Memorandum to Visiting Editors

Press Release

July 22, 1964

Cite this item

-

Press Releases, Volume 1. Memorandum to Visiting Editors, 1964. ef54971c-b592-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/350a7fb6-7807-4727-b29f-b0fd505b8d2b/memorandum-to-visiting-editors. Accessed February 20, 2026.

Copied!

* ee

a

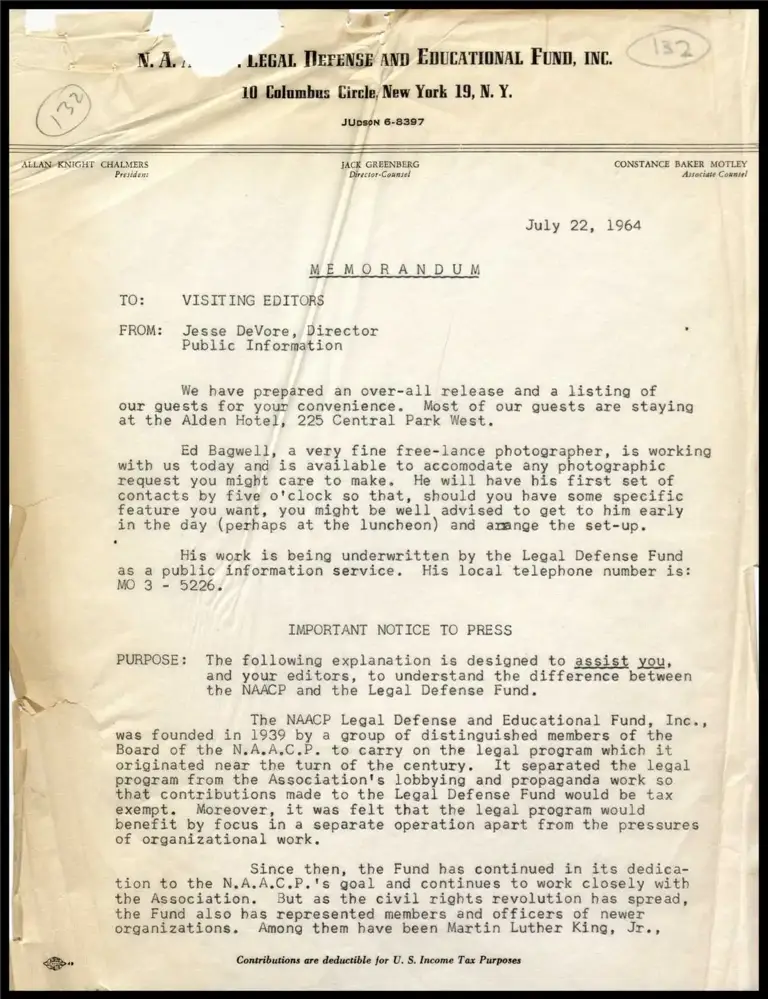

a "LEGAL Werense anp EDUCATIONAL FUNn, INC.

10 Columbus Circle, New York 15, N. Y.

JUDSON 6-8397

ALLAN-KNIGHT CHALMERS JACK GREENBERG CONSTANCE BAKER MOTLEY

Presiden: Director-Counsel Associate Counsel

July 22, 1964

MEMORANDUM

TO: VISITING EDITORS

FROM: Jesse DeVore, Director

Public Information

We have prepared an over-all release and a listing of

our guests for your convenience. Most of our guests are staying

at the Alden Hotel, 225 Central Park West.

Ed Bagwell, a very fine free-lance photographer, is working

with us today and is available to accomodate any photographic

request you might care to make. He will have his first set of

contacts by five o'clock so that, should you have some specific

3 feature you want, you might be well advised to get to him early

in the day (perhaps at the luncheon) and amange the set-up.

His work is being underwritten by the Legal Defense Fund

as a public information service. His local telephone number is:

MO 3 - 5226.

IMPORTANT NOTICE TO PRESS

x PURPOSE: The following explanation is designed to assist you,

" and your editors, to understand the difference between

the NAACP and the Legal Defense Fund.

5 The NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund, Inc.,

was founded in 1939 by a group of distinguished members of the

Board of the N.A.A.C.P. to carry on the legal program which it

originated near the turn of the century. It separated the legal

program from the Association's lobbying and propaganda work so

that contributions made to the Legal Defense Fund would be tax

exempt. Moreover, it was felt that the legal program would

benefit by focus in a separate operation apart from the pressures

of organizational work.

Since then, the Fund has continued in its dedica-

tion to the N.,A.A.C.P.'s goal and continues to work closely with

1 the Association. But as the civil rights revolution has spread,

] the Fund also has represented members and officers of newer

organizations. Among them have been Martin Luther King, Jr.,

&- Contributions are deductible for U. S. Income Tax Purposes

a

MEMORANDUM —— July 22, 1964

to Visiting Editors

James Farmer, James Forman, Fred Shuttlesworth, Ralph Abernathy,

and other officers and members of SCLC, CORE and SNCC. Moreover,

many persons represented by the Fund are members of ad hoc organi-

zations like the Albany Movement, or of no organization at all.

The only requirement that the Fund has for handling a case is

that the litigant have a bona fide civil rights claim. The

Board of Directors, staff, and budget of the Fund are independent

of those of any other civil rights group.