United States v. Georgia Power Company Reply Brief for Plaintiffs-Appellants

Public Court Documents

April 10, 1972

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. United States v. Georgia Power Company Reply Brief for Plaintiffs-Appellants, 1972. 980c1d70-c79a-ee11-be37-000d3a574715. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/34b9d202-905d-4738-bad7-751a71498774/united-states-v-georgia-power-company-reply-brief-for-plaintiffs-appellants. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

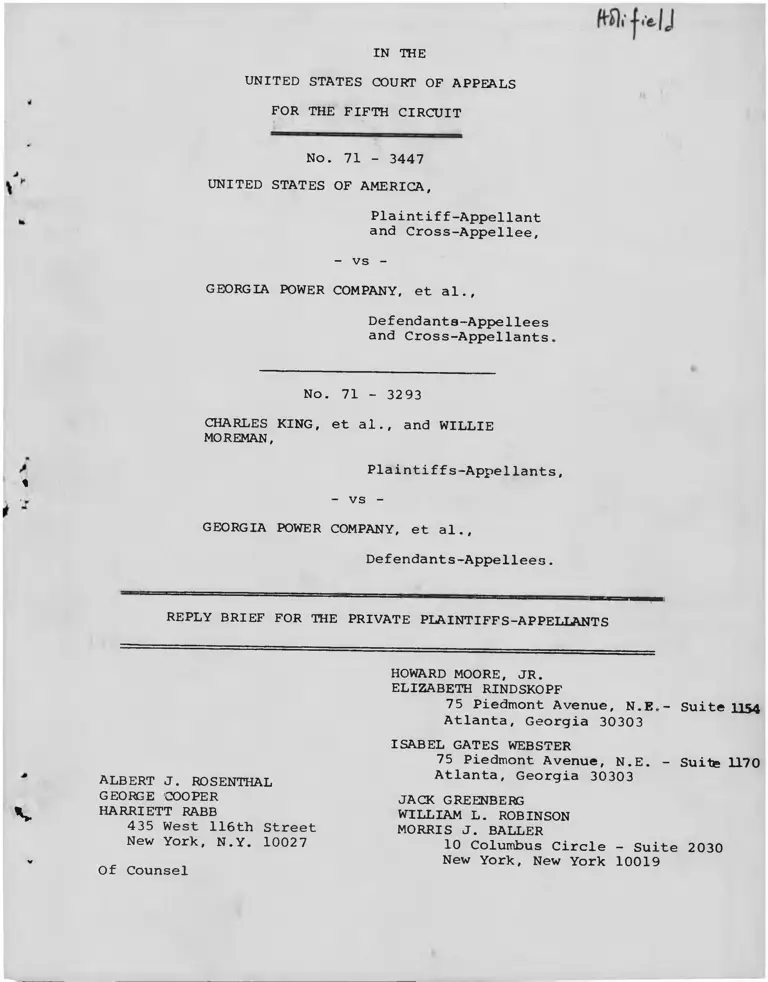

IN THE

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE FIFTH CIRCUIT

No. 71 - 3447

UNITED STATES OF AMERICA,

Plaintiff-Appellant and Cross-Appellee,

- vs -

GEORGIA POWER COMPANY, et al.,

Defendanta-Appellees and Cross-Appellants

H

No. 71 - 3293

CHARLES KING, et al., and WILLIE MOREMAN,

Plaintiffs-Appellants,

- vs -

GEORGIA POWER COMPANY, et al.,

Defendants-Appellees.

REPLY BRIEF FOR THE PRIVATE PLAINTIFFS-APPELLANTS

HOWARD MOORE, JR.

ELIZABETH RINDSKOPF

75 Piedmont Avenue, N.B,

Atlanta, Georgia 30303

ISABEL GATES WEBSTER

75 Piedmont Avenue, N.E.

- Suite 1154

- Suite 1170

albert J. ROSENTHAL Atlanta, Georgia 30303

GEORGE COOPER JACK GREENBERGV HARRIETT RABB WILLIAM L. ROBINSON435 West 116th Street MORRIS J. BALLER

V

New York, N.Y.

Of Counsel

10027 10 Columbus Circle - Suite 2030 New York, New York 10019

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Page

Introduction

ARGUMENT

THE DISTRICT COURT WAS CORRECT IN RULING THAT

THE COMPANY'S HIGH SCHOOL EDUCATION REQUIREMENT

WAS NEITHER VALID AS A PREDICTOR OF JOB

SUCCESS NOR JUSTIFIABLE AS A BUSINESS NECESSITY

4

II. THE COMPANY'S ARGUMENTS IN SUPPORT OF ITS

TESTING PROGRAM IGNORE THE MAJOR POINTS RAISED

BY PLAINTIFFS AND OFFER NO ADEQUATE JUSTIFICATION FOR CONTINUATION OF THE PROGRAM ..................

A. The Company's Argument Regarding the

Guidelines................................

B. The Company's Argument Regarding the Relation

ship of Its Tests to Job Performance

Proves Nothing............................

III. DEFENDANT'S ARGUMENTS SUGGEST NO VALID REASON TO

DENY CLASS-WIDE BACK PAY OR TO LIMIT THE INDIVIDUAL

AWARDS OF BACK P A Y ................................

A. The Company's Procedural Smokescreens . . . .

B. The Facts of This Case Demand Recognition of

the Class Members' Entitlement to Back Pay,

Notwithstanding Possible Difficulties in

Computing the Exact Amounts Due............

11

11

13

18

18

20

C. The Company's Opp>osition to IncreasedInvididual Awards Is Premised on Purely

Hypothetical and Erroneous Factual

Assumptions........................... 25

IV. THE APPLICABLE STATE STATUTE OF LIMITATIONS IS NOT

THE PROVISION ADVANCED BY DEFENDANT .............. 27

- 1 -

CONT'D Page

V. THE DISTRICT COURT FAILED TO GRANT ADEQUATE

SENIORITY RELIEF TO DISCRIMINATEES .................. 29

A. As to Pre-July 1963 Hirees...................... 29

B. As to Post-July 1963 H i r e e s .................... 29

C. As to Post-July 2, 1965 Victims of Discriminatory

Refusals to Hire.............................. 30

VI, THE COMPANY'S BRIEF OFFERS NO REASONS OR FACTS

SUFFICIENT TO DISPEL THE INFERENCE OF DIS

CRIMINATION IN INITIAL ASSIGNMENTS.................. 32

VII. THE GEORGIA POWER RECRUITMENT SYSTEM HAS AN

UNLAWFUL CHANNELLING EFFECT.......................... 35

VIII. THE COMPANY'S COUNSEL FEES ARGUMENT ASSUMES FACTS

WHICH ARE UNTRUE.................................... 35

CONCLUSION........................................................37

CERTIFICATE OF SERVICE ........................................

- 11 -

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

CASES Page

A & Z Rental, Inc. v. Wilson, 413 F.2d 899

(10th Cir. 1969)............................ 22

Boudreaux v. Baton Rouge Marine Contracting Corp.,

437 F.2d 1011 (5th Cir. 1971).................. 27

Burns Bros. Plumbers, Inc. v. Groves Ventures Co.,

412 F.2d 202 (6th Cir. 1969).................... 23

Eisen v. Carlisle & Jacquelin, 52 F.R.D. 253

(S.D.N.Y. 1971).................................. 23

Griggs v. Duke Power Co., 401 U.S. 424 (1971)............ 9

International Union v. Hoosier Cardinal Corp., 383

U.S. 696 (1966).................................. 28

Jenkins v. United Gas Corp., 400 F.2d 28 (5th

Cir. 1968)..................................... 22

Local 53, Asbestos Workers v. Vogler, 407 F.2d 1047(5th Cir. 1969)................................. 23

Local 189, United Papermakers & Paperworkers v.

United States, 416 F.2d 980 (5th Cir. 1969),

cert, denied 397 U.S. 919 (1970)............. 30,31

Long V . Georgia Kraft Co., 450 F.2d 557 (5th Cir. 1971) . 23

Mason-Rust v. Laborers Int'1 Union, Local 42, 435

F.2d 939 (8th Cir. 1970)....................... 23

N.L.R.B. V . Carpenters Union, Local 180, 433 F.2d 934(9th Cir. 1970)................................. 24

N.L.R.B. V . Miami Coca-Cola Bottling Co., 360 F.2d 569

(5th Cir. 1966) 24

N.L.R.B. V . Reynolds, 399 F.2d 668 (6th Cir. 1970) . . . . 24

N.L.R.B. V . Robert Haws Company, 403 F.2d 979 (6th

Cir. 1970)..................................... 24

- loi

Pa;4fe

Rental Development Corporation of America v. Lavery,

304 F.2d 839 (9th Cir. 1962)................. 19

Robinson v. Lorillard Corp., 319 F.Supp. 835

(W.D.N.C. 1970).............................. 25

Robinson v. Lorillard Corp., 444 F.2d 791

(4th Cir. 1971).............................. 14,18,19,20

Rosen v. Public Service Electric and Gas Co., 409F.2d 774 (3rd Cir. 1969)..................... 19

Rowe V. General Motors Corp., ___ F.2d ___, 4 EPD17689 (5th Cir. March 2, 1971).......... 21,33,36

Sheet Metal Workers Int'l Ass'n, Local 223 v. Atlas

Sheet Metal Co., 384 F.2d 101 (5thCir. 1967).................................. 22

Sprogis v. United Air Lines, Inc., 444 F.2d 1194 (7th

Cir. 1971), cert, denied 4 EPD 13588(1971)...................................... 19,23

Story Parchment Co. v. Patterson Co., 282 U.S. 555(1931)....................................... 22

Syres v. Oil Workers International Union, 257 F.2d 479

(5th Cir. 1958), cert, denied 358 U.S.929 (1958).................................. 23

Trinity Valley Iron & Steel Co., v. N.L.R.B., 410F.2d 1161 (5th Cir. 1969)..................... 24

United States v. Bethlehem Steel Corporation, 446F.2d 652 (2nd Cir. 1971)...................... 10,14

United States v. Hayes International Corp.,____F.2d___,4 EPD 17690 (5th Cir. Feb. 22, 1972)........... 18,25,34, 35

United States v. Jacksonville Terminal Company,

451 F.2d 418 (5th Cir. 1971).................. 10,14,34

Utley V. Marks, ___ F.Supp. ___, 4 EPD 17552 (S.D.

Ga. 1971).................................... 28

Vogler v. McCarty, ____F.2d ___, 4 EPD 18781

(5th Cir. 1971) ............................. 23

Statutes and Regulations Page

EEOC Guidelines on Employee Selection Procedure, ‘29 C.F.R. §1607.1 (c)........................

29 C.F.R. §1607.5(a) ........................ 13

29 C.F.R. §1607.5(b)........................ 12

29 C.F.R. §1607.5(b) (1)...................... 12

29 C.F.R. §1607.5(b) (5)...................... 11

29 C.F.R. §1607.6 ........................ 16

Georgia Code Annotated, Title 3§3-704 ...................................... 27,28

§3-706 ...................................... 28

§3-711....................................... 28

§ 3 - 1 0 0 1 .................................... 28

Georgia Code Annotated, Title 109A .................... 27

National Labor Relations Act, 29 U.S.C. §187 .......... 22

National Labor Relations Act, 29 U.S.C. §160 (c)........ 24

Rule 54(c), Federal Rules of Civil Procedure ........ 19

Uniform Commercial Code............................... 27

Other Authorities

Cooper and Sobol, Seniority and Testing Under Fair

Employment Laws: A General Approach to Objective Criteria of Hiring and Promotion,

82 Harv. L. Rev. 1598 (1969) ............ 31

V -

IN THE

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE FIFTH CIRCUIT

No. 71 - 3447

UNITED STATES OF AMERICA,

Plaintif f-Appellant

and Cross-Appellee,

- vs -

GEORGIA POWER COMPANY, et al.,

Defendants-Appellees

and Cross-Appellants,

No. 71 - 3293

CHARLES KING, et al. , and WILLIE

MOREMAN,

Plaintiffs-Appellants,

- vs -

GEORGIA POWER COMPANY, et al . ,

Defendants-Appellees.

REPLY BRIEF FOR THE PRIVATE PLAINTIFFS-APPELLANTS

INTRODUCTION

The brief filed by the defendant Georgia Power Company

on March 17, 1972 responds to the issues presented by these

private plaintiffs and the United States, and raises two new

issues on cross-appeal. One of those issues, involving defend

ant's high school education requirement, was a crucial issue in

the private plaintiffs' cases below. Although Georgia Power has

formally cross-appealed only in the Attorney General's action,

we also deal in this reply brief with the high school education

requirement issue presented by Georgia Power's cross-appeal.

ARGUMENT

I .

THE DISTRICT COURT WAS CORRECT IN

RULING THAT THE COMPANY'S HIGH SCHOOL

EDUCATION REQUIREMENT WAS NEI’iHER

VALID AS A PREDICTOR OF JOB SUCCESS

NOR JUSTIFIABLE AS A BUSINESS NECESSITY

In 1960, the Georgia Power Company imposed a require

ment that all new hirees be high school graduates. This require

ment was applicable only prospectively; it was inapplicable to

incumbent employees. In 1964, however, the Company altered the

policy regarding incumbents and required that most employees

seeking to transfer out of the all-black Laborer, Janitor, Porter

and Maid classifications had to possess a hioh school diploma. At

approximately the same time, in 1964, the Company determined that

the high school diploma requirement would be waived for persons

hired into the Laborer classifications. These persons are re

quired to sign "waiver of employment standard" forms acknowledg

ing their understanding that they could not promote out of the

Laborer's classifications unless they acquireya high school

diploma.(Opinion at 17) The District Court properly struck

down this educational requirement, and Georgia Power has cross-

appealed that ruling.

The Georgia Power Company argues that so long as there

is a significant correlation between those qualities possessed

by a high school graduate and successful work performance, then

a high-school diploma requirement is a permissible hiring pre

requisite . (Company ' s brief, p. 27) This argument is deficient

as support for the high school diploma requirement in this case

in two respects. First, it confounds the necessity for pertinent

reading ability - which nobody contests - with a mere paper re

quirement which is at best clumsily and inexactly related to the

relevant reading skills. Second, as a matter of law, it fails

to recognize that there are other less discriminatory measures

than a diploma requirement for determining the requisite reading

ability. As the Court below properly concluded.

At best, the only justification for this re

quirement is the obvious eventual need for above-

average ability to read and comprehend the in

creasingly technical maintenance manuals, the

training bulletins, operating instructions, forms and the like demanded by the sophisticated in

dustry. . . In such a context, the nigh school

education requirement cannot be said to be rea

sonably related to job performance. This is not

to say that such qualifies are noc desirable --

the need is here in this Company's business; it sim.ply means that the "diploma test" cannot be

used to measure the qualities. Many high school

courses needed for a diploma (history, literature,

physical education, etc.) are not necessary for

these abilities. A new reading and comprehension

test . . . might legitimately be used for this

job need. However, for the reasons stated, the

high school education requirement cannot stand

and constitutes a practice used to discriminate

in violation of Title VII . (Opinion at 53-54)

The evidence submitted by all parties at trial demon

strates that some persons with high school diplomas are not

competent to perform all jobs in their line of progression and,

conversely, that many persons without diplomas are capable of

performing all jobs in their line. As noted above, the district

court found that the need to read a mass of highly technical

data was one which eventually arose in the higher job ranks.

(Opinion at 39) Thus starting from the assumption that many

jobs, particularly in the higher classifications, require

sophisticated reading skills, there is no evidence that only

high-school graduates are capable of mastering those skills.

Indeed, the Court below credited substantial evidence

that " . . . countless employees without the diploma have mastered

the need [to read] through self-study, through adult education

courses, and through perseverance and have advanced to the

highest technical levels in the Company." (Opinion at 53) The

Company's attempt to make light of the accomplishments of non-

high school graduates in the Atlanta and Macon operating divisions

ironically reveals the high achievements of those employees. As

Georgia Power acknowledges, the district court found that 28.4%

of white journeymen in those divisions do not have high school

diplomas. (Opinion at 37) Of the 788 employees, Negro and

white, in journeymen classifications in those operating divisions

plus the steam plants, 208 or 26.4% lack high school educations.

(Gov. Ex. 17 B and C) Additionfilly, in those same Atlanta and

- 4

Macon operating divisions evidence submitted at trial established

that 47 out of 100 foremen, supervisors and chief division

operators do not have high school diplomas. (Gov. Ex. 17 B and C)

Finally, six white Georgia Power employees testified that they had

held and advanced through a wide variety of ]obs, including

positions at the journeyman and supervisory levels, despite hav

ing only five to eight years of formal education. Each testified

that he was able to read and use the necessary manuals, and had

learned to do so in part through on-the-]ob experience and

personal study. (7 Tr. 52-79)

In the face of this undisputed evidence, the Company

argues blithely that it is ''irrelevant that some employees have

successfully performed without meeting the [high school] require

ment." (Company's brief, p. 45) We strongly demur: surely it

cannot be "irrelevant" that roughly one quarter to one half of the

highest jobs in the division chosen by the Company for scrutiny

here are held by persons who, were they now seeking jobs, could

not be hired at the helper level because they do not possess a

high school diploma.

Georgia Power relies heavily on data showing that non

graduates have recently obtained fewer promotions than graduates.

This purported proof is, of course, quite circular, since in light

of the Company's faith in the paper qualification, a diploma was

in all probability one of the passports to promotion. This would

seem to be the understanding of Georgia Power's head of Personnel

Relations, Mr. Joiner. (4 Tr. 217, 227-228) And in fact, the

district court found that possession of a high school diploma

did have a significant bearing on promotabi1ity at the Company,

but not for the reason stated by Mr. Joiner. Rather, the court

noted that several black non-diploma holders testified that they

were qualified for the type of work the Company required in higher

job classifications, but that the Company policy against promoting

non-graduates had prevented these employees from progressing out

of the laborer classification. (Opinion at 38)

Georgia Power has collected no data and made no study on

the relationship between possession of a high school education and

job performance. (Opinion at 38) At trial, however, the Company

introduced evidence purporting to demonstrate that a high school

graduate reading level was required to read certain Company

manuals, understanding of which was described as necessary to

successful job performance. The evidence consisted of testimony

by Dr. Harry Cowart, an expert in reading, who described his

application of the S.M.O.G. and Dale-Chall formulas to determine

the readability levels of the manuals. That evidence shows the

flaw in defendant's whole argument.

The S.M.O.G. readability level is derived from examining

any three pages of a given manual. The procedure used was des

cribed by Dr. Cowart as follows:

A: You count -- when you select the three

pages that you will use, select or take ten

sentences. . . On the basis of this, out of the

ten sentences, you simply count the number of

polysyllabic words that have more than three

syllables. Then you do the same thing for the

second and third sample, which would give you,

really, three sentences.

- b -

Then from that you would come up with a number of polysyllabic words in excess --

three or more. Then you take the nearest

perfect square of the number of polysyllabic

words and then you add to it 3 and you come

out with this figure here. (6 Tr. 183)

After adjustment of this raw score, the number arrived at sig

nifies what grade level reading skill on the S.M.O.G. scale is

required to read and understand the text sample.

The Dale-Chall formula is based, not on polysyllabic

words, but on unfamiliar words. It was explained as follows:

A: Tn 'the Dale-Chall Formula you take

into consideration two factors. First of all,

the number of unfamiliar words which is

established by taking a set of 3,000 words that

is printed on a familiar word list, and you

take the 100-word sample or over that, and you

check each word to determine whether it is on

the Dale-Chall familiar word list or not. If

it is not, it counts as an unfamiliar word. You come up with a number of unfamiliar words in

the selection chosen.

So working with . . . the number of un

familiar words, percent of the number of unknown words, and the sentence length, average

sentence length for the selection, you multiply average word length by the constant that is predetermined by the formula and average

sentence length by a constant, then you add to

that 3.6365 which is a constant which they came

to by using a regression equation, and you come

out with three scores like 9.0. You would take

the three of these sub-scores, add them to

gether and divide by 3, and you would come up

with an average readability for the book.(6 Tr. 187-188)

The two tests, therefore, do not measure literacy in

any general sense, but only knowledge of a specific unfamiliar

or polysyllabic vocabulary.

- 7 -

Georgia Power's reliance on these tests to justify its

educational requirement raises serious doubts as to the require

ment's rationality. By application of these formulas to the 29

manuals used in the Company, Dr. Cowart testified that l9 or 20

of them required college level reading skills. (Company's brief.

Appendix A) The implication is either that these manuals are

useful only in the most highly skilled ]obs in the Company or

that only persons with college level reading skills, not simply

high school graduates, are competent to handle the manuals.

Either explanation strains our belief. Furthermore, Dr. Cowart's

testimony makes it clear that in fact the S.M.O.G. and Dale-Chall

scores are only mean reading scores, so that only 50% of all

high school graduates could read at the high school graduate level

(which is the supposedly necessary level). (6 Tr. 191)

Dr. Cowart unwittingly put his finger on the heart of the

question during cross-examination. There, he conceded that per

sons working with special equipment and learning the vocabulary

of their jobs might score well above more highly educated persons

who were unfamiliar with the content of the job. (6 Tr. 196)

Similarly, when asked to explain how someone with a seventh grade

education could work for several years on a boiler-turbine using

a manual labelled as having college level readability. Dr.

Cowart noted that such an employee

Was highly motivated, he had a self-drive and

he was interested in doing it. I don't know who

you are talking about, but I realize that any

time there can be one exception to a general rule.

I talk in generalities; you talk in specifics.

- d

Q: Would the fact that someone might

be in a ]ob for eight years as an underling

or helper using the book or seeing the book

used every day make any difference in his

ability to comprehend its contents?

A: Surely. (6 Tr. 200)

It is obvious here that employees lacking extensive

schooling can nevertheless "pick up" the specific vocabulary

and reading skills necessary for higher level jobs in the Company

through diligence and job experience in the lower jobs of the

line. In these circumstances, Georgia Power's practice of shutting

out non-graduates at the entry level amounts to the erection of

a wholly artificial and unnecessary barrier to employment

opportunities.

Our complaint with the education requirement is not, of

course, that it is simply a crude and unnecessary criterion.

Rather, it is a racially-flawed criterion. The district court

found that "[s]ignificantly greater numbers of blacks than whites

do not have high school educations." (Opinion at 36) In Atlanta,

where a large part of the Company's hiring is done, white high

school graduates outnumber blacks at the rate of about 2 to 1. (Id.)

Where an employment screening device has a racial impact

as dramatic as Georgia Power's high school education requirement,

the business necessity test comes into play. Griggs v. Duke

Power Co., 401 U.S. 424, 4 U (1971). In that light, the Company's

failure to offer any serious evidence of business necessity for

the requirement is telling. The district court in fact held that

there was no such necessity for the requirement. (Opinion at 53)

- 9 -

In its correct decision on this point, the court's reason

ing closely followed that later adopted by this Court in United

States V . Jacksonville Terminal Company, 451 F.2d 418 (1971).

Under that decision's principles, it is not enough that the high

school diploma requirement might serve some legitimate manage

ment functions; it must be "essential."

"If the legitimate ends of safety and

efficiency can be served by the reasonably

available alternative system with less dis

criminatory effects, then the present policies

may not be continued."

(451 F.2d at 451, quoting United States v. Bethlehem Steel Corp

oration, 446 F.2d 652, 662 (2nd Cir. 1971). Consequently, the

burden of business necessity can only be met here by showing the

absence of any reasonable alternative. (Id.) In the instant case,

the court recognized that, if the desired skills can be discerned

without incorporating the discriminatory impact of the high

school graduation requirement, alternative means must be developed

for discovering employee capability. (Opinion at 54) The court

below suggested that reading te?sts be administered. Perhaps

other means will be suggested by the Company. As the district

court ruled, some alternative m<?asure must be found.

Inasmuch as the diploma requirement acts as a "built-

in headwind" against minority equal employment opportunity and

is not necessary to the safe and efficient operation of the

Company's business, the requirement was properly ruled imper

missible by the court below.

- 10 -

I r.

THE COMPANY’S ARGUMENTS IN SUPPORT OF ITS

TESTING PROGRAM IGNORE THE MAJOR POINTS

RAISED BY PLAINTIFFS AND OFFER NO ADEQUATEJUSTIFICATION FOR CONTINUATION OF THE PROGRAM1

The plaintiffs' main brief raised two rriajor points re

garding the Company's tests: (A) that the tests have not been

validated in conformity with EEOC guidelines, which should be

the applicable standard, and ( B ) that, in any event, the tests

bear no relationship to job performance as measured by any reason

able standard. On both points, the Company's brief simply avoids

the real issues.

A. The Company's Argument Regarding the Guidelines.

As to the EEOC guidelines, the Company apparently concedes

that it is not in conformity. Rather than claim conformity, the

Company attacks the guidelines with unwarranted accusations that

they are unreasonable. In every instance the claim of unreason

ableness is based on an assertion that the guidelines demand cer

tain specific standards of validation which in fact the guidelines

do not require.

First, the Company cla ins that "the E.EOC requires an em

ployer to make a study to determine whether differential validity

[separate validity for blacks and whites] e.xists". (Company's

brief, pp. 31-32) Georgia Power apparently believes this unrea

sonable because it will sometimes be practically impossible for an

employer to make such a determination. However, the fact is that

the guidelines contain no such absolute requirement. They require

differential validity data only "wherever technically feasible".

29 C.F.R. §1607.5 (b) (S) .

IL -

Second, the Company asserts that "the EEOC guidelines are

too strict and restrictive in that they " . . . are strongly

oriented toward the use of correlation coefficients as a technique

for establishing test validity." (Company's brief, p. 32) Georgia

Power apparently deems this unsound insofar as it would preclude

use of the discriminant function analysis preferred by the Company

as a validation technique. But in fact, "correlation coefficients"

are never even mentioned in the guidelines. Moreover, the guide

lines expressly state that "any appropriate validation strategy

may be used" provided it meets very general minimum standards.

29 C.F.R. §1607.5(b) Nothing in the guidelines precludes an

appropriate use of the discriminant function analysis relied upon

by the Company's expert, or any other reasonable technique.

Third, the Company asserts that the guidelines require an

employer to show "that persons who were hired on the basis of tests

do better on the job than persons who were rejected." (Company's

brief, p. 33) This, the Company says, is unreasonable because

it requires an employer to hire people ho would otherwise reject.

However, the fact is that the guidelines expressly permit an

employer to conduct the type of validity study "in which tests

are administered to present employees," 29 C.F.R. § 1607.5 (b) (1) .

Since such a study (a "concurrent validity study") is based on a

sample group of present employees, the employer is obviously not

required to hire any new persons for it.

The Company's attack on the guidelines is based on a

fundamental and erroneous legal premise, stated on p. 30 of its brief;

12 -

"It is submitted that the appellants and

the EEOC have the burden of proving that the

standards vdiich they would use in judging

these criteria [tests] are reasonable."

[3mphasis added]

This notion that an administrative agency has the burden of

justifying its guidelines is a perversion of the law. Well-

established legal principle entitles the agency's interpretations

to deference, and requires the attacker to carry the burden of

showing unreasonableness. (See Plaintiff's main brief, pp. 29-34J

The truth of the matter is that the EEOC guidelines pro

vide "a workable set of standards" 29 C.F.R. §1607.5 (a). The

Company's arguments are simply an attempt to create a nonexistent

monster by misstating the real requirements. The guidelines are

clearly reasonable on their face, and they are clearly reasonable

as applied to the Company's testing program. Admittedly, any

administrative rule or regulation could conceivably be applied un

reasonably if some parade of hypothetical horribles came to pass.

When that happens a court should step in to check the agency; but

it lias plainly not happened here and the Court should sustain the

guidelines as applied to defendant Georgia Power Company.

B. The Company's Argument Regarding the Relation

ship of Its Tests to Job Performance Proves Nothing.

As explained in plaintiffs' main brief (pp. 34-44), the

Company's validation effort proves nothing because it involves a

weighted formula use of tests which differs dramatically from the

Company's actual usage. The formula actually involves negative

weightings for many tests which would effectively give preference

io persons who score low on the test, exactly the opposite of the

- 1 t

actual practice. Moreover, even when weighted by these formulae

to produce maximum validity, the tests have no significant rela

tionship to job performance. The Company does not deny these

points, because they cannot be denied; rather the Company claims

that it should nonetheless be permitted to use its tests because

I I

there is "a den.onstrable relationship between rest scores and job

performance." (Company's brief, p. 58)

Georgia Power offers not a shred of explanation or just

ification for refusing to adopt the weighted formula approach used

and recommended by its own expert. The plaintiffs are not, con

trary to the Company's claim, critical of their expert for using

weighted formulae. Rather we are critical of Georgia Power for

persistently ignoring these formulae. The formula alternative

could be more favorable to blacks (although still largely dis

criminatory) , and in some cases could prefer them to whites.

Moreover, since it was recommended by the Company's own expert, it

is presumably superior front a professional testing viewpoint. (See

Plaintiffs' main brief, pp. 38-39) At the very minimum, the

Company's failure to adopt this alternative is naked violation of the

law because it is a rejection of a superior and less discriminatory

alternative. United States v. Jacksonville Terminal Co., supra, at

451; United States v. Bethlehem Steel Corp., supra, at 662; Robinson

V . Lorillard Corp., 444 F.2d 791, 798 (4th Cir. 1971).

However, this Court should not be misled into thinking that

the use of these weighted formulae would be acceptable. Even though

the formula approach is superior to present practices and maximizes

- 14

the predictive value of these tests, it still evidences no sig

nificant relationship between tests and job performance. The

Company claim,s that a "demonstrable relationship" exists (Company's

brief, p. 34), but a close examination shows how hollow that claim is,

A statistical evaluation of the relationships between test

scores and job performance, even when made pursuant to the Company's

preferred discriminant function technique, demonstrates that the

relationships are statistically insignificant. This statistical

point is documented in the exhibit at p. 42 of Plaintiffs' main brief,

The final column in that exhibit shows the actual level of con

fidence for the relationships between test scores and job per

formance obtained from the sample groups i.e . , the degree of con

fidence that the same relationships would result when the tests

were put into general use. Unless there is a. sufficient level of

confidence, no person can reasonably conclude that the original re

sults are more than chance. In the case of six jobs (apprentice

mechanics, appliance servicemen, storekeepers, metermen, helpers,

meter readers) it is approximately an even money bet that com

pletely different relationships would result, since there is be

tween a .40 and a .60 possibility of this. in the case of three

other jobs (lineman, miechanics, and clerical) there is a .25 (one

in four) possibility of different results. Good statistical

practice calls for at least the .05 level of confidence. (See

Plaintiffs' main brief, pp. 39-41.) This level of confidence is

achieved only for two ]obs, garage mechanics and winch truck

operators, and for one of those ]obs (garage mechanics) the tests

were rejected by the Company for other reasons. Whether judged

- 15

by the traditional .05 statistical standard, or even by a much

lower standard, the results shown in the Company's study are not

generally significant enough for any reasonable reliance to be

1 /

placed upon them.

Georgia Power attempts to excuse its insignificant results

on the ground that it had a small sample group with restricted

range. (Company's brief, pp. 35-36) However, acceptable statistical

practices are available to deal with these problems of limited

sample groups and such practices are acknowledged in the EEOC guide

lines, see 29 C.F.R. §1607.6. The Company's expert said he opted

for discriminant function analysis for the precise purpose of cop

ing with these problems. (See Opinion at 32; 6 Tr. 54-55, 128-129,

167-68.) Yet even after using mathematically weighted formulae

which artfully maximized the tests' predictive ability (see Co. Ex.

75, pp. 1, 4; 6 Tr. 82-83, 168; Plaintiffs' main brief, p. 37), and

applying discriminant function inalysis, the meager results dis

cussed above were the end product. The true significance of the

î/ The Company also asserts in its statement of facts that there

is a "positive correlation" between test scores and job performance

indicated by the data in Appendix C of its brief. (Company's brief, pp. 11-12) It is not clear whether or not this "positive corre

lation" is the "demonstrable relationship" referred to in the

Company's argument. In any event, these so-called positive corre

lations are meaningless.

The first point to note is that Appendix C was derived from the

Company's validity study (Co. Ex. 75) and is thus based on a com

parison of groups created by the weighted formulae which the Company steadfastly refused to adopt. But even ignoring that defect, a

casual examination of Appendix C. reveals, even to the nonstatis-

tically-minded observer, that test score differences between high

and low performance groups are insignificant. The differences are

- 16

'ir̂

Company's actual tost use is even more moaqo;r, since that usage

does not gain the maximizing effects of formula weighting. When

one also considers that the "validation" results are based on a

study that was technically deficient and took no account of possi

ble black-white differences in test performance (see Plaintiffs'

main brief, pp. 43-44), the value of the Georgia Power testing pro

gram pales into less than insignificance.

The facts show that the Company is not really interested

in a "demonstrable relationship" between test scores and job per

formance. For example, there is no explanation why, if any demon

strable relationship between test scores and job performance is

sufficient to justify test use, the tests should be rejected for

switchboard operator and garage mechanics. As to those jobs there

was a relationship between tests and jobs. However, that rela-

(Cont'd)1/ frequently negligible (e.g., for meter readers the average SET-V

score of low performers is 24.16 and for high performers it is

24.80), and in one instance there is a negative relationship rather

than a positive one (The average PTI-Verbal score of low rated

storekeepers is 33.31 and for high rated storekeepers it is 31.56).

Only in two instances (PTI-V scores for winch truck operators and

SET scores for clerical employees) is there any noticeable difference

in scores.

When score differences are so generally modest, a reasonable

person inquires how significant these differences are, particularly

when the differences are based on very small sample groups. But

even if those score differences were substantial the differences

would not be important unless they were meaningfully correlated with differences in job performance. These correlations, made under the

Company's preferred discriminant function technique, are insig

nificant, as discussed in the text above.

2/ Indeed in the case of garage mechanics it was among the most

Significant relationship of all because it bettered the .05 level

of confidence. (See Plaintiffs' main brief, p. 42).

- 17 -

tionship was largely negative -- poor test scorers, who happen to be

predominately black, seem to do better on the jobs. (See Co. Ex. 75,

unnumbered appendices.) This negative relationship was just as po

tentially useful to the Company as were test scores for other jobs,

yet it was rejected by the Company's expert. In other words when a

demonstrable relationship can be argued to support the Company's

practice -- and help whites -- it is advanced as a justification;

but when such a relationship suggests a different practice -- which

would help blacks -- it is ignored. In truth, none of these "demon

strable relationships" are worth the paper they are printed on as a

justification for the Georgia Power Company's test program. That

program should be enjoined

I I I .

DEFENDANT'S ARGUMENTS SUGGEST NO VALID REASON

TO DENY CLASS-WIDE BACK PAY OR TO LIMIT THE

INDIVIDUAL AWARDS OF BACK PAY

A. The Company's Procedural Smokescreens.

Georgia Power's brief (at p. 55) insinuates that the pri

vate plaintiffs made no claim for class back pay until after trial.

As a matter of fact, the plaintiffs' class-action complaints rather

clearly announce the back pay claim. Moreover, under any interpre

tation of the complaints, the defendant's position must be rejected

as a matter of law, as it has been both in this circuit. United

States V . Hayes International Corp. , F.2d , 4 EPD 117690 (5th

J7

Cir., Feb. 22, 1971); and elsewhere, Robinson v. Loriallard Corp.,

V This Court there held, "We think that the broad aims of Title

VII require that this issue [back pay] be developed and determined.

It should be fully considered on remand." In the case at bar, of

course, the issue has already been developed, determined and fully considered by the District Court, and that determination is before this Court now.

- IH

4/'supra, at 802; Rosen -v. Public Service Electric and Gas Co., 409

F.2d 774, 780 n.20 {3rc3 Clr. 196 9)- Sprogis v. United Air Lines.

Inc., 444 F.2d 1194, 1201 (7th Cir. 1971), cert, denied 4 EPD

f7588 (1971). Defendant argues, somewhat imaginatively, that the

alleged lateness of the private plaintiffs' class baclc pay claim

has prejudiced its defense. This contention is specious. As the

Fourth Circuit has held in rejecting an identical defense to

class back pay.

In our case, because the obligation to provide

back pay stems from the same source as the ob

ligation to reform the seniority system [here,

Georgia Power's testing and educational require

ment as well], any general defenses relevant to

the suit for injunctive relief. Any specific

defenses related only to the computation of back

pay may be raised during the process of assess

ing individual back pay claims, possibly before

a special master. The defendants have in no

way been' prejudiced by the belated claim.

Robinson v. Lorillard Corp., supra, at 80,3. The "prejudice" argu

ment is further undercut by the fact that defendant was confronted

with the Attorney General's cla.ss back pay claim, which includes

plaintiffs', in the consolidated pattern and practice action.

^ The Robinson decision even overcame an express "waiver"

of back pay. The Court relied principally on Rule 54(c), Fed.

R. Civ. P., which provides:

. . . every final jud<jment shall grant therelief to which the party in whose favor it

is rendered is entitled, even if the party has not demanded such relief in his pleadings.

The Fourth Circuit explicitly rejected defendants' reliance

on Rental Development Corporation of America v. Lavery, 304 F.2d

839 (9th Cir. 1962), which is Georgia Power's chief authority on this same point, 444 F.2d at 803.

- 19 -

Georgia Power also attempts to parry these plaintiffs'

thrust for class back pay on the ground that Rule 2 3(b) (2) actions

are not suitable vehicles for such a claim. The Fourth Circuit has

squarely refuted this reasoning in Robinson, and we can state the

matter no better than that Court:

There is nothing in Moore, in the

Advisory Committee's Note, or in any

case cited to us which supports the pro

position that no monetary relief may be

ordered in a class action under Rule 2 3(b) (2)

This is a case in which final injunc

tive relief is appropriate and the defend

ants' liability for back pay is rooted in

grounds applicable to all members of the

defined class. Under these circumstances,

the award of back pay, as one element of the

equitable remedy, conflicts in no way with

the limitations of Rule 23(b)(2).

444 F.2d at 802. This Court should so hold.

B. The Facts of This Case Demand Recognition of

the Class Members' Entitlement to Back Pay,

Notwithstanding Possible Difficulties in Computing the Exact Amounts Due.

The principal argument advanced by Georgia Power in oppo

sition to the class back pay claim is that allowance of the claim

would entail "impractical" judicial tasks. Proof of the claim

would in defendant's view become "unmanageable"; therefore the

claim cannot even be considered. This view is fundamentally mis

directed. It confuses the subordinate issues as to computation of

damages with the overriding issue of the availability of class

back pay in an appropriate Title VII action. The latter issue

alone is before this Court here. While this Court may obviously

- 20 -

be concerned here with questions surroundinq the methodology of

back pay computations, its specific duty is to decide the larger

question of the class members' entitlement to back pay, however

computed.

Defendant premises its argument on the assertion that no

proof of financial loss to class members as a result of racial dis

crimination was placed before the court below. This assertion is

contrary to the obvious facts, which were explicitly found by the

district court, showing that virtually all black employees earned

less than virtually all white employees because of their race. (See

pp. 12, 71-72 of plaintiffs' main brief.! This proof of damages

was anything but "speculative." In this light, defendant's argu

ment reduces to the proposition that, for any class member to be

entitled to any back pay, every element of that individual's em

ployment qualifications and history must be fully presented at

the initial trial.

The defendant's proposition holds no water as a matter of

logic or of law. Its adoption would utterly frustrate the purposes

of Rule 23 of the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure and would en

courage (or even compel) Title VII plaintiffs to adopt truly bur

densome and unmanageable trial strategies. And no less import

antly, that approach is at war with the strong policy favoring

effective Title VII renedies which will eradicate em.ployment dis

crimination from this land, and which this Court has repeatedly

endorsed.

6/ See, most recently, Rowe v. General Motors Corp.. 4 EPD^7715 (5th Cir., March 2, 1971). F.2d

1 -

(Georgia Power's position also contravenes a widely-

‘̂f^cepted principle of the law of clarnages. This Court has recognized

that principle and applied it in a context closely analogous to

that of the case at bar - a stcitutory damages action under the

NIjRA, 29 U.S.C. §187, where it held:

I The statute is compensatory in nature [citations

omitted], and damages may only be recovered for actual losses sustained as a result of the un

lawful secondary acti^^ity. While the employer

must prove that he has sustained some injury to

business or property, he need not detail the

exact amount of damages suffered. it is suffi

cient that the evidence supports a just and reasonable determination.

Sheet Metal Workers Int'1 Ass'n, Local 223 v. Atlas Sheet Metal Co

384 F 2d 101, 109 (5th Cir . 1967) . This holding is merely an

application of the established rule that.

The rule which precludes the recovery of un

certain damages applies to such as are not the

certain result of the wrong, not to those

damages which are definitely attributable to

the wrong and only uncertain in respect of their amount, [citation omotted]

Story Parchment Co. v. Paterson Co., 282 U.s. 555, 562 (1931). The

rationale for this rule has been clearly enunciated by the Supreme

Court:

Where the tort itself is of such a

nature as to preclude the ascertainment of the amount of damages with certainty,

it would be a perversion of fundamental

principles of justice to deny all relief

to the injured person, and thereby re

lieve the wrongdoer from making any amend for his acts. Î . at 563.

This rationale is of course particularly applicable to the David-

and-Goliath situation presented by the typical Title VII class

action, cf. Jenkins v. United Gas Corp., 400 F.2d 28, 33 (5th Cir.

1969), such as the instant matter. See, also, A & Z Rental, Inc, v .

- 22 -

y

Wilson, 413 F.2d 889, 908 (10th Cir. 1969): Burns Bros. Plumbers.

Inc. V . Groves Ventures Co.. 412 F.2d 202, 209 (6th Cir. 1969);

Mason-Rust v. Laborer's Int'1 Union, Local 42, 435 F.2d 939,

945-946 (8th Cir. 1970).

The question of methods is therefore legitimate but not dis

positive. Relying on Syres v. Oil Workers International Union.

257 F.2d 479 (5th Cir. 1958), cert, denied 358 U.S. 929 (1958),

defendant strongly attacks the averaging method proposed by the

private plaintiffs below. We submit that some form of "averaging"

might indeed be appropriate in the present matter, cf. Eisen v.

Carlisle & Jacquelin. 52 F.R.D. 253, 261-262 (S.D.N.Y. 1971) But

in any event, the district court could not deny the underlying en

titlement of the class to back pay solely because it rejected the

y"averaging" method. Rather, it was the court's duty to fashion an

appropriate method for determining the precise remedy required by

Title VII; the complexity or difficulty of that determination can

not excuse the court from exercising its proper remedial function.

Long V . Georgia Kraft Co., 450 F.2d 557, 561-562 (5th Cir. 1971). 9/

IJ Wo would question the cont inuinq vitality of Syres, a pre-Title

Vll case, in the present context.. That case involved the propriety

of a 3ury c:harge in a jury-tried damages action under the duty of

fair representation. The equitable class action aspects of the suit

had been dismissed, and plaintiffs had not appealed this ruling.

8̂ / In fact, the court below gave no indication that it rejected the averaging method. Its denial of back pay was founded on the holding

that, as a matter of law. Title VII did not allow an awai'd of damages

to persons who were not named plaintiffs and EEOC charging parties. (Opinion at 56)

See also, Voqler v. McCarty, F .2d , 4 EPD f 7581 (5thCir. 1971); Local 53, Asbestos Workers v. Voqler, 407 F.2d 1047,

1052-1053 (5th Cir. 1969); Rule 54(c), Fc'deral Rules of Civil Pro

cedure; Sproqis v. United Air Lines, Inc, supra, at 1201.

- 23

Plaintiff o'/erwhe In'1 na proof of cltiss-wide discrimina

tion anci class-wide f inaru'ial Lcs:-; h.c-; ;;hift.i'i| t.hr- burdtm of qoing

forward with respect to the computation of individual back pay-

entitlements. The proper proce^dure for the district court would be

to allow class members an amount calculated on the basis of the

class-wide consequences of the class-wid'c d i scr imina t ion , subject

to any evidence the defendant might introduce to justify a lesser

award in any particular instance. This procedure would be in

keeping with the methods routinely applied by chis and other appellate

courts in determining back pay awards under the National Labor

Relations Act, 29 U.S.C. §160 (c) . In that setting,

The Board, in a backpay proceeding, has

the sole burden of proving employer liability

for unlawful discrimination, with the Employer

ha ving the burden of coming forward with facts

in mitigation. . . .

Trinity Valley Iron & Steel Co. N.L.R.B., 410 F.2d 1161, 1168

(5th Cir. 1969). Accord, N.L.R.B v. Miami Coca-Cola Bottling Co.,

360 F.2d 569, 575-576 (5th Cir. 1966): N.L.R.B. v. Robert Haws

Company, 403 F.2d 979, 981 (6th Cir. 1970): N.L.R.B. v. Reynolds,

1^'399 F.2d 668, 669 (6th Cirl 1970': N.L.R.B. v. Carpenters Union,

Local 180, 433 F.2d 9<4, 935 '9th Cir. 1970).

The district court's allowance of back pay should be in

accordance with standards and methods formulated by the court, or

by the parties and approved by the court. Or.ce these standards have

10/ The Sixth Circuit there wrcjte, "It is the rule that where the

issue before the Board is the amount of an employer's liability

arising out of its unfair labor practices, the burden is upon the

employer to show that there is no liability, or that such liability

should be mitigated. The finding of an unfair labor practice is

presumptive proof that some back pay is owed."

- 24

been established, their application is clearly feasible in

individual cases. If the court envisions an excessive burden in

such matters, the appointment of a special master under Rule 53(a),

Fed. R. Civ. P., may conserve judicial time and provide technical

expertise. See United States v. Hayes International Corp., supra;

Robinson v. Lorillard Corp., 319 F.Supp. 835, 843 (W.D.N.C. 1970),

aff'd on this point 444 F.2d at 802 n.l4 i4th Cir. 1971).

This Court has recognized that, upon appropriate proof,

class back pay is a suitable Title VII remedy. United States v.

Hayes International Corp., supra. On the extensive record already

compiled below, and in light of the overwhelming proof of discrim

ination and resultant economic injury, class back pay is required

here .

C. The Conlpariy's Opposition to Increased Individual

Awards Is Premised on Purely Hypothetical and

Erroneous Factual Assemptions.

Plaintiffs also seek increased individual back pay awards

which more adequately reflect their actual economic loss due to

discrimination. Georgia Power's arguments against such awards are

unconvincing. Its emphasis on the requirement of individual proof

based on individual qualifications is misplaced at this stage.

Georgia Power's denial of promotion to the recovering plaintiffs

was not based on any assessment of their individual qualifications.

11/ For example, the district court set forth standards to be used

in computing the back pay entitlement of fiv'e of the named plaintiffs

(Private decree at 3-4). On this basis, the parties were able to

compute and agree on the specific amounts involved with dispatch -

subject, of course, to plaintiffs' appeal contesting the adequacy

of the court's standards.

- 25

buL only on their race. Therefore, at this stage of declaring

entitlement (as opposed to computing the actual loss), the relief

should be plenary, subject only to such evidence in mitigation of

the claims as Georgia Power may be able to produce at a later

proceeding. See, e.g., pp. 22 - 24 , infra, and cases there cited.

The comparisons drawn by Georgia Power (Brief at pp. 58-60)

are irrelevant and misleading. The juxtaposition of plaintiffs'

12_/

"prior work experience" with that of whites, dating from the 1940s

and 1950s, proves little more than the blatantly discriminatory

structure of job opportunities existing at that time. The fact

that certain white employees took a number of years to obtain sub

sequent promotions is not necessarily attributaole to any lack of

aptitude or qualifications. Rather, as the defendant elsewhere

points out (Company's brief, p. 7), job progression went much more

slowly in those days than n',w, due to the expanding workforce of

the present time.

Most fundamentally, Georgia Power's argument, based on the

assunption that plaintiffs would only have advanced one notch anyway,

flies in the face of the Court's finding indicating the contrary.

"Employees hired by the Georgia Power Company normally progress

within a reasonable time to the journeyman level classification."

(Opinion at 34; see also Opinion at 53.) Absent discrimination,that

time would have long ago arrived for the recovering plaintiffs.

Unless Georgia Power can show by affirmative proof - and not merely.

12/ Much of those whites' "experience" would seem to us to be

wholly irrelevant to work in the electric power industry.

26

on its part, rank speculation" - that plaintiffs would not have

risen beyond the first non-laborer level, the Company should com-

, . 13/pensate plaintiffs to the full extent of their injury.—

IV.

THE APPLICABLE STATE STATOTE OF LIMITATIONS IS NOT THE PROVISION ADVANCED BY DEFENDANT

The private plaintiffs and Georqia Power are in agreement

in principle in defining the statute of limitations issue. Both of

these parties urge that Title VII requires reference over to the

applicable state law. Moreover, we agree that in reviewing the

District Court's decision, "the question which must be decided is

whether a suit for back pay pursuant to Title VII is one accruing

under a law respecting the payment of wages" (Company's brief d

14/ '

69, cf. Ga. Code Ann. §3-704). We differ from Georgia Power in

answering that question in the negative, and urging this Court to

look elsewhere for the proper statutory analogue. The language

Boudreaux v._Baton Rouge Marine Contracting Corp.. 437 F.2d 1011,

1017 n. 16 (5th Cir. 1971), on which Georgia Power relies heavily.

i_3/ If plaintiffs had suffered purely commercial injury on a

contract, their claim would of course benefit from the liberal

remedial thrust of Uniform Commercial Code provisions. See e.q. U.C.C. Section 1-106(1) and Comment 1 thereto, and Section

■ (The U.C.C. has been adopted in Georgia Ga code Ann. Title 109A,) It would be ironic if their far more'

odious racially caused injury were remedied under any less liberal standards. ^

j^/ In rejecting the district -ourt's suggestion that Title VII's ninety-day filing period might apply here, Georgia Power's

position in Its brief (p. 71) would appear to be in accord with

plaintiffs . We welcome the defendant's sub silentio concurrence with our argument that such a result would be indefensible.

- 27 -

is not persuasive here. That language was of course only dictum

11/in a footnote, and is directed only to a §1981 claim.

16/Because the language of the twenty-year clause of §3-704

most nearly describes the nature of the back pay claim, and be

cause the liberal purposes of the Civil Rights Act command selec

tion of a statute which will provide an effective Title VII remedy,

we propose adoption here of the twenty-year period prescribed in

11/§3-704. (See main brief, pp. 86-89.) Of course, as a practical

matter recovery in the present case is cut off as of July 2, 1965,

Title VII's effective date.

15/ International Union v. Hoosier Cardinal Corp., 383 U.S. 696

(1966), on which Georgia Power relies, is also not on point. That

case's attentiveness to the statutory purpose of expediting the

disposition of labor disputes was expressed in the context of a

determination that an action filed seven years after the disputed

event was untimely. (A six years' delay would apparently have

been permissible.) The limitations issue here refers not to the

timeliness of filing, but only to the extent of the available relief,

16/ " . . . All suits for the enforcement of rights accruing toindividuals under statutes. . . or by operation of law. . . "

1 7/ In the interests of completeness, we would also call the

Court's attention to other pertinent Georgia Statutes. These

include Ga. Code Ann. §3-706 for breach of a contract not in writing (four years; text at Company's brief, p. 70); §3-711 for

contract actions not otherwise provided for (four years; the text

reads: "All other actions upon contracts, expressed or implied,

not hereinbefore provided for, shall be brought within four years

from the accrual of the right of action"); and §3-1003 for re

covery of personal property (four years; the text reads: "All suits for the recovery of personal property, or for damages for the

conversion or destruction of the same, shall be brought within

four years after the right of action accrues and not after.") This

latter provision was followed by one district court in Georgia in

ruling on the applicable limitations period for a §1981 claim,

Utley V. Marks, 4 EPD f7552 (S.D. Ga. 1971).

t I

28 -

V .

THE DISTRICT COURT FAILED TO GRANT ADEQUATE SENIORITY RELIEF TO DISCRIMINATEES

A. As to Pre-July 1063 Hirees

We welcome the apparent acquiscence of Georgia Power in our

contentions as to the proper seniority remedies for these classes

1of victims of discrimination. (See Company's brief, pp. 42-44.)

All parties agree that the terms of the district court's

decree govern over inconsistent statements in its opinion. Since

the opinion will, however, presumably be published, its effect may

be misunderstood by other courts or attorneys who might rely upon

it in believint^ that clear I y inadequate remedies were held to be

aifficient. We therefore urge this Court to include in its opinion

appropriate language to prevent any such misunderstanding.

The same considerations apply to those aspects of the decree

of the court below wl.ich appear ambiguous, as specified at p. 60 of

our main brief. We are pleased that Georgia Power has construed

these provisions in such fashion as to remove any lingering uncer

tainties as to the scope of relief (see Company's brief, pp. 43-44,

A14-A16), but here again we respectfully request that this Court make

clear in its opinion the breadth of the relief accorded.

B. As to Post-July 106̂ ' Hirees

Here again, Georgia Power has made no reply to our conten

tions as to the several respects in which the court below failed to

provide these employees with an adequate remedy. For the reasons

set forth in pp. 61-64 of our main brief, we respectfully urge that

appropriate company seniority be awarded to these employees as well.

- , J 9 -

RofuLrrto^^Hiro"' Victims of Discriminatory

As pointed out on pp. of our mam brief, the court be

low found that after the effective date of Title VII (July 2, 1965)

Georgia Power continued to discriminate against a large number of

black applicants for employment. while the court provided a proce

dure for permitting them to reapply, it did not accord them the

seniority they would have had absent the discrimination.

Georgia Power contends (p. 24 of its brief) that such

seniority

would appear to be in direct conflict with the deci-

sion of this Court in Local 189, United Panf̂ rm;,Vo>-o

and Paperwqrkers v. U.S., 4l^F.2d 980 (5th Cir 1969)

It argues that such relief "could be ordered only by adoption of the

■freedom now’ theory which was rejected by this Court in Local 189."

Georgia Power misreads what this Court said in Local 189.

in two respects.

First of all, the "freedom now" theory would require firing of

white employees to make places for black victims of discriminatory

refusals to hire. 416 F.2d at 988. But we are not asking that any

whites be displaced, or contending that their continued employment

is illegal; we only seek on behalf of those victims of unlawful dis

crimination in hiring who are now permitted to re-apply and are em

ployed, the seniority they would have had if they had not been dis

criminated against in the first place. This is consistent with the

"rightful place" theory sustained by this Court in Local 189.

Secondly, the limitations on seniority relief for victims

of refusals to hire, found in the legislative history of Title VII

- 3 0 -

and in the Local 189 opinion, refer to cases in which the dis

crimination occurred before July 2, 196S. As stated at 416 F.2d

994, "A Negro who had been rejected by an employer on racial grounds

before passage of the Act could not, after being hired, claim to

outranh whites who had been hired before him but after his original

rejection . . . (emphasis supplied). See also the Court's ob

jections to "requiring employers to correct their pre-Act discrim

ination by creating fictional seniority for nev/ Negro employees"

(emphasis supplied), at 416 F.2d 995. What we are concerned with

here however, is discrimination in hirimj that occurred after July

2, 1965 and was unlawful when it was inflicted. The victims of this

form of illegal conduct cannot be accorded their "rightful place"

unless they are given company seniority dating back to the dates on

which they applied. As stated in Cooper and Sobol, Seniority and

Testing under Fair Employment Laws: A General Approach to Objective

Criteria of Hiring and Promotion, 82 Harv. L. Rev. 1598, 1604 (1969)

[Ijf a black worker wlio applied for a job and was

turned down for racial reasons finally gest a job at such a plant, a seniority system which puts him at the bottom perpetuates the effects of his prior

exclusion.

The same comment applies to a seniority "remedy" which leaves the

18/

discriminatee at the bottom. See also Id. at 1633-1635.

18/ Interestingly, in the case of George Jones v. Georgia Power

Company, Civil No. 14182, tried together with the instant cases

but not appealed, the plaintiff, who the court below found had

been the victim of a discriminatory refusal to hire, was

specifically awarded company seniority. (Opinion at 61-63)

31 -

Appropriate remedies must be fashioned to alleviate the

consequences of past discrimination. This principle applies with

special strength where the past discrimination was itself illegal.

Failure to accord its victims the seniority they would have had

if Georgia Power had treated them in accordance with its legal

duty would be to renew and perpetuate in the future the conse

quences of that illegal conduct.

VI .

THE COMPANY'S BRIEF OFFERS NO RFĴ SONS OR FACTS SUFFICIENT TO DISPEL THE INFERENCE

OF DISCRIMINATION IN INITIAL ASSIGNMENTS

Georgia Power's brief on assignment practices since 1953

attempts to bury the stark facts of discrimination in a deluge of

artfully phrased statistics. (Company's brief at pp. 14-17) No

where in this mass of assertions does Georgia Power deny the truth

of the cardinal fact which plaintiffs documented in their principal

breif: until June 9, 1969, (’.eorgia Power had never made an initial

assignment of a black hiree to a non-laborer job. At the same time,

the large majority - over 80%-of whites hirees were assigned

to the better jobs.

In an attempt to rebut the inference of this stark racial

dichotomy, Georgia Power advances several asserted facts and argu

ments. Each of them misses the point and fails to dispel the in

ference. First, Georgia Power indicates that, by January 16, 1970 -

nearly two years after suit was filed - a number of blacks had

(finally) been non-discriminatorLly assigned. It goes on to discuss

initial assignemnts in 1970. The Company's very first efforts to

moderate its discriminatory assignment policies therefore occurred

- 3 2 ’ -

only in the latter half of 1969 and in 1970, with trial impending.

This Court has recognized that such tardy and dubiously "voluntary"

efforts are no substitute for a finding of discrimination and in

junctive relief. Rowe v. General Motors Corp., supra, at p. 5709.

Second, Georgia Power asserts that by January, 1971 all black

employees who qualified under its standards held non-laborer jobs.

This argument suffers from the same infirmity dealt with in Rowe,

supra. Furthermore, it attempts to elevate the Company's belated

promotion of qualified laborers into a defense to claims regarding

their initial assignment to ]obs beneath their qualification, on a

strictly racial basis. If anything, the fact of some blacks' subse

quent promotion only fortifies the plaintiffs' arguments; by promot

ing these laborers prior to trial, Georgia Power in effect admits

that they were qualified to hold non-laborer jobs.

Finally, Georgia Power tries to iustify these strongly sus

pect assignment patterns by reference to the racial patterns of

applicant flow to operating and production divisions. These patterns,

we submit, are both the product and proof of defendant's discrim

inatory recruitm.ent system fsee p. 55, in fra 1 . It would be ironic

indeed if one form of iiscrirunation wore allowed to justify yet

another.

To sustain Georgia Power's position., this Court would have

to accept its premise that assignments "have been dictated by appli

cants' qualifications and lob '.-acancies at the time of application"

(Company's brief, p. 39). On the facts in this record, this is

tantamount to finding that, until Juno 9, 1969, no qualified black

person ever applied for a non-laborer job when a vacancy was avail

able, while in the same period literally hundreds of whites applied

who were qualified and who found vacancies available. This in

ference, advanced by Georgia Power, cannot be upheld on the record,

and indeed is scarcely credible in light of the history and per

vasiveness of Georgia Power’s racially discriminatory practices.

The Company has simply not met its burden of specifically explain

ing the apparent discrimination. Cf. United States v. Hayes

International Corp., supra, at p. 5716.

Georgia Power relies, of course, upon this Court's dispo

sition of the initial assignment issue in United States v. Jackson

ville Terminal Co., supra. That case is inapposite here. This

Court there noted.

In this respect [assignments] it is important

to recognize that ]ob opportunities in the

railroad industry, and at this facility, have

not been abundant in recent years. Indeed,

total employment has declined. Consequently

workers furloughed or laid off from jobs at

one railroad-oriented facility would naturally

apply for identical or similar jobs at other facilities. . . Thus, at any given time, theremay be more experienced railroad workers search

ing for ;]obs in the industry than there are job openings.

451 F.2d at 444. After finding that the Company's hiring officers

had in fact been hiring such incustry-experienced applicants for

traditionally white jobs, the Court continued with a comment part

icularly apt in the present situation:

All of the persons so hired were white. In a

stable or expanding industry, this fact would

be damning, especially in regard to unskilled

or semi-skilled positions. Nevertheless, in

the railroad industry, therê is a plausible racially neutral explanation. . . [emphasis

supplied]

451 F.2d at 445. Georgia Power Company is the antithesis of the

Jacksonville Terminal in terms cf its expandinc^ workforce and the

4̂

changing nature of its jobs. {Sc'c, e.(j.. Company's brief, pp. 5, 7 )

perfectly the hypothot i.cal situation described as "damning"

by thxs Court in the last-quoted passage. Indeed, the foregoing

dicta would, if adopted hero as the Court's holding, seem to

dispose of defendant's argument.s upon the very authority on

which it relies.

VII.

THE GEORGIA POWER RECRUITMENT SYSTEM

HAS AN UNLAWFUL CHANNELLING EFFECT

Georgia Power's argument on recruitment attempts to press

the instant case into the mold of United States v. Hayes Interna

tional Corp., supra. This effort mistakes the thrust of our con

tentions. We do not contend that Georgia Power's recruitment system

produces an inadequate overall flow of black applicants. Rather,

our point is that the nature of the Company's recruitment system

channels black applicants into black jobs, and diverts black

applicants from "white" opportunities.

The statistics put forward in Georgia Power's brief on

initial assignments strongly but tres.ses our position on recruitment.

There, Georgia Power admits that the vast majority of black appli

cations were for the traditionally black production plant jobs, while

most whites applied to the operating divisions (Company's brief, pp.

14-17). This is precisely the point plaintiffs wi?h to make. The

racial difference in applicant flow at the various divisions, which

is a function of the Company's recruiting method, mirrors and per

petuates the racial differences in work force composition resulting

from Georgia Power's past practices of overt discrimination. In

carrying out its duty to extirpate the effects of past discrimina

tion, Rowe V . General Motors Corp., supra, at pp. 5705-5706, this

Court should order modification of the Company's present recruit-

ment system.

VIII.

THE COMPANY’S COUNSEL FEES ARGUMENT ASSUMES

FACTS WHICH ARE UNTRUE

Georgia Power's brief on the counsel fees issue inserts

several erroneous or misleading "factual" considerations into the

question. As a matter of plain arithmetic, its calculation (at

p. 73) that Mr. Rindskopf was entitled to only $3,350 at the

minimum fee schedule is incorrect by a matter of $2,000. Defendant

also emphasizes that the government shouldered the principal bur

den below, which is obviously true. But we reiterate that

plaintiffs seek compensation only for the work they actually did

and for time actually spent, not for the Attorney General's more

considerable efforts. For a period of nearly a year, moreover, the

private plaintiffs were alone in the field against Georgia Power,

and for many months following the Attorney General's intervention,

prior to consolidation, were on their own in their separate cases.

Contrary to the implications of Georgia Power's brief, the plain

tiffs are not asking to be paid for taking a free ride on the

Attorney General's back.

- 36 -

CONCLUSION

WHEREFORE, the private plaintiffs pray that this Court

affirm the district court's decision enjoining Georgia Power's

use of a high school education requirement, and in all other

respects sustain the plaintiffs' positions as set forth in the

rconclusion to their principal brief.

Respectfully submitted.

ALBERT J. ROSENTHAL

GEORGE COOPER

HARRIETT RABB

435 West 116th Street

New York, N.Y. 10027

Of Counsel

HOWARD MOORE

ELIZABETH R. RINDSKOPF

75 Piedmont Avenue, N.E. Suite 1154

Atlanta, Georgia 3030i

ISABEL GATES WEBSTER

75 Piedmont Avenue, N.E. Suite 1170

Atlanta, Georgia 30303

JACK GREENBERG WILLIAM L. ROBINSON

MORRIS J. BALLER

10 Columbus Circle Suite 2030

New York, New York 10019

Attorneys for the Private Plaintiffs- Appellants

CERTIFICATE OF SERVICE

The undersigned counsel for plaintiffs-appellants King,

Moreman, et al. hereby certifies that on the 10 day of April, 1972,

]ie served copies of the foregoing Reply Brief for Private Plaintiffs-

Appellants upon counsel of record for the other parties as listed

helow, by placing said copies in the United States mail, airmail

i

l^ostage prepaid.

J. Lewis Sapp., Esq.

1900 Peachtree Center Building 230 Peachtree Street, N.W.

Atlanta, Georgia 30303

Robert L. Mitchell, Esq.

1841 First National Bank Building Atlanta, Georgia 30303

Stephen Glassman, Esq.

United States Department of Justice Civil Rights Division

Washington, D.C. 20530

David Blasband, Esq.,

Linden & Deutsch

110 East 59th Street New York, New York

Lutz A. Prager

General Counsel's Office

EEOC1800 G St reet, N.W.

Washington, D.C. 20506