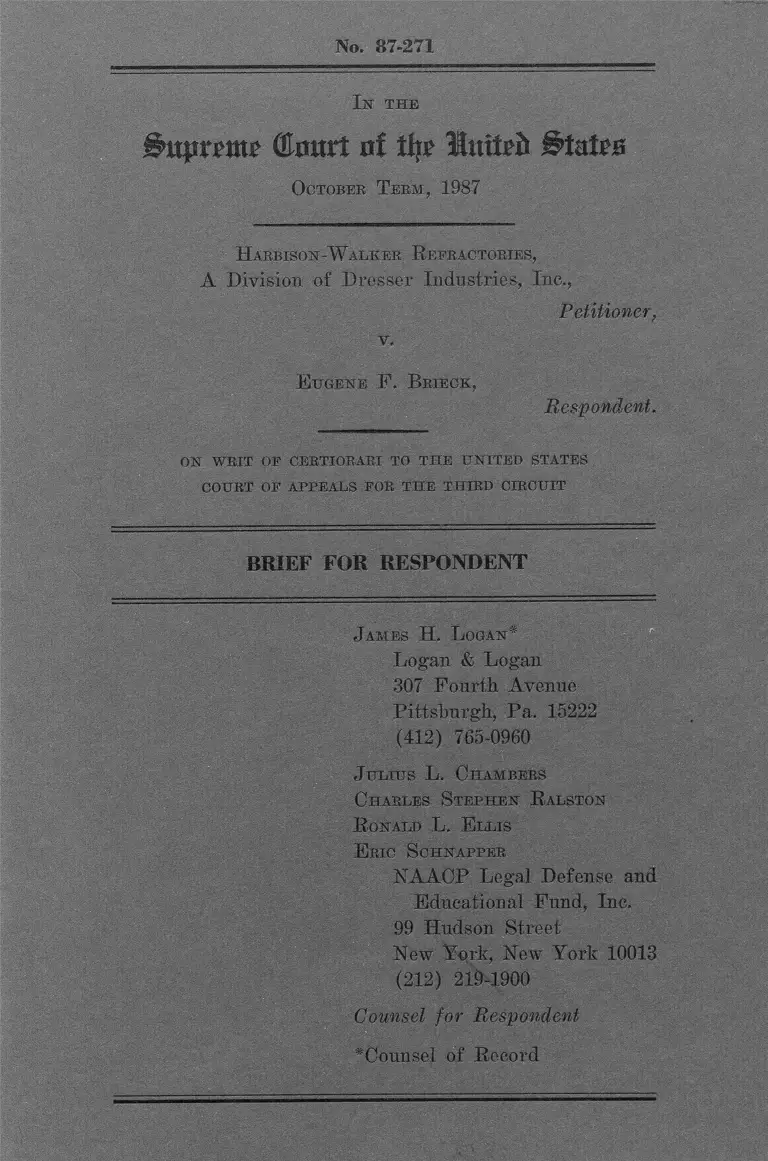

Harbison-Walker Refractories v. Brieck Brief for Respondent

Public Court Documents

June 1, 1988

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Harbison-Walker Refractories v. Brieck Brief for Respondent, 1988. eafad764-b59a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/384fccbe-3666-4e2b-9009-83bff1b9ef1d/harbison-walker-refractories-v-brieck-brief-for-respondent. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

No. 87-271

In THE

d u p re m ? © c u rt X ty Httitei* # tat£ B

October T e em , 1987

H arbison-W alker R efractories,

A Division of Dresser Industries, Inc.,

Petitioner,

v.

E u g en e F. B e ie c k ,

Respondent.

ON WRIT OF CEETIOB.AB1 TO THE UNITED STATES

COURT OF APPEALS FOR THE THIRD CIRCUIT

BRIEF FOR RESPONDENT

J ames H. L ogan*

Logan & Logan

307 Fourth Avenue

Pittsburgh, Pa. 15222

(412) 765-0960

J u l iu s L, Chambers

C harles S t e p h e n R alston

R onald L. E llis

E ric S o hnappeb

IsT A A CP Legal Defense and

Educational Fund, Inc.

99 Hudson Street

New York, New York 10013

(212) 219-1900

Counsel for Respondent

‘̂ Counsel of Record

QUESTION PRESENTED

Does the record in this case present

genuine issues of material fact regarding

r e s p o n d e n t ' s c l a i m of unla w f u l

discrimination?

i

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Page

Question Presented . ........ i

Statutory and Constitutional

Provision Involved ........ 1

Statement of the Case .......... 2

Summary of Argument ............ 9

Argument ..................... . . 12

I . The Record Presents

Genuine Issues of

Material Fact ......... 12

II. The Denial of Summary

Judgment Is Consistent

With Rule 56 and the Age

Discrimination in Employ

ment Act .................. 55

A. The Applicable Legal

Standards ............ 5 6

B. Petitioner's Legal

Arguments ............ 73

C. The Role of Discre

tion in Disposing

of Motions for

Summary Judgment .... 89

Conclusion ......... 100

ii

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

Cases: Page

Adickes v. S.H. Kress & Co.,

398 U.S. 144 (1970) ........ 57,60

Anderson v. Bessemer City,

470 U.S. 564 (1985) 11,65,81

Anderson v. Liberty Lobby,

Inc., 477 U.S. 242 (1986) . 56,83,93

Arnstein v. Porter,

154 F .2d 464 (2d Cir.

1946) 66

Cales v. Chesapeake & Ohio Ry.

Co., 46 F.R.D. 36

(W.D. Va. 1969) 67

Croley v. Matson Navigation

Co., 434 F .2d 73

(5th Cir. 1970) 63

Doehler Metal Furniture Co. v.

United States, 149 F.2d

130 (2d Cir. 1945) 96

Dombrowski v. Eastland,

387 U.S. 82 (1967) ....--- 94

Dyer v. MacDougall, 201 F.2d

265 (2d Cir. 1952) 68

Elliott v. Elliott,

49 F.R.D. 283 (S.D.N.Y.

1970) 96

First National Bank of Arizona

v. Cities Service Co.,

391 U.S. 253 (1968) 60,96

iii

Cases: Page

Furnco Construction Corp. v.

Waters, 438 U.S. 567

(1978) 16

Hutchinson v. Proxmire,

443 U.S. Ill (1979) 12,61,64,71

Kennedy v. Silas Mason Co.,

334 U.S. 249 (1948) 90

Kilgo v. Bowman Transp. Co.

789 F .2d 859 (11th Cir.

1986) .................. . . 32

Nunez v. Superior Oil Co.,

572 F .2d 1119 (5th Cir.

1978) 58

Patterson v. McClean Credit

Union, No. 87-107 ......... 88

Patton v. Yount, 467 U.S. 1025

(1984) 65

Petition of Bloomfield

S. S. Co., 298 F. Supp.

1239 (S.D.N.Y. 1969) ...... 95

Pinson v. Atchison,

T. & S.F.R. Co., 54 F.

464 (W.D. Mo. 1893) 70

Poller v. Columbia

Broadcasting CO., 368 U.S.

464 (1962) 59,61

Sartor v. Arkansas Natural Gas

Corp., 321 U.S. 620

(1944) 67-68

iv

Cases: Page

Schmitz v. St. Regis Paper Co.,

811 F .2d 131 (2d Cir.

1987) 32

Texas Department of Community

Affairs v. Burdine, 450

U.S. 248 (1981) .......... 11,76-79,

82,83,87,88

Untermeyer v. Freund, 37 F. 342

(S.D.N.Y. 1889) 69

U.S. Postal Service Bd. of Govs,

v. Aikens, 460 US. 711

(1983) 64,79,82

Wainwright v. Witt, 469 U.S.

412 (1985) 63,65

Weinberger v. Hynson,

Westcott & Dunning, 412

U.S. 609 (1973) 58-59

White Motor Co. v.

United States, 372 U.S.

253 (1963) 61

RULES:

Rule 11, Federal Rules of

Civil Procedure ........... 57

Rule 50, Federal Rules of

Civil Procedure ........... 9 0

Rule 56, Federal Rules of

Civil Procedure ....... 55,56,72,

85,89,95

V

Page

Federal Civil Judicial

Procedure and Rules

(1987 ed. ) 84

OTHER AUTHORITIES:

29 U.S.C. § 623 (a) (1) 1

Age Discrimination in

Employment Act ............ 1,5,6,7,

55,75

Seventh Amendment,

United States Constitution. 2,59,

60,97

F. James and G., Hazard, Civil

Procedure (2d ed. 1977) ... 57,69

Moore1s Federal Practice

(1988) 93,94

C. Wright, A. Miller and

M. Kane, Federal Practice

and Procedure (1983) .. 57,62,67,70,

90,93,94,96

vi

No. 87-271

IN THE

SUPREME COURT OF THE UNITED STATES

October Term, 1987

HARBISON-WALKER REFRACTORIES,

A Division of Dresser Industries,

Inc. ,

Petitioner.

v.

EUGENE F. BRIECK,

Respondent.

On Writ of Certiorari to the United States

Court of Appeals for the Third Circuit

BRIEF FOR RESPONDENT

STATUTE AND CONSTITUTIONAL

____PROVISION INVOLVED

S e c t i o n 4 ( a ) (1) of the Age

Discrimination in Employment Act of 1967,

29 U.S.C. § 623(a)(1) provides in

pertinent part

2

It shall be unlawful for an

employer ... to fail or refuse

to hire or to discharge any

i n d i v i d u a l or o t h e r w i s e

d i s c r i m i n a t e a g a inst any

individual with respect to his

compensation, terms, conditions,

or privileges of employment,

because of such individual's

age....

The Seventh Amendment to the United States

Constitution provides:

In suits at common law, where

the value in controversy shall

exceed twenty dollars, the right

to trial by jury shall be

preserved, and no fact tried by

a jury, shall be otherwise re

examined in any Court of the

United States, than according to

the rules of the common law.

STATEMENT OF THE CASE

The petitioner in this case is a

manufacturer of specialized ceramic brick

products which are sold primarily to steel

producers. From 1965 until the early

summer of 1982 respondent Eugene Brieck

was employed by the firm as an

installation specialist. In July of 1982,

faced with a substantial decline in its

3

sales, Harbison-Walker began to reduce the

workforce in the Iron and Steel Marketing

Group in which respondent worked.

Although Brieck, then aged 55, was the

most senior installation specialist, and

one of the more senior members of the

entire group, he was the very first

employee laid off. (Pet. App. 17a-18a;

J.A. 31, 33) Brieck had 17 years of

e x p e r i e n c e as a an installation

specialist, compared to only 3 years of

experience, some or all of it devoted to

on the job training, for H.L. Faust, the

youngest installation specialist. (J.A.

33, 50, 152-54) During July, 1982,

Harbison-Walker laid off 7 of the group’s

3 3 employees, including 3 of the 5

employees who were then 55 or older.

Among the company's installation

specialists, all of the employees over 40

— the age group protected by ADEA — were

4

laid off in July. (J.A. 31-33). The

remaining installation specialist, H. J.

Faust, then 39, was retained until

November of 1982; in the summer of 1983

Faust was recalled to a permanent position

as an installation specialist. (J.A. 135,

159) Harbison-Walker never offered either

that or any other position to respondent

after he was laid off.

On July 19, 1982, respondent filed

with the Pennsylvania Human Relations

Commission an administrative charge

alleging that he had been laid off because

of his age. (J.A. 6). On June 29, 1984,

Brieck brought this action against

Harbison-Walker,1 alleging that the

1 Brieck also asserted a state law

claim for breach of contract and for

intentional infliction of emotional

distress. (Complaint, 21-33). The

Third Circuit upheld the dismissal of

those claims (Pet. App. 17a-20a), and

respondent did not seek review of that

dismissal by this Court.

5

company had terminated and failed to

recall him because of his age, in

violation of the ADEA, and requesting a

jury trial. (J.A. 2-7). After discovery

was completed, the company filed a motion

for summary judgment. The company did

not, of course, deny that there was a

dispute regarding whether it had engaged

in intentional discrimination, or that

that dispute was material to Brieck's ADEA

claim; it contended, however, that the

dispute regarding this material fact was

not "genuine" because there was no

evidence to support Brieck's allegation.

Brieck opposed this motion. Both

petitioner and respondent relied in the

district court on depositions that had

been taken, and documents which had been

produced during the course of discovery,

as well as on affidavits submitted in

connection with the disputed motion.

6

The district court granted the motion

for summary judgment on December 19, 1985.

(Pet. App. 12a-21a) . The district judge

did not purport to find that no reasonable

jury could return a verdict for Brieck,

and did not refer to the fact that a jury

trial had been requested. Rather, the

judge apparently proceeded on the

assumption that, if the subsidiary facts

were clear, the court's responsibility was

to decide what inferences ought to be

drawn from those facts, and thus to itself

dispose the case on the merits. In

granting summary judgment regarding

Brieck's ADEA claim, the district judge

wrote:

Any question about ... how Faust

spends his time edges into an

area of scrutiny of business

decisions, which is not part of

our function. We ... consider

it plausible that the importance

of an employee's related

experience, whether or not

applied, increases under the

scaled-down business operations

7

which in fact existed. Without

considering age, we find that

Mr. Brieck, in comparison to

Faust, has

1. slightly more seniority;

2. slightly poorer performance

evaluations;

3. little experience in areas

[un]related to installation

specialist.

We thus cannot find that age was

a determinative factor in the

decision to lav off Mr. Brieck.

Other facts support this

finding.2

̂ Pet. App. 17a. (emphasis added)

The district court's treatment of Brieck's

state law claims reflected this same

approach. In rejecting Brieck's breach of

contract claim, the court explained:

" V i e w i n g d [e f e n ] d a n t ' s

statements most favorably to

plaintiffs, they do not

e s t a b l i s h violation of a

contract.... We find [Brieck's]

evidence insufficient to satisfy

the requirement for a provision

setting the length of the

contract.... Mr. Brieck ... has

not established the form of a

contract which supports his

claim."

(Pet. App.l8a-19a) (emphasis added). The

district court's discussion of the claim

8

The third circuit correctly criticized the

district judge for having undertaken to

decide what inferences should be drawn

from the evidence (Pet. App. 5a-6a), and

petitioner does not in this Court rely on

the trial judge's "findings". On October

2, 1986, the third circuit reversed the

award of summary judgment, and remanded

the ADEA claim for trial; one member of

the appellate panel dissented from the

of Mr. Brieck and his wife for tortious

infliction of emotional distress is

similar in tone:

" f W ]e f ind that defendant's

conduct in no way rises to the

l e v e l of o u t r a g e o u s n e s s

necessary to invoke these

theories.... fWle conclude that

the plaintiff clearly has not

shown that defendant's conduct

meets the test of extremeness

required by this theory. Our

finding necessarily precludes

Mrs. Brieck's claim of negligent

infliction of emotional distress

based on defendant's same

actions."

(Pet. App. 19a-20a)

decision to permit a trial of the ADEA

claim.3 (Pet. App. la-lla)

SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT

This appeal presents a classic case

of the type of sharply conflicting

evidence which must be evaluated by the

ultimate trier of fact, and ’which cannot

be resolved by means of summary judgment

9

3 Judge Weiss' dissenting opinion

is based on a number of material

misunderstandings regarding the evidence

in this case. Judge Weiss believed Brieck

was the second installation specialist to

be laid off (Pet. App. 8a); in fact Brieck

was the first. (J.A. 33) Judge Weiss

assumed that, when Faust was rehired,

another over-40 installation specialist,

E.G. Malarich, was still interested in the

position, and was the more likely victim

of any age discrimination (Pet. App. 9a);

in fact Malarich had by then taken early

retirement. (J.A. 123-25) Most

importantly, Judge Weiss thought Faust had

testified that he spent 75% of his time,

after being recalled, on installation

work, with the remaining 25% devoted to

non-installation tasks (Pet. App. 10a); in

fact Faust testified that he spent "at

least" 75% of his time doing installation

work on the road, and that much of his

remaining time was devoted to installation

related work, such as filling out reports,

back at the office. (J.A. 160).

10

for either party. Petitioner's brief

cogently depicts the evidence and

inferences most favorable to the employer,

but omits mention of most of the at least

equally persuasive evidence adduced by the

respondent. A more thorough review of the

depositions, affidavits and documents

reveals stark and plainly material

conflicts in the evidence regarding the

qualifications of respondent, the

circumstances under which he was laid off,

and the qualifications and experience of

the younger worker who was retained in his

stead. The record also indicates that

company officials have over the years

offered widely varying explanations of

their decision to lay off respondent, a

discrepancy which a trier of fact might

fairly regard as probative evidence of

discrimination.

11

Petitioner insists it is entitled to

summary judgment because it adduced sworn

statements by company executives insisting

that they acted with no unlawful motive in

deciding to lay off respondent. But Texas

Department of Community Affairs v,

Burdine. 450 U.S. 248 (1981), makes clear

that a finder of fact may reject such

protestations of innocence if it finds

them "unworthy of credence." 450 U.S. at

256. Questions of credibility cannot be

resolved on summary judgment, but must be

determined by the trier of fact after

observing the demeanor of the witness

during direct and cross-examination. See

Anderson v. Bessemer City. 470 U.S.564,

575 (1985) . A dispute about a claim of

intentional discrimination, like any

question regarding the state of mind of an

individual, "does not readily lend itself

12

to summary disposition." Hutchinson v,

Proxmire. 443 U.S. Ill, 120 n. 9 (1979).

This case was ready for trial in the

summer of 1985. Instead of a trial that

would have lasted no more than a few days,

over three years have been consumed

debating the strength and nuances of the

evidence. The efficient administration of

justice would have been far better served

in this case if the district court had

exercised its discretion to defer passing

on petitioner's challenge to the

sufficiency of the evidence until a jury

had returned a verdict in the case.

ARGUMENT

I. THE RECORD PRESENTS GENUINE ISSUES OF

MATERIAL FACT

This appeal presents a classic

example of the type of conflicting

evidence and inferences which must be

referred for resolution by a jury or other

trier of fact. If the instant controversy

13

had been tried on the merits, and were

somehow before this Court for de novo

reconsideration, it would fairly be

regarded as presenting a close case. As

we set out in detail below, the record in

this proceeding contains not only evidence

supporting quite inconsistent inferences,

but also square conflicts in the testimony

regarding several material issues;

reasonable persons might well disagree as

to how those conflicts ought to be

resolved. Had this case been tried before

a jury, and a verdict returned in favor of

the petitioner, we would be hard pressed

to overturn such a verdict on appeal; the

record undeniably contains substantial

evidence supporting the contentions of the

petitioner, and petitioner's brief

cogently summarizes those portions of that

record most favorable to it and sets forth

with considerable force the inferences

14

that might conceivably have been drawn

from those selected portions of the

record.

In the present procedural posture of

this case, however, the issue is not

whether a jury verdict in favor of

petitioner could be sustained on appeal,

but whether a jury should be permitted to

consider the merits of the underlying

controversy. Petitioner describes the

record in this case in terms which, if

accurate, might well support an order of

summary judgment. Thus petitioner asserts

that the critical facts were either

"undisputed"^ or " c o n c e d e d , a n d

repeatedly insists that respondent had

literally adduced "no" evidence whatever

4

5

Pet. Br. 6, 15 n. 8, 23 n. 15.

Pet. Br. 6, 16.

15

of an unlawful discriminatory motive.6

The actual record before the Court, we * 11

Pet. Br. i (respondent failed to

present "any evidence, direct or indirect,

that his employer's judgment was in fact

motivated by an intent to discriminate"),

6 ("Respondent failed to produce any

evidence that the Company's proffered

business reasons were a pretext for age

discrimination"), "8 ("respondent ...

produced no evidence — other than the age

differential between him and Faust—

linking the company's decision to age"),

11 ("Respondent offered no evidence that

age played ... a role in the decision), 11

("plaintiff has produced no direct or

indirect evidence of age discrimination),"

16 ("Respondent produced no direct

evidence that Harbison-Walker's decision

was motivated by age discrimination. Nor

did he present any indirect evidence..."),

17 ("Respondent presented no specific

facts, beyond the fact that the laid-off

installation specialists were older than

Faust, to demonstrate that the company's

articulated reasons were pretextual"), 18

("Respondent failed completely to forge

any link between the challenged decision

and age discrimination") , 21 ("complete

absence of record evidence to support a

finding of age discrimination"), 23

("Respondent's complete failure to adduce

evidence concerning the essential element

of his case — discrimination on the basis

of age...."), 24 (respondent lacked any

"factual support for his case").

16

suggest, cannot fairly support this

characterization.

In the instant case, as in Furnco

Construction Coro, v Waters. 438 U.S. 567,

569 (1978), "[a] few facts ... are not in

dispute." For some 17 years prior to

June, 1982, respondent was an employee of

petitioner Harbison-Walker, a diversified

company whose activities include the

manufacturing and sale of ceramic brick

for use in industrial furnaces.

Throughout this period respondent held the

position of installation specialist; as of

the spring of 1982 there were a total of

four i n s t a l l a t i o n specialists in

petitioner's Pittsburgh office, respondent

(age 55) , W. L. Meixell (59) , A1 Malarich

(59), and Hugh Faust (39).7 (J.A. 31, 33)

Some portions of the record

describe the position held by Meixell not

as installation specialist but as "senior

installation specialist." Defendant's

Response to Plaintiff's First Set of

17

Brieck was laid off by petitioner on July

2, 1982; petitioner subsequently laid off

Meixell (July 9, 1982), Malarich (July 30,

1982), and last of all, Faust (November

18, 1982). (J . A. 33). The next year

Faust was rehired8 as a permanent

employee, which he evidently remains to

this day. (J.A. 149). Petitioner

c o n c e d e d that it had given no

consideration to rehiring respondent when

the 1983 vacancy, ultimately awarded to

Interrogatories Directed to Defendant,

Appendix A. If Meixell held a position

different and indeed higher than Faust,

the decision to retain Faust and lay off

Meixell might well be interpreted by a

jury as evidence of a practice of age

discrimination.

Technically laid off employees

were on temporary furlough for the first

nine months after leaving the company,

after which the furlough became permanent.

(J.A. 113-14) . It is unclear from the

record whether this nine month period had

lapsed when Faust returned to work. At

least one other laid off employee, aged

22, was recalled after the expiration of

this nine month period. (J.A. 33, 114).

18

Faust, arose. (J.A. 125) The central

issue in this case, is whether petitioner

acted with an intent to discriminate

against respondent because of his age

when, in July of 1982, it laid off

respondent while keeping Faust on the job,

or in August of 1983, when it rehired

Faust rather than respondent.

(A) The d e c i s i o n s be l o w and

petitioner understandably focus much of

their discussion on the reasons given by

the company for deciding to retain and

rehire Faust rather than respondent. In

its brief in this Court petitioner now

asserts that Faust was selected because he

had as of 1982-83 more diversified

experience and training. (Pet. Br. 4, 5).

The record reveals, however, that company

officials have over the course of this

controversy given widely varying accounts

19

of the basis on which the disputed

decisions were made.

The earliest explanation of the

criterion for selecting employees for

layoff came from Ralph Ytterberg, Senior

Vice President of Dresser Industries,

petitioner's parent company, in a company

newsletter dated "Spring 1982". Ytterberg

announced that "Length of company service

and skill requirements . . . are the most

important considerations". (J.A. 47).

Ytterberg's statement is important because

it evidently predates the decision to

dismiss respondent. Although there is

considerable dispute in this case

regarding what skills were needed in

respondent's unit after June of 1982, and

regarding what skills respondent and Faust

in fact possessed, there is no dispute

that respondent had more company seniority

20

than any of the other installation

s p e c i a l i s t s , i n c l u d i n g F a u s t . 9

Respondent's supervisor, Larry

Sheatsley, stated in his deposition that

Faust had been retained over Meixell on

the basis of seniority (J.A. 105), but all

of the company managers questioned

conceded that, despite Ytterberg's

announcement, respondent's greater

seniority had not been considered when he

was laid off instead of Faust. John

Nicolella, Harbison-Walker's manager of

employee relations, asked to explain why

the company had retained Faust rather than

respondent, asserted that Faust had

greater seniority than respondent (J.A.

9 The seniority dates of the

installation specialists were as follows:

Brieck June 1965

Malarich August 1966

Faust September 1966

Meixell January 1980

J.A. 33.

21

132), a statement which petitioner now

acknowledges was incorrect. (Pet. Br. 3) .

Sheatsley asserted that he premised his

choice between petitioner and Faust on the

assumption that they had "about the same

years service with Harbison" (J.A. 105), a

statement which a jury might find

inconsistent with the 15 month difference

in seniority, or with Ytterberg's

announcement that seniority was an

important consideration. Sheatsley's

deposition testimony that he was aware of

the seniority of each of the four

installation specialists was seemingly

contradicted by respondent's deposition

which recounted that, in the course of

telling Brieck he was being laid off,

Sheatsley had professed surprise at

learning that Brieck had more seniority

than Faust. (J.A. 79). Finally,

petitioner offered in support of its

22

motion for summary judgment an affidavit

of W i l l i a m S e k e r a s , S h e a t s l e y 1s

supervisor, which contained his own

account of the directions given to

Sheatsley for selecting the employees to

be laid off; the Sekeras affidavit

contains no reference whatever to

seniority as a consideration (J.A. 13) ,

which seems less than fully consistent

with Ytterberg's earlier announcement, or

with the reasons given by Sheatsley for

laying off Meixell rather than Faust.

On June 17, 1982, when the decision

to lay off respondent had been made, at

least tentatively, but had not yet been

announced, company executive F. P.

S h o n k w i l e r addressed an internal

memorandum to Nicolella explaining that

respondent had been chosen for layoff

because he was "our least qualified

Installation Specialist and has limited

23

expertise". (J.A. 145). The most

noteworthy fact about this contemporaneous

internal explanation is what it does not

contain, viz. any suggestion that the

choice had been based on respondent's

comparative ability to perform functions

other than those of an installation

specialist. In this Court, of course,

petitioner offers a rather different

explanation, insisting that the decision

to lay off respondent rather than Faust

was based on the need for an employee who

could work on noninstallation tasks. Were

the company still sticking with the

explanation given by Shonkwiler in 1982,

this case would certainly have to be

referred by a jury, for there are direct

and unequivocal conflicts in the testimony

regarding the comparative skills of

respondent and Faust as installation

specialists. (See section 1(B), infra).

24

The next occasion when the reasons

for respondent's layoff were discussed was

on July 2, 1982, when Sheatsley informed

respondent that he was being furloughed.

Respondent testified at his deposition

that he had asked why he had been selected

for layoff, and was given a seemingly

evasive response:

I says, "why me?"

He says, "we got to start

somewhere"

* * *

Then I asked him about these

young kids. I said, "What about

all these young kids?" And he

just wouldn't say nothing, he

just sort of shrugged his

shoulders ... [T]he younger kids

. . . there was a dozen of them

with less than maybe a year's

service, if that much.

(J.A. 81; see also id. at 85) . A jury

might plausibly infer from Sheatsley's

silence that he had as of June, 1982, no

legitimate explanation to offer, and that

the explanation which he gave in his 1985

25

deposition had been concocted in the

interim. On the other hand r both

Sheatsley and another supervisor in the

room during this exchange stated in their

depositions that they could not recall

what questions respondent had asked, or

what answers Sheatsley had given,

regarding how the company had decided to

lay off respondent rather than Faust or

others. (J.A. 108, 122-23).10

xu Three days after he was laid

off, respondent spoke by phone with the

president of Harbison-Walker, Don Stocks,

and directly complained that he had been

laid off while far younger, and

necessarily less senior, employees were

retained:

"A. I ... says, You are keeping all

these kids, and your[sic]

neglecting me.

"Q. And what did he say to that?

"A. He says, I can't interfere with

the process." He says, "I am

sorry. Goody[sic]."

(J.A. 83) . A jury might have construed

Stock's statement merely as a refusal to

become involved in personnel matters, or

26

Respondent's objection to the

retention of younger, less senior workers

was aired again later in 1982 at a meeting

at the office of the Pennsylvania Human

Relations Commission, attended by

respondent and by John Nicolella, the

firm's personnel director. At his

subsequent deposition respondent recounted

that the following exchange had occurred

at that meeting between himself and

Nicolella:

[A ]t that meeting, I asked

[Nicolella], "John," I says,

"Why are you keeping these kids

and getting rid of me?"

He says, "Gene, these kids are

going to be our future

managers." And that's all he

said.

(J.A. 83). Nicolella's remark could

conceivably be construed in more than one

way; but a jury might plausibly interpret

as a deliberately evasive response to an

inquiry for which he knew there was no

legitimate response.

27

his statement as expressing a preference

for retaining younger employees who,

unlike workers such as respondent in their

fifties, would still be with the company

many years in the future.

There were seeming inconsistencies in

the statements made by company officials

regarding whether differences in the

performance ratings of respondent and

Faust had played a role in the critical

decision. Nicolella flatly asserted that

ratings differences had "come into play."

(J.A. 133, 134). Sheatsley, who was

responsible for the initial recommendation

to lay off respondent rather than Faust,

made no reference whatever to having

considered ratings, but based his

explanation solely on alleged differences

in the experiences of respondent and Faust

outside the area of installation work.

(J.A. 105-06). Sheatsley's, supervisor,

28

William Sekeras, submitted a deposition

taking an intermediate or possibly

equivocal position, asserting that

diversity of experience was " [t]he

principal reason underlying Faust's

retention", but then adding, "Also, Faust

had slightly higher performance ratings

than Brieck". (J.A. 14-15). Nicolella

asserted in his 1985 deposition that "Mr.

Faust is rated higher than Mr. Brieck"

(J.A. 133); but the 1982 memorandum on the

basis of which Nicolella approved

respondent's layoff asserted that he and

Faust had the same rating. (J.A. 147-48).

Malarich undeniably had a higher rating

than Faust (J.A. 148) , but none of the

Harbison-Walker executives offered any

account of why this had not helped

Malarich when he was laid off, and Faust

retained, several weeks after respondent

lost his job.

29

Finally, in his July, 1985, affidavit

Sekeras offered an entirely new

explanation of the retention of Faust

rather than Brieck, asserting that Faust

had a unique expertise regarding a

particular important type of brick

installation:

Faust was the only installation

specialist who had experience in

installation work in blast

furnace casthouses, an area that

had been targeted by Harbison-

Walker as a growth market and an

a r e a t h a t r e p r e s e n t e d

significant potential even

during the 1982 period.

(J.A. 14). Had this explanation been

offered in June or July 1982, when Brieck

was first laid off, it might well have

carried considerable weight, and it is of

course possible that a jury might yet

credit it at trial. But the timing of

this new explanation might well lead a

jury to a very different conclusion. At

his March 1985 deposition Larry Sheatsley,

30

who initially selected Brieck for layoff,

although repeatedly asked why Faust was

retained, made no reference whatever to

blast furnace casthouses, either as an

area of differing expertise or as having

any importance to the company. (J.A. 104-

06, 111-12) . Similarly Harbison-Walker's

personnel manager, John Nicolella, was

repeatedly asked at his, May 1985

deposition, the reasons for Faust's

retention, and he too made no reference to

blast furnace casthouses. (J.A. 131-32).

Only in July of 1985, after the completion

of discovery, did the company produce a

witness to offer this new explanation.

We do not contend that any rational

jury would necessarily see in these ever-

shifting explanations decisive proof of

invidious discrimination. It is at least

conceivable that counsel for the company

could persuade a jury that these apparent

31

inconsistencies were merely the result of

a series of misunderstandings — that

Sheatsley, Sekeras, Nicolella and

Shonkwiler simply had completely different

reasons for arriving coincidentally at the

same conclusion that Brieck should be laid

off, that Sheatsley and Nicolella made a

bona fide mistake in not realizing that

Brieck had more seniority than Faust, and

that Nicolella never read Shonkwiler's

memorandum of June 17, 1982. But surely a

reasonable jury could draw from these

divergent accounts a very different

conclusion, that Brieck was in fact

selected for lay off because of his age,

and that from 1982 to 1985 Harbison-

Walker's supervisors concocted a series of

explanations in search of a purported

32

j u s t i f i c a t i o n with a p atina of

plausibility.11

(B) Varying testimony about the

reasons for laying off respondent rather

than Faust would be sufficient to defeat

the motion for summary judgment, even if

there were no dispute about differences in

the qualifications of respondent and

Faust. In fact, however, such disputes

abound, and in most instances are the

result of direct conflicts in the

evidence •

In his 1985 deposition Sekeras

asserted that the ratings of Faust and

Brieck were as follows: *

1J- The lower courts have repeatedly

r e c o g n i z e d that such a shifting

explanation of an employer's conduct is

probative evidence of the existence of a

discriminatory motive. Schmitz v. St.

Regis Paper Co. . 811 F.2d 131, 133 (2d

Cir. 1987) ; Kilgo v. Bowman Transp. Co.,

789 F .2d 859, 875 (11th Cir. 1986).

33

Brieck Faust

1981 3 31980 2 31979 2 31978 3 4

(J.A. 15). Under the Harbison-Walker

rating system a " 3 " means "fully

satisfactory". (J.A. 133, 161). Brieck* s

supervisor during the years from 1978 to

1981, however, testified he never rated

Brieck lower than fully satisfactory (J.A.

120), seemingly contradicting the 1979 and

1980 ratings in Sekeras* affidavit. The

Sekeras' affidavit contains no ratings for

1982; an internal memorandum of that year,

however, reveals that Brieck and Faust

received the same rating in 1982. (J.A.

135, 146). The only uncontradicted

difference in ratings is for 1978, some

four years before the layoffs in question,

a gap in time that seems inconsistent with

the tense of Nicolella's 1985 deposition

statement that "Mr. Faust is rated higher

34

than Mr. Brieck." (J.A. 133) (emphasis

added). In addition, Faust testified that

he did not become an installation

specialist until 1978 or 1979 (J.A. 152-

53), which suggests that his 1978 rating

of "4" was in all probability a rating for

a job different than that which was at

issue in the 1982 layoffs.12 Even Sekeras

asserted only that there were differences

in ratings in 1980 and earlier years (J.A.

15); the contemporaneous June, 1982,

memorandum discussing the decision to lay

off Brieck rather than Faust, however,

cited only their 1981 and 1982 ratings,

suggesting that older possibly unequal

ratings were not considered when the 1982

12 The relevance of such out-of-

date ratings to the 1982 layoff decisions

is further called into question by the

fact that, only a few months before he was

laid off, Brieck had been awarded a raise

and a letter of commendation. (J.A. 4,

51, 75) . The company offered no evidence

that Faust's work had been lauded or

rewarded in this manner.

35

decision was made. (J.A. 146). in

August, 1982, in a written explanation of

the decision to retain Faust, the company

asserted to the Pennsylvania Human Rights

Commission that Faust "has been rated very

good to fully satisfactory in the last

three years."13 That assertion is flatly

contradicted by the Sheatsley deposition

and the company's internal memorandum of

June 1982, which indicate that Faust had

not received a "very good" (4) rating in

any of the four prior years.

There was also a clear conflict in

the evidence regarding Faust's comparative

ability, indeed his competence, to do the

work of an installation specialist, which

remained the bulk of his duties both in

1982 and after he was rehired in 1983.

Sekeras, of course, asserted in his

Deposition Exhibit 7, Deposition

of John Nicolella.

36

affidavit that only Faust had experience

with blast furnace casthouses. (J.A. 14).

Brieck, on the other hand, asserted in his

deposition that Faust was little more than

a trainee who had never worked on an

installation job on his own, but always

did so in the company of one of the other

installation specialists. (J.A. 68-69?

see also id. at 52). If Brieck was

correct, S e k e r a s 1 a f f i d a v i t was

necessarily wrong, for Faust could not

have had unique experience regarding

casthouses or anything else if all his

installation experience had been acquired

in concert with another specialist.

Indeed, Brieck's account, if credited by a

jury, would strongly suggest that Faust

was the least competent employee to do the

specialist work which remained the core of

his position. Brieck's deposition, on the

other hand, was directly contradicted by

37

Faust, who stated in his deposition that

he had been sent out on his own. (J.A.

155). Faust's deposition testimony

regarding his experience with casthouse

installations was somewhat opaque,

apparently referring only to the period

after the July 1982 layoffs, and not

explaining clearly what work he had done

in this area. (J.A. 150).

There was conflicting evidence, as

well, regarding Brieck's experience and

abilities. In an affidavit submitted in

response to the motion for summary

judgment, Brieck asserted he was the only

one of the four installation specialists

who had ever worked on international

assignments,14 which constituted an

important segment of the firm's business.

14 J.A. 51 ("I was the only one of

the four installation specialists in the

Iron and Steel Marketing Group who had

been sent out on inter n a t i o n a l

installation assignments").

38

(J.A. 18) . On the other hand, Sheatsley

asserted in his deposition that others had

worked overseas, although it is somewhat

unclear whether Sheatsley was referring to

other installation specialists, and there

is no suggestion that Faust had ever

worked on overseas projects-15 Nicollela

asserted that Faust was retained rather

than his older colleagues because those

other installation specialists, Brieck

included, could not do any thing except

"just supervise the installation of brick

in a steel mill". (J.A. 132). Nicollela's

contentions were sguarely disputed by

-LD J.A. 102:

"Q: Were other individuals sent

on Overseas' assignments, or was it most

likely Mr. Brieck who would be doing that

in terms of the Installation Specialists

in the Iron & Steel Market?

"A: I'll say I'm aware that

others were sent on installation

assignments Overseas besides Mr. Brieck.

Specifically who and when, I'd have to go

back and check."

39

Brieck's affidavit and deposition, which

asserted that Brieck had extensive

experience in preparing reports and

surveys (J.A. 52, 62), technical drawings

(J.A. 52, 63) and marketing analyses (J.A.

63), in analyzing technical problems which

customers were experiencing with their

furnaces (J.A. 60, 63), in designing the

masonry interiors of blast furnaces (J.A.

61), and in pricing and sales. (J.A. 52,

58) .

There was similar disagreements about

the nature of Faust's experience outside

the area of installation. Sekeras and

Sheatsley broadly characterized Faust's

office work as administrative. (J.A. 15,

105). Faust's deposition, however,

suggested that, aside from preparing

certain essentially clerical calculations

and correspondence, his position was that

of "gofer":

40

A. I usually do a lot of things

that people just tell me to do.

Like a car needs fixed, got

something out at advertising

that we need. Whatever. Even

drove a forklift down the

warehouse one time.

Q. So if somebody had to go for

something, you might have to do

that?

A. Not have to, I would be asked

nicely to do it. I would

volunteer.

Q. Excuse me for degrading your

role, but would part of your job

be to be a gofer?

A. Sure. I don't mind doing that.

It's something different.

Q. I'm not saying anything bad

about it, but part of your job

was to be the officer handyman?

A. Yeah. That was part of being

staff correspondent.

(J .A. 156-57). Sekeras asserted Faust had

had "considerable contact in customer

relations" (J.A. 14) , and in this Court

petitioner describes Faust's experience as

"marketing" and "sales". (Pet. Br. 6, 7,

23) . In his deposition, however, Faust

41

conceded that his work as an "assistant

correspondent" was largely limited to

processing written orders:

Q. Were you involved in sales at

all or was your job more or less

to support the sales staff?

A. Support the sales staff, but I

did have direct contact with

customers. On the phone. Phone

contact.

Q. What percentage of your time was

spent in the office when you

were a correspondent?

A. One hundred percent....

Q. Had you ever been involved in

sales in any respect during your

employment with Harbison-

Walker?

A. No, but we feel like we are a

part of sales. Staff support.

Q. You support the sales, but you

yourself were never performing

an actual sales function

yourself?

A. No....

(J.A. 152-55) . In a September 1982

response to a request for information from

the P e n n s y l v a n i a Human Relations

Commission, petitioner asserted that

Faust's job duties included helping to

"make engineering sketches and technical

preparation and proposals." (J.A. 147).16

In his deposition Brieck squarely asserted

that Faust neither did nor had the ability

to do any technical work or sketches (J.A.

68-69), and Faust's description of his own

experience at Harbison-Walker makes no

mention of any such experience or ability.

(J.A. 149-60).

There is no dispute that Faust's

experience at Harbison-Walker included two

positions which Brieck never held—

assistant sales correspondent and staff

correspondent. (J.A. 151-53). What is

16 In a letter to the Commission

dated August 2, 1982, the company

explained that it had retained Faust

because he possessed "multidisciplinary

skills in engineering." Deposition

Exhibit No. 7, Deposition of John

Nicolella. This explanation also seems

inconsistent with the depositions of Faust

and Brieck.

42

43

very much at issue, and far from clear

from the present record, is what Faust

actually did in those positions.

Petitioner suggests that Faust was a

marketing expert and administrator, with

refined skills and broad experiences,

while Brieck was merely a bricklayer.

While the record is not utterly devoid of

evidence to buttress that contention, the

record seems on balance to provide greater

support for a very different conclusion,

that Faust was little more than a

glorified gofer, less than fully qualified

even to do the work of an installation

specialist, and possessed only of

rudimentary office skills which a person

of ordinary ability could master in a few

days. (J.A. 52-53, 68, 149-60).

(C) There are a number of important

areas in which the underlying facts are-

undisputed, but regarding which very

44

different inferences could reasonably be

drawn. Petitioner offered in support of

its motion a statistical analysis

purporting to demonstrate that it could

not have acted with any discriminatory

motive. That analysis indicates that

among the Marketing Group employees 40 and

over only 21% were laid off, compared to

47% of the employees under 40.17 However,

if one examines the comparative treatment

of the oldest employees a different

picture emerges; in July of 1982

petitioner laid off 60% of the employees

x/ J .A. 31-33. Petitioner laid off

3 of 14 employees 40 and over, and 9 of

the 19 employees under 40. For reasons

which are not apparent on the face of the

record, the list of laid-off employees

annexed to the July, 1985, affidavit of

Sekeras contains less than half the names

set forth in a list of laid-off employees

provided by the company in January, 1985.

Defendant’s Response to Plaintiff's First

Set of Interrogatories Directed to

Defendant, Appendices A and B. The

analysis in this note and the accompanying

text is based on the lists attached to the

Sekeras affidavit.

45

55 and older, but only 14% of the

employees under 55.18 In either event the

sample size is small, and the evidentiary

weight of the statistics thus limited, but

a jury might plausibly draw from the

underlying data either of two very

different conclusions.

The fact that almost half of the

employees laid off in July, 1982, were

over 55, in a unit where only 15% of the

workers were that old, was a result of

Harbison-Walker's decision to concentrate

the initial layoffs on installation

specialists, the position in which most of

its oldest workers were to be found. Thus

in the July layoffs the company furloughed

3 of the 4 installation specialists, but

only 1 of the 7 product specialists. A

reasonable jury could draw different

18 Id. Petitioner laid off in

July 3 of the 5 employees 55 and over, and

only 4 of the 28 employees under 55.

46

conclusions from the record regarding why

this occurred. Sheatsley suggested that

the decline in the need for employees was

particularly great in the case of

installation specialists,19 a statement

which, if credited by a jury, could

provide a legitimate explanation for the

disproportionately large number of

installation specialists laid off. On the

other hand, immediately after 2 of the 4

installation specialists, aged 55 and 59,

were laid off, Sekeras announced that

there was now a shortage of installation

specialists and that other employees would

as a consequence have to do installation

work.20 Sheatsley acknowledged that,

J.A. 105 ("assistance in the

installation of our refractories was

definitely less needed, that was a prime

consideration").

J.A. 118 ("The heaviest impact

was in our Marketing Support Group

which will seriously reduce our capability

from Pittsburgh to follow installations

47

after the older installation specialists

were laid off, it became necessary to

direct almost all the other employees in

the Marketing Support Group to do

installation work.2-*- a reasonable jury * 21

.... Sales people will be required to ...

follow installations as required.... I

... expect each of you to take additional

roles and responsibilities to help fill

the gaps.... This means you may be

required to ... even follow installa

tions ....")

21 J.A. 110:

"Q. Of those 32 that remained after

the temporary furlough of the

first 6, how many of those 32

actually, in fact, helped in

doing Installation Specialist

work in the months after then?

"A. I wouldn't be able to say

specifically, but the majority

or nearly all or perhaps all of

the remaining non-clerical

personnel with the possible

exception of Don Jamison and

myself. So the various Product

Managers, the various Product

Specialists and Product Analysts

would have all contributed in

this installation service area.

"Q. They would actually go on the

job site?

48

might infer from this evidence that the

decision to concentrate the layoffs on

installation specialists was the result,

not of a particularly severe decline in

installation work, but of some entirely

extraneous consideration, such as a desire

to remove employees in their fifties.

The decision to retain Faust alone

from among the installation specialists

was explained by Sekeras as being a result

of the need for someone with Faust's

experience as a sales correspondent.

(J.A. 14). Yet on August 2, 1982, only 3

days after Harbison-Walker had laid off

the last of the installation specialists

over 40, the company laid off the only

sales correspondent in the unit. (J.A.

33) . A jury might well infer from that

action that the skills of a sales

'!A. Correct."

49

correspondent were not in fact needed by

the company at all.

Sekeras insisted that Faust was

retained and rehired, rather than Brieck,

because Faust's "administration and sales

correspondent experience permitted him to

perform other noninstallation functions in

the reduced department". (J.A. 15). The

company's entire argument necessarily

rests on the premise, at least implicit in

Sekeras' statement, that company officials

in fact beli e v e d that whichever

installation specialist was retained, and

later rehired, would in fact be performing

a significant amount of "noninstallation

functions". Faust's deposition, however,

revealed that in fact he spent virtually

all of his time on installation work.

When asked what he did in July 1982, Faust

50

mentioned only installation work,22 and

Faust acknowledged that since being

rehired in 1983 he had spent almost all

his time on installation activities.23

J .A . 149-50:

"Q. Could you describe for me what

your duties were in July of

1982"

"A. I was assigned to the — I was

in the ir o n a nd s t e e l

department. I was assigned to

work with Stan Pavlica on blast

f u r n a c e p r o j e c t s a n d

installations....

"Q. What were your duties when you

worked with Mr. Pavlica?

"A. I went out on blast furnace

installations."

23 J .A . 160:

"Q. Since coming back in August of

*83, what has been the

percentage of time you would

spend on the job -- on the road

as an installation specialist?

"A. 75, I guess, at least.

"Q. When you were involved in duties

t h a t a r e n ' t a c t u a l

installations, what duties do

you perform now, or what duties

51

have you performed from August

of '83 to the present date that

have not been installation

duties?

"A. Pretty much been related to that

-- I write reports of the

installation. Have to have time

to come into the office to do

that. I've also still done some

work with the blast furnace

group working on margins again.

Doing some filing. Not much

anymore. It's just piling up.

But I still -

"Q. You do work with the blast

furnace group?

"A. Right.

"Q. You do filing, and what was the

other thing you said?

"A. Margins. Also some gofer work

like getting drawings out to the

works, to salesmen.

"Q. When you write reports of

installations, any installation

specialist would have to do

that?

"A. Yes.

"Q. Even someone like Mr. Brieck— -

someone like Mr. Brieck in his

old duties would have had to

fill out reports regarding

52

As the third circuit properly

recognized, Faust's description of his

actual duties "raise a question of fact as

to whether the employer really believed

that Faust's 'varied' experience made him

more qualified than Brieck to perform the

job functions remaining in the reduced

business environment." (Pet. App. 5a).

The company offered in support of its

motion for summary judgment no evidence

purporting to explain this apparent

discrepancy between the concerns which

allegedly led it to retain and rehire

Faust, and the work which Faust actually

performed. In its brief in this Court the

installations he had been

involved in?

"A. Correct....

"Q. What percentage of your time

since August of '83 has been

spent doing margins? Very small

percentage?

"A. Small percentages [sic], yes."

53

company seems to suggest that the

discrepancy was merely the result of an

innocent error, that the company officials

believed in good faith, albeit mistakenly,

that the employee in the position in which

Faust was retained, and subsequently

rehired, would be spending a large portion

of his time on noninstallation work

requiring the past experience of a sales

correspondent. (Pet. Br. 20, 23). A jury

could conceivably interpret the evidence

in that way, but it would surely be

reasonable for a jury to infer from what

Faust actually did after the July, 1982,

layoff that the real reason for the

decisions to retain and rehire Faust was

s o m e t h i n g other than his sales

correspondent experience.

The instant case, in sum, is a

classic example of the type of dispute

which cannot be resolved, for either

54

party, by summary judgment, but must be

submitted for resolution by the trier of

fact, be it a judge or a jury. Genuine

disputes about material facts are not

merely present, they abound. This is not

merely a situation in which a trial is

required to resolve conflicts between the

statements of the plaintiff and those of

the defendant's officials; here a trial is

necessary to resolve the conflicts among

the statements of the company officials

themselves. As petitioner's brief well

illustrates, a jury which believed only

the evidence, and drew only the

inferences, most favorable to the company,

might return a verdict for Harbison-

Walker. But the contention on which

petitioner's demand for summary judgment

is grounded — that "viewing 'the record

as a whole' ... no 'rational trier of fact

[could] find for [Respondent]' on his age

55

discrimination claim," (Pet. Br. 23-24)

— simply cannot be sustained.

III. THE DENIAL OF SUMMARY JUDGMENT IS

CONSISTENT WITH RULE 56 AND THE AGE

DISCRIMINATION IN EMPLOYMENT ACT

In view of the actual state of the

record in this case, it is abundantly

clear that summary judgment could not

properly be awarded to petitioner.

Proceeding on the basis of its assertion

that this is a case in which there is

literally no evidence of unlawful

discrimination, petitioner argues that the

decision of the third circuit must be

based on some misconception as to the

applicable legal principles. In light of

the actual record, the legal issues

briefed by petitioner do not appear to be

presented by this case. Nonetheless, we

set forth below the general principles

applicable to a motion for summary

56

judgment, and then address briefly the

specific arguments advanced by petitioner.

A. The Applicable Legal Standard

(i) Rule 56(c) of the Federal Rules

of Civil Procedure authorizes the entry of

summary judgment in a civil case if

the pleadings, depositions,

answers to interrogatories, and

admissions on file, together

with the affidavits, if any,

show that there is no genuine

issue as to any material fact

and that the moving party is

entitled to a judgment as a

matter of law.

"[A]t the summary judgment stage the

judge's function is not himself to weigh

the evidence and determine the truth of

the matter but to determine whether there

is a genuine issue for trial." Anderson

v. Liberty Lobby, Inc.. 477 U.S. 242, 249

(1986).

If ... the proofs fail to

exclude all bases on which

judgment might be rendered in

favor of the person against whom

the motion is made, summary

judgment must be denied. And

57

this would be true whether the

issue is one of disputed fact or

a question of how the trier

would characterize admitted

facts (e.g. as constituting

negligence or the reverse). The

device is not intended to

resolve issues that are within

the traditional province of the

trier of fact, but rather to see

whether there are such issues.

F. James and G. Hazard, Civil Procedure.

273 (2d ed. 1977) (footnotes omitted).

The burden of persuasion is on the moving

party, and that burden is a stringent one;

any doubts as to the existence of a

genuine issue for trial must be resolved

against the party seeking summary

judgment. Adickes v. S. H. Kress & Co,.

398 U.S. 144, 158-59 (1970).24 It may be

24 One authoritative commentator

suggests that the procedures established

by Rule 56 have in some instances been

abused. 10 C. Wright, A. Miller and M.

Kane, Federal Practice and Procedure §

2712, pp. 582-83 (1983). A motion for

summary judgment, like any other motion,

must be based on a reasoned belief that it

is well grounded in fact and warranted by

existing law. See Rule 11, F.R.C.P.

58

of considerable importance whether a given

case, if it went to trial, would be heard

by a judge or a jury.

If the decision is to be reached

by the court, and there are no

issues of witness credibility,

the court may conclude on the

basis of the affidavits,

depositions, and stipulations

before it, that there are no

genuine issues of material fact,

even though decision may depend

on inferences to be drawn from

what has been incontrovertibly

proved.... But where a jury is

called for, the litigants are

entitled to have the jury draw

those inferences or conclusions

that are appropriate grist for

juries.

Nunez v. Superior Oil Co.. 572 F.2d 1119,

1123-24 (5th Cir. 1978).

A motion for summary judgment also

raises issues of a constitutional nature

where, as here, the non-moving party has

requested and would be entitled to have

his claims resolved by a jury if the case

went to trial. This Court's decision in

Weinberger v. Hvnson, Westcott & Dunning.

59

412 U.S. 609 (1973),25 suggests that a

different and more stringent standard

should be applied where the effect of

summary judgment would be to deny the jury

trial requested by the non-moving party;

at the least particularly great caution

ought be exercised in deciding to grant

summary judgment in such a case. Trial by

deposition, like »[t]rial by affidavit is

no substitute for trial by jury which so

long has been the hallmark of 'even handed

justice. ' " Poller v. C o l u m b i a

Broadcasting C o . , 368 U.S. 464, 473

(1962) .

The right to confront, cross-

examine and impeach adverse

witnesses is one of the most

fundamental rights sought to be

p r e s e r v e d by the Seventh

Amendment provision for jury

trials in civil cases. The

"If this were a case involving

trial by jury as provided in the Seventh

Amendment, there would be sharper

limitations on the use of summary

judgment." 412 U.S. at 621-22.

60

advantage of trial before a

live jury with live witnesses,

and all the possibilities of

considering the human factors,

should not be eliminated by

substituting trial by affidavit

and the sterile bareness of

summary judgment.

Adickes v. S. H. Kress & Co.. 398 U.S.

144, 176 (1970) (Black, J. concurring)26

If on a motion for summary judgment the

moving party clearly establishes that it

would be entitled to a directed verdict if

the case went to trial, the court may,

consistent with the Seventh Amendment,

award judgment. But a court asked to

grant summary judgment in a case that

would otherwise be referred for a trial to

a jury must bear in mind the stringent

constitutional restrictions on the

2e> In his dissenting opinion in

First National Bank of Arizona v. Cities

Service Co. , 391 U.S. 253, 304 (1968),

Justice Black expressed concern that "the

summary judgment technique tempts judges

to take over the jury trial of cases, thus

depriving parties of their constitutional

right to trial by jury".

61

authority of judges to impinge on the

factfinding authority of juries, and be

alert to any possibility that the record

that would be presented at trial might

differ from the record on which summary

judgment is sought.

(ii) This Court admonished in

Hutchinson v. Proxmire. 443 U.S. Ill, 120

n. 9 (1979), that a question regarding the

state of mind of an individual "does not

r e a d i l y lend itself to summary

disposition."27 That unavoidable

27 See also White Motor Co. v.

United States. 372 U.S. 253, 259 (1963)

("[sjummary judgments ... are not

appropriate 'where motive and intent play

leading roles'"); Poller v. Columbia

Broadcasting System. 368 U.S. 464, 473

(1962) ("We believe that summary judgment

procedures should be used sparingly in

complex antitrust litigation where motive

and intent play leading roles, the proof

is largely in the hands of the alleged

conspirators, and hostile witnesses

thicken the plot") (footnote omitted).

The holding in Hutchinson is consistent

with the practical judgment of the lower

courts, which have repeatedly found

summary judgment inappropriate in cases

62

limitation on the utility of summary

judgment procedures arises for two

distinct reasons. First, where the

individual whose state of mind is at issue

is still alive, and there is reason to

believe that either party will call him to

testify at trial, uncertainties about the

demeanor and credibility of that witness

will ordinarily preclude the granting of

summary judgment. Because such a witness

is the only person with personal knowledge

of his or her own state of mind, a trier

of fact is likely to rely very heavily on

the credibility of that witness'

testimony.

[A] court should be cautious in

granting a motion for summary

judgment when resolution of the

dispositive issue requires a

determination of state of mind.

involving a dispute about the knowledge or

state of mind of an individual. 1QA C.

Wright, A. Miller & M. Kane, Federal

Practice and Procedure. § 2730 (1983)

(citing cases).

63

Much depends on the credibility

of the witnesses testifying as

to their own states of mind. In

these circumstances the jury

should be given an opportunity

to observe the demeanor, during

direct and cross examination, of

the witnesses whose states of

mind are at issue.

Croley v. Matson Navigation Co.. 434 F.2d

73, 77 (5th Cir. 1970). "[TJhe manner of

the [witness] while testifying is often

times more indicative of the real

character of his opinion than his words."

Wainwright v. Witt. 469 U.S. 412, 428 n.

9 (1985). The certainty that no one else

could directly contradict his testimony

may lead such a witness to exaggerate or

misrepresent his state of mind; if the

witness is a party, or connected with a

party to the proceeding, the dangers of

relying on his statements at the summary

judgment stage are particularly great.

Second, disputes regarding the state

of mind of an individual frequently depend

64

on indirect and circumstantial evidence

about whose significance reasonable people

may well disagree. "[T]he question facing

triers of fact in discrimination cases is

both sensitive and difficult.... There

will seldom be 'eyewitness' testimony as

to the employer's mental process." U. S ,

Postal Service Bd. of Govs, v. Aikens, 460

U.S. 711, 716 (1983). Where the

difficulty in resolving a factual question

is especially great, the possibility that

a court will be able to conclude that

there is no genuine issue about the proper

resolution of that question is likely to

be particularly small.

The a d m o n i t i o n in Hutchinson

exemplifies the broader problem that

arises whenever summary judgment is sought

in a case to which the demeanor of a

witness might be relevant, or even

critical. In any case of that sort a

65

judge asked to rule on a motion for

summary judgment will ordinarily have no

way of knowing the nature of the demeanor

evidence that would be presented at

trial.28 The judge's avoidable ignorance

regarding that evidence will not

invariably be fatal to a motion for

summary judgment. The existence of

necessarily unknowable demeanor evidence,

like the existence of unexamined

documentary evidence, would bar the entry

of summary judgment only if the nature of

that evidence could alter the outcome of

that case. There could, of course, be a

case in which "cross examination of the

This limitation is analogous to

the posture of an appellate court asked to

review a cold record to determine the

sufficiency of the evidence to support a

decision made, at least in part, on the

basis of demeanor. See Anderson v.

Bessemer City. 470 U.S. 564, 575 (1985);

Wainwright v. Witt, 469 U.S. 412, 428

(1985); Patton v. Yount. 467 U.S. 1025,

1038 and n. 14 (1984).

66

[deponent or affiant] ... would be

futile." Arnstein v. Porter. 154 F.2d

464, 470-71 (2d Cir. 1946). If in a

wrongful death action, for example, the

defendant both asserted that it had a

witness who had seen the alleged decedent

alive and well long after his purported

death, and then actually produced the

alleged decedent in court during the

hearing on its motion for summary

judgment, the plaintiff could not of

course avoid the granting of the motion by

insisting that cross-examination at trial

might convince the trier of fact that the

defense witness was lying.

There will, on the other hand, be

cases in which the necessary absence of

demeanor evidence will preclude the

granting of a motion for summary judgment.

"Where ... credibility is, or may be

crucial, summary judgment becomes improper

67

and a trial indispensable." Gales v.

Chesapeake & Ohio Rv, Co. . 46 F.R.D. 36,

40 (W.D. Va. 1969).29 If the moving party

offers affidavits or depositions from

w i t n e s s e s whose t r u t h f u l n e s s or

reliability are disputed by the opposing

party, the court at the summary judgment

stage will not be able to rely on the

statements of those witnesses. "[T]he

mere fact that the witness is interested

in the result of the suit is deemed

sufficient to require the credibility of

his testimony to be submitted to the jury

as a question of fact." Sartor v.

The 1963 Advisory Committee

note to Rule 56 observes:

Where an issue as to a material

fact cannot be resolved without

observation of the demeanor of

witnesses in order to evaluate

their credibility, summary

judgment is not appropriate.

10 A C. Wright, A. Miller & M. Kane,

Federal Practice and Procedure. § 2726, p.

115 (1983); see generally id. at 113-21.

68

Arkansas Natural Gas Corp., 321 U.S. 620,

628 (1944). Where witnesses with personal

knowledge of one or more critical facts

offer statements in support of the motion,

the court must consider the possibility

that the demeanor evidence might convince

the trier of fact, that the witnesses were

unreliable, or even that their statements

were the opposite of the truth.30 A

deponent or affiant, if called to testify

in open court, might "convince all who

30 A witness1 bearing on the stand

may convince a jury

"not only that the witness'

testimony is not true, but that

the truth is the opposite of his

story; for the denial of one,

who has motive to deny, may be

uttered with such hesitation,

discomfort, a r r o g a n c e or

defiance, as to give assurance

that he is fabricating, and

that, if he is, there is no

alternative but to assume the

truth of what he denies."

Dver v. MacDouaall. 201 F.2d 265, 269 (2d

Cir. 1952) .

69

hear him testify that he is disingenuous

and untruthful, and yet his testimony,

when read, may convey a most favorable

impression." Untermeyer v. Freund. 37 F.

342, 343 (S.D.N.Y. 1889). The court must

bear in mind as well that cross-

examination of a witness at a deposition

may not be the equivalent of cross-

examination at trial, both because the

circumstances of a trial, including the

presence of a judge or jury, might make a

witness more forthcoming,31 and because

x F. James and G. Hazard, Civil

Procedure. 275 (2d ed. 1977):

"There may be a chance that

persons who are willing to

p e r j u r e themselves in an

affidavit and even in the

informal atmosphere of a

deposition may be impelled by

the formal trappings of trial

and the personal presence of the

judge to tell the truth. When

summary judgment is granted,

this chance is lost.... The

strongest case for affording

this ... chance probably exists

where all the facts are within

70

the non-moving party may be in a better

position to examine the witness at trial

in light of additional evidence that was

discovered only after the original

deposition, or which emerged only during

the trial itself.* 32

the exclusive knowledge of the

movant."

Pinson v. Atchison, T. & S.F.R. Co.. 54 F.

464, 465 (W.D. Mo. 1893):

"It is sometimes difficult and

impossible to get so full,

explicit and perspicuous a

statement from the witness

through a deposition as it is by

his examination before court and

j ury."

32 10A C. Wright, G. Miller & M.

Kane, Federal Practice and Procedure, §

2727, pp. 120-21 (1983)

"[W]hen the knowledge of the

events or occurrences on which

the action is based lies

exclusively within the control

of the party moving for summary

judgment . . . most commonly in

actions in which the main issue

involves the movant's state of

mind ... [cjourts have been

r e l u c t a n t to deprive the

n o n m o v i n g p a r t y of the

71

The history of racial discrimination

l i t i g a t i o n well i l l u s t r a t e s the

correctness of the admonition in

Hutchinson v. Proxmire. Over the course

of the last three decades there have been

literally thousands of federal court,

state court, legislative and judicial

f i n d i n g s of i n t e n t i o n a l racial

discrimination. Yet in a great many of

these instances the perpetrator, or one or

more of its employees or agents, offered

sworn testimony that no such invidious

motives were involved. So far as we are

aware there is not a single instance in

opportunity of testing the

credibility of the movant or his

witnesses in open court....

'there is a justifiable judicial

fear of the injustice which

could result from judgment based

on affidavits asserting facts

that are, because of their

nature, incapable of being

effectively controverted.'"

(footnotes omitted).

72

which any one of these witnesses was

prosecuted for perjury, although it seems

difficult to avoid the conclusion that

much of this testimony was not truthful.

We do not, of course, suggest that perjury

prosecutions ought to become a regular