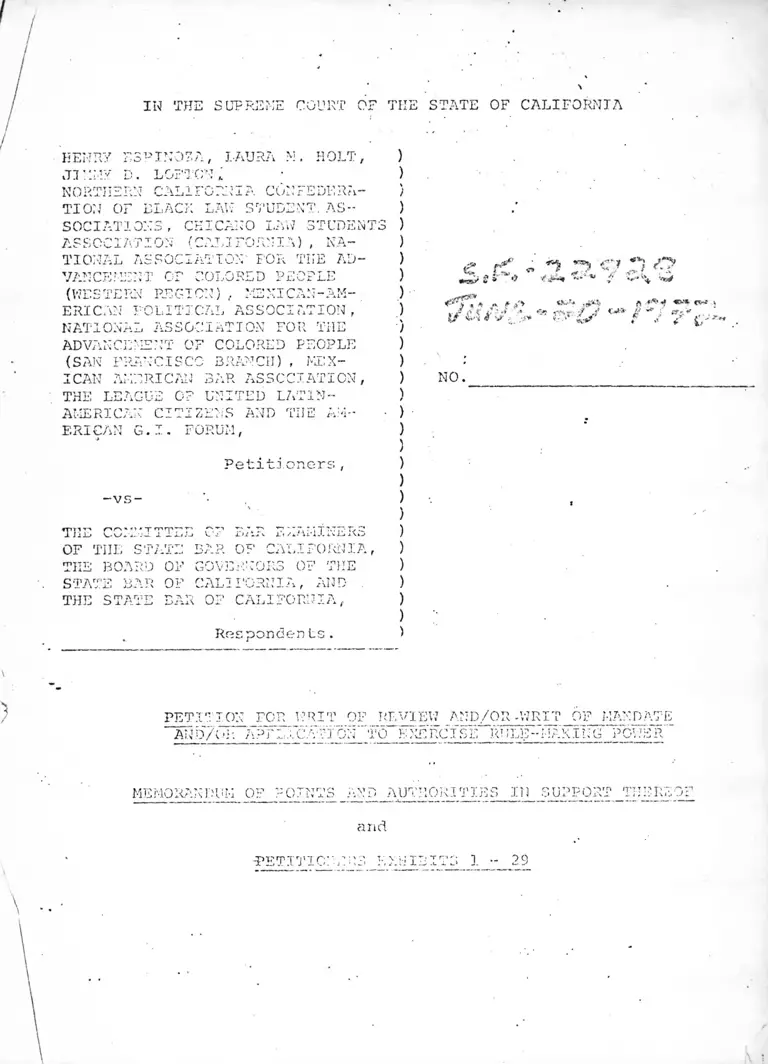

Espinoza v. California State Bar Committee of Examiners Memorandum of Points and Authorities Un Support Thereof and Petitioners Exhibits

Public Court Documents

June 20, 1972

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Espinoza v. California State Bar Committee of Examiners Memorandum of Points and Authorities Un Support Thereof and Petitioners Exhibits, 1972. aa016a0b-b19a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/373f0065-7df9-485a-b066-7ec9ef11881e/espinoza-v-california-state-bar-committee-of-examiners-memorandum-of-points-and-authorities-un-support-thereof-and-petitioners-exhibits. Accessed February 24, 2026.

Copied!

IN THE SUPREME COURT OF TIIE STATE OF CALIFORNIA

HENRY ESP I NO 7. A , LAURA M. HOLT, )

JIMMY D. LOFTON. * )

NORTHERN CALIFORNIA CONFEDERA- )

TION OF BLACK LAM STUDENT.AS- )

SOCIATIONS , CKICA.NO I.AW STUDENTS )

ASSOCIATION (CALIFORNIA), NA- )

TIONAL ASSOCIATION' FOR THE AD- )

VANCEMENT OF COLORED PEOPLE )

(V7ESTERN REGION) , MEXICAN-AM- )

ERIC AN POLITICAL ASSOCIATION, .)

NATIONAL ASSOCIATION FOR THE )

ADVANCEMENT OF COLORED PEOPLE )

(SAN FRANCISCO BRANCH), KEX- )

I CAN AMERICAN BAR .ASSOCIATION , )

THE LEAGUE 0? UNITED LZvTIU- )

AMERICAN* CITIZENS AND THE AM- • )

ERICAN G.I. FORUM, )

)

Petitioners , )

)

-vs- '■ )

)

THE CO.T-.'I j. Ti.iĵ v_ )

OF THE STATE BAR OF CALIFORNIA, )

THE BOARD OF GOVERNORS OF THE )

STATE BAR OF CALIFORNIA, AND . )

THE STATE BAR OF CALIFORNIA, )

)

Respondents. )

^ a T?G.’ v 4 w

*

17 r

NO.

PETITION FOR V-7.RIT OF REVIEW AND/OR -WRIT OF MANDATE

a n d/oi. ;>pri.-:lc7v?i~6n'"Fo pulercY se rtils-~hakxTig~p o v z r '

MEMORANDUM OF POINTS AND AUTHORITIES IN SUPPORT THEREOF

and

-PETITIONERS KN.WI* ]. 29

2

3

4

5

1 ROBERT L. GNAI 2 DA, ESQ.

SIDNEY M . NOLINSKY , ESQ.

albert Tn MORENO, ESQ .

J. ANTITONY' KLINS , ESQ.

JO ANN CHI.HOLER, ESQ.

Public Advocates; Inc:

433 Turk Street

San Francisco, California 94102

Tel: (415) 441-8850

ALAN EXELROD, ESQ.

MICHAEL MENDELSON, ESQ.

Mexican-American Legal

Defense and Educational Fund

National Office

145 - 9th Street

San Francisco, California 94102

Tel: (415) 626-6196

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17-

18

19

20

21

22

*>*> .J

TERRY J. HATTER, JR., ESQ.

ABBY SOVEN, ESQ.

HAROLD HART-NI33RIG, ESQ.

LORETTA SIFUENTES, ESQ.

Western Center on Lav: & Poverty

1709 West 0th Street

Los Angeles, California 90017'

Tel: (213) 483-1491

MARTY CLICK, ESQ. .

CRUfc REYNOSO, ESQ.

MIGUEL MENDEZ, ESQ. •

California Rural Legal Assistance

1212 Market Street

San Francisco, California 94102

Tel: (415) 853-4911

STAN LEVY, ESQ.

STANLEY W. KELLER, ESQ.

Beverly Hills Bar Association

Lav; Foundation

300 South Beverly Drive

Beverly Hills, California 90212

Tel: (213) 553-6644

Attorneys for

CHARLES JONES, ESQ..

Los Angeles Legal Aid

Foundation

1819 West Sixth Street

Los Angeles, California 90017

Tel: (213) 484-9350

ELLEN CUMMINGS, ESQ.

Legal Aid Society of Alameda

County

2357 San Pablo Avenue

Oak1and, California 9 4 612

Tel: (415) 465-3833

Petitioners

Of Counsel:

Mario Obledo

i

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

DECLARATION OF SERVICE BY MAIL

I, WILLIAM II. HASTIE, JR.-, certify under penalty of

perjury that on this 20th day of June, 1972/ I deposited in the

United States post office at San Francisco, a true and correct

copy of the instant Petitions with Memorandum of Points and

Authorities in Support thereof and Appendices with postage pre

paid thereon to the respondents:

State Bar of California (2 Copies)

Committee of Bar Examiners

thereof and the

Board of Governors

thereof

601 McAllister Street

San Francisco, California 94102

Hon. Evelle J. Younger, (1 Copy)

Attorney General

Office of the Attorney General

Federal Court House Building

Sacramento, California 95814

Executed on June 20, 1972, at San Francisco,

California.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

ROBERT L. GNAT 2D A, ESQ.

SIDNEY . : • ■NOLI> T r* T r \y...JE 1, ESQ.

ALBERT F . MORENO, ESQ. '

J. .ANTI--!0:F/ kli t ESQ.

JO ANN CHiAN DLE R, ESO.Public Advocates,' Inc.

433 Turk Street

San Francisco, California 94102

Tel: (415)- 441-8850

TERRY J. HATTER, JR., ESQ.

ABBY 5OVER, ESQ.

HAROLD HART-HIS3RIG, ESQ.

LORETTA SIFLEETES, ESQ.

Western Center on Lav & Poverty

1709 West 8th Street

Los Angeles, California 90017

Tel: (213) 483-1491

IlARfY CLICK, ESQ. .

CRUZ REYNOSO, ESQ.

MIGUEL MENDEZ, ESQ.

California Rural Legal Assistance

1212 Market Street

San Francisco, California 94102

Tel: (415) 363-4911

STAN LEVY, ESQ.

STANLEY W. KELLER, ESQ.

Beverly Hills Bar Association

Lav; Foundation

300 South Beverly Drive ■

Beverly Hills, California 90212

Tel: (213) 553-6644

Attorneys for Petitioners

IN THE SUPREME COURT OF

HENRY ESPINOZA, LAURA H. HOLT, )

JIMMY D. LOFTON )

NORTHERN CALIFORNIA CONFEDERA- )

TION OF BLACK LAW STUDENT AS- )

SOCIATIONS, CHICANO LAW STUDENTS )

ASSOCIATION (CALIFORNIA), NA- )

TIONAL ASSOCIATION FOR THE AD- )

VANCEMENT OF COLORED PEOPLE )

(WESTERN REGION), MEXICAN-AH- )

ERTCAN POLITICAL ASSOCIATION, )

NATIONAL ASSOCIATION FOR.THE )

/ADVANCEMENT OF COLORED PEOPLE. )

(SAN FRANCISCO BRANCH), ' )

ALAN EXELROD, ESQ.

MICHAEL MENDELSON, ESQ.

Mexican-American Legal

Defense and Educational•Fund

National Office

145 - 9th Street

San Francisco, California 94103'

Tel: (415) 626-6196

CHARLES JONES, ESQ.

Los Angeles Legal Aid

Foundation

1819 West Sixth Street

Los Angeles, California 90017

Tel: (213) 484-9550

ELLEN CUMMINGS , ESQ'.

Legal Aid Society of Alameda

County

2357 San Pablo Avenue

Oakland, California 94612

Tel: (415) 465-3833

Of Counsel:

Mario Obledo

3 STATE OF CALIFORNIA

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

TO THE HONORABLE CHIEF JUSTICE AND ASSOCIATE JUSTICES OF THE

sup re; '.e court of the state of Ca l i f o r n i a:

Petitioners, HENRY ESPINOZA, LAURA M. HOLT,

JIMMY D. LOFTON, NORTHERN CALIFORNIA CONFEDERATION OF BLACK LAW

STUDENT ASSOCIATIONS, CHICANO LAW STUDENTS ASSOCIATION (CALIFOR

NIA) , NATIONAL ASSOCIATION FOR THE ADVANCEMENT OF COLORED PEOPLE

(WESTERN REGION), MEXICAN-AMERICAN POLITICAL ASSOCIATION, NA

TIONAL ASSOCIATION FOR THE ADVANCEMENT OF COLORED PEOPLE (SAN

FRANCISCO BRANCH), MEXICAN-AMERICAN BAR ASSOCIATION, THE LEAGUE

OF UNITED LATIN-AMERICAN CITIZENS AND THE AMERICAN G.I. FORUM,

and each "of them petition this Court for a Writ of Review of the

actions of Respondents, and/or a Writ of Mandate directed at

Respondents and each of them, and/or an application of the rule-

making power directed at Respondents and each of them, and by

this verified petition allege as follows:

////

//// • :

////

//// . ■

////

////

////

////

////

/ / / / 1 s ■ ■ ■ *

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

INTRODUCTION' *

Petitioners see); to improve the method by which applicants* Ijto the practice.of lav; are screened for competence, to up grade and

up-date the training process for attorneys, and to apply to the

selection process the same minimal legal standards which lawyers

have imposed upon other occupations in our society. In its present

form the written California General Bar Examination is virtually

worthless as a selection device, since 98% of the graduates of

accredited California lav; schools who take the examination eventu-

ally pass it. The legislature recognized the dubious effectiveness

of the bar examination when after WW II and the Korean War, it

exempted 367 veteran graduates of accredited schools from the bar

exam requirement. Among those 367 persons are leaders of the pro

fession, including a member of the Board of Bar Examiners, a senior

partner in the largest law firm in northern California-, and the

principal senior partner in one of the largest law offices in San

Francisco and the leading labor arbitrator .in- the state. Moreover,

it can hardly be said that the bar is an effective screening device

when an applicant within the last three years successfully passed

the bar after failing it on twenty previous occasions. Although

the bar fails to assure competence and does not even attempt to

affirmatively train anyone, it is highly effective as a device for

keeping the legal profession an overwhelmingly Caucasian institu

tion.

I

/// i

1

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

Accordingly, petitioners assert the legal right to have the

present California General Bar Examination— a racially discrimina

tory barrier which admittedly has no demonstrated validity as a

testing mechanism and which has never been shown to havê any rela

tion to competence as an attorney - replaced with a professionally

4

validated examination or a clinical alternative. The latter would

be of greater educational significance for both applicants and the

profession as a whole while offering more protection to the public.

All individual petitioners have already been awarded degrees from

*

California law schools accredited by the COMMITTEE OF BAR EXAMINERS

OF THE STATE BAR OF CALIFORNIA.

' . Ill

Petitioners' claims involve materially undisputed facts ana

questions solely of law. At Boalt and UCLA Law Schools, both

nationally acclaimed and the only two outstanding law schools in

California with significant numbers of minority groups graduates,

63% of the Blacks and Mexican-Americans were failed on the August

1971 examination, while only 15% of non-minorities (i.e., Anglos)

were failed. The results after two exam performances of the same

graduates showed that failure on the bar was 11 times more likely

for minority graduates than Anglos, 52% not having passed for

minorities as compared to 4.9% for Caucasians. The California Bar

Examination thus has a grossly discriminatory impact perpetuating

the shortage of minority attorneys; percapita, there are 35 times

as many Anglo lawyers as Mexican-Americans. .

II

2

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18,

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

The discriminatory impact of this unverified barrier to the

profession goes -far beyond the statistics. Every minority group

person who struggles through an undergraduate university and then

three years of repeated examination in lav; school, is a symbol of

hope for his community, and a statement that minority groups can

achieve justice by working within the'legal system. Petitioners

here, like most minority group law students, are highly visible

and are watched closely by their neighborhoods and minority group

communities. The chilling effect on minority group aspirations by

*refusing to admit them to the practice of law is incalculable.

V

Respondents here have been relatively indifferent to the

effect which the negative device of a written bar exam has had on

minority groups. Although professions and businesses of all kinds

now gather and keep racial statistics, the Bar has steadfastly

refused to do so even after being informed of their importance.

Worse, after being told of the discriminatory effect of the exami

nation, the Bar has taken the position that substantial revision

is not within their province. Respondents have also refused to

have the legal profession abide by the same minimal and reasonable

standards which they have insisted that every other profession and

trade adhere to. The result is that respondents are disobeying the

very same rules and law which they would, as lawyers, have the

courts and government impose on other professions.

IV

/// '

3

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

The established ca.se law concerning employment discrimination

is directly applicable to the Bar Examination. The Bar Examination

is an employment selection device which is racially discriminatory

in effect without the constitutionally redeeming value of being

related to the actual job of being a lawyer. A determination of

failure on the examination precludes petitioners and those

similarly situated from the right to earn a living and to serve

'their communities. But there are constitutional rights and freedoms

infringed upon other than the right to equal employment opportunity:

the* rights of petition, speech, assembly, and counsel. These

latter freedoms are of crucial importance to organizational

petitioners as representatives of a wide cross-section of the

Black and Chicano communities of California.

VII

Petitioners ask for relief which will benefit not only the

groups that they directly represent, but the profession as a

whole. All petitioners ask is that the Bar be required to assume-

an affirmative obligation for the training a'nd evaluation of

accredited school graduates so that-they can serve the community,

rather than relying on a negative and un-validated weeding-out I

process which does not even achieve its stated purpose. In short,

the relief which petitioners ask would result in all lawyers being

better trained. The present system on the other hand, eliminates

only a very small percentage of graduates with a speculative, slow,

cumbersome ,• unproven, and unprofessional testing mechanijsm which

VI

4

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

itself causes grave financial loss to applicants and law firms

and deprives minority grQups of their hope for effective expres

sion through the. legal process. 'w "' 'VJ

.... VIII ■ - .

PARTIES

Petitioner HENRY ESPINOZA is a Mexican-American male

who has applied for admission to the practice of law in California.

He (1) is a citizen of the United States (2) is over 21 years of

age; (3) is a bona fide resident of the State of California; (4)

has, prior to studying law, completed four years of college edu-

a

cation as evidenced by his receipt of the Baccalaureate Degree

from San Diego State College; (5) has graduated and received a

Juris Doctor Degree from the University of California at Los

Angeles School of Law, an institution accredited by the COMMITTEE

OF BAR EXAMINERS; and (6) is of good moral character. Petitioner

was failed by the COMMITTEE OF BAR EXAMINERS on its February 1972

exam. Petitioner is the former President of the first year class

of UCLA Law School and the former student body President of the Lav;

School. Petitioner has had extensive experience as a law student

affiliated with a Legal Services Program and with a private

practitioner. Due to petitioner’s inability to take the bar exam

in August 1971 and failure on the February 1972 exam he has been

unable to obtain employment in the legal profession. Petitioner

represents himself and all others of his ethnic heritage similarly

situated. Petitioner is a well known and respected figure in the

East Los Angeles Chicano community. IIis financial difficulties

5

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18.

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

with regard to the bar exam and his subsequent failure are well. K

known and discouraging to his community. [See PET. EXH. 1]

IX

.Petitioner LAURA M. HOLT is a black female who has

applied for admission to the practice of law. in California. She

(1) is a citizen of the United States; (2) is over 21 years of

age; (3) is a bona fide resident of the State of California; (4)

has prior to studying law, completed'four years of college educa

tion as evidenced by her receipt of the Baccalaureate Degree from

Los Angeles Pacific College; (5) has graduated and received a

Juris Doctor Degree from the University of California, Berkeley,

Boalt Hall School of Law, an institution accredited by the COMMIT

TEE OF BAR EXAMINERS, and (6) is of good moral character. Peti

tioner was failed by the COMMITTEE OF BAR EXAMINERS on the

February 1972 bar exam. Petitioner was employed for 8 months by

the office of the Attorney General of the State of California and

most recently by the private Beverly Hills law firm of William

Gaines Hill, Inc. Due to the action of the COMMITTEE OF BAR EX

AMINERS in failing petitioner on the February 1972 bar exam, she

was terminated from her employment. Petitioner and her family are

highly active well known members of the Los Angeles Black community

Her failure to receive a license to practice law is a source of

frustration for that community. Petitioner is believed to be the

first female of her race to have successfully completed three

years at Boalt and graduated. Petitioner represents herself and

all others of her race similarly situated. [See PET. EXH. 2]

/// ' '

6

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

X

Petitioner JIMMY D. LOFTON is a Black male who has

applied for admission' to the practice of law in California. He

(1) is a citizen of the United States; (2) is over 21 years of

age; (3) is a bona fide resident of the State of California; (4)

has, prior to studying law, completed four years of college edu

cation as evidenced by his receipt of the Baccalaureate Degree

from the University of San Francisco in 1965; (5) has graduated

and received a Juris Doctor Degree from the University of

California, Berkeley, (Boalt Hall) a law school accredited by the

»COMMITTEE OF BAR EXAMINERS AND (6) is of good moral character.

Petitioner was failed by the COMMITTEE OF BAR EXAMINERS on the

February 1972 bar exam. Petitioner is now and has been for the

ipast 10 months employed in the Legal Department of Pacific Gas and

Electric Company, a large California Corporation. However, Peti-

jtioner has suffered a demotion to the investigative section and

|

substantial salary decrease as a result of the determinations of |

the COMMITTEE OF BAR EXAMINERS. Petitioner has been active in

iCivil Rights and community activities in the Bay Area for the last

10 years. During this time he has become well known and highly

respected as a lay advocate. The refusal of the COMMITTEE OF BAR

EXAMINERS to certify him for . licensing has been a deep disappoint

ment and source of concern for the community which he serves.

Petitioner represents himself and all others of his race similarly

situated. [See PET. EX1I. 3]

- 7 -

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

Petitioners, NORTHERN CALIFORNIA CONFEDERATION OF BLACK

LAW STUDENTS ASSOCIATION (hereinafter BLACK LAW STUDENTS) is an

organization of Black law students enrolled at Northern California

Law Schools. The Confederation and its member associations initiate

and carry out various programs aimed at increasing the number of

Black law students enrolled in Northern California Law Schools,

supplementing the legal instruction received by such students, pro

viding lay advocate and law clerk services to the Black community,

and ending discriminatory practices still existing within the

prdfession. The organization represents more than 200 Black law

students in Northern California. It is anticipated that almost all

members of the Black Law Students' will apply for admission to

the practice of law in California. Approximately 25% of said

membership, 1972 graduates, have already made such application.

Thus, the certification and admission process .for licensing is of

paramount interest and importance to its membership.

XII

Petitioners, CHICANO LAW STUDENTS ASSOCIATION, CALIFORNIA

CHAPTER (hereinafter CHICANO LAW STUDENTS) is an organization

of Mexican-American law students present in schools throughout

California. The association is devoted to increasing opportunities

for Mexican-Americans to attend lav; school, providing a greater

number of Mexican-American attorneys to serve the local needs of

California's large Mexican-American communities, supplementing the

legal education received by dts membership wherever necessary, and

• *•

XI ; - . '

_ 8 -

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

combating discrimination that erects obstacles to the entry of

qualified Mexican-Americans into the legal profession. Its member

ship exceeds 200 students through the State. It is anticipated

that very many if not all members of the Chi.cano Law Students will

apply for admission to the practice of law in California. Approxi-^

mately 25% of its membership, 1972 graduates, have already made

such application. Thus, the certification and admission process j

to the practice of law is of great interest and importance to the

organization and its membership.

XIII

5 Petitioner, NATIONAL ASSOCIATION FOR THE ADVANCEMENT OF

• 1

COLORED PEOPLE, Western Region, (hereinafter NAACP-Regional) is

an organization devoted to fighting discrimination as it occurs

against Black People and improving the quality of life for Black

individuals in the 11 Western States which compose its jurisdic-

• . . . . Ition. It has been particularly active in the legal arena partici-

|

pating in numerous instances of litigation directed at vindicating

the rights of Black people through the judicial process.

X!V

Petitioner, MEXICAN-AMERICAN POLITICAL ASSOCIATION

i

(hereinafter MAPA) is a broad-based political association having

its constituency in the Mexican-American community. As such, it i

is greatly concerned with all problems of the Mexican-American

citizens but particularly those involving the fundamental consti-

!

tutional rights of its constituents. Foremost among those problems

I

are a lack of sufficient legal services and the discriminatory

9

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

Americans into various professional fields, including the law.\

• •••. • • XV - ........ ... ... .... ...'* t

Petitioner, NATIONAL’ASSOCIATION OF ADVANCEMENT OF i

COLORED PEOPLE, San Francisco Branch (hereinafter NAACP-S.F.)

Iis a San Francisco based organization whose membership is largely

drawn from the Black community of -San Francisco. NAACP-S.F. has

actively fought racial discrimination which degrades the quality

of Black people's lives. It has been particularly concerned with

attempting to vindicate the rights of Black people through the

*judicial process.

XVI

Petitioner, MEXICAN-AMERICAN BAR ASSOCIATION is an estab

lished association of Mexican-American attorneys throughout the

State of California. The association is concerned with the legal

problems of the Mexican-American community in particular as they

pertain to the inadequacy of legal services. It has consciously

and actively undertaken efforts to encourage'the entry of qualified

Mexican-Americans into the practice of law..̂

XVII

Petitioner, LEAGUE OF UNITED LATIN AMERICAN CITIZENS

is a multi-state membership organization concerned with the civil

rights and social problems of the Mexican-American community in

California and the South Western part of the United States. The

Petitioner has been active in the legal arena in defending the

rights of members of the Mexican-American and Spanish-surname

barriers which'presently impede the entry of qualified Mexican-

10

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

community.

Petitioner, AMERICAN G.I, FORUM is the largest Mex.ican-

American veterans organization in the nation'. Petitioner has been

very active in advancing the rights of Mexican-Americans in the

courts. In its efforts to obtain legal redress for members of the

Mexican-American community, Petitioner has had cause to be concerned

about the small number of Mexican-American attorneys admitted to

practice in California.

XIX

i Respondents are the COMMITTEE OF BAR EXAMINERS OF THE

STATE BAR OF CALIFORNIA, BOARD OF GOVERNORS OF THE STATE BAR OF

CALIFORNIA, and THE STATE BAR OF CALIFORNIA. Purusant to

California Bus. & Prof. Code § 6064, the COMMITTEE OF BAR EXAMINERS

is charged with certifying to the Supreme Court of California for

admission to.the Bar those applicants found fit to practice lav;.

In order to determine which applicants shall be certified, the j

respondent COMMITTEE inter alia administers a written test known as

the California General Bar Examination as authorized by Section 111

and 112 of the Rules Regulating Admission to Practice Law and Bus.

& Prof. Code §§ 6046 and 6060. Respondent BOARD OF GOVERNORS is

: „ . |the governing body of the STATE BAR OF CALIFORNIA; as such, it is

empoweri-d to establish a COMMITTEE OF BAR EXAMINERS for the examin-j

ation of all applicants for admission to practice, administration .

of the requirements for admission to practice, and certification

to the Supreme Cpurt for admission to practice. Calif. Bus. £ Prof.

\'

XVIII

11

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

XX

JURISDICTION . *.

Petitioners invoke the original jurisdiction of this

Court pursuant to Article VI, Section 10, of the California Con

stitution; Section 1085 of the Code of Civil Procedure; and Rule

59 of the Rules of Court on Review ..of State Bar Proceedings.

///

XXI

As hereinafter more fully appears, respondents have denief

• u 1and continue to deny the equal employment and due process rights

Iof individual petitioners and the rights to counsel, freedom of

association and petition for redress of grievance's of organiza

tional petitioners. These are riahts which are secured by the

IConstitution of the United States and the Constitution of the

State of California. Said .unlawful • denial of rights and violations'

of law raise issues affecting four and a half million California

minority residents. The rights of all graduates of California

accredited law schools to a legitimate, jobrvalidated, non-arbitrar;.)I

and non-discriminatory licensing system for the legal profession

. ‘ Iare especially violated. As hereinafter more fully appears,

Petitioners have no plain, speedy, or adequate remedy in the

ordinary course of lav.', and there are exceptional circumstances

making it necessary that this Court accept original jurisdiction

of this matter.

///

Code §§ 6010 and 6046.

12

]

r

r

i

£

(.

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

XXII

\

Petitioners also invoke the original jurisdiction of

this Court pursuant to § 6066 of the Business and Professions Code

which permits any person whom the COMMITTEE.OF BAR EXAMINERS j

refuses to certify to the Supreme Court for admission to the prac-

tice of law to have said denial reviewed by the Supreme Court.

California Bus. and Prof. Code § 6066.

XXIII

Petitioners, lastly, invoke the original jurisdiction of

' ithis Court based on its inherent power to establish the rules and

; Iprocedures which govern the legal profession and admission to

the practice of law in California.

XXIV

RESPONDENTS' UNLAWFUL DENIAL

OF PETITIONERS' RIGHTS TO

EQUAL PROTECTION OF THE LAWS

Petitioners ESPINOZA, HOLT and LOFTON, having satisfied

|

all other pre-requisites for admission to the practice of law in

i

California, took the California Bar Examination on February 22, 23

and 24, 1972.

XXV

'

On or about May 15, 1972, Petitioners ESPINOZA, HOLT

and LOFTON each received written notification from respondent COM-

j

MITTEE OF BAR EXAMINERS that he or she had failed to pass the »t

California Bar Examination and, therefore were not eligible to be

certified to the Supreme Court for admission to the 'practice of lav:.

No other reason was given for such denial and no other reason for

- 13 -

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

denial existed at that time or at the present time'.

........... ,r. XXVI

The February, 1972, Bar Exam had a racially and. ethnic

ally discriminatory effect against Black and- Mexican-American

examinees, including petitioners ESPONOZA, HOLT and LOFTON herein.

XXVII

The discriminatory effect- of the February, 1972, Califor

nia Bar Examination represents part of a continuing pattern of

racial and ethnic discrimination by said Bar Examination.

(A) According to a survey of the August, 1971 examina

tion only 44% of the Black and Mexican-American graduates of re

sponding accredited law schools passed the examination compared to

76.4% of the non-minority graduate-applicants.

(B) At UCLA and Boalt Hall, which graduated over half

of the minority students, the passing rate was 37% for Blacks ana

Mexican-Americans and 85.0% for Anglos, i.e. non-minorities.

(C) The Boalt Hall class of 1969 showed a pass rate for

minorities of 14% on the first try, 28% after the second try; and j

57% on the third try. The comparable rate for Anglos graduates

was 73% for the first try and 91% for the second.

(D) In the years 1967, 1968 and 1969, less than 50° o_

Black graduates (from a majority of the accredited California law ■

schools) who took the California Bar Examination-passed after two

attempts. Meanwhile, between the years of 1954 and 1969, 76.9%*■ ’ •

of all graduates of accredited California law schools passed the j

California Bar Examination on the first attempt. Furtheimore,

14

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

.n the specific period of 1968 through 1969 90% of ail graduates

>f accredited- California lav; schools had passed the Bar Examination

ifter tv’O attempts.

!n sum, Respondents' determination that individual petitioners failec

:o pass the California Bar Examination is part of an ongoing raciall’

iiscriminatory effect which denies licensing to Blacks and Chicanos

it a rate twice that for Anglos. This-is so even when statistics

.re construed in a light most favorable to respondents, i.e. based

>n comparative passing rates as opposed to comparative failure rates.

XXVIII

Individual petitioners have each suffered substantial

inancial loss as a direct result of the determination of the

IOMMITTEE OF BAR EXAMINERS that they had failed the Bar exam and the

esulting exclusion from the licensed practice of lav;.

XXIX

Petitioners have made due and timely demand upon respon-

,ents. • Respondent COMMITTEE OF BAR EXAMINERS was advised by counsel

or petitioners in September, 1971, that the results of California

,ar Examinations pjrior to that examination administered in August, "

971, had a discriminatory effect against Black and Mexican-American

pplicants, and, that to be consistent with the Equal Protection

lause of the Fourteenth -Amendment to the United States Constitution

nd Due Process requirements, respondents should either abandon use

f the Bar Examination in its present discriminatory and unvalidated

orm as a screening device or validate the Examination in accordance

ith applicable legal requirements and acceptable professional

15

!i

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

standards for test construction and use.

XXX

In addition, Petitioners have specifically made timely

lemand upon respondents in.a letter of May, 1972, requesting alter-

ition of the arbitrary and discriminatory written bar examination

irocess. [SEE PETITIONERS EXHIBIT 26]

XXXI

Despite this knowledge, respondents refused and continue

;o refuse to perform even the initial and most- rudimentary steps

.n the validation process. Moreover, respondent proceeded to ad-

sinister a_ similar examination, the February, 1972, California Bar

'.xamination, which had an even greater discriminatory effect. In

.he face of this, respondent has announced its intentions to continue

:o screen applicants by use of the Bar Examination.

XXXII

Respondents have neglected and refused to attempt to

’alidate the Bar Examination although it has an opportunity to do

;o under almost laboratory conditions. Three hundred and sixty-seven

367) World War II and Korean War veterans were admitted to practice

aw without ever tailing the California Bar Examination, pursuant to

•us. & Prof. Code §§ 6060.5, 6060.8 (now repealed). Defendant could

dminister the Bar Examination to these attorneys, make judgments as

o their competence, and then correlate, test scores with level of

ompetence to ascertain whether or not the -Bar Examination actually

oes separate the competent from the incompetent. Respondents have

efused to take even this minimal step. '■

16

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17-

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

Individual Petitioners have been denied equal protection

f the laws in violation of the Fourteenth Amendment to the United

tates Constitution because they have been denied certification to

ractice lav; as a result of their failure to pass the CaliforniaI '

ar Examination, an unvalidated testing device which has been shown

o discriminate unfairly against applicants of their ethnic group.

XXXIII

WHEREFORE, Petitioners, on behalf of themselves and others

imilarly situated pray as hereinafter stated:

17

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25'

26

27

SECOND INCLUDED PETITION

The petitioners on behalf of themselves and all others

similarly situated,

RESPONDENTS' UNLAWFUL DENIAL OF

PETITIONERS RIGHTS TO DUE PROCESS OF LAW

Re-allege and reiterate all of the allegations contained

_n paragraphs I through XII and XIX through XXXII inclusive, of the

^irst Petition herein.

: II

Individual petitioners were denied the right to practice

Law because of their failure to pass an arbitrary, .unreasonable,

md costly examination that has and had no demonstrable rational

relation to competence to practice lav;. This is especially so in

_ight of the burdensomeness, subjectivity, and failure to measure

orucial skills involved in the present system and the wealth of other

iLess onerous and more beneficial devices available to test competence

\s a consequence of the above individuals have been denied due

^recess of law in violation of the fourteenth amendment to the

Jn.ited States Constitution and /article I § 13, Cl. 6 of the Calif

ornia Constitution, and Lav; Student petitioners anticipate the denial

of such rights in the immediate future.

Ill

The California Bar Examination is a written test the

stated purpose of which is to measure an applicant's competence to

18

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

practice law. Respondent's have no other lawful interest in

devising and’administering said Examination. Respondents have com- JI

plete discretion to formulate the examination under Rules -Regulating

Admission and Practice Lav? §111-114 except that the exam must be

written. Applicants, including petitioners ESPINOZA, IIOLT, LOFTON,

BLACK LAN STUDENT AND CHICAUO LAN STUDENTS herein, are required to

answer essay and objective questions: bn the following legal subjects:

Civil Procedure, Conflicts of Laws, Constitutional Law, Contracts,

Corporations, Crimes & Criminal Procedure, Equity, Evidence, Propert /

and Torts. Applicants have the option of answering questions on

Community Property, Federal Income and Gift Taxation, Trusts and

Estates, and Wills and Successions.

IV

The format of the California Bar Examination is somewhat

similar to many law school examinations which petitioners HOLT,

ESPINOZA,LOFTON, BLACK LAW STUDENTS and CHICANO LAW STUDENTS, and

all applicants for admission to practice must negotiate successfully

if they are to graduate from an accredited lav/ school. By gradua

tion from these schools petitioners have already demonstrated the

competence which such tests may indicate. Moreover, the Bar

Examination is administered over a three day period.while law school

examinations are spaced out over a three year period. Beyond the

contrast bn time-frame, there are other extraneous factors in the

limited time situation: an applicant's endurance, his ability to

"cram" "black letter" legal principles in a short time, and the

quality of his bar review course. Consequently an intensive,

19

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

3.7

hree day Bar Examination is highly suspect as an accurate- measure

if an applicant's fitness to practice lav? in comparison to three

ears of lav: school education and testing.

V

The California Bar Examination as presently constituted

s very limited as a device to test even a part of the full range

if skills needed for competent legal practice. It in no v:av tests

egal research ability or skill in oral advocacy. In addition it •

[oes not consider psychological, social,’emotional or personal

:itness: capacity to negotiate; adeptness in the use of the proced-

iral*mechan.isms of our legal system, or the ability to form and

levelop successfully the attorney-client relationships. All of these

ire crucial if the attorney is to serve the client .and public in a

irofessional manner.

VI

A final bar examination is.not necessary to screen granu

les of accredited California lav: schools. That function is per-

iorned by the lav? school admission process and the law school itself

implications for admission to law school have risen dramatically in

recent years. For instance, at Stanford Law School in 1964, 1029

versons applied for 155-160 places in the entering class; in 1972,

(867 persons - a four-fold increase - applied for the same number of

nlaces. As a result of the great rise in numbers of applicants for

idmission to law school, competition for places is substantially

;ecner as demonstrated by the higher Legal Aptitude scores and under-

jraduate grade-point averages of entering classes. In 1969, the

iverage Legal Aptitude score of the'entering class at Stanford was

20

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

63 (out of a possible 800); thirteen years later, the figure was

'19. The average undergraduate grade point average for Stanford's

altering class in- 1959 was 2.91 (just below a "B"); in 1972 , the

iverage was 3.72 (just below an "A"). Thus, only the most qualified

persons even enter accredited California lav; schools.

VII

Recent historical information shows that the Bar Examina-

:ion is totally unnecessary for graduates of accredited California

jav7 Schools. Nearly all of those who graduate from such schools are

competent in respondent's own terms, since, between World War II

*:nd 1970, 98% of those graduates eventually passed the California

Jar Examination if they were able financially to take it repeatedly.

.VIII

In addition to its other inadequacies and redundancies

is alleged herein the California Bar Examination is a costly device.

. . !ŝ well as the expenses of administering and grading the examination ;

. !/hich the State must bear, the Bar Examination necessitates a sigm- ̂

Ticant financial investment for applicants in fees to take the exam-

i[nation and tuition in bar preparation courses. Petitioners ;

CSPINOZA, HOLT and LOFTON, BLACK LAW STUDENTS, CHICANO LAW STUDENTS [

ind other applicants also individually suffer lost wages and costs

reading as high as $12,500 because of the long time lag before tests

are graded, results posted, and applicants finally admitted to

practice. ;

IX

Respondent has at its disposal a myriad of less onerous,

21

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

ess discriminatory and more effective ways to measure competence

o oractice 1'nw for accredited law school graduates, Such alterna- |i, i.ives in large part would depend upon successful graduation from an j

. 1

ccredited law school accompanied by a clinical-type training' program

,r evaluation period. A sample of such alternatives might be:

A. A mandatory extern program between the second and third

■ears of law school leading to automatic admission to the Bar upon

[uccessful graduation.

B. A program similar to the above but also requiring

ittendance at a State Bar sponsored practical training program for a

:wo-vfeek period after graduation and for a three—day session one

'ear after graduation.

C. Alternative 'A1 except admissions would be conditioned

:pon the successful preparation and handling of a misdemeanor trial

mder supervision within six months after graduation.

D. A program which incorporates all or some combination

>f the requirements of A, B, and C above.

E. A mandatory practical training institute for two months

ifter graduation conducted in cooperation with the State Bar and the

iccredited law school. Upon successful completion of such a program,

idmission to the Bar would be automatic. • * l

F. A one-year commitment to working with-legal services op

>thor programs directed at underrepresented communities and lower

;o middle income groups. Conditional admission to the Bar would

:ome after four months of successful performance and would be followd

ry permanent admission at'the end.of'one year's successful performan

22

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

G. Automatic admission to the Bar upon graduation from an

.accredited California lav; 'school. Such admission would be condi

tioned upon acceptable performance for one year, or its equivalent

as certified by an experienced attorney and determined by the State

Bar.

H. Automatic admission to the Bar upon successful'gradu

ation from an accredited California law school.

I. Certification by licensed attorney, judge, or law

school dean of acceptable performance as an attorney for a one-year

period. Such a period could include summer jobs or part-time jobs

*

prior to graduation. But such certification would not become

iffective until successful graduation.

J. Any one or any combination of the above coupled with a

ion-discriminatory, validated selection device.

K. Any combination of the above.

X .

Respondents' use of an unnecessary arbitrary redundant

examination which puts a premium on non job-related skills, which

fails to test numerous crucial job skills and-'which has no demon-\

strated rational relationship to the interests of the state, in the

race of rising standards of excellence in law school admissions and

less onerous alternatives, constitutes a denial of due process.

•WHEREFORE, Petitioners pray as hereinafter stated:

23

]

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

2'5

26

Organizational petitioners on behalf of themselves,

their membership and the Black and Chicano communities of the

State of California,

I

RESPONDENTS' UNLAWFUL DENIAL OF THE

CONSTITUTIONAL EIGHTS OF ORGANIZATIONAL

PETITIONERS AND INDIVIDUALS IN THE BLACK

AND CHICANO COMMUNITIES OF CALIFORNIA.

Reallege and reiterate all of the allegations contained

in paragraphs I through VII, XI through XXIII, and XXVII through

XX^II, inclusive, of the first petition herein.

II

Nearly one-quarter of California's population is either

Black o.f Mexican American. Only 2% of the attorneys in California

are members of these minority groups. While there is one Anglo j

attorney for every 450 Anglo Californians, there is only one Black i

attorney for every 3100 Black Californians and one Mexican Ameri

can attorney for every 1 5 , 900 Mexican American Californians.

Ill

By discriminating against minority•persons, the

California bar examination perpetuates the shortage of minority

attorneys. First of all, it absolutely exludes from the practice j

of law many Blacks and Mexican-Americans who have-chosen law as

a profession and been appropriately trained. Secondly, awareness

of the discriminatory effect of the Bar Examination discourages

many minority persons from pursuing a career in law; and thirdly,

THIRD INCLUDED' PETITION

24

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

.knowledge of this first effect has a direct impact on the ability

of minority group and persons to fully exercise and protect their

legal rights.

IV '

The shortage of minority attorneys means that minority

citizens must entrust their legal problems almost exclusively to

Anglo attorneys. This jeopardizes and often prevents the develop

ment of any effective attorney/client relationship due to the

following: the differing customs and mores of the majority and

minority clutures; the latent as well as apparent tensions and

*hostilities between majority and minority groups; the differing

residential locations and geographical concentrations between Angle

attorneys and minority clients; and at times, the absolute language

barrier which exists between the two.

V

The shortage of minority attorneys and the resulting

difficulty for minority persons in forming (1) an effective relatic:

ship with their attorneys and (2) in fully communicating legal

grievances, prejudices the constitutional rights of Black and

Mexican-American citizens in both civil and criminal areas: the

right to petition for redress of grievances under the First

Amendment to the United States Constitution; the right to effective

assistance of counsel under the Sixth Amendment to the United

States Constitution; and the right to due process under the

Fourteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution.

///

25

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

VI

As noted supra, respondents were asked by petitioners

:o take steps to validate the California Bar Examination as' a

screening device for applicants to the practice of lav? or, in the

rlternative, to abandon it until minimal professional and legal

standards are met in devising a selection process. Respondents

refused and have announced their intention to continue to use the

California Bar Examination in its present form to examine applicants

~o the California Bar. In short, repeated requests and demands have

?een made on respondents to revise their arbitrary discriminatory

md harmful licensing procedure. 'Respondents answered that they

rave no such plans.

VII

Petitioners have no further administrative remedies to exhaust and

io other prompt, speedy, or' adequate remedy at lav;.

WHEREFORE, Petitioners ESPINOZA, IIOLT and LOFTON, on be-

lalf of themselves and all others similarly.situated, pray:

1. That they be certified forthwith to the Supreme Court

For admission to the practice of lav? in the State of California;

2. For reasonable attorneys fees;

3. vor the costs of this action;

.4. And for such other relief as this court in its

aisdora shall deem necessary.

WHEREFORE, Petitioners, NORTHERN CALIFORNIA CONFEDERATE:

26

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

27

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

IF BLACK LAW STUDENT ASSOCIATIONS, CHICANO LAW STUDENTS ASSOCIATION

(CALIFORNIA), NATIONAL ASSOCIATION FOR THE ADVANCEMENT OF COLORED

PEOPLE (WESTERN REGION)', MEXICAN-AMERICAN POLITICAL ASSOCIATION,

NATIONAL ASSOCIATION FOR THE ADVANCEMENT OF COLORED PEOPLE (SAN

FRANCISCO BRANCH), MEXICAN“AMERICAN BAR ASSOCIATION, THE LEAGUE OF

JNITED LATIU-AMERICAN CITIZENS AND THE AMERICAN G.I. FORUM, pray:

1. That this court declare the California General Bar

Examination as presently constructed and administered to graduates

3f accredited California law schools to be in violation of the due

process and equal protection clauses of the Fourteenth Amendment to » •

*;he United States Constitution and in violation of Article 1 § 13

:l. 6 of the California Constitution;

2. That, in order to create the least disruption in the

Licensing process for attorneys in this state, this court issue its

peremptory Writ of Mandate directing that the Committee of Bar

Examiners for a period of one year from the date of such Writ,

rertify to this court for admission to the practice of law in Calif

ornia all those applicants found by the Committee of Bar Examiners

;o be twenty-one years of age or over, to be a' bona fide resident of

ihe State of California, to be of good moral character, to have met

ihe pre-legal educational requirements set forth in Bus. & Prof. Code

3 6060(e), and.to have received the Juris Doctor or Bachelor of Laws

legree from an accredited California law school.

3. That, in order to develop a selection and evaluation

levies which is constitutional and not racially discriminatory, this

pourt do any one of the following:

27

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

' a) Issue its peremptory Writ of Mandate directing

he Committee•of Bar Examiners for the future to construct a profes-

lionally validated general bar examination. Such validation shall

:onform with the guidelines established by the'Equal Employment

>pportun.ity Commission and the developing standards of the lav; in

:he area of non-rac.ially discriminatory testing.

b) If the Committee of Bar Examiners should be

mwilling or unable to develop an examination such as"a)" supra in

:he immediate future, order the Committee to develop a procedure

'hereby they shall certify to this court for admission to the pract- *

.ce of lav; in California all those applicants found by the Committee

>f Bar Examiners to be twenty-one years of age or over, to be a bona

fide resident of the State of California, to be of good moral

:haracter, to have met the pre-legal educational requirements set

forth in Bus. & Prof. Code § 6060(e), to have received the Juris

)octor or Bachelor of Laws degree from an accredited California lav;

school, and to have completed some alternative to a final bar

examination in the nature of but limited to those alternatives set

forth in allegation IX of the Second Included/Petition herein.

c) Appoint a distinguished panel of members of the

3ar as Special Masters to develop an alternate form of evaluation to

:he present bar examination which meets the constitutional standards

if the United States and the State of California.

4. That, as an alternative to 1 through 3 supra, this

:ourt declare that a prima facie case of racial discrimination in

iffect has been found against the present bar examination and appoint

20

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

15

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

, Special Master or panel of such for one year to oversee the con

struction and development of an alternative form of evaluation as a

>re--requis.ite to certification to this court for admission -to. pract

ice in order to remedy the suspect racial classification which re

sults from the present examination.

5. For reasonable attorneys' fees;

6. For costs of this action;

7. For such other relief as this court in its wisdom

shall deem necessary.

29

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

VERIFICATION

. *

I, JIMMY D. LOFTON, under the penalty of perjury

declare: ' • .

That I am one of the petitioners in the above

entitled action; that I have read the foregoing petition

for Writ of Review and/or V7r.it of.Mandate and know the

contents thereof; that the same is'true of my own knowledge.

Executed at San Francisco, California, this 16th

day of June, 1972.

30

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

2G

ROBERT L. GWAIZDA, ESQ.

SIDNEY M. WOLENSKY, ESQ.

ALBERT F. MORENO, ESQ.

J. ANTHONY KLINE, ESQ.

JO ANN CHANDLER, ESQ.

Public Advocates ,■ Inc.

433 Turk Street

San Francisco, California 94102

Tel: (415) 441-8350

TERRY J. HATTER, JR., ESQ.

ABBV SOVEN, ESQ.HAROLD HART-NIBBRIG, ESQ.

LORETTA SIFUENTES, ESQ.

Western Center on Law & Poverty

1709 West 8th Street

Los Anqeles, California 90017

Tel: (213) 483-1491

MARTY GLICK, ESQ. .

CRUZ REYNOSO, ESQ.

MIGUEL MENDEZ, ESQ.

California Rural Legal Assistance

1212 Market Street

San Francisco, California 94102

Tel: (415) 863-4911

ALAN EXELROD, ESQ.

MICHAEL MENDELSON, ESQ.

Mexican-American Legal

Defense and Educational Fund

National Office

145 - 9th Street

San- Francisco, California 94103

Tel: (415) 626-6196

CHARLES JONES, ESQ'.

Los Angeles Legal Aid

Foundation

1819 West Sixth Street

Los Angeles, California 90017

Tel: (213) 484-9550

ELLEN CUMMINGS, ESQ.

Legal Aid Society of Alameda

County

2357 San Pablo Avenue

Oakland, California 94612

Tel: (415) 465-3833

STAN LEVY, ESQ.

STANLEY W. KELLER, ESQ.

Beverly Hills Bar Association

Lav? Foundation

300 South Beverly Drive

Beverly Hills, California 90212

Tel: (213) 553-6644

Attorneys for Petitioners

IN THE SUPREME COURT OF

HENRY ESPINOZA, LAURA M. HOLT,

JIMMY D. LOFTON

NORTHERN CALIFORNIA CONFEDERA

TION OF BLACK LAW STUDENT AS~

SOCIATIONS, CHICANO LAW STUDENTS

ASSOCIATION (CALIFORNIA), NA

TIONAL ASSOCIATION FOR THE AD

VANCEMENT OF COLORED PEOPLE

(WESTERN REGION) , MEXICAN-AM

ERICAN POLITICAL ASSOCIATION,

NATIONAL ASSOCIATION FOR THE

ADVANCEMENT OF COLORED PEOPLE .

(SAN FRANCISCO BRANCH),

Of Counsel:

Mario Obledo

THE STATE OF CALIFORNIA

)

)

)

)

)

)

) NO.) --------:-----------

) -

)

)

) -

)

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

MEXICAN-AMERICAN BAR ASSOCIATION,)

THE LEAGUE OF UNITED LATIN- )

AMERICAN CITIZENS AND THE )

AMERICAN G.I. FORUM, )

. ' * , )Petitioners, )

)vs. )

)THE COMMITTEE OF BAR EXAMINERS )

OF THE STATE OF CALIFORNIA, )

THE BOARD OF GOVERNORS OF THE )

STATE BAR OF CALIFORNIA, AND )

THE STATE BAR OF CALIFORNIA, )

)Respondents. )

)

MEMORANDUM OF POINTS AND AUTHORITIES IN SUPPORT

OF PETITION FOR WRIT OF REVIEW AND/OR WRIT OF

MANDATE AND/OR APPLICATION TO EXERCISE RULE-

MAKING POWER

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

I.

II.

Ill.

TABLE OF CONTENTS

,TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

INTRODUCTION

Page

• *.

i

STATEMENT OF FACTS .......... iv■ •

BECAUSE THE ISSUES PRESENTED ARE OF EXTRAORDINARY

IMPORTANCE FOR THE PRACTICE OF LAW IN CALIFORNIA

AND FOR THE PUBLIC AND REQUIRE PROMPT RESOLUTION

THIS COURT SHOULD EXERCISE ITS ORIGINAL JURISDICTION . 1

RESPONDENTS' CONTINUED EXCLUSION OF RACIAL AND ETHNIC

MINORITIES FROM LEGAL PRACTICE EY A DISCRIMINATORY

EXAMINATION WHICH IS NOT JOB RELATED CONSTITUTES A

DENIAL OF EQUAL PROTECTION AND DUE PROCESS ...... . 7

A. The California Bar Exam Discriminates On The

Basis of Race Against Black And Chicano Law

School Graduates, Establishing A Prima Facie -

Case of Racial Discrimination Which

Respondents Have Not Even Attempted To Answer ... 7

B. Based On The Undisputed Facts In This Case

the~clTlifornia Bar Exain Is Not Related To The

Actual Practice Of Lav; ...... ...............

1 Respondents Have The- Burden Of Proving

That The Bar Exam Is Job Related ....

2. The Only Constitutionally .Acceptable

Method Of Showing That The Bar Exam Is

Job Related Is Through Professional

Validation ____

3. Respondents Admittedly Have Failed To

Meet Their Burden Of Showing That the

Bar Exam Is Job Related Because They

Have Not Even Attempted To Validate

The Exam

BOTH THE STATE AND FEDERAL CONSTITUTIONS FORBID THE

EXCLUSION OF PERSONS FROM THE PRACTICE OF LAW BY AN

ARBITRARY EXAMINATION WHICH VIOLATES THE PROTECTIONS

AFFORDED BY DUE PROCESS CLAUSE OF THE FOURTEENTH

AMENDMENT. . ....... 23

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

A. The Committee of Bar Examiners Is Bound By

The ?•■ andate Of The Due Process Clause Of

Beth .The Fourteenth Amendment To The United

States Ccnstitution_ And Article I Section

13, Clause 6, Of The California Constitution ... 23

B . The Plaintiffs Have A Fundamental And

Const!tut-iona 1 ly Protected Right To

Practice The Profession Of Law. .......... 24

C. The Present Bar Examination Requirement

Tllegally Impairs The Plaintiffs 1 Right

To Practice Law Because It Does Not Have

A Rational, Real, Or Substantial Relation

To The Purpose It Seeks To Accomplish. ..... 25

Page

D. Defendants Have Less Onerous Alternatives To

* The Present Bar Examination Which Would Serve

Equally Well or Better To Insure Competence

In The Legal Profession. ..... 3 2

IV . THE BAR -EXAMINATION DEPRIVES BLACK AND CHICANO

CALIFORNIANS OF LEGAL SPOKESMEN, IN VIOLATION OF

THE FIRST, FIFTH, SIXTH AND FOURTEENTH AMENDMENTS,

BY ARBITRARILY EXCLUDING MINORITIES FROM THE

PRACTICE OF LAW. ...... 36

A. Exclusion of Blacks And Chicanos From Law

Practice Deprives Minority Citizens Of Their

Right To Petition For Redress Of Grievances

Under The First Amendment. ..... 36

B • Exclusion Of Blacks And Chicanos From Law

Practice Deprivos Minor1 1ies Of Rights To

Effective Assistance Of Counsel. . ..... 43 V.

V. BECAUSE THE PRESENT WRITTEN BAR EXAM RESULTS IN A

CLASSIFICATION INFRINGING ON THE FUNDAMENTAL RIGHT

TO PRACTICE LAW WITHOUT SERVING ANY COMPELLING

STATE INTEREST AND DISREGARDING LESS ONEROUS'

ALTERNATIVES PETITIONERS HAVE BEEN DENIED EQUAL

PROTECTION

A . The Rlght To Practicc Law Is A Fundamental

Flight Within The Meaning Of The Equal

Protoot.ion C1 ause Of The United States And

California Constitutions. ... 48

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

VI.

B . The Disc rimlinato r y Re su 1 ts Of The Bar

Exam Create A Suspect Category Within

The Moaning Of The Equal Protection And

Due Process Clauses Of The United -States

And California Constitutions.. .. ...... 4 9

C. The Par Exam _Is_Not Necessary/ Or Even

Particularly Useful In Furthering Any

Cornye11ing State Inherest Especially In

Light Of The Alternatives Available. ...... 50

Page

CONCLUSION

1

c

4

r<

e

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

t a b l e o f a u t h o r i t i e s

CASES

Alabama v. United States, 304 F.2d 583

(5th Cir. 1962) ; aff'd, 371 U.S.37 (1962) ........ ................

Aptheker v. Secretary of State, 378 U.S. 500 (1964) . . . . ........

ft.rmstead v. Starkville Municipal Separate

School District, 325 F. Supp. 560 (¥7""

D. Miss. 1971) aff'd and rev1d in part

___F2d___, No. 71-212 4 , June 9, 19/72(5th Cir. ) .....................-

Arrington v. Mass Bay Transp. Auth.,

306 F.Supp. 1355 (D.Mass.1969) . . . .

*

Baird v. State Bar of Arizona, 401 U.S.

1/ (1971).......... T T ...........

Baker v. Columbus Municipal Separate

School District, 32 4 fTsuppl 70lT’(N .A. Miss. 1971) ........ . . . . . . .

Salff v. Bar Examiners, 1 Cal. 2d

789 (1934) . . . ............... ..

iodic v. Connecticut, 401 U.S.

371 (1971)• . . . . . . •........

rotherhood of Railway Trainmen v.

Virginia, 377 U.S. 1, (1964) T . . . .

rown v. Craven, 424 F2d 1166 (9th Cir. 1970)........................

rydonjack v. State Bar, 208 Cal.

439 (1929") . . . . ........... ..

utchers Union Co. v. Crescent City

Co., 111 U.S. 746 (1884) . . T T . .

PAGE NO.

. 7

. 32

7,8,13,17

8,9,13

3,25,48

8,13

1

38

37,3 9

45

A

25

rinaton v. Rash, 380 U.S. 89

(19 6 5) . . ........... ' . . 50

1

2

3

4

5

<6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

1.7

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

23

2(

ter v. Gallagher, 337 F.Supp. 626,

3 E . P . D.',(82 05 (D.Minn.1971) , af f 1 d

in part, revld in part, 452 F2d

315 (8th Cir. 1971) , modified en-

banc 452 F.2d 327 (8th Cir. 1972),

cert den May 24 , 1972.................................... 8,9,12

13

CASES (cont'd) PAGE NO.

stro v. Beecher, 334 F.Supp. 930,

(D. Mass. 1971) , aff'd and modi

fied F2d , 4E.P.D. 117783,

Nos. 71-1180, 71-1395, 71-1396

April 26, 1972, (1st Cir).. . .

hance v. Board of Examiners and Board

of Education, 330 F.Supp. 203 (S.D.

NY. 1971), aff'd, F2d , 4 E.P.D

1(7756, No.71-2021, April' 5, 1972

(2nd Cir . )............ ............ . 8,10,14

15,16,19

50

offey v. Braddy, No. 71-44-Civ.J, May

19, 1971, (M.D. Fla.) ............

ounty of Sacramento v. Hickman, 66

Cal. 2d 841 (1967) ..............

q v. Blumstein, US , 40 U.S.L .W . 4269

(March 21, i.972)............ . ,42,49

-isenstadt v. Baird, US___40 U.S.L.W

4304 (March 22, 1972) ............ 33

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

15

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

2-5

25

CASES (cont'd) PAGE NO

Gideon v. Connecticut, 372 U.S. 335

(1963)..................... . . . . . . . . . .......... 43

Greene v. Committee of Bar Examiners,

4 Cal. 3rd 189, (1971) ..................... 1,2

Griswald v. Connecticut, 381 U.S.

479 (1965) " ..................... ................ .. 33

Griggs v. Duke Power Co. 401 U.S. 424 (1971) . . ........... 8,9,12

Hallinan v. Committee of Bar Examiners,

65 Cal. 2d 447 (1966) .................................... 1,2 .

Harper v. Vircrinia State Board of

Elections, 383 U.S. 663 (1966)........................... 39,41,42--------- 49

Hawkins v. Town of Shaw, 437 F2d

1286 (5th Cir. 1971).......... ................ * . . . . 7

Hildebrand v. State Bar of Calif.,

36 Cal. 2d,. 504 (1953)................................... 38

\ ’

In re Antazo, 3 Cal. 3d 100, (1971)........................ 49

In re Shattuck, 208 Cal. 6 (1929)..........................5,49

In re Investigation of Conduct of

Examination For Admission to Prac

tice Law, 1 Cal. 2d 61 (1934) ............................1

Johnson v. Avery, 393U.S.483

(1968)................................... / ............... 39

Keenan v. Board of Law Examiners of

the State of N.C. 317 F.Supp.

1350 (D.N.L. 1970) ............................ ‘. . . . .24,29,45

Kinnev v. Lenon, 4 25 F2d 2 09 (9t.h

Cir. 1970) ................ 4 3,4 4

1

2

3

4

5•

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

Konlngsberg ,v. State Bar .of

California , 353 U.S. '252 (1957) ..................... 25,26,39

32,48

Loving v. Commonwealth of Virginia,

388 U.S. 1, (1967) . . . ............... .............. 50

CASES (cont'd) ' PAGE NO.

McDonald v. State Bar of Calif., '

22 Cal. 2d 768 (1943) ........

McLaughlin v. State of Florida,

379 U.S. 184 (1964) ............

March v. Committee of Bar Examiners,

67 C2d 718 (1967) ............

Morrow v.- Crisler, F.Supp. , 4

E.P.D. *ii 7 5 6 3 , No. 4717, Sept. 29,

1971 (S.D. Miss) . . . ........

Mulane v. Central Bank and Trust Co.,

339 U.S. 306 (1950) ............

NAACP v. Alabama, 377 U.S. 288 (1963)

v. Button, 371 U.S. 415 (1962)

1

50

5

8,10,13

38

33

33,40

enn v. Stumpf , 208 F.Supp. 1238

(N.D. Cal. 197 0) .......................*'............. 8

eoplc v. Lamson, 12 F.Supp. 813

(N.D. Cal. 1935), appeal den,

80 F. 2d 388 (9th Cir. 1936)..................... . . . 23

owe 11 v. Alabama, 287 U.S. 45 (1932).................... 43

eston v. State Bar, 28 Cal. 2d 643

(1946) ................................................ 4

rdy & Fitzpatrick v. State of Calif.

' 71 Cal. 2d 566 (1969)................... .............. 10,49

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

15

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

CASES (coni'd) PAGE NO.

Rafaelli v. Committee of Bar Examiners,

S.F. 22841 (May 24, 1972) . . . .

Ratti v. Hjnsdale Raceway Inc. , 2 4 9

A2d 859, 109 N.H. 270* (1969) 25

Reynolds v. Sims, 377 U.S. 533 (1964) . . . . . . . . . . . 39

Rogers v. Alabama, 196 U.S. 226 (1904) ..................... 46

Sabat v. State Bar, 3 Cal. 2d 615

(1935) ..................... ,

Sandoval v. Rattikan, 395 S.W. 2d 889,

(C.Civ.App. Texas, 1965) cert den

385 U.S. 901 (1966) . . . . . . T T .

Serrano v. Priest, 5 Cal. 3rd 615 (1971) . . .............

Shapcro v. Thompson, 394 U.S. 618 (1969) ................

Shelton v. Tucker, 364 U.S. 479 (1961) ...................

Smith v. Texas , 34 S.Ct. 681 (1914) . . . . . . •........

Strauder v. V7. Virginia , 100 U.S. 303

(1880) ................ ..

Swain v. Alabama, 380 U.S. 202 (1965) ................ ..

ichware v. Committee of Bar Examiners 353 U.S. 232 (1957).

Sate v. Short, 491 U.S. 395 (1971)

’akahashi v. Fish and Game Comm1n ,

334 U.S. 410 (1948) . . 7 T T " .

• • •

'raux v. Raich, 239 U.S. 33 (1915)

37

49.

49

32

24,25

46

46

24,26,27

48

49

10

25

Inited Mine Workers v._I111nois State . •

Bar Association , 3 8 9 U.S. 217 (1967)'...................38,39

Ini tod States v. Bd. of Ed._ of City of

Bessemer ',. 39 6 E. 2d 4 4 ('5 th cTr. , 19 68) .............. 7

1

2

3

4

5•

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

CASES (cont'd) PAGE NO.

Westbrook v. Mihaly, 2 Cal. 3rd 765 (1970) ' x

vacated on other grounds, 403 U.S. 915

<1971> ..................................

Western Addition Community Organization v.

Alioto, 330 F.Supp. 536 (N.D. Cal. 19 71) ,

__F.Supp.___ _>• 4 E.P.D. 117663, No. 70-1335,

Feb. 7, 1972 (N.D. Cal). . ‘....................... 8,10,11

19

Williams v. Illinois , 399 U.S. 235 (1970) . . . . ........ 51

Wise v. Southern Pacific Co., Cal. 3rd 600

(19 7O') . . ...........~ ........ ............ .. 38

CONSTITUTIONS, STATUTES and REGULATIONS ' '

Jni^ed States Constitution

Fourteenth Amendment ................................. 1,23,24, . 29,32,36

43,47,48

Sixth Amendment • • • • • ....................... 36,43,47

Fifth Amendment ................................. 36,43,47

First Amendment ................ • ............... n,36

alifornia Constitution

Article I, Section H ........ ........................ 48/49

Article I, Section 13, Clause 6 ....................... 23,29,3236