Lemon v. Bossier Parish School Board Brief for Appellants

Public Court Documents

January 17, 1970

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Lemon v. Bossier Parish School Board Brief for Appellants, 1970. 35b24c11-bb9a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/34aa8c21-8b87-4a4d-a30c-6e04578179a4/lemon-v-bossier-parish-school-board-brief-for-appellants. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

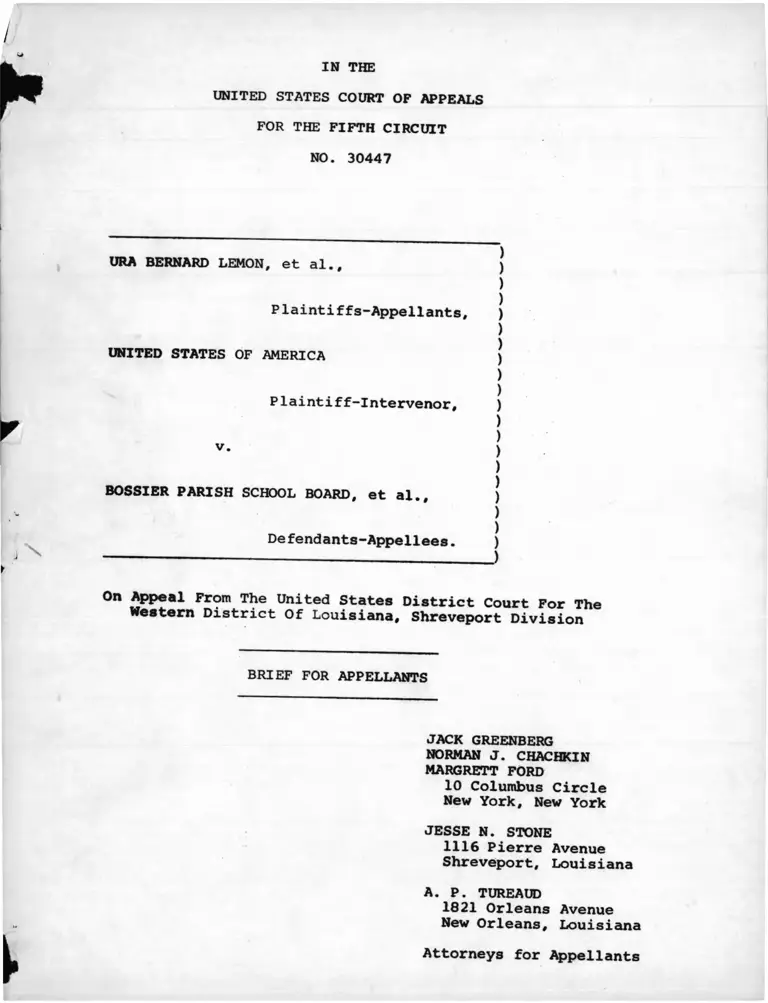

IN THE

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE FIFTH CIRCUIT

NO. 30447

URA BERNARD LEMON, et al..

Plaintiffs-Appellants,

UNITED STATES OF AMERICA

Plaintiff-intervenor,

v.

BOSSIER PARISH SCHOOL BOARD, et al.,

De fendants-Appellees.

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

.)

On Appeal From The United States District Court For The

Western District Of Louisiana, Shreveport Division

BRIEF FOR APPELLANTS

JACK GREENBERG

NORMAN J. CHACHKIN

MARGRETT FORD

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York

JESSE N. STONE

1116 Pierre Avenue

Shreveport, Louisiana

A. P. TUREAUD

1821 Orleans Avenue

New Orleans, Louisiana

Attorneys for Appellants

Table of Cases

Page

Allen v. Board of Public Instruction of

Broward County, No. 30032 (5th Cir.,

August 13, 1970) . . . . . 10

Berry v. School Dist. of Benton Harbor, C.A.

No. 9 (W.D. Mich., February 17, 1970) . 18

Bivins v. Board of Educ., 424 F.2d 97 (5th

Cir. 1970) ........ . 11

Brown v. Board of Educ., 347 U.S. 483 (1954) . 13, 14

Carter v. West Feliciana Parish School Bd.

396 U.S. 226 (1969) . . . . 4

Clark v. Board of Educ. of Little Rock, 426

F .2d 1035 (8th Cir. 1970) . . . . 10, 12

Dove v. Parham, 282 F.2d 256 (8th Cir. 1960) . 12, 19

Gaston County v. United States, 395 U.S 284 (1969)................... . 18

Green v. County School Bd. of New Kent Countv

391 U.S. 430 (1968) . . . . 2, 20, 23

Hall v. St. Helena Parish School Bd., 417 F.2d

801 (5th Cir.), cert, denied, 396 U.S904 (1969)............. • 3, 10

Henry v. Clarksdale Municipal Separate School

Dist., 409 F .2d 682 (5th Cir.), cert,

denied, 396 U.S. 940 (1969) . 10

Henry v. Clarksdale Municipal Separate School

Dist., No. 29165 (5th Cir., August 12, 1970) ........... . 10

Hightower v. West, No. 29933 (5th Cir.. Julv 14, 1970) . . . . y . 11

Hilson v. Ouzts, n o . 30184 (5th Cir., August 20, 1970) . . . . 10

Hilson v. Ouzts, No. 29216 (5th Cir., April 3, 1 9 7 0 ) ......... P 11

Hobson v. Hansen, 269 F. Supp. 401 (D.D.C.

1967), aff'd sub nom. Smuck v. Hobson,

408 F .2d 175 (D.C. Cir. 1969) 16, 19, 20

Jackson v. Marvell School Dist. No. 22, 425

F.2d 211 (8th Cir. 1970) . . 11

- X V -

Table of Cases (continued)

United States v. Sunflower County School Dist.,

No. 29950 (5th Cir., August 13, 1970) . [

United States v. Tunica County School Dist

421 F . 2d 1236 (5th Cir. 1970)

United States v. Webster County, No. 29769

(5th Cir., July 7, 1970) .................

I

Youngblood v. Board of Public Instruction of

Bay County, No. 29369 (5th Cir., July 24,

1970) ........................

Page

. 11

. 11

. 11

. 22

IN THE

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE FIFTH CIRCUIT

NO. 30447

)

URA BERNARD LEMON, et al., )

)

)

Plaintiffs-Appellants, )

)

)UNITED STATES OF AMERICA )

)

)

Plaintiff-Intervenor, )

)

)v. )

)

)BOSSIER PARISH SCHOOL BOARD, et al., )

)

)

Defendants-Appellees. )

___________________________________________________ )

On Appeal From The United States District Court For The

Western District Of Louisiana, Shreveport Division

BRIEF FOR APPELLANTS

Issues Presented for Review

1. Whether a school district which has been segregated and

dual throughout its history, except for one short semester

during which contiguous black and white schools were paired,

may implement a new plan of pupil assignment which results

-2-

in the assignment of a majority of black students to a

91% black school.

2. Whether the use of achievement test scores to assign

students in a desegregating school district to separate

school facilities and district curricular programs violates

the Fourteenth Amendment.

3. Whether the availability of other assignment methods, which

retain the professed educational values of the plan approved

below but eliminate the segregation which it creates, requires

reversal of the district court's decision under the test of

Green v. County School Bd. of New Kent Countv. 391 U.S. 430

(1968) .

-4-

Lemon v. Bossier Parish School Bd. . No. 28,745 (5th Cir.,

Dec. 12, 1969) .-2/

On remand, the district court entered an order January 20,

1970 directing implementation of the HEW plan for the Plain

Dealing area of the parish effective with the second semester

of the 1969-70 school year.

2. The School District Plan

April 29, 1970, the district court entered ex parte "Findings

of Fact and Decree Relating to Consolidated School District Number 1,

Plain Dealing, Louisiana" approving a new plan of operation for the

schools in Plain Dealing.-^

3/ Following the decision in Carter v. West Feliciana Parish School

Bd̂ _, 396 U.S. 226 (1969), appellants filed a Motion for Recall

and Amendment of Mandate and on January 6, 1970, this court

ordered that the school board "take no steps which are incon

sistent with, or which will tend to prejudice or delay, a

schedule to implement on or before February 1, 1970, desegre

gation plans submitted by the Department of Health, Education

and Welfare for student assignment simultaneous with the other

steps previously ordered by us in Singleton v. Jackson Municipal

Separate School District, No. 26,288, slip opinion dated

December 1, 1969." Lemon v. Bossier Parish School Bd.. No.

28745 (5th Cir., Jan. 6, 1970).

—/ Court found that the school board after months of consultation

with experts, and community leaders and educators, both black and

white, ha[d] devised a plan which is calculated to educate and

train each student according to his abilities.

The School Board plan incorporated into the attached decree has

broad support from all segments of the Plain Dealing community,

both black and white. This Court has personally interviewed

black educators and community leaders to determine this community

support.

-5-

The board's plan consolidated the two schools in Plain Dealing

into a single administrative unit; however, two physically separate

and functionally different programs — vocational and college

preparatory — were established for grades 4-12. Vocational

courses are not generally given until the ninth grade but voca

tional program students in the lower grades receive remedial

instruction.

Students were assigned to the college preparatory program

or the vocational program on the basis of their past composite

scores on the California Achievement Tests complete battery

(Tr. 157-59) ' Students in grades 4-6 who scored six months or

more below grade level were assigned to the vocational program,

as were students in grades 7-12 who scored eight months or more

below grade level; the remainder of the students were assigned

to the college preparatory program at the north campus (the

formerly all white school) (Tr. 90). In order to move from one

program to another, the student or his parent must apply for a

transfer (Tr. 38) and the request must be approved by a majority

of an "educational review committee" composed of teachers and

other employees of the school district (Tr. 15, 42).

Initial assignments for 1970-71 made on the basis of past

scores on the California Achievement Test resulted in 286 white

students and 391 black students (58%) enrolled in the college

5/ References are to the transcript of depositions of August 6,

1970.

-6-

oriented program at the north campus (the former white school),

and 42 white students and 419 black students (91%) in the

vocational training-remedial program at the south campus (the

former black school) (Tr. 90, 131). The two campuses are

located three blocks apart (Tr. 123).

3. Proceedings in the district court and this Court

May 14, 1970, appellants (plaintiffs below) filed a motion

for an extension of time within which to file a Motion for New

Trial, which was granted; such a Motion was filed June 26, 1970

seeking reconsideration of the April 29 ex parte order. The

district court set the matter down for a hearing on August 7, 1970.

Thereafter appellees advised counsel that they planned to

call numerous witnesses at the hearing, and that the scheduled

time would probably be insufficient. Appellees therefore sought

and were granted permission by the district court to introduce

evidence by way of depositions, which were taken August 6, 1970.

However, the court reporter stated that the transcript of the

depositions would not be available until after the commencement

of the school year. Plaintiffs accordingly filed a Motion for

Injunction Pendente Lite August 20 seeking either a decision on

the merits or, if the court declined to rule without the transcript,

entry of an injunction pendente lite requiring continued adherence

to the HEW plan until the court could render its decision upon

-7-

plaintiffs1 challenge to the testing plan. The district court

denied plaintiffs' motion for an injunction and declined to rule

without the transcript on August 24, 1970. Notice of Appeal was

filed August 26, 1970.

The same day, appellants filed a Motion for Injunction Pending

Appeal which was granted by this Court on September 2, 1970.

September 8, 1970, this Court denied appellees' request for a

five-day stay of the injunction pending appeal. September 29,

1970, this Court entered an order denying petition for rehearing

by appellees.

The transcript of the depositions was filed in the district

court on or about September 23, 1970; thereafter, appellees again

presented modification of their plan to the district court ex

parte, which entered an order October 1, 1970 approving the plan

as modified: (1) by providing that one required course be avail-

able at each campus only.2 s (2) by establishing a bi-racial

committee; and (3) by requiring HEW to consult with the parties

and report on the plan to the court. Appellants filed another

Motion for Injunction with this Court on October 6, ruling on

which was deferred pending submission of briefs by order dated

October 14, 1970.

No enrollment report has been filed by appellees nor has HEW

contacted plaintiffs as of the date this brief is prepared.

6/ [Thus, all students would be transferred from one campus

to the other for at least one course]

-8-

ARGUMENT

The Plan Approved By The District

Court Embodies A Racial Classi

fication Justified Neither On

Educational Grounds Nor in Light

of the Alternatives Available To

The School District

This case presents the narrow but critical issue

whether this school district may utilize achievement test

scores to assign pupils to school buildings and differen

tiated curricular programs where the actual result of such

a plan is to recreate a "black" school bearing the additional

stigma of being a "lower track" school. Our argument is

on several levels: first, that in the context of past

segregation in the district, unaltered except for one brief

semester, the Constitution forbids this racial classification,

no matter what sort of educational justification is offered

for it. Second, if the board's professed theories are to

be weighed, the evidence in this case and recent rulings

on the subject fail to support the use of standardized test

scores for assignment of students to buildings, for they are

inherently discriminatory and unreliable. Third, we argue

alternatively that even accepting appellees' own statements

of purpose, the ready availability of other pupil assignment

techniques to achieve the same purpose which do not involve

the creation of a 91%-black school renders the board's plan

indefensible.

-9-

This appeal does not involve appellees' right to

institute a program of vocational education in the Plain

7/

Dealing area. Disposition in appellants' favor will not

require the school board to undo any renovation it has made

at the former black (south campus) school for the purpose

of accommodating vocational training equipment. What is

involved in the nature of a pupil assignment plan which

isolates more than half the black children in the Plain Deal

ing area in a virtually all-black school.

A. The Board's Plan is an Impermissible Racial Classification

Scheme

Let there be no mistake: the plan approved below

classifies racially, regardless of its intent. It produces a

lower-track school to be attended overwhelmingly by Negroes

7/ The black witnesses called by appellees vigorously supported

the decision to offer vocational training in a wide range

of subjects in Plain Dealing schools (Tr. 9, 246, 270), Which

the black community had been seeking for some time (Tr. 245).

It is less clear that the witnesses were enthusiastic about,

the tracking provisions of the plan. Mr. Lee, for example,

saw no problem in continuing the pairing along with the voca

tional program, but said:

This is a plan which has been issued by the

courts, and now what I am trying to do is

implement it according to what the court says

[Tr. 46]. . . .

I am only looking at the court order as it was

issued. Now if the court made its mistake

in approving another plan, I have nothing to

do with that. . . . And how it went out according

to the court order I don't know the reasons as

to why it was changed or what. I could have no

— nothing that I could actually say from facts

that prevented them from carrying out the plan on

as it was, I don't know [Tr. 53-54].

See also, Tr. 45. Mr. Wattre said he would have preferred to

keep all students on a grade level together (Tr. 253).

-10-

in this district wherein but for the second semester of

the past school year, a completely dual, segregated school

system was operated. The historic overlapping black and

white school attendance areas have been maintained until

quite recently by a variety of devices, including freedom

8/of choice. Hall v. St. Helena Parish School Bd., supra.

The question here presented is whether a pupil assignment

plan whose effect is to reestablish the racial classification

is constitutional in these circumstances.

We emphasize that this plan must be judged in

terms of its effect, and not the professed intention with

which it was implemented. E .g ., Keyes v. School Dist. No. 1,

Denver, 303 F. Supp. 279, 286-87 (D. Colo. 1969); Clark v.

Board of Educ. of Little Rock, 426 F.2d 1035 (8th Cir. 1970);

Henry v. Clarksdale Municipal Separate School Dist., 409 F.2d

682 (5th Cir.), cert, denied, 396 U.S. 940 (1969). And

where the effect is a racial classification, the state's

burden of justification is especially severe. E.g., McLaughlin

v. Florida, 379 U.S. 184 (1964).

8/ The HEW plan which was implemented during the spring, 1970

semester by direction of this Court, completely eliminated

the dual school system by the recognized educational tool of

contiguous pairing, which has been consistently sanctioned

by this Court. E.g., Hall, supra; Allen v. Board of Public

Instruction of Broward County, No. 30032 (5th Cir., August

13, 1970); Henry v. Clarksdale Municipal Separate School

Dist., No. 29165 (5th Cir., August 12, 1970); Hilson v. Ouzts,

No. 30184 (5th Cir., August 20, 1970).

-11-

in the circumstances of a school district undergoing

initial desegregation, there can be no justification for the

re-imposition of racial classifications. That is the import,

for example, of this Court's related holdings in Singleton

v. Jackson Municipal Separate School Dist., 419 F.2d 1211,

1219 (5th Cir. 1969); United States v. Tunica County School

Dist., 421 F.2d 1236 (5th Cir. 1970) and United States v.

Sunflower County School Dist., No. 29950 (5th Cir., August 13,

1970) barring the use of achievement tests for the purpose of

pupil assignment in school systems which are not yet unitary.

Perhaps this case falls within that proscription despite

implementation of the HEW pairing plan in Plain Dealing for

a short semester. Such a ruling, however, would merely

postpone rather than resolve the issue. We submit that in

the context of past segregation only so recently ameliorated

to any degree, any plan whose effect is to reestablish racially

identifiable schools is a constitutionally impermissible

. 2/racial classification.

9/ We do not think appellees' plan is saved by the inclusion

in the district court's October 1, 1970 decree of the

requirement that all students at each campus take on required

course at the other campus. For one thing, nothing in the

plan indicates that the transfers will not be of intact

classes, see McNeese v. Board of Educ., 199 F. Supp. 403

(D. 111. 1960), aff'd 305 F.2d 783 (7th Cir. 1962), rev'd

373 U.S. 668 (1963), resulting in segregated classes.

Johnson v. Jackson Parish School Bd., 423 F.2d 1055 (5th Cir.

1970); Jackson v. Marvell School Dist. No. 22, 425 F.2d 211

(8th Cir. 1970). For another, such part-time desegregation

has been rejected as unsatisfactory by this Court. Hightower

v. West, No. 29933 (5th Cir., July 14, 1970); Hilson v. Ouzts,

No. 29216 (5th Cir., April 3, 1970); Bivins v. Board of Educ.,

424 F.2d 97 (5th Cir. 1970); United States v. Webster County,

No. 29769 (5th Cir., July 7, 1970).

-12-

The rule was well expressed by the Eighth Circuit

in Dove v. Parham, 282 F.2d 256, 258 (8th Cir. 1960):

Standards of placement cainot be de

vised or given application to preserve

an existing system of imposed segregation.

Nor can educational principles and

theories serve to justify such a result.

These elements, like everything else,

are subordinate to and may not prevent

the vindication of constitutional rights.

An individual cannot be deprived of the

enjoyment of a constitutional right,

because some governmental organ may

believe that it is better for him and for

others that he not have this particular

enjoyment. . . .

In summary it is our view that the

obligation of a school district to

disestablish a system of imposed segre

gation, as the correcting of a consti

tutional violation, cannot be said to

have been met by a process of applying

placement standards, educational theories

or other criteria, which produce the

result of leaving the previous racial

situation existing, just as before. . . .

If placement standards, educational

theories, or other criteria used have

the effect in application of preserving

a created status of constitutional violation,

then they fail to constitute a sufficient

remedy for dealing with the constitutional

wrong.

Whatever may be the right of these things

to dominate student location in a school

system where the general status of

constitutional violation does not exist,

they do not have a supremacy to leave

standing a situation of such violation,

no matter what educational justification

they may provide, or with what subjective

good faith they may have been employed.

And see, Clark v. Board of Educ. of Little Rock, supra; Kelley

v. Altheimer, 297 F. Supp. 753, 757 (E.D. Ark. 1969).

This Court should declare the reestablishment of

racially identifiable schools impermissible, no matter what

the purported justification.

-13-

B. The Use of Standardized Test Scores to Assign Students to

Different School Buildings and to Vocational or Academic

Curricula Violates the Equal Protection Clause of the

Fourteenth Amendment_____

Appellees have proposed a plan to assign Plain

Dealing students to separate buildings and to distinct

academic or vocational programs according to their score,

in relation to national norms (Tr. 127), on achievement tests

(Tr. 88), in spite of the admitted weight of professional

opinion favoring individualized instruction within hetero

geneous groupings (Tr. 184). The virtue of such assignment,

the ostensible purpose of which is to permit application of

concentrated time and effort to the learning problems of

educationally deprived children (Tr. 115), is its supposed

objectivity: although its effect is to create a segregated

school, "it so happens that the numbers fall this way as

far as achievement is concerned" (Tr. 166).

The proposed "equal application" of an "objective"

test for all students as a basis for determining their place

ment in particular schools suffers from the same defect as

the separate but equal doctrine. The rationale of the Brown

decision was that public education, " . . . where the State

has undertaken to provide it, is a right which must be made

available to all on equal terms," and that segregated educa

tion is unequal education. This was also basically the

rationale of Sweatt v. Painter, 339 U.S. 629 (1950) and

McLaurin v. Oklahoma State Bd. of Regents, 339 U.S. 637 (1950).

These cases, predecessors of Brown, respectively held

-14-

violative of the separate but equal rule of Plessy v.

Ferguson, 163 U.S. 537 (1896), segregated law school and

graduate school education. They had as their basis the

fact that Negroes were treated unequally with respect to

qualities "incapable of objective measurement," in large

10/measure because they were isolated from the majority group.

The tests themselves are anything but objective

and are particularly unsuited for the use to which they are

now being put. The 1965 teachers' Manual for the California

11 /tests (Tr. 144)“— contains precautionary language about

interpreting the tests by using composite scores alone:

10/ in Sweatt, among the vital immeasurable ingredients

which the Court considered in the University of Texas

Law School as contrasted with the separate Negro law school

was the exclusion from the Negro institution of members of

racial groups which included most of the lawyers, judges,

witnesses, jurors and public officials with whom the Negro

law student would have to deal when he became a member of

the bar. The Court also considered the comparative standing

in the community of the two institutions.

In Brown, the Court ruled that the intangible considera

tions involved in depriving Negro students of the opportunity

for association with members of the majority group applied

"with added force" to children in elementary and secondary

schools, 347 U.S. at 494. The Court concluded, "[t]o separate

them [Negro children] from others of similar age and

qualifications solely because of their race generates the

feeling of inferiority as to their status in the community

that may affect their hearts and minds in a way unlikely ever

to be undone."

11/ it is unclear from the transcribed depositions whether

these exhibits have been transmitted to this Court. For

that reason, we are forwarding our single copies to the Clerk

for the Court's use.

-15-

. . . If ability and achievement within

a school system are either exceptionally

high or low, the norms for "typical"

populations are not appropriate standards

to use in evaluating test results without

making necessary adjustments. In such

districts, it may be advisable for school

personnel to set up local expectancies

in terms of percentiles, standard scores,

or stanines derived from their own

testing [p. 19].

Any deficiencies indicated by the Diagnostic

Analysis of Learning Difficulties should

be individually verified by the teacher or

counsellor. It then may be determined to

what extent the pupil requires remedial

work in specific skills or areas of learning.

The purpose of the Diagnostic Analysis is

to identify for further study those

particular areas in which deficiencies

in pupil performance may exist. In no case

should this rough screening be interpreted

as the sole or final indicator of a pupil's

strengths or weaknesses, since the small

number of items in some categories do not

provide sufficiently high reliabilities.

[p. 22]

Standardizes testing programs are adminis

tered for one principal purpose: to

improve instruction and learning. To this

end, it is essential in all uses and

interpretations of test results that school

personnel be aware of the mental or physical

handicaps, the social and emotional problems.

or the language difficulties which may

limit individual performance and achievement.

. . . [p. 24]

Individual data from teachers' observations

and cumulative records must be reflected

in the interpretation of Anticipated

Achievement Grade Placements. Individual

abilities, attention span, emotional

maturity, health status, breadth of exper

ience outside of school, motivations,

interests, and the like are all factors

to be considered to bring expectancies into

perspective. . . . [p. 45][all emphases supplied]

There are two sources of information about the uses

and abuses of achievement tests to which we refer t]ie Court.

-16-

The first is the record in No. 28261, Anthony v. Marshall

County Bd. of Educ., in which the issue was thoroughly

explored with expert testimony being taken. The question

was pretermitted on that appeal, decided sub nom. Singleton

v. Jackson Municipal Separate School Dist., supra. The

second is the decision in Hobson v. Hansen, 269 F. Supp. 401

(D.D.C. 1967), aff'd sub nom. Smuck v. Hobson, 408 F.2d 175

(D.C. Cir. 1969). Judge Wright's finding with regard to the

12/tests is relevant:

The evidence shows that the method

by which track assignments are made

depends essentially on standardized

aptitude tests which, although given

on a system-wide basis, are completely

inappropriate for use with a large

segment of the student body. Because

these tests are standardized primarily

on and are relevant to a white middle

class group of students, they produce

inaacurate and misleading test scores

when given to lower class and Negro

students. As a result, rather than

being classified according to ability

to learn, these students are in

reality being classified according to

their socio-economic or racial status,

or — more precisely — according to

environmental and psychological factors

which have nothing to do with innate ^3 /

ability. [footnote omitted] — '

269 F. Supp. at 514.

12/ The Hobson case is probably the most thorough review

of the validity of testing ever undertaken.

13/ The Washington tests were aptitude tests, but the

distinction between an aptitude test and an achievement

test is de minimus, particularly in this case. In Hobson,

the district court found (269 F. Supp. at 477)-:

A scholastic aptitude test is specifically

designed to predict how a student will

achieve in the future in an academic

curriculum.

-17-

The Department of Health, Education and Welfare

has stated its opposition to testing plans. At the request

of the United States District Court for the Northern District

of Mississippi, see United States v. Sunflower County School

Dist.. No. GC 6637-K (N.D. Miss., June 25, 1969), the Office

of Education commented upon such plans:

We feel obligated to express our serious

concerns about the educational merits of

the proposed Sunflower plan, especially

in light of "reasonably available other

ways promising speedier and more effective

conversion to a unitary non-racial system."

It is our clear judgment that the proposed

testing program will retain most aspects

of the dual school system due to the very

nature of standardized achievement and/or

aptitude tests. Much research has docu

mented that students from low socio-economic

backgrounds are disadvantaged in competing

with such tests since the tests are

standardized on student populations which

do not adequately represent low socio-eco

nomic students. Based on these factors,

we wish to make clear our strong feeling

that this plan is neither administratively

nor educationally sound. We also do not

believe the proposed plan " . . . achieves

the constitutional duty upon this school

district for the elimination of racially

segregated schools.

[See record in Anthony v. Marshall County Bd. of Educ., supra].

The California tests provide a soore measure labelled

"Anticipated Achievement" about which the Manual, supra, says

at p. 44:

The California Test Bureau, in its 1957

standardization of the California Test of

Mental Maturity Series and the California

Achievement Tests refined previous expec

tancy concepts by introduction of Anticipated

Achievement. The administration of the two

test batteries concurrently on a single

population provided comparable intelligence

and achievement normative data. The CAT

norms represent the Anticipated Achievement

of a certain grade placement and its related

chronological age. [footnote omitted]

-18-

The creation of black schools when tests are

used for the purpose of assignments is far from a fortuity,

as appellees suggest (Tr. 166). It is rather a self-fulfilling

prophecy, given the knowledge on the part of the district

that black children in the parish scored poorly on such

tests (Tr. 129). As this Court said in United States v.

Choctaw County Bd. of Educ., 417 F.2d 838, 841 n. 15 (5th

Cir. 1969),

School desegregation cannot be delayed

on the ground that Negroes have lower

educational levels than whites in the

same grades or age groups; that, there

fore, "compliance with the Supreme Court's

decision would be detrimental" to the

students. Stell v. Savannah-Chatham

County Board of Education (5th Cir. 1961),

318 F.2d 376; 333 F.2d 55; Jackson

Municipal School District v. Evers

(5th Cir. 1961), 357 F.2d 653. The

existing effects of past discrimination

do not justify perpetuating the

unconstitutional conditions which cause

the present educational inequalities.

Accord, United States v . Board of Educ. of Lincoln County,

301 F. Supp. 1024 (S.D. Ga. 1969)(rejecting a testing plan

and relying upon Stell and Evers); Monroe v. Board of Comm1rs

of Jackson. 427 F.2d 1005, 1008 (6th Cir. 1970)(". . . while

there may be some disparity in the achievement levels of

students from different socio-economic backgrounds, greater,

not less, student and faculty desegregation is the proper

manner in which to alleviate the problem."); Berry v. School

Dist. of Benton Harbor, C.A. No. 9 (W.D. Mich., February

17, 1970) (oral opinion). Cf. Gaston County v. United States,

395 U.S. 285 (1969); United States v. Local 189, U.P. & P.,

AFL-CIO, 282 F. Supp. 39 (E.D. La. 1968), aff’d 416 F.2d 980

(5th Cir. 1969).

-19-

This case is strikingly similar to Hobson since

the tracking system in Plain Dealing operates to lock a

student into one program, much like Pupil Placement, by

requiring a request for transfer (see Dove v. Parham, supra).

For that reason, we call the Court's attention to the

following significant passages in Hobson, which we submit are

precisely applicable here:

10. The aptitude tests used to assign

children to the various tracks are

standardized primarily on white middle

class children. Since these tests do

not relate to the Negro and disadvan

taged child, track assignment based on

such tests relegates Negro and disad

vantaged children to the lower tracks

. . . [269 F. Supp. at 407].

And Negroes read in the eyes of the

white community the judgment that

their schools are inferior and without

status, thus confirming and reinforcing

their own impressions. Particularly

is this true in Washington, where the

white community has clearly expressed

its views on the predominantly Negro

schools through the behavior of white

parents and teachers who, the court

finds, in large numbers have withdrawn

or withheld their children from, and

refused to teach in, those schools,

rId. at 420-21; cf. Tr. 61].

. . . the court cannot ignore the fact

that until 1954 the District schools

were by direction of law operated on a

segregated basis. It cannot ignore

the fact that of all the possible forms

of ability grouping, the one that won

acceptance in the District was the one

that — with the exception of completely

separate schools -- involves the greatest

amount of physical separation by grouping

students in wholly distinct, homogeneous

curriculum levels. It cannot ignore

that the immediate and known effect of

this separation would be to insulate

-20-

the more academically developed white

student from his less fortunate black

schoolmate, thus minimizing the impact

of integration; nor can the court ignore

the fact that this same cushioning effect

remains evident even today. Therefore,

although the track system cannot be

dismissed as nothing more than a sub

terfuge by which defendants are attempt

ing to avoid the mandate of Bolling v.

Sharpe, neither can it be said that

the evidence shows racial considerations

to be absolutely irrelevant to its

adoption and absolutely irrelevant to

its continued administration. To this

extent the track system is tainted,

[footnotes omitted][Id. at 443].

Appellants respectfully submit that the only kind

of ability grouping which is permissible is not based

primarily on standardized test scores, is not based on

separation by bui.1 dings or by rigid tracks but is a fluid

system of individualized instruction according to appropriate

performance levels in various subject matter areas. This

is, in fact, precisely the kind of ability grouping used

in Bossier Parish in the past (Tr. 47-48, 126, 269) and it

is the kind of ability grouping toward which the school

system is generally moving (Tr. 93, 118-19, 142-43). It is

the only kind of ability grouping the Constitution, and

this Court, should permit.

C. In Light of Alternative Pupil Assignment Plans Available

to this District Which Do Not Interfere With Its

Vocational or Remedial Programs And Which Establish A

Unitary System, the Decision Below Cannot Be Sustained

Under the Test Enunciated in Green v. County School Board

of New Kent County, 391 U.S. 430 (1968).

If there were any doubt about the racial design

and effect of the plan approved below, it is eliminated by

-21-

a consideration of the surrounding circumstances and the

alternatives available.

Appellees have claimed that the tracking program

they proposed was necessitated by (1) their introduction of

a vocational education program in the Plain Dealing area,

and (2) the need to centralize remedial resources. But

the evidence in this case shows that both of these objectives

can be accomplished fully without putting into effect a

plan which maximizes the segregation of more than half

the black students.

Initially, we note that Bossier Parish had never

before assigned students to different school buildings on the

basis of test scores or ability grouping (Tr. 156). Tests

have been used in the past to group students within

heterogeoneous classrooms for the purpose of individualizing

instruction (Tr. 126, 184) and are presently being used in

Bossier Parish for that purpose outside the Plain Dealing area

(Tr. 118-19, 142-43). The school board presently operates

a vocational-technical school to which students are transported

for half-day sessions (Tr. 179); in all of the schools outside

the Plain Dealing area, remedial instruction is offered

within each school rather than in a separate facility (Tr.

110, 156). It is significant, then, that the effect of

this single deviation from the parish's consistent educational

policy has been to move from a plan which called for all stu

dents in Plain Dealing on a given grade level to attend the

-23-

example placing the upper grades and the vocational offerings

at the south campus (E.q., Tr. 44, 46, 162). There is suffi

cient capacity in regular classrooms at the south campus to

accommodate such a program (Tr. 237-38). Shuttle buses now

operate between the schools (Tr. 123) which are three blocks

14/apart (ibid.). The only function the present plan can

serve — and the only function it does serve — is to separate

a majority of the black students in Plain Dealing in a black

facility.

The ultimate irony of this case is provided by

the features added by the district court in its October 1

decree, which require shuttling the entire school population

of Plain Dealing back and forth once each day to the other

school. Why the district insists upon this expensive and

time-consuming procedure is a mystery to appellants, but it

does illustrate very clearly that remedial services could

easily be located in one building and students for special

subject remedial classes transported to that location.

As the Court said in Green v. County School Bd. of

New Kent County, supra, 391 U.S. at 439, "the availability

to the board of other more promising courses of action may

indicate a lack of good faith; and at the least it places a

heavy burden upon the board to explain its preference for

an apparently less effective method." Appellants submit that

14/ Thus appellees' assertion (Tr. 172) that two sets of

remedial materials would be needed if the schools were

paired is an absurdity.

-24-

the availability of another method of pupil assignment which

is both more effective in terms of desegregation and at least

equally effective in carrying out the stated purposes of the

Bossier parish School Board to afford vocational and remedia

services is apparent on this record, and that appellees have

not supplied any constitutionally acceptable explanation for

their failure to adopt that method.

0

CONCLUSION

WHEREFORE, for the foregoing reasons, appellants

respectfully pray that the judgment below be reversed and

the district court instructed to reinstate the HEW pairing

plan as contained in its order of January 17, 1970.

NORMAN J. CHACHKIN

MARGRETT FORD

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

JESSE N. STONE

1116 Pierre Avenue

Shreveport, Louisiana

A. P. TUREAUD

1821 Orleans Avenue

New Orleans, Louisiana 70130

Attorneys for Appellants

CERTIFICATE OF SERVICE

I hereby certify that on this 30th day of October,

1970, I served two popies of the foregoing Brief for Appellants

upon counsel for defendants, J. Bennett Johnston, Jr., Esq.,

406 Lane Building, Shreveport, Louisiana and counsel for the

Utiitied States, Edward S. Christenbury, Esq., Civil Rights

Division, United States Department of Justice, Washington, D.C.

2(5530>.chy United States mail, air mail postage prepaid.