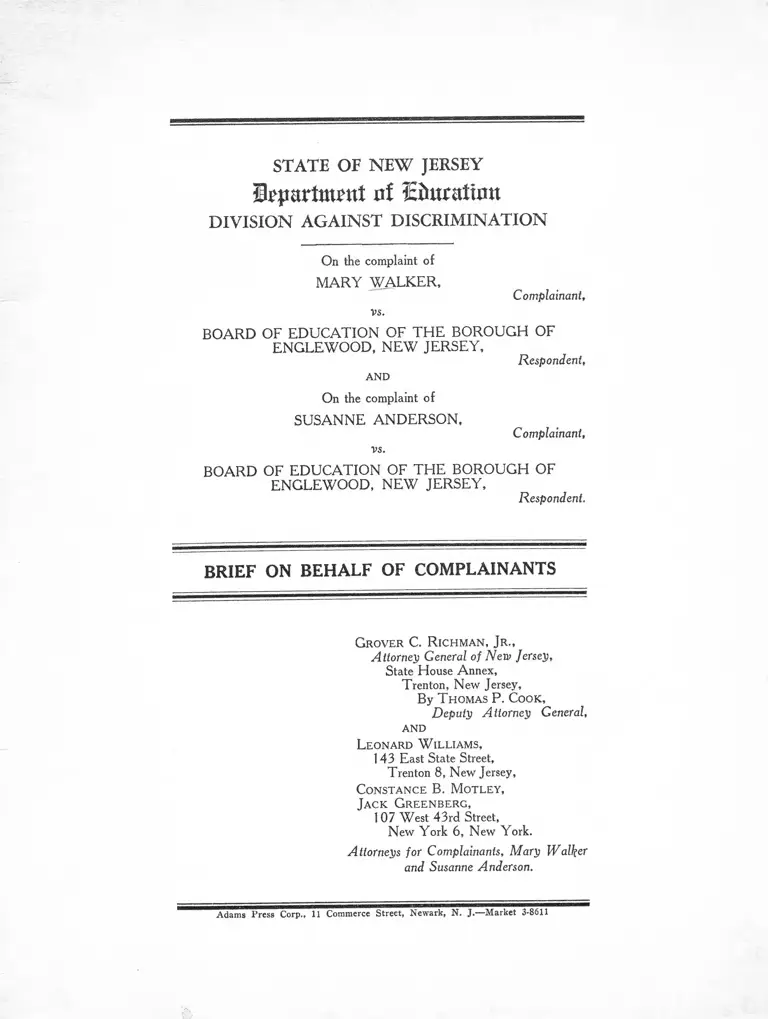

Walker v. Englewood New Jersey Board of Education Brief on Behalf of Complaintants

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1954

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Walker v. Englewood New Jersey Board of Education Brief on Behalf of Complaintants, 1954. bf998041-c89a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/3483a4f4-a76f-47d8-9c03-a3e5372ebaec/walker-v-englewood-new-jersey-board-of-education-brief-on-behalf-of-complaintants. Accessed February 22, 2026.

Copied!

STATE OF NEW JERSEY

Hpjmrfumtt nf

DIVISION AGAINST DISCRIMINATION

On the complaint of

M A R Y W A L K E R ,

vs.

Complainant,

B O A R D OF ED U CATIO N OF T H E BO RO U G H OF

EN G LEW O O D , N E W JERSEY,

Respondent,

AND

On the complaint of

SUSANNE A N D ERSO N ,

vs.

Complainant,

B O A R D OF E D U CATIO N OF TH E BO RO U G H OF

EN G LEW O O D , N E W JERSEY,

Respondent.

BRIEF ON BEHALF OF COMPLAINANTS

G rover C. R ichman, Jr .,

Attorney General of New Jersey,

State House Annex,

Trenton, New Jersey,

By T homas P. Cook,

Deputy Attorney General,

AND

L eonard W illiams,

143 East State Street,

Trenton 8, New Jersey,

Constance B. M otley,

Jack G reenberg,

1 07 West 43rd Street,

New York 6, New York.

Attorneys for Complainants, Mary Walker

and Susanne Anderson.

Adams Press Corp., 11 Commerce Street, Newark, N. J.— Market 3-8611

TABLE OF CONTENTS

PAGE

S tatem en t ...................................................................................... 1

T h e E vidence ............................................................................. 3

A. The Englewood Schools and Their Racial Con

stituencies .......................................................... 3

B. The Board’s Act of June 28,1954 Establishing

New Attendance Z on es.................................... 6

C. The Expert Testimony as to School Boundary

L in es................................................................... 8

D. The Evil Effects of Segregation........................ 12

E. Specific Incidences of Discrimination in En

glewood .............................................................. 14

F. The Defense.......................................................... 20

S u m m a r y op A rg u m en t .......................................................... 23

P oint I— The Respondent unlawfully discriminated

against all Negro children who were being obliged

to attend Lincoln Elementary School during the

school year 1953-1954 .................................................. 25

A. The Responsibilities of a Board of Education .. 25

B. Permitting Unnecessary Segregation is Discrim

ination ....................................................................... 29

C. Segregation at Lincoln Can Be Eliminated . . . . 33

P o in t II—The Respondent unlawfully discriminated

against the Complainant Walker’s child and others

similarly situated when it established a new attend

ance zone line between the Lincoln and Liberty Dis

trict so as to enlarge and extend Lincoln Elemen

tary as an almost exclusively Negro school........... 35

P o in t III—The Respondent unlawfully discriminated

against members of the Negro race by maintaining

a separate and virtually all Negro junior high

11 TABLE OF CONTENTS

PAGE

school for children residing in Lincoln District,

while sending pupils from all other elementary dis

tricts to Engle Street Junior High School, the stu

dent body of which has been predominantly white. . 38

C onclusion as to P oints I, II and III— T h e P ower

and D u ty op th e Co m m is s io n e r ................................... 40

P oint IV— The Respondent unlawfully discriminated

against the Complainant Anderson’s child and other

Negroes similarly situated by sending them to Lin

coln Elementary School, while white children from

the same zone were sent to Liberty School............ 42

C o n c l u s io n ...................................................................................... 46

Exhibit S -5 ...................................................................... 48

Cases Cited

Blackman v. lies, 4 N. J. 82 (1950) ............................ 29

Bolling v. Sharpe, 347 U. S. 497 (1954) ..................... 27

Brown v. Board of Education, 347 U. S. 483 (1954). . .27, 29

Como Farms v. Foran, 6 N. J. Super. 306, 71 A. 2d 201

(App. Div., 1950) ....................................................... 41

Doremus v. Board of Education of Hawthorne, 5 N. J.

435 (1950) .................................................................... 29

Federal Trade Commission v. Goodyear T. & R. Co.,

304 U. S. 257 (1938) ................................................... 45

Fornarotto v. Board of Public Utility Commissioners,

105 N. J. L. 28, 143 A. 458 (Sup. Ct., 1928) ........... 41

Gaine v. Burnett, 122 N. J. L. 39, 4 A. 2d 37 (Sup. Ct.,

1939), aff’d 123 N. J. L. 317, 8 A. 2d 604 (E. & A.,

1939) ............................................................................ 41

J. I. Case Co. v. N. L. R. B., 321 U. S. 322 (1944) . . . . 45

Mendez v. "Westminister School District, 64 F. Supp.

544 (D. C. Cal., 1946) ............................................. .40,44

PAGE

Perma-Maid Go. v. F. T. C., 121 Fed. 2d 282 (C. C. A.

6, 1941) ....................................................................... 45,46

United States v. Fawcett, 115 Fed. 2d 764 ( 0. 0. A.

3d, 1940) ..................................................................... 43

New Jersey Constitution Cited

Article 1, par. 5 ...................................................... 27

Statutes Cited

N.J.S.A. 18:25-1 et seq.................................................. 1

N.J.S.A. 18:25-5(j) ........................................................ 27

N.J.S.A. 18:25-6 ............................................................ 40

N.J.S.A. 18:25-ll(f) ..................................................... 40

N.J.S.A. 18:25-12 .......................................................... 23

N.J.S.A. 18:25-12(f) ..................................................... 26

N.J.S.A. 18:25-15 .......................................................... 2

N.J.S.A. 18:25-16 .......................................................... 2

N.J.S.A. 18:25-17 .......................................................... 46

P.L. 1945, Ch. 169 ..................................................... 26

E.S. 18:11-1 ...................................................................25,31

R.S. 18:14-2 .................................................................. 27

R.S. 18:14-5 to 18:14-9 ................................................... 26

Rule Cited

R.E. 4:15-2 ................................................................1 fn, 3 fn

Texts Cited

Ashmore, The Negro and the Schools (1954), pp.76-77 30

McQuillin, Municipal Corporations (3rd Ed.), Sec

tions 53.65, 53.27, 53.69 ............................................... 44

Wigmore, Code of Evidence (3d Ed. 1942) Rule 69,

pp. 104-106 ..................................................................

TA B L E OF CONTENTS 111

43

Statement

This brief is submitted on behalf of the Complainants

in each of the above entitled proceedings.

The case of Susanne Anderson against the Board of Ed

ucation of the Borough of Englewood, New Jersey, arose

upon an amended complaint signed by Mrs. Anderson

charging the Respondent with an unlawful practice within

the meaning of subsection “ f ” of Section 11 of the Law

Against Discrimination (N.J.S.A. 18:25-1 et seq.) in that

her son, James, entered Liberty School in Englewood in

September 1950,* but because she is a member of the Negro

race, the boy was transferred about a month later to the

Lincoln School, although her residence was within the

district from which white children were sent to the Liberty

School. She charged that this action by the Respondent

was part of a consistent scheme and plan to discriminate

against Negroes by excluding them from the integrated

Liberty School and obliging them to attend the segregated

Lincoln School.

The case of Mary Walker against the same Respondent

arose on her complaint charging a violation of the same

section of the law in that her son, Theodore Walker, was

obliged to attend the Lincoln School kindergarten at the

opening of school in September 1954 because of a new boun

dary line between Lincoln and Liberty Schools for attend

ance at kindergarten. This was alleged to result in an

extension of segregation in the Lincoln School, also pur

suant to a consistent scheme and plan to discriminate

against members of the Negro race.

The answer filed by the Respondent in each case denied

the charges of discrimination. The answer in the Anderson

* By consent of counsel for the Respondent, the complaint is

deemed amended by changing the year 1950 to 1949, in order to con

form with the evidence received at the hearing. Cf. R.R. 4:15-2.

2

ease further alleged that the incident related in that com

plaint resulted from a mistake or inadvertence on the part

of someone in the school system, and that the mistake was

corrected as soon as it came to the attention of the Board

of Education. In the Walker case, the answer denied that

the boundary lines resulted in a segregation of the Lincoln

School area or that discrimination against any race was

thereby accomplished or intended. The Respondent further

alleged that it had fixed the boundary lines in the exercise

of its sound discretion to relieve congestion in certain

schools and to utilize classrooms in some schools which had

previously been unoccupied.

Pursuant to notice of hearing duly given in accordance

with the statute (N.J.S.A. 18:25-15), a public hearing was

held before the Commissioner of Education on October 20,

October 26, and November 1, 1954. The stenographic tran

script of the testimony ran to 412 pages, and 20 exhibits

were received, 17 offered by the Complainants, and 3 by the

Respondent. The case for the Complainants was presented

by the Attorney General, through Deputy Attorney Gen

eral Thomas P. Cook. The Complainants and certain other

witnesses were examined by Mrs. Constance B. Motley, of

the New York Bar, who had been granted leave to inter

vene in these cases, pursuant to N.J.S.A. 18:25-16. The

Complainants were also represented by Leonard Williams,

Esq., of the New Jersey Bar, and Jack Greenberg, Esq., of

the New York Bar, who had similarly been granted leave

to intervene. The case for the Respondent was presented

by Hon. Thomas J. Brogan, assisted by Henry P. Wolff,

Jr., Esq. and Leroy B. Huckin, Esq., the latter being at

torney of record.

The Commissioner of Education presided at the hear

ing, since the Assistant Commissioner John P. Milligan,

as head of the Division Against Discrimination, had par

ticipated in the investigation of the complaints and in

efforts at conciliation.

3

By a stipulation entered into between counsel for the

parties prior to the hearing, it was agreed that the two

complaints should be consolidated for the purposes of the

hearing. It was further stipulated that the issues to be de

termined at the hearing were as follows:

(a) Did the Respondent engage in an unlawful dis

crimination as alleged in the complaint of Susanne

Anderson?

(b) Did the Respondent engage in an unlawful dis

crimination as alleged in the complaint of Mary

Walker?

(c) Did the Respondent unlawfully discriminate

against any persons of the Negro race by the estab

lishment of school zone or attendance district lines as

they existed during the school year 1953-1954?

(d) Did the Respondent unlawfully discriminate

against any persons of the Negro race by the estab

lishment of new attendance district lines as of Sep

tember 1, 1954, for kindergarten in the Lincoln and

Liberty Schools and for kindergarten and first grade

in other schools?

(e) Has the Respondent, between September 1949*

and the present time, followed a consistent plan,

scheme or policy of discrimination against Negroes in

the admission of pupils to its schools?

The Evidence

A. The Englewood Schools and Their Racial Constituencies.

The Borough of Englewood, which had a population of

23,145 as of the 1950 census and embraces an area roughly

two miles square, has since 1939 been operating five ele

* The date originally stipulated (Exhibit S-l.) was September

1950, but by consent of counsel for the Respondent, the year was

changed to 1949 in order to conform the pre-hearing stipulation to

the evidence regarding the Anderson Complaint. Cf. R.R. 4:15-2.

4

mentary schools, two junior high schools and one senior

high school (S-2, S-6, R-l, pp. 6, 24).* ** Each elementary

school takes pupils from kindergarten through the sixth

grade; each junior high school comprises grades seven

through nine, and the senior high school takes the tenth

through twelfth grades.

The controversy in this case centers around the so-called

Lincoln schools, which consist of an elementary and a

junior high school, all located in the same building (R-l,

pp. 20, 21, 24). In the school year 1953-1954 there was only

one white child in the Lincoln Elementary School out of a

total enrollment of 331. All the other pupils in the ele

mentary, and all 142 students in Lincoln Junior High, were

Negro (38,*# S-ll, S-10, S-8). In fact, for the past 15 years

Lincoln’s population has been mostly Negro (394).

The Lincoln school building is located on the north side

of Englewood Avenue between William and Humphrey

Streets (S-2, S-5). It stands one block south and two blocks

west of the central point of the Borough, where Palisade

Avenue, the main east-west thoroughfare, is bisected by

the tracks of a branch of the Erie Railroad. Two blocks

east and one-half block north of that point lie the Frank

lin Elementary School and the Engle Street Junior High

School. Two blocks west and one block north from the

Lincoln school, on the north side of Palisade Avenue, is the

Liberty Elementary School. The Senior High School and

the Cleveland Elementary School are situated in the north

west part of the city, Avhile the Roosevelt Elementary

School serves the southeast section (S-2, S-3).

* Exhibits introduced by the Complainants have numbers beginning

with S and exhibits introduced by Respondent have numbers begin

ning with R.

For the convenience o f the reader, a copy of Exhibit S-5, a map

o f Englewood showing Negro residential areas, is attached to this

Brief.

** Numbers refer to pages o f the transcript o f testimony, unless

otherwise indicated.

5

Lincoln is located in the Fourth Ward of the city, which

consists of substantially the southwest quarter. The

Fourth Ward is bounded on the north by Palisade Avenue

and on the east by the Erie Railroad tracks (S-2). At the

time of the hearing, there were no Negroes living in the

houses on the south side of Palisade Avenue, but begin

ning in the rear of those houses the residents are mostly

colored (62-64; S-5). According to estimates by Mr. Glatt,

investigator for the Division against Discrimination, which

were not disputed at the hearing, the greater part of the

Fourth Ward is 100% Negro but for a few scattered wThite

families. Along Englewood Avenue and the Fourth Ward

Park, however, the distribution is approximately 60%

Negro and 40% white, while in the northwest part of the

Fourth Ward up to a line along the rear of the houses on

the south side of Palisade Avenue, the colored population

was estimated at 75% to 80% and the white at 20% to

25% (S-5). Mr. Glatt estimated the population of Negroes

in the Fourth Ward as “ roughly from 85% to 90%” (64).

Mr. Fitzpatrick, President of the Board of Education, con

firmed that estimate by testifying that the Fourth Ward

was “ now populated generally by members of the Negro

race and their families” (392).

The zones for attendance as between Lincoln and the

neighboring elementary schools in the district had until

1954 evidently been unchanged for many years. Lincoln

had been zoned to take care of all children from kinder

garten through sixth grade residing in roughly the south

east half of the Fourth Ward. The northerly boundary of

the zone ran westerly from the railroad tracks along the

rear of the buildings on the south side of Palisade Avenue,

then south along Armory Street to Englewood Avenue,

southwest across the park to Lafayette Place at Franklin

Road, and south on Lafayette Place to the boundary of the

municipality (S-2, S-4). Children in the Fourth Ward

north and west of the line just described were supposed to

attend Liberty School.

6

Until 1938, all junior high school children, including

those graduating from Lincoln Elementary, attended the

Engle Street Junior High School. In 1938 and 1939, how

ever, Lincoln Junior High School was opened to take care

of grades seven through nine for children residing in the

Lincoln Elementary district (362; R-l, p. 24). After Lin

coln Junior High was established, children from all the

other elementary districts in the municipality continued to

attend the Engle Street Junior High (R-l, p. 24).

The racial constituency of the various schools for the

year 1953-1954, according to estimates furnished by Dr.

Harry L. Stearns, Superintendent of Schools in Englewood

(S-10), was as follows:

No. of Grade Present % Teachers

School Classrooms Level Enrollment Negro Negro White

Dwight Morrow High . . . 32 10-12 888 13% 1 44

Engle St. Jr. High......... 23 7-9 558 10% 28

Cleveland School ........... 19 K-6 701 0 24

Franklin S ch ool.............. 14 K-6 306 4% 13

Liberty School ................ 16 K-6 429 43% 14

Lincoln School ............... 26 K-9 494 99% 8 13

Roosevelt School ............. 13 K-6 437 8% 15

B. The Board’s Act of June 28, 1954 Establishing New

Attendance Zones.

With the previously described situation facing them, the

Board of Education in the winter of 1954 tackled the prob

lem of overcrowding at Cleveland School and the need for

new facilities in the district generally. Simultaneously,

while the Board was considering these matters, the issue of

segregation in the Lincoln schools was receiving much at

tention in Englewood. All through the winter it was the

subject of numerous articles in the local press (S-16). A

number of citizens brought it up at one or more Board

meetings (381). It was also specifically raised in one of the

minority reports of the Citizens Review Committee (R-3),

a group of citizens appointed by the Board of Education to

7

study the situation, and report to the Board (302-308).

The three authors of that minority report, dated March 29,

1954, said:

“ The peculiar residential pattern existing in Engle

wood has unwittingly thrown upon the Board of Edu

cation a segregated area to administer. Although we

realize that building a school on Lafayette Place would

not eliminate the problem of segregation, it is better to

face up rather than delay a decision. * * * It is not an

impossible task to eliminate segregation if a commu

nity and its leaders have matured to the point where

it can recognize the unhealthy aspect of the problem,

and do something constructive about it.”

Nevertheless, purportedly in order to relieve overcrowd

ing in the Cleveland School (300), the Board on June 28,

1954 resolved to redraw the line between Liberty and Lin

coln zones in regard to kindergarten attendance only (leav

ing the other grades as between those schools unaffected

temporarily), thereby zoning back into Lincoln kindergarten

a large number of Negro families, including that of the

Complainant Walker, who lived in the northwest sector of

the Fourth Ward. The new line was a westerly extension

of the old north boundary of the Lincoln zone, which ran

along the rear line of lots on the south side of Palisade

Avenue; the change extended this line westerly all the way

to the west end of town (313; S-3). A concurrent reloca

tion of the north line of the Liberty district zoned into the

latter a number of kindergarten and first grade children

who under the old line would have gone to Cleveland

School, and thus Cleveland was relieved to that extent

from its crowded condition (310-314; S-3).

The changes, however, only aggravated the racial prob

lem. In the school year 1953 to 1954 Liberty School had

had three kindergarten sections of about 30 pupils each,

of whom approximately one-third were Negroes. After the

new zoning, Liberty had only two kindergarten sections, of

8

about 27 each, with not a single Negro among them (325-6;

S -ll). On the other hand, with the kindergarten popula

tion of Lincoln increased from 52 to 102 (S-8, S-9), only

two of those children were white (S -ll).

C. The Expert Testimony as to School Boundary Lines.

Two expert witnesses called by the Complainants testi

fied that the new boundary between Liberty and Lincoln

kindergartens was not the best solution to the problem of

overcrowding at Cleveland, and that it would be possible to

solve the problem in other ways which would at the same

time reduce the present predominance of Negro students in

the Lincoln schools.

The first such witness was Dr. John P. Milligan, the

Assistant Commissioner of Education in charge of the Di

vision Against Discrimination since December 1953. As for

his qualifications, he had been a school principal in the

New Jersey school system for 7 years, Professor of Edu

cation in State Teachers’ Colleges in New Jersey for 9

years, including 6 years at the Jersey City State Teachers’

College, of which he was Dean; Superintendent of Schools

at Glen Ridge and at Atlantic City for a total of 7% years;

and consultant in school integration problems in St. Louis,

Washington, D. C., and Wilmington, Delaware (66). He

testified that when a board of education provides school

facilities for pupils in a given community, the factors to

be considered by the board, aside from any question of

racial segregation, include convenience of access to the

schools by the pupils, traffic arteries, vacancy of class

rooms and other facilities, the size of the classes, and the

economic and efficient use of the facilities of the school

system (67). Apart from any question of segregation, it

was his opinion that the zones of attendance in effect as of

June 1954, as shown on Exhibit S-2, present “ grave ques

tions” as to their reasonableness (68). It would be un

reasonable, he said, even if the community were all white,

to have two junior high schools, with 133 students attend

9

ing the Lincoln Junior High School, and 558 attending the

Engle Street Junior High, because (70) “ it is generally

agreed among administrators who understand these prob

lems that facilities up to a thousand pupils at least are the

best and most efficient use of such facilities in one junior

high school, elementary school or high school.” Dr. Milli

gan further stated that it was more economical and more

desirable administratively to have a single junior high

school for Englewood, and that the smaller junior high at

Lincoln could provide the same courses of study as Engle

Street only at a much greater cost than if the two schools

were combined.

In Dr. Milligan’s opinion, it was also unreasonable to

have the northerly boundary line of the Lincoln district

drawn in the rear of the houses on the north side of Pali

sade Avenue, as shown on Exhibit S-2, when, as of October

1, 1953, the average classes at the Lincoln elementary ran

24 pupils per teacher, while Liberty had 30 pupils per

teacher (S-8), and yet the pupils living on the south side

of Palisade Avenue were compelled to cross that heavily

traveled artery to get to the more crowded Liberty school

(73-74). There was no valid reason for making the boun

dary line run along the rear line of the houses on the south

side of Palisade Avenue instead of down the center of the

avenue (79).

According to the Assistant Commissioner, it would be

advisable, as a temporary expedient (177-8, 197), to abol

ish the separate Lincoln Junior High School and to com

bine all junior high pupils in one school, either in the

Lincoln building or at Engle Street, and concurrently to

relocate the elementary pupils whose places would be taken

by the junior high school students (75, 107-108). Although

traffic arteries are “ important” factors to be considered,

they would not constitute a barrier to the unification of

the junior high schools, since police protection could be

and is now being provided for all other pupils crossing

certain heavily traveled streets to get to their assigned

school (76-77, 79).

10

The establishment of a single junior high school for the

entire district is one way, in Dr. Milligan’s opinion, in

which a greater degree of integration could well be brought

about without undue violence to the physical factors in

volved (77, 107-8). It would also be feasible to reduce seg

regation and still make a reasonable use of existing school

facilities by establishing other attendance district lines for

the elementary schools (76). Although Dr. Milligan could

not assume to dictate to the Board just how the problem

should be solved, since that is the Board’s responsibility

under the law (82, 105, 199-202), he suggested taking pu

pils from north and east of the old Lincoln district, and

additional police protection at traffic crossings, if necessary

(76). The taking of additional white pupils into Lincoln

School in this manner would also utilize some six available

classrooms in that building (79-80). The Board might also

make use of the so-called “ Princeton Plan” (105, 162-165),

which would eliminate segregation and accomplish integra

tion through combining Lincoln Elementary and Liberty

into one district and dividing up the seven elementary

grades (including kindergarten) between the two school

buildings (164-5). This action would bring about a racial

distribution in the two schools of approximately 27% white

and 73% Negro children in each building (180).

In conclusion, Dr. Milligan testified (81):

“ I believe it would be possible to achieve, with due

consideration of the physical factors, greater integra

tion of students than has been done either under the

former boundary lines or the present boundary lines

and it would be possible to eliminate a racially segre

gated school in the Lincoln School.”

Dr. H. Ii. Giles, Professor of Education and Director of

the Center for Human Relation Studies at New York Uni

versity, also testified as an expert on the subject of pos

sible methods of integrating the racial segments in the

Englewood schools. His previous experience had included

11

service as a consultant to the school systems of several

large cities, both in the North and South, on inter-group

and racial relations (118-119). After a six-year study of

the problem in Englewood, where Dr. Giles has resided

since 1915 (118, 120), he concluded that

“ the Board of Education in Englewood could, in ac

cordance with accepted educational practice and poli

cies, distribute the school population in Englewood in

such a way as to make the best possible use of present

school facilities and at the same time reduce the pres

ent predominance of Negro students in the Lincoln

schools.” (123)

He concurred in Dr. Milligan’s suggestion that one pos

sible way would be the “ Princeton Plan” , whereby “ the

present Lincoln School district and the present Liberty

School district would constitute a single school district

with a redistribution of classes, perhaps from kindergarten

to the third grade to go to the Liberty School and the

fourth to the sixth grades to go to the Lincoln School”

(124-). Another possibility, he said, would be “ to abolish

the Lincoln School and redistribute its present population

among other schools in the city” , with some provision per

haps for transportation (124). This would be, of course, a

long range plan, involving new construction (126).

Neither the old school zone lines (S-2) nor the new lines

which went into effect September 1, 1954 (S-3) made the

best possible distribution of students from the racial point

of view, according to Dr. Giles (124-125). His views have

been made known to the Superintendent and to the Board

of Education and to the executives of the Urban League,

by whom he had been asked to consider the problem (125-

126) .

On cross-examination, Dr. Giles elaborated the reasons

for his suggestion of the Princeton Plan, as follows (130):

“ Q. In other words, in these two school districts the

older children would go to the Lincoln School and the

12

younger children would go to the Liberty School1? A.

They might.

Q. What do you think that would accomplish! A. I

think it would accomplish two or three things, in my

judgment which would be feasible. The first of these,

I believe I would mention, is a reduction of the present

situation at Lincoln School in the figures, as I have

seen listed at 99 plus per cent Negro. It would not

mean a larg*e reduction but I believe it would mean a

reduction of perhaps to something like 80 per cent

but it would mean a substantial reduction over what

now obtains in that school. The second possibility I

would say in this move would be a greater use of the

shops and equipment, especially at Lincoln School,

as would be natural with the older children. ’ ’

Dr. Giles also emphasized that under his second pro

posal, he would eliminate the Lincoln School “ in order to

place these children in other parts of the city in schools

which would not draw from the heavily populated Negro

ward” (131).

At the end of his cross-examination, Dr. Giles recom

mended as an authoritative work in this field, the publica

tion, “ They Learn What They Live” , of which Mrs. Helen

Trager wTas co-author.

D. The Evil Effects of Segregation.

The Complainants then called Mrs. Trager, a mem

ber of the staff of the Teacher Education Department at

Brooklyn College in New York and an expert in the field

of education and personality development of children (205-

208). She gave convincing testimony as to the harmful

effect of racial separation on the development of Negro

children in a school which is predominantly colored. She

described in detail a scientific study of the subject which

had been conducted in Philadelphia from 1945 to 1948

(208) where the separation of the races was not brought

13

about by law but rather by the residential location of the

Negro community (216), Her conclusions appear in the

following portions of her testimony (214-215; 216):

“ Q. Now I want to ask you this question. As a re

sult of the study you made in Philadelphia and these

conclusions which you have just reported about the

race attitude of the Negro and white children in the

kindergarten, first and second grades with relation to

segregation, would you say these conclusions indicate

that racial segregation causes irreparable injury to

the personality and development of Negro children in

contrast to that of the white children? A. I would say

yes to that. The Negro children get a distorted view,

that will follow them into adult life, of a lack of com

petency; that their inability to attain good social re

lations with the white children must be due to some

inherent inadequacy or incompetency. The hurt to the

personality of the Negro child is very definite and it

exists because the Negro child cannot develop the kind

of self-regard that is necessary for a balanced person

ality. The Negro child does not feel he is accepted by

other people, and therefore, how can he feel a sense of

self-reliance and adequacy and as they grow up, they

feel they are second-class citizens, so to speak.

Q. Does that situation have an effect on the ability

of a Negro child to learn? A. You mean in the public

schools ?

Q. Yes. A. Very definitely for the reason that in

order to be able to learn, there must be energy—mental

energy, if you will, and if that energy is diverted into

feelings due to inadequacy and fear, it makes it less

likely that the child who feels this inadequacy and this

fear, will be able to cope with the problem of learning

to his fullest capacity and that would be true with any

child beset by such handicaps.” * * *

“ Q. Now, based on your study in Philadelphia,

would you say that in any northern community which is

14

similar—that is, where there are public schools which

are in fact segregated where Negroes are in a minor

ity or are a minority group in the community, that the

effect of such segregation of children in public schools

would be to adversely affect the personality develop

ment and ability to learn of the Negro ? A. I think that

is generally the case where such segregation exists. ’ ’

Mrs. Trager observed finally that the integration of the

races in the schools was essential to the wholesome per

sonality development of all the children, and particularly

to enable the Negro children to overcome the misconcep

tion of their inferiority which they derived from being

separated from the white children. Specifically, she stated

(218) :

“ In the case of the all-Negro school we had to bring

them to the white school so they could learn that they

were not less good and to show them that these chil

dren would play with them and thus try to correct this

misconception. ’ ’

E. Specific Incidences of Discrimination in Englewood.

In addition to the foregoing evidence regarding the

general problem of the segregated schools at Lincoln, a

number of individual witnesses testified to specific inci

dents tending to show discrimination against Negroes in

the admission of children of their race to other schools in

Englewood.

Mrs. Susanne Anderson, one of the Negro Complainants,

testified that for the past thirteen years she had been

living at 34 Armory Street, which was on the West side of

that street and, therefore, in the Liberty school zone (229,

230, 225). (At page 225 of the transcript of testimony,

the name “ Olney” Street was a typographical error and

should read “ Armory” Street.) Her son, James, was ac

cordingly taken to the Liberty School to register when he

started in 1949, but after about a month, was transferred

15

to Lincoln where he has been ever since (228, 229). Mrs.

Anderson explained that although she thought it was wrong

to transfer the boy to Lincoln, she did nothing until filing

her complaint in 1954 because she had to work six days a

week, her husband had been sick all during this period,

and she, therefore, did not have the time to do anything

about the situation (229, 234). She further testified that

there was a white family named Rivera living a couple of

doors away from her on the same side of Armory Street,

who went to Liberty School, while a colored family named

Hartley upstairs were going to Lincoln during the same

period (230-231).

On cross-examination, Mrs. Anderson emphasized that

the children from her side of the street going to Liberty

School were white and not Negro (234).

Another instance of the same kind was testified to by

Mrs. Hattie Tuck, a Negro, who lived on the West side of

Armory Street in 1950, when her girl, Eileen, started in

school. The girl was registered at Liberty School in Sep

tember 1950, but half an hour later, the Registrar called up

and said, “ She was sorry, but my little girl could not go to

Liberty School because * * * Armory Street was not listed

on the map for the Liberty School” (243-244). Accord

ingly, the child was taken to Lincoln. Mrs. Tuck, like Mrs.

Anderson, thought that her child belonged at Liberty be

cause the “ white children that lived up the street, they went

to Liberty School” (244). The white children included the

Riveras and at least one other family who lived on the

West side of Armory Street (244). Mrs. Tuck likewise

confirmed that while there were not many colored people

living on the West side of Armory Street in 1950, those

who had resided there attended Lincoln School (245).

On cross-examination, Mrs. Tuck further testified that all

children living in her block up through the sixth grade

were supposed to attend Liberty. The following excerpt

from her testimony puts the matter very succinctly (247) :

16

‘ ‘ Q. How many people had children going to Liberty

School in your block? A. Two.

Q. Your child was not accepted in Liberty School?

A. No.

Q. Were the children in your block who were ac

cepted, white? A. Yes.

Q. No Negro children in your block in the Liberty

School? A. No.”

Mrs. Larrine Clark, a Negro, living at 243 Lafayette

Place, which is on the East side of that Street, testified

that she had three children all attending Lincoln School.

In 1949, when she took her oldest child to Liberty School

to register, the Registrar told her that since she lived on

the East side of the street, the child had to go to Lincoln

School (252). She did not take the Registrar’s word for

it, because she thought that the Lafayette Street area was

an optional zone (253), and she knew of some white children

living in the apartment house on the East side of Lafayette

Street at the corner of Third Street, who were going to

Liberty School, also a girl down on Second Street who

was going to Liberty (253), so she took up the matter with

her councilman, Mr. Marston, who advised her as follows

(252) :

“ He said: 41 know people that have tried to get

their kids in Liberty School and it didn’t do no good

and it won’t do no good even for money, you can’t get

her into Liberty School.’ So I took his word and took

her down to Lincoln School and that’s where she has

been since.

Q. And your other children also went to Lincoln

School? A. Yes.”

On cross-examination it was brought out that Mrs. Clark

received a letter from Dr. Stearns on October 8, 1954, tell

ing her that there was no reason why she should not have

her child in the Liberty School (R-2). She did not receive

17

the letter, however, until after she had filed a complaint

with the Division Against Discrimination (257).

Mrs. Sara Williams, another colored resident on the

east side of Lafayette Place, testified that when she first

took her son in 1951 to Liberty School to register him in

the kindergarten, the Registrar said that he had to go to

Lincoln School, and that everyone below Third Street on

the East side of Lafayette Street had to go to Lincoln

(273). That same year there were white children from that

side of the street from the apartment on Third and

Lafayette attending Liberty, and Mrs. Williams under

stood that she also could choose Liberty (273). She went

to Miss Griggs, the Principal of Liberty, who also told her

that her son would have to go to Lincoln (274). There

after, Mrs. Williams got in touch with Dr. Stearns, who said

that the Registrar and Miss Griggs “ were wrong” and that

her son might go to Liberty, which he thereafter attended

(274-275).

Five other Negro mothers residing in the northwest

sector of the 4th Ward, including the Complainant Walker,

gave testimony complaining of the change-over from

Liberty to Lincoln kindergarten in so far as their young

children were concerned.

Additional evidence was adduced tending to show that

the specific incidents related by Mrs. Anderson, Mrs. Tuck,

Mrs. Clark and Mrs. Williams were not a series of unin

tentional mistakes, but were part of a pattern of dis

crimination which had been fostered by successive school

administrations over a long period of years. Among this

evidence was the following*:

(a) The uncertainty which prevailed as to whether the

boundary between Lincoln and Liberty ran down the center

of Armory Street, as shown on the maps prepared by Dr.

Stearns (S-2 and R -l), or down behind the houses on the

west side of that street, as stated in the “ interpretation”

given out by him (S-4). Dr. Stearns testified (361):

18

“ Now apparently there was confusion along Armory

Street which I didn’t know about until quite recently.”

(b) Vagueness as to whether or not a zone of choice

existed on the east side of Lafayette Place. Dr. Stearns

testified that when he came to Englewood, the matter was

“ controversial” (355) and in a state of “ confusion” (356,

357); that there was no record to show that such an area

of choice had ever been officially established by the Board

(357) ; that he “ assumed” that the people knew all about it

(358) ; and that he “ finally arrived at my own decision”

that it was an optional zone (356).

(c) The “ common practice” before Dr. Stearns’ time

of allowing exceptions to the boundary lines so that children

residing in one district might go to school in another. In

the case of graduates of Lincoln Elementary being allowed

to attend Engle Street Junior High, a few Negroes were

given the benefit of such exceptions, but most of them were

made in favor of white children until Dr. Stearns’ regime

began in 1944 (359; S-17).

Questions regarding the Board’s good faith in dealing

with the segregation problem are similarly implicit in the

history of its relations with the Division against Dis

crimination. After the Anderson complaint was filed, the

Division conducted an extensive investigation. Thereupon

it notified Dr. Stearns, by a letter of May 7, 1954 that there

was probable cause to credit the allegations of the com

plaints against the Board, expressed the hope that it could

assist the Board in establishing policies which would elimi

nate the probability of future complaints, and requested a

conference to this end (S-15). That letter led to an in

formal conference between Dr. Stearns and Dr. Milligan,

which was followed by another letter to Dr. Stearns from

the Division, dated May 21, 1954, requesting a conference

with the Board for the purpose of adjusting the com

plaints, if possible (S-12).

Pursuant to this letter a conference between the Board

and the Division was held on June 8, and the next day Dr.

19

Milligan again wrote to Dr. Stearns expressing the feeling

that great progress had been made and that he understood

that the following agreement among others had been

reached (S-13):

“ 1. The Englewood Board of Education will estab

lish and make a matter of official record the school

district lines to become effective in September 1954.

The Board may wish to consult representatives of this

Division although it is understood that the responsi

bility of establishing the district lines is that of the

Board of Education. We are accepting in good faith

the Board’s statement that these lines will be estab

lished so that there will be no discrimination against

students because of race, creed or color.”

The story from there on was testified to by Dr. Milligan

as follows (99-101):

“ In other words, I had accepted in good faith the

declaration of the Board on June 8th, that they would

not establish any new lines that would be established in

a way that would be discriminatory. Now, in my

letter of July 9th, which was a month later, I had to

request—the line, change had been established by the

Board in an official meeting on June 28, 1953* and the

only information I had on that was by reading- it in a

newspaper clipping—and I then requested in my letter

of July 9th that the official action on these changes be

transmitted to the Division. On July 22, 1954, I pre

pared a full summary of my conferences with Dr.

Stearns and the members of the Board, and our at

tempts at conciliation up to July 22nd, 1922.* A new

complaint was received from Mrs. Mary Walker and

on August 4th I was able to confirm a meeting with

the Board on August 10th, for conciliation purposes.

We could not make a thorough investigation to de

termine whether there was discrimination at that time.

Subsequently, on August 19th I summarized the August

* Should read “ 1954” .

20

10th meeting, where the Board refused to conciliate

the matter and I expressed the deepest regret that

there would have to be a public meeting on the matter.

# # #

Q. Would you tell me what you mean by the Board

refusing to conciliate the matter? A. Yes, sir. I had

pointed out to the Board that it would be wise to wait

just one month—this was in the meeting of August

10th—that I would like to have them wait one month

because the lateness of the Board’s declaration of the

new lines did not give our Division time to evaluate

the effects of these new lines in terms of segregation

of students and also advised that a number of my men

were away on vacation. I also pointed out that it

seemed to me that these lines as established for the

kindergarten and first grade, if continued, would re

sult in even greater segregation than had heretofore

existed and I asked the doctor if they could not find

some way to hold the status quo and if that could not

be done, to allow students who had formerly attended

kindergarten in Liberty school to continue their at

tendance there, so that the complainants would be

satisfied and thereafter work out a fair and equitable

solution or plan. The Board refused to rescind its

action and contended these were the only practical lines

that could be drawn and so, after conferences with my

assistants and other Assistant Commissioners of Edu

cation, I recommended a public hearing.”

F. The Defense.

Harry L. Stearns, Superintendent of Schools in Engle

wood, called as a witness on behalf of the Respondent, tes

tified that the new line between the Lincoln and Liberty

districts for kindergarten purposes had been drawn by him

pursuant to instructions of the Board of Education to find

the best method of relieving overcrowded conditions in

Cleveland School and utilizing available space in Lincoln

21

(309). Since the Liberty School lay between the two, the

plan devised was to move northward the boundary of the

Liberty School to take in children from the former Cleve

land district, and to take into Lincoln some pupils who

would otherwise have gone to Liberty (S-3; 308-313, 320).

He denied that in any of his conferences with the Board

concerning this matter the idea of segregation ever entered

into his thinking or discussions (309-310).

On cross-examination, howTever, Dr. Stearns admitted that

he had no reason to doubt that, as shown in Exhibits S-7

and S-ll, only 2 out of 102 children in Lincoln kindergarten

were white and only 1 of the elementary pupils and 1 of

the Junior High School pupils at Lincoln were white (323-

324). He also admitted that he had not made any inquiry

as to the number of Negro and white pupils in Liberty

kindergarten and Lincoln kindergarten under the new lines

(325-326). He acknowledged that it “ may be” true that the

new line makes an approximate division between the white

and colored sections of the Fourth Ward, as shown on

Exhibit S-5, there being no Negro families that he knew

of living on the south side of Palisade Avenue (332-333).

The following excerpt from Dr. Steam’s testimony sig

nificantly shows the failure of either himself or the Board to

consider what result the new lines would have on the racial

situation in Lincoln and Liberty Schools (334-335):

“ Now doctor, isn’t it a fact that the existence of

this old line on the south side of Palisade Avenue and

the extension of that line westerly to the western bor

der of the city, as shown on Exhibit S-3, had the prac

tical effect of removing all Negro children from Lib

erty kindergarten this year and sending them to Lin

coln kindergarten—wasn’t that the practical effect of

that action! A. The figures would seem to indicate

that, but that was not known at that time.

Q. At what time! A. At the time the lines were

drawn.

22

Q. But it did accomplish that fact, did it not, Dr.

Stearns'? A. Yes.

Q. Did you make any inquiry as to what the result

of drawing that line would be, at the time the line was

so drawn? A. I did not.

Q. Did any member of the Board, in any Board meet

ing you attended, raise any question as to what would

be the result racially insofar as the Lincoln School was

concerned? A. No sir, I don’t recall that the question

was ever raised at any of the Board Meetings I at

tended on that subject—that is, the subject of drawing

new lines.

Q. And it was never discussed by you with any of

the members of the Board? A. No.”

Board President Fitzpatrick (394) and two other Board

members—Mr. Cramer (271-2) and Mrs. Wolpert (386),

also denied that the subject of segregation had ever been

discussed, formally or informally, at any Board meeting

attended by them. However, another Board member, Gen

eral Stratton, admitted that at least in respect to the Junior

High School the Board had considered the problem of the

racial make-up of Lincoln “ as a general one in our com

munity” (263).

Whether or not the Board discussed the subject of segre

gation at Lincoln Elementary, they were well aware of

the problem. Dr. Stearns frankly admitted it, thus cor

roborating Complainant’s evidence on this point. After

conceding that a number of citizens had appeared at a

Board meeting and talked about the racial situation at Lin

coln (381), Dr. Stearns testified (382-383):

Q. * # * Did any Board member, at any particular

meeting, discuss or mention the fact that Lincoln was

a particularly (should be “ practically” ) all-Negro

school? A. Board members had been generally con

scious of the fact that due to the nature of the area,

which they had no control over, largely Negro children

go to that school and that it is largely a Negro school.

23

This has been recognized at one of the meetings but

I cannot tell you the date of the meeting when it was

discussed.

Q. But the Board members have been generally con

scious that this is nearly an all-Negro school! A.

Yes.”

The Superintendent also acknowledged that he and mem

bers of the Board had discussed the proposals of both Dr.

Milligan and Dr. Giles for bringing about de-segregation

(383).

In short, the Respondent’s own evidence shows that the

Board and Dr. Stearns had been fully conscious of the

racial problem in the Lincoln Schools when the new line

between Lincoln and Liberty kindergartens was determined

upon in June 1954 (271, 263, 382, 394).

Summary of Argument

The testimony and exhibits established beyond question

that between September 1949 and the present time, in viola

tion of Section 11(f) of the Law Against Discrimination

(N.J.S.A. 18:25-12) and pursuant to a persistent plan and

scheme, the Respondent has unlawfully discriminated

against members of the Negro race in the admission of

pupils to its schools by:

I. Maintaining without just cause the Lincoln Elemen

tary School as a substantially all-Negro school, thereby

unlawfully discriminating against all colored children, in

cluding the Complainant Anderson’s child, who were obliged

to attend that school;

II. Establishing a new attendance zone line between

the Lincoln and Liberty districts so as to enlarge and ex

tend Lincoln Elementary as an almost exclusively Negro

school, thus discriminating against the Complainant Walk

er’s child and others similarly situated;

24

III. Maintaining without just cause a separate and vir

tually all-Negro Junior High School for students residing

in Lincoln District, while sending students from all other

elementary districts to Engle Street Junior High School,

the student body of which is predominantly white;

IV. Causing Negro children to attend the Lincoln

schools, while white persons similarly situated were sent

to Liberty or Engle Street Schools, through such devices

as maintaining indefiniteness as to zone lines, allowing

exceptions to the lines as established, and giving a choice

of schools to white persons but not to Negroes similarly

situated; and specifically, sending the Complainant Ander

son’s child and other Negroes similarly situated to Lin

coln Elementary School, while white children from the

same zone were sent to the Liberty School.

Each of the foregoing violations will be treated under a

separate Point, in the order above listed.

Point I involves essentially the question whether pass

ively permitting a substantially all-Negro school to exist,

when it can by reasonable measures be avoided, constitutes

unlawful discrimination. Point II involves a positive act

by the Board which resulted in enlarging and extending

an almost exclusively Negro school, while Point III con

cerns the maintaining of a colored school which resulted

from deliberate and intentional segregation by a predeces

sor board or boards. Points II and III can be decided in fa

vor of the Complainants without a favorable decision on

Point I. We take the latter Point first because, if it is de

cided in favor of the Complainants, it would necessarily

carry Points II and III along with it, and would sustain the

principle of compulsory de-segregation of minority racial

groups in our public schools.

Point IY deals with particular acts of discrimination

against certain individuals rather than with the general

problem of school districting.

25

P O I N T I

The Respondent unlawfully discriminated against

all Negro children who were being obliged to attend

Lincoln Elementary School during the school year

1953- 1954.

The undisputed evidence at the hearing showed that as

of the school year 1953-1954 there was only one white

child in the Lincoln Elementary School out of a total

enrollment of 331. It also appeared that the old line of

demarcation between Lincoln and Liberty Elementary Dis

tricts had been in existence for many years, and there

was little evidence that the line as originally drawn was

discriminatory. We may assume for the purposes of this

Point that the Negro character of this school was brought

about primarily through the influx of Negro residents and

the removal of whites from that zone, and not because of

any actions taken by the Board (although, as we shall later

show, the allowance of exceptions and irregularities by

earlier boards may have accelerated the segregation pro

cess). Such a state of separation of school children along

racial lines we may term “ segregation-in-fact” , denoting

the actual situation regardless of how it was brought about.

The question posed by this Point I is whether the seg

regation of school children in fact, when it can by reason

able measures be avoided, constitutes unlawful discrimina

tion where it has occurred as a result of events not par

ticipated in or contributed to by the school authorities.

We submit that the answer to this question should be in

the affirmative.

A. The Responsibilities of a Board of Education

The authority of a school board to establish separate

schools within the district and to fix the zones of attend

ance for each school is found in Section 18:11-1 of the

Revised Statutes, which reads as follows:

26

“ Each school district shall provide suitable school

facilities and accommodations for all children who re

side in the district and desire to attend the public

schools therein. Such facilities and accommodations

shall include proper school buildings, together with

furniture and equipment, convenience of access thereto,

and courses of study suited to the ages and attain

ments of all pupils between the ages of five and twenty

years. Such facilties and accommodations may be pro

vided either in schools within the district convenient

of access to the pupils, or as provided in sections 18:14-

5 to 18:14-9 of this title.”

Sections 18:14-5 to 18:14-9 deal with attendance of pupils

in an adjoining district because of remoteness from school,

and with transportation of pupils to and from school. These

statutes are not pertinent to the present discussion.

In determining where to locate schools within the district

and what pupils to send to them, it is proper for the Board

of Education to consider such factors as convenience of

access to the respective schools as determined by distance

to be traveled from home, the topography of the country,

the condition of roads, and the like; the necessity of cross

ing highways, railroads or other facilities vdiich might

involve danger to children and require police protection;

the availability of space in existing or proposed buildings,

and the crowded condition of classrooms; the cost of new

facilities, transportation and similar factors. For the sake

of convenience, the items just enumerated may be termed

the physical factors which the Board should consider in

drawing the lines betvTeen zones of attendance.

In addition, however, the Law against Discrimination

(Chapter 169, P.L. 1945, as amended) prohibits discrimina

tion in the admission of pupils to any public school on ac

count of race. Section 11 of the law (N.J.S.A. 18:25-12(f))

makes it an unlawful discrimination for the owner or op

erator of “ any place of public accommodation” , in extend

ing the privileges and facilities thereof, to discriminate

27

against any person on account of race, creed, color, national

origin, or ancestry. The term “ place of public accommo

dation” is defined in the law (N.J.S.A. 18:25-5(j)) as in

cluding “ any kindergarten, primary and secondary school,

trade or business school, high school, academy, college and

university, or any educational institution under the super

vision of the State Board of Education, or the Commis

sioner of Education of the State of New Jersey.”

The New Jersey Education Law has also long provided

that “ no child # * shall be excluded from any public

school on account of his religion, nationality, or color.”

B.S. 18:14-2.

One form of discrimination on account of race or color is

deliberate segregation, even though the physical facilities

in a segregated school may be equally as good as those of

any other school in the district. The Law against Discrimi

nation must be so construed when read, as it has to be, in

the light of the New Jersey Constitution, Article 1, para

graph 5. That paragraph expressly provides that:

“ No person shall be denied the enjoyment of any civil

or military right, nor be discriminated against in the

exercise of any civil or military right, nor be segre

gated in the militia or in the public schools, because

of religious principles, race, color, ancestry or national

origin. ’ ’

The statute must also be read in the light of the recent

decisions of the United States Supreme Court in Brown v.

Board of Education, 347 IT . S. 483; and Bolling v. Sharpe,

347 U. S. 497, both decided in 1954. In holding that state

laws requiring or permitting segregation of children in

public schools solely on the basis of race is a violation of

both the equal protection clause and the due process clauses

of the United States Constitution, the Court said in the

Brown case (pp. 493-495):

“ In Sweatt v. Painter, supra, (339 U. S. 629), in find

ing that a segregated law school for Negroes could not

28

provide them equal educational opportunities, this

court relied in large part on ‘ those qualities which are

incapable of objective measurement but which make

for greatness in a law school.’ In McLaurin v. Okla

homa State Regents, supra, (339 U. S. 637), the court,

in requiring that a Negro admitted to a white graduate

school be treated like all other students, again resorted

to intangible considerations; * * *‘ his ability to study,

engage in discussions and exchange views with other

students, and in general, to learn his profession.’

Such considerations apply with added force to chil

dren in grade and high schools. To separate them from

others of similar age and qualifications solely because

of their race generates a feeling of inferiority as to

their status in the community that may affect their

hearts and minds in a way unlikely ever to be undone.

The effect of this separation on their educational op

portunities was well stated by a finding in the Kansas

case by a court which nevertheless felt compelled to

rule against the Negro plaintiffs:

‘ Segregation of white and colored children in public

schools has a detrimental effect upon the colored chil

dren. The impact is greater when it has the sanction

of the law; for the policy of separating the races is

usually interpreted as denoting the inferiority of the

Negro group. A sense of inferiority affects the motiva-

ation of a child to learn. Segregation with the sanction

of law, therefore, has a tendency to retard the educa

tional and mental development of Negro children and

to deprive them of some of the benefits they would

receive in a racially integrated school system.’ * * *

“ We conclude that in the field of public education

the doctrine of ‘ separate but equal’ has no place. Sepa

rate educational facilities are inherently unequal.”

# # *

It thus seems incontrovertible that deliberate segrega

tion “ because of race” within the meaning of the New Jer-

29

sey Constitution and within the prohibition of the Federal

Constitution, is also a violation of the Law against Dis

crimination.

With this principle established, the question arises

whether the Law goes further and prohibits a board of

education from permitting the existence of segregation-in-

fact when it can reasonably be eliminated. We believe that

the Law against Discrimination should be so construed.

B. Permitting Unnecessary Segregation is Discrimination

In determining the meaning of a statute, we must look

to the mischief which the law is designed to overcome.

Blackman v. lies, 4 N. J. 82, 89 (1950); Doremus v. Board

of Education of Hawthorne, 5 N. J. 435, 453 (1950). As

the New Jersey Supreme Court said in the last cited case

(p. 453):

“ It is a cardinal rule in the construction of consti

tutional and statutory enactments that the provision

made by way of remedy shall be studied in the light

of the evil against which the remedy was erected. ’ ’

The nature of the evil of segregation-in-fact was well-

expounded by Mrs. Trager in her convincing testimony at

the hearing, where she explained, as hereinbefore noted,

that by being separated from their white contemporaries,

the Negro children come to feel inadequate or incompetent,

which in turn makes it less likely that they will be able to

cope with the problems of learning and of achieving a sat

isfactory personality development. The effect of such sepa

ration is bad, she said, whether or not it has been brought

about by law (216).

This same harmful effect of segregation-in-fact was also

implicit in the reasoning of the U. S. Supreme Court in

the Brown case, as above noted, where the court referred

to several authorities on the psychological effect of such

separation on the Negro pupils. The court noted that the

30

impact of the segregation was “ greater when it has the

sanction of law” ; but by the same token, when it has the

sanction of the agency charged with administering the law,

the impact on the pupils involved would be at least as dam

aging.

It is immaterial that the racial composition of a segre

gated school may have been caused solely by residential

concentration of Negroes. As in Englewood, there are

many communities where residential segregation is the

order of the day. Negroes in such communities are gen

erally compelled by social and economic factors to live in

one or more well-defined areas which tend to become solely

Negro, while at the same time other areas tend to remain

almost exclusively white. See Ashmore, The Negro and

the Schools (1954), especially pages 76-77. If the bound

aries of attendance districts are drawn on a purely physi

cal basis, the evil of separation of races in the schools, as

well as in residence, will be perpetuated as a matter of

course.

In view of the evil at which the anti-segregation laws are

directed, we submit that they require the Board of Educa

tion to do more than merely draw the zone lines according

to the physical and economic factors alone. The Board

must take cognizance of the racial situation, and take all

reasonable steps to avoid separation of the races and to

bring about integration in the schools under its jurisdic

tion. To allow segregation-in-fact to persist in the schools

merely because of residential factors would be to thwart

the purposes of the New Jersey Constitutional provision

and of the equal protection and due process clauses of the

United States Constitution as interpreted by the Supreme

Court. The interpretation and application of the principle

of non-segregation must take into account the actual con

ditions in which the principle is to operate and the harm

which it is designed to avoid.

We conclude, therefore, that the term “ discrimination on

account of race” as used in the Law against Discrimination,

31

and the term ‘ ‘ segregation because of race ’ ’ as used in the

New Jersey Constitution, should not be narrowly confined

to cases where a harmful division of the races has resulted

from a deliberate purpose or intent to bring it about. Those

terms must be construed in the light of the statutory re

sponsibility of the Board, under R.S. 18:11-1, to furnish

suitable educational facilities for all public school children

in the district, and in the further light of the constitutional

responsibility of the Board to provide such facilities to all

children on an equal basis, psychological as well as physical,

so far as reasonably possible. We submit that the failure

of the Board to perform these statutory and constitutional

obligations, either knowing or having reason to know that

such neglect of duty will result in substantial racial segrega

tion in one or more of its schools, constitutes “ Discrimina

tion on account of race” and “ Segregation because of

race” within the meaning of those phrases in the Law

against Discrimination and the State Constitution, re

spectively. To put it another way, segregation “ on account

of race” or “ because of race” means causing or permitting

children of one race to be set apart in the school system

from those of another race where it would be feasible to

avoid such a division.

We do not maintain here that complete integration must

be achieved at all costs, so that in every school the pupils

would represent a fair cross section of all races in the

district. Financial, transportation and other problems in

volved in such a program might be insuperable. We do not

believe that the constitutional requirement of de-segrega

tion necessitates a disregard of physical and financial con

ditions in the school district.

The guiding principle, we submit, is that the Board of

Education should establish, and where necessary alter,

zones of attendance in such a manner as to eliminate racial

segregation so far as possible consistently with due regard

for physical and economic factors. This principle requires

32

the Board to act whenever necessary to prevent segrega-

tion-in-fact from becoming entrenched; and it further de

mands that whenever the Board does take any action to

construct new schools, change attendance zones, or other

wise to determine where children shall go to school, such

action must be taken in accordance with the de-segregation

objective.

The application of these basic rules to any particular

case involves the determination of how far the predomin

ance of Negroes in a school may be allowed to progress

before the due to de-segregate arises. For example, must

the Board act after the ratio of colored to white is more

than one-half! Or more than 80 percent?

The solution to this problem would seem to be this:

The Board must act whenever, under the particular cir

cumstances, the ratio has become such that the Negro

children are being denied educational facilities which are

equal, intangibly as well as tangibly, with those afforded

to the whites. The controlling object is always to provide

all children with the best possible opportunity for psycho

logical and personality development. Just when the injuries

of racial segregation begin to be inflicted is a question

which, in the first instance, must be decided by the Board

in each case in the honest exercise of reasonable judgment,

with the help of such expert advice as may be available. So

long as reasonable men might differ in judging a particular

situation, the discretion of the Board should not be dis

turbed.

Where, however, a school has become all Negro but for

one or two children, while there are other schools nearby

which are predominantly white, the harmful effect on the

pupils of the colored school can no longer be disputed.

Furthermore, where the State authorities have advised the

Board that the racial segregation in its schools is unreason

able and should be remedied, the Board should abide by

the judgment of the State authorities unless it proves that

33

the State is wrong. In the case of Englewood, therefore,

one can no longer doubt the Board’s duty to remedy the

situation if at all possible.

C. Segregation at Lincoln Can Be Eliminated

As we have already seen, both Dr. Milligan and Dr.

Giles testified that the problem of segregation at Lincoln

Elementary could be solved.

Both of these experts recommended the Princeton Plan

as one possible solution, for the time being at least. Under

this plan, Liberty and Lincoln Elementary Schools would

be consolidated into one district, with the lower grades

going to Liberty and the upper to Lincoln (124). The only

excuse that Dr. Stearns could give for not adopting this

Plan was “ the traffic problem in Palisade Avenue” (321).

He admitted, however, that Palisade Avenue west of the

monument at Liberty School was a residential street -with

out much traffic (338), and that children coming up from

the south side of the street could and did safely cross to

Liberty under police protection at the monument (338).

Under police protection, some six or seven children who

live on the south side of Palisade Avenue and east of

Lafayette Avenue already cross one of those heavily trav

eled arteries in order to go to Liberty School (338). It

is true that the heavy traffic on Palisade Avenue east

of the monument comes in via Englewood Avenue and

Lafayette Avenue (342). However, under the new zone

line between Lincoln and Liberty, children from the Fourth

Ward north and west of those traffic arteries would be

obliged to cross them to travel to and from Lincoln School.

If such east-west travel by children going to Lincoln was

not a sufficiently serious obstacle to the establishment of

the new boundary line, it could hardly be a serious objec

tion to similar travel by children in the southeast sector

of the Fourth Ward going up to Liberty.

34

Dr. Milligan also suggested taking pupils from north

and east of the old Lincoln District, with additional police

protection at traffic crossings if necessary (76). Here

again, Dr. Stearns’ reasoning was reduced on cross exam

ination to the assertion that Dr. Milligan’s plan would

aggravate the problem of traffic jams, there having been

little trouble getting police protection (344). A visit to

Palisade Avenue, however, will disclose that there are

traffic stop lights at the intersections of that avenue with

Grand Avenue, Dean Street and West Street. In any event,

moreover, north-south traffic must be stopped at intervals

to make way for east-west traffic, and vice versa. The cross

ing of children while traffic was thus stopped would ob

viously make little or no difference in the time that traffic

was held up.

Finally, even if there would be minor increases in traffic

congestion problems if one of the plans suggested by the

experts were adopted, that is not a sufficient reason for dis

carding attempts at de-segregation. It would require in

deed a distorted sense of values to maintain the position

that the mental and emotional development of a large

segment of our youth is to be sacrificed for the sake of

a few minutes of automobile traveling time.

Also available to the Board was Dr. Giles’ recommenda

tion, as a long range plan, to discontinue Lincoln Elemen

tary and to absorb its population in other schools, possibly

with transportation being provided (124). We have no

doubt, furthermore, that the Respondent could devise other

plans of its own which would achieve a satisfactory degree

of de-segregation.