Opinion and Order from Judge Pittman Denying Petitioners' Motion for Reconsideration and Motion to Intervene

Public Court Documents

December 15, 1976

13 pages

Cite this item

-

Case Files, Bolden v. Mobile Hardbacks and Appendices. Opinion and Order from Judge Pittman Denying Petitioners' Motion for Reconsideration and Motion to Intervene, 1976. d1f01a93-cdcd-ef11-b8e8-7c1e520b5bae. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/34938057-6f9f-4e3c-aa2c-b17ae2ed4492/opinion-and-order-from-judge-pittman-denying-petitioners-motion-for-reconsideration-and-motion-to-intervene. Accessed February 22, 2026.

Copied!

w 4

%

N

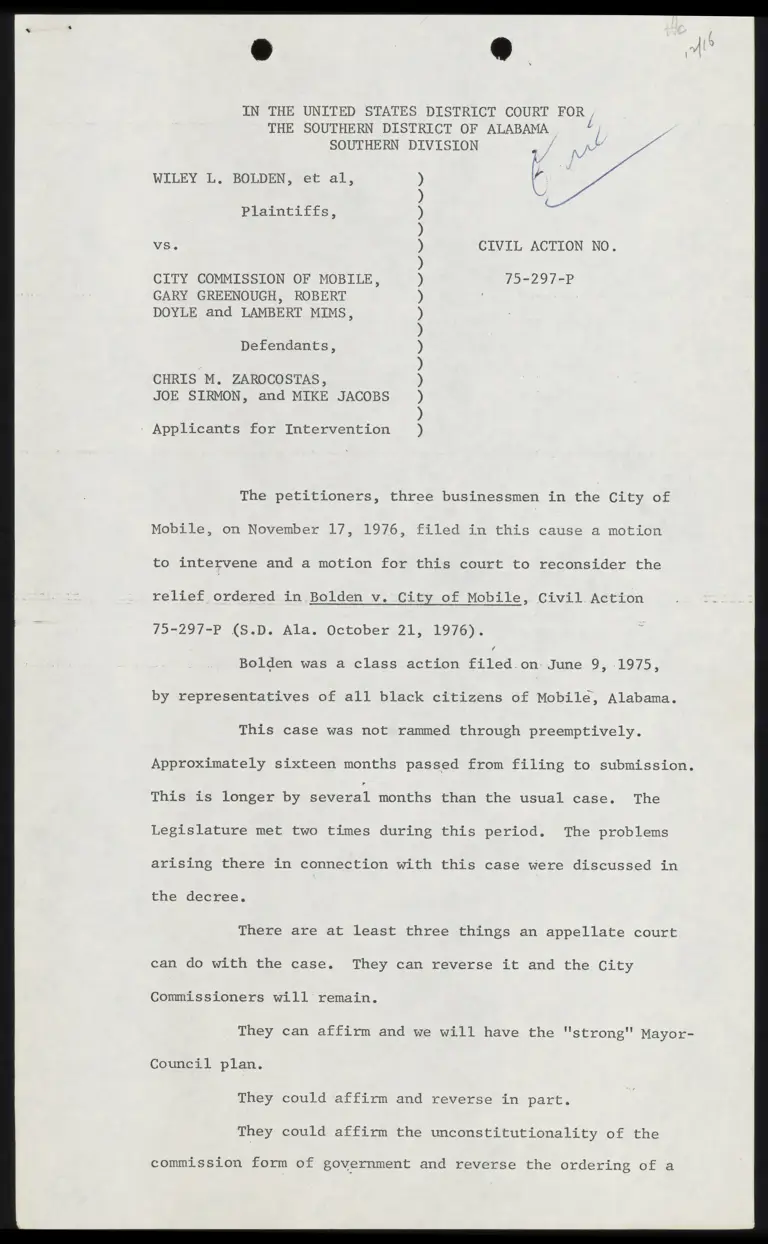

IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR

THE SOUTHERN DISTRICT OF ALABAMA |

SOUTHERN DIVISION aa a

1 A

WILEY L. BOLDEN, et al, ¢ gf

Plaintiffs,

VS. CIVIL ACTION NO.

CITY COMMISSION OF MOBILE, 75-297-P

GARY GREENOUGH, ROBERT

DOYLE and LAMBERT MIMS,

Defendants,

CHRIS M. ZAROCOSTAS,

JOE SIRMON, and MIKE JACOBS

N

e

?

Na

e

N

a

N

o

?

N

a

N

u

N

a

N

o

N

o

N

o

N

o

N

o

N

a

N

o

N

o

N

o

- Applicants for Intervention

The petitioners, three businessmen in the City of

Mobile, on November 17, 1976, filed in this cause a motion

to intervene and a motion for this court to reconsider the

relief ordered in Bolden v. City of Mobile, Civil Action

75-297~P £S.D. Ala. October 21, 1976).

Bolden was a class action filed on: June 9, -1975,

by representatives of all black citizens of Mobile, Alabama.

This case was not rammed through preemptively.

Approximately sixteen months passed from filing to submission.

This is longer by Several months than the usual case. The

Legislature met two times during this period. The problems

arising there in connection with this case were discussed in

the decree.

There are at least three things an appellate court

can do with the case. They can reverse it and the City

Commissioners will remain.

They can affirm and we will have the "strong" Mayor-

Council plan.

They could affirm and reverse in part.

They could affirm the unconstitutionality of the

commission form of government and reverse the ordering of a

|

»

"strong' mayor-council plan and order the court to order the

present commission form change to a "weak-mayor'' council plan

with 15 to 20 single-member districts plus a Council President.

This was discussed in conference with the attorneys.

The court stated then it could see little difference in ordering

the commission to order a change to one plan and this court

ordering a change to another plan.

I further told them all I wanted was a constitutionally

sound city government and if I ordered a change it would be to

oné which all the evidence affirmed was far superior, a strong .

Mayor-council plan, rather than a weak plan with 15 - 20 members

and a council president which would be chaotic. If a change was

to be made, I would only order a change to a good plan and what I

hoped was Bost for our home, the City of Mobile.

During the progress of this case, it was suggested that

if the court had to run for office, its decision might be

different from what it has been. I take that remark as a light

humorous reference cautioning me to be restrained in the City's

favor. I am sure that no one would want, or expect, a judge to

prostitute his office and interpretation of the law to seek the

applause of a probable majority. If this court should take such

a view, I would be violating the very instructions which I have

given time and again to jurors - ''You are to perform your duty

without bias or prejudice to any party. The law does not permit

you to be governed by sympathy or prejudice, or public opinion.

The parties and the public expect that you will carefully and

impartially consider all the evidence, follow the law, and

reach a just verdict regardless of the consequences."

“De

I would be a poor judge not to take to heart and

follow the very instructions I have given so many jurors,

The request has been made to permit your intervention

for this court's reconsideration. This case was filed on June

9, 1975. It was tried in July of 1976, and arguments were

heard in September 1976. The complaint first filed requested

a change in the form of the city government, i.e., for a form

using single-member districts. This was no secret. The commissioners

recognized the only way to do this was by a change to a mayor-

council plan in a pretrial document filed by them in February

1976... Considerable testimony .was. taken concerning this proposal

in July of 1976 and arguments were made by the attorneys representing

the city commissioners in September calling to the court's attention

that two previous elections on a mayor-council form of government

“iihad been defeated. It was also called to the court's attention.

that the plans called for a '"weak' mayor-council form and that a

aestrong! mayor-council plan had baontbokited up in.committee in:

the 1976 legislature. The court discussed in its decree the pro-

blem of lack of access of blacks to the political process because

of the polarization of the white and black vote. The decision

also discussed the pecan in the legislature and the results in

the past when the issue has taken on a white/black colorization.

Suppose this court were to accede to your request and

the issue were submitted to a vote of the people and the mayor-

council plan was defeated. The court would be placed in the

position of having found the structure of the present form of

government unconstitutional and yet the majority of the people

had defeated a proposed change. Would the aggrieved parties

be left without a remedy or would the court then have to

order a change? The court discussed in its decree the

seriousness of a change of government and concluded the evils

of racial discrimination present could not be corrected by

anything less than the ordered change.

The United States Constitution represents a compact

made by the people among themselves. It established a govern-

ment democratic in principle in that the government is responsible

to the people, but a republic in structure, as Franklin stated

when leaving Independence: Hall and was asked what they had given

the people, - "A Republic, Madam, if you can keep it." This

compact the people made with themselves basically limits the

power of the government to protect the rights of the people but

‘also in avoral places limits the power of the majority and

protects the rights of minorities. These basic Sarn Shey in

this compact made by the people and confirmed for almost 200 years

by their Holes, Wes considered so precious that incorporated in

the Constitution the will of the majority is limited in that it

takes 2/3 majority to propose and 3/4 majority to amend it.

Majority in both Houses of Combes to propose amendments,

or the application of the legislaturesof 2/3 of the States to

call a convention for proposed amendments, but in either event,

then must be ratified by the legislatures 3/4 of the states, or

by conventions in 3/4 of the states before it can be amended.

The will of the majority, as expressed through their

representatives in Congress, can be limited by a Presidential

veto. Many people in this area applauded the repeated exercise

f=

of the veto power of the presidential candidate they expressed

a preference for in the recent elections. To overcome this

limitation on the expression of the majority, a 2/3 vote in

both Houses 1s necessary.

It has been suggested that this court has violated

the Constitution of the State of Alabama. On several previous

occasions, provisions of the Constitution of the State of

Alabama have been nulified when found to be in conflict with

the Constitution of: the United States. Article 6 of the

Constitution of the United States in part reads -

"This Constitution and laws of the United States

which shall be made in pursuance thereof...shall be the

supreme law of the land; and the judges in every State shall

be bound thereby anything in the Gonseliibion or laws of any

State to the contrary notwithstanding."

VIABLE 'T ‘am a great admirer of former president Harry Truman.

After he left the White House he visited Decatur and made a

.public address. I wanted to see him and hear what he said.

At that time, few if any blacks in Alabama could vote. As I

recall it, it was not long after the Supreme Court's school

desegregation decision in 1954, but, in any event, the rights

of the blacks in the old concept of white supremecy tore hot

political issues in the State. 1 recognize, as he then

recognized, that matters of racial discrimination and changing of

social and political customs are a ''searing'' experience for us.

There is a great danger in simplifying and generalizing

in a case with the complexities of this case. If I had to put

in as few words as possible the thrust of my decision I would se-

lect two short portions. The at-large election of the city

commission "operates to minimize or cancel out the voting strength

of (the) racial (i.e.black)... voting population; and "results

in an unconstitutional dilution of the black voting strength.

Eo

* »

It is 'fundamentally unfair'', and the "moving spirit present

at the conception of this nation, all men are created equal"

(from the Declaration of Independence) will not rest and the

great purpose of the Constitution (as expressed in its preamble)

to “establish justice, insure domestic tranquility, ... and

secure the blessings of liberty to ourselves and to our

posterity..." will only be a dream until every person has an

opportunity to be equal. To have this opportunity, every person

mist ‘be treated equally. This includes being treated equally in

the electoral process. Because of the present structure of

the city government, more than 1/3 of this city's population has

'no realistic opportunity to elect persons to its governing body,

to pass laws, including taxes, and make regulations affecting

their day to day living and touching them more intimately than

those passed by Congress.

What if this court, against its better judgment, caved-

in to public outcry and reversed its order or provided for :

an election - would that accomplish what you seek? I doubt it.

The plaintiffs to this lawsuit have the same right of Afeal as

the defendants. In all likelihood, they would appeal this court's

order. If I should follow such a procedure, it is my judgment I

would hold out false hope to you as well as prostitute my in-

tellectual honesty. If you were sick and needed an operation,

would the doctor be doing you a favor to misrepresent to you your

physical condition and deliberately give you an erroneous diagnosis

which resulted in a serious impairment of your health or death?

Of course not. He would be a quack, and I would be a phony.

I have always taken solace in the built-in safeguards

of our judicial system. My judgment in this matter is not the

last and final word. There are two higher courts to which

this matter can be presented and argued. The first Appellate

court, the Fifth Clrdiie Court of Appeals, is composed of fifteen

judges who live in states from Texas to Florida. If I am wrong,

they will correct me. Then if the parties desire further appeal,

it can be presented to the Supreme Court of the United States

which is composed of nine judges selected from among the 50

states. "If elther this court, or the Fifth Circuit. Court of

Appeals is in error, they will correct us.

The people are ultimately soverign. If the Constitution

does not represent the wishes of this nation, it can be amended.

It-isva great. .system. I believe in it. Whoever is right, that

concept of 'right-can ultimately be vindicated by the people.

In their motion to Intervene, petitioner's claimed

their Fourteenth Amendment due process rights were violated

because they did not anticipate that the form of governient would

be changed and consequently did not seek to intervene in the suit.

In the motion to reconsider, they assert their First

and Ninth Amendment rights have been violated as a result of the

order to change the governmental form and seek to have this court

consider varied remedy alternatives in order to maintain the com-

mission form of government. Movant's do not take issue with the

holding that the commission form as practiced in Mobile invidiously

discriminate against blacks.

I. INTERVENTION OF RIGHT

Intervention under Rule 24, FRCP, is divided into

two categories: intervention of right [Rule 24(a)] and permissive

intervention [Rule 24(b)]. Petitioners seek intervention under

either category.

%

Intervention of right, Rule 24(a), as amended in

1966, is a question of law for the court to determine. The

rule sets forth the standards that an intervenor must meet.

These are:

(1) The movant has an interest relating to the

property or transaction involved in the action;

(2) disposition of the action may as a practical

matter impair his ability to protect his

interest;

(3) movant's interest is not adequately represented

by the present parties.

Additionally, as set out in the first sentence of Rule 24(a)

and (b), the motion must be timely.

The court- examines these criteria to determine whether

the movant can intervene as a matter of right. First, to have

a sufficient interest to intervene as of right, movant must have

a "...direct, substantial, legally protectable interest in the

proceedings. Hobson v. Hansen, 11 F.R. Serv. 2d. 24a.2 (D.D.C.

1968); 3B Moore's Federal Practice Para. 24.09-1[2] . Petitioner

seems to claim he has a vested constitutional right in operating

under the present city commission form of SOvernment. To reiterate

the holding of Bolden, that the commission form of government as

practiced in Mobile is unconstitutional, dispenses with the

problem. No one person or entity has a vested or constitutional

right to live or operate under an unconstitutional government.

Further, petitioner desires to propose operational modifications

in the commission form of government, intending to maintain

the essences of the commission government. The court in Bolden

rejected creation of districts from which commissioners would

run, and other cosmetic changes, to solve the city's constitutional

problem. It follows the relief sought in order to maintain a

government that has been found unconstitutional, petitioners

have no legal protectable interest. The petitioners meet

neither the first or second requirement of Rule 24(a) (2).

Petitioner claims their particularized interests are

not adequately represented by the defendants. Martin v. Kalvar

Corp., 411 ¥.2d 552, 353 (5th Cir. 1969) sets out several

criteria to measure this claim. Is there any collusion between

plaintiffs and defendants? Does the defendant (City of Mobile)

have an interest adverse to that of the movants? Are the defendants

guilty of nonfeasance in defending the action?

The petitioners proposals were considered in this

court's order. The defendants adequately protected movant's

interests. See Spangler ¥. Board of Education, 427 F.2d 1352

(9th Cir. 1970) cert. den. 402 U.S. 943 (1971), parents sought

intervention in school desegregation case after judgment were

found to have ‘their interests adequately protected by the school

4

board even though the board refused to appeal the district court

order. =

II. PERMISSIVE INTERVENTION

Rule 24(b), FRCP, governs a permissive right. It is

largely one of trial Gonenionde and a court may properly deny

unless made in a very early stage of the proceedings. 3B Moores

Federal Practice Para. 24.13[1] at 24-521. Permissive intervention

seeks to reduce duplicity of lawsuits. Rule 24(b) is the

corollary of permissive joiner [Rule 20]. Keeping in mind the

liberal interpretation that should be given the Federal Rules

of Civil Procedure, movant must show:

(1) They have a claim or defense in law or fact

in common with the main action; and

(2) The intervention should not unduly prejudice

the adjudication of the rights of the original

parties.

~O

A common question of law or fact involves more than a mere

general interest. Courts, in determining whether there is a

sufficient interest to seek intervention, seemingly gauge

their decision upon whether the movants legal or factual claim

in common with the principle action would, if an independent

action, be affected by the doctrine of stare decisis. Wright and

Miller at Sec. 1911. The court, in its discretion, can allow or

refuse intervention, based upon a determination of the presence

or lack of prejudice to existing parties. The movants have a

question of law or fact in common with the principle action.

It is clear that prejudice would visit both existing parties if

intervention, nearly one month after judgment and four months

after trial, were allowed. Petitioners 24(b) motion for

permissive intervention is DENIED.

ITI. TIMELINESS

A significant question that must be answered, under

both Wtesvention of right and permissive intervention, is

whether the movant filed his motions in a timely manner. The

Rules do not define "timeliness" and, absent abuse, it is

within the court's discretion to determine whether the motion

to intervene was timely filed. McDonald v. E. J. Lavino Co.,

430 F.2d 1065, 1071 (5th Cir. 1970); 3B Moores Federal Practice

Para. 24.13[1] at 24-524 (1976). In the Bolden controversy,

the complaint was filed on June 9, 1975. Publicity surrounded

the filing of the suit. The requested relief by plaintiffs was

the imposition of single member districts from which to elect

city representatives. Plaintiffs in July 1976, prior to trial,

-10~

filed districting plans that divided the city into nine

separate districts. The implementation of these plans would

necessarily require a change in the form of city government.

There was sufficient publicity to charge any interested party

with notice. At the time of trial, July 1976, the news media

devoted extensive coverage to the suit, prior to, during, and

after trial. At the trial, the court informed the parties that if

plaintiffs prevailed, a change in the form of Mobile government

was possible. The court reminded the parties the legislature

was in session. Evidence presented during the trial developed

that a mayor-council bill was pending in the current legislative

session. The court put the parties on notice as to the age of

the case and the court would not be disposed to further delay

the case after arguments in September for another annual legis-

lative session. Therefore, if they sought legislative corrective

action, it should be done in the current 1976 legislative

session. The media again provided liberal coverage. The court's

opinion was released on October 21, 1976. Nearly a month elapsed

between the signing of the order and the filing of the petitioners

Motion to Intervene. During the interim, the Bolden opinion

elicited protracted reaction, both publicly and privately. The

issues had been full litigated and the relief granted was in

substance similar to that requested in the complaint. Petitioner

does not claim his lack of knowledge of the suit; rather, they

state that only after the order did they realize that the

plaintiffs actually litigated a meritorious case, and the court

should permit intervention and reconsider its order.

-11-

Intervention is usually denied when substantial

discovery has occurred, 3B Moores Federal Practice Para.

24.13[1] at 24-523, and after judgment, intervention is "...

unusual and not often granted." Id. at 24-526. Extraordinary

or unusual circumstances must justify such intrusion. Sohappy

v. Smith, 529.-7.24 570, 374 (9th Clr. 1976), The rationale

of denial in such circumstances, when the motion to intervene

follows the judgment, is that

(1) the existing parties rights would be prejudiced,

and,

(2) there would be substantial interference with

the orderly processes of the court. McDonald,

supra, 430 F.2d at 1072.

To allow petitioners to intervene would prejudice

the existing parties. The legal activity by both sides

stretched beyond a year. It is reported that approximately

$100,000 in costs and attorney fees have accrued for only the

defendants. At the time of petitioners' oral argument the

notice of appeal had been filed. The court-implemented proposed

mayor-council plan had been. received and o hosting on 16 set this

month. Elections are regularly scheduled for August 1977, only

ten months from the release of the’ order.

Petitioners seek sinty to ninety days for their ideas

on city government to be considered. To permit this would

delay appeal with the probability the Court of Appeals would

not have an opportunity to review this court's action prior

to the August election. Clearly, to allow intervention would

interfere with the orderly process of the court.

Under either intervention as a matter of right or

«1 2=

permissive intervention, the motion has not been timely

filed.

The validity of petitioners' motion for re-

consideration hinges upon the granting of their motion

to intervene. The denial of their intervention motion

necessitates a denial of their motion for Reconsideration.

MOTIONS DENIED.

, : V/

DONE, THIS THE /4 42 DAY OF oer.

1976.

GA) of 9/4 FA

UNITED STATES DISTRICT JUDGE.

U. S. DISTRICT COURT

qOU. DIST. ALA.

FILED AND ENTERED THIS THE

/47Y DAY OF DECEMBER,

19.7¢., MINUTE ENTRY

gar ALT

NO.

. »

es

ne ee et em of Ti Eh Fen a era nme me

r SATS TY

WILLIAM J. O'CONNOR, CLERK

mii

3 : [ol n Cll AA

BY 5% DEPUTY CLERK