Dowell v. Oklahoma City Board of Education Petition for Rehearing with Suggestion for Rehearing En Banc

Public Court Documents

September 24, 1969

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Dowell v. Oklahoma City Board of Education Petition for Rehearing with Suggestion for Rehearing En Banc, 1969. cde01e31-b09a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/391e95e6-4053-43c1-9a99-34cc8f3731ee/dowell-v-oklahoma-city-board-of-education-petition-for-rehearing-with-suggestion-for-rehearing-en-banc. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

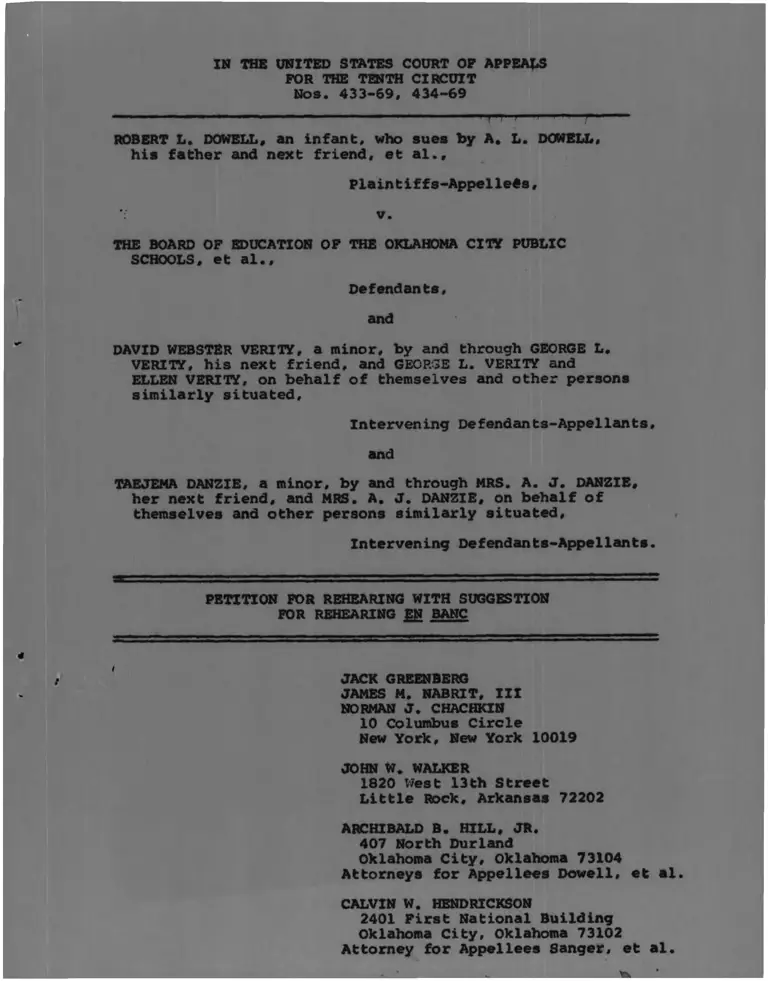

IN THE UNITED STATES COURT OP APPEALS

FOR THE TENTH CIRCUIT

Nos. 433-69, 434-69

— —..................................- ......... . ............ ............... — ........... — r -

ROBERT L. DOWELL, an infant, who sues by A, L. DOWELL,

his father and next friend, et al..

Plaintiffs-Appelle#s,

: V .

THE BOARD OF EDUCATION OF THE OKLAHOMA CITY PUBLIC

SCHOOLS, et al..

Defendants,

and

DAVID WEBSTER VERITY, a minor, by and through GEORGE L.

VERITY, his next friend, and GEORGE L. VERITY and

ELLEN VERITY, on behalf of themselves and other persons

similarly situated.

Intervening Defendants-Appellants,

and

TAEJEMA DANZIE, a minor, by and through MRS. A. J. DANZIE,

her next friend, and MRS. A. J. DANZIE, on behalf of

themselves and other persons similarly situated.

Intervening Defendants-Appellants.

PETITION FOR REHEARING WITH SUGGESTION

FOR REHEARING £N BANC

JACK GREENBERG

JAMES M. NABRIT, III

NORMAN J. CHACHKIN

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

JOHN W. WALKER

1820 West 13th Street

Little Rock. Arkansas 72202

ARCHIBALD B. HILL, JR.

407 North Durland

Oklahoma City, Oklahoma 73104

Attorneys for Appellees Dowell, et al.

CALVIN W. HENDRICKSON

2401 First National Building

Oklahoma City, Oklahoma 73102

Attorney for Appellees Sanger, et al.

. *'• r > « i t

1 ' *

*.M ' - V

* -i i --i?' K '

'• ■ ‘ ’ ■■■■ t".

:v ■■ - r ■.. **j-

■Hw';

IN THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE TENTH CIRCUIT

Nos. 4 3 3 -6 9 , 4 34 -6 9

ROBERT L. DOWELL, an in fa n t , who sues by A. L. DOWELL,

h is fa th e r and next fr ie n d , et a l . ,

P l a i n t i f f s - A p p e l l e e s ,

v.

THE BOARD OF EDUCATION OF THE OKLAHOMA CITY PUBLIC

SCHOOLS, e t a l . ,

D efendants,

and

DAVID WEBSTER VERITY, a minor, by and through GEORGE L.

VERITY, h is next fr ie n d , and GEORGE L. VERITY and

ELLEN VERITY, on b e h a lf o f themselves and other persons

s im i la r ly s i tu a te d ,

Intervening D efen dan ts-A ppellan ts

and

TAEJEMA DANZIE, a minor, by and through MRS. A. J. DANZIE,

her next fr ie n d , and MRS. A. J . DANZIE, on b e h a lf o f

themselves and oth er persons s im i la r ly s i tu a te d .

In terven in g -D efen d a n ts-A p p ellan ts

PETITION FOR REHEARING WITH SUGGESTION

FOR REHEARING EN BANC

A p pellees Robert L. Dow ell, e t a l . , r e s p e c t fu l ly request

rehearin g , and suggest the appropriateness o f en banc rehear

ing o f the d e c is io n rendered September 15, 1969, in an order

by C hief Judge Murrah, and C ir c u it Judges B r e ite n ste in and

Hickey. This d e c is io n r e c a lle d the mandate o f th is Court pre

v io u s ly issued fo llo w in g an order o f August 27, 1969, and

vacated orders by the t r i a l court denying in te rv en tio n as

defendants to in terven ors V e r i ty , e t a l . and Danzie, e t a l .

Statement o f the Case

This case in v o lv e s the desegregation o f the p u b lic schoolo

o f Oklahoma C ity , Oklahoma. I t was f i l e d October 9 , 1961, by

ap p ellee Dr. A. L. Dowell, a Negro parent ( la t e r jo in ed by

oth er Negro parents who were allowed to intervene) ag ain st the

e le c te d 5 member Board o f Education o f the Oklahoma C ity Public

Schools and other lo c a l school o f f i c i a l s . The issu e in the

present c o n so lid a ted appeals in volves whether the t r i a l judge

erred in denying in te rv en tio n on August 8 , 1969, to intervenor

V e r i t y , and in denying in terven tio n on August 14, 1969, to

in terven or Danzie. Consideration o f the qu estion s now presented

requ ires a b r i e f resume o f the course o f the l i t i g a t i o n sin ce

1961.

1. Proceedings During 1961-62 b e fo re Statu tory

Three-Judge D i s t r i c t Court.

On October 11, 1961, Chief Judge A. P. Murrah designated

a th ree -ju d g e d i s t r i c t cou rt to hear and decide th is c a se .

C h ief Judge Murrah and D i s t r i c t Judges Bohanon and Daugherty

were d esign ated . A p r e - t r i a l order o f January 26, 1962, framed

the i s s u e s ; i t i s se t out in i t s e n t ir e t y in the appendix h ere to .^

B r i e f ly summarized, i t in dicated that the case involved whether

2

the school board was u n c o n s t i tu t io n a lly continuing r a c ia l segre

gation or had adopted a good f a i t h desegregation plan and was

already in compliance w ith Brown v . Board o f Education, 347

U .S . 483 (1 9 5 4 ) , 349 U .S . 294 (1 9 5 5 ) . The i n v a l i d i t y o f

Oklahoma s ta tu te s requ irin g se g reg a tio n , sought to be en join ed ,

was conceded by the defendants. The th ree-ju d g e court held a

f u l l e v id en tia ry hearing on the m erits on A p r il 3, 1962. On

July 10, 1962, the th ree-ju d g e court entered i t s order, which

is a lso attached as an appendix h e re to . The court ruled that

the th ree-ju d ge court should be d is s o lv e d , but n ev erth e le ss

expressed a view on the m erits f in d in g that the defendants had

not u n c o n s t itu t io n a lly applied the school laws.

2. The Case in 1 9 6 3 -6 4 .

A fte r remand to the re s id e n t judge, and fu rth er pleadings

and h ea rin g s , p l a i n t i f f s f i n a l l y obtained an in ju n ctio n again st

segregation and an order requ irin g a desegregation p lan . The

d e c is io n i s reported at 219 F. Supp. 427 (W.D. O k la . , July 11,

1 9 6 3 ) . In January 1964, the board f i l e d a p o lic y statement

regarding in te g r a t io n . A fte r a hearing the t r i a l court d irected

the board to employ a team o f experts independent o f lo c a l s e n t i

ment to survey the problem o f d eseg rega tion . When the board

d eclin ed to do t h i s , p l a i n t i f f s responded to the c o u r t 's in v i t a

tion and a team o f three w e ll q u a l i f ie d experts were appointed

by the court to study and make a re p o rt . (See d e c is io n at 244

F. Supp. 972 recounting the above events in d e t a i l . )

3

3. The Case in 1 9 6 5 -6 8 .

The expert report was f i l e d and a f t e r an ev id en tia ry hearing

approved by the t r i a l c o u rt . The major fe a tu re s o f the e xp erts '

recommendations (a m a jo rity to m in ority r a c ia l tr a n s fe r o p tio n ,

the p a ir in g o f severa l sc h o o ls , and fa c u lty in te g ra tio n ) were

adopted by the c o u rt . 244 F. Supp. 971 . The d i s t r i c t judge

stayed h is own order pending the b o a rd 's appeal. This Court

affirm ed by a d ivided vote o f 2 -1 on January 23, 1967. 375 F.2d

158. The b o a rd 's p e t i t i o n fo r c e r t i o r a r i was a lso denied, 387

U .S . 931 (May 29, 1 9 6 7 ) . A fte r the appeal the board prepared

a plan embodying the main fea tu res o f the e x p e rts ' plan and the

d i s t r i c t judge perm itted major implementation to be in the

1968-69 school y ear . The t r i a l judge d ire c te d the board to con

tinue fu rth er study and in v e s t ig a t io n and to improve the p lan .

4 . The case in 1969.

On June 12, 1969, the board f i l e d a new plan for desegrega

t io n . A fte r a three day hearing in July 1969, the b o a r d 's new

plan was r e je c te d . The t r i a l judge found that two o f the schools

p re v io u s ly paired were developing a r a c ia l i d e n t i f i c a t i o n as

Negro sch ools and that the s i tu a t io n was d e te r io r a t in g . The

cou rt required the school board to d e v ise a new plan s im ila r to

the s o -c a l l e d Wheat Plan which had been presented during the

t r i a l . The board responded by p resen tin g a plan to enlarge the-

attendance boundaries o f c e r ta in sch ools during the 1969-70 term.

The t r i a l judge then approved th is plan on August 1 , 1969. His

4

order a ls o required a fu rth er long—range plan to be f i l e d by

November 1 , 1969.

Promptly the McWilliams in te rv en o rs , a white fam ily opposed

to the p lan , appealed to th is Court and applied fo r a sta y pend

ing appeal. On August 5, 1969, a panel o f th is Court vacated

the order o f August 1, and remanded the case fo r the t r i a l judge

to con sider the a p p l i c a b i l i t y o f se c t io n 4 0 7 (a ) ( 2 ) o f the C i v i l

Rights Act o f 1964. The d i s t r i c t judge wrote an opinion dated

August 8 , re a ffirm in g h is p r io r a c tio n .

On th is same d a te , August 8 , the V e r ity in te rv en tio n request

was f i l e d , and denied . Judge Bohanon denied in terven tio n as

"Too L a t e . " On August 13, Judge Bohanon again entered h is order

approving the new desegregation p lan . On August 14, the Danzie

in terven tio n v/as requested and Judge Bohanon denied that in te r

vention request the same day.

The Danzie and V e r ity in tervenors then f i l e d n o t ic e s o f

appeal, and sought sta ys pending appeal in th is Court. A panel

o f the court entered an order on August 27 a ffirm in g the den ia l

o f in te rv e n tio n . At the same time the court again vacated the

t r i a l ju d g e 's order.

On September 3, 1969, Mr. J u st ic e Brennan re in sta te d the

d i s t r i c t court order o f August 13 pending d is p o s i t io n o f a p e t i

tion fo r c e r t i o r a r i . The c e r t i o r a r i p e t i t i o n was f i l e d w ithin

the 15 days allowed by J u stic e Brennan and the case is now pend

ing in the Supreme Court as No. 603 , October Term, 1969.

5

On September 2, 1969, the V e r ity and Danzie in tervenors

asked th is Court to recon sider the m atter . A p p e lle e s , regarding

the m atter as governed by Rule 4 0 , F .R .A .P . which fo rb id s answers

to a rehearing p e t i t i o n un less requested , f i l e d no response. On

September 15, 1969, the court entered an order vacatin g the t r i a l

ju d g e 's d e c is io n denying rehearing and d ir e c t in g the t r i a l court

to permit the Danzie and V e r ity in tervenors to be heard on a

motion to modify the August 13 order which, as we have noted,

i s re in sta te d pending the United S ta te s Supreme C o u r t 's co n sid er

ation o f a p e t i t io n fo r c e r t i o r a r i .

On September 11, 1969, the t r i a l judge extended the time

fo r the board to f i l e i t s desegregation plan to March 1970 fo r

elementary sc h o o ls , but denied an exten sion o f the November 1,

1969, d eadlin e fo r secondary sc h o o ls . On September 12, 1969, the

board o f education f i l e d n o t ic e o f appeal from the order o f

August 13, 1969, and the order o f September 12, 1969.

Argument

I . The Court Apparently Overlooked Important Questions in

the In te r p r e ta t io n o f Rule 24, Federal Rules o f C i v i l

Procedure.

Because o f the unusual course o f th is l i t i g a t i o n , th is p e t i

tion fo r rehearing is a p p e l le e s 1 f i r s t opportunity to b r i e f the

m erits o f the appeal. The c o u r t 's August 27 ru lin g follow ed an

emergency hearing on a stay a p p lic a t io n and ap p e llee s had no

opportunity to prepare a b r i e f b e fo re that r u lin g . A pp ellees had

no opportunity to respond to a p p e lla n ts ' request for reco n sid eratio n

6

ill view o f Rule 40(a) , Federal Rules o f A p p e lla te Procedure. We

b e l ie v e that the court overlooked important q u estion s presented

by the a p p e a l.

F i r s t , i t is submitted that the d e c is io n below should be

su stain ed on the ground that the attempted in terven tio n was not

t im ely . This was the ground r e l ie d upon by Judge Bohanon in h is

order o f August 8 , 1969, denying the V e r ity in te r v e n tio n . I t is

not d iscu ssed in e ith e r opinion by th is Court. Where the in t e r

vention comes n early 8 years a f t e r s u i t was f i l e d , i t seems

p la in that a question o f t im e lin e ss is presented . The in terven

tion was sought a f t e r the proceedings in 1969 had progressed

through a p r e - t r i a l h earing , a three day t r i a l , appeal, and remand.

We b e l ie v e that there i s an apparent c o n f l i c t w ith th is Court s

p rio r d e c is io n s ru lin g that a d e c is io n on the t im e lin e ss o f in t e r

vention is w ith in the d is c r e t io n o f the d i s t r i c t court and w i l l

not be d istu rbed absent an abuse o f d is c r e t io n . See Simms v .

Andrews, 118 F.2d 803 (10th C ir . 1 9 4 1 ) ; K e lle y v . Summers, 210

F.2d 665 , 674 (10th C ir . 1 9 5 4 ) ; Miami County Nat. Bank v. B a n c ro ft ,

121 F .2d 921 (10th C ir . 1 9 4 1 ) . See a ls o , 3B M oore's Federal Prac

t i c e , pp. 24-521 e t se q . "In te rv e n tio n a f t e r judgment i s unusual

and not o fte n g r a n te d ." (Moore, supra, at p. 24—5 2 6 .) The ques

tion o f t im e lin e ss should be f u l l y b r ie fe d and argued b efo re the

c o u rt . In view o f the apparent c o n f l i c t with p r io r ru lin g s by

oth er panels o f the Tenth C ir c u it on banc rehearing may be j u s t i f i e d .

Second, Rule 2 4 ( a ) ( 2 ) , upon which in tervenors r e ly for th e ir

claim o f in terven tio n o f r ig h t requ ires that the ap p lica n t claim

7

,r an in teres t r e la t in g to the property or tra n saction which is the

su b ject o f the a c t i o n . " This requirement i s not d iscu ssed by

e ith e r opinion o f th is Court. However, th is C o u rt 's action has

created a c o n f l i c t w ith d e c is io n s o f the F if th C ir c u it in

S t . Helena Parish School Board v . H a l l , 287 F.2d 376, 379 (5th

C ir . 1 9 6 1 ) , c e r t , den. 368 U .S . 830 (1 9 6 1 ) , and S t e l l v . Savannah-

Chatham County Board o f Education, 333 F .2d 55, 60 (5th C ir .

1 9 6 4 ) . In S t . Helena, supra, the F i f t h C ir c u it ruled that white

parents had no r ig h t to intervene in school d esegregation cases

brought ag ain st a lo c a l board. In S t e l l , supra, the court refused

to overturn a t r i a l d e c is io n to permit in te rv e n tio n , ru lin g again

that i t was a d is c r e t io n a r y q u e stio n . For a s im ila r ru lin g see

a lso Blocker v . Board o f Education o f Manhasset, 229 F. Supp.

714 (E.D. N .Y . 1 9 6 4 ) .

We b e l ie v e that the contrary r e s u lt in a case in volvin g the

D i s t r i c t o f Columbia should not be follow ed in that the circum

stances o f the case are d is t in g u is h a b le . See Ilobsen v . Hansen,

44 F .R .D . 18 (D.C. 1 9 6 8 ) , remanded on appeal sub nom. Smuck v .

Hobson, 408 F.2d 175 (D.C. C ir . 1 9 6 9 ) . The Smuck case i s d i s

tin gu ish ab le on se v era l grounds. There, in te rv en tio n on appeal

was perm itted because the school board decided not to appeal. In.

Oklahoma C ity the school board has appealed the disputed August 13

ord er . This s i g n i f i c a n t fa c t may not have come to the a tte n tio n

o f th is Court sin ce the n o tic e o f appeal was f i l e d only three days

b efo re th is C o u rt 's September 15, 1969, d e c i s i o n . In any event,

the le g a l standing o f the Smuck intervenors involved a lim ite d

8

intervenfcion to a sso r t a s p e c i f i c kind, o f le g a l r i g h t : the pro

te c tio n o f the freedom o f action o f the school board. Here, the

V e r ity and Danzie in terven ors a s s e r t a c o n s t i tu t io n a l claim not

to be assigned to sch ools on the b a s is o f race to promote r a c ia l

b ala n ce . We b e l ie v e that th is argument i s w ithout m e rit , and is

indeed so devoid o f substance that the complaint in in te rv en tio n

f a i l s to s t a t e a claim upon which r e l i e f may be granted. In

any event, the same arguments are involved in the phase o f th is

case which is now pending on p e t i t io n fo r c e r t i o r a r i in the

Supreme Court o f the United S t a t e s .

The t r i a l judge has had no opportunity to ru le on whether

the V e r ity and Danzie com plaints in in terven tio n can su rvive a

motion to d ism iss . This C o u rt 's order o f September 15 might be

read as deciding those qu estion s sub s i l e n t i o by assuming the

n e c e s s ity fo r the t r i a l court e n te rta in in g a motion to amend the

August 13, 1969, ord er.

Third, the court did ru le that the in tervenors were not

adequately represented by the McWilliams in te rv en o rs . This f a i l s

to address whether th e ir in te r e s t s are adequately represented by

the school board which has appealed the same order. Representa

tion by the governmental a u th o r it ie s i s considered adequate in

the absence o f gross n eg ligen ce or bad fa i t h on th e ir p a r t . "

3B Moore's Federal P r a c t ic e , pp. 2 4 -1 9 4 . Blocker v . Board o f

Education o f Manhasset, supra; S t . Helena Parish School Board v .

H a l l , supra.

9

II. A Judge o f the Panel Which Decided the Case Was D isqu al

i f i e d under the P rovisions o f 28 U .S .C . §47 Because He

P reviou sly Heard and Decided Issu e s Involved in the

Cause as a Member o f a S ta tu to ry Three-Judge D i s t r i c t

C o u rt.

I t i s r e s p e c t f u l ly submitted that the p re sid in g judge o f the

panel which decided th is case , Chief Judge A. P. Murrah, was

d is q u a l i f i e d to p a r t ic ip a t e by 28 U .S .C . §47 which p ro v id e s :

No judge s h a l l hear or determine an appeal

from the d e c is io n o f a case or issu e tr ie d

by him.

Judge Murrah1s p a r t ic ip a t io n in the 1961-1962 th ree-ju dge

cou rt proceedings i s described in the Statement, supra. The r e l e

vant orders in d ic a t in g the issu es framed fo r t r i a l and the issu es

a c tu a l ly decided are appended h e re to . See p r e t r i a l order o f

January 26, 1962, and order o f July 10, 1962. Quite p la in ly the

f u l l range o f i s s u e s - - t h e case as a whole— was tr ie d b efo re the

three—judge co u rt . Although that court was d ou btfu l o f i t s

ju r i s d ic t io n and u lt im a te ly decided i t had no j u r i s d i c t i o n , i t

expressed a view on the b a s ic m erits o f the case s ta t in g that the

school board was not g u i l t y o f m aintaining an u n c o n s t itu t io n a lly

segregated school system.

A judge who has once heard the cause on the m erits in the

t r i a l court i s d i s q u a l i f i e d from hearing an appeal in the same

cause, which in volves in any degree matters upon which he had

occasion to pass in the lower c o u r t . " (Emphasis added.)

v . D illin gh a m , 174 U .S . 153, 157 (1 8 9 9 ) ; Rexford v . Brunswick-

Balke-C o1lender Co. , 228 U .S . 339 (1 9 1 3 ) ; Wm. Cramp & Sons S. &

E. B. Co. v . In te r n a tio n a l C u rtis Marine Turbine C o ., 228 U .S .

10

645 (1 9 1 3 ) ; American Construction Co. v. J a c k so n v ille T. & K. W.

Railway Co. , 148 U .S . 372, 387 (1 8 9 3 ) ; c f . United S ta te s v .

Emholt, 105 U .S . 414 (1 8 8 2 ) . The t e s t under se c t io n 47 is a

s t r i c t one. Section 47 is "not r e s t r i c t e d to the case o f a

ju d g e 's s i t t i n g on a d ir e c t appeal from h is own d ecree , or upon

a s in g le q u e s t io n ." (Moran, supra, 174 U .S . at 1 5 7 .) "A Judge

who has sa t at the hearing below o f a whole cause at any stage

th ereof i s undoubtedly d i s q u a l i f ie d to s i t in the c i r c u i t court

o f appeals at the hearing o f the whole cause at the same or at

any l a t e r s ta g e " ( i b i d . ) .

The Supreme Court has twice held that even a consent o f the

p a r t ie s cannot make a d i f fe r e n c e and j u s t i f y f a i l u r e to comply

w ith s e c t io n 4 7 . Thus, i t cannot m atter that the o b je c t io n was

not h e re to fo re ra ise d in th is Court. Rexford v . Brunswick-

B alke-C ollen der Co. , 228 U .S . at 344; Wm, Cramp & Sons S. & E.

B. Co. v. In te rn a tio n a l C u rtis Marine Turbine Co. , 228 U .S . a t

650 . In any event, a p p e lle e s ' f a i lu r e to o b je c t i s p e r fe c t ly

understandable in that none o f a p p ellee^ present counsel p a r t i c i

pated in the 1961—62 proceedin gs. One o f a p p e llee s counsel in

that proceeding, John Green, E sq ., became an A s s is ta n t United

S ta te s Attorney (see 219 F. Supp. at 4 2 8 ) , and the other

(Mr. U. S. Tate) i s deceased.

The ru le o f se c t io n 47 is q u ite s t r i c t . But as Mr. J u stic e

Black observed in a d i f f e r e n t , but not unrelated c o n te x t , in

Re Murchison, 349 U .S . 133, 136 (1 9 5 5 ) , such a ru le "may sometimes

]^ar t r i a l by judges who have no actu al b i a s , but the rule helps

11

In any event, the in te n tio ns a t i s f y "th e appearance o f j u s t i c e . "

o f Congress i s to require that the court o f appeals "be c o n s t i

tuted o f judges uncommitted and uninfluenced by having expressed

or formed an opinion in the court o f f i r s t in s t a n c e ." Moran v .

D illin gh a m , 174 U .S . 153, 156 -157 (1 8 9 9 ) . Judge Murrah expressed

a view on the m erits in the July 10, 1962, ord er. Ihe Supreme

Court precedents require a rehearing b efo re a court o f appeals

c o n stitu te d in compliance with se c t io n 47 .

This same qu estion in volv in g se c t io n 47 i s now pending in

the United S ta te s Supreme Court in the p e t i t io n fo r c e r t i o r a r i

seeking review o f th is C o u rt 's d e c is io n o f August 27, 1969,

vacatin g the t r i a l court order o f August 13, 1969.

R e sp e c tfu lly submitted,

JACK GREENBERG

JAMES M. NABRIT, I I I

NO RMAN J . CHACHKIN

10 Columbus C ir c le

New York, New York 10019

JOHN W. WALKER

1820 West 13th S tre e t

L i t t l e Rock, Arkansas 72202

ARCHIBALD B. HILL, JR.

407 North Durland

Oklahoma C ity , Oklahoma 73104

Attorneys fo r A pp ellees Dowell, et a l .

CALVIN W. HENDRICKSON

2401 F ir s t N ational Building

Oklahoma C ity , Oklahoma 73102

Attorney for Appellees Sanger, e t a l .

12

CERTIFICATE OF SERVICE

I hereby c e r t i f y that on the 24th day o f September, 1969,

I served a copy o f the foregoin g P e t it io n fo r Rehearing with

Suggestion fo r Rehearing en banc on attorneys fo r in tervening

d e fe n d a n ts -a p p ella n ts and on

o f same in the United S ta tes

addressed to the fo l lo w in g :

V. P. Crowe, Esq.

George S. Guysi, Esq.

5th F lo o r , 100 Park A ve . Bldg.

Oklahoma C ity , Okla. 73102

George F. Short, Esq.

2401 F ir s t N ational Bldg.

Oklahoma C ity , Okla. 73102

Norman E. Reynolds, Esq.

2808 F ir s t N ational Bldg.

Oklahoma C ity , O kla. 73102

Attorneys fo r McWilliams

Intervenors

J. Harry Johnson, Esq.

2105 F ir s t N ational Bldg.

Oklahoma C ity , Okla. 73102

Attorney for the Board o f

Education o f Oklahoma C ity

Public Schools

defendants by d e p o sitin g a copy

a i r m ail, postage prepaid ,

George L. V e r i ty , Esq.

Brown, V e r ity & Brown

2220 F ir s t N ational Bldg.

Oklahoma C ity , Okla. 73102

Attorney for V e r ity , e t

a l and D anzie, e t a l .

W illiam G. Smith, Esq.

405 In v e sto rs C a p ita l Bldg.

Oklahoma C ity , Okla. 73102

Robert H. Warren, Esq.

325 Robert S. Kerr Ave.

Oklahoma C ity , Okla. 73102

___

James M. N abrit, I I I

Attorney fo r Plain t i f f s - A p p e l le e s

45a

(Filed July 10, 1962)

Obder D issolving T hree-Judge Court

[Title Omitted]

This action was brought by Robert L. Dowell, a minor

child of the negro race by and through his father as next

friend, and as a class action in boliall of all others similarly

situated, against the Board of Education of the Oklahoma

City Public Schools, Independent District No. 89, and the

indi\ iduals; in their capacities as set forth in the caption.

The original and amended complaint of plaintiff, insofar

as this order is concerned, may be considered as setting

forth the same complaints and asking for the same relief.

The amended complaint seeks to strike down all Consti

tutional and statutory provisions of the State of Oklahoma

relating to segregation of the races in the public schools.

Defendants admit, in their answer, that all of these Consti

tutional and statutory provisions are unconstitutional. The

real question posed by the pleadings is the application

by defendants of Section 4-22 of Title 70, Oklahoma Stat

utes Annotated. Plaintiff admits that this section is Con

stitutional on its face, but contends that it is unconstitution

ally applied. Defendants, by their answer, state that all

actions taken by them were under the authority of this

statute only, and that it is not being and has not been

unconstitutionally applied.

The jurisdiction of the Court is invoked pursuant to Title

28 U.S. Code, Section 1343 (3) as a suit in equity authorized

by Title 42 U.S. Code, Section 1983, seeking to redress the

deprivation, under color of law, regulation, custom and

usage, of rights, privileges and immunities secured by the

Order Dissolving Three-Judge Court

46a

due process and equal protection clauses of the United

States Constitution, 14th Amendment, Sec. 1, and rights

protected by Title 42 U.S. Code, Sections 19S1 and 1983.

Plaintiff contended that the subject matter of this action

is cognizable by a statutory three-Judge District Court,

Title 28 U. S. Code, Sections 2281 and 2284, being a civil

action for permanent injunction, and to enjoin and restrain

the enforcement, operation and execution of a State statute.

Under the complaint, seeking the relief above mentioned,

Honorable Luther Bohanon, District Judge for the West

ern, Eastern and Northern Districts of Oklahoma, made the

initial requisite declaration that a substantial Federal ques

tion was involved, notified the Honorable Alfred P. Murrah,

Chief Judge, Tenth Circuit Court of Appeals of the filing

of the case. A three-Judge District Court, comprised of

Chief Judge Murrah, Honorable Fred Daugherty and

Honorable Luther Bohanon, District Judges, was consti

tuted by order of Chief Judge Murrah.

The three-Judge Court as so constituted, heard the evi

dence of all the parties concerned in order that the matter

would not be delayed in the event it was finally determined

that a three-Judge Court had jurisdiction.

Section 4-22 Title 70, Oklahoma Statutes Annotated, au

thorizes Boards of Education “ to designate the schools to

be attended by the children of the District.” The evidence

shows that the plaintiff came from a dependent school dis

trict, where there was no high school, into the defendant

school district, and made his election to attend Douglass

High School. After attending Douglass High School for

one year, he then made an application to be transferred

from Douglass High School to Northeast High School be

cause a course of study offered at Northeast High School

was not available at Douglass High School, and this trans-

Order Dissolving Three-Judge Court

47a

fer was permitted on the condition that the plaintiff enroll

in this course of study and diligently pursue the same.

The plaintiff’s evidence failed to show that the above

mentioned statute is or was unconstitutionally applied by

the defendants.

Under the pleadings and evidence the Court is of the

opinion that there is no justiciable controversy presented

as to any of the constitutional or statutory provisions set

out in the plaintiff’s first amended complaint, and there

remained only for determination the cpiestion relating to

defendant’s application of the above mentioned statute.

There Avas no evidence to show that the unconstitutional

proA’isions of the Oklahoma Constitution and the unconsti

tutional statutes of Oklahoma relating to segregation of

the races in public schools have been used and there is

no controversy Avith respect thereto and nothing to strike

doAvn. Under the pleadings there Avas only the issue as

to defendant’s application of Section 4-22 Title 70, Okla

homa Statutes Annotated. This issue is a factual one and

does not address itself to a three-judge Court.

It further appears from the evidence that there has been

no order made or promulgated by the defendants acting

under the above statute, within the purvieAv of 28 U. S.

Code Section 2281, which the plaintiff presents or points

out to be unconstitutional by discriminating against the

plaintiff and his class by reason of race or color.

It is always the duty of any Court to inquire into its

jurisdiction, and in vieAV of Avhat has been above set forth

this Court holds that it is Avithout jurisdiction, and is of

the opinion that the subject matter of this suit is properly

one for determination by one Judge. The case having

been originally assigned to Honorable Luther Bohanon,

District Judge, it is hereby reassigned to him for further

Order Dissolving Three-Judge Court

46a

I

9

3

|

i

i

Ia

i

i1

Order Dissolving Tliree-Judge Court

due process and equal protection clauses of the United

States Constitution, 14th Amendment, Sec. 1, and rights

protected by Title 42 U.S. Code, Sections 1981 and 1983.

Plaintifi contended that the subject matter of this action

is cognizable by a statutory three-Judge District Court,

Title 28 U. S. Code, Sections 2281 and 2284, being a civil

action for permanent injunction, and to enjoin and restrain

the enforcement, operation and execution of a State statute.

Under the complaint, seeking the relief above mentioned,

Honorable Luther Bolianon, District Judge for the West

ern, Eastern and Northern Districts of Oklahoma, made the

initial requisite declaration that a substantial Federal ques

tion was involved, notified the Honorable Alfred P. Hurrah,

Chief Judge, Tenth Circuit Court of Appeals of the filing

of the case. A three-Judge District Court, comprised of

Chief Judge Hurrah, Honorable Fred Daugherty and

Honorable Luther Bolianon, District Judges, was consti

tuted by order of Chief Judge Hurrah.

The three-Judge Court as so constituted, heard the evi

dence of all the parties concerned in order that the matter

would not be delayed in the event it was finally determined

that a three-Judge Court had jurisdiction.

Section 4-22 Title 70, Oklahoma Statutes Annotated, au

thorizes Boards of Education “ to designate the schools to

be attended by the children of the District.” The evidence

shows that the plaintiff came from a dependent school dis

trict, where there was no high school, into the defendant

school district, and made his election to attend Douglass

High School. After attending Douglass High School for

one year, he then made an application to be transferred

from Douglass High School to Northeast High School be

cause a course of study offered at Northeast High School

was not available at Douglass High School, and this trans-

' ' - V ' r -r

47a

Order Dissolving Tliree-Judge Court

fer was permitted on the condition that the plaintiff enroll

m this course of study and diligently pursue the same.

Ihe plaintiff’s evidence failed to show that the above

mentioned statute is or was unconstitutionally applied by

the defendants. J

Under the pleadings and evidence the Court is of the

opinion that there is no justiciable controversy presented

as to anj of the constitutional or statutory provisions set

out m the plaintiff’s first amended complaint, and there

remained only for determination the question relating to

pendant’s application of the above mentioned statute.

1 here was no evidence to show that the unconstitutional

provisions of the Oklahoma Constitution and the unconsti

tutional statutes of Oklahoma relating to segregation of

the races in public schools have been used and there is

no controversy with respect thereto and nothing to strike

down Under the pleadings there was only the issue as

to defendant’s application of Section 4-22 Title 70, Okla

homa Statutes Annotated. This issue is a factual one and

does not address itself to a three-Judge Court.

It further appears from the evidence that there has been

no order made or promulgated by the defendants acting

under the above statute, within the purview of 28 U. S.

Code Section 2281, which the plaintiff presents or points

out to be unconstitutional by discriminating against the

plaintiff and his class by reason of race or color.

. 11 is always the ^ t y of any Court to inquire into its

jurisdiction, and m view of what has been above set forth

this Court holds that it is without jurisdiction, and is of

the opinion that the subject matter of this suit is properly

one for determination by one Judge. The case having

been originally assigned to Honorable Luther Bohanon,

District Judge, it is hereby reassigned to him for further

—y HQ Mil IJij ■g ■ \pjgm»I m IMMWTOWi

48a

procedings, and this three-Judge statutory Court is hereby

dissolved.

E ntered this 10 day of July, 19G2.

/ s / A le red P. M urrah

A lfred P. M urrah, Chief Judge,

Tenth Circuit Court of Appeals

/ s / L uther B ohanon

United States District Judge

/ s / F red Daugherty

United States District Judge

Order Dissolving Three-Judge Court

tiiavifiarwftiiSi •„ • *ltU,w ,1

49a

[Title Omitted]

A dmitted F acts

It is agreed that the defendant, Independent School Dis-

dist • f° ■ +°f ° klahoma County> is an independent school

tl f f nC T ! US UDder thG laWS ° f the State of Oklahoma;

Phi C B thiS aCti° n ° tt0 F - Thompson,Phil C. Bennett, AY illiam F. Lott, Eloise Welch (otherwise

known as Mrs. Warren F. Welch), and Luke F. Skaggs

S ch oll1V ! ° V lu members 0f the Board of the Defendant

School District; that since the filing of this action Foster

Estes has succeeded Luke F. Skaggs, Jr., as member of

said Board and has been by the order of this Court sub-

Jack F P a, def?lldant in the «toad of said Skaggs; that

i t l ' P o 'ker 18 Supermtendent of the Schools of the

Defendant School District and that M. J. Burr is Assistant

Superintendent of such schools.

It is agreed that the plaintiffs are a father and minor

son, citizens of the United States and the State of Okla-

oma, and that they are members of the Negro race; that

minor plaintiff resides with his parents in a school

strict adJoining the Defendant Independent School Dis-

uct Lo. 89 of Oklahoma County (last named school dis-

tnct 89 is mentioned hereinafter as Defendant School Dis-

tu ct ); that the school district of the residence of the plain

tiff does not, but the Defendant School District does offer

coupes of instruction above the 8th grade level; that the

nnnor plmntiff is a pupil of the 10th grade; that the minor

plaintiff made application to the County Superintendent of

ols of Oklahoma County that such minor plaintiff be

ransferred from his home school district to the defendant

school district for the reason that the home district of the

Pretrial Order and Stipulations

50a

minor plaintiff did not offer instruction above the 8th

grade level; that the first of said applications was made for

the school year of 1960-61 Exhibit “1” and that the second

was made to cover the school year of 1961 and 1962; Ex

hibit “ 2” ; that each of said applications was granted by

the County Superintendent of Schools of Oklahoma County

as is evidenced by the copies of such transfers which have

been furnished to and filed with the Clerk of this Court,

which copies are exact copies of the originals of said ap

plications for and grant of such transfers, and that the

same may be introduced in evidence without further identi

fication. That after the granting of said application for the

school year 1960-61 the minor plaintiff entered Douglass

High School, one of the schools of the defendant school dis

trict that is attended solely by pupils of the Negro race.

It is agreed that after the granting of the transfer to

the minor plaintiff for the year 1961-62 that the plaintiffs

made application to the defendant school district for per

mission to attend as a pupil, Northeast High School which

is high school of the defendant school district, located in

an area that is predominately populated by members of

the white race and is attended by both Negroes and white

children.

Thereafter the plaintiffs and their attorney, Mr. Green,

appeared before the Board of Education of the Defendant

School District and after discussion of said request a

minute was made of said meeting, a copy of which minute

has been filed with the Clerk of this Court, and it is stipu

lated that said copy of said minute may be introduced in

evidence without further identification, Exhibit “3” .

It is agreed that the Board of the Defendant School Dis

trict by a unanimous vote adopted on August 1, 1955, the

resolution of desegregation, a copy of which is attached

Pretrial Order and Stipulations

ftyftViBiiiitalii*l > ^ - - ^ j i i ( '1iiirriMif,l < ii. •

Pretrial Order and Stipulations

hereto as Exhibit ”4” , which copy may be introduced in

evidence without further identification.

It is agreed that thereafter the Board of the Defendant

School District adopted a map, a copy of which has been

delivered to the Clerk of the Court, which map showed what

is commonly called attendance areas, that is, it showed the

area of the school district surrounding various schools

and the Board provided that an individual within the at

tendance area of a school be a pupil of and attend the

school of that particular area, Exhibit “5” .

It is agreed that there are now white children of high

school age who live within the Douglass High School at

tendance area that are not attending Douglass High School

and that there are Negro children now attending Douglass

High School who live outside of the Douglass attendance

area.

51a

S tipulation’s

The parties to this action stipulate and agree as to the

following for the purpose of the trial of the issues. Each

party, however, reserves the right to object to the intro

duction of any evidence as to any fact on the ground of

competence, relevancy, or materiality.

1.

It is stipulated and agreed by plaintiff and defendant

that there are no amendments to be made to plaintiff’s

first amended complaint and that there are no amendments

or additions to be made to the defendant’s answer to plain

tiff’s first amended complaint.

- - m^ « cc>.'>«>fcrflfc'Jliill'ffl V'l!' i

I

••If

. -$

1

;'3:•!

A

52a

Pretrial Order and Stipulations

2 .

Defendant stipulates and agrees that plaintiff has served

proper live day notice on the Governor of the State of

Oklahoma and the Attorney General of the State of Okla

homa as provided by law for a Three Judge Federal Court

proceeding.

3.

It is stipulated and agreed between plaintiff and defen

dant that this Court has jurisdiction of the subject matter

of this case.

A. The defendant contends as stated in their amended

answer that the plaintiffs are not entitled under the

law and the facts in this case, to have a three Judge

Court convened to hear this matter.

B. Planitilfs contend that the subject of this lawsuit

is cognizable by a statutory three Judge Court and

that a three Judge Court must determine its jurisdic

tion.

• 4.

It is stipulated and agreed by plaintiff and defendant

that the following provisions of the Oklahoma constitution

and the State statutes of the State of Oklahoma as are

now carried on the statute books of the State of Oklahoma,

and being unrepealed, are unconstitutional under the Con

stitution of the United States of America by reason of the

decisions of the Supreme Court in the Brown case of May

17, 1954 and subsequent segregation opinions, to-wit:

(1.) Declare that provision of Section 5, Article I, of

the Constitution of Oklahoma, which reads: “And pro-

**■»!> «* •? f •V’ "wrf ** .r - J y*» *-mmi

53a

vided, further, that this shall not be construed to prevent

the establishment and maintenance of separate schools for

white and colored children,” is unconstitutional and void;

(2.) Declare that Section 3 of Article XIII of the Con

stitution of Oklahoma, which reads:

“Separate schools for white and colored children with

like accommodations shall be provided by the Legislature

and impartially maintained. The term ‘colored children’

as used in this Section, shall be construed to mean children

of African descent. The term ‘white children’ shall include

all other children,” to be unconstitutional and void;

(3.) This provision hereafter treated.

(4.) Declare Section 5-1 of Title 70, Oklahoma Statutes,

Separation of races Impartial facilities. “The public schools

of the State of Oklahoma shall be organized and main

tained upon a complete plan of separation between the

white and colored races with impartial facilities for both

races.” Laws 1949, p. 536, Art. 5, Sec. 1, unconstitutional

and void;

(5.) Declare Section 5-2 of Title 70, Oklahoma Statutes,

definitions. “The term ‘colored,’ as used in the preceding

section, shall be construed to mean all persons of African

descent who possess any quantum of Negro blood, and the

term ‘white’ shall include all other persons. The term

‘public school’ within the meaning of this Article shall in

clude all schools provided for or maintained, in whole or

in part, at public expense.” Laws 1949, p. 536, Art. 5,

Sec. 2, unconstitutional and void;

(6.) Declare Section 5-3, of Title 70, Oklahoma Statutes,

separate school defined—Designation—Membership of dis-

Pretrial Order and Stipulations

I vX-M -t^rV .

i

A

rA

•X■;l

»

/$

■ >

qASM

yc-l

mm-jiM

trict board. “ The separate school in each district is hereby

declared to be that school in said school district of the

race having the fewest number of children in said district.

Provided, that the county superintendent of schools shall

have authority to designate what school or schools in the

school district shall be the separate school or schools and

which class of children, either white or colored, shall have

the privilege of attending such separate school or schools

in said school district. Members of the district school

board shall be of the same race as the children who are

entitled to attend the school of the district, not the separate

school.” As amended Laws 1955, p. 423, Sec. 15, uncon

stitutional and void ;

(7.) Declare Section 5-4, of Title 70, Oklahoma Statutes,

teacher permitting child to attend school of other race.

“Any teacher in this state who shall wilfully and know

ingly allow any child of the colored race to attend the

school maintained for the white race shall be deemed

guilty of a misdemeanor and upon conviction thereof shall

be fined in any sum not less than ten dollars ($10.00)

nor more than fifty dollars ($50.00), and his certificate

shall be cancelled and he shall not have another issued

to him for a term of one (1) year.” Laws 1949, p. 537,

Art. 5, Sec. 4, to be unconstitutional and void;

(8.) Declare Section 5-5, of Title 70, Oklahoma Statutes,

maintaining or operating institution for both races. “ It

shall be unlawful for any person, corporation or associa

tion of persons to maintain or operate any college, school

or institution of this State where persons of both white

and colored races are received as pupils for instruction,

and any person or corporation who shall operate or main

tain any such college, school, or institution in violation

54a

Pretrial Order and Stipulations

i

I

55a

hereof shall be deemed guilty of a misdemeanor and upon

conviction thereof shall be fined not less than one hundred

dollars ($100.00) nor more than five hundred dollars

($500.00), and each day such school, college or institution

shall be open and maintained shall be deemed a separate

offense.” Laws 1949, p. 537, Art. 5, Sec. 5, to be uncon

stitutional and void;

(9.) Declare Section 5-6, of Title 70, Oklahoma Statutes,

teaching in institution receiving both races. “Any instructor

who shall teach in any school, college or institution where

members of the white and colored race are received and

enrolled as pupils for instruction shall be deemed guilty

of a misdemeanor, and upon conviction thereof, shall be

fined in any sum not less than ten dollars ($10.00) nor

more than fifty dollars ($50.00) for each offense, and each

day any instructor shall continue to teach in any such col

lege, school or institution shall be considered a separate

offense.” Laws 1949, p. 537, Art. 5, Sec. 6, to be uncon

stitutional and void;

(10.) Declare Section 5-7, of Title 70, Oklahoma Statutes,

white person attending institution receiving colored pupils.

“It shall be unlawful for any white person to attend any

school, college or institution where colored persons are

received as pupils for instruction, and anyone so offending

shall be fined not less than five dollars ($5.00) nor more

than twenty dollars ($20.00) for each offense, and each

day such person so offends as herein provided shall be

deemed a distinct and separate offense: Provided nothing

in this Article shall be construed as to prevent any private

school, college or institution of learning from maintaining

a separate or distinct branch thereof in a different locality.”

Laws 1949, p. 537, Art. 5, Sec. 7, to be unconstitutional

and void;

Pretrial Order and Stipulations

56a

(11.) Declare Section 5-8, of Title 70, Oklahoma Statutes,

support and maintenance of Separate Schools. “ The annual

budget of each school district maintaining separate schools

for white and colored children shall provide for the sup

port and maintenance of both the school or schools for the

white children and the school or schools for the colored

children.” As amended Laws 1955, p. 423, Sec. 16, to be

unconstitutional and void ;

(12.) Declare Section 5-11, of Title 70, Oklahoma Stat

utes, transfer of pupils. “ When any school district having

both white and colored children of school age does not

maintain schools for both races, the county superintendent

of schools shall transfer the children of the race for which

a school is not maintained to a school of their own color

in another district when the same can be done with the

consent of their parents, guardians or custodians, or with

out such consent when such children can be transferred

without compelling them to walk more than one and one-

half miles to attend such school; provided, that such chil

dren may be required to travel more than one and one-

half (IV2 ) miles when proper provision is made for the

transportation of such children, and the consent of the

parents, guardian or custodian of any child being required

to travel more than one and one-half (IV2 ) miles shall

not be required when such transportation is furnished.” As

amended Laws 1955, p. 424, Sec. 18, to be unconstitutional

and void;

Pretrial Order and Stiimlations

5.

It is further stipulated between plaintiff and defendant

in relation to the foregoing articles of the Oklahoma Con

stitution and sections of the Oklahoma statutes that the

a ysaapy

57a

plaintiff will offer no oral testimony showing a use of the

said Articles of the Oklahoma Constitution and sections of

the Oklahoma state statutes in the operation of defendant

schools.

A. Except plaintiff reservies the right to contend that

the defendants have continued to operate and are

now operating segregated schools under said statutes

or otherwise contrary to the decisions of the Supreme

Court of the United States, under said designated

Articles of the Constitution and statutes.

Plaintiffs’ PriuCipaa Issue

(Item 3, Above Referred To)

Oklahoma Statutes, Title 70, Section 4-22 authorizes

Boards of Education in part as follows: “ To designate the

schools to be attended by the children of the district.”

Plaintiffs say the foregoing is unconstitutional as applied

to and used by defendants as to these plaintiffs and as to

members of the class of persons that plaintiffs represent

who are similarly situated because of their race and color.

The defendants’ contention is that the last mentioned

statute is constitutional and that any question that can be

raised in this cause by the plaintiffs as to the application

and use of said statute in this matter is purely factual.

Plaintiffs’ Proof

Plaintiff may offer such proof as he may have showing

a trend of conduct during the preceding five years prior to

September, 1960, establishing the grievance set out in the

complaint, and in this connection, plaintiff will have the

following witnesses:

Pretrial Order and Stipulations

i5-i

•:i

I

Pretrial Order and Stipulations

A 0klnT' Hign0n’ Superintendent Of Schools, Oiaahoma County;

^ S ch o o l^ ’ ASSIStaUt SuPeri*tendent of Defendant

Nora Belle Oringdorff.

-T. P. Cherry, Oklahoma City;

M. 0. McDaniels, Douglass High School;

P. D. Moon, former Principal, Douglass High School;

Ira D. Hall, Page Elementary School;

rs. Ruby Fleming, "Woodson Elementary School;

B. V. Watkins, Dunbar Elementary School;

William Johnson, Creston Hills Elementary School;

MSchool;y M° Ulder’ PfinCipa1’ Elementary

Delbert Burnett, Culbertson Elementary School;

Mrs. Hazel Kibler, Lincoln Elementary School;

Lederle Scott;

Mrs. Etoise Flenoid, Oklahoma City;

John Flenoid, Oklahoma City;

Gloria Burse.

58a

I

59a

Pretrial Order and Stipulations

D efendants’ Proof

Defendants’ conception of the issue in tills cause is not

that set forth by the plaintiffs, but that under the segrega

tion opinions of the Supreme Court of the United States,

the province of this Court is to determine whether or not

the defendants have adopted a plan which is a good faith

attempt to comply with the said decisions on desegregation

as rapidly as possible, all things being considered; and that

by those decisions the local School Board has imposed on

it the duty of devising such a plan, and the contention will

be that the plan adopted by the Defendant District is such

reasonable plan which entitles it to be approved by this

Court, and that all complaints by the plaintiffs are made of

actions honestly and in good faith done under said plan.

Witnesses who may be called to testify in addition to the

defendants are:

Nellie Melton and John C. Pearson, Jr., former mem

bers of the School Board;

and in general personnel employed by the School District,

all of whom, in the belief of the defendants, have been

named as witnesses by the plaintiffs.

T rial D ate

On information from Judge Murrah’s office and Judge

Daugherty’s office that they will be available for April 3,

1962, it is stipulated and agreed by all parties concerned

that the trial of this case will commence on April 3, 1962

at the hour of 9 :30 a.m. and continue thereafter until sub

mitted.

•• **ef.. . r v y

60a

Pretrial Order and Stipulations

E xhibits

Attached is a map or plat showing Pleasant Hill District

D-45, and attendance area covering Douglass High School

and Northeast High School, which is admitted in evidence

and made a pgrt of this stipulation, being Exhibit “B” .

Dated this 26th day of January, 1962.

L uther B ohanon

Luther Bohanon, U. S. District Judge

A pproved:

John E. Green

For the Plaintiff

W. A. L ybrand

For the Defendant.

>V * ' •• t -" • r <*• • •«•■*****-* • -■ .rr -y rn y i*