND PROCEEDINGS

Pursuant to this Court's Order of September 18, 1980,

Defendants file this reply brief to Plaintiffs' previously

filed Motion for Remand Proceedings and their brief in

support thereof.

Introduction

Obviously, Plaintiffs and Defendants differ radically

on what issues were left open, even what issues were decided,

by the Supreme Court. Defendants will not repeat here the

detailed analysis, contained in their earlier brief, of the

issues presented to and decided by the Supreme Court. Defen-

dants will, however, respond to several errors in the Plaintiffs’

Brief Supporting Motion for Remand Proceedings (hereinafter

referred to as Plaintiffs' Brief) filed in this Court.

A. Fourteenth Amendment Claims

It now appears that Plaintiffs concede that whether the

at-large commission form of government was established for

discriminatory purposes is precluded from reconsideration by

this Court but contend that whether it is maintained for such

a purpose is not. This distinction is unsupported by any

language in any of the opinions by the Supreme Court.

To summarize briefly, the essence of the plurality

holding is as follows. First, "Plaintiff must prove that

the disputed [electoral] plan was 'conceived or operated as

[a] purposeful device[] to further racial discrimination.'"

48 U.S.L.W. at 4439, 64 L. Ed. 24 at 58. i/ Second, "the

evidence in the present case fell far short of showing that

appellants 'conceived or operated [a] purposeful device[]

to further racial discrimination.'" 48 U.S.L.W. at 4440,

64 L. Ed. 2d at 61. Third, neither the Zimmer analysis,

the foreseeable consequences test, the lack of any elected

blacks under the system, discrimination in city services,

a history of past official racial discrimination, or the

inherent submerging effect of at-large elections could them-

selves supply the missing proof of intentional discrimination.

48 U.S.L.W. at 4440-4441, 64 L. Ed. 2d at 61-63, including

note 17. As stated by the Supreme Court this additional evidence

is "far from proof that the at-large electoral scheme represents

purposeful discrimination against Negro voters." 48 U.S.L.W.

at 4441, 64 L. Ed. 2d at 63 (emphasis added). Justice Stevens's

2/ test, of course, is even more stringent. =

Thus, the legal test adopted by the Supreme Court indicates

that an electoral plan can be challenged either as it "was

conceived" or "is operated." "Conceived" is simply another

word for "created" or "established." "Operated" has the same

meaning as the phrase "maintained" or, as it is said in Plain-

tiffs' Brief, "retained."

It is clear that the plurality holding applied to both

aspects; i.e., the plurality held that the evidence in the

1l/ The plurality added that this "burden of proof is simply

one aspect of the basic principle that only if there is purpose-

ful discrimination can there be a violation of the Equal Protec-

tion Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment." 48 U.S.L.W. at 4439,

64 L. EG. 24d at 58.

2/ In fact, a fair reading of Justice Stevens's concurrence is

that in light of the objectively neutral reasons supporting the

continued maintenance of Mobile's at-large commission government

Plaintiffs could not prove a case of liability regardless of what

additional evidence of discriminatory motive they could come up

with. 48 U.S.L..W. at 4445-46, 64 L. E4. 24 at 74-75.

case fell far short of showing that Mobile's at-large scheme

was either "conceived" or "operated" as a purposeful dis-

criminatory device. 48 U.S.L.W. at 4440, 64 L. Ed. 24 at 61.

A review of Justice Stevens's concurring opinion (the fifth

vote) shows that in reaching his opinion "that no violation

of respondents' constitutional rights has been demonstrated"

(48 U.S.L.W. at 4443, 64 1L. Ed. 24 at 69) he considered both

the questions of the original establishment and the current A

maintenance of the Mobile form of government. 48 U.S.L.W. at

4446, 64 L. Ed. 24d at 74 (decision to "retain" present form

of government cannot be invalidated by presence of some

illicit motivation).

Therefore, there is no basis for distinguishing between

the original creation and the current maintenance of the Mobile

form of government in deciding what issues, if any, are open

at this stage. As a matter of fact, if Plaintiffs were correct

that the statements by the plurality concerning the evidence

falling "far short" are nothing more that a rejection of the

Fifth Circuit's Zimmer analysis, then one issue should be

just as open as the other.

In short, Defendants adhere firmly to their position

that, based on the clear and explicit language of both the

plurality 2/ and Stevens's concurring opinion, 4/ the record

in this case does not prove a violation of Plaintiffs' con-

stitutional rights. 5/ Despite the Supreme Court holdings,

the United States as amicus curiae made the startling argu-

ment to the Fifth Circuit on remand that the evidence in

this record would support factual findings of discriminatory

3/ "[T]lhe evidence in the present case fell far short of show-

ing that the appellants 'conceived or operated [a] purposeful

device] to further racial discrimination.'" 48 U.S.L.W. at

4440, 64 L. Ed. 2d at 61 (emphasis added).

4/ "I agree with [the plurality] that no violation of respon-

dent's constitutional rights has been demonstrated . n

48 U.S.L.W. at 4443, 64 1. E44, 24 at 69.

5/ Clearly both the plurality and Justice Stevens ruled on

both the fourteenth and fifteenth amendment claims.

intent. United States Fifth Circuit Amicus Curiae Brief at

page 12. In other words, even though the four man plurality,

and Justice Stevens concurring, said that the evidence in

this case fell "far short" of making the necessary showing,

it was argued that the Fifth Circuit and this Court could

based on that same record find that the evidence did, after

all, make the necessary showing.

Recognizing the obvious unsoundness of this position,

Plaintiffs now argue to this Court that the district court

should not make such ultimate findings without first allowing

additional evidence to be added to the record. As discussed

in detail in Defendants' previous brief to this Court, Defen-

dants know of no authority allowing Plaintiffs, against whom

no error was committed by any court, such a second chance to

prove what they failed to prove at the first trial. 8

First, contrary to Plaintiffs' assertion at page 16,

the Supreme Court did not "decline[] to consider" the evidence

presented by Plaintiffs "over and beyond" Zimmer. To the

contrary, the Supreme Court considered such evidence, and

found it wanting. 48 U.S.L.W. at 4440-41, 64 L. Ed. 2d at

60-63.

Second, there is nothing "fundamentally unfair" in

limiting the Plaintiffs to one day in court, instead of

repeated opportunities if their first presentation is found

insufficient. Only one full opportunity to present one's

case is a fundamental principle of the American system of

justice.

Third, the requirement of the proof of discriminatory

purpose is not a "new intent standard." Plaintiff's Brief

at 4. To the contrary, Washington v. Davis was decided before

this case was tried. Defendants argued strenuously in their

6/ See footnote 2 supra.

pre-trial pleadings that Washington v. Davis required such

proof of intent and that Zimmer was no longer sufficient to

prove liability. Plaintiffs argued strenuously to the con-

trary, but they were wrong.

Fourth, Plaintiffs cannot claim to have been surprised

or unaware that they might have to meet the intent standard.

As indicated, Defendants argued that very point strenuously

before the case was tried.

No pre-trial or trial ruling of the district court held

that such proof was unnecessary or limited or discouraged

Plaintiffs in any way from putting in whatever evidence they

had of such discriminatory intent. Plaintiffs in fact put

on proof going to that issue at trial and, presumably, put

on all they had. In their post-trial pleadings Plaintiffs

argued strenuously, as an alternative, that they had in fact

proved discriminatory intent as required by Washington v. Davis.

They made the same alternative argument to the Fifth

Circuit. They made the same argument to the Supreme Court,

although in the Supreme Court they switched tactics and made

"we proved intent" their first argument, followed by the

alternative argument that such proof was not necessary since

proof of discriminatory effect alone was enough. In such

circumstances Plaintiffs cannot honestly claim surprise or

that they were mislead in any way or that if they had only

known they could have put on evidence of discriminatory intent

to supply what was later found missing by the Supreme Court.

Neither did the Fifth Circuit in this remand proceeding

rule as "Plaintiffs . . . had suggested" or direct this Court

to allow the Plaintiffs a further evidentiary hearing. See

Plaintiffs' Brief at 2. Rather, the Fifth Circuit, in lan-

guage almost identical to that used by the Supreme Court,

passed these questions back to this Court for initial deci-

sion. Plaintiffs' argument that the Fifth Circuit meant for

them to have a new trial to avoid an otherwise sure appeal

by the Plaintiffs is one-sided since if such a new trial is

directed by the district court Defendants will as surely

seek appellate review of that ruling as would the Plaintiffs

a contrary ruling. 74

Finally, we note that however "extreme" 8/ Justice

Stevens's opinion may seem to Plaintiffs, Justice Stevens

8/

will most likely continue to adhere to it. = Thus, regard-

less of how you attempt to explain it away, there are still

five votes for the proposition that the evidence in this

record does not prove a violation of any constitutional (four-

teenth or fifteenth amendment) rights of the Plaintiffs.

B. Fifteenth Amendment Claim

Plaintiffs appear to continue to claim that the fifteenth

amendment issue was not resolved by the Bolden decision. Defen-

dants disagree.

Clearly, the four justice plurality heard and decided

the fifteenth amendment claim. In essence they held that

Plaintiffs' vote dilution claims could not be maintained under

that amendment since the district court had found that Negros

in Mobile "register[ed] and vote[d] without hindrance." 48 U.S.L.W.

at 4438, 64 L. Ed. 2d at 57. In reaching that conclusion the

7/ Similarly unpersuasive is the contention at page 2 that the

Fifth Circuit would have reversed this court's prior judgment

if it had been persuaded by Defendants' arguments. Obviously,

it is unnecessary to, and the Fifth Circuit cannot, reverse a

judgment of this court that has already been reversed by the

Supreme Court.

8/ Plaintiffs’ Brief at 5.

9/ Recall that in the Bolden decision itself Justice Stevens

continued to adhere to his concurring position in Washington

v. Davis despite the lack so far of support by any other justice

for that concurring position. See 48 U.S.L.W. at 4446 n.l2,

64 L. EA. 2d at 74 n.l2.

plurality held "that action by a state that is racially

neutral on its face violates the fifteenth amendment only

if motivated by a discriminatory purpose." 48 U.S.L.W. at

4438, 64 L. Ed. 2d at 55 (emphasis added).

In his concurring opinion Justice Stevens adopted an

even stricter rule, a rule which he applied to both the

fourteenth and fifteenth amendment claims. This test, which

appears to require a showing that discriminatory purpose was

the sole motivation for the challenged action, is even stricter

than the test adopted by the four justice plurality, as has

been repeatedly recognized by both Plaintiffs and the United

States as amicus curiae. Thus, it is clear that at least

a five justice majority of the Supreme Court has held that

in this case Plaintiffs failed to prove discriminatory purpose

sufficient to constitute a violation of the fifteenth amendment.

Even if Defendants were deemed incorrect in their analysis

of the Supreme Court's fifteenth amendment holding, the panel

opinion in this case held that proof of discriminatory purpose

was required under the fifteenth amendment, and if the Supreme

Court did not decide the issue, then that ruling remains the

law of this case. See Bolden v. City of Mobile, 571 F.2d 238,

241 n.l (5th Cir. 1978) (incorporating parts 1 and 2 of the

opinion in Nevett v. Sides, 571 F.2d 209, 220-21, (5th Cir.

1978)).

C. Voting Rights Act Claims

It is correct as Plaintiffs contend that the Supreme

Court plurality admonished the lower courts for not follow-

ing the normal rule and deciding the statutory claims before

the constitutional claims. Such "error," however, is "harm-

less" in the circumstances of this case because the plurality

went ahead and decided that issue itself. Specifically,

the plurality held that § 2 of the Voting Rights Act con-

tained the same substantive standard for relief as the fif-

teenth amendment. 48 U.S.L.W. at 4437, 64 L. Ed. 2d at 54.

The fifteenth amendment claim having failed for lack of proof,

the Voting Rights Act claim likewise failed.

Except for Justice Marshall, no other justice discussed

the Voting Rights Act claim. Justice Marshall agreed that

the test under § 2 of the Voting Rights Act was the same as

the test under the fifteenth amendment, but he disagreed with

the plurality as to the substance of that test.

Admittedly the failure of the other four justices to

speak to the Voting Rights Act issue adds an element of con-

fusion to the decision. However, the significant point remains

this. The judgment in favor of the Plaintiffs below was

reversed on the liability issues by at least a five to four

vote. There is no legal requirement that a court in reviewing

and reversing a lower court judgment specifically Biscuss in

its opinion and rule on each and every legal theory presented

below any more than it need comment on each piece of evidence

in the record. 10/

Rather, the judgment of the court resolves all issues

presented to the court and considered by it. See authorities

discussed in paragraph II(a) of Defendants' previously filed

Brief in Support of Defendants' Motion to Enter Judgment. Since

Plaintiffs' Voting Rights Act claim was clearly presented to

the Supreme Court (see issue three stated in Plaintiffs’

Supreme Court brief), the ruling by the Supreme Court against

the Plaintiffs in reversing this Court's judgment necessarily

disposed of all claims asserted by Plaintiffs whether or not

specifically discussed by a majority of the court.

10/ The Supreme Court is not, in fact, required to write any

opinion at all.

Finally, should that point be reached in these remand

proceedings, Defendants will contend that section 2 of the

Voting Rights Act contains the same substantive standard

(a purpose or intent standard) as does the fifteenth amend-

ment. The plain language of section 2 (and its legislative

history), in contrast to the quite different "effects" language

of section 5, so provides, and four justices in Bolden so held.

Only one, Justice Marshall, and arguably a second, Justice

Brennen, disagreed.

D. Other Issues

In their brief Plaintiffs made a number of arguments

going to the "merits," raising issues which would become

involved only if further proceedings were undertaken by this

Court. Defendants do not understand that now is the time to

address such issues since the Court has indicated that if

further proceedings are warranted the "re-trial" stage would

not be reached until after the occurrence of appropriate

discovery and pre-trial proceedings. Defendants note the

following points, however, for the Court's consideration.

If the question of "discriminatory maintenance" has been

left open by the Supreme Court, a number of issues are pre-

sented concerning the exact nature of this legal question,

the type of evidence relevant to it, and the relevant time

period. For example, the question whether the Mobile city

commission form of government was established (conceived)

with the deliberate purpose of diluting black votes through

the use of the at-large election procedure is relatively

straightforward. But what is meant when the question is

asked whether that system is currently "maintained" or "operated,"

or in Plaintiffs' words "retained," for such a discriminatory

purpose?

- 10 ~

Does it mean simply that the appropriate officials,

although they have now recognized the inhibiting effect of

that system on black votes, have failed to act to change it?

Does it mean that although the appropriate officials once

had pure motives they are now deliberately refraining from

changing the systems on their own initiative, in order to

have the dilutive effect? Or does it mean that the appropriate

officials have failed to enact a change requested of them

because of such motivation?

Defendants suggest that the first alternative has already

been rejected by the Supreme Court in the Bolden opinion. See

48 U.S.L.W. at 4440 n.17, 64 L. Ed. 2d at 61-62 n.l1l7. Where

there are neutral legitimate reasons for continuing to adhere

to a system of government the failure to affirmatively act to

change that system just because the effect of that system on

black voters has become recognized does not meet the Feeney

standard of proof.

Similarly, the second approach is inconsistent with the

Washington v. Davis, Arlington Heights, Feeney standard.

There is no constitutional right to proportional representa-

tion. Hence, state officials do not have an affirmative duty

to, on their own, change an electoral system to ensure or

make easier proportional representation, even if it be assumed

that the original valid reason for that system has now dissipated

and been replaced by an illicit, hidden motivation. The con-

trary rule would create an affirmative duty on the part of the

appropriate governmental officials to continually monitor their

own hearts and, if and when illicit motivation interceded, to

affirmatively act on their own initiative to change the system

which has existed for that many years solely because of the

appearance in their heart of illicit motivation known only to

themselves.

- 11 -

Now, would the third question be the proper one? Should

the question be whether state officials have refused to act;

i.e., refused an appropriate request for action, because of

race or some other invidious motivation? This was, of course,

the situation in Village of Arlington Heights where the challenged

action was the city council's refusal to approve a zoning change

requested by the plaintiff developers in that case. In other

words, the duty not to be motivated by race in refusing a

requested change (i.e., the duty to not maintain the system

because of racial considerations) did not arise until an appro-

priate request for a change in that system was made.

These same issues become involved in consideration of

questions such as the appropriate statute of limitations to

apply and the relevant time period for evidence of motivation.

If the Alabama state legislature refuses a requested change

in the at-large system of government in 1920 because of racial

motivation, is that decision challengable in 1980? Is such

evidence even admissible in 1980? If the bare "maintenance"

of the at-large system by itself is challengable, do Plaintiffs

have to challenge the maintenance in 1976 when the case was

hp

tried or now, in 1980? —

It would seem that Plaintiffs would have to show at this

time a current purposeful discriminatory maintenance of that

system. Proof that the system had been maintained for invidious

purpose at a certain period in the past, without proof of such

a current purpose, should be insufficient since there would be

no causation between the prior illicit purpose and the current

maintenance of the system.

11/ In United Airlines v. Evans, 431 U.S. 553 (1977), the

Supreme Court, although acknowledging that the effect of

an action taken some time ago may very well exist today,

the question posed for the statute of limitations was not

whether there was a present effect, but whether there was

a present violation.

- 10 -

At page 18 of their brief Plaintiffs state that Supreme

Court precedent "does not require or even encourage the trial

court to focus on any single legislative event; rather, invi-

dious intend should be found or not found only after careful

consideration of the whole series of events, historical and

contemporary, that underlie the present electoral scheme."

While Defendants are unsure of the meaning intended for this

language, they disagree with the idea that the Court could or

should attempt to answer the abstract question of whether in

general the current system of government is "maintained" or

"retained" for an invidiously discriminatory purpose as though

the system of government were a living organism with motivation

of its own. The Alabama legislature does not have a motivation,

only its individual members do.

Therefore, one cannot simply ask whether a form of govern-

ment is being maintained for an illicit purpose. The question

must focus on one or more individual acts of the legislators

alleged to have been motivated by unlawful purpose.

Other difficult issues are presented concerning the

proper scope of evidence relevant to the purpose issue. The

Supreme Court has already indicated that evidence of the

responsiveness of city officials to the particularized needs

of blacks is of "questionable relevance" to the motivation of

state legislators. Do Plaintiffs contend that the whole area

of responsiveness of city officials, or at least responsive-

ness since the original trial, should be gone into again?

Are racial campaign tactics in local Mobile elections proba-

tive of the motivation for actions of state legislators? What

about elections elsewhere in Alabama? Does it matter whether

the candidates resorting to racial campaign tactics are the

winners or the losers? Of what relevance are the actions of

the legislature in years gone by as proof of motivation for

current legislative action or inaction?

- 13 -

Further, there is the question of whose motive is con-

trolling on this question. Is it that of a majority of the

141 legislators in the Alabama House and Senate, and at

what time? Or is it the motives of those actually voting

on a particular governmental change bill? What happens if

the bill was blocked in committee? What if a bill was passed

(as has happened twice) and the people of Mobile turned it A

down in a city-wide election?

No doubt there are many other questions which would arise

and require resolution if the Court were to grant Plaintiffs’

request for further proceedings. This case has gone far enough.

The Court need not, and should not, embark on an exploration of

uncharted seas in order to give Plaintiffs a second bite at

the apple.

Conclusion

A majority of the Supreme Court both articulated the

correct legal standards applicable to this case and held

that the evidence presented by Plaintiffs did not satisfy

any of those standards. No error disfavoring Plaintiffs

having been committed by any court, and Plaintiffs having

had a full, fair opportunity to present at the trial what-

ever arguments and evidence they had, no additional "second-

chance" proceedings are warranted. Judgment for the Defen-

dants should be entered.

C bs 5 /5 / kez do gwd

Ce. B. ARENDALL, JR.

Witla, dit

WILLIAM C. TIDWELL,

P. O. Box 123

Mobile, Alabama 36601

OF COUNSEL:

HAND, ARENDALL, BEDSOLE,

GREAVES & JOHNSTON

BARRY HESS

City Attorney, City Hall

Mobile, Alabama 36602

LEGAL DEPARTMENT OF THE

CITY OF MOBILE

CERTIFICATE OF SERVICE

I certify that I have on this 24th day of October, 1980,

served a copy of the foregoing brief on counsel for all parties

to this proceeding by United States mail, properly addressed,

first class postage prepaid, to:

J. U. Blacksher, Esquire

Messrs. Blacksher, Menefee & Stein

P. 0. Box 1051

Mobile, Alabama 36601

Edward Still, Esquire

Messrs. Reeves and Still

Suite 400, Commerce Center

2027 lst Avenue, North

Birmingham, Alabama 35203

Jack Greenberg, Esquire

Eric Schnapper, Esquire

Suite 2030

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

Honorable Wade H. McCree, Jr.

Solicitor General of the

United States

Department of Justice

Washington, D. C. 20530

Drews S. Days, III, Esquire

Assistant Attorney General

Department of Justice

Washington, D. C. 20530

BA / ”

or 74 ( lr ins a

C. B. ARENDALL, JR./ io