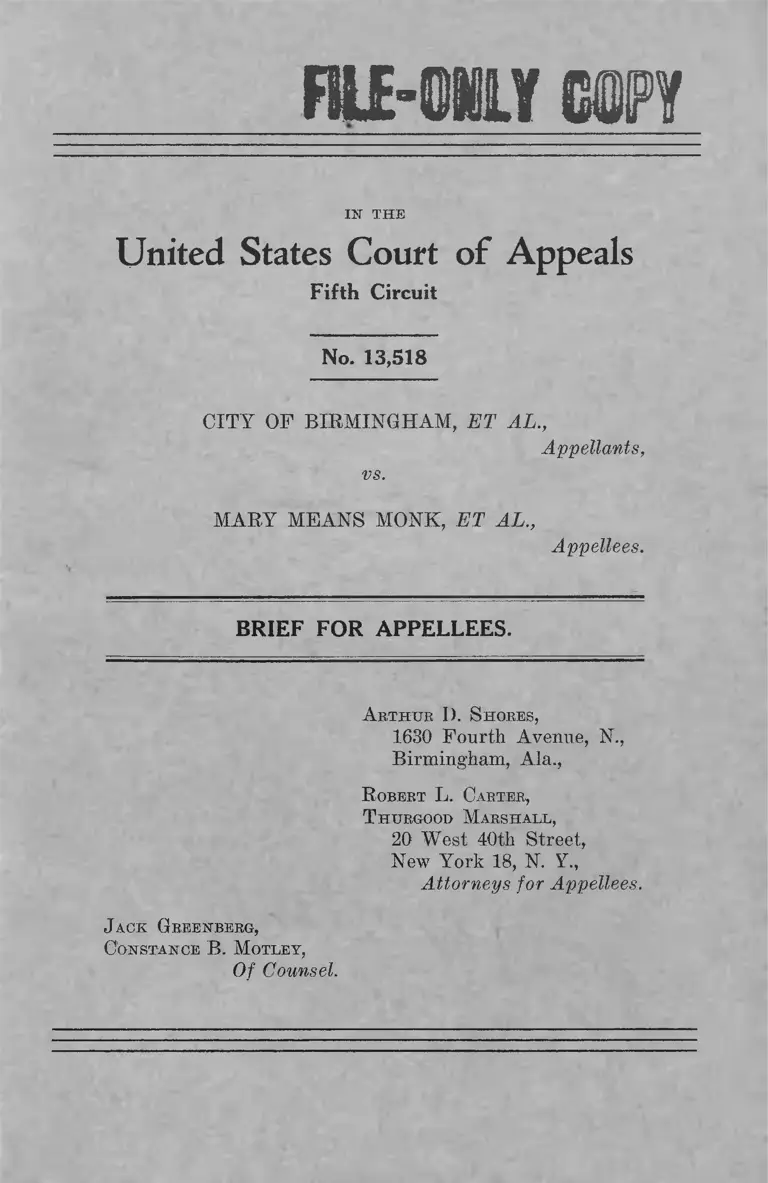

City of Birmingham v. Monk Brief for Appellees

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1949

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. City of Birmingham v. Monk Brief for Appellees, 1949. 7f4ad4ea-c69a-ee11-be37-000d3a574715. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/37a053af-f445-43d9-823d-171379d74154/city-of-birmingham-v-monk-brief-for-appellees. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

FILE-OILY G!FY

1ST T H E

United States Court of Appeals

Fifth Circuit

No. 13,518

CITY OF BIRMINGHAM, ET AL.,

Appellants,

vs.

MARY MEANS MONK, ET AL.,

Appellees.

BRIEF FOR APPELLEES.

A r t h u r I). S h o res ,

1630 Fourth Avenue, N.,

Birmingham, Ala.,

R obert L. C arter,

T hurgood M arshall ,

20 West 40th Street,

New York 18, N. Y„

Attorneys for Appellees.

J ack G reenberg ,

C onstance B. M otley ,

Of Counsel.

TA BLE O F CONTENTS

PAGE

Statement of Case ____________________________ 1

Summary of Argument------------------------ 5

Argument: __________________________________ 7

I. The right to use and occupy real estate as a

home is a civil right guaranteed and protected

by the Constitution and laws of the United

States ________________________________ 7

II. It is well settled that legislation conditioning

the right to use and occupy property solely

upon the basis of race, color, religion, or na

tional origin violates the Fourteenth Amend-

Conclusion ______________________________ _- 17

Appendix _________________________________ 19

T ab le o f C ases

Buchanan v. Warley, 245 TJ. S. 60, 74 ---------- 6, 7, 9,10,11,

12,13,14,15,16

City of Richmond v. Deans, C. C. A. 4th, 37 F. (2d)

712, 713, aff. 281 U. S. 704 _________ 7,10,12,13,14,15

Harmon v. Tyler, 273 U. S. 668 _______ 7,10,13,14,15,16

Holden v. Hardy, 169 IT. S. 366, 391, 42 L. ed. 780, 790,

18 Sup. Ct. Rep. 383 _______________ _________ 11

Hurd v. Hodge, 334 U. S. 24_____________________ 16

Matthews v. City of Birmingham (Civil Action No.

6046) _____________________________________

Missouri ex rel. Gaines v. Canada, 305 U. S. 337 —

2,3

5

11

PAGE

Oyama v. California, 332 U. S. 633________________ 7,16

Shelley v. Kraemer, 334 U. S. 1, 12 -_____________7,16

Sipuel v. Board of Regents, 332 IT. S. 631__________ 5

Strander v. West Virginia, 100 IT. S. 303, 308 _______ 9

Sweatt v. Painter, 94 L. Ed. (Adv. Op.) 767 _______ 5

A u th orities C ited

Blackstone’s Commentaries ___________ __________ 7

Congressional Globe, 39th Congress, 1st Session,

Part 1 _______________ 1.___________________ 8

Flack, Adoption of the Fourteenth Amendment (1908)- 8

S tatu tes

8 United States Code 41________________________ 1

8 United States Code 42________________________ 1, 7

General City Code of Birmingham (1944)

Section 1604 ____________________ ______ 1, 2, 4, 6

Section 1605 ______________________________ 1, 2

(Chapter 57) _____________________________ 4, 6

(Supp. Ord. No. 709-F) ____________________ 1,4,6

IN THE

U n i t e d S ta t e s C o u r t of A p p e a l s

F if th C ircu it

No. 13,518

C ity op B ir m in g h a m , et al.,

Appellants,

vs.

M ary M eans M o n k , et al.,

Appellees.

BRIEF FOR APPELLEES.

Statement of the Case.

This action was commenced on September 28, 1949, by a

complaint seeking an order declaring Ordinances 709F,

1604 and 1605 of the General Code of Birmingham to be un

constitutional because they are in violation of the Four

teenth Amendment and Sections 41 and 42 of Title 8 of the

United States Code. The complaint also sought an injunc

tion against the enforcement of the ordinances (R. 1-9).

Copies of the ordinances were attached to the complaint

(R. 9-15). In general they required residential segrega

tion on the basis of race. They exempted servants in the

employ of occupants. They prohibited “ a member of the

colored race” from occupying property in an area “ gen

erally and historically recognized at the time as an area

for occupancy by members of the white race” (R. 11). The

2

ordinances also prohibited occnpancy by white persons of

property in so-called colored areas.

The answer did not deny the material allegations of

fact. Appellants denied that appellee was prevented from

building her home solely because of her race, and alleged

that the ordinances were not unconstitutional.

A trial on the merits was held and on December 16, 1949

a final order was issued enjoining the enforcement of the

ordinances in question (K. 263-265).

On August 4, 1947, the District Court of the United

States for the Southern District of Alabama in the case

of Matthews v. City of Birmingham (Civil Action No. 6046)

issued a final order which provided in part as follows:

“ 3. That the defendant, the City of Birmingham,

its officers, agents, servants and employees, be and

they are hereby enjoined and restrained from di

rectly or indirectly enforcing or attempting to en

force or attempting to do any other act under color

of Sections 1604 and 1605 of the General City Code

of the City of Birmingham in reference to the right

of the plaintiffs to use or occupy the property de

scribed as Lots 11 and 12 in Block 45 in the survey

of North Smithfield situated in the City of Birming

ham as a dwelling, or from interfering directly or

indirectly with the plaintiffs’ right to so use or

occupy said property or permit other members of

the Negro race to use or occupy the same; and, the

defendant, its officers, agents, servants and em

ployees are further enjoined and restrained from

refusing to the plaintiffs, or any other person of the

Negro race, his or their application to occupy and

reside on said property upon the ground of said

applicant’s race;” 1

1 A certified copy of the Findings of Fact, Conclusions of Law and

Decree of the Court in the Matthews case has been deposited with the

Clerk and is copied in the Appendix to this brief.

3

Despite the decision in the Matthews case the City of

Birmingham continued to enforce these ordinances. W.

Cooper Green, President of the Commission of the City of

Birmingham, testified:

“ Q. Knowing the decision of the Court in that

particular case, what action did you and the Com

mission take concerning these zoning ordinances?

A. We still upheld the ordinances, because I believe

this matter goes beyond the written law, in the in

terest of peace and harmony and good will and racial

happiness. I think that we are doing what we feel

is right.

Q. And you believe it goes beyond the Consti

tution of the United States! A. I said beyond the

written law, whatever it is.

Q. Does that include the Constitution of the

United States? A. The written law of the land, be

cause I think this thing creates bloodshed. Under

the police powers to keep law and order, we have

that authority. There are some things that law can

not cover, and I think this is one of them. It was

created not by the City Commission, not by you nor

me, it was created by the people, who were created

by the good Lord.

Q. At the present time what is there that pre

vents the Plaintiffs in this case from continuing to

build their home on the land they bought other than

this ordinance and the enforcement of it by you and

the Commission, what else is there that prevents

them from building and living in their own home

today? A. Nothing except the ordinance, that I

know of.

Q. And you put the ordinance above the Consti

tution of the United States? A. No, I didn’t say

that” (R. 158-159).

The appellee Mary Means Monk purchased a plot of

land in Birmingham, Alabama for $2,000 (R. 54). The

warranty deed for the property was introduced in evidence

4

(R. 55-58). The land was purchased for the purpose of

building a dwelling on it, and was to be occupied by appel

lee and her family (R. 53, 58). A contract was made with

a contractor to build a home at a cost of $11,000 exclusive

of the land (R. 58, 65) with a down payment of $2,000 (R.

59). It was stipulated that the other appellees had pur

chased lots in the same area for the purpose of building

homes for themselves (R. 71, 74).

Appellee Mary Means Monk presented her plans and

specifications to the building inspector of Birmingham. She

testified that he approved the plans but refused to issue a

permit to build. After referring the matter to Commis

sioner James L. Morgan he finally refused to issue the per

mit (R. 59-60).

By stipulation of counsel it was agreed that if Building

Inspector H. E. Hagood, who was ill, were present he would

have testified in substance:

“ That H. E. Hagood examined the plans and

specification of Plaintiff, Mary Means Monk, and

found the said plans and specification were in com

pliance with the structural requirements of the Build

ing Code of the City of Birmingham.

“ That Plaintiff, Mary Means Monk, made appli

cation for a building permit, but that the said issu

ance of the said building permit was refused, because

the purpose for which the said property was to be

used would violate Chapter 57, viz. Section 1604 and

Ordinance 709F, General City Code of the City of

Birmingham, 1944, in that the property was zoned

for whites” (R. 49).

There is no question that the property is in the area set

aside for “ white” occupancy. However, the area across

the street and on three sides of the property here involved

is set aside for and occupied by Negroes (R. 89, 90).

5

The zoning Board of Birmingham is under the direction

of the Commission of Birmingham (R. 92). The building

inspector is under the direct supervision of Commissioner

Morgan (R. 92). The policy of the Commission is to refuse

to issue permits to Negroes who propose to build and occupy

homes in areas designated for white occupancy (R. 92, 244).

This policy is pursuant to enforcement of the ordinances

(R. 49, 67, 71-74, 92).

United States District Judge Cla ren ce M u l l in s decided

the ease from the bench and filed a formal opinion on

December 16, 1949 (R. 24a-262). He found that none of

the appellees would be permitted to build houses on their

property solely because the provisions of said ordinances

limited the occupancy of these properties to members of

the white race (R. 252) ; that it has been the established

policy of the City to deny building permits to construct

residences for Negro occupancy in districts that are zoned

for white occupancy (R. 252). The Court noted the three

decisions of the United States Supreme Court holding sim

ilar ordinances invalid and similar decisions of the highest

courts of several of the Southern states. The Court, there

fore, declared the ordinances unconstitutional and ordered

the injunction to issue (R. 263).

Summary of Argument.

The right which appellee, Mary Means Monk, seeks to

enforce is a personal right. The right which each of the

other appellees seeks to enforce is personal to each of them.

The same is true as to each other member of the class they

represent.

Missouri ax rel. Gaines v. Canada, 305 U. S. 33^;

Sipuel v. Board of Regents, 332 U. S. 631;

Sweatt v. Pa,inter, 94 L. Ed. (Adv. Op.) 767.

6

The right that appellees assert is their civil right to oc

cupy their property as a home—the same right recognized

by this Court in Buchanan v. Warley:

“ The Fourteenth Amendment protects life, lib

erty, and property from invasion by the States with

out due process of law. Property is more than the

mere thing which a person owns. It is elementary

that it includes the right to acquire, use, and dispose

of it. The Constitution protects these essential at

tributes of property * * * ” (245 U. S. 60, 74).

Appellee, Mary Means Monk, purchased a plot of land

in the City of Birmingham for the purpose of building a

home for herself and her family. The facts show that there

was a willing seller and a willing purchaser. She hired a

contractor to build a $11,000 home, a down payment of

$2,000.00 was made and plans and specifications were

drawn. These plans and specifications were, in due course,

presented to the building inspector, who found them to be

in proper order. However, a building permit was refused.

If appellee had not happened to be a Negro she would have

been given a permit to build her home on her own land.

The only reason appellee was refused a permit was be

cause the purpose for which “ said property was to be used

would violate chapter 57, viz. section 1604 and ordinance

709F, General City Code of the City of Birmingham, 1944,

in that the property was zoned for whites” (R. 49).

Appellants sought to justify the enforcement of the

ordinances by offering evidence which, it is alleged, would

show that there had been violence in areas where other

Negroes had moved, that there would be a lowering of

property values and that there would be a lowering of taxes.

This testimony was excluded by the District Judge because

7

these contentions “ were not considered material to the issue

of constitutionality of such ordinances” (R. 265-266).

The individual rights which appellees assert are clearly

protected by our Constitution. Ordinances similar to those

in this case have uniformly been held to be unconstitutional

by the United States Supreme Court, and the highest courts

of many states. The alleged justifications for such ordi

nances have all been disposed of by other cases. There is

no longer any legal justification for such ordinances.

Buchanan v. Warley, 245 U. S. 60;

Harmon v. Tyler, 273 U. S. 668;

City of Richmond v. Deans, 281 U. S. 704.

See also:

Oyama v. California, 332 U. S. 633;

Shelley v. Kraemer, 334 U. S. 1.

A R G U M E N T .

I.

The right to use and occupy real estate as a home

is a civil right guaranteed and protected by the Consti

tution and law s o f the U nited States.

Blackstone pointed out that the third absolute right “ is

that of property, which consists in the free use, enjoyment,

and disposal of all his acquisitions, without any control or

diminution, save only by the laws of the land ’ ’.2 This right

is expressly protected by the Fourteenth Amendment and

the Civil Rights Acts3 against invasion by the states on

racial grounds.

2 Blackstone’s Commentaries, p. 138.

3 See: 8 U. S. C. 42.

8

The Congressional debates after the adoption of the

Thirteenth Amendment and preceding the enactment of

the Civil Eights Act of 1866 show that Congress intended

to protect the fundamental civil rights of the freedmen.

High on the list of rights to be protected was the right to

own property. Some doubts were expressed by the op

ponents of the measure as to its constitutionality, and par

ticularly the right of Congress to confer citizenship upon

the former slaves without an amendment.4 But neither the

proponents of the Civil Rights Act nor its opponents

doubted that citizens of the United States had an inherent

right to acquire, own and occupy property.5 After the

enactment of the Fourteenth Amendment, Congress reen

acted the Civils Rights Act with a few modifications, ex

pressly stipulating therein:

“ All citizens of the United States shall have the

same right in every State and Territory as is en

joyed by white citizens thereof to inherit, purchase,

lease, sell, hold and convey real and personal prop

erty.” 0

Throughout the debates on the Amendment and the Civil

Rights Bill there is a clear perception that freedom for

the former slave without protection of his fundamental

right to own real or personal property was meaningless.

One of the Senators cited as an example of the oppression

from which the freedmen must be protected the fact that in

1866 in Georgia, “ if a black man sleeps in a house over

night, it is only by leave of a white man, ’ ’7 and another

4 Flack, Adoption of the Fourteenth Amendment (John Hopkins

Press, 1908), p. 21.

8 See: Debate between Senators Cowan and Trumbull, Congres

sional Globe, 39th Cong., 1st Session, Part 1, pp. 499-500.

0 8 U. S. C. 42.

7 Congressional Globe, 39th Cong., 1st Session, Part 1, p. 589.

9

asked: “ Is a freeman to be deprived of the right of acquir

ing property, having a family, a wife, children, home ? ” 8

In 1879 this Court construed the Fourteenth Amendment

as containing a positive immunity for the newly freed

slaves against “ legal discriminations * * * lessening the

security of their enjoyment of the rights which others en

joy’’9 and in 1917 this Court construed the Civil Eights

Act as dealing “ with those fundamental rights in property

which it was intended to secure upon the same terms to

citizens of every race and color.” 10

The right that appelles assert is their civil right to oc

cupy their property as a home—the same right recognized

by this Court in Buchanan v. Warley:

“ The Fourteenth Amendment protects life, lib

erty, and property from invasion by the States with

out due process of law. Property is more than the

mere thing which a person owns. It is elementary

that it includes the right to acquire, use and dispose

of it. The Constitution protects these essential at

tributes of property # * * ” (245 U. S. 60, 74).

II.

It is w ell settled that legislation conditioning the

right to use and occupy property solely upon the basis

of race, color, religion, or national origin violates the

Fourteenth Am endm ent.

Racial restrictions by states of the right to acquire, use,

and dispose of property are in direct conflict with the Con

stitution of the United States. The first efforts to establish

racial residential segregation were made by means of

8 Senator Howard, Ibid., p. 504.

9 Strander v. W est Virginia, 100 U. S. 303, 308.

10 Buchanan v. Warley, 245 U. S. 60, 79.

10

municipal ordinances which attempted to establish racial

zones. The Supreme Court, in three different cases, has

clearly established the principle that the purchase, occu

pancy, and sale of property may not be inhibited by the

states solely because of the race or color of the proposed

occupant of the premises.11

In Buchanan v. Warley, supra, an ordinance of the City

of Louisville, Kentucky, prohibited the occupancy of lots by

colored persons in blocks where a majority of the residences

were occupied by white persons and contained the same pro

hibition as to white persons in blocks where the majority

of houses were occupied by colored persons. Buchanan

brought an action for specific enforcement of a contract of

sale against Warley, a Negro, who set up as a defense a

provision in the contract excusing him from performance

unless he should have the right under the laws of Kentucky

and of Louisville to occupy the property as a residence and

contended that the ordinance prevented him from occupying

the property. Buchanan replied that the ordinance was in

violation of the Fourteenth Amendment.

In a unanimous opinion by Mr. Justice D ay, the Supreme

Court decided the following question:

“ The concrete question here is: May the occu

pancy, and, necessarily, the purchase and sale of

property of which occupancy is an incident, be in

hibited by the states, or by one of its municipalities,

solely because of the color of the proposed occupant

of the premises? That one may dispose of his prop

erty, subject only to the control of lawful enactments

curtailing that right in the public interest, must be

conceded. The question now presented makes it

pertinent to inquire into the constitutional right of

the white man to sell his property to a colored man,

11 City of Richmond v. Deans, 281 U. S. 704; Harmon v. Tyler,

273 U. S. 668; Buchanan v. Warley, 245 U. S. 60.

11

having in view the legal status of the purchaser and

occupant” (245 U. 8. 60, at p. 75).

The decision in the Buchanan case disposed of all of the

arguments seeking to establish the right of a state to re

strict the sale of property by excluding prospective occu

pants because of race or color:

Use and occupancy is an integral element of ownership

of property:

“ * * * Property is more than the mere thing

which a person owns. It is elementary that it in

cludes the right to acquire, use, and dispose of it.

The Constitution protects these essential attributes

of property. Holden v. Hardy, 169 U. S. 366, 391,

42 L. ed. 780, 790, 18 Sup. Ct. Rep. 383. Property

consists of the free use, enjoyment, and disposal of

a person’s acquisitions without control or diminution

save by the law of the land. 1 Cooley’s Bl. Com.

127” (245 U. 8. 60, at p. 74).

Racial residential legislation can not be justified as a

proper exercise of police power:

“ We pass, then, to a consideration of the case

upon its merits. This ordinance prevents the occu

pancy of a lot in the city of Louisville by a person

of color in a block where the greater number of resi

dences are occupied by white persons; where such a

majority exists, colored persons are excluded. This

interdiction is based wholly upon color; simply that,

and nothing more * # *

“ This drastic measure is sought to be justified

under the authority of the state in the exercise of

the police power. It is said such legislation tends

to promote the public peace by preventing racial con

flicts; that it tends to maintain racial purity; that

it prevents the deterioration of property owned and

occupied by white people, which deterioration, it is

12

contended, is sure to follow the occupancy of ad

jacent premises by persons of color.

“ It is urged that this proposed segregation will

promote the public peace by preventing race con

flicts. Desirable as this is, and important as is the

preservation of the public peace, this aim cannot be

accomplished by laws or ordinances which deny

rights created or protected by the Federal Consti

tution” (245 U. S. 60, at p. 81).

Bace is not a measure of depreciation of property:

“ It is said that such acquisitions by colored per

sons depreciate property owned in the neighborhood

by white persons. But property may be acquired by

undersirable white neighbors, or put to disagreeable

though lawful uses with like results” (245 IT. S. 60,

at p. 82).

The issue of residential segregation on the basis of race

was squarely met and disposed of in the Buchanan case.

Each of the arguments in favor of racial segregation was

carefully considered and the Supreme Court, in determin

ing the conflict of these purposes with our Constitution,

concluded:

“ That there exists a serious and difficult problem

arising from a feeling of race hostility which the

law is powerless to control, and which it must give a

measure of consideration, may be freely admitted.

But its solution cannot be promoted by depriving

citizens of their constitutional rights and privileges”

(245 IT. S. 60, at pp. 80-81).

The determination of the Supreme Court to invalidate

racial residential segregation by state action regardless of

the alleged justification for such action is clear from two

later cases.

In the case of City of Richmond v. Deans, a Negro who

held a contract to purchase property brought an action in

13

the United States District Court seeking to enjoin the en

forcement of an ordinance prohibiting persons from using

as a residence any building on a street where the majority

of the residences were occupied by those whom they were

forbidden to marry under Virginia’s miscegenation statute.

The Circuit Court of Appeals, in affirming the judgment

of the trial court, pointed out: “ Attempt is made to dis

tinguish the case at bar from these cases on the ground

that the zoning ordinance here under consideration bases

its interdiction on the legal prohibition of intermarriage

and not on race or color; but, as the legal prohibition of

intermarriage is itself based on race, the question here, in

final analysis, is identical with that which the Supreme

Court has twice decided in the cases cited (Buchanan v.

Warley and Harmon v. Tyler).” 12 The Supreme Court

affirmed this judgment by a Per Curiam decision.13

The principles of the Buchanan case have also been ap

plied in cases involving the action of the legislature coupled

with the failure of individuals to act. In Harmon v. Tyler,

a Louisiana statute purported to confer upon all munici

palities the authority to enact segregation laws, and another

statute of that state made it unlawful in municipalities hav

ing a population of more than 25,000 for any white person

to establish his residence on any property located in a

Negro community without the written consent of a majority

of the Negro inhabitants thereof, or for any Negro to estab

lish his residence on any property located in a white com

munity without the written consent of a majority of the

white persons inhabiting the community.

An ordinance of the City of New Orleans made it unlaw

ful for a Negro to establish his residence in a white com-

12 City of Richmond v. Deans, C. C. A.—4th, 3/ F. (2d) 712, 713.

18 281 U. S. 704.

14

/

munity, or for a white person to establish his residence in

a Negro community, without the written consent of a major

ity of the persons of the opposite race inhabiting the com

munity in question. Plaintiff, alleging that defendant was

about to rent a portion of his property in a community in

habited principally by white persons to Negro tenants

without the consent required by the statute and the ordi

nance, prayed for a rule to show cause why the same should

not be restrained.

Defendant contended that the statutes and the ordinance

were violative of the due process clause of the Fourteenth

Amendment. The trial court sustained defendant’s posi

tion. On appeal, the Supreme Court of Louisiana reversed,

and upheld the legislation. On appeal to the Supreme

Court, the decision of the Supreme Court of Louisiana was

reversed on authority of Buchanan v. Warley. A like dis

position of the same legislation was had in the Circuit

Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit in an independent

case.

In the instant case, all of the alleged evils claimed to

flow from mixed residential areas which are relied upon

for judicial enforcement of racial restrictive covenants

were advanced in the Buchanan and the other two cases as

justification for legislative action to enforce residential

segregation. In the Buchanan case, this Court dealt with

each of the assumed evils and held that they could not be

solved by segregated residential areas and did not warrant

the type of remedy sought to be justified. Efforts to cir

cumvent this decision have been summarily disposed of by

the Supreme Court.14

It is, therefore, clear that the District Judge was cor

rect in excluding certain testimony of the appellants on

14 Harmon v. Tyler and City of Richmond v. Deans, supra.

15

these points. If there could have been any doubt as to the

correctness of these rulings this doubt is completely dis

pelled by a reading of the inadmissible, unrealiable and

scurrilous materials on these points in the brief for ap

pellants.

The right appellee here asserts is the civil right to

occupy their property as a home—the same right which

was recognized and enforced in Buchanan v. Warley.

Appellants seek to distinguish the instant case from

Buchanan v. Warley on the ground that the Buchanan case

was limited to the right of a white man to dispose of his

property and this case involves the right of a Negro to

occupy his property. If there could have been any doubt

that the Buchanan case covered both rights, this doubt

was disposed of in the case of City of Richmond v. Beans

(supra,) :

“ The precise question before this Court in both

the Buchanan and Harmon cases, involved the rights

of white sellers to dispose of their properties free

from restrictions as to potential purchasers based on

considerations of race or color. But that such legis

lation is also offensive to the rights of those desir

ing to acquire and occupy property and barred on

grounds of race or color, is clear, not only from the

language of the opinion in Buchanan v. Warley

(U. S.) supra, but from this Court’s disposition of

the case of Richmond v. Deans, 281 U. S. 704, 74 L. ed.

1128, 50 S. Ct. 407 (1930). There, a Negro, barred

from the occupancy of certain property by the terms

of an ordinance similar to that in the Buchanan

case, sought injunctive relief in the federal courts to

enjoin the enforcement of the ordinance on the

grounds that its provisions violated the terms of the

Fourteenth Amendment. Such relief was granted,

and this Court affirmed, finding the citation of

Buchanan v. Warley (IJ. S.) supra and Harmon v.

16

Tyler, 273 U. S. 668, 71 L. ed. 831, 47 S. Ct. 471,

supra, sufficient to support its judgment” (Shelley

v. Kraemer, 334 IT. S. 1, 12).

The Supreme Court in the Shelley case (334 IT. S. 1,

p. 12, fn. 11) and the District Judge in this case (R. 261-

262) noted that the courts of at least six Southern states

have invalidated similar ordinances.

In deciding the Shelley case (supra) and Hurd v.

Hodge,15 the Supreme Court reaffirmed the rationale of

Buchanan v. Warley and the other ordinance cases and

pointed out the recent decisions of the Court on this point:

“ * * # Only recently this Court has had occasion

to declare that a state law which denied equal enjoy

ment of property rights to a designated class of

citizens of specified race and ancestry, was not a

legitimate exercise of the state’s police power but

violated the guaranty of the equal protection of the

laws.” Oyama v. California, 332 IT. S. 633, ante,

249, 68 S. Ct. 269 (1948).w

There is no question in this case that all of the city

officials are enforcing these ordinances. The commission

has overall supervision of the City of Birmingham (R. 124).

The building inspector refused the permit to build pur

suant to the policy of the commission of the City of Bir

mingham: “ That is no permits are issued to Negroes who

propose to build homes and occupy them themselves in

white residential sections” (R. 92). Appellants only de

fense is that the ordinances are constitutional.

The rights of appellees herein are personal rights.

These rights are fully protected by the Constitution and

laws of the United States. These constitutional rights

15 334 U. S. 24.

18 Ibid, at p. 21.

17

cannot be conditioned upon the threats of violence by either

the lawless elements of Birmingham nor by threats of public

officials of that city.

Our democracy cannot be constricted by lawless ele

ments from within or without our borders. The City of

Birmingham has no right to limit constitutional rights

of law abiding citizens who happen to be Negroes in favor

of threats from some lawless elements who happen to be

white.

Conclusion.

The law in this case is clear. There are no eases to

the contrary. The rulings of the District Judge followed

the clear mandate of the Supreme Court in the three deci

sions invalidating racial segregation ordinances. These

decisions have been reinforced by later decisions on the

question of racial distinctions by governmental agencies.

W h er efo r e , it is respectfully submitted that the judg

ment of the United States District Court for the Northern

District of Alabama should be affirmed.

A r t h u r D. S h o res ,

R obert L. Carter,

T hurgood M arshall ,

Attorneys for Appellees.

J ack G reenberg ,

C onstance B. M otley ,

Of Counsel.

19

A P P E N D I X .

1ST T H E

DISTRICT COURT OF THE UNITED STATES

F oe t h e S o u t h e r n D iv isio n of t h e N o r th er n D istrict

oe A labama

S a m u el M a tth ew s a n d

E ssie M ae M a t t h e w s ,

Plaintiffs,

vs.

C ity o f B ir m in g h a m , a Municipal

Corporation of Alabama,

Defendant.

F in d in gs o f F act, C onclusions o f L aw and D ecree

This action was tried by the court without a jury on evi

dence taken orally before the court, and after argument,

the matter was submitted. The plaintiffs agreed upon the

trial that they would waive the class action feature of the

complaint and it was agreed by both parties that the cause

was finally submitted on the prayer for a permanent in

junction and declaratory judgment.

The matter now being considered and understood, the

court makes the following findings of fact, conclusions of

law and decree.

F in d in g s of F act

1. This is the second suit brought in this court by the

plaintiffs seeking to declare Sections 1604 and 1605 of the

General Code of Birmingham, 1944, unconstitutional on the

C iv il A ction

No. 6046

20

Appendix

ground that they are violative of the Fourteenth Amend

ment to the Constitution of the United States. These sec

tions constitute provisions of the General Zoning Ordinance

of the City of Birmingham, Section 1604 providing that no

building or part thereof in certain residence districts shall

be occupied or used by a person of the negro race and Sec

tion 1605 providing that no building or part thereof in cer

tain residence districts shall be occupied or used by a per

son of the white race. In the prior suit, No. 5903 in this

court, after trial, the action was dismissed on the ground

that the suit was prematurely brought. In that case it ap

peared that the dwelling of the plaintiffs had not been

completed, that the plaintiffs had not complied with the

valid provisions of the Building Code of said City in that

they had not obtained a framing inspection and a final in

spection of the dwelling by the building inspector. The

plaintiffs not having complied with the provisions of the

Building Code which were admittedly valid, I was of the

opinion that the plaintiffs could not at that time raise the

question of the constitutionality of said zoning provisions of

the City Code. It now appears from the evidence in the

present case that the plaintiffs have finally completed their

dwelling, that said building has been finally inspected and

approved in every detail and manner by the building in

spector of said City, that the plaintiffs have demanded a cer

tificate of occupancy, which has been refused, and that the

plaintiffs are now in a position to question the constitu

tionality of said zoning provisions.

2. The plaintiffs are negro citizens of the United States,

State of Alabama, and residents of the City of Birmingham,

Jefferson County, Alabama, within the Southern Division

of the Northern District of Alabama. The defendant is a

21

Appendix

municipal corporation in the State of Alabama, located in

Jefferson County, Alabama, within the Southern Division

of the Northern District of Alabama.

3. Plaintiffs, on or about December 11, 1945, purchased

and received a warranty deed to the property described in

the complaint, paying $500 for the same as vacant lots.

Subsequently, plaintiffs applied to the City of Birmingham

for a building permit to erect and occupy a frame dwelling

on said property and for a certificate of occupancy from the

defendant. Plaintiffs received a building permit and con

structed a dwelling on said property. During the course of

the construction of said building, H. E. Hagood, the build

ing inspector of the defendant, called Samuel Matthews,

one of the plaintiffs, to his office and told him that the

property was zoned for white occupancy and that he could

not occupy the same without violating the zoning sections

in question. The construction cost of the dwelling was

$3750, making a total cost of the property to the plaintiffs

in the amount of $4250. The reasonable market value of

the property is $4500. The plaintiffs intend to occupy the

property as a residence.

4. The plaintiffs finally completed the dwelling in ques

tion on or before July 12, 1947. It was finally inspected

by an assistant building inspector of the defendant on that

date and the construction was by him. fully approved as

being in accordance with the provisions of the Building

Code of said City. The assistant building inspector in

structed the plaintiffs to report to the building inspector’s

office and pay the additional fees due the City, these fees

being based upon the cost of the construction. The plain

tiffs paid these additional fees to the defendant on July 15,

1947, and at that time they were granted what is referred

22

Appendix

to as a further or supplemental permit. Within a day or

so thereafter, the plaintiffs, acting through their attorney,

Arthur Shores, demanded of H. E. Hagood, the building

inspector and chief enforcement officer of the zoning ordi

nances of said City, a certificate of occupancy. This certifi

cate was refused because the issuance thereof would consti

tute a violation of the zoning sections now in question,

these sections being based solely upon race or color. Subse

quently, and two or three days later, a representative of

the plaintiffs again applied to said building inspector for

a certificate of occupancy and the same was again refused,

and thereafter the present suit was filed.

5. Section 1635 and Section 1637 of the Zoning Chapter

of the General City Code read as follows:

“ Sec. 1635. R equired for N ew oe R epaired B u ild

in g s .

“ A certificate of occupancy, either for the whole

or a part of a new building, or for alteration of an

existing building, shall be applied for, coincident

with the application for a building permit, and shall

be issued within ten days after the erection or altera

tion of such building or part shall have been com

pleted in conformity with the provisions of this

chapter. (Ord. 1101-C, Sec. 39.) ”

“ Sec, 1637. M u st B e I ssued B efore U se of P rop

e r t y .

“ No vacant land shall be occupied or used, and

no structure hereafter erected, structurally altered

or changed in use shall be used or changed in use

until a certificate of occupancy shall have been issued

by the administrative officer. (Ord. 1101-C, Sec,

39.)”

23

Appendix

6. The defendant now contends that this suit was pre

maturely brought because the City had the right to delay

the issuance of the certificate of occupancy for a period of

ten days as provided for in Section 1635, above quoted.

The evidence conclusively shows and I find that said City

does not issue certificates of occupancy in accordance with

the provisions of said Section 1635. The evidence, with

out dispute, shows that the City has never issued certifi

cates of occupancy under said section, but that customarily,

when a certificate of occupancy is requested, the building

permit is stamped on the back “ Approved”, giving the

date of the final building inspection. The evidence further

shows that in at least sixty per cent of the cases where a

certificate of occupancy would be appropriate, the building

inspector does not even enter “ Approved” on the back of

the building permit; that it is customary in at least sixty

per cent of the cases where a building has been completed,

for the property owner, whether white or negro, to enter

into the occupancy of the property without the word “ Ap

proved” being entered by the building inspector on the

building permit and that this practice has never been ques

tioned by said City. In the remaining forty per cent of the

cases, the word “ Approved” is stamped on the back of the

building permit by the building inspector and this approval

is, as a general rule, only entered for the purpose of pro

viding evidence of satisfactory completion of a structure

in accordance with the requirements of the Building Code

and where the builder particularly desires and requests

such approval. The net result of the procedure followed

by said City is that certificates of occupancy, as required

by Section 1635, are never issued in any case or transaction;

that the customary practice, if a certificate of occupancy is

requested, is merely to stamp “ Approved” on the back of

24

Appendix

the building permit after the final building inspection has

been made, and this approval is treated by the City as

obviating the issuance of a certificate of occupancy. The

City does not enforce the provisions of Section 1637 of the

zoning chapter of said Code for the reason that they never

issue certificates of occupancy as is required by Section

1635. In the present case, the evidence shows and I find

that the defendant refused to mark “ Approved” on the

back of the building permit of the plaintiffs as is custo

marily done where an owner requests a certificate of occu

pancy, and that said City thereby denied the plaintiffs a

certificate of occupancy and that this denial was based

solely upon the ground that Section 1604 of the Zoning

Chapter of the General City Code of the defendant pro

hibited negroes from occupying the property in question

as a dwelling. The approval or certificate of occupancy

having been refused to the plaintiffs on the ground that they

were members of the negro race, there was no occasion for

them to wait for the ten day period provided for in Section

1635.

7. Said Section 1604 of the said Zoning Chapter pro

hibits the use and occupancy of the property involved by

members of the negro race regardless of whether a certi

ficate of occupancy is issued, and the violation of the pro

visions of said section would subject them to fine and

imprisonment and each day that they occupied said prop

erty would constitute a separate and distinct criminal

offense under the provisions of Section 1600 of the Zoning

Chapter of the General City Code of the defendant.

8. The value of the property of the plaintiffs has depre

ciated and will rapidly depreciate if they are not permitted

to occupy the property as a residence, and they will suffer

irreparable damage.

25

Appendix

C onclusion 's of L aw

1. Where a party has complied with all of the valid

provisions of a municipal building code, a suit attacking

the constitutionality of an ordinance which prohibits the

use or occupancy of property solely on the basis of race

or color is not prematurely brought. Where a statute

clearly and immediately affects property rights of a citizen,

he has an immediate and present controversy with reference

to the validity of such a statute, without first subjecting

himself to the severe penalties provided by such a statute.

Terrace v. Thompson, 263 U. S, 197;

Pierce v. Society of Sisters, 268 U. S. 510;

Euclid v. Ambler Co., 272 U. 8. 365.

2. Property is more than a mere thing which a person

owns and includes the right to acquire, freely use, and

dispose of it.

Buchanan v. Warley, 245 U. S. 60.

3. Since the evidence conclusively shows that Sections

1635 and 1637, which require a certificate of occupancy, are

not enforced by the defendant as to either whites or

negroes, the enforcement of Sections 1635 and 1637 as

against these particular plaintiffs would be unconstitu

tional. Tick Wo v. Hopkins, 118 II. S. 373. Therefore,

Section 1604, which prohibits negro occupancy of plaintiffs ’

property, is the only barrier to the occupancy of this prop

erty by plaintiffs.

4. Although plaintiffs were issued a certificate of occu

pancy they would still be subject to punishment by fine and

imprisonment under Sections 1604 and 1600 of the General

City Code of the defendant if they occupied the property

as a residence.

26

Appendix

5. Under the facts of this case, said Section 1604 of the

Zoning Chapter of the General City Code of Birmingham

prohibiting the use of the property in question by the plain

tiffs as a dwelling solely on account of the fact that they are

members of the negro race violates the provisions of the

Fourteenth Amendment to the Constitution of the United

States, and is void and of no effect.

Buchanan v. Warley, 254 U. S. 60 ;

Harmon v. Tyler, 273 U. S. 668;

Richmond v. Deans, 37 F. (2d) 712, aff. 281 U. S.

704.

6. The mere fact that the unconstitutional provision is

included in a general zoning ordinance does not render it

valid.

Clinard v. Winston-Salem (N. C.), 6 S. E. (2d)

867, 126 A. L. R, 634.

7. Under the evidence of this case, the mere existence of

the zoning provisions attacked deprives the plaintiffs of

the free use of their property and their right to sell to mem

bers of the negro race for occupancy and therefore presents

an actual and presently justiciable controversy.

Euclid v. Ambler Co., supra;

Buchanan v. Warley, supra.

8. Sections 1604 and 1605 of the Zoning Chapter of the

General City Code of the defendant are unconstitutional and

void as being in violation of the Fourteenth Amendment to

the Constitution of the United States.

9. This court takes judicial notice of the ordinances of

the City of Birmingham.

Title 7, Sec. 429 (1 ) Code of Alabama 1940 as

amended June 18, 1943.

27

Appendix

10. The value of the property of the plaintiffs has al

ready depreciated and will depreciate in the future, and

the plaintiffs will sustain irreparable injury unless they are

permitted to use and occupy their property and the de

fendant is enjoined from the enforcement of the provisions

of said Zoning Chapter of said Code which prohibit the use

and occupancy of plaintiffs’ property by persons of the

negro race. The plaintiffs do not have an adequate remedy

at law.

i

11. The plaintiffs are entitled to a permanent injunc

tion and declaratory judgment.

D ecree

It, is therefore, b y the court, Ordered, A djudged a n d D e

creed a s follows:

(1) That the First Defense of the defendant, which is,

in effect, a motion to dismiss on the ground that relief can

not be granted, be and the same is hereby overruled and

denied;

(2) That so much of Sections 1604 and 1605 of the Zon

ing Chapter of the General City Code of the defendant City

of Birmingham as zones or attempts to zone the property

of the plaintiffs for white occupancy or use only, or at

tempts to prohibit the use or occupancy of said property

by members of the negro race, is in contravention and vio

lation of the Constitution and laws of the United States and

is null and void;

(3) That the defendant, the City of Birmingham, its

officers, agents, servants and employees, be and they are

hereby enjoined and restrained from directly or indirectly

enforcing or attempting to enforce or attempting to do any

other act under color of Sections 1604 and 1605 of the Gen-

28

Appendix

eral City Code of the City of Birmingham in reference to

the right of the plaintiffs to nse or occupy the property

described as Lots 11 and 12 in Block 45 in the survey of

North Smithfield situated in the City of Birmingham as a

dwelling, or from interfering directly or indirectly with the

plaintiffs’ right to so use or occupy said property or per

mit other members of the negro race to use or occupy the

same; and, the defendant, its officers, agents, servants and

employees are further enjoined and restrained from refus

ing to the plaintiffs, or any other person of the negro race,

his or their application to occupy and reside on said prop

erty upon the ground of said applicant’s race;

(4) That the defendant is hereby authorized and di

rected to grant the application of the plaintiffs for a certifi

cate of occupancy to use or occupy the property described

in the bill of complaint as a dwelling;

(5) The costs are taxed against the defendant, the City

of Birmingham, for which execution may issue.

Done this the 4th day of August, 1947, at Birmingham,

Alabama.

Clarence M ijl l ix s

United States District Judge

Filed in Clerk’s Office

Northern District of Alabama

August 4, 1947

C h a s . B. C eow

Clerk, U. S. District Court.

A true copy

C h a s . B. Crow

Clerk, U. S. District Court

Northern District of Alabama

L awyers P ress, I n c ., 165 William St., N. Y. C.7 ; ’Phone: BEekman 3-2300