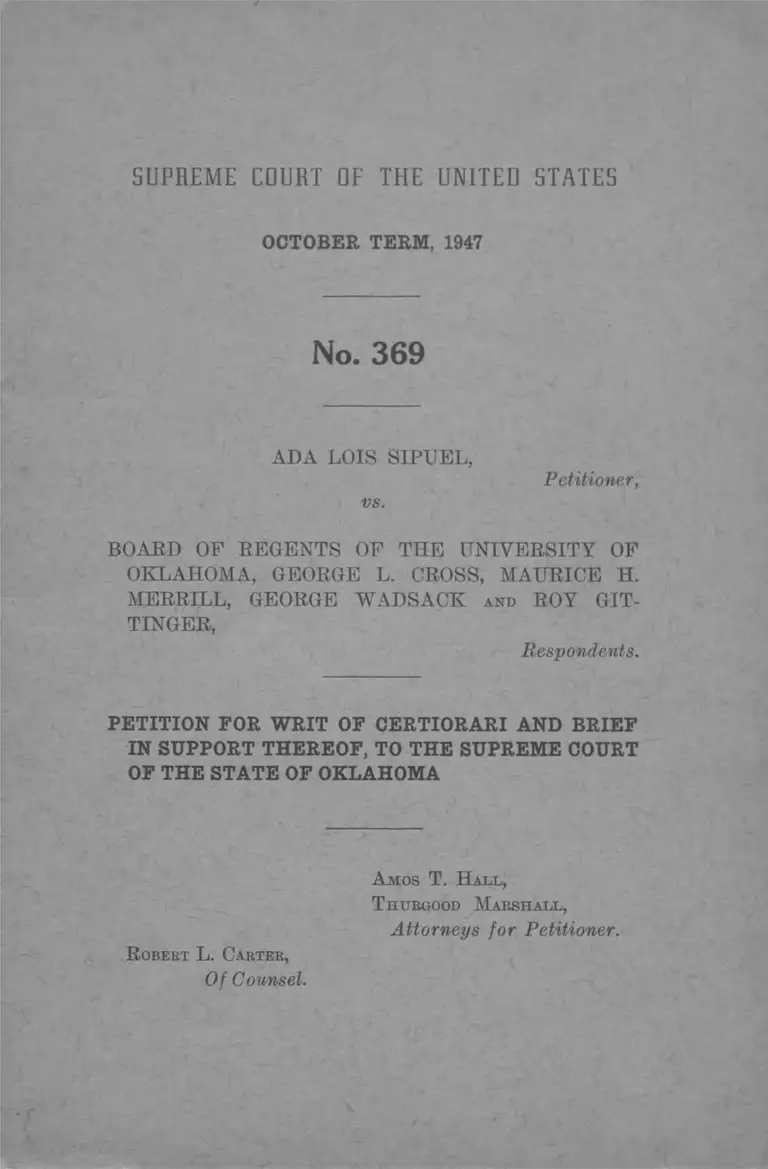

Sipuel v Board of Regents of UOK Petition for Writ of Certiorari

Public Court Documents

October 1, 1947

26 pages

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Sipuel v Board of Regents of UOK Petition for Writ of Certiorari, 1947. 38151c91-c49a-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/360a938b-aa95-4ed7-888e-fc2d9a03720c/sipuel-v-board-of-regents-of-uok-petition-for-writ-of-certiorari. Accessed February 22, 2026.

Copied!

SUPREME EDURT OF THE UNITED STATES

OCTOBER TERM, 1947

No. 369

ADA LOIS SIPUEL,

vs.

Petitioner,

BOARD OF REGENTS OF THE UNIVERSITY OF

OKLAHOMA, GEORGE L. CROSS, MAURICE H.

MERRILL, GEORGE WADSACK and ROY GIT-

TINGER,

Respondents.

PETITION FOR W RIT OF CERTIORARI AND BRIEF

IN SUPPORT THEREOF, TO THE SUPREME COURT

OF THE STATE OF OKLAHOMA

A m os T . H a l l ,

T hurgood M a r sh a ll ,

Attorneys for Petitioner.

R obert L. C arter ,

Of Counsel.

INDEX

S u b je c t I ndex

Page

Petition for writ of certiorari..................................... 1

Statement of the constitutional problem pre

sented .................................................................. 2

The salient fa c t s .................................................... 3

Question presented................................................. 5

Reason relied on for allowance of the writ.......... 6

Conclusion .............................................................. 6

Brief in support of petition ......................................... 7

Opinion of court below........................................... 7

Jurisdiction ............................................................ 7

Statement of the case............................................. 8

Error below relied upon here............................... 8

Argument ............................................................... 8

The decision of the Supreme Court of Okla

homa is inconsistent with and directly con

trary to the decision of this Court in

Gaines v. Canada ....................................... 8

Conclusion .............................................................. 19

C ases C ited

Canty v. Alabama, 309 U. S. 629................................. 6

Gaines v. Canada, 305 U. S. 337................................. 6

White v. Texas, 309 U. S. 631......................................... 6

S tatu tes C ited

Constitution of Oklahoma, Art. 13A ......................... 15,18

Federal Constitution, Fourteenth Amendment.......... 3

Judicial Code, Sec. 237(b) as amended....................... 1, 7

Missouri Revised Statutes— 1929, Section 9618 .... 22

Missouri Revised Stat. of 1939, Chapter 72, Art. 2,

Section 10349 (R, S. 1929, Sec. 9216, Rev. Stat.

Mo. 1939) .................................................................... 11,22

Oklahoma Stat. 1941, Title 70, Section 1451............. 14, 21

Oklahoma Stat. 1945, Title 70, Section 1451b............. 15, 21

—2585

SUPREME EDURT OF THE UNITED STATES

OCTOBER TERM, 1947

No. 369

ADA LOIS SIPUEL,

vs.

Petitioner,

BOARD OF REGENTS OF THE UNIVERSITY OF

OKLAHOMA, GEORGE L. CROSS, MAURICE H.

MERRILL, GEORGE WADSACK and ROY GIT-

TINGER,

Respondents.

PETITION FOR W RIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE

SUPREME COURT OF THE STATE OF OKLAHOMA

To the Honorable, the Chief Justice of the United States

and the Associate Justices of the Supreme Court of the

United States:

Petitioner, Ada Lois Sipuel, invokes the jurisdiction of

this Court under Section 237b of the Judicial Code (28

U. S. C. 344b) as amended February 13, 1925, and respect

fully prays that a writ of certiorari issue to review the judg

ment of the Supreme Court of the State of Oklahoma (R.

61), affirming the judgment of the District Court of Cleve

land County denying petitioner’s application for a writ of

lc

2

mandamus to compel respondents to admit her to the first

year class of the law school of the University of Oklahoma.

Statement of the Constitutional Problem Presented

Petitioner is a citizen and resident of the State of Okla

homa. She desires to study law and to prepare herself for

the practice of the legal profession. Pursuant to this aim

she applied for admission to the first year class of the

School of Law of the University of Oklahoma, a public in

stitution maintained and supported out of public funds and

the only public institution in the State offering facilities for

a legal education. Her qualifications for admission to this

institution are undenied, and it is admitted that petitioner,

except for the fact that she is a Negro, would have been ac

cepted as a first year student in the law school of the Uni

versity of Oklahoma, which is the only institution of its

kind petitioner is eligible to attend.

Petitioner applied to the District Court of Cleveland

County for a writ of mandamus against the Board of

Regents, George L. Cross, President, Maurice R. Merrill,

Dean of the Law School, Roy Gittinger, Dean of Admissions

and Roy Wadsack, Registrar to compel her admission to the

first year class of the school of law on the same terms and

conditions afforded white applicants seeking to matriculate

therein (R. 2). The writ was denied (R. 21), and on appeal

this judgment was affirmed by the Supreme Court of the

State of Oklahoma on April 29, 1947 (R. 35). Petitioner

duly entered a motion for rehearing (R. 54), which was

denied on June 24, 1947 (R. 61). Whereupon petitioner

now seeks from this Court a review and reversal of the

judgment below.

The action of respondents in refusing to admit petitioner

to the school of law was predicated on the ground (1) that

such admission was contrary to the constitution, laws and

3

public policy of the State; (2) that scholarship aid was

offered by the State to Negroes to study law outside the

State, and; (3) that no demand had been made on the

Board of Regents of Higher Education to provide such legal

training at Langston University, the State institution af

fording college and agricultural training to Negroes in the

State.

In this Court petitioner reasserts her claim that the re

fusal to admit her to the University of Oklahoma solely

because of race and color amounts to a denial of the equal

protection of the laws guaranteed under the Fourteenth

Amendment to the Federal Constitution in that the State

is affording legal facilities for whites while denying such

facilities to Negroes.

The Salient Facts

The facts in issue are uncontroverted and have been

agreed to by both petitioner and respondents (R. 22-25).

The following are the stipulated facts:

The petitioner is a resident and citizen of the United

States and of the State of Oklahoma, County of Grady and

City of Chicakasha, and desires to study law in the School

of Law in the University of Oklahoma for the purpose of

preparing herself to practice law in the State of Oklahoma

(R. 22).

The School of Law of the University of Oklahoma is the

only law school in the State maintained by the State and

under its control (R. 22).

The Board of Regents of the University of Oklahoma is

an administrative agency of the State and exercises over-all

authority with reference to the regulation of instruction and

admission of students in the University of Oklahoma. The

University is a part of the educational system of the State

and is maintained by appropriations from public funds

4

raised by taxation from the citizens and taxpayers of the

State of Oklahoma (R. 22-23).

The School of Law of the Oklahoma University specializes

in law and procedure which regulates the government and

courts of justice in Oklahoma, and there is no other law

•school maintained by public funds of the State where the

petitioner can study Oklahoma law and procedure to the

same extent and on an equal level of scholarship and in

tensity as in the School of Law of the University of Okla

homa. The petitioner will be placed at a distinct disad

vantage at the bar of Oklahoma and in the public service

of the aforesaid State with respect to persons who have had

the benefit of the unique preparation in Oklahoma law and

procedure offered at the School of Law of the University

of Oklahoma, unless she is permitted to attend the afore

said institution (R. 23).

The petitioner has completed the full college course at

Langston University, a college maintained and operated by

the State of Oklahoma for the higher education of its Negro

citizens (R. 23).

The petitioner made due and timely application for ad

mission to the first year class of the School of Law of the

University of Oklahoma on January 14, 1946, for the semes

ter beginning January 15, 1946, and then possessed and still

possesses all the scholastic and moral qualifications required

for such admission (R. 23).

On January 14, 1946, when petitioner applied for admis

sion to the said School of Law she complied with all of the

rules and regulations entitling her to admission by filing

with the proper officials of the University an official tran

script of her scholastic record. The transcript was duly

examined and inspected by the President, Dean of Admis

sion and Registrar of the University (all respondents

herein) and was found to be an official transcript entitling

5

her to admission to the School of Law of the said University

(R. 23).

Under the public policy of the State of Oklahoma, as

evidenced by the constitutional and statutory provisions

referred to in the answer of respondents herein, petitioner

was denied admission to the School of Law of the University

of Oklahoma solely because of her race and color (R. 23-24).

The petitioner, at the time she applied for admission to

the said school of the University of Oklahoma, was and is

now ready and willing to pay all of the lawful charges, fees

and tuitions required by the rules and regulations of the said

University (R. 24).

Petitioner has not applied to the Board of Regents of

Higher Education to prescribe a school of law similar to

the School of Law of the University of Oklahoma as a part

of the standards of higher education of Langston University

and as one of the courses of study thereof (R. 24).

It was further stipulated between the parties that after

the filing of this case, the Board of Regents of Higher

Education had notice that this case was pending and met and

considered the questions involved herein and had no un

allocated funds on hand or under its control at the time

with which to open up and operate a law school and has

since made no allocation for such a purpose (R. 24-25).

Question Presented

Does the Constitution of the United States Prohibit the

Exclusion of a Qualified Negro Applicant Solely Because of

Race from Attending the Only Law School Maintained By

a State?

2c

6

Reason Relied On For Allowance of the Writ

The Decision of the Supreme Court of Oklahoma Is In

consistent With and Directly Contrary to the Decision of

This Court in Gaines v. Canada.1

The question presented in this case is identical to that

presented to this Court in Gaines v. Canada. The facts

and the Oklahoma Statute governing this case are similar to

those involved in the Gaines case. Had the Gaines case

been followed, judgment in petitioner’s favor would have

been rendered in the court below. In other cases where

this Court has been requested to review decisions of State

courts denying fundamental civil rights and in direct con

flict with previous decisions of this Court certiorari has

been granted and the judgment reversed without hearing.2

Conclusion

W h erefore , it is respectfully submitted that this petition

for writ of certiorari to review the judgment of the Supreme

Court of the State of Oklahoma should be granted and the

judgment of the Supreme Court of Oklahoma reversed.

A mos T. H a l l ,

T hurgood M a r sh a ll ,

Attorneys for Petitioner.

R obert L. Carter ,

Of Counsel.

1 305 U. S. 337.

2 Canty v. Alabama, 309 U. S. 629; White V. Texas, 309 U. S. 631

rehearing denied 310 U. S. 530.

SUPREME EOURT OF THE UNITED STATES

OCTOBER TERM, 1947

No. 369

ADA LOIS SIPUEL,

vs.

Petitioner,

BOARD OF REGENTS OF THE UNIVERSITY OF

OKLAHOMA, GEORGE L. CROSS, MAURICE H.

MERRILL, GEORGE WADSACK and ROY GIT-

TINGER,

Respondents.

BRIEF IN SUPPORT OF PETITION FOR W RIT OF

CERTIORARI TO THE SUPREME COURT OF THE

STATE OF OKLAHOMA

Opinion of Court Below

The opinion of the Supreme Court of Oklahoma appears

in the record filed in this cause (R. 35-51).

J urisdiction

Jurisdiction of this Court is invoked under Section 237b

of the Judicial Code (28 U. S. C. 344b) as amended Febru

ary 13, 1925.

The Supreme Court of Oklahoma issued its judgment in

this case on April 29, 1947 (R. 51). Petition for rehearing

8

was appropriately filed and was denied on June 24, 1947

(R. 61).

Statement of the Case

The statement of the case and a statement of the salient

facts from the record are fully set forth in the accompany

ing petition for certiorari. Any necessary elaboration on

the finding of the points involved will be made in the course

of the argument.

Error Below Relied Upon Here

The Decision of the Supreme Court of Oklahoma Is In

consistent With and Directly Contrary to the Decision of

This Court in Gaines v. Canada.

Argument

The Decision of the Supreme Court of Oklahoma Is In

consistent With atid Directly Contrary to the Decision of

This Court in Gaines v. Canada.

There is no dispute as to the facts in this case. Peti

tioner’s qualifications for a legal education are admitted.

The only law school maintained by the State of Oklahoma

is the law school of the University of Oklahoma. Petition

er’s application to said school was refused because of her

race and color and she sought a writ of mandamus to com

pel her admission to the law school of the University of

Oklahoma (R. 2). The trial court refused to issue the

writ (R. 21) and this judgment was affirmed by the Supreme

Court of Oklahoma.

Respondents defended their refusal to admit petitioner

on the ground that the laws of Oklahoma prohibited Negroes

from attending schools established for white pupils. Peti

tioner relied on the decision of this Court in Gaines v.

Canada et al.,3 including the principle that: “ The admissi

3 305 U. S. 337.

9

bility of laws separating the races in the enjoyment of

privileges afforded by the State rests wholly upon the

quality of the privileges which the laws give to the separated

groups within the State.” 4

However, the court below in affirming the judgment

denying the writ relied upon the constitution and laws of the

State requiring the segregation of the races for educational

purposes:

“ Petitioner Ada Lois Sipuel, a Negro, sought admis

sion to the law school of the State University at Nor

man. Though she presented sufficient scholastic at

tainment and was of good character, the authorities of

the University denied her enrollment. They could not

have done otherwise for separate education has always

been the policy of this state by vote of citizens of all

races. See Constitution, Art. 13, Sec. 3, and numer

ous statutory provisions as to schools” (R. 37).

* * * # # # #

“ Petitioner contends that since no law school is

maintained for Negroes, she is entitled to enter the

law school of the University, or if she is denied that,

she will be discriminated against on account of race

contrary to the 14th Amendment to the United States

Constitution. This is specious reasoning, for of course

if any person, white or Negro, is unlawfully discrimi

nated against on account of race, the Federal Constitu

tion is thereby violated. But in this claim for Univer

sity admission petitioner takes no account, or does not

take fair account, of the separate school policy of the

State as above set out” (R. 38).

This argument postulates an inherently fallacious

premise which, if true, would render the equal protection of

the laws guaranteed under the Fourteenth Amendment a

meaningless and empty provision. This argument means

4 Id at p. 349.

10

in effect that where there exists a policy of racial separa

tion ; and a state affords to whites a public facility unavail

able to Negroes, it can delay, defeat or deny a claim of

infringement of constitutional right by pleading the validity

of its segregation laws. The law is clear that the admissi

bility of segregation statutes is contingent upon proof that

there is available to Negroes public facilities within the State

equal to those afforded whites within the State.

Hence the segregational statutes or policy of Oklahoma

could not validly be before the courts without there being

first a showing that petitioner could have obtained within

the State a legal education equal to that offered at the

University of Oklahoma. This unquestionably is untrue

since admittedly the University of Oklahoma is the only

State institution offering instruction in law (R. 22). With

the establishment of this fact along with petitioner’s quali

fications for admission to the school of law, a primie facie

case for issuance of the writ was made and respondents

have advanced nothing to justify the court in refusing to

render judgment in petitioner’s favor.

The similarity between this case and the Gaines case is,

of course, apparent upon even a cursory examination.

Upon close inspection, however, one finds that the two

cases are all but identical both as to law and fact.

In the Gaines case, as here, application was made for

admission to the only law school maintained by the State.

The application was referred by the University of Mis

souri to the President of Lincoln University, the State col

lege for Negroes. The latter officer directed Gaines’ atten

tion to the Missouri statute providing out of state scholar

ship aid to Negroes for educational advantages not offered

at Lincoln University. Whereupon Gaines instituted suit

against the officers of the state law school, as was done in

this case, to compel his admission to that institution. The

11

record clearly shows in the Gaines case that Gaines, like

petitioner herein, at no time made application either to the

State college for Negroes, its governing board or its officers

for a legal education at Lincoln University or for out of

State scholarship aid.

“ Q. Now you never at any time made an application

to Lincoln University or its Curators or its officers or

any representative for any of the rights, whatever,

given you by the 1921 statute, namely, either to receive

a legal education at a school to be established in Lincoln

University or, pending that, to receive a legal education

in a school of law in a state university in an adjacent

state to Missouri, and Missouri paying that tuition,

—you never made application for any of those rights,

did you? A. No, sir.” 5

Missouri had a provision as does Oklahoma making it

unlawful for Negroes and whites to attend the same school.

Chapter 72, Art. 2, Section 10349 of Rev. Stat. of Mo. 1939

provides as follows:

“ Separate free schools shall be established for the

education of children of African descent ; and it shall

hereinafter be unlawful for any colored child to attend

any white school, or for any white child to attend any

colored school.” (R. S. 1929, Sec. 9216, Rev. Stat. Mo.

1939).

In refusing to follow the Gaines case, the Supreme Court

of Oklahoma sought to distinguish the two cases by assum

ing facts not present in the record of this case and by assum

ing facts in the Gaines case directly contrary to the record

and decision in that case.

Although the Supreme Court of Oklahoma recognized

that: “ There is no controversy as to the facts presented.

Trial was held upon stipulation * * *” (R. 38), the Court

5 Transcript of Record Gaines v. Canada et al, No. 57, October

Term, 1938, p. 85).

12

relied upon the alleged administration of an out-of-state

scholarship fund which does not appear at all in the stipu

lation. Oklahoma statutes provide for such a fund, hut

there is no evidence as to whether such fund has ever been

used or, if so, the terms under which it has been admin

istered.

The Oklahoma Court in seeking to distinguish the Gaines

case uses only one alleged difference as to fact:

“ * * * Thus in Missouri there was application for

and denial of that which could have been lawfully fur

nished, that is, law education in a separate school, while

in this case the only demand or request was for that

which could not be lawfully granted, that was education

of petitioner, a Negro, in a white school” (R. 45).

In her Petition for Rehearing in the Oklahoma Supreme

Court petitioner pointed out that the Court’s assumption

of facts in the Gaines case was in error (R. 56). It should

also be noted that the reported opinion of the Supreme

Court of Missouri in the Gaines case stated: “ He at no time

applied to the management of the Lincoln University fox-

legal training.” 6

It should be pointed out that in the agreed Statement of

Facts it is admitted :

“ That after the filing of this cause the Board of

Regents of Higher Education, having knowledge

thereof, met and considered the questions involved

therein; that it had no unallocated funds in its hands

or under its control at that time with which to open

up and operate a law school and has since made no allo

cation for that purpose; that in order to open up and

operate a law school for Negroes in this state, it will

be necessai-y for the board to either withdraw existing

allocations, procure moneys, if the law permits, from

the Governor’s contingent fund, or make an application

6 113 S. W. (2d) 783, at p. 789.

13

to the next Oklahoma legislature for funds sufficient to

not only support the present institutions of higher edu

cation but to open up and operate said law school; and

that the Board has never included in the budget which

it submits to the Legislature an item covering the open

ing up and operation of a law school in the State for

Negroes and has never been requested to do so.”

Much emphasis is placed in the opinion of the Court below

on the fact that it is a crime under Oklahoma law to admit

a Negro into a white school and vice versa. It is evident

from the Missouri statute cited supra that when Gaines

applied for admission to the University of Missouri that

it was illegal under Missouri law for a Negro to he admitted

to a white school.

In the face of the unquestioned duty of the State under

the constitution to provide equal educational facilities as

between Negroes and whites, the illegality involved in any

breach of the State policy of educational segregation was

not considered worthy of even passing mention by this

Court in disposing of the constitutional question before it.

Petitioner contends that this phase of the opinion of the

Court below is without merit or validity and is met by this

Court’s rule discussed supra that the admissibility of segre

gation statutes rests wholly upon a showing of equality of

the facilities.

An examination of the statute governing the State col

lege for Negroes in force in Missouri at the time of the

Gaines decision and the statute now in force in Oklahoma

governing Langston University completes the likeness be

tween the two cases. Argument was made when the Gaines

case was before this Court that Gaines, rather than having

sought admission to the University of Missouri, should

have applied to the Board of Curators of Lincoln Univer

sity for the establishment of a law school at Lincoln Uni

versity. This Court found such action unnecessary since

14

there did not exist any mandatory duty on the Board of

Curators of Lincoln University to establish a law school.

The statute setting forth the duties of the Board are set

forth below and were construed by the Missouri Supreme

Court as placing no mandatory duty upon that Board.

Section 9618, Missouri Revised Statutes 1929 provided as

follows:

“ Board of curators authorized to reorganize. The

board of curators of the Lincoln University shall be

authorized and required to reorganize said institution

so that it shall afford to the Negro people of the state

opportunity for training up to the standard furnished

at the state university of Missouri whenever necessary

and practicable in their opinion. To this end the board

of curators shall be authorized to purchase necessary

additional land, erect necessary additional buildings,

to provide necessary additional equipment, and to lo

cate, in the county of Cole the respective units of the

university where, in their opinion, the various schools

will most effectively promote the purposes of this

article. Laws 1921, p. 86, Sec. 3.”

In Oklahoma, Langston University is governed by the

Board of Regents for Oklahoma, Agricultural and Mechani

cal College. Title 70, Section 1451 Okla. Stat. 1941 states:

“ Location and purpose— The Colored Agricultural

and Normal University of the State of Oklahoma is

hereby located and established at Langston in Logan

County, Oklahoma. The exclusive purpose of such

school shall be the instruction of both male and female

colored persons in the art of teaching, and the various

branches which pertain to a common school education,

and in such higher education as may be deemed advis

able by such board and in the fundamental laws of this

State and of the United States, and in the rights and

duties of citizens, and in the agricultural, mechanical

and industrial arts.”

15

This provision was amended in 1945 and now provides as

follows:

“ Sec. 1451b. Board of Regents—Management and

control—President and personnel.—The operation,

management and control of Langston University, at

Langston, Okla. is hereby vested in the Board of Re

gents for Okla. Agr. &■ Mech. Colleges created by sec

tion 31a, Article 6, Okla. Constitution, adopted July 11,

1944. Said Board of Regents is hereby authorized to

elect a president of said University and employ neces

sary instructors, professors and other personnel, and

fix salaries thereof, and do any and all things necessary

to make the University effective as an educational in

stitution for Negroes of the State.”

This Board is under a duty to “ do any and all things

necessary to make the University effective as an educational

institution for Negroes of the State.” The Oklahoma

State Regents for Higher Education were created pursuant

to a constitutional amendment in 1941 under Art. 13A with

overall authority over the entire educational system of the

State as set out in the constitutional provisions.

“ There is hereby established the Oklahoma State Re

gents for Higher Education, consisting of nine (9)

members, whose qualifications may be prescribed by

law. The Bd. shall consist of nine (9) members ap

pointed by the Governor, confirmed by the Senate, and

who shall be removable only for cause, as provided by

law for the removal of officers not subject to impeach

ment. Upon the taking effect of this Art. the Governor

shall appoint the said Regents for terms of office as

follows: one for a term of one year, one for a term of

two years, one for a term of three years, one for a term

of four years, one for a term of five years, one for a

term of six years, one for a term of seven yenrs, one

for a term of eight years, and one for a term of nine

years. Any appointment to fill a vacancy shall be for

the balance of the term only except as above designated,

16

the term of office of said Regents shall be nine years

or until their successors are appointed and qualified.

“ The Regents shall constitute a co-ordinating board

of control for all state institutions described in Section

1 hereof with the following specific powers: (1) It shall

prescribe standards of higher education applicable to

each institution; (2) it shall determine the functions

and courses of study in each institution to conform to

the standards prescribed; (3) it shall grant degrees

and other forms of academic recognition for completion

of the prescribed courses in all such institutions; (4) it

shall recommend to the State Legislature the budget

allocations to each institution, and; (5) it shall have

the power to recommend to the Legislature proposed

fees for all such institutions, and any such fees shall be

effective only within the limits prescribed by the Legis

lature.”

The Court below found from these provisions that this

Board has a mandatory duty to establish a law school at

Langston University upon demand. This conclusion is

reached by a strange construction of the law. The Court

finds the mandate not in the language of the constitutional

provision itself which is unambiguous and specific but in

the segregational policy of the State.

“ The Constitution of the United States is the Su

preme Law of the land. It' effectively prohibits dis

crimination against any race and all state officials are

sworn to support, obey and defend it. When we realize

that and consider the provisions of our State Consti

tution and Statutes as to education, we are convinced

that it is the mandatory duty of the State Regents for

Higher Education to provide equal educational facili

ties for the races to the full extent that the same is

necessary for the patronage thereof. That board has

full power, and as we construe the law, the mandatory

duty to provide a separate law school for Negroes upon

demand or substantial notice as to patronage therefor.”

(R. 50).

17

By no stretch of the imagination can this provision be

said to create any mandatory duty except as such a con

struction is used in an attempt to defeat petitioner’s con

stitutional right. The court admits the Board is under a

duty to act without formal demand upon definite informa

tion that a Negro was available for the desired legal train

ing.

“ The state Begents for Higher Education has

undoubted authority to institute a law school for

Negroes at Langston. It would be the duty of that

board to so act, not only upon formal demand, but on

any definite information that a member of that race

was available for such instruction and desired the same.

The fact that petitioner has made no demand or com

plaint to that board, and has not even informed that

board as to her desires, so far as this record shows,

may lend some weight to the suggestion that petitioner

is not available for and does not desire such instruction

in a legal separate school” (R. 42).

The court also, while recognizing that petitioner’s right

to a legal education is an individual right which cannot be

affected by the actions of members of her race in demanding

or failing to demand a legal education, attempts to link

petitioner’s right with demands made or needs manifested

by other Negroes for legal training before requiring the

State to afford redress to petitioner for failure to provide

her with an opportunity for training in law equal to that

afforded whites.

“ As we view the matter the state itself could not

place complete reliance upon the lack of a formal de

mand by petitioner. We do not doubt it would be the

duty of the state, without any formal demand, to pro

vide equal educational facilities for the races, to the

fullest extent indicated by any desired patronage,

whether by formal demand or otherwise. But it does

seem that before the state could be accused of dis

18

crimination for failure to institute a certain course of

study for Negroes, it should be shown there was some

ready patronage therefor, or some one of the race

desirous of such instruction. This might be shown by

a formal demand, or by some character of notice, or by

a condition so prevalent as to charge the proper officials

with notice thereof without any demand. Nothing of

such kind is here shown. It is stated in oral argument

by attorneys for petitioner that so far as this record

shows petitioner is the first member of her race to seek

or desire education in the law within the state, and

upon examination we observe the record is blank on

the point. That is not important as being controlling

of petitioner’s individual rights, but it should be con

sidered in deciding whether there is any actual or

intentional discrimination against petitioner or her

race” (R. 41).

This is sophistical and circ-itous reasoning. There is

clearly less basis for construing section 13A of Oklahoma

Constitution as creating a mandatory duty in the Board

of Regents of Higher Education to establish a law school

at Langston than there was in finding such a compulsion on

the Board of Curators of Lincoln University to establish

a law school there. The opinion of the court below gives the

definite impression that the court below recognized that

petitioner’s rights were governed by the decision in the

Gaines case. However, it was not prepared to accept the

results which adherence to that decision would entail.

The Oklahoma Court’s third and final effort to distinguish

the Gaines case was:

“ * * * Furthermore, in Missouri the out of state

education was restricted to states adjacent to Missouri,

while, as heretofore pointed out, such out of state educa

tion provided for Oklahoma Negroes is not so restricted,

the Negro pupil here has complete freedom of choice,

and it is a matter of common knowledge that Oklahoma

Negro students have attended schools in more than

19

twenty states extending from New York to California,

and including the Nation’s Capitol” (R. 45).

This line of reasoning completely ignores the agreed

stipulation of fact:

“ . . . that there is no other law school maintained

by the public funds of the State where the plaintiff can

study Oklahoma law and procedure to the same extent

and on an equal level of scholarship and intensity as in

the School of Law of the University of Oklahoma; that

the plaintiff will be placed at a distinct disadvantage at

the bar of Oklahoma and in the public service of the

aforesaid State with persons who have had the benefit

of the unique pi'eparation in Oklahoma law and pro

cedure offered to white qualified applicants in the School

of Law of the University of Oklahoma, unless she is

permitted to attend the School of Law of the University

of Oklahoma” (R. 23).

There is no material difference between the Gaines case

and the instant case. The reasons advanced by the Okla

homa Court for not following the Gaines case are clearly

without merit. In the meantime the petitioner has already

been deprived of at least a year’s legal training enjoyed by

white students of similar qualifications who applied for ad

mission at approximately the same time. The sole reason

for this discrimination is race and color.

Conclusion

Wherefore, it is respectfully submitted that this petition

for writ of certiorari to review the judgment of the Supreme

Court of the State of Oklahoma should be granted and the

judgment of the Supreme Court of Oklahoma reversed.

A mos T . H alt,,

T hurgood M a r s h a ll ,

Attorneys for Petitioner.

R obert L. Carter ,

Of Counsel.

20

APPENDIX

Oklahoma Constitution— 1941

Article 13A. Section 2.—Oklahoma State Regents for

Higher Education — Establishment — Membership — Ap

pointments—Terms—Vacancy—Powers as Co-ordinating

Board of Control.

There is hereby established the Oklahoma State Regents

for Higher Education, consisting of nine (9) members,

whose qualifications may be prescribed by law. The Board

shall consist of nine (9) members appointed by the Governor,

confirmed by the Senate, and who shall he removable only

for cause, as provided by law for the removal of officers not

subject to impeachment. Upon the taking effect of this

Article, the Governor shall appoint the said Regents for

terms of office as follows: one for a term of one year, one

for a term of two years, one for a term of three years, one

for a term of four years, one for a term of five years, one

for a term of six years, one for a term of seven years, one

for a term of eight years, and one for a term of nine years.

Any appointment to fill a vacancy shall be for the balance

of the term only. Except as above designated, the term of

office of said Regents shall be nine years or until their suc

cessors are appointed and qualified.

The Regents shall constitute a co-ordinating board of con

trol for all state institutions described in Section 1 hereof,

with the following specific powers: (1) it shall prescribe

standards of higher education applicable to each institution;

(2) it shall determine the functions and courses of study in

each institution to conform to the standards prescribed;

(3) it shall grant degrees and other forms of academic

recognition for completion of the prescribed courses in all

such institutions; (4) it shall recommend to the State Legis

lature the budget allocations to each institution, and; (5) it

shall have the power to recommend to the Legislature

proposed fees for all such institutions, and any such fees

shall be effective only within the limits prescribed by the

Legislature.

21

Section 1451—Tit. 70—Okla. Stat. 1941

Location and purpose—The Colored Agricultural and

Normal University of the State of Oklahoma is hereby

located and established at Langston in Logan County, Okla

homa. The exclusive purpose of such school shall be the

instruction of both male and female colored persons in the

art of teaching, and the various branches which pertain to

a common school education, and in such higher education

as may be deemed advisable by such board and in the funda

mental laws of this State and of the United States, and in

the rights and duties of citizens, and in the agricultural

mechanical and industrial arts.

Section 1451b—Tit. 70—Okla. Stat. 1945

Board of Kegents—Management and control—President

and personnel—The operation, management and control of

Langston University, at Langston, Oklahoma, is hereby

vested in the Board of Regents for Oklahoma Agricultural

& Mechanical Colleges created by Section 31a, Article 6,

Oklahoma Constitution, adopted July 11, 1944. Said Board

of Regents is hereby authorized to elect a President of

said University and employ necessary instructors, profes

sors and other personnel, and fix salaries thereof, and do

any and all things necessary to make the University effec

tive as an educational institution for Negroes of the State.

Section 455

It shall be unlawful for any person, corporation or asso

ciation of persons, to maintain or operate any college, school

or institution of this state where persons of both white and

colored races are received as pupils for instruction, and

any person or corporation who shall operate or maintain

any such college, school or institution in violation hereof,

shall be deemed guilty of a misdemeanor, and upon convic

tion thereof shall be fined not less than one hundred dollars

nor more than five hundred dollars, and each day such

school, college, or institution shall be open and maintained

shall be deemed a separate offense.

22

Section 456

Any instructor who shall teach in any school, college or

institution where members of the white race and colored

race are received and enrolled as pupils for instruction,

shall be deemed guilty of a misdemeanor, and upon convic

tion thereof shall be fined in any sum not less than ten dol

lars nor more than fifty dollars for each offense, and each

day any instructor shall continue to teach in any such col

lege, school or institution, shall be considered a separate

offense.

Section 457

It shall be unlawful for any white person to attend any

school, college or institution, where colored persons are

received as pupils for instruction, and any one so offending

shall be fined not less than five dollars, nor more than twenty

dollars for each offense, and each day such person so

offends, as herein provided, shall be deemed a distinct and

separate offense; provided, that nothing in this article shall

be construed as to prevent any private school, college or

institution of learning from maintaining a separate or dis

tinct branch thereof in a different locality.

Chapter 72—Article 2, Section 10349—Revised Statute

Missouri—1939:

Separate schools for white and colored children—iSepa-

rate free schools shall be established for the education of

children of African descent; and it shall hereinafter be

unlawful for any colored child to attend any Avhite school,

or for any white child to attend any colored school (R. S.

1929, Sec. 9216, Rev. Stat. Mo. 1939).

Section 9618, Mo. Rev. Stat. 1929, is as follows:

Sec. 9618. Board of curators authorized to reorganize—

The board of curators of the Lincoln university shall be

authorized and required to reorganize said institution so

that it shall afford to the Negro people of the state oppor

tunity for training up to the standard furnished at the state

university of Missouri whenever necessary and practicable

23

in their opinion. To this end the board of curators shall

be authorized to purchase necessary additional land, erect

necessary additional buildings, to provide necessary addi

tional equipment, and to locate, in the county of Cole the

respective units of the university where, in their opinion,

the various schools will most effectively promote the pur

poses of this article. Laws 1921, p. 86, Sec. 3.

(2585)