Geison v. Alabama Brief for Appellant

Public Court Documents

April 21, 1967

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Geison v. Alabama Brief for Appellant, 1967. 20b61010-b39a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/3861a487-ef1f-47ce-a16b-8eac434b52a7/geison-v-alabama-brief-for-appellant. Accessed February 07, 2026.

Copied!

S7

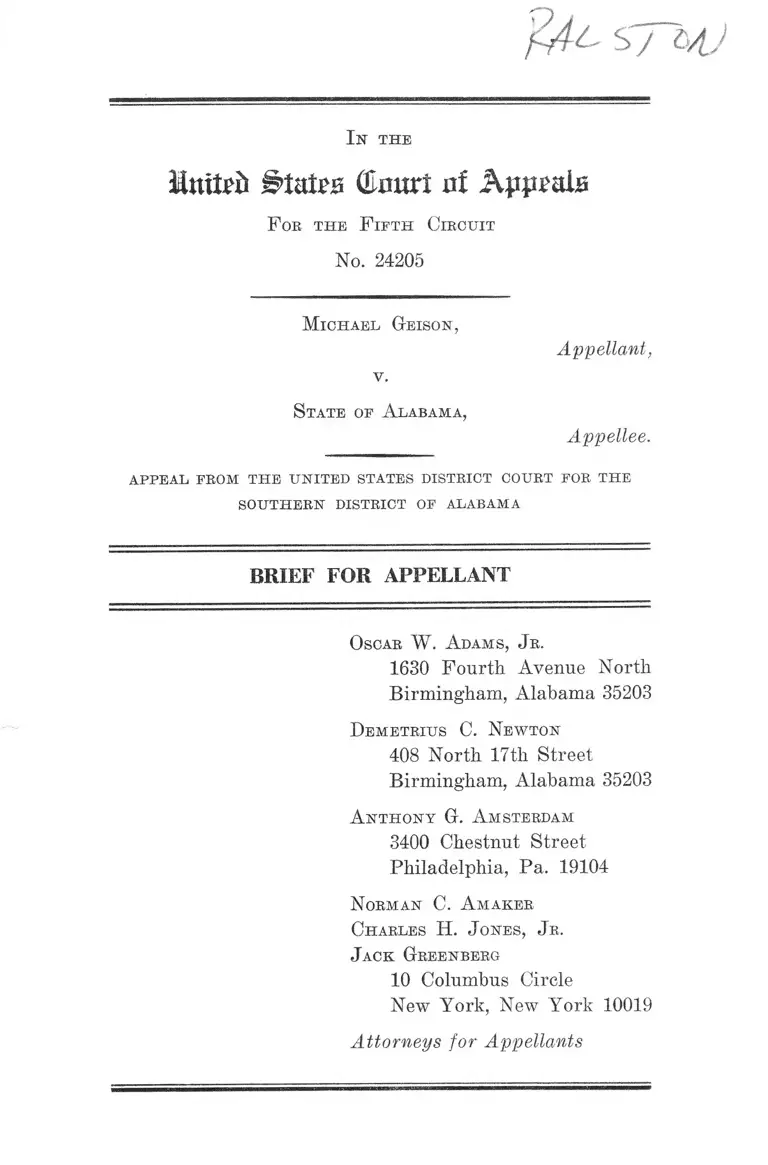

I n the

Mmtpd States (Emtrt nf Appeals

F oe the F ifth Circuit

No. 24205

Michael Geison,

Appellant,

v.

State of A labama,

Appellee.

appeal from the united states district court for the

S O U T H E R N D IST R IC T OF ALABAMA

BRIEF FOR APPELLANT

Oscar W. Adams, J r.

1630 Fourth Avenue North

Birmingham, Alabama 35203

Demetrius C. Newton

408 North 17th Street

Birmingham, Alabama 35203

A nthony G. A msterdam

3400 Chestnut Street

Philadelphia, Pa. 19104

Norman C. A maker

Charles H. J ones, J r.

J ack Greenberg

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

Attorneys for Appellants

TABLE OF CONTENTS

PAGE

Statement of the Case .................................................. 1

Specification of Error .................................................. 2

A rgument—

28 U.S.C. §1443(1) Authtorizes Removal of a

Contempt Prosecution Brought to Enforce Racial

Segregation in a State Courtroom .................... 3

Conclusion ............................................................................... 8

Statutory A ppendix ................ l a

T able op Cases

City of Greenwood v. Peacock, 384 U.S. 808 (1966)

2, 3,4, 5, 6,7

Georgia v. Rachel, 384 U.S. 780 (1966) ..........2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 8

Hamm v. The City of Rock Hill, 379 U.S. 306 .......... 6

I n the

BUUb (Burnt at Appeals

F oe the F ifth Circuit

No. 24205

Michael Geison,

v.

Appellant,

State of Alabama,

Appellee.

appeal fkom the united states district court fob the

S O U T H E R N D IST R IC T OF ALABAMA

BRIEF FOR APPELLANT

Statement of the Case

Appellant, Michael Geison, a white citizen of the State

of Florida, was employed during 1965 as a staff worker

for the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (S.C.

L.C.) in Hale County, Alabama, and other black-belt coun

ties in the state. His activities revolved around the de

velopment of what was known as the Hale County Voter

Registration Project. In Hale County, he addressed meet

ings and assemblies of persons interested in registering to

vote. He accompanied persons desirous of registering to

vote to the appropriate registration places and partici

pated in peaceful demonstrations to bring about equal op

portunity to register to vote and to vote (R. 1, 2).

Appellant alleged in his removal petition that while en

gaged in voter registration activities he was arrested and

2

incarcerated in Camp Selma a state prison located in

Dallas County, Alabama (R. 3). While incarcerated, addi

tional charges were placed against him and he was re

leased, pending trial in the County Court of Dallas County,

after posting a $500.00 bond on each charge (R. 3).

Appellant’s petition, filed in the United States District

Court for the Southern District of Alabama, also asserted

that “when [he] came for trial on these charges in the

County Court, he was held in contempt of court for refus

ing to remove himself from a so-called white side of the

courtroom to the Negro side, although he was a white per

son” (R. 3). He further alleged that the charge was re

movable under 28 U.S.C. §1443 (R. 1) because federal

statutory and constitutional equal rights were being denied

and [the denial was] unenforceable in the courts of the

State of Alabama (R. 5).

Since these allegations were uncontroverted they must

be taken as true for the purpose of determining jurisdic

tion as alleged.

District Judge Thomas, without conducting any hearing

on appellant’s allegations, remanded the petition on his

own motion, October 4, 1966, relying upon City of Green

wood v. Peacock, 384 U.S. 808 (1966), and Georgia v.

Rachel, 384 U.S. 780 (1966) (R. 8). Appellant sought a

stay of the remand order pending appeal, asserting that

the Rachel and Peacock cases supported his removal claim

(R. 10), but the District Court denied the motion (R. 12,

13). Appellant then filed a timely notice of appeal to this

Court from the remand order of October 4, 1966 (R. 9).

Specification of Error

The District Court erred in remanding appellant’s re

moval petition, which stated a valid claim for removal

under 28 U.S.C. §1443, and should have conducted a hear

ing to determine the validity of the allegations contained

therein.

A R G U M E N T

28 U.S.C. §1443(1) Authorizes Removal of a Con

tempt Prosecution Brought to Enforce Racial Segre

gation in a State Courtroom.

Does appellant Geison’s removal petition state a valid

claim for removal under §1443(1) within the principles

of Georgia v. Rachel, 384 U.S. 780 (1966), and City of

Greenwood v. Peacock, 384 U.S. 808 (1966)? Appellant

contends that his refusal to submit to a state judge’s

order enforcing courtroom segregation is specifically pro

tected by 42 U.S.C. §1981 (1964), which statute, in addi

tion, immunizes his conduct against prosecution and makes

the contempt charge removable under Georgia v. Rachel,

supra.

In Rachel, the Supreme Court of the United States

sustained removal under 28 U.S.C. §1443(1) of state

trespass prosecutions brought against Negroes asserting

rights to nondiscriminatory service in places of public

accommodation. Rachel held that the two conditions gov

erning removal under §1443(1) had been met:1 (1) be

cause Title II of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 (78 Stat.

243, 42 U.S.C. §2000a (1964), et seq.) (set forth in the

statutory appendix, infra, p. la) is a specific federal

equal civil rights statute conferring a right to service

1 The Court states at 384 U.S. p. 788: “Section 1443(1) entitled the

defendants to remove these prosecutions to the federal court only if they

meet both requirements of that subsection. They must show both that

the right upon which they rely is a “right under any law providing for

equal civil rights,” and that they are “denied or cannot enforce” that

right in the courts of Georgia.”

4

in a place of public accommodation without racial dis

crimination, rights asserted under it are within the mean

ing of the phrase “any law providing for . . . equal civil

rights” to which Congress intended to extend §1443’s

protection (384 U.S. at 792); (2) the “denied or cannot

enforce” requirement is satisfied by 42 U.S.C. §2000a-2

(1964) (Appendix, infra, pp. la, 2a), because it expressly

forbids punishment of persons engaging in conduct cov

ered by §2000a. Since persons seeking nondiscriminatory

service in places of public accommodation have an ab

solute right to insist upon service without being subjected

to punishment, or state prosecution for such conduct,

§2000a-2, in effect, substitutes “a right for a crime” (384

U.S. at p. 805). Rachel concluded that the mere pendency

of a state prosecution would enable a Federal court to

predict that defendants engaging in conduct protected

by the Act will be denied or unable to enforce in the

courts of the state their absolute right to be free of any

attempt to punish them for the protected activity.

In City of Greenwood v. Peacock, supra, on the other

hand, the Supreme Court disallowed removal of prosecu

tions brought against two groups of civil rights demon

strators who engaged in drives to encourage Negro voter

registration and who were protesting against racial segre

gation in Mississippi. Distinguishing Rachel, the Court,

in Peacock, was unable to find a specific federal law which

either conferred an absolute right to engage in the activity

alleged or provided immunity from prosecution com

parable to §20Q0a-2(c)’s prohibition against punishment.

Appellant contends that §1981, both by its historic pur

pose and its design, supplies the ingredients for removal

lacking in Peacock and present in Rachel by being a

specific federal law authorizing conduct for which it pro

vides an immunity from state prosecution.

5

On April 9, 1866, Congress enacted the first major civil

rights act.2 Its third section, the progenitor of the present

§1443, provided for removal of civil and criminal eases

affecting persons denied “any of the rights secured to

them by the first section of [the] Act; . . . Section 1

of the 1866 Act,3 the progenitor of present §1981, granted

citizens the specific rights, among others, to the “full and

equal benefit of all laws and proceeding for the security

of person and property” as was enjoyed by white citizens,

and particularly the right “to sue, be parties, and give

evidence” in the same manner enjoyed by white citizens.

Section 1981, thus, was clearly a grant of that kind of

specific civil rights “couched in terms of equality” em

braced by Rachel (see p. 792) and was designed to pro

tect the very right appellant Geison asserts-—the right to

nondiscriminatory treatment in a state courtroom. It is

therefore no accident that the Court in Peacock recog

nized that §1981 is one of the sources of “law providing

for . . . equal civil rights” whose violation in the state

courts supports removal. City of Greenwood v. Peacock,

304 U.S. 808, 825 (1966).

The sole remaining question, whether §1981 confers the

same right not to be prosecuted for disobeying a state

2 Act of April 9, 1866, ch. 31, 14 Stat. 27.

3 Act of April 9, 1866, ch. 31, §1, 14 Stat. 27, provided: That all per

sons born in the United States and not subject to any foreign power,

excluding Indians not taxed, are hereby declared to be citizens of the

United States; and such citizens, of every race and color, without regard

to any previous condition of slavery or involuntary servitude, except as

a punishment for crime whereof the party shall have been duly convicted,

shall have the same right, in every State and Territory in the United

States, to make and enforce contracts, to sue, be parties, and give evidence,

to inherit, purchase, lease, sell, hold, and convey real and personal prop

erty, and to full and equal benefit of all laws and proceedings for the

security of person and property, as is enjoyed by white citizens, and'

shall be subject to like punishment, pains, and penalties, and to none

other, any law, statute, ordinance, regulation, or custom, to the contrary

notwithstanding.

6

judge’s order preserving courtroom segregation as that

recognized in Rachel, must be answered affirmatively. The

basis in Rachel for finding that 42 U.S. §§2000(a) and

20Q0a-2(c) (1964 ed.) protects sit-ins “not only from con

victions in state courts, but from prosecutions in those

courts” (384 U.S. at 804, emphasis in original), again,

was that language of §203(c) of the 1964 Act prohibiting

punishment for the attempt to exercise Title II rights.

In both Hamm v. The City of RocJc Hill, 379 U.S. 306, and

Rachel, the mere pendency of state prosecutions was

read as constituting punishment for engaging in the pro

tected acts. Analogously, §1981 also flatly states that

citizens, regardless of race or color, “shall be subject

to like punishment, pains, penalties, . . . and to no other”

as white citizens are subject to. This language, as un

equivocally as Title II, prohibits punishment on racial

grounds. It forbids appellant Ueison being punished when

other whites would not have been for sitting where other

whites can sit and for refusing to sit in an area reserved

for Negroes. Here, as in Rachel, it may be concluded

that any prosecution brought to punish Greison “will con

stitute a denial of the rights conferred by the Civil Rights

Act” (Rachel, at 804), and that the “burden of having to

defend the prosecution is itself the denial of a right

expressly conferred by the Civil Rights Act,” 384 U.S.

at 805.

The test of removal stated in Peacock, whether federal

laws confer upon the defendant the right to do that which

the state charges as an offense, and whether federal laws

confer “immunity” from prosecution from the charge, is

here fully met. Sections 1981 “confers an absolute right

on private citizens” (384 U.S. at 826) not to be racially

segregated in a state courtroom. And the prohibition on

unequal punishment contained in that section “confers im

7

munity from state prosecution on such charges,” id. at

827.

Any other result would be preposterous. It would re

quire the attribution to Congress of greater solicitude

against racial discrimination in a beanery than in a court

room. It would invoke §1443’s protection for rights con

ferred one hundred years after the removal statute was

enacted, and deny similar protection for the very rights

that enactment of that statute was originally meant to as

sure. It would assume that federal intervention is neces

sary to protect persons from a state court when they have

been discriminated against by a restaurateur, but not when

they have been discriminated against by the state court it

self. Yet, clearly, if there is ever a basis for “firm predic

tion that the defendant would be ‘denied or cannot en

force’ . . . specified federal rights in the state court” (384

U.S. at 804), that basis exists when the charge against

him is bottomed on his violation of a court-issued segrega

tion order.

Indeed, the state court segregation order constitutes a

separately sufficient ground for removal under §1443(1).

This is a case in which the defendant has already been

“denied . . . in the courts of such State a right under

[§1981].” The court’s segregation order, which Geison is

charged with violating, denied him such rights. Peacock

held that “It is not enough to support removal under

§1443(1) to allege or show that the defendant’s federal

equal civil rights have been illegally and corruptly denied

by state administrative officials in advance of trial. . . .

[T]hat does not show that . . . the defendant will be ‘denied

or cannot enforce in the courts’ of the State any right under

a federal law providing for equal civil rights.” 384 U.S.

at 827-828. But here the illegality has already occurred in

the courts of the State, and it is the state courts which

8

have already “denied . . . a right” not to be racially segre

gated, given by §1981.

Since the Federal District Court remanded the present

case without a hearing, appellant was even denied an oppor

tunity to establish that he was being prosecuted for con

tempt solely for racial reasons. Under Rachel (384 U.S.

at 805) it would be appropriate for the District Court to

determine whether the petition’s allegations are true and

thus clearly establish appellant’s right to removal under

§1443(1).

CONCLUSION

For the foregoing reasons the order of the District

Court remanding appellant’s case should be reversed.

Respectfully submitted,

Oscar W. A dams, Jr.

1630 Fourth Avenue North

Birmingham, Alabama 35203

Demetrius C. Newton

408 North 17th Street

Birmingham, Alabama 35203

A nthony G. A msterdam

3400 Chestnut Street

Philadelphia, Pa. 19104

Norman C. Amaker

Charles H. J ones, Jr.

J ack Greenberg

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

Attorneys for Appellants

9

Certificate of Service

I hereby certify that I have served copies of the Brief

for Appellant by mailing copies of same to Henry F.

Reese, Jr., Esq., County Solicitor, Dallas County Court

house, Selma, Alabama, and Blanchard McLeod, Esq.,

Circuit Solicitor, Camden, Alabama, by United States

mail, postage prepaid, this 21st day of April, 1967.

Attorney for Appellant

A P P E N D I X

STATUTORY APPENDIX

1. 28 U.S.C. §1443(1) (1964) :

§1443. Civil rights cases

Any of the following civil actions or criminal prosecu

tions, commenced in a State Court may be removed by

the defendant to the district court of the United States

for the district and division embracing* the place wherein

it is pending:

(1) Against any person who is denied or cannot en

force in the courts of such State a right under any law

providing for the equal civil rights of citizens of the

United States, or of all persons within the jurisdiction

thereof; . . .

2. 42 U.S.C. §1981 (1964) (R.S. §1977) (1870):

§1981. Equal rights under the law

All persons within the jurisdiction of the United

States shall have the same right in every State and

Territory to make and enforce contracts, to sue, be

parties, give evidence, and to the full and equal benefit

of all laws and proceedings for the security of persons

and property as is enjoyed by white citizens, and shall

be subject to like punishment, pains, penalties, taxes,

licenses, and exactions of every kind, and to no other.

3. 42 U.S.C. §2000a (a) (1964) (See, 201(a) of the Civil

Rights Act of 1964, 78 Stat. 243):

§2000a. Prohibition against discrimination or segre

gation in places of public accommodation—

Equal access

2a

(a) All persons shall be entitled to the full and equal

enjoyment of the goods, services, facilities, privileges,

advantages, and accommodations of any place of public

accommodation, as defined in this section, without dis

crimination or segregation on the ground of race, color,

religion, or national origin.

4. 42 TJ.S.C. §2000a-2 (1964) (Sec. 203 of the Civil Rights

Act of 1964, 78 Stat. 244):

§2000a-2. Prohibition against deprivation of, interfer

ence with, and punishment for exercising

rights and privileges secured by section

2000a or 2000a-l of this title

No person shall a) withhold, deny, or attempt to with

hold or deny, or deprive or attempt to deprive, any per

son of any right or privilege secured by section 2000a

or 2000a-l of this title, or (b) intimidate, threaten, or

coerce, or attempt to intimidate, threaten, or coerce any

person with the purpose of interfering with any right

or privelege secured by section 2000a or 2000a-l of this

title, or (c) punish or attempt to punish any person for

exercising or attempting to exercise any right or privi

lege secured by section 2000a or 2000a-l of this title.

M EIIEN PRESS INC. — N. Y. C. 219