Henderson v. United States Motion and Brief Amicus Curiae

Public Court Documents

October 17, 1949

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Henderson v. United States Motion and Brief Amicus Curiae, 1949. 344e99f3-b79a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/3745b599-b8b6-4bdb-a436-81ffd9f1f811/henderson-v-united-states-motion-and-brief-amicus-curiae. Accessed February 22, 2026.

Copied!

•j

y

O

lo

n

t

"«■

H

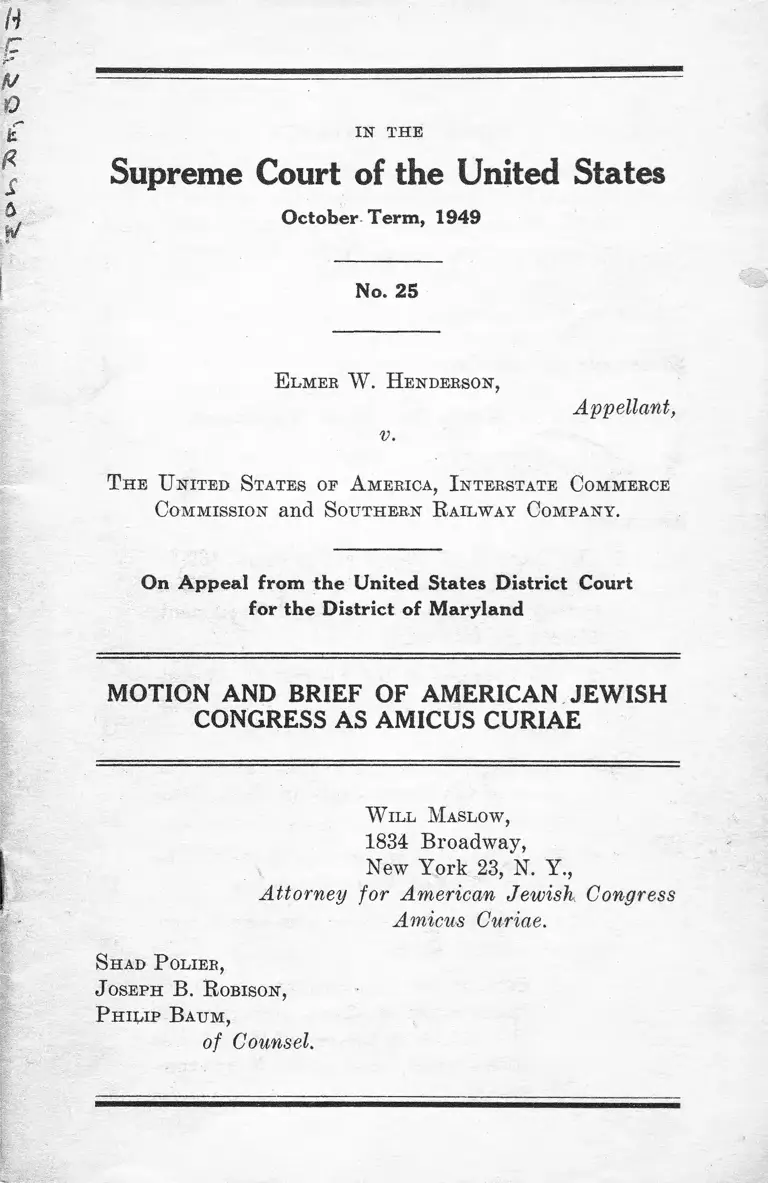

IN THE

Supreme Court of the United States

O ctober Term, 1949

No. 25

E lmer W. H enderson,

v.

Appellant,

T he U nited States oe A merica, I nterstate Commerce

Commission and Southern R ailway Company.

On A ppeal from the U nited States D istrict Court

for the District of M aryland

MOTION AND BRIEF OF AMERICAN JEWISH

CONGRESS AS AMICUS CURIAE

W ill Maslow,

1834 Broadway,

New York 23, N. Y.,

Attorney for American Jewish Congress

Amicus Curiae.

Shad P olier,

J oseph B. R obison,

P hilip Baum,

of Counsel.

TABLE OF CONTENTS

MOTION FOR LEAVE TO FILE ............................ 1

BRIEF .............................................................. 4

Statement op the Case ...................... 4

T he Question to W hich T his Beiep I s Addressed .... 5

Summary op Argument ..................................................... 6

Argument .............................................................................. 8

I. The Doctrine of Plessy v. Ferguson, 163 U.

S. 537, that Separate but Equal Facilities

Satisfy Requirements of Equal Treatment,

Should Be Overruled ................................... 8

A. The Framers of the Fourteenth Amend

ment Intended Thereby to Prohibit Seg

regation ................................................... 11

B. The Legal Principles Which Formed the

Basis of the Plessy Decision Were Erro

neous .............................................. 15

C. The Factual Assumptions Made in the

Plessy Decision Were Erroneous .......... 17

1. Segregated facilities necessarily have

a lower value ..................................... 18

2. Even if the facilities are in all re

spects equal in value, segregation is

discriminatory because of the adverse

effects which it has on the Negro com

munity ................................................ 22

PAGE

11 Index

II. A Eeqnirement of Equality Can Never Be

Satisfied By Segregated Facilities Because

the Official Act of Segregation of Itself

Gives Superior Value to the Facilities As

signed to the Dominant Group .................... 26

A. An Official Policy of Segregation Would

Be Unconstitutional If Maintenance of

Racial Superiority Were Proclaimed as

Its Purpose .............................................. 27

B. The Placing of a Racial or Religious

Group in an Inferior Status by Segrega

tion Can Be Accomplished Without an

Express Declaration of Such Status .... 28

C. The Segregation of Negroes Maintains

an Officially Declared Status of Inferior

ity and Also a Previously Established

Status of Social Inequality ..................... 31

1. Official declarations of inferiority .... 31

2. The previously established social in

equality .............................................. 34

III. The Separate But Equal Doctrine Has

Never Been, and Should Not Now Be, Ap

plied to Section 3(1) of the Interstate Com

merce Act by This Court .............................. 36

CoKaLTrsiOK ....................................................... 37

PAGE

Index iii

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

D ecisions

Anderson v. Pantages Theatre Co., 114 Wash. 24

(1921) .................................................................... 35

Atlanta Journal Co. v. Farmer, 48 Ga. App. 273

(1934) .................................................................... 32

Axton Fisher Tobacco Co. v. Evening Post, 169 Ky.

64 (1916) .............................................................. 36

Bailey v. Alabama, 219 U. S. 219 (1911) ................... 28

Baylies v. Curry, 128 111. 287 (1889) ........................ 35

Bolden v. Grand Rapids Operating Co., 239 Mich.

318 (1927) ............................................................ 35

Buchanan v. Warley, 245 U. S. 60 (1917) .................15,16

Chicago, R. I. and P. Ry. Co. v. Allison, 120 Ark.

54 (1915) .............................................................. 33

Chiles v. Chesapeake & Ohio R. R. Co., 218 U. S.

71 (1909) ........... 36

Clark v. Directors, 24 Iowa 67 (1868) ....................... 35

Collins v. Oklahoma State Hospital, 76 Okla. 229

(1919) .................................................................... 32,33

Connolly v. Union Sewer Pipe Co., 184 U. S. 540

(1902) ......... 15

Connor v. Board of Commissioners of Logan County,

Ohio, 12 F. (2d) 789 (1926) ................................ 28

Councill v. Western & Atlantic R. R. Co., 1 I. C. C.

339 (1887) ............................................................ 8

Crosswaith v. Bergin, 95 Colo. 241 (1934) ................. 35I

Dobbins v. Los Angeles, 195 U. S. 223 (1904) .......... 28

Edwards v. Nashville, C. & St. L. Ry. Co., 12 I. C. C.

247, 249 (1907) ..................................................... 9

PAGE

iv Index

PAGE

Ferguson v. Gies, 83 Mich. 358 (1890) ...................... 35

Flood v. News and Courier Co., 71 S. C. 112 (1905) .. 32

Guinn and Beal v. United States, 238 U. S. 347 (1915) 28

Gulf, Colorado and Santa Fe Railway Co. v. Ellis,

165 U. S. 150 (1897) ................................... ......... 15

Hall v. De Cuir, 95 U. S. 485 (1877) .......................... 36

Hargrove v. Okla. Press. Pub. Co., 130 Okla. 76

(1928) ................................................................... 32

Heard v. Georgia R. R. Co., 1 I. C. C. 428 (1888) .... 8

Henderson v. Mayor, 92 U. S. 259 (1875) ................. 28

Hill v. Texas, 316 U. S. 400 (1942) ............................ 15

Hirabayashi v. U. S., 320 U. S. 81 (1943) ................. 14

Hurd v. Hodge, 334 U. S. 24 (1948) .......................... 13

Jackson v. Seaboard Airline Ry. Co., 269 I. C. C.

399 (1948) ...... ......................................................

Jones v. Kehrlein, 194 P. 55 (Cal., 1920) ...................

Jones v. Polk & Co., 190 Ala. 243 (1913) .................

Joyner v. Moore-Wiggins Co., Ltd., 152 App. Div.

266 (N. Y., 1912) .................................................

Kansas City Southern Railway Co. v. Kaw Yalley

Drainage District, 233 U. S. 75 (1914) ...............

Louisville and N. R. R. Co. v. Ritchel, 148 Ky. 701

(1912) ...................................................................

McCabe v. A., T. & S. F. R, R. Co., 235 U. S. 151

(1914) ...... ............................................................. 36

M. K. T. Railway Co. of Texas v. Ball, 25 Tex. Civ.

App. 500 (1901) ................................................... 33

Mitchell v. United States, 313 U. S. 80 (1941) ............9, 36

Morgan v. Commonwealth of Virginia, 328 U. S. 373

(1946) ................................................................... 16,36

Myers v. Anderson, 238 U. S. 368 (1915) ................... 28

Neal v. Delaware, 103 U. S. 370 (1881) .................... 28

8

35

32

35

16

(

33

Index v

0 ’Connor v. Dallas Cotton Exchange, 153 S. W. 2d

266 (Tex., 1941) ................................................... 33

Oyama v. California, 332 U. S. 633 (1948) ............... 15,19

Penn. Coal Co. v. Mahon, 260 IT. 8. 393 (1922) .......... 28

People v. Board of Education of Detroit, 18 Mich.

400 (1869) ............................................................ 35

Pickett v. Kuchan, 323 111. 138 (1926) ........................ 35

Plessy v. Ferguson, 163 U. S. 537 (1896)......8,10,11,14,

15,17, 27, 34, 37

Poindexter v. Greenhow, 114 U. S. 270 (1884) .......... 28

Prowd v. Gore, 207 P. 490 (Cal., 1922) ....................... 35

Railroad Company v. Brown, 17 Wall. 445 (1873) ...11,37

Randall v. Cowlitz Amusements, 194 Wash. 82 (1938) 35

Roberts v. Boston, 5 Cush. 198 (1850) ...................... 14

Shelley v. Kraemer, 334 U. S. 1 (1948) .............. 15,-16,17

Slaughter House Cases, 83 IT. S. 36 (1872) ............... 12

Southern Railway v. Greene, 216 IT. S. 400 (1910) .... 15

Stamps & Powell v. Louisville & Nashvillq R. R. Co.,

269 I. C. C. 789 (1948) ......................................... 8

State v. McCann, 21 Ohio St. 198 (1872) ................... 14

Strauder v. West Virginia, 100 IT. S. 303, 306 (1879) 31

Stultz v. Cousins, 242 P. 794 (C. C. A. 6th, 1917) .... 32

Takahashi v. Fish & Game Commission, 332 IT. S.

410 (1948) ........................... 15

Tape v. Hurley, 66 Col. 473 (1885) .............................. 35

United States v. Carolene Products, 304 U. S. 144

(1938) 30

Uptown v. Times-Democrat Pub. Co., 104 La. 141

(1900) ..................................................................... 32

Village of Euclid v. Ambler Realty Co., 272 U. S.

365 (1926) ............................................................... 28

PAGE

VI Index

PAGE

Williams v. Riddle, 145 Ky. 459 (1911) .................... 32

Wolfe v. Georgia Railway Electric Co., 2 Ga. App.

499 (1907) .......................................................... 32

Wright v. F. W. Woolworth Co., 281 111. App. 495

(1935) ................................................................... 32

Wysinger v. Crookshank, 23 P. 54 (1890) ................ 85

Yick Wo v. Hopkins, 118 U. S. 356 (1886) ............... 15,28

Statutes

General Laws under the Seventh Legislature of the

State of Texas, Chapter 121 ...............................

Laws Passed by First Legislature of the State of

Texas, An Act to Regulate Proceedings in a

District Court, Section 65 ...................................

Laws Passed by the First Legislature of the State

of Texas, An Act to Provide for the Enumera

tion of the Inhabitants ......................................

Polizeiverordnung ueber die Kennzeichnung der

Juden vom 1 September 1941, RGB I, I. S. 547,

Ausgeg. am 5. IX. 1941 ................................ ......

14 Stat. 27 ...................................................................

49 IT. S. C. A. 3(1) .....................................................

M iscellaneous

Bond, Education of the Negro in the American Social

Order (1934) ....................................................... 17

Congressional Globe, 39th Congress, First Session .... 12

Congressional Globe, 42nd Congress, Second Ses

sion .......................................................................13,14

2 Cong. Rec. 3452 (43rd Cong., 1st Sess.) ............... 14

Davis and Dollard, Children of Bondage (1940) .... 17, 20

31

1|

31

31

21

13

8, 37

Index Vll

PAGE

Deutscher and Chein, The Psychological Effect of

Enforced Segregation: A Survey of Social Sci

ence Opinion, 26 The Journal of Psychology, 259

(1948) ............................................................ 22, 23,26

Dollard, Caste and Class in a Southern Town (1937) .-225* 85

Doyle, The Etiquette of Race Relations (1937) ........ 19

Du Bois, Dusk of Dawn (1940) ................................. 24

Du Bois, Black Reconstruction (1935) ...................... 24

Gallagher, American Caste and the Negro College

(1938) ................................................................... 17

Is Racial Segregation Consistent With Equal Pro

tection of the Laws! 49 Columbia L. R. 629;

(1949) ................................................................... 11

Jenkins, Pro-Slavery Thought in the Old South

(1935) ................................................................... 21

Johnson, The Autobiography of an Ex-Colored Man

(1927) ................................................................... 24

Johnson, Patterns of Negro Segregation (1943)......19*20,

24,34

Mangum, The Legal Status of the Negro (1940) ...... 32

McGovney, Racial Residential Segregation by State

Court Enforcement of Restrictive Agreements,

Covenants or Conditions in Deeds Is Unconsti

tutional, 33 Calif. Law. Rev. 5 (1945) ............... 35

McPherson, Political History of the United States

During the Reconstruction (1875) .................... 12

McWilliams, Race Discrimination and the Law, Sci

ence and Society, Vol. IX, No. 1 (1945) ...... ....... 34

Moton, What the Negro Thinks (1929) .................... 1J, 20

Myrdal, An American Dilemma (1944) .................... 24, 34

Reid, Southern Ways, Survey Graphic (Jan., 1947) 24

Report of the President’s Committee on Civil Rights,

To Secure These Rights (1947) .......................... 11,30

V1U Index

PAGE

Restrictive Covenants and Equal Protection — The

New Rule in Shelley’s Case, 21 So. Cal. L. R.

358 (1948) ..........................................................J S p f

Segregation in the Public Schools—A Violation of

“ Equal Protection”, 50 Yale L. J. 1059 (1947) lV

Stone, The Common Law in the United States, 50 1

Harvard L. R. 4 (1936) ...................................... 28

Stouffer, Studies in Social Psychology in World War

II, Volume I (1949) ............................................ 20;

Tuck, Not with the Fist (1946) ................................ 24;

Woof ter, The Basis of Racial Adjustment (1925) .... 17

I|

IN THE

Supreme Court of the United States

O ctober Term, 1949

No. 25

E lmer W. H enderson,

v.

Appellant,

T he U nited States of A merica, I nterstate Commerce

Commission and Southern Railway Company.

On A ppeal from th e U nited States D istrict Court

for the District of M aryland

MOTION OF AMERICAN JEWISH CONGRESS

FOR LEAVE TO FILE BRIEF AS AMICUS CURIAE

To the Honorable, the Chief Justice of the United States

and the Associate Justices of the Supreme Court of

•the United States:

The undersigned, as counsel for the American Jewish

Congress and on its behalf, respectfully moves this Court

for leave to file the accompanying brief as amicus curiae.

The American Jewish Congress is an organization

committed to the principle that the destinies of all Ameri

cans are indissolubly linked and that any act which un

2

justly injures one group necessarily injures all. Out of

this firmly held belief, the American Jewish Congress

created its Commission On Law and Social Action in 1945

in part “ To fight every manifestation of racism and to

promote the civil and political equality of all minorities

in America.”

Believing as we do that Jewish interests are insepara

ble from the interests of justice, the American Jewish

Congress cannot remain impassive or disinterested when

persecution, discrimination or humiliation is inflicted upon

any human being because of his race, religion, color,

national origin or ancestry. Through the thousands of

years of our tragic history we have learned one lesson

well: the persecution at any time of any minority portends

the shape and intensity of persecution of all minorities.

There is, moreover, an additional reason for our interest.

The special concern of the Jewish people in human rights

derives from an immemorial tradition which proclaims

the common origin and end of all mankind and affirms,

under the highest sanction of faith and human aspirations,

the common and inalienable rights of all men. The strug

gle for human dignity and liberty is thus of the very sub

stance of the Jewish tradition.

We submit this brief amicus because we are convinced

that the policy of segregation has had a blighting effect

upon Americans and consequently upon American demo

cratic institutions. We believe that the doctrine of “ sepa

rate but equal” has engendered hatred, fear and igno

rance. We recognize in this triumvirate our greatest

enemy in the struggle for human freedom. But our con

cern must not be construed as limited to minorities alone.

The treatment of minorities in a community is indica

tive of its political and moral standards and ultimately

determinative of the happiness of all its members. Our

immediate objective here is to secure unconditional equal

3

ity for Americans of Negro ancestry. Our ultimate objec

tive in this case, as in all others, is to preserve intact the

dignity of all men.

We have sought the consent of counsel for the four

parties to the filing of this brief. Counsel for appellant,

the United States and the Interstate Commerce Commis

sion have consented. Counsel for the Southern Railway

Company has refused consent.

Dated, New York, New York, October 17, 1949.

W ill. Maslow,

Attorney for American Jewish Congress.

IN TH E

Supreme Court of the United States

O ctober Term, 1949

No. 25

E lmer W. H enderson,

v.

Appellant,

T he U nited States o f A merica, I nterstate Commerce

Commission and Southern Bailway Company.

On A ppeal from the U nited States District Court

for the D istrict of M aryland

BRIEF OF AMERICAN JEW ISH CONGRESS

AS AMICUS CURIAE

The American Jewish Congress respectfully submits

this brief, as amicus curiae, in support of appellant. Our

interest in the issues raised by this case is set forth in

the motion for leave to file annexed hereto.

Statement of the Case

This proceeding originally arose out of the refusal of

the Southern Bailway, on May 17, 1942, to serve appellant,

a Negro, in one of its dining cars. The various steps in

the subsequent proceedings are fully set forth in the

[ 4 ]

5

appellant’s brief. Because the railroad subsequently

changed its rules, the issue presently before this Court

is sufficiently revealed by the following facts:

The railroad’s most recent rules, effective March 1,

1946, provide that, after certain structural changes are

made in its diners, one of the thirteen tables in each diner

will be reserved absolutely for Negroes, and will be sep

arated from the rest of the car by a five-foot partition.

No white passengers will be served at this one table and

no Negro passengers will be served at the other twelve

tables.

On September 5, 1947, the Interstate Commerce Com

mission held that this rule satisfied Section 3(1) of the

Interstate Commerce Act. Henderson v. Southern Rail

way, 269 I. C. C. 73. That decision was upheld by a

three-judge District Court (Henderson v. Southern Rail

way, 80 F. Supp. 32, D. C. Md., 1948), Judge Soper dis

senting, and the present appeal is from the decision of

that Court.

The Question to Which this Brief Is Addressed

This brief is addressed solely to the question whether

the requirements of equality contained in either the Fifth

and Fourteenth Amendments to the United States Con

stitution or Section 3(1) of the Interstate Commerce Act,

49 U. S. C. 3(1), are satisfied by affording “ separate but

equal” facilities to Negro and white passengers on inter

state railroads.

6

Summary of Argument

I. In holding that a requirement of equal treatment v

can be satisfied by providing segregated facilities, the

decision in Plessy v. Ferguson was wrong historically,

legally and factually.

A. The Court erred historically in finding that

the Fourteenth Amendment was not “ intended to

abolish distinctions based on color,” <2 j

y 4 t* % £ Jt h $ w#

B. The Court erred as a matter of law in holding

that segregation laws could be sustained either as an

exercise of the police power or on the theory that

physically equal facilities were necessarily equal in

the Constitutional sense.

C. Assuming that segregated facilities can be

equal, the Court erred as a matter of fact in conclud

ing that officially imposed segregation does not place

a badge of inferiority on the Negro race.

(1) Segregated facilities necessarily have an

inferior value if they are assigned to a group in

the community which the dominant group regards

as inferior. In determining the value of a particu

lar piece of property, the law examines not only

its physical characteristics but also any other in

tangible factors which are given weight by the com

munity at large. When the facilities are used ex

clusively by a group which the community regards

as inferior, they become inferior in value.

(2) Even if the facilities are in all respects

equal in value, segregation is discriminatory be

cause of the adverse effect which it has on the

Negro community. Recent studies reveal unanim

ity of opinion among students of race relations

that segregation causes psychological damage to the

individual members of the Negro community which

they would be spared if segregation were not im

posed.

II. A requirement of equality can never be satisfied

by segregated facilities because the official act of segrega

tion of itself gives superior value to the facilities assigned

to the dominant group,

A. An official policy of segregation would unques

tionably be unconstitutional if the official body which

imposed it simultaneously proclaimed that mainte

nance of racial superiority was its purpose. '

B. The ̂placing of a racial or religious group m

inferior status by segregation can be accomplished

without such an express declaration of status. Other

wise it would be easy to evade the constitutional

restraint. The implicit declaration of inferiority can

be made either in other official acts or by incorporat

ing in the segregation policy a previously existing

social stratification.

C. The segregation of Negroes does in fact main

tain an officially declared status of inferiority as well

as a previously established status of social inequality.

(1) Official declarations of inferiority are found

in various statutes and in judicial decisions holding,

for example, that it is libelous per se to call a. white

man a Negro and that a white man required to ride

in a Negro coach may recover damages.

(2) The previously established social inequality

is shown by the unanimous findings of students of

race relations.

8

HI. The separate but equal doctrine has never been,

and should not now be, applied to Section 3(1) of the

Interstate Commerce Act by this Court. This case can be

decided in favor of appellant without overruling the hold

ing in Plessy v. Ferguson that segregated facilities may

be provided without violating the Fourteenth Amendment.

A R G U M E N T

POINT I

The doctrine of Plessy v. Ferguson, 163 U. S. 537,

that separate but equal facilities satisfy requirements

of equal treatment, should be overruled.

Subsection 1 of Section 3 of the Interstate Commerce

Act provides that:

“ It shall be unlawful for any common carrier sub

ject to the provisions of this chapter to make or give

any undue or unreasonable preference or advantage

to any particular person, company, firm, corporation,

or locality, or any particular description of traffic, in

any respect whatsoever, or to subject any particular

person, company, firm, corporation, or locality, or any

particular description of traffic, to any undue or un

reasonable prejudice or disadvantage in any respect

whatsoever.”

Since the question was first raised, the Interstate

Commerce Commission has consistently held that this pro

vision forbids discrimination against Negro passengers

because of their race. Coimcill v. Western db Atlantic R.

R. Co., 1 I. C. C. 339; Heard v. Georgia R. R. Co., 1 I. C.

C. 428; Jackson v. Seaboard Air Line Ry. Co., 269 I. C. C.

399 ; Stamps db Powell v. Louisville do Nashville R. R. Co.,

9

269 I. C. C. 789. See also Mitchell v. United States, 313

U. S. 80, 95. In Edwards v. Nashville, C. & St. L. By. Co.,

12 I. C. C. 247, 249, the principle was thns stated:

“ If a railroad provides certain facilities and ac

commodations for first-class passengers of the white

race, it is commanded by the law that like accommo

dations shall be provided for colored passengers of

the same class. The principle that mnst govern is

that carriers mnst serve equally well all passengers,

whether white or colored, paying the same fare. Fail

ure to do this is discrimination and subjects the

passenger to 'undue and unreasonable prejudice and

disadvantage.’ ”

Section 3(1) of the I. C. C. Act, however, is not the

only prohibition of discrimination which has been invoked

here. The United States Government, in its brief as a

party to this case, suggests that the Fifth Amendment to

the United States Constitution also applies because the

alleged discrimination was approved by an agency of the

Federal Government, the I. C. C. (U. S. Brief, pp. 14-15).

We agree. Indeed, the Court below itself recognized

that the railroad’s regulations were “ directly approved

by” the I. C. C., and hence “ are to be treated, for the

purposes of this case, as in effect the Commission’s rules.”

63 F. Supp., at page 914.

We suggest further, however, that the equal protection

clause of the Fourteenth Amendment also applies. Bail-

roads enjoy a monopolistic position protected by both the

State and Federal governments. We believe that any

such governmentally protected monopoly is forbidden by

the Constitution from engaging in racial discrimination.

It is true that this Court has never so held but that is

only because virtually all such monopolies are subject to

common law or statutory prohibitions of discrimination.

It is unthinkable that, if these prohibitions were removed

by statute, a railroad could refuse to serve any passenger

solely because of race.

10

We shall not elaborate on these points because this

brief is restricted to a single question which is common to

all these prohibitions of discrimination; namely, whether

they are satisfied when “ separate but equal” facilities

are offered. In the Plessy ease, this Court held that they

were, at least with respect to the Fourteenth Amendment.

While the present ease can probably be decided without

overruling the Plessy case, as we show below, the factual

premises and legal conclusions of that decision can not

be ignored altogether. We turn first, therefore, to an

examination of those premises and conclusions.

The result in the Plessy case rested on what we believe

to have been a series of errors. First, the Court made

the startling assumption that “ in the nature of things it

[the Fourteenth Amendment] could not have been in

tended to abolish distinctions based on color” (162 II. 8.,

at 544). We show below that this statement is histori

cally false (pp. 10-14). The Court then held that seg

regation could be legally justified as an exercise of the

police power or on the ground that the facilities offered

are in fact equal and thus satisfy the constitutional require

ment of equality. We discuss this argument at pages

15-16. Finally, the Court recognized that the require

ment of equality could not be satisfied by a system of

segregation which created or maintained inequality. The

Court declared that “ Every exercise of the police power

must be reasonable and extend only to such laws as are

enacted in good faith and for the promotion of the public

good and not for the annoyance or oppression of a par

ticular group.” 163 U. S., at 550. In finding, however,

that a law requiring segregation on railways was consti

tutional, it made the factual and sociological assumption

that such segregation would “ not necessarily imply the

inferiority of either race to the other.” Id., at 544. We

show below (pp. 17-26) that this assumption has been

exploded in the 50 years which have elapsed since it was

made.

11

The net effect of the Plessy decision was to measure

the constitutional command of equality mechanically in

terms of physical dimensions and quantity. As a result

it has infused rigid, caste stratifications into our laws, our

institutions, our conduct and our habits of perception

until “ the Negro is segregated in public thought as well

as public carriers.” Moton, What the Negro Thinks,

1929, page 55. We submit that what the President’s Com

mittee on Civil Eights called “ the ‘separate but equal’

failure” (Report, To Secure These Rights, 1947, p. 79)

should be reexamined by this Court and that Plessy v.

Ferguson should be overruled.

A. T h e F ram ers of th e F o u rteen th A m en d m en t In ten d ed

T h e reb y to P ro h ib it S eg reg atio n

Plessy v. Ferguson cannot be squared with the temper

and philosophy of the 1860’s which created the Fourteenth

Amendment. See Note, Is Racial Segregation Consistent

With Equal Protection of the Laws f 49 Columbia L. E. 629.

It is in fundamental conflict, for example, with Railroad

Co. v. Brown, 17 Wall. 445. In that case, Brown, a Negro,

sued for damages for exclusion from a railroad car in

the District of Columbia. The Federal statute, 12 Stat.

805, enacted in 1863, in the midst of the Civil War, author

ized the railroad to operate and provided that “ no person

shall be excluded from the cars on account of color.” The

railroad ran two identical cars on a train, one for Negroes

and the other, from which it excluded Brown, for whites.

The trial Court specifically refused to instruct, as the rail

road requested, that if the cars were “ really safe, clean

and comfortable,” the railroad should prevail. In the

trial court the plaintiff was awarded substantial damages

for the exclusion. This Court affirmed, terming the segre

gation “ an ingenious attempt to evade compliance with

the obvious meaning of the requirement.” It held that

12

to force Negro passengers into separate cars was dis

crimination incompatible with the equality demanded by

Congress. Thus, this Court held that separate but equal

accommodations have the same legal effeet as the total

exclusion of Negroes from transportation.

That those responsible for the enactment of the Four

teenth Amendment rejected segregation was further evi

denced by the passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1866.

Like the Amendment itself, this Act was designed to

eliminate the distinctions contained in the Black Codes

passed by the Southern State governments during the

post-Appomattox months of 1865. Slaughter House Cases,

83 U. S. 36, 70. These codes, among other provisions,

placed limitations on Negro rights to own property, to

institute law suits or to testify in any proceedings. They

applied greatly different penalties to Negroes than to

whites for the same offenses. See McPherson, Political

History of the United States During Reconstruction,

Chapter 4. To prevent these distinctions, a civil rights

bill was introduced forbidding these and related practices

and forbidding also, in a general phrase, any discrimina

tion as to civil rights. S. 61, 39th Congress, First Session.

Senator Howard, who had participated in drafting the

Thirteenth Amendment, supported the bill, declaring that

“ in respect to all civil rights, there is to be thereafter

no distinction between the white race and black race.”

Congressional Globe, 39th Congress, First Session, 504.

Senator Trumbull, who introduced the civil rights bill,

asserted “ * * * the very object of the bill is to break

down all discrimination between the black men and white

men.” Ibid., page 599. The bill passed the Senate but

ran into difficulties in the House, partly because it was

felt that “ civil rights” encompassed a scope too broad to

be supported by the Thirteenth Amendment. The final

bill, therefore, was limited to the elimination of the named

abuses with the general and vague reference to civil rights

13

omitted. 14 Stat. 27. The significance of this statute, in

the interpretation of the Fourteenth Amendment, has re

cently been described by this Court (Hurd v. Hodge, 334

U. S. 24, 32, footnotes omitted):

“ Both the Civil Bights Act of 1866 and the joint

resolution which was later adopted as the Fourteenth

Amendment were passed in the first session of the

Thirty-Ninth Congress. Frequent references to the

Civil Rights Act are to be found in the record of the

legislative debates on the adoption of the Amendment.

It is clear that in many significant respects the statute

and the Amendment were expressions of the same

general congressional policy.”

Alm o st immediately following ratification of the Four

teenth Amendment and pursuant to the grant of authority

contained in its fifth section, Senator Sumner of Massa

chusetts introduced a proposal expanding and articulating

the rights implicit in the new amendment. During argu

ment on this hill, which later became the Civil Bights Act

of 1875, Sumner enunciated his attitude toward racial

segregation. He spoke as one of the leaders who had

achieved the passage of the Fourteenth Amendment and

who might be supposed to know it best; he was supported

by what he believed was the unavoidable intention of the

Amendment. Sumner lashed out at what he called the

“ excuse, which finds Equality in separation” by declaring

(Cong. Globe, 42nd Cong., 2nd Sess., 382-383):

“ Separate hotels, separate conveyances, separate

theaters, separate schools, separate institutions of

learning and science, separate churches, and separate

cemeteries — these are the artificial substitutes for

Equality; and this is the contrivance by which a

transcendent right, involving a transcendent duty, is

evaded. * * * Assuming what is most absurd to as

14

sume, and what is contradicted by all experience, that

a substitute can be an equivalent, it is so in form only

and not in reality. Every such attempt is an indig

nity to the colored race, instinct with the spirit of

Slavery, and this decides its character. It is Slavery

in its last appearance.”

In the debates which ensued, Sumner’s views were

upheld and the leading cases on which this Court subse

quently relied in Plessy v. Ferguson, although pressed

upon Congress, were rejected as unsound. Roberts v.

Boston, 5 Cush. 198 (1850), and State v. McCann, 21 Ohio

St. 198 (1872), both of which defend segregation prac

tices, were mentioned by name and expressly refuted. See

Congressional Globe, 42nd Cong., 2nd Sess,, at 3261, and

2 Congressional Eecord 3452 (43 Cong., 1st Sess.). Yet,

in concluding that, “ in the nature of things,” the Four

teenth Amendment was not “ intended to abolish distinc

tions based upon color” (163 U. S., at 544) this Court

explicitly relied upon the Roberts case!

Nor may the Plessy theory that the Fourteenth Amend

ment was not intended to abolish race distinctions be

squared with the recent decisions of this Court. In

Sirabayashi v. U. S., 320 IT. S. 81, 100 (1947), it was

said:

“ Distinctions between citizens solely because of

their ancestry are by their very nature odious to a

free people whose institutions are founded upon the

doctrine of equality. For that reason, legislative

classification or discrimination based on race alone

has often been held to be a denial of equal protec

tion.”

Except for the decisions which rely uncritically upon

Plessy v. Ferguson, this Court has consistently maintained

that the Fourteenth Amendment prevents States from

15

establishing racial distinctions as a basis for general

classifications. Takahashi v. Fish <0 Game Commission,

332 U. S. 410, 420; Oyama v, California, 332 II. S. 633,

640, 646; Shelley v. Kraemer, 334 U. S. 1, 20, 23; Tick Wo

v. Hopkins, 118 U. S. 356, 373, 374; Buchanan v. Warley,

245 U. S. 60, 82; Hill v. Texas, 316 U. S. 400, 404. These

cases merely embody the basic constitutional principle

applicable in all other areas that governmental classifica

tions must be based upon a significant difference having

a reasonable relationship to the subject matter of the

statute. Southern Railway Co. v. Greene, 216 U. S, 400,

417; Gulf, Colorado <0 Santa Fe Railway Co. v. Ellis, 165

U. S. 150, 155; Connolly v. Union Sewer Pipe Co., 184 U.

S. 540, 559, 560.

More specifically, the Plessy segregation principle can

not be squared with Buchanan v. Warley, supra, and

Shelley v. Kraemer, supra, in both of which this Court

refused to apply the separate but equal doctrine to hous

ing. It did so not on the theory that land and houses are

sui generis, but on the broad ground that “ equal protec

tion of the law is not achieved through the indiscriminate

imposition of inequalities.” Shelley case, 334 U. S., at 22.

This terse holding, as has been cogently argued, com

pletely destroys the basis of the Plessy decision. Restric

tive Covenants and Equal Protection—The New Rule in

Shelley’s Case, 21 So. Cal. L. R. 358 (1948).

B. T h e L egal P rin c ip les W h ich F o rm ed th e Basis of

th e P lessy D ecision W ere E rroneous

The Plessy decision sought to justify state segregation

statutes both as exercises of the police power and on the

theory that, since they restricted all races alike, they sat

isfied the constitutional requirement of equality (163 U.

S., at 544, 546). Neither theory bears examination today.

Particularly vulnerable is what this Court recently

called the “ convenient apologetics of the police power.”

16

Morgan v. Virginia, 328 U. S. 373, 380, citing Kansas

City Southern Railway Co. v. Kaw Valley Drainage Dis

trict, 233 U. S. 75, 79. In Buchanan v. Warley this Court

said (245 U. S., at 74): . . the police power, broad

as it is, cannot justify the passage of a law or ordinance

which runs counter to the limitations of the Federal Con

stitution . . . ” See also Shelley v. Kraemer, 334 II. S.,

at 21.

With the elimination of the police power, the Plessy

doctrine must rest on the sole groun that segregation

operates with equal stringency on the groups doing the

segregating as well as the groups being segregated. In

deed, it has been noted that “ the inclusion of both bases

in a single sentence [in the Plessy opinion] leads one to

wonder whether Mr. Justice Brown ever intended to

enunciate the police power basis as an independent propo

sition sufficient alone to support the statute or whether

the basis under which the statute was upheld as a valid

exercise of the police power did not rest on the conclusion

that the statute did in fact operate equally on all races.”

Note, 21 So. Cal. L. It. 358, 369.

This same article goes on to observe:

“ Despite Mr. Justice Brown’s allusion to the State

police power, subsequent decisions of the Court

clearly indicated that it was the fact of equality of

application upon which it would rely. The question

next arose with respect to the Oklahoma ‘Separate

Coach Case. ’ There the statute, in addition to impos

ing the requirement of equal but separate accommo

dations for Negroes and whites, provided that the

carrier might maintain sleeping and dining cars for

white passengers and not for Negroes, if there should

not be sufficient demand for such facilities by Negroes

to make their maintenance practicable. The Court

upheld the statute insofar as it provided for segrega

tion into equal accommodations, but held that the

17

statute could not authorize discrimination in the

maintenance of luxury facilities, since the discrimina

tion could be maintained only if it applied equally to

all races. Again, equality of application was made

the sine qua non of validity, without reference to any

reasonable police power basis.”

But the “ equality” theory has also been destroyed by

recent decisions by this Court. In particular, it runs afoul

of the statement in the Shelley case that equality is not

achieved by “ indiscriminate imposition of inequalities”

(supra, p. 15). If this obvious principle is consistently

applied, the Plessy doctrine must fall.

C. T he Factual Assum ptions M ade in th e P lessy

D ecision W ere Erroneous

The Plessy decision itself recognized that segregation

would be unconstitutional if it was designed to or did

create a caste system. However, it made the basic factual

assumption that it was a “ fallacy [to assume] that the

enforced separation of the two races stamps the colored

race with a badge of inferiority” (163 U. S., at 551).

The best that can be said for this statement is that it

was handed down over fifty years ago at a time when the

results of applying the separate but equal doctrine could

only be surmised. In the ensuing decades, the failure of

that prediction has become manifest. If proof of this

were necessary, it has been supplied by the developed

techniques of the social scientists, all of whom are agreed

that segregation has profoundly adverse effects on the

Negro community. Segregation In Public Schools — A

Violation of “Equal Protection,’’ 50 Yale L. J. 1059, 1061;

Gallagher, American Caste and the Negro College (1938);

Davis and Dollard, Children of Bondage, 1940; Woofter,

The Basis of Racial Adjustment (1925); Bond, The Edu-

18

cation of the Negro in the Americcm Social Order (1934).

Surely this Court cannot continue to extend judicial ap

proval to a notion which has been thoroughly discredited

in that laboratory which is the nation itself.

(1) Segregated F acilities Necessabily H ave

a L ower Value

In other areas less controversial and perhaps less sig

nificant, our legal system has recognized that mere iden

tity of physical facilities does not necessarily amount to

equality either in the economic, political or legal sense.

The law would not hold, for example, that an estate has

been divided equally between two children each receiving

one of the two identical houses comprising the estate, if

one of the houses were located in a busy banking district

and the other 50 miles from the nearest railroad station.

The result would be the same even if the two identical

houses were located on the same street opposite each

other, but if, for some reason, one side of that street were

fashionable and sought after, the other neglected and re

jected. Equality is determined in fact and in law not by

the physical identity of things assigned in ownership, use

or enjoyment but by the identity or substantial similarity

of their value.

These legal principles apply not only to property 'Jm,

rights but also to political and civil rights. American law

demands, in the enjoyment by persons of government-

furnished facilities, an equality not less real and substan

tial than the one it exacts for the protection of heirs,

partners or stockholders. “ In approaching cases, such as

this one, in which federal constitutional rights are as

serted, it is incumbent on us to inquire not merely whether

those rights have been denied in express terms, but also

whether they have been denied in substance and effect.

We must review independently both the legal issues and

those factual matters with which they are commingled ’ “

19

(Oyama v. California, 332 U. S. 633). In calling for

“ equal protection”, or for “ equal facilities”, or for the

outlawing of “ undue or unreasonable prejudices or dis

advantages” , the Constitution and the laws of the United

States call for genuine equality of protection and not for

a merely formal or physical identity of treatment.

The important factors to be considered in assessing

the equality of the treatment accorded various groups in

our society are the ideas or expectations which are stimu

lated by that treatment, and the conception conveyed to

each minority of the role it is being called upon to play.

It is undeniably true that in the South, when the Negro

was considered chattel property, any relation of the most

intimate degree between white and Negro could be entered

into with impunity. Even today Negro servants still may

approach as close as necessary to the white persons being

served without untoward social consequence. Yet it is

equally true that merely “ shaking a black hand may be

very repulsive to a white man if he surmises that the

colored man conceives of the situation as implying equal

ity.” Johnson, Patterns of Negro Segregation, 1943, page

208. Clearly it is the social definition of the situation that

accounts for the difference. Those who insist upon the

caste system in our society freely and unstintingly agree

to the ritual of equal physical facilities so long as some

how there is also an accompanying communication that

inferiors are to remain inferiors.

Segregation provides the ready vocabulary for that

communication. It is a vocabulary effectively understood

by all. Segregation provides a graphic and literal re

sponse to the demand of the white world that Negroes be

kept “ in their place.” To the whites the enforced sepa

ration of races is clearly understood as a symbolic affirma

tion of white dominance, dominance which, to keep itself

alive, demands as tribute the continuous performance of

the racial etiquette. See Doyle, The Etiquette of Race

20

Relations (1937). Similarly, Negroes appreciate the im

plications of segregation (Stouffer, Studies in Social Psy

chology in World War 11, Vol. 1, p. 566), resent its slur

(Moton, supra, pp. 238-239), and resist it as a none too

subtle mechanism for anchoring them in inferiority (Davis

and Dollard, Children of Bondage [1940], p. 245).

A Southern attorney has observed of Negroes, “ I

don’t object to their having nice things, but they would

not be satisfied with the finest theatre in the world . . .

They don’t want things for themselves.” Johnson, op.

cit., supra, at page 217. This is, of course, both accurate

and perceptive. Negroes desire access to the world of all,

not to one just as good.

It is, therefore, easy to understand the general belief

in both the white and Negro communities that the facili

ties relegated to the segregated group are made inferior

by the very act of separation. We have long known that

the value and desirability of many objects, facilities, traits

or characteristics may depend not so much upon their

intrinsic qualities or defects, advantages or shortcomings

as upon their association with, or use by, persons enjoying

a certain reputation. The desirability of a beautiful re

sort may be lessened by its being visited by people deemed

of “ low” social standing. If a group considered “ infe

rior” by the prevailing community sentiment adopts any

given color of garment, accent of speech, or place of

amusement, that color, accent or place will automatically

be shunned by the majority and become less desirable or

valuable.

If the Nazis, while proclaiming the essential inferiority

of the “ Jewish Race”, had compelled Jews to wear clothes

of one color while reserving another to the master race,

it could not have been said that Jews received equal cloth

ing facilities. Nor would the discriminatory and humiliat

ing character of the measure depend on whether the colors

were brown for the Jews and black for the others, or vice

21

versa. The exclusive allocation of a given color, any

color, to a race declared “ inferior” would make that color

less desirable. The inferiority thus transmitted from the

wearer to the garment would destroy the genuine “ equal

ity” of the furnished facilities. The Nazis understood

this fully; they achieved much the same effect when they

imposed on Jews the wearing- of the Yellow Star of David.

Polizei-verordnung uber die Kennseichnung der Juden

vom 1., September, 1941, RGBI, I. S. 547, Ausgeg. am 5.

IX. 1941.

We do not agree that the physical facilities furnished

segregated groups are ever in fact equal (infra, pp. 29-30).

But even assuming, arguendo, that those enforcing the

segregation policy were lavish in their expenditures, they

would not thereby attain real equality of treatment. The

five-foot partition in the present case dividing the dining

car into Negro and white portions serves a more funda

mental purpose than the mere physical separation of white

from Negro and the elimination of any likelihood of phys

ical contact. It serves as a ceremonial separation of the

dominant from the subordinate and it marks the outside

limits beyond which tolerance is impermissible. Under

these circumstances the quality of the silverware, glass

ware, or linen becomes irrelevant. Separation stamps the

trappings of equality with the unmistakable sign of infe

riority.

In sum, segregation is the artifice by which a dominant

group assures itself of its own worth by insisting on the

inferiority of others. Segregation, like slavery, has as

its function “ the fact that it raises white men to the same

general level, that it dignifies and exalts every white man

by the presence of a lower race” . Jefferson Davis, quoted

in Jenkins, Pro-Slavery Thought in the Old South (1935),

at page 192.

22

(2) E ven ip the F acilities Abe in All Respects E qual

in Value, Segregation I s Discriminatory B ecause op

the Adverse E ffects W hich I t H as O n the Negro

Community

The unconstitutional inequality of segregation may he

shown without reference at all to the facilities provided.

The inequality appears in the depressing effect which it

has on the individual members of the Negro community.

A survey of professional sociological, anthropological

and psychological opinion on this subject has been con

ducted by Drs. Max Deutscher and Isadore Chein of the

Commission on Community Interrelations of the Ameri

can Jewish Congress. Eight hundred and forty-nine

social scientists were polled, including the entire member

ship of the American Ethnological Society, the Division

of Personality and Social Psychology of the American

Psychological Association, and all of the members of the

American Sociological Society who listed race relations

or social psychology as their major field of interest. Re

turns were received from 517, or 61% of the number sent.

90% of the respondents indicated their opinion that en

forced segregation has detrimental psychological effects

on segregated groups even though equal facilities are

provided. 4% failed to answer the item and only 2% indi

cated that segregation is free of such detrimental effects.

Deutscher and Chein, The Psychological Effects of En

forced Segregation: A Survey of Social Science Opinion,

26 The Journal of Psychology 259 (1948).

On the basis of what they have seen and know, these

social scientists united in rejecting the separate but equal

doctrine as a serviceable formula. In responding, many

of them amplified their answers with additional comment.

Those who conducted the survey remark that “ the gist

of these comments was the emphasis on the essential

irrelevance of the physical attributes of the facilities fur-

23

nished” . Deutscher and Chein op. tit., supra, at page

280. The comments are quoted extensively in the article.

The detrimental psychological effect is not hard to ex

plain. Bearing the approval of this Court, the “ separate

but equal” doctrine has supplied the rationale for a de

tailed and exhaustive oppression of the Negro population

of the South. Dr. Reid has shown that where racial seg

regation is established:

“ . . . every aspect of life is regulated by the laws

on race and color. From birth through education and

marriage to death and burial there are rules and reg

ulations saying that you are born ‘ white ’ or ‘ colored ’;

that you may be educated, if colored, in a school sys

tem separated on the basis of race and ‘as nearly

uniform as possible’ with that available for whites;

that you may marry a person of your choice only if

that person is colored, this being the only celebration

of marriage a colored minister of the gospel may per

form; and that when you die (in Atlanta, at least)

you may not be buried in a cemetery where whites are

interred.

“ But that isn’t all. Between birth and death col

ored persons find that the law decrees that they shall

be separated from white persons on all forms of

transportation, in hotels or inns, eating places, at

places of recreation or amusement, on the tax books,

as voters, in their homes, and in many occupations.

“ To be specific, it is a punishable offense in

Georgia for a barber shop to serve both white and

colored persons, or for Negro barbers to serve white

women or girls; to bury a colored person in a ceme

tery in which white people are buried; to serve both

white and colored persons in the same restaurants

within the same room, or anywhere under the same

license. Restaurants are required to display signs

reading Licensed to serve white people only, or

24

Licensed to serve colored people only. The law also

declares that wine and beer may not be served to

white and colored persons ‘within the same room at

any time’. Taxis must he marked For White Passen

gers Only, or For Colored Passengers Only. There

must be white drivers for carrying white passengers

and colored drivers for carrying colored passengers”

(Ira de A. Reid, Southern Ways, Survey Graphic,

Jan. 1947, p. 39).

Dr. Reid’s list, of course, is not exhaustive. See, for

example, the first six chapters of Johnson, op cit., supra.

Myrdal asserts that no one can yet estimate the extent

of discriminatory practices in the United States. Myrdal,

An American Dilemma (1944), at 1359.

This carefully contrived web of deprivation and dis

tinction confronts the Negro at every turn. The “ thou

sand and one precepts, etiquettes, taboos and disabilities

[which] * * * express the subordinate status of the Negro

people and the exalted positions of the whites” (Myrdal,

op. cit., supra, 66) have a shattering effect upon the Negro

personality. DuBois, Dusk of Dawn (1940), pages 130-

131. “ The Negro in America and in general is an average

and ordinary human being who under a given environment

develops like other human beings.” Black Reconstruction

(1935), Foreword. He is, therefore, understandably warped

by living in a world which blatantly advertises its convic

tions of the Negroes’ inferiority. Segregation stimulates

a variety of unhealthy responses. It may tend to induce

withdrawal, thus extending the isolation of Negroes in

America and widening the gap between the racial com

munities. Myrdal, op. cit., supra, page 28. “ The Negro

genius is imprisoned in the Negro problem” (Ibid.). See

also Johnson, An Autobiography of an Ex-Colored Man

(1927), p. 21; Tuck, Not With The Fist (1946), p. 107.

Segregation has equally devastating effects when it

induces submission rather than rebellion—when it leads to

25

acceptance of the inferior status defined in the institutions

of the dominant community. This attitude invariably

stultifies Negro growth and encourages indifference,

apathy and unwillingness to compete.

“ Accommodation involves the renunciation of pro

test and aggression against undesirable conditions of

life and the organization of character so that protest

does not appear but acceptance does. It may come to

pass in the end that the unwelcome force is idealized,

that one identifies with it and takes it into the per

sonality, that some time it even happens that what is

at first resented and feared is finally loved. In this

case a unique alteration of the character occurs in the

direction of masochism”. Dollard, Caste and Class

in a Southern Town, at page 255.

Finally, the deleterious effects of segregation find in

exorable expression in a deep sense of personal insecur

ity. Fear of his own inadequacy turns the Negro against

the whites who have inflicted his frustration, against his

own people for providing a heritage of pain or against

himself in an over-weaning guilt for his own secret wishes

to he free of his burden.

One psychologist has noted particularly the deep re

sentment induced by the discrepancy between the vaunted

American creed that all are created equal and the hitter

fact of subjugation through segregation:

“ The effects of this enforced status on the level of

self-esteem, on feelings of inferiority and personal

insecurity, the gnawing doubts and the compensatory

mechanisms, the blind and helpless and hard to han

dle more or less suppressed retaliatory rage, the dis

placed aggression and ambivalence toward their own

kind with a consequent sense of isolation and of not

belonging anywhere—all of these and much more are

bad enough, but the ambiguity of status created by

26 jr

a society which insists on. the fact that all men are

horn free and equal, and then turns about and acts

as if they were not is eyen worse. The constant

reminder—and even boasting—of this equality acts

like salt upon a raw vjbund and, more basically, places

them in a profoundly ambiguous and unstructured

situation. Human beings simply cannot function effi

ciently in such situations if they have strong feelings

and are strongly motivated—as many, if not most or

all, member's of discriminated against minority groups

are—with regard to these situations.” Deutscher and

Chein, op. tit., supra, at page 272.

Psychic injury always accompanies segregation. We

think it patent that as between a system which imposes

suet)/ penalties and one which does not, there can be no

talk of equality.

POINT HE

A requirement of equality can never be satisfied by

segregated facilities because the official act of segrega

tion of itself gives superior value to the facilities as

signed to the dominant group.

We have shown above that the separate but equal doc

trine has in fact resulted in inequality and the creation of

a caste system. We show here that that is an inevitable

result of officially imposed segregation and that since the

discrimination flows from official action, it is unconstitu

tional.

the segregation in the. pmsent case was. orjgi-

mulatgd'''by aVprivatjylTgency\ the railrp&d, it has

; status he for 6 tide Court as Woveprfnenta lly in-

gfegation. We'Hiave stated the''‘reasons for this

27

equivajprf^e above namely,,,Jhat .the railroad’s regu-

latkjd^wasXappEofed by l$he I^O. C. aitd that* the railprtid

is/a state-cheated monopoly which. maV -̂riot discriminate.

A. A n Official P olicy of Segregation W ould Be Unconsti

tutional if M aintenance of R acial Superiority W ere

Proclaim ed as Its Purpose

It can hardly be disputed that an official regulation pro

viding for the confinement of any racial or religious group

to separate cars or to certain portions of a single car upon

the declared theory that the group is inferior would be

discrimination. That much is virtually conceded in the

Plessy decision {supra, p. 17). The official declaration

of inferiority would of itself establish an inferiority of

value substantial enough to have constitutional signifi

cance {supra, p. 18). While the declaration of inferiority

alone might be immune to constitutional attack it becomes

subject to judicial restraint when accompanied by action

having a discriminatory effect. The formal assignment of

separate areas based on a formal statement of inferiority

would be an assignment of facilities inferior per se regard

less of their physical identity with the facilities assigned

to the dominant group.

The situation as here described would not be mere

social inequality. We may assume that social inequality

has antedated the official ruling. But the accompanying

declaration of that pre-existing social inferiority and the

ensuing action of assignment of facilities, inferior because

segregated, amount to the creation of a legally sanctioned

inequality.

j , f :

S tr

ip A

28

B. The^Placing of a R acial or R eligious Group in an

Inferior Status by Segregation Can Be A ccom plished

W ithout an Express D eclaration of Such Status

We do not have here, of course, an express statement

by the Southern Bailway Co. or the Interstate Commerce

Commission that the purpose of the segregation is to

maintain inequality. Nevertheless, the same results must

be reached if that is in fact its purpose or effect. A regu

lation may not accomplish by indirection what it may not

achieve directly. Poindexter v. Greenhow, 114 U. S. 270,

295; Yick Wo v. Hopkins, 118 U. S. 356, 373; Gwinm and

Beal v. United States, 238 U. S. 347, 364; Myers v. Ander

son, 238 U. S. 368; Neal v. Delaware, 103 U. S. 370.

The failure of a statute or regulation expressly to

declare a legal inferiority does not protect it from the

scrutiny of the courts. When the reasonableness of a

classification endorsed by any governmental body as a

basis for action is in question, the courts will look behind

the apparent intention to determine whether or not, in fact,

an unlawful classification has been made. Henderson v.

Mayor, 92 U. S. 259, 268; Bailey v. Alabama, 219 U. S.

219, 244; Penn Coal Co. v. Mahon, 260 IT. S. 393, 413.*

I

* Any classification adopted by a governmental body as the basis of official

action must be viewed not in the abstract but realistically in the social set

ting in which it operates. The judge “must open his eyes to all those con

ditions and circumstances . . . in the light of which reasonableness is to be

measured . . . In ascertaining whether challenged action is reasonable, the

traditional common law technique does not rule out but requires some in

quiry into the social and economic data to which it is to be applied. Whether

action is reasonable or not must always depend upon the particular facts and

circumstances in which it is taken.” Harlan F. Stone in 50 Harvard Law

Review, pp. 4, 24 (1936). See also Poindexter v. Greenhow, supra; Village

of Euclid v. Ambler Realty Co., 272 U. S. 365, 387-388; Connor v. Board of

Commissioners of Logan County, Ohio, 12 F. (2d) 789, 795. Furthermore,

this Court has declared that “where the facts as to the situation and the

conditions are such as to oppress or discriminate against a class or an indi

vidual the courts may consider and give weight to such purpose in consider

ing the validity of the ordinance.” Dobbins v. Los Angeles, 195 U, S 223,

240. Yick Wo v. Hopkins, 118 U. S. 356, is the classical application of this

approach to prevent racial discrimination.

29

The implicit rather than the explicit declaration of

inferiority may he made in at least two ways: First, the

inferiority may have been established in other official acts.

Thus, if statutes, judicial decisions or other official pro

nouncements declare that a particular race is inferior, the

assignment of separate facilities becomes an assignment

of inferior facilities. We shall show below that such inde

pendent declarations of inferiority have in fact been made.

Second, the regulations may incorporate an already

established social stratification. Formal adoption of social

classifications of necessity implies the adoption of the

meaning inherent in, and inseparable from, the classifica

tions themselves, that of the respective inferiority and

superiority of the groups. Whenever law adopts a social

classification based on a notion of inferiority, it trans

forms the pre-existing social inequality into official in

equality. What ensues is official discrimination, a denial

of equality before the law, whether or not the statement

of inferiority is made openly by the government or in

heres in the classification upon which official action is

based.

The reason that constitutional inhibitions attach when

governments give official sanction to pre-existing social

inequalities is that such action causes a change in both

the degree and nature of the inequality. Once a social

classification based on group inferiority is formally

adopted, the ensuing official inferiority will in its turn

intensify and deepen the social inequality from which it

stems. The actual operation of segregation statutes illus

trates this oppressive function of the law. It is well

known, for instance, that the doctrine of “ separate but

equal” facilities has proved to be a mere legal fiction in

most cases, that invariably segregation has been accom

panied by gross discrimination, and that absolute equality

seldom, if ever, exists. For example, the President’s Com

mittee on Civil Eights found that the “ separate but

30

equal” doctrine “ is one of the outstanding myths of

American history for it is almost always true that while

indeed separate these facilities are far from equal” (“ To

Secure These Rights,” pp. 81-82).

This situation involves at the same time another kind

of vicious circle. The effect of segregation laws makes

their spontaneous repeal or amendment a practical im

possibility. When a more or less inarticulate social feel

ing of racial superiority is clothed with the sanction of

official regulation, that feeling acquires a concreteness

and assertiveness which it did not possess before. The

stricter the regulation, the stronger and the more articu

late the feeling of social distance. And the stronger that

feeling, the stricter the regulation and the more difficult

its amendment or repeal. In such a setting, the demo

cratic processes themselves are threatened and no reliance

can be placed on their correcting effect. It is this situa

tion which Chief Justice Stone had in mind when, in

sustaining an economic measure as presumptively valid,

he warned that the decision did not foreclose the question

whether “ legislation which restricts those political proc

esses which can ordinarily be expected to bring about

repeal of undesirable legislation, is to be subjected to

more exacting judicial scrutiny under the general pro

hibitions of the Fourteenth Amendment than are most

other types of legislation” and whether “ similar consider

ations enter into review of statutes directed at particu

lar religious . . . or national . . . or racial minorities.”

Accordingly, he noted that “ prejudice against discrete

and insular minorities may be a special condition, which

tends seriously to curtail the operation of those political

processes ordinarily to be relied upon to protect minori

ties, and which may call for a correspondingly more

searching judicial inquiry.” United States v. Carotene

Products, 304 U. S. 144, 154, footnote 4.

We shall show in the following sections that the sys

tem of segregation is in fact designed to maintain in

equality.

31

C. The Segregation of N egroes M aintains an Officially

D eclared Status of Inferiority and A lso a Previously

E stablished Status of Social Inequality

1. Official Declarations of I nferiority

State imposed segregation stems directly from a ves

tigial theory of the superiority and inferiority of races

inherited as a remnant of the institution of slavery. With

the freeing of slaves, attempts were made by the dominant

white group to preserve its position of ascendancy by the

enactment of discriminatory legislation. “ It required little

knowledge of human nature to anticipate that those who

had long been regarded as cm inferior and subject race

would, when suddenly raised to the rank of citizenship,

be looked upon with jealousy and positive dislike and that

state laws might be enacted or enforced to perpetuate the

distinctions that had before existed.” Strauder v. West

Virginia, 100 U. S. 303, 306 (italics supplied). Thus, in

the post-slavery period, Negroes were punished with

greater severity than whites for identical offenses. See

General Laws under the Seventh Legislature of the State

of Texas, Chapter 121. And Negroes were made incom

petent as witnesses in proceedings against white persons.

Laws passed by First Legislature of the State of Texas,

An Act to regulate proceedings in a District Court, Sec

tion 65. In the State of Texas the abiding conviction of

the inferiority of the Negro race is manifest even in its

assessment statutes. “ Assessors shall receive 3 ̂ each

for each white inhabitant residing in the county * # * 2<j

for each white inhabitant in a town or city and 1$ for

each slave or free person of color.” Laws passed' by the

First Legislature of the State of Texas, An Act to Pro

vide for the Enumeration of the Inhabitants.

These official declarations of inferiority have by no

means been abandoned by the Southern states. They are

maintained and reiterated in the many decisions holding

32

that the word “ Negro” or “ colored person” if applied

to a white person gives rise to a cause of action for

defamation. Flood v. News and Courier Co., 71 S. C. 112;

Stultz v. Cousins, 242 F. 794. Every court which has

considered the question has held that writing that a white

man is a Negro is libelous per se. Upton v. Times-Demo-

crat Pub. Co., 104 La. 141, 28 So. 970; Collins v. Okla

homa State Hospital, 76 Okla. 229, 184 Pac. 946; Hargrove

v. Okla. Press Pub. Co., 130 Okla. 76, 265 Pac. 635; Flood

v. News and Courier Co., 71 S. C. 112, 50 S. E. 637; Stultz

v. Cousins, 242 Fed. 794 (C. C. A. 6). It is believed that

Alabama, Georgia, Illinois, and Kentucky would concur

because of expressions in the opinions of their courts.

Jones v. Polk & Co., 190 Ala. 243, 67 So. 577; Atlanta

Journal Co. v. Farmer, 48 Ga. App. 273, 172 S. E. 647;

Wright v. F. W. WoolworthCo., 281 111. App. 495; Williams

v. Riddle, 145 Ky. 459, 140 S. W. 661. See Mangum, The

Legal Status of the Negro, 1940, at p. 18.

The attitudes of these courts is clear. “ It is a matter

of common knowledge that, viewed from a social stand

point, the Negro race is in mind and morals inferior to

the Caucasian. The record of each from the dawn of

historic time denies equality.” Wolfe v. Georgia Railway

Electric Co., 2 Ga. App. 499. Similarly, the highest court

of Oklahoma has declared: “ In this state, where a rea

sonable regulation of the conduct of the races has led

to the establishment of separate schools and separate

coaches, and where conditions properly have erected un-

surmountable barriers between the races when viewed

from a personal and social standpoint, and where the

habits, the disposition, and characteristics of the race

denominate the colored race as inferior to the Caucasian,

it is libelous per se to write of or concerning a white

person that he is colored. Nothing could expose him to

more obloquy, or contempt, or bring him into more dis

repute, than a charge of this character.” Collins v. Okla-

33

homa State Hospital, 76 Okla. 229, A Texas coart has

ventured the opinion that, “ Although we have no Texas

case holding that to falsely charge a white person as

being a Negro would be slanderous, yet in view of the

social habits, social customs, traditions and prejudices

prevalent in this state in regard to the status of whites

and blacks in this state, we think such a charge would

be slanderous.” O’Connor v. Dallas Cotton Exchange,

153 S. W. 2, 266.

Even more direct proof that the segregation statutes

rest on doctrines of racial superiority may be found in

the courts’ attitude when the statutes are misapplied.

Their consistent holding that it is humiliating to require

a white passenger to ride in a Jim Crow car betrays offi

cial recognition that the facilities are not equal even in

the eyes of the law.

Thus, in a Texas case, the court declared, “ To with

hold from a white lady the right to ride in a coach such

as the law requires to be provided for her race and to

compel her and her children to ride in one occupied by

Negroes for whom under law it is provided exclusively

constitutes such a violation of law and breach of duty

as to render it liable for damages for such discomfort

and humiliation as are proximately caused from such

breach of duty.” M. K. T. Railway Co. of Texas v. Ball, 25

Tex, Civil App. 500, 61 S. W. 327. Similar decisions were

reached in Louisville and N. R. Co. v. Ritchel, 148 Ky. 701;

Chicago, R. I. and P. Ry. Co. v. Allison, 120 Ark. 54.

Consistently with these cases, a white passenger could

recover damages if he were now required to sit at the

dining car table which the railway assures us is now avail

able to appellant. If the law recognizes damage in such

a case, how can it, in any sense, view the facilities as

equal?

34

2. T he P reviously E stablished Social I nequality

“ Supremacy” is not “ equality.” That proposition

needs no elaboration. Yet it is easy to show that the

doctrine of segregation is irrevocably linked with the

equally widely held, though admittedly unconstitutional,

doctrine of “ white supremacy.” At the very least, it has

led to that doctrine, as Justice Harlan predicted in his

dissenting opinion in Plessy v. Ferguson, 163 IT. S. at 559-

564.

It is consequently not strange that students of segrega

tion statutes uniformly find that they rest on notions of

superiority. By segregation “ racial and cultural differ

ences between southern whites and slaves were translated

into terms of unquestionable superiority and inferiority.”