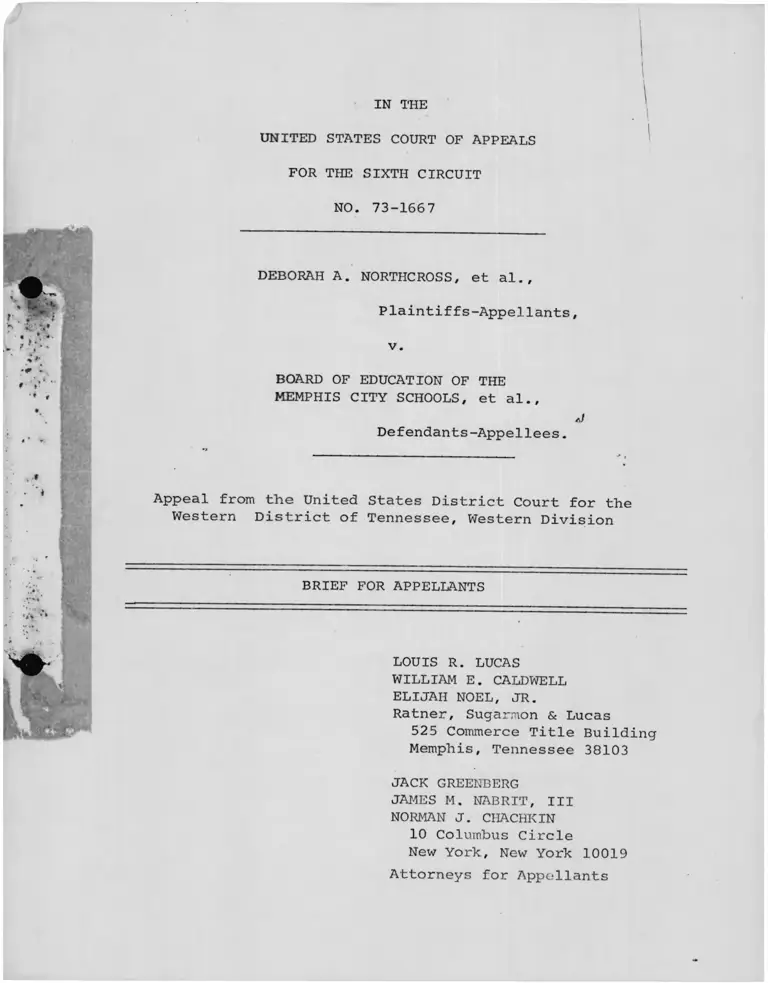

Northcross v. Memphis City Schools Board of Education Brief for Appellants

Public Court Documents

August 13, 1973

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Northcross v. Memphis City Schools Board of Education Brief for Appellants, 1973. a99c9ad2-bf9a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/377d96e6-f9d5-4940-80e9-82a9571a7841/northcross-v-memphis-city-schools-board-of-education-brief-for-appellants. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

I

IN THE

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE SIXTH CIRCUIT

NO. 73-1667

DEBORAH A. NORTHCROSS, et al..

Plaintiffs-Appellants,

v.

BOARD OF EDUCATION OF THE

MEMPHIS CITY SCHOOLS, et al.,

J

Defendants-Appellees.

Appeal from the United States District Court for the

Western District of Tennessee, Western Division

BRIEF FOR APPELLANTS

LOUIS R. LUCAS

WILLIAM E. CALDWELL

ELIJAH NOEL, JR.

Ratner, Sugarmon & Lucas

525 Commerce Title Building

Memphis, Tennessee 38103

JACK GREENBERG

JAMES M. NABRIT, III

NORMAN J. CHACHKIN

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

Attorneys for Appellants

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Page

Table of Cases.............................. ii

Issue Presented for Review.................. 1

Statement of the C a s e ...................... 3

Proceedings ............................ 5

The Plans.............................. 7

The District Court's Decision .......... 16

ARGUMENT —

Mo Plan of "Desegregation" Which Assigns

21,000 Black Students To All-Black Schools

Can Meet The Constitutional Obligations J

Of The Memphis School Board;

A Complete Desegregation Plan With A

Maximum Busing Time of 52 Minutes Is

No Less Feasible And Practicable Than A

Plan Busing Students 45 Minutes But

Leaving 25 All-Black Schools Which Enroll

21,000 Black Children .................. 19

"Adaptability" ............. 23

" C o s t " ...................... 33

"Preservation of desegregation" 34

"Time and distance".......... 37

Conclusion.................................. 3 9

Appendix A - History of Case Since Remand

of August 29, 1972 ............ la

l

Table of Contents (continued)

Page

Appendix B - Medley v. School Board of the

City of Danville, Virginia, No.

72-2373 (4th Cir., August 3,

1973) ........................... lb

Appendix C - Comparison of Enrollment Projections

at All-Black or Virtually All-Black

Schools Remaining Under Plan Approved

by District Court and Under Plan

Supported by Plaintiffs, With and

Without Attrition Formula Applied lc

TABLE OF CASES

Bradley v. Milliken, No. 72-1809 (6th Cir., aI

June 12, 1973) 27, 33

Brewer v. School Bd. of Norfolk, 456 F.2d

943 (4th Cir.), cert, denied, 406 U.S.

933 (1972) ............................ 33

Brown v. Board of Educ., 347 U.S. 483 (1954) . 20, 25

Brunson v. Board of Trustees, 429 F.2d 820 ,

(4th Cir. 1970)........................... 27

Cooper v. Aaron, 358 U.S. 1 (1958).......... 26

Davis v. Board of School Comm'rs of Mobile,

402 U.S. 33 (1971) .................... 18 /

Franklin v. Quitman County Bd. of Educ.,

443 F . 2d 909 (5th Cir. 1971) .......... 24n

Goss v. Board of Educ. of Knoxville, No.

72-1766 (6th Cir., July 18, 1973) . . . 19, 22, 33

Green v. County School Bd., 391 U.S. 430 (1968) 20

ii

Table of Cases (continued)

Pa£e

Kelley v. Metropolitan County Bd. of Educ.,

463 F.2d 732 (6th Cir.), cert, denied,

409 U.S. 1001 (1972) .................. 2-3, 20

Kelley v. Metropolitan County Bd. of Educ.,

436 F.2d 856 (6th Cir. 1970) .......... 20

Mapp v. Board of Educ. of Chattanooga, 477

F.2d 851 (6th Cir. 1973) .............. 19

Medley v. School Bd. of Danville, No. 72-2373

(4th Cir., August 3, 1973) ............ 21n

Monroe v. Board of Comm'rs of Jackson, 391

U.S. 450 (1968)........................ J 24, 25, 26, 32

Monroe v. Board of Comm'rs of Jackson, 427

F.2d 1006 (6th Cir. 1970).............. 25

Northcross v. Board of Educ. of Memphis,

466 F.2d 890 (6th Cir. 1972), cert.

denied, ___U.S. ____ (1973), vacated

and remanded on other grounds, ___ U.S.

___ (1973) ............................ 3, 20, 22n

Northcross v. Board of Educ., 333 F.2d 661

(6th Cir. 1964)........................ 35n, 36

Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Bd. of Educ.,

402 U.S. 1 (1971)...................... 18, 20, 37

Thompson v. School Bd. of Newport News, 465

F.2d 83 (4th Cir. 1972), cert, denied,

___ U.S. ___ (1973).................... 37

It's Not the Distance, "It's the Niggers"

(NAACP Legal Defense and Educational

Fund, Inc., 1972)...................... 24

IN THE

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE SIXTH CIRCUIT

NO. 73-1667

DEBORAH A. NORTIICROSS, et al.,

Plaintiffs-Appellants,

v.

BOARD OF EDUCATION OF THE

MEMPHIS CITY SCHOOLS, et al.,

aJDefendants-Appellees.

o ------ i , '

Appeal from the United States District Court for the

Western District of Tennessee, Western Division

BRIEF FOR APPELLANTS

Issue Presented for Review

Whether the mandate of the Constitution, and that of

this Court, requiring the eradication of the dual school system

and its vestiges, is satisfied by the adoption of a plan which

assigns over 21,000 black school children--almost one-third

of all Memphis black students— to all-black schools, where:

(a) the district court expressly admitted

it was ordering a lesser degree of desegregation

than was feasible because it feared white students

would leave the system in greater numbers if total

desegregation were ordered;

(b) the cost of a complete plan of desegre

gation would amount to less than 3% of a total school

system budget projected at $104 million;

(c) the plan fails to desegregate all schools

in part because of its designers’ desire to Maintain

assignments under the incomplete plan of desegregation

implemented last year, to which plaintiffs objected

at the time of its approval, and which this Court held

to be insufficient compliance with the Constitution in

its ruling of August 29, 1972; and

(d) the times and distances of travel required

in order to achieve complete desegregation, while

greater in some instances than those required under

the inadequate plan approved by the district court,

are well below those approved by this Court's

decision in Kelley v. Metropolitan County Bd. of Educ.,

463 F.2d 732 (6th Cir.), cert, denied, 409 U.S. 1001

\

(1972); they were not characterized by the Memphis

I

school administrators who testified at the hearing

before the district court, as being in themselves

educationally harmful, although those witnesses

expressed a preference for the plan ultimately

approved by the district court.

Statement of the Case

The recent procedural history of this school desegregation

j i/action is set forth in detail in Appendix "A" hereto. This

appeal concerns the adequacy of the desegregation plan for

the Memphis public schools adopted by the district court

following this Court's August 29, 1972 remand. Northcross v.

Board of Educ. of Memphis, 466 F.2d 890 (6th Cir. 1972), cert.

den. , ____ U.S. ____ (1973) , vacated in part and remanded on

other grounds, ____ U.S. ____ (1973). That plan, denominated

"Plan Z" by the district court (and variously styled "Board

Plan," "Plan II Elementary," "Sonnenburg Plan," "Plan II

Secondary," or simply "Plan II" in the testimony and exhibits

1/ Appendix "A," and this Brief, cover only those events since

this Court's 1972 remand. See text infra. The prior history of

the case is set out in detail in Appendix "A" to the Brief for

Cross-Appellants in No. 72-1631 filed on or about June 30, 1972.

below), is projected to assign 21,314 black Memphis students to

all-black or virtually all-black (95% or more) facilities, allI

of which were constructed and operated as black schools under

the dual system: two high schools, four junior high schools,

2/

and nineteen elementary schools. The issue before this Court

therefore, is whether the district court's determination to

accept— as the end-product of more than a decade of desegre

gation litigation in Memphis— a plan under which 30% of all

3/

black students in Memphis will go to all-black schools, can

be justified on this record and on the grounds stated by the

court below.

2/ At the time of the major hearing before the district court

in April, 1973, following which that court approved Plan Z

for implementation and directed submission of actual satellite

zones for the secondary plan, the projections of actual enroll

ment under Plan Z were based upon Fall, 1972 semester school

memberships (prior to implementation of Plan A, see Appendix "A

to this Brief). Using that data base, Plan Z was projected to

enroll 22,137 black students, 29% of all black children in

the system (including kindergarten and special education

students) in all- or virtually all-black schools. However,

prior to the district court's final approval of Plan Z and

the satellite zones drawn by the school staff, new enrollment

projections were entered into the record in the Board's Report

and as an exhibit to Dr. Stephens' deposition of June 25, 1973.

These projections were based upon Spring, 1973 (post-Plan A

implementation) elementary school enrollments and actual

satellite zone pupil locator map counts reflecting second

semester enrollments in secondary schools. The updated figures

are given in the text.

3/ Excluding special education and kindergarten students from

the computation. See Exhibit 1 to deposition of Dr. Stephens,

June 25, 1973.

4

Proceedings

Following this Court's August 29, 1972 remand, the ;

district court conducted several hearings and eventually-

determined that the partial desegregation steps in contro

versy here last year (Plan A) should not be implemented

4/until the second semester of the 1972-73 school year.

5/

See 9/27/72 Mem. Op.

Thereafter, the Court directed the school board to

complete preparation of a pupil locator map and to submit by

February, 1973 a plan which, when effectuated, wohld complete

the desegregation process in Memphis. See 11/15/72 Mem. Op.,

at p. 14. The submission date was subsequently enlarged by

the Court, and on March 12, 1973 (Tr. 12), the school board

submitted a series of desegregation plans to the Court

4/ High school desegregation was further postponed until

the 1973-74 school year. See No. 72-2053 in this Court.

5/ Since this appeal is being heard on the original papers

pursuant to this Court's Order of June 14, 1973, and as we did

last year, we shall refer to the various opinions and orders

below, whether titled or untitled, by date; citations in the

form "Tr. " are to the transcript of the hearing commencing

April 18, 1973, all of which is consecutively paginated. Exhibits

at that hearing will be identified as they are in the opinions

of the court below: as "H.E. ." Depositions introduced into

evidence will be appropriately identified by witness and date.

Pleadings will be identified by the title and date of filing.

̂ -

(H.E. 1).6/ |

The combination of Board Plan I, a secondary plan,

1

■and Plan III, an elementary plan, would desegregate every

school in the Memphis system (Tr. 16, 17, 23). Plan II

Secondary and elementary)would leave over 21,000 black

Memphis students in all-black schools (see note 2 supra).

Pursuant to a district court order of March 16, 1973,

defendant:, subsequently filed maps illustrating the various

plans (H.E. 8 - H.E. 14), and both parties on April 9, 1973

submitted statements of position on the plans. Plaintiffs

supported Plan I (secondary) and Plan III (elementary) with

certain ..suggested modifications; the school board expressed

its preference for the more limited Plan II.

A three-day hearing was held April 18-20, 1973,

following which the district court, in an opinion issued

on May 3, 1973 (and by judgment entered May 17, 1973),

approved Plan II in principle and required submission of

6/ By agreement of the parties, three additional copies of

H.E. 1, containing the desegregation plans supported by the

parties, have been forwarded to the Clerk of this Court for

distribution to the members of the panel.

6

These were

2Jactual satellite zones for its approval,

submitted by the school board on May 24, 1973; plaintiffs

subsequently took additional testimony thereon by way of

deposition and formally responded; on July 26, 1973, the

8/district court entered its judgment approving the zones.

The Plans

This matter involves the question of which desegre

gation plan of the Memphis school board fulfills the

constitutional obligation of that agency. The plan supported

J

by plaintiffs is one drawn by the team of administrators

assembled by the school board (Tr. 16), with the goalof

desegregating every facility in the system (Tr. 16, 17, 23).

7/ The plans were submitted by the board with the understanding

that satellite zones for assignment of secondary pupils had not

been drawn; the plans and accompanying maps indicate the numbers

of pupils to be exchanged between or among the various existing

attendance zones, however. The procedure, which was satisfactory

to all parties, eliminated the necessity of drawing detailed

satellite zones from pupil locator information twice: once for

Plan I and again for Plan II, in advance of a determination by

the district court as to which plan would satisfy the board's

constitutional obligations.

8/ The district court's July 26, 1973 order provided that

the record on this appeal from the court's May 17, 1973

judgment approving Plan II, subject only to the submission of

acceptable satellite zones, be supplemented with the evidence

and pleadings leading to the entry of that [July 26] order,

and we understand this has been accortvplished.

7

The witnesses agreed that it was as good a plan as could be1

drawn for this purpose (Tr. 73, 142, 231; cf. Tr. 489, 497).

A total of five different plans was submitted by the

board to the district court: two secondary alternatives and

three elementary plans. As indicated by their order of

presentation in H.E. 1, Plan III Elementary was designed

to be most compatible with Plan I Secondary, while Plan II

1/Elementary and Plan II Secondary were articulated. All

plans use transportation and non-contiguous "satellite"

10/zones at the secondary level, and transportation and

J

non-contiguous pairing or clustering at the elementary grades.

The difference between the plans supported by the plaintiffs

9/ On occasion in the testimony, "Plan 1" is used to refer

to the secondary Plan I - elementary Plan III combination,

and "Plan 2" to secondary Plan II - elementary Plan II.

10/ Although the school board eventually selected the

"satellite" or non-contiguous zoning technique, it also

discussed selection of students to be transported from existing

secondary school zones to new school assignments on the basis

of a lottery (Tr. 128-29). All plans before the district court,

and involved in this appeal, use the existing (pre-Plan A)

attendance zones of the Memphis public schools as the basis for

the desegregation steps proposed. At the elementary grade

level, existing school attendance areas are paired or clustered

and grade structures revised; at the secondary level, the

results projected under both Plan I and Plan II were arrived at

by designating the number of white or black students to be

removed from any particular area and reassigned, with delineation

of the satellite zone which would accomplish this result to be

completed by using the updated pupil locator map. See note 7

supra.

8

and the school board result from the differing extent to

1which these desegregation tools are employed: while the

Plan I-Plan III combination utilizes them fully to desegregate

every school, Plan II leaves some 25 black school facilities

11/out entirely. Both plans, as drafted by the board's

desegregation team, have in common certain design limitations:

(a) the preservation, with varying exceptions, of assignments

made for the Spring, 1973 semester under Plan A; (b) the

determination to utilize contiguous pairing and rezoning

12/

insofar as possible in the mid-city area (Tr. 55); and

J

11/ As a result, Plan II also maintains far more majority-

white schools, in this nearly 60% black system (H.E. 1, p. i),

than does Plan I (Tr. 500). Indeed, virtually every school

which was majority white in 1971-72, prior to this Court's

determination of the last appeal, retains majority-white status

under Plan II (Tr. 211, 216). And under Plan II, unlike

Plan III, at the elementary level, many clusters involve several

white schools and only one black school with resulting white

predominance (Tr. 172-73).

12/ The determination to utilize rezoning and contiguous pairing

(maintain Plan A techniques at the elementary level or those

which had been proposed for Plan A at the high school level)

in the mid-city area is a particularly critical one. Against

the background of rigid residential segregation in the city

(see 466 F.2d, at 893), with blacks generally concentrated

in the western areas and whites to the east, two polar

desegregation techniques are available: maximum use of

contiguous zoning and pairing in the middle, with busing only

at the extremes; and pupil exchanges between the middle and

each end. The former technique minimizes the number of

students transpoi ed, although the distance some of those who

travel must go is great; the latter technique results in more

students riding but minimizes the distance of the rides. Plain

tiffs do not quarrel with the school board's choice of the first

alternative except insofar as it is then sought to be used as a

justification for leaving 21,000 black students in all-black school

9

(c) the limitation, in the drawing of satellite zones under

\

the plans, of the number of students whose assignments would

Ibe changed to equal 30% of the school's optimum capacity,

plus the number by which that optimum capacity is presently

13/

exceeded. As a consequence of these limitations, the

level of desegregation is reduced, and plaintiffs accordingly

pressed for certain modifications even of Plan I, otherwise

acceptable to them in its basic format.

I

13/ The process works as follows: Assume White .School and

Black School are two uni-racial high schools scheduled to

"exchange" pupils in satellite zones for desegregation. Each

enrolls 500 pupils, but their "optimum" capacities are 550

students and 450 students, respectively. The board's desegre

gation team was guided by the notion that 70% of optimum

capacity presently enrolled in each school should not be

reassigned. That is, 385 of the 500 pupils at White School

should remain, but only 315 of the black students at Black

School. Since each school is to be filled only to its

optimum capacity (Tr. 158), White School can receive only 165

of the 185 students at Black School subject to reassignment.

The 20 "extra" black students might remain at Black School

f'/hich will also receive 115 White School pupils) , or be assigned

elsewhere in the system— with little effect upon the racial

composition remaining at Black School. The end result of the

exchanges and the "70% of optimum capacity" limitation upon

student movement is that White School remains 70% white and

Black School remains 73% black. Although the team charac

terized the limitation as one designed to end differential

school utilization (Tr. 205-07), it is perfectly apparent

from this example that both schools could be utilized at their

optimum capacities and their continuing racial identifiability

eliminated by the creation of appropriate satellite zones

without this limitation.

10 -

All of the plans submitted to the district court were

based on December, 1972 (pre-plan A) enrollment data (Tr. 23,

25); but prior to the final approval of July 26, 1973, the

projections were updated to conform to March, 1973 (post-

Plan A implementation) enrollment figures. See Exhibit A

to May 24, 1973 Report to the Court filed by school board;

Exhibit 1 to June 25, 1973 deposition of Dr. Stephens. The

estimates of cost, and of times and distances of pupil travel,

were based upon actual experience under Plan A (Tr. 27-28)

and were both smaller and more realistic than the estimates

which had been made when Plans A and B were first considered

last year (Tr. 27-30, 588-90).

Each plan, or combination of plans, also had a "Raleigh

Addendum," pursuant to the district court's direction:

"that the defendants include for consideration

in the preparation of the plan for further

desegregation, those areas to be annexed

on December 31, 1972, and to be included

within the defendants' jurisdiction at the

commencement of the 1973-74 school year."

12/14/72 Mem. Op., at p. 1. 14/

14/ As the Court may recall from last year's appeals, see

Brief for Plaintiffs-Appellees in No. 72-1630, pp. 16-19, 26-30,

the size of the City of Memphis and its school system has steadil

increased in recent years through annexations of territory from

surrounding Shelby County, Tennessee. The "Raleigh" area annexed

to Memphis effective January 1, 1973, and including schools trans

ferred to the Memphis board's jurisdiction July, 1973, is located

in extreme northeast Memphis; the Raleigh schools do not appear

on II.E. 8 - II.E. 14, but only on the series of maps introduced

by plaintiffs, II.E. 18 - H.E. 20.

11

(The Raleigh Addendum for Plan I appears as H.E. 1-A,. and that

for Plan II is found at H.E. 1, pp. 37-40.)

While sharing these general characteristics, the plans

may be further described, and their differences identified,

as follows: Under the Plan I (secondary) - Plan III (elementary)

combination, every school facility in the system would be

desegregated (Tr. 16, 17, 23). Although there were no time

constraints in the development of the plans (Tr. 68), they

do represent reductions of time and distance traveled in !

comparison to the suggestions of Board of Education members

(Tr. 52, 197-98) which led to the drafting of Plans I, II

15/and III (Tr. 124).

The maximum time for pupil transportation projected under

PlansI-III, with plaintiffs' modifications, was 63 minutes fop

one elementary trip (Tr.163-64; H.E. 33) or 52 minutes for the

same trip if the school buses used the interstate highways and

II /

15/ The team initially submitted to the Board the skeletal

outlines of a secondary plan which called for eliminating

several of the City's graduating high schools through grade

restructuring (Tr. 122-23). There was general dissatisfaction

with this proposal, with one result being attempts by various

board members to devise plans of their own (ibid.; see deposi

tions of Mrs. Coe and Mrs. Sonnenburg of April 16, 1973 and

April 17, 1973, respectively). The team then adapted these

proposals, in order to reduce the transportation times to

acceptable levels, developing them into Plans I and II (Tr.

197-98, 245).

12

expressways (Tr. 30-31, 163). At the secondary level, no

pupils would be bused longer than 45 minutes (Tr. 198; H.E.

33). Under Plan I-III, with plaintiffs' modifications, the

vast majority of Memphis students who are bused will be

transported between 31 and 45 minutes, especially if the

expressway routes are utilized (H.E. 33). 41.4 per cent

of all students would be transported to school (ibid.).■

The total cost of Plan I-III, with plaintiffs' suggested

modifications and the accompanying Raleigh Addendum (H.E. 1-A),

16/was put at $2,793,911 (Tr. 36). This is 2.6% of a total

J

school system budget projected to be $104 million (Tr. 418).

Under Plan II, on the other hand, 25 black schools are

completely left out of the desegregation process (H.E. 1).

Not only are student assignments to these all-black or

virtually all-black schools unaffected by the plan, but the

supplementary services which the system intends to provide

at other schools, in order to facilitate integration, will

not be made available to the 21,000 black pupils left in the

16/ Plaintiffs had projected a somewhat lower figure of

$2,573,095.95 using expressways, or $2,692,441.30 without express

way travel (H.E. 34), but the difference is not significant

for the purposes of this appeal.

13

iZ/all-black buildings (Tr. 171-72).

Plan II was deliberately designed to leave these students

in segregated schools in order to maintain a greater number of

Plan A assignments, and to keep more pupil transportation

times nearer the Plan A range (Tr. 17, 21, 23, 53). The longest

bus ride under the plan will be 45 minutes at both elementary

and secondary levels (H.E. 1, pp. 100-08); about 44% of all

Memphis' transported pupils will spend between 31 and 45 minutes

en route.

aJPlan II maintains many more majority-white schools, at

all levels, than Plans I-III; using 15% above or below the

system-wide, grade-level student ratio as a rough measure of

racially identifiable schools, Plan II creates many more such

facilities than Plans I-III (see H.E. 35; Tr. 581-88). Plan II

also involves significantly more one-way busing of black

students, as in the closing of Hyde Park School as part of

the Plan II Raleigh Addendum (Tr. 100, 289).

17/ Under Plan II, almost 20% of Memphis' black senior

high school students, 23% of black junior high pupils, and

40% of black elementary children are assigned to all-black

facilities. See note 2 supra.

14

The total cost of Plan II was estimated to be $1,683,897,

or 1.6% of the budget (Tr. 36).

Three members of the desegregation team, the Superintendent

and an expert witness for plaintiffs, Dr. Gordon Foster,

testified about the plans. There was agreement among these

witnesses that if all schools were to be desegregated, the

Plan I-III combination was about the best method which could

be devised (e.g. , Tr. 74, 142, 231). Dr. Stephens, for

example, said that he was "ambivalent" about Plan II secondary,

because it did not desegregate all junior and senior high

schools., (Tr. 145) , and that he supported it only because it was

less expensive than Plan I (Tr. 74).

All of the plans were characterized as educationally

sound; see Tr. 60 (Dr. Stephens: Plans I-III are less

acceptable to the public but educationally o.k.); Tr. 165

(while Dr. Sweet dislikes the maximum trip time under Plan III,

he has had no experience with transported students and knows

of no educational disadvantage); Tr. 489, 497 (Superintendent

Freeman: he has no educational, professional, or personal

objection to Plan III); Tr. 600 (Dr. Foster: Plan I-III

involves no educationally harmful times and distances). On

the other hand, all of the Board's employees expressed the view

15

that the shorter the times and distances of pupil travel, the

better the plan in terms of cost and public acceptance (Tr. 59-

GO, 73-75, 166, 231-32, 489). Dr. Foster, however, stated that

Plan II was objectionable because of the number of racially

identifiable schools it would maintain, which were not only

undesirable in themselves but which also weakened the remaining

portions of the overall plan (Tr. 582, 585).

The District Court's Decision

On May 3, 1973 the district court issued its memorandum

opinion approving Plan II. The opinion sets out'*the facts

o

surrounding the drawing of the plans in some detail (pp. 1-4)

18/

and describes some features of the various plans (pp. 5-12).

The court states that four factors underlie the proposal for

less desegregation under Plan II: "time and distance traveled

on buses, cost of transportation, preservation of desegre

gation already accomplished, and adaptability" (5/3/73 Mem. Op.,

at p. 12). The court then summarizes the proof offered by the

school board, making essentially the following points:

18/ The opinion fails to mention that Plan II will leave over

21,000 children in the all-black schools which it does not

affect.

16

— No maximum educationally sound travel times and

distances were established but school administrators testified

that shorter ones were preferable (5/3/73 Mem. Op., at p. 13);

— Longer routes reduce the number of trips each bus

can make and increase the cost of a plan, while the school

system's budget requests are normally cut by the city council

(ibid.);

— Other expenditures related to desegregation are required

at affected schools in order to smooth out the process (id.

at 14); J

— Plan II preserves more of the Plan A student assignments

(ibid.) ;

— Lesser degrees of desegregation are likely to receive

greater white community acceptance (”[d]ue to the long history

of racial discrimination in [Memphis] and its resulting racial

hostility") (id. at 14-17).

The district court then:

"concludes that implementation of the

secondary plan II and elementary Plan

II with their Raleigh Addendum at the

commencement of the 1973-74 school year

will constitute compliance with the

'additional instruction' set forth in

the August 29, 1972 opinion of the Court

of Appeals, even though the plans leave

some all black-schools."

17

Id. at 17. The court attempts to support its decision by-

referring to passages in Swann v. Charlotte Mecklenburg Bd.

of Educ., 402 U.S. 1 (1971), and Davis v. Board of School

Commissioners of Mobile, 402 U.S. 33 (1971), which mention

"limits" of practicality and "some small number of one-race

1?/schools remaining" (id. at 17-19).

As noted above, detailed satellite zones were then

submitted and approved by the district court on July 26,

1973.

J

19/ The district court's opinion also discusses two other

issues litigated in that court but which need not be con

sidered on this appeal: plaintiffs' request for modification

of the quota provisions regarding enrollment at the Campus

Elementary School, and the court's approval of broad student

transfer policies devised by the school board. With respect

to both issues, plaintiffs do not raise them on this appeal

but will litigate them further in the district court if the

reports to be filed by the board pursuant to the district court's

retention of jurisdiction indicate interference with the proper

functioning of the desegregation plan. We add only that the

district court's approval of transfer policies so vaguely

stated as to be virtually unintelligible (see Tr. 303-14)

stands in marked contrast to its earlier condemnation of such

transfer provisions because they served as a vehicle to

perpetuate segregation. See 10/18/72. Mem. Op., at p. 6.

18

ARGUMENT

No Plan Of "Desegregation" Which Assigns

21,000 Black Students To All-Black Schools

Can Meet The Constitutional Obligations

Of The Memphis School Board;

A Complete Desegregation Plan With A

Maximum Busing Time of 52 Minutes Is

No Less Feasible And Practicable Than A

Plan Busing Students 45 Minutes But Leaving

25 All-Black Schools Which Enroll 21,000

Black Children

The major issue for decision in this case is very

simply stated: it is whether the Constitution permits the

continued operation of 25 all-black schools in Memphis,

enrolling 21,314 black students.

This is almost ten times as many black children as

this Court's recent decision in Goss v. Board of Educ. of

Knoxville, No. 72-1766, -1767 (July 18, 1973), left (for

whatever reason) in virtually all-black schools. It is many

times more black pupils left in black schools than is the

case under the desegregation plan approved by this Court's

affirmance in Mapp v. Board of Educ. of Chattanooga, 477 F.2d

851 (6th Cir. 1973) . It is five times the number of one-race

schools left after desegregation in Nashville, a system with

nearly twice the geographic area of Memphis (Tr. 596-97 ;

19

H.E. 36), and it places half the percentage of black students

in all-black schools as were in such schools in Nashville

prior to the desegregation which this Court held was there

required by the Constitution. See Kelley v. Metropolitan

County Bd. of Educ., 436 F.2d 856 (6th Cir. 1970), 463 F.2d

732 (6th Cir.), cert, denied, 409 U.S. 1001 (1972).

This is hardly "1 some small number of one-race or

virtually one-race, schools within a district,'" Northcross

v. Board of Educ. of Memphis, 466 F.2d 890, 893 (6th Cir.

1972), cert, denied, ____ U.S. _____ (1973), quoting with

emphasis from Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Bd. of Educ.,

402 U.S. 1, 26 (1971). It is hardly the elimination of

segregation "root and branch," Green v. County School Bd.,

391 U.S. 430, 438 (1968). If sustained, this plan will be

nothing less than a lasting testament to judicial inability

to deliver the promise of Brown v. Board of Educ., 347 U.S.

483 (1954), to black students in this nation.

The result is so shocking that the uninitiated obser

ver must fairly leap to the assumption that the most compelling

reasons must exist to justify it. But the patent weakness,

and even plain illegality, of the reasons put forth by the

district court to justify its selection of Plan II, is

20

anything but compelling. It is disheartening indeed to find

that after years of litigation— patiently stripping away

layer after layer of excuse— when "Never!", "Freedom Of

Choice," "Neighborhood Schools," and "No Busing" have been

removed as impediments to constitutional compliance, 21,000

black students (nearly a third of all in Memphis) are told

by the United States District Court that, out of consideration

for the feelings and racial hostilities of the white community,

the Constitution has no meaning for them.

The inescapable, undisputed facts are these: all of

a/

the plans at issue were drawn by Memphis school personnel,

20/

not outsiders. The longest bus ride projected for any

20/ Plaintiffs' educational witness, Dr. Gordon Foster, did

present certain proposals to modify Plan I, but almost without

exception these merely increased the numbers of pupils to be

exchanged between existing attendance areas (see note 10 supra)

in order to eliminate the pattern of racially identifiable

schools (see, €?.£., Tr. 211) without either enlarging trans

portation times or altering the basic structure of the plan.

Although there was some attempt made below to characterize

Dr. Foster's modifications as efforts to achieve "racial

balance" (see, ê .g[., Tr. 269-70), but see, Medley v. School

Bd. of Danville, No. 72-2373 (4th Cir., August 3, 1973 [attached

hereto as Appendix "B"]), the district court never formally

ruled upon the modifications. However, its opinion seems to

describe the alternatives as being either Plan II or Plan I-III

with plaintiffs' modifications (.e.g;. , 5/3/73 Mem. Op., at

pp. 9-12), and we agree that if Plan II is constitutionally

unacceptable, modifications to Plan I are required.

21

single pupil under the most comprehensive desegregation

proposal before the district court is considerably shorter

than rides those pupils now take daily in Nashville and

throughout Tennessee. The direct cost of this comprehensive

plan amounts to less than 3% of this school system's budget—

again, a smaller percentage allocation for transportation

than the majority of Tennessee school districts make. And yet,

the plan approved by the district court will leave 21,314

black children in all-black schools, some of whom will never

be assigned to a desegregated facility throughout twelve years

of public education (Tr. 170). j

Indeed, this case was not resolved upon the basis of

disputed facts, nor do the arguments presented here question

■ 2 1 /

the factual findings of the district court. Compare Goss

22/

v. Board of Educ. of Knoxville, supra. What is at issue

is the legal significance accorded certain facts by the

district court. This appears clearly when the four reasons

21/ In the discussion that follows, however, plaintiffs do

on occasion point out statements in the district court's

opinion which are simply without support in the record.

22/ Goss is further distinguishable from this case because

whereas there, the district court held that remaining all

black schools were not vestiges of the dual system, 340 F.

Supp. 711, 729 (E.D. Tenn. 1972); see this Court's slip

opinion in Goss, supra, at p. 3, there can be no question

that the 25 all-black schools remaining in Memphis are

vestiges of the dual system. See Northcross, supra, 466 F.2d

at 893.

22

given by the court for its action are assessed in light of

constitutional standards.

1. "Adaptability." The district court readily concedes

that a major justification for adopting Plan II is

"the expected unwillingness of white

patrons to send their children to those

particular black schools. . . . "

(5/3/73 Mem. Op., at p. 14; see also, Tr. 500.) Although

the court completes this sentence with this phrase (implying

that something more than racial prejudice is involved):

". . . in light of the location and the

distances involved in the necessary J

exchange of white and black students"

•i

(id. at pp. 14-15), the court had previously described the

white community's reaction to desegregation in these terms:

"Due to the long history of racial dis

crimination in this city and its resulting

racial hostility, experience has shown that

extensive preparation is necessary to

effectively bring the students of different

races together."

(Id. at p. 14.) And it is clearly white hostility to the

effectuation of black students' constitutional rights about

which the district court is talking; note the court's

hypothesis that a system "cannot effectively desegregate

. . . if there are not sufficient members of the white race

available to assign" (id. at p. 15) and also the court's

23

"in order toapproval of minority-to-minority transfers

permit persons in isolated minority situations to transfer to

a minority situation of a greater percentage" (id. at p. 24).

Under Plan II, there are no situations in which black students

will be in the kind of "isolated minority" to which the

district court refers!

Furthermore, the examples used by the district court

to demonstrate "white flight" in Memphis (id. at 16-17)

involve contiguous schools, which make clear that the ground

of the objection is desegregation, not time or ^istance. Cf.

It's Not the Distance, "It's the Niggers" (NAACP Legal Defense

and Educational Fund, Inc., 1972).

The short of the matter is that the district court is

justifying its decision to leave 25 schools, and 21,000

black students, segregated because of an apprehension that

white students assigned to these schools may leave the public

system— precisely the line of argument which was explicitly

rejected by the Supreme Court of the United States in Monroe

v. Board of Comm'rs of Jackson, 391 U.S. 450 (1968). To

return to a notion we advanced above: this is not a compelling

23/

23/ Contra, Franklin v. Quitman County Bd. of Educ., 443 F.2d

909 (5th Cir. 1971).

24

reason for the district court's action, but a plainly

unlawful one.

But the court theorizes that despite Monroe, avoiding

white flight is one of the practicalities whose consideration

is mandated by Swann, 5/3/73 Mem. Op., at p. 15, at least in

this situation where such desegregation as has occurred has

been accompanied by some diminution in the number of white

students, id_. at pp. 15-17. But again, this is precisely the

argument made here and rejected by this Court in Monroe v.

24/

Board of Comm'rs of Jackson, 427 F.2d 1006 (6th Cir. 1970).

•*It is well to recall the basis of the Supreme Court's

1968 repetition in Monroe of Brown's statement "that the

vitality of these constitutional principles cannot be

allowed to yield because of disagreement with them [by a

segment of the community]." 391 U.S. at 459. This thesis

was early enunciated in the history of school desegregation,

when white lynch mobs in Little Rock, controllable only by

federalized National Guardsmen, sought to prevent seven minor

24/ The Board there contended it was not bound by the

Supreme Court's 1968 ruling because the record at that time

contained only the prediction that whites would flee desegre

gation, while in 1970 some white student loss had actually

occurred. This Court brushed the argument aside.

25

Negro children from enrolling at Central High School.

Cooper v. Aaron, 358 U.S. 1 (1958). Of course, we do not

face the same situation in Memphis today; black children in

these 25 schools will be permitted to enroll in other schools

25/

if they seek majority-to-minority transfers. But neither

did the Supreme Court face exactly the Little Rock situation

when the Board of Commissioners sought to preserve free choice

in Jackson, Tennessee in 1968. The common point of departure

in the cases is the damage we all suffer when the Constitution

is eroded by making federal courts the arbiters of the selling

price for constitutional rights. Monroe affirmed that Cooper

meant more than just that a hostile white community was

asking too much to assuage its feelings when it demanded that

even token desegregation be stopped.

It is no business of the federal courts to barter

constitutional rights among bidders. Yet that is what the

district court in this case has done, by suggesting that

although white hostility to desegregation would not justify

the pre-Plan A situation in Memphis (5/3/73 Mem. Op., at p. 15),

it could nevertheless support the maintenance of 25 segregated

25/ But see Tr. 543.

26

schools to which almost a third of all-black students

were to be consigned (id., at p. 17).

What will be the district court's reaction next year

if the white community "ups the ante" by demanding a

further cutback of desegregation? More to the point, is

this in any way a proper consideration by the district court?

Are constitutional rights to be the subject of negotiation

between the court and the white community? As Judge Sobeloff

said in Brunson v. Board of Trustees, 429 F.2d 820, 827 (4th

Cir. 1970):

J

"I, too, am dismayed that the remaining

white pupils in the Clarendon County schools

may well now leave. But the road to inte

gration is served neither by covert capitu

lation nor by overt compromise. . . . More

to be feared than white flight in Clarendon

County would be any judicial countenancing

of the suggestion that abandoning or quali

fying a desegregation program is a legally

acceptable way to discourage flight."26/

26/ Nor is the district court's judgment supported by the

decision in Bradley v. Milliken, No. 72-1809 (6th Cir.,

June 12, 1973). Indeed, any such attempt turns Bradley on

its head. The Court was there concerned not with the phenomenon

of white flight, but with the need to develop an effective

desegregation plan in the light of the existing containment

of blacks in a single school district. Nothing in this Court's

1970, 1971 or 1973 opinions in that case suggests that the

desirability of a metropolitan approach is a legal basis for

delaying desegregation; indeed, this Court's opinion con

templates (slip op., at p. 68) a possible interim Detroit-only

plan.

27

As if all this were not error enough, the record in

this case simply refutes the spectre of "not sufficient

members of the white race available to assign" conjured up

by the district court.

The evidence at the April hearing was that post-Plan A

enrollments showed a loss of between 7500 and 8000 white

students (Tr. 396). However, not all of this drop could be

linked to Plan A: enrollments normally drop during the

school year (Tr. 541) and some of the decline is also due

to a lowered birth rate (Tr. 552). And while there was no

groundswell, there had been considerable community effort

expended after Plan A was implemented (Tr. 479-80), and some

white children had returned to the public system (Tr. 481).

Finally, the declines in white student attendance were not

limited to schools affected by Plan A (see H.E. 28, 29) so

that it was not clear how many additional white children would

withdraw if and when a more thorough desegregation program were

implemented.

Against this background, the district court approved

Plan II in principle on May 3, 1973. However, significant

new evidence concerning anticipated "white flight" was put

28

before the court prior to its ruling accepting the Plan II

satellite zones and giving Plan II its final approval.

t

When the zones were submitted to the court by the

school board, they were accompanied by certain secondary

grade level projections; plaintiffs subsequently took

Dr. Stephens' deposition (on June 25, 1973) and elicited

several exhibits, which were filed with the deposition prior

to the district court's ultimate approval of Plan II on

July 26, 1973 (see note 2 supra). One of these, entitled

"Estimated Student Enrollment and Estimated Number of Students

to be Transported under Each New Desegregation Plan,", con

tains projections of anticipated white enrollment declines

this fall upon implementation of either Plan I-III or

27/

Plan II. Comparisons of anticipated enrollment under

Plans I-III and II, with and without application of this

"attrition formula," for the 25 schools which Plan II will

leave all- or virtually all-black, are set out in Appendix

27/ The methodology of the study is not fully explained (see

Stephens' deposition of June 25, 1973, pp. 29-34) but apparently

involved the use of multiple regression analysis techniques

to develop predictive equations which could be applied to

the enrollment projections available at the April hearing

(H.E. 1, pp. 55-81), so as to develop estimates of enrollment

on the assumption that further withdrawal of white students

would occur.

29

C. These data reveal that, if the Board's projections

are correct, some whites may not attend these schools if

assigned, but each school would enroll a significant number

of white students if Plan I-III were implemented— even

assuming a massive white withdrawal. (Each school would be

about one-fifth to one-third white). Given the alternatives

of placing 21,000 black students in all-black schools, or

putting them in schools with the racial compositions shown

in Appendix C to this Brief, the district court's preference

for total segregation is inexplicable.

The most astounding fact of all, however, 'is demonstrated

•tby totalling the predicted white student withdrawal under

each plan. This is shown in the table immediately following.

(It should be kept in mind that the attrition formulas were

applied to the pre-Plan A enrollments? i.e., the figures

given below include student loss from Plan A as well as

anticipated additional loss this fall). What the table

28/

28/ Exhibit 2 to Dr. Stephens' deposition of June 25, 1973

contains figures for all schools in the system, which indi

cate, according to the school system's projections, that white

withdrawal would not be limited to these 25 schools but would

occur throughout the system in reaction to desegregation.

Under these circumstances, it is difficult to understand

what the district court hoped to achieve by leaving 25 all

black schools. See text infra.

30

1

Total White Student Withdrawal Projected

Under Plan II and Plan I-III, From Exhibit

2 to Deposition of Dr. 0. Z. Stephens,

______________June 25, 1973______________

Plan I-III White Enrollment

Grade Level Projected

With

Attrition Loss

Elementary 25,638 17,186 8,452

Junior 15,562 10,972 4,590

Senior 14,945 10,570 4,375

TOTAL 56,145 38,728 17,417

Plan II White Enrollment

Projected

With

Attrition Loss

Increased

Loss From

Plan I-III

25,469 17,679 7, 970 662

15,439 11,091 4,348 242 i

14,916 11,105 3,811 564 rHcn

l

55,824 39,875 15,949 1,468

[ t e x t co n tin u es on next page]

indicates is that, because white students may leave the

school system whether they are assigned to these 25 schools

or not, the actual number of white children whom the Board

predicts will withdraw if plan I-III, rather than Plan II,

is implemented, is 1,468. In other words, the district

court and the Memphis School Board are willing to assign

21,000 black students to all-black schools in order to

entice 1,468 white students to remain in the system!

Forty per cent of Memphis' black elementary school pupils

are being assigned to segregated schools in order to keep

662 white pupils from leaving because they don'^ like

desegregation I

We respectfully submit that, whatever the limits of

a district court's discretion in choosing among alternative

desegregation plans, the choice made here far exceeds them.

If Monroe is no longer good law, and the district court’s

action is to be judged on the basis of the facts before it,

then this Court must reverse because discretion was badly

abused. But we repeat that in our view, considerations of

"white flight" should have had no place in the district

court's consideration, and that on this ground alone, the

district court must be reversed.

32

2. "Cost." As we noted above (pp. 13-15, supra),

the difference in transportation costs between Plan II and

Plan I-III is about 1% of Memphis' budget. And while Plan I-

III would require operating expenditures amounting to about

2.6% of the budget, this is still less than is spent for

29/

busing throughout Tennessee (H.E. 38).

The district court's discussion of cost (5/3/73 Mem.

Op., at pp. 13-14) says little more than that Plan I-III is

more expensive than Plan II. The court fails to address

itself to the relative size of the expenditure in the

context of the system's total budget. Cf_. Brewer v. School

•7Bd. of Norfolk, 456 F.2d 943, 947 n. 6 (4th Cir.), cert.

denied, 406 U.S. 933 (1972).

Whatever support the district court may have thought

was given its decision to segregate 21,000 black students by

financial considerations, it seems clear at this juncture

that this cannot be allowed to bar constitutionally required

integration. Goss v. Board of Educ., supra, slip op. at p. 4

Bradley v. Milliken, supra, slip op. at p. 79.

29/ The school system has also been saved considerable

capital outlay costs as the result of desegregation. See

Tr. 408-11 (estimated at $25 million including amortization

costs).

33

3. "Preservation of desegregation." A third basis

for the district court's decree merited but a single

paragraph of discussion in its opinion (5/3/73 Mem. Op.,

at p. 14). The court explains its reasoning as follows

(ibid.) :

"With regard to the factor of preser

vation of desegregation already accomplished,

this Court has previously directed and

approved the practice of preserving

desegregated schools which have accom

plished desegregation voluntarily. Based

upon this same reasoning, the team

drafted Plan II upon a basis that Plan

A heretofore implemented would be preserved

as much as possible. . . . "

J

Bearing in mind that on the other side of the balance are

21,000 black students still in segregated schools, one can

examine the district court's reasoning in order to

evaluate whether, and to what extent, a desire to preserve

Plan A assignments, justifies that result.

Initially, we note that the analogy to the court's

past suggestion that integrated school neighborhoods not

be split among new assignments, if possible (12/10/71 Mem.

Op., at pp. 19-20) is an inapposite one. Plan A obviously

does not represent voluntary desegregation. Furthermore,

insofar as portions of Plan A remain intact, its failings

as well as its successes may be carried forward into the

new scheme (see Tr. 506-19).

34

There seems little justification, at least in the

abstract, for seeking to preserve what has been recognized

30/to be an unconstitutionally limited plan.— But even

assuming some merit to the notion, the district court's

attempt to tip the scales in favor of Plan II on this

ground, distorts the realities of the situation. It was

not merely Plan II, but all of the plans, which were drafted

so as to preserve Plan A assignments insofar as possible

(Tr. 49-50). And the team was hardly reticent about departing

from Plan A: not only were junior high schools unpaired,

as the district court notes (5/3/73 Mem. Op., at*p. 14), but

Plan A assignments were changed to reduce travel time (Tr.

52), and some Plan A schools were closed for unrelated rea

sons (Tr. 65) .

Plan A was basically of concern at the elementary level

only, since its junior high school assignments were changed

and it had not been implemented in the senior high school

grades (see Appendix A, infra, p„ 3a). The guiding criterion

for Plan II was not maintaining Plan A assignments, but

hewing to Plan A transportation times (Tr. 17, 53, 134). It

30/ Indeed, the whole idea is suspiciously reminiscent of the

Board's past desire to cater to the convenience of the white

community in rezoning. Northcross v. Board of Educ., 333

F.2d 661 (6th Cir. 1964).

35

must be self-evident that the Memphis public schools cannot

be effectively desegregated without transporting pupils for

longer priods of time than was necessary in order to carry

out contiguous pairings as part of last year's constitu

tionally deficient plan. Thus to accept Plan II because it

"preserves Plan A" is to build into this decree the same

ineffectiveness which characterized the one entered in 1972.

We submit that a desire to maintain Plan A assignments

is an interesting, hardly compelling, practical consider

ation— but one of virtually no legal significance. If the

a!

district court had before it two plans of equal effective

ness, both of which proposed to desegregate all Memphis

schools, but one of which the school board supported because

it preserved more Plan A assignments than the other, it would

not be an abuse of discretion to adopt the board-preferred

plan for that reason, assuming all other factors were equal.

But that is not the case here. Indeed, the testimony was

that if all schools had to be desegregated, no better plan

was available than Plan I-III (Tr. 142, 237).

The district court has improperly elevated the conven

ience of a segment of the community, Northcross v. Board of

Educ., 333 F.2d 661 (6th Cir. 1964), above the constitutional

rights of 21,000 black students; its judgment should be

reversed on this ground.

36

4. "Time and distance. The final consideration

mentioned by the district court is a potentially valid one:

the times and distances of pupil transportation required by

the plans. See Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Bd. of Educ.,

supra, 402 U.S., at 30-31. A properly supported, detailed

finding that one of the plans involved times and distances

which were educationally unsound or harmful to a child's

health, would be entitled to some weight. Cf. Thompson v.

School Bd. of Newport News, 465 F.2d 83 (4th Cir. 1972), cert.

denied, ___ U.S. ___ (1973). The district court in this case

made no such finding.

Quite to the contrary, the one-paragraph discussion

of times and distances in this section of the court's opinion

(5/3/73 Mem. Op., at p. 13) frankly recognizes that none of

the times and distances under any of the plans were charac

terized in the Swann language by any of the qualified witnes

ses. The only point the district court seems to make is

that some times involved in Plan I-III are longer than those

in Plan II— a fact which plaintiffs have never sought to

.31/controvert.

31/ It is also a fact that some of the bus trips required

under Plan I-III to desegregate some of the 25 schools

left all-black under Plan II, are shorter than some Plan II

trips.

37

As Dr. Foster pointed out, the times and distances

of pupil transportation proposed under Plan I-III are

considerably less than many bus rides now taken by pupils

under desegregation decrees presently being effectuated in

Charlotte, North Carolina, and Nashville, Tennessee, among

others (Tr. 598-99). We agree with the district court that

the desegregation plans adopted in other cities do not

define the contours of the constitutional requirements in

Memphis (Tr. 626) . On the other hand, students are not so

much weaker in Memphis than elsewhere that a bus ride which

J

is educationally and physically acceptable in other communi-

«7

ties is simply beyond their endurance 1

Taking the evidence and testimony as a whole, we think

the district court's attachment to short bus rides is but a

vestige of its previous attitude (312 F. Supp. 1150) that

busing ought not be used at all to desegregate the Memphis

schools. On this record there is no valid ground related

to travel times and distances for preferring Plan II over

Plan I-III.

38

Conclusion

It is unfortunate that both the Memphis school system

and the district court have again stumbled and fallen, so

near the end of the road to constitutional compliance.

Plaintiffs are fully cognizant of the public pressures

upon both the school board and the court. We acknowledge

that after this Court's August 29, 1972 remand, the leader

ship of the Memphis public schools for the first time in

its history sought to encourage public acceptance of

desegregation; and that in the past year, the district

court has taken prompt action to effectuate and preserve

its decrees. Nevertheless, we can in no way commend or

condone the Board's suggestion that 21,000 black students

must be forever segregated in the Memphis schools, nor can

we accept the district court's ruling that this is consti

tutionally permissible.

The judgment below should be reversed with instructions

to complete the desegregation of all Memphis schools; this

Court should award attorneys' fees and costs to plaintiffs

in connection with this appeal. Northcross v. Board of

Educ. of Memphis, ___ U.S. ___ (1973) .

- 3 g -

Respectfully submitted,

7t aast^/'L / ' / ? S*

LOUIS R. LUCA!

WILLIAM E. CALDWELL

ELIJAH NOEL, JR.

Ratner, Sugarmon & Lucas

525 Commerce Title Building

Memphis, Tennessee 38103

JACK GREENBERG

JAMES M. NABRIT, III

NORMAN J. CHACHKIN

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

Attorneys for Appellants

CERTIFICATE OF SERVICE

I hereby certify that on this 13th day of August,

1973, I served two copies of the foregoing Brief for

Appellants in the above-captioned matter upon counsel of

record for appellees, by United States mail, air mail

special delivery postage prepaid, addressed to him as

follows:

Ernest Kelly, Jr., Esq.

Suite 900

Memphis Bank Building

Memphis, Tennessee 38103

40

APPENDIX A

' History of Case Since Remand

_____of August 29, 1972_____

The following is a chronological history of the

proceedings in this case since entry of this Court's remand

opinion of August 29, 1972, 466 F.2d 890. For the prior

history of this litigation, since its commencement on March 31,

1960, we respectfully refer the Court to Appendix A to our

Brief for Cross-Appellants in No. 72-1631, filed on or about

1/June 30, 1972. */

2/

Following the Court's August 29 remand the district

court, at plaintiffs' request, held a conference on

1/ At page 18a of that appendix it is noted that an en banc

motion to vacate the panel's stay of June 2, 1972 was still

pending. The motion was subsequently denied on July 5, 1972,

with three judges dissenting, 46 3 F.2.d 32 9. Oral argument

was heard by the panel, on an expedited basis, on July 15,

1972.

2/ Defendant Board's petition for certiorari was denied by

the Supreme Court on February 20, 1973, ____ U.S.____.

Plaintiffs' petition for certiorari from this Court's

November 24, 1972 order denying plaintiffs costs and attorneys'

fees on appeal was granted by the Supreme Court on June 4, 1973,

and this Court's judgment was vacated and the case remanded

for further consideration of the costs and attorneys' fees

U.S. ______.xssues.

September 5, 1972. The Court entered an order on September 6,

noting that the 1972-73 school year began on August 28 and

directing defendant Board to file a report by September 12

indicating a proposed timetable for implementing Plan A,

which this Court's August 29 opinion affirmed as an interim,

though constitutionally inadequate, desegregation measure.

(Implementation of Plan A had been stayed by this Court,

pending appeal.) Defendant Board was also directed to file

a report setting forth any changes in the previous plan of

operation which defendants had implemented withopt court

approval. In its September order, the Court further deferred

action on that part of this Court's remand directing preparation

of "a definite timetable providing for the establishment of

a fully unitary school system in the minimum time required

to devise and implement the necessary desegregation plan."

On September 12 the Board filed a motion/report stating

that Plan A could be implemented by November 17, but requesting

that implementation be delayed pending disposition of its

application for certiorari to the Supreme Court, or until «

the second semester for elementary grades and until Fall,

1973 for secondary grades. Following a conference on

September 13, the district court entered an order on

September 14 holding that defendants should not be required

2a

to implement Plan A prior to November 27 because, since

"Plan A was delayed by the stay [entered by this Court] for

a period of 88 days," the Board "should be allowed 88 days

from the dissolution of the stay to make all preparations

for implementation." The court directed preliminary pre

parations to begin immediately, but set a hearing on

defendants' request that implementation be further delayed.

The court also denied defendants' motion to defer desegre

gation pursuant to § 803, Education Amendments of 1972. (This

Court denied a similar stay request on September 21, 1972,

and the Supreme Court denied a stay on October 16, 1972.)

*»

The district court held an evidentiary hearing on

September 22, 1972 and entered a memorandum decision on

September 26 (with judgment on September 28) holding that

implementation of Plan A should be deferred until the second

semester (January, 1973), with the exception that the two

Plan A senior high pairings (Geeter/Fairley and Manassas/

3/

Frayser) were deferred until the 1973-74 school year. The

3/ Plaintiffs noticed an appeal from the decision to defer

the high school portion of Plan A until 1973-74, and moved in

this Court on or about September 29, 1972 for Carter relief

(Carter v. West Feliciana Parish School Board, 396 U.S. 226

(1969)) pending appeal and for an expedited appeal. On

October 19 this Court entered an order (Misc. No. 72-8077)

denying injunctive relief pending appeal but purportedly

granting an expedited appeal by directing the Clerk to

"schedule hearings for the December term." Oral argument was

3a -

I

court also disallowed certain previously implemented modifi

cations (a vague ’’stability1' transfer provision and

resurrection of the "pockets-and-coves" policy) which had not

received (or been submitted for) court approval and which

were found to be "in furtherance of protecting white majorities

and certain white patrons."

I

On October 18, following a conference on October 17,

the court entered an order disposing of requests for various

modifications of Plan A and setting a hearing for October 27

to determine the manner of compliance with this Court's

mandate (the "additional instruction") for a desegregation

timetable.

On November 1 the court entered a memorandum decision

(with implementing order on November 8) pertaining to Campus

elementary school (operated jointly by defendant Board and

Memphis State University), providing, pursuant to defendants'

3/ (cont.)

subsequently scheduled for December 13. Prior to oral

argument, plaintiffs moved to dismiss the appeal because of

the nearness of the second semester and because "the failure

of this Court to grant Carter relief. . . seriously affects

the probabilities of now obtaining the relief sought. . . ."

By order entered December 14, 1972 (No. 72-2053), the appeal

was dismissed.

4 a

motion, that Campus should not be closed as provided by Plan A.

but could be operated as a non-zoned school with a 50/50

(plus or minus 10%) racial ratio. The Dean of Memphis

State's College of Education was added as a party defendant.

On November 15, 1972, the court entered a memorandum

decision directing defendant Board to prepare a pupil locator

map for use in further desegregation planning and to commence

the planning process, with periodic reports to be made to the%

court. The court's schedule envisioned that a complete plan

would be implemented at the start of the 1973-74 school year

J

The court denied a motion by plaintiffs for additional

•3

elementary school desegregation for the second semester.

On December 14, 1972, the district court entered a

memorandum decision (incorporated in an order entered

February 26, 1973) disposing of various pending motions.

(1) The court granted a request of plaintiffs that areas

of Shelby County, particularly the Raleigh area, which would

come within the Board's jurisdiction for 1973-74 via civil

annexation by the City of Memphis, should be included in the

desegregation planning. (2) The court, on plaintiffs' motion,

amended the Campus school order to require periodic reports

to the court, but denied other requested amendments, including

one which would change the required racial ratio from 50/50 to

5a -

60% black/40% white to comport with the system-wide elementary

grade level ratio. (3) The court denied a motion by plain

tiffs to substitute a white school (Sherwood) for a desegre

gated school (Messick) in the Plan A pairing with a black

school (Hanley), although the court found "considerable merit"

to this proposal; at the Board's request, however, the court

modified Plan A by leaving Hanley unaffected (and segregated)»

for the second semester. (4) The court granted a motion by

defendants to change the Plan A assignment of predominantly

white Maury School (closed) students to all-black Carnes

elementary, and instead divided the Maury studen'ts between

two formerly white school zones (Snowden/Vollentine and Bruce)

with substantial white enrollments, because "the desegregation

effect on Carnes school would be de minimus." The court held

that "[o]ther efforts will be necessary to make a significant

4/

change in the desegregation of Carnes school." (5) The

court granted plaintiffs’ motion to pair, commencing with the

second semester, all-black White's Chapel elementary school

with predominantly white Coro Lake school, primarily because

of the finding "that under the present assignment system the

4/ Plan II, approved by the district court in the order

appealed from, leaves Carnes 98% black.

6a

less adequate facilities and overcrowded facilities are being

maintained for a black school whereas the predominantly white

5/school is under capacity." (6) The court denied defendants’

request for permission to pursue four site acquisition/

construction proposals.

On January 16, 1973 defendant Board filed a third-party

t

complaint against the City of Memphis, its Mayor and Directors

of Public Service and Police, seeking injunctive relief against

the threatened interposition, by these defendants, of a 1935

City Ordinance (§ 42-15, requiring "certificateg/of public

convenience and necessity" by those operating transportation

vehicles "for compensation") in an effort to interdict

5/ Thereafter, on January 16, 1973, white Coro Lake students

and their parents filed a motion to intervene for the purpose

of opposing the White's Chapel/Coro Lake pairing. At the

same time the attorney for the proposed white intervenors

appeared before the Board of Education and persuaded a majority

of its members to seek a change in the proposed pairing.

Accordingly, on January 17 the Board filed a motion seeking to

have the black students in the small Weaver school zone (to

be closed on January 24 pursuant to Plan A) transported to

Coro Lake in lieu of the pairing with White’s Chapel, which

was to be left all-black for at least the second semester.

The court held a hearing on January 19 and ruled at the

conclusion thereof (order entered February 26) that Plan A

would be modified in accordance with defendant Board's request;

White's Chapel remained unaffected by Plan A for the remainder

of the school year.

7a

implementation of Plan A scheduled for January 24, 1973.

(Plaintiffs subsequently filed a motion joining in the Board's

request for relief.) The court entered a show cause order

on an application for preliminary injunction, and a hearing

was held on January 18. The court ruled at the conclusion

of that hearing that the ordinance was not applicable to

school transportation by the Board, and its attempted appli

cation was an unconstitutional "anti-busing" effort on the

part of the City defendants. An appropriate injunction was

entered on January 19, 1973 and this Court denied the City's

Japplication for summary reversal or for a stay on January 23,

1973 (Misc. No. 73-8021). Plan A, as modified, went into

effect on January 24.

On February 1, 1973 the court entered an order requiring

the Board to adopt a plan for further desegregation by February

22 (subsequently extended to March 5 by order of February 15

and until March 12 by informal agreement). On March 12, 1973

defendant Board filed alternate plans of desegregation (three

elementary and two secondary), stating its preference for

Plan II (elementary and secondary). By order of March 16

(following a conference on March 15) the court directed the

Board to file maps illustrating the various plans filed, but

not designating the specific satellite zones (at the secondary

8a

level) which could be later devised from the pupil locator

data. The court set a briefing timetable and scheduled a

hearing on the plans for April 18, 1973.

On April 3, 1973 an order was entered, on plaintiffs'

motion of February 16, joining the Shelby County Board of

Education and its Superintendent as parties defendant to

this action for the limited purpose of considering joint

action between the City and County Boards for desegregation

of the Raleigh area (annexed to the City on December 31,

6/1972).

J

6/ Plaintiffs' February 16 motion to join the County Board

was prompted by difficulties which had arisen in the Raleigh

area annexation: although the entire Raleigh area was

scheduled for annexation by the City of Memphis on December 31,

1972, the northern one-third of the area was not annexed on

that date because of litigation initiated in the Shelby

County Chancery Court by residents who sought to avoid the

annexation. The result of this delay was that although most

of the pupils residing in the Raleigh area came with the

jurisdiction of the City Board, most of the school capacity

remained in the County. Following the County Board's joinder

(as reflected in the court’s May 3 memorandum decision), an

agreement was entered into between the City and County Boards

which, inter alia, allowed the Memphis Board to operate a

school (Brownsville) which remained in the County. Recently

the Chancery Court has ruled that the northern part of the

Raleigh area must be annexed by the City; if this decision

stands in the state courts, the plan approved by the district

court will have to be appropriately modified.

9a

On April 10, 1973, following an evidentiary hearing on

April 5, the court entered a memorandum decision in this case

and a removed action (C.A. No. 73-90) pertaining to requests

for relief by plaintiffs and the Board against the City of

Memphis, acting through its Mayor and Comptroller and the

members of its Legislative Council. The court held that the

City had unconstitutionally withheld from the Board $250,000

(the amount of the Board's busing contract for the spring

semester) of previously authorized funds for discriminatory

J

7/ It was learned at the January 18 hearing that the City,

in accordance with a City Council resolution, had withheld

from the Board funds designated for its use. Plaintiffs filed

a motion on January 26 to add as parties defendant the City's