Local 28, Sheet Metal Workers v. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission Brief of Respondent

Public Court Documents

October 7, 1985

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Local 28, Sheet Metal Workers v. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission Brief of Respondent, 1985. 67994161-bb9a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/34f6b10e-c01a-4890-8c76-486663b167cf/local-28-sheet-metal-workers-v-equal-employment-opportunity-commission-brief-of-respondent. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

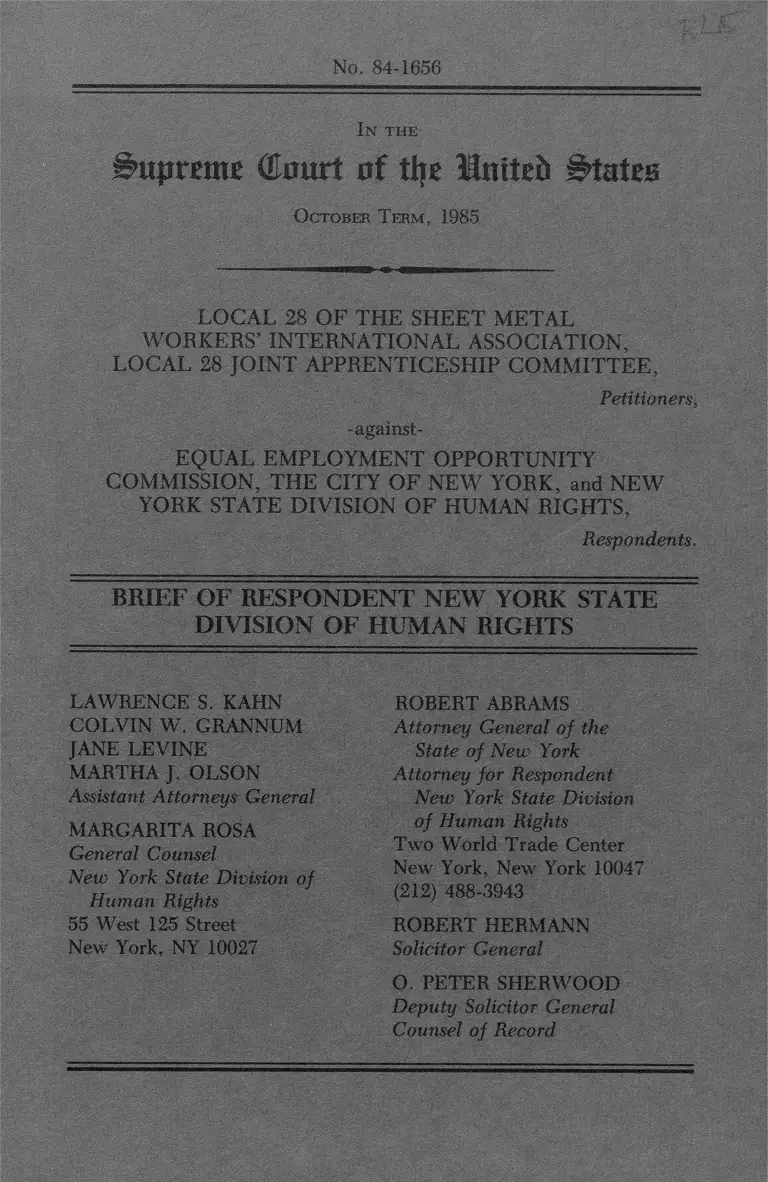

No. 84-1656

I n the

Supreme (Enurt of tije Mnitcfc States

October T erm , 1985

L O C A L 28 O F T H E S H E E T M E T A L

W O R K E R S ’ IN TER N A TIO N A L A SSO C IA TIO N ,

L O C A L 28 JO IN T A PP R E N T IC E SH IP C O M M IT T E E ,

• Petitioners,

-against-

EQ U A L E M P L O Y M E N T O P PO R TU N ITY

C O M M ISSIO N , T H E C IT Y O F N E W Y O R K , and N EW

YO RK ST A T E D IV ISIO N O F HUMAN R IG H T S,

Respondents.

BRIEF OF RESPONDENT NEW YORK STATE

DIVISION OF HUMAN RIGHTS

LAWRENCE S. KAHN

COLVIN W. GRANNUM

JANE LEVINE

MARTHA J. OLSON

Assistant Attorneys G eneral

MARGARITA ROSA

G eneral Counsel

New York State Division o f

Human Rights

55 West 125 Street

New York, NY 10027

ROBERT ABRAMS

Attorney G eneral o f the

State o f New York

Attorney fo r Respondent

New York State Division

o f Human Rights

Two World Trade Center

New York, New York 10047

(212) 488-3943

ROBERT HERMANN

Solicitor G eneral

O. PETER SHERWOOD

Deputy Solicitor G eneral

Counsel o f R ecord

QUESTIONS PRESENTED

1. Are challenges in this Court to rulings made a decade ago in

this action now barred?

2. May a party held in contempt for violating an injunction, avoid

sanctions on the basis of a claim that the sanctions are not

authorized by the statute on which the underlying injunction was

based?

3. Assuming the Court concludes that questions concerning the

scope of Title VII remedies should be addressed, does Title VII

of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 require that a court’s remedial

order, entered after a finding of consistent and egregious racial

discrimination, always be so narrowly drawn as to preclude gran

ting prospective race-conscious relief benefiting individuals who

have not been specifically identified as the victims of the defen

dant’s unlawful discrimination?

4. Does the fifth amendment bar a court from enforcing its

remedial orders by imposing civil contempt sanctions containing

race-conscious provisions which benefit persons who are not

necessarily the identified victims of unlawful discrimination?

5. Assuming the Court concludes that rulings made ten years ago

are still open for review: Did the district court properly conclude

(a) that petitioners had violated Title VII of the Civil Rights Act

of 1964 and (b) that the court had authority to appoint an ad

ministrator to oversee the day-to-day implementation of that

court’s remedial orders?

11

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Questions Presented ......................................................... i

Statement of the Case ........... 1

I. Preliminary Statem ent........................................... 1

II. Proceedings Against Local 28 Prior to this

Federal Court A ction............................................. 2

III. Federal Court Proceedings Prior to the

Contempt M otion................................................... 4

A. Judge Gurfein’s Consent O rd ers.................. 4

B. Liability D eterm ination.................................. 5

C. The First Appeal (1976).................................. 6

D. Entry of RAAPO............................................... 7

E. The Second Appeal (1977)............................. 7

IV. The Contempt Proceedings.................................. 7

A. The First Contempt Decision (1 9 8 2 ) ........... 8

B. The Second Contempt Decision (1983) . . . 10

C. The Fund O rd er............................................... 10

D. AAAPO................................................. 11

E. The Third Appeal (1984)............... 11

Summary of Argument.................................................... 13

Page

I l l

Argument . .............. ............................................................ 15

I. Petitioners’ Challenge to Rulings Made a

Decade Ago Are Untimely. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 15

II. AAAPO And The Fund Are Appropriate

Exercises of Civil Contempt Powers . .............. 20

A. Clear and Convincing Evidence Supports

the Contempt Findings Below .................... 20

B. The Fund and AAAPO Constitute a

Precisely Crafted Civil Contempt Sanction

Rather Than a Criminal Penalty ................. 23

C. The Civil Contempt Sanctions Imposed

Are Not Limited by Title V I I ....................... 26

III. The Race-Conscious Remedies Imposed By

The Court Below Comport W ith Title V II

And The Fifth Amendment......................... 28

A. The Race-conscious Remedies Ordered By

The District Court Are Authorized Under

Title V I I ...................... 29

1. A remedy furthering the primary

objective of Title V II of eradicating

discrimination and its continuing effects

is within the scope of section 706(g) of

the A ct.......................................................... 29

2. Section 706(g) grants district courts

broad equitable authority to impose

goals and other race-conscious relief

necessary to remedy proven

discrimination.................................................. 32

Page

IV

a. The plain language of section 706(g)

demonstrates that race-conscious relief

may benefit persons who are not

proven victims of discrimination......... 33

b. The legislative history of Title VII

supports the plain meaning

construction of 7 0 6 (g )............................. 34

3. The decisions of this Court and the

courts of appeals support the use of

narrowly tailored race-conscious

remedies to redress the effects of past

discrimination........... ....................... 42

4. The race-conscious remedies imposed by

the court below further the purposes of

Title V II and are fully supported by the

record................................................................. 48

B. The Remedies Imposed Comport with The

Equal Protection Component of The Due

Process Clause of the Fifth Amendment . . 53

IV. The Creation Of The Office Of

Administrator Was Proper.................................... 57

V. Petitioners’ Challenge To Its Liability And

The Goal, Based On H azelw ood School

District v. United States, 433 U.S. 299

(1977), Is M eritless................................................. 60

Conclusion.......................................................................... 62

Appendix ............................................................................ A-l

Page

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

Cases:

A dickes v. S.H. Kress ir C o., 398 U.S. 144 (1970) 16

A lbem arle Paper Co. v. M oody, 422 U.S. 405

(1 9 7 5 ) ........................................................ passim

Alexander v. Gardner-D enver C o., 415 U.S. 36

(1 9 7 4 ) .......................... 30

Arizona v. C aliforn ia, 460 U.S. 605 (1983) ........... 16, 17, 18

Association Against Discrimination v. City o f

Bridgeport, 479 F. Supp. 101 (D. Conn. 1979),

on rem and fro m , 594 F.2d 306 (2d Cir. 1979) . 50

Association Against Discrimination in

Em ploym ent, Inc. v. City o f Bridgeport, 647

F,2d 256 (2d Cir. 1981), cert, den ied , 455 U.S.

988 (1982) ...................................................................... 44

Berkem er v. M cC arty ,____ U .S ._____, 104 S.Ct.

3138 (1984) ................................................... 20

Bivens v. Six Unknown N am ed Agents o f F ederal

Bureau o f N arcotics, 403 U.S. 388 (1971)........... 27

Bob Jones University v. United States, 461 U.S.

574 (1983) ..................................................................... 38, 42,

55

Boeing Co. v. Van G em ert, 444 U.S. 472 (1980) . 16

Boston C hapter, NAACP, Inc. v. Beecher, 504

F.2d 1017 (1st Cir. 1974), cert, den ied , 421

U.S. 910 (1975)............................................................. 44

Page

VI

Bradley v. School Board, 416 U.S. 696 (1974) . . . . 32

Brandon v. H o l t ,___ _ U.S. _____, 105 S.Ct. 873

(1985) .................................. 16

Bridgeport Guardians, Inc. v. Civil Service

Com m ission, 354 F. Supp. 778 (D. Conn.),

a f f d in part and rev ’d in part, 482 F.2d 133

(2nd Cir. 1 9 7 3 ) ........................................................ 50

Brow der v. D irector, D epartm ent o f Corrections,

434 U.S. 257 (1 9 7 8 ) .................................................... 16

Brown v. Swann, 35 U.S. (10 Pet.) 497 (1836) . . . 27

Buckner v. G oodyear Tire 6- R u bber C o., 339 F.

Supp. 1108 (N.D. Ala. 1972), a f fd , 476 F.2d

1287 (5th Cir. 1973)...................................... 38

Carpenters v. N LRB, 365 U.S. 651 (1 9 6 1 ).............. 33

C arter v. G allagher, 452 F.2d 315 (8th Cir. 1971)

(en banc), cert, den ied , 406 U.S. 950 (1972) . . . 37, 50

Castro v. B eecher, 334 F. Supp. 930 (D. Mass.

1971), a f f ’d in part and rev ’d in part, 459 F.2d

725 (1st Cir. 1 9 7 2 ) ..................................................... 38

Chisolm v. United States Postal Service, 665 F.2d

482 (4th Cir. 1981) ....................................................... 44

Class v. N orton, 505 F.2d 123 (2d Cir. 1974) . . . . 19

Com m issioner v. Sunnen, 333 U.S. 591 (1948) . . . 20

Com munist Party o f the United States v.

Subversive Activities Control Board, 367 U.S. 1

(1 9 6 1 ) .............................................................................. 56

Page

Consolidated Edison Co. v. N LRB, 305 U.S. 197

(1 9 3 8 ) ............................................................................... 33

Contractors Association v. Secretary o f L abor ,

442 F.2d 159 (3d Cir.), cert, den ied , 404 U.S.

854 (1971) ...................................................................... 36

C ooke v. United States, 267 U.S. 517 (1 9 2 5 )........ 26

Cummings v. Missouri, 71 U.S. (4 W all.) 277

(1 8 6 7 ) .............................................................................. 57

Daly v. United States, 393 F.2d 873 (8th Cir.

1968)................................................................................. 18

Davis v. County o f Los Angeles, 566 F.2d 1334

(9th Cir. 1977), vacated as m oot, 440 U.S. 625

(1979) .................... 44

D etroit Police O fficers Association v. Young, 608

F.2d 671 (6th Cir. 1979), cert den ied , 452 U.S.

938 (1981) ........................................................ 44

D othard v. Rawlinson, 433 U.S. 321 (1977)............. 30

D oyle v. London G uarantee i? A ccident C o., 204

U.S. 599 (1907 )..................... ....................................... 23

EEO C v. A m erican Telephone <Lr Telegraph, 556

F.2d 167 (3d Cir. 1977), cert, den ied , 438 U.S.

915 (1978) ..................................................................... 34, 44

Ex Parte G arland, 71 U.S. (4 Wall) 333 (1 8 6 7 )... 57

Ex Parte Robinson, 86 U.S. 505 (1873)...................... 27

F ederated D epartm ent Stores v. M oitie, 452 U.S.

394 (1981) ..................................................................... 18, 20

FTC v. M inneapolis-Honey w ell Regulator C o.,

344 U.S. 206 (1 9 5 2 ) .................................................... 19

v u

Page

vm

Firefighters L o ca l Union No. 1784 v. Stotts, 467

U.S. 561, 104 S. Ct. 2576 (1984) ............................ 14, 20,

34, 40,

48

Ford M otor Co. v. EEO C , 458 U.S. 219 (1982) . . 30, 31,

32

Franks v. Bow m an Transportation C o ., 424 U.S.

747 (1976) ......... ........................ ................................... passim

Fullilove v. Klutznick, 448 U.S. 448 (1 9 8 0 )........... passim

Gary W. v. State o f Lou isiana , 601 F.2d 240 (5th

Cir. 1979).............................. .............. .. 58

G om pers v. B u ck’s Stove 6- Range C o., 221 U.S.

418 (1911) ...................................................................... 22, 24

Griggs v. D uke Pow er C o., 401 U.S. 424 (1971). . 15, 30,

50

H alderm an v. Pennhurst State School i? H ospital,

673 F,2d 628 (3d Cir. 1982) ( en ban c), cert.

den ied , 465 U.S. 1038 (1 9 8 4 ) .................................. 18

H azelw ood School District v. United States, 433

U.S. 299 (1977 )......................... ................................... 7, 16,

60, 61

H echt Co. v. Bowles, 321 U.S. 321 (1944).............. 27

House v. Secretary o f H ealth and Human

Services, 688 F.2d 7 (2d Cir. 1 9 8 2 )...................... 17

Hutto v. Finney, 437 U.S. 678 (1978 )....................... 25, 26,

27

Page

IX

INS v. C hadha, 462 U.S. 919 (1983)......... ............... 41

In Re Peterson, 253 U.S. 300 (1 9 2 0 ) ......................... 59

International B rotherhood o f Teamsters v. United

States, 431 U.S. 324 (1977 )...................................... passim

fam es v. Stockham Valves ir Fittings C o., 559

F,2d 310 (5th Cir. 1977), cert, den ied , 434

U.S. 1034 (1978 )........................................................... 44

L a Buy v. H ow es L ea th er C o., 352 U.S. 249

(1 9 5 7 ) ............................................................................... 60

Lem an v. Krentler-Arnold Hinge Last C o., 284

U.S. 448 (1 9 3 1 ).................................... ........................ 25, 28

L oca l 53, International Association o f H eat sb

Frost Insulators v. Vogler, 407 F.2d 1047 (5th

Cir. 1969), a f f ’g, 294 F. Supp. 368 (E.D. La.

1968)................................................................................. 37

L oca l 60, United B rotherhood o f Carpenters v.

N LRB, 365 U.S. 651 (1961) .................................... 33

Lorillard v. Pons, 434 U.S. 575 (1 9 7 8 )...................... 38

Louisiana v. United States, 380 U.S. 145 (1965) . . 46

Maggio v. Zeitz, 333 U.S. 56 (1 9 4 8 ) ........................... 18

M cCom h v. Jacksonville Paper C o., 336 U.S. 187

(1 9 4 9 ) .............................................................................. 22, 27,

28

M cDaniel v. Barresi, 402 U.S. 39 (1971) ................ 54, 56

Page

X

M cKnight v. United States Steel C orp ., 726 F,2d

333 (7th Cir. 1984)...................... 17

M ichigan v. L on g , 463 U.S. 1032 (1983) . . . . . . . . 29

M illiken v. B rad ley , 418 U.S. 717 (1974) . . . . . . . . 27, 48

M illiken v. Bradley, 433 U.S. 267 (1977) . . . . . . . . 22, 48

Mims v. W ilson, 514 F.2d 106 (5th Cir. 1975) . . . 50

M onsanto Co. v. Spray-Rite Service C orp ., 465

U.S. 752 (1984 )........................................................ 16

M orrow v. Crisler, 491 F.2d 1053 (5th Cir.), cert.

den ied , 419 U.S. 895 (1974) . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 19, 49,

50

M orrow v. D illard, 580 F.2d 1284 (5th Cir. 1978) 49

Myers v. G ilm an Paper C orp ., 544 F.2d 837 (5th

Cir.), cert, dismissed, 434 U.S. 801 ( 1 9 7 7 ) . . . . . 59

NAACP v. Allen, 493 F.2d 614 (5th Cir. 1 9 7 4 ) .. . 37, 49

N ational C ollegiate A thletic Association v. Board

o f R eg en ts ,____ U .S ._____, 104 S. Ct. 2948

(1 9 8 4 ) ............................................................................... 21, 61

N LRB v. Bell A erospace C o., 416 U.S. 267 (1974) 44

N LRB v. L oca l 282, International B rotherhood o f

Teamsters, 428 F.2d 994 (2d Cir. 1 9 7 0 ).............. 19

N evada v. United States, 463 U.S. 110 (1983) . . . . 20

New York State Association fo r R etarded Children

v. Carey, 706 F.2d 956 (2d Cir.), cert, den ied ,

464 U.S. 915 (1 9 8 3 ) ........................................... 58

Page

X I

New York State Commission fo r Human Rights v.

Farrell, 47 Misc. 2d 799, 263 N.Y.S.2d 250

(Sup. Ct. N.Y. Co. 1965) ........................................ 2, 3

Nixon v. Adm inistrator o f G eneral Services, 433

U.S. 425 (1977 )............................................... ............. 57

North Carolina State Board o f Education v.

Swann, 402 U.S. 43 (1 9 7 1 )...................................... 54, 56

North Haven B oard o f Education v. Bell, 456

U.S. 512 (1982 )............................................................. 38

N orthern Pipeline Construction Co. v. M arathon

Pipe L ine C o., 458 U.S. 50 (1982)......................... 59

Paradise v. Prescott, 767 F.2d 1514 (11th Cir.

1985)................................................................................. 44

Pasadena Board o f Education v. Spangler, 427

U.S. 424 (1976 )............................................................. 16

Penfield Co. v. SEC, 330 U.S. 585 (1 9 4 7 ) ................ 22

Porter v. W arner Holding C o., 328 U.S. 395

(1 9 4 6 )............................................................................... 27

Pow ell v. W ard, 643 F.2d 924 (2d Cir.), cert.

den ied , 454 U.S. 832 (1 9 8 1 ) .......................... 21

Pullman-Standard v. Swint, 456 U.S. 273 (1982) . 9

Red L ion Broadcasting Co. v. FC C , 395 U.S. 367

(1 9 6 9 ) ............................................................................... 44

Regents o f the University o f California v. B akke,

438 U.S. 265 (1 9 7 8 ) .................................................... 37, 44,

54, 55,

56

Page

X ll

Rios v. Enterprise Association Steam fitters L o ca l

638, 501 F.2d 622 (2d Cir. 1 9 7 4 ) . . . . . . . . . . . . . 44

R oadw ay Express, Inc. v. Piper, 447 U.S. 752

(1980) . ...................................................... ...................... 27

Rogers v. L odge, 458 U.S. 613 (1982)................ 61

Ruiz v. Estelle, 679 F.2d 1115 (5th Cir. 1982),

cert, den ied , 460 U.S. 1042 (1983) ....................... 58, 59

Selective Service System v. M innesota Public

Interest R esearch G r o u p ,____U .S ._____ , 104

S. Ct. 3348 (1984) ........... .. 56

Shillitani v. United States, 384 U.S. 364 (1 9 6 6 )... 22

Sidney v. Zah, 718 F.2d 1453 (9th Cir. 1983) . . . . 19

Southern Illinois Ruilders Association v. Ogilvie,

471 F.2d 680 (7th Cir. 1972) . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 36

Swann v. Charlotte-M ecklenburg B oard o f

Education , 402 U.S. 1 (1971) .............................. 27, 48,

54, 56

System Federation No. 91 v. W right, 364 U.S.

642 (1961) ............................................... .. 16, 17

Taylor v. Jones, 489 F. Supp. 498 (E.D. Ark.

1980), a f f ’d , 683 F.2d 1193 (8th Cir. 1981) . . . . 51

Thom pson v. Sawyer, 678 F.2d 257 (D.C. Cir.

1 9 82 )............................................. 44

Thorn v. R ichardson, 4 F .E .P . Cases 299 (W .D.

Wash. 1971).................................................................... 37

Page

X1U

United Jew ish Organization v. C arey , 430 U.S.

144 (1977) ...................................................................... 54, 55,

56

United States v. Arm our ir C o., 398 U.S. 268

(1 9 7 0 ) ............................................. 26

United States v. City o f Buffalo, No. 85-6212 (2d

Cir., December 19, 1 9 8 5 ) ......................................... 47

United States v. City o f Chicago, 549 F.2d 415

(7th Cir.), cert, den ied , 434 U.S. 875 (1977) . . . 44

United States v. Hudson, 11 U.S. (7 Cranch) 32

(1 8 1 2 ) ................................................................. .. 26

United States v. International Union o f Elevator

Constructors, L oca l 5, 538 F.2d 1012 (3d Cir.

1976)................................................................................. 44

United States v. Ironw orkers L oca l 86, 443 F,2d

544 (9th Cir.), cert, den ied , 404 U.S. 984

(1 9 7 1 ) ............................................................................. 37

United States v. L e e W ay M otor Freight, Inc.,

625 F.2d 918 (10th Cir. 1979) ................................. 37

United States v. L oca l 638, 337 F. Supp. 217

(S.D.N.Y. 1972) .......................................................... 37

United States v. Lovett, 328 U.S. 303 (1946)......... 56, 57

United States v. M ontgom ery County Board o f

Education, 395 U.S. 225 (1 9 6 9 )............................. 23, 54

United States v. N .L. Industries, In c., 479 F.2d

354 (8th Cir. 1973)...................................................... 30, 44

United States v. R addatz, 447 U.S. 667 (1980) . . . 59

Page

X IV

Page

United States v. Rylander, 460 U.S. 752 (1983) . . 18

United States v. Secor, 476 F.2d 766 (2d Cir.

1 973 )............................................. .. .............. .. 18

United States v. Sheetm etal W orkers, L o ca l 10, 3

CCH Empl. Prac. Dec. 1 8,068 (D.N .J. 1970) . 37

United States v. Sheetm etal W orkers, L o ca l 36,

416 F.2d 123 (8th Cir. 1 9 6 9 ) ........... ...................... 37

United States v. Swift <b C o., 286 U.S. 106 (1932) 17

United States v. United M ine W orkers, 330 U.S.

258 (1947) ..................................................................... 22, 25,

26

United Steelw orkers v. W eber, 443 U.S. 193

(1 9 7 9 ) ........... passim

W alker v. City o f B irm ingham , 388 U.S. 307

(1 9 6 7 ) ............................................................................... 27

W einberger v. R om ero-B arcelo , 456 U.S. 305

(1 9 8 2 ) .......................................................... 27

W illiams v. City o f New Orleans, 729 F.2d 1554

(5th Cir. 1984) (en b a n c ) ......................................... 44

W orld ’s Finest C hocolate Inc. v. W orld Candies,

In c., 409 F. Supp. 840 (N.D. 111. 1976), a f f ’d,

559 F.2d 1226 (7th Cir. 1977) ............................... 18

Wirtz v. L oca l 153, Glass Bottleblow ers

Association, 389 U.S. 463 (1968) ............................. 58

XV

Constitution and Statutes:

U.S. Const.:

Amend. V (Due Process Clause)............................. 53

Amend. XIV ................................................................. 37

Civil Rights Act of 1964........... ...................................... passim

Tit. V II, 42 U .S.C. § 2000e et s eq ......................... 2, 5

42 U .S.C. § 2000e-2(j) ........................... 33, 35

42 U.S.C. § 2000e-2(h)........................... 43

42 U .S.C. § 2000e-5(g).................. .. passim

42 U.S.C. § 2000e-6(a)........................... 32, 43

42 U.S.C. § 2000e-6 (c)........................... 43

42 U.S.C. § 2000e-14 ............................. 43

42 U .S.C. § 2000e~16 ............................. 42

Tit. X I, 42 U .S.C. § 2000h et seq. ...................... 27

29 U.S.C. § 1 6 0 (c ) ........................................................ 32

28 U.S.C. § 2101 ............................................................. 16

1968 N.Y. Laws ch. 958 ............................................... 4

New York City Administrative Code § B l-7 .0 . . . . 4, 5, 29

Page

X V I

Rules, Regulations and Orders:

Sup. Ct. R. 20 .................... 16

Sup. Ct. R. 21 .1 (a ) ....................... 20

Fed. R. Civ. P. 5 2 (a ) ........... 9

Fed. R. Civ. P. 5 3 ............................. 59

Fed. R. Civ. P. 60(b)(6) ................................................ 17

Fed. R. Crim. P. 4 2 ......... ................................... ........... 27

28 C .F .R . § 42.203 (i, j) (1 9 8 5 ).................... 43

29 C .F .R . § 1607.17 (1985)........................... 43

29 C .F .R . § 1608.1(b) (1 9 8 5 ) ........................ 29

29 C .F .R . § 1608.4(c) (1 9 8 5 ) ........... 43

E .O . 11246, 30 Fed. Reg. 12,319 (1965) ................ 36, 40

E .O . 12067, 43 Fed. Reg. 19,807 (1978) . . . . . . . . 43

41 Fed. Reg. 38,814 (1976 )........................................... 43

Legislative History:

110 Cong. Rec. (1964)

p. 1 5 1 8 ............................................................... 35

p. 1540 ................................................................. 35

p. 1600 ............................................................................. 35

p. 6548 .................... 29

p. 6566 ........................................................................ 35

p. 2558 ............................. 35

p. 2567-70 ...................................................................... 34

p. 5092 ............................................................................. 35

Page

X V II

p. 6547-49 ...................................................................... 29, 30,

34, 35

p. 6566 ............................................................................. 30

p. 7204 ........................................ 30

p. 7207 ................................................. 35

p. 7 2 1 3 -1 4 ...................................................................... 35

p. 8921 ............................................... 35

p. 11,848 ................................................. 35

p. 14,465 ........................................ 35

p. 15,876 ...................................... 35

115 Cong. Rec. (1969)

p. 39,961 ........................................................................ 37

p. 40,039 . ................................................. 37

p. 40,740-746...................................... 36 , 41

p. 40,905-909............................... 36, 41

p. 40,915-919................................................................. 36 , 41

p. 40,921 ........................................................................ 36

117 Cong. Rec. (1971)

p. 31,965-967........................... 40 , 41

p. 32,099-100................................................................. 41

p. 3 2 ,1 1 1 ........... 40

118 Cong. Rec. (1972)

p. 1661-76 ...................................................................... 36, 37,

40

p. 2298 ............................................................................ 42

p. 4917-18 ........................................ 40

p. 7167-68 ...................................................................... 38

H.R. Rep. No. 238, 92 Cong., 1st Sess. (1971),

reprinted in 1972 U.S. Code Cong. & Ad News

2137 ................................................................................. 31, 32,

38, 40

H.R. Rep. No. 914, 88th Cong., 1st Sess. (1964),

reprinted in 1964 U.S Code Cong. & Ad. News

2391 ................................................................................. 30, 34

Page

XV111

S. Rep. No. 415, 92d Cong., 1st Sess. (1971)......... 30, 38,

42

Sub, Comm, on Labor of the Senate Comm, on

Labor & Public Welfare, 92d Cong., 2d Sess.,

Legislative History o f the E qual Em ploym ent

Opportunity Act o f 1972 (Comm. Print 1972) . . passim

EEO C , Legislative History o f Titles VII and XI

o f the Civil Rights Act o f 1964 ................................ 34, 35

Law Review Articles:

Beale, C ontem pt o f Court, Crim inal and Civil, 21

Harv. L. Rev. 161 (1 9 0 8 ) ...................................... . 26

Blumrosen, The Duty o f Fair Recruitm ent, 22

Rutgers L. Rev. 465, 490 (1968) ......... .. 51

Comment, The Philadelphia Plan: A Study in the

D ynamics o f Executive Powers, 39 U. Chi. L.

Rev. 723 (1972)............................................................. 37, 40

Harris, The Title VII Adm inistrator: A Case

Study in Ju d icia l Flexibility, 60 Cornell L. Rev.

53 (1974) ............................................... ........................ 58

Special Project, The R em edial Process in

Institutional R eform Litigation , 78 Colum. L.

Rev. 784, 846 (1978) .................. ............................ .. 58

Speigelman, C ourt-O rdered Hiring Quotas A fter

Stotts, 20 Harv. C .R .-C .L .L . Rev. 339 (1985) . 45, 51

Page

X IX

Page

Miscellaneous:

4 W. Blackstone, Commentaries........... ...................... 26

42 Op. Atty. Gen. 405 (1969)...................... 36

1 1 C . Wright & A. Miller, F ederal Practice &■

P ro ced u re ............................... ..................................... . 17

IB J , Moore, M oore’s F ederal Practice (2d ed.

1982)................................................................................. 17

7 J. Moore, M oore’s F ederal Practice (2d ed.

1985)............................... 17

Restatem ent (Second) Judgm ents (1 9 8 2 ) ................. 17

1

STATEMENT OF THE CASE

I. Preliminary Statement

The contempt orders before the Court constitute the most re

cent in a two decade-long, judicially supervised effort to com

pel Local 28 of the Sheet Metal Workers International Associa

tion (“Local 28”) and its Joint Apprenticeship Committee (“JAC”)

to comply with local, state and federal fair employment laws.

Since 1964, Local 28 and the JAC (collectively referred to as “the

Local” or “petitioners”) have been found repeatedly to have

discriminated unlawfully against minorities, to have ’consistently

and egregiously” violated the fair employment laws and to have

“defied” enforcement orders (A. 212, 215)} Nevertheless, they now

are asking the Court to rewrite that history. They claim that the

ten-year old liability determination of the district court was

wrong, that important elements of the district court’s long

standing remedial order are unauthorized and that they should

not have been held in contempt.

The United States government1 2 initiated this case in 1971,

established liability, urged the remedial measures adopted by the

court and repeatedly defended all of the court’s remedial and

coercive orders (JA. 5-8, 157-61, 275-83, 372-74). The Equal

Employment Opportunity Commission (“EEO C”), which is

represented in this Court by the Solicitor General,3 agrees with

1 The designation “A .____ ” refers to pages in the appendix to the Petition for

Writ of Certiorari. The designation “JA. ____ ” refers to pages of the Joint

Appendix.

2 This action was filed on June 29, 1971, on behalf of the United States (JA.

372, 344). In April 1974, as a result of the 1972 amendments to Title V II of

the Civil Rights Act of 1964, see 42 U.S.C. § 2000e-6(c), the Equal Employ

ment Opportunity Commission was substituted for the United States as plain

tiff. (JA. 344).

3 Because the argument of the United States in this case is set forth in briefs

filed in four separate cases currently before the Court and the EEO C appears

in only this case, respondent will refer to the United States or the EEOC, as

the case may be, as simply the “Solicitor.” The form of citation used for referr

ing to the Solicitor’s briefs in the four cases is as follows:

Brief for the EEO C in No. Sol. Loc. 28 B r .____

84-1656, L oca l 28 v. E EO C

(footnote continued)

2

respondents City of New York (“City”) and New York State Divi

sion of Human Rights (“State”) that petitioners properly were

held in civil contempt and that the sanctions ordered constituted,

with an important exception, appropriate civil contempt

remedies. Nonetheless, the Solicitor now contends that the 29 %

goal, and the race-conscious aspects of the contempt order it too

joined in seeking, are beyond the power of the district court.

The contempt orders draw their significance from the facts

found and the extensive prior proceedings in this case. Because

neither the petitioners nor the Solicitor have adequately described

the facts and prior proceedings, respondent restates them below.

II. Proceedings Against L oca l 28 Prior

to This Federal Court Action.

Local 28 was formed in 1913 under an international union con

stitution which contemplated the establishment of racially

segregated “white local union(s)” and, if necessary, black “aux

iliary local unions.” The black unions were to be “subordinate

to the established and affiliated white local union” (A. 322, JA.

318). Although racial restrictions were deleted from the interna

tional constitution in 1946, Local 28 retained its racially exclusive

character until 1969, long after the effective date of Title VII

of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, 42 U.S.C. § 2000e, et seq. (“Title

V II”) (JA. 314, 333-34). The union did not waver in its racially

restrictive admissions practices except under court orders (A. 411,

JA. 320, A. 215, 300, 182, 125, 119, 111, 108). See also New York

State Commission fo r Human Rights v. Farrell, 47 Misc. 2d 799,

263 N.Y.S. 2d 250 (Sup. Ct. N.Y. Co. 1965).

In 1964, the New York State Commission For Human Rights4

found petitioners guilty of a continuing pattern of unlawful

Amicus curiae brief for the United States Sol. Loc. 93 Br. ____

in No. 84-1999, L oca l 93 v. City o f

C leveland

Amicus curiae brief for the United States Sol. Wygant Br. ____

in No. 84-1340, Wygant v. Jackson Board o f

Education

Amicus curiae brief for the United States Sol. Orr Br. ____

in No. 85-177, Orr v. Turner

4 In 1968, the State Commission was reorganized and renamed the New York

State Division of Human Rights. See 1968 N.Y. Laws ch. 958.

3

discriminatory practices caused by pervasive nepotism within the

union as well as a naked policy of not admitting blacks (JA. 381,

407). It ordered petitioners to “cease and desist from denying to

. . . Negroes because of their race . . . the right to be admitted

to . . . the sheet metal apprenticeship program”5 (JA. 388).

Because the Local ignored its order, later that year the Com

mission commenced a proceeding in the New York State Supreme

Court to force compliance (A. 411). Justice Jacob Markowitz con

firmed that the Local had violated the New York Law Against

Discrimination. He supervised negotiations aimed at racially in

tegrating the union and creating a remedial program which

substituted an objective apprentice selection procedure for the

existing nepotistic selection system (A 415, 421). Justice Markowitz

ultimately entered an order, entitled the “Corrected Fifth Draft

of Standards for the Admission of Apprentices” (“Corrected Fifth

Draft”), which provided for selection of apprentices on the basis

of education, written test scores and personal interviews (A. 427,

431). He rejected Local 28’s suggestion that “some preference”

be given applicants with familial ties to union members (A. 421).

The parties also negotiated an agreement, approved by the court,

requiring the JAC to indenture two 65-person apprenticeship

classes. See Farrell, 47 Misc. 2d at 799. As these agreements were

reached, Justice Markowitz noted that the adopted plan “was

the result of the unusual cooperative spirit” of the parties (A. 425;

see also A. 440). Although not acknowledged by petitioners, “by

1965, Justice Markowitz’ praise had turned to fury” (A. 139)

because the union had disregarded its court-ordered obligations.

Claiming unemployment among its members, the union reduc

ed the size of the second apprentice class from 65 to 30. In his

decision ordering the union to comply with his previous order,

Justice Markowitz declared: “[t]he union, unilaterally, is attempt

ing to halt or severely limit the process of its legally required in

tegration . . . .” Farrell, 47 Misc. 2d at 800. By 1969, however,

the union had devised a means of circumventing Justice

Markowitz’s prohibition of nepotism in the selection of appren

tices: it began paying for pre-examination training sessions for

5 Participation in the apprenticeship program is the principal means of admis

sion to membership in Local 28 (A. 325, JA. 303).

4

relatives of union members (A. 352). Furthermore, in the areas

governing access to work in the construction sheet metal trade

that had not been specifically addressed by Justice Markowitz,

the union’s policy of racial exclusion continued unchecked. See

p. 5, infra.

III. Federal Court Proceedings

Prior to the Contem pt Motion

In June 1971, the United States Department of Justice, pur

suant to Title VII, filed this suit against the Local to enjoin a

pattern and practice of discrimination against black and Spanish

surnamed individuals (“minorities”) who sought membership in

Local 28 and training and job opportunities in the sheet metal

trade in New York City. At that time (seven years after the State

had first taken action), minorities constituted 1.63% of the union’s

membership (JA. 323). The City intervened and alleged, inter

alia, that the union and JAC were violating the City’s fair employ

ment practices ordinance, Bl-7.0 of the New York City Ad

ministrative Code (“NYC Code § ____ ”), and were frustrating

the City’s efforts, through its contract compliance program, to

increase training opportunities for minorities.6

A. Judge Gurfein’s Consent Orders

In early 1974, work stoppages occurred on New York City and

New York City Board of Education construction sites. They were

aimed at preventing sheet metal contractors from employing

minority trainees on City and Board of Education funded con

struction projects. In response, the Sheet Metal Contractors

Association (“Contractors Association”) sought a court order in

this action restraining Local 28 from engaging in such work

stoppages7 (JA. 355). As a result of this court action, the late

United States District Judge Murray Gurfein, in April and July,

6 The Local joined the State as a third party defendant but the State was realign

ed as a plaintiff (A. 319).

7 As of 1974, Local 28 was the only union local in New York City that refused

to participate voluntarily in the New York Plan For Training, the program that

provides for the training and employment of minority “trainees” on federal and

New York State construction projects in New York City (JA. 354, 320).

5

1974, entered consent orders which required the JAC to inden

ture at least 40 minority apprentices by September 30, 1974 (JA,

363-64, 356). The union did not meet the September 30 deadline.

It did little to comply with Judge Gurfein’s orders until it faced

the immediate threat of a contempt finding8 (A. 352, JA, 345-47,

356-58).

B. Liability Determination

Following a trial in 1975 before the late United States District

Judge Henry Werker, the court found that petitioners had in

tentionally discriminated against minorities in violation of both

Title VII and NYC Code § Bl-7.0 by administering discriminatory

entrance examinations; excluding persons who lacked a high

school diploma; offering cram courses to the sons and nephews

of union members but not to minority applicants; refusing to ac

cept blowpipe sheet metal workers for membership because most

such workers were members of minority groups; consistently

discriminating in favor of white applicants seeking to transfer

into Local 28 from sister locals; refusing to administer journeyman

examinations because of their concern that minority candidates

would do well, and, instead, issuing work permits to non

members on a discriminatory basis; and failing to organize non

union sheet metal shops owned bv or employing minorities (A.

330-50).

On the basis of these findings and a recognition that the “record

in both state and federal court against these defendants is replete

with instances of . . . bad faith attempts to prevent or delay af

firmative action” (A. 352), the court, on August 29,1975, entered,

pursuant to Fed. R. Civ. P. 54, an Order and Judgment (“O&J”).

It enjoined petitioners from all violations of Title VII and ordered

them to achieve, by July 1, 1981, a remedial goal of 29 % minority

membership (JA. 142, A. 305, 354). This goal was based on the

8 Petitioners refer to these consent orders when they declare that “racial hiring

pursuant to fixed and intransigent percentages has been involved in this action

even before the entry of the O&J in 1975.” Pet. Br. at 5 n.7. While claiming

that “these orders were complied with,” (id.) petitioners neglect to acknowledge

that, as the court of appeals observed, compliance occurred “under heavy

pressure” (A. 215). Petitioners also contend that they “objected” to Judge Gur

fein’s orders. Pet. Br. at 42, a contention which is unsupported by the record

(JA. 356-58).

6

relevant minority labor pool in New York City (A. 300, 305,

353-54). The court also ordered petitioners to eliminate the

diploma requirement for the apprenticeship program, to offer

non-discriminatory entrance exams for journeymen and appren

tices, and to allow transfers and issue temporary work permits

on a non-discriminatory basis (A. 354-56, 301-04, 308-10). Peti

tioners were required to engage in extensive recruitment and

publicity campaigns in minority neighborhoods in order to dispel

Local 28’s reputation for discrimination and to ensure a broad

applicant pool (A. 355, 312). They were also directed to main

tain records regarding applications, requests for transfer, inquiries

about permit slips and hiring (A. 355, 310-11). The court ap

pointed an administrator to supervise compliance with its decree

(A. 355, 305-07).

C. The First A ppeal (1976)

On appeal, the Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit af

firmed, finding ample evidence that petitioners “consistently and

egregiously violated Title V II” (A. 212). Indeed, the Local ’’[did]

not even make a serious effort to contest the finding of Title VII

violations” in this initial appeal (A. 215). The court upheld the

29 % goal as a temporary remedy, distinguishing it from ”a quota

used to bump incumbents or hinder promotion of present

members of the work force” (A. 221-22). It also upheld the re

quirement that entrance examinations be validated and ruled that

the testing schedules and recruitment requirements imposed by

the district court were appropriate exercises of the district court’s

discretion (A. 222). The court modified the relief ordered by

eliminating any provision that “might be interpreted to permit

white-minority ratios for the apprenticeship program after the

adoption of valid, job-related entrance tests” (A. 225). It con

cluded that the appointment of an administrator with broad

powers was “clearly appropriate,” given petitioners’ failure to

change their membership practices pursuant to the prior orders

of the district court and the New York State court (A. 220).

The Local did not seek review in this Court of the court of

appeals’ judgment, which finally determined all issues in the

action.

7

D. Entry o f RAAPO

On January 19, 1977, following the court of appeals’ affir

mance, the district court issued a revised affirmative action pro

gram and order (“RAAPO”) (A. 182). Among other things,

RAAPO granted the Local an additional year in which to meet

the 29 % membership goal. The court ordered the Local to make

“substantial and regular” progress every year in admitting

minorities to Local 28 (A. 183). Modifications were also made

to provide that, during a time of widespread unemployment in

the industry, apprentices would share equitably in available

employment opportunities in the industry (A. 183-84). The court

ordered the JAC to take all reasonable steps to insure that ap

prentices receive adequate employment opportunities and to in

denture two classes of apprentices each year, the size of each class

to be determined by the JAC, subject to review by the ad

ministrator (A. 192-93).

E. The Second A ppeal (1977)

The union and JAC appealed six provisions of RAAPO, in

cluding the apprenticeship indenture requirement and a provi

sion granting certain oversight powers to the administrator (A.

165). They also challenged the imposition of the goal and, on

the basis of the intervening decision of this Court in H azelw ood

School District v. United States, 433 U.S. 299 (1977), disputed

the 1975 finding of liability (A. 164-68). The court of appeals

rejected petitioners’ arguments based on H azelw ood , affirmed

RAAPO in its entirety and upheld the administrator’s powers (A.

160, 165-68). Once again, the Local did not seek a writ of cer

tiorari from this Court, even though Judge Meskill in dissent in

vited them to do so (A. 170 n.l).

IV. The Contem pt Proceedings

In 1982, the City and State, recognizing that Local 28 would

not achieve the 29 % goal by July 1 because it had failed to com

ply with several substantive provisions of the O&J and RAAPO,

moved for an order holding petitioners in contempt. The union

and JAC cross-moved for an order terminating the O&J and

RAAPO.

8

A. The First Contem pt Decision (1982)

Following a hearing, the district court found that the Local

had “impeded the entry of minorities into Local 28 in contraven

tion of the prior orders of this court” (A. 149-50).9 Judge Werker

held them in contempt for violating the O&J and RAAPO by

a) underutilizing the apprentice program to the detriment of

minorities; b) failing to undertake, as required by RAAPO, a

general publicity campaign intended to dispel petitioners’ reputa

tion for discrimination; c) failing to maintain and submit records

and reports; d) issuing work permits without prior authoriza

tion of the administrator; and e) entering into an agreement

amending their collective bargaining contract by adding a pro

vision that discriminates against Local 28’s minority members

by protecting members aged fifty-two or over during periods of

high unemployment. The cumulative effect of these contemp

tuous acts, the district court ruled, was that the Local failed even

to approach the 29 % goal, a benchmark of progress toward in

tegration and equal employment opportunity10 (A. 155-56).

The first contempt holding was based in part on the district

court’s finding that petitioners had deliberately underutilized the

apprenticeship program in order to limit minority membership

and employment opportunities. The court found that the JAG

trained substantially fewer apprentices after entry of the O&J

than before. The court rejected the Local’s contention that the

underutilization of the apprenticeship program resulted from a

downturn in the economy. To the contrary, the average number

9 Petitioners’ assertion, Pet. Br. at 9, that they had achieved a minority member

ship in Local 28 of 14.9% by April 1982 was rejected by both the district court

and the court of appeals (A. 9). Petitioners’ own April 1982 census showed its

minority membership to be only 10.8 %. Similarly, petitioners’ claim that 45 %

of their apprentice classes are made up of minorities, Pet. Br. at 9, is misleading.

Only since January 1981 have petitioners indentured apprenticeship classes con

sisting of 45% minorities (A. 37).

10 Although Local 28’s total minority journeyman and apprentice membership

was then only 10.8%, more than 18 percentage points below the ultimate goal

petitioners had been ordered to reach by July 1, 1982, the district court did

not base its finding of contempt upon petitioners’ failure to reach the goal (A.

155). Instead the court focused on the union’s failure to make regular and

substantial progress toward integrating minorities into its membership (A.

155-56).

9

of hours and weeks worked per year by Local 28 journeymen

members steadily increased from 1975 to 1981 (A, 16, 151). In

fact, by 1981, employment opportunities so exceeded the available

supply of Local 28 journeymen that Local 28 was compelled to

issue an extraordinary number of work permits to non-member

sheet metal workers, most of whom were white (A. 16). Thus,

the court concluded that during the years after entry of the O&J,

Local 28 deliberately shifted employment opportunities from ap

prentices to predominantly white, incumbent journeymen.11 That

the ratio of journeymen to apprentices rose from 7:1 before the

O&J was entered to 18:1 by 1981, well above the industry stan

dard of 4:1, demonstrated the extent of the shift (A. 16).“

The court based its finding that petitioners issued permits

without the administrator’s approval upon evidence that Local

28 had done so thirteen times between March and June 1981.

Of the thirteen unauthorized permit men, only one was minori

ty. These contemptuous acts were particularly significant given

the district court’s earlier finding, after trial, that Local 28 had

used the permit system to restrict the size of its membership with

the illegal effect of denying minorities access to employment op

portunities in the sheet metal industry (A. 345-46).

Local 28 was also held in contempt for entering into a

Memorandum of Agreement with the Contractors Association

to guarantee older (age 52 or older) sheet metal workers one of

ever\" four jobs during periods of high unemployment (the “older

workers’ provision”). The district court concluded that this pro

vision violated the O&J since it had the foreseeable consequence

of disadvantaging the predominantly young minority members

of the union (A. 155). * 12

u Petitioners erroneously assert, Pet. Br. at 9, that the administrator approved

each apprentice class. What petitioners mistakenly refer to are the reports

ultimately submitted to the administrator informing him of the number of ap

prentices in the JAC program (A. 42 n.3). The administrator neither approved

nor disapproved individual apprentice classes.

12 As the majority opinion of the court of appeals illustrates (A. 22-24), neither

petitioners’ argument nor Judge Winter’s dissent demonstrates that the

underulitization finding was clearly erroneous. Fed. R. Civ. P. 52(a); Pullman-

Standard. v. Swint, 456 U.S. 273 (1982).

10

Finally, petitioners were held in contempt for violating the pro

visions of the O&J and RAAPO requiring them to devise and

implement a written plan for an effective general publicity cam

paign designed to dispel their reputation for discrimination in

minority communities (A. 152-53). The general publicity plan

required by the O&J and RAAPO was never formulated, much

less implemented (A. 152). Finally, the union and JAG were held

in contempt for failing, since 1976, to comply with the impor

tant reporting requirements of the O&J and RAAPO and with

the administrator’s request for information relevant to the im

plementation of RAAPO (A. 154-55).

The district court denied petitioners’ cross-motion to terminate

the O&J and RAAPO, finding that their purposes had not been

achieved and that these orders had not caused the Local unex

pected or undue hardship (A. 157).

B. The Second Contem pt Decision (1983)

On April 11, 1983, the City brought a proceeding against the

Local for additional violations of the O&J and RAAPO. After

a hearing, the administrator found that the Local had again acted

contemptuously by failing to provide data required by the O&J

and RAAPO, failing to send copies of the O&J and RAAPO to

all new contractors in the manner ordered by the administrator,

and failing to provide accurate reports of hours worked by ap

prentices (A. 127, 128-38). The district court adopted the ad

ministrator’s findings and again held the Local in contempt (A.

125).

C. The Fund Order

To remedy petitioners’ past noncompliance, Judge Werker im

posed a fine of $150,000 for the first series of contemptuous acts

and additional fines of $.02 per hour for each journeyman and

apprentice hour worked for the second series of contemptuous

acts (A. 113, 114). These fines are to be placed in an interest-

bearing Local 28 Employment, Training, Education and Recruit

ment Fund (the “Fund”) to be used, among other things, to pro

vide financial assistance to contractors otherwise unable to meet

a 4:1 joumeyman-to-apprentice ratio, to provide incentive or mat

ching funds to attract additional funding from governmental or

private job training programs, to establish a tutorial program for

11

minority first year apprentices, and to create summer or part-

time sheet metal jobs for minority youths who have had voca

tional training (A. 116-18). The Fund is to “remain in existence

until the [new minority membership] goal set forth in the Amend

ed Affirmative Action Program and Order (“AAAPO”) . . . is

achieved and until the Court determines that it is no longer

necessary” (A. 114). The Fund is subject to AAAPO, which pro

vides that Local 28 may provide whites with the benefits afforded

under the program to minorities (A. 76, 118, 253). Upon termina

tion, any sums that remain are to be returned to the union (A.

116).

D. AAAPO

Because the remedial purposes of RAAPO had not been achiev

ed and because of the Local’s contemptuous conduct, the district

court on November 4, 1983, entered a new replacement order,

AAAPO (A. 53, 111). AAAPO modified RAAPO in a number of

respects. It adjusted the minority membership goal from 29 %

to 29.23 % to reflect Local 28’s expanded jurisdiction (due to the

merger of several unions into Local 28) and a population change

in the relevant labor pool (A. 54,122-23). It extended the deadline

for meeting the goal until August 31, 1987 (A. 55). It also re

quired that one minority applicant be indentured into the ap

prenticeship program for each white applicant indentured and

that (unless this provision were waived by plaintiffs) the JACs

assign each Local 28 contractor one apprentice for every four

journeymen (A. 57).

E. The Third A ppeal (1984)

Petitioners appealed to the court of appeals from the contempt

orders, the Fund order and the order adopting AAAPO. They

did not appeal the denial of their cross motion to terminate the

O&J and RAAPO (A. 12), nor did they contend that the 1975

findings of liability were erroneous or that the administrator

should not continue in office.13 By a 2-1 vote, the court of appeals

affirmed all of the district court’s findings of contempt against

13 The Local argued that the administrator’s powers should be curtailed to limit

his authority to adjudication of disputes under AAAPO. See Brief for Appellants

Local 28 and the JAC at 92.

1 2

the Local, except the finding based on the older workers’ provi

sion.14 It also affirmed the contempt remedies, including establish

ment of the Fund. With respect to the first contempt proceeding,

the court of appeals held that the evidence “solidly supports Judge

Werker’s conclusion that defendants underutilized the appren

ticeship program . . . ” (A. 17). The court concluded, “[p]ar-

ticularly in light of the determined resistance by Local 28 to all

efforts to integrate its membership, . . . the combination of viola

tions found by Judge Werker . . . amply demonstrates the union’s

foot-dragging egregious noncompliance . . . and adequately sup

ports his findings of civil contempt against both Local 28 and

the JAC” (A. 24). With respect to the second contempt pro

ceeding, the court held that the district court’s determination

was supported by “clear and convincing evidence which showed

that defendants had not been reasonably diligent in attempting

to comply with the orders of the court and the Administrator”

(A. 22).

The court affirmed AAAPO with two modifications: it set aside

the requirement that one minority apprentice be indentured for

every white, concluding that the ratio was unnecessary in order

to assure progress toward the goal, and it modified AAAPO to

permit the use of validated selection procedures before the 29.23 %

membership goal is reached. In addition, the court concluded

that the Fund was an appropriate coercive and compensatory

contempt remedy. The district court had aimed the relief at the

apprenticeship program, where it would be most effective, and

the Fund would compensate those who had suffered the most

from defendants’ contemptuous conduct. It also noted the Fund’s

coercive aspects and observed that its operation would cease and

any remaining monies would be returned when the Local reached

the 29.23% goal (A. 26).

For the third time, the court reaffirmed the 29.23 % member

ship goal, finding that it met the court of appeals’ two-pronged

14 The court of appeals did not overturn the finding that the provision violated

the O&J, but concluded that “the older workers’ provision was never im

plemented, and therefore did not have any effect—discriminatory or

otherwise—on nonwhites” (A. 17). It remanded this issue for further fact fin

ding and directed that if the provision were found to discriminate, the district

court should “strike it from the collective bargaining agreement . (A. 19).

Since this finding was the sole basis for the orders directed at sheet metal con

tractors, the court of appeals vacated the district court’s orders as to them (A. 37).

13

test for the validity of a temporary, race-conscious affirmative

action remedy (A. 29). First, the remedy was designed to cor

rect a long, continuing and egregious pattern of race discrimina

tion. Second, the remedy “will not unnecessarily trammel the

rights of any readily ascertainable group of non-minority in

dividuals” (A. 32).

Finally, the court rejected the Local’s attempt to curtail the

powers of the administrator (A. 36).

This judgment of the court of appeals affirming the contempt

orders is here on review.

SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT

Ten years ago, after finding a pervasive pattern of racial ex

clusion and noting a record of past noncompliance with court

orders directing the union to end discrimination, the district court

entered a series of comprehensive remedial orders. These orders

were intended to do more than restate the proscriptions of Title

VII against discrimination and compensate individuals specifical

ly harmed by the union’s prior conduct. They were also design

ed to insure, through the imposition of effective remedial

measures, that the union did not return to its discriminatory ways.

Given the union’s failure to “clean house,” the court determined

that the imposition of a remedial racial goal was ’’essential” and

directed that “regular and substantial progress” be made toward

reaching it. The goal was essential because the practices, habits

and customs within the union had, for generations, made racial

exclusion a fixed part of its members’ daily lives and expecta

tions. Because access to admission, membership, training and

employment in the trade ordinarily was obtained through infor

mal contacts among union members, the district judge in this

case knew that he would have no greater success than the judges

who preceded him in altering the indifference within the union

to fair employment laws unless substantial numbers of minority

workers were to become part of the informal mutual support

system that pervades the trade.

1. The district court determined liability and established the

numerical goal and the office of the administrator a decade ago.

The legitimacy of these determinations was upheld by the court

14

of appeals and no further review was sought. Accordingly, res

judicata bars further review of the correctness of these rulings,

which, in any event, were correctly made.

2. The court of appeals correctly concluded that the district

court acted properly in holding petitioners in civil contempt. It

noted 1) that the effect of the combined violations found by the

district court operated to prefer the largely white group of

journeymen over the racially integrated group of apprentices and

2) that the union historically “resisted . . . all efforts to integrate

its membership” (A. 24).

The court of appeals also correctly concluded that the sanc

tions imposed were designed to coerce compliance with the two

remedial orders of the district court. The sanctions imposed were

designed to assure plaintiffs and the intended beneficiaries of the

remedial orders that, unlike prior judicial orders directing the

union to comply with the fair employment laws, the O&J and

RAAPO would be obeyed. The sanctions were also intended to

provide compensatory relief to the class of persons harmed by

petitioners’ persistent discriminatory conduct. The numerical goal

is an integral part of the sanctions imposed: it is a means of veri

fying whether petitioners have discharged their legal obligation

to eradicate the effects of prior discrimination and whether they

have thereby purged themselves of contempt.

3. Section 706(g) of Title VII arms courts with authority to

enter effective remedial orders which will work to achieve the

Act’s purposes. That authority includes the power to order pro

spective race-conscious remedies, such as the relief ordered in this

case, that extend benefits to individuals who are not necessarily

the identified victims of prior unlawful discrimination. The plain

language of Title VII, its legislative history and court decisions

confirm that courts possess authority to enter such orders.

This Court’s decision in Firefighters L oca l Union No. 1784 v.

Stotts, 104 S.Ct. 2576 (1984), is not to the contrary. It concerned

awards of retrospective, make-whole relief which affected the

seniority expectations of white workers while not advancing Ti

tle V II’s primary purpose of achieving equality of opportunity

and barring future racial discrimination. In contrast, the remedies

15

ordered here are prospective remedies which advance the primary

purposes of Title VII, do not implicate the seniority expectations

of other workers, and only minimally affect the interests of white

applicants and members of Local 28.

A rule that bars courts from granting prospective race-conscious

relief to individuals who have not been specifically identified as

the victims of the defendant’s unlawful discrimination disserves

the central purposes of Title VII “to achieve equality of oppor

tunity and to remove barriers that have operated in the past to

favor identifiable groups of white employees over other

employees.” Griggs v. D uke Power Co., 401 U.S. 424, 429-30

(1971). If the statute were interpreted to limit relief in all cases

to identified victims, employers or labor organizations bent on

avoiding the command of Tide VII would be encouraged to “bury

their dead” by discouraging submission of applications by in

dividuals of the unwanted race, sex, religion or national origin;

failing to retain applications submitted by those persistent enough

to complete and submit them; maintaining an informal, word-

of-mouth system of job referrals to which white workers, by vir

tue of familial and friendship ties, have greater access; and adop

ting a range of other schemes which assure perpetuation of ex

clusionary practices while minimizing identification of victims

of the discriminatory system. The facts of this case illustrate why

the application of inflexible; “victim-specific” strictures, which

petitioners and the Solicitor urge the Court to read into section

706(g), will undermine rather than foster the central purposes

of this historic legislation. Congress did not intend this result.

I. PETITIONERS’ CHALLENGES TO RULINGS

MADE A DECADE AGO ARE UNTIMELY

Petitioners challenge, inter alia, the district court’s original fin

dings of race discrimination, its imposition in the O&J and

RAAPO (now AAAPO) of race-conscious remedies, including a

29 % goal, and its establishment of the office of the administrator.

These rulings, made a decade ago, were twice affirmed by the

court of appeals. No review was sought in this Court within the

proper time limits and accordingly, these rulings are res judicata.

They may not be resurrected for review by petitioners’ challenge

1 6

to the court of appeals’ affirmance of the district court’s 1982

contempt finding.15

Petitioners failed to seek review in this Court of these deci

sions and they cannot do so now. Sup. Ct. R. 20 and 28 U.S.C. §

2101 require that certiorari be sought no later than ninety days

after entry of the Judgment to be reviewed. The 1976 and 1977

appeals finally determined all of the issues then in the case, in

cluding the finding of liability and the validity of the goal and

the office of the administrator. As this Court has stated, “the judg

ment. . . was final and appealable. Since [it was not appealed]

we cannot now consider whether the judgment was in error.” Boe

ing Co. v. Van Gem ert, 444 U.S. 472, 480 n.5 (1980); accord

Pasadena Board o f Education v. Spangler, 427 U.S. 424, 432

(1976).16

“ In any event, petitioners did not challenge below the determination of their

liability under H azelw ood School Dist. v. United States, 433 U.S. 299 (1977),

or the continuation of the administrator in office. For this reason alone, the

Court should not consider these issues. See Sol. Loc. 28 Br. at 17, 22, Brandon

v. Holt, 105 S.Ct. 873, 879 n.25 (1985); M onsanto Co. v. Spray-Rite Service

Corp., 465 U.S. 752, 759-61 n.6 (1984); Adickes v. S.H. Kress 6- Co., 398 U.S.

144, 147 n.2 (1970).

Petitioners erroneously contend that respondents “never questioned the ap

pealability” in the court of appeals of the issues of the legality of the goal and

the administrator, Pet. Reply Br. on the Pet. for Cert, at 7. The State argued

in the court of appeals that “the inquiry on appeal should be limited to [peti

tioners’] challenges to the specific remedial provisions ad d ed by the AAAPO.”

Brief for Plaintiff-Appellee State Division of Human Rights, at 33 (emphasis

added). See also Brief for the EEO C at 16. The court of appeals agreed that

its previous decisions in this case were reason enough to dispose of petitioners’

arguments concerning the goal and the administrator (A. 29, 31).

16 The denial of petitioners’ motion to terminate the O&J by the district court,

not appealed to the court of appeals, clearly is not before this Court. Brow der

v. Director, D ep’t o f Corrections, 434 U.S. 257, 264 (1978). In any event, the

motion to terminate did not revive petitioners’ right to challenge the finding

of liability, imposition of the goal or the office of the administrator. Although

res judicata does not apply when a motion to modify is made after a final judg

ment, Arizona v. California, 460 U.S. 605, 619 (1983), the moving party must

demonstrate sufficiently changed conditions of law or fact to warrant relief.

Id . at 624-25. Petitioners could not allege that the applicable statute, Title VII,

had changed since entry of the decree; System F ed ’n No. 91 v. Wright, 364 U.S.

(footnote continued)

17

Because the 1976 and 1977 judgments of the court of appeals

were final and review was not timely sought in this Court, res

judicata bars further litigation of all issues that were or could

have been decided by those judgments.17 As the Court succinctly

stated in Arizona v. California:

[Ljitigation proceeds through preliminary stages, general

ly matures at trial, and produces a judgment, to which, after

appeal, the binding finality of res judicata and collateral

estoppel will attach.

642 (1961), nor did they present any new factual circumstances justifying relief

from the judgment (A. 157). This Court’s decision in Stotts, 467 U.S. 561, does

not justify a modification of the judgment: Stotts did not change the interpreta

tion given Title VII, but merely applied existing law. See Point III, infra.

Moreover, even if Stotts had changed the decisional law interpreting Title VII,

petitioners could not use the decision as a basis for excusing their failure to ap

peal the 1976 and 1977 judgments as they were free, following the judgments,

to seek a ruling from this Court that race-conscious remedies were not permissi

ble. When they chose not to use that opportunity, the judgment became res

judicata.

Moreover, “modification is not a means by which a losing litigant can attack

the court’s decree collaterally.” 11 C. Wright & A. Miller, Federal Practice b

Procedure, § 2962 at 600-01 (1973); accord 7 J. Moore, M oore’s Federal Prac

tice 1 60.27[2] at 274 (2d ed. 1985) (Fed. R. Civ. P. 60(b) (6) “cannot be used

as a substitute for appeal. Absent exceptional and compelling circumstances,

failure to obtain relief through the usual channels of appeal is not another reason

justifying relief.”); M cKnight v. United States Steel Corp., 726 F.2d 333, 338

(7th Cir. 1984); House v. Secretary o f H ealth b Human Services, 688 F.2d 7,

9 (2d Cir. 1982). See System F ed ’n No. 91, 364 U.S. at 647-48; United States

v. Swift b Co., 286 U.S. 106, 119 (1932); Restatem ent (Second) Judgm ents §

73 at 197-98 (1982).

17 Even applying the more flexible law of the case doctrine, see IB M oore’s Federal

Practice f 0.405[2] at 188-90, the Solicitor agrees with the State that many of

the issues raised by petitioners may not be reviewed by this Court. See, e.g.,

Sol. Loc. 28 Br. at 16-17 (the 1975 liability finding) and Sol. Loc. 28 Br. at 21-22

(challenge to the administrator’s appointment and powers). The Solicitor’s logic

applies equally to review of the goal and other race-conscious relief affirmed

in 1976 and 1977. It was certainly forseeable when the race-conscious relief

was imposed in 1975 that failure to make real and substantial progress toward

the goal would be met with stern measures. There was thus no excuse for the

union’s failure to seek review of the race-conscious relief in 1976.

18

460 U.S. 605, 619 (1983).18 See also Federated D epartm ent Stores

v. M oitie, 452 U.S. 394, 398-99 (1981).

Further, “a contempt proceeding does not open to reconsidera

tion the legal or factual basis of the order alleged to have been

disobeyed and thus become a retrial of the original controversy.”

Maggio v. Zeitz, 333 U.S. 56, 69 (1948); accord United States v.

Rylander, 460 U.S. 752, 756-57 (1983). The Third Circuit has ex

plained the reasons for this rule:

If a civil contemnor could raise on appeal any substantive

defense to the underlying order by disobeying it, the time

limits specified in [the Federal rules] would easily be set to

naught [ , ] . . . presenting] the prospect of perpetual relitiga

tion, and thus destroying] the finality of judgments of both

appellate and trial courts.

H alderm an v. Pennhurst State School 6- H ospital, 673 F.2d 628,

637 (3d Cir. 1982) (en banc), cert, denied, 465 US. 1038 (1984).

The rule that a party may not relitigate in a contempt pro

ceeding an issue previously decided is simply an application of

ordinary res judicata principles. United States v. Secor, 476 F.2d

766, 770 (2d Cir. 1973) (“To permit such a collateral attack would

be to make a mockery of the well settled doctrine of res judicata!’).

See also Daly v. United States, 393 F.2d 873, 876 (8th Cir. 1968);

W orld’s Finest C hocolate Inc. v. World Candies, Inc., 409 F.

Supp. 840, 844 (N.D. 111. 1976), a ffd , 559 F.2d 1226 (7th Cir.

1977), and cases cited therein.

Petitioners attempt to avoid the application of res judicata by

citing cases permitting a party to challenge both a civil contempt 18

18 Arizona v. California, cited by the Solicitor in support of his contention that

res judicata is inapplicable here, actually supports the State’s view that the court

of appeals’ 1976 and 1977 judgments bar review of the matters resolved therein.

In Arizona v. California, this Court, in the exercise of its original jurisdic

tion, decided to apply res judicata principles rather than law of the case to

preclude relitigation of factual and legal issues long ago decided, even though

the decree involved was not final. 460 U.S. at 618-19; id. at 644 (Brennan ].,

concurring in part and dissenting in part).

19

finding and an underlying temporary restraining order or

preliminary injunction. Pet. Br. at 36, n.25. These cases are ir

relevant when a party violates an unappealed perm anent

injunction:

[W fhere, instead o f a tem porary injunction, a perm anent

injunction is violated, the interest in enforcem ent consists

not only o f the need to maintain respect fo r court orders

and fo r judicial procedures, but also o f the need to avoid

repetitious litigation. This latter interest, the interest which

the doctrine of res judicata serves in all of its applications,

militates in favor of barring collateral attacks upon perma

nent injunctions in civil contempt proceedings as well as

in criminal ones.

NLRB v. Local 282, International Brotherhood o f Teamsters, 428

F.2d 994, 999 (2d Cir. 1970) (emphasis added).19

The adjustment of the 29 % goal to 29.23 % in AAAPO by the

district court in August 1983 (A. 119), did not remove the issue

of the legality of the imposition of the goal from the reach of

res judicata. As the district court noted, “[t]he new goal of 29.23 %

essentially is the same as the goal set in 1975” (A. 123). Petitioners

may not avoid the effects of res judicata by challenging what

is essentially a reiteration of a prior order. FTC v. Minneapolis-

Honey w ell Regulator Co., 344 U.S. 206, 211-12 (1952); Class v.

Norton, 505 F.2d 123, 125 (2d Cir. 1974); Sidney v. Zah, 718 F.2d

1453, 1457 (9th Cir. 1983).

Nor may petitioners avoid the consequences of res judicata by

citing intervening decisional law, even from this Court:

[T]he res judicata consequences of a final, unappealed judg

ment on the merits [are not] altered by the fact that the

“ The district court’s retention of jurisdiction did not transform the O&J and

RAAPO into a non-final judgment and order, the provisions of which might

still be subject to review. See Special Project, T he R em edial Process in Institu

tional R eform Litigation, 78 Colum. L. Rev. 784, 846 (1978). The retention