Legal Defense Fund Files 12 Complaints Charging Discrimination in Hospitals

Press Release

July 15, 1965

Cite this item

-

Press Releases, Volume 2. Legal Defense Fund Files 12 Complaints Charging Discrimination in Hospitals, 1965. 75c4ca16-b692-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/38fa06a1-6fe9-4186-addb-487fc6695aef/legal-defense-fund-files-12-complaints-charging-discrimination-in-hospitals. Accessed January 25, 2026.

Copied!

vy

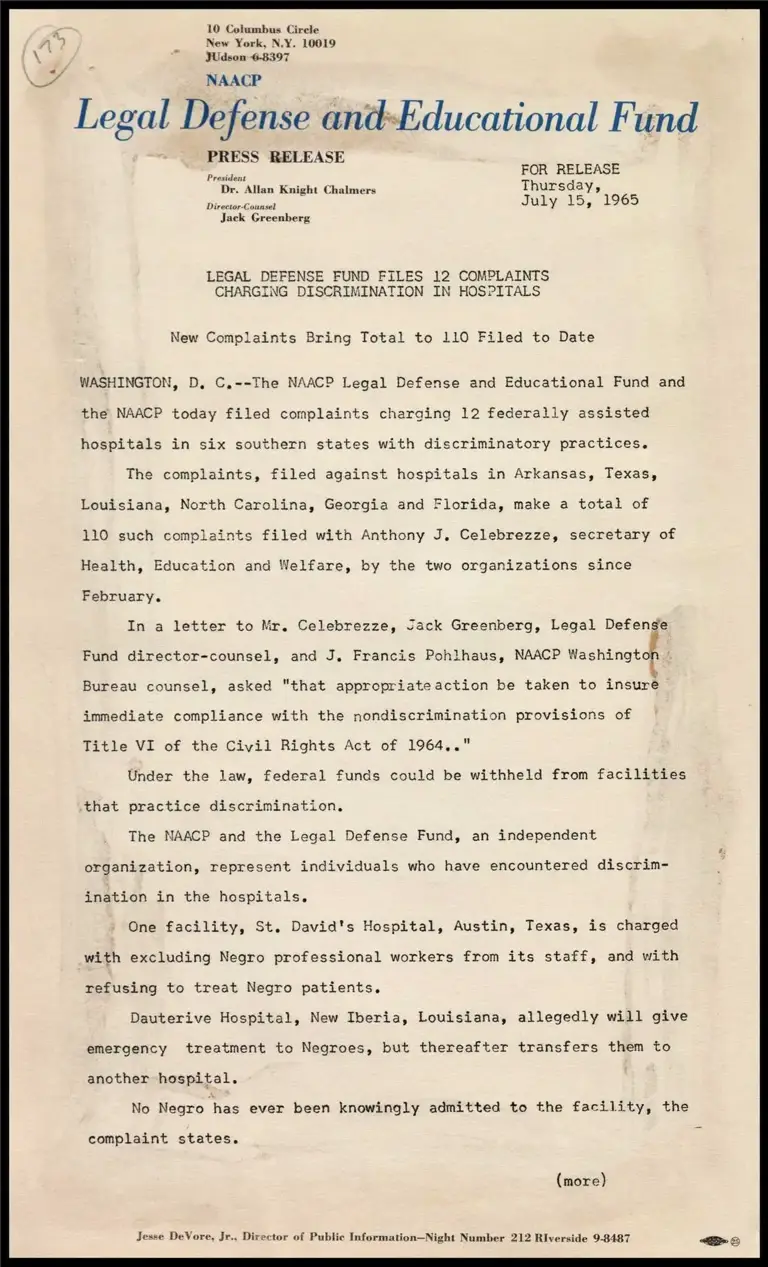

10 Columbus Circle

New York, N.Y. 10019

Wdson 6-8397

NAACP

Legal Defense and-Educational Fund

PRESS RELEASE

ails FOR RELEASE

Dr. Allan Knight Chalmers Thursday,

Director-Counsel July 15, 1965

lack Greenberg

LEGAL DEFENSE FUND FILES 12 COMPLAINTS

CHARGING DISCRIMINATION IN HOSPITALS

New Complaints Bring Total to 110 Filed to Date

WASHINGTON, D, C,--The NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund and

the NAACP today filed complaints charging 12 federally assisted

hospitals in six southern states with discriminatory practices.

The complaints, filed against hospitals in Arkansas, Texas,

Louisiana, North Carolina, Georgia and Florida, make a total of

110 such complaints filed with Anthony J, Celebrezze, secretary of

Health, Education and Welfare, by the two organizations since

February.

In a letter to Mr. Celebrezze, Jack Greenberg, Legal Defense

Fund director-counsel, and J, Francis Pohlhaus, NAACP Washingto

Bureau counsel, asked "that appropriateaction be taken to insure

immediate compliance with the nondiscrimination provisions of

Title VI of the Civil Rights Act of 1964,."

Under the law, federal funds could be withheld from facilities

that practice discrimination.

The NAACP and the Legal Defense Fund, an independent

organization, represent individuals who have encountered discrim-

ination in the hospitals.

One facility, St. David's Hospital, Austin, Texas, is charged

with excluding Negro professional workers from its staff, and with

refusing to treat Negro patients.

Dauterive Hospital, New Iberia, Louisiana, allegedly will give

emergency treatment to Negroes, but thereafter transfers them to

another hospital.

No Negro has ever been knowingly admitted to the facility, the

complaint states.

(more)

Jesse DeVore, Jr., Director of Public Information—Night Number 212 RIverside 9-8487

aoe

‘Legal, Defense Fund’ Files 12 Complaints

Charging eee tienes ron in Hospitals z

Other hospitals are charged with-maintaining segregated wards, '

wings and floors, segregated lounges, dining facilities, rest rooms

and Mek ting offices and refusal to hire Negro professtonaimammtoyee

and 2 GRR 3 i

THe 12 hospitals named in the complaints are: Union County

and Warner Brown Hospitals, ElDorado, Arkansas; St. David's

Hospital, Austing Texas; Dauterive and Iberia Parish Hodbitals,

New Iberiay Louisiana, and Lasalette Hospital, Loreau, Houtsi ana;

Also, Northern Surrey Hospital, Mount Airy, North rolina;

Baldwin County Hospital, Milledgeville, Georgia; Hutche son

Memorial Tri-County Hospital, Fort Oglethorpe, Georgia; Peicasseus

Cameron Hospital, Sulpher, Louisiana; Bay Memorial Hospital;

*

Panama City, Florida, and Henderson County Hospital, Trinidad, Texas.

-30- 3