Goss v. Knoxville, TN Board of Education Brief of the Respondent Board of Education and the Individual Respondents

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1962

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Goss v. Knoxville, TN Board of Education Brief of the Respondent Board of Education and the Individual Respondents, 1962. 1708b0fc-b39a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/384eb0b9-4881-441c-9031-f6cbe3ccc1f0/goss-v-knoxville-tn-board-of-education-brief-of-the-respondent-board-of-education-and-the-individual-respondents. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

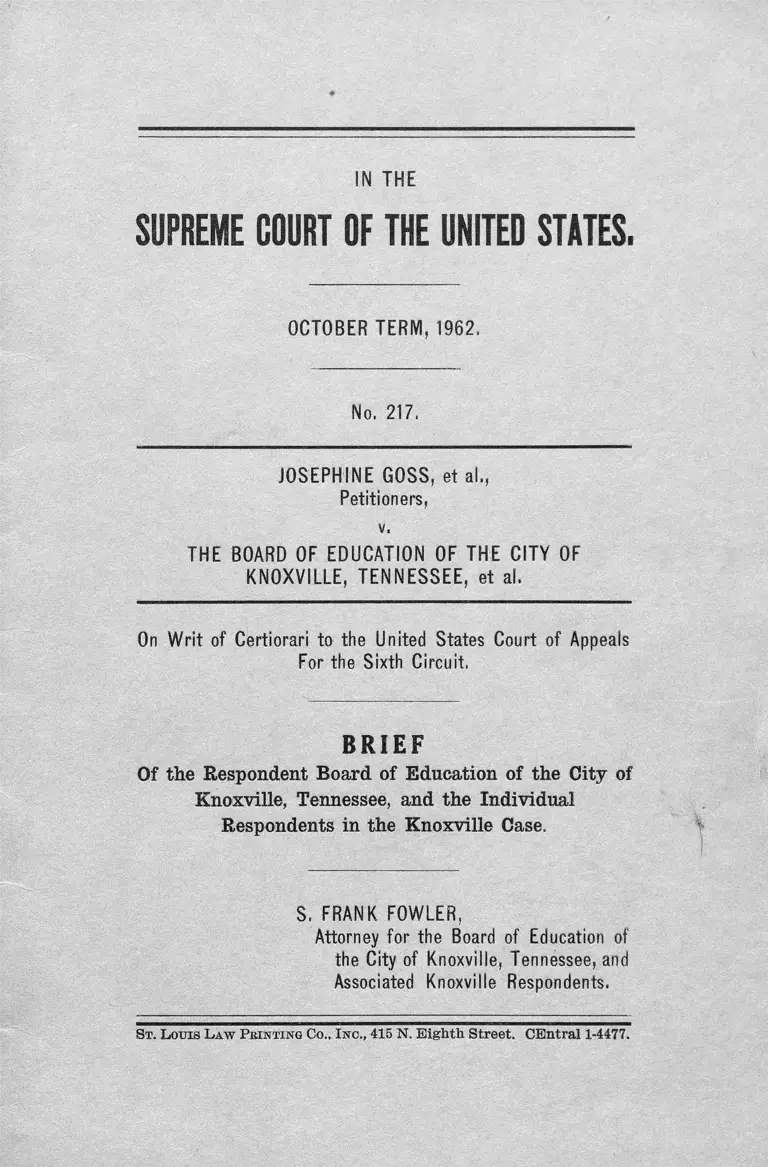

IN THE

SUPREME COURT OF THE UNITED STATES.

OCTOBER TERM, 1962.

No. 217.

JOSEPHINE GOSS, et al.,

Petitioners,

v.

THE BOARD OF EDUCATION OF THE CITY OF

KNOXVILLE, TENNESSEE, et al.

On Writ of Certiorari to the United States Court of Appeals

For the Sixth Circuit,

BRIEF

Of the Respondent Board of Education of the City of

Knoxville, Tennessee, and the Individual

Respondents in the Knoxville Case.

S. FRANK FOWLER,

Attorney for the Board of Education of'

the City of Knoxville, Tennessee, and

Associated Knoxville Respondents.

St . L ouis L aw P rinting Co.. I nc ., 415 N. Eighth Street. CEntral 1-4477.

INDEX.

Pa

Constitutional Provisions Involved .............................

Summary of Argument ...............................................

Argument ......................................................................

Citations.

Kelley v. Bd. of Ed. of the City of Nashville, 270 F. 2d

209 (6th Cir. 1959) ..................................................

McSwain v. Co. Bd. of Ed. of Anderson Co., 138 F. S.

570 (U. S. C. E. D. Tenn 1956) .............................

IN THE

SUPREME COURT OF THE UNITED STATES.

OCTOBER TERM. 1962,

No. 217.

JOSEPHINE GOSS, et a!.,

Petitioners,

v.

THE BOARD OF EDUCATION OF THE CITY OF

KNOXVILLE, TENNESSEE, et ai.

On Writ of Certiorari to the United States Court of Appeals

For the Sixth Circuit.

BR IEF

Of the Respondent Board of Education of the City of

Knoxville, Tennessee, and the Individual

Respondents in the Knoxville Case.

CONSTITUTIONAL PROVISIONS INVOLVED.

This case involves Sections 1 and 5 of the Fourteenth

Amendment to the Constitution of the United States.

— 2 —

SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT.

Local school boards are authorized to take into account

transitional problems of pnblie- stemming from race.

The transfer plan in this case, as interpreted and upheld

by the Court of Appeals, reflects the assumption that in

Knoxville an application for transfer based upon race is

actually based upon the existence of an educational detri

ment or hardship due to race. The record tends to sup

port this assumption.

Respondents believe it to be their duty, even if the chal

lenged transfer provisions are disapproved, to grant trans

fers supported by good cause even though due to racial

considerations.

ARGUMENT.

We are in agreement with the United States as amicus

curiae, in whose brief it is stated:

. . we fully recognize that in some communities,

during the transitional period, measures for accom

plishing desegregation may create individual educa

tional problems, and that it is wise school administra

tion to take such transitional problems of personal

adjustment into account even when they originate in

customs fixed by race.”

(Brief for the United States as amicus curiae, 25.)

The petitioners agree (Petitioners’ Brief, 21-2).

Respondents also agree as stated in Brief for the United

States at page 18 that the provisions of Paragraph 6 of

the Knoxville desegregation plan which specify race as

sufficient ground for transfer are under review here only

as transition measures. As such they may be entitled to

approval where not so entitled if under review as per

manent rules, just as, for instance, the postponement of

desegration in grades not yet reached in an approved step

plan is valid.

Both the Honorable Robert L. Taylor, Judge of the Fed

eral District Court at Knoxville, and the Knoxville School

Board learned early that welfare of Negroes as well as

whites could be seriously jeopardized by imposing the

Brown decisions too speedily upon the community. The

Clinton disorders (R. 48), occurring in a community only

eighteen miles from Knoxville, which resulted from a

direction by Judge Taylor1 to desegregate the high schools

of Anderson County, Tennessee, were referred to in his

1 McSwain v. Co. Bd. of Ed. of Anderson Co., 138 F. S. 570

(U. S. C. E. D. Tenn. 1956).

opinion as revealing “ pockets of hate and lawlessness”

(R. 123) and giving him grave concern (R. 136). The

wisdom and experience of the local authority should not

be overriden in the name of equal treatment, when the

feared result will be a worsened experience for both races,

not only disruptive of education but creating and harden

ing racial animosity and destroying racial tolerance, un

derstanding and mutual trust now undisturbed in Knox

ville for fifty years.

In Knoxville only in rare instances will white parents

permit their children to go to predominantly Negro

schools, and the majority of Negro parents won’t let their

children go to predominantly white schools. Judicial com

mands don’t change these attitudes. Forced compliance

by either Negro or white would be normally regarded as

harmful to the child. Overly rigorous enforcement of the

Brown decision by the courts very likely will do more dam

age than under-enforcement by school boards.

Proof will undoubtedly show that through the years the

Knoxville Board as a matter of course has granted trans

fers upon far less substantial grounds than the least of

the frictions stemming from race.

AVhen the plan of desegregation was under study in the

District courtroom the main controversy was whether the

grade-a-vear feature wa,s justified. The transfer provisions

were merely incidental; they were valid under the holding

that the Kelley ease2 and the challenge to them received

scant attention. The proof, however, which supports a

gradual desegregation also tends to support the transfer

provisions. Moreover, the very fact that an application

for transfer is made upon the ground of race, is some in

dication that actual prejudice to the pupil will follow if

2 Kelley v. Bd. of Ed. of the City of Nashville. 270 F. 2d 209

(6th Cir. 1959).

— 4 —

---- 0

the transfer is denied. The application for transfer is

tantamount to expression of the parents’ opinion that the

child will be at a disadvantage if not transferred and,

through experience, the Board is inclined to agree. In

this state of the record the Court of Appeals in effect held

that inasmuch as the transfer provisions could be prop

erly applied, they were valid but the Board was admon

ished not to use them as a means to perpetuate segrega

tion (R. 162). We interpret this to prohibit transfers

upon -a-:naked ground of race. The result was to uphold

the transfer provisions with leave to the plaintiffs to show

specific instances of abuse, mis-use or misapplication of

the provisions by the Board. The transfer plan simply

reminds the transfer officers that there is an assumption

that requests for transfers based upon race are supported

by actual good cause which stems from race. Respond

ents submit that the validity of this assumption is sus

tained by the common knowledge that practically every

departure from the segregation that has heretofore always

existed in schools in communities such as Knoxville will

embarrass, harm, or otherwise handicap somebody.

If, however, this Honorable Court in the absence of

more specific proof in support of these provisions, should

disapprove them, this action should not be a bar to a

subsequent application by respondents to revive these pro

visions if proof then offered shows that they should be

revived as a transition measure. During such period as

they may be inoperative, and indeed as a permanent pol

icy, the respondent Knoxville Board of Education feels

that it will not be its duty to blind itself to such actual

educational prejudice as may occur, whether to white or

Negro pupils, due to inability to adjust or to be accepted

by fellow pupils or other handicap. In such cases, the

Board of Education will grant application for transfers

where it is reasonable to expect that the applicants therebv

will be helped in obtaining an education, and the Board

will do so even though the pupils’ handicap is attributable

to his race. This is but part of respondents’ objective of

providing as good an education for each child of Knox

ville as they can. So far, they have preserved undis

turbed classrooms and have worked out a genuine ac

ceptance of children of both races in the same classrooms

of the first four grades.

At this time the Knoxville School Board is of the opin

ion that it will be practicable, although it will make their

duties more difficult, to delete from its plan Paragraph 6,

which is the one here attacked, and utilize Paragraph 5

of this plan, which broadly authorizes transfer for “ good

cause” (R. 31-2) to govern all cases, including those of

handicap due to race. This will compel separate investiga

tion of each application for transfer, necessitating employ

ment of additional personnel and expense, but can be done

in this community. Whether this is practicable in other

southern cities with proportionately greater Negro popu

lation is questionable. If not required of them, it should

not be required of Knoxville. The retention of Paragraph

6 will greatly ease the administrative job.

For the foregoing reasons, we respectfully submit that

the transfer provisions of the Knoxville plan of desegre

gation of the public schools should be approved and the

judgment below affirmed.

S. FRANK FOWLER,

Attorney for the Board of Educa

tion of the City of Knoxville,

Tennessee, and Associated

Knoxville Respondents.

— 6 —