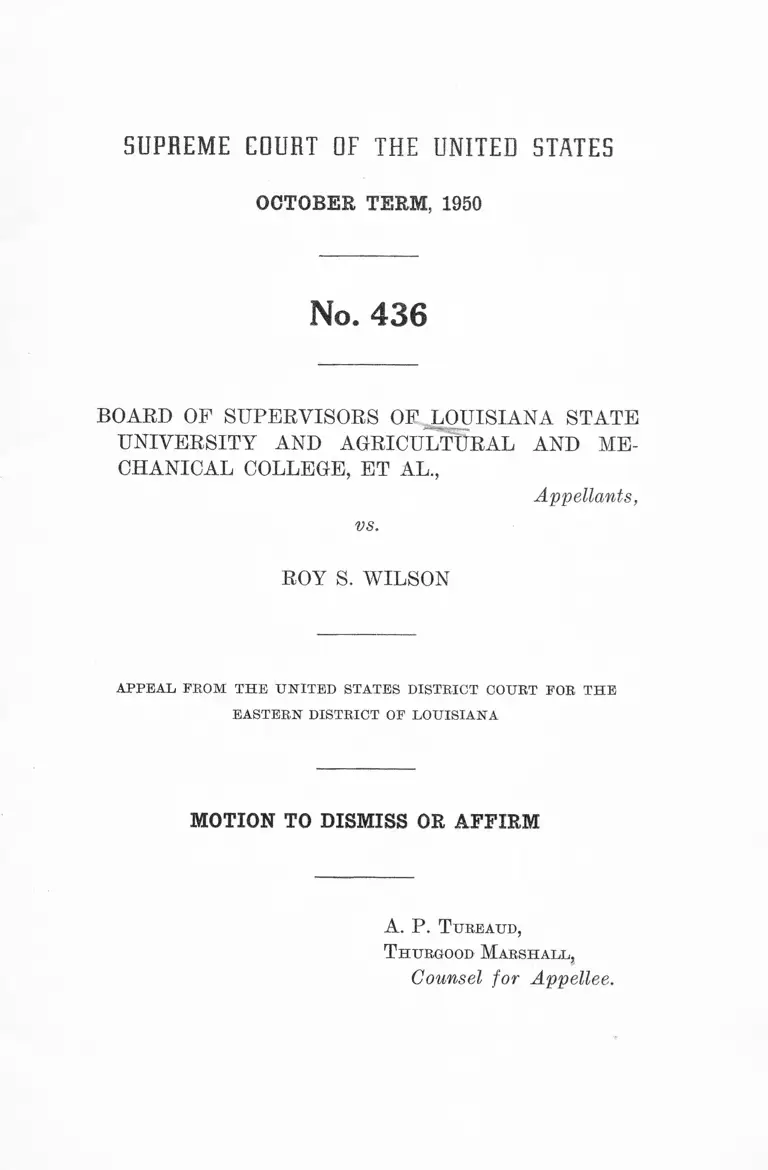

Board of Supervisors of Louisiana State University & Agricultural & Mechanical College v Wilson Motion to Dismiss or Affirm

Public Court Documents

November 13, 1950

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Board of Supervisors of Louisiana State University & Agricultural & Mechanical College v Wilson Motion to Dismiss or Affirm, 1950. 41f643e0-bb9a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/366b6772-cc35-4f96-a839-b52f1afd9e1d/board-of-supervisors-of-louisiana-state-university-agricultural-mechanical-college-v-wilson-motion-to-dismiss-or-affirm. Accessed February 17, 2026.

Copied!

SU P RE M E COURT OF THE UNITEU STATES

OCTOBER TERM, 1950

No. 436

BOARD OF SUPERVISORS OF LOUISIANA STATE

UNIVERSITY AND AGRICULTURAL AND ME

CHANICAL COLLEGE, ET AL.,

Appellants,

vs.

ROY S. WILSON

A PPE A L FBOM T H E U N IT E D STATES D ISTRICT COURT EOR T H E

EASTERN DISTRICT OF LO U ISIAN A

MOTION TO DISMISS OR AFFIRM

A. P. T u r e a u d ,

T h u r g o o d M a r s h a l l ,

Counsel for Appellee.

INDEX

Subject I ndex

Page

Motion to dismiss or affirm........................................... 1

Statement ................................................................ 2

Order involved........................................................ 3

Argument ................................................................ 4

Conclusion................................................................ 10

T abus of Cases Cited

Borges v. Loftis, 87 F. 2d 734, 301 U. S. 687, 57 S.

Ct. 789', 81 L. Ed. 1344, 301 II. S. 714, 57 S. Ct. 928,

81 L. ed. 1365................................................................ 6

McLaurin v. Oklahoma, 70 Sup. Ct. 851....................... 4

Oklahoma Natural Gas Co. v. Russel, 261II. S. 290.. 6

Phillips v. United States, 312 U. S. 246, 61 S. Ct. 480,

85 L. ed. 800 ................................................................ 6

Railroad Commission of Texas v. Pullman Company,

312 U. S. 496, 61 S. Ct. 643, 85 L. ed. 971................. 6

Sterling v. Constantin, 287 IT. S. 378........................... 8

Statutes Cited

Louisiana General Statutes (Dart), Section 2503.3. . 5

Oklahoma Statutes, Title 70, Section 1242................... 4

United States Code, Title 28, Section 2281................. 4, 9

— 1590

SU P R E M E COURT OF THE UNITED STATES

OCTOBER TERM, 1950

No. 436

BOARD OF SUPERVISORS OF LOUISIANA STATE

UNIVERSITY AND AGRICULTURAL AND ME

CHANICAL COLLEGE, ET AL.,

vs.

Appellants,

ROY S. WILSON

A PPE A L FROM T H E U N IT E D STATES D ISTRICT COURT FOR T H E

EASTERN DISTRICT OF LO U ISIAN A

MOTIONS OF APPELLEE TO DISMISS OR AFFIRM

These motions are filed by the appellee pursuant to para

graph 3 of Rule 12 of the Rules of the Supreme Court, in

response to the statement as to jurisdiction and other pa

pers filed by the appellants, which urge the Supreme Court

to review on appeal the judgment entered by the United

States District Court for the Eastern District of Louisiana.

2

Statement

This case was filed in the United States District Court

for the Eastern District of Louisiana on September 13,

1950. The appellee on his own behalf and on behalf of

other Negro citizens of Louisiana similarly situated sought

a preliminary and a final injunction against appellants who

are state officers being the Board of Supervisors of Loui

siana State University and administrative officers of said

institution to restrain them from enforcing an order which

prevented the appellee and other qualified Negroes from

attending the law school of Louisiana State University.

A statutory court of three judges was convened and ap

pellee’s application for a temporary injunction was heard

on September 29, 1950 upon the pleadings, depositions and

affidavits. Appellant’s motion to dismiss the action as a

class action was heard at the same time.

On October 7, 1950 the District Court filed its findings of

fact and conclusions of law. Final judgment was entered on

October 30, 1950 granting the preliminary injunction. Or

der allowing an appeal to the Supreme Court was signed

the same day.

There is no dispute as to the facts in this case. The

appellee is admittedly qualified for admission to the law

school of Louisiana State University. He applied for ad

mission during the period other students were applying

for the 1950-51 school year and his application was refused.

The State of Louisiana maintains separate schools for

its Negro and white students. The State maintains an

institution known as the Louisiana State University and

Agricultural and Mechanical College which has been in

existence since 1859. It also maintains Southern University

for Negro students.

Louisiana State University has maintained a Department

of Law since 1906. Southern University has had a law

3

school since 1947. A comparison of the two law schools ap

pears in the depositions of the Deans of the respective

schools.

It is conceded that there is no statute or provision of the

Constitution of the State of Louisiana which by its terms

denies to Negroes admission to Louisiana. State University.

However, it is the policy of the appellant Board of Super

visors of said institution to deny Negroes admission solely

because of their race and color.

Louisiana State University has twelve colleges and sev

eral divisions and is accredited by every recognized accredit

ing agency. It accepts all qualified students except Negroes.

Except for the law school, Southern University is a college

and not a university.

The District Court found that “ the Law School of South

ern University does not afford to plaintiff educational ad

vantages equal or substantially equal to those that he would

receive if admitted to the Department of Law of the

Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechani

cal College.”

Order Involved

It is conceded that there is no statute or provision of the

Constitution of the State of Louisiana which by its term

denies to Negroes admission to Louisiana State University.

Appellee and others in the class on whose behalf he sues

were denied admission to the law school of Louisiana State

University because of the order of the Board of Supervisors

of said institution which provides :

“ Be It R esolved that pursuant to the laws of Louisi

ana and the policies of this Board the administrative

officers are hereby directed to deny admission to the fol

lowing applicants: Nephus Jefferson, Dan Columbus

Simon, Willie Cleveland Patterson, Charles Edward

Coney, Joseph H. Miller, Jr., Roy Samuel Wilson, Lloyd

E. Milburn, Lawrence Alvin Smith, Jr., James Lee

4

Perkins, Edison George Hogan, Harry A. Wilson, An

derson Williams. ’ ’

Argument

The Statement as to Jurisdiction filed by the appellants

relies upon the Assignment of Errors filed therewith and

these motions are addressed to both the Statement of Juris

diction and the Assignment of Errors.

I

In paragraph 1 of their assignment of errors, appellants

allege that the District Court erred in holding that as a

matter of law it was vested with jurisdiction of appellee’s

application for an interlocutory injunction against appel

lants’ order which denied appellee’s admission to Louisiana

State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College

in the terms set forth. This allegation is without merit for

the following reasons:

(a) Title 28 U.S.C., section 2281 provides that a three-

judge court shall hear all cases wherein plaintiff seeks to

enjoin “ the enforcement or execution of an order made by

an administrative board or commission acting under State

statutes ’ ’ on the ground of its unconstitutionality. The stat

ute under which the board herein acted, and the board’s

order denying admission present a procedural picture al

most identical to that present in McLaurin v. Oklahoma,

•— U. S. —, 70 Sup. Ct. 851, decided by this Court this year.

In the McLaurin case, supra, there was a board operating

under a statute which provided that the board be constituted

“ a body corporate . . . ” and had “ all the powers neces

sary or convenient to accomplish the objectives and perform

the duties prescribed by law.” Title 70 Okla. Stat., section

1242. The statute under which appellant board herein oper

ates provides that it “ shall constitute a body corporate and

5

Lave power and authority to perform all acts for the bene

fit of the University which are incident to bodies corporate”

and “ to adopt and alter all rules and regulations which may

be deemed necessary or convenient to accomplish the objec

tives and perform the duties prescribed by law . .

Louisiana General Statutes (Dart) Section 2503.3.

Operating* under the Oklahoma statute, the Oklahoma

State Regents issued the following order:

“ That the Board of Regents of the University of

Oklahoma authorize and direct the President of the

University, and the appropriate officials of the Univer

sity, to grant the application for admission to the Grad

uate College of G. W. McLaurin in time for Mr. Mc-

Laurin to enroll at the beginning of the term, under

such rules and regulations as to segregation as the

President of the University shall consider to afford to

Mr. G. W. McLaurin substantially equal educational

opportunities as are afforded to other persons seeking

the same education in the Graduate College and that the

President of the University promulgate such regula

tions.”

Almost parallel thereto is the order of the Board of

Supervisors of Louisiana State University and Agricul

tural and Mechanical College, which states:

“ B e It R esolved that pursuant to the laws of Loui

siana and the policies of this Board the administrative

officers are hereby directed to deny admission to the

following applicants: Nephus Jefferson, Dan Colum

bus Simon, Willie Cleveland Patterson, Charles Ed

ward Coney, Joseph II. Miller, Jr., Roy Samuel Wilson,

Lloyd E. Milburn, Lawrence Alvin Smith, Jr., James

Lee Perkins, Edison George Hogan, Harry A. Wilson,

Anderson Williams.”

The order herein involved is of the same type as the order

in the McLaurin case. The authorizing statutes in the

two cases are almost identical. This assignment of error

is therefore without merit.

II

The appellants other assignments of errors are likewise

without merit.

(a) It is alleged that the Court was without jurisdiction

“ because no state statute is being attacked.” This conten

tion was answered by the District Court in its citation of

Oklahoma Natural Gas Company v. Russel, 261 U. S. 290,

In that case, Mr. Justice Holmes wrote:

‘ ‘ So, if the section is construed with narrow precision

it may be argued that the unconstitutionality of the

order is not enough. But this court has assumed re

peatedly that the section was to be taken more broadly

. . . We mention the matter simply to put doubts

to rest.” (261 U. S. at 292)

(b) The assignment of error then asserts that the order

attacked herein is not “ an order made by an administrative

board or commission acting under State statutes such as is

cognizable by a three-judge court in view of the decisions in

the cases of Railroad Commission of Texas v. Pullman

Company, 312 U. S. 496, 61 S. Ct. 643, 85 L. Ed. 971; Phil

lips v. United States, 312 U. S. 246, 61 S. Ct. 480, 85 L. Ed.

800 and Borges v. Loftis, 87 F. 2d 734, 301 U. S. 687, 57

S. Ct. 789, 81 L. Ed. 1344, 301 IT. S. 714, 57 Sup. Ct. 928,

81 L. Ed. 1365.” Appellee submits that the cases in no way

control this case. The Railroad Commission case, first did

not determine the jurisdiction or lack thereof, of a three-

judge court. It was a case which decided that equity, in its

discretion should not enter the field of federal-state rela

tions until after the resolution of an ambiguous state statute

by state courts. Moreover, the ambiguity in question left

7

undecided whether the Railroad Commission had the power

to issue the order under attack:

“ It is common ground that if the order is within the

Commission’s authority its subject matter must he in

cluded in the Commission’s power to prevent ‘ unjust

discrimination . . . and to prevent any and all

other abuses’ in the conduct of railroads. Whether

arrangements pertaining to the staff of Pullman cars

are covered by the Texas concept of ‘ discrimination’

is far from clear. What practices of the railroads may

be deemed to be ‘ abuses’ subject to the Commission’s

correction is equally doubtful. Reading the Texas stat

utes and the Texas decisions as outsiders without

special competence in Texas law, we would have little

confidence in our independent judgment regarding the

application of that law to the present situation. The

lower court did deny that the Texas statutes sustained

the Commission’s assertion of power. And this repre

sents the view of an able and experienced circuit judge

of the circuit which includes Texas and of two capable

district judges trained in Texas law. Had we or they

no choice in the matter but to decide what is the law

of the state, we should hesitate long before rejecting

their forecast of Texas law. But no matter how sea

soned the judgment of the district court may be, it

cannot escape being a forecast rather than a determi

nation. The last word on the meaning of Article 6445

of the Texas Civil Statutes, and therefore the last

word on the statutory authority of the Railroad Com

mission in this case, belongs neither to us nor to the

district court but to the supreme court of Texas.” (312

U. S. at 499)

The case was then remanded to the same three-judge district

court before which it had been brought with instructions for

said court to retain jurisdiction until resolution of the

ambiguity by state courts. This action in itself shows that

the Pullman case did not define any situation in which

a three-judge court does not have jurisdiction.

8

Herein there is no question of the Board’s power to issue

the order excluding appellee. The statute under which the

board operates is clear, and neither party has questioned

the power which it confers.

The Phillips case, supra, merely decided that the gover

nor of Oklahoma, acting in his gubernatorial capacity as

“ Commander in Chief of the Militia of the State” was not

enforcing a statute, nor acting as an administrative board,

nor enforcing the orders of such board, and was therefore

not subject to attack via three-judge court procedure. Con

cerning alleged jurisdiction stemming from a statute, the

opinions stated:

“ In other words, it seeks a restraint not of a statute

but of an executive action.” (312 U. S. at 252)

On the jurisdictional question insofar as a three-judge

court was concerned the opinion distinguished the case

from the case of Sterling v. Constantin, 287 U. S. 378 wherein

it was stated:

‘ ‘ The Governor was sought to be restrained as part

of the main objective to enjoin ‘ the execution of an

order made by an administrative . . . commission,’

and as such was indubitably within § 268.” (Ibid at

253)

The third case which appellants cite is Borges v. Loftis,

supra. The Borges case involved a county ordinance re-:

quiring that cattle should be subjected to a test for tuber

culosis, and that tubercular cattle should be slaughtered.

The Court of Appeals held that the action was premature.

The Court stated:

“ . . . until there is an adverse finding as to the

health of some or all of their cattle, appellants who

alleged that their cattle are free from disease cannot

involve the aid of the court upon the assumption that

9

a well-recognized scientific test required by the ordi

nance will show such healthy cattle to be diseased.”

(87 F. 2d at 735) -

The court also stated that the county ordinance there in

issue was not a state statute within the meaning of what

is now Title 28 U.S.C. § 2281.

The order in this case, and the board issuing it, are essen

tially similar to the order and board in McLaurin v. Okla

homa, supra, as hereinbefore stated.

I l l

The other assignments of error are directed: (a) to the

finding that the State of Louisiana “ does not afford to

the plaintiff educational advantages equal to those he

would receive if admitted to the Department of Law of

Louisiana State University and Mechanical College; ’ ’ and

(b) to the conclusion of law that the enforcement of the

order involved “ denies a right guaranteed to plaintiff by

the Fourteenth Amendment and that enforcement of the

order, pending- final hearing, would inflict irreparable dam

ages upon the plaintiff.

The finding that the law school education offered the

appellee in the segregated law school for Negroes was not

equal to that offered all other qualified applicants to Loui

siana State University was in direct conformity with the

decision of the Supreme Court in the case of Sweatt v.

Painter.

With this finding of fact there can be no doubt that such

inequality denies to the appellee the equal protection of

the laws guaranteed him by the Fourteenth Amendment.

10

Conclusion

W herefore, appellee respectfully moves that the within

appeal be dismissed or that the judgment of the District

Court of the United States for the Eastern District of Loui

siana be affirmed.

A. P. T ureattd,

612 Iberville St.,

New Orleans, La.,

T hurgood Marshall,

20 West 40th Street,

New York, New York,

Counsel for Appellees.

Dated: November 13, 1950.

(1590)

. . . .