Correspondence from Stein to Judge Howard

Correspondence

July 11, 1996

2 pages

Cite this item

-

Case Files, Cromartie Hardbacks. Correspondence from Stein to Judge Howard, 1996. ba71b5eb-db0e-f011-9989-7c1e5267c7b6. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/34ebd9b1-cdf9-4dc5-b3e2-3bf76adae9b4/correspondence-from-stein-to-judge-howard. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

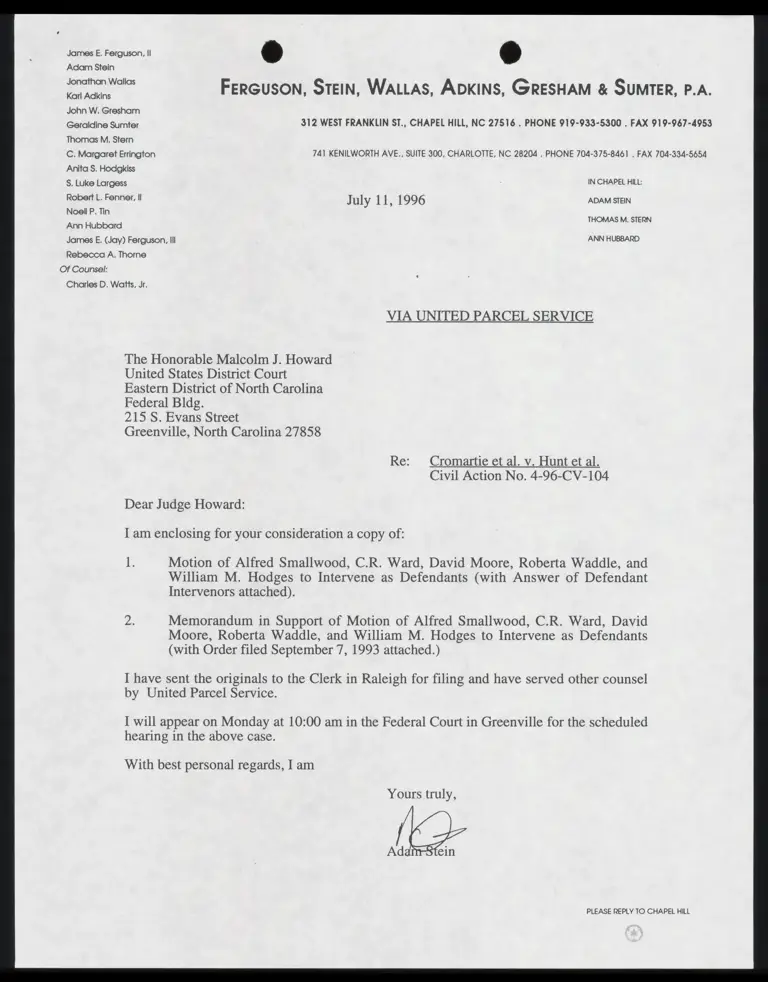

James E. Ferguson, lI El Ee

FERGUSON, STEIN, WALLAS, ADKINS, GRESHAM & SUMTER, P.A.

Adam Stein

Jonathan Wallas

Karl Adkins

John W. Gresham

Geraldine Sumter 312 WEST FRANKLIN ST., CHAPEL HILL, NC 27516 . PHONE 919-933-5300 . FAX 919-967-4953

Thomas M. Stern

C. Margaret Errington 741 KENILWORTH AVE., SUITE 300, CHARLOTTE, NC 28204 . PHONE 704-375-8461 . FAX 704-334-5654

Anita S. Hodgkiss

S. Luke Largess : IN CHAPEL HILL:

Robert L. Fenner, lI July 1 1, 1996 ADAM STEIN

Noell P. Tin

Ann Hubbard

James E. (Jay) Ferguson, lll ANN HUBBARD

Rebecca A. Thorne

Of Counsel:

Charles D. Watts, Jr.

THOMAS M. STERN

VIA UNITED PARCEL SERVICE

The Honorable Malcolm J. Howard

United States District Court

Eastern District of North Carolina

Federal Bldg.

215 S. Evans Street

Greenville, North Carolina 27858

Re: Cromartie et al. v. Hunt et al.

Civil Action No. 4-96-CV-104

Dear Judge Howard:

I am enclosing for your consideration a copy of:

1. Motion of Alfred Smallwood, C.R. Ward, David Moore, Roberta Waddle, and

William M. Hodges to Intervene as Defendants (with Answer of Defendant

Intervenors attached).

Memorandum in Support of Motion of Alfred Smallwood, C.R. Ward, David

Moore, Roberta Waddle, and William M. Hodges to Intervene as Defendants

(with Order filed September 7, 1993 attached.)

I have sent the originals to the Clerk in Raleigh for filing and have served other counsel

by United Parcel Service.

I will appear on Monday at 10:00 am in the Federal Court in Greenville for the scheduled

hearing in the above case.

With best personal regards, I am

Yours truly,

PLEASE REPLY TO CHAPEL HILL

The Honorable Malcolm J. Holl)

July 11, 1996

Page 2

AS:fm

enclosures

ce: Mr. Robinson O. Everett (via UPS)

Mr. Edwin M. Speas, Jr. (via UPS)

Ms. Anita S. Hodgkiss

Mr. Norman J. Chachkin