Walker v. City of Birmingham Brief for Peitioners

Public Court Documents

October 3, 1966

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Walker v. City of Birmingham Brief for Peitioners, 1966. 7a60ad47-c89a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/38680d4a-a1ed-4001-a111-dda395b649f7/walker-v-city-of-birmingham-brief-for-peitioners. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

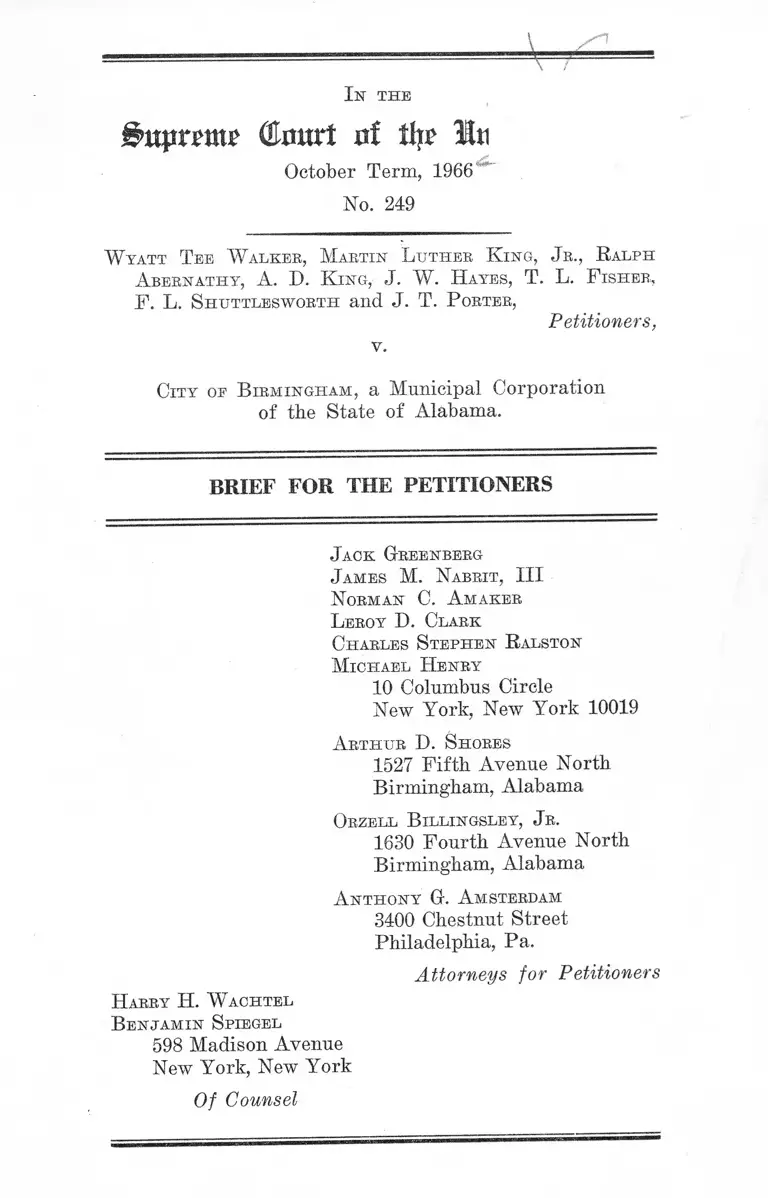

I n th e

Buptmu (tart uf tlj? Initt

October Term, 1966

No. 249

W yatt T ee W alker , M artin L u th er K in g , J r ., R alph

A bern ath y , A. D. K in g , J. W. H ayes, T. L. F ish er ,

F . L. S h u ttlesw orth and J. T . P orter,

Petitioners,

v.

C it y oe B ir m in g h a m , a Municipal Corporation

of the State of Alabama.

BRIEF FOR THE PETITIONERS

J ack Greenberg

J am es M. N abrit , III

N orman C. A m aker

L eroy D . Clark

Charles S teph en R alston

M ichael H en ry

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

A r th u r D . S hores

1527 Fifth Avenue North

Birmingham, Alabama

Orzell B illin gsley , J r .

1630 Fourth Avenue North

Birmingham, Alabama

A n t h o n y G. A msterdam

3400 Chestnut Street

Philadelphia, Pa.

Attorneys for Petitioners

H arry H . W ach tel

B e n ja m in S piegel

598 Madison Avenue

New York, New York

Of Counsel

INDEX

PAGE

Opinions Below ........................................... 1

Jurisdiction .......................................................................... 1

Questions Presented .......................................................... 2

Constitutional and Statutory Provisions Involved ..... 4

Statement .... .......................................... ............................... 5

1. Events Prior to the Injunction ........................... 6

2. The Injunction—April 10, 1963 ............................ 11

3. Speeches and Statements on April 11, 1963 ..... 13

4. Events on Friday, April 12, 1963— “Good

Friday” ............................................................. ,..... 16

5. Events on Sunday, April 14, 1963— “Easter

Sunday” ............................................... 19

6. Proceedings in the Courts Below ....................... 22

Summary of Argument ...................................................... 27

A kgum ent-—

I. The Petitioners Were Denied Due Process of

Law and the Equal Protection of the Laws by the

Circuit Court’s Exclusion of Their Proof That

the Birmingham Parade Permit Ordinance,

Which the Court’s Injunction Required Them to

Obey, Was Discriminatorily Applied to Refuse

Them Permits by Reason of Their Race and

Their Advocacy of Civil Rights ........................... 31

PAGE

11

II. The Petitioners Were Unconstitutionally Con

victed of Contempt for Engaging in Marches

Without a Permit .......................................... ........... 40

Introduction: The Unconstitutionally of the In

junction and the Parade Permit Ordinance......... 40

A. The unconstitutionality of section 1159 and

the injunction enforcing it may properly be

considered by this Court on review of peti

tioners’ contempt convictions because the re

fusal of the Alabama Supreme Court to enter

tain this federal defense is not an adequate

and independent state ground of decision ..... 49

B. The convictions denied petitioners due process

of law because there was no evidence that peti

tioners participated in a forbidden “unlawful”

parade or demonstration ..............................55

C. Since the injunction appears to forbid only

■ that which is “unlawful” a construction which

permits convictions under the injunction for

engaging in federally protected activity would

be void for want of fair notice and also for

want of any evidence of contumelious intent,

in violation of due process of law ................... 58

D. On this record, petitioners may not constitu

tionally be punished for violation of an injunc

tive restraint forbidden by the First Amend

ment and whose vagueness casts a broadly

repressive pall over protected freedoms of

expression............................. .... ..... ............... ...... 59

III. Petitioners King, Abernathy, Walker and Shut-

tlesworth Were Unconstitutionally Convicted of

Contempt for Making Statements to the Press

Criticizing the Injunction and Alabama Officials 71

I l l

IV. The Conviction of Petitioners Hayes and Fisher

Denied Them Due Process Because There Was

No Evidence That They Had Notice of or Knowl

PAGE

edge of the Terms of the Injunction ................... 77

Conclusion ...................................................................................... 81

x^PPENDIX—

Statutes of State of Alabama Conferring Con

tempt Powers on Courts ............. ......................... la

Some Ordinances of City of Birmingham, Ala

bama, Requiring Segregation by Race ............... 3a

T able of A uthorities

Cases:

Amalgamated Assoc. S.E.R.M.C.E. v. Wisconsin Em

ployment Relations Board, 340 U.S. 383 ................... 63

Ashton v. Kentucky, 384 U.S. 195 ................................. 47

Bantam Books, Inc. v. Sullivan, 372 U.S. 58 .............47,64

Barr v. City of Columbia, 378 U.S. 146 ......... ............... 54, 55

Blan v. United States, 340 U.S. 159 .............................. 66

^./'Board of Revenue of Covington County v. Merrill,

193 Ala. 521, 68 So. 971 .... ...................... ....... 50, 51, 53, 54

Bouie v. City of Columbia, 378 U.S. 347 ....................... 58

Bridges v. California, 314 U.S. 252 ...............................30, 74

Cafeteria Employees’ Union v. Angelos, 320 U.S. 293 .... 47

Cantwell v. Connecticut, 310 U.S. 296 .....................41, 47, 48

Carlson v. California, 310 U.S. 106 ....... ....................... 45

Carter v. Texas, 177 U.S. 442 ..... ...............................27, 38

Chauffeurs Union v. Newell, 356 U.S. 341 ................... 47

Coleman v. Alabama, 377 U.S. 129 ...............................27, 38

IV

Cox v. Louisiana, 379 U.S. 536 ...... ............ 36,41, 43-44, 47

Cox v. New Hampshire, 312 U.S. 569 .............25,44,45,56

Craig v. Harney, 331 U.S. 367 ...............................30, 74, 75

Dombrowski v. Pfister, 380 U.S. 479 ..... ....... ..47, 62, 63, 68

Donovan v. Dallas, 377 U.S. 408 .................................. 49

Edwards v. South Carolina, 372 U.S. 229 ................. 47

Ex parte Blakey, 240 Ala. 517, 199 So. 857 ................. 66

Ex parte Boscowitz, 84 Ala. 463, 4 So. 279 ....... ........... 66

- 'E x parte Connor, 240 Ala. 327, 198 So. 850 ...............51, 68

Ex parte G-eorge, 371 U.S. 72 ................................... . 49

\y Ex parte National Ass’n for Adv. of Colored People,

265 Ala. 349, 91 So.2d 214 ......... ...............................51-52

Ex Parte Wheeler, 231 Ala. 356, 165 So. 7 4 ................... 54

tx Parte White, 245 Ala. 212, 16 So.2d 500 ................... 54

Fields v. City of Fairfield, 273 Ala. 588, 143 So.2d 177

51, 52, 53

Fields v. City of Fairfield, 375 U.S. 248 ...............30, 55, 81

Fields v. South Carolina, 375 U.S. 4 4 ............................. 47

Fowler v. Rhode Island, 345 U.S. 67 ............................... 36

Freedman v. Maryland, 380 U.S. 51 .......................41,48, 62,

63, 64, 70

Garner v. Louisiana, 368 U.S. 157 ................................ 47, 55

Garrison v. Louisiana, 379 U.S. 64 ............................. ..74, 75

George v. Clemmons, 373 U.S. 241 .................................. 65

Gober v. Birmingham, 373 U.S. 374 ............................... 10

Hague v. C.I.O., 307 U.S. 496 ...................................36, 41, 43

Hamilton v. Alabama, 376 U.S. 650 ......... ....... .............30, 66

Henry v. Rock Hill, 376 U.S. 776 ....................... ............ . 47

Holt v. Virginia, 381 U.S. 131....... ................................ . 74

PAGE

V

Howat v. Kansas, 258 U.S. 181...................................... 52, 61

In re Shuttlesworth, 369 U.S. 35 ................................... 76

In re Willis, 242 Ala. 284, 5 So.2d 716 ...........31, 51, 68, 77

James v. United States, 366 U.S. 213 ...........................58, 59

Johnson v. Virginia, 373 U.S. 61 ...................................30, 65

Jones v. Opelika, 319 U.S. 103.... ..... ................................ 41

Kunz v. New York, 340 U.S. 290 ............. ................. 41, 43, 44

Largent v. Texas, 318 U.S. 4 18 ...................................... 41,43

Lombard v. Louisiana, 373 U.S. 267 ............................... . 37

Lovell v. Griffin, 303 U.S. 444 ...................................41, 43, 48,

57, 65

Marcus v. Search Warrant, 367 U.S. 717 ....................... 62

Marsh v. Alabama, 326 U.S. 501 ............. ......... .......... ...41, 63

McCollum v. Birmingham Post Co., 259 Ala. 88, 65

So.2d 689 ............................................................................ 54

Mills v. Alabama, 384 U.S. 214 ......... ........... ....... ......... 67

NAACP v. Alabama, 357 U.S. 449 ........................ ..53, 54, 55

N A A CP v. Alabama, 377 U.S. 288 .................. 55, 70, 76

NAACP v. Button, 371 U.S. 415 .................45, 47, 62, 64, 68

Near v. Minnesota, 283 U.S. 697 .................................. 64

New York Times Co. v. Sullivan, 376 U.S. 254 — ..... 74

Niemotko v. Maryland, 340 U.S. 268 ...............36, 41, 43, 44

Old Dominion Telegraph Co. v. Powers, 140 Ala. 220,

37 So. 195 ............................................................. ......... 51

Pennekamp v. Florida, 328 U.S. 331 ...................... 30, 74, 75

Poulos v. New Hampshire, 345 U.S. 395 ................... 44

Re Green, 369 U.S. 689 ...................................... 27, 39, 63, 64

Re Sawyer, 360 U.S. 622 .................................. ............. 74

PAGE

PAGE

Saia v. New York, 334 U.S. 558 .......................41,43,44,64

Schneider v. State, 308 U.S. 147 .............. ...................... 41,43

Shuttles worth v. City of Birmingham, 368 U.S. 959 .... 76

Shuttlesworth v. City of Birmingham, 373 U.S. 262 .... 76

Shuttlesworth v. City of Birmingham, 376 U.S. 339 ..53, 76

Shuttlesworth v. City of Birmingham, 382 U.S. 87 ..41, 55, 76

Shuttlesworth v. City of Birmingham, 43 Ala. App. 68,

180 So.2d 114 ........... ............................ ........... ...10, 37, 46, 76

Smith v. California, 361 U.S. 147 ...............................47, 62

Speiser v. Randall, 357 U.S. 513 ....................................... 62

Staub v. Baxley, 355 U.S. 313 ..............41, 42-43, 48, 54, 57, 65

Stevens v. Marks, 383 U.S. 234 ............................................. 66

Stromberg v. California, 283 U.S. 359 ...................30, 32, 73

Taylor v. Louisiana, 370 U.S. 154 ............................... 55

Terminiello v. Chicago, 337 U.S. 1 .......................30, 47, 73

Thomas v. Collins, 323 U.S. 516 ...................30, 32, 47, 49, 73

Thompson v. Louisville, 362 U.S. 199 ......... ..... 29, 30, 55,

57, 77, 81

Thornhill v. Alabama, 310 U.S. 88 ...........45,47,48,62,68

Tucker v. Texas, 326 U.S. 517 ....................................... 41

United States v. Alabama, 252 P. Supp. 95 (M.D. Ala.) 37

United States v. Shipp, 203 U.S. 563 ...................... . 61

United States v. United Mine Workers, 330 U.S. 258

29, 52, 59, 60, 61, 64, 67, 70, 71

Williams v. Georgia, 349 U.S. 375 ................................... 53

Williams v. North Carolina, 317 U.S. 287 ...................30, 73

Wood v. Georgia, 370 U.S. 375 .........................30, 32,47, 74

Wright v. Georgia, 373 U.S. 284 ....................................... 54

Yick Wo v. Hopkins, 118 U.S. 356 .27-28, 31, 35, 36,

37, 44,46

VII

Statutes:

Code of Alabama (Recompiled 1958), Title 13, §§ 4, 5, 9

5, la-2a

Code of Alabama (Recompiled 1958), Title 62, §§628,

632 ................ ..................................................................... 35

General Code of City of Birmingham. (1944), §1159

4, 5, 8,10,26, 32,

. 37,41, 42,43, 44,

45, 46,48, 49, 68

General Code of City of Birmingham (1944), §§369,

597 ............................................ ...... .. .......... .. ........... 5,23,3a

Building Code of City of Birmingham (1944), § 2002.1

5 ,3a

Other Authorities:

1963 Report of the U. S. Commission on Civil Rights ..37, 38

PAGE

Congress and the Nation, 1954-1964 (Congressional

Quarterly Service, 1965) ......................—............... ..... 37

Emerson, The Doctrine of Prior Restraint, 20 L aw &

C o n tem p . P rob. 6218 (1955) ....... ....................... ......... 64

Federal Rules of Civil Procedure, Rule 65(b)

Note, 109 TJ. Pa. L. Rev. 67 (1960) ..................

... 70

.47, 68

I n THE

'ttprm? (Exmrt ni % United States

October Term, 1966

No. 249

W yatt T ee W alker , M artin L u th er K in g , J r ., R alph

A bern ath y , A. D. K ing , J. W. H ayes, T. L. F isher ,

F. L. S h u ttlesw orth and J. T. P orter,

Petitioners,

v.

C it y of B ir m in g h a m , a Municipal Corporation

of the State of Alabama.

BRIEF FOR THE PETITIONERS

Opinions Below

The opinion of the Supreme Court of Alabama (R. 429-

447) is reported at 279 Ala. 53, 181 So.2d 493 (1965).

The opinion of the Circuit Court for the Tenth Judicial

Circuit of Alabama (Jefferson County) (R. 419-425) is

unreported.

Jurisdiction

The judgment of the Supreme Court of Alabama was

entered December 9, 1965 (R. 447-448), and rehearing was

denied January 20, 1966 (R. 449). On April 13, 1966, by

order of Mr. Justice Black, the time within which to file

a petition for a writ of certiorari was extended to June 19,

1966 (R. 451). The petition was filed June 18, 1966, and

was granted October 10, 1966 (R. 452). The jurisdiction

of this Court rests on 28 U.S.C. §1257(3), petitioners

2

having asserted below and here the deprivation of rights

secured by the Constitution of the United States.

Questions Presented

Petitioners, leaders of the civil rights movement in

Birmingham, Alabama in 1963, conducted protest marches

and other demonstrations against racial discrimination

and segregation in that city. On application by the City,

an Alabama state court issued an ex parte temporary in

junction restraining petitioners from parading or demon

strating without a permit and from other vaguely defined

“unlawful” activities. Petitioners have been convicted of

eriminal contempt of court for violating that injunction

by demonstrating without a permit, and for issuing a press

release critical of the injunction and of the Alabama courts.

The questions presented are:

(1) Whether the injunction and the Birmingham parade-

permit ordinance with which it requires compliance are

unconstitutional as vague, overbroad and censorial regula

tions of free speech, in violation of the First and Four

teenth Amendments?

(2) Whether, if the,injunction was unconstitutional, peti

tioners may constitutionally be punished for disobedience

of it? Specifically:

(a) Whether the refusal of the Alabama Supreme Court

to entertain petitioners’ First-Fourteenth Amendment chal

lenge to the injunction rests upon an adequate and in

dependent state ground?

(b) Whether, in view of the unconstitutionality of- the

ordinance, there is constitutionally sufficient evidence to

support a finding that petitioners violated the injunction,

prohibiting unlawful and unpermitted demonstrations?

3

(c) Whether, if the injunction’s prohibition of unlawful

and unpermitted demonstrations is retroactively read to

restrain demonstrations protected by the First and Four

teenth Amendments, petitioners’ contempt convictions are

void under the Due Process Clause for want of fair notice,

and for want of constitutionally sufficient evidence of con

tumacious intent?

(d) Whether, on this record, punishment of the peti

tioners for violating an ex parte temporary injunctive

order prohibited by the First and Fourteenth Amendments

itself violates those amendments?

(3) Whether the trial court, in this contempt proceeding,

improperly deprived petitioners of the opportunity to pre

sent a federal constitutional defense to the charge of vio

lating the court’s injunctive order, by excluding all of

the evidence proffered by them to show that Birmingham

city authorities discriminated on grounds of race and

arbitrarily repressed unpopular advocacy Of civil rights

in their administration of the parade permit ordinance

under which permits were required to be obtained by the

injunction?

(4) Whether petitioners M. L. King, Jr., Abernathy,

Walker and Shuttlesworth were convicted of contempt of

court in violation of the First and Fourteenth Amend

ments when their convictions rested in part upon charges

that they issued a press release critical of the injunction

against them and of the Alabama courts?

(5) Whether in the case of petitioners Hayes and

Fisher, there is constitutionally sufficient evidence to sup

port a finding that they had notice or knowledge of the

terms of the injunction ?

4

Constitutional and Statutory

Provisions Involved

1. This case involves the First Amendment and Sec

tion 1 of the Fourteenth Amendment to the Constitution

of the United States.

2. This case also involves the following ordinance of

the City of Birmingham:

General Code of City of Birmingham,

Alabama (1944), §1159

It shall be unlawful to organize or hold, or to

assist in organizing or holding, or to take part or

participate in, any parade or procession or other

6Ja •

r iLgr

public demonstration on the streets or other public

way of the city, unless a permit therefor has been

secured from the commission.

To secure such permrE7~written application shall

be made to the commission, setting forth the probable

number of persons, vehicles and animals which will be

engaged in such parade, procession or other public

demonstration, the purpose for which it is to be held

or had, and the .streets or other public ways over,

along or in which it is desired to have or hold such

parade, procession or other public demonstration.

! The commission shall grant a written permit for such

parade, procession or other public demonstration,

prescribing the streets or other public ways which

may be used therefor, unless in its judgment the pule

ma.ce, m M y , iiealth, dasengy, gaad-asdsf,

morals, or convenience require that it be refusecm It

shall be unlawful to use for such purposes any 'other

streets or public ways than those set out in said permit.

(

5

The two preceding paragraphs, however, shall not

apply to funeral processions.

3. The following Alabama statutes and Birmingham

municipal ordinances involved are set out in the Appendix,

infra, pp. la-3a.

Code of Alabama (Recompiled 1958), Title 13, §§4, 5, 9;

General Code of City of Birmingham, Alabama (1944),

§§369, 597;

Building Code of City of Birmingham, Alabama (1944),

§2002.1.

Statement

The petitioners are eight Negro ministers who were con

victed of criminal contempt as a result of incidents arising

out of their civil rights activities in Birmingham, Alabama,

in April 1963., Specifically, they were charged with vio

lating a temporary injunction which was issued ex parte

and without notice by the Circuit Court on April 10, 1963

(R. 37y on the complaint of the City of Birmingham veri

fied by City Commissioner Eugene “Bull” Commr _and

Police Chief JaniieT3pore^B. 26-37). On April 26. 1963,

petitioners were adjudged in contempt of the Circuit Court

for the Tenth Judicial Circuit of Alabama, and sentenced

to five days in jail and to pay $50 fines (R. 424-425), the

maximum penalty permitted by Code of Alabama, Title 13,

§9J The Supreme Court of Alabama granted certiorari

to review the case and stayed execution of the sentences

pending review (R. 23). The convictions were affirmed 1

1 There were 15 defendants in the trial court. The charges against

four were dismissed by the trial judge (R. 424). The convictions of

three others were quashed by the Alabama Supreme Court (R. 448).

6

by the Supremo Court of Alabama December 9, 1965

(R. 429, 447), and the stay was continued in effect pending

review in this Court (R. 449).

Petitioners are officers and members of the Southern

Christian Leadership Conference (S.C.L.C.), and its affi

liate, the Alabama Christian Movement for Human Eights

(A.C.M.H.R.).2 The organizations, described as Negro

protest organizations concerned with civil rights and racial

integration, sought to eliminate racial segregation by legal

means, and peaceful protests (R. 219, 320). A state in

vestigator assigned to study racial problems (R. 218)

testified that the organizations’ “teachings have been non

violent” (R. 220), and that “The general theme is non

violence in every program” (R. 221). He felt that they

“were supposedly teaching nonviolence but yet psycho

logically they were advocating violence” (R. 220). Further

program

and the situation to which it was addressed was excluded

as irrelevant aFHhe"trial: they made a proffer on this

subject (R. 297-298).3

1, Events Prior to the Injunction.

On April 3, 1963, a member of the A.C.M.H.R., Mrs.

Hendricks, was sent by Rev. Shuttlesworth to the Birming

ham City Hall to inquire about permits for picketing,

2 The Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. is President of S.C.L.C., Rev.

Wyatt Tee Walker was Executive Director o f S.C.L.C., Rev. Fred L.

Shuttlesworth was President of A.C.M.H.R. (R. 205).

3 Petitioners offejgd to prove that “ the Alabama Christian Movement

for Human Rights is an organization seeking to eliminate segregation..

in tlurTlifirTF'T^^ constitutionally protected activity

sucFTas free speech and picketing” and that “ there, is extensive segrega-

HonunTEe™^{y*T^7Birran^iaiirr ^and the organization was “seeking to

eliminate that segregation through peaceful protests against that policy

on the part of the City officials” (R. 297).

7

parading and demonstrating; she was accompanied by a

Baptist minister (B. 353-355). At the City Hall she went

first to the Police Department, spoke with a police officer

at the desk, Mr. Clayburn, and asked “to see the person

or persons in charge to issue permits, permits for parading,

picketmg*an3^monstratin^’_(R. 353). She then went to

the office of Commissioner Eugene “Bull” Connor (Public

Safety Commissioner of the City of Birmingham (R. 288)).

She testified:

I went to Mr. Connor’s office, the Commissioner’s

office at the City Hall Building. We went up and

Commissioner Connor met us at the door. He asked,

“May I help you?” I told him, “Yes, sir, we came

up to apply or see about getting aTperm iO orbicket-

ing, parading, demonMraimgyfT T . (R. 354).

I asked Commissioner Connor for the permit...and..

asked if he could issue the permit, or other persons

who would refer me to, persons who would issue a

permit. He said, “No. you will not get a permit in

Birmingham, AIal)£ina~To~mcEefl' T"will picket you

-qyej .fail,” n.fiTf he repeated that twice "

(R. 355).4 ’ ......*—==................... .

On April 5, 1963, petitioner Shuttlesworth sent a tele

gram to Commissioner Connor requesting a permit to

picket “against the injustices of segregation and discrim-

” ination” on desigmated_sidewa1ks on April 5th and 6th,

and stating “We shall observe the normal rules of picket-

4 Mrs. Hendricks’ testimony was not contradicted; however, the Court

granted the City’s motion to exclude it from the record saying, “ I don’t

think the statement of Mr. Connor would be binding on the Commission”

(E. 355).

8

_ing” (Exhibit B, B. 350, 416).5 Within a few hours, Mr.

'TTonnor wired back a reply:

UNDER THE PROVISIONS OP THE CITY CODE

OF THE CITY OF BIRMINGHAM, A PERMIT TO

PICKET AS REQUESTED BY YOU CANNOT BE

GRANTED BY ME INDIVIDUALLY BUT IS THE

RESPONSIBOITY (sic) OF THE ENTIRE COM

MISSION. I INSIST THAT YOU AND YOUR

PEOPLE DO NOT START ANY PICKETING ON

THE STREETS IN BIRMINGHAM, ALABAMA.

EUGENE “BULL” CONNOR, COMMISSIONER

OF PUBLIC SAFETY

(Exhibit A, R. 289, 415.)6

Petitioners made an effort to offer further proof with

respect to the administration of the Birmingham parade

permit ordinance (City Code §1159, quoted supra, pp. 4-5),

but the Court sustained the City’s objections to questions

5 The telegram stated: “DEAR MR. CONNOR, THIS IS TO CER

TIFY THAT THE ALABAMA CHRISTIAN MOVEMENT FOR HU

MAN RIGHTS REQUEST A PERMIT TO PICKET PEACEFULLY

AGAINST THE INJUSTICES OF SEGREGATION AND DISCRIMI

NATION IN THE GENERAL AREA OF SECOND THIRD AND

FOURTH AVENUES ON THE EAST AND WEST SIDEWALKS OF

19 STREET ON FRIDAY AND SATURDAY APRIL FIFTH AND

SIXTH. WE SHALL OBSERVE THE NORMAL RULES OF PICK

ETING. REPLY REQUESTED.”

6 On the next day, April 6, Shuttlesworth wired Commissioner Connor,

Birmingham Police Chief Jamie Moore, and County Sheriff Melvin

Bailey, stating that a group of not more than thirty persons would ac

company him to City Hall for a brief prayer service, and specifying

the route they would follow approaching and leaving City Hall, that

they would block no doors or sidewalks, where the group would disperse,

that it would be orderly, and that they would proceed “no more than

two abreast strictly observing all traffic signals” (Exhibit C, R. 361,

367, 417). Chief Moore said that no action was taken on the telegram

(R. 363). The marchers were arrested for parading without a permit

(R. 42, 72-73).

9

about tlie general practice (B. 281-287). Petitioners’ cmin-

sel stated that he wanted to “ascertain what is the nature

of marches, or parades in which -permits are granted”

and “ inquire into the procedure to see how these are ac

quired” (E. 282). Counsel stated that he planned to prove

through the city clerk that:

“The City Commission does not grant permits and

never has; that these are granted by the City Clerk

at the request of the traffic division according to no

published rule or regulation. We can establish it very

easily because that is in fact the practice” (E. 284).

The city clerk, who was also secretary to the Commissi on

(E. 281), testified that he kept a record of permits issued

for parades (E. 283). However, he was not allowed to

answer whether the Commission had ever voted to grant

a parade permit (E. 283). When the witness was asked

to describe the practice for granting permits, the Court

sustained an objection, saying:

I think the question asking for the general practice

in such instances cannot be allowed because the ordi

nance itself which is governing this situation allows

certain discretion in the City Commission, and to

attack the act of the Commission in this proceeding

would not be relevant (E. 284).

The witness did testify that there were no published rules

and regulations concerning the manner of applying for

parade permits apart from the City Code (E. 286). Peti

tioners’ counsel’s statement as to the practice, quoted above

(E. 284), was accepted as an offer of proof (E. 287). The

city clerk testified that petitioners had not appeared before

the City Commission to request a permit (E. 287). Peti

tioners also offered to prove by Commissioner Connor’s

1 0

testimony “that the City Commission has never issued any

permit” in any case, but objections to the questions were

sustained (E. 290). Commissioner Connor was asked

whether any picketing of any kind was permitted in

Birmingham, but objections to this question were also

sustained (R. 290-291).

Chief Inspector Haley, second ranking officer on the

police force (E. 145), said that he had seen various parades

in the city, and did not recall having made arrests for

any parade that had a permit; said that he got notice of

parades through the Chief’s office; and referred to some

parades as being “legal” (E. 178).

The City did not present any testimony with respect

to any of the parades or other demonstrations before the

date of the injunction, and petitioners were not allowed to

put on evidence about the demonstrations prior to the

injunction (E. 295-297). Some of these demonstrations

resulting in arrests of demonstrators are described in affi

davits by police officers and counter-affidavits by demon

strators which"were 'attached"to the pleadings (R. 39-43,

70-81).7

7 The police affidavits mentioned five sit-in demonstrations where there

were arrests for “ trespass after warning” and four episodes where pickets

or marchers were arrested for parading without a permit during the

period April 3 to April 10, 1963 (R, 39-42). Counter-affidavits by demon

strators were filed stating their version o f the same incidents (R. 70-81).

The marchers and pickets were arrested for parading without a permit

under City Code Section^ 1159, supra, p. 4. The demonstrators alleged

that the trespass after warning arrests were efforts by the City to en

force a city ordinance requiring separation of the races in restaurants,

City Code Section 369 (text at R. 69) (R. 67). This was the ordinance

involved in Gober v. Birmingham, 373 TT.S. 374 and the trespass prose

cutions were dismissed after that decision. The bulk of the prosecu-

tions for-jaarftfee^^athm t a permit under section I1159r'are~stdi pending

luvaiting.tlur.oujmme .(if ■'•'hiitlbsworlh v. City o f Birmingham,...4iL-41a,

App. 68, 180 So.2d 114 ( Section 1159 held unconstitutional), now pend

ing on certiorari in the Alabama Supreme Court! ” ^

1 1

2. The Injunction— April 10, 1963.

, At_9:0Q p.m. April 10, 1963 (B. 37),

the City filed a Bill of Complaint IB. 25-37), verified^ by

Commissioner Connor and Chief Moore, seeking injunctive

relief against 138 named individuals and two organiza-

tions, S.C.L.C. and A.C.M.H.B., and presented it to the

Hon. W. A. Jenkins, Circuit Judge. Among the 138 in

dividuals named as respondents in that complaint were

six of the eight petitioners in this Court.8 The City alleged

that from April 3 through April 10 “ respondents sponsored

and/or participated in and/or conspired to commit and/or

to encourage and/or to participate in certain movements,

plans or projects commonly called ‘sit-in’ demonstrations,

‘kneel-in’ demonstrations, mass street parades, trespass

on private property after being warned to leave the prem

ises by the owners of said property, congregating in mobs

upon the public streets and other public places, unlawfully

picketing private places of business in the City of Birming

ham, Alabama; violation of numerous ordinances and stat

utes of the City of Birmingham and State of Alabama; . . .”

It was alleged that this conduct is “calculated to provoke

breaches of the peace” and “threatens the safety, peace

and tranquility of the City” (B. 31-32). There were alle

gations with respect to several lunch counter demonstra

tions and processions on the streets (B. 32-33); a claim

that the conduct placed “an undue burden and strain upon

the manpower of the Police Department” ; a statement

that no “kneel-in” demonstration had occurred “up to the

present time,” but that the conduct alleged was “part of

a massive effort . . . to forcibly integrate all business es

tablishments, churches and other institutions” in the City

8 The petitioners named in the complaint were the Reverends Walker,

M. L. King,. Jr., A. D. King, Shuttlesworth, Abernathy and Porter

(R. 25). Petitioners J. W. Hayes and T. L. Fisher were not named in

the Bill o f Complaint. . «»-..... ,

0

1 2

and that “respondents are conspiring to and will conduct

‘kneel-in’ demonstrations at the various churches . . . in

violation of the wishes and desires of said churches unless

enjoined therefrom” (B. 35).

Immediately and without notice, Judge Jenkins issued a

temporary injunction restraining:

X

the respondents and the others identified in said Bill of

Complaint, their agents, members, employees, servants,

followers, attorneys, successors and all other persons in

active concert or participation with the respondents

and alFpersons having notice of said order from con

tinuing any act hereinabove designated particularly:

engaging in, sponsoring, inciting or encouraging mass

street parades, or mass processions or like demmistra-

jions wtHtouTIi permit, trespass on private property

after being warned to leave the premises bv the owner

j , or person in possession of said private property, con-

'**>_ gregating on the street,~oF*~pub!ic places into mobs.

v i and unlawfully picketing business establishments or

public building's in the City of Birmingham, Jefferson

. W , County, State of Alabama or performing acts cal-

' 4® .1 ulated to cause breaches of the peace in the City

77] of Birmingham, Jefferson County, in the State

of Alabama or from conspiring to engage in unlawful

street parades, unlawful processions, unlawful demon

strations, unlawful boycotts, unlawful trespasses, and

unlawful picketing or other like unlawful conduct or

f rom violating the ordinanHs~oTTEe~Crtv of Birming

ham and the Statutes of the State of Alabama or

from doing any acts designed to consummate con

spiracies to engage in said unlawful acts of parading,

demonstrating, boycotting, trespassing and picketing or

other unlawful acts, or from engaging in acts and con

duct customarily knoym^nT'^^ in churches in

w*

$ r O

\$*\* Y

jhi

13

violation of the wishes and desires of said churches

(R. 38).

Six of the petitioners were served on April 11 and

April 12; the court below found that petitioners Hayes and

Fisher (who were not named in the complaint) “were not

served with a copy of the injunction until after the Sunday

march” (R. 445), but concluded on the basis of the testi

mony that “ each of them had knowledge of the injunction

prior to that parade” (R. 445), and sustained their con

victions. A detailed and complete statement of the evi

dence concerning notice to Reverends Hayes and Fisher

is set forth below in the portion of the Argument urging

that they were convicted on a record containing no evi

dence that they had knowledge of the terms of the injunc

tion (infra, pp. 76 to 80).

3. Speeches and Statements on April 11, 1963.

The City’s evidence was that when the injunction was

served Rev. Shuttlesworth said, “ speaking of the injunc

tion handed to him: ‘This is a flagrant denial of our con

stitutional privileges’ ” (R. 194). A newsman described

Shuttlesworth’s reaction:

“In no way will this retard the thrust of this move

ment.” He said they would have to study the details.

He said, “An Alabama injunction is used to misuse

certain constitutional privileges that will never be

trampled on by an injunction. That is what they were

saying that particular night right after the injunction”

(R. 194).

At the same time, Rev. Abernathy made the statement,

“An injunction nor anything else will stop the Negro from

obtaining citizenship in his march for freedom” (R. 194).

14

Later, on April 11 at around 12:45 p.m., there was a

press conference attended by Revs. Martin King, Aber

nathy and Shuttlesworth; Rev. Walker distributed a press

release which Dr. King read aloud (R. 248-249). The text

of the statement, quoted in full in the opinion of the

Alabama Supreme Court (R. 431-433) (Complainants’ Ex

hibit 2; R. 409-410) is set out in the note below.9

9 The press release said:

In our struggle for freedom we have anchored our faith and hope

in the rightness of the Constitution and the moral laws of the uni

verse.

Again and again the Federal judiciary has made it clear that the

privileges guaranteed under the First and the Fourteenth Amend

ments are too sacred to he trampled upon hy the machinery of state

government and police power. In the past we have abided by

Federal injunctions out of respect for the forthright and consistent

leadership that the Federal judiciary has given in establishing the

principle of integration as the law o f the land.

However we are now confronted with recalcitrant forces in the

Deep South that will use the courts to perpetuate the unjust and

illegal system of racial separation.

[fol. 483] Alabama has made clear its determination to defy the law of

the land. Most of its public officials, its legislative body and many of

its law enforcement agents have openly defied the desegregation deci

sion of the Supreme Court. We would feel morally and legal responsi

ble to obey the injunction if the courts of Alabama applied equal jus

tice to all of its citizens. This would be sameness made legal. However

the issuance of this injunction is a blatant o f difference made legal.

Southern law enforcement agencies have demonstrated now and

again that they will utilize the force of law to misuse the judicial

process.

This is raw tyranny under the guise of maintaining law and order.

We cannot in all good conscience obey such an injunction which is

an unjust, undemocratic and unconstitutional misuse o f the legal

process.

We do this not out of any disrespect for the law but out o f the

highest respect for the law. This is not an attempt to evade or

defy the law or engage in chaotic anarchy. Just as in all good con

science we cannot obey unjust laws, neither can we respect the unjust

use of the courts.

We believe in a system of law based on justice and morality. Out

of our great love for the Constitution of the U, S. and our desire

to purify the judicial system of the state of Alabama, we risk this

critical move with an awareness of the possible consequences involved.

15

Police Lt. House said that after King read the state

ment, Shuttlesworth read another statement “more or less

re-affirming” what had been said by King (R. 250).; and

that Rev. King said “ The attorneys would attempt to dis

solve the injunction, but we will continue on today, tomor

row, Saturday, Sunday, Monday and on” (R. 252).

At a meeting in a church on the evening of Thursday,

April 11, King and-ARernathv made speechesAIBEiBfan-

ton, a radio station news director, testified that Dr. King

said. “Injunction oiy no jnjunetion we are going_ to_maxck...

■ .tomorrow” (R. 243); and that King also said, “ In our

movement here in Birmingham we have reached the point

of no return” and “Now Mr. Connor will know that the

injunction can’t stop us” (R. 244).10 He said Reverend

Abernathy led a call for volunteers, and Rev. Shuttlesworth

led the singing (R. 245). Mr. Stanton testified that Rev.

Abernathy made the statement, “I feel better tonight be

cause tomorrow me and Dr. King are going to jail” (R.

246). Another witness said that at the series of meetings

during April, they were recruiting people who were willing

to go to jail (R. 203).

10 J. Walter Johnson, an Associated Press reporter gave a different

account of King’s speech on the evening of April 11th. With respect to

the speeches by King and Abernathy, he said “ The word ‘injunction,’

itself, never did come up that I can remember or see offhand. They did

speak o f boycotts, and boycott was included with the entire movement”

(R. 188). He said that King’s speech had to do with a boycott o f stores

“until Negroes can use the lunch counters” (E. 189).

Johnson said that King said “Abernathy and I will make our move on

Good Friday, symbolizing the day Jesus hung on the cross,” and that

“We must love all white persons, we must love even Bull Connor” (R.190).

Abernathy said, “ I am against white supremacy, I am against black

supremacy, I am against any kind of racial supremacy” (R. 191).

Mr. Johnson was asked if there was any occasion when any o f them

used the . word “march” at all, and he responded “Not that I have, no,

sir.” (R. 191).

16

4. Events on Friday, April 12, 1963— Good Friday

All of the testimony about the events on the afternoon

of April 12, 1963, was given by two law enforcement offi

cers, W. J. Haley, Chief Inspector of the Birmingham police

force,11 and Lt. Willie B. Painter, investigator for the

Alabama Department of Public Safety.12

The police had advance information that there would be

a. ma.rclT'oir^ridav from a church at 16th Street and Sixth

Avenue to the City Hall (R. 146). Chief Inspector Haley

was telephoned by Rev. Wyatt Tee Walker who said that

he was calling for Martin Luther King, and that “ they in-

tended to make a march on City Hall. a.L12H^l’. (R. 180; see

also R. 176). Haley could not remember the date he re

ceived this call but knew that it referred to the Good Fri

day march. Haley told Walker “ that in my opinion that

would be a violation of the City ordinance and instructed

him that unless he obtained a permit for the same we would

have to arrest him, and asked him to convey that informa

tion to Martin Luther” (R. 180).

A crowd gathered in and around the church on Friday

from noon until about 2:00 p.m. (R. 206, 155). There were

350 to 400 people insi5e~the church (R. 148) and a large

crowdmoF~Kegroes gathered nearby on the sidewalks, in

private yards and in a large park near the church (R. 148,

161). Inspector Haley said that there werejighty^rjeighty-

five policemen in the area (R. 340). The officers were able

to keep the sidewalks and street clear (R. 182, 224), and

made no effort to disperse the crowd which was milling

around the area (R. 161, 223-224). The police blocked off

vehicular traffic before the march (R. 160, 163).

11 Chief Inspector Haley’s testimony about the Friday events is at

R. 145-148, 155-156, 159-164, 171-172, 175-176, 180-184 and 340.

12 Lt. Painter’ s testimony about the Friday afternoon events is at

R. 206-209, 222-225, 229.

17

At about 2 :00 p.m., Lt. Painter saw Revs. M. L. King,

Abernathy and Shuttlesworth arrive in a car driven by

Rev. Walker, and enter the church (R. 207). Walker drove

away (R. 207). “A short time thereafter a group came out

of the church and began what appeared to be a parade or a

march in the direction of downtown Birmingham” (R. 207).

“ The group was led by Rev. Martin Luther King, Jr., Rev.

Ralph Abernathy, Rev. Shuttlesworth” and others (R. 207).

Haley said that the ministers and the group following

them “were marching on the sidewalks two abreast” and

were evenly spaced (R. 156). He estimated “there were

approximately, I would say, fifty or sixty in the original j\.

march. Well, more than fifty, because fitty-one were ar-

rested” (R. 147). The ministers at the front of the march

were wearing long black robes over their suits (R. 184).

The marchers were orderly,13 carried no signs or placards

(R. 175), and did not cross against any red lights or violate

any traffic regulations (R. 160). They remained on the

sidewalk (R. 163, 229) and walked about two blocks before

they were stopped by the police where fifty-one marchers,

including petitioners Martin King, Abernathy and Shuttles

worth, were arrested for parading without a permit (R. 146,

147, 175).

Inspector Haley said that there were a “ large number of

on-lookers, or by-standers, that were not participating in

the actual march” who were “clapping and hollering and

hooping on the sidelines” (R. 146). He estimated that there

were “between one thousand and fifteen hundred that were

not participatinglh~tfrKaefiiar^ who were follow

ing and in various places in the area (R. 147). He said,

13 Asked if the marchers were orderly, Haley said: “ The marchers, as

far as I know, didn’t use any profanity. They were not taunting like

the crowd” (E. 163).

the sidewalk (R. 163).

He also said that they did not push an;

\AJ J M

18

A “ They were following the marchers, hnt not in the proces

sion. Most of them were on the south side of the street, and

the marchers had started on the north side . . .” (R. 146).

A Iter the arrest of the marchers, according to Haley, this

crowd got “ unruly” and three people were arrested “ one

* or two for loitering . . . and possibly one for resisting ar

rest, loitering and resisting” (R. 147). There was no evi

dence of violence or anything of that nature during or after

the Good Friday march led by King, Abernathy and

Shuttles worth.

Afterwards the crowd returned to the church where there

was a song and prayer service on the steps (R. 209). The

only petitioner, other than_King, Abernathy and Shuttles-

who was mentioned asbeuig present on Friday was

Rev. Walker.14 As the march proceeded, Walker walked

along with Lt. Painter and police Lt. Ralph Holmes follow

ing the marchers (R. 208). There was no testimony that

Walker was walking in the march and he was not arrested.15

“A short time after the arrests,” Painter observed Rev.

Walker standing “ in the middle of the block in the park . . .

waiving his arms” and directing people passing him to

“make one circle around the park” ; but the police ordered

them to disperse and they assembled at the church steps

for the song and prayer service (R. 208-209).

Neither of the police witnesses maintained that either the

marchers or the crowd of onlookers blocked the streets on

Friday. Chief Inspector Haley testified (R. 160):

Q. At the time these individuals were marching did

they march against any red lights or violate any traffic

regulations, anything of that sort? A. To my knowl-

14 There was no testimony that petitioners A. D. King, Hayes, Fisher

pi Porter were involved in the Friday march.

15 Haley did not see Walker that day (R. 171).

19

edge they did not. I couldn’t observe all of it. My at

tention was focused on the crowd and not on the lights.

The streets were wholly blocked off, so it would not

have made any difference so far as vehicular traffic was

concerned'. ~ ....~ ..-........

Q. Did the marchers block the streets off or did the

PoliceDepartment block the streets? A. The Police

Department 'had''‘previously blocked the vehicular traf

fic off.

And similarly (R. 163):

Q. Then after the marchers came out they did not

block any traffic or impede the free movement of people

on the streets, did they? A. The traffic was already

blocked for the marchers.

Q. The traffic was already blocked by the Police: De

partment? A. By the Police Department.

Lt. .Painter’s testimony was in accord: “ The streets were

basically kept open” (R. 225). .

Inspector Haley stated that the police did not allow any

white people (except press and policemen) to come into the

Negro area where these evenFsoccurred (R. 170); that there

was never any “ direct conflict or any direct contact between”

any whites and Negroes (R. 182) • and that the police de

partment was able to maintain law and order, although he

thought this was “haM'’’J7RTl8T183T7

5. Events on Sunday, April 14, 1963— “ Easter Sunday”

On Sunday, April 14, 1963, the police received “advance

word” (R. 149) that there would be a march from the

Thurgood C.M.E. Church (R. 165, 311) at S^fe^th Avenue

and Eleventh Street north toward the

Beginning around 2:30 or 3:00 p.m.

2 0

gather for about an hour and a half and a service began in

side the church (R. 214). Again the police assigned 80 or

85 men to the area (R. 340), and they allowed the crowd-

to congregate on .streets and sidewalks inThe area (h*. 166),16

making no effort to disperse them (R. 228, 267). The police

“blocked off the area,” rerouted all vehicular traffic away

from the area, and kept white people out of the neighbor

hood (R. 154). The officers established a “blockade” two

blocks from the church to stop the march (R. 216). Esti

mates of the total crowd in the area ranged as high as

1,500 to 2,000 people (R. 150, 231).17

Lt. Painter saw Rev. Walker “ forming a group of people

two or three abreast” outside the church (R. 214). Later

a group came out of the church and began walking at a

rapid rate along the sidewalk (R. 215). This group was led

by several ministers wearing robes, including petitioners

A. D. King, Porter, Hayes and Smith (R. 266-267), walking

two abreast (R. 169, 265, 266), down the sidewalk (R. 266).

Petitioner Fisher was also in the group (R. 302). (Peti

tioners M. L. King, Abernathy and Shuttlesworth, who had

been jailed on Friday, were not in the Easter march.) The

ministers walked a short distance, leading an estimaterLAQ-̂ ..

people (R. 233, 234, 235). Officer Higginbotham observed

them coming “ out of the church in two’s side by side” and

proceeding “ on the sidewalk” (R. 266). When they were

“marching north between 10th and 11th streets through a,

v a ca n lloP ^ IL 267), Higginbotham askecTTFTEey had a

16 Inspector Haley said: “ They were standing on people’s steps, stand

ing in people’s yards and just various places. Actually, I would say

most of them were on private property. There were some of them that

were on the sidewalk, but not enough to constitute a blockage or to

cause a police problem because the traffic department was there to take

care o f any traffic hazards that might come up” (E. 166).

17 Lt. Painter’s estimate was lower— “eight hundred or a thousand

people in the church and outside the church” (R. 214).

2 1

parade permit and when they said they did not (R. 268), he

placed Revs. Porter, A. D. King, Hayes and Smith under

arrest (R. 269). Rev. Fisher was also arrested (R. 302).

The total number arrested was said to be “ in the twenties”

(R. 150, 168).

When the ministers began their walk from the church,

--about three or four hundred people in -the. crowd which had

gathered outside began proceeding in a ma<s down the mid

dle ofJJie-ste©et-.(R. 156-157, 158).

The officers said that the crowd was singing and shouting

and that there was “a lot of heckling going on” (R. 269)

and that they were jeering and cursing and belittling the

police (R. 153). But officer Higginbotham said that the

mihlsfpTs|were “not loud or boisterous” (R. 268) and that

when" arrested' they “did notresisf in any respect” and

walked with him to the patrol wagon (R. 269).

h

One woman was arrested and she resisted^arrest, (R. 150-

15lJ7b:ur^hieFTnipeHor^nIey^aTd”’fhat “She was not a

member of the marchers. She was not dressed as a church

goer” (R. 150; see also 183). While the woman was being

subdued by the police several rocks were thrown, one nar-

g-missing the arresting officer, another hitting a motor-

[andfanother hitting a news photographer (R. 15, 216-

31-233). Three people who threw the rocks were im-

..mediately taken into custody by the police (R. 183, 217);

they were not identified by name at this trial, nor was there

any claim that they were among the marchers. Indeed,

Inspector Haley stated that the > episode of rock throwing

occurred after the twenty marcherswere arrested (R. 183).

__ aamjA w ere no other episodeiToTT^ the demon

stration ~ .. - ---------- '

Lt. Painter said that the police then moved out of the

area and the Negroes began walking back toward the

2 2

church, where he saw Rev. Wyatt Walker beckoning the

people to come inside (R. 217).

6. Proceedings in the Courts Below.

On April 15, 1963, petitioners filed a motion to dissolve

the injunction in which they asserted that the injunction

denied them due process of law under the Fourteenth

Amendment because it was issued without notice to them,

because it was excessively vague, because it was a prior

restraint on free speech protected by the First Amend

ment, because it was designed to enforce the city restau

rant. segregation law, because it was based upon a com

plaint which described only constitutionally protected con

duct, and because the parade ordinance upon which it was

based was excessively vague (R. 65-68). Petitioners also

filed a demurrer (R. 120-122), an answer (R. 122-124), and

an amended answer (R. 132-134) to the bill for injunction

in which they raised similar constitutional claims.

The court set a ihearing on the motion to dissolve for

April 22, 1963 (R. 82). ,

— ---------—■— ;— ------ -j

[ Later, on April 15, the City of Birmingham filed a motion

for an ord<mtosh<w should not be

held in contempt "?o7~vmlatnig- the temporary’Tnfunc^oii

(R. 82-90), The court issued an order directing petitioners

to appear on April 22 and show cause why they should

not be punished for contempt of court (R. 92-94).

At the beginning of the hearing the court ruled that even

though petitioners had filed their motion to dissolve first,

it would consider the contempt charge first (R. 139).

In response to the show cause order, petitioners filed a

“motion to discharge and vacate order and rule to show

cause” saying that they had not violated the injunction

because it .prohibited engaging in or encouraging others

23

to engage in “unlawful” conduct specified therein, whereas

the petitioners’ conduct was lawful conduct protected by

the First Amendment and the due process and equal pro

tection clauses of the Fourteenth Amendment to the Con

stitution of the United States. Petitioners also said that

the original bill for injunction upon which the temporary

injunction was based did not show that they had engaged

in unlawful conduct but that they had engaged in conduct

protected by the First and Fourteenth Amendments (E.

125-126).

In their answer to the petition for a show cause order,

petitioners described the lawful conduct protected by the

First and Fourteenth Amendments in which they had en

gaged : • - <>f"" •

a) Walking two abreast in orderly manner on the

public sidewalks of Birmingham observing all traffic

regulations with prior notice having been given to

city officials in order to peacefully express their protest

against continuing racial discrimination in Birming

ham.

\ i

b) Peaceful picketing in small groups and in orderly

manner of publicly and privately owned facilities.

c) Eequesting service in privately owned stores open

to the general public in exercise of their right to equal

protection of the laws and due process of law which

are denied by Section 369 of the 1944 General City

Code of Birmingham (R. 128-129).

Petitioners’ motion for a severance of civil and criminal

contempt charges against them (R. 127, 140), was denied

(R. 140).

After the City rested, and again at the end of the trial,

petitioners moved “ to exclude the evidence,” in an oral

V

24

motion (R. 272, 370), later reduced to writing (R. 135),

in which they asserted that there was no evidence showing-

why they should be punished for contempt based on “the

statements made publicly at press conferences and mass

meeting on April 11, 1963,” since the evidence showed that

they had “ engaged only in activity protected by the First

Amendment and by the due process clause of the Four

teenth Amendment to the Constitution of the United

States.” Petitioners T. L. Fisher and J. W. Hayes as

serted that there was no evidence showing that they were

served with copies of the court’s injunctive order of April

10, 1963, prior to their arrest and imprisonment for parad

ing without a permit on April 14, 1963 (R. 135-137).

The issues at the trial were subsequently specified by

the Supreme Court of Alabama by quoting (R. 437) a

colloquy which occurred during the hearing:

During the hearing on the charge that petitioners

had violated the injunction, the trial court stated

the issues presented by the evidence as follows:

The Court: The only charge has been this nartic.-

I ular parade, the one on Easter Sunday and the one ,

I j on G-ood Friday, and on the question of the meeting,

I j at which time some press release was issued. Am I

correct m that?

Mr. McBee: Essentially that is correct.

The Court: T~doh7F¥^~wof any other evidence

or any other occasions other than those, and I see no

need of putting on testimony to rebut something

where IlLereTiaiT>ee5^^

At the outset of its opinion adjudging petitioners in con

tempt, the trial court noted...that the petitioners were

charged with violating the temporary injunction “by their

25

issuance of a press release . . . which release allegedly con-

tained derogatory statements concerning Alabama courts

and the injunctive order of this Court in particular” (R.

420). The opinion said they were “ further” charged with'

violating the injunction by participatlng~m~and conducting

TeHaanparades in violation of a city ordinance prohibiting

“parades without

These were “past acts of disobedience and disrespect for the

orders of this court and the nature of the orders sought

would be to punish the defendants” the proceeding was

“an action for criminal contempt” (R. 420). The

subsequently found generally that “ the actions” (without

further specification) of petitioners were “ obvious acts

of contempt, constituting deliberate and blatant denials of

the authority of this Court and its order” (R. 422).

l/tf y-tHA-gs

In response to petitioners’ claim that their acts were

lawful because constitutionally protected by the First and

Fourteenth Amendments, the trial court held that Section

1159 (the parade-permit ordinance) “ is not invalid upon

its face as a violation of the constitutional rights of free

speech as afforded to these defendants in the absence of a

showing of arbitrary and capricious action upon the part

of the Commission of the City of Birmingham in denying

TEe~ciHen(Ian1jrir’̂ ^

Judge Jenkins cited Cox v. New Hampshire, 312 U.S. 569,

to sustain the parade ordinance (R. 422). The Court then

said that “ legal and orderly processes” required defen

dants to attack an unreasonable denial of a permit by a

motion to dissolve the injunction, and that since this was

not done, “ the Court is of the opinion that the validity

of its injunction order stands upon its prima facie au

thority to execute the same” (R. 422).

In their petition for certiorari to the Supreme Court of

Alabama, petitioners made substantially the same claims

26

as below, asserting that the judgment of contempt denied

rights secured by the First and Fourteenth Amendments

in that the punishment constituted a prior restraint on

freedom of speech, association, and the right to petition

for redress of grievances; that the injunction was excessive

and vague, contrary to the due process clause of the Four

teenth Amendment, particularly in the context of an order

restraining First Amendment rights; that the City of

Birmingham failed to produce evidence which showed that

petitioners did anything other than exercise constitutional

rights of free expression; and that, therefore, the con

tempt decree was based on no evidence of guilt, in viola

tion of the due process clause of the Fourteenth Amend

ment (R. 21-22).

The Alabama Supreme Court held that because peti

tioners admittedly continued protest demonstrations after

the injunction issued, they violated the order against en

gaging in parades without permit (R. 437-438). The Court

said, “Petitioners rest their case on the proposition that

Section 1159 of the General City Code of Birmingham,

which regulates street parades, is void because it violates

the First and Fourteenth Amendments of the Constitu

tion of the United States, and, therefore, the temporary

injunction is void as a prior restraint on the constitution

ally protected rights of freedom of speech and assembly”

(R. 439-440). The Court held that “ the circuit court had

the duty and authority, in the first instance, to determine

the validity of the ordinance, and, until the decision of

the circuit court is reversed for error by orderly review,

either by the circuit court or a higher court, the orders

of the circuit court based on its decision are to be respected

and disobedience of them is contempt of its lawful au

thority, to be punished” (R. 444). It therefore affirmed

petitioners’ convictions for contempt.

27

Summary of Argument

I.

The trial court adjudged petitioners in contempt of court

for violation of its injunctive order without affording them

an opportunity to prove thaUag the racially discriminatory

‘withholding of parade permits city authorities prevented

them from doing what the injunctive order required.

The court "CtelltEcT petitioners an~opportunity to prove:

that Birmingham city authorities discriminatorily admin

istered the parade permit ordinance and assumed arbitrary

and censorial control over the use of the city streets by

abuse of the permit power; that these authorities wrong

fully refused for racial reasons to grant permits for peace

ful civil rights demonstrations; that these authorities, in

order to deny petitioners their federal constitutional rights

of free speech and equal protection of the laws, applied

for and obtained from the trial court the ex parte injunc

tion which forbade the petitioners to conduct demonstra

tions ; and that the same authorities, by manipulation of the

procedures of the permit-application process, and abuse

of their discretion in passing on requests for permits, wil

fully violated the Equal Protection Clause in denying peti

tioners the permits to demonstrate required by the parade

permit ordinance and injunctive order.

This abuse of the state judicial process denied petition

ers due process of law and equal protection of the laws.

Petitioners were entitled to a hearing on the contempt

charges before being convicted. Re Green. 369 U.S. 689,

and, at that hearing, they were entitled to an opportunity

to prove their federal constitutional defense to the criminal

charge, Carter v. Texas, 177 U.S. 442, 448-49; Coleman v.

Alabama, 377 U.S. 129, 133. Under Yick Wo v. Hopkins,

28

118 U.S. 356, racially discriminatory administration of the

permit ordinance to which this injunction commanded

obedience was such a defense.

II.

Petitioners’ contempt convictions are based upon an in

junction which orders obedience to the Birmingham parade

ordinance. That ordinance is unconstitutional because i t —

grants unfettered administrative discretion to regulate free

expression, and in other regards as well is a vague and over.-

broad encroachment on First Amendment rights. Addi

tionally, the injunction is unconstitutionally vague, in vio

lation of the First and Fourteenth Amendments.

Because the injunction is void, reversal of petitioners’

convictions must follow, for four independent reasons:

A. Review by this Court of petitioners’ First and Four

teenth Amendment objections to the injunctive order is

required because the refusal of the Alabama Supreme Court

to entertain those objections does not rest on an adequate

and independent state ground. Alabama courts, as a nrac-

tical matter, exercise discretion to heaxAhe.kind of .federal

claimmsallowed bv the c.ouxLhelow. Moreover, petitioners

were rfairly entitled to believe that they could raise their

federalclaim defensively in the contempt proceeding.

B. The injunctive order against petitioners prohibited

only unlawful and unpermitted parades and demonstrations.

In the absence of any indication of contrary construction

placed upon it by the courts below, this order must be read

consistently with the Supremacy Clause as prohibiting

only unpermitted parades and demonstrations.for which-

_the State of A labama could constitutionally demand a per

mit.| Since petitioners’ permitless activxti65Twere at worst

in violation of a constitutionally invalid permit ordinance,

29

there is no evidence within the standard of Thompson v.

Louisville, 362 U.S. 199, to support a finding that they

acted unlawfully within the meaning of the injunction.

C. If the injunctive order is construed, contrary to its

apparent meaning, to prohibit unpermitted parades and

demonstrations protected by the federal Constitution, peti

tioners’ convictions must nevertheless be reversed for two

reasons. First, such a reading of the order .deprives them

of the fair warning demanded by the Due Process Clause. ̂

Second, there is no evidence within the standard of Thomp

son v. Louisville, supra, to support a finding of contumelious

intent where what is shown is that petitioners complied

with the apparent meaning of the order and relied upon

clearly controlling decisions of this Court in thinking their

demonstrations lawful.

D. Assuming, arguendo, contrary to arguments II (A ),

(B) and (C) above, that petitioners did willfully violate

the injunction after adequate notice, and that regular and

consistently applied Alabama procedures forbid testing

the invalidity of an injunction in a contempt proceeding,

these procedures may not constitutionally be applied to

punish petitioners for disobeying this federally unconstitu

tional injunction. The doctrine ordinarily associated with

United States v. United Mine Workers, 330 tT.I§7258, should"

n ot be'' exf ended to tfiehm iF’oI its logic so as to invade

f hn^rdvincF~or*Jbirst AmendmentTreedoms, especially In

a case, such as th is/InvoM ng”a

--TTgfenilv'uncom^ issued "ex purTU,

effecting wholesale, repression of speech during the onb/

time"yyhrm̂ t-<*j*Hdd -d ^ of social

To extend Mine Workers into the area of free expression

would sanction an intolerable prior restraint. This is espe

cially true here, where the incorporation of the Birmingham

parade ordinance into the injunction renders city admin

30

istrators the censors of the streets. The legitimate concern

of preserving respect for the courts does not countenance

destruction of individual rights through judicial fiat. John

son v. Virgina, 373 U.S. 61; Hamilton v. Alabama, 376

U.S. 650.

III.

Petitioners Martin King, Abernathy, Walker and Shut-

tlesworth were unconstitutionally punished for criminal

contempt for publishing a press release criticizing the in

junction and Alabama officials. Issuance of the press re

lease was one of the several acts of contempt charged and

thus part of the basis for the trial court’s general ad

judication of guilt. As this charge is constitutionally vul

nerable their convictions must be reversed. Thomas v.

Collins, 323 U.S. 516, 529; Stromberg v. California, 283

U.S. 359, 367-368; Williams v. North Carolina, 317 U.S.

287; Terminiello v. Chicago, 337 U.S. 1.

The press release criticizing the injunction as an “un

just, undemocratic and unconstitutional misuse of the

legal process” and criticizing Alabama officials for pre

serving segregation was constitutionally protected speech.

Garrison v. Louisiana, 379 U.S. 64; New York Times Co.

v. Sullivan, 379 U.S. 254; Wood v. Georgia, 370 U.S. 375;

Bridges v. California, 314 U.S. 252; PenneJcamp v. Florida,

328 U.S. 331; Craig v. Harney, 331 U.S. 367.

IV.

Petitioners J. W. Hayes and T. L. Fisher were denied

due process because there was no evidence of an essential

element of criminal contempt. Thompson v. Louisville,

362 U.S. 199; Fields v. City of Fairfield, 375 U.S. 248.

Hayes and Fisher were not parties to the injunction suit

or served with the order before their alleged contemptuous

31

conduct. To prove contempt under Alabama law it is

therefore necessary to establish that they had notice of

the injunction’s restraints and were familiar with its pro

visions. In re Willis, 242 Ala. 284, 5 So.2d 716, 721. There

was no evidence that Hayes and Fisher were advised of

the terms of the injunction or that it applied to their

conduct.

ARGUMENT

I.

The Petitioners Were Denied Due Process o f Law

and the Equal Protection of the Laws by the Circuit

Court’s Exclusion of Their Proof That the Birmingham

Parade Permit Ordinance, Which the Court’ s Injunction

Required Them to Obey, Was Discriminatorily Applied

to Refuse Them Permits by Reason of Their Race and

Their Advocacy of Civil Rights.

Without regard to the other issues presented here, peti

tioners’ convictions of contempt for violating an injunc

tion against parading without a permit must be reversed

on the ground that they were denied an opportunity to

offer proof in support of a federal constitutional defense

to the charge. The defense offered, grounded on this

Court’s decision in Tick Wo v. Hopkins, 118 U.S. 356, was

that petitioners were prevented from complying with the

permit requirement because of discriminatory adminisfra-.

tion of the permit law. They contended that Eugene “Bull”

"Connor, the Birmingham Public Safety Commissioner who

obtained the injunction forbidding their demonstrations

without permits, alsij.-disc.rimmatflnly.jie.nie.dih

to conduct demonstrations.

32

The essence of the contempt charge against petitioners

was that they violated the Circuit Court’s injunction by

participating in parades or demonstrations without first

having obtained permits under section 1159 of the General

City Code of Birmingham.18 The relevant portions of the

injunction restrained petitioners from (a) engaging in

parades “without a permit,” (b) conspiring to engage in

“unlawful” parades, and (c) violating the “ ordinances

of the City.” In terms, the order restrained:

. . . engaging in, sponsoring, inciting or encouraging

mass street parades or mass processm nsorlike dem-

onstralions 'wUK<nil"crp erm i,\' ‘ r c o n s^

in unlawful street parades, unlawful processions, un

lawful demonstrations . . . or from violating the ordi

nances of the City of Birmingham . . . or from doing

any acts designed to consummate conspiracies to en

gage in said unlawful acts of parading, demon

strating . . . (B. 38; emphasis added).

It is plain that, as the City cast its pleadings r

both courts below viewed the issue, the permit requirement

en f orceTTyvHl’iF'TnTimc^

faommgTljETali^ the City

"CoSeTan?"£EaFTEe~on!yT̂ unlawT^

after charged as contempt was a failure to obtain such a

permit before participating in parades or demonstrations.

18 Four of the petitioners were also charged with contempt because of

allegedly derogatory remarks about the Circuit Court and its injunction

in a press release. This separate issue is treated in part III of the Argu

ment below, pp. 71 to 75. As the petitioners were found guilty gen

erally under an accusation that charged both parading without a permit

and issuing of the press release, and a single penalty was imposed, the

conviction must be reversed if either of the charges is constitutionally

vulnerable. Thomas v. Collins, 323 U.S. 516, 529; Stromberg v. California,

283 U.S. 359, 367-368; Williams v. North Carolina, 317 U.S. 287, 291-293.

“ The judgment therefore must be affirmed as to both [charges] or as to

neither.” Thomas v. Collins, supra, 323 U.S. at 529.

33

The injunction was not an unconditional order against

marches, but an order against marching without a permit.

The court in its injunctive decree left the decision whether

to allow marches to the licensing officials, and thus ex

pressly committed the legality of petitioners’ conduct to

the licensors’ discretion.

Subsequently adjudicating petitioners in contempt, the

Circuit Court stated their charged contemptous conduct

to be “violation of the said injunctive order by the defen

dants’ participating in and conducting certain alleged

parades in violation of an ordinance of the City . . . which

prohibits parading without a permit” (R. 420). And the

Alabama Supreme Court affirmed the contempt convictions

on the finding that petitioners “did engage in and incite

others to engage in mass street parades and neither peti

tioners nor anyone else had obtained a permit to parade

on the streets of Birmingham” (R. 438). There was no

claim or proof that petitioners violated any of the other

portions of the injunction such as those restraining tres

passes, boycotts, picketing or demonstrations in churches.

In defense against the contempt charge, petitioners there

fore offered to prove that they could not have obtained

a permit as required by the injunction because of the dis

criminatory administration of the permit law.19 They

claimed that an established pattern of discriminatory de

nials of permits to them, and the discriminatory enforce

ment against them of unusual and frustrating procedural

requirements in applying for permits, made their applica

tion futile and converted the injunction into a racial trap.

But the Circuit Court entirely foreclosed this issue at the

15 Petitioners averred that they “were arbitrarily unlawfully and un

constitutionally denied a permit to parade and demonstrate, and picket

against racial segregation, in a peaceful manner, on the streets of the

City of Birmingham, Alabama in violation of . . . the due process and

equal protection clauses of the Fourteenth Amendment . . (R. 137).

34

contempt trial, holding that “the only question was did

they or did they not have a permit” (R. 177).

Efforts by petitioners to establish the discriminatory