General Telephone Company of the Southwest v. Falcon Brief Amicus Curiae

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1981

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. General Telephone Company of the Southwest v. Falcon Brief Amicus Curiae, 1981. 3eb61010-b39a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/39c1a1bc-cddf-450d-8348-30c3aa881474/general-telephone-company-of-the-southwest-v-falcon-brief-amicus-curiae. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

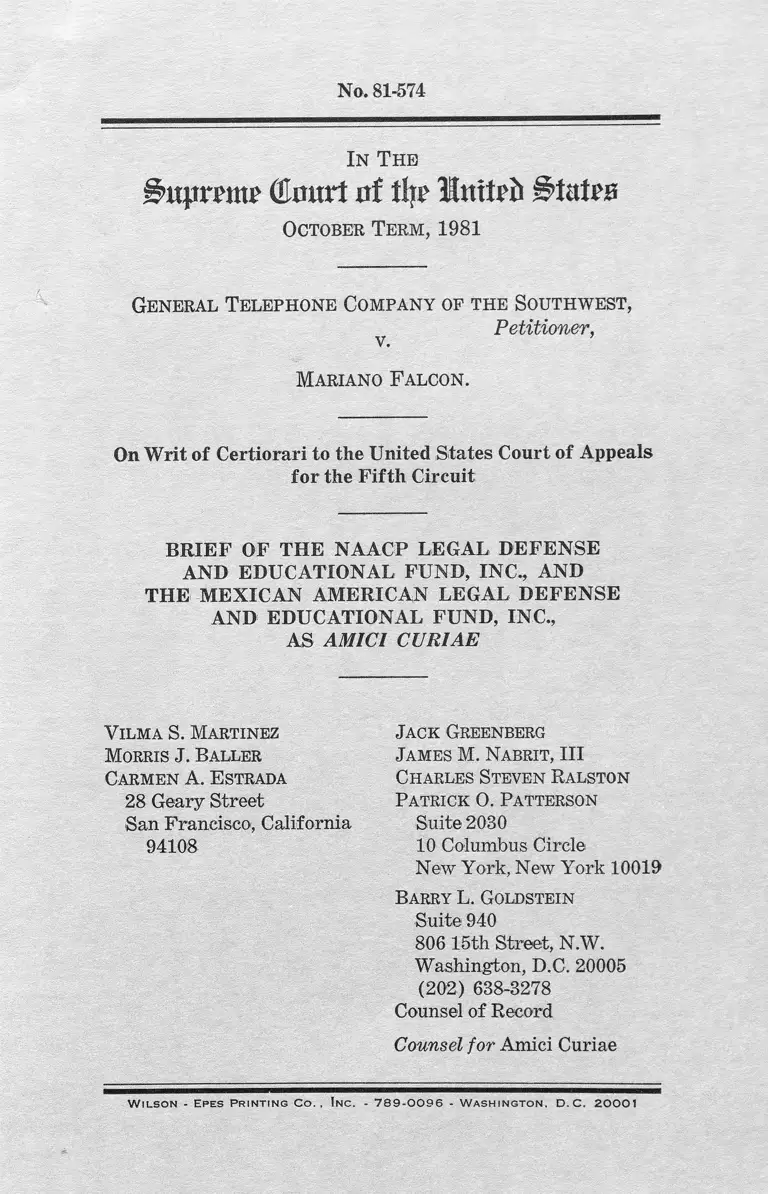

No. 81-574

In T he

jtrme (Emtrt of % Inttrxi States

October Term, 1981

Gen er a l T e l e p h o n e Co m pan y of t h e So u th w est ,

Petitioner, v. ’

Mariano F a lcon .

On Writ of Certiorari to the United States Court of Appeals

for the Fifth Circuit

BRIEF OF THE NAACP LEGAL DEFENSE

AND EDUCATIONAL FUND, INC., AND

THE MEXICAN AMERICAN LEGAL DEFENSE

AND EDUCATIONAL FUND, INC.,

AS AMICI CURIAE

Vilma S. Martinez

Morris J . Baller

Carmen A. E strada

28 Geary Street

San Francisco, California

94108

J ack Greenberg

J ames M. Nabrit, III

Charles Steven Ralston

P atrick 0 . P atterson

Suite 2030

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

Barry L. Goldstein

Suite 940

806 15th Street, N.W.

Washington, D.C. 20005

(202) 638-8278

Counsel of Record

Counsel for Amici Curiae

W i l s o n - Epes P r i n t i n g Co.. In c . - 789-0096 - W a s h i n g t o n . D.C. 20001

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Page

Table of Authorities...................................................... —- 11

INTEREST OF AM ICI........................... ....... ............... 1

SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT ....................... ... ........... 2

ARGUMENT ............ ........ ....... ....... ........... ...............- 4

I. The Writ Should Be Dismissed as Improvidently

G ranted............... ....... ........ ............... ............ ....... 4

II. A Title VII Class Action May Properly Be Main

tained on Behalf of a Broad Class When the Re

quirements of Rule 23 Are Satisfied ............- ..... 8

A. The Fifth Circuit’s Standard Permitting Cer

tification of Broad Classes in Employment

Discrimination Actions Is Consistent with

the Class-Based Nature of Discrimination,

and it Effectuates the Purposes of both Title

VII and Rule 23 ........... ............ ....... -...... . 8

1. Unlawful Discrimination Is Class-Based.. 8

2. Congress Expressly Approved the Use of

Broad-Based Class Actions in Title VII

Cases ........ ............... .................... ............... 9

3. The Fifth Circuit’s Broad, Policy-Based

Standard Is Consistent with Rule 23....... 14

B. The Artificial and Inflexible Rules Proposed

by General Telephone Are Inconsistent with

the Purposes of both Title VII and Rule 23.... 19

1. The “Commonality” and “Typicality” Re

quirements------- ----------- ------------------- 21

2. The “Adequacy of Representation” Re

quirement .......... ........ ........... ,................... 24

C. The District Court and the Fifth Circuit Cor

rectly Applied Rule 23 in this Case............... 27

CONCLUSION................................... .................... ...... . 30

11

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

Cases: Page

Albemarle Paper Co. v. Moody, 422 U.S. 405

(1975) --------------- .......----- ___ _______ ,1,13-14, 23-24

Alexander v. Gardner-Denver Co., 415 U.S. 36

(1974) ............... 10

Allen, v. Amalgamated Transit Union Local 788,

554 F.2d 876 (8th Cir.), cert, denied, 434 U.S.

891 (1977) .......... 6

American Tobacco Co. v. Patterson, No. 80-1199,

cert, granted, 49 U.S.L.W. 3931 (June 15, 1981).. 14

Arlington Heights v. Metropolitan Housing Devel

opment Corp., 429 U.S. 252 (1977) ...................... 22

Armour v. City of Anniston, 597 F.2d 46 (5th Cir.

1979) , vac. and rem., 445 U.S. 940 (1980)... . 18

Armour v. City of Anniston, 622 F.2d 1226 (5th

Cir. 1980) _______ ______ ________ ________ 18

Armour v. City of Anniston, 654 F.2d 382, 384

(5th Cir. 1981) ............ ...................... ......... ......... 19

Berenyi v. Immigration and Naturalization Serv

ice, 385 U.S. 630 (1967)___________________ 27

Bowe v. Colgate-Palmolive Co., 416 F.2d 711 (7th

Cir. 1969)____________ ____ _______ _______ 8

Camper v. Calumet Petrochemicals, Inc., 584 F.2d

70 (5th Cir. 1978)................................. ............ . 18

Castaneda v. Partida, 430 U.S. 482 (1977) ........... 29

Clark v. Alexander, 489 F.Supp. 1236 (D.D.C.

1980) .......... ......................... ...... ....................... ..... 23

Columbus Board of Education v. Penick, 433 U.S.

449 (1979) .................... ......... ........... .... ............ . 23

Coopers & Lybrand v. Livesay, 437 U.S. 463

(1978)__________________________________ 4

County of Washington v. Gunther, 101 S. Ct. 2242

(1981) _______________ ________________ 10, 13-14

Cox v. Babcock & Wilcox, 471 F.2d 13 (4th Cir.

1972) __ 6

Crawford v. United States Steel Corp., 660 F.2d

663 (5th Cir. 1981) ___ 6

Crawford v. Western Electric Co., Inc., 614 F.2d

1300 (5th Cir. 1980) ................... ......... ........ .... 9, 18, 29

Ill

Davis v. Califano, 613 F.2d 957 (D.C. Cir. 1979)—. 23

Deposit Guaranty National Bank v. Roper, 445

U.S. 326 (1980) .......................... ..... ............. ........ 22

Dothard v. Rawlinson, 433 U.S. 321 (1977) ........ . 14

Du Shane v. Conlisk, 583 F.2d 965 (7th Cir.

1978) ........ .............................................................. 7

East Texas Motor Freight v. Rodriguez, 431 U.S.

395 (1977) ............ .......... ...... .... ..........1,9,17,22,24,26

Ford v. United States Steel Corp., 638 F.2d 753

(5th Cir. 1981) ...... ........... ................ ................. . 19

Franks v. Bowman. Transportation Co., 424 U.S.

747 (1976) .... ................ ......... ........... ............ __.,1,13, 24

Garcia v. Gloor, 618 F.2d 264 (5th Cir. 1980)....... 18

General Building Contractors v. Pennsylvania, No.

81-280, cert, granted, 50 U.S.L.W. 3300 (Oct.

19, 1981)...... ....................... ...... ........ .. ......... ..... . 14, 24

General Telephone Co. v. EEOC, 446 U.S. 318

(1980) .... .............. .................. ......... ............ ...... 9,26-27

Goodman v. Schlesinger, 584 F.2d 1325 (4th Cir.

1978) __________ __ ______________ ______ 6

Griggs v. Duke Power Co., 401 U.S. 424 (1971) ..1, 10, 14

Groves v. Insurance Co. of North America, 433 F.

Supp. 877 (E.D. Pa. 1977)___________ _____ 6

Guardian Association v. Civil Service Commission

of City of New York, No. 81-431, cert, granted,

50 U.S.L.W. 3547 (Jan. 11, 1982) ....................... 14, 24

Hall v. Werthan Bag Corp., 251 F.Supp. 184

(M.D. Tenn. 1966)...... ....... ...... .... ..................... 16-17

Hansberry v. Lee, 311 U.S. 32 (1940) _________ 22

Harris v. Palm Springs Alpine Estates, Inc., 329

F.2d 909 (9th Cir. 1964) ____ __ __________ 7

Hodge v. McLean Trucking Co., 607 F.2d 1118

(5th Cir. 1979) ............. .................. ................... 18

International Brotherhood of Teamsters v. United

States, 431 U.S. 324 (1977) ...................13-14,23-24, 26

James v. Stoekham Valves & Fittings, Inc., 559

F.2d 310 (5th Cir. 1977), cert, denied, 434 U.S.

1034 (1978) .

TABLE OF AU THO RITIES— Continued

Page

23

iv

TABLE OF AU THO RITIES— Continued

Page

Jenkins v. United Gas Corp., 400 F.2d 28 (5th Cir.

1968) ........... ........... ................ ............................... 11-12

Johnson v. Georgia Highway Express, Inc., 417

F.2d 1122 (5th Cir. 1969) ..................... ............ 11, 15-17

Keyes v. School District No. 1, 413 U.S. 189

(1973) ..................................... ........................ ....... 23

King v. Gulf Oil Co., 581 F.2d 1184 (5th Cir.

1978) ........... ............... ............ ............... ....... ....... 19

McDonnell Douglas Corp. v. Green, 411 U.S. 792

(1973) .... ................. ....... .... .......... .............. .... 10, 23-24

Mullaney v. Anderson, 342 U.S. 415 (1952)........... 7

Muskelly v. Warner & Swasey Co., 653 F.2d 112

(4th Cir. 1981) ....... ....... ................................. ..... 6

Norwalk CORE v. Norwalk Redevelopment

Agency, 395 F.2d 920 (2d Cir. 1968) ....... ......... 21

Oatis v. Crown Zellerbach Corp., 398 F.2d 496

(5th Cir. 1968) _____ _____ ______________ 10-12

Payne v. Travenol Laboratories, Inc., 565 F.2d

895 (5th Cir. 1978) _____ ______ ___________ 15, 19

Penson v. Terminal Transport Co., 634 F.2d 989

(5th Cir. 1981) ___________ _____ ___ _____ _ 19

Phillips v. Joint Legislative Committee, 637 F.2d

1014 (5th Cir. 1981)________ __ __________ 26

Potts v. Flax, 313 F.2d 284 (5th Cir. 1963) ....... ... 16-17

Pullman-Standard v. Swint, No. 80-1190, cert.

granted, 49 U.S.L.W. 3788 (April 20, 1981)....... 14

Rivera v. City of Wichita Falls, 665 F.2d 531

(5th Cir. 1982),................... ... ............ ...... ........... 23

Rogers v. Paul, 382 U.S. 198 (1965) ............ ......... 8

Rosado v. Wyman, 322 F.Supp. 1173 (E.D.N.Y.),

aff’d on other grounds, 437 F.2d 619 (2d Cir.),

rev’d on other grounds, 397 U.S. 397 (1970)...... . 22

Rowe v. General Motors Corp., 457 F.2d 348 (5th

Cir. 1972) ___ ________________ _______ _ 29

Royal v. Missouri Highway and Transportation

Comm., 655 F.2d 159 (8th Cir. 1981) ______ _ 23

Sanders v. John Nureen & Co., Inc., 463 F.2d 1075

(7th Cir.), cert, denied, 409 U.S. 1009 (1972).... 6

V

Satterwhite v. City of Greenville, 578 F.2d 987

(5th Cir. 1978) (en banc), vac. and rem., 445

U.S. 940 (1980) ____*...... ............... .................18

Scott v. University of Delaware, 601 F.2d 76 (3d

Cir.), cert, denied, 444 U.S. 931 (1979)___ ___ 25

Shepard v. Beard-Poulan, Inc., 617 F.2d 87 (5th

Cir. 1980) ................... ........................................... 18

Smith v. Liberty Mutual Insurance Co., 569 F.2d

325 (5th Cir. 1978) ....... ... ...... ............................ 18

Sosna v. Iowa, 419 U.S. 393 (1975) ......................... 8

State of Connecticut v. Teal, No1. 80-2147, cert.

granted, 50 U.S.L.W. 3244 (Oct. 5, 1981) ..... ..... 14

Trafficante v. Metropolitan Life Insurance Co.,

409 U.S. 205 (1972) ......... ....... ....... ........... ....... 10

United Air Lines, Inc. v. McDonald, 432 U.S. 385

(1977) ............................. 7

United States v. Johnston, 268 U.S. 220 (1975)__ 27

United States v. United States Steel Corp., 520

F.2d 1043 (5th Cir. 1975), cert, denied, 429

U.S. 817 (1976) ............. ........ .............. ....... .... . 19

United Steelworkers of America v. Weber, 443

U.S. 193 (1979).......................................... 9

Vuyanich v. Republic National Bank of Dallas, 82

F.R.D. 420 (N.D. Tex. 1979)___________ 12

Washington v. Davis, 426 U.S. 229 (1976) ..... ..... . 22, 24

Wells v. Ramsey, Scarlett & Co., 506 F.2d 436

(5th Cir. 1975)______ _______ _____________ 18

Wheeler v. American Home Products Corp., 582

F.2d 891 (5th Cir. 1977) ____ __ ____ ___ _ 6

White v. Dallas v. Independent School District, 581

F.2d 556 (5th Cir. 1978) (en banc) ...... ............ 1

Zipes v. Trans World Airlines, No. 78-1545, Slip

Opinion (Feb. 24, 1982) .......... ............. ............... 6,14

Statutes and Rules:

Fed. R. Civ. P. 15(c) ............................................... 7

Fed. R. Civ. P. 17(a) .................. 7

Fed. R. Civ. P. 21 .................... 2,6-7

Fed. R. Civ. P. 23 ............... passim

TABLE OF AU THO RITIES—Continued

Page

VI

TABLE OF AU THO RITIES— Continued

Page

Equal Employment Opportunity Act of 1972, Pub.

L. 92-261, 86 Stat. 103 (1972) ....... ..................... 11, 13

Fair Labor Standards Act, 29 U.S.C. § 216 (b).... . 9

Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, as

amended, 42 U.S.C. § 2000e et seq. ......... ........... passim

Truth in Lending Act, 15 U.S.C. § 1640(a) ..... ..... 9

42 U.S.C. § 1981 ....,....... ....... ....................... ............. 24

Legislative History:

117 Cong. Rec. 38030 (1971) ...................... .......... 11

118 Cong. Rec. 3808 (1972) ....................... 12

118 Cong. Rec. 4942 (1972) ____ 12

118 Cong. Rec. 4944 (1972) .. ........... 12

118 Cong. Rec. 7166 (1972) ................ 12

118 Cong. Rec. 7168 (1972) ................. 12

118 Cong. Rec. 7564 (1972) ............................... 12

118 Cong. Rec. 7565 (1972) ___ _____ ____ .... 12

S. Rep. No. 867, 88th Cong., 2d Sess. (1964) ......... 10

S. Rep. No. 92-415, 92d Cong., 1st Sess. (1971) ....... 8,12

Subcommittee on Labor of the Senate Committee

on Labor and Public Welfare, Legislative His

tory of the Equal Employment Opportunity Act

of 1972, (GPO: 1972) ............................ .......... . 11

Books and Journals:

.1. Bass, Unlikely Heroes (New York: Simon and

Schuster, 1981) .... ......... ........................................ 10

Belton, Title VII of the Civil Eights Act of 1964:

A Decade of Private Enforcement and Judicial

Developments, 20 St. L.L.J. 225 (1976)........ . 14

Cover, For James Wm. Moore: Some Reflections

on a Reading of the Rules, 84 Yale L.J. 718

(1975) ....................................................... .......... . 10

Developments in the Laiv— Class Actions, 89 Harv.

L. Rev. 1318 (1976) ......... ............. ............. ....... 5,10

Developments in the Law—Employment Discrimi

nation and Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of

1964, 84 Harv. L. Rev. 1109 (1971) ................... 13

Kaplan, Continuing Work of the Civil Committee:

1966 Amendments of the Federal Rules of Civil

Procedure ( /) , 81 Harv. L. Rev. 356 (1967)....... 15-16

3A Moore’s Federal Practice (1979) ........... ........ . 7

3B Moore’s Federal Practice (1981) ____ ___ ___ 21, 25

Note, Antidiscrimination Class Actions Under the

Federal Rules of Civil Procedures: The Trans

formation of Rules 23(b) (2), 88 Yale L.J. 868

(1979) ........ ...................... ..................................... 8

F.T. Read and L.S, McGough, Let Them, Be Judged

(Metuchen, N .J.: Scarecrow Press, 1978)....... 10

Wright and Miller, 7 Federal Practice a,nd Proce

dure (1972) ............. ............. ....... ....... ....... ......... 15, 21

Miscellaneous:

Advisory Comm. Notes, 39 F.R.D. 69 (1966)......... 15

Brief for the United States and the Equal Employ

ment Opportunity Commission as Amici Curiae,

Albemarle Paper Co. V. Moody, Nos. 74-389 and

74-428 ................. ....... ...... ........... ........... ........... . 13

Memorandum for the United States and Equal

Employment Opportunity Commission as Amici

Curiae, East Texas Motor Freight System, Inc.

V. Rodriguez, Nos. 75-651, 75-715, 75-718 ____17, 20-21

Brief for the United States and the Equal Employ

ment Opportunity Commission as Amici Curiae,

Franks V. Bowman Transportation Co., Inc.,

No. 74-728 ..

vii

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES^— Continued

Page

13

I n T h e

(Emtrl xd % HHxntvb

October T e r m , 1981

No. 81-574

Gen er a l T e l e p h o n e Co m pan y of t h e So u t h w e st ,

Petitioner,

M ariano F alcon .

On Writ of Certiorari to the United States Court of Appeals

for the Fifth Circuit

BRIEF OF THE NAACP LEGAL DEFENSE

AND EDUCATIONAL FUND, INC., AND

THE MEXICAN AMERICAN LEGAL DEFENSE

AND EDUCATIONAL FUND, INC.,

AS AMICI CURIAE

INTEREST OF AMICI *

The NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund,

Inc., is a nonprofit corporation whose principal purpose

is to secure the civil and constitutional rights of black

persons through litigation and education. For more than

forty years, its attorneys have represented parties in

thousands of civil rights cases, including many significant

employment discrimination cases before this Court and

the lower courts. See, e.g., Griggs v. Duke Power Co.,

401 U.S. 424 (1971) ; Albemarle Paper Co. v. Moody, 422

U.S. 405 (1975) ; Franks V. Bowman Transportation Co.,

424 U.S. 747 (1976).

* The parties have consented to the filing of this brief. Their

letters of consent have been filed with the Clerk.

2

The Mexican American Legal Defense and Educational

Fund, Inc., is a nonprofit corporation whose principal

purpose is to secure the civil and constitutional rights of

persons of Mexican descent through litigation and educa

tion. Since its founding in 1968, its attorneys have par

ticipated in many lawsuits involving employment dis

crimination in this Court and the lower courts. See, e.g.,

East Texas Motor Freight System, Inc. v. Rodriguez, 431

U.S. 395 (1977) ; White v. Dallas Independent School Dis

trict, 581 F.2d 556 (5th Cir. 1978) (en banc).

Amici believe that the Court’s decision in the case at bar

may affect their representation of minorities in future

cases. Amici further believe that their experience in em

ployment litigation will assist the Court in this case.

SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT

Petitioner raises far-ranging issues of law and policy

under Title VII and Rule 23. Seeking broad and severely

restrictive pronouncements on these issues, Petitioner in

vents a straw man—the totally unsubstantiated “across-

the-board” class action—and urges the Court to tear it

apart with artificial and inflexible rules that would

severely undermine the ability of lower courts to exercise

discretion in the application of Rule 23 to class action

determinations and in the use of case management de

vices in Title VII actions.

1. This is not an appropriate case in which to make

such far-reaching decisions. The central issue of whether

a class action is proper in this case may be reconsidered

by the district court on remand from the Fifth Circuit.

There is a substantial question as to satisfaction of the

numerosity requirement of Rule 23(a) (1), which was not

addressed by the Fifth Circuit or raised by Petitioner

here, since it now appears that there are at most 13 class

members. The district court might well choose to enter

tain the claims of those 13 individuals by joining them

under Rule 23(d) (2) or Rule 21. In any event, this case

is a poor vehicle for this Court to use in prescribing gen

3

eral standards for the hundreds of Title VII class actions

brought each year in the lower courts. The writ should

therefore be dismissed as improvidently granted.

2. Broad class actions are not only permissible in em

ployment discrimination actions where the requirements

of Rule 23 are met, but are favored as a matter of na

tional policy and congressional intent. Congress has rec

ognized that discrimination, where it exists, is inherently

based on class-wide characteristics, and has approved the

use of class actions to extfli^ate such discrimination.

Broad civil rights actions are also fully consistent with

the purpose of Rule 23.

3. The Fifth Circuit has conscientiously and carefully

applied Rule 23 in determining whether broad class treat

ment is proper for particular employment discrimination

cases. It has never dispensed with the requirement that

the criteria of Rule 23(a) be met as a prerequisite to the

maintenance of Title VII class actions, nor would propo

nents of Title VII enforcement suggest such a course.

But equally important, the specific requirements of Rule

23(a) must not be construed so rigidly or narrowly that

class actions are eliminated or that district courts lose the

discretion to apply Rule 23(a) properly to the facts of

each case. The rules proposed by Petitioner—such as the

artificial axioms that an employee can never properly

represent a job applicant, or that a plaintiff whose case

is decided under disparate-treatment theory can never

represent a class whose claims are based on disparate-

impact analysis:—would flatly prohibit many types of

Title VII class actions that are often found proper by the

lower courts.

4. The Fifth Circuit properly applied Rule 23 in this

case. Its affirmance of the district court’s class deter

mination, subject to reconsideration, was based on evi

dence meeting the requirements of Rule 23. Petitioner’s

attack on the ruling below as based only on a presump

tion in favor of across the board class actions is mis

directed.

ARGUMENT

I. THE WRIT SHOULD BE DISMISSED AS IMPROVI-

DENTLY GRANTED.

The questions presented and the arguments made by

General Telephone and the Department of Justice raise

critical issues concerning the application of the class ac

tion procedure of Rule 23, Fed. R. Civ. P., to actions

brought under Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964,

as amended, 42 U.S.C. § 2000e el seq., and other civil

rights laws. Amici submit that this case does not provide

an appropriate basis for resolving these critical issues.

We therefore urge the Court to dismiss the writ of cer

tiorari as improvidently granted.

First, the merits of the class case were remanded to the

district court for a reconsideration of the plaintiffs’ and

defendants’ statistics and the sufficiency of the evidence

to support a finding of hiring discrimination. That re

consideration may well result in narrowing the class held

to have been affected by discriminatory hiring practices.1

Therefore, the original class determination may be sub

ject to reconsideration. The current class certification

order is subject to revision both under the provisions of

Rule 23(c) (1) and by the language of the order itself

which stated, “. . . Defendant may at any time raise the

issue of this provisionally-certified class during or after

the presentation of the class claims and evidence at trial.”

App. 51a. The issues in this case are not ripe for this

Court’s review until there has been a final judgment on

the merits.2

4

1 The court of appeals suggested that the period in which hiring

discrimination occurred may have ended earlier than originally

found by the district court. The case was remanded for a deter

mination of the extent of that period. Appendix to the Petition for

a Writ of Certiorari, pp. 27a-28a. (“App,”). Class membership will

be affected by that determination.

2 See Coopers & Lybrand V. Livesay, 437 U.S. 463 (1978). It is

particularly inappropriate for the Court to exercise its discretion

to review this interlocutory order since there are few universally

5

Second, in the present case the issue of whether the

case is properly a class action may well be moot. At the

time the class was provisionally certified prior to the

Phase I liability determination, the numerosity require

ment of Rule 23(a) (1) was apparently met. However,

a fte r a finding of liability for hiring discrimination at

Phase I of the trial, only 13 individuals filed proof-of-

claim forms to receive back pay and job security awards.

Only those individuals were considered members of the

class seeking relief a t the Phase II trial. The existence

of a class too numerous for individual joinder to be prac

ticable has been considered perhaps the most fundamental

requirement of Rule 23. Developments in the Law— Class

Actions, 89 Harv. L. Rev. 1318, 1454 (1976). Here i t is

obvious that joinder is practicable since all the individuals

who comprise the class are in effect joined. This Court’s

review is unnecessary to disposition of the class members’

claims because the merits of the class hiring discrimina

tion case were remanded to the tria l court and the inter

ests of the 13 persons before tha t court will not depend

on whether there is a class action.3 The issues presented

and arguments made by General Telephone seek, in effect,

an advisory opinion in favor of other employers, limiting

other plaintiffs’ ability to m aintain broad class actions.4

applicable answers to the difficult and fact-sensitive problems faced

by the district courts in applying- Rule 23. Each party seeking to

obtain certification of a broad class action is required to satisfy the

criteria of Rule 23 based on the facts of that party’s ease. Whether

an employee can represent applicants in an employment discrimina

tion action should therefore be determined on a case by case basis,

not according to any inflexible rule. In this case the district court

on remand may and indeed should reconsider whether Rule 23 (a) Is

satisfied. While amici believe that the district court may properly

hold that Falcon is a proper representative of the class, see Section

II,C, infra, that issue is not appropriate for determination on this

record by this Court.

3 If class certification were revoked, the 13 individuals would ap

parently remain in the case as intervenors. See text infra.

4 The district court in the present case certified a class of Hispanic

employees “who are employed and employees [sic] who have applied

6

The present case should be remanded to the trial court

for a determination of whether the 13 individual claim

ants should be allowed to intervene in the action pursuant

to Rule 23(d) (2) or should be joined as plaintiffs pur

suant to Rule 21, Rule 23(d) (2) provides that the Court

may order that notice be given to class members allow

ing them to intervene. Intervention in class actions is

permitted by the Rule to strengthen the adequacy of rep

resentation of the class15 and can be allowed even though

the proposed intervenor is already an adequately repre

sented class member.5 6 In employment discrimination

cases, intervention by an applicant in a class action

brought by an incumbent employee is proper.7 The inter

veners are not required to exhaust administrative reme

dies if the plaintiff or one or more class members have

done so.8 On remand, the trial court may notify the 13

applicants of their right to intervene in this case to pro

tect their interests and to strengthen the representation

of the class. Such intervention may be allowed whether

for employment in. the Irving Division of the Defendant Company,

and no other division.” App. 48a. This case presents no issues con

cerning the application of Rule 23 to a class which includes future

applicants and employees. The class certified here included only

present and former applicants and employees, and aside from plain

tiff Falcon, only 13 such persons were found to be entitled to any

relief.

5 Sanders V. John Nuveen & Co., Inc., 463 F.2d 1075 (7th Cir.),

cert, denied, 409 U.S. 1009 (1972).

6 Groves V. Insurance Co. of North America, 433 F.Supp. 877

(E.D. Pa. 1977).

7 Muskelly v. Warner & Swasey Co., 653 F.2d 112 (4th Cir. 1981).

Cf. Goodman V. Schlesinger, 584 F.2d 1325 (4th Cir. 1978); Cox V.

Babcock & Wilcox, 471 F.2d 13 (4th Cir. 1972).

8 Wheeler v. American Home Products Corp., 582 F.2d 891, 897

(5th Cir. 1977) ; Allen v. Amalgamated Transit Union Local 788, 554

F.2d 876 (8th Cir.), cert, denied, 434 U.S. 891 (1977) ; see Crawford

V. United States Steel Corp., 660 F.2.d 663, 665-666 (5th Cir. 1981) ;

Zipes V. Trans World Airlines, Inc., No. 78-1545, Slip Opinion, p. 7

(Feb. 24, 1982) (the “filing [of] a timely charge . . . with the EEOC

is not a jurisdictional prerequisite”).

or not the class representative continues to meet the re

quirements of Rule 23.

Joinder of the 13 individual applicants pursuant to

Rule 21 would also be proper in this case.® Under this

Rule, a party can be added sua sponte by the court for

remedial purposes even after judgment.9 10 Indeed, this Court

has added parties under Rule 21 on appeal. Mullaney v.

Anderson, 342 U.S. 415, 417 (1952). Since the original

suit brought by Falcon in 1972 was timely commenced,

joinder of the 13 individual applicants would relate back

to the date of the original pleading and would not be

barred by the statute of limitations.11

Considering the small number of individuals whose in

terests are presently before the Court and the practica

bility of joinder in this case, a remand to the district

court for intervention or joinder of the parties would

adequately protect their interests. In view of the Fifth

Circuit’s remand for reconsideration of the merits of the

case, and in view of the district court’s ability to recon

sider the class ruling under its own order and Rule

23(c) (1), this case does not present an appropriate basis

for determining the important class action issues raised

by Petitioner. Since this Court’s decision is unnecessary

to the just disposition of the claims of members of the

class whose existence is contested by Petitioner, amici

submit that the writ of certiorari was improvidently

granted and should be dismissed.

7

9 Rule 21 should be construed consistently with other rules which

in substance provide for adding parties and bear a relation to

changes in class actions under Rule 23. See Harris V. Palm Springs

Alpine Estates, Inc., 329 F.2d 909 (9th Cir. 1964). The proper

inquiry under Rule 21 is whether joinder will prejudice the non

moving party and whether it will serve to avoid the multiplicity of

suits. 3A Moore’s Federal Practice, jj 21.04[1], p. 21-25.

10 Du Shane V. Conlisk, 583 F.2d 965, 967 (7th Cir. 1978).

11 Rules 15 (C) and 17(a), Fed. R. Civ. P. See United Air Lines,

Inc. v. McDonald, 432 U.S. 385 (1977).

8

II. A TITLE VII CLASS ACTION MAY PROPERLY BE

MAINTAINED ON BEHALF OF A BROAD CLASS

WHEN THE REQUIREMENTS OF RULE 23 ARE

SATISFIED.

A The Fifth Circuit’s Standard Permitting Certifica

tion of Broad Classes in Employment Discrimina

tion Actions Is Consistent with the Class-Based

Nature of Discrimination, and it Effectuates the

Purposes of both Title VII and Rule 23.

1. Unlawful Discrimination Is Class-Based.

Where an employer maintains a policy of discriminat

ing against a racial or ethnic group, that policy affects

all members of that group who either work for the em

ployer or seek to work for the employer. As the Senate

Committee on Labor and Public Welfare recognized in its

report on the bill which became the Equal Employment

Opportunity Act of 1972:

The committee agrees with the courts that title VII

actions are by their very nature class complain [t] s,

and that any restriction on such actions would greatly

undermine the effectiveness of title VII.

S. Rep. No. 92-415, 92d Cong., 1st Sess. 27 (1971) (foot

note omitted). Just as this Court has held that black

students may challenge discrimination in faculty employ

ment to vindicate their interest in securing an educational

environment free from all forms of racial discrimination,

Rogers V. Paul, 382 U.S. 198, 200 (1965), so also may

black and Hispanic workers challenge discrimination in

all aspects of their work environment. See Sosna v. Iowa,

419 U.S. 393, 413 n.l (1975) (White, J., dissenting) ;

Note, Antidiscrimination Class Actions Under the Federal

Rules of Civil Procedure: The Transformation of Rule

23(b)(2), 88 Yale L.J. 868, 886 (1979).

In applying Title VII, the courts are necessarily con

fronted with the task of dealing with class discrimina

tion. “ [T]he evil sought to be ended is discrimination on

the basis of a class characteristic . . . .” Bowe V. Colgate-

9

Palmolive' Co., 416 F.2d 711, 719 (7th Cir. 1969). Of course,

“ [t]he fact that plaintiffs are members of the same race

as the other employees and rejected job applicants . . . is

not enough in itself to require a finding under Rule 23

that their representation was adequate or that their

claims were typical of the class.” Crawford v. Western

Electric Co., 614 F.2d 1300, 1304 (5th Cir. 1980). But

“. . . suits alleging racial or ethnic discrimination are

often by their very nature class suits, involving classwide

wrongs. Common questions of law or fact are typically

present.” East Texas Motor Freight System, Inc. v. Rod

riguez, 431 U.S. at 405. The class-based nature of dis

crimination should inform and guide a court’s discre

tionary determination as to whether an action should pro

ceed on a class basis.12

2. Congress Expressly Approved the Use of Broad-

Based Class Actions in Title VII Cases.

The Civil Rights Act of 1964 was designed to eliminate

pervasive racial and ethnic discrimination and the ad

verse social and economic consequences of that discrimina

tion. United Steelworkers of America v. Weber, 443 U.S.

193, 202 (1979). In enacting Title VII of that Act, Con

gress did not specifically address the use of class actions

in enforcing the law against discrimination in employ

ment.13 However, Congress “considered the policy against

12 In its brief amicus curiae in the present case, the Justice De

partment fails to discuss both the class-based nature of employment

discrimination and the relevant legislative history of Title VII.

However, in a series of briefs to this Court over the course of the

past decade, the Government has specifically emphasized these con

siderations in related class action contexts. See nn. 16, 22, 25,

infra. We note that the Justice Department’s concern with Rule 23

as a litigant in Title VII cases is solely as a defendant, see General

Telephone Co. v. EEOC, 446 U.S. 318 (1980), and that the Equal

Employment Opportunity Commission declined to sign the brief

filed by the Justice Department in the present case.

is while some statutes have specific provisions governing class

actions, see, e.g., the Fair Labor Standards Act, 29 U.S.C. § 216(b),

and the revised Truth in Lending Act, 15 U.S.C. § 1640(a), gen

erally Congress does not consider the place of class actions in the

10

discrimination to be of the ‘highest priority’,” Alexander

V. Gardner-Denver Co., 415 U.S. 36, 47 (1974),

and “indicated [that] a ‘broad approach’ to the definition

of equal employment opportunity is essential to overcom

ing and undoing the effect of discrimination.” County of

Washington V. Gunther, 101 S. Ct. 2242, 2252 (1981),

citing S. Rep. No. 867, 88th Cong., 2d Sess. 12 (1964).

See Trafficante v. Metropolitan Life Insurance Co., 409

U.S. 205, 209 (1972). As this Court stated in Griggs v.

Duke Power Co., supra, “Congress provided in Title VII

of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, for class actions for en

forcement of provisions of the Act,” id. at 425, and “ [t]he

objective of Congress in the enactment of Title VII . . . .

was to achieve equality of employment opportunities and

remove barriers that have operated in the past to favor an

identifiable group of white employees over other em

ployees.” Id. at 429-30 (emphasis added). See also Mc

Donnell Douglas Corp. V. Green, 411 U.S. 792, 800-01

(1973).

Soon after the passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964,

the courts of appeals were called upon to determine the

proper application of class action procedures to Title VII

cases. As in other areas of racial discrimination law, the

Fifth Circuit led the way.14 In Oatis v. Crown Zellerbach

Corp., the first appellate application of Rule 23 to a Title

VII case, the Fifth Circuit recognized that

[rjacial discrimination is by definition class discrim

ination, and to require a multiplicity of separate,

identical charges before the EEOC, filed against the

same employer, as a prerequisite to relief through

statutory enforcement scheme. Developments in the Law—Class

Actions, 89 Harv. L. Rev. at 1359. Therefore, in applying the class

action device to a particular statutory scheme, the courts ordinarily

must look to the policy underlying the statute. See generally Cover,

For James Wm. Moore: Some Reflections on a Reading of the

Rides, 84 Yale L. J. 718 (1975).

See F.T. Read and L.S. McGough, Let Them Be Judged

(Metuchen, N .J.: Scarecrow Press, 1978); J. Bass, Unlikely Heroes

(New York: Simon and Schuster, 1981),

11

resort to the court would tend to frustrate our system

of justice and order.

398 F.2d 496, 499 (5th Cir. 1968) ; see also Jenkins V.

United Gas Corp., 400 F.2d 28 (5th Cir. 1968). In 1969,

the Fifth Circuit applied the rationale of Oatis and

Jenkins in concluding that in appropriate circumstances

Rule 23 would permit “an ‘across the board’ attack on

unequal employment practices alleged to have been com

mitted by the appellee pursuant to its policy of racial

discrimination.” Johnson V. Georgia Highway Express,

Inc., 417 F.2d 1122, 1124 (5th Cir. 1969). The Court

determined that Title VII and Rule 23 would be best

served by a broad approach to the use of class actions in

fair employment cases. Id. Three years later, Congress

indicated its approval of the Fifth Circuit’s approach. In

1972, Congress amended Title VII by enacting the Equal

Employment Opportunity Act of 1972. The bill which

originally passed the House precluded class actions by

providing that

[n]o order of the court shall require the admission

or reinstatement of an individual . . . or the payment

to him of any back pay, if such individual . . .

neither filed a charge nor was named in a charge or

amendment thereto. . . ,15

The Senate Committee on Labor and Public Welfare

specifically reviewed and rejected the restrictions on class

actions proposed by the House bill. That committee re

ported out a bill known as the “William bill,” S. 2515,

which did not place any restriction on class actions. 117

Cong. Rec. 38030 (1971). The committee’s report stated

that the bill

is not intended in any way to restrict the filing of

class complaints. The committee agrees with the

courts that title VII actions are by their very nature

class complain [t] s,1'6 and that any restriction on such 16

16 Subcommittee on Labor of the Senate Committee on Labor and

Public Welfare, Legislative History of the Equal Employment Op

portunity Act of 1972 at 332 (GPO: 1972).

12

actions would greatly undermine the effectiveness of

title VII.

S. Rep. No. 92-415, 92d Cong., 1st Sess. 27 (1971). In

footnote 16, the Committee cited with approval the Fifth

Circuit’s decisions in Oatis and Jenkins. After agreeing

to a compromise substitute bill, 118 Cong. Rec. 3808

(1972), Senator Williams placed in the record a section-

by-section analysis explaining his bill as amended. This

analysis demonstrates that the Senate committee’s original

position favoring class actions was preserved:

it is not intended that any of the provisions contained

[in § 706] are designed to affect the present use of

class action lawsuits under Title VII in conjunction

with Rule 23 of the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure.

The courts have been particularly cognizant of the

fact that claims under Title VII involve the vindica

tion of a major public interest, and that any action

under the Act involves considerations beyond those

raised by the individual claimant. As a consequence,

the leading cases in this area to date have recognized

that Title VII claims are necessarily class action

complaints. . . .

118 Cong. Rec. 4942 (1972). See 118 Cong. Rec. 7166,

7564. The Williams bill then passed the Senate. 118

Cong. Rec. 4944 (1972).

In reconciling S. 2515 with H.R. 1746, the conference

committee adopted the Senate position on class actions.

The section-by-section analysis of that committee’s agree

ment recites the language quoted just above in its entirety

and adds: “A provision limiting class actions was con

tained in the House Bill and specifically rejected by the

conference committee.” 118 Cong. Rec. 7168, 7565

(1972).

The congressional policy underlying the enactment of

Title VII in 1964 and the express legislative history of the

1972 amendments demonstrate Congress’ intention that

the class action device be fully used in Title VII actions.

Vuyanich v. Republic National Bank, 82 F.R.D. 420, 429-

30 (N.D. Tex. 1979). The broad approach to Title VII

13

class actions adopted by the Fifth Circuit, followed by

other courts, and approved by Congress “goes a long way

toward effectuating the public interest.” Developments

in the Law—Employment Discrimination and Title VII of

the Civil Rights Act of 196k, 84 Harv. L. Rev. 1109, 1220

(1971).16

General Telephone disputes the relevance of the 1972

legislative history. Brief, p. 43 n.97. It is true that, in

interpreting § 703(h) of Title VII, this Court has relied

upon the legislative history of the 1964 Act and not the1

1972 Act. County of Washington V. Gunther, 101 S. Ct.

at 2251 n.16; International Brotherhood of Teamsters v.

United States, 431 U.S. 324, 354 n.39 (1977). However,

the legislative history of the 1972 Act was deemed of little

relevance in those cases because Congress did not amend

or reenact § 703(h) in 1972. Equal Employment Oppor

tunity Act of 1972, Pub. L. No. 92-261, 86 Stat. 103.

However, the provisions authorizing Title VII actions by

private litigants are contained in § 706, which was

amended and reenacted in 1972. Accordingly, the Court

should look to the legislative history of the 1972 Act in

construing § 706 in the present case, as it has looked to

the legislative history of the 1972 Act in construing § 706

in other cases. See Franks V. Bowman Transportation

Co., 424 U.S. at 763-64; Albemarle Paper Co. v. Moody,

422 U.S. at 414 (maintainability of class actions under

16 In previous cases the Solicitor General has relied on the legisla

tive history of the 1972 amendments—stating, for example, that

“any restriction on [class] actions would greatly undermine the

effectiveness of Title VII”—as indicating the broad approach to

class actions mandated by Congress. Brief for the United States and

the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission as Amici Curiae,

Albemarle Paper Co. V. Moody, Nos. 74-389 and 74-428, p. 33, quot

ing S. Rep. No. 92-415, 92d Cong. 1st Sess. 27 (1972) ; Brief for the

United States and the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission

as Amici Curiae, Franks v. Bowman Transportation Co., No. 74-728,

p. 22. In stating the views of the Justice Department in this case,

the Solicitor General did not refer to any of the legislative history

on which his. predecessors relied in determining the appropriate ap

plication of the class action procedure to Title VII cases.

Title V II); Zipes V. Trans World Airlines, No. 78-1545,

Slip Opinion at 8.

Finally, General Telephone argues that allowing “pri

vate attorneys general” to bring broad-based class actions

undermines the purposes of Title VII. Brief, pp. 30-40.

First, as the prior discussion indicates, Congress has de

termined otherwise, and the Court should decline the com

pany’s invitation to second-guess Congress. Second, Gen

eral Telephone is wrong. Private enforcement actions, and

especially private class actions, have been the primary

mechanism for developing and enforcing Title VII law.

Belton, Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964-: A

Decade of Private Enforcement and Judicial Develop

ments, 20 St. L. L.J. 225 (1976). In fact, with the single

exception of Teamsters V. United States, all of the land

mark Title VII decisions of this Court announcing the

standards for proving and remedying systemic discrimi

nation have been made in cases brought by private plain

tiffs.17

14

3. The Fifth Circuit’s Broad, Policy-Based Stand

ard Is Consistent with Rule 23.

The Fifth Circuit’s broad approach to Title VII class

actions is based on its recognition that most actions at

tacking “unequal employment practices alleged to have

been committed . . . pursuant to [a] policy of racial dis

crimination” raise common questions of fact and law and

present claims which may be addressed in a class action,

17 See, e.g., Griggs V. Duke Power Co.; Albemarle Paper Co. v.

Moody, Franks v. Bowman Transportation Cor, Dothard v. Rawlin-

son, 433 U.S. 321 (1977) ; County of Washington V. Gunther. More

over, the Court has granted certiorari in five currently pending cases

involving issues of systemic discrimination. Every one of those cases

was initially brought by private plaintiffs, State of Connecticut V.

Teal, No. 80-2147, 50 U.S.L.W. 3244 (Oct. 5, 1981); Pullman-

Standard V. Swint, No. 80-1190, 49 U.S.L.W. 3788 (April 20, 1981);

American Tobacco Co. V. Patterson, No. 80-1199, 49 U.S.L.W. 3931

(June 15, 1981) ; General Building Contractors v. Pennsylvania,

No. 81-280, 50 U.S.L.W. 3300 (Oct. 19, 1981) ; Guardians Associa

tion V. Civil Service Commission of the City of New York, No. 81-

431, 50 U.S.L.W. 3547 (Jan. 11, 1982).

15

even where the specific discriminatory practices which

flow from that policy may affect class members in differ

ent ways. This standard is aptly characterized as policy-

based : the scope of the class may be defined by the reach

of the effects of the employer’s policy of employment dis

crimination. Johnson V. Georgia Highway Express, 417

F.2d at 1124; see also App. 12a, quoting Payne V. Trave-

nol Laboratories, Inc., 565 F.2d 895, 900 (5th Cir. 1978).

The Fifth Circuit’s application of Rule 23 in Johnson

and subsequent cases is consistent with the basic policies

which guided the revision of Rule 23 in 1966. As the

Advisory Committee on the Federal Rules stated in its

Note concerning amended Rule 23(b) (2) :

Action or inaction is directed to a class within the

meaning of this subdivision even if it has taken effect

or is threatened only as to one or a few members of

the class, provided it is based on grounds which have

general application to the class.

Illustrative are various actions in the civil-rights

field where a party is charged with discriminating

unlawfully against a class, usually one whose mem

bers are incapable of specific enumeration.

39 F.R.D. 69, 102 (1966).

Rule 23 is not intended to restrict a class action only

to those individuals who each suffer the effects of a policy

of racial discrimination in precisely the same way. An

action meets the requirements of Rule 23(b) (2) and the

requirements of Rule 23(a)18 “even if [the challenged

policy] has taken effect or is threatened only as to one

or a few members of the class. . . .” Moreover, the Rule

“is intended to function as an effective vehicle for the

bringing of suits alleging racial discrimination.” Wright

and Miller, 7 Federal Practice and Procedure § 1771,

p. 662 (1972). See Kaplan, Continuing Work of the Civil

18 An action described in the Advisory Committee’s Notes as meet

ing the requirements of Rule 23(b) would also meet the require

ments of Rule 23(a). Rule 23(b) only becomes relevant if the

requirements of Rule 23(a) have been satisfied.

16

Committee: 1966 Amendments of the Federal Rules of

Civil Procedure (I), 81 Harv. L. Rev. 356, 389 (1967).19

In reaching its decision on the permissible scope of

Title YII class actions in Johnson V. Georgia Highway

Express, the Fifth Circuit relied upon Potts V. Flax, 313

F.2d 284 (5th Cir. 1963), and Hall V. Werthan Bag Corp.,

251 F.Supp. 184 (M.D. Tenn. 1966). A broad class action

was permitted in Potts V. Flax because “ [i]t sought ob

literation of the policy of system wide racial discrimina

tion,” even though this required the issuance of “suitable

declaratory orders and injunctions against any rule, reg

ulation, custom or practice having any such consequence.”

313 F.2d at 289 (emphasis added). In Hall v. Werthan

Bag Corp., the court held that a class could properly

include both applicants and incumbent employees since

both suffered from aspects of a discriminatory policy:

Racial discrimination is by definition a class dis

crimination. If it exists, it applies throughout the

class. This does not mean, however, that the effects

of the discrimination will always be felt equally by

all the members of the racial class. For example, if

an employer’s racially discriminatory preferences are

merely one of several factors which enter into em

ployment decisions, the unlawful preferences may or

may not be controlling in regard to the hiring or

promotion of a particular member of the racial class.

But although the actual effects of a discriminatory

policy may thus vary throughout the class, the ex

istence of the discriminatory policy threatens the

entire class. And whether the Damoclean threat of

a racially discriminatory policy hangs over the racial

class is a question of fact common to all the members

of the class.

251 F.Supp. at 186.

19 Professor Kaplan stated that the “new subdivision (b)(2),

[was built] on experience mainly, but not exclusively, in the civil

rights field.” Since Professor Kaplan was the reporter to the Ad

visory Committee from its organization in 1960 until July 1, 1966,

his article is generally accorded authoritative status.

17

The Advisory Committee specifically cited Potts V. Flax,

and Professor Kaplan specifically cited Hall v. Werthan

Bag Corp.,20 as illustrative of the appropriate use of the

class action rule.21 In both Potts and Hall, as in Johnson

and the present case, the courts approved class actions

whose scope was determined by the full reach of a policy

of racial discrimination, not by only one manifestation of

that policy. The Fifth Circuit’s policy-based approach

permits class actions to proceed, where Rule 23 is satis

fied, in a manner which deals effectively with the class-

based nature of employment discrimination,22 and which

satisfies the congressional goal of terminating the prac

tices and effects of discrimination as quickly, thoroughly

and efficiently as possible.

General Telephone argues that the Fifth Circuit has

ignored Rule 23 in Title VII cases. To the contrary, the

Fifth Circuit has applied its policy-based approach in a

20 Advisory Committee Note, 39 F.R.D. at 102; Kaplan, Continuing

Work of the Civil Committee: 1966 Amendments of the Federal

Rules of Civil Procedure ( /) , 81 Harv. L. Rev. at 389 n.128.

21 In its brief amicus curiae in support of General Telephone,

Republicbank Dallas correctly observes that the “origin of the

across-the-board approach was Potts v. Flax. . . Brief, p. 17 n.10.

However, the Republicbank Dallas argues that this decision pre

ceded the amendment of Rule 23 and contravenes the commonality

and typicality requirements of the Rule as amended. Id. This argu

ment illustrates the “180-degree-wrong way” approach to Rule 23

proposed by Republicbank Dallas and General Telephone. Both the

Advisory Committee Notes and the authoritative article by the

reporter for that Committee expressly approved Potts v. Flax as

the type of class action Rule 23 was designed to permit. See n.2ft

supra.

22 The Government has previously agreed that “ [m]ost Title VII

actions are by their very nature class actions, since they involve

claims of discrimination on the basis of class characteristics.”

Memorandum for the United States and Equal Employment Op

portunity Commission as Amici Curiae, East Texas Motor Freight

System, Inc. v. Rodriguez, Nos. 75-651, 75-715, 75-718, p. 14. The

Court’s opinion in Rodriguez endorsed the Government’s position on

this issue. 431 U.S. at 405.

18

manner fully consistent with Rule 23. In its only en banc

decision on a Title VII class action issue since Rodriguez,

the Fifth Circuit held that the named plaintiff could not

represent a class because she “has never suffered any

legally cognizable injury . . . in common with the

class. . . .” Satterwhite V. City of Greenville, 578 F.2d

987, 992 (1978), vac. and rem., 445 U.S. 940 (1980).

In Satterwhite the en banc court stated that “the con

tinued vitality of [Rule 23] depends upon compliance with

the procedural requirements of Rule 23 and the constitu

tional mandates of Article III.” 578 F.2d at 998. The

Fifth Circuit has repeatedly stressed in Title VII actions

that “ [w] hether a class should be certified depends entirely

on whether the [proposed class] satisfies the requirements

of Fed. R. Civ. P. 23.” Garcia V. Gloor, 618 F.2d 264,

267 (1980) ; Crawford V. Western Electric Co., 614 F.2d

at 1304.

Moreover, far from applying a blanket rule approving

class actions in all Title VII cases, the Fifth Circuit has

often held that class actions should not be certified where

specific requirements of Rule 23(a) have not been met.

That court has ruled, for example, that Title VII actions

could not be maintained as class actions because of a

failure to satisfy the “numerosity” requirement of Rule

23(a) (1), Garcia V. Gloor, 618 F.2d at 267; Hodge v.

McLean Trucking Co., 607 F.2d 1118, 1121 (1970) ; the

“commonality” and “typicality” requirements of Rules

23(a)(2) and (3), Shepard v. Beard-Poulan, Inc., 617

F.2d 87, 89-90 (1980) ; Armour V. City of Anniston, 597

F.2d 46, 50 (1979);23 Camper v. Calumet Petrochemicals,

Inc., 584 F.2d 70, 71-72 (1978); Smith v. Liberty Mutual

Insurance Co., 569 F.2d 325, 329-30 (1978) ; and the

“adequacy of representation” requirement of Rule 23(a)

(4), Crawford v. Western Electric Co., 614 F.2d at 1304-

05; Wells v. Ramsey, Scarlett & Co., 506 F.2d 436, 437 23

23 Like the decision in Satterwhite, the Fifth Circuit’s decision in

Armour was vacated and remanded, 445 U.S. 940 (1980). See

Armour v. City of Anniston, 622 F.2d 1226 (1980).

19

(1975). The Fifth Circuit has also determined that named

representatives failed to carry their burden of demon

strating that the action should proceed on a class basis,

King v. Gulf Oil Co., 581 F.2d 1184, 1186 (1978),

Armour V. City of Anniston, 654 F.2d 382, 384 (1981),

and that the “standing” requirement may limit the relief

to which a class is entitled, Payne v. Travenol Labora

tories, 565 F.2d at 898. Finally, the Fifth Circuit has

carefully instructed lower courts in using the broad array

of devices available under Rule 23 to insure that Title VII

class actions proceed manageably and appropriately.

United States v. United States Steel Corp., 520 F.2d 1043,

1050-52 (1975), cert, denied, 429 U.S. 817 (1976) (sub

classes) ; Penson v. Terminal Transport Co., 634 F,2d 989,

994 (1981) (notice and opt-out provisions); Ford V.

United States Steel Corp., 638 F.2d 753, 761-62 (1981)

(substitution of named representatives).24

B. The Artificial and Inflexible Rules Proposed by

General Telephone Are Inconsistent with the Pur

poses of both Title VII and Rule 23.

General Telephone incorrectly argues that the Fifth

Circuit has misapplied the commonality, typicality and

adequacy requirements of Rule 23(a). In order to correct

this imagined pattern of judicial abuse, General Tele-

24 General Telephone also attempts to cast doubt on the impartial

ity of the Fifth Circuit’s application of Rule 23 in fair employment

cases. The company states that the Fifth Circuit “has not reversed

a district court class certification based on the across the board

presumption.” Brief, p. 10 n.5. First, the Fifth Circuit has rarely

had an opportunity to consider a defendant’s claim that a district

court’s class certification decision in a Title VII case was improper.

We are aware of only two such cases. In United States v. United

States Steel Corp., the Fifth Circuit vacated the district court’s

class certification and remanded for a further determination as to

the appropriateness of the action proceeding on a class basis. 520

F.2d at 1050-51. The second case is the one presently before this

Court. Moreover, the Fifth Circuit on numerous occasions, as indi

cated in the text, has ruled against a plaintiff’s claim that a lower

court’s refusal to certify a class was improper.

20

phone invites this Court to apply a series of rigid rules

to prohibit the maintenance of Title VII class actions in

many circumstances: (1) A plaintiff who has suffered

from an employer’s discriminatory policy may not rep

resent employees who have also so suffered if the plain

tiff suffered from a practice defined as unlawful under a

“discriminatory impact” theory while the other employees

suffered from a practice defined as unlawful under a “dis

criminatory treatment” theory, Brief, pp. 24-25; (2)

Even if the plaintiff and other employees all suffer from

illegal discriminatory treatment, the plaintiff may not

represent the other employees where different company

managers or supervisors were responsible for the treat

ment, Brief, p.27; (3) Even if the plaintiff and other

employees all suffer from illegal use of criteria that have

a discriminatory impact and are unrelated to job perfor

mance, the plaintiff may not represent the other em

ployees where the criteria are different, Brief, p. 26; and

(4) Even if the plaintiff and prospective class members

suffered from the same form of discrimination (whether

discriminatory impact or discriminatory treatment) and

from the same application of the discrimination (whether

the same criteria or the same company manager), a

plaintiff who is presently employed may not represent a

class containing applicants as well as employees because

there is a potential conflict between the interests of the

plaintiff and the class. Brief, pp. 27-28.20 25

25 The Justice Department, while rejecting General Telephone’s

“conflict of interest” rule as overly restrictive, Brief, p. 19 n.17,

has proposed its own rigid rule^or Title VII class actions: “The

named plaintiff may represent a class only if the proof he will make

with respect to the employment practice he attacks is substantially

probative of the discrimination allegedly practiced against the class

as a whole.” Id., p. 16; see id., pp. 18-19. The Justice Department

has apparently devined new meaning in Rules 23(a) (2) and (3)

since 1976, when it noted “confusion as to the interpretation of the

typicality provision” and doubt as to whether “it imposes an in

dependent requirement in addition to other provisions of Rule

23(a)” and, most importantly, noted that “ [m]ost Title VII actions

are by their very nature class actions, since they involve claims of

21

1. The “Commonality” and “Typicality” Require

ments.

The requirements of commonality and typicality do not

inexorably lead, as General Telephone would have it, to

a rigid set of universal rules. The commonality require

ment of Rule 23 (a) (2)

seems unnecessary, since, in addition to the prerequi

sites of subdivision (a), an action can be maintained

as a class action under Rule 23 only if it satisfies the

requirements of at least one of the three types of

class actions provided for by subdivision (b).

. . . [T]he existence of common questions is implicit

in a finding under subdivision (b). . . .

3B Moore's Federal Practice f 23.06-1, p. 23-171; see

also Wright and Miller, 7 Federal Practice and Procedure

§ 1763, p. 609. Moreover, Rule 23(a) (2)

does not require that all questions of law and fact

raised by the dispute be common; nor does it estab

lish any quantitative or qualitative test of common

ality. All that can be devined from the rule itself

is that the use of the plural “questions” suggests that

more than one issue of law or fact must be common

to members of the class.

Id., § 1763, pp. 603-04 (footnote omitted). See Norwalk

CORE v. Norwalk Redevelopment Agency, 395 F.2d 920,

937 (2d Cir. 1968).

Similarly, the “typicality” requirement of Rule

23(a) (3) does not lead to any inflexible standards. “As

one court conservatively stated, there ‘may be some doubt

as to the precise meaning of the clause.’ ” 3B Moore’s

Federal Practice If 23.06-2, p. 23-185; see Wright and

Miller, 7 Federal Practice and Procedure § 1764, p. 611.

It appears that the typicality requirement was “designed

to buttress the fair representation requirement in Rule

discrimination on the basis of class characteristics.” Memorandum

for the United States and Equal Employment Opportunity Commis

sion as Amici Curiae, East Texas Motor Freight V. Rodriguez, Nos.

75-651, 75-715, 75-718.

22

23(a) (4),” id., p. 612, quoting Rosado V. Wyman, 322

F.Supp. 1173, 1193 (E.D.N.Y.) (Weinstein, J.), aff’d

on other grounds, 437 F.2d 619 (2d Cir.), rev’d on other

grounds, 397 U.S. 397 (1970).

The requirements of Rule 23(a) should be applied in a

manner consistent with the overall purposes of Rule 23:

(a) to provide a mechanism for the efficient resolution

of many individual claims in a single action; (b) to

eliminate repetitious litigation and possibly inconsistent

adjudication involving common questions, related events,

or requests for similar relief; and (c) to establish an

effective procedure for persons who would be unable to

vindicate their rights in separate lawsuits because of the

cost.28 In addition, Rule 23 must be implemented in a

manner consistent with due process, Hansberry v. Lee,

311 U.S. 32 (1940), and with the substantive law upon

which the action is based. See section II,A,2, supra. To

apply the commonality and typicality requirements in the

restrictive and inflexible manner urged by General Tele

phone would establish barriers to class litigation which

would undermine the basic purposes of Rule 23 and

would frustrate the intent of Congress.

Moreover, “ [cjommon questions of law or fact are

typically present” in employment discrimination cases

because such suits “are often by their very nature class

suits, involving classwide wrongs.” East Texas Motor

Freight V. Rodriguez, 431 U.S. at 405. As this court has

emphasized, proof of discriminatory intent must “often

be inferred from the totality of relevant facts . . . .”

Washington v. Davis, 426 U.S. 229, 242 (1976) ; see

Arlington Heights V. Metropolitan Housing Development

Corp., 429 U.S. 252, 266-68 (1977). Thus, contrary to

the assertion of General Telephone, Brief, p. 32, a plain

tiff claiming discriminatory treatment has a direct self-

interest in demonstrating that other persons were simi

larly victimized and that other practices were affected by * 39

26 Deposit Guaranty National Bank V. Roper, 445 U.S. 326, 338-

39 (1980).

23

discriminatory motive. See Keyes v. School District No. 1,

413 U.S. 189, 208 (1973) ; Columbus Board of Education

V. Penick, 443 U.S. 449, 458 n.7 (1979). Even in an

individual Title VII case, the plaintiff may rely upon

proof of “a general pattern of discrimination.” McDon

nell Douglas Corp. v. Green, 411 U.S. at 805; Davis v.

Califano, 613 F.2d 957, 960-66 (D.C. Cir. 1979).

General Telephone is also wrong in asserting that a

plaintiff whose claim depends upon proof of discriminatory

treatment may not represent class members whose claims

depend upon proof of adverse impact. First, the relevant

proof in effect and intent cases is often quite similar.

The plaintiff may establish a prima facie case of dis

parate impact or disparate treatment through the use of

statistical evidence. See Teamsters V. United States, 431

U.S. at 339 n.20. Second, the employer’s rebuttal evi

dence may be the same in an intent case as in an effect

case. While the good faith of an employer may present

a total defense in a discriminatory treatment case, evi

dence of good faith in a discriminatory impact case may

“open[] the door to [an] equit[able]” defense. Albe

marle Paper Co. v. Moody, 422 U.S. at 422. Indeed, the

court’s determination of whether to apply an Intent stand

ard or an effect standard may well depend more upon the

nature of the defense than upon the nature of the plain

tiff’s claim.27 In attempting to establish a prima facie

27 For example, if plaintiff shows that a company’s promotional

selection procedure has a significant adverse impact on black em

ployees, the company may present evidence either that the selections

were made pursuant to objective criteria or that its supervisors

exercised their subjective discretion in a fair and non-discriminatory

manner. There is a fine line between evidence regarding fair imple

mentation of a subjective standard and the implementation of objec

tive criteria. The court may well have to analyze employment prac

tices under both intent and effect standards. See James v. Stock-

ham Valves & Fittings, Inc., 559 F.2d 310 (5th Cir. 1977), cert,

denied, 434 U.S. 1034 (1978); Rivera V. City of Wichita Falls, 665

F.2d 531, 535 n.5 (5th Cir. 1982) ; Royal V. Missouri Highway and

Transportation Comm., 655 F.2d 159 (8th Cir. 1981) ; Clark V.

Alexander, 489 F.Supp. 1236 (D.D.C. 1980).

24

ease, the plaintiff often does not know whether the case

ultimately will turn on an intent analysis or an effect

analysis.®8 Thus, the prudent plaintiff may present evi

dence establishing a violation under both standards.

Third, where the plaintiff presents a prima facie discrim

inatory impact case which the defendant rebuts by show

ing that the criteria causing the impact are job related,

the plaintiff may prevail by showing that the criteria are

“merely [used] as a ‘pretext’ for discrimination.” Albe

marle Paper Co. V. Moody, 422 U.S. at 425, citing

McDonnell Douglas Corp. V. Green, 411 U.S. at 804-05.

“Pretext” can be demonstrated by proof of intentional

discrimination. Finally, questions of remedy—e.g., the

availability of back pay and retroactive seniority, and

the appropriate scope of affirmative action—generally are

the same regardless of the underlying theory of liability.

See Albemarle Paper Co. V. Moody, 422 U.S. at 418-21;

Franks V. Bowman Transportation Co., 424 U.S. at 770-

80; Teamsters V. United States, 431 U.S. at 363-76.

2. The “Adequacy of Representation” Requirement.

The adequacy requirement of Rule 23(a) (4) insures

that the absent class members will not be deprived of due

process and that they will accordingly be bound by the

final judgment. The adequacy issue must be examined

in the context of each case. East Texas Motor Freight v.

Rodriguez, 431 U.S. at 405-06. 28

28 This uncertainty is compounded by changing standards of fair

employment law. See, e.g., Teamsters V. United States, supra (plain

tiff, following more than 30 decisions of six courts of appeals,

litigated the case under an effect standard only to lose because of a

failure to prove intent) ; Washington v. Davis, supra (plaintiff

prevailed on an impact theory in the court of appeals but lost in

this Court because of a failure to prove intent). In this term the

Court has granted petitions for certiorari in two cases which raise

the question whether a violation of 42 U.S.C. § 1981 requires proof

of intent. General Building Contractors Ass’n V. Pennsylvania,

supra-, Guardinas Ass’n V. Civil Service Commission of the City of

New York, supra.

25

General Telephone urges this Court to adopt a per se

rule: Regardless of the particular facts of a case, an

employee may not represent a class including applicants

where there is a potential for conflict over future promo

tional opportunities,29 30 As the Justice Department cor

rectly points out, such an inflexible rule would virtually

eliminate class litigation under Title VII. Brief, p.19,

n.17. Moreover, General Telephone’s position ignores the

interest of black and Hispanic employees in securing a

discrimination-free work environment, including their in

terest in eliminating discrimination against black and

Hispanic applicants for employment. See section IRA,

supra.m

Furthermore, the courts are “aware of the irony that

a dismissal for inadequacy of representation may as a

practical matter . . . result in no representation at all of

the class interest.” 3B Moore’s Federal Practice If 28.07

[2], p. 23-221. It is in the interest of General Telephone

and other employers, but not in the interest of the victims

of unlawful practices, to limit the scope of class repre

sentation by establishing rigid per se rules restricting the

application of Rule 23(a) (4). The adoption of such arti

29 Scott v. University of Delaware, 601 F.2d 76 (3d Cir.), cert,

denied, 444 U.S. 931 (1979), cited by General Telephone, is inap

posite. In Scott, the plaintiff took inconsistent positions with respect

to his claim and the claims of the applicant class which he sought

to represent. It is the “assertion of these inconsistent positions

[which] necessarily forecloses any contention that [the plaintiff’s]

claims are typical . . . [or that he is] an adequate representative

of the unnamed members of the class seeking employment.” 601

F.2d at 86 (footnote omitted).

30 General Telephone appears to assume that blacks and Hispanics

will act like proverbial crabs in a barrel, pulling each other down in

order to advance themselves. Is it not more reasonable to assume

that minority employees would be motivated to remove all discrimi

natory practices, and to eliminate the threat of harm to and the

implicit badge of inferiority on all minorities? If a company dis

criminates in its hiring policies, is it not reasonable for a minority

employee to think that the discriminatory treatment might extend

to the company’s promotional policies as well ?

26

ficial and inflexible rules would result in the denial of

relief to victims of unlawful discrimination.31

The rigid rules proposed by General Telephone for the

application of Rule 23(a) would frustrate the purposes

of both Rule 23 and Title VII. Contrary to General Tele

phone’s assertions, nothing in East Texas Motor Freight

V. Rodriguez,32 33 General Telephone v. EEOC,ss or any

31 For example, persons who did not apply for jobs due to an

employer’s discriminatory practices may be entitled to relief under

Title VII. Teamsters V. United States, 431 U.S. at 367. Rejected

applicants are permitted to represent classes including persons who

were deterred from applying; “if this were not the case, most such

persons would go without relief entirely, since it is unlikely that

one of them would sue and qualify as a class representative.”

Phillips v. Joint Legislative Committee, 637 F.2d 1014, 1024 (5th

Cir. 1981). See also Justice Department Brief, p. 2. Under General

Telephone’s theory, such classes would be prohibited since there

might be potential competition between the representative and the

class for a limited number of job openings. General Telephone’s

rule would have the same result as a “per se prohibition of relief to

nonapplicants [which] could thus put beyond the reach of equity

the most invidious effects of employment discrimination. . . .”

Teamsters v. United States, 431 U.S. at 367.

32 In Rodriguez the Court held that, where the named plaintiffs’

claims had been resolved against them on the merits prior to a

decision on class certification, they were not “members of the class

they purported to represent” and therefore could not maintain a

class action. 431 U.S. at 403-04. See Rule 23(a), Fed. R. Civ. P.

(“[o]ne or more members of a class may sue or be sued as repre

sentative parties” if the numerousity, commonality, typicality and

adequacy requirements are satisfied) (emphasis added). Addition

ally, the Court held that the plaintiffs in Rodriguez did not satisfy

the adequacy requirement of Rule 23(a)(4) because they failed to

move for class certification, and because their interests directly con

flicted with the interests of the proposed class members, who had

voted by a large majority to reject the relief the plaintiffs were

seeking. 431 U.S. at 404-05. In the present case, by contrast, plain

tiff Falcon was at all times a member of his class, he moved for

and obtained certification before trial, and there is no indication of

any actual conflict of interest.

33 In General Telephone v. EEOC, the Court held that the Equal

Employment Opportunity Commission may maintain civil actions

27

other decision of this Court supports the imposition of

such artificial and inflexible rules. The lower courts thus

should be permitted to continue to use their sound discre

tion in applying Rule 23 to the cases before them.

C. The District Court and the Fifth Circuit Correctly

Applied Rule 23 in this Case.

General Telephone has made no “obvious and excep

tional showing of error” by either of the courts below.

Berenyi v. Immigration and Naturalization Service, 385

U.S. 630, 635 (1967).34 To the contrary, the record in

this case fully supports both the district court’s class

certification and the Fifth Circuit’s affirmance of that

certification.

General Telephone asserts that “there was no evi

dence . . . that the same individuals were responsible for

seeking relief for the victims of unlawful employment practices with

out complying with Rule 23. 446 U.S. at 333-34. In distinguishing

EEOC actions from private class actions, the Court noted that the

typicality requirement of Rule 23(a)(3) “is said to limit the class

claims to those fairly encompassed by the named plaintiff’s claims,”

and that under the adequacy requirement of Rule 23(a)(4), “con

flicts might arise, for example, between employees and applicants

who ware denied employment and who will, if granted relief, com

pete with employees for fringe benefits or seniority.” 446 U.S. at

330-331. Thus, while Rules 23(a) (3) and (a) (4) may well preclude

a black male plaintiff, for example, from representing a class con

taining white females complaining of sex discrimination, the EEOC

may properly bring a Title VII enforcement action on behalf of