Allied Chemical Corporation v. White Memorandum for the United States as Amicus Curiae

Public Court Documents

November 1, 1977

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Allied Chemical Corporation v. White Memorandum for the United States as Amicus Curiae, 1977. 32e9979e-b79a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/34a54ec2-f1e3-471a-ac1d-9a7832e723c5/allied-chemical-corporation-v-white-memorandum-for-the-united-states-as-amicus-curiae. Accessed February 22, 2026.

Copied!

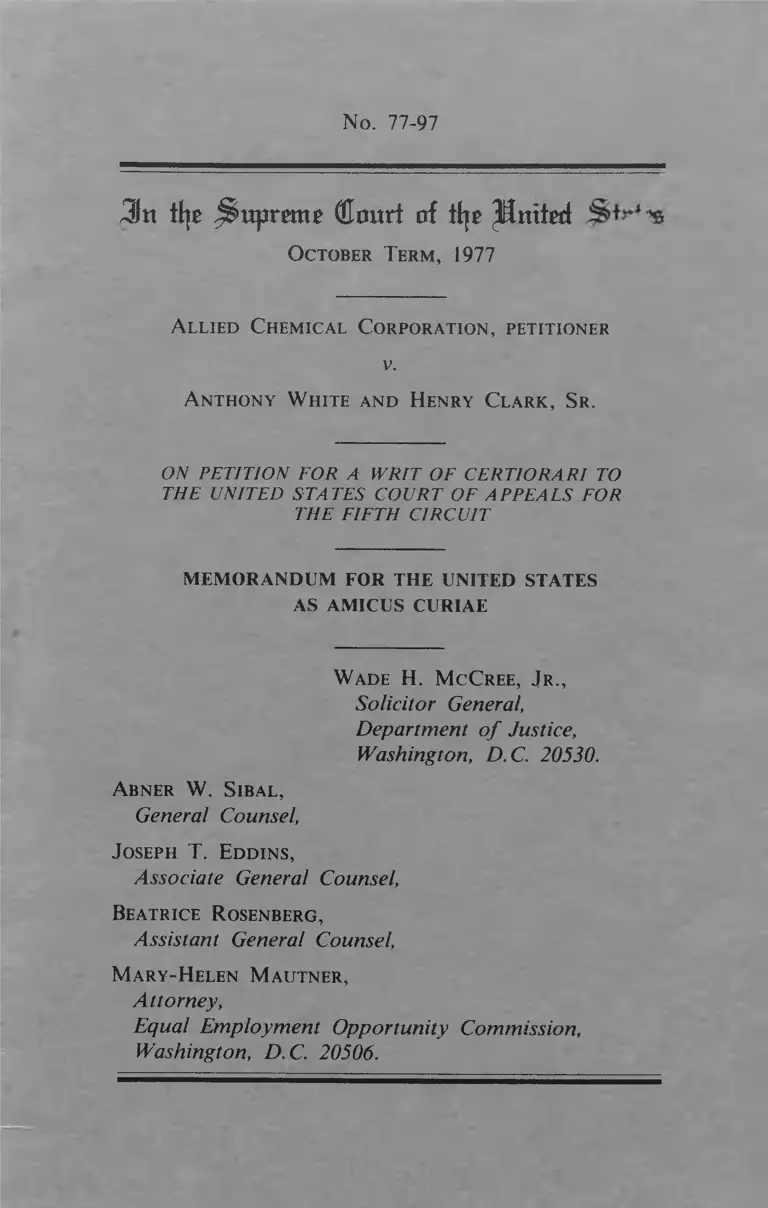

No. 77-97

Jtt tl|E Supreme Court of itje Putted

October Term, 1977

Allied C hemical Corporation, petitioner

v.

Anthony White and Henry Clark, Sr .

ON PETITION FOR A WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO

THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS FOR

THE FIFTH CIRCUIT

MEMORANDUM FOR THE UNITED STATES

AS AMICUS CURIAE

Wade H. McCree, J r .,

Solicitor General,

Department o f Justice,

Washington, D.C. 20530.

Abner W. Sibal,

General Counsel,

J oseph T. Eddins,

Associate General Counsel,

Beatrice Rosenberg,

Assistant General Counsel,

M ary-H elen M autner,

Attorney,

Equal Employment Opportunity Commission,

Washington, D.C. 20506.

3u tlrje Supreme Court of tt|e Putted States

October Term, 1977

No. 77-97

Allied Chemical Corporation, petitioner

v.

Anthony White and Henry Clark, Sr .

ON PETITION FOR A WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO

THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS FOR

THE FIFTH CIRCUIT

MEMORANDUM FOR THE UNITED STATES

AS AMICUS CURIAE

This memorandum is submitted in response to this

Court’s order of October 3, 1977, inviting the Solicitor

General to express the views of the United States with

respect to this case.

This suit arises out of a complaint filed by respondents

seeking to intervene as plaintiffs in a successful suit

against petitioner Allied Chemical Corporation challeng

ing a seniority system as violative of Title VII of the Civil

Rights Act of 1964. During a reduction-in-force,

respondents were laid off pursuant to the application of

the challenged seniority system and sought back pay relief

similar to that obtained by the named plaintiffs. The

challenged layoffs had occurred soon after the signing of a

conciliation agreement with the Equal Employment

Opportunity Commission, and Allied Chemical moved to

(1)

2

dismiss respondents’ intervention complaint on the

ground that respondents had signed the agreement which

contained a clause waiving their right to sue. T he district

court dismissed the action stating (Pet. App, D-2):

The gist of the intervenors’ position is that they

entered into the EEOC agreement without proper

legal advice and that they were not advised at the

time of available alternate procedures. We do not

believe that this is sufficient grounds for the

intervenors to ignore the EEOC agreement and

attempt to pursue this litigation.

The court of appeals reversed. Finding “at least some

evidence before the [district] court * * * that the waivers

were signed with less than full knowledge of the bargain

that was being struck” (Pet. App. A-7 n. 5), the court of

appeals remanded the case to the district court for a

hearing to determine whether the intervenors “knowingly

and voluntarily” waived their rights by signing the

conciliation agreement (Pet. App. A-7).

1. In Alexander v. Gardner-Denver Co., 415 U.S. 36,

52 n. 15, this Court stated that a district court faced with

an asserted waiver of rights granted by Title VII should

determine “at the outset that the employee’s consent to

the settlement was voluntary and knowing.” The courts of

appeals thus far have had little occasion to consider the

application of this requirement in concrete situations,

although the Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit has

held that the proponent of a Title VII release must meet

the “classic test” by showing that the release “ ‘was

executed freely, without deception or coercion, and that it

was made * * * with full understanding of [the waived]

rights. United States v. Allegheny-Ludlum Industries,

Inc., 517 F. 2d 826, 861. The requirement that knowing

and voluntary action precondition any forfeiture of Title

3

VII rights is appropriate because of the fundamental

importance of equal employment guarantees. On the

other hand, requirements aimed principally at the dangers

of deception and coercion cannot be utilized lightly to

upset settlement agreements negotiated in good faith by

all parties. Conciliation and negotiation are the “preferred

means” of resolving Title VII claims. Alexander v.

Gardner-Denver Co., supra, 415 U.S. at 44. The Equal

Employment Opportunity Commission negotiates ap

proximately 7,000 such conciliation agreements each year

and all those who are affected by Title VII have an

interest in preserving the viability of the conciliation

process, which depends in part upon the finality of

negotiated settlement agreements. This tension between

the requirement of legitimacy in the waiver process and

the need for dependable finality in settlement agreements

imposes special responsibilities upon the district courts in

ruling on claims by persons who have signed waiver

agreements.

2. In the instant case, respondents who were signatories

to a negotiated Title VII settlement sought to intervene in

a subsequent private Title VII action claiming that their

written waiver of Title VII claims against petitioner was

not knowing and voluntary within the meaning of

Alexander v. Gardner-Denver Co., supra. Because of the

way in which the issue was litigated in the district court,

the specific nature of respondents’ claims has not yet been

clarified. The complaint in intervention filed by re

spondents did not address their waiver claim, and it was

not adequately illuminated by the parties in depositions or

subsequent written motions. As the court of appeals

noted, there is some evidence in the record indicating that

“the waivers were signed with less than full knowledge of

the bargain * * * being struck” (Pet. App. A-7). However,

there is nothing to indicate whether this lack of

4

knowledge is allegedly the result of deception, failure of

the Commission attorneys to explain the settlement,

ambiguity in the document or waiver provision itself, or

respondents’ failure to make any effort to understand the

agreement they signed. It therefore cannot be determined

on the present record whether in fact respondents have

presented the type of claim that might render their signed

waiver inoperative under the standard announced in

Gardner-Denver.

Without obtaining a more precise understanding of the

cause of respondents’ alleged lack of knowledge, the

district court dismissed their intervention complaint based

upon its view of the “gist of the interveners’ position” and

its conclusion that the purpose of conciliation agreements

is to avoid further litigation (Pet. App. D-2). The court of

appeals correctly found this precipitous disposition

inappropriate “[i]n light of the recently— expressed deep

concern [in Alexander v. Gardner-Denver Co., supra, and

Watkins v. Scott Paper Co., 530 F. 2d 1159 (C.A. 5)] over

the necessity for establishing voluntariness before finding

an effective waiver of * * * plaintiffs Title VII rights”

(Pet. App. A-7). In light of the district court’s peremptory

disposition, as well as some evidence that respondents

lacked knowledge of the agreement they signed, the court

of appeals did not exceed its authority in requiring the

district court to hold a hearing to determine whether the

waiver was “knowing and voluntary.” A hearing at which

the district court can determine the reasons for the

claimed misunderstanding is not only appropriate for a

proper initial determination on the waiver issue, but also

will facilitate any subsequent review by the court of

appeals or by this Court.

Petitioner claims (Pet. 8), however, that the opinion of

the court of appeals “would now permit a vast backlog of

complex conciliation agreements to be reopened on the

5

allegation that a party thereto did not fully understand

the benefits he or she got, or did not get, under the

agreement.” This contention rests upon a single sentence

in the opinion that states “the district court erred in

dismissing the complaints in intervention * * * without

* * * holding a hearing to determine whether in fact they

comprehended the rights they were relinquishing when

they signed the October 1971 EEOC conciliation

agreement” (Pet. App. A-7). While the sentence is not

without ambiguity, it need not, and should not, be read

out of the factual context of this case in which the

presence of evidence of misunderstanding was combined

with precipitous disposition of still undefined claims that

important rights were invalidly waived. The opinion does

not require a hearing in every case in which claims are

made that settlement agreements were not knowing or

voluntary. If the district court, through discovery, the

pleading process or other means, had precisely defined the

claims before it as involving nothing more than a failure

to comprehend a complex agreement, summary disposi

tion would not have been improper. The opinion of the

court of appeals is not to the contrary, and that court’s

refusal to permit precipitous dismissal of respondents’

half-understood claims therefore does not merit further

review by this Court.

Finally, as petitioner acknowledges, the court of

appeals’ opinion “fail[s] to set any substantive standards

for such hearings” (Pet. II). Indeed, the court of appeals

simply tracks the language of this Court in stating that on

remand the district court should determine whether “the

interveners did not knowingly and voluntarily waive their

rights” (Pet. App. A-7). If the hearing in the district court

shows no more than a lack of understanding, the district

court should dismiss respondents’ complaint in interven

tion in light of the explicit waiver of Title VII rights they

6

signed. Our reading of the record thus far developed

suggests no reason to anticipate any other result.

3. Our conclusion that neither the court of appeals’

decision here nor this Court’s decision in Gardner-Denver

requires the employer to prove “that each employee

[actually] understood * * * the conciliation agreement

which had been negotiated * * * under the close

supervision of the EEOC” (Pet. App. B-2), does not mean

that we agree with petitioner that the sole grounds for

declaring a waiver inoperative would be “fraud or

substantial wrongdoing by EEOC” (Pet. 6). For example,

there may well be situations where the ambiguity of

waiver clauses and the inadequacy of explanations offered

by attorneys would void a waiver of Title VII rights in the

absence of claims of fraud or substantial wrongdoing. See

Watkins v. Scott Paper Co., 530 F. 2d 1159, 1170-1172

(C.A. 5), certiorari denied, 429 U.S. 861. The courts of

appeals have not yet had occasion to apply the knowing

and voluntary requirement to many such claims. The lack

of cases suggests that there may be little need to consider

the application of that standard now, before the courts

have dealt with the question in a variety of circumstances.

This case, moreover, presents the question of the

appropriate standard for reviewing waiver claims in only

hypothetical form on the present undeveloped record. The

court of appeals’ opinion is brief and unspecific; it

essentially requires the district court to make its decision

based upon this Court’s language in Gardner-Denver. The

district court may well reject respondents’ attempt to void

their waiver, and thereby perhaps eliminate the need for

further consideration of the issue here. The interlocutory

posture of the case therefore makes it inappropriate for

review at this time. Should the district court apply an

incorrect standard in considering respondents’ claim,

further appellate review would be available.

7

It is therefore respectfully submitted that the petition

for a writ of certiorari should be denied.

Wade H. McCree, J r .,

Solicitor General.

Abner W. S ibal,

General Counsel,

J oseph T. Eddins,

Associate General Counsel,

Beatrice R osenberg,

Assistant General Counsel,

M ary-H elen M autner,

Attorney,

Equal Employment Opportunity Commission.

November 1977.

D O J -1977-11

Supreme Court of the United States

Memorandum

.... m .2.P

h *C c - ,