Rogers v Loether Writ of Certiorari

Public Court Documents

October 1, 1972

68 pages

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Rogers v Loether Writ of Certiorari, 1972. 1507e42a-c39a-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/38092c01-0ce8-41b7-9ce9-98fd371713c1/rogers-v-loether-writ-of-certiorari. Accessed February 24, 2026.

Copied!

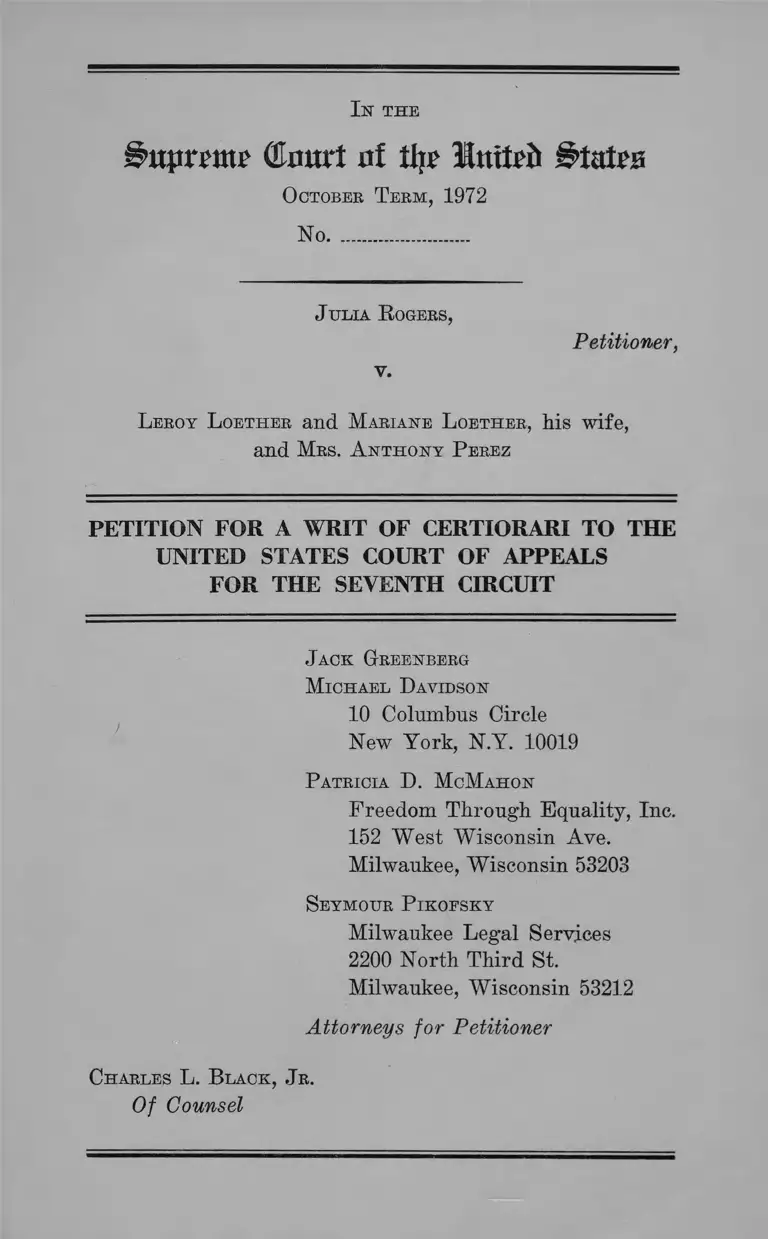

In the

i>upnw OInurt ai tip Itttteii i>tatpa

O ctober T erm , 1972

No.........................

J u lia R ogers,

Y.

Petitioner,

L eroy L oether and M ariane L oether, his w ife,

and M rs. A n th o n y P erez

PETITION FOR A WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE SEVENTH CIRCUIT

J ack Greenberg

M ichael D avidson

10 Columbus Circle

New York, N.Y. 10019

P atricia D. M cM ahon

Freedom Through Equality, Inc.

152 West Wisconsin Ave.

Milwaukee, Wisconsin 53203

S eymour P ikofsky

Milwaukee Legal Services

2200 North Third St.

Milwaukee, Wisconsin 53212

Attorneys for Petitioner

Charles L. B lack , J r .

Of Counsel

I N D E X

Citations to Opinions Below ..................... .............. ....... 1

Jurisdiction .............................................................. 2

Question Presented ........................................................... 2

Constitutional and Statutory Provisions Involved ..... 2

Statement of the Case ...................................... 4

Reasons for Granting the Writ ...................................... 8

I. Certiorari Should Be Granted to Determine an

Issue Fundamental to the Successful Adminis

tration of an Important Act of Congress ........... 8

II. The Statute Provides That Issues of Fact in Ac

tions for Injunctive Relief and Damages Be Tried

by Judges Without Juries ................................ 11

III. The Seventh Amendment Does Not Prevent Con

gress from Enforcing the Fair Housing Law in

Federal Courts Without the Intervention of

Juries ......................................................................... 15

a. Actions to Enforce Title VIII Are Not in the

Nature of Suits at Common L a w ...................... 15

b. A Court in a Title VIII Action Acts as a

Court of Equity With Power to Afford Com

plete R elief.... ....................................................... 18

c. There Is No Right to a Jury Trial in Respect

to the Limited Punitive Damages Remedy

Available Under the Statute ............................ 21

PAGE

11

IY. The Decision of the Seventh Circuit Conflicts in

Principle With Decisions in Other Circuits on

the Right to Juries in Related Civil Rights Ac

tions ............................................................................. 24

C onclusion .......................................................... 26

A ppendix—

District Court’s Opinion and Order Denying Demand

for Jury T r ia l......................................................... ....... la

District Court’s Oral Findings of Fact and Conclu

sions of Law .............................................................. ----- 7a

Judgment of District Court.................................... -....... - 12a

Opinion of Court of Appeals .................................-....... 13a

Judgment of Court of Appeals ...................................... 34a

T able of A uthorities

Cases:

Argesinger v. Hamlin, 407 TT.S. 2 5 ................................... 22

Baltimore & C. Line v. Redman, 295 U.S. 654 ............... 15

Beacon Theatres, Inc. v. Westover, 359 IJ.S. 500 ....7,19, 20

Bowe v. Colgate-Palmolive Company, 416 F.2d 711

(7th Cir. 1969) ....................... 25

Brown v. State Realty, 304 F.Supp. 1236 (N.D. Ga.

1969) .............................................. 15

Cathcart v. Robinson, 30 U.S. (5 Pet.) 264 ................... 19

Cauley v. Smith, 347 F.Supp. 114 (E.D. Va. 1972) ....... 10

PAGE

PAGE

Cheatwood v. South Central Bell Telephone and Tele

graph Co., 303 F.Supp. 754 (M.D. Ala, 1969) ........... 12

Civil Bights Cases, 109 U.S. 3 .......................................... 17

Clark v. Wooster, 119 U.S. 322 ........................................ 19

Culpepper v. Reynolds Metals Co., 296 F.Supp. 1232

(N.D. Ga, 1968), rev’d on other grounds, 421 F.2d

888 (5th Cir. 1970) ...................... ........ .......................12,17

Dairy Queen, Inc. v. Wood, 369 U.S. 469 .................7,19, 20

Dred Scott v. Sanford, 60 U.S. (19 How.) 393 ............... 17

Filer & Stowell Co. v. Diamond Iron Works, 270 F.

489 (7th Cir. 1921) .............................. ........................... 22

Harkless v. Sweeny Independent School District, 427

F.2d 319 (5th Cir. 1970), cert, denied, 400 U.S. 991 24

Jesus College v. Bloom, 26 Eng. Rep. 953 (Ch. 1745).... 18

Johnson v. Georgia Highway Express, 417 F.2d 1122

(5th Cir. 1969) ............................................................. 12, 24

Jones v. Mayer, 392 U.S. 409 ........................................15, 20

Kastner v. Brackett, 326 F.Supp. 1151 (D. Nev. 1971) 10

Katchen v. Landy, 382 U.S. 323 ........................ 14,18,19, 20

Kennedy v. Lakso Co., 414 F.2d 1249 (3rd Cir. 1969) 22

King v. Inhabitants of Thames Ditton, 99 Eng. Rep.

891 (1785)......................................................................... 16

Lowry v. Whitaker Cable Corporation, 348 F.Supp,

202 (W.D. Mo. 1972) ..................................................... 12

McFerren v. County Board of Education, 455 F.2d 199

(6th Cir. 1972) ................................................................. 24

Marr v. Rife, Civ. No. 70-218 (S.D. Ohio, Aug. 31,

1972) ................................................................................ 10

IV

Mitchell v. De Mario Jewelry, 361 U.S. 288 ................... 20

Moss v. The Lane Company, No. 72-1628 (4th Cir.,

Jan. 11, 1973) ...................................................... .......... 24

Newman v. Piggie Park Enterprises, Inc., 390 TJ.S. 400

(1968) ............................................................. ................. 21

N.L.R.B. v. Jones &Laughlin Steel Corp., 301 U.S. 1 ....6,16,

17,19

PAGE

Ochoa v. American Oil Co., 338 F.Supp. 914 (S.D.Tex.

1972) ................................................................................. 24

Railway Mail Ass’n v. Corsi, 326 U.S. 8 8 ...................... 15

Robinson v. Lorillard Corp., 444 F.2d 791 (4th Cir.

1971) ................................................................................. 24

Root v. Railway Co., 105 U.S. 189 ....... ........................... 19

Ross v. Bernhard, 396 U.S. 531 ...................................... 19, 20

Seymour v. McCormick, 57 U.S. (16 How.) 480 ........... 22

Simler v. Conner, 372 U.S. 221........................ 20

Slaughter-House Cases, 83 U.S. (16 Wall.) 3 6 ............. 17

Smith v. Hampton Training School, 360 F.2d 577 (4th

Cir. 1966) ......................................................................... 24

Somerset v. Stewart, 98 Eng. Rep. 499 (K.B. 1772) .... 16

Swofford v. B & W Inc., 336 F.2d 406 (5th Cir. 1964),

cert, denied, 379 U.S. 962 ................................ 22

Tilgham v. Proctor, 125 U.S. 136 .................................... 22

Trafficante v. Metropolitan Life Insurance Company,

41 U.S.L.W. 4071 (U.S. Dec. 7, 1972) ........................ 8

United States v. Hunter, 459 F.2d 205 (4th Cir. 1972) 15

United States v. Mintzes, 304 F.Supp. 1305 (D. Md.

1969) 15

V

United States v. Real Estate Development Corpora

PAGE

tion, 347 F.Supp. 776 (N.D. Miss. 1972) ..................... 15

United States v. Reddoch, No. 72-1326 (5th. Cir., Oct. 4,

1972) ................................................................................. 10

Williams v. Travenol Laboratories, 344 F.Supp. 163

(N.D. Miss. 1972) ............. 12

Statutes:

42 U.S.C. § 1983 ................................................................... 24

Title II, Civil Rights Act of 1964....................................... 21

Title VII, Civil Rights Act of 1964 ............................ 5,12, 24

Title VIII, Civil Rights Act of 1968............................. passim

§801 ........................ ........... ....................................... ..... 8

§804 ............................................ 2

§812 ....................................................... 3,4, 5, 6,10,11, 20

§813 ...:'........................................................................... 10

§814 .................................................... 14

Equal Employment Opportunity Act of 1972, Pub. L.

92-261 .............................................................................. 24

Other Authorities:

A dministrative Office of th e U nited S tates Courts,

1972 A n n ual R eport of the D ir e c t o r ................. .........9,16

A dministrative Office of the U nited S tates Courts,

1972 J uror U tilization in U nited S tates Courts .... 9

VI

I J. E liot , T he D ebates in t h e S everal S tate Con

ventions on the A doption op th e F ederal Consti

PAGE

tution (2d ed.) ............................................................. 16

A. L ester & Gr. B in d m an , R ace and L aw (1972) ....16,17,18

110 Cong. Rec. 7255 (1964) ............................................ 12

112 Cong. Rec. 9390 (1966) ............................................ 12

112 Cong. Rec. 9396 (1966) ............................................. 18

112 Cong. Rec. 9397 (1966) .......................................... 12,18

112 Cong. Rec. 18739 (1966) ........................................ 18

114 Cong. Rec. 2270 (1968) .......................................... 18

114 Cong. Rec. 4570-73 (1968) ...................................... 18

Hearings on H.R. 14754 Before Subcommittee No. 5 of

the House Comm, on the Judiciary, 89th Cong., 2nd

Sess., ser. 16 (1966) ..................................................... 13,18

Hearings on S.3296 Before the Subcommittee on Con

stitutional Rights of the Senate Committee on the

Judiciary, 89th Cong., 2nd Sess. (1966) ..................... 13

In the

Supreme (tart nt % Inttrii Stairs

O ctober T erm , 1972

No.........................

J u lia R ogers,

v.

Petitioner,

L eroy L oether and M ariane L oether, his w ife ,

and M rs. A n th o n y P erez

PETITION FOR A WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE SEVENTH CIRCUIT

Petitioner prays that a writ of certiorari issue to review

the judgment of the United States Court of Appeals for

the Seventh Circuit entered in this case on September 29,

1972.

Citations to Opinions Below

1. Opinion of district court denying demand for jury

trial, May 19, 1970, reported 312 P.Supp. 1008

(la-6a).

2. District court’s unreported findings of fact and con

clusions of law, October 27, 1970 (7a-lla).

3. Opinion of Court of Appeals, reported 467 F.2d

1110 (13a-33a).

2

Jurisdiction

The court of appeals entered judgment on September

29, 1972 (34a). On December 14, 1972, Mr. Justice Rehn-

quist extended the time for filing this petition to January

27, 1973. Jurisdiction of this Court is invoked under 28

U.S.C. § 1254(1).

Question Presented

Whether either Title VIII of the Civil Rights Act of

1968, 42 U.S.C. §§ 3601-19, or the Seventh Amendment to

the United States Constitution, require a trial by jury on

the demand of a landlord in an action by a black apartment

applicant for injunctive relief and punitive damages to

redress a racially discriminatory refusal to rent?

Constitutional and Statutory Provisions Involved

1. United States Constitution, Amendment VII provides:

In suits at common law, where the value in contro

versy shall exceed twenty dollars, the right of trial

by jury shall be preserved, and no fact tried by a

jury, shall be otherwise reexamined in any Court of

the United States, than according to rules of the com

mon law.

2. Section 804(a) of the Civil Rights Act of 1968, 42

U.S.C. § 3604(a) provides:

As made applicable by section 803 and except as

exempted by sections 803(b) and 807, it shall be un

lawful—

(a) To refuse to sell or rent after the making of a

bona fide offer, or to refuse to negotiate for the sale

3

or rental of, or otherwise make unavailable or deny,

a dwelling to any person because of race, color, re

ligion, or national origin.

3. Section 812 of the Civil Eights Act of 1968, 42 U.S.C.

§ 3612, provides:

(a) The rights granted by sections 803, 804, 805,

and 806 may be enforced by civil actions in appropriate

United States district courts without regard to the

amount in controversy and in appropriate State or

local courts of general jurisdiction. A civil action

shall be commenced within one hundred and eighty

days after the alleged discriminatory housing practice

occurred: Provided, however, That the court shall

continue such civil case brought pursuant to this sec

tion or section 810(d) from time to time before bring

ing it to trial if the court believes that the conciliation

efforts of the Secretary or a State or local agency are

likely to result in satisfactory settlement of the dis

criminatory housing practice complained of in the com

plaint made to the Secretary or to the local or State

agency and which practice forms the basis for the

action in court: And provided, however, That any sale,

encumbrance, or rental consummated prior to the issu

ance of any court order issued under the authority of

this Act, and involving a bona fide purchaser, en

cumbrancer, or tenant without actual notice of the

existence of the filing of a complaint or civil action

under the provisions of this Act shall not be affected.

(b) Upon application by the plaintiff and in such

circumstances as the court may deem just, a court of

the United States in which a civil action under this

section has been brought may appoint an attorney for

the plaintiff and may authorize the commencement of

4

a civil action upon proper showing without the pay

ment of fees, costs, or security. A court of a State

or subdivision thereof may do likewise to the extent

not inconsistent with the law or procedures of the State

or subdivision.

(c) The court may grant as relief, as it deems ap

propriate, any permanent or temporary injunction,

temporary restraining order, or other order, and may

award to the plaintiff actual damages and not more

than $1,000 punitive damages, together with court costs

and reasonable attorney fees in the case of a prevail

ing plaintiff: Provided, That the said plaintiff in

the opinion of the court is not financially able to as

sume said attorney’s fees.

Statement of the Case

On November 7, 1969, petitioner Julia Rogers complained

in United States District Court for the Eastern District

of Wisconsin that Leroy and Mary Loether, white owners

of a house in Milwaukee,1 violated Section 804 of the Civil

Rights Act of 1968 by refusing to rent an apartment to

Mrs. Rogers because she is black. She requested injunctive

relief and $1000 punitive damages, but neither alleged nor

sought actual damages. Jurisdiction of the district court

was based on Section 812 of the Act. After an evidentiary

hearing on November 20, 1969, the court preliminarily en

joined rental of the apartment pending final determination

of the action. Defendants answered and demanded a jury

trial of issues of fact.

1 The complaint also named Mary Loether’s cousin, Mrs. Anthony

Perez, who resided in the house and was authorized to show the

vacant apartment to applicants.

5

By the time the district court considered and denied the

jury demand, two developments intervened. Following the

preliminary hearing petitioner found a place to live and

disclaimed need for injunctive relief. Also, during pre

trial proceedings petitioner indicated an interest in com

pensatory as well as punitive damages, and the court viewed

her claim as including both. The court ruled that Section

812 of the Civil Bights Act of 1968 did not expressly re

quire jury trials and appeared “to treat the actual damages

issue as one for the trial judge rather than a jury” (la ).

It drew support for this construction from rulings that

similar language in Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of

1964, 42 U.S.C. § 2000e-5(g), does not require jury deter

mination of back pay awards in employment discrimination

cases. On the constitutional issue, the district court held

“this cause of action is a statutory one invoking the equity

powers of the court, by which the court may award com

pensatory and punitive money damag’es as an integral part

of the final decree so that complete relief may be had.

The action is not one in the nature of a suit at common

law, and therefore there is no right to trial by jury on the

issue of money damages in the case (2a).

The court entered a standard pre-trial order requiring

petitioner to file “an itemized statement of special dam

ages,” and, on July 6, 1970, a second order requiring peti

tioner to “ set forth the actual damages claimed and the

evidentiary facts in support of such damages. Petitionei

filed no statement itemizing actual damages, and at the

October 1970 trial the court sustained defendants’ objec

tions to testimony concerning actual damages.2 As the

court framed the damage issue at trial, “ it’s really nar

rowed down to punitive damages.” 3 At the conclusion of

2 Trial transcript, October 26, 1970, pp. 17-18.

3 Id. at 5, 7.

6

the trial,4 * the court found that the Loethers effectively

rented the apartment to Mrs. Rogers through intermedi

aries, but, in violation of the Civil Rights Act of 1968,

revoked the rental upon learning that Mrs. Rogers is black

(7a-lla). The court granted $250 punitive damages, but

denied actual damages, attorney’s fees and costs (12a).

The Seventh Circuit reversed, holding that defendants’

jury trial demand should have been granted.6 Although

the court posed the question—“whether appellant was en

titled to a jury trial in an action for compensatory and

punitive damages brought under § 812 of the Civil Rights

Act of 1968” (13a)—it did not predicate its decision on

the abandonment of petitioner’s request for injunctive relief

and held that the right to a jury trial may be tested by the

relief requested in petitioner’s complaint (25a). Never

theless, the court ignored the fact that the complaint al

leged no actual damages. Neither did it consider that the

district court confined the damage issue at trial to, and

rendered judgment for, punitive damages only. In short,

the court o f appeals decided the broadest jury question

possible under Title V III of the Civil Rights Act of 1968.

The court’s opinion centers on its conclusion that an

action to enforce Title VIII of the Civil Rights Act of

1968 is “ in the nature of a suit at common law” (21a).

Three reasons are offered. First, the decision-making tri

bunal is a court. In this way the court distinguished

N.L.R.B. v. Jones dc Laughlin Steel Corp., 301 IT.S. 1, 48-

4 Trial proceedings were expedited by incorporating evidence at

the preliminary hearing into the trial record.

6 The court of appeals rejected defendants’ other contentions.

The court ruled that the district court’s finding of discrimination

was not clearly erroneous (14a). It also concluded that the Act

authorizes an award of punitive damages even in the absence of

actual damages (15a).

7

49, limiting its principle to administrative agencies. Sec

ond, money damages are sought. The court read Beacon

Theatres, Inc. v. Westover, 359 U.S. 500, and Dairy Queen,

Inc. v. Wood, 369 U.S. 469, to mandate “that once any claim

for money damages is made, the legal issue—whether de

fendant breached a duty owed plaintiff for which defend

ant is liable in damages—must be tried to a jury whether

or not there exists an equitable claim to which the damage

claim might once have been considered ‘incidental’ ” (27 a-

28a, emphasis added). Third, the court concluded that

“the nature of the substantive right asserted, although not

specifically recognized at common law, is analogous to

common law rights” (22a). The court drew its principal

analogy to the obligation of English innkeepers to rent

available lodgings to travelers.

The court’s extended constitutional analysis culminates

in statutory interpretation. It finds the district court’s

statutory analysis “persuasive but not compelling” and

concludes that the statute “implies, without expressly stat

ing, that a jury’s participation is appropriate” when dam

ages are sought (31a). In the end the court views as

“ controlling” a canon of construction requiring the inter

pretation of statutes to avoid “grave doubts” of uncon

stitutionality and concludes that Title VIII of the Civil

Eights Act of 1968 itself requires jury trials when damages

are claimed (33a).

8

REASONS FOR GRANTING THE WRIT

I.

Certiorari Should Be Granted to Determine an Issue

Fundamental to the Successful Administration of an

Important Act of Congress.

Section 801 of the Civil Rights Act of 1968 declares it is

national policy to provide “fair housing throughout the

United States.” 42 U.S.C. § 3601. The statute assigns

certain administrative responsibilities to the Secretary of

Housing and Urban Development and limited powers to

the Attorney General of the United States. Against “ the

enormity of the task of assuring fair housing . . . the main

generating force must be private suits in which . . . the

complainants act not only on their own behalf but also

‘as private attorney general in vindicating a policy that

Congress considered to be of the highest priority.’ ”

Trafficante v. Metropolitan Life Insurance Company, 41

U.S.L.W. 4071, 4073 (U.S. Dec. 7, 1972). Unfortunately,

the decision of the court of appeals diminishes the effective

ness of private enforcement actions and jeopardizes the

ability of the Act to contribute much beyond the enuncia

tion of national policy.

Critical decisions made in the early life of a statute

may forever affect its usefulness. In the case of Title VIII

the mode of trial may be the most important such decision.

The mode selected, either as a result of statutory or con

stitutional interpretation, will determine the cost, efficiency,

and credibility of the mechanism entrusted to enforce the

important rights declared by Congress. These considera

tions may not bear on this Court’s ultimate judgment on

the requirements of the Seventh Amendment, but should

9

weigh, heavily in favor of giving plenary consideration to

the statutory and constitutional issues in this case.

Jury trials will add cost and delay to the administration

of the statute. The median interval in federal courts from

complaint to trial is 10 months in non-jury cases but 14

months in jury cases.6 To a person needing a home, that

additional delay in achieving a basic right may be intol

erable. Jury trials are also longer and more costly than

court trials. Although the statute authorizes the award

of reasonable attorney’s fees, many of the volunteer lawyers

on whom plaintiffs still depend may be discouraged by

the increased complexity and cost of extended jury trials.7

We are also concerned with prejudice. Admittedly, if the

statute or Constitution require jury trials, the possibility

of jury prejudice would be an unavoidable concomitant.

Still, this consideration supports certiorari. The bitter

legislative struggle to adopt a national fair housing law

reflects divisions in our society not instantaneously resolved

by the Act’s passage. We might wish that jurors would be

persuaded to lay aside any question of the correctness of

the law they enforce, but it frankly seems illusory to think

that unanimity of judgment can be achieved with enough

frequency to make a reality of the law. To the extent that

means exist to screen prejudice in the voir dire of jurors,

the process will be costly to plaintiffs and burdensome to

the courts. Furthermore, even the possibility of jury

6 A dministrative Office of the United States Courts, 1972

A nnual R eport of the Director 11-74.

7 Jury trials are also costly to the United States, A dministrative

Office of the United States Courts, 1972 Juror Utilization in

United States Courts Al-10, and a factor in the ability of fed

eral courts to dispose cases expeditiously. While these considera

tions do not affect the interpretation of the Seventh Amendment,

the impact of jury trials on court dockets and budgets might prop

erly be considered in determining whether to grant certiorari.

10

prejudice will seriously affect the Act’s credibility to racial

minorities. Attempting to buy a house when it means buy

ing a lawsuit as well is difficult enough, but when the judges

of fact are drawn from the excluding community the effort

will seem impossible to many. Unless minorities believe

the law will be fairly administered, it will be a dead letter.

F in ally , ju d ic ia l efficiency w arrants rev iew at this tim e

o f the ju r y issue in T itle V I I I actions. W h ile this is

the first appellate decision on the righ t to ju ries in actions

fo r dam ages under S ection 812,8 d istrict courts are fa c in g

the issue w ith increasin g frequ en cy .9 T hose that decide

in correctly m ay be required to re -try cases. T hose that

fo llo w the opin ion below w ill soon con fron t m yriad ques

tions con cern ing the a llocation o f functions betw een ju dge

and ju ry . W e subm it this C ourt should render early ju d g

m ent on the threshold question w hether ju ries are required

to guide low er fed era l courts in their adm inistration o f

this new and im portant law.

8 One appellate court has denied the right to a jury trial in an

action by the United States for injunctive relief only pursuant to

Section 813 of the Act, 42 U.S.C. § 3613. United States v. Beddoch,

No. 72-1326 (5th Cir., Oct. 4,1972).

9 E.g., Cauley v. Smith, 347 F.Supp. 114 (E.D. Va. 1972) (jury

trial denied) ; Marr v. Rife, Civ. No. 70-218 (S.D. Ohio, Aug. 3i,

1972) (jury trial denied); Kastner v. Brackett, 326 F.Supp. 1151

(D. Nev. 1971) (jury trial granted).

11

II.

The Statute Provides That Issues of Fact in Actions

for Injunctive Relief and Damages Be Tried by Judges

Without Juries.

Only a strained reading of Section 812 of the Civil Rights

Act of 1968 would support a conclusion that in an unspeci

fied way Congress fragmented between judge and jury the

remedial powers necessary to enforce the fair housing law.

Every indication is that Congress assigned to judges alone

the task of determining liability and integrating the array

of possible remedies—injunctions, actual damages, punitive

damages, and attorney’s fees—into effective unified judg

ments which achieve the objectives of the law.

The “ court” which enforces the statute is described in

terms defining judges not juries. Section 812(a) mandates

continuances “ if the court believes” that conciliation will

be successful. Section 812(b) provides the court may ap

point attorneys and authorize actions without fees, costs,

or security “ in such circumstances as the court may deem

just.” Finally, Section 812(c) provides:

The court may grant as relief, as it deems appro

priate, any permanent or temporary injunction, tem

porary restraining order, or other order, and may

award to the plaintiff actual damages and not more

than $1000 punitive damag-es, together with court costs

and reasonable attorney fees in the case of a prevailing

plaintiff: Provided, that the said plaintiff in the

opinion of the court is not financially able to assume

said attorney’s fees.

The judicial processes involved in “if the court believes,”

“as the court may deem just,” “ the court may grant relief,

12

as it deems appropriate,” and “ in the opinion of the court”

all convey determinations of judges, not juries.10

Debates in Congress immediately preceding the Act’s

adoption are not helpful, but the early history of the Act

sheds some light. The origin of Section 812(c) is President

Johnson’s proposed Civil Rights Act of 1966.11 Section

406 of the administration bill provided that in actions to

enforce the proposed fair housing title:

(c) The court may grant such relief as it deems ap

propriate, including a permanent or temporary injunc

tion, restraining order, or other order, and may award

damages to the plaintiff, including damages for hu

miliation and mental pain and suffering, and up to

$500 punitive damages.

(d) The court shall allow a prevailing plaintiff a

reasonable attorney’s fee as part of the costs.12

Attorney General Katzenbach testified about the right to

a jury trial under the administration proposal:

10 Lower federal courts consistently rule that similar language

in Title V II of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 does not require trial

by jury. That act provides “ if the court finds” racial discrimination

in employment “ the court” may order injunctive relief and back

pay. 42 U.S.C. § 2000e-5(g) (1970). Legislative history confirms

that juries are not required, 110 Cong. Rec. 7255 (1964), and with

out exception courts deny employer demands for juries. E.g.,

Johnson v. Georgia Highway Express, 417 F.2d 1122, 1125 (5th

Cir. 1969) ; Lowry v. Whitaker Cable Corporation, 348 F.Supp.

202, 209 fn. 3 (W.D. Mo. 1972) ; Williams v. Travenol Laboratories,

344 F.Supp. 163 (N.D. Miss. 1972); Cheatwood v. South Central

Bell Telephone and Telegraph Co., 303 F.Supp. 754 (M.D. Ala.

1969); Culpepper v. Reynolds Metals Co., 296 F.Supp. 1232 (N.D.

Ga. 1968), rev’d on other grounds, 421 F.2d 888 (5th Cir. 1970).

There is no reason to believe that Congress in assigning civil rights

enforcement responsibilities to the courts varied the definition of

“ the court” from one major enactment to another.

11112 Cong. Rec. 9390 (1966).

12 S. 3296, § 406,112 Cong. Rec. 9397 (1966).

13

Senator Ervin. Now, I would like to know under the

same subsection (c) of section 408 (sic) who deter

mines the amount of damages that are to be awarded

if a case is made out under Title IV of the bill.

Attorney General Katzenbach. The court does.

Senator Ervin. That is the judge.

Attorney General Katzenbach. Yes, sir.

Senator Ervin. There is no jury trial.

Attorney General Katzenbach. No, sir.18

The Attorney General, on several other occasions, indicated

that juries were not intended by explaining that the bill

authorized punitive damages “ in the court’s discretion.” 14

Between the administration’s first proposal in 1966 and

the enactment of Title VIII in 1968, the Act underwent

many changes, primarily in the formulation and abandon

ment of proposals for administrative enforcement. In the

end, Congress elected judicial enforcement in a form essen

tially similar to the administration’s 1966 proposal. Con- 13 *

13 Hearings on S. 3296 before the Subcomm. on Constitutional

Rights of the Senate Committee on the Judiciary, 89th Cong., 2nd

Sess., pt. 2, at 1178 (1966). In the continuation of this exchange

Attorney General Katzenbach modified this answer in cases in

which no injunctive relief but only damages are sought:

Senator Ervin. Well, is the administration opposed to or

has it forsaken the ancient American love for trial by jury?

Attorney General Katzenbach. No, sir, I assume if there

was a suit here that was purely for damages that the court

would use a jury. Hid, emphasis added.

Petitioner’s action cannot be described as an action “ purely for

damages.” It was brought as an action for injunctive relief and

damages, and the Court of Appeals acknowledged that the right to

a jury is tested by the relief requested in the complaint (25a).

u Id., pt. 1, at 84; Hearings on H.R. 14765 Before Subcommittee

No. 5 of the House Comm, on the Judiciary, 89th Cong., 2nd Sess.,

ser. 16, at 1057, 1070 (1966); 112 Cong. Rec. 9399 (1966).

14

gress deleted specific authority to recover damages for

humiliation, mental pain, and suffering, increased the au

thorized award of punitive damages, and modified the at

torney’s fees requirement; but, apart from these changes,

the present enforcement provision is the one Attorney

General Katzenbach described to Congress in 1966. It

should be interpreted now as it was interpreted to Con

gress by its principal spokesman, and consistent with its

text not be read to require juries in actions for injunctive

relief and damages.

Court trials serve important statutory objectives. Section

814 requires that enforcement actions “be in every way

expedited.” In fair housing cases, most facts relevant

to final judgment are presented at preliminary injunction

hearings only days after the filing of complaints. Then,

final determinations are expedited by incorporating this

evidence into trial records, as was done in this case. If

juries are mandated, parties will be required to re-try facts

already tried before judges at preliminary injunction

hearings. A statutory construction requiring re-trials

hardly comports with a command that actions “be in every

way expedited.” Also, court rather than jury trials serve

the Congressional objective of minimizing the cost of liti

gation. Congress authorized the appointment of attorneys,

the commencement of actions without fees, costs, or secu

rity, and the award of attorney’s fees to prevailing plain

tiffs. The increased costs resulting from re-trial of facts

would seriously undermine the effort to create an inexpen

sive judicial remedy. “Due consideration of the structure

and purpose of the . . . Act as a whole, as well as the

particular provisions of the Act brought in question,” 15

confirms that Congress intended issues of fact in Title VIII

actions to be determined by judges not juries.

15 Katchen v. Landy, 382 U.S. 323, 328.

15

III.

The Seventh Amendment Does Not Prevent Congress

From Enforcing the Fair Housing Law in Federal Courts

Without the Intervention of Juries.

The court of appeals relied on a canon that statutes

should be construed to avoid “grave doubts” of constitu

tionality (33a). While this may be proper in clashes be

tween constitutional values and ordinary statutes, this case

poses a different problem. Title VIII enforces the

Thirteenth and Fourteenth Amendments to the United

States Constitution,16 and the “cherished aims” 17 which

underlie these amendments. This Court should not allow

the constitutional values expressed in Title VIII to be

frustrated by canons of construction. The judgment of

Congress that it is appropriate to enforce the Civil War

amendments in court rather than jury trials should be set

aside only on the squarest holding that the Seventh Amend

ment requires otherwise. Nothing in that amendment or

the decisions of this Court requires any such conclusion.

a. Actions to Enforce Title VIII Are Not in the Nature of

Suits at Common Law.

The Seventh Amendment preserves the right to trial by

jury “ in suits at common law” to the extent the right was

known when the Amendment was adopted.18 In time, the

16 Following Jones v. Mayer, 392 U.S. 409, federal courts have

held that Title V III is an appropriate exercise of Congressional

power under the Thirteenth Amendment. United States v. Hunter,

459 F.2d 205, 214 (4th Cir. 1972) ; United States v. Beal Estate'

Development Corporation, 347 F.Supp. 776, 781 (N.D. Miss. 1972);

United States v. Mintzes, 304 F.Supp. 1305, 1312 (D. Md. 1969) ;

Brown v. State Realty, 304 F.Supp. 1236, 1240 (N.D. Ga. 1969).

17 Railway Mail Ass’n v. Corsi, 326 U.S. 88, 98 (Frankfurter, J.,

concurring).

18 Baltimore & C. Line v. Redman, 295 U.S. 654, 657.

16

question has evolved to be whether a controversy is “ in the

nature of a suit at common law.” 19 Thus, while the Amend

ment’s application to rights created by statute rather than

judicial decision is not precluded,20 the question remains

whether particular statutory rights bear sufficient rela

tion to rights known to the common law in 1791 to fall

within the Amendment’s limited scope.

The rights created by Title VIII of the Civil Rights Act

of 1968 are not remotely related to anything known to the

common law in 1791. Although by that time English com

mon law no longer enforced the state of slavery,21 a slave

who continued to work for a master was not entitled to

wages.22 The limited common law rights of blacks in

19 N.L.B.B. v. Jones & Laughlin Steel Corp., 301 U.S. 1, 48.

20 While the Seventh Amendment may apply to some federal

statutes, the Seventh Circuit was incorrect in stating that the

“ principal significance” of the amendment has been in the trial of

federal questions (16a-17a). To the contrary, the primary reach

of the amendment has always been diversity actions in which

ordinary common law disputes are litigated. Indeed, both Massa

chusetts and New Hampshire in their call for a federal bill of

rights focused on civil juries in diversity suits, and proposed that:

“ VIII. In civil actions between citizens of different states,

every issue of fact, arising in actions at common law, shall be

tried by a jury . . . .”

I. J. Eliot, The Debates in the Several State Conventions

on the A doption op the F ederal Constitution 323, 326 (2d ed.)

(emphasis added). The framers of the Seventh Amendment also

framed the First Judiciary Act, which conferred no general federal

question jurisdiction on federal courts. Thus, with only limited

exceptions, civil juries in federal courts were confined for an

extended period to common law diversity actions. Even today, the

number of jury trials in diversity actions far exceeds the number

in federal question actions. A dministrative Office of the United

States Courts, 1972 A nnual Report of D irector A-23.

21 Somerset v. Stewart, 98 Eng. Rep. 499 (K.B. 1772).

22 King v. Inhabitants of Thames Ditton, 99 Eng. Rep. 891

(1785); A. Lester & G. B indman, Race and Law 32 (1972).

17

England did not extend outside England; slavery was not

abolished in English colonies until 1834. More generally,

“English judges have never declared that acts of racial

discrimination committed [in England] are against public

policy.” 23 In this country, the Constitution acknowledged

slavery24 and this Court interpreted it to deny citizenship

to freed blacks.25 It required a civil war before “ slavery,

as a legalized social relation, perished,” 26 and the Consti

tution amended to authorize Congress “ to pass all laws

necessary and proper for abolishing all badges and inci

dents of slavery. . . . ” 27 No analogy to the duties of En

glish innkeepers28 overcomes the fact that Title V III’s

origins are not English common law but rather a major

constitutional revolution long after the adoption of the

Seventh Amendment.29

The Seventh Circuit also attributed a common law char

acter to this action because the original tribunal in Title

V III actions is a court, not an administrative agency. It

reads this Court’s decision in N.L.B.B. v. Jones & Laughlin,

301 TT.S. 1, to require Congress to choose between admin

istrative agencies or juries, without the intermediate pos

23 A. Lesteb & G. B indman, supra note 22, at 25.

24 Art. I, § 2, art. IV, § 2.

26 Bred Scott v. Sanford, 60 U.S. (19 How.) 393.

26 Slaughter-House Cases, 83 U.S. (16 Wall.) 36, 68.

27 Civil Bights Cases, 109 U.S. 3, 20.

28 Even among public accommodations the innkeeper’s duties

had limited scope, and did not include lodging houses, boarding

houses, private residential hotels, places of entertainment, and

restaurants. A. Lesteb & G. Bindman, supra note 22, at 65.

29 Compare Culpepper v. Reynolds Metals Company, 296 P.Supp.

at 1241: “ The focus of [Title V II] is upon the elimination of dis

crimination in employment, the freedom from which there was no

guarantee at common law.”

18

sibility of court trials. We doubt this Court intended to

limit Congressional options in enforcing modern statutes.

It is not the forum, but the nature of the claim which deter

mines the constitutional issue. If the Constitution allows

the claim to be adjudicated without a jury, then Congress

should be permitted latitude in determining how the law

should be enforced.

b. A Court in a Title VIII Action Acts as a Court of Equity

With Power to Afford Complete Relief.

The common element in all fair housing proposals con

sidered by Congress was that any law should be enforced

—whether by courts, the Secretary of Housing and Urban

Development, or a Fair Housing Board—by orders com

pelling cessation of racially discriminatory housing prac

tices.30 Title VIII supplements this with the power to

award damages, but the Act’s basic authority is the power

to order the actual provision of housing on a non-dis-

criminatory basis. Thus, a court enforcing Title VIII may

fairly be characterized in historical terms as a court of

equity. As such, it has power “to decree complete relief and

for that purpose may accord what would otherwise be legal

remedies.” 31

The power of the English chancellor to both issue an

injunction and decree an account for waste was well estab

lished when the Seventh Amendment was adopted.32 In

this country, the acknowledged power of a court of equity

30 Compare S.3296, the administration’s 1966 bill, 112 Cong.

Rec. 9396 (1966) and H.R. 14765, as modified and passed by the

House, 112 Cong. Ree. 18739 (1966), with Senator Mondale’s

amendment, 114 Cong. Rec. 2270 (1968), and Senator Dirksen’s

substitute, 114 Cong. Ree. 4570-73 (1968).

31 Katchen v. Landy, 382 U.S. at 338.

32 Jesus College v. Bloom, 26 Eng. Rep. 953 (Ch. 1745).

20

remedies which may be used “as it deems appropriate.”

Section 812(c). The court’s exercise of discretion is un

doubtedly governed by the purpose of the statute,37 but

within it the court has the power to select or group the

remedies made available by Congress.38 Therefore, in no

sense do “damages” constitute a separate claim. The “basic

character” 39 of a Title VIII action is not determined by the

fact that one among several remedies made available by

the statute is money damages.

Third, Beacon Theatres, Dairy Queen, and Ross differ

markedly from actions to enforce Title VIII. The dispute

in Beacon Theatres arose under the antitrust laws, which

this Court construes to create a statutory right to trial

by jury.40 The basic controversy in Dairy Queen involved

an alleged breach of contract.41 The corporation’s claim in

Ross included ordinary breach of contract and negligence.42

In contrast, under Title VIII there is “a specific statutory

scheme contemplating the prompt trial of a disputed claim

without the intervention of a jury.” 43

Finally, “ the rule of Beacon Theatres and Dairy Queen

. . . is itself an equitable doctrine . . . .” 44 Equity often

decreed complete relief to avoid multiple actions. Yet, jury

trials under Title VIII would require re-trial of facts heard

37 Cf. Mitchell v. De Mario Jewelry, 361 TJ.S. 288, 296.

38 One example of the interrelationship of possible remedies is

Jones v. Mayer where this Court thought injunctive relief could

be fashioned which would obviate any actual damage problem.

392 U.S. at 414 fn. 14.

39 Simler v. Conner, 372 U.S. 221, 223.

40 359 U.S. at 504.

41 369 U.S. at 477.

42 396 U.S. at 542.

43 Katchen v. Landy, 382 U.S. at 339.

44 i m .

21

expeditiously by district courts at preliminary injunction

hearings, a wasteful result which equity does not require.

c. There Is No Right to a Jury Trial in Respect to the Limited

Punitive Damages Remedy Available Under the Statute.

The court of appeals discussed actual damages hypothet

ically. The complaint alleged no actual damages, the dis

trict court permitted no testimony of actual damages be

yond offers of proof, and the judgment included no award

for actual damages. It is only punitive damages which the

complaint requested and the district court granted.

The case for jury determination of punitive damage

awards has even less merit than the case for jury determina

tion of actual damages. At least, when juries are required

by statute or common law in actions seeking actual dam

ages there is work for the jury as a fact-finder. The jury

must determine whether there are “actual” damages, and

must determine whether one party’s unlawful behavior is

the proximate cause of the other party’s injury. There are

no equivalent findings to be made in a case involving

punitive damages. If this were a common tort action, it

might be necessary to find that the defendants acted “ma

liciously” or “wantonly.” But this is an action pursuant

to a statute which provides that “ the court may award . . .

not more than $1000 punitive damages . . .” as a remedy

for violation of a statute which requires no finding of

malice.46 Therefore, beyond the findings of fact necessary

46 In Newman v. Piggie Park Enterprises, 390 U.S. 400, this

Court considered a related problem in construing the attorney’s

fee provision in Title II of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, 42 U.S.C.

§ 2000a-3(b), which provides that “ the court, in its discretion, may

allow the prevailing party . . . a reasonable attorney’s fee . . . .”

The Court rejected the traditional rule limiting award of attorney’s

fees to cases of “ bad faith” defenses:

If Congress’ objective had been to authorize the assessment

of attorney’s fees against defendants who make completely

22

to sustain a judgment that the Act has been violated—

findings which would have to be made in an action for in

junctive relief only—no further findings are necessary to

authorize an award of punitive damages.

The court of appeals found it “highly unusual” for a

federal statute to authorize punishment without a jury trial

(20a). Yet, judges in patent infringement actions have

long had the power to punish by trebling actual damages.* 46

Although juries may determine actual damages in many of

these cases, nevertheless, judges not juries decide whether

to punish, and at times Congress has conferred on courts

of equity both the power to decree accounts without juries

and treble damages in their discretion.47

Moreover, nothing in our common law tradition precludes

the infliction of limited money punishments without juries.

If Congress had chosen to make discrimination an offense

punishable by a $1000 fine only, but no term in prison, the

Constitution would not require a jury trial.48 It would be

an odd historical result to require a jury to award $1000

groundless contentions for purposes of delay, no new statutory

provision would have been necessary, for it has long been

held that a federal court may award counsel fees to a success

ful plaintiff where a defense has been maintained ‘in bad faith,

vexatiously, wantonly, or for oppressive reasons.’

Id. at 402 fn. 4. Similarly, a new statutory provision would not

have been necessary to authorize a punitive damage award for

malicious or wanton behavior, and Title V III should not be read

to require a finding of malice.

46 Seymour v. McCormick, 57 U.S. (16 How.) 480, 489; Kennedy

v. Lakso Co., 414 F.2d 1249, 1254 (3rd Cir. 1969) ; Swofford v.

B & W, Inc., 336 F.2d 406, 413 (5th Cir. 1964), cert, denied, 379

U.S. 962.

47 Tilgham v. Proctor, 125 U.S. 136, 148-49; Filer <& Stowell Co.

v. Diamond Iron Works, 270 F. 489 (7th Cir. 1921).

48 Argesinger v. Hamlin, 407 U.S. 25, 45 fn.2 (concurring opin

ion).

23

punitive damages, while a judge alone could impose a

$1000 fine.

Finally, the role of punitive damages in the enforcement

of the fair housing law should be considered. Often they

are an essential complement to a court’s injunctive power.

Fair housing cases present myriad situations to district

courts. There are times when the coercive effect of injunc

tions may be sufficient to assure compliance with the law.

There are also times when it may be preferable to coerce

future compliance with a present award of punitive dam

ages in place of the ongoing supervision which an injunc

tion may require. There are other times when a combina

tion of injunction and punitive damages may best assure

the effectiveness of the Act. Congress decided it would be

appropriate to enforce the right to fair housing by giving

one decision maker an array of powers which could be used

individually or in combination as necessary to enforce the

Act in particular circumstances. In this light, punitive

damages under Title VIII are best seen as an adjunct to

the district court’s equitable powers to coerce compliance

with this important statute.

24

IV.

The Decision of the Seventh Circuit Conflicts in

Principle With Decisions in Other Circuits on the Right

to Juries in Related Civil Rights Actions.

Other courts of appeals have uniformly rejected demands

for juries in employment discrimination cases. Some of

these actions were under Title VII of the Civil Rights Act

of 1964,49 50 and others under 42 TJ.S.C. § 1983.60 All sought

injunctive relief and money awards to compensate for lost

pay, and in all the courts held that back pay awards were

part of an equitable remedy.

The decision of the Seventh Circuit seriously jeopardizes

this heretofore unbroken line of cases. The court below

attempts to distinguish them by analogizing the award of

lost pay to the restitution of “ill-gotten gains” (29a), but

another court has already exposed the fragile basis of char

acterizing back pay as a uniquely equitable remedy by

showing that a common law lawyer would have had no

trouble placing back pay under the rubric of indebitatus

assumpsit or an action for breach of contract by wrongful

discharge.61 Whether these statutorily authorized money

49 Johnson v. Georgia Highway Express, Inc., 417 F.2d 1122,

1125 (5th Cir. 1969); cf. Rohinson v. Lorillard Corporation, 444

F.2d 791, 802 (4th Cir. 1971). Even “the use of advisory juries

in discrimination cases is not favored. . . .” Moss v. The Lane

Company, No. 72-1628 (4th Cir., Jan. 11,1973).

50 McFerren v. County Board of Education, 455 F.2d 199 (6th

Cir. 1972) ; Harkless v. Sweeny Independent School District, 427

F.2d 319 (5th Cir. 1970), cert, denied, 400 U.S. 991; Smith v.

Hampton Training School, 360 F.2d 577 (4th Cir. 1966). The

Equal Employment Opportunity Act of 1972, Pub. L. 92-261, § 2

(1 ), now makes it possible to bring employment discrimination

cases involving government employers under Title VII.

61 Ochoa v. American Oil Co., 338 F.Supp. 914, 918 (S.D. Tex

1972):.

25

awards are called “actual damages” or “back pay” tbeir

purpose is to remedy an injury caused by unlawful conduct

by making victims “whole.” 52

The determination whether or not juries are required

cannot depend on a tenuous labeling of money damages as

equitable or legal. Rather, it depends on whether Congress

has the power to authorize federal judges not only to order

injunctive relief but also award money damages to provide

complete relief in enforcing civil rights legislation. The

decision of the Seventh Circuit that Congress lacks this

power conflicts at least in principle and effect with deci

sions of other circuits. It would be appropriate for this

Court to resolve this conflict and provide authoritative

guidance to lower federal courts in their administration of

the civil rights laws.

62 Bowe v. Colgate-Palmolive Company, 416 F.2d 711 721 (7th

Cir. 1969).

26

CONCLUSION

The writ of certiorari should be granted,

Respectfully submitted,

J ack Greenberg

M ichael D avidson

10 Columbus Circle

New York, N.Y. 10019

P atricia D. M cM ahon

Freedom Through Equality, Inc.

152 West Wisconsin Ave.

Milwaukee, Wisconsin 53203

S eymour P ikoesky

Milwaukee Legal Services

2200 North Third St.

Milwaukee, Wisconsin 53212

Attorneys for Petitioner

Charles L. B lack , J r .

Of Counsel

APPENDIX

la

May 19, 1970

R ey n olds , District Judge.

This is an action brought under Title VIII of the Civil

Rights Act of 1968, 42 U.S.C. §§ 3601-3619, which prohibits

discrimination in the rental of housing. Plaintiff claims

that defendants discriminated against her by refusing to

rent her an apartment because she is a Negro. Plaintiff

requested injunctive relief restraining the rental of the

subject apartment except to the plaintiff, money damages

for loss incurred by the plaintiff due to the alleged dis

crimination, punitive damages in the amount of $1,000,

and attorney’s fees.

The court granted plaintiff’s motion for a temporary

restraining order on November 17, 1969, and, following an

extended hearing, entered a preliminary injunction tem

porarily restraining the rental of the apartment pending

final determination of the case. At a hearing on April

30, 1970, the Court, with consent of plaintiff, dissolved

the preliminary injunction. Therefore, the only issues re

maining in the suit are plaintiff’s claim for compensatory

and punitive damages and attorney’s fees.

The defendants have requested a jury trial on these

issues, and plaintiff has objected to this request. The par

ties have submitted briefs and argued to the court on this

issue which is now before the court for decision.

[1, 2] To warrant a jury trial, a claim must be of such

a nature as would entitle a party to a jury at the time of

the adoption of the Seventh Amendment. NLRB v. Jones

& Laughlin Steel Corp., 301 U.S. 1, 57 S.Ct. 615, 81 L.Ed.

District Court’s Opinion and Order

Denying Demand for Jury Trial

2a

893 (1936); United States v. Louisiana, 339 U.S. 699, 70

S.Ct. 914, 94 L.Ed. 1216 (1950). The question before this

court, therefore, is whether the cause of action under 42

U.S.C. §§ 3601-3619 is one recognized at common law which

consequently requires a jury trial. I find that this cause

of action is a statutory one invoking the equity powers of

the court, by which the court may award compensatory and

punitive money damages as an integral part of the final

decree so that complete relief may be had. The action is

not one in the nature of a suit at common law, and there

fore there is no right to trial by jury on the issue of

money damages in the case.

Defendant argues that the Seventh Amendment of the

Constitution; Beacon Theatres, Inc. v. Westover, 359 U.S.

500, 79 S.Ct. 948, 3 L.Ed.2d 988 (1959); Thermo-Stitch,

Inc. v. Chemi-Cord Processing Corp., 294 F.2d 486 (5th

Cir. 1961); Dairy Queen, Inc, v. Wood, 369 U.S. 469, 82

S.Ct. 894, 8 L.Ed.2d 44 (1962) ; Harkless v. Sweeny In

dependent School District, 278 F.Supp. 632 (S. D. Texas

1968); and Boss v. Bernhard, 396 U.S. 531, 90 S.Ct. 733,

24 L.Ed.2d 729 (1970), require a jury trial on the issue

of plaintiff’s prayer for money damages due to the alleged

discrimination.

Beacon, Dairy Queen, and Thermo-Stitch hold that where

equitable and legal claims are joined in the same cause

of action, there is a right to trial by jury on the legal

claims that must not be infringed by trying the legal issues

as incidental to the equitable issues or by a court trial of

common issues between the two. The Court in Swofford v.

B & W, Inc., 336 F.2d 406, 414 (5th Cir. 1964), commented

on these cases:

District Court’s Opinion and Order

Denying Demand for Jury Trial

3a

“ * # * This is not to say, however, that they have

converted typical non-jury claims, or remedies, into

jury ones. Therefore, we reject a view that the trio of

Beacon Theatres, Dairy Queen, and Thermo-Stitch is

a catalyst which suddenly converts any money request

into a money claim triable by jury.”

The Darkless court granted a jury trial on the issue

of back pay award in an action brought under 42 U.S.C.

§ 1983 seeking reinstatement as teachers following a dis

charge allegedly based on racial discrimination. However,

§ 1983 expressly provides that persons acting under color

of state law who deprive other persons of constitutional

rights shall be liable “ in an action at law.” There is no

such provision in 42 U.S.C. § 3612(c).

The Supreme Court in Boss held that plaintiffs in a

shareholder’s derivative action had a right to a jury trial

on those issues to which the corporation, had it brought

the action itself, would have had the right to a jury trial.

The Court found that where the claims asserted were dam

ages against the corporation’s broker under the brokerage

contract and rights against the corporate directors because

of their negligence, both actions at common law, “ * * * it

is no longer tenable for a district court, administering both

law and equity in the same action, to deny legal remedies

to a corporation, merely because the corporation’s spokes

men are its shareholders rather than its directors. * * *”

396 TJ.S. at 540, 90 S.Ct. at 739. While Ross may reflect

“an unarticulated but apparently overpowering bias in

favor of jury trials in civil actions,” Boss, supra, at 551,

90 S.Ct. at 745, Justice Stewart dissenting, the case does

District Court’s Opinion and Order

Denying Demand for Jury Trial

4a

not stand for the proposition that any money claim in a

cause of action must be tried by a jury. The decision deals

narrowly with the right to jury trial in a shareholder’s

derivative action and is clearly distinguishable from the

case before this court.

The section of the statute dealing- with remedies for

violation of the act, 42 U.S.C. § 3612(c), provides:

“ (c) The court (emphasis added) may grant as re

lief, as it deems appropriate, any permanent or tempo

rary injunction, temporary restraining order, or other

order, and may award to the plaintiff actual damages

and not more than $1,000 punitive damages, together

with court costs and reasonable attorney fees in the

case of a prevailing plaintiff: Provided, That the

said plaintiff in the opinion of the court (emphasis

added) is not financially able to assume said attorney’s

fees.”

On its face, this statutory language seems to treat the

actual damages issue as one for the trial judge rather than

a jury. District courts in Hayes v. Seaboard Coast Line

Railroad Co., 46 P.R.D. 49 (S.D.Gla.1969), and Cheatwood

v. South Central Bell Telephone and Telegraph Co., 303

F.Supp. 754 (M.D.Ala. 1969), have construed similar lan

guage in Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, 42

U.S.C. § 2000e-5(g),* to mean that the issue of back pay

District Court’s Opinion and Order

Denying Demand for Jury Trial

* “ I f the court finds that the respondent has intentionally en

gaged in or is intentionally engaging in an unlawful employment

practice charged in the complaint, the court may enjoin the respon

dent from engaging in such unlawful employment practice, and

order such affirmative action as may be appropriate, which may

5a

award in employment discrimination cases does not require

jury determination.

Both Hayes and Cheatwood held that the money dam

ages issue of back pay in an action under 42 U.8.C. § 2000e-

5(g) of the 1964 Civil Bights Act was not a separate legal

issue, but rather was a remedy the court could employ for

violation of the statute in a statutory proceeding unknown

at common law, and that there was no right to a trial by

jury on that issue. As I have noted, the language of the

remedial provisions of 42 U.S.C. §2000e-5(g) of the Civil

Bights Act of 1964 and 42 U.S.C. § 3612(c) of the Civil

Bights Act of 1968 are very similar. The purpose of the

two acts is similar. Title YII of the 1964 Act prohibits

discrimination on the basis of race, color, religion, sex, or

national origin by specified groups of employers, labor

unions, and employment agencies. Title VTTT of the 1968

Act prohibits discrimination on the basis of race, color,

religion, or national origin in the sale or rental of housing

by private owners, real estate brokers, and financial insti

tutions. The award of money damages in a Title VIII

action has the same place in the statutory scheme as does

the award of back pay in a Title VII action. Determining

the amount of a back pay award in a Title VII action

can be as difficult a question of fact as determining the

amount of money damages in a Title VIII action. Hayes,

46 F.B.D. at 53.

An action under Title VIII is not an action at common

law. The statute does not expressly provide for trial by

include reinstatement or hiring of employees, with or without

back pay (payable by the employer, employment agency, or labor

organization, as the case may be, responsible for the unlawful em

ployment practice). # * * ” (Emphasis added.)

District Court’s Opinion and Order

Denying Demand for Jury Trial

6a

jury of any issues in the action. In the absence of a clear

mandate from Congress requiring a jury trial, I find that

the similarities between the remedial provisions of the

Civil Eights Act of 1964 and 1968, in light of the undivided

authority holding that the issue of money damages for

back pay under Title VII of the 1964 Act is not an issue

for the jury, compel the conclusion that the issue of com

pensatory and punitive money damages in an action under

Title VIII of the 1968 Act is likewise an issue for the

court. Accordingly, defendants’ request for a jury trial

must be denied.

Therefore, it is ordered that defendants’ request for a

jury trial be and it hereby is denied.

District Court’s Opinion and Order

Denying Demand for Jury Trial

7a

October 27, 1970

[205] * * #

The Court: All right. Well, this has been a long and

tortuous lawsuit. The action was brought under Title VIII

of the Civil Eights Act of 1968, 42 U.S. Code Section

3601-19 which prohibits discrimination in the rental of

housing. The Plaintiff has claimed that she was discrim

inated against by the Defendants in that they refused to

rent her an apartment because she was a Negro. The

Plaintiff has requested injunctive relief restraining the

rental of the apartment except to her, money damages

for loss that she has sustained due to the alleged dis

crimination and punitive damages in the amount of $1,000

and attorney’s fees.

I granted the Plaintiff’s motion for temporary restrain

ing order on November 17th, 1969 following an extended

hearing, entered a preliminary injunction temporarily

restraining the rental of the apartment pending final deter

mination of the Court. At that time, [206] of the prelimi

nary hearing, I found there was probable cause to believe

there was discrimination in this case and that she could

probably establish that on a final hearing.

The Court had many conferences with the parties trying

to work this out. But to no avail. And at one of those,

on the hearing of April 30th, 1970, the Court with the

consent of the Plaintiff dissolved the preliminary injunc

tion because by that time the Plaintiff was no longer

interested in the apartment. Therefore, the only issue

remaining for this hearing today, yesterday and today,

was for the claim—the final hearing on the question of

District Court’s Oral Findings of

Fact and Conclusions of Law

8a

discrimination and the claim for compensatory and puni

tive damages and attorney’s fees.

It appears that on, from the evidence and the entire

file and both hearings, October 30, 1969 an advertisement

appeared in the Milwaukee Journal, a newspaper published

in this city offering for rent this apartment which was

located at 2529 North Fratney Street, Milwaukee, Wis

consin. And it appears that Plaintiff Julia Rogers is a

black American and Miss Jacqueline Haessly is Caucasian,

and the Defendants are at least white, I don’t know if they

are Caucasian, I never know what these things are, but

they are white. At the time the ad appeared in the paper,

Mrs. Rogers was hospitalized [207] at St. Mary’s Hospital

here in Milwaukee. The ad was seen by her friend, Miss

Haessly, who called the number given and spoke to the

Defendant Mrs. Perez. She asked Mrs. Perez if it would be

possible to see the apartment and Mrs. Perez told her she

could come over if she could get there by 5 :00 p.m. of that

day. Miss Haessly went to see the apartment, arriving

there at 4:30 p.m. on October 30th, 1969. Mrs. Perez is a

cousin of Mrs. Loether and Mrs. Perez took Miss Haessly

to see the upstairs apartment. Miss Haessly told Mrs.

Perez that she was looking* for a place for a friend of hers

who was in the hospital. Mrs. Perez stated that Mr. and

Mrs. Loether were coming over that evening, that they

would have to make the decision as to whether or not Miss

Haessly could have the apartment for Mrs. Rogers. Miss

Haessly stated that she was very interested in obtaining

the apartment and asked Mrs. Perez if she, that is Mrs.

Haessly, should offer a deposit, and would the deposit be

accepted. Mrs. Perez told Miss Haessly that she would

call Mrs. Loether and Mrs. Loether was in fact called and

District Court’s Oral Findings of

Fact and Conclusions of Law

9a

Miss Haessly spoke to Mrs. Loether and to find out whether

or not a deposit would be accepted.

It appears that in that conversation, Mrs. Loether asked

various questions about Mrs. Eogers, such as where she

was hospitalized, how many children in the [208} family,

marital status and financial status, hut in any event, did

not ask about race, and Mrs. Loether then asked to speak

to Mrs. Perez and Mrs. Perez as a result of these conver

sations was authorized by Mrs. Loether to accept a deposit

and to give a receipt. At least she did accept a deposit

and she did give a receipt.

And up until that time, there was no problem. I think

up until that time, there is no question in my mind, that

the apartment was rented, at least effectively rented. Then

Mrs. Loether requested Mrs. Haessly and was given the

hospital room number and she talked to Mrs. Rogers and

then she called Mrs. Rogers at the hospital and discussed

the rental of the apartment at which time Mrs. Rogers

advised Mrs. Loether that she, Mrs. Rogers, was a black

person. Then for the first time the question of race came

up and Mrs. Loether became concerned about the race of

the prospective tenant and, as I see it, the rental of the

apartment was revoked at that stage and it was revoked

because of race, at which time Miss Haessly came back

into the picture and made it clear to Mrs. Loether that

that was against the law, she could not do that. And the

testimony indicates it was about this time that Mr. Loether

came in and also learned that he was told that he had to

rent this apartment to someone that he didn’t want to rent

it to, and that he believed that no one is going to tell him

District Court’s Oral Findings of

Fact and Conclusions of Law

10a

what to do. Well, that is a difficult question. I think that

the law does tell him what to do. And he may find that

very difficult to accept. But it is the law nevertheless. The

deal was closed, it was effectively closed. Mrs. Perez in

effect became the agent of these people to rent the apart

ment. She rented the apartment and then the deal, after

it was closed, when race was mentioned, it was revoked

and then I think that the acts of Miss Haessly in telling

them—I am not saying she didn’t have a right to do this,

but I think her act of telling the Loethers that they had

to rent it probably hardened their position. In short, I

think but for the race of Mrs. Rogers, she would have had

the apartment, because that was the only question these

people were talking about from that time on. They haven’t

discussed anything else really.

I don’t believe it’s necessary for me to go into all the

details—well, I might as well. In any event, Mrs. Loether

who then actually went to see Mrs. Rogers at the hospital,

to see if they could work out something, hut it turned out

that that could not be worked out.

I am also mindful of the fact that Mr. Loether, being a

little stubborn about this, and I do not look [210] upon

the Loethers certainly as the worst and most bigotted

people I have come in contact with in this world, and

that is what makes this case more difficult than some.

Now, we get to the questions—although I am satisfied

that there is only one conclusion I can reach and that is

the apartment was not rented because of the race of Mrs.

Rogers and therefore it’s a violation of the Federal law.

District Court’s Oral Findings of

Fact and Conclusions of Law

11a

Now, we come to the questions of damages. The Loethers

have indicated or did indicate they were willing to rent

this to a black person but they consistently maintained the

position they were not willing to rent it to Mrs. Rogers,

and therefore I think that that—here we are interested

in Mrs. Rogers’ rights, but I recognize the property was

vacant for an extended period of time and the Loethers

have been subjected to a lot of expenses. I do not believe

there have been any compensatory damages proven in this

case or out-of-pocket expenses of that nature, but I do

think that an award of $250 in punitive damages will be

in order. It probably takes the wisdom of a Solomon to

decide these cases fairly, but that is the best I can do.

And I think under all the circumstances, I am not going to

award—I know Milwaukee Legal Services is very interested

in establishing the position that they should [211] be en

titled to attorney’s fees in these matters and maybe they

should in the proper case, but considering everything in

this case, I am just not going to award any attorney’s

fees and costs.

Thank you, gentlemen.

Mr. Tucker: If Your Honor please,—

The Court: You may draft an order in accordance with

this opinion.

Mr. Tucker: I was wondering about the costs. You are

not awarding costs?

The Court: No.

Mr. Tucker: Very well, sir.

* # # # #

District Court’s Oral Findings of

Fact and Conclusions of Law

12a

Judgment of District Court

December 7, 1970

This action came on for trial before the Court, Honorable

John W. Reynolds, United States District Judge, presiding,

and the issues having been duly tried and a decision having

been duly rendered,

It is Ordered and A djudged that the plaintiff, Julia

Rogers, recover of the defendants, LeRoy Loether, Mariane

Loether and Mrs. Anthony Perez $250.00 as punitive dam

ages; further ordered, that compensatory-actual damages,

costs and attorney’s fees are hereby denied.

13a

3ftt ti&t

Unite!) S ta te s Court of Appeals!

Jfor tfje is>ebentf) Circuit

Opinion of Court of Appeals

S eptember T erm , 1971 .January Session, 1972

No. 71-1145

J ulia R ogers,

Plaintiff-Appellee,

v.

A p p e a l from the

United States Dis

trict Court for the

Eastern District of

>. Wisconsin.

Leroy L oether and M a b i a h e

L o e t h e r , his w ife and M rs .

A n thony P erez,

Defendcmts-Appellcmts

No. 69-C-524

J ohn W. R eynolds,

Judge.

A rgued F ebruary 22, 1972 — D ecided September 29, 1972

Before S wygert, Chief Judge, S tevens, Circuit Judge,

and Cam pbell, District Judge.*

S tevens, Circuit Judge. The question presented is

whether appellant was entitled to a jury trial in an action

for compensatory and punitive damages brought under

§ 812 of the Civil Rights Act of 1968, 42 U.S.C. $ 3612.* 1

In her complaint, plaintiff alleged that the three de

fendants had refused to rent her an apartment because of

* Senior District Judge William J. Campbell of the Northern District

of Illinois is sitting by designation.

1 Section 812 provides, in part:

“ (a) The rights granted by sections 803, 804, 805, and 806 may

be enforced by civil actions in appropriate United States district

courts without regard to the amount in controversy and in appro

priate State or local courts of general jurisdiction. A civil action

Opinion of Court of Appeals

her race.1 2 She requested injunctive relief restraining de

fendants from renting the apartment to anyone else,

money damages for her actual losses, punitive damages

of $1,000, and attorney’s fees.

The district court, after an extended hearing, entered

a preliminary injunction. Subsequently, with plaintiff’s

consent, the injunction was dissolved; thereafter only

plaintiff’s claims for compensatory and punitive damages

and attorney’s fees remained. Defendants’ request for a

jury trial of those issues was denied. After trial, the court

found that plaintiff had suffered no actual damages but

assessed punitive damages of $250; the prayer for at

torney’s fees was denied.

On appeal defendants contend that the finding of

discrimination is clearly erroneous, that it was error to