City of New Haven, CN v. Marsh Appendix to Petition for Certiorari

Public Court Documents

July 5, 1988

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. City of New Haven, CN v. Marsh Appendix to Petition for Certiorari, 1988. 66cdb45e-bf9a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/34a2ecee-b6cb-44f7-981c-621d4daa4321/city-of-new-haven-cn-v-marsh-appendix-to-petition-for-certiorari. Accessed February 23, 2026.

Copied!

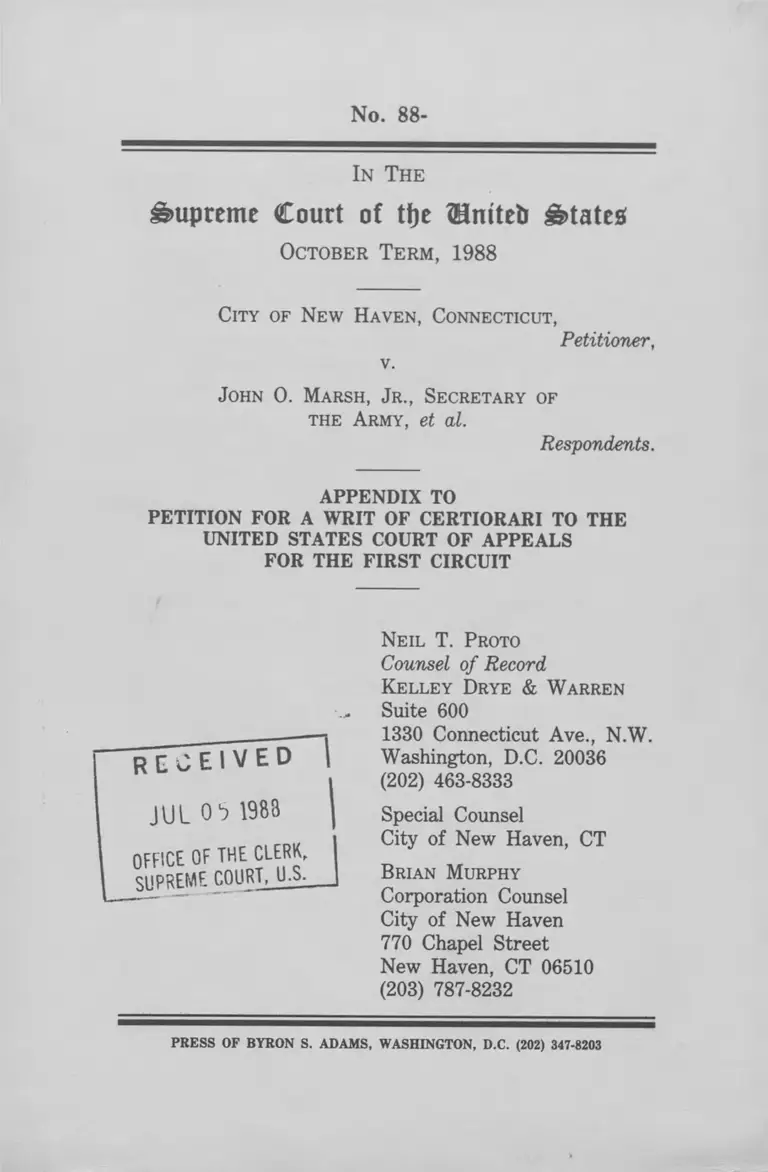

No. 88-

In The

Supreme Court of tfje Hmteti States

October Te r m, 1988

City of New Haven, Connecticut,

Petitioner,

v.

J ohn 0 . Marsh, J r., Secretary of

the Army, et al.

Respondents.

APPENDIX TO

PETITION FOR A WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE FIRST CIRCUIT

R E C E I V E D

jUl 0*5 1988 |

OFFICE OF THE CLERK.

SUPREME COURT, U.S._

Neil T. Proto

Counsel of Record

Kelley Drye & Warren

Suite 600

1330 Connecticut Ave., N.W.

Washington, D.C. 20036

(202) 463-8333

Special Counsel

City of New Haven, CT

Brian Murphy

Corporation Counsel

City of New Haven

770 Chapel Street

New Haven, CT 06510

(203) 787-8232

P R E SS OF BYRON S. ADAMS, WASHINGTON, D.C. (202) 347-8203

APPENDIX

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Page

APPENDIX A: Court of Appeals

Denial of Rehearing Order,

Dated April 7, 1988 .............la

APPENDIX B: Court of

Appeals Opinion,

Dated March 11, 1988 ........ 3a

APPENDIX C: Court of

Appeals Judgment,

Dated March 11, 1988 ........ 24a

APPENDIX D: District Court Memo

randum and Order, Dated

September 8, 1987............ 25a

APPENDIX E: District Court Memo

randum and Order, Dated

May 12, 1987 ................. 85a

APPENDIX F: Excerpts,

Record of Decision,

Dated November 15, 1984. . . . 93a

APPENDIX G: Letter from Divi

sion Engineer to Mall

Properties, Inc., Dated

August 20, 1985.............. 102a

APPENDIX H: Record of Decision,

Dated August 20, 1985........ 104a

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE FIRST CIRCUIT

No. 87-1827

MALL PROPERTIES, INC.,

Plaintiff, Appellee,

v.

JOHN 0. MARSH, JR., ETC., ET AL.,

Defendants, Appellees,

CITY OF NEW HAVEN,

Intervenor-Defendant, Appellant.

Before

CAMPBELL, Chief Judge. COFFIN,

BOWNES, BREYER, TORRUELLA

and SELYA, Circuit Judges.

ORDER OF COURT

Entered: April 7, 1988

The panel of judges that rendered

the decision in this case having sub

mitted by the City of New Haven and its

suggestion for the holding of a rehearing

en banc having been carefully considered

la-

by the judges of the court in regular

active service and a majority of said

judges not having voted to order that the

appeal be heard or reheard by the Court

en banc,

It is ordered that the petition for

rehearing and the suggestion for rehear

ing be both denied.

By the Court:

//s//

Clerk.

[cc: Messrs. Lawson, Proto, Cochran,

Richmond, Shelley, Robinson, Friedman, Tripp and Dewey]

2a-

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

For the First Circuit

No. 87-1827

MALL PROPERTIES, INC.,

Plaintiff, Appellee,

v .

JOHN 0. MARSH, JR., ETC., ET AL.,

Defendants, Appellees,

CITY OF NEW HAVEN,

Intervenor-Defendant-Appellant.

APPEAL FROM THE

UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

FOR THE DISTRICT OF MASSACHUSETTS

[Hon. Mark L. Wolf, U.S. District Judael

Before

Coffin, Bownes and Breyer,

Circuit Judges.

3a

Kathleen____P,____ Dewey, Appellate

Section, Land and Natural Resources

Division, Department of Justice, for

federal appellees* motion to dismiss.

Alice Richmond. Hemenwav & Barnes,

Daniel Riesel. and Sive. Paget & Riesel,

P.C., on memoranda in support of motion

to dismiss for appellee Mall Properties,

Inc.

Neil Proto. Kellev. Drve and Warren,

Frank B. Cochran. Peter B. Cooper.

Coooer. Whitnev. Cochran & Francois.

Edward F. Lawson, and Weston, Patrick,

Willard & Reddina on memoranda in

opposition to motion to dismiss for

appellant City of New Haven.

MARCH 11, 1988

4a

Per Curiam. The government has

filed a motion to dismiss, joined in by

appellee Mall Properties, Inc., contend

ing that a district court order remanding

to the Corps of Engineers for further

proceedings is not a final appealable

order and hence the present appeal should

be dismissed. Appellant City of New

Haven opposes the motion to dismiss. We

reject the City's argument that the mo

tion to dismiss was untimely. Jurisdic

tional defects are noticeable at any

time. We turn, then, to the background.

Plaintiff Mall Properties, Inc.,

applied to the Corps of Engineers for

permits to fill wetlands so that plain

tiff might build a 1.1 million square

foot, two story shopping mall in North

Haven, Connecticut. The Corps denied the

permit. Among the factors the Corps con

sidered in concluding the project was

5a

contrary to the public interest was,

first, the City of New Haven's opposition

to the mall on the ground that a North

Haven mall would adversely impact New

Haven's economic development and, second,

the Governor of Connecticut's statement

at a July 1985 meeting that building the

North Haven Mall was not worth the risk

to New Haven. The district court ~

concluded that the Corps had exceeded its

authority (1) by basing the permit denial

on socio-economic harms not proximately

related to changes in the physical en

vironment and (2) by not following its

regulations which required that Mall

1. Though plaintiff Mall Properties is

a New York corporation and the mall is

proposed to be built in Connecticut,

venue in Massachusetts of the present

action was premised on 28 U.S.C. §

1391(e)(1) as one of the federal defen

dants, the Divisional Engineer of the New

England Division of the Army Corps of

Engineers, resides in Massachusetts.

6a

Properties be provided notice of an op

portunity to rebut the objection made by

the Governor of Connecticut. According

ly, the court remanded the case to the

Corps for further proceedings consistent

with its opinion. The question, then, is

whether this remand order is now appeal-

able .

New Haven argues that the district

court entirely disposed of the matter

before it — Mall Properties' petition

for review — and granted Mall Properties

the relief requested — a remand to the

Corps. Hence, New Haven contends, the

judgment is a final one. We disagree.

Ultimately, Mall Properties wants the

proper permits themselves and, in the

event of a judicial challenge to the per

mit, a judgment adjudicating Mall's en

titlement to the permits. Indeed, orig

inally Mall's complaint asked the court

7a

to direct the Corps to issue Mall the

permits (though Mall subsequently acknow

ledged that a remand would be the proper

remedy were it to prevail). Thus, the

district court's remand order does not

grant Mall ultimately what Mall wants.

Rather, the court's order is but one in

terim step in the process towards Mall's

obtaining its ultimate goal. Consequent

ly, we do not view the remand order as

meeting the traditional definition of a

final judgment, that is, one which "ends

the litigation on the merits and leaves

nothing for the court to do but execute

the judgment." Catlin v. United States.

324 U.S. 229, 233 (1945). The litigation

has not ended. It simply has gone to

another forum and may well return again.

Cf. In re Abdallah. 778 F.2d 75 (1st Cir.

1985)(district court order remanding case

8a

to bankruptcy court for further proceed

ings not final appealable order), cert.

denied, 106 S. Ct. 1973 (1986); Giordano

v. Roudebush. 565 F.2d 1015 (8th Cir.

1977)(district court order ruling that

plaintiff was not entitled to a full

trial type procedure but remanding to

agency for further consideration of

plaintiff's arguments neither granted nor

denied the ultimate relief plaintiff

wanted — reinstatement and back pay —

and was not a final appealable order);

Transportation-Communication Division v .

St. Louis-San Francisco Rv. Co.. 419 F.2d

933, 935 (8th Ci r.) (district court order

which neither enforced nor denied en

forcement of Board's award, but rather

decided some issues and remanded for fur

ther proceedings, made no final determi

nation of the entire merits of the con

troversy and is not appealable), cert

9a

denied. 400 U.S. 818 (1970). The order

is not final in the usual sense.

This court and others have said that

generally orders remanding to an adminis

trative agency are not final, immediately

appealable orders. See, e.o.. Pauls v.

Secretary of Air Force. 457 F.2d 294,

297-298 (1st Cir. 1972)(order remanding

to Air Force Board for the Correction of

Military Records directing discovery and

detailed fact findings not appeal-

2able);- Memorial Hospital System v.

Heckler. 769 F.2d 1043 (5th Cir. 1985)

(hospital appeal from order remanding for

further proceedings relating to Medicare

2. New Haven seeks to distinguish Pauls

on the ground that there the district

court remanded but retained jurisdiction

to review the final determination of the

Secretary of the Air Force. The

retention of jurisdiction was not the

basis for our determination that the

remand order was not appealable.

10a

reimbursement dismissed); Howell v.

Schweiker, 699 F.2d 524 (11th Cir. 1983)

(claimant may not appeal from order re

manding to Secretary for further proceed

ings); Eluska v. Andrus. 587 F.2d 996,

999-1001 (9th Cir. 1978)(order remanding

to Board of Land Appeals so that plain

tiff may exhaust administrative remedies

not appealable even though once such

remedies are exhausted it may not be pos

sible to review exhaustion order) . See

also 15 C. Wright, A. Miller, E. Cooper,

Federal Practice and Procedure §§ 3914 at

pp. 551-553 (1976).

Exceptions have been recognized in

some cases, however, and appeals have

been allowed from orders remanding to an

administrative agency for further pro

ceedings. See, e.a.. United States v.

Alcon Laboratories. 636 F.2d 876, 884-885

(1st Cir.)(remand order putting in issue

11a

order in which agency enforcement action

should proceed appealable under Cohen

collateral order doctrine), cert, denied,

451 U.S. 1017 (1981); Gueorv v. Hampton,

510 F. 2d 1222 (D.C. Cir. 1975) (Chairman' s

appeal from order remanding to Civil

Service Commission allowed); Paluso v.

Mathews. 573 F.2d 4 (10th Cir. 1978)

(Secretary's appeal from order remanding

for further proceedings with respect to

coal miner's application for benefits);

Citizens to Preserve Overton Park v .

Brinegar, 494 F.2d 1212 (6th Cir. 1974)

(no discussion of appealability), cert

denied, 421 U.S. 991 (1975).

Trying to make order out of the case

law, the City of New Haven argues that

whereas remands for factual development

may not be appealable orders, under a

practical conception of finality, dis

trict court orders which determine an

12a

important legal issue, announce a new

standard, and impose a new legal standard

or procedural requirements upon the

agency in the remand proceeding should be

considered final and immediately appeal-

able. Indeed, citing a number of cases,

the City argues that that is in fact the

distinction the case law has drawn.

In particular New Haven relies heav

ily on Bender v. Clark. 744 F.2d 1424

(10th Cir. 1984). There, a crucial issue

was whether a particular tract of land

contained a known geologic structure

(KGS). If it did, petitioner's noncom

petitive oil and gas lease offer for the

land would have to be rejected and the

land could only be leased by competitive

bidding. The Interior Board of Land Ap

peals determined that the government had

made a prima facie case of the existence

of a KGS and that petitioner had failed

13a

to show by "clear and definite evidence"

that the government had erred. Petition

er sought judicial review. The district

court concluded the Board had imposed too

high a standard of proof on petitioner.

Rather than "clear and definite" evi

dence, petitioner need only prove govern

ment error by a preponderance of the evi

dence. Consequently, the district court

remanded to the Board for further pro

ceedings applying the correct burden of

proof. The government appealed. In

determining whether the remand order was

immediately appealable, the Tenth Circuit

stated that "[t]he critical inquiry is

whether the danger of injustice by delay

ing appellate review outweighs the incon

venience and costs of piecemeal review."

Id. at 1427. The court decided the mat

ter in favor of immediate appeal stating

two reasons. First was the fact that the

14a

standard of proof issue was a serious and

unsettled one. But second, "and perhaps

most important," the court said, was that

the government had no avenue for obtain

ing judicial review of its own adminis

trative decisions and thus well might be

foreclosed from appealing the district

court's burden of proof ruling at a later

stage of proceedings.

In contrast to Bender. in the pres

ent case the government has not appeal

ed. In other words, the government is

not challenging the district court's rul

ing (1) that the Corps of Engineers may

not deny permits on the basis of socio

economic harms unrelated to physical en

vironmental changes and (2) that the

Corps violated its regulation in not giv

ing Mall Properties an opportunity to

rebut the governor's opposition. Many of

the other cases on which the City of New

15a

Stone v . Heck-Haven relies, see, e.g. ,

ler. 722 F.2d 464, 467 (9th Cir. 1983)

(district court order ruling that Secre

tary could not apply grid but rather must

use VE to enumerate specific jobs avail

able and remanding for further proceed

ings is immediately appealable by govern

ment since, were the application of the

district court's legal standard to lead

to benefits being awarded on remand, the

Secretary would not be able to appeal);

Gueory v. Hampton, 510 F.2d 1222, 1225

(D.C. Cir. 1975)(unless review allowed

government probably never would be able

to test district court ruling); Gold v.

Weinberger, 473 F.2d 1376 (5th Cir. 1973)

(unless Secretary allowed to appeal re

mand order, Secretary will not obtain

review of district court .ruling that VE

required to interview claimant), are

similar to Bender in that an appeal from

16a

a remand order was allowed by the govern

ment or government agency unlikely there

after to be able to obtain review. In

deed, we think the crucial distinction in

these cases is not — as New Haven would

contend — simply the fact that the dis

trict court imposed a new or unsettled

legal standard on the agency, but rather

that unless review were accorded immedi

ately, the agency likely would not be

able to obtain review.

The City of New Haven argues, how

ever, that it is similarly situated to

the governmental agencies whose appeals

from remand orders were allowed for, the

City says, denying it review now is

tantamount to foreclosing any effective

review at all. That is because, the City

maintains, the district court decision

precluding the Corps from considering

socio-economic factors has removed from

17a

the Corps' consideration the economic

interests at the heart of the City's op

position to the permits and has effec

tively terminated the City's participa

tion. The City is wrong. The City has

not been foreclosed from participating in

the proceedings on remand. Presumably,

it can urge environmental reasons why the

permits should be denied. If, after re

mand, the permits are granted, the City

can seek judicial review and if the dis

trict court upholds the grant, the City

can appeal to this court and both argue

that the original permit denial based on

New Haven's socio-economic developmental

interests was proper and present any

other challenges arising from the remand

proceedings it may have. Thus, review of

the socio-economic issue the City now

wants to present, is not denied; it is

18a

asimply delayed. ^ For this reason, the

remand order is not appealable under the

Cohen collateral order doctrine as the

third requisite for collateral order

appealability — a right incapable of

vindication on appeal from final judgment

— see Boreri v. Fiat S.P.A. . 763 F.2d

17, 21 (1st Cir. 1985) — is not met.

3. The City's argument that the dis

trict court judgment may have res judi

cata affect is wrong. A prerequisite to

the application of res judicata prin

ciples is a final judgment, Restatement

(Second) Judgments § 13 (1980), but, as

we conclude here, tfre district court

judgment remanding to the agency is not a

final judgment. Nor does the City's

argument that on a petition for review

following remand the district court may

refuse to reconsider the socio-economic

issue persuade us otherwise. Under law

of the case principles that may indeed

happen. Nevertheless, the City will be

able to challenge on appeal the district

court's original (September 8, 1987)

decision.

19a

Moreover, contrary to the City's

argument, we think allowance of an imme

diate appeal would violate the efficiency

concerns behind the policy against piece

meal appeals. Were this court now to

order briefing on the socio-economic is

sue, decide that issue and affirm the

district court, the case would be re

manded and the Corps once again would

decide whether to issue the permit.

Likely another appeal would follow,

necessitating another round of briefs,

another familiarization with the record,

and another opinion. Our decision on. the

socio-economic issue might turn out to

have been superfluous were the Corps on

remand to deny the permits on independent

proper grounds. More efficient and

quicker, in the long run, would have been

to delay review and consider all issues

at one time. Alternatively, were review

20a

granted now and were we to conclude the

district court erred, an unnecessary

administrative proceeding could be

averted. - But this alone is insuffi

cient reason to permit review. As the

Third Circuit observed in Bachowski v.

Usery, 545 F.2d 363, 373 (3d Cir. 1976)

when dismissing an appeal from a district

court order remanding to the Secretary of

Labor for further proceedings, "the wis

dom of the final judgment rule lies in

its insistence that we focus on systemic,

4. However, according to the district

court opinion, Mall Properties had

several other arguments for vacating the

Corps' order which the district court

found unnecessary to address since it was

remanding on other grounds; hence,

further proceedings in the district court

on these issues followed by another

appeal might result even if we were not

to rule in New Haven's favor on both the

socio-economic issue and procedural issue

concerning failure to afford Mall

Properties an opportunity to rebut the

governor's opposition.

21a

as well as particularistic impacts." To

reach out to decide the merits of an in

terlocutory order just because reversal

of an erroneous interlocutory ruling

would expedite a particular litigants’

case would, in the long run, undermine

the final judgment rule and open the door

to piecemeal litigation and its concomi

tant delay, costs, and burdens. See also

15 C. Wright, A. Miller, E. Cooper,

Federal Practice and Procedure § 3914 at

pp. 552-553 (strong showing of unusual

reason for avoiding the burden of further

administrative proceedings should be re

quired before a remand order is treated

as final).

New Haven asks that if the remand

order is not a final appealable order we

construe New Haven's notice of appeal as

a petition for mandamus. We see no ex

traordinary circumstances warranting the

exercise of mandamus jurisdiction.

22a

The request for oral argument on the

motion to dismiss is denied and the ap

peal is dismissed for lack of jurisdic

tion.

Since this appeal has been dismissed

on jurisdictional grounds, the motion of

North Haven League of Women Voters and

Stop the Mall/Connecticut Citizen Action

Group to file an amicus brief is denied.

Appeal dismissed.

Adm. Office, U.S. Courts —

Blanchard Press, Inc., Boston, Mass.

23a

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE FIRST CIRCUIT

No. 87-1827

MALL PROPERTIES, INC.,

Plaintiff, Appellee,

v.

JOHN 0. MARSH, JR., ETC., ET AL.,

Defendants, Appellees,

CITY OF NEW HAVEN,

Intervenor-Defendant-Appellant.

JUDGMENT

Entered: March 11, 1988

This cause was submitted on briefs

on appeal from the United States District

Court for the District of Massachusetts.

Upon consideration whereof, It is

now here ordered, adjudged and decreed as

follows: The appeal is dismissed.

By the Court:

//s//

Clerk.

tec: Messrs. Dewey, Richmond and Proto]

24a

UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

DISTRICT OF MASSACHUSETTS

MALL PROPERTIES, INC.,

Plaintiff, )

)

)v ) C .A. No. 85-4038-W

JOHN V. MARSH

Defendant

)

)

)

MEMORANDUM AND ORDER

WOLF, D.J September 8, 1987

Mall Properties, Inc., a developer

of shopping malls, brought this action,

seeking an order vacating the denial by

the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers (the

"Corps") of an application for a permit

under Section 10 of the Rivers and Har

bors Act and Section 404 of the Clean

Water Act, 33 U.S.C. §§ 403 and 1344

(1982). The permit is required for the

development of a proposed mall on a site

in the Town of North Haven, Connecticut.

25a

The court finds that the Corps'

order denying the permit must be vacated

because its decision was not made in ac

cordance with law. Rather, the Corps

exceeded its authority (1) by basing its

denial of the permit on socio-economic

harms that are not proximately related to

changes in the physical environment and

(2) by not following its regulations

which required that Mall Properties be

provided notice and an opportunity to

attempt to reverse or rebut an objection

to the construction of the proposed mall

made by the Governor of Connecticut.

These errors reguire a remand of the case

to the Corps.

I. BACKGROUND

Mall Properties is an organization

which for many years has sought to devel

op a shopping mall in the Town of North

Haven, Connecticut. North Haven is a

26a

suburb about ten miles from New Haven,

Connecticut.

As the proposed development would

involve the filling of certain wetlands

and open waters, Mall Properties must

obtain a permit from the Corps pursuant

to Section 404 of the Clean Water Act, 33

U.S.C. § 1344 ("Section 404") and Section

10 of the Rivers and Harbor Act, 33

U.S.C. § 403 ("Section 10"). Although

"the Corps administers a dual permit sys

tem under two different statutes ... to

regulate dredge and fill activities,"

United States of America v. Cumberland

Farms, C.A. No. 86-1983 (1st Cir. Aug.

18, 1987), the procedures and standards

utilized by the Corps, and in dispute in

the instant case, are equally applicable

to both acts. See 33 C.F.R. § 320 (1986).

The City of New Haven has consis

tently opposed development of the mall.

27a

It claims that a North Haven mall will

jeopardize the fragile economy of New

Haven, which all levels of government

have long been seeking to revitalize.

New Haven has actively participated in

proceedings before the Corps and in this

litigation.-^

As required by law, 33 C.F.R. §

320.4(a), the Corps conducted a public

interest review in connection with decid

ing whether to issue Mall Properties the

requested permit. Acting for the Corps

in this matter was Colonel Carl B. Sciple.

l-̂ The court allowed New Haven to inter

vene as a defendant in this action under

F.R.Civ.P. 24. See Memorandum and Order,

May 12, 1986. Three environmental groups

— the Connecticut Fund for the Environ

ment, the Environmental Defense Fund, and

the Conservation Law Foundation — were

denied leave to intervene, but allowed to

inform the court of their views as amicus

curiae. Jcl. These groups may also pre

sent their arguments to the Corps in the

proceedings which must be conducted pur

suant to the remand of this case.

28a

On August 25, 1985, Colonel Sciple

denied Mall Properties' request for a

permit. In the Record of Decision

("ROD") providing the explanation for the

denial, Colonel Sciple concluded by sum

marizing the relative roles of various

factors in his decision. He wrote:

I have considered many factors

in my public interest review of

the applicant's proposal. Land

use is one of those factors,

and I recognize that the deci

sion of state and local govern

ment is conclusive as to that

factor. In the matter under

consideration, the views of the

state and the local government

about the proposed project are

different. While the land may

be used for a shopping mall

under North Haven's zoning reg

ulations, the Office of Policy

and Management, Comprehensive

Planning Division, of the State

of Connecticut has taken the

position that the development

of a shopping mall at North

Haven is inconsistent with the

state's conservation and devel

opment policies. But even

where state and local author

ities give zoning or other land

use approval, a person conduct

ing a public interest review

29a

must make a thorough objective

evaluation of an application in

full compliance with applicable

laws and regulations (See 49 FR

39478 and 39479).

Therefore, in my public inter

est review I considered factors

other than land use. Those

factors, where applicable, are

listed in 33 Code of Federal

Regulations Section 320.4(a),

namely, conservation, econom

ics, aesthetics, general en

vironmental concerns, wetlands,

cultural values, flood hazards,

flood plain values, navigation,

shore erosion and accretion,

recreation, water supply and

conservation, water quality,

energy needs, safety, flood and

fiber production, mineral

needs, considerations of prop

erty ownership, and, in gener

al, the needs and welfare of

the people.

The resubmission-2/ presented

on-site wetland mitigation to

compensate for the most impor

tant wetlands lost. Portions

of parking areas would be

raised, and additional flood

— proposed Final Order denying the

permit was issued on November 24, 1984.

Mall Properties subsequently submitted

proposed modifications which the Corps agreed to consider.

30a

storage was proposed to lessen

previous flooding impacts.

Socio-economic impacts to New

Haven were proposed to be miti

gated by the opening of three

anchor stores in 1987, delaying

until 1991 the opening of the

fourth anchor store, contribut

ing $100,000 in job training

funds to the city of New Haven,

and petitioning the transit

authority to provide bus serv

ice for potential mall employ

ees of New Haven.

[The Colonel found that] al

though there is still a net

loss in wetland resources, the

proposed on-site wetland crea

tion, if successfully devel

oped, would substantially com

pensate for lost value of the

most important seven acres of

wood swamp and freshwater

marsh. Flooding impacts, al

though lessened further and not

major, are nonetheless trouble

some to me when viewed against

the policies of the flood plain

executive order and one of the

Corps basic missions of provid

ing flood protection.

Still weighing most heavily,

however, is mv concern for the

socio-economic impacts this

project would have on the city

of New Haven. I had encouraged

the applicant to meet with the

Mayor of New Haven with the

31a

hope that they would find com

mon ground. Even though they

met, it was to no avail. While

the applicant has made propos

als to mitigate socio-economic

impacts, including the most

recent one described above, he

has not, in my view, gone far

enough.

The Hartford regional office US

Department of Housing and Urban

Development has expressed con

cerns about the mall from a

national and Federal perspec

tive. (Recently there has been

an indication that these views

might be tempered at its Wash

ington level.) Local elected

leaders have differing views on

the Mall. The First Selectman

of North Haven favors the Mall,

the Mayor of New Haven is op

posed to the Mall. At the

State level, the Connecticut

Office of Policy and Manage

ment, Comprehensive Planning

Division has stated that the

Mall is contrary to state urban

policies. Also, during mv July

J-3Q3Governor

c i r m w i t n

O ’Neill. - . c o n

he

necucut s

indicatedthat he felt_it was not worththe risk to New Haven of build-ing the North Haven Mall. I

have therefore concluded, that

this project is contrary to the

public interest and the permit is denied.

ROD pages 45 to 47. (Emphasis added)

32a

Mall Properties subsequently filed

this action requesting that the order

denying the permit be vacated. In the

course of this case Mall Properties with

drew its initial request for injunctive

relief in the form of an order requiring

issuance of the permit. Thus, it is not

disputed that remand to the Corps is the

sole appropriate remedy if Mall Proper

ties prevails in this action.

Mall Properties requests that the

order denying its permit be vacated pri

marily on the ground that the Corps im

properly relief on the effect that the

North Haven mall would have on the econo

my of New Haven in reaching its deci

sion. Mall Properties also contends that

the Corps acted illegally in receiving

and relying upon an objection to the mall

by the Governor of Connecticut which it

33a

was not afforded an opportunity to ad

dress.^ The defendants assert that

Mall Properties' claims are incorrect as

matters of law.

The parties filed cross-motions for

summary judgment. They agree that the

material facts are not in dispute. A

hearing was held on the cross-motions.

Thus, the case is ripe to be decided.

II. THE STANDARD OF REVIEW

The standard of review to be applied

in this case is established by the Ad

ministrative Procedure Act, 5 U.S.C. §

706(2)(A)(D)(1982) . "The applicable

scope of review calls for determination

3/Mall Properties' complaint also al

leges several other grounds for vacating

the Corps' order which, because the case

is being remanded, it is not necessary to address.

34a

of whether the Corps' action was 'arbi

trary, capricious, an abuse of discre

tion, or otherwise not in accordance with

law’ or 'without observance of procedure

required by law.'" Houah v. Marsh. 557

F. Supp. 74, 79 (D.Mass. 1982)(quoting

from 5 U.S.C. § 706(2) (A) (D)) . See gen

erally Citizens to Preserve Overton Park

v. Volpe, 401 U.S. 402 (1971).

III. CONCLUSIONS OF LAW

A. The Corps' Reliance On The

Socio-Economic Impacts On New

Haven Was Not In Accordance With

Section 404, Section 10, or The

Corps' Public Interest Review

Regulations. ________________

As the ROD states, the factor

"weighing most heavily" in the Corps’

decision to deny Mall Properties a permit

was the "concern for the socio-economic

impacts this project would have on the

City of New Haven." ROD at 46. The

record reveals that these impacts would

35a

not result from any effect the mall would

have on the physical environment general

ly or wetlands particularly. Rather, it

is the economic competition for New Haven

which would result from the mere exis

tence of a mall anywhere in North Haven

which was the most significant factor in

the Corps’ decision to deny the permit.

The Corps did find that there was no al

ternative site for the mall in North

Haven. This, however, does not alter the

fact that there is in this case no proxi

mate causal relationship between the im

pact of the proposed development on the

natural environment and the economic harm

to New Haven which the Corps deemed most

significant in denying the permit.

Mall Properties contends that while

certain economic factors may properly be

considered by the Corps in deciding

whether to grant a permit, the Corps has

36a

not been empowered generally to regulate

economic competition between communities

and to make political decisions as to

which community's economic interests

ought to be preferred.

The defendants contend that the

Corps has the unqualified right and re

sponsibility to consider economics in

deciding whether to issue a permit. They

note that the relevant Corps regulations

state that the Corps review has "evolved

from one that protects navigation only to

one that considers the full public inter

est ---" 33 C.F.R. § 320.1(a). See

generally. Power, The Fox in the Chicken

£q p p :__The Regulatory Program of the U.S.

Army Corps of Engineers. 63 Va. L. Rev.

503, 526-29 (1977)(describing evolution

of Corps jurisdiction from the manageable

job "of determining whether proposed

structure impedes maritime traffic to

37a

public interest balancing."); Rodgers,

Environmental Law Air and Water 205

(1986)("Here is the corps famed 'public

interest' review that reads like a parody

of standardless administrative choice.");

1902 Atlantic Ltd. v. Hudson. 574 F.

Supp. 1381, 1398 n. 16 (E.D.Va. 1983).

As explained below, consideration of

the purposes of Section 404 and Section

10, the relevant provisions of those

laws, the "public interest" review regu

lations of the Corps, and the pertinent

case law persuades the court that the

Corps' action in this case was not in

accordance with law. More specifically,

the court concludes that in deciding

whether to grant a permit the Corps may

consider economic effects which are prox-

imately related to changes in the physi

cal environment. The Corps may not, how

ever, properly consider and give signifi

cant weight to economic effects unrelated

38a

to the impact which a proposed project

will have on the environment. Thus, the

Corps exceeded its authority in this case.

Section 404 (33 U.S.C. § 1344)states:

(a) The Secretary [of the

Army] may issue permits, after

notice and opportunity for pub

lic hearings for the discharge

of dredged or fill material

into the navigable waters at

specified sites.

* * *

(b) Subject to subsection (c)

of this section, each disposal

site shall be specified for

each such permit by the Secre

tary (1) through the applica

tion of guidelines ... which

. . . shall be based upon crite

ria comparable to the criteria

applicable to the territorial

seas, the contiguous zone, and

the ocean under section 1343(c)

of this title, and (2) in any

case where such guidelines un

der clause (1) alone would pro

hibit the specification of a

site, through the application

additionally of the economic

impact of the site on naviga

tion and anchorage.

39a

The Secretary's authority to act under

this provision has been delegated to the

Corps. 33 C.F.R. § 320.2(f).

Section 10 of the Rivers and Harbors

Act of 1899, 33 U.S.C. § 403 states:

[I]t shall not be lawful to

excavate or fill, or in any

manner to alter or modify the

course, location, condition, or

capacity of ... any navigable

water of the United States,

unless the work has been recom

mended by the Chief of Engi

neers and authorized by the

Secretary of the Army prior to

beginning the same.

The Secretary's authority under this pro

vision has also been delegated to the

Corps. See 33 C.F.R. § 322.5.

In making its economic analysis in

this case, the Corps relied on the public

interest review regulation expressly ap

plicable to both Section 404 and Section

10. That regulation, 33 C.F.R. . §

320.4(a), provides that in deciding

whether to issue a permit the Corps must

40a

conduct a public interest review balanc

ing the

benefits which reasonably may

be expected to accrue from the

proposal ... against its rea

sonably foreseeable detri

ments. 3/ ... Among [the fac

tors to be considered] are

conservation, economics, aes

thetics, general environmental

concerns, wetlands, cultural

values, fish and wildlife

values, flood hazards, flood-

plain values, land use, naviga

tion, shore erosion and accre

tion, recreation, water supply

and conservation, water qual

ity, energy needs, safety, food

and fiber production, mineral

needs, considerations of prop

erty ownership, and in general,

the needs and welfare of the people.

33 C.F.R. § 320.4(a).

The scope of the economic analysis

to be conducted by the Corps is not di

rectly addressed in the regulations.

4/These provisions explicitly apply to

both the Clean Water Act and the Rivers

and Harbors Act.

41a

Rather, although "economics has been in

cluded in the Corps’ list of public in

terest factors since 1970 .... there has

never been a specific policy on economics

in the regulations." 51 Fed. Reg. 41207

(1986) .

Therefore, the court in this case is

called upon to discern the scope of the

authority to consider economic factors

which has been delegated to, and exer

cised by, the Corps. It is axiomatic

that this decision must take into account

the legislative intent reflected by the

stated purposes and policies of the rele-

5/vant statutes. More specifically, as

^/As Justice Felix Frankfurter said:

Legislation has an aim; it seeks

to obviate some mischief, to

supply an inadequacy, to effect

a change of policy, to formulate

a plan of government. That aim,

FOOTNOTE CONTINUED

42a

the Supreme Court has stated in ad

dressing the effects which may be proper

ly considered in deciding whether an En

vironmental Impact Statement ("EIS") is

required under the National Environmental

Policy Act ("NEPA"), 42 U.S.C. § 4321, et

seq., courts must in cases such as this

consider the underlying policies of the

relevant statute in deciding whether an

actor should be held responsible under

that statute for certain effects of his

actions. Metropolitan Edison Co. v.

People Against Nuclear Energy et al.. 460

FOOTNOTE 5/ CONTINUED:

that policy is not drawn, like

nitrogen, out of the air; it is

evinced in the language of the

statute, as read in the light of

other external manifestations of

purpose. That is what the judge

must seek and effectuate ....

F. Frankfurter, "The Reading of

Statutes," in Of Law and Men 60 (1956).

43a

U.S. 766, 774 n. 7 (1983)("In the context

of both tort law and NEPA, courts must

look to the underlying policies or legis

lative intent in order to draw a manage

able line between those causal changes

that may make an actor responsible for an

effect and those that do not.").

"Section 404 of the Clean Water Act

was enacted 'to restore and maintain the

chemical, physical, and biological integ

rity of the Nation's waters.' 33 U.S.C.

§ 1251(a)(1976)(section entitled 'Con

gressional declaration of goals and pol

icy’)." Buttrev v. United States. 690

F .2d 1170, 1180 (5th Cir. 1982), cert.

denied. 461 U.S. 927 (1983). The plain

statement of legislative purpose con

tained in § 1251(a) is echoed in the

legislative history which indicates that

Section 404 was enacted "to protect the

guality of water and to protect critical

44a

wetlands 3 Legislative History of

the Clean Water Act of 1977, 95th Con

gress 2d Sess. at 532 (1978). Thus, the

purpose of Section 404 suggests that the

scope of economic inquiry which the Corps

has been authorized to conduct is con

fined to consideration of effects related

to alterations in the physical environ

ment .

The pertinent provisions of the

Clean Waters Act and the related regula

tions reinforce the view that Section 404

only authorizes the Corps to weigh eco

nomic effects related to changes in the

physical environment. The statutory pro

vision concerning permits for dredged or

fill material under which the Corps was

acting in this case is 33 U.S.C. § 1344.

Section 1344(b)(1) provides that Corps'

permit decisions must be governed by

guidelines based upon "criteria compara

ble to the criteria applicable to the

45a

territorial seas, the contiguous zone,

and the ocean under [33 U.S.C. § 1343(c)]

The regulations developed to im-

plement § 1343(c) indicate that the

Corps, in implementing its authority

under § 1344(b), should consider "the

nature and extent of present and poten

tial recreational and commercial use of

areas which might be affected by the

proposed dumping," and the "presence in

the material of any constituents which

might significantly affect living marine

resources of recreational or commercial

value." 40 C.F.R. § 227.18(a) and (h) .

The example provided by the regulations

of what should be considered is the "re

duction in use days of recreational

areas, or dollars lost in commercial

fishery profits or the profitability of

other commercial enterprises." 40 C.F.R.

46a

§ 227.19. Thus, § 1344(b)(1), as imple

mented by the relevant regulations, indi

cates that the proper scope of the Corps'

public interest inquiry is limited to the

effects of impacts on the physical envi

ronment, such as the commercial or recre

ational value of areas directly affected

by a change in the environment.

Section 1344(b)(2) also illuminates

the proper focus of the Corps' economic

inquiry. Section 1344(b)(2) provides

that the Corps may issue a permit "in any

case where [its] guidelines under §

1344(b)(1) alone would prohibit the

[granting of a permit], through the ap

plication additionally of the economic

impact of the site on navigation and

anchorage." This provision has been in

terpreted "as justifying the Corps' ap

proval of discharges at a site if envi

ronmentally preferable alternatives are

47a

prohibitively expensive or pose a serious

impediment to navigation." Rodgers, En

vironmental Law 406 (1977).

Section 1344(b)(2) has two pertinent

implications. First, § 1344(b)(2) does

not authorize denial of permits because

of economic harms; it only authorizes

issuance of permits because of economic

benefits that override environmental

harms. Rogers, supra at 202. Second,

and perhaps more importantly, the terms

of § 1344(b)(2) again indicate that the

relevant economic considerations are

those directly linked to the physical

environment, such as navigation and

anchorage.

The statutory language, legislative

history, and regulations concerning Sec

tion 10 of the Rivers and Harbors Act

reinforce the view reached by the court

in analyzing Section 404. Indeed, as

48a

Section 10 has evolved, it incorporates

the public review standards applicable to

Section 404, including the same limited

authority to consider certain economic

factors.

Section 10 does not expressly pro

vide for a public interest review or list

"economics" as a permissible criterion.

Section 10 of the Rivers and Harbors Act

of 1899 indicates that it was enacted to

protect the federal government's interest

in regulating the navigability of the

country's waterways. See e . a. United

States v. Logan & Craig Charter Service.

Inc., 676 F.2d 1216 (8th Cir. 1982). The

major concern of the legislation was ob

structions in navigable waters that would

interfere with interstate commerce on the

waterways. California v. Sierra Club.

451 U.S. 287 (1981). Thus, the economic

effects initially addressed by the

49a

statute are those which relate directly

to changes in the physical environment.

The subsequent evolution of Section

10 does not suggest an intention to

authorize consideration of economic fac

tors with a more attenuated relationship

to changes in the physical environment.

In the late 1960s, increased concern

about protecting the natural environment

led to an expansion by regulation in the

Corps' review under Section 10. Deltona

Cprp,__vJ__United States. 657 F.2d 1184,

1187 (Ct.Cl. 1981), cert. denied. 455

U.S. 1017 (1982); Power, supra. at 510.

In 1968, the Corps revised its regula

tions to include "public interest re

view." Deltona. 657 F.2d at 1187.

Public interest review included consider

ation of fish and wildlife, conservation,

pollution, aesthetics, ecology, and the

general public interest. I£. The March

50a

17, 1970 report of the House Committee on

Government Operations explained this ex

pansion :

The [Corps] which is charged by

Congress with the duty to pro

tect the nation’s navigable

waters, should, when consider

ing whether to approve applica

tions for landfills, dredging

and other work in navigable

waters, increase its considera

tion of the effects which the

proposed work will have, not

only on navigation, but also on

conservation of natural re

sources, fish and wildlife, air

and water quality, aesthetics,

scenic view, historic sites,

ecology, and other public in

terest aspects of the waterway.

H. R. Rep. No. 917, 91st Cong., 2d Sess.

at 5 (1970).

This report indicates that although

the interests to be considered under Sec

tion 10 are no longer limited to naviga

tion, they are all directly related to

impacts on the affected waterway.

In 1974, in order to "incorporate

the requirements of new federal legisla

tion" including Section 404, Deltona. 657

51a

F.2d at 1187, the Corps' responsibility

to conduct a public interest review under

Section 10, among other provisions, was

expanded to include "economics; historic

values; flood damage prevention; land use

classification; recreation; water supply

and water quality." Id. See also Jent-

aen__v_.__United States. 657 F.2d 1210,

1211-12 (CtCl. 1981)(sic), cert. denied.

455 U.S. 1017 (1982). Thus, since 1974,

the Corps' public interest review under

Both Section 10 and Section 404 have been

governed by the same regulation which is

now 33 C.F.R. § 320.4. As described

earlier, analysis of Section 404 indi

cates that the scope of the economic in

quiry under 33 C.F.R. § 320.4 is limited

to effects proximately caused by changes

in the physical evironment.(sic) The

foregoing analysis of Section 10 suggests

the same conclusion.

52a

The court’s conclusion that in de

ciding whether to issue a permit the

Corps may not properly consider economic

factors unrelated to impacts on the

physical environment is consistent with

the rulings and dicta in the few reported

cases addressing the economic component

of the Corps’ public interest review.

The case most directly on point is the

Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit's

decision in Buttrev. 690 F.2d 1170. In

Buttrev a developer of residential homes

was denied a dredge and fill permit under

Section 404 to channelize a half-mile

stream in Louisiana. The plaintiff

argued that the Corps should have con

sidered the public benefit that would

have flowed from about three million dol

lars in jobs to build the houses. The

Court of Appeals, however, found that

53a

"this is not the kind of 'economic' bene

fit the Corps' public interest review is

supposed to consider." Id., at 1180.

Although contrary to defendants'

contentions, the relevant dicta in Houah

v. Marsh. 557 F. Supp. 74 (D.Mass. 1982)

is compatible with the decision in But-

trey. Hough involved the Corps' issuance

of a permit to build two houses and a

tennis court on wetlands adjacent to

Edgartown Harbor on Martha's Vineyard.

The court found that the proposed con

struction would obscure, but not elimi

nate, the view of the nearby Edgartown

lighthouse, an attraction on sightseeing

bus routes. Id. at 86 and 87. After

deciding a remand was necessary because

the developer had not demonstrated the

absence of practicable alternatives, the

court addressed the question of econom

ics. It stated:

54a

To complete the discussion of

the Clean Water Act, the court

notes ... additional factors

that the Corps failed to ad

dress properly in connection

with the public interest review

mandated by 33 C.F.R. §

320.4(a) .... With respect to

[economics] ... the Corps did

mention the positive antici

pated impact of the proposal on

jobs and municipal taxes but it

sidestepped any consideration

of adverse economic effects —

particularly . . . the "elimina

tion of an attraction (the

Edgartown lighthouse) on the

itinerary of sightseeing buses."

Id. at 86.

Thus, in Hough the court noted that

construction on the particular property

which implicated the Corps' jurisdiction

would alter the physical environment,

obstruct a scenic view and, as a result,

have a cognizable economic effect on

sightseeing bus operators. In contrast,

in the present case the economic effects

which the Corps deemed significant re

sulted from the mere existence of a mall

55a

anywhere in North Haven. These effects

did not derive from the potential impact

of development on the physical environ

ment which triggered the Corps* public

interest review. Thus, Houah is factual

ly distinguishable from the present

case. The discussion of economic harms

in Hough is, however, also compatible

with the decision in Buttrev and this

court's conclusion that only socio

economic harms proximately related to

changes in the physical environment may

be properly considered by the Corps in

deciding whether to issue a permit.

This court's conclusion is rein

forced by the reasoning and results of

analogous cases involving NEPA. See

Metropolitan Edison. 460 U.S. at 774;

Sierra Club v. Marsh. 769 F.2d 868 (1st

Cir. 1985).

In Metropolitan Edison the Supreme

56a

Court addressed the question whether the

Nuclear Regulatory Commission complied

with NEPA when it did not consider the

potential psychological health effects

caused by activating a nuclear reactor at

Three Mile Island. Although the case

involved NEPA rather than Section 404,

and the harm addressed was psychological

rather than economic, the Supreme Court's

reasoning and result is persuasive in the

present case.

In Metropolitan Edison the Supreme

Court explained by way of background that:

All the parties agree that ef

fects on human health can be

cognizable under NEPA, and that

human health may include psy

chological health. The Court

of Appeals thought these propo

sitions were enough to complete

a syllogism that disposes of

the case: NEPA requires agen

cies to consider effects on

health. An effect on psycho

logical health is an effect on

health. Therefore, NEPA re

quires agencies to consider the

57a

effects on psychological health

asserted by [Metropolitan Edison].

Metropolitan Edison. 460 U.S. at 771.

Then the Supreme Court wrote in reversing

the Court of Appeals: "Although these

arguments are appealing at first glance,

we believe they skip over an essential

first step in the analysis. They do not

consider the closeness of the relation

ship between the change in the environ

ment and the 'effect' at issue." Id.. at

772.

In explaining its decision the

Supreme Court emphasized that NEPA was

"designed to promote human welfare by

alerting governmental actors to the ef

fect of their proposed action on the

physical environment." Id.. Thus, the

Court found "[t]o determine whether

[NEPA] requires consideration of a par

ticular effect, we must look at the rela

tionship between that effect and the

58a

change in the physical environment caused

by the ... federal action." I£. at 773.

The Supreme Court indicated, however,

that not even all "effects that are

'caused by’ a change in the physical en

vironment in the sense of 'but for' cau

sation [need be considered] . . . because

the causal chain [may be] too attenu

ated." Rather, the Court found that NEPA

"included a requirement of a reasonably

close causal relationship between a

change in the physical environment and

the effect at issue." I£. at 774.-X

If not every k

effect resulting from a

change in the physical environment is

^The Corps' public interest regula

tions themselves contain language famil

iar to proximate cause analysis. 33

C.F.R. § 320.4(a)(1) states "the benefits

which reasonably may be expected to ac

crue from the proposal must be balanced

against its reasonably foreseeable detriments . "

59a

cognizable under NEPA, Metropolitan

Edison makes it evident that effects un

related to changes in the physical envi

ronment may not be considered under NEPA.

The present case is analogous to

Metropolitan Edison. As discussed

earlier, Section 404 and Section 10 are,

like NEPA, concerned with the physical

environment. When there is a reasonably

close causal relationship between a

change in the physical environment and

economic factors, the Corps may consider

those factors in its public interest re

view. Metropolitan Edison, however, in

dicates that the Corps may not properly

consider and give significant weight to

other economic factors in deciding

whether to issue a permit pursuant to

Section 404 or Section 10.

Similarly, once again contrary to

defendants' contentions, the Court of

60a

Appeals for the First Circuit decision in

Sierra Club v. Marsh. 769 F.2d 868 (1st

Cir. 1985), is also compatible with the

conclusion that economic factors are cog

nizable by the Corps only if they are

adequately related to impacts on the

physical environment.

Sierra Club involved the question

whether a cargo port and a causeway that

Main planned to build at Sears Island

would "significantly affect the environ

ment" and, therefore, under NEPA, require

an EIS. Id., at 870. The First Circuit

found a "serious omission" in the Corps'

decision not to require an WIS, namely

the "failure to consider adequately the

fact that building a port and causeway

may lead to the further industrial devel

opment of Sears Island, and that further

development will significantly affect the

61a

environment." I£. at 877 (emphasis add

ed) . As the Court of Appeals later elab

orated, the Corps had before it evidence

that industrial development of the island

would lead to "2,750 new jobs in a town

with a population of under 2,500 ... in

creased traffic ... additional lost scal

lop beds and clam flats, more soil

erosion and aesthetic harm, a need for

additional waste disposal and water sup

ply, an added threat to water quality

...." Id., at 880. Thus, in Sierra Club

the evidence indicated that construction

causing a change in the environment would

cause industrial development which would

further impact the environment in signi

ficant respects. It was not an economic

impact alone — but rather its relation

ship to the environment — which the

Corps was directed to consider.

Thus Sierra Club, like Metropolitan

62a

Edison, suggests that there must be a

reasonably close link between economic

factors and the physical environment for

the Corps to be legitimately concerned

about those economic factors in perform

ing its function under NEPA. Once again,

a comparable conclusion is required when

the Corps is operating under Section 404

or Section 10.

As described previously, the pur

poses and policies of Section 404 and

Section 10, the relevant provisions of

the statutes and regulations, and the

case law all indicate that the Corps may

not rely upon economic factors which are

not proximately related to changes in the

physical environment in denying a dredge

or fill permit. Therefore, because the

Corps gave significant weight to economic

factors not related to changes in the

physical environment in this case, its

63a

decision was not in accordance with Sec

tion 404 or Section 10.

B. The Corp's (sic) Action is Not

Authorized bv NEPA.______________

The defendants contend that even if

Section 404 or Section 10 does not

authorize the Corps to give significant

weight to the economic effect which a

North Haven mall would have on New Haven

in the context of this case, the NEPA

statute itself provides the necessary-

authority. This contention, however, is

incorrect.

Defendants' claim concerning NEPA

relies primarily on two arguments.

First, defendants rely on § 105 of NEPA,

42 U.S.C. § 4335 which states that "the

policies and goals set forth in this Act

are supplementary to those set forth in

existing authorizations of Federal Agen

cies." See also Rodgers, Environmental

64a

Law Air and Water 204 (it is "clear that

the Corps' Section 10 authority was sup

plemented in some uncertain way by

[NEPA]."). NEPA, however, "does not ex

pand the jurisdiction of an agency beyond

that set forth in its organic statute ...

and the Supreme Court has characterized

'its mandate to the agencies [as] essen

tially procedural.'" Cape May Greene v.

Warren, 698 F.2d 179, 188 (3d Cir. 1983)

(quoting Vermont Yankee Nuclear P o w e r

CQFP.— v._Natural Resources Defense Coun-

fiil, 435 U.S. 519, 558 (1978)); see also.

01mstead Citizens for a Better Community

v. United States. 793 F.2d 201, 304 (8th

Cir. 1986)("[NEPA], while embodying sub

stantive goals for the preservation of

our physical environment, imposes basic

ally procedural obligations in pursuit of

these goals.") .

In any event, it is not necessary to

65a

decide whether, or to what extent, NEPA

enlarges the economic inquiry permitted

the Corps because NEPA clearly does not

authorize the reliance on the socio

economic impacts given significant weight

by the Corps in this case. Metropolitan

Edison was a NEPA case. As described

earlier, it construed NEPA to authorize

consideration only of harms proximately

related to a change in the physical en

vironment. That requirement is not met

in this case.

The Supreme Court's decision in

Metropolitan Edison also substantially

disposes of defendants' second argument

regarding the Corps' authority under

NEPA. Defendants cite a series of pre-

Metropolitan Edison NEPA cases which

stated that: "When an action will have a

primary impact on the natural environ

ment, secondary socio-economic effects

66a

may also be considered." Image of Gr.

San_Antonio. Texas v. Brown. 570 F.2d

517, 522 (5th Cir. 1978). See also

Breckenridge v. Rumsfield. 537 F.2d 864,

866 (10th Cir. 1976); cert, denied. 429

U.S. 1061 (1977); Hanly v. Mitchell. 460

F. 2d 640 (2d Cir. 1972), cert, denied.

409 U.S. 990 (1972); Como-Falcon Coali-

t ion , Inc. v. Department _Labor. 609

F.2d 342, 346 (8th Cir. 1979) cert.

denied. 446 U.S. 936 (1980); Nucleus of

Chicago Homeowner's Ass’n v. Lvnn. 524

F . 2d 225 (7th Cir.. 1975) cert. denied.

424 U.S. 936 (1980).

In Olmstead the Court of Appeals for

the Eighth Circuit addressed the con

tinued vitality of such cases. 793 F.2d

at 206. Olmstead involved the proposed

conversion of a mental hospital campus

into a federal prison. As in this case,

the proposed action would not have had

67a

significant impacts on the physical en

vironment. Id. at 206. In addressing

the "oft — quoted passage," stating that

socio-economic effects are to be con

sidered when the "action at issue has a

primary impact on the natural environ

ment," Id.., the Eighth Circuit stated:

[I]t is unlikely that such a

distinction survives the recent

Supreme Court holding in Metro

politan Edison. That decision

... was based on congressional

intent, and there is no sugges

tion that Congress contemplated

that the process it designed to

make agencies aware of the con

sequences of their actions with

regard to the physical environ

ment would be converted into a

process for airing general pol

icy objections anytime the

physical environment was impli

cated. Such a rule would di

vert agency resources away from

the primary statutory goal of

protecting the physical envi

ronment and natural resources,

just as in Metropolitan Edi

son. See 460 U.S. at 776, 103

S.Ct. at 1562. Furthermore,

courts even before Metropolitan

Edison had commented on the

anomaly of requiring that an

agency consider impacts not

68a

sufficient to trigger prepara

tion of an ecological statement

just because such a statement

was required for other unre

lated reasons. E.q.. Citizens

Committee Against Interstate

Route 675 v. Lewis. 542 F.Supp.

496, 534 (S.D.Ohio 1982).

Olmstead Citizens' concerns

with crime and property values

would exist regardless of any

physical changes to the former

mental hospital campus.

id. The Eighth Circuit’s reasoning is

equally compelling in the instant case.

In addition, even if it were per

missible for the Corps to consider unre

lated socio-economic effects if the pro

posed project has a primary impact on the

the natural environment, such considera

tion would not be appropriate in this

case. Here, as in Olmstead. the primary

impacts which concerned the Corps did not

involve the physical environment.

Rather, the Corps candidly stated that

socio-economic effects "weighed most

heavily" in its decision. ROD at 46.

69a

Thus, the cases on which defendants sub

stantially rely are inapposite even if

their persuasive value is not, as the

court finds, eliminated by Metropolitan

Edison.

Finally, the court has particularly

considered two cases upon which the de

fendants rely heavily. The first is

Hanlv in which the Second Circuit ex

plained that the:

National Environmental Policy

Act contains no exhaustive list

of so-called "environmental

considerations," but without

question its aims extend beyond

sewage and garbage and even

beyond water and air pollution

.... The act must be construed

to include protection of the

quality of life for city resi

dents .

460 F.2d at 647. In Hanlv. the Court of

Appeals found that placement of a jail in

a narrow urban area directly across the

street from two large apartment houses

presented problems of noise, fears of

70a

disturbances, traffic problems and other

"environmental considerations" within

NEPA. The court then found the General

Services Administration did not give ade

quate consideration to the factors relat

ing to the quality of city life.

Although Metropolitan Edison appar

ently qualifies at least parts of the

Hanly ruling, particularly the reliance

on fears of disturbances, the close prox

imity of the jail to the apartment

houses, and the court's focus on noise,

traffic problems and other "environmental

considerations" suggests that many of the

harms in Hanlv were proximately related

to the change in the physical environment

which would be caused by the construction

of the jail. Thus, Hanlv is factually

distinguishable from the instant case.

The other case heavily relied on by

the defendants is Dalsis v. Hills. 424 F.

71a

Supp. 784 (W.D.N.Y. 1976). Dalsis in

volved the construction of an enclosed

shopping mall in Olean, New York. The

U.S. Department of Housing and Urban

Development ("HUD") had funded demolition

of substandard buildings on the proposed

site and approved the mall.

Although the court found there was

no need for an EIS, in reaching that con

clusion the court engaged in an environ

mental analysis that involved socio

economic considerations similar to those

presented in the instant case. The court

indicated that the harm to the environ

ment would be "that excessive competition

from retail stores in the mall would lead

to blight and decay" in the form of

boarded up stores driven out of busi

ness. i£. at 792. It appears that this

harm might be too attenuated to be cog

nizable under Metropolitan Edison.

72a

Nevertheless, there is another major dif

ference between Dalsis and the instant

case: the agency involved in Dalsis was

HUD, while the agency involved in the

instant case is the Corps. As the plain

tiff states, "HUD's consideration of

downtown business interests was necessi

tated by the dictates of its implementing

statute; NEPA alone did not require such

a result." Memorandum of Plaintiffs in

Opposition to Defendant's Motion for Sum

mary Judgment at 30. The court finds

this distinction persuasive, although it

recognizes the distinction is implicit

rather than explicit in the district

court's opinion in Dalsis. Drawing this

distinction is consistent with the

Supreme Court's conclusion in Metropoli

tan Edison that "the scope of the agen

cy's inquiries must remain manageable if

73a

NEPA’s goal of *insur[ing] a fully in

formed and well-considered decision* is

to be accomplished." 460 U.S. at 776.

C. Conclusion Concerning Economic

Considerations___________________

As set forth previously, the most

significant factor in the Corps' decision

to deny Mall Properties its permits was

the socio-economic harm to New Haven

which the Corps perceived would result

from a mall anywhere in North Haven.

This harm was not proximately related to

any impact the development would have on

the natural, environment.. Thus, the

Corps' decision was not in accordance

with law.

It is elementary, but appropriate to

note, that in our system of government,

decisions concerning which competing con

stituency's economic interests ought to

be preferred are traditionally made by

74a

democratically accountable officials.

The Corps seemed to recognize this when

it concluded its lengthy review process

by consulting the Governor of Connecticut

concerning whether building a mall in

North Haven was worth the risk to the

economy of New Haven.

The statutes implicated in this case

were enacted to protect the natural envi

ronment. Apparently the Corps was given

a central role in this process because of

its expertise in matters relating to our

nation's waterways. There is no sugges

tion that it was perceived by those

enacting the relevant statutes to have

expertise concerning whether the economic

interests of aging cities or their newer

suburbs should as a matter of public pol

icy be preferred.

This court is not now called upon to

determine whether the delegation to a

75a

group of military engineers of such

broad, discretionary authority to deter

mine public policy would be legally per

missible, reasonable, or desireable.

Rather, the court is called upon to dis

cern statutory intent. As the Supreme

Court noted in Metropolitan Edison, how

ever, a broad grant of authority to the

Corps to decide general public policy

issues would require an agency to seek to

develop expertise "not otherwise relevant

to [its] congressionally assigned func

tion." 460 U.S. at 776. This could

cause "the available resources [to] be

spread so thin that [the Corps in this

case would be] unable adequately to pur

sue protection of the physical environ

ment and natural resources." Id. In

Metropolitan Edison the Supreme Court

found it could not "attribute to Congress

the intention to ... open the door to

76a

such obvious incongruities and undesire-

able possibilities." Id. (quoting United

States v. Dowd. 357 U.S. 17, 25 (1958)).

This court reaches the same conclu

sion in this case. The relevant statutes

do not reveal an intention to empower the

Corps to decide whether to issue permits

based upon an assessment of economic ef

fects unrelated to impacts on the natural

environment. Nor do the relevant regula

tions reflect an intention to attempt to

exercise such power. In the circum

stances of this case the court will not

attribute to Congress and the President

the intention to delegate to the Corps

the power to deny Mall Properties a per

mit because a mall anywhere in North

Haven would, in its view, unduly injure

the economy of New Haven while benefit-

ting North Haven. Here, as in Metropoli

tan Edison, "the political process, and

77a

not [Corps proceedings] provides the ap

propriate forum in which to air [such]

policy disagreements." Id. at 777.

D . The Meeting with the Governor

The plaintiffs contend that the

Corps did not act in accordance with law,

but rather acted without observance of

procedure required by law, when it failed

to follow the procedures established by

the relevant regulations relating to a

meeting with the Governor of Connecti

cut. The Court agrees that the Corps did

not follow the legally required proce

dures relating to the meeting. This too

necessitates a remand.

On July 19, 1985 Colonel Sciple and

William F. Lawless, Chief of the Regula

tory Branch of the Corps, met with the

Governor of Connecticut to discuss the

position of the Governor on the construc

tion of the mall. At that meeting the

78a

Governor "indicated that he felt it was

not worth the risk to New Haven of build

ing the North Haven Mall." ROD at 47.

On August 25, 1985, the Colonel issued

his decision. The reference to the posi

tion of the Governor, expressed at their

recent meeting, is the last factor men

tioned before the Colonel stated that, "I

have therefore concluded, that this pro

ject is contrary to the public interest

and the permit is denied." Id.

The meeting between the Corps and

the Governor was not itself prohibited as

an ex parte contact. 33 C.F.R. §

320.4(j)(3) provides that: "[a] proposed

activity may result in conflicting com

ments from several agencies within the

same state. Where a state has not desig

nated a single responsible coordinating

agency, district engineers will ask the

79a

Governor to express his views or to des

ignate one state agency to represent the

official state position." Thus, the

meeting itself was not improper.

An issue in this case, however, is

generated by 33 C.F.R. § 325.2(a)(3),

which states: "At the earliest practic

able time, the applicant must be given

the opportunity to furnish the district

engineer his proposed resolution or re

buttal to all objections from other Gov

ernment agencies." It is evident that

the Colonel construed the Governor's com

ments as an objection to the proposed

mall. It is undisputed that Mall Proper

ties was not informed of the meeting or

of the Governor's objection until after