Clark v. Little Rock Board of Education Brief for Appellants

Public Court Documents

May 16, 1969

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Clark v. Little Rock Board of Education Brief for Appellants, 1969. 0220c692-ad9a-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/35d861a5-af8c-42dd-a554-ead2cf2c77a5/clark-v-little-rock-board-of-education-brief-for-appellants. Accessed February 23, 2026.

Copied!

J V

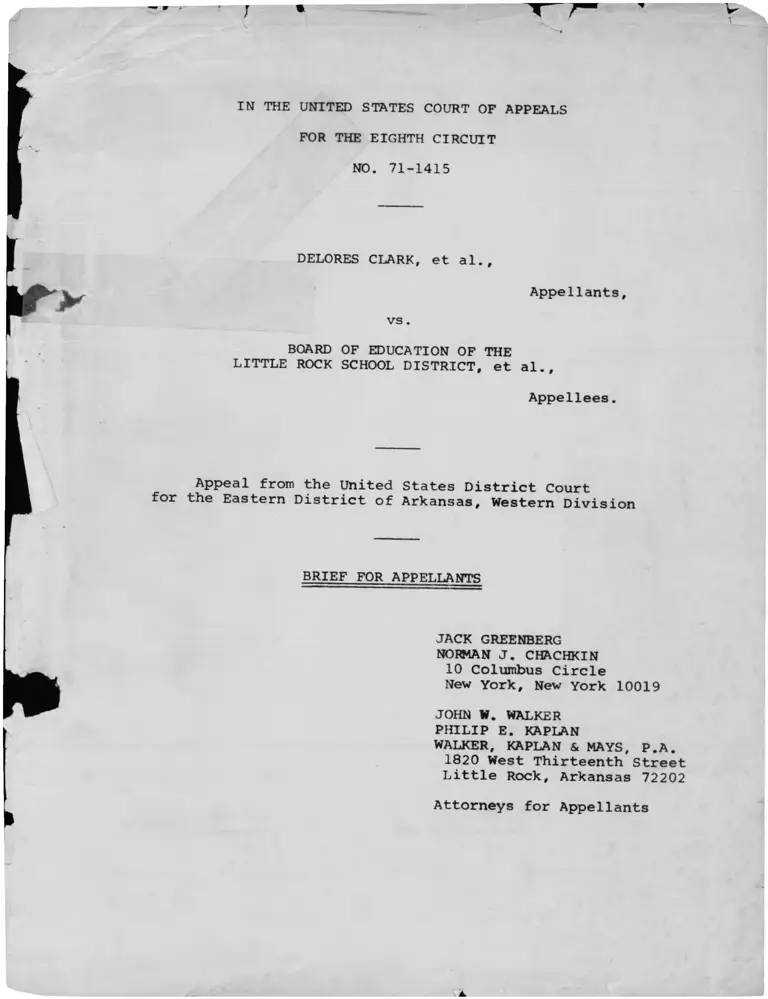

IN THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE EIGHTH CIRCUIT

NO. 71-1415

DELORES CLARK, et al..

Appellants,

vs.

BOARD OF EDUCATION OF THE

LITTLE ROCK SCHOOL DISTRICT, et al.,

Appellees.

Appeal from the United States District Court

for the Eastern District of Arkansas, Western Division

BRIEF FOR APPELLANTS

m

JACK GREENBERG

NORMAN J. CHACHKIN

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

JOHN W. WALKER

PHILIP E. KAPLAN

WALKER, KAPLAN & MAYS, P.A.

1820 West Thirteenth Street

Little Rock, Arkansas 72202

Attorneys for Appellants

IN THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE EIGHTH CIRCUIT

NO. 19795

DELORES CLARK, et al.,

Appellants,

vs.

THE BOARD OF EDUCATION OF THE LITTLE

ROCK SCHOOL DISTRICT, et al.

NO. 19810

DELORES CLARK, et al.,

Appellees,

vs.

THE BOARD OF EDUCATION OF THE LITTLE

ROCK SCHOOL DISTRICT, et al.

Appeals from the United States District Court for the Eastern

District of Arkansas, Western Division

BRIEF FOR APPELLANTS - CROSS-APPELLEES

JOHN W. WALKER

BURL C. ROTENBERRY

1820 West 13th Street

Little Rock, Arkansas 72202

JACK GREENBERG

JAMES M. NABRIT, III

NORMAN J. CHACHKIN

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

Attorneys for Appellants in

No. 19795

Attorneys for Appellees in

No. 19810

INDEX

Page

Table of C a s e s .......................................iii

Table of Statutes and Other A u t h o r i t i e s ...........viii

Preliminary Statement .............................. 1

Issues Presented for Review ........................ 2

Statement ........................................... 2

The Little Rock School District .............. 5

The Oregon and Parsons P l a n s .................. 13

Development of the Plan Approved Below . . . . 15

The Plan Approved Below

1. Pupil Assignment ...................... 18

2. Faculty.................................. 20

Alternatives Available to the District . . . . 23

ARGUMENT

Introduction .................................. 27

The Little Rock Zoning Plan For Pupil

Assignment Is Unacceptable Because It

Preserves The Racial Identity Given Each

School By Appellees' Own Past Policies And

Practices........................................ 29

The District's Plan For Faculty Desegregation

Is Inadequate.................................... 52

The District Court Has The Power To Require

That A Unitary School System Be Achieved Even

If The Neighborhood School Concept Must Be

Abandoned Or Provision Of Pupil Transportation

M a d e .............................................53

The District Court's Denial of Attorneys' Fees

Was An Abuse Of D i s c r e t i o n .....................61

C o n c l u s i o n ...................................... 65

►

i

Table 1 ........................................... 34

Maps:

1 Little Rock Public Schools 1956-1969 . . 7

Page

2 Sources of Racial Identities of

Little Rock S c h o o l s .....................40

3 Racial Identities of Little Rock

S c h o o l s ..................................41

4 1968-1969 Enrollment ................... 42

5 Projected Pupil Enrollment Under Zones

Approved Below .......................... 43

6 Projected Pupil Enrollment Under Zones

Approved Below .......................... 44

Appendices:

1 Defendants' Trial Exhibit No. 5 - Pupil

Enrollment 1960-61 to 1968-69 ......... 66

2 Defendants' Trial Exhibit No. 24 -

Faculty Assignments For 1969-70 In

Accordance With Defendants' Plan Of

Desegregation .......................... 77

3 Defendants' Trial Exhibit No. 25 -

Pupil Enrollment 1969-70 Projected

According to Zones Shown on Map,

Defendants' Trial Exhibit No. 22 . . . .80

4 Pp. 16 - 25 of Defendants' Trial

Exhibit No. 19 - "Walker" Plan of

Desegregation .......................... 83

5 Defendants' Exhibit No. 8 From 1965

Trial - Projection of Enrollments

Under Proposed Zoning P l a n .............93

6 Stipulation of Counsel As To Exhibits

in Aaron v. Cooper, 143 F. Supp. 855

(E.D. Ark. 1 9 5 6 ) ........................ 95

IX

Table of Cases

Page

Aaron v. Cooper, 243 F.2d 361 (8th Cir. 1957). . 2, 3, 27, 31

Aaron v. Cooper, 257 F -2d 33 (8th Cir. 1958),

aff'd sub nom. Cooper v. Aaron, 358 U.S.

1 (1958) .................................. 27

Aaron v. Cooper, 261 F.2d 97 (8th Cir. 1958) . . 4

Aaron v. Cooper, 143 F. Supp. 855 (E.D. Ark.

1956) , aff'd 243 F .2d 361 (8th Cir.

1 9 5 7 ) 3, 27, 33, 37, 38

Aaron v. Cooper, 2 Race Rel. L. Rep. 934 (E.D.

Ark. 1957), aff'd 254 F .2d 808 (8th Cir.

1 9 5 8 ) ...................................3

Aaron v. Cooper, 156 F. Supp. 220 (E.D. Ark.

1957), aff'd sub nom. Faubus v. United

States, 254 F.2d 797 (8 th Cir. 1958) . . . 3

Aaron v. Cooper, 163 F. Supp. 13 (E.D. Ark. 1958),

cert, denied, 357 U.S. 566 (1958), rev'd

257 F.2d 33 (8th Cir. 1958), aff'd sub nom.

Cooper v. Aaron, 358 U.S. 1 (1958) . . . . 3

Aaron v. Cooper, 169 F. Supp. 325 (E.D. Ark.

1 9 5 9 ) .......................................4

Aaron v. McKinley, 173 F. Supp. 944 (E.D. Ark.

1959) (per curiam), aff'd sub nom. Faubus

v. Aaron, 361 U.S. 197 (1959).............4

Aaron v. Tucker, 186 F. Supp. 913 (E.D. Ark.

1960) , rev'd sub nom. Norwood v. Tucker,

287 F . 2d 798 (8 th Cir. 1961) ............. 4

Anthony v. Marshall County Bd. of Educ., 409

F . 2d 1287 (5th Cir. 1 9 6 9 ) ................. 19

Balaban v. Rubin, 40 Misc. 2d 249, 242 N.Y.S.2d

974 (Sup. Ct. 1963), rev'd 20 A.D.2d 438,

248 N.Y.S.2d 574 (2d Dept.), aff'd 14 N.Y.2d

193, 199 N.E.2d 375, 250 N.Y.S.2d 281 (1964),

cert, denied, 379 U.S. 881 (1964)........ 30

Barksdale v. Springfield School Comm., 237 F.

Supp. 543 (D. Mass. 1965), vacated without

prejudice 348 F.2d 261 (1st Cir. 1965) . . 30

ill

Page

Bell v. School City of Gary, Ind., 213 F- Supp.

819 (N.D. Ind.), aff'd 324 F.2d 209 (7th

Cir. 1963), cert, denied, 377 U.S. 924

(1964) ..................................... 30

Bivins v. Board of Public Educ. of Bibb County,

284 F. Supp. 8 8 8 (M.D. Ga. 1967) ......... 57

Blocker v. Board of Educ. of Manhasset, 226 F.

Supp. 208 (E.D.N.Y. 1 9 6 4 ) ................. 30

Board of Public Instruction of Duval County

v. Braxton, 326 F.2d 616 (5th Cir. 1964) . 57

Board of Public Instruction of Duval County

v. Braxton, 400 F.2d 900 (5th Cir. 1968) . 56

Booker v. Board of Educ. of Plainfield, 45 N.J.

161, 212 A.2d 1 (1965) ................... 30

Boson v. Rippy, 285 F.2d 43 (5th Cir. 1960) . . 45

Braxton v. Board of Public Instruction of Duval

County, Civ. No. 4598-5 (M.D. Fla., Jan.

24, 1 9 6 7 ) .................................. 45

Brewer v. School Bd. of City of Norfolk, 397 F.2d

37 (4th Cir. 1968) ........................ 51

Brooks v. County School Bd. of Arlington County,

324 F . 2d 303 (4th Cir. 1963) ............. 45

Brown v. Board of Educ., 347 U.S. 483 (1954) . . 3

Brown v. Board of Educ., 349 U.S. 294 (1955) . . 3, 30, 56

Byrd v. Board of Directors of the Little Rock

School Dist., Civ. No. LR 65-C-142 (E.D.

Ark. 1965) ............................... 11, 12, 27

Carr v. Montgomery County Bd. of Educ., 253 F.

Supp. 306 (M.D. Ala. 1966) ............... 57

Cato v. Parham, 403 F.2d 12 (8th Cir. 1968) . . 24

Cato v. Parham, 297 F. Supp. 403 (E.D. Ark.

1 9 6 9 ) ....................................... 46-47

Cato v. Parham, Civ. No. PB 67-C-69 (E.D. Ark.

July 25, 1969) ............................ 48

Clark v. Board of Educ. of Little Rock, 369 F.2d

661 (8 th Cir. 1966)

IV

4, 5, 11, 27, 33, 37,

45, 61, 63

Page

Cooper v. Aaron, 358 U.S. 1 (1958)............. 3, 30, 56

Coppedge v. Franklin County Bd. of Educ., 404

F.2d 1177 (4th Cir. 1 9 6 8 ) ................. 64

Davis v. Board of Comm'rs of Mobile County, 3 93

F . 2d 690 (5th Cir. 1968) ................. 60

Deal v. Cincinnati Bd. of Educ., 244 F. Supp.

572 (S.D. Ohio 1965), aff'd 369 F.2d 55

(6th Cir. 1966), cert, denied, 389 U.S.

847 (1967) ................................ 30, 31

Dove v. Parham, 282 F .2d 256 (8 th Cir. 1960) . . 45, 49, 51-52, 60

Dowell v. School Bd. of Oklahoma City, 244 F.

Supp. 971 (W.D. Okla. 1965), aff'd 375

F.2d 158 (10th Cir.), cert, denied 387

U.S. 931 (1967)............................ 46, 56, 57

Dowell v. School Bd. of Oklahoma City, Civ. No.

9452 (W.D. Okla., August 8 , 1969), vacated

___ F .2d ___ (10th Cir. No. 436-69, August

27, 1969), reinstated ___ S. Ct. ___ (Mr.

Justice Brennan, Acting Circuit Justice,

August 29, 1969) .......................... 59

Downs v. Board of Educ. of Kansas City, 336 F.2d

988 (10th Cir. 1964), cert, denied, 380 U.S.

914 (1965) ................................ 30

Felder v. Harnett County Bd. of Educ., No. 12,894

(4th Cir., April 22, 1969) ............... 64

Gilbert v. Hoisting & Portable Engineers, 237 Ore.

139, 390 P.2d 320 (1964) ................. 64

Goss v. Board of Educ. of Knoxville, 373 U.S.

683 (1963) ................................ 45

Goss v. Board of Educ. of Knoxville, 406 F.2d

1183 (6th Cir. 1969) ...................... 31

Green v. County School Bd. of New Kent County,

Virginia, 391 U.S. 430 (1968)............. 4, 4-5, 30, 45

Griffin v. County School Bd. of Prince Edward

County, 377 U.S. 218 (1964)................. 45, 5 7

Haney v. County Bd. of Educ. of Sevier County,

410 F . 2d 920 (8th Cir. 1969) ............. 45, 46, 53, 56, 57

v

Page

Henry v. Clarksdale Municipal Separate School

Dist., 409 F .2d 682 (5th Cir. 1969) . . . . 46, 48

Holland v. Board of Public Instruction of Palm

Beach County, 258 F.2d 730 (5th Cir. 1958) 51

Houston Ind. School Dist. v. Ross, 282 F .2d 95

(5th Cir. 1960) ............................ 45

Jackson v. Marvell School Dist. No. 22, 389

F .2d 740 (8th Cir. 1968) ................. 53

Jackson v. Pasadena School Bd., 59 Cal. 2d 876,

31 Cal. Rptr. 606, 382 P.2d 878 (1963) . . 30

Kelley v. Altheimer, Ark. School Dist. No. 22,

378 F . 2d 483 (8 th Cir. 1967) ............. 45, 53, 57, 60

Kemp v. Beasley, 352 F .2d 14 (8 th Cir. 1965) . . 29, 53

Kemp v. Beasley, 389 F.2d 178 (8 th Cir. 1968)

Keyes v. School Dist. No. 1, Denver, Civ. No.

C-1499 (D. Colo., July 31, 1969; August

14, 1969), stay pending appeal granted,

F .2d (10th Cir. No. 432-69, August

27, 1969), stay vacated, S. Ct.

53, 55, 64

(Mr. Justice Brennan, Acting Circuit Justice,

August 29, 1969) .......................... 46, 59

Mapp v. Board of Educ. of Chattanooga, 373 F.2d

75 (6 th Cir. 1967) ........................ 31

McGhee v. Nashville Special School Dist., Civ.

No. 962 (W.D. Ark., June 22, 1967) . . . . 57

Monroe v. Board of Comm'rs of the City of Jack-

son, Tennessee, 391 U.S. 450 (1968) . . . . 5

Monroe v. Board of Comm'rs of City of Jackson,

Tennessee, 244 F. Supp. 353 (W.D. Tenn.

1 9 6 5 ) ....................................... 63

Moore v. Tangipahoa Parish School Bd., Civ. No.

15556 (E.D. La., July 2, 1969) ........... 59

Morean v. Board of Educ. of Montclair, 42 N.J.

273, 200 A.2d 97 (1964) ................... 30

Morris v. Williams, 59 F. Supp. 508 (E.D. Ark.

1944), rev'd 149 F .2d 703 (8 th Cir. 1945) . 27

vi

Page

Northcross v. Board of Educ. of City of Memphis,

333 F . 2d 661 (6 th Cir. 1964) ............. 49

Northcross v. Board of Educ. of City of Memphis,

Civ. No. 3931 (W.D. Term., May 15, 1969) . 58

Norwood v. Tucker, 287 F.2d 798 (8th Cir. 1961) 4, 27, 31

Plaquemines Parish School Bd. v. United States,

No. 24009 (5th Cir., August 15, 1969) . . . 56-57

Raney v. Board of Educ. of the Gould School

Dist., 391 U.S. 443 (1968) ............... 4, 5

Raney v. Board of Educ. of the Gould School

Dist., 381 F.2d 252 (8 th Cir. 1967), rev'd

391 U.S. 443 (1968)........................ 60

Ross v. Dyer, 312 F .2d 191 (5th Cir. 1963) . . . 45

Safferstone v. Tucker, 235 Ark. 70, 357 S.W.2d 3

(1962) ..................................... 10, 31, 32

Schine Chain Theatres v. United States, 334 U.S.

110 (1948) ................................ 57

Smith v. Board of Educ. of Morrilton, 365 F.2d

770 (8th Cir. 1 9 6 6 ) ........................ 53

Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Bd. of Educ., ___

F. Supp. ___, Civ. No. 1974 (W.D.N.C.,

April 23, 1 9 6 9 ) ............................ 49-50, 58-59

Taylor v. Board of Educ. of New Rochelle, 195 F.

Supp. 231 (S.D.N.Y.), aff'd 294 F .2d 36 (2d

Cir. 1961) ................................ 23

Turner v. Goolsby, 255 F. Supp. 724 (S.D. Ga.

1 9 6 5 ) ....................................... 57

United States v. Board of Educ. of Bessemer, 396

F . 2d 44 (5th Cir. 1 9 6 8 ) ................... 20

United States v. Greenwood Municipal Separate

School Dist., 406 F.2d 1086 (5th Cir. 1969) 46

United States v. Indianola Municipal Separate

School Dist., 410 F.2d 626 (5th Cir. 1969). 46

Vll

Page

United States v. Jefferson County Bd. of Educ.,

377 F.2d 836 (1966), aff'd on rehearing en

banc, 380 F.2d 385 (5th Cir.), cert, denied

sub nom. Caddo Parish School Bd. v. United

States, 389 U.S. 840 (1967).................. 59

United States v. Montgomery County Bd. of Educ.,

395 U.S. 225 (1969)....................... 20, 53

United States v. National Lead Co., 332 U.S. 319

(1947) 57

United States v. School Dist. No. 151 of Cook

County, 286 F. Supp. 786 (N.D. 111.), aff'd

404 F . 2d 1125 (7th Cir. 1 9 6 8 ) ............. 59

United States v. Standard Oil Co., 221 U.S. 1

(1910) 5 7

Walton v. Nashville Special School Dist., 401

F . 2d 137 (8 th Cir. 1968) ................. 53

Wanner v. County School Bd. of Arlington County,

357 F . 2d 452 (4th Cir. 1966) ............. 56

Yarbrough v. Hulbert-West Memphis School Dist.,

380 F . 2d 962 (8th Cir. 1967) ............. 53

Louisiana v. United States, 380 U.S. 145 (1965) 57

Table of Statutes and Other Authorities

42 U.S.C. §2000c-6 (Section 407 of the Civil

Rights Act of 1 9 6 4 ) ........................59

15 U.S.C. § 4 ........................................

8 8 Cong. Rec. 13820-21 .............................

Acts of Arkansas, 1961, No. 265 ........... 05

vfii

IN THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE EIGHTH CIRCUIT

NO. 19795

DELORES CLARK, et al.,

Appellants,

vs.

THE BOARD OF EDUCATION OF THE LITTLE

ROCK SCHOOL DISTRICT, et al.

NO. 19810

DELORES CLARK, et al.,

Appellees,

vs.

THE BOARD OF EDUCATION OF THE LITTLE

ROCK SCHOOL DISTRICT, et al.

Appeals from the united States District Court for the Eastern

District of Arkansas, Western Division

BRIEF FOR APPELLANTS - CROSS-APPELLEES

Preliminary Statement

This is an appeal and cross-appeal from the unreported order

of the united States District Court for the Eastern District of

Arkansas, Western Division, the late Gordon E. Young, United States

District Judge, entered May 16, 1969.

Issues Presented for Review

1. Whether the district court erred in accepting a zoning

plan which conforms to racial residential patterns and which fails

to create a system without racially identifiable schools.

2. Whether adherence to the neighborhood school concept

excuses the failure of a school district formerly segregated by

law to implement a unitary school system.

3. Whether a district court may require a school district to

furnish bus transportation or to raise additional funds necessary

to implement a plan for a unitary system.

4. Whether a plan of faculty desegregation which places

significantly lower percentages of Negro teachers in formerly white

schools than in Negro schools, and significantly lower percentages

of white teachers in Negro schools than in formerly white schools,

was properly approved and is consistent with the achievement of a

unitary system.

Statement

This appeal is the latest chapter in litigation begun in 1956

to desegregate the public schools of Little Rock, Arkansas (A. 7).

In that year, the district court approved a plan of gradual

integration which it found would "bring about a school system not

based on color distinctions," Aaron v. Cooper, 243 F.2d 361, 362

(8 th Cir. 1957). The complete history of the litigation is set out

2

in the margin. I/

1/ After Brown v. Board of Educ., 347 U.S. 483 (1954), the

Little Rock school board adopted a plan of very gradual

integration. When that plan was not implemented, Negro students

and their parents brought suit in 1956. The initial plan,

calling for complete desegregation by 1963, was approved by

the district court that year, Aaron v. Cooper, 143 F. Supp. 855

(E.D. Ark. 1956). This court rejected arguments that more

rapid desegregation should be required, in part for the reason

that the first plan had been voluntarily adopted by the school

board even before the second Brown decision (Brown v. Board of

Educ., 349 U.S. 294 (1955)). Aaron v. Cooper, 243 F.2d 361 (8th

Cir. 1957). Subsequently, when white parents obtained a state

injunction to prevent implementation of the plan in 1957-58,

the district court restrained compliance with the order of the

Arkansas court and mandated execution of the plan. Aaron v.

Cooper, 2 Race Rel. L. Rep. 934-36, 938-41 (E.D. Ark. 1957),

aff1d 254 F.2d 808 (8th Cir. 1958). The Governor of Arkansas

then took measures to prevent Negroes from attending classes at

the previously-white Central High School, including the

stationing of National Guardsmen with fixed bayonets at the school

with orders to prevent the entry of Negro students. This conduct

was enjoined in Aaron v. Cooper, 156 F. Supp. 220 (E.D. Ark. 1957)

aff1d sub nom. Faubus v. United States, 254 F.2d 797 (8 th Cir.

1958). However, intervention by federal troops under direct

order of the president of the United States was required to

effectuate compliance with the district court's orders and with

the Constitution. Cooper v. Aaron, 358 U.S. 1, 12 (1958).

After the conclusion of the 1957-58 school year, the board

sought to delay implementation of the plan for at least three

additional years because of the extent of white opposition to

integration. The district court's order approving a delay,

Aaron v. Cooper, 163 F. Supp. 13 (E.D. Ark. 1958), cert, denied,

357 U.S. 566 (1958), was reversed by this Court, 257 F.2d 33

(8 th Cir. 1958), aff1d sub nom. Cooper v. Aaron, 358 U.S. 1 (1958).

Pursuant to emergency measures passed by the Arkansas

Legislature in special session, the Governor of Arkansas then

ordered all Little Rock high schools [the desegregation plan

at that time extended only to the high school grades] to be

closed indefinitely. Thereupon, the board undertook to lease

its high school buildings to a segregated private school

corporation. The district court denied an injunction against

the leasing of the facilities, but this court reversed and

3

The instant proceedings were formally commenced in July 1968

with the filing of a Motion for Further Relief based upon Green v.

1/ (continued)

required issuance of the decree, Aaron v. Cooper, 261 F.2d 97

(8 th Cir. 1958). However, Little Rock public high schools

remained closed during the 1958-59 school year, see Aaron v.

Cooper, 169 F. Supp. 325 (E.D. Ark. 1959), until the Arkansas

school closing legislation was declared void by a three-judge

district court in Aaron v. McKinley, 173 F. Supp. 944 (E.D.

Ark. 1959)(per curiam).aff1d sub nom. Faubus v. Aaron, 361 U.S.

197 (1959).

The board then assigned pupils during the 1959-60 school

year on the basis of regulations adopted by it pursuant to the

Arkansas Pupil Placement laws, which required consideration

of a multitude of factors other than residence (<2.c[., "the

possibility of breaches of the peace or ill will or economic

retaliation within the community"). An attack upon these laws

was rejected by the district court, Aaron v. Tucker, 186 F.

Supp. 913 (E.D. Ark. 1960), but its judgment was reversed by

this Court, Norwood v. Tucker, 287 F.2d 798, 802 (8 th Cir. 1961),

which said, "[w]hile we are convinced that assignment on the

basis of pupil residence was contemplated under the original

plan of integration, it does not follow that the school officials

are powerless to apply additional criteria in making initial

assignments and re-assignments." This court found on the record

that the board's use of the pupil placement laws was "motivated

and governed by racial considerations," _id. at 806, and noted

that the board's "obligation to disestablish imposed segregation

is not met by applying placement or assignment standards,

educational theories or other criteria so as to produce the

result of leaving the previous racial situation existing as it

was before." Id_. at 809.

The Clark plaintiffs in 1965 complained of continued

manipulation of the Pupil Placement laws to limit the movement

of Negroes into previously all-white schools. The district

court so found. See Clark v. Board of Educ. of Little Rock,

369 F.2d 661, 665 (8 th Cir. 1966). While the district court's

opinion in that case was being prepared, the board determined

to abandon the Pupil Placement laws in favor of a "freedom of

choice" plan, subsequently approved by the district court and

by this Court with certain directed modifications. Clark v. Board

of Educ. of Little Rock, supra. After the Supreme Court's

opinions in Green v. County School Board of New Kent County,

Virginia, 391 U.S. 430 (1968) and Raney v. Board of Educ. of the

Gould School Dist., 391 U.S. 443 (1968), the present proceedings,

attacking free choice as an effective method of desegregation on

the basis of its actual performance in Little Rock, were started.

4

County School Board of New Kent County, Virginia, 391 U.S. 430

(1968) and companion cases. In that Motion (A. 5a-14a),

plaintiffs below sought — and plaintiff-intervenors sought in their

Complaint (see A. 27a-31a) — an order requiring the Little Rock

School District to abandon the free choice plan of desegregation

approved with modifications by this Court in Clark v. Board of

Educ. of Little Rock, 369 F.2d 661 (8 th Cir. 1966) and to adopt

and implement a plan of desegregation which "promises realistically"

to convert now to a unitary school system. After further proceedings,

the district court approved a geographic zoning plan submitted by the

board.

The Little Rock School District

At the present time there are five high schools, seven junior

high schools, and thirty-one elementary schools (Defendants' Exhibit

3/

No. 24, pp. 77 - 79 infra) in the Little Rock School District, serving

2/ Raney v . Board of Educ. of the Gould [Arkansas] School

Dist., 391 U.S. 443 (1968); Monroe v. Board of Comm'rs. of

the City of Jackson, Tennessee, 391 U.S. 450 (1968).

3/ Because of the size of the record, counsel agreed that

trial exhibits would not be reproduced in the Appendix. It

was further agreed that either side might print any desired

exhibits as appendices to its brief. The original file of

the district court, including exhibits, will also be

transmitted to this court.

5

an estimated 1969-70 student enrollment of 15,377 white students

and 8,281 Negro students (Defendants' Exhibit No. 25, pp. 80 -82

infra). As the district court noted in its Memorandum Opinion

(A. 895), the district generally forms an irregular rectangle with

the longer side running from east to west along the Arkansas River.

The most prominent exception to this pattern is the extension of

the district in two finger-like projections at its northwest end.

These have resulted from the district's annexation, since 1956, of

the white residential subdivisions of Walton Heights and candlewood.

Between the two "fingers" lies a Negro residential area known as

Pankey (A. 485-589). See Map 1.

6

•Terry

MAPI

Little Rock Public Schools 1956-1969

.̂'cDermott

•Williams

^iall ‘Forest Heights

•BradyHenderson

•Fair Park JPulaski Height

•Jackson

•Capital Hill «Kramer •Lee -West SideCentral'

•Parkview

Nomine

Woodruff

lap

•W<

•Franklin .Stephens “Cmtenmaf of} • ’arham Stephens .Dunbar Side looker

•Garland ’Rightsell *Bush

•Oakhurst -Mitchell ‘̂ n n

•Bale *Washington

•Southwest * sh

•Carver

Wilson

•Westeaya-

Hillsf

Gillam

llefedowcliff

i

l

•Grgjnite Mountain

» •

Since 1956 the district has expanded almost exclusively to the

1/

west. Of thirteen new school facilities opened since that year,

only three have been located in the east-central section of the

city: Booker Jr. High, Ish and Gillam Elementary Schools. All were

named for prominent Negroes (A. 473, 482); all were initially opened

as Negro schools (A. 473, 477, 482) with all-Negro faculties (Ibid).

5/

On the other hand, the district built nine schools in Western

Little Rock between 1956 and 1969: Parkview High School, Henderson

Junior High and Southwest Junior High Schools, Bale, McDermott,

Romine, Terry, Western Hills and Williams Elementary Schools. In

each instance, these schools were initially filled with an all-white

faculty (A. 154) and they have remained identifiable as "white"

schools (see Table 1, p. 34 infra).

4/ Expansion of the district has not benefited both white and

Negro citizens of Little Rock. Various urban renewal projects

since 1954 have eliminated areas of Negro residences near the

present Hall High School (A. 289) , and in Pulaski Heights

(A. 290-91). Of more than one hundred and seventy-five

subdivisions developed in Little Rock between 1950 and 1968

(Plaintiffs1 Exhibit No. 4), only two — Granite Mountain and

University Park — have Negro residents (A. 746). On the other

hand, William Meeks, a member of the Little Rock School Board

and Little Rock "Realtor of the Year" in 1967, testified of

discrimination against Negroes in the sale of housing (A. 743-44)

He said that he knew of no Little Rock realtor, even up to the

time of the hearing in this case, who would knowingly sell a lot

in a "white" subdivision to a Negro (A. 294). Newspaper

advertisements reflecting listings of sale property by race were

also introduced in evidence (Plaintiffs' Exhibit No. 3).

5/ The thirteenth facility opened since 1956 was Metropolitan

High School, a vocational-technical school serving both Little

Rock and the Pulaski County Special School District. It is

located outside the district’s boundaries.

8

When all-Negro Pfeifer and Carver schools became overcrowded,

the district did not offer Negro students a second choice of schools

(A. 315-16), but moved portable classrooms to the site to expand

the capacity of the schools and contain the Negro student population

(A. 498-99). In contrast, Hall High School was declared overcrowded

under the freedom-of-choice plan, necessitating the establishment of

an attendance zone. However, when the board drew the zone it made

no attempt to maximize desegregation in the school (A. 222-23).

In addition to staffing new schools with all-white or all-Negro

faculties, the district hired teachers on a strictly racial basis

through 1964-65 (A. 28); thereafter, all attempts to achieve faculty

integration were on a purely voluntary basis only (A. 255). And

prior to July 1968, except for two white principals at Negro schools,

the district maintained a racial allocation of prinicpalships, with

white principals at traditionally white schools and Negro principals

at "Negro" schools (A. 121-22).

In 1966, the district purchased a school site in Pleasant Valley,

an exclusively white upper-middle class subdivision (Defendants'

6 7 (continued)

to the Negro schools they were assigned to

attend; and none of the white pupils in the

geographic attendance area were reassigned.

Thus, when the district court required the

school board to provide the pupils assigned

to Negro schools an opportunity to make a

choice of schools in Byrd et al. v. Board

of Directors of the Little Rock School

District, Civ. No. LR 65-C-142, the character

of the new school had become an established

fact. The board had thus created by design

another "Negro" school and had again made

clear its unwillingness to either assign white

pupils to "Negro" schools or Negro pupils to

predominantly white schools.

12

Exhibit No. 30; A. 213, 485), again without any consideration of

the racial composition of the neighborhood or the past history of

segregation (A. 486). Any school constructed on the site (there is

a sign there announcing that a school will be built on the site)

would be all-white; were Pleasant Valley, Walton Heights and Candlewood

subdivisions not within the Little Rock district, the closest school

would be a predominantly Negro school in the pankey area (A. 488-89).

Finally, — and this list is by no means exhaustive of the means

by which this district maintained the segregated character of its

system -- the school district undertook to build a new senior high

school (parkview) in the far western section of the city in 1967

despite the availability of over four hundred vacant classroom spaces

at Horace Mann High School (A. 144-45). Three high schools could

still serve the high school population of the district (A. 131); the

overcrowding at the time was in junior high schools (A. 617-18). Of

course, parkview is clearly identifiable as a "white" school while

Mann is just as clearly a "Negro" school.

The Oregon and Parsons Plans

In 1966, the school board contracted with a team from the

University of Oregon to prepare a long range plan of desegregation

for the district (A. 61-62). The findings of that team were reported

in early 1967 and became known as the "Oregon Report" (Defendants'

Exhibit No. 7). Basically, the report recommended abandonment of the

neighborhood school concept and restructuring of the district's

schools through a capital building program combined with pairing to

13

create an educational park system (Ibid). The cost of implementing

the "Oregon Report" in its entirety was estimated to be some ten

million dollars; however, as the chief author and director of the

study (Dr. Goldhammer) explained, much of this amount would have

had to be expended for building replacement and remodeling anyway

(A. 367). The Oregon Report would also have required a transportation

system for the school district (Ibid).

Following issuance of the Oregon Report, a school board

election was held in November 1967. Two incumbent members of the

board who supported the recommendations of the Oregon Report were

replaced by candidates who campaigned against it (A. 416-18), and

the vote was interpreted as an indication (a) that the public would

not support implementation of the recommendations, and (b) that the

public would not vote bond monies or tax levies sufficient to implement

them.

The school board then directed the Superintendent and his staff

to prepare their own recommendations of a desegregation plan for

Little Rock (A. 69). After considerable study (A. 73), the

Superintendent's proposals were issued; they quickly became known

as the "parsons Plan" (A. 70; Defendants' Exhibit No. 10). The

Parsons Plan proposed measures to desegregate Little Rock high

schools and two groups of elementary schools, as follows: Horace

Mann High School would be discontinued as an upper grade center and

zones for Hall, Central and Parkview drawn across the city along

east-west axes; Franklin, Garland, Lee, oakhurst and Stephens

14

Elementary Schools would be paired in the "Beta" complex; and

several east Little Rock elementary schools would be closed, with

classes relocated in the Horace Mann building(Ibid). The plan

made no proposals for other elementary schools or for junior highs.

In March 1968, the board placed a $5 million bond issue for implementing

the parsons Plan on the ballot (A. 73-74). Although the Superintendent

campaigned for his plan, the millage increase for the bonds was

rejected (A. 75) and again, candidates favoring no change in the

status quo defeated incumbents who supported the Superintendent's

plan (A. 180-81. See also, A. 417-21).

Development of the plan Approved Below

After the district had responded to the Motion for Further

Relief, the district court set a hearing for August 15, 1968 and

suggested that the Board devise a geographic zoning plan (A. 32a).

The district did present a geographic attendace zone plan at the

August hearing (A. 76). However, this plan was characterized as

an "interim" measure (A. 320) which required further study (A. 91);

the district opposed making any change from freedom-of-choice for

1968-69 and the hearing was limited to whether or not a shift ought

to be required for 1968-69. After the second day of testimony, the

hearing was recessed in order to allow the district to develop and

present a final plan to completely disestablish the dual system

effective with the 1969-70 school year (A. 403-04). That plan was

submitted November 15, 1968 (A. 408d-408g).

15

Although the two plans were essentially similar, the

Superintendent testified that in November, unlike August, the

district had considered all other alternatives before determining

to submit the zoning plan:

1. The Oregon Report was rejected because it required money

to implement it (A. 415), because its abandonment of the neighborhood

school concept was considered educationally unsound (A. 67, 416),

and because it did not have public support (A. 416-17).

2. The parsons Plan was rejected because it, too, required

money for its execution and because it lacked community support

(A. 415-16) .

3. A plan developed and submitted by a group of Negro citizens

and organizations (pp. 16-25 of Defendants' Exhibit No. 19, pp. 83

8/

- 92 infra) — which was referred to as the "Walker Plan" — was

rejected because it required the district to raise funds to provide

1/

77 The Superintendent testified that there was no material

difference between the August and November elementary zones

(A. 509). The November submission included two exceptions

to assignment by zoning not contained in the August plan: 8th,

1 0 th and 1 1 th graders were to be given a choice between their

residence school and the school previously attended; and

children of teachers were to be permitted to enroll in the

school where their parent taught (A. 434-35). Other minor

differences occurred; for example: there would be fewer whites

in the Stephens zone under the November plan (A. 510); there

would be fewer whites at Mann under the later plan (A. 520)

(due to the choice feature, see A. 522) although the Mann zone

would extend further west (A. 521).

8/ This plan combined grade restructuring, pairing and an

extensive transportation system with recommendations for

future development of more centralized larger attendance

centers.

16

feature permitting rotation of high school zones, and because it

9/

paired schools separated by considerable distances (A. 424).

4. A plan proposed by board members Meeks and Woods to

retain free choice, but to reserve space for Negro students at

predominantly white schools (to avoid, for example, closing out

Negro choices at Hall High due to overcrowding, see A. 223) , was

rejected because of the difficulty of administering it (A. 426).

5. The Board also rejected a version of high school zone

lines presented to them by the Superintendent on October 10, 1968.

This version would have extended the Hall zone further southeast;

thereby placing 80 Negro students in Hall (A. 523-26; 631-32).

Although cost was a major factor in the decision to submit a

zoning plan, no cost analysis of the various alternative approaches was

ever requested or made (A. 513-14, 548-49). When the Superintendent

was reminded of his 1965 testimony that adoption of attendance zones

10/

would have been educationally destructive he stated that the

community had turned down all educationally desirable plans so that

zoning was the only remaining alternative (A. 556-67).

In drafting the zones submitted in November, the Superintendent

was not instructed to consider "racial balance" (A. 886-87); rather,

the primary concern was to avoid any inconvenience to students caused

9/ Particularly objected to was the pairing of Meadowcliff

Elementary and Granite Mountain Elementary Schools (A. 425).

However, transportation between the two schools is made

considerably easier by the location of Interstate Highway No.

30.

10/ Compare A. 551; Defendants' Exhibit No. 8 in 1965 trial,

referred to at A. 551 and reprinted here at pp. 93 - 94 infra.

a transportation system (A. 423), because it contained an optional

17

437, 514).

The plan Approved Below

1. Pupil Assignment

The November 15th plan of the school board establishes mandatory

attendance areas for all schools except the district-wide

vocational-technical facility, Metropolitan High School. The zone

boundaries are delineated on the map introduced as Defendants'

Exhibit No. 22. All students must attend the school serving their

grade level in their zone of residence except (a) students attending

Metropolitan High (A. 434); students in the eighth, tenth and eleventh

grades in 1968-69, who may choose between the school in their zone of

residence and the school they previously attended (A. 435); and (c)

children of teachers employed by the district, who may enroll at the

school where their parent is employed (A. 434).

The zones were approved as submitted except that the district

court required (A. 912-13) that the Hall High School zone be redrawn

in accordance with the October 10th proposal of the Superintendent

putting 80 Negro students in Hall High School (which had been

rejected by the Board).

The Superintendent testified that unless Negro teachers enrolled

their children in the schools in which they taught, the board's zoning

plan would result in a greater number of all-white elementary schools

than there had been under freedom of choice (A. 529-30). Indeed, he

had estimated that the August zone plan — very similar to the

by distance or the requirement of transportation (A. 78, 323-24,

18

November plan but without the option for teachers' children —

would have resulted in all-white schools in Western Little Rock and

11/

all-Negro schools on the east side (A. 160). Fewer Negro students

would attend predominantly white schools under the zoning plan than

had been enrolled in such schools under freedom of choice (A. 534-35);

there will be "very little" integration under the zoning plan (A. 162)

since the zones were drawn in a manner that allowed schools to remain

all-white and all-Negro (see A. 434).

Most of the witnesses at the hearing agreed that the parsons

Plan was a better integration plan, at least at the high school

levels, than the board's zoning proposal (A. 129 [superintendent

parsons], 194 [Board President Barron], 298-99 [Board member Meeks],

678 [Dr. Dodson], 819 [Dr. Goldhammer, principal author of the

Oregon Report]). The Superintendent also testified that various

zones drawn in the board's plan, such as those for Gillam Elementary

and Hall High Schools, did not further the goal of integration (A. 158).

From his study of the board's proposals, Dr. Goldhammer concluded that

they did not provide for a unitary school system, and would not be an

Because the zoning plan, in its failure to integrate schools

in Western Little Rock, preserves their racial identity and

encourages accelerated resegregation by whites. See A. 669-70.

(Appellees accuse us of taking both sides of the issue of

resegregation. There is nothing inconsistent in our position:

the possibility of resegregation cannot serve as an excuse

for failure to move to a unitary system, e_.g_., Anthony v.

Marshall County Bd. of Educ., 409 F.2d 1287 (5th Cir. 1969)

but it is proper, in evaluating a plan, to consider whether

continued racially identifiable schools will act as a goad

to encourage it.)

19

improvement over the free choice plan (A. 381-82).

12/

2. Faculty

The district's proposal for faculty desegregation was drawn

up in accordance with the district judge's letter suggestion

(A. 32a) that the racial division of faculties in each school

approximate the racial breakdown among faculty in the entire

13/system.

Although the racial breakdown of faculty in the Little Rock

public schools is 82% white and 18% Negro (A. 446), the percentage

of white teachers in each of the several schools under the plan

varies from 56% to 85%, and that of Negro teachers varies from 15%

to 44% (Table 1, pp. 34 - 3 7 infra; Defendants' Exhibit No. 25,

14/

pp. 80 - 82 infra). The result of the assignment pattern thus

12/ E. C. Stimbert, Superintendent of the Memphis, Tennessee

public school system, was called as an expert witness by

appellees. He strongly supported the neighborhood school

concept, which he termed the "only valid educational theory"

(A. 622) and zoning as the only "educationally sound and

administratively feasible" method of pupil assignment (A. 586),

but he explicitly disclaimed any intention to evaluate the

zones proposed in the board's plan (A. 613). He further stated

that east-west ("strip") zoning [proposed for high schools in

the parsons Plan] which would achieve better racial balance

would be "no better or no worse” educationally than any other

zoning plan (Ibid).

13/ See United States v. Montgomery County Bd. of Educ., 395

U.S. 225 (1969); United States v. Board of Educ. of Bessemer,

396 F .2d 44 (5th Cir. 1968).

14/ The Superintendent explained that the 18% figure had been

reduced to 15% and the 82% figure increased to 85% to permit

"a three per cent flexibility" (A. 446). However, while the

20

proposed is that at each grade level, the formerly Negro schools

have a higher percentage of Negro teachers than do the formerly

white schools (A. 537-41). For example, Central, Hall and parkview

[all schools which are racially identifiable as "white" schools]

will have 15% or 16% Negro faculties, but Horace Mann will have a

29% Negro faculty. Similarly, those junior high schools which are

identifiable as white, either historically or because they were

constructed after 1956 in white neighborhoods and initially staffed

with an all-white faculty, are each to have faculties whose Negro

composition ranges from 19% to 22%. Negro Dunbar and Booker Junior

High Schools, however, will have 43% and 44% Negro faculties,

respectively. Finally, the percentage of the faculty at the district's

"white" elementary schools ranges from 27% to 33% in all schools

except Centennial, Kramer and Lee. The percentages of the faculty

at each of these three schools which will be Negro is 37% at Kramer,

14/ (continued)

projected assignments of Negro teachers vary from the actual

percentage of Negro teachers in the system only 3% downward,

they vary upward some 26%. The projected assignment pattern

for white teachers likewise varies only 3% upward from the

actual, but also some 26% downward from the actual. in

other words, had the district determined to make faculty

assignments so that the ratio of white to Negro teachers

approximated the ratio of white to Negro teachers in the

entire system, and then defined "approximate" to mean "not

varying more than three per cent from the actual percentage

ratios," then Negro teachers would make up between 15% and

2 1% of each school's faculty, and white teachers between

79% and 85% of each faculty. The "three per cent

flexibility" has in each instance been applied to only one

end of the scale.

21

38% at Lee, and 43% at Centennial. No Negro elementary school

has less than a 41% Negro faculty, however, and seven out of nine

black elementary schools will have faculties 43% or more Negro

(Table 1, pp. 34 - 37 infra; Defendants' Exhibit No. 25, pp. 80

82 infra) .

The only explanation which the Superintendent could offer

for this pattern was that the district was "attempting to develop

a plan that will fall within the guidelines which we have proposed

to the court for the first year that will prevent us from losing

any more teachers than we absolutely have to. . . . This is an

unpleasant and an uncomfortable experience for teachers. Consequently,

we have no desire to make any more of them uncomfortable and unhappy

about it than we have to." (A. 538).

The school district had not conducted a survey to determine

how many teachers would willingly transfer to schools in which

their race would be in a minority (A. 104) and had not in its program

of encouraging "voluntary" transfers across racial lines used a

similar study which had been conducted several years before (A. 107).

The Assistant Superintendent for Personnel, who was charged

with implementing the "voluntary" faculty desegregation in Little

Rock, testified that the only justification for the fact that Mann

High School and the other "Negro" schools in Little Rock would have

a substantially higher percentage of Negro teachers than each of the

15/ Centennial Elementary School, a white school under segregated

operation, became a majority Negro school in 1968-69 by

operation of the free choice plan; Kramer had a 46% Negro

enrollment in 1968-69 and Lee a 39% Negro enrollment during

that year.

15/

22

formerly white schools was because of teacher resistance to

desegregation (A. 796-97). In addition, he stated that the plan

made no provision for assignment of principals so that every Negro

school except those which had white principals in 1968-69 would

have Negro principals in 1969-70, and every formerly white

school would have white principals (A. 797).

Alternatives Available to the District

At the trial of this case, plaintiffs called two expert

witnesses to evaluate the plan submitted by the Little Rock School

District in light of educationally feasible alternatives which

appeared susceptible of implementation in Little Rock: Dr. Dan

Dodson and Dr. Goldhammer. The school district called Dr. E. C.

Stimbert, Superintendent of the Memphis school system, who

testified of his evaluation.

Dr. Dodson is Chairman of the Department of Education,

Sociology and Anthropology of the School of Education at New York

University (A. 655). His extensive qualifications are set out in

the record between pages A. 655-58. He has formulated desegregation

plans for numerous school systems, including that involved in Taylor

v. Board of Educ. of New Rochelle, 195 F. Supp. 231 (S.D.N.Y), aff'd

294 F.2d 36 (2d Cir. 1961) (A. 658). Dr. Dodson characterized a

school district operating under the zones proposed by the school

board in November 1968 as a "racist” school system, and said that

the zones freeze in the segregated character which the schools have

23

developed in the past (A. 6 8 6). He recommended implementation of

a plan not based on the neighborhood school concept (A. 673-74).

He traced the origin of the concept to the "common school" notion

at the base of public education (A. 658-59) but said that the

neighborhood school had become "a place where people who are more

privileged try to hide. . . and it's been made sacred in recent

thinking about in proportion as Negroes get close to it. It has

become an exclusive device, that is the opposite of the community

school" (A. 659). Dr. Dodson pointed out that in a city with

racially segregated housing patterns, effective desegregation could

not be accomplished if the neighborhood school concept were adhered

to (A. 673-74). Only by eliminating the racial identities of the

schools and allowing them to take on new identities as common

16/

schools could an integrated unitary system be achieved (A. 681-82).

He discussed alternative approaches used in other districts

(A. 674-76) and suggested that federal funds would be available for

transporting students (A. 676-77).

He was of the opinion that if Little Rock's high schools were

to be zoned to desegregate them, the zones should have been drawn

from east to west as in the parsons Plan (A. 678).

Dr. Goldhammer testified that the initial study of the Little

Rock School District by the team which drafted the Oregon Report

demonstrated that the district's progress in eliminating the dual

system was much slower than could have been expected; that considering

16/ See Cato v. Parham, 403 F.2d 12, 15, n. 7 (8th Cir. 1968).

24

the rapid growth in enrollment in the school system, free choice

17/

would never have worked (A. 357-58). Whereas the board's plan

proposed to zone all schools, the university of Oregon team had

concluded that in a residentially segregated community such as

Little Rock, no single approach would do the entire job of

conversion to a unitary system (A. 365). The Oregon team's

recommendations therefore incorporated several different features:

a capital construction program to develop educational parks and

larger attendance centers, pairing some schools and a bussing system

of student transportation (A. 365-67). Although the report carried

a cost estimate of $10 million, this price included considerable

replacement or modernization of facilities which would have had to

be carried out irrespective of any desegregation plan (A. 367). The

cost of coming as close to the Report as possible without abandoning

or remodeling buildings would require less than $500 thousand, for

bussing, inservice training and compensatory education programs

(A. 368-69).

Dr. Goldhammer said that the parsons Plan, the Oregon Report

and the "Walker" plan were each better means of desegregating the

schools than the board's zoning proposals (A. 399, 819). (He

estimated that the "Walker" plan would be the least expensive to

implement, A. 821) . The Board president, also, was of the opinion

that these plans would result in more integration in the Little Rock

17/ Superintendent parsons stated that he_ had never expected

white students to choose identifiably Negro schools under

freedom of choice (A. 330-31).

25

public schools than would be accomplished under the zoning plan.

They would thus eliminate the racial identifiability of the schools,

something which the zoning plan would fail to achieve (A. 762).

See also, A. 298, 636.

The district rejected these alternatives because they each

required expenditure of funds which Little Rock voters had

demonstrated, by their votes on the bond issues, that they would

not provide (A. 334, 337-40, 415-23, 428, 456, 653-54). The

Superintendent said, in fact, that the community had "turned down

every educationally desirable plan and now we are left with only

zoning as a feasible plan" (A. 556-557). Some funds were available

to the district, however, including State monies for a transportation

system (A. 341-43, 641-46) and Dr. Goldhammer suggested that funds

might have to be diverted in order to accomplish unification of the

system (A. 821).

26

ARGUMENT

Introduction

This is the oldest school desegregation case pending in this

Circuit. Its antecedents go back to 1945 when this Court required

appellee district to eliminate salary differentials between white

and black teachers. Morris v. Williams, 149 F.2d 703 (8th Cir.

1945), rev1g 59 F. Supp. 508 (E.D. Ark. 1944).

The goal of this litigation has always been what this Court

early recognized that the Constitution demanded — "a school system

not based on color distinctions." Aaron v. Cooper, 243 F.2d 361,

362 (8th Cir. 1957).

The district, however, has seized every opportunity to avoid

fulfilling the constitutional mandate. Each new scheme which it

has developed has sooner or later been declared ineffectual and

18/

invalid by the courts. This appeal presents for review the latest

18/ The district's efforts to postpone desegregation were

rejected in Aaron v. Cooper, 257 F.2d 33 (8th Cir.), aff1d

358 U.S. 1 (1958); its attempt to transfer its facilities

to private schools in Aaron v. Cooper, 361 F.2d 97 (8th Cir.

1958); its manipulation of the pupil placement laws in

Norwood v. Tucker, 287 F.2d 798 (8th Cir. 1961) and its

refusal to fairly administer its free choice plan in Byrd

v. Board of Directors of Little Rock School Dist., Civ. No.

LR 65-C-142 (E.D. Ark. 1965). The district has consistently

adopted "new plans" when it became clear that execution of

the old plans would no longer withstand judicial scrutiny.

For example, after the schools reopened in 1959 (see n. 1

supra), the district utilized the pupil placement laws to keep

Negroes out of white schools (Norwood v. Tucker, supra)

instead of continuing and accelerating the plan proposed by

the board in 1956 (see Aaron v. Cooper, 143 F. Supp. 855 (E.

D. Ark. 1956). In 1965, after further instances of

manipulation of the pupil placement laws had been demonstrated,

Clark v. Board of Educ. of Little Rock, 369 F. 2d 661, 664-65

(8th Cir. 1966), the district adopted a so-called freedom of

choice plan in the middle of pending litigation. Id. at 665.

27

proposal offered by the school district, which is to establish

designated attendance zones for every public school except the

district-wide vocational-technical facility.

The differences between appellants and appellees on the trial

of this matter can be summarized simply. In appellants' view, the

zoning plan adopted by the district in preference to better plans,

even those prepared at its request (by its Superintendent and by

a team of experts retained by it), will neither disestablish the

racial identities of its schools nor create a unitary system; the

zones were drawn so as to inconvenience as little as possible, the

district's white parents whose children attend all-white schools.

We believe the district cannot, under the Constitution, use the

neighborhood school concept to justify this intended result, we

also challenge the plan for "faculty desegregation" because it too

perpetuates the racial labelling of schools which appellees have

effected by their past actions.

The district, on the other hand, defends its plan with these

notions: (a) it satisfies its constitutional obligation by drawing

rational zones even though the racial concentrations at most schools

are unchanged, because to require zones which achieved more integration

would be to require "racial balance," which the Constitution forbids;

(b) zoning is the only feasible alternative to freedom of choice

because of community hostility manifested by failure of bond issues;

and (c) any other plan or any other pattern of zoning would necessitate

the bussing of students, which the Constitution and the Civil Rights

28

Act of 1964 prohibit the district court from requiring.

I

The Little Rock Zoning Plan For Pupil

Assignment Is Unacceptable Because It

preserves the Racial Identity Given

Each School By Appellees' Own Past

Policies and practices

The quintessential issue in this case is not "bussing" or

"racial balance" or "resegregation." It is whether a formerly

segregated school system fulfills its constitutional obligation to

establish a unitary system by adopting attendance zones which only

insignificantly alter the pattern of separate racial attendance in

its schools. This question is neither novel nor difficult. The

school district's contention — that by simply drawing "rational"

attendance zones without accomplishing desegregation, it has created

a unitary system, in spite of the fact that the same schools are

attended by the same heavy concentrations of Negro and white students

as before — is nothing more than a thinly veiled version of the

Briggs dictum. That doctrine, of course, has been long since

explicitly rejected by this Court, Kemp v. Beasley, 352 F.2d 14, 21-22

(8th Cir. 1965).

As the Supreme Court has recently said,

Brown II was a call for the dismantling of

well-entrenched dual systems tempered by an

awareness that complex and multifaceted

problems would arise which would require time

and flexibility for a successful resolution.

School boards such as the respondent then

operating state-compelled dual systems were

nevertheless clearly charged with the

affirmative duty to take whatever steps might

be necessary to convert to a unitary system

in which racial discrimination would be

eliminated root and branch.

29

Green v. County School Bd. of New Kent County, 391 U.S. 430, 437-38

W(1968) (emphasis supplied). The issue framed on this record is

whether implementation of the zoning plan approved below is an

appropriate response to the charge Brown II directed to this school

20/

district.

The harsh reality in Little Rock is that under the zoning plan,

the schools into which Negro children were shepherded (whether by

segregation law or assignment by the school board) are the same

schools which will be attended by the bulk of Negro students in the

future. Similarly, the institutions which the district built and

19/ See also, Cooper v. Aaron, 358 U.S. 2, 7 (1958), where the

court said this very district was "duty bound to devote every

effort toward initiating desegregation and bringing about the

elimination of racial discrimination in the public schools

system."

20/ This case does not involve a claim for relief from school

segregation not shown to have resulted from officially sponsored

and supported state action. Thus, the several "racial imbalance"

or so-called "de facto," cases of Bell v. School City of Gary,

Ind., 213 F. Supp. 819 (N.D. Ind. 1963), aff1d 324 F.2d 209

(7th Cir. 1963), cert. denied, 377 U.S. 924 (1964), Downs v.

Board of Educ. of Kansas City, 336 F.2d 988 (10th Cir. 1964),

cert. denied, 380 U.S. 914 (1965), Barksdale v. Springfield

School Comm., 348 F.2d 261 (1st Cir. 1965), and Deal v.

Cincinnati Bd. of Educ., 244 F. Supp. 572 (S.D. Ohio 1965),

aff1d 369 F.2d 55 (6th Cir. 1966), cert. denied, 389 U.S. 847

(1967), are inapposite. As an aside, however, we might note

that the right to such relief has been sustained in Booker v.

Board of Educ. of Plainfield, 45 N.J. 161, 212 A.2d 1 (1965);

Balaban v. Rubin, 40 Misc. 2d 249,242 N.Y.S. 2d 974 (Sup. Ct.

1963), rev'd,20 A.D. 2d 438, 248 N.Y.S. 2d 574 (2d Dept.),

aff'd 14 N.Y. 2d 193, 199 N.E. 2d 375, 250 N.Y.S. 2d 281 (1964),

Cert, denied, 379 U.S. 881 (1964); Morean v. Board of Educ. of

Montclair. 42 N.J. 273, 200 A. 2d 97 (1964); Jackson v.

Pasadena School Bd.. 59 Cal. 2d 876, 31 Cal. Rptr. 606, 382

P. 2d 878 (1963); Blocker v. Board of Educ. of Manhasset, 226

F. Supp. 208 (E.D. N.Y. 1964); Barksdale v. Springfield School

Comm., 237 F. Supp. 543 (D. Mass. 1965), vacated without

prejudice, 348 F.2d 261 (1st Cir. 1965).

30

operated for white students will serve white students almost

exclusively, in other words, there is still a school system "based

on color distinctions," Aaron v. Cooper, 243 F.2d 361, 362 (8th Cir.

21/

1956) .

The lengthy record in this case documents in considerable

detail the policies and practices of the Little Rock School District

for some thirteen years. During that time, although the district was

in theory proceeding to end racial discrimination in its public

schools, it engaged in all sorts of actions which reinforced

segregation (see pp. 8 - 13 supra). It refused to assign

qualified Negroes to white schools, Norwood v. Tucker, 287 F. 2d 798

(8th Cir. 1961). It deliberately converted a school attended by

whites into a school attended solely by Negroes, through direct

reassignments, Safferstone v. Tucker, 235 Ark. 70, 357 S.W. 2d 3 (1962).

It deliberately opened new schools as either "white" schools or

"Negro" schools — locating new facilities of limited size in the

heart of residential concentrations of one race or another, staffing

21/ Appellants take note of the Sixth Circuit's decision in Goss

v. Board of Educ, of Knoxville, 406 F.2d 1183 (1969) rejecting

the argument that continued racially identifiable schools are

inconsistent with the constitutionally required unitary system.

Insofar as the Sixth Circuit relied on Deal v. Cincinnati

Bd. of Educ., 369 F.2d 55 (6th Cir. 1966) in reaching this

conclusion in Mapp v. Board of Educ. of Chattanooga, 373 F.2d

75, 78 (6th Cir. 1967) and in Goss, id. at 1186, the decision

is inapposite. See n. 20 supra. We believe the Sixth Circuit

is wrong, and that it has completely failed to grasp the point

of the Supreme Court's decision that a unitary system was one

in which there were "just schools," not racially identifiable

"Negro" and "white" schools.

31

these new buildings with faculty members of that particular race

and assigning only students of that race to the schools (A. 17a-20a,

153-54, 464-77, 482, 486, 505-08, 637). It hired and assigned

teachers on a racial basis without exception through 1964-65 (A. 28)

and coaching staffs on that basis through 1967-68 (A. 267). It

consistently rejected opportunities to bring about more desegregation

(A. 478, 482, 498-99).

Small wonder, then, that the vestiges of segregation persist

in this school district. As a result of appellees' policies and

practices, every school in this district is plainly identifiable by

race, just as if the words "for whites" or "for Negroes" followed

22/

after its name. This is reflected in the enrollment statistics

22/ One group of schools shares an identity as Negro schools

because they were so operated prior to 1956: Dunbar, Mann,

Bush [now closed], Capital Hill [now closed], Carver, Granite

Mountain, Gibbs, Pfeifer, Washington, and Stephens.

Another group consists of schools identifiably white because

they were segregated prior to 1956: Central, East Side [now

closed], West Side, Forest Heights, Pulaski Heights, Kramer,

Parham, Centennial, Mitchell, Garland, Oakhurst, Franklin, Lee,

Jackson [now closed], Fair Park, Forest park, and Jefferson.

Schools racially identifiable as Negro schools because of

their location and initial faculty and student assignments are

Gillam (A. 473-74; Defendants' Exhibit No. 5, pp 66 - 76

infra), Booker (A. 476-79; Defendants' Exhibit No. 5, pp. 66

- 76 infra), and Ish (A. 482-83; Defendants' Exhibit No. 5,

pp. 66 - 76 infra). Rightsell Elementary School, which

was "converted" by the district from an all-white to an all-

Negro elementary school in 1961 (A. 166-67; Safferstone v.

Tucker, supra) is also placed in this category for convenience.

Finally, a fourth group of schools may be identified as

white by location, staffing and initial pupil assignment:

Terry, McDermott, Romine, parkview, Henderson, Williams, Hall,

Bale, Southwest, Wilson, Western Hills, Brady and Meadowcliff.

(The last two schools were built by the Pulaski County Special

School District and became part of the Little Rock district by

annexation).

32

contained in Table 1, following this page.

23/

23/ Defendants' Exhibit No. 25 (see A. 453; pp. 80 - 82

infra) listed 1968-69 enrollments for each school in the

system together with a projection of the 1969-70 enrollment

under the zones prepared by the board. This data has been

transferred to Table 1, which contains the following

information: (a) enrollment, by race, in Little Rock high

schools and junior high schools during 1955-56; (b) enroll

ment, by race, in all Little Rock public schools during 1960-

61; (c) enrollment, by race, in Little Rock public schools

during 1964-65; (d) enrollment, by race, in Little Rock

public schools during 1968-69; (e) projected enrollments in

Little Rock high schools and junior high schools under the

proposed zoning plan submitted by the school board in

Cooper v. Aaron, 143 F. Supp. 855 (E.D. Ark. 1956); (f)

projected enrollments in Little Rock public schools under

the proposed zoning plan discussed at the trial of Clark v.

Board of Educ. of Little Rock, 366 F.2d 661 (8th Cir. 1966)

(g) projected enrollments in Little Rock public schools

under the proposed zoning plan submitted by the board in

August 1968; (h) projected enrollments in Little Rock public

schools under the proposed zoning plan submitted by the

board in November 1968; and (i) proposed faculty allocation,

in percentages by race, to each Little Rock public school

under the plan submitted by the board in November 1968.

33

TABLE 1

(Segregation)

1956

Enrol

lment

1960-61 19614.-65 1968-69 Zones Zones

Enrol- Enrol- Enrol- 1956 1965

lment lment lment Plan Plan

(Pupil (Limited

Placement) Free Choice) (Free Choice) (Aaron) (Clark I) (Clark II)

Zones Zones

8/68 11/68

Plan Plan

Faculty

Assignments

School W N w N w N W N W N W N W N W N w N

HIGH SCHOOLS

% %

White:

o1' 337~//Central 2U75 1686 7 2206 76 151+2 512 2107 2005 210 121+9 61+1+ 11+1+7 1+81 85 15

Hall — — 8814 5 151+0 18 1U36 U 835 0 11+58 60 11+08 3 1361 1+ 81+ 16

Parkview

Negro:

----------- — — — — — 519 I46 — -------“ “ “ “ “ “ “ 863 56 729 52- 81+ 16

1

Mann

JR. HIGH SCHOOI

0

s

582 0 821 0 1239 0 801 363 I4I3 359 1065 233 912 66 978 71 29

1

White:

East Side 852 0 606 0 — — — — 355 255 — — — — — — - — —

West Side 1268 0 1006 0 9 b 7 36 657 318 807 283 252 738 1+71 398 1+95 395 80 20

Pulaski Heights 1+83 0 880 0 800 12 613 36 6I1I4 Uo 779 39 672 65 61+9 56 78 22

Forest Heights 678 0 851+ 0 975 b 10U0 8 760 0 937 1 908 0 901+ 1+ 81 19

Henderson — — — — 1+52 b 822 16 — — 683 66 808 2 813 0 79 21

Southwest

c

938 0 9 9 b 2 987 27 866 51+ 966 1+2 859 62 911+ 1+1 80 20

■tym̂n<

i p:

n

%

63

66

33

32

63

33

29

28

28

29

37

38

TABLE 1 (continued) p. 2

(Pupil (Limited

Placement) Free Choice) (Free Choice) (Aaron)

I96O-6I 1966-65 1968-69 Zones

(Clark I)

Zones

(Clark II)

Zones

Enrol- Enrol- Enrol- 1966 1966 8/68

lment_______lment_______ lment Plan Plan Plan

w N ¥ N W N W N W N w N

0 1607 0 962 0 685 283 717 289 666 79 800

0

2/

669“ 0 756 0 703 252 738 136 705

662 0 608 0 501 3

1

369 0 661 11

686

3/0“ 669 0 • 669 1 657 0 665 0

283 0 306 10 138 202 217 29 129 169

366 0 266 0 253 0 208 0 227 0

632 0 666 0 383 2 651 0 370 1

706 0 669 0 511 11 607 56 526 61

637 0 371 0 283 15 263 1 213 7

266 0 278 3 — — 250 89 — —

672 0 612 0 513 0 623 0 536 0

367 0 283 0 91 7 6 139 63 118 95

633 0 376 2 210 155 267 16 218 70

Zones

11/68

Plan

TABLE 1 (continued) P- 3

(Pupil (Limited

(Segregation) Placement) Free Choice) (Free Choice) (Aaron) (Clark I) (Clark II)

1936

Enrol

lment

1960-61

Enrol

lment

196U-63

Enrol

lment

1968-69

Enrol

lment

Zones

1936

Plan

Zones

1963

Plan

Zones

8/68

Plan

Zones

11/63

Plan

Faculty

Assignments

11/68 Plan

School W N W N W N W N W N W N W N W N W N_____.

ELEMENTARY SCHdOLS

White:

McDermott — — — — UU8 1 — — — — m b 0 hl2 0 69 31

Meadowcliff b 2 9 0* U 99 0 379 0 U83 0 533 0 333 0 73 27

Mitchell 379 0 333 27 ia 3 3 b 276 23 102 292 97 290 . 67 33

Oakhurst U73 0 396 2 281 33 » 360 31 330 2 b 330 2 b 69 31

Parham U38 0 U07 0 270 81 209 130 187 1 5 b 199 161 71 29 v

Pulaski Heights 369 0 3co 0 I4I16 3 U3o 7 333 0 333 0 69 31 .

Romine - 336 0 1*81 7 316 97 U33 86 380 100 380 100 72 28

Terry _____ ______ 267 0 U90 0 2U2 0 b b 2 0 b h 2 0 72 28

Western Hills — — 178

b /

12“ 206 6 — — 20 b 0 2 0 b 0 67 33

Williams U23 0 613 0 7U3 6 392 2 616 3 616 3 67 33 |

Wilson 8U3 0 331 10 1411 77 321 11 U37 U6 U37 U6 70 30

Woodruff 329 0 328 2 212 62 233 0 216 18 232 b 6 70 30

Negro: I

Bush 0 196 0 199 0 113 — — — — — — —

Capital Hill

c

0 U37 0 237 “ “ “ — — — — “ “ “ “ — —

>

r

t- -

TABLE 1 (continued) p. b

Segregation)

1956

Enrol

lment

(Pupil

Placement)

1960-61

Enrol

lment

(Limited

Free Choice)

196U-65

Enrol

lment

(Free Choice)

1968-69

Enrol

lment

(Aaron)

Zones

1956

Plan

(Clark I)

Zones

1965

Plan

(Clark II)

Zones

8/68

Plan

Zones

11/68

Plan

Faculty-

Assignments

11/68 Plan

School W N W N W N W N W N W N W N W N w N

ELEMENTARY SCH( OLS % %

Negro: -

5/

Carver 0 785 0 90U 0 8U2 28U 731~ 16 79U 16 79U 56 b b

Gibbs 0 839 0 U97 0 390 70 28 9 20 317 U8 389 56 U b

Gillam 0

2/

188" 0 185 0 213 — — 18 11a 18 liil 56 b b

Ish — — 0 6/587" 0 58 9 391 355 13 606 8 U8U 56

Granite Mountaj n 0 557 0 U76 0 L66 12 61 Ij. 0 U71 0 U71 59 b i ,

Pfeifer 0 136 0 178 0 190 ’ 281| 731^ lU H 41 lU 1U1 57 U3

Rightsell • 0 373 0 901 0 390 109 329 51 39U 5U 390 56 liU

Stephens 0 L86 0 582 0 369 1U5 369 83 365 3 b 313 57 b 3

Washington 0 538 0 580 0 506 b h U99 10 505 7 L83 58 b 2

i

1/ Including Te hnical High S :hool students 2/ Initial Enrollment 1 ) 6 3 - 6 k 3/ Initial Enrc .lment 1961-6 l

!

k / Initial Enro!.lment 1966-67 5/ Carver- Pfeifer 5/ Initial Enrc .lment 1965-6

Sources: Defen lants1 Exhibit No. 5, PP-4t> -7(o infra No. 12, 13, N3. 2 b , pp.17 -7<) infra; No. 25, PP-80 - 33 infra; Defendani s1 Exhibit

No. 8 in 1965 Clark trial, PP - ̂ 3 -5*/ infra; stiiulations of counsel, Aaron v. Cooper , 1U3 F. Supp. 855 (E.D. Ark. 1956. , PP- 35"- ^

infra *

•

Analysis of the Table shows the following:

1. Free choice had not, as late as 1968-69, eliminated the

racial identifiability of any Negro school. No white student had

ever chosen to attend such a school.

2. The zones proposed by the board will not eliminate schools

identifiable as Negro schools. No such school will have more than a

12.5% white enrollment, although whites outnumber Negroes in the

district.

3. The high school and junior high school zones proposed in

1956, see Aaron v. Cooper, 143 F. Supp. 855 (E.D. Ark. 1956), would

have resulted in more substantial numbers of whites attending Negro

24/

schools at those levels than the zoning plan approved below.

4. Free choice had little effect on racially identifiable

white schools as late as 1968-69. Central High Schoool, although

enrolling a significant number of Negro students, remained a white

school both because of its history and in comparison with Hall, Mann

and Parkview schools. Only Centennial, Kramer and Lee seemed to

have lost their "white only" existence; Mitchell had converted to

a heavily-Negro school. However, comparison with remaining all-white

or 95+% white schools made it clear that the system had undergone no

fundamental change and that even these schools were racially

identifiable.

5. The district's present zoning plan will not eradicate the

racial labelling of the white schools. There will be more all-white

elementary schools than under freedom of choice (A. 529-30). Fewer

24/ Counsel have been unable to determine 1956 projected

enrollments for elementary school zones.

38

Negro students, however, would be enrolled in these schools than

had been the case under the free choice regime (A. 534-35).

Some of the data in Table 1 has also been reproduced in a

25/

different form on Maps 2, 3, 4, 5 and 6, following.

%

25/ Map 2 presents the Little Rock schools divided into four

groups, based upon derivation of their racial identities, as

reflected in n. 22 supra. Map 3 summarizes this information

in two categories: white schools and Negro schools. Map 4

plots 1968-69 enrollments under free choice, separating schools

with enrollments more than or less than 50% Negro. Map 5

provides the same information pursuant to the zoning plan

approved below; Map 6 details in more categories the Negro

enrollment projections pursuant to the zones approved below.

39

*

jjTiaM°py°n

ux-cq. -tinoji eq.xm.ie. ^IIT3

~ z

uoq9uxqsT3M»

uu\j .

llsI*

XX©qolxn

ueno. II»SW STH.

n a .TBqung.

JBiN.Jt 'wkJ9

jc q o o g » epi , -ruxtaxg;,! [6Q

1 • ’V. ) sqd̂T-n *

3 X X TIIjiUeqsOjVk

uosit^

) c

»iBa*

©UXUIO •

qsjcrapiTJo,

p-amqaBc AiGTAqai.̂ ,

sueqde

.Xxjaquso

uxxqxîwt̂ '

J91T8J[>

rpejci.

ITTFi Wfdgjj

j jr a p o o j^ «

sea* I

UOŜ OGp.

UOSjepUBTT.p̂-ejcq.