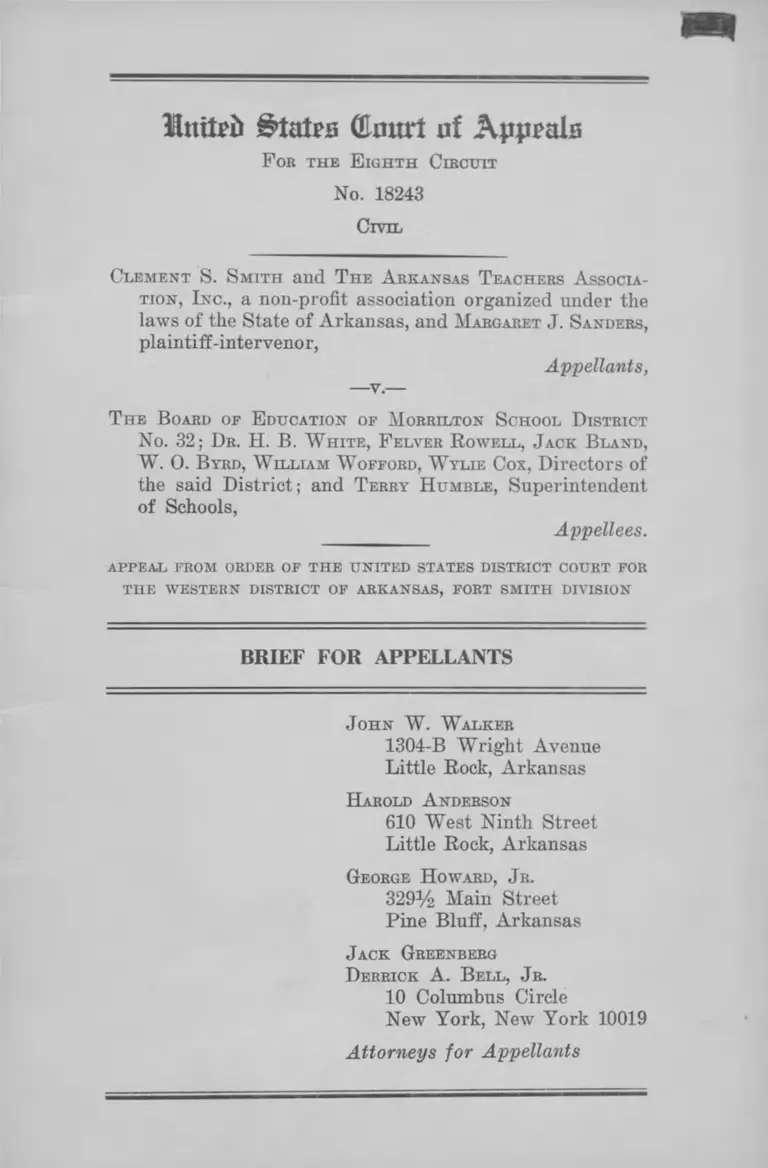

Smith v Morrilton School District BOE Brief for Appellants

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1966

39 pages

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Smith v Morrilton School District BOE Brief for Appellants, 1966. 05312eb5-c49a-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/3985a9b4-c441-4a0c-acb8-b62fba4de69a/smith-v-morrilton-school-district-boe-brief-for-appellants. Accessed February 22, 2026.

Copied!

United States Qlnart of ApppaIs

F ob th e E igh th C ibcuit

No. 18243

C ivil

Clem ent S. S m ith and T he A bkansas T eachebs A ssocia

tion , I nc ., a non-profit association organized under the

laws of the State of Arkansas, and M abgabet J. S andebs,

plaintiff-intervenor,

Appellants,

—v.—

T he B oard of E ducation of M orbilton S chool D istrict

No. 32; D r . H. B. W h ite , F elver R owell, J ack B land ,

W . 0 . B yrd, W illiam W offord, W ylie C ox, Directors of

the said District; and T erry H umble , Superintendent

of Schools,

Appellees.

APPEAL FROM ORDER OF TH E U N ITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR

TH E W ESTERN DISTRICT OF ARKANSAS, FORT SM IT H DIVISION

BRIEF FOR APPELLANTS

J ohn W . W alker

1304-B Wright Avenue

Little Rock, Arkansas

H arold A nderson

610 West Ninth Street

Little Rock, Arkansas

George H oward, J r .

329% Main Street

Pine Bluff, Arkansas

J ack Greenberg

D errick A. B ell , Jr.

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

Attorneys for Appellants

I N D E X

PAGE

Statement of the Case ...................................................... 1

Statement of Points to Be A rgued................................ 16

A rgument

Preliminary Statement .................................................. 18

I. Plaintiffs, Under Generally-Applied Rules of

Proof in Racial Discrimination Cases, Suffi

ciently Proved Their Dismissal by the Board

Was Racially Motivated and Violated Consti

tutionally-Protected Rights .................................. 22

II. School Boards Effecting Faculty Reductions

Required by Desegregation Must Evaluate All

Teachers, Both Incumbent and Applicants, by

Valid, Objective and Ascertainable Standards .. 29

C onclusion ......................................................................... 32

T able of Cases

Adler v. Board of Education, 342 U.S. 485, 493

(1952) ............................................................................. 16,22

Alston v. School Board of City of Norfolk, 112 F.2d

992, 997 (4th Cir. 1940), cert, den., 311 U.S. 693 ....2,16,22

Avery v. Georgia, 345 U.S. 559 (1953) ........................ 16,25

Bailey v. Patterson, 323 F.2d 201 (5th Cir. 1963) .......16, 27

Bonner v. Texas City Independent School District, Civ.

No. 65-G-56 (S.D. Tex. 1965) ........................................ 20

Bradley, et al. v. School Board of City of Richmond,

317 F.2d 429 (4th Cir. 1963) ................................ '.... 17,29

11

Bradley v. School Board of Richmond,------U .S .------- ,

15 L.ed. 2d 187 (1965) .................................................... 18

Brooks v. School District of Moberly, Mo., 267 F.2d

733 (8th Cir. 1959) ..........................................15,16,17,20,

22, 23, 27, 30

Brown v. Board of Education, 347 U.S. 483 (1954) 18

Brown v. Board of Education, 349 U.S. 294 (1955) 18

Bryan v. Alston, 148 F.Supp. 563, 567 (E.D.S.C. 1957)

(dissent) .........................................................................16, 22

Buford v. Morganton City Board of Education, 244

F.Supp. 437 (W.D.N.C. 1965) ...................................... 19

Calhoun v. Latimer, 321 F.2d 302 (5th Cir. 1963)

vacated 377 U.S. 263 (1964) ........................ _..... 17,29,31

Chambers v. Hendersonville City Board of Education,

245 F.Supp. 759 (W.D.N.C. 1965), on appeal to

Fourth Circuit (No. 10,379) ........................................ 19

Christmas v. Board of Education of Harford County,

Md., 231 F.Supp. 331 (D.Md. 1964) .........16,19,22,26,27

Cooper v. Aaron, 358 U.S. 1, 16 (1958) ...................... 17,30

Cramp v. Board of Public Instruction, 368 U.S. 278

(1961) ......................v...................................................... 16,22

Dean v. Gray-Supt. Wagoner Okla. Public Schools, Civ.

No. 5833 (E.D. Okla. 1965) ......................................... 19

Dobbins v. County Board of Education of Decatur Co.,

Civ. No. 1608 (E.D. Tenn. 1965) .................................. 20

Dove v. Parham, 282 F.2d 256 (8th Cir. 1960) ...........16, 26

Dowell v. School Board of City of Oklahoma City

Public Schools, 244 F.Supp. 971 (W.D. Okla. 1965) .. 18

Eubanks v. Louisiana, 356 U.S. 584, 585 (1958) .......16,25

Evers v. Jackson Municipal Separate School District,

328 F.2d 408 (5th Cir., 1964) ............................... .....16, 27

PAGE

Ill

Fayne v. County Board of Education of Tipton Co.,

Civ. No. C-65-274 (W.D. Tenn. 1965) ........................ 20

Franklin v. County School Board of Giles County,

242 F.Supp. 371 (W.D. Va. 1965) ...........15,16,17,19,22,

26,27, 29, 30, 31

Gilliam v. School Board of Hopewell,------U.S. --------,

15 L.ed.2d 187 (1965) .................................................... 18

Green v. School Board of City of Roanoke, Va., 304

F.2d 118 (4th Cir. 1962) ..............................................17, 29

Kemp v. Beasley, 352 F.2d 14 (8th Cir. 1965) ............. 18

Lombard v. Louisiana, 373 U.S. 267 (1963) ...............16,29

Meredith v. Fair, 305 F.2d 343 (5th Cir. 1962) ...........16, 27

N.A.A.C.P. v. Button, 371 U.S. 415, 428 (1963) ........... 2

Norris v. Alabama, 294 U.S. 587 (1935) .....................16,25

North Carolina Teacher Association v. City of Ashe-

boro Board of Education, Civ. No. C-102-G-65 (M.D.

N.C. 1965) ....................................................................... 20

Peterson v. City of Greenville, 373 U.S. 244 (1963) ....16, 28

Price v. Denison Independent School District, 348 F.

2d 1010 (5th Cir., 1965) ................................................ 19

Reece v. Georgia, 350 U.S. 85 (1955) .........................16,25

Robinson v. Florida, 378 U.S. 153 (1964) .................. 16, 29

Rogers v. Paul,------ U .S .------- , 15 L.ed.2d 265 (1965) 18

Ross v. Dyer, 312 F.2d 191, 196 (5th Cir. 1953) .......16,26

Schware v. Board of Bar Examiners, 353 U.S. 232

(1957) ........................................................................17,22,23

PAGE

IV

Shelton v. Tucker, 364 U.S. 479 (1960) .................... 17,22

Singleton v. Jackson Municipal Separate School Dis

trict, 348 F.2d 729 (5th Cir., 1965) .......................... 18

Slochower v. Board of Higher Education, 350 U.S.

551 (1956) ................................................................17,22,23

Steward v. Stanton Independent School District, Civ.

No. 4052, W.D. Tex., Nov. 30, 1965, on appeal to

Fifth Circuit (No. 23291) ............................................ 19

Torcaso v. Watkins, 367 U.S. 488, 495-96 (1961) ....17, 22

Wall v. Stanley County Board of Education, Civ. No.

140-S-65 (M.D. N.C. 1965) ..................... .................. 20

Watson v. City of Memphis, 373 U.S. 526 (1963) ....17,29

Wieman v. Updegraff, 344 U.S. 183 (1952) ................ 17,22

S tatutes

Civil Rights Act of 1964 ............................................... 2

42 U.S.C. Section 2000(d), et seq................................... 18

42 U.S.C. Section 2000h-2 ................................................ 20

PAGE

Other A uthorities

Georgia Teachers and Education Association, Atlanta,

Georgia, Selected Cases Involving Subjective Per

sonnel Practices Utilized in Dismissing Educators 19

H.E.W., General Statement of Policies Under Title VI

of the Civil Rights Act of 1965 Respecting Desegre

gation of Elementary and Secondary Schools, April

1965 19

V

National Education Association, Report of Task Force

Appointed to Study the Problem of Displaced School

Personnel Related to School Desegregation and the

Employment Studies of Recently Prepared Negro

College Graduates Certified to Teach in 17 States,

December 1965 ............................................................. 19, 21

North Carolina Teachers Association, Raleigh, North

Carolina, Teacher Dismissals ...................................... 19

Memorandum of U.S. Commissioner of Education,

June 9, 1965 ................................................................... 19

Ozmon, The Plight of the Negro Teacher, The Ameri

can School Board Journal, pp. 13-14, September

1965 ................................................... 19

President’s Speech, N.E.A. Convention, July 2, 1965,

New Y o rk ......................................................................... 18

Southern Education Reporting Service, Statistical

Summary of School Segregation—Desegregation in

Southern and Border States (1965-66)

PAGE

18

liniteii GLmtrt nf Appeals

F or the E igh th C ircuit

No. 18243

C ivil

C lem ent S. S m ith and T he A rkansas T eachers A ssocia

tion , I n c ., a non-profit association organized under the

laws of the State of Arkansas, and M argaret J . S anders,

plaintiff-intervenor,

—v.-

Appellants,

T he B oard of E ducation of M orrilton S chool D istrict

No. 32; D r . H . B . W h ite , F elver R owell, J ack B land ,

W. O. B yrd, W illiam W offord, W ylie C ox, Directors of

the said District; and T erry H um ble , Superintendent

of Schools,

Appellees.

APPEAL FROM ORDER OF TH E U N ITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR

TH E W ESTERN DISTRICT OF ARKANSAS, FORT SM IT H DIVISION

BRIEF FOR APPELLANTS

Statement of the Case

This is an appeal from a judgment of the United States

District Court for the Eastern District of Arkansas, West

ern Division, denying injunctive relief sought by plaintiffs

and members of their class following their dismissal as

teachers by the Morrilton School District No. 32.

The plaintiffs, two Negro school teachers and the

Arkansas Teacher Association,1 sought injunctive relief

1 The Arkansas Teachers Association is an incorporated association

(R . 133), representing 3400 Negro teachers in the State, including all

2

against the Board’s teacher hiring and assignment policies

under which the principal and all seven Negro teachers

formerly assigned to the Sullivan High School were re

fused contracts and dismissed after Negro students chose

to attend the desegregated Morrilton High School. Alleg

ing that inexperienced white teachers would be hired and

assigned to the Morrilton High School, plaintiffs asserted

their dismissal was motivated by race and sought injunc

tive relief, damages and attorneys fees (R. 1-7).

The Board both moved to dismiss the complaint assert

ing that plaintiffs lacked standing to initiate a class action

(R. 9-10), and filed an answer admitting that plaintiffs had

been employed in the system and had not been reemployed

for the 1965-66 school year, and denying that their refusal

to reemploy plaintiffs and the other dismissed Negro

teachers constituted a violation of constitutional rights.

. * * *

At the trial, the Morrilton Board Superintendent, Terry

Humble, reported that until June 1965 the system oper

ated the Sullivan High School for about 166 Negro pupils

in grades 7-12 (R. 43). A separate junior and senior high

school was operated for white pupils (R. 43).

After receiving requests from Negro parents in January,

1965, to desegregate the system and in an effort to comply

with the Civil Rights Act of 1964 (R. 151), the Board,

which had not previously taken any concrete action on

school integration (R. 194), adopted and placed in effect

a desegregation plan that for the 1965-66 school year

offered pupils entering grades 7-12 a choice of either the

Negro Sullivan or white Morrilton High Schools (R. 152).

those dismissed in the Morrilton system (R . 138). Authority for the

Association’s participation as a party in this litigation is found in

Alston v. School Board, of City of Norfolk, 112 F.2d 992, 997 (4th Cir.

1940), cert, denied, 311 U.S. 693. Cf. N.A.A.C.P. v. Button, 371 U S

415, 428 (1963).

3

When all but four Negro pupils requested a desegregated

education (R. 153, 159), the Board decided to grant their

requests, close the Sullivan High School (R. 154), and

dismiss the Negro teachers (R. 43, 83).

No effort was made to compare the qualifications of the

dismissed Negro teachers with white teachers retained in

the system, although all Negro teachers at Sullivan met

the basic qualifications for a State Teachers License, and

all had been recommended for reemployment and tenta

tively rehired by the Board for the 1965-66 school term

as early as February 1965 (R. 44).

Nevertheless on May 28, 1965, before any of the Negro

teachers had actually received a contract, the Superin

tendent advised them both by letter and personally that

the Sullivan High School would be closed and that they

would be dismissed (R, 45-46). At the time of their dis

missal, the Superintendent indicated that he did not recall

a single vacancy at the white high school (R. 47, 160), but

later conceded under cross examination that vacancies

generally occurred after the end of the school year.

Q. Now, isn’t it true that you knew that some va

cancies would occur in your white teaching staff before

September 1965 on May 28th? A. No, sir, I didn’t

know that.

Q. But had that not happened the previous year?

A. Yes, sir.

Q. And that happened in each other year. A.

That’s right.

Q. And didn’t you reasonably expect that this would

happen? A. Yes, I ’d say I had reason to expect it

would happen.

Q. Did you tell these Negro teachers that there may

be some vacancies and they could apply for them? A.

No, I didn’t (R. 206).

4

Subsequently, 13 white teachers resigned or retired,

which group was replaced by 13 white teachers (R. 47).

None of the dismissed Negro teachers was advised of the

vacancies at the white school or informed that they were

free to make application for those positions (R. 47-48).

The Superintendent defended his failure to advise the

Negro teachers that they could apply by stating that they

knew the “customs and policies” (R. 180), and he assumed

that they had read the Board’s desegregation plan. But

the system had never before dismissed a teacher because

of desegregation (R. 213), and the desegregation plan as

published in a local newspaper merely committed the Board

to desegregate faculty meetings and in-service workshops

during the 1965-66 school year, and to desegregate teachers

and professional staff “as expeditiously as possible” (R.

163).

Moreover, on May 28th, the Superintendent, after in

forming the Negro principal that he would be retired

because he was 65 (R. 158), met with the Negro teachers

and made it clear that they could not expect to be rehired

in the system. Plaintiff Margaret Sanders testified the

Superintendent told them:

“ . . . our services would be discontinued; and so I said

to him, you don’t tell me; I asked him does that mean

that we really didn’t have a job for the coming year;

he says yes, Miss Sanders; and he said he was sorry;

and I asked the question, and then I said you don’t

tell me you have employed your teachers and didn’t

see fit to give us a job; he says yes, Miss Sanders;

and I says I would have felt better if you had just

given one person or somebody, if it wasn’t me, if you

had given some of us a job in the school, in your

5

school. I asked him what did he have to offer; he

said nothing;” (R. 92-93).

Plaintiff Smith offered similar testimony (R. I l l ) which

the Superintendent later confirmed:

Q. Isn’t it true that at this May 28th meeting some

of the Negro teachers there asked you what you had

to offer them? A. I think that’s correct.

Q. And that you told them that you didn’t have

anything to offer them? A. Yes, sir (R. 206).

Plaintiffs Sanders and Smith also testified the Superin

tendent told them that at this particular time, Negro teach

ers could not be utilized because white students would not

adjust to them in the classroom (R. 93, 111, 124). Ques

tioned as to whether the Board’s action didn’t correspond

to a pattern in the Southern states, the Superintendent

reportedly stated that he didn’t know of any Southern

system that had employed Negro teachers (R, 93, 102, 104).

He denied that the fear white students would have adjust

ment difficulties led to the dismissal of Negro teachers (R.

159), and did not recall making such a statement although

conceding that two witnesses had so testified, and that both

local and state newspapers had attributed the statement

to him (R, 159, 217-18).

The Superintendent did state that in his view teachers

completing Negro colleges in the State were less well

trained than teachers who graduated from the State’s

white schools (R. 161, 197-98), and that white teachers

have a superior command of the English language (R. 199)

and thus are better able to communicate (R. 200). He

stated that differences in speech patterns and “environ

ment” would also create difficulties for white students with

6

a Negro teacher (R. 200), and expressed as his “personal

opinion” (R. 202) that even a recently graduated white

teacher with no experience was superior to the dismissed

Negro teachers, because her speech patterns are more like

those of white people (R. 201-02).

Based substantially on such factors, the Superintendent

testified unequivocally that none of the dismissed Negro

teachers was as qualified to fill the vacancies at the Mor-

rilton High School as the white teachers he employed (R.

160), even though he conceded that several of the Negro

teachers had “paper qualifications” as good as or better

than those held by the white teachers.

Superintendent maintained that under Board policies,

the dismissed Negro teachers’ positions were abolished,

and they had to compete with new applicants for the

vacancies that developed (R. 170). Incumbent teachers

at Morrilton High School were not affected, however, and

were viewed as a team the morale of which would be

adversely affected if some were discharged in order to

make room for others (R. 171). It appears that this policy

did not rest on precedent established during several school

closings and consolidations that had occurred in past years,

and while some teachers were dismissed, in most cases,

displaced faculty were reallocated throughout the school

system (R. 166-70). Thus, in the most recent school

closing and consolidation which occurred in 1959, students

and teachers from the closed Central Ward School were

transferred to Northside Elementary School (R. 170). In

1956, six teachers were involved in consolidations, of whom

five were retained and one resigned (R. 169). These

teachers did not have to make new applications for jobs

(R. 212-13). Nor had plaintiffs had to file applications

after their first year in the system (R. 210-11).

7

Although plaintiffs contended the Board had dismissed'

them because of their race and without regard to their

qualifications, an effort was made at the trial to compare

qualifications with those of the white teachers subsequently

hired.

First, dismissed Negro English teacher Geneva Bras

well’s qualifications were compared with those of Gloria

J. King and Katherine Draper, both white. Miss King

was hired to teach English and speech and Miss Draper

to teach English. All three teachers have bachelor’s de

grees, however, Mrs. Braswell is an English major with

fourteen years teaching experience in Morrilton and 22

graduate school credits (R. 49), while neither Miss King

nor Miss Draper has any teaching experience other than

her practice training and neither attended graduate school

(R. 48-49). Moreover, Miss Draper’s college major was

physical education (R. 49), although she has an “honor”

in English (R. 53). Nevertheless, the Superintendent felt

the Negro teacher’s qualifications are inferior to those of

either Katherine Draper or Gloria King (R. 51, 177).

Mr. T. E. Patterson, executive secretary of Plaintiff

Arkansas Teachers Association (R. 132), and a former

school superintendent, disagreed with the Superintendent,

offering his opinion that Mrs. Braswell by reason of her

experience and graduate training was the best qualified

teacher (R. 135).

Significantly, while the Superintendent claimed that sal

ary scales were identical for white and Negro teachers

(R. 185), Mrs. Braswell, in her fourteenth year as a

teacher, received a salary of $3,620 for the 1964-65 school

year, while the two white teachers with no experience

8

and no graduate work were each hired at a salary of

$3,850 for the current school year (R. 49).

Second, Negro plaintiff intervenor and math teacher

Margaret Sanders’ qualifications were compared with those

of Paul Cody and Richard Reed, both white. Cody and

Reed were hired during the summer of 1965, Cody to

teach math and drive a school bus, and Reed to teach

physics and mathematics (R. 53). Miss Sanders holds a

bachelor’s degree with a math major, the equivalent of a

Master’e degree in math from the University of Arkansas

and has attended other predominantly white universities

(R. 88-89). She has thirty-four years teaching experience

(R. 54). Cody, on the other hand, holds only a bachelor’s

degree, has no graduate training and no teaching experi

ence (R. 53). Reed has no graduate training although he

has 2% years teaching experience (R. 53). The Superin

tendent testified that Miss Sanders’ “paper” qualifications

are not inferior to those of Cody or Reed, nor to those

of white teachers then teaching in the high school (R. 55),

and that her qualifications in math were adequate for

either of the white high schools (R. 56). But he did not

advise Miss Sanders that she could apply for a job in

one of the white high schools (R. 55), and explained hir

ing Cody and Reed in preference to Miss Sanders by

saying that they were able to perform additional tasks,

coaching and bus driving, that Miss Sanders was unable

to perform (R. 161). Mr. Reed will be paid $5,095 for the

1965-66 school year, of which $945 is bus driving salary.

Mr. Cody will receive $4,300 (R. 53). Miss Sanders re

ceived $3,620 for the last year she taught (R. 55), and

had she been rehired as a math teacher would have been

paid $4,270 for what would have been her thirty-fifth year

of teaching (R. 101). Teachers Cody and Reed also re

ceived more than plaintiff Smith who was paid $3,820 for

the 1964-65 school year (R. 57).

9

While not considering her as qualified as the white teach

ers hired to fill vacancies in the Morrilton junior and

senior high schools, the Superintendent, following Miss

Sanders intervention in this suit, attempted to place her

in the Negro elementary school by sending her a signed

contract and asking that she report for duty (R. 165).

This action was taken (R. 164-65), although Miss Sanders

had not applied for this job (R. 102) and did not hold a

teaching certificate for elementary schools although quali

fied to secure certification (R. 165). Miss Sanders refused

the job (R. 101, 165-66) because, as a high school math

teacher, she viewed the elementary school offer as a de

motion (R. 102). She felt the Board had not considered

her qualifications, and that when her high school was inte

grated, she should have been integrated too (R, 101).

Third, the qualifications of Negro plaintiff and science

teacher Clement Smith were compared with those of Phillip

Fagan who was hired during the summer of 1965 to teach

science in the white high school. Smith’s qualifications

were also compared with those of Cody and Reed, reviewed

above, for the position of math teacher. Smith holds a

bachelor’s degree with a major in chemistry, twenty-six

graduate school credits and seven years teaching experi

ence (R. 56-57). Fagan holds a bachelor’s degree with a

social science major, six graduate credits and only one

year’s teaching experience (R. 56). The Superintendent

acknowledged Fagan’s paper qualifications as a science

teacher were inferior to Smith’s and admitted that Cody

and Reed’s qualifications to teach math were also inferior

to Smith’s (R. 57). Plaintiffs’ witness, Mr. T. E. Patterson,

agreed that Smith’s qualifications as a science teacher

would be superior to Fagan’s (R. 136).

However, the Superintendent at another point stated

that in his opinion Smith was not superior to or even

10

equal to the white teachers he employed (R. 75). While

Smith had been highly recommended and tenatively re

hired to teach in the Sullivan School (R. 180-81), at the

trial, the Superintendent deemed him not “qualified to

teach in any position in the Morrilton School District” (R.

171). This opinion was based on prior arrests for driving

while under the influence of alcohol (R. 115-16, 187) and

on alleged problems with class decorum which the Super

intendent had observed (R. 118, 175-76.) The Superin

tendent also cited a problem Smith had with his creditors

as a factor in his decision (R. 181, 187). Smith denied

that he could not control his class (R. 118), and, with re

gard to drinking, testified that he was a moderate drinker

but never did so on the job (R. 126). Miss Sanders who

worked with Smith seven years testified that she had never

seen Smith intoxicated at anytime—on or off school prem

ises (R. 108-09). She further testified about Mr. Smith:

“My opinion is that he is wonderful, he is well qualified,

the students love him and he did a wonderful job in

the science department, he excelled all other teachers

that had taught in the science department of the

L. W. Sullivan High School.” (R. 103).

Fourth, the “paper” qualifications of dismissed Negro

social science teacher Phillip O. Jones were compared

with those of Miss Elaine Houston, Mrs. Thetus Stell and

Mrs. Iva Robertson who were hired during the summer of

1965 to teach geography and social studies in the white

junior and senior high schools (R. 58). Jones has a

bachelor’s degree with a social science major, a high school

teaching certificate and one year’s teaching experience

(R. 61).

Miss Houston has a bachelor’s degree with an elemen

tary education major, an elementary school teaching cer

11

tificate, six year’s teaching experience and twelve graduate

credits (E. 58). Mrs. Stell holds a bachelor’s degree with

an elementary education major, a master’s degree in

elementary education, an elementary school teaching cer

tificate, and three year’s teaching experience (R. 59). Mrs.

Robertson has a bachelor’s degree with a major in elemen

tary education, an elementary certificate, teaching expe

rience limited to substitute teaching, and no graduate

training (R. 60-61).

The Superintendent testified that, in his opinion, Mrs.

Stell’s qualifications were superior to Jones because she

has more hours in history than he has reported and so

cial studies, and some gradute hours (R. 62-63). He

also stated that Mr. Jones’ qualifications to teach geog

raphy are inferior to those of Mrs. Robertson “because

she has more teaching experience than Mr. Jones . . .”

(R. 64).

Mr. T. E. Patterson testified that Mrs. Robertson would

be the “ least qualified” of the four persons here being

discussed to teach social science in either a junior or

senior high school because of her elementary education

major, because of her elementary certification and because

her record doesn’t reflect any experience in the major

field (social studies) (R. 137). Mr. Patterson also testified

that in his opinion Miss Houston would be the “next least

qualified person to teach social science.” (R. 137). He

stated: “not having a transcript, I would say she does

not have a secondary certificate and would not qualify;

on this I would say she is not a qualified teacher.” Also,

“ she doesn’t have any graduate work in social studies.”

(R. 137-38).

The Superintendent stated that the District employed

a white teacher named Miss Robertha Jo Lackey to teach

12

history in the white senior high school just two days be

fore trial of this case, indicating that she is a beginning

teacher without any prior teaching experience (R. 48, 195).

He did not know what her grades were, nor whether she

was certified, and was unable to provide other data about

her record (R. 195). However, even without this informa

tion, he acknowledged that Miss Lackey was not superior

“ in qualifications” to Jones (R. 196), but felt that she

was or would be a “ superior teacher” to Jones (R. 196).

The reasons given by the Superintendent for this con

clusion were: (1) “ She can understand some of the prob

lems of the students better” because she graduated from

a predominantly white college (R. 197); (2) her “ com

munication is superior” (R. 197) in that she and other

graduates of her college “handle the English language

superior to most others [Negroes] (R. 199); (3) her “ en

vironment” (R. 200-02), which enables white teachers to

understand the problems of white pupils better than Ne

gro teachers could (R. 182); and (4) her “ speech pattern”

(R. 201) is more like that of white people (R. 202).

Fifth, the qualifications of the dismissed Negro librarian,

Mrs. Hymon King, were discussed although the district

did not later hire a librarian. Mrs. King held a bachelor’s

degree and had training and experience as a librarian.

She also had twenty-seven years’ teaching experience (R.

70-71). The Superintendent stated that she was a qualified

librarian who was better qualified than the white junior

high librarian who “was employed prior to the time that

these teachers were dismissed” (R. 71). It appears how

ever that the white librarian was employed in February,

1965 for the junior high school job at the same time, and

on the same “tentative” basis, as Mrs. King was employed

to the position at Sullivan (R. 71-72).

13

The Superintendent stated that during the summer of

1965, Mrs. King was employed to teach at the Negro

elementary school but later declined the assignment (R.

164).

After both Mrs. King and Miss Sanders declined em

ployment at the Negro elementary school, the Superin

tendent filled the position by employing the Negro high

school principal, Hymon King, who was “ retired” at the

close of the 1965 school term (R. 158). He stated that he

“ suspected” Mr. King was qualified to be a high school

teacher (R. 214), but admitted that he was subjecting

the Negro elementary pupils “ to an inferior teacher.”

(R. 213).

Sixth, the three other dismissed Negro teachers were

Mr. King, discussed above, Mr. John M. Sutton, an agri

culture teacher, and Miss Helen Oliver, a home economics

teacher. Their paper qualifications were not compared

with those of any particular white teacher. Sutton, how

ever, holds both a bachelor’s and a master’s degree in

Agriculture, has twenty-two years teaching experience (R.

72), and was recommended and rehired by the Super

intendent for reemployment during the 1965-66 school

term (R. 73). The Superintendent testified, however, that

Mr. Sutton was “not qualified to teach in any school”

because of his “personal appearance” (R. 72-73), while

the agriculture teacher in the white school had thirty

years experience, a bachelor’s and master’s degree, and

was deemed by the Superintendent one of the most out

standing agriculture teachers in the state (R. 74). Al

though Mr. Sutton was “academically prepared” to teach

science, the Superintendent did not compare his qualifica

tions with those of any white science teachers . . . “be

cause of his personal appearance.” (R. 74).

14

While reporting that if Negro elementary children choose

to enroll in desegregated schools for the 1966-67 school

year, he would advise Negro teachers that they must

apply for vacancies in such schools (R. 82), there was

no indication that the procedures leading to the dismissal

of Negro high school teachers would be altered. The jobs

of Negro elementary school teachers will be abolished, and

no voluntary assignments of Negro teachers to the deseg

regated elementary schools will be made (R. 83). More

over, the unavailability of white teachers to teach in Ne

gro schools would be a factor in selecting teachers (R.

181-82), as will be the Superintendent’s belief that Negro

teachers are less capable of teaching white children than

white teachers (R. 182-83).

^ *- *

On October 8, 1965, the district court entered an opinion

acknowledging that school boards are bound by the Four

teenth Amendment’s equal protection clause (R. 31), but

suggesting that school integration poses an economic threat

to Negro school teachers as a cl^ss which does not concern

the courts (R. 32). He ruled that:

“ If a Negro school is closed at a time when there are

no vacancies in the remaining schools, the Constitu

tion does not require the school board to reevaluate

the entire faculty, or to replace white teachers with

Negroes affected by the closing, or to solicit affirma

tively Negro applicants for jobs which subsequently

become open.” (R. 36).

Assuming without deciding that the Fourteenth Amend

ment affords some protection to Negro teachers where

faculties are affected by school desegregation (R. 32-33),

the court found no constitutional violation resulted from

the Board’s application of its school consolidation policy

(defined as absorbing teachers from closed schools where

15

such could be done without displacing other teachers)

to the situation where a school is closed as a result of

desegregation (R. 33); and while conceding that prior to

desegregation, Negro teachers were eligible for employ

ment only in Negro schools (R. 33), further found that

Negro teachers lost their jobs not because of their race,

but because they constituted the faculty of a formerly all-

Negro school.

Rejecting plaintiffs’ contention that the Fourteenth

Amendment required evaluation of their qualifications with

those of teachers retained in the system, the court refused

to follow cases where such evaluation had been required2

or approved,3 suggesting such a policy would give Negro

teachers tenure rights not possessed by white teachers

(R. 34). Under this view of the case, the court found

it unnecessary to review the testimony comparing qualifi

cations of Negro teachers with the newly hired white teach

ers (R. 35).

Finally, the couit noted that only two Negro teachers

displayed any interest in the proceedings, and that neither

of these suffered any financial loss as a result of the

Board’s action (R. 35).

From the October 8, 1965 order dismissing the complaint

(R. 37) plaintiffs noticed an appeal on the same date

(R. 38).

2 Franklin v. County School Board of Giles Co., 242 F Su d d 371

(W .D . Va. 1965).

3 Brooks v. School District of Moberly, Mo., 267 F 2d 733

1959).

(8th Cir.

16

Statement of Points to Be Argued

1

The court below erred in failing to find on the record

in this case that plaintiffs’ dismissal was racially motivated

and violated constitutional rights protected by the Four

teenth Amendment.

Brooks v. School District of Moberly, Mo., 267

F.2d 733 (8th Cir. 1959);

Christmas v. Board of Education of Harford

County, Md., 231 F.Supp. 331 (D.C. Md. 1964);

Dove v. Parham, 282 F.2d 256 (8th Cir. 1960);

Franklin v. County School Board of Giles County,

242 F.Supp. 371 (W.D. Va. 1965);

Adler v. Board of Education, 342 U.S. 485, 493

(1952);

Alston v. School Board of City of Norfolk, 112

F.2d 992, 997 (4th Cir. 1940);

Avery v. Georgia, 345 U.S. 559 (1953);

Bailey v. Patterson, 323 F.2d 201 (5th Cir. 1963);

Bryan v. Alston, 148 F.Supp. 563, 567 (E.D.S.C.

1957) (dissent);

Cramp v. Board of Public Instruction, 368 U.S.

278 (1961);

Evers v. Jackson Municipal Separate School

District, 328 F.2d 408 (5th Cir. 1964);

Eubanks v. Louisiana, 356 U.S. 584, 585 (1958);

Lombard v. Louisiana, 373 U.S. 267 (1963);

Meredith v. Fair, 305 F.2d 343 (5th Cir. 1962);

Norris v. Alabama, 294 U.S. 587 (1935);

Peterson v. City of Greenville, 373 U.S. 244

(1963);

Reece v. Georgia, 350 U.S. 85 (1955);

Robinson v. Florida, 378 U.S. 153 (1964);

Ross v. Dyer, 312 F.2d 191, 196 (5th Cir. 1963);

17

Scliware v. Board of Bar Examiners, 353 U.S.

232 (1957);

Shelton v. Tucker, 364 U.S. 479 (1960);

Slochower v. Board of Higher Education, 350

U.S. 551 (1956);

Torcaso v. Watkins, 367 U.S. 488, 495-96 (1961);

Watson v. City of Memphis, 373 U.S. 526, (1963);

Wieman v. Updegraff, 344 U.S. 183 (1952).

2

The court below erred in failing to find that the Four

teenth Amendment forbids arbitrary dismissal of all Ne

gro teachers assigned to a segregated school closed as

part of the desegregation process where,

(a) the qualifications of such teachers were not evaluated

by valid and ascertainable standards with those of teachers

retained in the system, and

(b) only the dismissed Negro and not incumbent white

teachers were required to apply and compete with new

white applicants seeking vacant teaching positions.

Brooks v. School District of Moberly, Mo., 267

F.2d 733 (8th Cir. 1959);

Cooper v. Aaron, 358 U.S. 1, 16 (1958);

Franklin v. County School Board of Giles County,

242 F.Supp. 371 (W.D. Va. 1965);

Bradley v. School Board of Richmond, 317 F.2d

429 (4th Cir. 1963);

Calhoun v. Latimer, 321 F.2d 302 (5th Cir. 1963),

vacated 377 U.S. 263 (1964);

Green v. School Board of City of Roanoke, Va.,

304 F.2d 118 (4th Cir. 1962).

18

ARGUMENT

Preliminary Statement

The ever increasing reluctance of the federal judiciary

to condone further delay in the complete desegregation of

public school systems as mandated more than a decade ago

in Brown v. Board of Education, 347 TJ.S. 483; 349 U.S.

294 ;4 5 together with increasing implementation of the 1964

Civil Rights Act,6 have resulted in a small, but noticeable

increase in pupil desegregation6 and, as a result, increasing

attention on faculty desegregation. As Negro students ob

tain transfers from all-Negro to formerly all-white schools,

and the formerly all-Negro schools are closed or integrated,

Negro teachers in Arkansas as elsewhere in the South

(R. 146) have been summarily dismissed rather than trans

ferred along with Negro students or employed and as

signed without regard to race. This policy has alarmed the

President of the United States,7 concerned the United

4 Rogers v. Paul, -------- U.S. --------, 15 L.ed.2d 265 (1 9 6 5 ); Bradley

v. School Board of Richmond, -------- U .S. -------- , 15 L.ed.2d 187 (1 9 6 5 );

Gilliam v. School Board of Hopewell, -------- U .S. --------, 15 L.ed.2d 187

(1 9 6 5 ); Kemp v. Beasley, 352 F.2d 14 (8th Cir., 1 9 6 5 ); Singleton v.

Jackson Municipal Separate School District, 348 F.2d 729 (5th Cir.,

1 9 6 5 ); Dowell v. School Board of Oklahoma City, 244 F . Supp 971

(W .D .O kla. 1965).

5 42 U .S.C. Section 2 0 00 (d ), et seq.

6 See Southern Education Reporting Service, Statistical Summary of

School Segregation— Desegregation in Southern and Border States (1965-

66).

7 Speech, N .E .A . Convention, July 2, 1965, New York. The President

said:

“ For you and I are both concerned about the problem of the dis

missal of Negro teachers as we move forward— as we move forward

with the desegregation o f the schools of America. I applaud the

action that you have already taken.

“ For my part, I have directed the Commissioner of Education to

pay very special attention in reviewing the desegregation plans, to

guard against any pattern of teacher dismissal based on race or

national origin.”

19

States Department of Health, Education and Welfare,8

been the subject of intensive studies by national teacher

groups,9 and generated a growing number of lawsuits.10

8 In addition to the Department’s General Statement of Policies Under

Title VI of the Civil Rights Act of 1965 Respecting Desegregation of

Elementary and Secondary Schools, published in April 1965, the State

ment, inter alia, requires the desegregation of school faculties (the H .E .W .

Policies were adopted by the Fifth Circuit as minimum school desegrega

tion standards and published as an appendix to Price v. Denison In

dependent School District, 348 F.2d 1010 (5th Cir. 1 9 6 5 )) . The United

States Commissioner of Education in response to numerous complaints

that Negro teachers were being dismissed or released by school boards

seeking to avoid faculty desegregation, published a memorandum on

June 9, 1965, and distributed same to his staff and to the chief school

officers in every State. H e reported that the complaints were being in

vestigated, that the policies or practices complained o f were in direct vio

lation of Title V I o f the 1964 Civil Rights Act, and the Generel State

ment and Policies published in April 1965. The memorandum concluded:

“ The statement of policies, as you know, requires desegregation

plans to contain provisions concerning desegregation of school facul

ties. A school district cannot avoid the requirement that it desegregate

its faculties by discriminatorily dismissing or releasing its Negro

teachers. Nor can a freedom o f choice plan be deemed ‘free’ i f in

direct pressure is placed on Negro students to forego rights under

such a plan by threatening Negro teachers with loss o f their jobs,

should Negro students leave Negro schools to attend desegregated

schools?”

9 National Education Association, Washington, D. C., “Report of Task

Force Appointed to Study the Problem of Displaced School Personnel

Related to School Desegregation and the Employment Studies of Recently

Prepared Negro College Graduates Certified to Teach in 17 States” De

cember 1965; North Carolina Teachers Association, Raleigh, North Caro

lina “ Teacher Dismissals” ; Georgia Teachers and Education Association,

Atlanta, Georgia, “ Selected Cases Involving Subjective Personnel Prac

tices Utilized in Dismissing Educators.” See also, Ozmon, “ The Plight

of the Negro Teacher” , The American School Board Journal, pp. 13-14,

September, 1965.

10 Franklin v. County School Board of Giles County, 242 F . Supp. 371

(W .D . V a. 1 9 6 5 ); Christmas v. Board of Education of Harford County,

Md., 231 F . Supp. 331 (D .C . Md. 1 9 6 4 ); Buford v. Morganton City

Board of Education, 244 F . Supp. 437 (W .D .N .C . 1 9 6 5 ); Chambers v.

Hendersonville City Board of Education, 245 F. Supp. 759 (W .D .N .C .

1965), on appeal to Fourth Circuit (No. 10 ,3 7 9 ); Steward v. Stan

ton Independent School District, Civ. No. 4052, W .D . Tex., Nov. 30,

1965, on appeal to Fifth Circuit (No. 2 3 2 9 1 ); Dean v. Gray— Supt.

20

The concern of the United States Department of Justice

is reflected by its motion filed with this Court on January

24, 1966, seeking leave to intervene as an appellant in

this case. Exercising authority granted by Section 902 of

the Civil Rights Act of 1964, 42 U.S.C. 2000h-2, the At

torney General has certified this case as one of general

public importance. The appropriateness of the Attorney

General’s petition is evidenced by the similarity of the

procedures followed by the Morrilton Board to those being

utilized by a steadily increasing number of school systems

all over the South. This process of pupil desegregation

and teacher dismissal has recently been reported on in

great detail by the National Education Association, which

reviewed the problem in the following terms:

“Concern with faculty integration is becoming acute

because of current practices. Typically, whenever

twenty or twenty-five Negro pupils are transferred

from a segregated school, the Negro teacher left

without a class is in many cases dismissed rather

than being transferred to another school with a

vacancy. When all the pupils attending small Negro

schools are reassigned to previously white schools,

principals as well as an increased number of teachers

are often faced with the problem of relocation. The

1964 summer crisis caused by the growing threat and

the actual loss of positions brought a stream of pro-

Wagoner Oklah. Public Sells., Civ. No. 5833 (E .D . Okla. 1 9 6 5 ); Brooks

v. School District of City of Moberly, Mo., 267 F.2d 733 (8th Cir. 1959).

The following cases have been filed, North Carolina Teacher Associa

tion v. City of Asheboro Board of Education, Civ. No. C-102-G -65 (M .D .

N.C. 1 9 6 5 ); Wall v. Stanley County Board of Education, Civ. No. 140-

S-65 (M .D .N .C . 1 9 6 5 ); Dobbins v. County Board of Education of

Decatur Co., Civ. No. 1608 (E .D . Tenn. 1 9 6 5 ); Fayne v. County Board

of Education of Tipton Co., Civ. No. C-65-274 (W .D . Tenn. 1 9 6 5 );

Bonner v. Texas City Independent School District, Civ. No. 65-G-56

(S .D . Tex. 1965).

21

tests and calls for assistance to the NEA’s Commis

sion on Professional Rights and Responsibilities”

(p. 7).

“As has been demonstrated, ‘white schools’ are

viewed as having no place for Negro teachers. As

a result, when Negro pupils in any number transfer

out of Negro schools, Negro teachers become surplus

and lose their jobs. It matters not whether they

are as well qualified as, or even better qualified than,

other teachers in the school system who are retained.

Nor does it matter whether they have more seniority.

They were never employed as teachers for the school

system—as the law would maintain—but rather as

teachers for Negro schools” (p. 13).11

The deprivation of constitutional rights threatened by

these dismissals warrants careful scrutiny by this Court

for only by such inquiry can the constitutional rights of

Negro teachers be assured. It is from this perspective

that the issues raised by this case must be viewed. It

is with this background that the contested dismissals

characterized by the lower court as an economic but not

a constitutional threat to Negro teachers (R. 32) must be

examined.

11 “Report of Task Force Appointed to Study the Problems of Dis

placed School Personnel Related to School Desegregation,” see note

9, supra. The study was conducted under the auspices o f the National

Education Association and financed jointly by the Association and a grant

from the United States Office of Education, Department of Health, Edu

cation and Welfare.

22

I.

Plaintiffs, Under Generally-Applied Rules of Proof

in Racial Discrimination Cases, Sufficiently Proved

Their Dismissal by the Board Was Racially Motivated

and Violated Constitutionally-Protected Rights.

The law is clearly established that public servants or

employees may not, consistent with the Constitution, be

deprived of the right to pursue their profession on the

basis of some frivolous, arbitrary or racially discriminatory

ground. Cramp v. Board of Public Instruction, 368 U.S. 278

(1961); Torcaso v. Watkins, 367 U.S. 488, 495-96 (1961);

Schware v. Board of Bar Examiners, 353 U.S. 232 (1957);

Slochower v. Board of Education, 350 U.S. 551 (1956) j

Wieman v. Updegraff, 344 U.S. 183 (1952). Negro teachers

seeking relief against interference with their professional

careers based on race frequently have been included within

the protection of these rights. Shelton v. Tucker, 364 U.S.

479 (1960); Alston v. School Board of the City of Norfolk,

112 F.2d 992 (4th Cir. 1940); Bryan v. Alston, 148 F. Supp.

563, 567 (E.D.S.C. 1957) (dissent).

This Court has clearly indicated that the scope of con

stitutional protection encompasses Negro teachers, pro

tecting them from arbitrary, unreasonable, or racially moti

vated dismissal during the transition to desegregated

schools. Brooks v. School District of City of Moberly, Mo.,

267 F.2d 733, 740 (8th Cir. 1959). See also, Franklin v.

County School Board of Giles County, 242 F. Supp. 371

(W.D.Va. 1965); Christmas v. Board of Education of Har

ford County, 231 F. Supp. 331 (D.Md. 1964).

Conceding that certain definite standards or criteria

are permissible, Adler v. Board of Education, 342 U.S. 485,

493 (1952), officers of a state, in applying such standards,

23

“ cannot exclude an applicant when there is no basis for

their finding that he fails to meet these standards or when

their action is invidiously discriminatory.” Schware v.

Board of Bar Examiners, supra, at 239.

Thus, having the affirmative burden to accord equal

protection and due process to Negro teachers, a school

board which, in the process of desegregating its system,

closes a Negro school and dismisses the whole faculty

should carry the affirmative burden of showing this result

was not racially motivated and that the Negro teachers

dismissed were replaced by teachers judged superior by

objective and readily measurable standards. Cf. Schware

v. Board of Bar Examiners, supra; Slochower v. Board

of Education, supra; Brooks v. School District of City of

Moherly, Mo., supra at 740.

On this record, however, it is perfectly clear that the

plaintiffs and the other faculty members of the abandoned

Negro high school were dismissed without any thought of

offering them teaching positions in the desegregated high

schools. Having determined to close the Negro School, the

Superintendent “ retired” the principal (R. 158) and an-,

nounced to the Negro faculty that their services were

discontinued (R. 92). He told those who asked that he

had no positions to offer them (R. 93, 206) even though,

based on past experience, he expected vacancies to occur

in the desegregated high schools (R. 206). When 13 white

teachers later resigned, they were replaced by 13 white

teachers, all of whom were new to the system, and many

of whom had qualifications clearly inferior to the dismissed

Negro teachers. 'While maintaining on one hand that

Board policies precluded consideration of the dismissed

Negro teachers (R. 170), the Superintendent contends that

he did weigh their qualifications against those of the new

applicants (R. 163). Placed under the Superintendent’s

24

ever-changing measure of values, the Negro teachers, each

of whom he had tentatively rehired for the Negro school

only a few months before (R. 44), were found to be in

ferior to white applicants (R. 160).

The Board, of course, denies that race played a part in

the dismissals, but both plaintiffs testified (R. 93, 111, 124),

and state and local newspapers quoted the Superintendent

as stating that Negro teachers could not at this time be

successfully placed in classrooms with white students (R.

159, 217-18). The Superintendent was unable to recall

making such statements, but provided a wealth of testi

mony that reflects this point of view. He believes that

even when they possess more training, experience and

specific teaching skills, Negro teachers are inferior to white

teachers in general education (R. 161, 197-98), command

of the English language (R. 199), and ability to com

municate (R. 200). Questioned by the Board attorney as

to factors he deems significant with regard to the general

ability of a Negro teacher to teach white students or a

white teacher to teach Negro students:

A. One of the major things that always comes into

consideration is environment. White teachers do not

understand the problems of Negro students, and it’s

true the other way, the Negro teachers do not under

stand many of the problems of the white students

as do teachers of that particular race.

Q. In your judgment do you have Negro teachers

teaching in the elementary schools at Morril who do

a superior job of instruction to the Negro students

in their classes over what a typical white teacher

could do? A. Yes, sir.

Q. Does that relate in any way to the communica

tion, to the ability of the teacher to communicate with

the child? A. Yes, sir, it does.

25

Q. And tlie ability of the teacher to establish rapport

of the child! A. Yes, sir.

Q. Within the framework of these practical situa

tions that you have outlined do you plan to employ

teachers from now on in the Morrilton School District

on the basis of selecting the most qualified available

applicant for every job without regard to race! A.

Yes, sir, that is correct. (E. 182-83). (emphasis

added).

Based on the Superintendent’s “ practical situations” cri

teria, appellants submit that it is impossible to select

teachers without regard to race and without violating fun

damental equal protection standards. Clearly, the use of

such criteria in the context of this case, required closer

judicial scrutiny than the lower court’s opinion indicates

it received.

Traditionally, where racial discrimination is charged,

courts have required more than mere pious denials of racial

bias to absolve state officials alleged to have violated Four

teenth Amendment rights. In criminal cases where racial

discrimination in jury selection is alleged, federal and state

courts, upon a showing that Negroes are eligible but have

not been chosen, lay on the State the burden of proving

jury discrimination does not exist. See Eubanks v. Louisi

ana, 366 U.S. 584 (1958); Reece v. Georgia, 350 U.S. 85

(1955); Avery v. Georgia, 345 U.S. 559 (1953); Norris v.

Alabama, 294 U.S. 587 (1935). Without such a rule, even

the most flagrant instances of racial discrimination in jury

exclusion would remain beyond the remedy of the courts

and the Constitution. Norris v. Alabama, supra, at 598.

The court below found that “a preponderance of the

evidence” (R. 33) indicated that the application of long

standing personnel practices rather than invalid racial con

26

siderations were involved in the Board’s dismissal of Negro

teachers and hiring of white teachers for all vacancies in

the desegregated high schools. Such a finding ignores the

lesson contained in several racial discrimination cases, the

effect of which is that even clearly valid administrative

rules and procedures must not be followed if they effect a

discriminatory result. Dove v. Parham, 282 F.2d 256 (8th

Cir. 1960); Ross v. Dyer, 312 F.2d 191, 196 (5th Cir. 1963).

More important, the finding reflects acceptance of the

Board’s denial that the dismissals were based on race,

which denial flies in the face of the Superintendent’s fre

quently evidenced concern that Negro teachers, by reason

of education, environment, and speech patterns, are in

capable of adequately serving in white classrooms.

To the extent that the Board denials of discrimination

and the manifestations of bias reflected by the record are

in conflict, the cases indicate that the issue must be resolved

in plaintiffs’ favor.

Without express mention of the burden of proof prob

lem, the district court in Franklin v. County School Board

of Giles County, 242 F. Supp. 371, 374 (W.D.Va. 1965),

carefully scrutinized and rejected the Superintendent’s

basis for selecting teachers, where the teacher force was

reduced from 186 to 179 teachers as a result of the closing

of Negro schools, and the 7 teachers released were all

Negroes. Similarly, in Christmas v. Board of Education

of Harford County, 231 F. Supp. 331, 337 (D.Md. 1964) the

court ruled: “ . . . the failure to hire a single Negro appli

cant for the desegregated schools, although the qualifica

tions of some of these applicants are obvious and admitted,

justified plaintiffs’ skepticism, and requires that an injunc

tion be issued prohibiting discrimination on the basis of

race in hiring new teachers.”

27

Significantly, in both the Harford, and Giles County de

cisions, supra, the district courts carefully noted that the

abrupt reductions in the ranks of Negro teachers corre

sponded with school desegregation efforts. Judicial con

sideration of such past racially discriminatory practices

and laws is crucial as evidenced in Meredith v. Fair, 305

F.2d 343 (5th Cir. 1962); Bailey v. Patterson, 323 F.2d 201

(5th Cir. 1963); Evers v. Jackson Municipal Separate

School District, 328 F.2d 408 (5th Cir. 1964); and was par

ticularly appropriate in the Harford and Giles County cases

where the school board, did not immediately desegregate

the schools, but delayed taking affirmative action until re

quired by court order. Similar attention is appropriate

here where the Board delayed initiation of school desegre

gation for more than a decade until threatened with litiga

tion or the loss of federal funds.

Immediate and good faith compliance with the Supreme

Court’s desegregation order was an important factor in

this Court’s decision in Brooks v. School District of City of

Moberly, Mo., 267 F.2d 733 (8th Cir. 1959). There, all 11

Negro teachers in the system were dismissed and the dis

trict court found no racial discrimination. In addition to

the Moberly Board’s prompt compliance, this Court sup

ported its conclusion that the Board was not influenced by

racial considerations in employing its teachers by noting

that some white teachers had been included in the reduction

in faculty resulting from the integration process. It was

also noted that prior to integration, Negroes were paid

salaries equal to those of white teachers and the Negro

school was not inferior to white schools. The record in

this case is filled with contrary evidence which, appellants

submit, supports a contrary conclusion. Negro teachers with

years of experience are paid less than newly hired white

teachers with no experience (R. 49, 53, 55, 57, 101). The

28

Negro Sullivan High School was inferior to the white

Morrilton High School (R. 194-95), and no white teachers

lost their jobs as a result of the integration process which,

in effect, reduced the total faculty by 7 teachers and one

principal, all of whom are Negroes.

The district court’s suggestion that Negro teachers were

dismissed not because they are Negroes, but because they

are assigned to a Negro school which was closed when the

Board finally decided to desegregate its schools, hardly

serves to validate the Board’s racially motivated action

when it is considered that the Negro teachers were origi

nally assigned to the Sullivan School on a racial basis.

Thus the clearly invalid racial assignments bar the court

below from successfully equating the Board’s personnel

actions in earlier school consolidations with the dismissals

contested here.

In summary, the Board’s contention that the dismissal

of its Negro teachers was not based on race, is irreparably

compromised by both the record which clearly evidences

the presence of invalid racial considerations in the deci

sions, and its maintenance of segregated schools long after

it was apparent to all that the policy irreparably denied

Negro pupils their constitutional right to a desegregated

education. Indeed, the Board is in no better position than

the State officials who contended that the Negroes arrested

and convicted while seeking desegregated service in pri

vately owned eating places were not prosecuted because of

race. Reversing such convictions, the Supreme Court noted

the presence of segregation statutes, regulations and poli

cies, and held that because of the continued presence of

State-sponsored segregation requirements, the officials’ de

nials that their actions were racially motivated would not be

heard. Peterson v. City of Greenville, 373 U.S. 244 (1963).

29

Lombard v. Louisiana, 373 U.S. 267 (1963); Robinson v.

Florida, 378 U.S. 153 (1964).

The applicability of the rationale of these cases to the

instant case is inescapable. The history of discrimination

by the School Board, particularly in employment and as

signment of teachers and school personnel, warrants here

an affirmative showing that neither plaintiffs nor the mem

bers of their class were denied employment because of race.

Failure of the court below to require such showing reduced

the rights of the Negro teachers involved to sterile pro

nouncements without meaning or force. Watson v. City of

Memphis, 373 U.S. 526 (1963).

II.

School Boards Effecting Faculty Reductions Required

by Desegregation Must Evaluate All Teachers, Both In

cumbent and Applicants, by Valid, Objective and Ascer

tainable Standards.

A. To subject plaintiffs and their class to different

standards or criteria than that required of white teachers

in the system unquestionably denies them equal protection

of the laws. Franklin v. County School Board of Giles

County, supra, at 374. See also Bradley v. School Board

of the City of Richmond, 317 F.2d 429 (4th Cir. 1963);

Green v. School Board of the City of Roanoke, 304 F.2d

118 (4th Cir. 1962); Calhoun v. Latimer, 321 F.2d 302, 304-

305 (5th Cir. 1963), vacated 377 U.S. 263. Here, plaintiffs,

unlike their white counterparts who had taught in the

school system during prior years, were considered as being

out of a job and, assuming they were considered at all,

were compared for vacancies in the Morrilton High Schools

along with new white applicants (R. 170). White teachers

already assigned to the Morrilton High School were not

similarly compared, but were deemed part of the team

30

who for morale reasons could not be replaced even by a

better qualified teacher. The issue was expressly posed

to the Superintendent by the Board attorney:

Q. There has been some suggestion, I take it, that

you should have considered the displaced teachers on

the basis of whether one of them might be better

qualified than an encumbent teacher you had in some

other school and thereby discharge the encumbent

teacher and replace them with the teacher that had

been displaced? A. No, sir, that’s not my policy, and

I don’t think it is the policy of any school admin

istrator. A school staff becomes a team and if you

disrupt that team by discharging the people on it in

order to make room for another person you upset the

morale of the teachers and upset the morale of the

students in that particular school and even to some

extent the parents (R. 171).

The court below approved this policy and suggested that

it was required to prevent granting to Negro teachers “a

stability of tenure not possessed by white teachers” (R. 34).

But as this case illustrates, the application of the policy

protects the positions of white teachers and results in the

jobs of Negro teachers being abolished without regard to

their training and experience. It follows that where the

desegregation process enables a reduction in faculty size,

fundamental concepts of fairness require selection of all

teachers based on an objective evaluation of their qualifi

cations. Moreover, as the district court noted in Franklin

v. County School Board of Giles County, supra, at 374,

“ the making of such an evaluation is strong evidence of

good faith, see Brooks, et al., supra, 267 F.2d at 736, . . . ”

Teacher morale, no less than law and order, while desir

able, may not be maintained at the sacrifice of constitu

tional rights. Cooper v. Aaron, 358 U.S. 1, 16 (1958).

31

B. Plaintiffs and members of their class were denied

due process and equal protection of the laws when re

quired to compete with new white teachers although other

white teachers similarly situated as plaintiffs were not

similarly appraised. Franklin v. County School Board of

Giles County, supra; Calhoun v. Latimer, supra.

This arbitrary categorization of the Negro faculty as

“displaced teachers” further evidenced the philosophy con

tained in the lower court’s opinion that Negro teachers

may be sacrificed as the price of school integration. The

constitutional invalidity of this procedure was not cured

even if the Board actually considered the dismissed Negro

teachers for vacancies in the desegregated high schools

since standards used by the Superintendent were, as the

situation demanded, vague, unreasonable, arbitrary, and,

in some instances, expressly based on race.

As indicated above, it was the School Board’s failure to

compare the qualifications of all teachers for vacancies

in the school system which was held repugnant to the

constitutional rights of Negro teachers in Franklin v.

County School Board of Giles County, supra, at 374. It

should also be condemned here. Applying such standards

to the school system required that Negro teachers who

formerly taught in the Sullivan High School be fairly

weighed and considered with all teachers teaching grades

for which the Negro teachers were qualified rather than

being considered as mere displaced persons without jobs

and competing only for vacancies in the school system.

Failure of the court below to require this comparison

and the same objective appraisal of white teachers simi

larly situated as plaintiffs and members of their class

constituted an abuse of discretion requiring reversal of

the lower court’s decision.

32

CONCLUSION

Plaintiffs respectfully pray that this Court reverse the

holding of the lower court and remand the case with in

structions requiring both the reinstatement of all Negro

teachers available and willing to accept positions, and the

preparation by the Board of definite, objective and clearly

ascertainable teacher qualification standards, which stand

ards are to be approved by the district court and ordered

into effect until the transition to a desegregated faculty

is completed. If a reduction in teacher force is required,

the same standards or criteria are to be applied to all

teachers and applicants, and after such appraisal, should

plaintiffs or any member of their class be refused employ

ment, the Board must come forth with clear and convinc

ing evidence to show that those denied employment were

accorded due process and equal protection of the laws.

Plaintiffs are entitled both to damages for the economic

losses resulting from the Board’s action and to their costs

and attorney fees as prayed for in the complaint.

Respectfully submitted,

J ohn W . W alker

1304-B Wright Avenue

Little Rock, Arkansas

H arold A nderson

610 West Ninth Street

Little Rock, Arkansas

George H oward, J r .

329% Main Street

Pine Bluff, Arkansas

J ack G reenberg

D errick A. B ell, J r .

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

Attorneys for Appellants

MEILEN PRESS INC. — N. Y. C. 219