Allen v. State Board of Elections Response of Appellees to the Memorandum for the United States

Public Court Documents

May 3, 1968

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Allen v. State Board of Elections Response of Appellees to the Memorandum for the United States, 1968. 18e24792-b79a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/37304624-adf4-4fc5-a327-6c5b41aa790f/allen-v-state-board-of-elections-response-of-appellees-to-the-memorandum-for-the-united-states. Accessed February 22, 2026.

Copied!

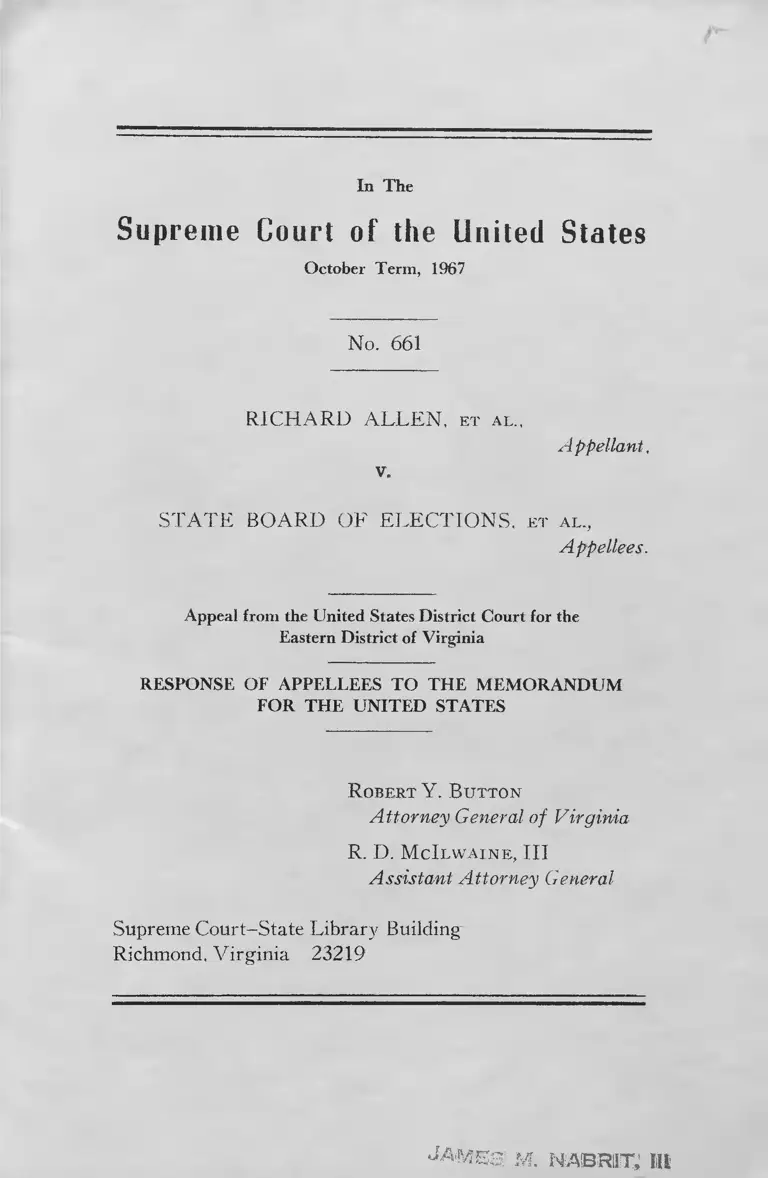

In The

Supreme Court of the United States

October Term, 1967

No. 661

RICHARD ALLEN, et a l„

v.

Appellant,

STATE BOARD OF ELECTIONS, et a l .

Appellees.

Appeal from the United States District Court for the

Eastern District of Virginia

RESPONSE OF APPELLEES TO THE MEMORANDUM

FOR THE UNITED STATES

R obert Y. B u tto n

Attorney General of Virginia

R. D. M cI l w a in e , III

Assistant Attorney General

Supreme Court-State Library Building

Richmond, Virginia 23219

JAMES m. nabrot; hi

In The

Supreme Court of the United States

October Terra, 1967

No. 661

RICHARD ALLEN, et a l .,

Appellant,

v.

STATE BOARD OF ELECTIONS, et a l .,

Appellees.

Appeal from the United States District Court for the

Eastern District of Virginia

RESPONSE OF APPELLEES TO THE MEMORANDUM

FOR THE UNITED STATES

On February 14, 1968, the Solicitor General filed a

memorandum expressing the views of the United States in

the case at bar. The following day counsel for the parties

were informed by letter of the Clerk of this Court that

they would be permitted to file supplemental briefs on or

before March 5, 1968. In accordance with the leave thus

granted, this response of the appellees to the memorandum

of the United States is filed.

As previously pointed out by appellees in their motion

to affirm the judgment of the District Court, the Virginia

State Board of Elections issued certain instructions to

2

election officials throughout the State on August 12, 1965

and October 15, 1965. The first instructions were promul

gated within a week of the effective date (August 6, 1965)

of the Voting Rights Act of 1965, and the second instruc

tions were issued some three weeks before the first general

election held in Virginia after the effective date of the

Voting Rights Act. In effect, these instructions advised

Virginia election officials (1) that the Voting Rights Act

of 1965 had become effective in Virginia on August 6, 1965,

and was “now in force in Virginia” and (2) that under the

provisions of the Federal law, they were required to render

assistance to educationally handicapped citizens who were

unable to register or to vote because of a lack of literacy

or otherwise. Emphasis supplied. See, Statement of Ap

pellees Opposing Jurisdiction and Motion to Affirm, pp. 4-5.

Essentially, the instructions in question advised such election

officials that various provisions of Virginia law governing

registration and voting had already been suspended by the

Voting Rights Act and that they were immediately re

quired to render assistance to prospective voters who were

educationally handicapped.

The Solicitor General asserts that instructions of this

character, particularly those issued on October 15, 1965,

constitute a “practice, or procedure with respect to voting

different from that in force or effect on November 1,

1964” within the meaning of Section 5 of the Voting Rights

Act, 42 U.S.C. 1973c, and states that it “would appear to

follow that the new requirement could not be used without

first passing the scrutiny of either the Attorney General or

the United States District Court for the District of Colum

bia.” See, Memorandum for the United States, pp. 6-7. The

latter statement is referable to that portion of Section 5

of the Voting Rights Act which suspends the efficacy of

any State voting regulation promulgated after November 1,

3

1964, unless there has been (1) submission of the rule to

the Attorney General, in which case it may be used if no

objection is interposed within sixty days; or (2) a declara

tory judgment from the United States District Court for

the District of Columbia that the rule “does not have the

purpose and will not have the effect of denying or abridging

the right to vote on account of race or color . . See, Memo

randum for the United States, p. 6.

Counsel for appellees submit that the invalidity of the

Solicitor General’s position is easily demonstrable. If the

instructions issued in the case at bar were subject to the

provisions of Section 5 of the Voting Rights Act, it

necessarily follows that a State to which the Act applies

could not adjust its procedures to comply with the require

ments of the Federal law until they received permission

to do so from the Attorney General or the District Court

for the District of Columbia. The Solicitor General’s as

sertion overlooks the fact that the instructions under con

sideration were not promulgated to alter Virginia law as

such, but were required to implement the Voting Rights

Act which became effective on August 6, 1965. The So

licitor General’s contention impels the conclusion that the

Voting Rights Act, which became law on August 6, 1965,

could not be made effective in practice without the prior

consent of the Attorney General or the District Court.

Such a conclusion is tantamount to the proposition that

the Voting Rights Act could be suspended until the Attorney

General or the District Court approved of a State’s instruc

tions complying with the Act. Counsel for appellees submit

that there is nothing in the Federal statute which even

remotely evidences an intention on the part of the Congress

to delay the effectiveness of the Voting Rights Act until

such permission is first obtained.

4

No one can say how many illiterate voters were registered

pursuant to the instructions of the State Board of Elections

within the first sixty days of the enactment of the Voting

Rights Act—persons who could not properly have been

registered during this period if the position of the Solicitor

General is sound. Similarly, there is no way to ascertain

how many illiterate voters were assisted in casting their

ballots at the general election in November of 1965, pur

suant to the instructions in question—voters who could not

have been thus assisted had it been necessary to await the

expiration of a sixty-day period following issuance of the

instruction on October 15, 1965.

Moreover, the Solicitor General suggests that the Court

remand this case to the District Court with instructions “to

grant such relief as is necessary to guarantee that Virginia

will refrain from imposing restrictions upon the manner

of casting write-in votes pending compliance” with the re

quirements of Section 5. This suggestion is obviously an

attempt to convert the instant case into litigation of the

character instituted by the United States in Alabama,

Louisiana, Mississippi and South Carolina, as mentioned in

the Solicitor General’s memorandum. See, Memorandum for

the United States, p. 6, fn. 3. Such a suggestion surely

undertakes to obscure the fact that no case warranting

equitable relief has been made out in the instant litigation.

As the District Court pointed out on two separate occasions

in its opinion, no evidence was presented that Virginia’s

prohibition of stickers or pasters had been administered in

a discriminatory manner and no evidence was offered that

any judge of election denied any illiterate voter the con

fidential assistance to which he was entitled. See, Jurisdic

tional Statement, Appendix, pp. 5a-7a. Indeed, even the

Solicitor General admits that Virginia’s procedure for cast-

s

mg write-in votes by illiterates, on its face, has no purpose

forbidden by the Voting Rights Act and that the Attorney

General does not now have evidence that such a purpose

existed. See, Memorandum for the United States, pp. 7-8.

Thus, the suggestion that the case be remanded to the

District Court is manifestly an effort to subject to the

jurisdiction of a Federal court Virginia election officials

against whom no suggestion of impropriety has been made.

The only relief sought by plaintiffs in the case at bar is

that they be permitted to vote by means of stickers or past

ers. As the District Court held, neither the plaintiffs nor any

other Virginia citizen is accorded that right, either by the

Fourteenth Amendment or by the Voting Rights Act of

1965. The instant case is not now—and never was—a suit to

obtain relief from alleged discriminatory registration or

voting practices of Virginia election officials, and counsel

for appellees submit that the Solicitor General cannot now

convert it into such a suit at the ultimate level of appellate

review.

For the foregoing reasons, counsel for appellees submit

that the judgment of the District Court should be affirmed.

Respectfully submitted,

R obert Y. B u tto n

Attorney General of Virginia

R. D. M cI l w a in e , III

Assistant Attorney General

Supreme Court-State Library Building

Richmond, Virginia 23219

6

CERTIFICATE OF SERVICE

I, R. D. Mcllwaine, III, an Assistant Attorney General

of Virginia, a member of the Bar of the Supreme Court

of the United States and one of the counsel for appellees

in the above-captioned matter, hereby certify that copies

of this Response of Appellees to the Motion for the United

States have been served upon each of counsel of record for

the parties herein by depositing the same in the United

States Post Office, with first-class postage prepaid, this 5th

day of March, 1968, pursuant to the provisions of Rule

33(1) of the Rules of the Supreme Court of the United

States, as follows: Jack Greenberg, Esq., and James M.

Nabrit, III, Esq., 10 Columbus Circle, New York, New

York 10019, and Oliver W. Hill, Esq., S. W. Tucker,

Esq., Henry L. Marsh, III, Esq., and Harold M. Marsh,

Esq., 214 East Clay Street, Richmond, Virginia 23219,

counsel for appellants.

Assistant Attorney General