Rule v. International Association of Bridge, Structural, and Ornamental Ironworkers Plaintiffs Appellants Petition for Rehearing and Clarification

Public Court Documents

December 5, 1977

12 pages

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Rule v. International Association of Bridge, Structural, and Ornamental Ironworkers Plaintiffs Appellants Petition for Rehearing and Clarification, 1977. 8a034361-c39a-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/3476cea3-b2c6-4bf4-8481-469305ccbf61/rule-v-international-association-of-bridge-structural-and-ornamental-ironworkers-plaintiffs-appellants-petition-for-rehearing-and-clarification. Accessed February 22, 2026.

Copied!

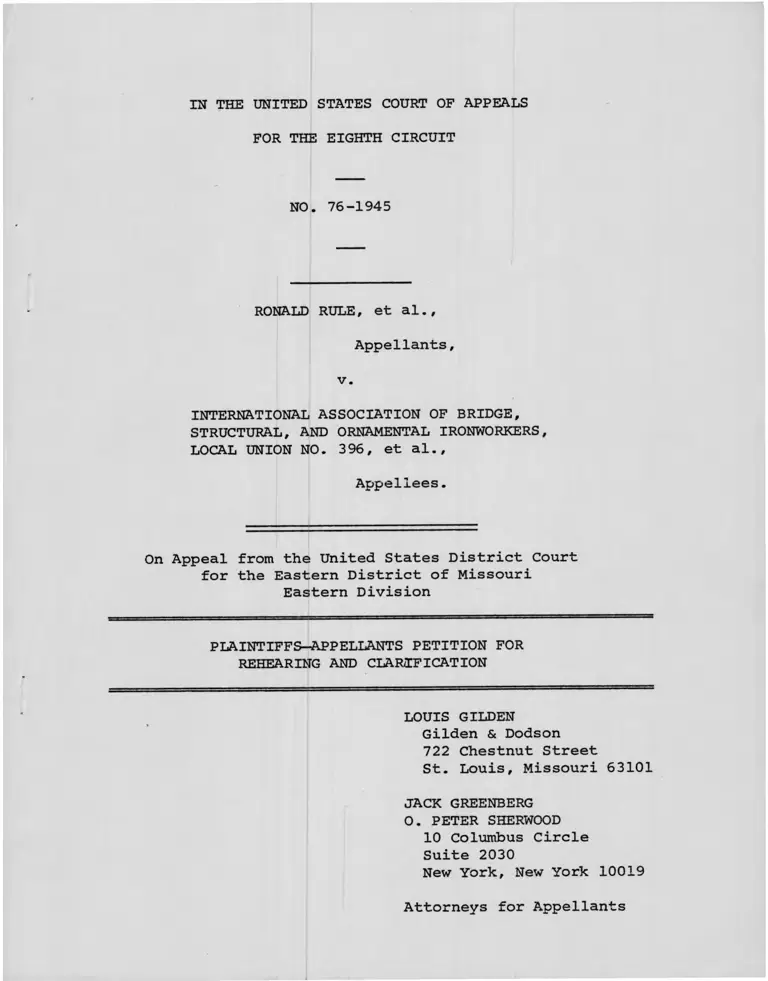

IN THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE EIGHTH CIRCUIT

NO. 76-1945

RONALD RULE, et al.,

Appellants,

v.

INTERNATIONAL ASSOCIATION OF BRIDGE,

STRUCTURAL, AND ORNAMENTAL IRONWORKERS,

LOCAL UNION NO. 396, et al.,

Appellees.

On Appeal from the United States District Court

for the Eastern District of Missouri

Eastern Division

PLAINTIFFS-APPELLANTS PETITION FOR

REHEARING AND CLARIFICATION

LOUIS GILDEN

Gilden & Dodson

722 Chestnut Street

St. Louis, Missouri 63101

JACK GREENBERG

O. PETER SHERWOOD

10 Columbus Circle

Suite 2030

New York, New York 10019

Attorneys for Appellants

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Pages

Table of Authorities ............................... ii

Preliminary Statement .................................. 2

ARGUMENT ............................................ 3

I. If Any Of The JAC Eligibility

Requirements Are Shown To Have

A Disparate Impact, It Is

Unlawful Unless Shown To Be Job

Related ................................... 3

II. The Court Need Not Reach Issues

Concerning The Disparate Effect

Of The Final Selection Process

Viewed As A Whole ............................ 5

CONCLUSION............................ 6

Certificate of Service ............................. 9

i

Pages

Franks v. Bowman Transportation Company, 424 U.S.

747, n. 32 (1976) ............................... 6, 7

Green v. Missouri Pacific R. Rompany, 523 F.2d

1290 (8th Cir. 1975) ............................ 2, 4, 5

Griggs v. Duke Power Company, 401 U.S. 424

(1971) ........................................... 4, 5

Johnson v. Goodyear Tire and Rubber Company, 491

F .2d 1364, (5th Cir. 1974) ...................... 5, 7

League of United Latin American Citizens v. City

of Santa Ana, 410 F. Supp. 873 (D.C. Cal.

1976) ............................................ 6, 7

Rogers v. International Paper Co., 510 F.2d 1340

(8th Cir. 1975) ................................. 2, 5

Smith v. City of East Cleveland, 363 F. Supp.

1131, n. 10 (N.D. Ohio, 1973) .................... 4

Smith v. Troyan, 520 F.2d 492 (6th Cir. 1975) .... 4

Washington v. Davis, 426 U.S. 229 (1976) ......... 4

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

IN THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE EIGHTH CIRCUIT

NO. 76-1945

RONALD RULE, et al.,

Appellants,

v.

INTERNATIONAL ASSOCIATION OF BRIDGE,

STRUCTURAL, AND ORNAMENTAL IRONWORKERS,

LOCAL UNION NO. 396, et al.,

Appellees.

On Appeal from the United States District Court

for the Eastern District of Missouri

Eastern Division

PLAINTIFFS-APPELLANTS PETITION FOR

REHEARING AND CLARIFICATION

PRELIMINARY STATEMENT

Plaiirtiffs-appellants, Ronald Rule, et al., hereby

petition the Court for rehearing and clarification of a limited

portion of its decision in this cause entered November 22, 1977.

This petition is addressed to that portion of the Court's deci

sion at footnote 10 which holds that a determination of the

disparate exclusionary impact of the apprentice selection process

must be measured by an examination of the selection process as a

whole rather than an examination of the various elements of that

process. See Slip Opinion p. 14, n. 10. In those few sentences

the Court decides a series of important issues of substantive

Title VII law, creates a conflict among the Circuits, e.g., see

Johnson v. Goodyear Tire and Rubber Co., 491 F.2d 1364, 1372-73

(5th Cir. 1974), and creates a conflict within the Eighth Circuit,

see Green v. Missouri Pacific R. Co., 523 F.2d 1290 (8th Cir.

1975); Rogers v. International Paper Co., 510 F.2d 1340, 1348-49

(8th Cir. 1975) even though resolution of this issue is not

essential to a determination of this case since the record here

reveals the requisite disparate impact of both the important

elements of the selection process and of the selection process

1/

overall. See Slip Opinion, p. 14, Br. 13, 20-27 and A. 96-98.

1/ Throughout this brief reference to plaintiffs main brief is

cited as "Br.". References to plaintiffs reply brief is cited

as "Reply Br.". References to Defendant, Ironworkers et al.,

brief is cited as "R. Br.". References to the joint Appendix

of the parties is cited as "A.".

2

For the reasons set forth below plaintiffs urge that the

first paragraph of footnote 10 be eliminated or that it be

altered substantially to bring that portion of the Court's

decision into conformity with prevailing Title VII law.

ARGUMENT

The Ironworker apprenticeship selection process is complex

and the substantive Title VII principles with which that process

interfaces is more complex. The apprenticeship selection process

can be grouped into two phases (1) initial screening, and (2)

ranking and selection. In this case plaintiffs have challenged

both aspects of the apprenticeship selection process. Footnote

10 of the Court's opinion appears to encompass both aspects of

the selection process. Accordingly it is essential that both

aspects of the selection process be examined.

I.

If Any Of The JAC Eligibility Requirements

Are Shown To Have A Disparate Impact. It Is

Unlawful Unless Shown To Be Job Related

Any applicant for the apprenticeship program who does not

possess a high school diploma (or its equivalent) (Br. 20) is

deemed ineligible for further consideration (Br. 23, A. 77). An

applicant, like plaintiff Ronald Rule, who fails to meet this

requirement is absolutely barred from any consideration even

though he may be able to perform adequately on the job.

3

Prior to the Court's decision in this case, no appellate

court has permitted an eligibility requirement to stand without

proof of job relatedness once plaintiffs have shown that the

particular eligibility requirement has an adverse impact. See

Johnson v. Goodyear Tire and Rubber Co.. 491 F.2d 1364, 1372-73

(5th Cir. 1975); Griggs v. Duke Power Co., 401 U.S. 424 (1971);

Rogers v. International Paper Co., 510 F.2d 1340 (8th Cir. 1975).

This is so even where the employer or labor organization has

presented evidence tending to show that there was no adverse

racial disparity when its employment selection practices are

viewed as a whole. See Johnson v. Goodyear Tire and Rubber Co..

supra, 491 F.2d at 1372-73 and Green v. Missouri Pacific R. Co..

523 F.2d 1290 (8th Cir. 1975). Smith v. Troyan, 520 F.2d 492

(6th Cir. 1975) is not to the contrary since the court there

2/

was not examining eligibility requirements. See Smith v. City

of East Cleveland, 363 F. Supp. 1131, 1145, n. 10 (N.D. Ohio,

1973).

In this case plaintiffs proved that the high school

diploma requirement has a disparate impact on black applicants

for the apprenticeship program. (Slip Opinion at p. 15, A. 97).

2/ It is also important to note that Smith, supra, involved a

constitutional challenge to the City of East Cleveland, police

selection process as opposed to the Title VII challenge involv

ed here. Different standards apply in a constitutional case

than in one brought under Title VII. See Washington v. Davis,

426 U.S. 229 (1976).

4

Upon this proof plaintiffs are entitled to prevail as to these

eligibility requirements absent a showing of job relatedness

by the defendants. See Griggs v. Duke Power Co., supra.

The rule which this Court announced at footnote 10 is

contrary to Griggs, supra, and is squarely in conflict with

this Circuit's decision in Green, supra, and the Fifth

Circuit's decision in Johnson, supra. It also appears to be

contrary to Rogers v. International Paper Co., 510 F.2d 1340,

1348-49 (8th Cir. 1975). Further the first paragraph of foot

note 10 is not essential to the court's decision because

plaintiffs have shown the JAC selection process as a whole to

have an adverse disparate impact. See Slip Opinion at p. 14.

Accordingly this portion of the Court's opinion should be

eliminated.

II.

The Court Need Not Reach Issues

Concerning The Disparate Effect

Of The Final Selection Process

Viewed As A Whole

It may be argued that the procedure for ranking and

selecting persons for actual admission to the apprenticeship

program may be viewed as a whole for the purpose of determin

ing adverse impact but that issue need not and should not be

resolved here because an important element of that procedure,

the high school diploma requirements, have already been

found unlawful. The fact that some

5

blacks who were able to overcome the first unlawfully

discriminatory device and were not discriminated against

in the final stages of the selection process should not

deprive those who were victims of discrimination from

4/

obtaining relief. See League of United Latin American

Citizens v. City of Santa Ana, 410 F. Supp. 873, 893-94

(D.C. Cal. 1976). Further the evidence in the present

record shows that the JAC selection process viewed as a

whole does have a disparate impact which is sufficient to

shift the burden to the defendants to prove job relatedness

See Slip Opinion at p. 14, A. 96-98. Of course the

defendants will be afforded an opportunity to prove at a

subsequent stage of the case that individual class members

are not entitled to relief under the standards set forth

in Franks v. Bowman Transportation Co., 424 U.S. 747, 773,

n. 32 (1976).

CONCLUSION

Footnote 10 creates a new rule of law in Title VII

3/ This comment can be made as to the Flanigan test as well

since any applicant such as plaintiffs Vanderson and Coe who

obtain no points for the test is effectively precluded from

being selected.

6

cases that is in conflict with other appellate decisions.

That footnote should be eliminated from the Court's

opinion. In the event that the Court concludes that it

will comment on the appropriate role of evidence of the

adverse impact of the apprenticeship selection process as

a whole, plaintiffs urge that language along the following

lines be substituted:

Plaintiffs Vanderson and Coe center their

challenge on the disparate impact of the

Flanigan test which accounts for 15 of

100 possible points. While it may be

argued that the JAC selection process must

be viewed as a whole to discover whether

there is a disparate impact, it must be

remembered that Title VII was designed to

protect individuals. See League of

United Latin American Citizens v. City of

Santa Ana., 410 F. Supp. 873, 893-94

(C.D. Cal. 1976). That other minority

persons were over selected on other non-

discriminatory factors is of no

assistance to those minority persons who

were the victims of a discriminatory test.

Similarly, any class member who was deemed

ineligible for consideration in the

apprenticeship program because they did not

possess a high school diploma are entitled

to be considered for relief regardless of

any absence of a disparate impact of the

selection process overall. See Johnson v .

Goodyear Tire and Rubber Co., 491 F.2d

1364, 1372-73 (5th Cir. 1974). Of course

the defendants remain free to prove at a

subsequent stage of the case that the

individuals who were adversely affected by

the test would not have been selected for

admission absent any discrimination. See

Franks v. Bowman Transportation, 424 U.S.

747, 773 (1976).

7

Coe and Vanderson also challenge the

use of the Flannigan test because it

has not been validated as required by

the consent decree in the Government1s

case. The consent decree grants the

United States a right of enforcement.

We perceive no error in the District

Court's holding that plaintiffs lack

standing to sue to enforce the consent

decree.

Respectfully submitted,

LOUIS GILDEN

722 Chestnut Street

St. Louis, Missouri 63101

JACK GREENBERG

0. PETER SHERWOOD

10 Columbus Circle

Suite 2030

New York, New York 10019

8

CERTIFICATE OF SERVICE

This is to certify that on the 5th day of December,

1977, I served a copy of the foregoing PLAINTIFFS-

APPELLANTS PETITION FOR REHEARING AND CLARIFICATION upon

the following counsel of record by depositing same in the

United States mail, postage prepaid.

BARRY J. LEVINE, ESQ.

Gruenberg, Souders & Levine

905 Chemical Building

721 Olive Street

St. Louis, Missouri 63101

/

ATTORNEY FOR APPELLANTS

9 -