Ford v. Wainwright Brief for Petitioner-Appellant

Public Court Documents

July 30, 1984

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Ford v. Wainwright Brief for Petitioner-Appellant, 1984. 15d0aa1b-b29a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/36cb20c2-5d94-4d66-a9d1-a12d750642e2/ford-v-wainwright-brief-for-petitioner-appellant. Accessed February 24, 2026.

Copied!

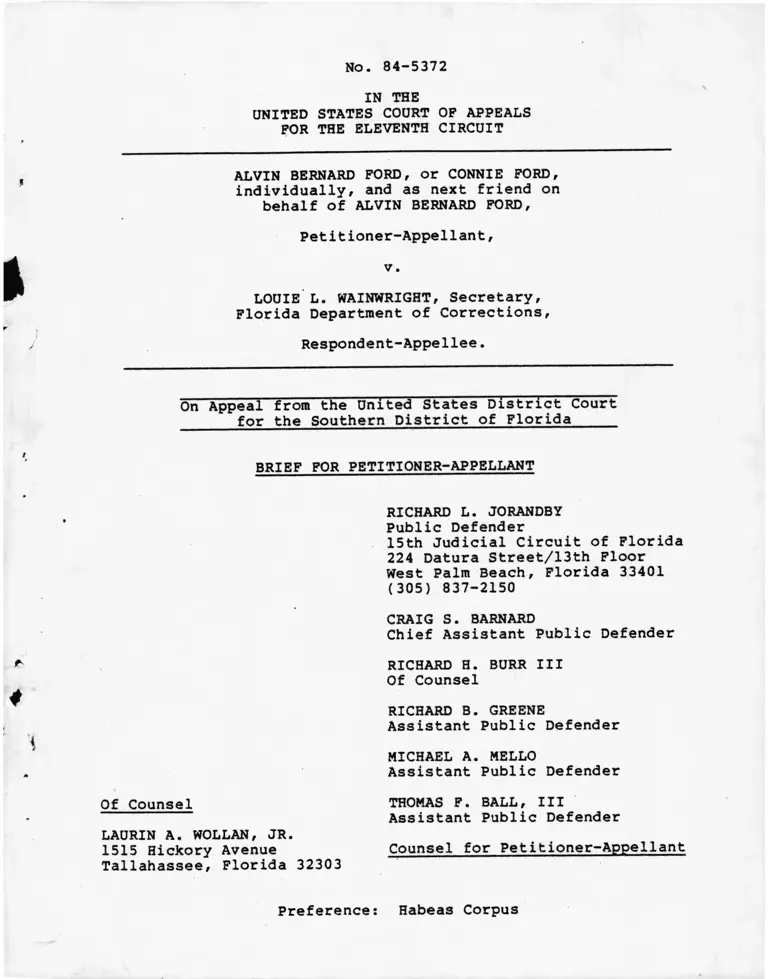

No. 84-5372

*

IN THE

UNITED STATES COURT OP APPEALS

FOR THE ELEVENTH CIRCUIT

ALVIN BERNARD FORD, or CONNIE FORD,

individually, and as next friend on

behalf of ALVIN BERNARD FORD,

Petitioner-Appellant,

v.

LOUIE L. WAINWRIGHT, Secretary,

Florida Department of Corrections,

Respondent-Appellee.

On Appeal from the United States District Court

______ for the Southern District of Florida_____

BRIEF FOR PETITIONER-APPELLANT

RICHARD L. JORANDBY

Public Defender

15th Judicial Circuit of Florida

224 Datura Street/13th Floor

West Palm Beach, Florida 33401

(305) 837-2150

CRAIG S. BARNARD

Chief Assistant Public Defender

f- RICHARD H. BURR III

Of Counsel

w

■ ’i

RICHARD B. GREENE

Assistant Public Defender

MICHAEL A. MELLO

Assistant Public Defender

■

Of Counsel

LAURIN A. WOLLAN, JR.

1515 Hickory Avenue

THOMAS F. BALL, III

Assistant Public Defender

Counsel for Petitioner-Appellant

Tallahassee, Florida 32303

Preference: Habeas Corpus

No. 84-5372

IN THE

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE ELEVENTH CIRCUIT

ALVIN BERNARD FORD, or CONNIE FORD,

individually, and as next friend on

'behalf of ALVIN BERNARD FORD,

Petitioner-Appellant,

v .

LOUIE L. WAINWRIGHT, Secretary,

Florida Department of Corrections,

Respondent-Appellee.

On Appeal from the United States District Court

for the Southern District of Florida______

BRIEF FOR PETITIONER-APPELLANT

RICHARD L. JORANDBY

Public Defender

15th Judicial Circuit of Florida

224 Datura Street/13th Floor

West Palm Beach, Florida 33401

(305) 837-2150

CRAIG S . BARNARD

Chief Assistant Public Defender

RICHARD H. BURR III

Of Counsel

RICHARD B. GREENE

Assistant Public Defender

MICHAEL A. MELLO

Assistant Public Defender

Of Counsel THOMAS F. BALL III

Assistant Public Defender

LAURIN A. WOLLAN, JR.

1515 Hickory Avenue Counsel for Petitioner-Appellant

Tallahassee, Florida 32303

Preference: Habeas Corpus

STATEMENT REGARDING PREFERENCE

This is an appeal from the denial of a petition for writ of nabeas corpus

(sought under 28 U.S.C. §2254) by the United States District Court for the

Southern District of Florida. As such, it is to be given preference in

processing and disposition. Local Rule 11, Appendix One (a) (3).

STATEMENT REGARDING ORAL ARGUMENT

Petitioner, pursuant to Local Rule 22 (f) (4), requests oral argument of

this appeal. This appeal is frcm the denial of habeas corpus and involves a

complex constitutional issue of first impression in this or any other court

concerning the administration of capital punishment in this Nation.

TABLE OF CONTENTS

PAGE

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES ............................................... vi

STATEMENT OF THE ISSUES PRESENTED ................................. 1

STATEMENT OF THE CASE ............... ............................... 1

A. Course of Proceedings ...... .............................. 1

JT

B. Statement of Material Facts ............................... 4

C. Standard of Review ......... .............................. 10

SUMMARY OF THE ARGUMENT.............................................. 10

STATEMENT OF JURISDICTION ............................................ 13

ARGUMENT

I. t h e EIGHTH AMENDMENT PRECLUDES THE EXECUTION OF THE

PRESENTLY INCOMPETENT....................................... 13

A. Introduction ............................ 13

B. Intent of the Framers .................................. 14

1. A "Savage" Act of "Extreme Inhumanity and

Cruelty" .......................................... 15

2. "Nor Cruel and Unusual Punishments Inflicted" ... 18

3. Conclusion: The Framers Intended to Prohibit

Cruel Punishments .and Execution of the Insane was

Known by the Framers to be Cruel and Inhuman ... 21

C. Traditional Eighth Amendment Jurisprudence ............ 22

1. Contemporary Standards of Decency: Uniform

Disapproval ....................................... 23

2. Independent Judicial Assessment ................... 24

3. Conclusion: Execution of the Insane Also Fails

Traditional Eighth Amendment Analysis ............ 33

-iii-

34

34

34

36

37

38

41

42

43

44

45

45

sa

g

III.

EVIDENTIARY HEARING MUST BE HELD IN THE DISTRICT COURT

DETERMINE MR. FORD'S PRESENT COMPETENCY TO BE EXECUTED,

REQUIRED BY THE THE EIGHT AMENDMENT ...................

A. Introduction .........................................

B. Jurisdiction: "In Custody In Violation of the

Constitution" ........................................

C. Florida's Gubernatorial Proceeding ..................

D. Florida's Gubernatorial Proceeding Is Inadequate to

Reliably Vindicate the Eighth Amendment Right .......

1. Florida's Procedures Are Untrustworthy .........

2. Florida Applies A Competency Standard Less Than

That Required By The Eighth Amendment ..........

3. Analogous Areas of the Law Where Determination of

Competency is Required Suggests that Florida's

Procedure is Inadequate ........................

4. Florida's Procedure Is Not Entitled to a

Presumption of Correctness .....................

E. Conclusion: An Evidentiary Hearing is Required in The

District Court On Mr. Ford's Competency to be

Executed .............................................

THE RIGHT NOT TO BE EXECUTED WHILE INCOMPETENT AS ESTAB

LISHED BY STATE LAW CANNOT BE WITHDRAWN WITHOUT PROCEDURAL

DUE PROCESS PROTECTIONS REQUIRED BY THE EIGHTH AND FOUR

TEENTH AMENDMENTS .........................................

A. Introduction .........................................

B. Solsbee v. Balkccm No Longer Measures the Process Due

to the Condemned in Determining Competency at the Time

of Execution .........................................

C. Florida Has Created as a Matter of State Law a

Protectible Expectation that a Condemned Person Who Is

Insane at the Time of Execution Will Not Be Executed .

-iv-

PAGE

D. The Right Not TO Be Executed When Incompetent Requires

the Same Due Process Protection as the Right Not TO Be

Tried When Incompetent ............................... 56

1. The Private Interest At Stake .................. 56

2. The Government's Interests At Stake ............ 57

3. Risk of Erroneous Deprivation and the Benefit of

Additional Safeguards ........................... 58

4. Due Process and the Death Penalty .............. 58

E. Conclusion ........................................... 59

IV. PETITIONER'S CLAIM THAT THE DEATH SENTENCE IS ADMINISTERED

IN FLORIDA IN AN ARBITRARY AND DISCRIMINATORY MANNER IN

VIOLATION OF THE EIGHTH AND FOURTEENTH AMENDMENTS CANNOT BE

DETERMINED UNTIL THE RESOLUTION BY THE EN BANC COURT OF THE

CONSTITUTIONAL STANDARDS GOVERNING SUCH A CLAIM ........... 60

CONCLUSION ......................................................... 65

APPENDIX: EXECUTION OF THE INCOMPETENT:

A National Survey of State Policies ..................... la

CERTIFICATE OF SERVICE

-v-

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

Cases Cited Page

* Adams v. Wainwright, 734 F.2d 511

(11th Cir. 1984) ....................................... 61

Addington v. Texas, 441 U.S. 418

(1979) ................................................... 39

Aldridge v. Wainwright, 433 So.2d 988

(Fla. 1983) ............................................. 63

Anderson v. Kentucky, 376 U.S. 940

motion to correct order denied,

377 U.S. 902 (1964) .................................... 31

Arnett v. Kennedy, 416 U.S. 134

( 1974) ................................................... 47

Barefoot v. Estelle, ___ U.S.___ ,

103 S.Ct. 3383 (1983) ................................. 30,64

Barker v. State, 75 Neb. 289,

106 N.W. 450 ( 1905) .................................... 23

Beck v. Alabama, 447 U.S. 625

(1980) ................................................... 23,59

Bell v. Burson, 402 U.S. 535

(1971) ................................................... 49,56,57

Blackledge v. Allison, 431 U.S. 63

(1977) ................................................... 44

Board of Regents v. Roth, 408 U.S. 564

(1972) ................................................... 54

* Bounds v. Smith, 430 U.S. 817

(1977) ........ .......................................... 27,28

Braden v. 30th Judicial Circuit Court,

410 U.S. 484 ( 1973) ..........'......................... 35

Caritativo v. California, 357 U.S. 549

( 1958) ................................................... 14,49

Chaudoin v. State, 383 So.2d 645

(Fla. 5th DCA 1980) .................................... 63

Coker v. Georgia, 433 U.S. 584

(1977) ................................................... 23,24,32

-vi-

Page

Connecticut Board of Pardons v. Dumschat,

452 U.S. 458 (1981) ............................... ____ 53

Dixon v. Love, 431 U.S. 105

(1977) .............................................. _____ 56

* Drope v. Missouri/ 420 U.S. 162

(1975) .............................................. _____ 27,59

Duncan v. Louisiana, 391 U.S. 145

(1968) ............................. ................ _____ 14

Dusky v. United States, 362 U.S. 402

(1960) .............................................. ..... 41

Enmund v. Florida, 458 U.S. 782

( 1982) ............................................. ■..... 23,32

Escoe v. Zerbst, 295 U.S. 490

(1935) ............................................. ..... 47,48,50

51

Evans v. Bennett, 440 U.S. 987

(1979), vacating stay of execution,

440 U.S. 1301 (1979) ............................ ..... 31

Evans v. Bennett, 440 U.S. 1301

(1979) ............................................. ..... 30

Ex parte Bollman, 8 U.S. (4 Cranch) 75

(1807) ............................................. ..... 27,35

Ex parte Chesser, 93 Fla. 291, 111 So. 720

(1927) ............................................. ..... 36,53

* Ex parte Chesser, 93 Fla. 590, 112 So. 87

(1927) ............................................. ..... 23,53,54

Ex parte Lange, 85 U.S. (18 Wall.) 163

(1873) ............................................. ..... 35

Ex parte McCardle, 74 U.S. (7 Wall.) 506

(1868) ..........................•................... ..... 27

Ex parte Watkins, 28 U.S (3 Pet.) 193

(1830) ............................................. ..... 35

Fay v. Noia, 372 U.S. 391

(1963) ............................................. ..... 35

Fogel v. Chestnutt, 668 F.2d 100

(2d Cir. 1981) ................................... ..... 61

-vii-

Page

Ford v. Strickland, 734 F.2d 538

(11th Cir. 1984) ................................. ....... 44,60,61

Ford v. Wainwright, 451 So.2d 471,

(Fla. 1984) ....................................... ....... 36,46,53

Foster v. State, 400 So.2d 1

(Fla. 1981) ....................................... ...... 64

Fuentes v. Shevin, 407 U.S. 67

(1972) ............................................. ...... 58

* Furman v. Georgia, 408 U.S. 238

(1972) ............................................ ....... 18,19,20

22

* Gagnon v. Scarpelli, 411 U.S. 778

(1973) ............................................ ...... 50,51,60

* Gardner v. Florida, 430 U.S. 349

(1977) ............................................ ...... 39,52,59

Gilmore v. Utah, 429 U.S. 1012

(1976) ............................................ ...... 31,42

Goldberg v. Kelly, 397 U.S. 254

(1970) ............................................ ...... 49,57

Goode v. Wainwright, 448 So.2d 999

(Fla. 1984) ...................................... ...... 12,36,37

38,53

* Goode v. Wainwright, 731 F.2d 1482

(11th Cir. 1984) ................................ ...... 36,46,57

Goss v. Lopez, 419 U.S. 565

(1975) ............................................ ...... 58

Graham v. Richardson, 403 U.S. 365

(1971) ............................................ ...... 49

Gray v. Lucas, 710 F.2d 1048

(5th Cir. 1983), cert.denied,

U.S. , 104 S.Ct. 211 (1983) ............ ...... 11,14,23

42

Gray Panthers v. Schweiker, 652 F.2d 146

(D.C. Cir. 1980) ................................ ...... 39

Green v. Georgia, 442 U.S. 95

(1979) ............................................ ...... 59

-viii-

* Greenholtz v. Inmates of Nebraska Penal and

Correctional Complex, 442 U.S. 1 (1979) ........... 50,51,54

55

* Gregg v. Georgia, 428 U.S. 153

(1976) ................................................... 11,20,22

24,26,32

33

Guice v. Fortenberry, 661 F.2d 496

(5th Cir. 1981) ........................................ 38

Hawie v. State, 121 Miss. 197, 83 So. 158

(1919) ................................................... 23

Hawk v. Olson, 326 U.S. 271

(1945) ................................................... 35

* Hays v. Murphy, 663 F.2d 1004

(10th Cir. 1981) ....................................... 40,44

Hewitt v. Helms, U.S. , 103 S.Ct. 864

(1983) ................................................... 55

Hicks v. Oklahoma, 447 U.S. 343

(1980) ................................................... 50

Hitchcock v. State, 432 So.2d 42

(Fla. 1983) ............................................. 63

Hunter v. Wood, 209 U.S. 205

( 1908) ................................................... 36

Hurtado v. California, 110 U.S. 516

(1884) ................................................... 15

Hysler v. State, 136 Fla. 563, 187 So. 261

(1939) ................................................... 36,53

In re Kemmler, 36 U.S. 436

( 1890) ................................................... 20

In re Loney, 134 U.S. 372

( 1890) ................................................... 36

In re Neagle, 135 U.S. 1

( 1890) ................................................... 36

In re Smith, 285 N.M. 48, 176 P. 819

(1918) ................................................... 23

Jackson v. State, 438 S o .2d 4

(Fla. 1983) ............................................. 63

-lx-

Page

* Johnson v. Avery, 393 U.S. 483

(1969) ................................................... 27,29,30

Johnson v. Zerbst, 309 U.S. 458

( 1938) ................................................... 35

Joint Anti-Fascist Refugee Comm. v. McGrath,

341 U.S. 123 (1951) .................................... 39,50

Kelly v. Wyman, 294 F.Supp. 893

(S.D.N.Y. 1968) ........................................ 57

Lenhard v. Wolff, 443 U.S. 1306 (1979),

vacating stay of execution,

444 U.S. 807 (1979) .................................... 31

Lockett v. Ohio, 438 U.S. 586

(1978) ................................................... 31

* Logan v. Zimmerman Brush Co., 455 U.S. 422

(1982) ................................................... 50,55,56

Massie v. California, No. 68-5025

(U.S. Mar. 6, 1969), cert, denied as m o o t ,

406 U.S. 971 (1972) .................................... 31

Mathews v. Eldridge, 424 U.S. 319

(1976) ................................................... 56,58

* McCleskey v. Zant, No. 84-8176 (pending) ............. 17,60,64

McGautha v. California, 402 U.S. 183

(1971) ................................................... 19

Memphis Light, Gas & Water Div. v. Craft,

436 U.S. 1 (1978) ...................................... 56

Moore v. Dempsey, 261 U.S. 86

( 1923) ................................................... 35

* Morrissey v. Brewer, 408 U.S. 471

(1972) 49,50

Mullane v. Central Hanover Trust Co.,

339 U.S. 306 ( 1950) .................................... 58

Musselwhite v. State, 215 Miss. 363, 60 So.2d 807

(1952) ................................................... 32

Nobles v. Georgia, 168 U.S. 398

(1897) ................................................... 14

-x-

Page

Pate v. Robinson, 383 U.S. 375

(1966) 59

People v. Scott, 326 111. 327, 157 N.E. 247

(1927) ................................................... 29

Phyle v. Duffy, 34 Cal.2d 144, 208 P.2d 668

(1949) .........'.......................................... 47

Phyle v. Duffy, 334 U.S. 431

(1948) ................................................... I4

Preiser v. Rodriguez, 411 U.S. 475

( 1973) ...... '............................................. 35

* Rees v. Peyton, 384 U.S. 312

(1966) ................................................... 31,42

Rees v. Peyton, 386 U.S. 989

(1967) ................................................... 31

Ritter v. Smith, 726 F.2d 1505

(11th Cir. 1984) ....................................... 61

Robinson v. California, 370 U.S. 660

( 1962) ................................................... 14,26

Rogers v. Lodge, 458 U.S. 613

(1982) ................................................... 64

Rushing v. State, 233 So.2d 137

(Fla. 3d DCA 1970) ..................................... 63

Sanders v. United States, 373 U.S. 1

(1963) ................................................... 63

Shaw v. Martin, 613 F.2d 487

(4th Cir. 1980) ........................................ 30

Shriner v. Wainwright, ___ F.2d___ No. 84-3394

(11th Cir., June 19, 1984) ........................... 29

Smith v. Kemp, ___ U.S.___ , 104 S.Ct. 565

( 1983) ................................................... 62

* Solem v. Helm, ___ U.S.___ , 103 S.Ct. 3001

( 1983) ................................................... 11,19

* Solesbee v. Balkcom, 339 U.S. 9

(1950) passim

Solesbee v. Balkcom, 205 Ga. 122, 52 S .E .2d 433

(1949) ................................................... 54

-xi-

Page

* Spencer v. Zant, 715 F.2d 1562,

vacated for rehearing en banc,

715 F . 2d 1583 (11th Cir. 1983) ...............

State v. Allen, 204 La. 513, 15 So.2d 870

(1943) ............................................

* State ex rel. Deeb v. Fabisinski, 111 Fla. 454,

152 So. 207 (1933) .............................

* Stephens v. Kemp, ___ U.S.___ 104 S.Ct. 562

(1983) ............................................

Strickland v. Francis, ___ F.2d___ , No. 83-8572,

(11th Cir., July 31, 1984) ....................

Sullivan v. Wainwright, 721 F .2d 316

(11th Cir. 1983), petition for stay

of execution denied, ___ U .S .___ ,

104 S.Ct. 450 (1983) ...........................

Thomas v. Zant, 697 F .2d 977

(11th Cir. 1983) ................................

Thompson v. Dilley, 275 So.2d 234

(Fla. 1973) ......................................

Tobler v. State, 350 So.2d 555

(Fla. 1st DCA 1977) ............................

* Townsend v. Sain, 372 U.S. 293

(1963) ............................................

13.60.64

23

53,54

62.64

57

62

38

63

63

12,28,35

37,44

Trop v. Dulles, 356 U.S. 86

(1958) ...........................................

Turney v. Ohio, 273 U.S. 510

(1927) ...........................................

Ughbanks v. Armstrong, 208 U.S. 481

(1908) ...........................................

United States v. Hamilton, 3 U.S. (Dali.) 17

(1795) ...........................................

* Vitek v. Jones, 445 U.S. 480

(1980) ...........................................

Wainwright v. Ford, ___ U.S.___ , 104 S.Ct. 3498

(1984) ...........................................

22,24

48

47,48,50

35

50

14,60,61

63,64

— x i i —

Page

Wainwright v. Sykes, 433 U.S. 72

(1977) ................................................... 35,64

Waley v. Johnston, 316 U.S. 101

(1942) ................................................... 35

Weems v. United States, 217 U.S. 349

(1909) .........'.......................................... 19,20

Williams v. Florida, 399 U.S. 78

( 1970) ................................................... 34

* Williams v. New York, 337 U.S. 241

(1949) ................................................... 48,49,51

52

Woodard v. Hutchins, ___ U.S.___ , 104 S.Ct. 752

(1984) ................................................... 34

Woodson v. North Carolina, 428 U.S. 280

(1976) ................................................... 23,24,59

Statutes and Rules

Florida Statutes (1983)

Section 922.07 .................................... passim

Florida Rules of Criminal Procedure

Rule 3.210 ........................................ 57

Rule 3.850 ........................................ 63

Florida Constitution

Article V, Section 2(a) ......................... 63

United States Code

Title 28, Section 2241 ........................... 34,36,39

Title 28, Section 2243 .......................... 44

Title 28, Section 2254 ........................... 11,28,34

36,38,43

Title 28, Section 2255 .......................... 44

Books and Treatises

1 J. Archbold, A Complete Practical Treatise

on Criminal Procedure (8th ed. 1879) ............... 17

P. Bator, P. Mishkin, D. Shapiro and H. Wechsler,

Hart and Wechsler's The Federal Courts and the

Federal System (2d e d . 1973 Supp. 1977) ........... 27

-xiii-

Page

R. Berger, Death Penalties (1982) ...................... 18

4 W. Blackstone, Commentaries on the Law

of England (1768) ...................................... Passim

1 J. Chitty, A Practical Treatise on the

Criminal Law (1819) .................................... 16,20

E. Coke, Third Institute (1644) ......................... 10,16

Collinson, A Treatise on Law Concerning

Idiots, Lunatics, and Other Persons

Non Compotes Mentis (1812) ........................... 33

T. Cooley, A Treatise on Constitutional

Limitations (7th ed. 1903) ........................... 19

G. Elton, England Under the Tudors (1960) ............ 16

FitzHerbert, Natura Brevium (1534) ..................... 15

S. Glueck, Mental Disorder and the Criminal Law

(1925) ................................................... I5

1 M. Hale, The History of the Pleas of the Crown

(1736) ................................................... 16,18,26

58

1 W. Hawkins, A Treatise on the Pleas of the

Crown (1716) ............................................ 16

Hunard, The King's Pardon for Homicide Before A .D .

1307 (1969) ............................................. 15

R. Johnson, Condemned to Die;

Under Sentence of Death (1981) ...................... 30

1 I. Ray, Treatise on the Medical Jurisprudence

of Insanity (5th e d . 1871) ........................... 21

Rosenberg, The Trial of the Assassin Guiteau,

Psychiatry in the Gilded Age ( 1968) ................ 21

1 W. Russell, A Treatise on Crimes and Indictable

Misdemeanors (3d Amer. e d . 1836) .................... 21

2 J. Stephen, A History of the Common Law of England

( 1883) ................................................... 15

F. Wharton, A Treatise on the Criminal Law of the

United States (2d e d . 1852) .......................... 20

-xiv-

Page.

Period icals

Amsterdam, Criminal Prosecutions Affecting

Federaly Guaranteed Civil Rights: Federal

Removal and Habeas Corpus Jurisdiction

to Abort State Court Trial,

113 U.Pa. L. Rev. 793 (1965) ......................... 35

B a tor, Finality in Criminal Law and Federal

Habeas Corpus for State Prisoners,

76 Harv. L.Rev. 441 (1963) ........................... 35

Ennis and Litwack, Psychiatry and the Presumption

of Expertise: Flipping Coins in the Courtroom,

62 Cal. L.Rev. 693 (1974) ............................ 39

Granucci, "Nor Cruel and Unusual Punishments

Inflicted;'1' The Original Meaning,

57 Cal. L.Rev. 839 (1969) ............................ 18

Hazard and Louisell, Death, the State, and the

Insane: Stay of Execution,

9 UCLA L.Rev. 381 (1962) ............................. 25,42

Pizzi, Competency to Stand Trial in Federal Courts

Conceptual and Constitutional Problems,

45 U.Chi. L.Rev. 21 (1977) ........................... 39

Radin, Cruel Punishment and Respect For Persons;

Super Due Process For Death,

53 S.Cal. L.Rev. 1143 (1980) ........................ 59

Sayre, Mens Rea, 45 Harv. L.Rev. 974

(1931-32) ................................................ 15

Strafer, Volunteering for Execution; Competency

Voluntariness and the Proprierty of Third Party

Intervention,

74 J. Crim. L. & Criminology 860 (1983) ........... 31,40

Note, Incompetency to Stand Trial,

81 Harv. L.Rev. 455 (1967) ........................... 32

Note, The Eighth Amendment and the Execution of

the Presently Incompetent,

32 Stan. L. Rev. 765 (1980) .......................... 21

Note, Insanity of the Condemned,

88 Yale L.J. 533 ( 1979) ............................... 23,32,42

Comment, An End to Incompetency to Stand Trial,

13 Santa Clara L.Rev. 560 (1973) .................... 39

-xv-

Comment, Execution of Insane Persons,

235 Cal. L.Rev. 246 ( 1950) ........................... 42

Comment, Capital Sentencing--

Effect of McGautha and Furman,

45 Temp. L.Q. 619 ( 1972) ............................. 86

Page

Reports

Department of Economic and Social Affairs,

United Nations D o c .ST/SOA/SD/9,

Capital Punishment (1962) ............................ 24

Department of Economic and Social Affairs,

United Nations Doc. ST/SOA/SD/10,

Capital Punishment: Developments 1961-1965

(1967) ................................................... 24

Massachusettes Committee on Capital Punishment

Report (1836) ........................................... 2^

Royal Commission on Capital Punishment,

1949-1953 Report (1953) ............................... 21,25,42

Other Sources * 11

21 American Jurisprudence 2d, Criminal Law §123 ..... 42

Hawles, Remarks on the Trial of Mr. Charles Bateman,

11 State Trials 474 (1816) ........................... 16,17,26

58

-xvi-

STATEMENT OF THE ISSUES PRESENTED

1. Whether the eighth amendment's prohibition of cruel and unusual

punishment forbids the execution of a condemned person who is incompetent at

the time of execution?

2. If the eighth amendment does forbid the execution of the incompetent,

whether a federal habeas court must hold an evidentiary hearing to determine

the competency of such a person, where the only prior state determination of

competency was made in an ex parte, non-judicial proceeding?

3. Whether a state-created entitlement not to be executed when incom

petent can be withdrawn without due process of law?

4. Whether petitioner's claim that the Florida death penalty is admin

istered in an arbitrary and discriminatory manner on the basis of race and

other impermissible factors may be determined prior to the resolution of the

constitutional standards governing such a claim by the pending en banc cases of

this Court?

STATEMENT OF TOE CASE

This case is on appeal from the order of the United States District Court

for the Southern District of Florida (Honorable Norman C. Roettger, Jr.,

District Judge) summarily dismissing Mr. Ford's application for a writ of

habeas corpus (R 1-112).l

A. Course of Prior Proceedings

On December 7, 1974, Alvin Bernard Ford was convicted of first degree

murder in the Circuit Court for the Seventeenth Judicial Circuit, Broward

County, Florida, for a murder committed during an attempted robbery of a

1 Reference to the record before this Court is designated "R" with the approp

riate pages cited thereafter. Because the transcript of the proceedings before

the district court was paginated separately, however, references to that part

of the record will be designated "RT" with the appropriate pages cited there

after.

-1-

restaurant by four persons. On January 6, 1975, following a jury recommendation

of death, Mr. Ford was sentenced to death. The Florida Supreme Court affirmed

the conviction and death sentence, Ford v. State, 374 So.2d 496 (Fla. 1979),

and certiorari was denied on April 14, 1980, Ford v. Florida, 445 LJ.S. 972.

Thereafter, Mr. Ford pursued state post-conviction and federal habeas

corpus remedies. His motion for post-conviction relief pursuant to Florida

Rule of Criminal Procedure 3.850 was denied by the Circuit Court in Broward

County, and its denial was affirmed by the Florida Supreme Court. Ford v.

State, 407 So.2d 907 (Fla. 1981). Mr. Ford's subsequent petition for a writ

of habeas corpus in the United States District Court for the Southern District

of Florida was denied in an unreported opinion, and on April 15, 1982, a

divided panel of this Court affirmed the district court's denial of relief.

Ford v. Strickland, 676 F.2d 434 (11th Cir. 1982). Rehearing en banc was

granted, and the en banc court affirmed the district court's judgment. Ford v.

Strickland, 696 F.2d 804 (11th Cir. 1982). Certiorari was thereafter denied.

Ford v. Strickland, ___U.S.___, 104 S.Ct. 201 (1983).

On October 20, 1983, the undersigned counsel invoked the procedures of

Fla. Stat. § 922.07 (1983) on behalf of Mr. Ford. Pursuant to this statute, the

Florida governor appointed a commission of three psychiatrists to evaluate Mr.

Ford's current sanity in light of the statutory standards for determining

sanity at the time of execution. The commission members each thereafter

reported their findings, and on April 30, 1984, the governor signed a Death

Warrant ordering Mr. Ford's execution. No written findings were made by the

governor with respect to Mr. Ford's sanity.

On May 21, 1984, petitioner filed in the state trial court a Motion for a

Hearing and Appointment of Experts for Determination of Competency to be

Executed, and for a Stay of Execution During the Pendency Thereof, together

with a supporting memorandum of law and an extensive appendix containing

-2-

documentation of Mr. Ford's present incompetency. Within four hours of filing

these pleadings, the judge denied the motion without findings.

This Order was appealed to the Florida Supreme Court. On May 25, 1984 the

court denied relief, holding that there is no judicial remedy in Florida for

the determination of competency to be executed: "[I]n Goode we held that under

[Florida Statutes] section 922.07 the governor can make the determination;

Goode does not stand for the proposition that the issue of sanity to be

executed can be raised independently in the state judicial system." Ford v .

State, 451 So.2d 471, 475 (Fla. 1984). The court also denied by that opinion

an original petition for writ of habeas corpus.

Thereafter petitioner filed his petition for writ of habeas corpus in the

United States District Court for the Southern District of Florida. The cause

was assigned to the Honorable Norman C. Roettger, Jr., who heard argument on

petitioner's application for a stay of execution on May 29, 1984. On the same

date, Judge Roettger denied the habeas corpus petition on the basis of the

following:

I find that there is an abuse of the writ throughout this

matter. But reaching the merits as well I find no reason to

grant the relief sought by the Petitioner. The Governor of

this State acting under 922.07 the Court finds that he has

acted properly, has followed the steps. Each of. the three

psychiatrists whom he appointed has found the Defendant

sufficiently competent to be executed under the law and so on

the merits, as well as on this issue, the petition must

fail.

(KT 71-72).

On May 30, 1984, this Court granted a certificate of probable cause and

stayed petitioner's execution. Ford v. Wainwright, 734 F.2d 538. The Supreme

Court thereafter denied respondent's motion to vacate the stay of execution.

Wainwright v. Ford, ___U.S. ___, 104 S.Ct. 3498 (1984).

B. Statement of Material Facts

In the two-year period after December, 1981, Alvin Ford's mental health

gradually deteriorated. By November, 1983, he was found to be incompetent to

be executed. At that time Mr. Ford thought that he was on death row at Florida

State Prison only because he chose to be there. He thought that the case of

"Ford v. State" had ended capital punishment in Florida and, in particular, had

deprived the State of Florida of the right to execute him. After November,

1983, his incapacity worsened. He lost the ability to communicate by conven

tional means. He could only mutter softly to himself, making gestures in which

there seemed to be a message, but a message that no one could decipher. This

was his condition at the time this appeal began.

One of the questions presented by this appeal is whether these facts, set

forth in greater detail in the pages that follow, are sufficient to have

required an evidentiary hearing in the district court. In the related context

of trial competency, Drope v. Missouri, 420 U.S. 162, 180 (1975), has taught

that "evidence of a defendant's irrational behavior" and "any prior medical

opinion on competence" are especially material to whether an evidentiary

hearing should have been held. Accordingly, the evidence of Mr. Ford's

irrational behavior and of medical opinion concerning his competency is

summarized herein.

Prior to December, 1981, Mr. Ford did not suffer from psychosis. No

question concerning his competency had been raised before, during, or after his

trial. But gradually, from December, 1981 on, Mr. Ford began to lose touch with

reality.

This process began in an almost unnoticeable fashion: By December, 1981,

Mr. Ford began to believe that the personalities at a radio station in

Jacksonville talked to him over the radio (R 203-05). But it continued

relentlessly. He then began to believe that he wrote the subjects for the

_4_

radio station's opinion line (R 207-08), and thereafter, that he had the power

to see things in the world outside the prison that no one else, except those

vested with the same powers of perception, could see. Through his powers of

perception, Mr. Ford became convinced that he had found strong evidence

implicating the Ku Klux Klan in the arson of a house in Jacksonville in which a

black family was killed (R 210-30). Not long after this, Mr. Ford began to

believe that the Ku Klux Klan had placed several of its members as guards in

the prison. The task of these Klan members was to drive Mr. Ford to suicide. To

do so, the guards imprisoned and raped women in the "pipe alley" behind his

cell, put dead bodies in the concrete enclosure under his bunk in his cell, and

put semen on his food. See R 262-70.

Other conspiracies against him developed. He claimed that he had written

a book about Teddy Pendergrass which had been stolen from him and published

under another title by another author. Even though the book as published was

about Paul Robeson, Mr. Ford said that the book was merely an encoded version

of his work (R 266). Long time friends and people providing Mr. Ford support

over the years suddenly became enemies (R 262-70). All were joined in a giant

conspiracy with the Ku Klux Klan to drive him crazy or to make him commit

suicide (L3.). During the time that these events were taking place in the

mental life of Mr. Ford, he was not always obsessed by these thoughts. He had

interludes of clarity and of being in touch with reality (R 249-52, 254-56).

However, as time progressed, these interludes became fewer and much shorter.

By the fall of 1982, Mr. Ford seemed to be unable to regain contact with

reality. By this time the conspirators against him, most notably the members

of the Ku Klux Klan who were acting as correctional officers, had begun taking

hostages (R 318-19). At first Mr. Ford's mother, then other members of his

family, then his lav/yers, then radio and television personalities, and finally

politicians, and world political leaders — all became hostages in a machiavel

-5-

lian scheme to drive Mr. Ford to insanity. See, e.g., R 321-23, 325, 336,

348-350. For a period of months, Mr. Ford desperately wrote everyone he could

think of who had the power to assist him and begged for help in ending "the

hostage crisis." Mr. Ford repeatedly wrote President Reagan, the director of

the FBI, the state attorney in Jacksonville, Jim Smith and numerous assistant

attorneys general in the State of Florida, and numerous judges. See R 344-45,

352-62, 364-65. In each letter to each of these people, Mr. Ford recounted the

events leading up to the hostage crisis and begged for help. As time progres

sed, his pleas became more bizarre, less logical, and more nonsensical. Id. At

the same time, the events in Mr. Ford's world began to take on significance far

beyond him. Thus, in April, 1983, Mr. Ford wrote an attorney in Miami that

"this [hostage] crisis has to end, it is causing the racial unrest in your

City, namely Liberty City," (R 344).

By the summer of 1983, Mr. Ford's world changed again. He seemed to gain

new power within his world. As a result, he seemed to be in the process of

resolving the hostage crisis himself. For example, on May 10, 1983, he wrote

Attorney General Jim Smith: "I have fired a number of officials at the institu

tional level and state level, with the final approval, from the Governor, and

the President of the United States. Also your office." (R 359). And again,

on July 27, 1983, in a letter in which Mr. Ford referred to himself as Pope

John Paul III, he wrote,

Ibis investigation has been very successful, and to the exact

point of my past letters. It's unfortunate so many, prison

personnel will be cast in prison. Thankfully the CIA-FBI was

in fact able to investigate UCI, the attorney general's

office, all level of state and federal court. The Florida

State Supreme Court, I have appointed new justices, I have

appointed nine.

(R 372-73).

By November, 1983, Mr. Ford's communications from his world became more

fragmented. He was no longer centered on any particular subject, but would

"carry on" about a multiplicity of subjects all in one uninterrupted breath.

See, e.g., R 377-78. The best example of this behavior was captured by Dr.

Harold Kaufman, a psychiatrist who evaluated Mr. Ford on November 3, 1983 at

the request of Mr. Ford's counsel. Dr. Kaufman recorded Mr. Ford's speech as

the following on this date:

Mr. Ford: The guard stands outside my cell and reads my mind.

** Then he puts it on tape and sends it to the Reagans and

CBS...I know there is some sort of death penalty, but

I'm free to go whenever I want because it would be

illegal and the executioner would be executed...CBS is

trying to do a movie about my case...I know the KKK and

news reporters all disrupting me and CBS knows it. Just

call CBS crime watch... there are all kinds of people in

pipe alley (an area behind Mr. Ford's cell) bothering

me — Sinatra, Hugh Heffner, people from the dog show,

Richard Burr, my sisters and brother trying to sign the

death warrants so they don't keep bothering me...I

never see them, I only hear them especially at night.

(Note that Mr. Ford denies seeing these people in his

delusions. This suggest that he is honestly reporting

what his mental processes are.) I won't be executed

because of no crime...maybe because I'm a smart

ass...my family's back there (in pipe alley)...you

can't evaluate me. I did a study in the army...alot of

masturbation.. .1 lost alot of money on the stock

market. They're back there investigating my case. Then

this guy motions with his finger like when I pulled the

trigger. Come on back you'll see what they're up

to— Reagan's back there too. Me and Gail bought the

prison and I have to sell it back. State and federal

prisons. We changed all the other countries and

because we've got a pretty good group back there I'm

completely harmless. That's how Jimmy Hoffa got it. My

case is gonna save me.

** Comments in parentheses are [Dr. Kaufman's] own.

(R 433).

In the same conversation that Dr. Kaufman had with Mr. Ford, he asked Mr.

Ford, "are you going to be executed?" Mr. Ford replied, "I can't be executed

because of the landmark case. I won. Ford v. State will prevent executions all

over." (R 434). Thereafter, Dr. Kaufman and Mr. Ford carried on the following

colloquy:

Dr. Kaufman (Q): Are you on death row?

Mr. Ford (A): Yes.

__ "7 —

Q: Does that mean that the State intends to execute you?

A: No.

Q: Why not?

A: Because Ford v. State prevents it. They tried to get me

with the FCC tape but when the KKK came in it was up to CBS

and the Governor. These prisoners are rooming back there

raping everybody. I told the Governor to sign the death

warrants so they stop bothering me.

Id.

In December, 1983, communication with Mr. Ford became virtually impos

sible. In two interviews with Mr. Ford, on December 15 and December 19, 1983,

Mr. Ford spoke in a fragmented, code-like fashion. At times during these

interviews, Mr. Ford appeared to be trying to respond to questions posed to

him, but he seemed incapable of communicating by any of the conventional

methods with which we ccmmunicate. See R 62-67.2

Four psychiatrists evaluated Mr. Ford's competency during November and

December, 1983: Dr. Harold Kaufman and the three psychiatrists appointed by

the governor pursuant to Fla. Stat. §922.07 (Drs. Peter Ivory, Umesh Mhatre,

and Walter Afield) . Dr. Kaufman, Dr. Mhatre, and Dr. Afield determined that

Mr. Ford suffered from psychosis. (R 432-35, 441-43, 445). Dr. Kaufman

further concluded that Mr. Ford's psychosis was of such severity "that he

cannot sufficiently appreciate or understand either the reasons 'why the death

penalty was imposed upon him' or 'the purpose' of this punishment." (R 435).

Dr. Mhatre and Dr. Afield concluded that Mr. Ford was competent despite having

found that he genuinely suffered from psychosis.2

2 The second of these interviews, on December 19, was the interview conducted by

the psychiatrists appointed by Governor Graham pursuant to Fla. Stat. §922.07.

2 Thus, only the third psychiatrist appointed by Governor Graham, Dr. Ivory,

found Mr. Ford to be suffering from no genuine illness. As to the genuineness

of Mr. Ford's illness, however, it should be noted that a fifth psychiatrist,

Dr. Jamal Amin, also evaluated Mr. Ford. Dr. Amin evaluated Mr. Ford periodi

cally during the course of his deterioration, from before December, 1981

through June, 1983. Dr. Amin concluded that Mr. Ford had developed a profound

-8-

There were substantial reasons proffered to the district court why the

opinions of the psychiatrists who disagreed with Dr. Kaufman's assessment of

competency were wrong. In preparation for the hearing which counsel for Mr.

Ford anticipated in the state trial court, counsel asked two forensic psychia

trists, Dr. Seymour Halleck and Dr. George Barnard, both of whom are widely

recognized as highly competent expert^ within their field, to review the

process by which the three psychiatrists who found Mr. Ford competent undertook

their evaluation. In the opinion of these experts, the evaluations conducted by

the three appointed psychiatrists failed to measure up to the adequate minimum

standards for forensic evaluation. The reasons for this were the appointed

psychiatrists' failure to consider much of the available data concerning Mr.

Ford's mental status (evidenced by their failure to document the factual basis

for their conclusions in the face of pervasive data supporting the contrary

conclusion of Dr. Kaufman) and the great likelihood that the conditions under

which Mr. Ford was evaluated would produce insufficient data for reliable

forensic evaluation. See R 447-53, 465-69.

Even with the serious inadequacy of the appointed psychiatrists' evalua

tions of competency, two of the three nevertheless found that Mr. Ford suffered

from a psychotic illness. And even more telling was the observation of one of

these psychiatrists, Dr. Mhatre, that "without [appropriate anti-psychotic]

medication [Mr. Ford] is likely to deteriorate further and may soon reach a

point where he may not be competent for execution" (R 442) , for in the months

after Dr. Mhatre's observation, his prediction of further deterioration was

strikingly confirmed.

On May 23, 1984, Dr. Kaufman attempted to interview Mr. Ford for two hours

at Florida State Prison. He observed the following:

form of schizophrenia during this time and documented why Mr. Ford's illness

was genuine (R 424-26). Dr. Amin was not able to render an opinion concerning

Mr. Ford's competency after June, 1983, however, because Mr. Ford refused to be

interviewed thereafter by Dr. Amin.

-9-

[Mr. Ford] appeared to have lost at least twenty (20) pounds

since I had last examined him on November 3, 1983. He was

neatly dressed and was wearing rubber shower sandals. He did

not greet the four of us as we entered and sat down. He sat

with his body immobile and his handcuffed hands in a prayer

ful position in front of his mouth. Occasionally he moved

his hands, still in the praying mode, to each of us for no

apparent reason. His lips were pursed intermittently, but his

head moved little. His eyes were closed or fluttering most of

the time, although he occasionally glanced at one or more of

us. His hands and fingers appeared to be trembling. We took

turns asking him questions, and little or no response was

forthcoming. He began muttering to himself after about five

minutes. These utterances were largely unintelligible. This

is the overall picture of what took place for two hours.

(R 487). These observations led Dr. Kaufman to conclude that "Mr. Ford's

condition, severe paranoid schizophrenia, has seriously worsened, so that he

now has only minimal contact with the events of the external world," and to

reconfirm his opinion that Mr. Ford was incompetent to be executed (R 488).

These then were the facts — of Mr. Ford's irrational behavior and of

medical opinion concerning his competency — that were proffered in the

district court on May 29, 1984, in response to which no evidentiary hearing was

held to determine Mr. Ford's competency.

C. Standard of Review

Each of Mr. Ford's federal claims requires the Court to interpret or apply

federal statutory provisions governing habeas corpus procedures, particularly

the principles of Townsend v. Sain, 372 U.S. 293, 313 (1963) governing the

requirement for a federal evidentiary hearing, and/or to reassess independently

the application of federal constitutional principles to record facts.

SUMMARY OF THE ARGUMENT

1. The question of whether the eighth amendment precludes the execution

of an incompetent person has never been reached on the merits by any court.

Because since as early as the twelfth century the execution of the insane has

been repudiated as "savage" and as an act of "extreme inhumanity and cruelty,"

E. Coke, Third Institute 6 (1644), it was a deeply embedded moral principle of

-10-

our enlightened society at the time of the formation of our new Republic. The

Framers of the Sill of Rights were familiar with the English common law and

sought to secure by the Bill of Rights at least all of the rights of English

common law. See Solem v. Helm, ___ U.S.___ , 103 S.Ct. 3001, 3007 & n. 109

(1983). The execution of the insane, seen as a cruel and inhuman sanction, was

thus encompassed by the original intent of the Framers in prohibiting the

infliction of cruel and unusual punishment. In addition contemporary eighth

amendment analysis examines first the objective indicia of contemporary values

and second applies the Court's own independent judicial assessment of the

sanction to determine whether it comports with the basic concept of human

dignity. E.g., Gregg v. Georgia, 428 U.S. 153, 173 (1976). Under this test

too, the execution of the insane violates the eighth amendment. The objective

indicators of public attitudes toward execution of the insane reveal uniform

rejection, for "[t]he law in all American state jurisdictions, as well as

ancient common law, does not permit the execution of a person who is presently

insane." Gray v. Lucas, 710 F.2d 1048, 1053 (5th Cir. 1983). Moreover, this

Court's independent assessment will lead it to conclude that execution of the

insane conflicts with civilized standards of our enlightened society. Thus,

execution of the insane violates the eighth amendment.

2. Since the eighth amendment precludes the execution of a presently

incompetent person, the federal courts must determine independently the

constitutional issue. Moreover, a hearing is mandated in the district court to

determine the factual question of whether Mr. Ford is insane, because the

Florida state determination of that question was nonjudicial, hence entitled to

no deference under 28 U.S.C. §2254, and was procedurally defective and unreli

able in addition. The Florida executive proceeding is entirely ex parte and

the present governor has a "publicly announced policy of excluding all advocacy

on the part of the condemned" in the executive's determination of competency to

-11-

be executed. Goode v. Wainwright, 448 So.2d 999, 1001 (Fla. 1984). There is no

hearing, judicial or otherwise, no examination of witnesses, no written

findings, no judicial review. In short, the Florida gubernatorial proceeding

is entitled to no deference in the federal courts for it is wholly insufficient

to vindicate such a fundamental constitutional right. See Tbwnsend v. Sain,

372 U.S. 293, 313 (1963). There are material facts in serious dispute in this

case that require resolution for determination of the federal question of Mr.

Ford's present incompetency. Accordingly, the eighth amendment question may be

resolved only after a full and fair evidentiary hearing in the district court.

3. Apart from the substantive eighth amendment prohibition against

executing the insane, the procedural due process protections of the fourteenth

amendment require a procedurally fair determination of competency to be

executed. The resolution of the due process question is not controlled by

Solesbee v. Balkcom, 339 U.S. 9 (1950). Solesbee was decided at a time when

constitutional due process analysis still turned on the right-privilege

distinction, when capital sentencing proceedings were generally held to be

beyond the reach of the due process clause, and well before the eighth

amendment imperatives of post-Furman capital jurisprudence had been articu

lated, much less applied through the due process clause to require enhanced due

process protection in death penalty cases. Solesbee was thus the distinct

product of its constitutional era, and its reasoning has been so eroded by

subsequent decisions that it can no longer be relied upon to resolve the

procedural due process issue created by Florida's exclusive reliance on section

922.07. Once Solesbee is analyzed in its proper perspective, the application

of current procedural due process principles compels the conclusion that Mr.

Ford's state—created right not to be executed when incompetent cannot be

withdrawn without substantially greater procedural protections than are

afforded by the ex parte executive procedure provided by section 922.07.

-12-

4. Petitioner's second claim for relief is that Florida administers the

death penalty arbitrarily and discriminatorily on the basis of race of the

victim, race of the defendant and other impermissible factors in violation of

the eighth and fourteenth amendments. Inasmuch as the legal standards govern

ing this claim have not yet been determined and are presently under considera

tion by the en banc court, Mr. Ford's claim cannot be determined until the

resolution of those _en banc decisions. See Spencer v. Zant, 715 F.2d 1562

(11th Cir. 1983), vacated for rehearing en banc, 715 F.2d 1583 (11th Cir.

1983); McCleskey v. Zant, No 84-8176 (pending). The issue has not been

foreclosed by the opinion of Justice Powell concurring in the order of the

Court denying the application to vacate the stay of execution, Wainwright v.

Ford, 104 S.Ct. at 3498, since it was not a ruling on the merits nor could it

have been since the legal standards for evaluating evidence of discriminatory

application of the death penalty have not yet been established by this Court.

STATEMENT OF JURISDICTION

This appeal is taken from an order and judgment entered on May 29, 1984 in

the United States District Court for the Southern District of Florida. This

Court granted a certificate of probable cause on May 30, 1984. Jurisdiction of

the Court lies pursuant to 28 U.S.C. §2253.

ARGUMENT

I. THE EIGHTH AMENDMENT PRECLUDES THE EXECUTION OF THE PRESENTLY

INCOMPETENT.

A. Introduction

While the execution of an incompetent person has been repudiated as

"savage” and "cruel" since perhaps as early as the twelfth century, no court

has addressed the issue under the eighth amendment. The Supreme Court has had

four occasions to address the question of execution of the incompetent, but in

none of these decisions did it reach the eighth amendment issue presented here.

Significantly, all of those decisions were before the incorporation of the

eighth amendment into the due process clause in Robinson v. California, 370

U.S. 660 (1962).4 In the present case, in declining to vacate the stay entered

by this Court, four Justices recognized that: "This Court has never determined

whether the Constitution prohibits execution of a criminal defendant who

currently is insane, ..." Wainwright v. Ford, 104 S.Ct. at 3498 n.*. In

Goode v. Wainwright, 731 F.2d 1482 (11th Cir. 1984) this Court did not reach

the substantive eighth amendment claim because it found an "abuse of the writ.

Id. at 1483. (citing Woodard v. Hutchins, ___U.S.___, 104 S.Ct. 752 (1984)

(order vacating stay of execution)). And the fifth circuit assumed without

deciding that the eighth and fourteenth amendments would not permit execution

of an insane person in Gray v. Lucas, 710 F.2d 1048 (5th Cir. 1983).

The issue is thus one of first impression. In the sections below, it will

be shown that the eighth amendment precludes the execution of the presently

incompetent both under an analysis of the original intent of the Framers of the

Bill of Rights and under contemporary eighth amendment jurisprudence.

B. Intent of the Framers

Here, we will examine the history of the prohibition against executing the

insane for it bears upon and guides the analysis of the intent of the Framers

of the Bill of Rights5 and we will then look to the adoption of the eighth

4 see Nobles v. Georgia, 168 U.S. 398 (1897) (no right to jury for determining

competency to be executed); Phyle v . Duffy, 334 U.S. 431 (1948) (avoided due

process question because state judicial remedy still available); Solesbee v.

Balkcom, 339 U.S. 9 (1950) (reaching due process question but specifically not

deciding eighth amendment question); Caritativo v. California, 357 U.S. 549

(1958) (one sentence opinion citing Solesbee, with four justices separately

opining that the due process clause prohibited execution of the presently

incompetent).

5 Ihe Court has frequently examined the common law in determining the intent of

the Framers and whether a particular right is to be included within those

guaranteed by the Bill of Rights. See, e.g., Duncan v. Louisiana, 391 U.S. 145,

151-53 (1968) (tracing the history of jury trials through the common law to the

colonies and original states and concluding that "[e]ven this skeletal history

is impressive support for considering the right to trial by jury in criminal

cases to be fundamental to our system of justice, an importance frequently

recognized in the opinions of this Court"); Williams v. Florida, 399 U.S. 78,

87-94 (1970) (tracing common law history but finding no support that a 12-

-14-

amendment to show that execution of the insane falls within the original intent

of the prohibition against "cruel and unusual punishments."

1. A "Savage" Act of "Extreme Inhumanity and Cruelty"

The prohibition against the execution of the insane dates at least frcxn

the thirteenth or early fourteenth centuries when proof of madness required the

grant of a royal pardon:

[I]n very ancient times proof of madness appears not to have

entitled a man to be acquitted, at least in case of murder,

but to a special verdict that he committed the offence when

mad. This gave him a right to a pardon.

2 J. Stephen, A History of the Criminal Law of England 151 (1883) (emphasis

added) .* 6 * See also FitzHerbert, Natura Brevium 202 (1534) (quoted in Sayre,

Mens Rea, 45 Harv. L. Rev. 974 (1931-32)).

So settled by the 16th century was the principle that a "madman" must be

reprieved from execution that in order to exempt one guilty of high treason

from its proscription "in the bloody reign of Henry VIII, a statute was made,

which enacted that if a person, being compos mentis, should commit high

treason, and after fall into madness, he might be tried in his absence, and

should suffer death as if he were of perfect memory." 4 W. Blackstone,

Commentaries on the Laws of England 24 (1768) (hereinafter cited as

Blackstone). Because the execution of the insane "was always thought cruel

person jury was constitutionally required); Hurtado v. California, 110 U.S. 516

(1884) (no right to grand jury indictment).

6 In a footnote to this paragraph Stephen cites to the written laws of Edward II

(1310) and Edward 111(1330). See also Hunard, The King's Pardon for Homicide

Before A.D. 1307 159 (1969) (tracing the early treatment of insanity prior to

Edward II); S. Glueck, Mental Disorder and the Criminal Law 124-25 (1925)

(briefly summarizing the treatment of insanity in the reigns of Edward I

(1272-1307), Edward II (1307-1321) and Edward III (1326-1327)).

-15-

and inhuman,"7 even this narrow exception to the established rule "lived not

long"8 9 for as Blackstone notes "this savage and inhuman law was repealed by the

statute of 1 and 2 Ph. and M. c.10." Blackstone at 24. See also 1 M. Hale, The

History of the Pleas of the Crown 35 (1736).8

The prohibit ion - as "savage," "cruel," "inhuman," and "inhumane" of

execution of the insane was thus firmly established. It was recognized by Lord

Coke in 1644, in commenting upon and approving the repeal of Henry VIII's law,

that "it was against the common law" and "should be a miserable spectacle, both

against law, and of extreme inhumanity and cruelty, and can be no example to

others." E. Coke, Third Institute 6 (1644). Matthew Hale explained that one

charged with a capital offense "even tho the delinquent in his sound mind were

examined, and confessed the offense" could not be executed "if after judgment

he became of non sane memory, ... for were he of sound memory, he might allege

somewhat in stay of judgment of execution." 1 M. Hale, The History of the

Pleas of the Crown 35 (1736). See also 1 W. Hawkins, A Treatise of the Pleas

of the Crown 2 (1716) ("And it seems agreed at this Day, That if one who has

committed a capital Offence, become Non Compos before Conviction, he shall not

7 1 J. Chitty, A Practical Treatise on the Criminal Law 620 (Philadelphia ed.

1819). The exeception was apparently made "in Respect of that high Regard which

the Law has for the Safety of the King's Person". I W. Hawkins, A Treatise of

the Pleas of the Crown 2 (1716).

8 Hawles, Remarks on the Trial of Mr. Charles Bateman, 11 State Trials 474, 477

(1816) (recognizing the law of Henry VIII to be "a cruel and inhumane law").

9 It is of more than passing interest in evaluating the depth of the belief that

execution of the insane was cruel and inhumane, that the narrow high treason

exception was repealed during the reign of Phillip and Mary. Mary was Mary I,

who is known as "Bloody Mary." She ruled from 1553 to 1558 and during her

reign she procured "ferocious new treason laws," G.R. Elton, England Under the

Tudors 219 (1960), punishible by "such pains of death" as befits treason, stat.

I, c.6. See Blackstone at 376-77 (detailing such pains of death: "being drawn

or dragged to the place of execution . . . oribowelling alive, beheading, and

quartering). It can thus be safely said that Mary's repeal of the "cruel and

inhuman law" of Henry VIII was not motivated by some extreme, misguided

benevolence.

be executed"). Blackstone reaffirmed the settled nature of the principle in

1775:

If a man in his sound memory commits a capital offense, ...

and if, after judgment, he becomes of nonsane memory,

execution shall be stayed: for peradventure, says the

humanity of English law, had the prisoner been of sound

memory, he might have alleged something in stay of judgment

or execution.

Blackstone at 24-25.

Various reasons had been put forth by the scholars to explain the settled

prohibition. Sir Edward Coke observed that execution of the insane could "be

no example to others." Sir John Hawles disagreed, "the true reason of the law

I think to be this, a person of 'non Sana memoria,' and a lunatick during his

lunacy, is by an act of God (for so it is called, though, the means may be

human, be it violent, as hard imprisonment, terror of death or natural as

sickness) disabled to make his just defence." Hawles, 11 State Trials at 476.

Blackstone added the further rationale that "a madman is punished by his

madness alone."10 Hawles added still another reason: an insane person is

deprived of the opportunity to make peace with his God:

it is inconsistent with religion, as being against Christian

charity to send a great offender quick, as it is stiled, into

another world, when he is not of a capacity to fit himself

for it.

Hawles, 11 State Trials at 477.

These then were the explanations advanced by the common law writers. As

Lord Hawles observed, however, "whatever the reason of the law is, it is plain

the law is so." Id. See generally 1 J. Archbold, A Complete Practical Treatise

on Criminal Procedure 22-23 (8th ed. 1879) (summarizing the rule and its common

law reasons).

Even though the right not to be executed while insane was so entrenched in

10 Blackstone expressed the rationale in its Latin formulation: furiosus solo

furore punitur." Blackstone at 395-96.

common law, some have still referred to it as falling within the perogative of

the Crown as an act of grace. This, however, would be a misreading of common

law history. Though as a technical matter, one who was insane was excused from

execution only by a "reprieve," it was not a matter of grace but a matter of

right. As Blackstone explains, there were twa types of reprieves, the first

was the "arbitrary reprieve" ("ex arbitria judicis") which could be granted, as

its name implies, for any or no reason. The second type of reprieve was ex

necessitate 1 eg is" which as its name also implies, was mandatory. It is in

this later type of reprieve that the stay of execution for insanity lies. It

was a reprieve as a matter of right — an "invariable rule and could be

raised by the judge or "plead[ed] in bar of execution. Blackstone at 394-97.

2. "Nor Cruel and Unusual Punishments Inflicted"

The Framers of the Bill of Rights were, of course, familiar with the

cannon law for that was the only system they had known: "The cannon law was the

mapped world; to depart therefrom was to venture into the unknown."11 There were

"[f]ive sources from which American colonists gained their understanding of

English law" and among these were Hale's History of the Pleas of the Crown and

volume four of Blackstone's Commentaries on the Laws of England. Granucci,

Cruel and Unusual Punishments Inflicted:" The Original Meaning, 57 Cal. L. Rev.

839, 861 (1969). As discussed in the preceding section, Hale and Blackstone

had each stated the uneguivocal common law prohibition against executing the

insane.

Admittedly, as of ten-times observed, there is little specific history to

reflect the intent of the Framers in adopting the eighth amendment.12 But all

11 R. Berger, Death Penalties 63 (1982).

12 E.g., Furman v. Georgia, 408 U.S. 238, 258 (1972) (Brennan, J., concurring)

("We have very little evidence of the Framers' intent in including the Cruel

and Unusual Punishments Clause among those restraints upon the new Government

enumerated in the Bill of Rights.").

-18-

that is known, including the settled nature of the law at the time, indicates

that execution of the insane would fall within the proscription of "cruel and

unusual punishments" as intended by the Framers.

It is now axiomatic in eighth amendment jurisprudence that "[t]here can be

no doubt that the Declaration of Rights guaranteed at least the liberties and

privileges of Englishmen." Solem v. Helm, ___U.S. ____, 103 S.Ct. 3001, 3007

n. 10 (1983). Thus,

When the Framers of the Eighth Amendment adopted the language

of the English Bill of Rights, . . . . one of the consistent

thanes of the era was that Americans had all of the rights of

English subjects . . . . Thus, our Bill of Rights was

designed in part to ensure that these rights were preserved.

Although the Framers may have intended the Eighth Amendment

to go beyond the scope of its English counterpart, their use

of the language of the English Bill of Rights is convincing

proof that they intended to provide at least the same protec

tion — including the right to be free from excessive

punishments.

Id. at 3007.

Thus, Thomas Cooley, though finding it "certainly difficult to determine

precisely what is meant by cruel and unusual punishments," believed only that

punishments permitted under common law at the time of the adoption of the

amendment would be permitted by the amendment. T. Cooley, A Treatise on the

Constitutional Limitations 472-73 (7th ed. 1903). At the very least "[w]e may

rely on the conditions which existed when the Constitution was adopted." Weens

v. United States, 217 U.S. 349, 30 S.Ct. 544, 552 (1909). Concurring in Furman,

Justice Brennan summarzed the Court's early eighth amendment decisions as

"concluding simply that a punishment would be 'cruel and unusual' if it were

similar to punishments considered 'cruel and unusual' at the time the Bill of

Rights was adopted." Furman v. Georgia, 408 U.S. 238, 264 (1972) (Brennan, J.,

concurring). See also McGautha v. California, 402 U.S. 183, 226 (1971) (Black,

J., concurring) (same).

Even under the most restrictive reading that has been given to the meaning

-19-

of the eighth amendment — that it prohibits only something that is addition

ally inhumane beyond the "mere extinguishment of life"13 — execution of the

insane would be prohibited, for it had been viewed for centuries as being more

barbarous, cruel and inhumane than execution alone. Execution of the insane

was thus plainly believed to be "worse" in terms of human decency than was the

"mere extinguishment of human life."

If all that the eighth amendment was intended to do was to ensure the

prohibition of the punishments then prohibited by English law, then there can

be no doubt that the clause proscribed as "cruel and unusual" the execution of

the insane as it had been proscribed for five hundred years as cruel. It would

require blinders to history to hold otherwise. There is absolutely no indica

tion that the Framers intended to permit more cruelty under its prohibition

than had the English law; one would have to assume that the Framers intended

"American law [to be] more brutal than what is revealed as unbroken command of

English law for centuries preceding the separation of the Colonies." Solesbee

v. Balkcom, 339 U.S. at 20 (Frankfurter, J., dissenting).

This was of course not the intent. That the new Americans continued to

believe in the inhumanity of execution of the insane is shown by early American

commentators. In 1819 Chitty published his American edition of his treatise on

criminal law in which he carried forward the proscription on execution of the

insane, repeating that it "was always thought cruel and inhuman." 1 J. Chitty,

A Practical Treatise on the Criminal Law 620 (Amer. ed. 1819). See also F.

Warton, A Treatise on the Criminal Law of the United States 50 (2d ed. 1852)

("If one who had committed a capital offence become non compos mentis ... after

13 in re Kemmler, 136 U.S. 436, 447 (1890). See also Furman v. Georgia, 408 U.S.

at 378 (Burger, C.J., dissenting) (quoting Kemmler); Gregg v. Georgia, 428 U.S.

at 169-70 (plurality opinion) (recognizing original intent to preclude

"'tourture' and other 'barbarous' methods" beyond execution itself). But see

Weans v. United States, 217 U.S. 349, 30 S.Ct. 544, 551 (1910) ("[I]t must have

come to [the Framers] that there could be exercises of cruelty by laws other

than those which inflicted bodily pain or mutilation.").

conviction, he shall not be executed"); I. Ray, Treatise on the Medical

Jurisprudence o£ Insanity 2 (5th ed. 1871); 1 W. Russell, A Treatise on Crimes

and Indictable Misdemeanors 15 (3d Amer. ed. 1836) ("if after judgment he

becomes of nonsane memory, execution shall be stayed"). In 1836 a legislative

committee of Massachusetts reflected public opinion in commenting on the

prospect of execution of the insane: "the proposition to do so would be

rejected with unanimous indignation, even after he has committed more than one

murder." Massachusetts Committee on Capital Punishment, Report 22 (1836).14 A

more recent historian described the deeply-rooted attitude of the era:

Both humanity and the law assumed, of course, that no truly

insane person should be put to death as punishment for his

criminal acts. Though opposition to capital punishment as

such was comparatively small, only a few self-consciously

ruthless intellectuals even suggested that insane criminals

should suffer the maximum penalty.

Rosenberg, The Trial of the Assassin Guiteau, Psychiatry in the Guilded Age 66

(1968).

All indications therefore conclusively show that the Framers did not

intend to regress from the centuries-old common law.

3 . Conclusion: The Framers Intended to Prohibit Cruel Punishments and

Execution of the Insane was Known by the Framers to be Cruel and

Inhuman

As recognized by the Royal Commission on Capital Punishment: "It has for

centuries been a principle of the common law that no person who is insane

should be executed___ " Royal Commission on Capital Punishment, 1949-1953

Report 13 (1953). This is such a deeply embedded principle that it cannot be

subject to question. See also Note, The Eighth Amendment and the Execution of

the Presently Incompetent, 32 Stan. L. Rev. 765, 778 (1980) ("it has been a

14 The Massachusettes1 committee was one of several 19th-century state commissions

investigating the death penalty which all endorsed the same view regarding the

unthinkability of execution of the incompetent. See Note, The Eighth Amendment

and the Execution of the Presently Incompetent, 32 Stan. L. Rev. 765, 779 &

n.67 (1980).

-21-

cardinal principle of Anglo-America jurisprudence since the medieval period

that the presently incompetent should not be executed").

Could it be said that a mode of punishment thought to be savage, inhumane

and extremely cruel by all courts and commentators at the time of the framing

of the Bill of Rights would not be likewise deemed cruel by the Framers of the

eighth amendment? Likewise, could it be said that a punishment disapproved by a

settled rule for hundreds of years would not be thought to be "unusual" by the

Framers?!^ The Framers sought at a minimum to secure the common standards of

decency then in effect and did not seek regression from those standards.

Execution of the insane was considered cruel at the time of the adoption of the

eighth amendment and thus fails under the proscription of cruel punishments

originally intended by the Framers.

C. Traditional Eighth Amendment Jurisprudence

Just as strongly as does the intent of the Framers, the traditional eighth

amendment analysis demonstrates that execution of the insane contravenes the

eighth amendment. To evaluate the eighth amendment propriety of an aspect of

the death penalty, the Court has adopted a two-part test based upon the

proposition that the amendment must draw its meaning from the "evolving

standards of decency that mark the progress of maturing society." Gregg v.

Georgia, 428 U.S. 153, 173 (1976) (quoting, Trop v. Dulles, 356 U.S. at 101).

The first part of the test focuses on "contemporary standards of decency" and

uses "objective indicia" such as historical usage and legislative enactments,

to ascertain the public perceptions toward a given sanction. Gregg v. Georgia,

428 U.S. at 173. Second, even if the sanction is found by objective evidence to

be "acceptable to contemporary society," the eighth amendment demands that 15

15 See, e.g. , Trop v. Dulles, 356 U.S. 86, 100 n. 32 (1958) ("If the word

' unusual' is to have any meaning apart from the word 'cruel,' however, the

meaning should be the ordinary one, signifying something different from that

which is generally done"); Furman v, Georgia, 408 U.S. at 309 (Stewart, J.,

concuring).

" [ t] he Court also must ask whether it comparts with the basic concept of human

dignity at the core of the Amendment." _Id. at 1 8 2 . ^ 6 Execution of the insane

fails on both counts.

1. Contemporary Standards of Decency: Uniform Disapproval

Evaluation of "contemporary" standards of decency is uniquely facile in

this case, for the standards have remained constant for the greater part of the