Motion For Leave to File Brief and Brief Amicus Curiae in Support of Petitioners

Public Court Documents

64 pages

Cite this item

-

Case Files, Milliken Hardbacks. Motion For Leave to File Brief and Brief Amicus Curiae in Support of Petitioners, 53cadb6f-54e9-ef11-a730-7c1e5247dfc0. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/37e40489-15e6-4fce-a9e6-cf0970ca5dd7/motion-for-leave-to-file-brief-and-brief-amicus-curiae-in-support-of-petitioners. Accessed February 25, 2026.

Copied!

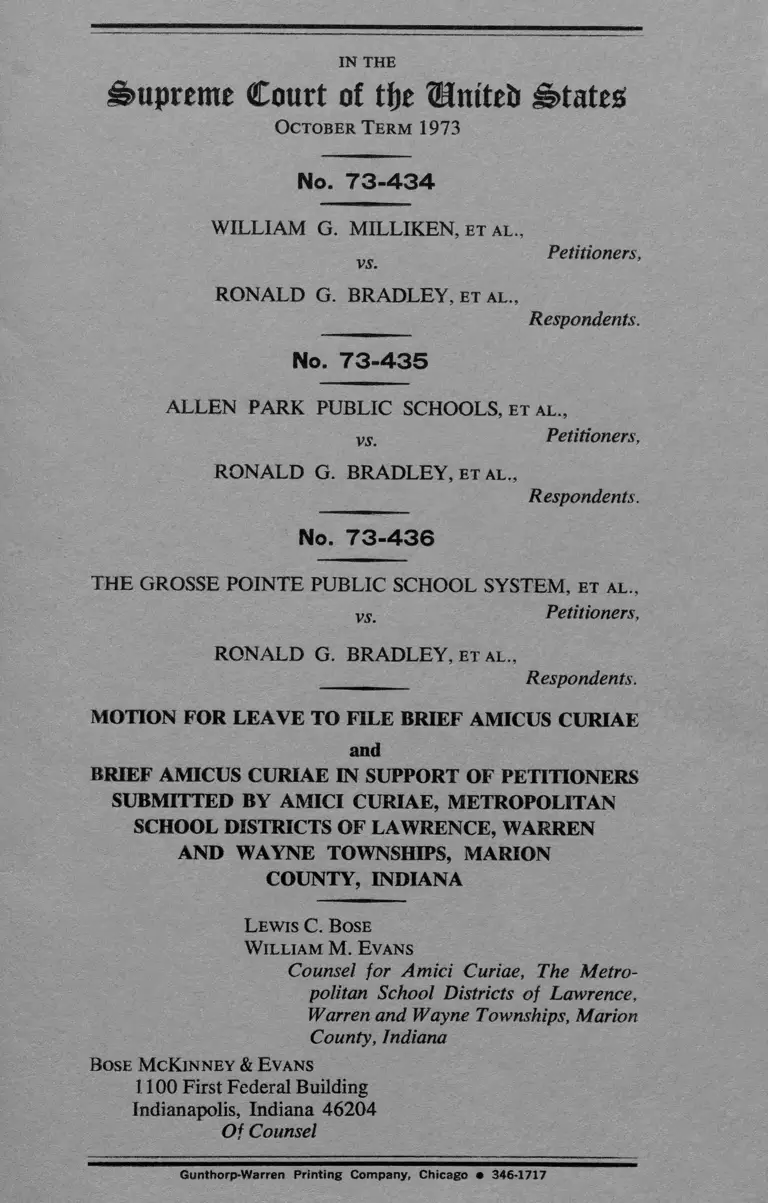

IN THE

Supreme Court of tfje UntteD States

October Term 1973

No. 7 3 -4 3 4

WILLIAM G. MILLIKEN, et al.,

vs Petitioners,

RONALD G. BRADLEY, et al.,

Respondents.

No. 7 3 -4 3 5

ALLEN PARK PUBLIC SCHOOLS, et al.,

vs. Petitioners,

RONALD G. BRADLEY, et al.,

Respondents.

No. 7 3 -4 3 6

THE GROSSE POINTE PUBLIC SCHOOL SYSTEM, et al.,

V5-, Petitioners,

RONALD G. BRADLEY, et al.,

__________ Respondents.

MOTION FOR LEAVE TO FILE BRIEF AMICUS CURIAE

and

BRIEF AMICUS CURIAE IN SUPPORT OF PETITIONERS

SUBMITTED BY AMICI CURIAE, METROPOLITAN

SCHOOL DISTRICTS OF LAWRENCE, WARREN

AND WAYNE TOWNSHIPS, MARION

COUNTY, INDIANA

L ewis C. Bose

William M. Evans

Counsel for Amici Curiae, The Metro

politan School Districts of Lawrence,

Warren and Wayne Townships, Marion

County, Indiana

Bose McKinney & Evans

1100 First Federal Building

Indianapolis, Indiana 46204

Of Counsel

Gunthorp-Warren Printing Company, Chicago • 346-1717

IN THE

Supreme Court of tije Mtuteb States

October T erm 1973

No. 73-434

WILLIAM G. MILLIKEN, et al.,

vs.

Petitioners,

RONALD G. BRADLEY, et al.,

Respondents.

No. 73-435

ALLEN PARK PUBLIC SCHOOLS, et al.,

Petitioners,

vs.

RONALD G. BRADLEY, et al.,

Respondents.

No. 73-436

THE GROSSE POINTE PUBLIC SCHOOL SYSTEM, et al.,

Petitioners,

vs.

RONALD G. BRADLEY, et al.,

Respondents.

MOTION FOR LEAVE TO FILE BRIEF AMICUS CURIAE

BY METROPOLITAN SCHOOL DISTRICTS OF

LAWRENCE, WARREN AND WAYNE TOWN

SHIPS, MARION COUNTY, INDIANA

2

The Metropolitan School District of Lawrence Township,

The Metropolitan School District of Warren Township, and

The Metropolitan School District of Wayne Township, all

located in Marion County, Indiana (referred to herein as

“Indiana School Districts” ) respectfully move the Court for

leave to file the attached “Brief Amicus Curiae” in this case

under Rule 42 of this Court.

Indiana School Districts requested and obtained consents to

file a brief amicus curiae from the attorneys for all the

Petitioners in this case, and from the Respondents, Michigan

Education Association and Professional Personnel of Van Dyke.

Indiana School Districts requested consents from the other

Respondents but received no reply.

The interest of the Indiana School Districts arises from the

following facts: They are parties defendant to consolidated

appeals now pending in the United States Court of Appeals for

the Seventh Circuit, United States of America and Buckley v.

Board of School Commissioners of the City of Indianapolis

(Cause Nos. 73-1968 through 73-1984). These appeals are

taken from an order of the United States District Court for

the Southern District of Indiana, ordering relief against school

districts (including Indiana School Districts) which are con

tiguous and non-contiguous to the Indianapolis school district

to remedy de jure segregation previously found to exist solely

within the Indianapolis school district.

The principal issue now on appeal in the expanded Indi

anapolis case is substantially similar to a principal issue raised in

Detroit case now before this Court: whether desegregation of a

central city in a metropolitan area may be accomplished by

consolidation, or other forms of metropolitan remedy, involving

surrounding contiguous and non-contiguous independent school

corporations, not themselves parties to illegal desegregation.

A summary of the position taken by the District Court in the

Indianapolis case is set out in an excerpt from its December

6, 1973 entry printed in the Appendix to the brief bound with

3

this motion at pages A1 through A10. Accordingly, a

decision in the cases now before this Court may in effect deter

mine the Indianapolis case now on appeal in the Circuit Court

of Appeals.

The Petitioners in the cases before this Court in their

Petitions for Certiorari have properly presented for review the

propriety of an interdistrict remedy. They have framed the

issue in terms of their status as independent municipal corporate

bodies separate and identifiable from Detroit, of the fact that

they did not participate in any discriminatory act towards the

Negro students of Detroit, and of the absence of a finding of

causal connection between the alleged discriminatory acts of

the Detroit Board or the State and the racial makeup of the

non-Detroit defendant school districts.

Indiana School Districts are of the opinion that resolution of

the case requires analysis of the demographic trends responsible

for the minority racial concentration in Detroit as in all major

metropolitan centers, and of the change in the scope and nature

of the Fourteenth Amendment obligation owed by Michigan

and virtually every other state to Negro students living in

metropolitan areas, upon affirmance of the decision of the

Sixth Circuit Court of Appeals. The proposed remedy would

place a burden on the Federal Courts to weigh the necessities

of desegregation or integration against very complex and edu

cationally sensitive problems incident to how7 school districts in

metropolitan areas are to be organized, reorganized and operated.

Indiana School Districts desire to present a brief amicus curiae

analyzing these problems and analyzing central city desegrega

tion from this standpoint.

Each of the Indiana School Districts is an independent muni

cipal corporation with the right to sue and be sued and is a

political subdivision established by the State of Indiana for the

4

purpose of administering schools within their respective

boundaries. The person signing this motion is the authorized

attorney for such Districts.

Respectfully submitted,

Lewis C. Bose

William M. Evans

Counsel for Amici Curiae, The Metro

politan School Districts of Lawrence,

Warren and Wayne Townships, Marion

County, Indiana

Bose McKinney & Evans

1100 First Federal Building

Indianapolis, Indiana 46204

Of Counsel

TABLE OF CONTENTS

PAGE

Table of A uthorities................................................................ i

Interest of Amici C u ria e ........................................................ 2

Summary of Argument ............................... 2

A rgum ent.................................................................................. 7

A. Population and Population C h an g e ...................... 7

B. Scope of the R em edy ............................................ 13

C. Reorganization: The Substantive F acto rs.............. 17

D. Affirmance Is Inconsistent with Prior Decisions

of This C o u r t .......................................................... 24

C onclusion................................................................................ 25

Appendix .................................................................................. A1

Table of A uthorities

Federal Cases

Bradley v. Milliken, 345 F. Supp. 914 (E. D. Mich.

1 9 7 2 ) .................................................................................. 15, 16

Bradley v. Milliken (6th Cir., Cause Nos. 72-1809-

72-1814), Slip Opinion, June 12, 1973 ........................ 13, 23

Brown v. Board of Education, 347 U. S. 483 (1954) . . . . 8

Brown v. Board of Education, 349 U. S. 301 (1955) . . . . 8

Calhoun v. Cook, 332 F. Supp. 804 (N. D. Ga. 1971),

affd. and rev’d. in part; 451 F. 2d 583 (5th Cir. 1972) 23

Goss v. Bd. of Ed. of Knoxville, 482 F. 2d 1044, (6th

Cir. 1973) ........................................................................... 23

Green v. County School Board, 391 U. S. 430 (1968) . . . 8

11

Haney v. Co. Bd. of Ed. of Seiver County, 410 F. 2d 920

(8th Cir. 1969) ................................................................. 24

Kelley v. Metro Bd. of Ed. of Nashville, Tenn., 463 F. 2d

732, 741 (6th Cir. 1972), cert. den. 409 U. S. 1001 . . 23

Keyes v. School District No. 1, Denver, Colo., ........ U. S.

........ , 41 U. S. L. W. 5002 (1 9 7 3 ) ..................................8, 13

Lee v. Macon Co. Bd. of Ed., 448 F. 2d 746 (5th Cir.

1 9 7 1 ) ..................................................................................... 24

San Antonio Independent Schl. Dist. v. Rodriguez, ........

U. S.......... , 41 U. S. L. W. 4407 (1 9 7 3 ) .......................15, 24

Spencer v. Kugler, 326 F. Supp. 1235 (D. N. J. 1971),

aff’d. 404 U. S. 1027 (1972) .......................................... 24

Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Board of Education, 402

U. S. 1 (1971) ..................................................... .............8 ,24

Wright v. Council of Emporia, 407 U. S. 451 (1972) . . . . 24

State Cases

Co. Dept, of Pub. Welfare v. Potthoff, 220 Ind. 574, 581,

44 N. E. 2d 494 (1942) .......................................... ........ 13

Southern Ry. Co. v. Harpe, 223 Ind. 124, 132, 58 N. E.

2d 346 (1944) ................................................................... 13

Woemer v. City of Indpls., 242 Ind. 253, 177 N. E. 2d

34 (1961) ............................................................................ 13

Government Publications

Bureau of the Census, General Demographic Trends for

Metropolitan Areas, 1960 to 1970, Rpt. PHC(2)-1,

page 3 (1971) ........................................................8, 9, 11, 12

Bureau of the Census, Social and Economic Characteristics

of the Population in Metropolitan and Non-Metropolitan

Areas: 1970 and 1960, Rpt. P23 No. 3 7 .(1 9 7 1 )___ 7, 8, 9

Ill

Bureau of the Census, Public School Systems in 1971-72

(herein School Systems 1971-2), Table 2 ....................13,17

Bureau of the Census, The Social and Economic Status of

the Black. Population in the United States, 1972, Rpt.

P-23 No. 26, p. .1 (1973) .............................................. 9

Bureau of the Census, Birth Expectations of American

Wives June 1973, Rpt. P-20, No. 254, Table 1 ........... 9

H. E. W., Dept, of Educational Statistics 1971 ............... 17

H. E. W. Education Directory 1972-73 ............................. 19

Statistical Abstract of the United States— 1972 ................A -ll

Articles

American Association of School Administrators, School

District Reorganization (1958), pp. 7 0 -7 1 .................... 15

Bundy Report— See article below: Mayor’s Advisory Panel

on Decentralization of the New York Schools, Recon

nection for Learning—A Community School System For

New York City, McGeorge Bundy, Chairman (Freder

ick A. Praeger, Publishers, 1969) ........................ 18, 19, 20

Drucker, The Age of Discontinuity (Harper & Row 1968) 10

Hickey, Optimum School District Size (Eric Clearinghouse

on Educational Administration, University of Oregon

1969), p. 2 5 ....................................................................... 18

Levin, Financing Schools in a Metropolitan Context in

Metropolitan School Organization: Basic Problems and

Patterns (McCutcheon Publishing Corporation 1973),

p. 39 ..................................................................................19, 22

Mayor’s Advisory Panel on Decentralization of the New

York Schools, Reconnection for Learning—A Com

munity School System For New York City, McGeorge

Bundy, Chairman (Frederick A. Praeger, Publishers,

1969) ........................................................................18 ,19 ,20

IV

Polley, “Decentralization Within Urban School Systems,”

in Education in Urban Society, (Dodd, Mead, and Co.,

1962) pp. 122-123, cited in the Bundy Report, p. 8. . . 20

Rebell, New York’s Decentralization Law: Two and a Half

Years Later, 2 Journal of Law and Education (1973)

(herein Rebell) ................................................................. 21

Taeuber, Negroes in Cities (Aldine Publishing Company

1965) (herein Taeuber) ................................................ 10,11

Wall Street Journal, September 7, 1972, p. 1, col. 1

“Who’s in Charge: Public-Employe Unions Press for

Policy Role; States and Cities Balk” ............................. 15

Zimvet, Decentralization and School Effectiveness— A Case

Study of the 1969 Decentralization Law in New York

City (Teachers College Press 1973) ............. . '............. 21

IN THE

Supreme Court of tfje Umteb

October T erm 1973

No. 73-434

WILLIAM G. MILLIKEN, et al.,

vs.

Petitioners,

RONALD G. BRADLEY, et al.,

Respondents.

No. 73-435

ALLEN PARK PUBLIC SCHOOLS, et al.,

Petitioners,

vs.

RONALD G. BRADLEY, et al.,

Respondents.

No. 73-436

THE GROSSE POINTE PUBLIC SCHOOL SYSTEM, et al.,

Petitioners,

vs.

RONALD G. BRADLEY, et al.,

Respondents.

BRIEF AND APPENDIX AMICUS CURIAE IN SUPPORT

OF PETITIONERS, SUBMITTED BY AMICI CURIAE,

METROPOLITAN SCHOOL DISTRICTS OF

LAWRENCE, WARREN AND WAYNE

TOWNSHIPS, MARION COUNTY,

INDIANA

2

This brief is filed pursuant to Rule 42 of the United States

Supreme Court. A motion for leave to file a brief amicus

curiae has been timely filed pursuant to Rule 42(3), and each

of the amici curiae is a political subdivision for educational

purposes of the State of Indiana.

INTEREST OF AMICI CURIAE

Amici Curiae are parties defendant to consolidated appeals

now pending in the United States Court of Appeals for the

Seventh Circuit, United States of America and Buckley v.

Board of School Commissioners of the City of Indianapolis,

(Cause Nos. 73-1968 through 73-1984). These appeals are

taken from an order of the United States District Court for

the Southern District of Indiana, ordering relief against school

districts (including Amici Curiae) which are contiguous and

non-contiguous to the Indianapolis school district, to remedy

de jure segregation previously found to exist solely within the

Indianapolis school district.

The principal issue now on appeal in the Indianapolis case

is substantially similar to a principal issue in the cases now be

fore this Court: Do state authorities have an obligation to

Negro and other minority ethnic group children to order a

reorganization of school governments and school management

in a metropolitan area to effect a maximum and stable racial

mix, where by reason of demographic trends common to the

entire United States, minority race children are now or may

become a majority in a central city district but are a minority

in a total metropolitan area.

SUMMARY OF THE ARGUMENT

Appellees now ask this Court for an expansion in kind and

degree of the obligations owed by state authorities under the

Fourteenth Amendment to Negro children and to other ethnic

3

groups, where they now are or may become a majority of the

population or enrollment in a central city school district, but

a minority in a total metropolitan area. Appellees assert that

the states have a Fourteenth Amendment obligation to re

organize local school governments and school management to

effect a maximum racial mix.

The decisions of this Court to date have dealt principally

with single school systems— do they retain vestiges of dualism,

have they maintained a dual school system in the absence of

statute, how shall they be desegregated? Even when all school

systems become unitary under these decisions, however, mixing

of blacks and whites to the degree demanded by Appellees

cannot be attained, given the structure of existing municipal

corporations.

Population growth, migration patterns and residential segre

gation have resulted in the central city of many urban areas

predominantly or heavily black, surrounded by urban areas

in the suburbs predominantly white. Where once America’s

population was predominantly rural it is now predominantly

urban. According to the 1970 U. S. Census figures, urban

areas throughout the country, including both central city and

suburban areas, contain 65% of the total, 64% of the white,

and 70.7% of the Negro population. Further, population has

had a natural increase from 131 million in 1940 to 203 million

in 1970. With limited availability of existing lands in central

cities, population has expanded substantially in the suburbs,

where there are now more people than in central cities. Thirty-

six percent of the total population of the United States (72.8

million people) live in suburbs, while 29% of the total popula

tion (58.6 million people) live in central cities. Negroes, how

ever, have migrated primarily to central cities where they con

stitute 21% of the population and where 58% of all the

country’s Negroes live. In the suburbs, by contrast, they con

tinue to migrate and increase but constitute only 5% of the

total suburban population. These concentrations are the product

4

of trends in migration and natural increase in population. The

trends vary from decade to decade, from region to region and

from city to city, influenced by changes in the birthrate, changes

in job opportunities, general economic conditions and avail

ability and condition of housing. The central cities experiencing

the greatest in-migration and having the highest concentra

tion of blacks are generally the Nation’s largest, such as New

York, Chicago, Los Angeles, San Francisco-Oakland and

Detroit. The continuing concentration has occurred, however,

to a greater or lesser degree in all others. These migrations

constitute some of the largest migrations in world history.

Further, substantial research shows that for all regions of

the country, all types of cities, large or small, central city or

suburban, substantial residential separation exists between Ne

groes and whites— a phenomenon that occurs regardless of the

character of laws and policies, and regardless of the extent of

other forms of separation or discrimination.

Since desegregation decisions applying to single school systems

neither touch nor counteract these trends, Appellees and judges

in the frustration of trying to attain a substantial and stable inte

gration of blacks and whites in school urge this Court to adopt

an expanded and deceptively simple version of the states’ Four

teenth Amendment obligation owed Negro children. If there are

insufficient whites within a single system so that the system is

identifiably black in comparison with its neighbors, the system

must be expanded, or expanded and then reorganized in smaller

areas, so that each resulting school district in a metropolitan area

has no greater percentage Negro than any other. After this

first step the expanded or reorganized districts will then be de

segregated within the command and guidelines of Brown, Green,

Swann and Keyes.1

1. Brown v. Board of Education, 347 U. S. 483 (1954)

(Brown I); Brown v. Board of Education, 349 U. S. 301 (1955)

(Brown II); Green v. County School Board, 391 U. S. 430 (1968);

Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Board of Education, 402 U. S. 1

(1971); Keyes v. School District No. 1, Denver, Colo., . . . . U. S.

-----, 41 U. S. L. W. 5002 (1973).

5

The suggested doctrine is, however, highly complex and in

volves the Court in fundamental questions of local and state

educational and governmental policy— decisions which this

Court has never considered appropriate for judicial action. The

impracticability and undesirability of implicating the judiciary in

balancing integrative necessities against the educational necessi

ties of alternate local educational organization— the types, size,

organization and powers of governmental entities which the

states create to carry on education— can best be demonstrated

by the vastness of the area and the scope and detail of the

problems involved.

As to the size of the problem, 4,896 of the country’s 16,859

school systems are in metropolitan areas. They enroll 32 million

of the Nation’s 48 million school children.

Further, each reorganization involves detailed problems in

fluencing the kind of education that can or will be delivered,

problems with highly divergent solutions. The following are

representative: the size of the area to be desegregated in terms

of numbers and proportions of Negro and white students; the

size and proportion of Negro and white pupils in each unit;

whether the area will be administered as a unit or broken down

into smaller units; whether any unit will have sub-districts and

the kinds and amount of authority to be given to each sub-district

over such matters as curriculum, budget, personnel, union nego

tiations; how many members will be on the governing bodies of

school boards or sub-boards; how the board members are to be

selected— by election or appointment; if by appointment by

whom the appointment is to be made; what relationship, if any,

is to be retained between local school and civil government; how

much tax base be assigned to each proposed unit of government;

what shall be done with existing union contracts; will such con

tracts be negotiated in the future on a local, metropolitan or

statewide basis; where, will, or may, teachers be transferred or

assigned in the area; will curriculum or other educational stand

ards or tax practices be uniform throughout the area; if so, by

6

whom will they be set. Extreme size itself is currently one of

the most criticized aspects of school administration.

Finally, the duty to reorganize school districts would apparent

ly be an on-going duty since its necessity is now urged on the

basis of the identifiably black nature of central city school stu

dent bodies and the constitutional authority of the states to re

organize local units of government, Surely racial patterns are

not now fixed for all time but will continue to change.

Neither the prior pronouncements of this Court relating to

constitutionally required equality of treatment nor the in

ternal logic of these pronouncements, suggest or require that the

separate school systems be unidentifiable by the race of their

students. The pronouncement of such a doctrine would consti

tute a greater change in the body politic than the change from

“separate but equal” to “separate is inherently unequal” and

freedom of choice” following Brovin 1 and Brown II, or from

the latter to the “affirmative duty” of Green, Swann and Keyes.

Amici urge that thus redefining a duty to involve the Federal

Courts in weighing a necessity of integration against subjective

determinations of educational management, throughout the

country, with unpredictable and possibly counter-productive re

sults, is unwarranted, and that the decision of the Sixth Circuit

Court of Appeals should be reversed.

7

ARGUMENT.

A. Population and Population Change.

The theory of Appellees’ case has implications extending far

beyond the Detroit area with its several million people. It is

based on changes in the concentrations and racial makeup of

population and must be evaluated in the light of nationwide

population trends. For census purposes, the country has been

broken down into metropolitan areas inside central cities, met

ropolitan areas outside central cities generally called suburbs,

and non-metropolitan areas.

The most significant facts about America’s population are

its continued growth, that it is highly and increasingly urban,

and that its increased growth is predominantly in the suburbs.

As of the 1970 census, the distribution of population between

the major types of population areas was as follows:2

Number

Area (in millions) Percent

Metropolitan Areas:

Inside Central Cities 58,635 29.0

Suburbs 72,883 36.0

Non-metropolitan Areas 71,015 35.1

Total 202,534 100.0

This represented an increase of 28 million persons in the ten-

year period beginning in 1960. Of this increase, 20 million

were in metropolitan areas; and only 4 million in non-metro

politan areas. Of the 20 million ten-year increase in the met

ropolitan areas, 16.8 million were in suburban areas. Even

2. Bureau of the Census, Social and Economic Characteristics

of the Population in Metropolitan and Non-Metropolitan Areas:

1970 and 1960, Rpt. P23 No. 37 (1971) (herein Pop. Rpt. 23

No. 37), Table A.

8

though extensive, these changes represent a slowing of the rate

of increase for both central city and suburban population in

crease, which were twice as high in the preceding 10 years

beginning in 1950.3

These trends are different for whites and blacks. Whites in

the ten-year period between 1960 and 1970 decreased in num

ber and percent in central cities, increased slightly in non

metropolitan areas, and increased substantially in suburban

areas. Blacks, on the other hand, decreased in non-metropoli

tan areas, increased substantially in suburban areas, but in

creased in an even greater amount both in numbers and percent

in central cities,4 as shown by the following chart:5

1970 I960 Change 1960-1970

Percent Percent

Race and Distri- Distri-

Residence___________Number* bution Number* bution Number* Percent

WHITE

Metropolitan:

Inside Central Cities 45,088 25.4 47,638 30.0 —2,550 —5.4

Suburban 68,539 38.6 51,793 32.6 16,746 32.3

Non-metropolitan 63,802 36.0 59,267 37.3 4,535 7.7

Total—United States 177,429 100.0 158,698 100.0 18,731 11.8

NEGRO

Metropolitan:

Inside Central Cities 12,587 55.2 9,480 51.5 3,107 32.8

Suburban 3,536 15.5 2,430 13.2 1,106 45.5

Non-metropolitan 6,685 29.3 6,481 35.2 204 3.1

Total—United States 22,807 100.0 18,391 100.0 4,416 24.0

* In Millions

Within metropolitan areas of every region, including the

south, whites are found in the largest numbers in the suburbs

while blacks are concentrated in central cities; and in each

3. Bureau of the Census, General Demographic Trends for

Metropolitan Areas, 1960 to 1970, Rpt. PHC(2)-1, page 3 (1971)

(herein Demo. Rpt. PHC(2)-1).

4. Id. at pp. 4-6.

5. Pop. Rpt. 23 No. 37, supra n. 2, Table A-

9

region of the country, blacks now comprise a higher percentage

of the central city population than they did a decade ago.6

A significant factor in attempting a nationwide policy on

restructuring local government, if it be done, is some under

standing of the underlying causes of population change. One

of these is the birthrate. For whites, the birthrate has fallen

in the last decade and continues to fall moderately. For Negroes

the birthrate has fallen later but since 1967 more precipitately,

but is still above the level of white births.7 This has been re

flected in falling elementary school enrollments which in future

years will mean reductions in both elementary and upper grade

enrollments.8

An additional factor is the relative ages of white and black

women of childbearing age. For the country as a whole a

greater percentage of the Negro population than of the white

is of childbearing age. This, however, varies from region to

region. The north central region has a relatively lower white

age group than the northeast region, while the white popula

tion of the south and west are more youthful than either.9

Further, aside from the factors of natural increase, popula

tion distribution depends on the factors influencing in-migration

to one area and out-migration from another. Migration de

pends among other things on the relative lack of employment

opportunities in the place people live compared with the greater

6. Id. at p. 2; Demo. Rpt. PHC(2)-1 at pp. 4-5; Bureau of the

Census, The Social and Economic Status of the Black Population

in the United States, 1972, Rpt. P-23 No. 26, p. 1 (1973) (herein

Bl. Pop. Rpt. P-23, No. 26). A chart further evidence this fact

assembled from data in Statistical Abstract of the United States—

1972 is set out in the Appendix to this brief (herein the Br. App.)

at p. A ll.

7. Bl. Pop. Rpt. P-23 No. 26, supra n. 6, Table 59 reproduced

in Br. App. p. A12; Bureau of the Census, Birth Expectations of

American Wives June 1973, Rpt. P-20, No. 254, Table 1, repro

duced in part in Br. App. at p. A13.

8. Bl. Pop. Rpt., supra n. 6, Table 46, reproduced in Br, App.

at p. A14.

9. Demo. Rpt. PHC(2)-1, supra n. 3, pp. 7, 9, 10, 12.

10

opportunities in the areas into which they move, and the avail

ability of housing in other areas, either public or private. The

change for employment reasons is illustrated by the northward

movement of blacks from cotton producing jobs during World

War I due to the destruction of the cotton crop by the boll

weevil and the improvement in farm machinery, coupled with

the increase in wartime employment opportunities in the north.

Further illustrative, is the slowing of this movement during the

depression of the thirties, and its increase again during and

after World War II.10 The availability of housing, in turn, is

affected by major economic factors. Negroes did not move

from the inner part of the central city during World War II

because new housing was non-existent. The flow of Negroes to

the outer areas of central cities and to the suburbs, and of

the whites to the suburbs, was due in large part to the destruc

tion of central city housing by public works or private develop

ment, its deterioration in older areas, and to the vast expansion

of housing in the suburbs commencing in the fifties. The con

tinued migration of both whites and blacks to particular met

ropolitan areas in the sixties and beyond is a product of

continuing better job opportunities.11

In recent years, migration has not been characterized entirely

by migrations from rural to metropolitan, but also by migrations

from one metropolitan area to another, migrations which “flow

in complex and interlocking channels.”12

The only certainties in the area of demographics are the

variations within a general theme, the multiple factors which

govern change, and the unpredictability of percentages, ratios

and numbers of population and school enrollment within any

particular area.

10. Drucker, The Age of Discontinuity (Harper & Row 1968),

p. 227. “No city in history has ever been able to absorb an influx

of such magnitude as the American cities have had to absorb since

the end of World War II.”

11. Taeuber, Negroes in Cities (Aldine Publishing Company

1965) (herein Taeuber) pp. 12-3, 125, 152-3, 162-165.

12. Taeuber, at pp. 127-8.

11

The variations are at least as significant as the overall pattern

For example, in the decade of the sixties: in the northeast, popu

lation growth was due to natural increase, the substantial white

out-migration being balanced in part by in-migration of other

races, there being an increase in white non-metropolitan popu

lation ;lrt in the north central region, there was heavier out

migration of whites from non-metropolitan areas, with roughly

balancing out-migration of whites from, and Negroes into,

metropolitan areas;13 14 in the south there was, by contrast, heavy

in-migration of whites to metropolitan areas, lighter in-migration

of other races, moderate out-migration of whites and heavy out

migration of Negroes from non-metropolitan areas;15 in the west,

net in-migration to metropolitan areas was highest in percent in

the Nation, consisting of 2.4 million whites and 650,000 of

other races, with California the greatest attractor of migrants

in the Nation, gaining 2,000,000 by in-migration.16

Cities reveal the same variation. For example, blacks ex

panded in all suburban areas but without, however, an over

all percentage increase. Virtually all the increase resulted

from in-migration in the suburbs and not from any natural

increase. The suburban areas of Washington, D. C. and St.

Louis had large Negro percentage gains; Detroit and Pittsburgh

virtually none, and Baltimore suburbs experienced a Negro per

centage loss.17

Central cities which showed the greatest percentage loss in

white population were among the 12 largest in the country, but

even here there was variation. New York, Chicago and Detroit

alone accounted for more than half of the loss in numbers.

Washington, D. C., St. Louis, Detroit and Cleveland had the

highest rates of loss, with Chicago and New York showing rel-

13. Demo. Rpt. PHC(2)-1, supra n. 3, p. 7.

14. Id at p. 9.

15. Id. at p. 10.

16. Id. at p. 11.

17. Id. at p. 14.

12

atively moderate rates of loss, and Los Angeles experiencing a

white gain in population. Cities between 2 million and 500,000

had a small aggregate gain in numbers of whites, but about one-

half of these cities lost white population while the other half

gained, with great variations between them.18 The same varia

tion can be applied to Negro gains in numbers as well as white

losses. The figures can be further broken down to show whether

the gains or losses were occasioned by net in-migration, net

out-migration, or natural population increase.

Finally, one researcher has found that residential separation

between blacks and whites is a condition existing in all cities in

all regions of the country regardless of the character of local

laws and policies, and regardless of the extent of other forms of

segregation and discrimination.19

There are no reliable studies suggesting that central city

school segregation was a causal factor in these vast demographic

changes or that the present trends are consistent throughout

the country or can be accurate predictors of what will occur

in the future in any particular metropolitan area or city.

If demographic changes in school enrollments make a case

for judically supervised school reorganization, the change will

be national in scope and can reasonably be expected to affect

many of the 4,896 school corporations in metropolitan areas

18. Id. at p. 13.

19. Taeuber, supra n. 10, pp. 35-6.

“No further analysis is necessary to reach some broad

generalizations concerning racial segregation: In the urban

United States, there is a very high degree of segregation of the

residences of whites and Negroes. This is true for cities in all

regions of the country and for all types of cities—large and

small, industrial and commercial, metropolitan and suburban.

It is true whether there are hundreds of thousands of Negro

residents, or only a few thousand. Residential segregation pre

vails regardless of the relative economic status of the white and

Negro residents. It occurs regardless of the character of local

laws and policies, and regardless of the extent of other forms

of segregation or discrimination.”

13

which educate 32 million of the Nation’s 48 million school

children.20

B. Scope of the Remedy.

Appelles’ justification for a judical order to the State of

Michigan to reorganize its school corporations is based on the

segregation in the Detroit schools, its predominant (68.6% )

Negro enrollment coupled with the predominantly white enroll

ment of surrounding school corporations,21 the technical nature

of local school officials as “state officials” charged with local re

sponsibilities, and the constitutional right of the State to create,

dissolve, regulate and grant powers to, local school corporations.

This chain of logic disregards the fact that while Michigan, in

common with other states, has plenary power over the entities

by which education is carried out, it has chosen to carry out edu

cation through local independent municipal corporations pri

marily responsible to a local constituency.22

The question is not whether the State has the right to control

these matters, but whether the Fourteenth Amendment requires

a judicial supervision over the character of the entities by which

educational matters be carried out for the purpose of achieving

a greater mix of Negroes and whites and a balancing of integra

tive necessities against the multitudinous educational considera

tions involved in a reorganization of school corporations. An

20. Bureau of the Census, Public School Systems in 1971-72

(herein School Systems 1971-2), Table 2.

21. Bradley v. Milliken (6th Cir., Cause Nos. 72-1809-72-

1814) Slip Opinion, June 12, 1973, pp. 53, 63-4.

22. Parenthetically most states also have plenary authority over

all local governmental subdivisions. In Indiana this is true for

counties (Co. Dept, of Pub. Welfare v. Potthoff, 220 Ind. 574, 581,

44 N. E. 2d 494 (1942) and for civil cities and towns (Woerner v.

City of Ind pis., 242 Ind. 253, 266, 177 N. E. 2d 34 (1961)),

which may be abolished, consolidated or combined or eliminated by

statute, and which have only those powers delegated by statute

(Southern Ry. Co. v. Harpe, 223 Ind. 124, 132, 58 N. E. 2d 346

(1944)).

14

answer requires some understanding of the broad range of edu

cational matters now determined locally.

The framework for the performance of educational services

throughout the country is described by this Court in San Antonio

Independent School District v. Rodriquez in substantial detail,

but also in general terms as follows:23

“Although policy-decision making and supervision in cer

tain areas are reserved to the State, the day-to-day authority

over the ‘management and control’ of all public elementary

schools is squarely placed on the local school boards.”

This is typically and particularly true throughout the country

in broad areas of educational policy, including among other

things, curriculum and school programs, hiring, firing and pro

motion of personnel, fixing the terms of employment, pupil

assignments, school construction and budget. With respect to

curriculum, while a multiple choice of textbooks and minimum

graduation requirements are generally certified by the state, local

school districts have tremendous latitude. They determine the

subjects taught, the methods by which they are taught, the

amount of time spent per day in different study areas, pupil

assignment, grade structure of particular schools, the use of

supplemental material, summer school programs, the type and

extent of extracurricular activities, whether to provide schools

for specialized instruction, whether to adopt such innovations as

undifferentiated grade schools, “hands on” vocational programs,

and learning disability programs, and where, how and whether,

to build facilities for those activities.

With respect to personnel, while the states enforce minimum

certification requirements, the great bulk of personnel decisions

— who is hired, where they are to be assigned, internal adminis

tration, orgainization of departments, the conditions of employ

ment, the right of promotion and transfer— are controlled local

ly, particularly in the larger districts, the latter matters are

governed by highly sophisticated union contracts negotiated be-

23............U. S........... , 41 U. S. L. W. 4422, n. 108.

15

tween local districts and unions, where the scope of negotiations

becomes a confrontation between board and union over general

school policy.24 With respect to pupil policies, typically, a local

school district will control where and to what schools pupils are

assigned, whether they will be transferred, the prerequisites to

participation in given programs and the control and discipline of

students. Budget, another local function, determines how much

of the available funds a district will expend in what areas. As

has been frequently noted, control of fiscal policy is control of

educational policy.25

The extent to which Appellees would inject the judiciary into

this local process is evidenced by the District Courts by the

“Ruling on Desegregation Area and Order for Development of

a Plan of Desegregation” in this case.26 While this order was

vacated by the Sixth Circuit order pending state legislative

response, it was not reversed; and the scope of this order in

dicates the necessary scope of the response. It is to be

measured by the interplay of only two factors, “maximum

feasible desegregation” and the “elimination of racially identifi

able schools”.27 With respect to the area of desegregation to

24. See, Wall Street Journal, September 7, 1972, p. 1, col. 1

“Who’s in Charge: Public-Employe Unions Press for Policy Role;

States and Cities Balk”:

“The UFT’s president, Albert Sb anker, freely concedes that

some of the demands had policy implications. But, he insists,

‘what we’re primarily interested in is improving the teachers’

working conditions.’ It just so happens, he adds, that ‘there is

hardly anything which cannot simultaneously be viewed as a

working condition and a matter of educational policy.’

The issue of class size is one of Mr. Shanker’s favorite

examples. ‘You can approach it from the point of view of

what’s best for the children or as a question of allocating

resources,’ he says. ‘But, obviously, handling a lot of kids is

more difficult than handling just a few. And in that way, it’s

most certainly a working condition.’ ”

25. American Association of School Administrators, School

District Reorganization (1958), pp. 70-71.

26. 345 F. Supp. 914 (E. D. Mich. 1972).

27. Id. at p. 925, n. 9.

16

which the order applied, the Court had before it the following

proposals:28

Proposal Number of

Districts

Number of

Pupils

% Black

Total Metropolitan

Area 86 1,000,000 20%

Detroit Board 69 850,000 25%

CCBE 62 770,000 25.4%

Plaintiffs 54 780,000 25.3%

State 36 555,000 36%

The Court chose a modified form of Plaintiff’s proposal.

With respect to the organization of local governmental entities

necessary to effect the order, the following parts are significant:29

J. Pending further orders of the court, existing school

district and regional boundaries and school governance

arrangements will be maintained and continued, except

to the extent necessary to effect pupil and faculty desegrega

tion as set forth herein; provided, however, that existing

administrative, financial, contractual, property and govern

ance arrangements shall be examined, and recommenda

tions for their temporary and permanent retention or

modification shall be made, in light of the need to operate

an effectively desegregated system of schools (345 F.

Supp. at p. 919.)

̂ * * * *

70. The plans submitted by the State Board, the

Detroit Board, and the intervening defendants Magdowski,

et al., discuss generally possible governance, finance, and

administrative arrangements which may be appropriate for

operation of an interim or final plan of desegregation.

Without parsing in detail the interesting, and sometimes

sensible, concepts introduced by each plan, it is sufficient to

note that each contemplates overlaying some broad educa-

28. Id. / 'Tj

29. The District Court Order in the Indianapolis case was com

parable in scope, although ameliorated in detail. See Br. App.,

pages Al through A10.

17

tional authority over the area, creating or using some

regional arrangement (with continued use or eventual re

drawing of existing districts), and considerable input at the

individual school level. The court has made no decision in

this regard and will consider the matter at a subsequent

hearing. (345 F. Supp. at p. 933.)

C. Reorganization: The Substantive Factors.

A local school district’s organization is a major determinate

of whether it can deliver good education. The most crucial

aspect is its size: too small, it lacks the pupils and resources

for a broad range of offerings and services; too large, it be

comes unresponsive to its constituents, inflexible, inefficient and

unable to innovate on a broad scale. Since the early 1940’s,

extremely small size has been increasingly corrected by con

solidation.30 No good remedy has been found for bigness (as

will be shown below); but there has been no tendency to aggre

gate schools further into extremely large units. Distribution of

schools in the United States by enrollment as of 1969 was as

follows:31

School Districts with pupil

Number Percent

of Total

Enrollments of 25,000 & over 180 1.001%

10,000 to 24,000 538 2.992

5,000 to 9,999 1,096 6.095

2,500 to 4,999 2,026 11.268

300 to 2,499 7,911 43.998

under 300 6,229 34.644

The classic examination of large school system failure is the

study conducted by the Mayor’s Advisory Panel on Decentraliza

tion of New York Schools, better known as the “Bundy Report”.

This report chronicled and studied the continuing decline in

30. School Systems 1971-72, supra n. 20, pp. 1-2.

31. H. E. W., Dept, of Educational Statistics 1971.

18

student performance and increasing cost of the New York

City system. It pinpointed the major cause as too large a size.32

No school system is free of shortcomings, but in New

York the malaise of parents is heightened by their in

creasing inability to obtain redress or response to their

concerns. Teachers and administrators, too, are caught in

a system that has grown so complex and stiff as to over

whelm its human and social purpose.

Whether the reaction is quiet frustration or vocal pro

test, the result throughout the city is disillusionment with

an institution that should be offering hope and promise.

No parent, no teacher, no school administrator, no citizen,

no business or industry should rest easy while this erosion

continues.

The causes of the decline are as diverse and complex as

the school system itself and the city that created it. But

one critical fact is that the bulk and complexity of the

system have gravely weakened the ability to act of all

concerned— teachers, parents, supervisors, the Board of

Education, and local school boards.

The system had become one in which many interest groups

could assert a negative and self-serving power but in which

none could effectively innovate.33

Neglect of this principle (i.e., the instrumental value of

power as opposed to its value as a final goal) in our

judgment, is responsible for much of what is wrong in

the New York City Schools today. We find that the school

system is heavily encumbered with constraints and limita

tions which are the result of efforts by one group to assert

a negative and self-serving power against someone else.

Historically these efforts have had ample justification, each

32. Mayors Advisory Panel on Decentralization of the New

York Schools, Reconnection for Learning—A Community School

System for New York City, McGeorge Bundy, Chairman (Fred

erick A. Praeger, Publishers, 1969) (herein the “Bundy Report)

pp. 5-6.

33. Reprinted in Hickey, Optimum School District Size (Eric

Clearinghouse on Educational Administration, University of Oregon

1969), p. 25.

19

in its time. To fend off the spoils system, to protect

teachers from autocratic superiors, to ensure professional

standards, or for dozens of other reasons, interest groups

have naturally fought for protective rules. But as they

operate today these constraints bid fair to strangle the

system in its own checks and balances, so that New

Yorkers will find themselves, in the next decade as in the

last, paying more and more for less and less effective

public education (p. 1).

Size, itself, has been recognized in many studies as responsible

for many of the failures of large city schools, such studies

making it increasingly clear that good educational decisions

are made at a level that is close to the individual child.34

At the same time, it is peculiar that, just as the dis

advantages of large school districts are being recognized,

the metropolitan approach would increase the size of the

overall administrative unit. The cumbersome and highly

bureaucratized behavior of the large-city school districts is

responsible for many of the failures of the city schools.

Increasingly, it appears that good educational decisions

are made at a level that is close to the individual child

(see, for example, Fantini [1970], pp. 40-75). Despite

this recognition, the movement to metropolitan school dis

tricts would centralize further the level of decision making

and buttress that centralization with an even greater op

portunity for bureaucratic mindlessness.

There have been many studies on the optimum size of a

school district. Generally recommended optimum sizes vary

with the purpose for which the size is picked. Studies do not,

however, suggest a school district size even approaching Detroit’s

size.35

34. Henry M. Levin, Financing Schools in a Metropolitan Con

text in Metropolitan School Organization: Basic Problems and

Patterns (McCutcheon Publishing Corporation 1973), p. 39.

35. Detroit is the sixth largest school district in the United

States with an enrollment of 266,193 in the 1971-1972 school year.

H. E. W. Education Directory 1972-73, p. 255. For a table sum

marizing optimum for varying purposes, see Br. App. A15.

2 0

The remedy proposed by the Bundy Report was based on

the following premise:36

The concept of local control of education is at the heart

of the American public school system. Laymen deter

mine the goals of public education and the policies calcu

lated to achieve them.

The report recommended decentralizing the system into

component units with substantial and real control over educa

tional policy. It proposed local community school districts of

from 12 to 40 thousand pupils with some policy established

on a city-wide basis but with each district primarily governed

by community school boards. These would establish procedures

and channels for the closest possible consultation with parents,

community residents and teachers, preserving all existing tenure

rights of teachers but thereafter awarding tenure selection to

the community district.37

This type of decentralization is of a different character from

decentralization of administrative functions where all ultimate

control is retained by central authorities. The results of the

latter have been characterized as follows:38

When authority is decentralized, the person granted local

power remains responsible to the same group of officials

that delegated the authority. . . . Because local officials

are responsible to higher authority, rather than to those

they serve, their clients have no direct means of influencing

policy or action; even more important, perhaps, the official

loses the freedom of action which true responsibility would

confer on him. . . . What now exists . . . in most large

cities is authority without responsibility.

The decentralization recommended by the Bundy Report has

been a failure since it did not reckon with the unwillingness

36. Bundy Report, p. 6.

37. Id. at pp. XIII and XIV.

38. John W. Polley, “Decentralization Within Urban School

Systems,” in Education in Urban Society (Dodd, Mead, and Co.,

1962), pp. 122-123, cited in the Bundy Report, p. 8.

21

of those who had power within the system— teachers, administra

tors and central board— to relinquish it. The range of failure,

from the compromise enabling legislation through its subsequent

implementation, has been well chronicled.39 Curriculum reform

could not be effected because of central board control of

policies and since central board budgetary restraints prevented

local boards from hiring curriculum specialists.40 Budget sub

missions by local boards were for informational purposes only,

and local funds were allocated by fairly rigid formulas.41 With

respect to personnel, the relatively large grants of power were

frustrated by the power retained in the Board of Examiners to

appoint, assign and discharge teachers. Teachers retained the

right to transfer from one district in the system to another and

were unresponsive to the needs of the constituency they served.42

Finally, the process of collective bargaining remained with the

central board. Local boards had three representatives who could

meet with the negotiating committee but who were not part of

the “management team”.43 The quantitative results in student

performance continued downward after decentralization, as it

had before.44

39. Rebell, New York’s Decentralization Law: Two and a

Half Years Later, 2 Journal of Law and Education (1973) (herein

Rebell); Zimvet, Decentralization and School Effectiveness—A Case

Study of the 1969 Decentralization Law in New York City

(Teachers College Press 1973) (herein Zimvet).

40. Rebell, pp. 7-12; Zimvet, p. 5.

41. Rebell, pp. 13-14.

42. Zimvet, pp. 5-6, 127-128.

“Much of the conflict between the professional staff and

the community can be traced to these two sets of criteria. In

terms of what a teacher should be, the professional staff and

the unions representing them insist that he must pass certain

tests, possess particular credentials, and perform his assigned

duties in accordance with accepted procedures and practices.

Community groups, on the other hand, especially those con

cerned with the appointment of more black and Puerto Rican

teachers and supervisors, insist that traditional credentials are

not as important as is the ability of the teacher or supervisor to

relate to children, to parents, and to the community.”

43. Rebell, pp. 21-30.

44. Zimvet, p. 147.

22

The “metropolitan solution” has been termed an educational

myth attributable to the desire for simple answers to complex

questions and one which fails to make the distinction between

educational problems which exist in a metropolitan area as

contrasted with problems which can only be solved by a met

ropolitan solution.45

Even if a metropolitan solution is necessary for purposes of

achieving maximum integration, however, the only structural

remedy to the educational problem of size-—decentralization—

will by definition conflict with integration in many situations.

The concentration of Negroes and whites in different areas is

the heart of the problem, and this occurs by the decentraliza

tion of the present local educational governments.

In any case, and even if experts are found who revere large

school size, this is the caulderon of educational policy into

which Appellees would thrust the judiciary in decreeing maxi

mum integration by interdistrict remedy.

In addition to the problem of establishing a new framework of

educational government, Appellees’ position raises the equally

difficult problem of how each reorganized unit shall be gov

erned. With hundreds of thousands of people in very large

areas, elections have proved unsatisfactory. They are expensive,

often lack effective supporting political organization, and are

subject to manipulation by narrowly based interest groups. If

the governing body is to be picked by appointment, the appoint

ing authority must be chosen. What civil political officer or

officers will be chosen, answerable to whom. Appointment re

moves the board member one further step from the people he

serves— a crucial problem in a large district whose boundaries

are not, and in a reorganization will not be, coterminous with

any other political entity.

Other problems, while less fundamental, will prove equally

troublesome. What will be done with the collective bargaining

contract of the largest unit? Will this contract be imposed

45. Metro. Schl. Org., supra n. 35, pp. 35, 41-2.

23

over the entire area on the various units and sub-units? May

teachers be transferred from one area to another? Do the

residents of the area through their boards have power to hire,

fire, transfer and promote? Are the teachers responsive to the

constituents of that district— a factor more important than

formal educational qualifications? Who controls finance?

Necessarily the judiciary, under Appellees’ theory, must in

the last analysis determine a myriad of educational problems in

the reorganized districts which affect the day-to-day operation

of the system. Further, since the reorganization process even

without desegregation problems lasts over several school years,

and since desegregation cases historically are marked by long

court sojourns with annual petitions for additional relief as

conditions or doctrine change, judicial intervention will be both

pervasive and long.46 Additionally, the implication of the Sixth

Circuit Court opinion would logically require further judicial

reorganization occurring with demographic change. Its deci

sion is buttressed on the racial identifiability of Detroit “as a

black school system” and a Detroit school district predominantly

black surrounded by a ring of suburbs and school systems pre

dominantly white and historical boundary lines which are con

sidered artificial and must be disregarded.47 As applied to the

country as a whole, this condition will occur in many other

areas, and will reoccur in some areas once an area is desegre

gated given the varying pattern of demographic change.

46. For a poignant history of one desegregation suit, see Cal

houn v. Cook, 332 F. Supp. 804, 805-6 (N. D. Ga. 1971), aff’d.

and rev’d. in part; 451 F. 2d 583 (5th Cir. 1972). In view of the

subjective educational and governmental judgments required under

the doctrine here urged by Appellees consistency of lower court

decision would be even less expected than it is in practice under the

present relatively clear single district doctrines. Compare, Kelley v.

Metro Bd. of Ed. of Nashville, Tenn., 463 F. 2d 732, 741 (6th Cir.

1972), cert. den. 409 U. S. 1001, with Goss v. Bd. of Ed. of Knox

ville, 482 F. 2d 1044, 1046-7 (6th Cir. 1973).

47. See, n. 21 supra.

24

D. Affirmance Is Inconsistent with Prior Decision of This

Court.

The internal logic of prior decisions of this Court does not

require or permit the redefinition of the constitutional duty urged

by the Appellees or reached by the Sixth Circuit. There is no

showing that the acts of school authorities in Detroit created the

concentration of black population and black students in Detroit.

Rather, this concentration was a major demographic change

occurring to a greater or lesser extent throughout the country as

a whole. This Court has previously held that the constitution

does not require a particular racial balance in a given school or

stability in racial balance in a school or school district.48 Further,

the Detroit area suburban schools are not part of the Detroit

school system in which segregation was found by the District

Court, but are separate identifiable and unrelated school sys

tems.49 This is not a case where the Detroit area districts are

being created with the effect of hindering a desegregation

order.50 Finally, Appellees have attacked, as has been shown

above, the basic governmental framework and methods of edu

cational management which Michigan has chosen for furnishing

education to its children. This framework and these methods

are matters in which courts lack expertise and familiarity, where

educators cannot agree on the solutions to the many problems

and where it would be difficult to imagine a constitutional re

quirement having a greater impact on the federal system.51

48. Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Board of Education, 402

U. S. 1, 24, 31-2; Spencer v. Kugler, 326 F. Supp. 1235 (D. N. J.

1971), aff’d. 404 U. S. 1027 (1972).

49. Keyes v. School District No. 1, Denver, Colo., . . . . U. S.

. . . ., 41 U. S. L. W. 5002, 5006, 5009 (1973).

50. Wright v. Council of Emporia, 407 U. S. 451 (1972).

Neither is this a case such as Haney v. Co. Bd. of Ed. of Seiver

County, 410 F. 2d 920 (8th Cir. 1969), where small all negro

districts were set up as an integral part of a dual system, or Lee v.

Macon Co. Bd. of Ed., 448 F. 2d 746 (5th Cir. 1971), where the

State had acted to prevent desegregation within a single district.

51. San Antonio Independent Schl. Dist. v. Rodriguez, . . . .

U. S......... , 41 U. S. L. W. 4407, 4419-20 (1973).

25

CONCLUSION

As a matter of educational policy, it may be sound in specific

instances for states to reorganize their school districts or to

cause the transfer of students across district lines for the purpose

of creating greater mixing of the races in settings which promise

to further the education of all children. An absolute constitu

tional requirement, however, that states must reorganize any dis

trict in a metropolitan area where its student body is more

heavily black than its neighbors to counteract existing and future

demographic trends would thrust the federal judiciary into

balancing a necessity of integration against and ultimately de

termining the most sensitive areas of school management. Such

a requirement is unwarranted. Amici urge that the decision of

the Sixth Circuit Court of Appeals in this case be reversed.

Respectfully submitted,

Lewis C. Bose,

William M. Evans,

1100 First Federal Building,

Indianapolis, Indiana 46204

Bose, McKinney & Evans

Of Counsel.

A ppendix

TABLE OF CONTENTS TO APPENDIX

PAGE

Excerpts from Supplemental Memorandum of Decision,

December 6, 1973, United States of America, et al. v.

The Board of School Commissioners of Indianapolis,

et al. (S D Ind. No. IP-68-C-225) ...........................A1-A10

Growth of Non-White Population in Major Central Cities,

1960-1970 ........................................................................... A l l

Bureau of Census— Table on birth expectations for report

ing wives, 18 to 39 years old, 1967 and 1972 ................A12

Bureau of Census— Births to date per 1,000 wives to 18 to

39 years old, 1967 to 1973 .................................................A13

Bureau of Census— School Enrollment, 3 to 34 years old

by level, 1967 and 1972 .....................................................A14

Chart of optimum school district size recommendations . . A15

A1

APPENDIX

U nited States D istrict Court

Southern District of Indiana

Indianapolis Division

United States of A merican, et a l . ,"

Plaintiffs,

vs.

r*Cause No. IP-68-C-225

The Board of School Commission

ers of Indianapolis, et al

Defendants. __

EXCERPTS FROM

SUPPLEMENTAL MEMORANDUM OF DECISION

(December 6, 1973)

I. Introduction

Heretofore, on August 18, 1971, the Court filed herein its

Memorandum of Decision, incorporating its findings of fact and

conclusions of law, and making certain interim orders, with

respect to the issues presented by the complaint of the original

plantiff, United States of America, and the answer of the

original defendants, The Board of School Commissioners of the

City of Indianapolis, the individual members of such Board, and

the Board’s appointed Superintendent of schools. Such decision,

which will be referred to hereafter as “Indianapolis I ” is re

ported in 332 F. Supp. 655, aff’d 474 F. 2d 81 (7 Cir. 1973),

cert. den. 37 L. Ed. 2d 1041 (1973).

Thereafter, on July 20, 1973, the Court filed herein a second

Memorandum of Decision, incorporating its findings of fact and

conclusions of law, and making certain interim orders, with re

spect to certain issues presented by the complaint of the original

A2

and added plaintiffs, Donny Brurell Buckley, et al, and the

answers of the original and added defendants. Such decision

will be referred to hereafter as “Indianapolis II,” is reported

i n ........ F. Supp............ , 37 Ind. Dec. 524, and is now’ on appeal

to the Court of Appeals for the Seventh Circuit, Nos. 73-1968

to 73-1984, inch

The key decision made in Indianapolis I was that the India

napolis public school system (hereafter “IPS”) was being oper

ated by the original defendants, and had been operated by their

predecessors in office, as a system practicing de jure segregation

of students of the Negro race. It was therefore held that the

Negro students were being denied the equal protection of the

laws, as guaranteed by the Fourteenth Amendment. Brown v.

Board of Education, 347 U. S. 483 (1954). Certain interim

measures tending to prevent further segregation were ordered,

pending consideration of the questions to be presented and later

decided in Indianapolis II, it being understood that the law re

quired the defendants to take affirmative action to desegregate

IPS Green v. Country School Board, 391 U. S. 430 (1968).

The key decisions made in Indianapolis II were that (1) as a

practical matter, desegregation promising a reasonable degree of

permanence could not be accomplished within the present boun

daries of IPS, and (2) added defendant officials of the State of

Indiana, their predecessors in office, the added defendant The

Indiana State Board of Education, and the State itself have, by

various acts and omissions, promoted segregation and inhibited

desegregation within IPS, so that the State, as the agency ulti-

matedy charged under Indiana law with the operation of the

public schools, has an affirmative duty to desegregate IPS.

The Court also held in Indianapolis II that IPS could be effec

tively desegregated either by combining its territory with that

of all or part of the territory served by certain added defendant

school corporations, into a metropolitan system or systems, and

then reassigning pupils within the expanded system or systems

thus created, or by transferring Negro students from IPS to

A3

added defendant school corporations, either on a one-way or an

exchange basis. It further held that the State, through its Gen

eral Assembly, should be first afforded the opportunity to select

its own plan, but that if it failed to do so within a reasonable

time, the Court would have the power and the duty to promul

gate its own plan, and place it in effect. Bradley, et al, v. Milli-

ken, et a l , ........ F. 2 d .......... (6 Cir. 1973). See Baker v. Carr,

369 U. S. 186 (1962); Reynolds v. Sims, 377 U. S. 533 (1964).

By way of affirmative relief pending action by the General

Assembly, the Court ordered IPS to effect pupil reassignments

for the 1973-74 school year sufficient to bring the number of

Negro pupils in each of its elementary schools to approximately

15%, which has been accomplished. The Court also directed

IPS to transfer to certain added defendant school corporations,

and for such corporations to receive and enroll, a number of

Negro students equal to 5% of the 1972-73 enrollment of each

transferee school, with certain exceptions. This order was, on

August 8, 1973, stayed by the Court until the 1973-74 school

year by an order made in open court but not previously reduced

to writing.

At this time, certain matters have been presented to the

Court, both formally and informally, which require further rul

ings in the premises. Such rulings are now made, as hereafter

set out, as supplementary to or, in some instances, in lieu of

rulings heretofore entered in Indianapolis II, as heretofore

modified.

* * * He $

IV. Guidelines of this Court— General

It is, of course, recognized by the Court that it cannot

issue a positive order to the General Assembly to enact specific

legislation. It is for such reason that the Court has suggested

several different methods by which the General Assembly

could approach the problem of effectively desegregating IPS,

A4

and it does not imply that there may not be other equally

effective methods which may occur to that body.

Within the context of what has been suggested as possible

alternatives, however, the Court offers further observations, as

follows:

(1) With respect to the concept of one metropolitan school

district, embracing the area designated in Figure 1, attached

to the Court’s opinion in Indianapolis II, it is apparent that

some advantages would be obtained from such a system. To

name a few, a uniform tax base would be provided for the

education of the more than 200,000 pupils, in the combined

system, and economy in operation could be achieved through

central purchasing and reduction of administrative overhead.

Complete desegregation would be simplified. On the other

hand, it may be that such a system would be too large in terms

of difficulty of administration and remoteness of the central

office from school patrons.

(2) With respect to the concept of creating various new

metropolitan districts— for example, six or eight to replace the

present twenty-four pictured on Figure 1, it is apparent that

some of the advantages above noted would be reduced, and

some of the disadvantages improved. Another alternate of

course, would be to create one metropolitan system for taxing

purposes, which in turn would be subdivided into several semi-

autonomous local districts. So long as IPS and the local districts

are each effectively desegregated, the method used would be

constitutionally immaterial.

(3) With respect to the concept of permitting the present

school corporations shown on said Figure 1 to remain as is,

insofar as geography and control is concerned, such a solution

would of course preserve local autonomy, and this Court would

have no reason to disapprove such a solution, so long as each such

corporation is required to participate in the desegregation of

IPS. Put in other terms, local autonomy for such corporations,

is, under the law of Indiana, a privilege—-not a right—-all

A5

as discussed in detail in Indianapolis II. The consideration

for permitting the various corporations to continue their separate

existences might therefore be stated to be their participation in

a meaningful plan to desegregate IPS. Some of the pertinent

facts which the General Assembly may wish to consider in

this regard are set out in the next two sections hereof.

V. Transfer of Pupils

When speaking of the transfer of pupils, the first logical

question is as to the numbers involved. In this connection, the

focus must be on the elementary schools within IPS which

were not affected by the interim plan adopted by the Court for

the present school year, and which have an enrollment of

Negro pupils exceeding 80%. There are nineteen such schools,

fourteen of which have Negro enrollments in excess of 97%.

Two additional schools have enrollments exceeding 60%, and

should also be considered. The total enrollment of black

students in these 21 schools, excluding kindergarten and special

education students, is approximately 11,500.

The General Assembly might order the exchange of all

or a substantial part of these 11,500 students with students

from the suburban school corporations. For purposes of illustra

tion, if it were determined to desegregate such schools on the

basis of approximately 85% white— 15% black, then about

9,775 black children would need to be transferred to suburban

schools, and about the same number of non-black children

would need to be transferred to IPS.

There is case law to the effect that transfers of students

must be made on an approximately equal basis insofar as the

races are concerned, unless there is good reason why this

should not be done. In such cases it has been held that to

impose the “burden” of being transported wholly or largely

upon students of one race is yet another from of racial dis

crimination and in violation of the Fourteenth Amendment

rights of the group transported. United States v. Texas Educa-

A6

tion Agency, 467 F. 2d 848 (5 Cir. 1972); Lee v. Macon

County Board of Education, 448 F. 2d 746 (5 Cir. 1971);

Haney v. County Board of Education of Sevier County, 429

F. 2d 364 (8 Cir. 1970). Such cases, if followed, would

seem to mandate so-called “two-way” busing, absent compelling

reasons to the contrary.

The Supreme Court has not specifically addressed itself to

this question. However, it is worthy of note that in McDaniel

v. Barresi, 402 U. S. 39 (1971), that Court approved a de

segregation plan adopted by the Clarke County (Ga.) Board

of Education which reassigned pupils in five heavily Negro

“ ‘pockets’ ” to other attendance zones, busing many of them,

without any corresponding busing of whites. Other “one-way”

busing plans have likewise been approved, depending on the

factual setting. Hart v. County School Board, 459 F. 2d 981

(4 Cir. 1972); Norwalk Core v. Norwalk Board of Education,

423 F. 2d 121 (2 Cir. 1970). Indeed, the Fourth Circuit has

flatly held that a pattern of assigning Negro students to formerly

all-white schools, without requiring similar travel on the part

of whites, does not violate the equal protection clause of the

Fourteenth Amendment. Allen v. Asheville City Board of

Education, 434 F. 2d 902 (4 Cir. 1970). Moreover, analysis

of the cases cited in the preceding paragraph indicates that

they have been decided on their particular facts, even though

some of the language is in terms of absolute requirements.

The Court does not find it necessary to attempt to resolve

this question in terms of constitutional absolutes, nor could it