Phillips v. Martin Marietta Corporation Petition for Writ of Certiorari

Public Court Documents

October 6, 1969

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Phillips v. Martin Marietta Corporation Petition for Writ of Certiorari, 1969. 8e333f32-c19a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/35d6413a-78a1-4a2d-9648-1e1bf5e8b452/phillips-v-martin-marietta-corporation-petition-for-writ-of-certiorari. Accessed February 23, 2026.

Copied!

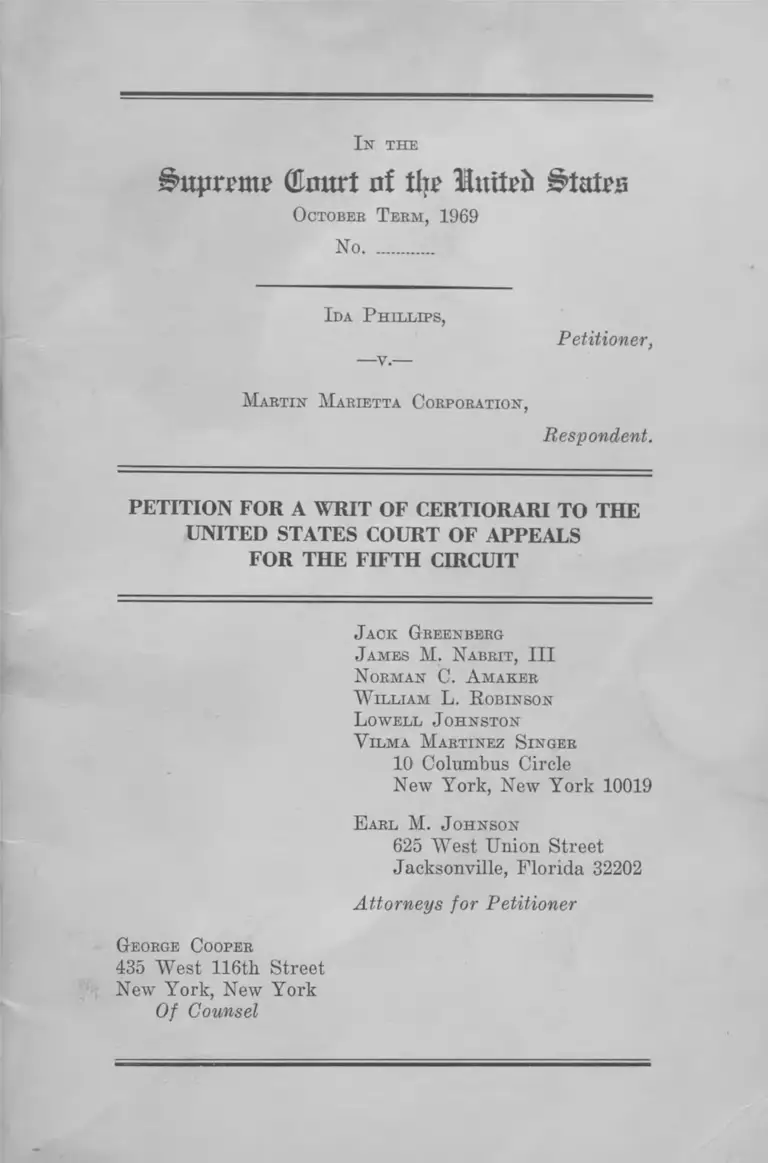

In the

(Enurt nf the ilnttpfr States

October Term, 1969

No. ...........

I d a P h i l l i p s ,

—v.—

Petitioner,

Martin Marietta Corporation,

Respondent.

PETITION FOR A WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE FIFTH CIRCUIT

Jack Greenberg

James M. Nabrit, III

N orman C. A maker

W illiam L. R obinson

L owell J ohnston

V ilma M artinez Singer

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

E arl M. Johnson

625 West Union Street

Jacksonville, Florida 32202

Attorneys for Petitioner

George Cooper

435 West 116th Street

New York, New York

Of Counsel

I N D E X

PAGE

Opinions B elow ................................................................... 1

Jurisdiction ......................................................................... 2

Question Presented............................................................. 2

Statutory Provisions Involved ........................................ 2

Statement of the Case ........................................................ 4

Reasons for Granting the Writ ...................................... 4

I. The Decision Below Is Based Upon An Er

roneous Interpretation of Title V II of the

Civil Rights Act of 1964 Which Impairs Its

Effectiveness and Conflicts in Principle With

Other Court of Appeals Decisions ................... 5

II. The Principle Established by the Court of

Appeals Decision Threatens the Effectiveness

of the Entire Federal Fair Employment Law 9

Conclusion ........................................................................... 12

Appendix—

Opinion of the District C ourt.................................. la

Opinion of the United States Court of Appeals..... 4a

Per Curiam Opinion Denying Rehearing................. 12a

11

A uthorities Cited

page

Cases:

Bowe v. Colgate-Palmolive Co., 416 F.2d 711 (7tli Cir.

1969) ................................................................................. 7

Cox v. United States Gypsum Co., 284 F. Supp. 74

(N.D. Ind. 1968) ............................................................ 9

International Chemical Workers Union v. Planters

Mfg. Co., 259 F. Supp. 365 (N.D. Miss. 1966) ........... 9

Local 53, Heat & Frost Insulators Workers v. Vogler,

407 F.2d 1047 (5th Cir. 1969) ...................................... 7,8

Papermakers Local 189 v. United States, 416 F.2d 980

(5th Cir. 1969) ................................................................. 8

Udall v. Tallman, 380 U.S. 1 (1965) ................................ 9

United States v. Sheet Metal Workers, Local 36, 416

F.2d 123 (8th Cir. 1969) .................................................. 8

Weeks v. Southern Bell Tel. & Tel. Co., 408 F.2d 228

(5th Cir. 1969) ................................................................. 6

Statutes:

28 U.S.C. § 1254(1) ............................................................. 2

42 U.S.C. § 2000e-2(a) ........................................................ 2,5

42 U.S.C. § 2000e-2(e) ........................................................ 3,6

Miscellaneous:

110 Cong. Rec. 7213 (1964) 7

I ll

PAGE

Cooper and Sobol, Seniority and Testing Under Fair

Employment Laics: A General Approach to Objec

tive Criteria of Hiring and Promotion, 82 Harv. L.

Rev. 1598 (1969) ............................................................. 7

Employment, Race and Poverty (Ross & Hill eds. 1967) 11

Equal Employment Opportunity Commission, Sex Dis

crimination Guidelines, 29 C.F.R. §§ 1604.1(a),

1604.2, 1604.3 ................................................................. 7,8-9

First Annual Digest of Legal Interpretations of EEOC,

CCH Empl. Prac. Guide, 17,251.043 (Oct. 22, 1965)

H. R. Rep. No. 914, 88th Cong., 1st Sess. (1963)............. 7

Opinion of the General Counsel of the EEOC, CCH

Empl. Prac. Guide 1219 .............................................. 9

Peterson, Working Women, 93 Daedalus 671 (1964) .... 11

Rosenfeld and Perrella, Why Women Start and Stop

Working: A Study in Mobility, Monthly Labor Re

view, Sept. 1965 .............................................................. 10

U. S. Department of Labor, Bull. No. 290, 1965 Hand

book on Women Workers (1965) ...............................10,11

I n the

i ’ltjin'm? (Hmtrt of tip ‘Hmtefc Stairs

October T erm, 1969

No..............

Ida P hillips,

—v.-

Petitioner,

Martin M arietta Corporation,

Respondent.

PETITION FOR A WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE FIFTH CIRCUIT

The petitioner Ida Phillips respectfully prays that a writ

of certiorari issue to review the judgment and opinion of

the United States Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit

entered in this proceeding on May 26, 1969.

Opinions Below

The opinion of the Court of Appeals is reported at 411

F.2d 1 and is reprinted in the Appendix. The Denial of

rehearing and accompanying dissent of Chief Judge Brown

and Judges Ainsworth and Simpson, not yet reported, and

the opinion of the District Court for the Middle District of

Florida, also not reported, appear in the Appendix.

2

Jurisdiction

The judgment of the Court of Appeals for the Fifth

Circuit was entered May 26, 1969. A timely request for

rehearing, initiated by a member of the Court, was denied

October 13, 1969, and this petition for certiorari was filed

within 90 days of that date. This Court’s jurisdiction is

invoked under 28 U.S.C. §1254(1).

Question Presented

Whether the sex discrimination prohibition of § 703,

Civil Rights Act of 1964, is violated by refusal to hire all

women with preschool children while hiring men of the

same class, where the distinction does not purport to be

based on a bona fide occupational qualification.

Statutory Provisions Involved

United States Code, Title 42

§2000e-2(a) [§703(a) of Civil Rights Act of 1964]

(a) It shall be an unlawful employment practice for

an employer—

(1) to fail or refuse to hire or to discharge any indi

vidual, or otherwise to discriminate against any indi

vidual with respect to his compensation, terms, condi

tions, or privileges of employment, because of such

individual’s race, color, religion, sex or national origin;

or

(2) to limit, segregate, or classify his employees in

any way which would deprive or tend to deprive any

individual of employment opportunities or otherwise

adversely affect his status as an employee, because of

3

such individual’s race, color, religion, sex, or national

origin.

§2000e-2(e) [§703(e) of Civil Rights Act of 1964]

(e) Notwithstanding any other provision of this title,

(1) it shall not be an unlawful employment practice

for an employer to hire and employ employees, for an

employment agency to classify, or refer for employ

ment any individual, for a labor organization to classify

its membership or to classify or refer for employment

any individual, or for an employer, labor organization,

or joint labor-management committee controlling ap

prenticeship or other training or retraining programs

to admit or employ any individual in any such program

on the basis of his religion, sex, or national origin in

those certain instances where religion, sex, or national

origin is a bona fide occupational qualification reason

ably necessary to the normal operation of that particu

lar business or enterprise, and (2) it shall not be

an unlawful employment practice for a school, college,

university or other educational institution or institu

tion of learning to hire and employ employees of a

particular religion if such school, college, university, or

other educational institution or institution of learning

is, in whole or in substantial part, owned, supported,

controlled, or managed by a particular religion or by

a particular religious corporation, association, or soci

ety, or if the curriculum of such school, college, uni

versity, or other educational institution or institution

of learning is directed toward the propagation of a

particular religion.

4

Statement of the Case

Ida Phillips, the petitioner, applied for an Assembly-

Trainee job with Martin Marietta Corporation, the respon

dent (hereinafter “ Martin” ). She had a high school back

ground, the only specified prerequisite to the job. How

ever, Martin refused to accept her application, stating that

it did not hire women with “pre-school age children” for

this job, although men with pre-school children were hired.

Moreover, it does not appear that respondent hires women

whose pre-school children may be cared for, for example,

by a grandmother or older sibling or day care center. Nor,

does respondent apparently even inquire concerning

whether a male applicant for employment is a widower

with a pre-school child or whether the wife of a married

employee with a child is employed or otherwise not in

full-time charge of the child.

Mrs. Phillips complained that this constituted unlawful

sex discrimination under the Civil Rights Act of 1964. The

District Court struck her allegations regarding the pre

school children rule as “ irrelevant and immaterial” and

ruled for Martin on summary judgment when she could

introduce no other evidence of sex discrimination. The

Court of Appeals affirmed, holding that this discrimination

“based on a two-pronged qualification, i.e., a woman with

pre-school age children” was not discrimination because of

sex within the meaning of the Act.

Reasons for Granting the Writ

The decision below is based upon an illogical interpreta

tion of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 which impairs its effec

tiveness and which conflicts in principle with other Court

of Appeals decisions. Although the case involves only dis

5

crimination against women, its effect upon the substantial

number of Negro women in the work force makes the de

cision particularly important with respect to the racial

discrimination provisions of the law. Moreover, the princi

ple established below threatens the effectiveness of the en

tire Federal equal employment law. In the words of Chief

Judge Brown (dissenting), if the “ sex-plus” rule of this

case stands, “ the Act is dead.” Appendix, at 18a. It is

important, moreover, that this issue be promptly resolved,

to protect the credibility of the regulations of the Equal

Employment Opportunity Commission which are directly

contradicted by the decision below.

I.

The Decision Below Is Based Upon an Erroneous In

terpretation of Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964

Which Impairs its Effectiveness and Conflicts in Prin

ciple With Other Court of Appeals Decisions.

The prohibition against sex discrimination in Title VII

of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 does not prohibit only flat

refusals to hire women. It is unlawful for an employer

“ otherwise to discriminate” against women. See §703(a),

42 U.S.C. §2000e-2(a). The District Court attempted to

justify its decision by stating that:

“ The responsibilities of men and women with small

children are not the same, and employers are entitled

to recognize these different responsibilities in establish

ing hiring policies.” 1

While it may be argued that because a woman might have

special responsibilities toward her children she may be

treated differently in hiring, this fails to take account of 1

1 See Appendix, p. 2a, infra.

6

the situation where peculiar responsibilities do not in fact

affect job performance. Martin will not hire women with

pre-school children if there is a grandmother or older sister

at home to care for them, or if a day care center fulfills

that purpose. Nor will it hire women with pre-school

children even if their husbands are at home unemployed

(as often occurs because of lay-off or disability).2 Martin

will apparently hire widowers with pre-school children, but

not widows. It will apparently hire men with pre-school

children even if their wives are already employed elsewhere.

The Martin rule makes no attempt to assess family respon

sibility in any objective way. The use of such stereotypes

is, we submit, the essence of unlawful discrimination pro

hibited by Title VII.

The reasoning of the District Court would have some

merit only if there were differing responsibilities which

affected the job performance of women workers. Martin

might then take account of job performance needs in two

ways:

1. The Act enables an employer to impose a differ

ent hiring standard for women where the standard is

shown to be a “bona fide occupational qualification rea

sonably necessary to the normal operation of that par

ticular business” (sometimes referred to as BFOQ)

under section 703(e), 42 U.S.C. §2000e-2(e). See Weeks

v. Southern Bell Tel. & Tel. Co., 408 F.2d 228 (5th Cir.

1969).

2. Where a BFOQ cannot be established, there is

another lawful way that an employer can take account

of family responsibilities. This is through use of a

neutral, not sex based, rule regarding such responsi

2 Seven percent of working women have husbands who cannot

work. See no. 9, infra.

7

bilities. For example, if an employer can show that

the family responsibilities of a spouse who is the sole

caretaker of children makes such a person an unreli

able employee, the employer may consider a general

hiring rule that bars jobs to all spouses who are sole

caretakers—including widowers as well as widows, and

taking into account child care arrangements. This

would be neutral and would deal with the specific

problem which concerned the employer.3 Only the

slightest change in employee hiring questionnaires

would be necessary.

However, Martin has not attempted use of either provision.

Martin did not urge a BFOQ defense or even claim that

mothers of pre-school children are poor performers on the

job.4 Nor has Martin attempted to apply a neutral standard

in this case.

Title VII prohibits double standards, i.e., any practice

which unequally restricts the job opportunities of women

or which imposes a burden on women not equally imposed

on men. See Bowe v. Colgate-Palmolive Co., 416 F.2d 711

(7th Cir. 1969); Equal Employment Opportunity Commis

sion Sex Discrimination Guidelines, 29 C.F.R. §§ 1604.2,

3 Even a neutral rule should be supported by evidence of busi

ness need to prevent its use as a device to discriminate against

women. See Local 53, Heat & Frost Insulators Workers v. Vogler,

407 F.2d 1047 (5th Cir. 1969); Cooper and Sobol, Seniority and

Testing Under Fair Employment Laws: A General Approach to

Objective Criteria of Hiring and Promotion, 82 Harv. L.Rev. 1598,

1669-73 (1969).

4 It is doubtful that Martin could establish a BFOQ defense in

this case. The BFOQ exception should be read with a narrow scope

to prevent it from violating the law against sex discrimination.

See 110 Cong. Rec. 7213 (1964) ; H.R. Rep. No. 914, 88th Cong.,

1st Sess. (1963) ; Equal Employment Opportunity Commission

Sex Discrimination Guidelines, 29 C.F.R. §1604.1 (a) (1968). The

point, here, however, is that Martin has not even claimed that the

defense is applicable.

8

1604.3; cf. Local 53, Heat & Frost Insulators Workers v.

Vogler, 407 F.2d 1047 (5th Cir. 1969) (race discrimination);

Papermakers Local 189 v. United States, 416 F.2d 980 (5th

Cir. 1969) (race discrimination); United States v. Sheet

Metal Workers, Local 36, 416 F.2d 123 (8th Cir. 1969) (race

discrimination). The practice challenged in this case is a

patent violation of this law.

The Court of Appeals justified its decision somewhat dif

ferently from the District Court. It reasoned that Mrs.

Phillips had not been excluded because of sex but rather be

cause of “ sex plus,” a two-pronged test: (1) being female

and (2) having pre-school children, which coalesced in her

case, and that such two-pronged tests did not constitute un

lawful discrimination.5 However, this would make sense

only if the law were limited to flat refusals to hire women.

Since the law also prohibits extra burdens on women, it

should be clear that “ sex plus” rules are unlawful. Any

rule having sex as one of its factors clearly makes it more

difficult for women to obtain jobs than men.6 The Commis

sion’s Guidelines and its rulings make clear that “ sex plus”

is a violation of Title VII. See Sex Discrimination Guide

6 See Appendix pp. 9a-10a, infra.

6 The Court of Appeals also relied on evidence that Martin had

hired a high percentage of female Assembly-Trainees (75 -80% ).

But, of course, no specific percentage of female employees can per

se prove no discrimination. W e do not claim that Martin dis

criminated against all women, but only that it discriminated

against a class of women. There are dozens of reasons why a high

percentage of women might be employed in spite of the fact that

an employer is discriminating against one class of women. For

example, the job might be one which appeals to women or one for

which women tend to he more qualified. Thus no particular con

clusion regarding discrimination can be drawn from the high per

centage of females in the position. The only relevant point is

that the percentage presumably would and should have been even

higher had Martin not applied its discriminatory pre-school chil

dren rule which screened out a large group of women from con

sideration.

9

lines, 29 C.F.R. § 1604.3; Gen.Counsel Opinion Letter, Sept.

9, 1965, in CCH Empl. Prac. Guide fl 1219.29. The Commis

sion filed a brief as amicus curiae in this case in the Court

of Appeals urging reversal of the District Court decision

and filed a supplementary amicus brief supporting a re

hearing in the Court of Appeals.

The Court of Appeals’ rejection of the Commission’s

position is inconsistent with established principles calling

for deference to the contemporaneous interpretations of an

agency charged with enforcement of a complex law. Udall

v. Tollman, 380 U.S. 1, 16 (1965). This principle has un

usual importance in the case of the Equal Employment Op

portunity Commission. Cox v. United States Gypsum Co.,

284 F.Supp. 74, 78 (N.D. Ind. 1968); International Chem.

Workers Union v. Planters Mfg. Co., 259 F.Supp. 365, 366-

67 (S.D. Miss. 1966). As an agency with no coercive en

forcement powers, the Commission is uniquely dependent

on credibility and persuasion in accomplishing its goals.

n.

The Principle Established by the Court of Appeals

Decision Threatens the Effectiveness of the Entire Fed

eral Fair Employment Law.

In dissenting from denial of rehearing, Chief Judge

Brown, joined by Judges Ainsworth and Simpson, warned:

“If ‘sex plus’ stands, the Act is dead.” 7

It is not difficult to see why. Under the Court of Appeals

reading, an employer would be free to impose extra educa

tional requirements on women not imposed on men, to

require women to pass special tests not given to men, and

7 See Appendix, p. 18a, infra. The rehearing request was brought

on sua sponte by members of the court.

10

to meet an infinite variety of other extra standards from

which men would be exempted. All of this could be justified

on the ground that the discrimination was not against

women as such, but rather only against those women who

did not meet the special standard, and that this is “ sex-

plus.” Moreover, if “ sex plus” is not sex discrimination,

then it is difficult to understand why “ race-plus” is not

exempted from the race discrimination prohibition in the

Act. Thus the “ sex plus” rule in this case sows the seeds

for future discrimination against black workers through

making them meet extra standards not imposed on whites.

Even if the “ sex plus” rule is not expanded, in its nar

row application to mothers of pre-school children it will

deal a serious blow to the objectives of Title VII. If the

law against sex discrimination means anything it should

protect employment opportunities for those groups of

women who most need jobs because of economic necessity.

Working mothers of pre-schoolers are such a group.

Twenty-three per cent of mothers with at least one child

under six work, a total of 3.6 million mothers.8 Studies

show that, as compared to women with older children or

no children, these mothers of pre-school children were much

more likely to have gone to work because of pressing need.9

Forty-eight percent of pre-school mothers work because of

financial necessity and 8% because their husbands are un

able to work.10 Frequently,' these women are a key or

only source of income for their families. Sixty-eight per

cent of working women do not have husbands present in

8TJ.S. Dept, of Labor, 1965 Handbook on Women Workers,

Bull. 290, at 2, 42.

9 Rosenfeld and Perrella, W h y Women Start and Stop W orking:

A Study in Mobility, Monthly Labor Review, Sept. 1965, at 1077-79,

Table 1.

10 Ibid.

11

the household and two-thirds of these women are raising

children in poverty.11

Moreover, a barrier to jobs for mothers of pre-schoolers

is also offensive to the anti-race discrimination purposes

of Title VII. This rule tends to harm non-white mothers

more than white mothers.

“ [There is] no tendency for blacks in child bearing ages

to retire even temporarily from the labor force. This

situation is explained not only by the high incidence

of poverty in the Negro community and the economic

weakness of Negro males, but also by the large pro

portion of fatherless families.” 11 12 13

As of 1960, thirty-one per cent of non-white married women

with children under six were working, as compared with

only eighteen per cent of white women in the same cate-

11 U.S. Dept, of Labor, 1965 Handbook on Women Workers, Bull.

290, at 36.

12 Ross and Hill, eds., Employment, Race and Poverty, 23 (1967).

13 Peterson, Working Women, 93 Daedalus 671, 684 (1964).

12

CONCLUSION

For these reasons, a writ of certiorari should issue to

review the judgment and opinion of the Fifth Circuit.

Respectfully submitted,

Jack Greenberg

James M. Nabrit, III

N orman C. A maker

W illiam L. R obinson

L owell Johnston

V ilma M artinez Singer

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

E arl M. J ohnson

625 West Union Street

Jacksonville, Florida 32202

Attorneys for Petitioner

George Cooper

435 West 116th Street

New York, New York

Of Counsel

APPENDIX

APPENDIX

Opinion of the District Court

U nited S tates D istrict Court

M iddle D istrict of F lorida

Orlando D ivision

I da P hillips,

vs.

Plantiff,

T he M artin M arietta Corporation,

Defendant.

R uling on M otion for Summary Judgment

This cause came on before the Court for hearing July 8,

1968, on the motion of the defendant, M artin M arietta

Corporation, for summary judgment. The complaint as

originally filed alleged that the plaintiff was discriminated

against because of an alleged policy of the defendant not

to hire women with pre-school age children. In an order

entered February 26, 1968, this Court ruled that the dis

crimination raised by that allegation was not the sort of

discrimination prohibited by Title V II of the Civil Rights

Act of 1964, 42 U.S.C.A. 2000(e) et seq., and that the

allegation raising discrimination based on the fact that

the plaintiff had pre-school age children should be stricken.

The case proceeded on the basis of alleged discrimination

based on the plaintiff’s sex alone.

In support of its motion for summary judgment, the

defendant has filed affidavits and answers to interrogatories

la

2a

showing that the defendant has hired 479 women for the

same job for which the plaintiff sought to apply during

the relevant period of time; that 70-75% of the applicants

for that position were women; that 75-80% of the employees

holding that position were women, and that there is no

basis in this record to support a finding that the defendant

discriminated against this plaintiff because she is a woman.

The plaintiff maintains that a response to a request for

admission filed herein June 26, 1968, would be sufficient

to withstand defendant’s motion for summary judgment.

That request seeks an admission from the defendant

“ (t)hat the Martin Marietta Corporation now employs

males with pre-school age children in the position of

Assembly Trainees?” Although the time for objecting or

responding to that request for admission has not expired

at this time, the Court, for purposes of the motion for

summary judgment accepts that request for admission

as admitted, and finds that the defendant does employ

males with pre-school age children in the position of

Assembly Trainee. It is, however, the opinion of the Court

that such fact was irrelevant and immaterial to the issue

before the Court. The responsibilities of men and women

with small children are not the same, and employers are

entitled to recognize these different responsibilities in

establishing hiring policies.

The plantiff having submitted no affidavits tending to

show that the defendant discriminated against the plain

tiff because the plaintiff is a woman, it is the opinion of

the Court that there is no genuine dispute of material fact

and that the defendant is entitled to summary judgment

as a matter of law. It is, therefore,

Ordered and A djudged that the motion of the defendant,

Martin Marietta Corporation, for summary judgment be

Opinion of the District Court

3a

and is hereby granted; judgment in accordance with this

opinion will be entered separately.

D one and Ordered in Chambers at Orlando, Florida,

in this 8th day of July, 1968.

/ s / George C. Y oung

United States District Judge

Opinion of the District Court

Copies mailed to:

J. Thomas Cardwell, Esq., P. 0. Box 231, Orlando, Florida

Reese Marshall, Esq., 625 West Union Street, Jacksonville,

Florida.

4a

I n the

U nited S tates Court of A ppeals

F or the F ifth Circuit

No. 26825

Opinion of the United States Court of Appeals

Ida P hillips,

Plaintiff-Appellant,

versus

M artin M arietta Corporation,

Defendant-Appellee.

APPEAL FROM TH E UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

FOR THE MIDDLE DISTRICT OF FLORIDA

(May 26, 1969)

Before

Gew in , M cGowan* and M organ,

Circuit Judges.

M organ, Circuit Judge: The present action is before us

on an appeal from the granting of a motion for summary

judgment by the District Court. The original complaint

under Section 706 (e) of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, 42

U.S.C. §2000-5 (e), alleged that appellee Martin Marietta

Corporation had violated Section 703, 42 U.S.C. § 2000e-2

when it wrongfully denied appellant Phillips employment

* Judge Carl McGowan of the District of Columbia Circuit, sit

ting by designation.

5a

because of sex. An ancillary issue raised concerns the

propriety of the District Court’s allowing the appeal in

forma pauperis conditioned on appellant Phillips’ reimburs

ing the United States in the event of an unsuccessful appeal.

Ida Phillips, the appellant, submitted an application for

employment with the appellee, Martin Marietta Corpora

tion, for the position of Assembly Trainee pursuant to an

advertisement in a local newspaper. When Mrs. Phillips

submitted her application in an effort to gain employment,

an employee of Martin Marietta Corporation indicated

that female applicants with “pre-school age children” were

not being considered for employment in the position of

Assembly Trainee. However, males with “pre-school age

children” were being considered. A charge was thereafter

filed with the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission

alleging that plaintiff-appellant’s rights under Title VII

of the Civil Rights Act of 19641 had been violated. The

Commission found reasonable cause to believe that defen

dant Martin Marietta Corporation had discriminated on

the basis of sex, and plaintiff filed a class suit in the

District Court.

The District Court granted a motion to strike that por

tion of the complaint which alleged that discrimination

against women with pre-school age children violated the

statute, and it refused to permit the case to proceed as a

class action. The complaint was not dismissed, however,

and it was left open to plaintiff to submit evidence to prove

her general allegation that she had been discriminated

against because of her sex.

Defendant then moved for summary judgment, supported

by an uncontroverted showing that, while 70 to 75 percent

Opinion of the United States Court of Appeals

1 42 U.S.C. §2000e, et seq.

6a

of those who applied for this position wrere women, 75 to 80

percent of those holding the positions were women. Defen

dant claimed that this established that there was no dis

crimination against women in general, or against plaintiff

in particular. The Court granted the motion on the ground

that there were no material issues of fact which would sup

port a conclusion of discrimination on the basis of sex.

The primal issue presented for consideration is whether

the refusal to employ women with pre-school age children

is an apparent violation of the 1964 Civil Rights Act’s pro

scription of discrimination based on “ sex” . The pertinent

portion of the Act, 42 U.S.C. 2000e-2, reads as follows:

(a) It shall be unlawful employment practice for an

employer—

(1) to fail or refuse to hire or to discharge any

individual or otherwise to discriminate against

any individual with respect to his compensa

tion, terms, conditions, or privileges or employ

ment, because of such individual’s race, color,

religion, sex or national origin;

The defendants do not choose to rely on the “bona fide

occupational qualification” section of the Act,2 but, instead,

defend on the premise that their established standard of not 1

Opinion of the United States Court of Appeals

2 42 U.S.C. §2000e-2(e) :

Unlawful employment practices—Employer practices. Busi

nesses or enterprises with personnel qualified on basis of

religion, sex, or national origin; educational institutions with

personnel of particular religion.

(e) Notwithstanding any other provision of this subehapter,

(1) it shall not be an unlawful employment practice for an

employer to hire and employ employees, for an employment

agency to classify, or refer for employment any individual,

7a

hiring women with pre-school age children is not per se dis

crimination on the basis of “ sex” .

The question that confronts us is a novel one upon which

the courts have been asked to rule only on a few occasions.

However, none of the cases reviewed by this Court deal with

the specific issue presented here. In the case of Cooper v.

Delta Airlines, Inc., 274 F. Supp. 781 (E.D. La., 1967), ap

peal dismissed, No. 25,698, 5 Cir., Sept. 1968 the District

Court held that an airlines hostess who is fired because she

was married has not been discriminated against on the

basis of sex. However, Delta did not consider men for the

positions in question, and therefore, unlike the case sub

judice, the discrimination was between different categories

of the same sex. Recently the Fifth Circuit was called upon

to review a problem of a kindred nature in Weeks v. South

ern Bell Telephone & Telegraph Co., No. 25,725 (5 Cir.,

Opinion of the United States Court of Appeals

for a labor organization to classify its membership or to

classify or refer for employment any individual, or for an

employer, labor organization, or joint labor-management

committee controlling apprenticeship or other training or

retraining programs to admit or employ any individual in

any such program, on the basis of his religion, sex, or

national origin in those certain instances where religion,

sex, or national origin is a bona fide occupational qualifica

tion reasonably necessary to the normal operation of that

particular business or enterprise, and (2) it shall not be

an unlawful employment practice for a school, college, uni

versity, or other educational institution or institution of

learning to hire and employ employees of a particular reli

gion if such school, college, university, or other educational

institution or institution of learning is, in whole or in sub

stantial part, owned, supported, controlled, or managed by

a particular religion or by a particular religious corporation,

association, or society, or if the curriculum of such school,

college, university, or other educational institution or insti

tution of learning is directed toward the propagation of a

particular religion.

8a

Mar. 4, 1969). However, that case is inapposite to the case

at bar in that the defendant in Weeks, supra, established

its defense on the “bona fide occupational qualification” ,

rather than relying solely on 42 U.S.C. 2000e-2a (1).

The position taken by the Equal Employment Opportunity

Commission is that where an otherwise valid criterion is

applied solely to one sex, then it automatically becomes a

per se violation of the Act. In its argument, the defendant

outlines the proposal that before a criterion which is not

forbidden can be said to violate the Act, the court must be

presented some evidence on which it can make a determina

tion that women as a group were treated unfavorably, or

that the applicant herself was singled out because she was

a woman. However, neither litigant is able to present sub

stantive support for its theory. Both cite selected sections

from the congressional history of the bill; however, a per

usal of the record in Congress will reveal that the word

“ sex” was added to the bill only at the last moment and no

helpful discussion is present from which to glean the intent

of Congress. To buttress its position, the Commission cites

to its own regulations; however, it is well established ad

ministrative law that the construction put on a statute by

an agency charged with administering it is entitled to def

erence by the courts, but the courts are the final authorities

on issues of statutory construction. Volkswagenwerk v.

FMC, 390 U.S. 261 (1968).

We are of the opinion that the words of the statute are

the best source from which to derive the proper construction.

The statute proscribes discrimination based on an indi

vidual’s race, color, religion, sex, or national origin. A per

se violation of the Act can only be discrimination based

solely on one of the categories i.e. in the case of sex; women

vis-a-vis men. When another criterion of employment is

Opinion of the United States Court of Appeals

9a

added to one of the classifications listed in the Act, there is

no longer apparent discrimination based solely on race,

color, religion, sex, or national origin. It becomes the func

tion of the courts to study the conditioning of employment

on one of the elements outlined in the statute coupled with

the additional requirement, and to determine if any indi

vidual or group is being denied work due to his race, color,

religion, sex or national origin. As was acknowledged in

Cooper, supra, 42 U.S.C. 2000e-2 (a) does not prohibit dis

crimination on any classification except those named within

the Act itself.3 Therefore, once the employer has proved

that he does not discriminate against the protected groups,

he is free thereafter to operate his business as he deter

mines, hiring and dismissing other groups for any reason

he desires. However, it is the duty of the employer to pro

duce information to substantiate his defense of non-dis

crimination. It is emphasized that this issue does not con

cern the bona fide occupational qualification under which

discrimination is admitted by the employer while alleging

that such discrimination was justified.

As to the case sub judice, as assembly trainee, among

other disqualifications, cannot be a woman with pre-school

age children. The evidence presented in the trial court

is quite convincing that no discrimination against women

as a whole or the appellant individually was practiced by

Martin Marietta. The discrimination was based on a two

pronged qualification, i.e., a woman with pre-school age

children. Ida Phillips was not refused employment because

she was a woman nor because she had pre-school age

Opinion of the United States Court of Appeals

3 “ The discrimination lies in the fact that the plaintiff is mar

ried— and the law does not prevent discrimination against married

people in favor of the single ones.” Cooper v. Delta Air Lines,

Inc., 274 F . Supp. 781 (1967).

10a

children. It is the coalescence of these two elements that

denied her the position she desired. In view of the above,

we are convinced that the judgment of the District Court

was proper, and we therefore affirm.

Decision in this case ultimately turns, of course, upon

the reach of the Congressional intention underlying the

statutory prohibition of discrimination in employment

based upon sex. Where an employer, as here, differentiates

between men with pre-school age children, on the one hand,

and women with pre-school age children, on the other, there

is arguably an apparent discrimination founded upon sex.

It is possible that the Congressional scheme for the hand

ling of a situation of this kind was to give the employer

an opportunity to justify this seeming difference in a treat

ment under the “bona fide employment disqualification”

provision of the statute.

The Commission, however, in its appearance before us

has rejected this possible reading of the statute. It has

left us, if the prohibition is to be given any effect at all

in this instance, only with the alternative of a Congressional

intent to exclude absolutely any consideration of the differ

ences between the normal relationships of working fathers

and working mothers to their pre-school age children, and

to require that an employer treat the two exactly alike

in the administration of its general hiring policies. If this

is the only permissible view of Congressional intention

available to us, as distinct from concluding that the seem

ing discrimination here involved was not founded upon

“sex” as Congress intended that term to be understood,

we have no hesitation in choosing the latter. The common

experience of Congressmen is surely not so far removed

from that of mankind in general as to warrant our attribut

ing to them such an irrational purpose in the formulation

of this statute.

Opinion of the United States Court of Appeals

11a

Opinion of the United States Court of Appeals

In conclusion, we address ourselves to the condition

attached to the in forma pauperis grant. Once the District

Court has determined that the application to proceed in

forma pauperis is meritorious, the discretion of the Court

is closed and the application should be granted. Title 28,

U.S.C.A. 1915; Williford v. People of State of California,

329 F. 2d 47 (9 Cir., 1964). The condition that appellant

Phillips must reimburse the United States in the event

of an unsucessful appeal is hereby removed from the grant

to proceed in forma pauperis.

A ffirmed.

12a

Ik the

U nited S tates Court of A ppeals

F or the F ifth Circuit

No. 26825

Per Curiam Opinion Denying Rehearing

Ida P hillips,

Plaintiff-Appellant,

versus

Martin M arietta Corporation,

Defendant-Appellee.

APPEAL FROM THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE

MIDDLE DISTRICT OF FLORIDA

(October 13, 1969)

Before

Gew in , M cGowan* and M organ,

Circuit Judges.

Per Cu riam : The Petition for Rehearing is Denied and

the Court having been polled at the request of one of the

members of the Court and a majority of the Circuit Judges

who are in regular active service not having voted in favor

of it (Rule 35 Federal Rules of Appellate Procedure; Local

Fifth Circuit Rule 12), Rehearing En Banc is also Denied.

* From the D.C. Circuit, sitting by designation.

13a

Per Curiam Opinion Denying Rehearing

Before B rown, Chief Judge, W isdom, Gew in ,

B ell, T hornberry, Coleman, Goldberg,

A insworth, Godbold, Dyer, Simpson,

M organ, and Carswell, Circuit Judges.

B rown, Chief Judge, with whom A insworth and S impson,

Circuit Judges, join, dissenting:

I dissent from the Court’s failure to grant rehearing

en banc.1

I .

Without regard to the intrinsic question of the cor

rectness of the Court’s decision and opinion, this is one

of those cases within the spirit of FRAP 35 and 28 USCA

§ 46 which deserves consideration by the full Court.

As the records of this Court reflect, we have within the

very recent months had to deal extensively with Title VII

civil rights cases concerning discrimination in employment

on account of race, color, sex and religion.1 2 * * 5 Court decisions

on critical standards are of unusual importance. This is

1 Presumably because it was amicus only and not a party, the

Government did not seek either rehearing or rehearing en banc.

For understandable reasons the private plaintiff, Ida Phillips, who

has the awesome role of private Attorney General without benefit

of portfolio, or more important, an adequate purse, presumably

felt that she had fulfilled her duty when the Court ruled. Subse

quently, on a poll being requested, F R A P 35 ; 5th Circuit Rule 12,

the Government filed a strong brief attacking the Court’s decision.

Likewise, the private plaintiff’s counsel filed a persuasive brief.

This merely emphasizes that it has been members of this Court,

not the parties, who have raised questions about the Court’s deci

sion. This is in keeping with 28 U SC A §46 and F R A P 35.

2 These include the following and those cited therein:

Jenkins v. United States Gas Corp., 5 Cir., 1968, 400 F.2d 28;

Oatis v. Crown Zellerbach Corp., 5 Cir., 1968, 398 F.2d 496;

Pettway v. American Cast Iron Pipe Co., 5 Cir., 1969, 411

F.2d 998; Local 189, United Papermakers and Paperworkers,

5 Cir., 1969, ------- F.2d ------- [No. 25956, July 28, 1969];

14a

so because, except for preliminary administrative efforts

at conciliation and the rare pattern or practice suit by the

United States,3 effectuation of Congressional policies is

largely committed to the hands of individual workers who

take on the mantle of a private attorney general4 to vindi

cate, not individual, but public rights.

This makes our role crucial. Within the proper limits

of the case-and-controversy approach we should lay down

standards not only for Trial Courts, but hopefully also for

the guidance of administrative agents in the field, as well

as employers, employees, and their representatives.

The full Court should look at the issue here posed. And

now in the light of the standard erected— sex if coupled

with another factor is acceptable—it is imperative that the

full Court look at it.

n.

Equally important, the full Court should look to correct

what, in my view, is a palpably wrong standard.

The case is simple. A woman with pre-school children

may not be employed, a man with pre-school children may.5 * 3 4 5

Per Curiam Opinion Denying Rehearing

United States v. Hayes Internat’l. Corp., 5 Cir., 1969, -------

F .2 d ------- [No. 26809, August 19, 1969]; Weeks v. Southern

Bell Tel. & Tel. Co., 5 Cir., 1969, 408 F.2d 228; Dent v. St.

Louis-S.F. Ky., 5 Cir., 1969, 406 F.2d 399.

Also pending before a panel of this Court are two analogous cases

under §17 of the Fair Labor Standards Act, 29 U SC A §§201

et seq., involving equality of compensation to women: No. 26960,

Schultz v. First Victoria Nat’l. Bank; and No. 26971, Shultz v.

American Bank of Commerce.

3 See §707(a), 42 U SC A §2000e-6 (a ).

4 See Pettway v. American Cast Iron Pipe Co., note 2, supra,

411 F.2d at 1005; Jenkins v. United Gas Corp., note 2, supra, 400

F.2d at 32-33.

5 The man would qualify even though as widower or divorce he

had sole custody of and responsibility for pre-school children.

15a

The distinguishing factor seems to be motherhood versus

fatherhood. The question then arises: Is this sex-related?

To the simple query the answer is just as simple: Nobody—

and this includes Judges, Solomonic or life tenured—has

yet seen a male mother. A mother, to oversimplyfy the

simplest biology, must then be a woman.

It is the fact of the person being a mother—i.e. a

woman—not the age of the children, which denies employ

ment opportunity to a woman which is open to a man.

How the Court strayed from that simple proposition

is not easy to divine. Not a little of the reason appears

to be a feeling that the Court in interpreting § 703(a)

(1), 42 USCA § 2000e-2(a) (1), prohibiting sex discrimina

tion,6 is bound to accept the contention of one of the parties,

rather than pick and choose, drawing a middle line, or for

that matter reaching independently an interpretation

sponsored by no one. Thus, after noting that in the Trial

Court and here the Employer did not “ choose to rely on

the ‘bona fide occupational qualification’ section of the

Act,7 but, instead, defended on the premise that their

6 Section 7 0 3 (a )(1 ) reads as follows:

“ (a) It shall be an unlawful employment practice for an em

ployer—

(1) to fail or refuse to hire or to discharge any individual,

or otherwise to discriminate against any individual with re

spect to his compensation, terms, conditions, or privileges of

employment, because of such individual’s race, color, religion,

sex, or national origin.”

42 U SCA §2000-e2 (a )( 1 ) .

7 Section 703 (e) states:

“ (e) Notwithstanding any other provision of this subchap

ter, (1) it shall not be an unlawful employment practice for

an employer to hire and employ employees, for an employment

agency to classify, or refer for employment any individual,

for a labor organization to classify its membership or to clas-

Per Curiam Opinion Denying Rehearing

16a

established standard of not hiring women with pre-school

age children is not per se discrimination on the basis of

‘sex’ ” (Phillips v. Martin Marietta Corp., 5 Cir., 1969, 411

F.2d 1, 2-3), the Court virtually acknowledges the patent

discrimination based on biology. The Court states: “Where

an employer, as here, differentiates between men with

pre-school age children, on the one hand, and women with

pre-school age children, on the other, there is arguably an

apparent discrimination founded upon sex. It is possible

that the Congressional scheme for the handling of a situa

tion of this kind was to give the employer an opportunity

to justify this seeming difference in treatment under the

‘bona fide employment disqualification’ provision of the

statute.” 411 F.2d at 4.

But in what immediately followed the Court then does

a remarkable thing. Referring to EEOC (appearing only

as amicus), it states: “ The Commission, however, in its

appearance before us has rejected this possible reading8

of the statute. It has left us, if the prohibition is to be

given any effect at all in this instance, only with the alter

native of a Congressional intent to exclude absolutely any

Per Curiam Opinion Denying Rehearing

sify or refer for employment any individual, or for an em

ployer, labor organization, or joint labor-management com

mittee controlling apprenticeship or other training or retrain

ing programs to admit or employ any individual in any such

program, on the basis of his religion, sex, or national origin

in those certain instances where religion, sex, or national

origin is a bona fide occupational qualification reasonably neces

sary to the normal operation of that particular business or

enterprise. * *

42 U SC A §2000e-2(e).

8 Such a reading is certainly not rejected by EEO C on this re

hearing. The supplemental brief (pp. 9-10) recognizes the em

ployer’s right to claim and prove the §703(e) “business necessity”

exemption. (See note 7, supra).

17a

consideration of the differences between the normal rela

tionships of working- fathers and working mothers to their

pre-school age children, and to require that an employer

treat the two exactly alike in the administration of its

general hiring policies. If this is the only permissible view

of Congressional intention available to us, * * * we have

no hesitation in choosing the latter.” 411 F.2d at 4.

It is this self-imposed interpretive straightjacket which,

I believe, leads the Court to the extremes of “ either/or”

outright per se violation with no defense or virtual com

plete immunity from the Act’s prohibitions. This it does

through its test of “ sex plus” : “ [1] A per se violation

of the Act can only be discrimination based solely on one

of the categories i.e. in the case of sex; women vis-a-vis

men. [2] When another criterion of employment is added

to one of the classifications listed in the Act, there is no

longer apparent discrimination based solely on race, color,

religion, sex, or national origin.” 9 411 F.2d at 3-4 (Em

phasis supplied).

Reducing it to this record the Court characterizes the

admitted discrimination in this way. “ The discrimination

was based on a two-pronged qualification, i.e., a woman

with pre-school age children. Ida Phillips was not refused

employment because she was a woman nor because she had

pre-school age children. It is the coalescence of these two

elements that denied her the position she desired. In view

of the above, we are convinced that the judgment of the

District Court was proper, and we therefore affirm.” 411

F.2d at 4 (Emphasis supplied).

Per Curiam Opinion Denying Rehearing

9 B y supplemental brief (p. 4, n. 1) EEO C agrees with [1] on

“per se” violations.

18a

I f “ sex plus” stands, the Act is dead.10 11 This follows

from the Court’s repeated declaration11 that the employer

is not forbidden to discriminate as to non-statutory factors.

Free to add non-sex factors, the rankest sort of discrimina

tion against women can be worked by employers. This

could include, for example, all sorts of physical charac

teristics, such as minimum weight (175 lbs.), minimum

shoulder width, minimum biceps measurement, minimum

lifting capacity (100 lbs.), and the like. Others could

include minimum educational requirements (minimum high

school, junior college), intelligence tests, aptitude tests,

etc. And it bears repeating that on the Court’s reading,

one of these would constitute a complete defense to a charge

of § 703(a) (1) violation without putting on the employer

the burden of proving “business justification” under

§ 703(e) (note 7, supra).

In addition to the intrinsic unsoundness of the “ sex

plus” standard, the legislative history refutes the idea that

Congress for even a moment meant to allow “non-business

justified” discrimination against women on the ground

that they were mothers or mothers of pre-school children.

On the contrary, mothers, working mothers, and working

mothers of pre-school children were the specific objectives

of governmental solicitude.

Per Curiam Opinion Denying Rehearing

10 Of course the “plus” could not he one of the other statutory

categories of race, religion, national origin, etc.

11 See, e.g., “As was acknowledged in Cooper, supra, 42 USC

2000e-2(a) does not prohibit discrimination on any classification

except those named within the Act itself. Therefore, once the em

ployer has proved that he does not discriminate against the pro

tected groups, he is free thereafter to operate his business as he

determines, hiring and dismissing other groups for any reason he

desires.” 411 F.2d at 4.

19a

Per Curiam Opinion Denying Rehearing

In the first place, working mothers constitute a large

class1- posing much discussed problems of economics and

sociology. And with this large class and the known practice

of using baby-sitters or child care centers, neither an

employer nor a reviewing Court can—absent proof of

“business justification” (note 7, supra)—assume that a

mother of pre-school children will, from parental obliga

tions, be an unreliable, unfit employer,12 13

12 Statistics compiled by the "Wage and Labor Standards Admin

istration of the United States Department of Labor indicate that

working mothers comprise an important and increasing segment

of the Nation’s labor resources. In the most recent compilation

(March 1967), there were 10.6 million working mothers in the

labor force with children under 18 years of age. This is an increase

of 6 million over 1950 and an increase of 9.1 million over 1940.

Of the total of working mothers in March 1967, 38 .9% were

mothers of children under 6 years of age and 20.7% were mothers

with children under 3 years of age. In numerical terms, 4.1 million

working mothers had children under 6 and 2.1 million working

mothers had children under 3. Who are the Working Mothers,

United States Department of Labor, W age and Labor Standards

Administration, p. 2-3 (Leaflet 37, 1968).

13 The brief of EEOC points out:

In answering the question: ‘W hat arrangements do working

mothers make for child care?’, the Department of Labor re

sponded :

‘In February 1965, 47 percent of the children under 6 years

of age were looked after in their own homes and thirty

percent were cared for in someone else’s home, but only 6

percent received group care in day care centers or similar

facilities.’

Who are Working Mothers, supra [Note 12].

Furthermore, it is the policy of the Administration to encourage

unemployed women on public assistance, who have children, to

enter the labor market by providing for the establishment of day

care centers to enable them to accept offers of employment. On

August 8, 1969, President Nixon stated in his address to the Na

tion on welfare reforms:

‘As I mentioned previously, greatly expanded day-care center

facilities would be provided for the children of welfare mothers

20a

In this and the related legislation on equality of com

pensation for women14 one of the reasons repeatedly

stressed for legislation forbidding sex discrimination was

the large proportion of married women and mothers in

the working force whose earnings are essential to the

economic needs of their families.15

Per Curiam Opinion Denying Rehearing

who choose to work. However, these would he day-eare centers

with a difference. There is no single ideal to which this A d

ministration is more firmly committed than to the enriching

of a child’s first five years of life, and thus helping lift the

poor out of misery, at a time when a lift can help the most.

Therefore, these day-care centers would offer more than cus

todial care; they would also be devoted to the development

of vigorous young minds and bodies. As a further dividend,

the day-care centers would offer employment to many welfare

mothers themselves.’ Text of Nixon’s Address to the Nation

Outlining His Proposals for Welfare Reform, N. Y . Times,

August 9, 1969, at 10, Col. 6.”

Brief for EEO C at 11-12.

14 Equal Pay Act of 1963, 77 Stat. 56, effective June 11, 1964,

29 U SC A §206. See pending cases, note 2 supra.

15 Thus, President Kennedy, in signing the Equal Pay Act, sum

marized the conditions which necessitated such a law, as follows:

“ [T]he average women worker earns only 60 percent of the

average wage for men * * * Our economy today depends upon

women in the labor force. One out of three workers is a woman.

Today, there are almost 25 million women employed, and their

number is rising faster than the number of men in the labor

force. It is extremely important that adequate provision he

made for reasonable levels of income to them, for the care

of the children * * * and for the protection of the family

unit * * * Today one out of five of these working mothers

has children under three. Two out of five have children of

school age. Among the remainder, about 50 percent have

husbands who earn less than $5,000 a year— many of them

much less. I believe they bear the heaviest burden of any

group in our nation. * * * ” [Kemarks of the President at

signing the Equal Pay Act on June 10, 1963, X X I Cong. Q.

No. 24, p. 978 (June 14, 1963).]

A t the Senate Hearings, Secretary of Labor W irtz pointed out:

21a

Congress could hardly have been so incongruous as to

legislate sex equality in employment by a statutory

structure enabling the employer to deny employment to

those who need the work most through the simple expedient

of adding to sex a non-statutory factor.16

A mother is still a woman. And if she is denied work

outright because she is a mother, it is because she is a

woman. Congress said that could no longer be done.

Per Curiam Opinion Denying Rehearing

“Women’s earnings, in many families, are a substantial factor

in meeting living costs. Married women, for example, ac

counted for over one-lialf of the total number of women work

ers in 1962. Nearly 900,000 working women had husbands

who, for various reasons, were not in the labor force, primarily

because they were disabled or retired. The proportion of

working wives is materially higher among families in the low-

income groups.” [1963 Senate Hearings, p. 16]

See also Representatives Green (109 Cong. Rec. 9199) :

“ There are approximately 25 million working women in the

labor force today, and we are simply asking, by this legislation,

to look at the facts as they face us in 1963, in instances where

there is unequal pay. * * * Women are the heads of 4.6 mil

lion families in the United States; one-tenth of all the families

in this country. Nearly one million working women have hus

bands who are not employed, mainly because they are disabled

or retired. Nearly 6 million working women are single. The

proportion of married women who work is materially higher

in the low-income families, and, according to the testimony

that was presented to the committee, some 7.5 million women

workers supplement the income of male wage earners who

make less than $3,000 a year. Women’s wages average less

than two-thirds of the wages paid men.”

16 Too much emphasis cannot be given to the employer’s right to

claim and prove the §703 (e) “business justification” exemption

(see note 7, supra). This was not done, but on remand it should

be open to the employer here.

MEILEN PRESS INC. — N. Y. C. 219