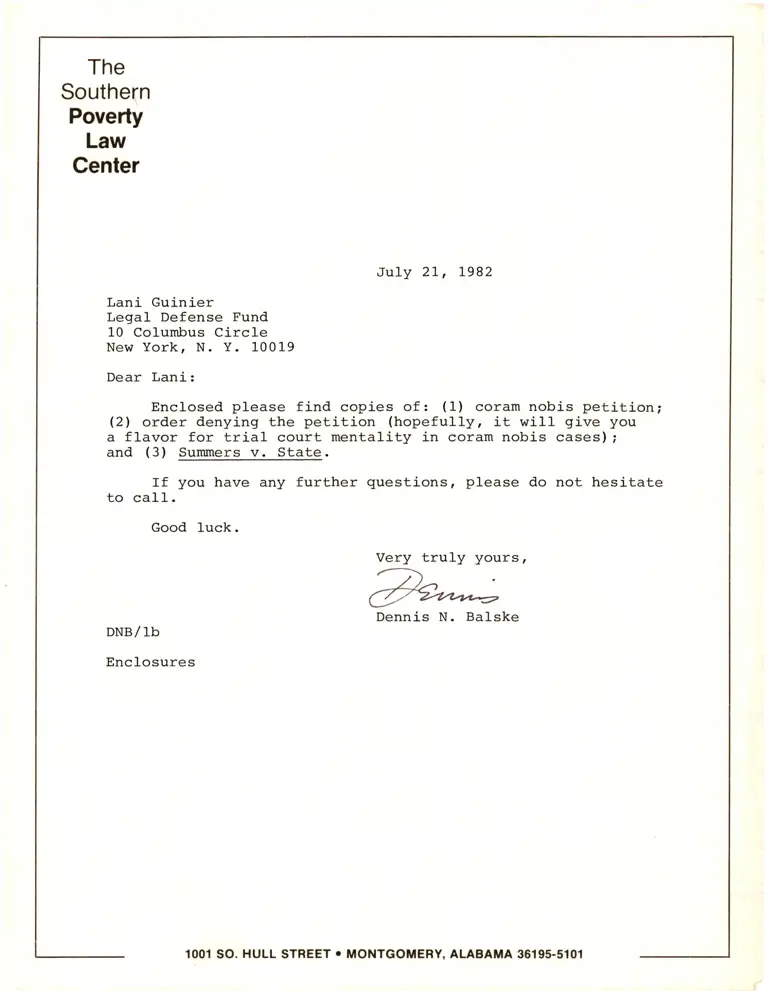

Correspondence from Balske to Guinier

Correspondence

July 21, 1982

Cite this item

-

Case Files, Bozeman & Wilder Working Files. Correspondence from Balske to Guinier, 1982. 37b8e2e0-ee92-ee11-be37-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/372ee6d3-11f0-4e60-8ab4-794c8ba40d21/correspondence-from-balske-to-guinier. Accessed February 20, 2026.

Copied!

The

Southern

Poverty

Law

Center

July 2L, L982

Lani Guinier

Legal Defense Fund

10 Columbus Circ1e

New York, N. Y. 10019

Dear Lani:

Enclosed please find copies of: (1) coram nobis petition;

(21 order denying the petition (hopeful1y, it will give you

a flavor for trial court mentality in coram nobis cases);

and (3) Summers v. State.

If you have any further questions, please do not hesitate

to ca1I.

Good Iuck.

Very truly yours,

Dennis N. Balske

DNB/1b

Enclosures

. HULL AETo1OO1 SO. HULL STRE MONTGOMERY, ALABAMA 361 95.51 01