LDF Asks Court of Appeals to Act in Behalf of Youth Interrogated by GA Police

Press Release

October 10, 1967

Cite this item

-

Press Releases, Volume 5. LDF Asks Court of Appeals to Act in Behalf of Youth Interrogated by GA Police, 1967. e5ad0921-b892-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/38317838-2eb5-43d9-a33c-9f8cdbfaa186/ldf-asks-court-of-appeals-to-act-in-behalf-of-youth-interrogated-by-ga-police. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

w

N

%

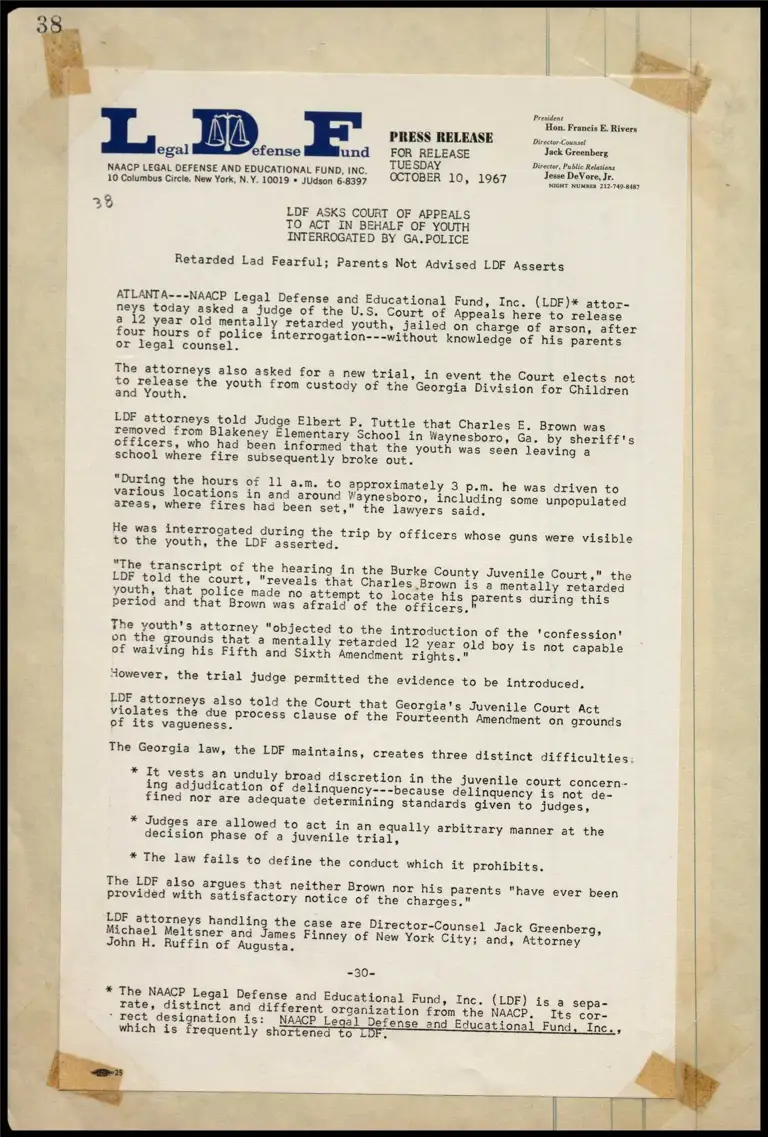

President

Hone Francis E. Rivers aN PRESS RELEASE Director-Counsel

egal efense lund = FOR _RELEASE deck Gromuberg

TUESDAY Director, Public Relations JAACP LEGAL DEFENSE AND EDUCATIONAL FUND, INC. Jesse DeVore, Jr. 10 Columbus Circle, New York, N.Y. 10019 * JUdson 6.8397 OCTOBER 10, 1967 ies HONG Ca 7eeu

LDF ASKS COURT OF APPEALS

TO ACT IN BEHALF OF YOUTH

INTERROGATED BY GA.POLICE

Retarded Lad Fearful; Parents Not Advised LDF Asserts

ATLANTA---NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund, Inc. (LDF)* attor- neys today asked a judge of the U.S. Court of Appeals here to release a 12 year old mentally retarded youth, jailed on charge of arson, after four hours of police interrogation---without knowledge of his parents or legal counsel.

The attorneys also asked for a new trial, in event the Court elects not to release the youth from custody of the Georgia Division for Children and Youth.

LDF attorneys told Judge Elbert P, Tuttle that Charles E. Brown was removed from Blakeney Elementary School in Waynesboro, Ga. by sheriff's officers, who had been informed that the youth was seen leaving a school where fire subsequently broke out.

"During the hours of 11 a.m. to approximately 3 p.m. he was driven to various locations in and around Waynesboro, including some unpopulated areas, where fires had been set," the lawyers said.

He was interrogated during the trip by officers whose guns were visible to the youth, the LDF asserted.

"The transcript of the hearing in the Burke County Juvenile Court," the LDF told the court, "reveals that Charles Brown is a mentally retarded youth, that police made no attempt to locate his parents during this period and that Brown was afraid of the officers,"

The youth's attorney "objected to the introduction of the ‘confession on the grounds that a mentally retarded 12 year old boy is not capable of waiving his Fifth and Sixth Amendment rights."

However, the trial judge permitted the evidence to be introduced,

LDF attorneys also told the Court that Georgia's Juvenile Court Act violates the due process clause of the Fourteenth Amendment on grounds of its vagueness.

The Georgia law, the LDF maintains, creates three distinct difficulties

* It vests an unduly broad discretion in the juvenile court concern- ing adjudication of delinquency---because delinquency is not de- fined nor are adequate determining standards given to judges,

* Judges are allowed to act in an equally arbitrary manner at the decision phase of a juvenile trial,

* The law fails to define the conduct which it prohibits.

The LDF also argues that neither Brown nor his Parents "have ever been provided with satisfactory notice of the charges."

LDF attorneys handling the case are Director-Counsel Jack Greenberg, Michael Meltsner and James Finney of New York City; and, Attorney John H. Ruffin of Augusta.

=30-

* The NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund, Inc. (LDF) is a sepa- rate, distinct and different organization from the NAACP, Its cor- * rect designation is: NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund, Incas which is frequently shortened to DDE.