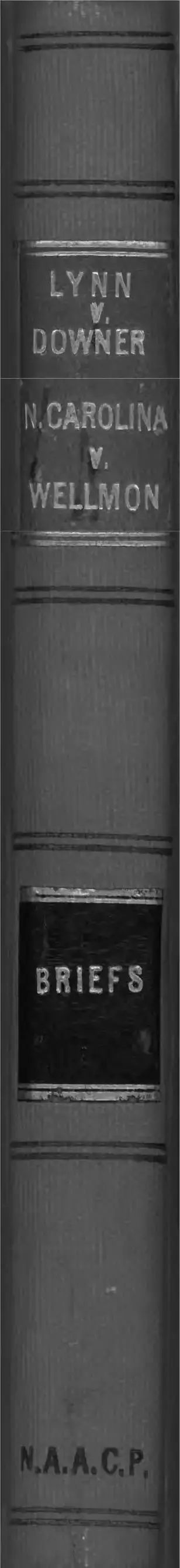

Lynn v Downer and State of North Carolina v. Wellmon Collection of Briefs

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1942 - January 1, 1943

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Lynn v Downer and State of North Carolina v. Wellmon Collection of Briefs, 1942. ae07c259-ca9a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/355387da-724f-4572-9845-93b0bc2f4f15/lynn-v-downer-and-state-of-north-carolina-v-wellmon-collection-of-briefs. Accessed February 23, 2026.

Copied!

It CAROLINA

V.

WELLMON

■r;vu::;Vv- />:;:>;?•; . - :ir^«i; - -; : SH \i:..;: Uii . ; A-:. i»K1 p B :?

:*£& SK? 5? : t K ^ - i ^ . .? 3sg! ? i gS « SKiiAî S*, i 5 g*Z&gSr*‘ **? ?$$? SS S:’ T::{:: t ? :K? ZH’i IK ;- Sr&fej* J v- 55£̂ S*l3bjS.̂

i-.i-̂ *Si'~?fir;KKKK>"-C|> >w•;Z:-■ ̂ r' - gffsrir- s K %K ^ r - l r ;|5**î K-K;--rrf̂ “ *̂s;n~'v̂ KK';-Ti-rK?̂ rTHVr;b‘t^j!.- -̂U“~ti*-£i,si.s?-iiv i'SJtX si£C£iS r -X ftlifi^Pl

-:•- r *- -'-• - : - : - - . is ■-..

lt^^>^Ut'H?fe^^g|^^pSsf^^^;jSSt.-^iSaSiS!:i>|^^^ t̂f ;̂s®25g2B .̂kK|iiitSi-aiSSrsi?gS!

w ^ a ^ S & g i g g ^ a aSBaa ^ ^ B B g a ^ W ' s c 3 v m M W & i * < ; ^ i S ; ^ i ^ ^ : : s ; ; c f f tf e a u = s ^ 5 a j ? B s s i :?s.;-;nl>:: HU- > iiivSSsgtjS^j:;

i f ! -sy

liissasaim m tejsss

• ■• ••

r’j* ‘ ' ‘ j : r\ x.- -J -‘ Vy --• } * b * h ± ? i . lV T i? : 'i? i* z±^;;; ; r« 7' riKf*- - ;i~ *•* v£- -" : -*s V - s s ^ s . ^ S t i - i T ir:7; - ‘ ■-; *• " ;- .*• fz", •;-. -.• ‘-.r-s.-.-Ajs

\

\

To be argued by

V in e H. S m ith

United i>tatro (Hirnrit (ta rt of Appeals

FOR THE SECOND CIRCUIT

C. C. A. #176

UNITED STATES OF AM ERICA, ea; rel. W INFRED

W ILLIAM LYNN,

Relator-Appellant,

against

COLONEL JOHN W. DOWNER, Commanding Officer of

Camp Upton, New York,

Respondent-Appellee.

BRIEF FOR COLONEL JOHN W . D O W N E R ,

RESPONDENT-APPELLEE

H arold M. K ennedy,

United States Attorney,

Eastern District of New York,

Attorney for Colonel John W . Downer.

V ine H. S m it h ,

F rank J. P arker,

Assistant United States Attorneys,

Of Counsel.

ITKAL PRINTING CO., INC., CEDAR ST., NEW YORK, WO 2-3242

m

m

I N D E X

PAGE

Statement ................................................................................ 1

Constitutional and Statutory Provisions ............... 2

Facts ...... 6

Point I .............................................................................r ..... 8

Relator has not proved that his classifica

tion, selection, and induction into the Army of

the United States were in any way affected by

reason of race or color, or that he was inducted

as part of a “ Negro quota.”

Point II ........................................ ...................................... 12

The induction routine of which relator com

plains involves no unlawful discrimination and

does not violate either the constitutional or

statutory rights of the men inducted.

Conclusion ....................................................... ...................... 20

Cases Cited

Brown v. Duchesne, 19 How. 183, 194 ............................. 14

Helvering v. N. Y. Trust Co., 292 U. S. 455, 464 ............ 14

U. S. v. Drum, 107 F. (2d) 897; cert. den. 310 U. S. 648 19

Inttefi §>tnt£B (Etrrutt Court of Appralo

FOR THE SECOND CIRCUIT

U nited S tates of A merica, ex rel. W in

fred W illiam L y n n ,

Relator-Appellant,

against

Colonel J ohn W. D owner, Commanding

Officer of Camp Upton, New York,

Respondent-Appellee.

BRIEF FOR COLONEL JOHN W . D O W N E R ,

RESPONDENT-APPELLEE

Numerals in parentheses refer to pages of the tran

script of record unless otherwise stated. All references

to exhibits are to relator’s exhibits unless otherwise

stated.

Statement

Relator appeals from an order of the United States

District Court for the Eastern District of New York,

made by Honorable Marcus B. Campbell, District Judge,

dated January 11, 1943, dismissing relator’s petition for

a writ of habeas corpus, quashing the writ issued pur

suant thereto, and remanding the relator, Winfred W il

liam Lynn, to the custody of the respondent, the Com

manding Officer at Camp Upton. The basis of the

proceeding is relator’s contention that his induction into

the Army of the United States, and the resulting military

2

custody and control of Ms person, were and are violative

of the Constitution of the United States, in particular,

the Fifth Amendment, and of the statutes, in particular,

the Selective Training and Service Act of 1940, as

amended, and the rules and regulations promulgated

thereunder, because, as relator alleges, the induction ordei

was applied to relator as a member of a “ Negro

quota” (6).

Notice of Appeal (2 );

Order appealed from (3 );

Writ of habeas corpus (4 );

Petition for writ of habeas corpus (5-8).

Constitutional and Statutory Provisions

The constitutional provision referred to in the petition

is the Fifth Amendment (6). Presumably, the reference

is to the portion of that amendment which provides that

no person shall “ be deprived of life, liberty, or property,

without due process of law.”

No violation of this clause or of any part of the Bill

of Eights, however, was urged at the hearing in the Dis

trict Court, and none is asserted in appellant’s brief in

this Court.

Further constitutional provisions which may properly

be noted in this connection are those which authorize

Congress to declare war and to raise and govern an

Army, viz. Article 1, Section 8, Clauses 11, 12 and 14, and

that which constitutes the President, the Commander-in-

Chief of the Army and Navy, Article 2, Section 2,

Clause 1.

The only statutory provision upon which the appellant

appears to rely is the clause forbidding discrimination

contained in Section 4 of the Selective Training and

Service Act of 1940, as amended December 20, 1941 (U. S.

3

Code, Title 50, Sec. 304; Animal Pocket Part 1942, p. 115-

116). The material portion of this Section which we

quote somewhat more fully than the appellant’s excerpt

(See Appellant’s Brief, p. 2) is as follows:

Sec. 304. M anner of S electing M en for T rain

ing and Service ; Quotas.

(a) The selection of men for training and

service under section 3 [section 303 of this appen

dix] (other than those who are voluntarily in

ducted pursuant to this Act) shall be made in an

impartial manner, under such rules and regulations

as the President may prescribe, from the men who

are liable for such training and service and who

at the time of selection are registered and classi

fied but not deferred or exempted: Provided, that

in the selection and training of men under this Act,

and in the interpretation and execution of the pro

visions of this Act, there shall be no discrimination

against any person on account of race or color:

Provided further, That in the classification of

registrants within the jurisdiction of any local

board, the registrants of any particular registra

tion may be classified, in the manner prescribed by

and in accordance with rules and regulations pre

scribed by the President, before, together with, or

after the registrants of any prior registration or

registrations: and in the selection for induction of

persons within the jurisdiction of any local board

and within any particular classification, persons

who were registered at any particular registration

may be selected, in the manner prescribed by the

President, before, together with, or after persons

who were registered at any prior registration or

registrations.”

4

We further call attention to the following portion of

the previous section of the same statute, Section 3 of the

Selective Training and Service Act of 1940 (U. S. Code,

Title 50, Sec. 303, 1942 Pocket Part, p. 114) which is, we

believe, material to the question involved herein:

“ Provided, That within the limits of the quota

determined under Section 4(b) [section 304(b) of

this appendix] for the subdivision in which he re

sides, any person, regardless of race or color, be

tween the ages of eighteen and forty-five, shall be

afforded an opportunity to volunteer for induction

into the land or naval forces of the United States

for the training and service prescribed in subsec

tion (b), but no person who so volunteers shall be

inducted for such training and service so long as

he is deferred after classification: Provided fur

ther, That no man shall be inducted for training

and service under this Act unless and until he is

acceptable to the land or naval forces for such

training and service and his physical and mental

fitness for such training and service has been satis

factorily determined: Provided further, That no

men shall be inducted for such training and service

until adequate provision shall have been made for

such shelter, sanitary facilities, water supplies, heat

ing and lighting arrangements, medical care, and

hospital accommodations, for such men, as may be

determined by the Secretary of War or the Secre

tary of the Navy, as the case may be, to be essential

to public and personal health: * * (Em

phasis ours.)

The Act of July 28, 1866 (10 U. S. C. 253, 282) pro

vides as follows:

5

“ 253. N egro R egiments. Enlisted men o f two

regiments of cavalry shall be colored men.

“ 282. N egro R egiments. Enlisted men of twm

regiments of infantry shall be colored men.”

The National Defense Act (Chapter 508 of the Statutes

of 1940; 54 Stat. 713; U. S. Code, Title 10, Section 621a)

provides as follow s:

“ No negro, because of race, shall be excluded

from enlistment in the Army for service with

colored military units now organized or to be

organized for such service.”

Regulations pertinent to the issue here presented in

clude the following sections of Selective Service Regula

tions, Second Edition (6 Fed. Reg. 6848, 7 Fed. Reg. 6516,

2092 and 5343):

“ 632.1 I nduction Calls by the D irector of

Selective S ervice. When the Director of Selective

Service receives from the Secretary of War or the

Secretary of the Navy a requisition for a number

of specified men to be inducted, he shall distribute

the number of specified men requisitioned among

the States to be called upon to furnish such men to

fill such requisition. He shall then issue a call on a

Notice of Call on State (Form 12) to the State

Director of Selective Service of each State con

cerned, sending two copies thereof to the Secretary

who issued the requisition. The State Director of

Selective Service, upon receiving such call, shall

confer with the Corps Area Commander (or repre

sentative of the Navy or Marine Corps) for the

6

purpose of determing the number of specified men

to be delivered, in order to actually induct a net of

the number of the specified men in such call, and

arranging the details as to the times when and the

places where such men will be delivered. (Em

phasis ours)

“ 632.2 I nduction Calls by the State D irector

of Selective Service, (a) After conference with

the Corps Area Commander (or representative of

the Navy or Marine Corps), the State Director of

Selective Service shall issue calls to local hoards to

meet the number agreed upon as necessary in order

to fill the State call. * * *

“ 632.3 Selection of M en to F ill I nduction

Call, (a) Each local board, when it receives a call,

shall select a sufficient number of specified men to

fill the call. It shall first select specified men who

have volunteered for induction. To fill the balance

of the call, it shall select specified men from such

group or groups as the Director of Selective Ser

vice may designate, provided that within a group

selection shall be made in sequence of order num

bers. * * *”

Facts

Relator, Winefred William Lynn, a citizen of the

United States and a Negro, duly registered under the

Selective Training and Service Act of 1940, as amended

(50 U. S. C. A. Sec. 301, et seq.). On August 7, 1942,

New York City Headquarters, Selective Service System,

issued call No. 29 to Local Board No. 261, Jamaica, Long

Island, for the period September 1, 1942, through Septem

ber 30, 1942, for “ the first 90 White men and the first 50

Negro men who are in 1-A,” which men were to report on

7

September 18, 1942 (55, Ex. 1). On September 8, 1942,

Local Board No. 261 mailed relator an order to report for

induction into the armed forces of the United States at

92-32 Union Hall Street, Jamaica, Long Island, at 7 :00

A. M. on September 18, 1942 (58, Ex. 3). Relator refused

to report for induction pursuant to this order (24) and

was subsequently indicted by the grand jury for the East

ern District of New York for failure to report for induc

tion under the Selective Training and Service Act of 1940,

as amended (26).1

A petition for a writ of habeas corpus to obtain the

release of relator from custody under the indictment on

the ground that he, a Negro, had been ordered to report

for induction under a call for Negro men was dismissed

by the Honorable Mortimer Byers, United States District

Judge, on December 4, 1942, in the District Court for the

Eastern District of New York (5, 27, 28). Thereafter,

relator Lynn reported for induction in response to an

order dated December 10, 1942, requiring him to report at

Local Board No. 261 at 9:00 A. M. on December 19, 1942

(56, Ex. 2). On December 19, 1942, relator was inducted

into the Army of the United States (5, 9, 44) and was

sent to Camp Upton, New York.1 2

The record discloses that relator was inducted as a

delinquent and not in response to any of the quota calls

issued prior to his induction (44, 45, 50, 51, 52, 53). De

linquents are inducted without regard to calls and without

any reference to race or color (43, 44). Beyond an in

dication that relator Lynn’s name may have appeared on

a Delivery List listing the names of selectees with nota

tions as to their race, there is no evidence which estab

1. The indictment was returned on November 10, 1942, according to the

records o f the District Court,

2. On December 23, 1942, the criminal case against relator was terminated

by the entry o f a nolle prosequi, according to the records o f the District Court.

8

lishes that relator was identified, treated, selected, or

inducted as a Negro (44). The record likewise fails to

disclose any evidence that relator’s classification, selec

tion, and induction into the Army of the United States

were in any manner affected by his being a Negro (37).

ARGUM ENT

POINT I

Relator has not proved that his classification, selec

tion, and induction into the Army of the United States

were in any way affected by reason of race or color,

or that he was inducted as part of a “ Negro quota.”

Elsewhere in this brief (Point II, Post) we shall show

that the practice of issuing specific quota requisitions in

volves no violation of either the constitutional or the

statutory rights of the men inducted into military service,

and that the induction routine of which such requisitions

are part is plainly lawful.

Before discussing that question, however, it is in order

to point out that the relator at bar has failed to show-

even that his own induction was effected pursuant to the

routine which he attacks, or that it was any part of the

practice which he undertakes to stigmatize as unlawful

discrimination.

1.

The petition for a writ of habeas corpus alleges that

relator is illegally restrained of his liberty because he

was inducted into the Army of the United States “ as a

member of a ‘ Negro quota’ ” (6). Relator, under his own

theory of the case, was therefore required to prove that

9

he was in fact inducted as a member of a “ Negro quota.”

The District Court found that relator failed to meet this

burden of proof (52).

In our statement of facts, preceding this portion of

our argument, the evidence disclosing the circumstances

of the relator’s induction into service has been sum

marized. A brief further reference to certain particularly

informing portions of the record will suffice to show not

only that the relator has not established his induction into

the Army pursuant to the practice which he assails, but

that, in fact, he has proved that he was not inducted un

der that practice.

The local board ordered him to report for induction

on September 18, 1942 (Ex. 3; 58-9). He did not obey

that order and was not inducted into service under it

(24-5). On the contrary, by reason of his failure to re

port for such induction on the day specified in the order

he became delinquent, and, according to the practice of

the local board regarding delinquents, he was permitted

to be inducted at any time thereafter, irrespective of his

color (43). He was, accordingly, inducted on December

19 pursuant to a further order which was issued without

any reference to White and Negro quotas (45). Relator’s

witness, John William Black, testified:

“ Q. Then he was inducted under a requisition

order for September, October, November or Decem

ber? A. Not necessarily. He was ordered to re

port under a requisition for September, but he did

not report. From there on he is a delinquent and

as soon as they get him they will take him in.

Q. He was inducted? A. He was.

Q. Under an order of the board? A. That’s

right.

10

Q. And the order of the board arranged for

the induction in response to a requisition from

your office asking for a certain number of Negroes

and a certain number of Whites! A. No, that re

quisition went out in August for delivery in Sep

tember. He did not go in until December.

Q. Didn’t those other requisitions read the same

way! A. Those are for other men.

Q. When he does show up, when do your records

show under what order he was inducted! A. No

particular order, they just show him as an inducted

man. He went in in December.” (45)

It is too clear to admit of plausible question that the

relator’s induction at the time and under the circum

stances disclosed by this evidence was not effected in

accordance with the quota clause of which he complains.

Since it was not, the military custody of his person fol

lowing his induction cannot be invalidated because of

the use of such a quota, even if that use had been un

authorized.

2.

Even if relator had sustained his allegation that he

was inducted as a member of a “ Negro quota,” this fact

alone would be immaterial. He would not have estab

lished that his own selection and induction were affected

in any way merely because of the existence of a “ Negro

quota.” For instance, relator has not proved that the

fact that he was a Negro and that there were “ Negro

quotas” had anything to do with the time when he was

called or inducted.

In any event, there is a total absence of any evidence

or probability that relator was inducted or directed to

report for induction ahead of men whose numbers were

11

lower than his own (37). Appellant’s counsel argues

(Appellant’s Brief, pp. 7-8) that the failure to show that

relator was called ahead of his turn in the draft lottery

is irrelevant. He contends that there is discrimination

as soon as it appears that by reason of his color he was

called either sooner or later than he would have been if

there had been no separate quota requisitions.

This argument, it is submitted, begs the question. It

is not discrimination—certainly not discrimination against

a registrant—if by reason of the induction practice he

was called at a time later than his turn. I f such was

the fact, it is obvious that if called in turn he would have

been in the custody of the Army sooner than he was. I f

relator’s grievance is that he was not called for induction

at an earlier date, there is no indication in the record that

relator in any way desired or attempted to enter the

armed forces at an earlier date or that he was prohibited

from volunteering for induction. In any event, upon what

possible basis can it be urged that it is unlawful for the

Army to have him now because the Army should have had

him sooner?

Appellant’s brief rings the changes loud and often

upon the relator’s claim of discrimination, but fails to

show anywhere how the observance of a diffeient practice

would have made the slightest difference in his present

status. He would have been as he is, in the Army, had

the induction practice been precisely what he claims it

should have been.

12

POINT II

The induction routine of which relator complains

involves no unlawful discrimination and does not vio

late either the constitutional or statutory rights of the

men inducted.

As we have seen (Point I, ante) the relator at bar was

not inducted pursuant to the routine involving Negro

quotas of which he complains. Nevertheless, we desire

to point out that the routine in question was and is clearly

legal and that the appellant’s criticisms of its use find no

support in the provisions of the statute upon which he

relies.

The calls of the Selective Service System for specified

(White or Negro) men are based on the requisitions for

“ specified” (White or Negro) men made on the Director

of Selective Service by the Secretary of War or the Sec

retary of the Navy. The Director then distributes the

number of “ specified” men to be inducted among the

several States in accordance with their proportion of

White and Negro registrants. (13, 14, 16, 18. Part 632,

Selective Service Regulations, Second Edition.) The Sec

retary of War and the Secretary of the Navy make sep

arate requisitions for White men and Negro men because

of the organization of the armed forces into White units

and Negro units and the need for specified men to fill

existing or new units in each category at acceptable times

and places and when “ adequate provision shall have been

made fo r” accommodating such specified men. (See pro

viso in Section 3 (a) of the Selective Training and Service

Act of 1940, as amended.)

This proviso of Section 3 (a) of the Act requires that

no man be inducted unless and until the Army has pro

vided adequate accommodations for the men requisitioned

13

and since separate accommodations and facilities are fur- ,

nished to White and Negro units separate Calls and

Delivery lists for induction become a necessary admini

strative detail by reason of this military organizational

separation. Major Francis V. Keesling, Jr., Legislative

Officer of the Selective Service System, in testifying on

May 6, 1942, before a Subcommittee on Appropriations of

the House of Representatives concerning the Department

of Labor—Federal Security Agency Appropriation Bill

for 1943, stated:

“ Mr. Chairman, the act (Selective Training and

Service Act of 1940) contains a provision that there

shall be no discrimination on account of race or

color. The act also has a provision that men will

not be taken into the Army until and unless facil

ities are available.

“ The Selective Sefvice System delivers men to

the Army in accordance with requisitions made

upon the System by the War Department. These

requisitions state specifically how many colored and

how many white selectees are to be delivered. We

have taken the position that it would be most inad

visable for the Selective Service System to deliver

men to the Army for induction whom we knew in

advance would be rejected.

“ To do otherwise would be an unnecessary ex

pense to the Government and a hardship on the

individuals concerned.” (Hearings Part 2, p. 1063)

1.

It is noted that appellant concedes (Appellant’s Brief,

pp. 13-14) that, once in the Army, men may be organized

into White and Negro units. But, counsel, nevertheless,

insists upon “ the narrow question whether, in the selec-

14

tion of men for service, they are to be chosen as American

citizens, or whether there are to be differences and dis

crimination in their selection, dependent upon race or

color.” (Appellant’s Brief, p. 14).

This is a “ narrow question” indeed. It is here con

ceded (as it must be in view of the legislative provisions

and history involved) that after induction separate White

and Negro units are lawful. As to that, the judgment of

the men responsible for producing an effective army.con

trols. But counsel, nevertheless, insists that an induction

routine calculated to supply men in conformity with the

contemplated army organization is forbidden. In other

words, the Army may decide its own needs, but in taking

its inductees it cannot take them as it needs them, or as it

is ready to use or accommodate them

This contention and the reading of the statute upon

which it is predicated are, it is submitted, plainly absurd.

Nothing in the statutory provision upon which appellant

relies justifies, much less requires, the holding that Con

gress in passing this Act intended to handicap the Nation

by precluding the orderly flow of men selected for mili

tary service into the Army for organization into the units

which the army executives concededly were authorized

to create.

Appellant’s reading of the statute violates the familiar

rule that in the construction of the language employed

by the legislature the court will examine “ the whole stat

ute (or statutes on the same subject) and the objects and

policy of the law, as indicated by its various provisions,

and give to it such a construction as will carry into execu

tion the will of the legislature as thus ascertained, ac

cording to its true intent and meaning.”

Brown v. Duchesne, 19 How. 183, 194;

Helvering v. N. 7. Trust Co., 292 IT. S. 455, 464.

15

For this rule, appellant’s interpretation of the statu

tory provisions involved in the case at bar would sub

stitute a requirement that the statute be read, if possible,

so as to frustrate or at least to handicap and retard the

accomplishment of the purpose which its enactment was

intended to promote. To say that the proviso forbidding

discrimination against any person prohibits an induction

practice essential to the lawful creation and maintenance

of army units is without support in precedent or reason,

and is opposed to the most obvious dictates of common

sense. Neither the language of the statute nor any rule

of construction requires an interpretation of this Act

which demands the impossible or the impractical.

The practice of issuing requisitions stating separately

the number of White men and the number of Negro men

to be called for induction from a particular district is

not “ discrimination against any person on account of

race or color,’ ’ within the meaning of the Selective Train

ing and Service Act. Such a practice was clearly author

ized as an incident of the right of the Army executives to

organize, the inductees in White and Negro units.

The interpretation of Section 4 (a) of the Act dealing

with “ discrimination” for which the appellant is strain

ing finds no support in the other provisos of the Act, the

adjudicated cases, or in the legislative history of the pro

vision in question. It is unthinkable that Congress in

forbidding discrimination against any person on account

of race or color intended a more sweeping use of the

term “ discrimination” than the scope thereof already

made familiar by judicial decisions relating to the Four

teenth Amendment.

2.

A review of the legislative history of the statutory

provision that there shall be no discrimination against

16

any person on account of race or color “ in the selection

and training of men” under the Selective Training and

Service Act of 1940, as amended, demonstrates that Con

gress did not intend to prohibit the calling of White and

Negro registrants in accordance with the needs of the

armed forces.

As a preliminary matter, it is important, we believe,

to note that Congress used the words “ selection and

training” together. If the making of separate White and

Negro quota calls to meet the requisitions of the armed

forces is invalid, it must follow that the separation of

inducted men in the armed forces into White and Negro

units is also invalid, since “ discrimination” is prohibited

in the “ training” of men as well as in their “ selection.”

The Selectve Training and Service Act of 1940 as

introduced into Congress contained no provision against

discrimination because of race or color. On August 23,

1940, Senator Wagner proposed an amendment providing

that any person, regardless of race or color, should be

afforded an opportunity to volunteer. (86 Cong. Eec. p.

10,789.) This amendment was adopted as part of Sec

tion 3 (a).

In the course of the debate in the Senate on the amend- -

ment offered by Senator Wagner to preclude discrimina

tion in accepting voluntary enlistments, the following ex

planation was given:

“ Mr. Overton. Mr. President, may I ask if the

complaint voiced in the letter the Senator from

New York has just read is so much concerned with

enlistment as it is with the desire of the colored

people that there should be established what is

known as mixed units in the armed forces?

“ Mr. Wagner. No; it has nothing to do with

that. They are refused enlistments altogether.

17

There is no question of whether they are to be in

tegrated or not. The complaint is against the re

fusal to permit them to serve. That is the only

point I am making.

“ Mr. Wagner. The Senator from Louisiana

may make that statement, but I think if he will

inquire he will find that in the aviation units no

colored enlistments at all are accepted. The colored

American citizen cannot enlist there; they will not

accept him; which is quite a different thing from

the question of segregation. That question I am

not considering at all.” (86 Cong. Rec. p. 10, 890).

The provision in Section 4 (a) of the Selective Train

ing and Service Act of 1940, as amended, against dis

crimination on account of race or color in the selection

and training of men under ” A'"L “ J +

gressman Fish on Septembe:

11,675). In describing the purpose of his amendment,

Congressman Fish stated that it was intended only to

afford to soldiers drafted for induction into the Army the

same assurance against discrimination which Senator

Wagner’s amendment provided for volunteers. (86 Cong.

Rec. 11,675.) It is clear that the amendment had no refer- j

ence to separate units or to the calling of registrants in

a manner made necessary by the existence of separate

units.

During the consideration of the Act, Congressman

Thomason of Texas included in his remarks a letter dated

August 31, 1940, from the Joint Army and Navy Selec

tive Sex-vice Committee (86 Cong. Rec. 11,427). This

letter informed Congress that the Selective Service pro-

*

introduced into the House

18

gram contemplated separate White and Negro quotas and

calls. Congressman Andrews of the Military Affairs

Committee stated on the floor of the House during the

consideration of the Fish amendment that the amendment

offered by Mr. Fish seeks to do what the War Department

already states it will do under regulations, that is, draft

one Negro out of every ten (men) who are called.” (86

Cong. Rec. p. 11,675 et seq.) It will be noted that Con

gressman Andrews was referring to the fact that Negroes

were to be called in accordance with their percentage of

the population. The records of the Selective Service

System disclose that this purpose has been carried out as

far as practicable.

The Army has been organized into separate units for

White and Negro men since at least 1866 {supra, pp.

4-5). Under the Selective Service Act of 1917 it was

the recognized and necessary practice to call White and

Negro registrants in accordance with the needs and requi

sitions of the Army. (See Second Report of Provost

Marshal General, p. 191.) These facts were known to the

members of Congress when the provision in question was

adopted. The same Congress in July, 1940, recognized

that the Army placed and would continue to place Negroes

in separate military units when it prohibited the exclusion

of Negroes because of race from enlistment in the Army

for service with “ colored military units” (10 TJ. S. C. A.

621(a), supra, p. 5). If Congress had intended to

prohibit the induction of White and Negro registrants in

the only practical manner possible in order to meet the

requirements from time to time of the armed forces, such

intention would, we believe, have been clearly expressed.

The fact that the Selective Training and Service Act has

been amended approximately fourteen times since Septem

ber 16, 1940, and has been almost continuously a matter of

searching inquiry by Congress and the fact that Congress

19

has never questioned the manner of selecting and calling

White and Negro registrants are further evidence that

Congress considers its intentions are not being violated.

(See statement of Major V. Keesling, Jr., before House

Subcommittee, supra, p. 13.)

3.

It is our duty, we believe, to point out that if the

existence of separate calls for White and Negro regis

trants to meet the requisitions of the armed forces is

invalid and if all registrants, White or Negro, inducted

under such calls are illegally in the armed forces, and

subject to release by the courts under writs of habeas

corpus, the security of the country is in peril). That the

courts will not construe a draft act in such a manner,

where no individual substantial prejudice is established,

was announced as follows by this court in United States

v. Brum, 107 F. (2d) 897, cert, denied 310 U. S. 648:

“ Such rights (the rights of the individual)

deserve adequate protection. They do not call for

an overtechnical construction of the regulations not

necessary for such protection and merely hampering

to the Government in its tremendous task of mobiliz

ing its man power into an effective fighting organ

ization for the military service which the country

had decided upon.” (Opinion 107 F. (2d) at 900.)

20

CONCLUSION

The order appealed from should be affirmed.

Respectfully submitted,

H arold M. K ennedy,

United States Attorney,

Eastern District of New York,

Attorney for Colonel John W. Downer.

V ine H. S m ith ,

F rank J. P arker,

Assistant U. S. A ttorneys,

Of Counsel.

UNITED STATES CIRCUIT COURT OF APPEALS

F or th e Second Circuit

No. 176— October Term, 1943.

(Argued December 8, 1943 Decided February 2, 1944.)

United States of A merica, ex rel., W infred W illiam Ly n n ,

Relator-Appellant,

— vs.—

Colonel J ohn W. D owner, Commanding Officer of

Camp Upton, New York,

Respondent-Appellee.

B e f o r e :

Sw a n , A ugustus N. H and and Clark ,

Circuit Judges.

Appeal from the District Court of the United States for the

Eastern District of New York.

Habeas corpus proceeding to test the legality of the

relator’s induction into the United States Army. The rela

tor appeals from an order quashing the writ and remanding

him to the custody of the respondent. Affirmed.

Conrad J. Ly n n , A lbert C. G ilbert and H ays,

St . J ohn , A bramson & Sch u lm a n , for ap

pellant; Arthur Garfield Hays, Albert C.

Gilbert and Gerald Weatherly, of counsel.

H arold M. K ennedy, United States Attorney,

for respondent; Vine H. Smith and Frank

J. Parker, Assistant United States At

torneys, of counsel.

761

The appellant, a Negro, is a citizen of the United States

who was inducted into the Army on December 19, 1942.

He waived furlough and was sent immediately to Camp

Upton at which the respondent, Col. Downer, is the com

manding officer. By petition for a writ of habeas corpus

the appellant sought release from the Army on the ground

that he was inducted “ as a member of a ‘Negro quota’ ”

in violation of the provision of the Selective Training and

Service Act of 1940, 50 USCA Appendix §304(a ), pro

hibiting “discrimination against any person on account of

race or color” . The respondent made return to the writ,

alleging that the appellant was held as a soldier iu the

Army, having been lawfully selected for service and duly

and regularly inducted. By traverse to the return the ap

pellant reasserted that he was unlawfully selected for in

duction into the armed forces as a member of a Negro

quota. After a hearing, the district court quashed the

writ and dismissed the petition for failure of proof.

The record discloses the following: The appellant duly

registered under the Selective Service Act with Local Board

No. 261, Jamaica, Long Island. He received from his local

board an order dated September 8, 1942 to report for in

duction on September 18th. This order was issued pur

suant to a requisition by the New York City Director of

Selective Service which informed Local Board No. 261

that “Your Quota for this Call is the first 90 White men

and the first 50 Negro men who are in Class 1A »

Separate Delivery Lists (Form 151) are to be made for

the White and Negro registrants delivered.” The New

York City Director testified: “We receive ^requ isition

from the government for so many white men and so many

colored men for indnction each month and then we

Swan, Circuit Judge:

762

break that list down among the local boards and that is

on a proportionary basis and each board will be called upon

to produce so many whites and so many Negroes for in

duction.” 1 Desiring to contest the validity of the induc

tion order based on the above-mentioned requisition, the ap

pellant failed to report for induction on September 18th.

By such failure he became a delinquent. Under section 11

of the Act, 50 USCA Appendix §311, he was indicted for

disobedience of the induction order. Thereafter his lawyers

advised him that in order to raise the question of dis

crimination he must go into the Army, and the local board

was informed that he was ready to go. It issued an order

dated December 10, 1942, requiring him to report for in

duction on December 19, 1942. This order he obeyed. He

was thereupon inducted and sent to Camp Upton for train-

ing. The testimony is to the effect that he was inducted as

a delinquent and that a delinquent will be inducted “with

out any quota call” and without reference to his race or

color. It further appears that requisitions were made upon

Local Board 261 calling for 117 whites and 103 Negroes in

October, 134 whites and 100 Negroes in November, and

174 whites and 97 Negroes in December; but that these

requisitions related to men other than the appellant. The

trial judge ruled that the relator had not proved that “he

1 This practice apparently conforms with the Selective Service

Regulations, 2d edition, 6 Fed. Reg. 6848; 7 Fed. Reg. 2092, 5343,

6516; Sec. 632.1 Induction Calls by the Director of Selective Ser

vice; Sec. 632.2 Induction Calls by the State Director of Selective

Service; Sec. 623.3 Selection of Men to Fill Induction Call, “ (a)

Bach local board, when it receives a call, shall select a sufficient

number of specified men to fill the call. It shall first select

specified men who have volunteered for induction. To fill the

balance of the call, it shall select specified men from such group

or groups as the Director of Selective Service may designate, pro

vided that within a group selection shall be made in the sequence

of order numbers. * * * ”

763

was inducted under any order which calls for so many

whites and so many colored,” and therefore had not suc

ceeded in raising1 the question which the habeas corpus

proceeding was intended to present for decision.

If the appellant was inducted as a delinquent, he be

came delinquent by refusal to obey the September induc

tion order which was issued pursuant to the requisition

for 90 whites and 50 Negroes for induction in September.

Hence the requisition was a direct cause of his induction

into the Army and constituted, we believe, sufficient proof

of the allegation in his petition that he was inducted as

“a member of a Negro quota.”

The appellee argues that even if this be true, the record

is barren of any evidence that the appellant was inducted

or directed to report for induction ahead of men whose draft

numbers were lower than his own, and therefore there is

no proof of discrimination against him on account of race

or color.” To this appellant’s counsel replies that the

existence of separate quotas for whites and Negroes makes

it incredible that he was called for induction precisely in

his turn under the draft; and that there was discrimina

tion against him if he were called either sooner or later

than would have happened in the absence of separate quotas.2

If the appellant was called for induction later than his turn,

his grievance seems to be that the military custody in which

he now finds himself should have begun at an earlier date.

But how does the fact that the Army should have had him

sooner make unlawful its having him now? Delay in

calling him may have resulted in discrimination against

2 Counsel cites Selective Service Regulations 2d ed., Sec. 623.1(c)

reading as follows: “ (c) In classifying a registrant there shall

be no discrimination for or against him because of his race, creed,

or color, or because of his membership or activity in any labor,

political, religious, or other organization. Each registrant shall

receive equal and fair justice.”

764

others who were called ahead of their turn, but we find it

difficult to regard it as a discrimination making illegal the

Army’s present custody of him. Even if the induction

practice had been conducted without separate quotas, as

he claims it should have been, he would now be, as he is,

in the Army. In f a i l i n g to prove that the requisition under

which he was called for induction resulted in calling him

ahead of his turn in the draft, a majority of the court be

lieves that the petition was properly dismissed for failure

of proof that he was aggrieved by the discrimination, if any

there was.

But the dismissal may also be sustained on broader

grounds which we are inclined to discuss, since the parties

have thoroughly briefed and argued the question of statutory

construction and the question is an important one.

In arguing that the practice of calling for specified num

bers of whites and Negroes for induction during a given

month is contrary to the statute, the appellant relies upon

the following language in section 4, 50 USCA Appendix

§304:

“ (a) The selection of men for training and service

under section 3 [section 303 of this appendix] (other

than those who are voluntarily inducted pursuant to

this Act) shall be made in an impartial manner, under

such rules and regulations as the President may pre

scribe, from the men who are liable for such train

ing and service and who at the time of selection are

registered and classified but not deferred or exempted:

Provided, That in the selection and training of men

under this Act, and in the interpretation and execu

tion of the provisions of this Act, there shall be no

discrimination against any person on account of race

or color; * * * ”

765

In interpreting and applying this language the Army’s his

tory of separate regiments of whites and Negroes must not

be overlooked. Indeed, the appellant does not contend, and

could not successfully do so, that after selectees are law

fully inducted under the Selective Training and Service

Act of 1940 they may not be segregated into white and

colored regiments. Since July 28, 1866 federal statutes

have made provision for separate Negro regiments. 14 Stat.

332. And the same Congress which enacted the Selective

Training and Service Act in September 1940 had passed in

July of that year section 2(b) of the National Defense A ct

which is printed in the margin.8 Also relevant to inter

preting the language under discussion are provisions in

section 3 (a ), 50 USCA Appendix §383(a), to the effect that

the men inducted into the land and naval forces shall be

assigned to camps or units of such forces for training and

service, and that no men shall be inducted until adequate

accommodations for them have been provided.3 4 Reading

3 54 Stat. 713: Sec. 2. “ (b) The President may, during the fiscal

year 1941, assign officers and enlisted men to the various branches

of the Army in such numbers as he considers necessary, ir

respective of the limitations on the strength of any particular

branch of the Army set forth in the National Defense Act of

June 3, 1916, as amended: P r o v id e d that no Negro, because of

race, shall be excluded from enlistment in the Arm y for service

with colored military units now organized or to be organized for

such service.”

4 So far as material, §303(a) reads as follows:

“ * * * P r o v id e d , That within the limits of the quota deter

mined under section 4(b) (section 304(b) of this appendix) for

the subdivision in which he resides, any person, regardless of race

or color, between the ages of eighteen and forty-five, shall be

afforded an opportunity to volunteer for induction into the land

or naval forces of the United States for the training and service

prescribed in subsection (b ), * * * P r o v id e d fu r th e r , That no

man shall be inducted for training and service under this Act

unless and until he is acceptable to the land or naval forces for

such training and service and his physical and mental fitness for

such training and service has been satisfactorily determined:

766

the Act as a whole and in the light of the Army’s long es

tablished practice of segregating enlisted men into separate

white and colored units, we believe that requisitions calling

for a specified number of whites and a specified number of

Negroes for induction during a given month and based on

relative racial proportions of the men registered with a

local board and subject to call for induction, is a necessary

and permissible administrative procedure, and the regula-

tlonJ which sanction it5 are notviolative of the Act. The

induction routine that has been established is calculated

to supply men in conformity with the contemplated military

organization which permits separate colored regiments.

The Army executives are to decide the Army’s needs, to

provide accommodations and facilities for selectees and

to induct them only when camps or units are ready to re

ceive them. To hold that the provision in section 4 for

bidding discrimination invalidates such induction routine

• would frustrate, or at least impede, the development of

an effective armed force, the prompt creation of which was

the very purpose and object of the Act.

Nothing requiring this result is to be found in the legis-

lative history of the Selective Training and Service Act

of 1940. As originally introduced the bill contained no

provision forbidding discrimination on account of race or

color. On August 23rd Senator Wagner proposed the

amendment, which was incorporated into section 3, to the

P r o v id e d fu r th e r , That no men shall he inducted for such train

ing and service until adequate provision shall have been made

for such shelter, sanitary facilities, water supplies, heating and

lighting arrangements, medical care, and hospital accommoda

tions, for such men, as may be determined by the Secretary of

W ar or the Secretary of the Navy, as the case may be, to be

essential to public and personal health: * * * The men inducted

into the land or naval forces for training and service under this

Act shall be assigned to camps or units of such forces: * » * ”

5 See note 1, su p ra .

767

effect that any person regardless of race or color shall be

afforded an opportunity to volunteer.6 In debate he ex

plained that this had nothing to do with segregation into

white or colored military units.7 The provision against

discrimination which appears in section 4 was proposed by

Congressman Fish on September 6th. His amendment, he

stated, was intended to afford to soldiers drafted for in

duction into the Army the same assurance against dis

crimination that Senator Wagner’s amendment provided

for volunteers.8 During consideration of the Fish amend

ment Congressman Andrews of the Military Affairs Com

mittee informed the House of Representatives that the

amendment seeks to do what the War Department already

states it will do under regulations, namely, call Negroes for

induction in accordance with the ratio they bear to the

population.9 And Congressman Thomason of Texas in

cluded in his remarks during the consideration of the Act

a letter from the Joint Army and Navy Selective Service

Committee which informed Congress that the selective ser

vice program contemplated separate white and Negro quotas

and calls.10

If the Congress had intended to prohibit separate white

and Negro quotas and calls we believe it would have ex

pressed such intention more definitely than by the general

prohibition against discrimination appearing in section 4.

Moreover, it is not without significance, we think, that the

induction procedure which has been established has never

been altered by congressional action, although the Act has

been often amended since its original enactment. In our

6 86 Cong. Rec. p. 10,789.

7 86 Cong. Rec. p. 10,890.

8 86 Cong. Rec. p. 11,675.

9 86 Cong. Rec. p. 11,676.

10 86 Cong. Rec. p. 11,427.

768

opinion the statutory provisions which the appellant in

vokes mean no more than that Negroes must be accorded

privileges substantially equal to those afforded whites in

the matter of volunteering, induction, training and service

under the A ct; in other words, separate quotas in the requisi

tions based on relative racial proportions of the men sub-

ject to call do not constitute the prohibited “ discrimina

tion” . Compare cases dealing with discrimination claimed

to be repugnant to the Fourteenth Amendment. Plessy v.

Ferguson, 163 U. S. 537; Gong Lum v. Rice, 275 U. S. 78;

Missouri ex rel. Gaines v. Canada, 305 U. S. 337. Judgment

affirmed.

Clark , Circuit Judge (dissenting) :

In a case of this kind, with such serious social implica

tions, it seems to me peculiarly desirable that judges shall

confine themselves to the legislative intent to the utmost

extent possible. Here that intent does not seem to me

disputable on the words of the statute itself; but if any

doubt exists, I think it must be dispelled by a consideration

of the legislative history. The statute presents a closely

integrated system of selection of fit registrants according

to state and local quotas based on the number of available

men, with an overriding prohibition against any discrimina

tion in selection for race or color; and the history of this

prohibition shows just how overriding it was intended to be.

In stating the legislative history, the opinion stresses the

fact that segregation had previously existed in the Army

and that the Wagner and Fish amendments to the Selective

Training and Service Act were made in the light of that

fact. It argues, therefore, that the amendments, following

cases dealing with discrimination claimed to be repugnant

769

to the Fourteenth Amendment, require only equal, even if

separate, treatment of Negro inductees while in the Army.1

All that can be accepted without reaching our conclusion;

that requires the further step which overlooks the expressed

purpose of the proponents and nullifies the provision that

in the selection of men for induction there shall be no

discrimination against any person on account of race or

color.

Thus, Senator Wagner explained his amendment as not

an attempt to control the Army after it received the selectees,

but a requirement of:' equal opportunity to serve; and he

presented a letter from the Secretary of the National As

sociation for the Advancement of the Colored People asking

for the amendment because Negroes had been allowed to

enlist only in certain specified regiments. 86 Cong. Rec.

10,789, 10,889. This amendment—which is not the im

portant one here and which was passed only after long de

bate and determined opposition mainly on the ground that

it was unnecessary, 86 Cong. Rec. 10,888-10,895—thus con

cerned the important matter of choice of men for the Army.

When the matter came up later in the House, the Fish

amendment was supported to make assurance sure and to

quiet the doubts of representatives of the colored people.

Again there was a sharp debate, not in opposition to the

principle expressed, but on the ground that the provision

was unnecessary, as already incorporated in that Act.

Congressman Fish said he was not the originator of the

amendment, but sponsored it by request of a group of

prominent colored leaders “who are interested in and repre

sent the interests of 11,000,000 Negroes in America.” 86

1 Referring to this case, Professor Robert E. Cushman, in S o m e

C o n stitu tio n a l P r o b le m s o f C ivil L ib e r ty , 23 B. U. L. Rev. 335,

361, makes this same point of “the general policy of segregation”

upheld in P le s s y v. F e r g u so n , 163 U. S. 537; but he does not dis

cuss the question of discrimination in s e le c tio n .

770

Cong. Eec. 11,675, 11,676. And so at length after one vote

wherein the amendment appeared to he lost, it finally passed

the House by a fairly close vote, 86 Cong. Rec. 11,680, and

remained in the bill at all times thereafter.

In this debate on the Fish amendment, the Committee

on Military Affairs, which had reported the bill, opposed

the change. The Army letter to Congressman Thomason of

Texas, 86 Cong. Rec. 11,427, seems to me of quite a different

tenor than as stated in the opinion f but the intimation it

contained that estimates of registrants were being made

according to color may be one of the things which led to

disquietude upon the part of the colored people and to the

proposal of the amendment two days later. It is significant,

too, that Chairman May of the Committee on Military A f

fairs, in opposing the amendment as unnecessary, reported

that the Committee was adopting two provisions adequate to

cover the matter—one the Wagner amendment to the Senate

bill, and the other the proviso to §3(a) quoted in the

opinion that no man should be inducted until he was ac

ceptable to the land or naval forces. Then he explained

that this proviso was not to be used to permit discrimina

tion by the clear statement: “That latter provision merely 2

2 Tlie letter does not mention separate white and Negro quotas

and calls; it does, however, attempt an estimate of the number

of registrants, and, taking Texas, as an example, considers

separately the white and Negro population and the white and

Negro persons already serving in the Army. So far as appears,

this method of estimating may be required by the nature and

form of the available statistics.

It is easy to slip from the discrimination here, which is based

solely on Arm y calls for men, to that stated at the end of the

opinion, viz., “separate quotas in the requisitions based on rela

tive racial proportions of the men subject to call.” Whether or

not that would violate the quota provisions of §4 (b ), it is obvious

that such a system, substantially following population trends, is

more likely to come closer to calling the Negroes in their proper

turn than does the one actually employed. The same is true of

induction of Negroes “in accordance with the ratio they bear to

the population,” also referred to in the opinion.

771

means that he must stand the same kind of medical ex

amination and physical test as any other man, regardless

of race, color, or condition.” 86 Cong. Rec. 11,676. The other

similar proviso, also quoted from the same statute, that

no man should be inducted until adequate sanitary and other

facilities were available had just been adopted that same

day after similar considerable debate as to its necessity

and expressly to meet the condition asserted to have ob

tained in the First World War when men were said to have

been inducted only to become sick or die because of lack

of adequate sanitary and other facilities. 86 Cong. Rec.

11,670.

It seems hardly doubtful that these provisos added to

§3(a) are but the protection thought necessary for the

inductees and were not intended, and should not be con

strued, to nullify the anti-discrimination (Fish) amend

ment to the next section, §4(a), which in terms refers to

and conditions the earlier section thus, “ The selection of

men for training and service under section 3 * * * shall be

made in an impartial manner * * * : Provided, That in the

selection and training of men under this Act, and in the

interpretation and execution of the provisions of this Act,

there shall be no discrimination against any person on ac- ,

count of race or color.” (Italics added.) And the Wagner

amendment to §3(a) itself refers forward to and depends

upon “the limits of the quota determined under section 4(b)

for the subdivision in which he resides.” Thus, all parts

of the statute must be read together and the provision

against discrimination in selection for color must be given

meaning. In fact, I find it difficult to think of more apt

language to express the Congressional intent; the sugges

tion that Congress should have said something more, or

amended the statute, means in effect that it should be watch

ful to see how a statute is violated and then expressly nega

tive such violation or be assumed to sanction it.

772

Now it seems to me that the result stated in the opinion

simply wipes out this provision so insisted upon as assur

ance to prevent this very result. For it is not seriously

contested that white and colored draftees are not called ac

cording to their officially determined order numbers (es

tablished originally by the much publicized drawing from

the gold fish bowl in Washington and later by similar im

partial chance), but only according to the calls of the Army

officials separately for whites and for Negroes. The dis

location occasioned by a single such separate call, intensi

fied as these calls are repeated throughout the history of

the draft, was frankly admitted by Colonel Arthur V.

McDermott, the New York City Director of Selective Ser

vice, who testified below. He said: “ I will repeat— Gen

erally speaking, both Negroes and whites are called ac

cording to their order numbers, but if the number of Negroes

called is less than the number of whites called, then after

the Negro quota has been filled, drawing by order numbers,

then the board would proceed according to order numbers,

but skipping the Negroes.” To the question, “ Then you do

have a Negro quota and a white quota?” he answered, “ Oh,

yes.” And to the question, “Am I not right in my state-

ment"that Negroes and white men are not called in turn

or serially, but that the question of color has something to

do with the time they are called?” he answered, “ That’s

right.” This well-understood practice has led to rather

bitter comment recently in Congress, where Congressman

McKenzie of Louisiana has pointed out the disruption of

a community caused by the taking of pre-Pearl Harbor

white fathers, while single available Negroes are left un

called. 89 Cong. Rec. A-5268, A-5269.3

3 The Congressman quotes from a Louisiana newspaper a statement

that from a certain parish in that State there have been called for

military service a group of men with pre-Pearl Harbor children,

while 267 Negro single men remain on the Class 1-A list, and

that both white and Negro citizens are disturbed by the dis

crimination.

773

Law Brief Press— NYC

IN THE

Caprone <£mu‘t of to Btixtix

October Term , 1943

No.

U nited States of A merica ex rel. W infred

W il l ia m L y n n ,

Petitioner,

— against—

Colonel J ohn W. D owner, Commanding Officer

-ad Camp Upton, New York,

Respondent.

PETITION FOR A W RIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE

UNITED STATES CIRCUIT COURT OF APPEALS FOR

THE SECOND CIRCUIT AND BRIEF IN SUPPORT

THEREOF

A rthur G arfield H ays,

G erald W eatherly,

Counsel for Petitioner.

Conrad J. L y n n ,

A lbert C. G ilbert,

On the Brief.

I N D E X

PAGE

Petition for Writ of Certiorari.................................... 1-7

Statement of Matter Involved .................................... 1-4

F a c ts ........................................................................... 2-3

Opinions Below ...................................................... 4-5

Jurisdiction ..................................................................... 5,9

Questions Presented ....................................................... 5

Statutes and Regulations.............................................. 2, 23-24

Reasons for Granting W r i t .......................................... 5-6

Certification of Merit .................................................... 7

Brief in Support of P etition ........................................ 9-24

Statement of Case .......................................................... 9

Summary of Argum ent.................................................. 9

Point I

The selection and induction of Petitioner pur

suant to the Negro quota requisition, in conjunc

tion with the separate Negro delivery list, was

discrimination against him on account of race or

color and in violation of the statute.................. 10-20

Point II

The judgment of the Circuit Court of Appeals

should be reversed, and Petitioner should be dis

charged ..................................................................... 21

A rgument ................................................................................ 10-20

Conclusion .............................................................................. 20

A ppendix .................................................................................. 23-24

2

he was selected and inducted under a “Negro quota,” in

violation of the “no discrimination” provision of the Selec

tive Training and Service Act of 1940 (50 U. S. C. A.

App. Sec. 304 [a ]). The opinions in the Circuit Court of

Appeals appear in the Record at pages 63-74, folios 64-77,

and are reported in 140 F. 2d 397.__

The Statutes and Regulations.

The portion of the statute involved in this application

(50 U. S. C. A. App. Sec. 304 [a ]), reads as follows:

“ * * * In the selection and training of men under this

Act, and in the interpretation and execution of the pro

visions of this Act, there shall be no discrimination

against any person on account of race or color.”

Selective Service Regulations (2d ed.) Sec. 623.1, read,

so far as material, as follows:

“ (c) In classifying a registrant there shall be no dis

crimination for or against him because of his race,

creed, or color, or because of his membership or activity

in any labor, political, religious, or other organization.

Each registrant shall receive equal and fair justice.”

The Facts.

Relator-appellant is an American citizen and a Negro

(R. 23, fol. 68). He duly registered under the Selective

Service Act of 1940. He received an order to report for

induction on September 18, 1942 (Relator Exhibit 3; R. 58,

fol. 172; R. 23-24, fols. 68-71). That order was made pur

suant to the requisition for induction of August 7, 1942,

which appears as Relator Exhibit 1 (R. 55, fol. 163. Cf.

R. 45, fol. 134; R. 22-23, fols. 66-67; R. 55, fol. 164; R. 58,

fol. 174; R. 24, fols. 70-71). That requisition called on

3

Local Board No. 261, setting forth its quota “ for this call”

as “ the first 90 white men and the first 50 Negro men who

are in Class 1-A.”

The method which led to Lynn’s induction is clear from

the testimony of Col. Arthur Y. McDermott, New York City

Director of Selective Service, who said (R. 13-14, fols.

39-40) :

“We receive a requisition from the government for

so many white men and so many colored men for induc

tion each month and then we break that list down

among the local boards and that is on a proportionary

basis and each local hoard will be called upon to pro

duce so many whites and so many Negroes for induc

tion.”

Col. McDermott further testified that men ordinarily were

taken in their turns, but that there was an exception in

case of Negroes and whites (R. 15, fols. 43-44). There was

“a Negro quota and a white quota” (R. 16; fol. 46). There

was also “ a separate delivery list” (R. 14; fol. 41).

The facts” are clear from the categorical testimony of

Col. McDermott (R. 16, fol. 46) :

“ * * * you do have a Negro quota and a white quota?

A. Oh, yes.”

Also at R. 17, folio 51:

“ Colonel, am I not right in my statement that Negroes

and white men are not called in turn or serially, but

that the question of color has something to do with the

time they are called? A. That’s right.”

The issue was clearly stated by the trial court (R. 32;

fol. 96) :

“ The petition raises the issue fairly enough, whether

or not he was sent under a Negro quota, and if he

4

was they contend that is not in accordance with the

law and the Constitution.”

The Opinions Below.

The majority of the Circuit Court of Appeals, Mr. Justice

Swan and Mr. Justice Augustus Hand, held “that requisi

tions calling for a specified number of whites and a specified

number of Negroes for induction during a given month and

based on relative racial proportions of the men registered

with a local board and subject to call for induction, is a

necessary and permissible administrative procedure, and the

regulations which sanction it are not violative of the Act”

(R. 68; fol. 69).

Mr. Justice Clark, dissenting, held that the language and

history of the Statute forbade this procedure, adding (R.

72; fol. 74) :

“ * * * In fact, I find it difficult to think of more apt

language to express the Congressional intent; the sug

gestion that Congress should have said something more,

or amended the statute, means in effect that it should

be watchful to see how a statute is violated and then

expressly negative such violation or be assumed to sanc

tion it.”

In answer to the alleged practical difficulties which it is

said might arise if petitioner’s position were upheld. Judge

Clark said (R. 74; fol. 76) :

“ * * * This registrant asserts his desire to serve and

his willingness to do so if inducted according to law.

I think it unsound to overlook a violation of law as to

him on a premise which we ourselves would reject as

patriotic citizens and which is contrary to the whole

spirit of the Act, namely, that avoidance of service is

5

to be desired. But notwithstanding the fears expressed

by the United States Attorney, this cannot mean the

release from the Army of large numbers of soldiers;

alike with volunteers, those who have gone into service

properly without immediately raising any objections

they have, and relying upon them as steadfastly as did

this registrant here, surely have no ground to approach

the court.”

Jurisdiction.

The Jurisdiction of this Court is invoked under Section

240 (a) of the Judicial Code as amended by the Act of

February 13, 1925, c. 229, §1 (43 Stat. 938), 28 U. S. C. A.

§347 (a). The judgment of the Circuit Court of Appeals

was entered February 21, 1944 (R. 75).

Question Presented.

1. Whether, consistently with the “no discrimination”

provision of the statute, Negro American citizens can be

selected and inducted, not strictly in their turn according

to their order numbers as determined by the impartial Na

tional draft lottery, but under separate “Negro quotas”

based on the percentage of negroes in the population of the

local board area.

Reasons Relied on for the Allowance of the Writ.

The Circuit Court of Appeals has decided an important

question of federal law which has not been, but should be,

settled by this Court.

It has decided:

(a) That it is not “discrimination against” petitioner, a

patriotic American citizen, to call him for induction later

6

than his turn according to the impartial national draft

lottery;

(b) That it is not “ discrimination against” petitioner to

call him, not strictly in his turn according to his order num

ber as determined by the impartial national lottery, but

pursuant to a separate “Negro quota” based on the per

centage of Negroes in the population of the local board

area.

Petitioner and the dissenting Justice of the Court below,

Mr. Justice Clark, view the practice of the Draft Authori

ties, thus upheld, as a direct violation of the expressed

will and policy of Congress. Where a statute says there

shall be “ no discrimination” in the selection of men, can the

civilian authorities through draft boards handle the selec

tion of men in such a way that the color of a man plays

a significant part in his induction? American citizens are

entitled to be called to serve in their turn as American citi

zens and this applies to all—Jew, Protestant, or Catholic,

white, red or black. Petitioner considers the present method

of selection a tragic blow to the freedom and solidarity of the

nation, affecting in its consequences not only the liberties,

sensibilities, and self-respect of the 13,000,000 Negroes of the

counfry, but also the liberties of all others. Selection of

men is'a civilian not a military function. If the unequivocal

direction of Congress can be flouted by ministerial officers,

civil or military, the liberties of all of us—and particularly

the rights of the millions of young men, white and black,

now being drafted—are endangered.

A herefore petitioner prays that a writ of certiorari may

issue out of and under the seal of this Court, directed to

the 1 nited States Circuit Court of Appeals for the Second

Circuit, commanding that Court to certify and send to

this Court for review and determination, as provided by

7

law, this cause and a complete transcript of the record and

of all proceedings had herein; that the order of the

United States Circuit Court of Appeals affirming the judg

ment in this cause may be reversed; and that petitioner

may have such other and further relief in the premises as

this Court may deem proper.

Dated April ~) , 1944.

A rthur G arfield H ays,

G erald W eatherly ,

Counsel for Petitioner.

I hereby certify that I have examined the foregoing peti

tion for a writ of certiorari and that in my opinion it is

well founded and the cause is one in which the petition

should be granted.

A rthur Garfield H ays,

Counsel for Petitioner.

i i ’ttjm n tt? (H orn*! o f tlip S t a t e s

October Term , 1943

No.

United States of A merica ex rel. W infred W illiam Ly n n ,

Petitioner,

— against—

Colonel J ohn W. D owner, Commanding Officer at Camp

Upton, New York,

Respondent.

-*■-----------------------------------

BRIEF US SUPPORT OF PETITION FOR CERTIORARI

Jurisdiction.

The statement of jurisdiction is in the foregoing petition.

Statement of the Case.

The facts have been set forth in the foregoing petition.

SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT

POINT I.

The selection and induction of petitioner pursuant

to the Negro quota requisition, in conjunction with the

separate Negro delivery list, was discrimination against

him on account of race or color and in violation of the

statute.

POINT II.

The judgment of the Circuit Court of Appeals should

be reversed, and petitioner should be discharged.

10

A R G U M E N T

POINT I.

The selection and induction of petitioner pursuant

to the Negro quota requisition, in conjunction with the

separate Negro delivery list, was discrimination against

him on account of race or color and in violation of the

statute.

The law says there should be no discrimination because

of race or color. Col. McDermott says that color has some

thing to do with the time men are called. Is this, or is this

not, discrimination?

The word “discriminate” is defined in Webster’s New

International Dictionary (2d ed.) as follows:

“ * * * having the difference marked * * * distinct; * * *

to serve to distinguish; to mark as different; to differ-

entiate; * * * to separate by discerning differences; to_

rlist.ingnlshL; * * * to make a distinction; * * * to make

a difference in treatment or favor (of one as compared

with others) * * * ”

In the Standard Universal Dictionary, “discriminate” is

defined:

“ To note the differences between; note or set apart