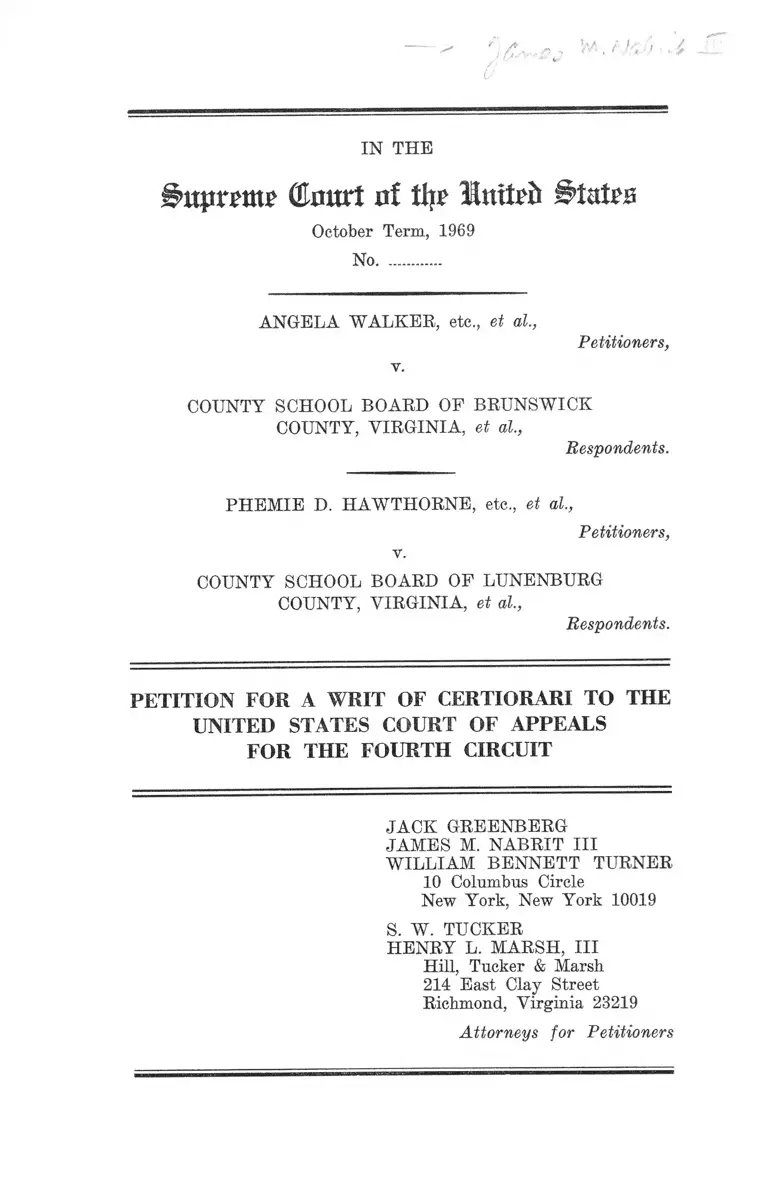

Walker v. Brunswick County School Board, Virginia Petition for Writ of Certiorari

Public Court Documents

December 9, 1968

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Walker v. Brunswick County School Board, Virginia Petition for Writ of Certiorari, 1968. 182fe72e-c89a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/39e65640-fb9c-443c-b22f-6ae0a6e01254/walker-v-brunswick-county-school-board-virginia-petition-for-writ-of-certiorari. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

IN THE

#itpnmtp (Efliut of tip? lottos Status

October Term, 1969

No..............

ANGELA WALKER, etc., et al.,

v.

Petitioners,

COUNTY SCHOOL BOARD OF BRUNSWICK

COUNTY, VIRGINIA, et al.,

Respondents.

PHEMIE D. HAWTHORNE, etc., et al.,

Petitioners,

v.

COUNTY SCHOOL BOARD OF LUNENBURG

COUNTY, VIRGINIA, et al.,

Respondents.

PETITION FOR A WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE FOURTH CIRCUIT

JACK GREENBERG

JAMES M. NABRIT III

W ILLIAM BENNETT TURNER

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

S. W. TUCKER

HENRY L. MARSH, III

Hill, Tucker & Marsh

214 East Clay Street

Richmond, Virginia 23219

Attorneys for Petitioners

I N D E X

PAGE

Table of Authorities ............................. ...... -.................. ii

Citations to Opinions Below .......................................... 2

Jurisdiction ......................................-....... ..................... — 2

Question Presented ........................................................ - 2

Rule and Constitutional Provision Involved -............... 3

Statement .............. —......................................................... 3

A. Walker v. County School Board of Brunswick

County, Virginia ...................................... -........ 3

B. Hawthorne v. County School Board of Lunen

burg County, Virginia........................................ 5

R easons F or Gran tin g th e W rit ................................. 7

I. Introduction: Importance of the Issue.... ........ 7

II. Fees and Costs Should have been Awarded in

these Cases under Rule 38 ..................... ........... 8

III. Counsel Fees Should have been Awarded in the

Equitable Discretion of the Court of Appeals.... 11

C onclusion ................................ ...................................... 12

A ppendix

Opinion of Court of Appeals........ ..... .................... la

Decision of District Court ........ .................. ........... 3a,

11

T able of A uthorities

Cases: p a g e

Alexander v. Holmes County Board of Education, No.

632 (October 29, 1969) ................................................ 7

Bell v. School Board of Powhatan County, Virginia,

321 F.2d 494 (4th Cir. 1963) ................................... . 10

Brown v. Board of Education, 347 U.S. 483 (1954) .....2, 3n

Brown v. Board of Education, 349 U.S. 294 (1955)....3n, 8,

9,10,11,12

Clark v. Board of Education of Little Rock School Dis

trict, 369 F.2d 661 (8th Cir. 1966) ......... .................. 11

Cooper v. Aaron, 358 U.S. 1 ............................................. 9

Coppedge v. Franklin County Board of Education, 394

F.2d 410 (4th Cir. 1968) .............................................. 10

Felder v. Harnett County Board of Education, 409 F.2d

1070 (4th Cir. 1969) ............ ................................5, 6, 9,10

Griffin v. School Board, 277 U.S. 218......... ................... 9

Lee v. Macon County Board of Education, No. 604-E

(M.D. Ala. August 28, 1968) ........................ ............. 9

Monroe v. Board of Commissioners of the City of

Jackson, Tennessee, 391 U.S. 450 (1968) .............. 4, 5, 6, 8

Newman v. Piggie Park Enterprises, Inc., 390 U.S. 400

(1968) ....................... ......................... .................... .....11,12

Vaughn v. Atkinson, 366 U.S. 567 (1962) ...................... 11

Wallace v. United States, 389 U.S. 215 .......................... 9

Ill

Statutes and Rules:

PAGE

28 U.S.C. § 1254 (1) ....

28 U.S.C. § 1912...........

Fed. R. App. P. Rule 38

2

lln

3, 7, 9,12

Other Authorities:

Advisory Committee’s Note, 43 F.R.D. 61,155 (1968) ..9, lln

United States Civil Rights Commission, Federal En

forcement of School Desegregation (September 11,

1969) ...................................-.......................................... 10

In the

Supreme ©curt of % Intfrfc BttxUB

October Term, 1969

No..... .......

A ngela W alk er , etc., et al.,

v.

Petitioners,

C ou nty S chool B oard of B ru n sw ic k C o u n ty ,

V irgin ia , et al.,

Respondents.

P h e m ie D . H aw th orn e , etc., et al.,

Petitioners,

v.

Co u n ty S chool B oard of L unenburg C o u n ty ,

V irgin ia , et al.,

Respondents.

PETITION FOR A WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE FOURTH CIRCUIT

Petitioners pray that a writ of certiorari issue to review

the judgments of the United States Court of Appeals for

the Fourth Circuit entered in these two cases on July 11,

1969.

2

Citation to Opinions Below

The opinion of the United States Court of Appeals for

the Fourth Circuit, covering both cases, is reported at 413

F.2d 53 and is set forth in the Appendix, infra, p. la. The

orders of the United States District Court for the Eastern

District of Virginia are not reported. The District Court

order, findings of fact and conclusions of law in the Walker

case are set forth in the Appendix, infra, at pp. 4a-9a and

in the record at pp. 139-142, 146 (Volume I). The District

Court order, findings of fact and conclusions of law in the

Hawthorne case are set forth in the Appendix, infra, at pp.

10a-15a and in the record at pp. 59-64 (Volume II).

Jurisdiction

The judgments of the United States Court of Appeals

for the Fourth Circuit were entered on July 11, 1969. The

time for filing a petition for writ of certiorari was extended

to and including November 9, 1969, by order of Chief Jus

tice Warren E. Burger, dated October 1, 1969. Jurisdiction

of this Court is invoked pursuant to 28 U.S.C. § 1254(1).

Question Presented

Whether counsel fees and double costs on appeal should

be awarded Negro plaintiffs in these school desegregation

cases where respondent school boards, still maintaining

their segregated school systems 15 years after Brown v.

Board of Education, prosecuted appeals from integration

orders in the face of binding precedent foreclosing their

contention that to desegregate would cause white students

to flee the system.

3

Rule and Constitutional Provision Involved

This case involves Rule 38 of the Federal Rules of Appel

late Procedure, which provides as follows:

If a court of appeals shall determine that an appeal

is frivolous, it may award just damages and single or

double costs to the appellee.

This case also involves Section I of the Fourteenth

Amendment to the Constitution of the United States.

Statement

A. Walker v. County School Board of

Brunswick County, Virginia

This school desegregation case was filed on March 17,

1965 as a class action on behalf of the Negro students in

Brunswick County, Virginia. Until that time, the County

School Board had simply ignored the Brown decision1 2 and

the Court’s direction in Brown IP that the transition to a

non-raeial system be effected with all deliberate speed.

After the filing of this suit and until the current school

year, the School Board operated a “freedom of choice”

desegregation plan. In the school year 1968-69, the School

Board maintained 9 schools (infra, p. 4a). Of this number,

2 were all-white and 5 were all-black. Only about 100 of the

2,900 Negro students attended formerly white schools; thus,

more than 96.5% of the Negro students were in all-black

schools. No white student chose to attend a formerly all-

black school. Also, as the district, court found, “ faculty

desegregation is practically nil” (infra, id. 5a).

1 Brown v. Board of Education, 347 U.S. 483 (1954).

2 Brown v. Board of Education, 349 U.S. 294 (1955).

4

The district court found that the freedom of choice plan

was not adequate to bring about the conversion to a unitary-

school system. The court said that “it might well be twenty

to thirty years under the existing plan before the result

required by the law would come about” (infra, p. 6a).

The School Board’s sole contention in the district court

was that any plan which actually dismantled the racially

dual school system would result in a flight of white students

from the school system. The district court, however, found

that “I don’t believe it is going to happen” (infra, p. 5a),

and held that, in any event, this possibility was ruled out

as a defense by this Court’s decision in Monroe v. Board of

Commissioners of the City of Jackson, Tennessee, 391 U.S.

450, 459 (1968).

At the conclusion of the hearing held on November 8,

1968, the court directed the School Board to file a plan other

than freedom of choice. On December 6, 1968, the School

Board filed a report showing that by pairing schools in the

County, a unitary school system would result. But the

Board refused to submit such a plan on the ground that it

could agree only to freedom of choice. On December 9,

1968, the district court ordered the School Board to develop

a plan other than freedom of choice to disestablish the dual

system (infra, p. 8a). The School Board appealed to the

Fourth Circuit from this order.

On appeal, again the School Board’s sole contention was

that only freedom of choice would work and that any plan

which actually integrated the schools would result in the

flight of white students from the school system. Petitioners

moved in the Court of Appeals for summary affirmance and

for an award of counsel fees and double costs pursuant to

5

Fed. E. App. P. Rule 38.3 The appeal was argued on June

9, 1969. On July 11, 1969, the Court of Appeals affirmed

the judgment of the district court, holding that this Court’s

decision in Monroe, supra, foreclosed the School Board’s

sole contention {infra, p. 3a). However, the Court of Ap

peals denied petitioners’ motion for double costs and coun

sel fees, without giving any reasons, citing its earlier deci

sion in Felder v. Harnett County Board of Education, 409

F.2d 1070 (4th Cir. 1969). The Felder case held that fees on

appeal were not available in school cases unless the board

had engaged in an “extreme” pattern of evasion or its

appeal had been mooted by compliance. 409 F.2d at 1075.

B. Hawthorne v. County School Board of

Lunenburg County, Virginia

This case was filed on August 28, 1968. As in the Walker

case, the School Board was then maintaining a substantially

segregated system. In 1965-66, the Board began operating

a “ freedom of choice” plan. Three years later, the Board

was still maintaining 3 all-black schools and only 140 of

the 1,567 Negro students in the system were attending for

merly all-white schools (thus, more than 91% were in the

all-black schools) {infra, pp. lla-12a). Not a single white

student chose to attend a school formerly reserved for black

students. The district court also found that the Board

operated a segregated bus system and assigned teachers in

a racially discriminatory manner.

As in Walker, the district court ruled out freedom of

choice, stating that there was not a “ scintilla of evidence”

to indicate that the free choice plan would disestablish the

3 Petitioners are represented by private counsel in Richmond,

Virginia, associated with salaried attorneys of the NAACP Legal

Defense and Educational Fund, Inc., a non-profit civil rights

organization dedicated to the vindication by legal means of the

rights of our Nation’s black citizens.

6

dual system in the reasonably near future (infra, p. 14a).

The court overruled the “white flight” defense on the au

thority of Monroe, supra, and directed the School Board

to file a new plan within 30 days. The Board filed a plan

on January 29, 1969, two days after it filed notice of appeal.

On appeal, again the Board’s sole contention was that

only freedom of choice would work and that any plan

which actually dismantled the dual system would result in

the flight of white students. As in Walker, petitioners

moved for summary affirmance and for counsel fees and

double costs. The appeal was argued and decided with

Walker. The Court of Appeals affirmed on the authority

of Monroe but denied the motion for fees and double costs,

without giving any reasons, citing its decision in Felder,

supra.

7

REASONS FOR GRANTING THE WRIT

I.

Introduction: Importance of the Issue

This Court’s recent decision in Alexander v. Holmes

County Board of Education, No. 632 (October 29, 1969),

demonstrates that ’procedure is crucial to the actual reali

zation of the rights of Negro school children to an inte

grated education. Alexander establishes that judicial and

administrative delay can no longer be used to put off the

time for converting to unitary school systems. Even though

such delay is thus ruled out, there remains the certainty

that some school boards will continue to litigate whether

their desegregation plans constitute substantive compliance

with Brown. That is, they will continue to burden the al

ready overloaded federal courts with litigation seeking ap

proval of weak and inadequate plans for achieving “unitary”

systems. School boards will continue to appeal from decrees

which reject such plans. The instant cases are typical.

Yet the Federal Rules of Appellate Procedure do con

template a procedure to deter those who by litigation seek

to defeat rights which have been clearly defined. Rule 38

provides for the award of counsel fees and double costs in

frivolous appeals. Petitioners submit that such awards

are an essential element of procedure in enforcing the

constitutional right to an integrated education. Petitioners’

interest is in assuring effective and expeditious desegrega

tion of the public schools, and they believe that counsel fee

awards should be made in furtherance of this purpose.

This Court has never dealt with the standards for grant

ing counsel fees on appeal under Fed. R. App. P. Rule 38.

Nor has the Court dealt in particular with the question

whether counsel fees on appeal should be granted in school

8

desegregation cases where school boards elect to litigate

rather than integrate. Although the Court has repeatedly

been called upon to consider the substantive meaning of

Brown, it has never considered the effect of counsel fee

awards as a means of enforcing Brown. Consequently, the

Courts of Appeals have been left to fashion their own

standards, and the result is that counsel fees are almost

never awarded and school boards continue to use litigation

to put off compliance with their plainest obligations.

We submit that counsel fees and double costs should have

been awarded by the Fourth Circuit in these cases. We fur

ther submit that the standards applied by the court below

are wholly inappropriate for school desegregation cases at

this stage of the desegregation process. Fees and costs

should be awarded as a matter of course where a school

board appeals an integration order, unless the board in good

faith raises a truly novel issue on appeal.

II.

Fees and Costs Should Have Been Awarded in These

Cases Under Rule 38.

In these cases, the school boards’ only defense in the

district court was that white students would likely flee a

unitary school system. This contention had been foreclosed

by this Court, however, in Monroe v. Board of Commis

sioners, 391 U.S. 450, 459 (1968):

“We are frankly told in the Brief that without the trans

fer option it is apprehended that white students will

flee the school system altogether. ‘But it should go

without saying that the vitality of these constitutional

principles cannot be allowed to yield simply because of

disagreement with them.’ Brown II, at 300.”

9

Indeed, the white resistance argument has been rejected

over and over by the courts:

“ . . . the courts and the school boards, in carrying out

their constitutional duties of desegregating the public

school systems that are based on race, cannot yield in

the exercise of that duty because of the possibility that

white students will flee the public school system or that

the public will discontinue its financial support of its

public school system. See Cooper v. Aaron, 358 U.S. 1,

Griffin v. School Board, 211 U.S. 218, Wallace v. United

States, 389 U.S. 215.” Lee v. Macon County Board of

Education, No. 604-E (M.D. Ala. August 28, 1968).

In other words, the school boards’ argument in the trial

court and on appeal was not only old and tired; it had been

rightly perceived by the courts not to be an argument in

favor of “freedom of choice” as a desegregation plan but as

an impermissible plea for continued segregation.4 In these

circumstances, one would have supposed these cases to be

the model “ frivolous” appeal contemplated by Rule 38 of

the Federal Rules of Appellate Procedure. As the Advisory

Committee on the Rules has noted, courts of appeals may

grant counsel fees and double costs on a frivolous appeal

without any showing that the appeal has resulted in a delay

in enforcing the appellee’s rights. 43 F.R.D. 61, 155 (1968).

Yet the court below, without giving any reasons, denied

petitioners’ prayer for counsel fees on appeal. The court

relied on its earlier decision in Felder v. Harnett County

Board of Education, 409 F.2d 1070 (4th Cir. 1969), where

the court mentioned (409 F.2d at 1075) two situations in

which counsel fees could be awarded:

4 The appeal of the Brunswick County School Board was espe

cially frivolous because of the trial court’s finding of fact that the

board’s “white flight” prediction was not entitled to credence.

See infra, p. 5a.

10

(1) where the school board has engaged in an “ex

treme” pattern of evasion and obstruction. Bell v.

School Board of Powhatan County, Virginia, 321 F.2d

494 (4th Cir. 1963); and

(2) where the issues on appeal have been mooted by

compliance. Coppedge v. Franklin County Board of

Education, 394 F.2d 410 (4th Cir. 1968).

But, we submit, these situations are not appropriate stan

dards for awarding fees in school cases 15 years after

Brown. Rather, we believe with Judge Sobeloff, dissenting

in Felder, that a counsel fee award

“would not only transfer the burdensome cost of the

litigation from those who have been and continue to be

deprived of their constitutional rights to those re

sponsible for the deprivation, but it would also provide

a suitable and necessary incentive to the school authori

ties to get on with the task of desegregating.” 409 F.2d

at 1075-6.

In short, these are not ordinary cases involving stubborn

litigants; these cases are part of a pattern of resistance to

integration, where the law and facts are perfectly clear but

the school boards will not voluntarily take even the obvious

step without litigating each point that might somehow be

productive of further delay. See generally, United States

Civil Rights Commission, Federal Enforcement of School

Desegregation, 12, 28 (September 11, 1969). In these cir

cumstances, Rule 38 should not be given the restrictive in

terpretation of the court below. Rather, it should be pre

sumed that fees on appeal are available to appellee Negro

schoolchildren unless the school board raises a genuine

issue. In other words, relitigating the issue of compliance

with the school board’s affirmative obligation to integrate

11

the schools should be considered prima facie frivolous with

in the meaning of Eule 38.

III.

Counsel Fees Should Have Been Awarded in the

Equitable Discretion of the Court of Appeals.®

The federal courts have equitable power to award coun

sel fees even in the absence of explicit statutory authoriza

tion. See Vaughn v. Atkinson, 366 U.S. 567 (1962); Newman

v. Piggie Park Enterprises, Inc., 390 U.S. 400, 402, n.4

(1968). The typical case is where the court labels a litigant’s

position “vexatious” or in “bad faith” or taken for the pur

pose of delay.6 Id. We submit that 15 years after Brown

appeals by school boards resisting their plainest constitu

tional obligations are per se vexatious, unless a new and

unusual issue is raised. Negro school children should not

have to bear the “constant and crushing expense of enforc

ing their constitutionally accorded rights,” Clark v. Board

of Education of Little Rock School District, 369 F.2d 661,

671 (8th Cir. 1966), and the expense of litigating appeals

from integration orders should be imposed on the party

causing the expense—the recalcitrant school board. More

over, where, as here, a class action is brought seeking finally

to end racially segregated education, the proceeding is pri

B Counsel for petitioners also represent the petitioners in Wil

liams v. Kimbrough, from the Court of Appeals for the Fifth

Circuit, and we are filing a petition for certiorari in that case

simultaneously herewith. In Williams, the petitioners urge that

counsel fees should have been granted by the district court, as a

matter of complete equitable relief.

_ 6 Courts of appeals also have “discretion” under 28 U.S.C. Sec

tion 1912 to award an appellee “just damages for his delay.” The

“ damages” may include attorneys’ fees and other expenses in

curred by the appellee. See Advisory Committee’s Note, 43 F E D

61, 155 (1968).

12

vate in form only—petitioners act as “private attorneys

general” in vindicating the rights of the class and further

ing the public policy of the nation. Cf. Newman v. Piggie

Park Enterprises, Inc., swpra, at 402. Just as in Piggie

Park counsel fee awards were seen as essential in enforc

ing substantive rights under the Civil Rights Act of 1964,

here such awards have now become crucial in bringing a

halt to school litigation and a beginning to the integration

promised by Brown. Thus, counsel fee awards should be

made so that the “private attorney general” will not be

penalized for performing the public function of eradicating

unconstitutional discrimination in the schools.

CONCLUSION

We submit that counsel fee awards can be an effective

tool in enforcing Brown and in making it plain to recalci

trant school boards that integration decisions mean what

they say. We ask that the Court grant certiorari to deter

mine the standards for granting counsel fees in school cases

under Rule 38 and in the equitable power of the federal

courts.

Respectfully submitted,

J ack G reenberg

J am es M. N abrit III

W illiam B en n ett T urner

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

S. W. T ucker

H en ry L. M a r sh , III

Hill, Tucker & Marsh

214 East Clay Street

Richmond, Virginia 23219

Attorneys for Petitioners

APPENDIX

Opinion o f the Court of Appeals for the Fourth Circuit

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

F ob th e F ourth C ircu it

No. 13,283

A ngela "Walker , etc., et al.,

versus

Appellees,

C o u n ty S chool B oard oe B r u n sw ic k C o u n ty ,

V irgin ia , et al.,

Appellants.

No. 13,284

P h e m ie D. H aw th o r n e , etc., et al.,

Appellees,

versus

C o u nty S chool B oard oe L unenburg Co u n t y ,

V irgin ia , et al.,

Appellants.

Appeals from the United States District Court for the

Eastern District of Virginia, Richmond Division.

R obert R. M erh ige , J r ., District Judge.

Argued June 9, 1969 Decided July 11, 1969

Before S obeloee, B oreman and Craven , Circuit Judges.

2a

Emerson D. Baugh and Frederick T. Gray (Williams,

Mullen & Christian; and Samuel N. Allen on brief) for

Appellants and Henry L. Marsh, III (S. W. Tucker; Hill,

Tucker & Marsh; Jack Greenberg and James M. Nabrit,

III, on brief) for Appellees.

Opinion of the Court of Appeals for the Fourth Circuit

P er Cu riam :

We noted the similarity of the issues presented and

consolidated these separate appeals for purposes of oral

argument and disposition.

These cases present the hard practical problem con

fronting school boards in systems where Negro students

are in a substantial majority.1 Relatively little integration

has occurred under the freedom of choice method of opera

tion of these schools and the plans of operation may fairly

be described as dual systems. Since Green v. County

School Board of New Kent County, 391 U.S. 430 (1968),

reversing 382 F.2d 338 (4th Cir. 1967), freedom of choice

may not be held an adequate compliance with a school

board’s duty to devise a non-racial system unless it “prom

ises realistically to work, and promises realistically to

work now.” 391 H.S. at 439. It is not seriously urged

upon us—indeed, it could not be—that freedom of choice

has worked or is likely to work in the foreseeable future

in the sense meant by the Supreme Court in Green: the

disestablishment of former state imposed segregation and

its replacement with an entirely desegregated system.2 3

1 In Lunenburg County 1567 pupils are Negro and 1385 are

white; in Brunswieh County 71% of students are Negro and 29%

white.

3 The famous Briggs v. Elliott dictum— adhered to by this court

for many years—-that the Constitution forbids segregation but

3a

Instead, the school boards urge upon, us that freedom

of choice will work better than any more drastic method

because if general racial mixing is forced in a school

population heavily Negro the white minority will flee the

school system. It is urged that it is better to have some

racial mixing in a freedom of choice system than to have

an all Negro system abandoned by white pupils.

Whatever the appeal of such an argument the Supreme

Court has foreclosed our consideration of it—at least in

the context of a theoretical possibility.3 In Monroe v.

Board of Commissions, 391 U.S. 450, 459, the Court re

jected the same contention made in the context of defend

ing a free transfer provision:

“We are frankly told in the Brief that without the

transfer option it is apprehended that white students

will flee the school system altogether. ‘But it should

go without saying that the vitality of these constitu

tional principles cannot be allowed to yield simply be

cause of disagreement with them.’ Brown II, at 300.”

Motion of appellees to award double costs and counsel

fees is denied. See, Felder v. Harnett County Board of

Education, ------ F.2d ------ (4th Cir. No. 12,894, Apr. 22,

1969).

The judgments of the district court will be

A ffirm ed. * 3

Opinion of the Court of Appeals for the Fourth Circuit

does not require integration, (132 F.Supp. 776 (E.D.S.C. 1955)

is now dead. Green v. County School Board of New Kent County,

391 U.S. 430 (1968); Monroe v. Board of Commissioners of the

City of Jackson, 391 U.S. 450 (1968); cf. United States v. Jeffer

son County Board of Education, 380 F.2d 385 (5th Cir. 1967)

(Griffin B. Bell and Gewin, dissenting).

3 The record does not indicate that there has been, as yet, any

fleeing of the school systems. With respect to Brunswick County

the district judge expressed the opinion it would not occur.

4a

Findings of Fact and Conclusions of Law

From the Bench

(Walker v. County School Board of Brunswick County)

November 8, 1968 — 10 :00 a.m.

The Court: All right, I would ask the members of the

School Board to remain so that there is no misunderstand

ing as to whatever ruling the Court may make.

Suffice it to say, I think I had best dictate into the record

my findings of fact and conclusions of law, gentlemen.

Plaintiff’s motion for further relief is granted. This

Court has no doubt whatsoever from the evidence before

the Court that the mandate, or the requirements of the

New Kent case have not been met. This Court has no

doubt but that the freedom of choice plan now in existence

and heretofore approved by this Court has failed to ac

complish that which everybody, I am satisfied, was hopeful

it would accomplish at the time it was put into effect, and

therefore as of the end of the school year, is no longer

acceptable to the Court.

The Court finds from the evidence before the Court and

the interrogatories, that Brunswick County consists of the

following schools: Elementary schools—Alberta, with a

capacity of 240 to 256 students, presently has 202 white

students and no Negro; Red Oak Elementary School, with

a capacity of approximately 480 students, now has an

enrollment of approximately 410, all Negro students;

Lawrenceville Primary School, or Elementary School,

which has a capacity of approximately 500 students, now

has an enrollment of approximately 359, of whom 335 are

White and 24 are Negro; Sturgeon, with a capacity of ap

proximately 480, has 402 presently enrolled, all Negro;

South Brunswick with a capacity of 250 to 275 students,

presently has an enrollment of 186, all white; Meherrin-

Powellton, with a capacity of approximately 660 students,

has an enrollment of approximately 498, all Negro; and

oa

Totoro, with a capacity of approximately 480 students,

presently has an enrollment of approximately 470, all

Negro.

There are two high schools. One is Brunswick, with a

capacity of 600 students, the present enrollment consisting

of approximately 493 white students and 75 Negro stu

dents; and the J. S. Russell High School, with a capacity

of 1100 to 1150 students; presently has an enrollment of

approximately 1039, all Negro students. Not one white

student has asked for assignment to a school predominantly

Negro, and approximately 100 out of 2900 Negro students

are now attending white schools.

The Court finds that there has been no direct order by the

Board of the School Board to the Superintendent to bring

in a plan which would result in a dismantling of the school

systems to the end that racial identity would be done away

with, but on the contra the Court finds from the School

Board and responsible citizens of the county, that the

Board came to the conclusion that any plan other than the

plan that is now in effect would result in a fleeing from the

school system of the white students. That is the evidence

before the Court.

The Court is satisfied that the people who have testified

are sincere in that belief, but I don’t believe it is going to

happen and must say that under the law, the law cannot

yield simply because of the fact that they might do that.

See Brenda K. Monroe, et al v. Board of Commissioners for

the City of Jackson, Tenn., et al, decided by the United

States Supreme Court on May 27, 1968.

Faculty desegregation is practically nil.

There is a burden on the School Board to establish that

additional time is necessary to insure compliance at the

earliest practicable date of the requirements of the Green

(Walker v. County School Board of Brunswick County)

Findings of Fact and Conclusions of Law From the Bench

case.

6a

The Court finds from the evidence here that unless

this Court orders a plan, it might well be twenty to thirty

years under the existing plan before the result required by

the law would come about.

It is interesting to note, and the Court wishes the record

to show, that of all of the witnesses who testified here

today, all were members of the Caucasian race, though

the evidence before the Court is that there are members of

the Negro race in the community who are considered to be

what has been described in the pleadings as members of the

power structure, but not one has come here today to affirm

the evidence that has been introduced by the oral testimony.

There is a burden on the School Board to take whatever

steps are necessary to convert to a unitary system, and this

they have failed to do.

Any plan under the law must promise meaningful and

immediate progress toward desegregation. See Green v.

New Kent County, etc.

The Court finds nothing to indicate that the one plan

which has been offered, which is a continuation of the

freedom of choice, would promise meaningful and im

mediate progress as required. In the Court’s opinion, the

contra is true; that plan makes it unlikely that any progress

would ever occur.

No gentlemen, I have no doubt there is a burden on this

Board to fashion steps which promise realistically to con

vert to a system without a white school and without a Negro

school, but just schools. I am not unconscious of the emo

tional problems which you gentlemen have described, and

I hope you don’t think that I am. I feel sorry that folks

have those emotional problems, and I don’t say it face

tiously but I will offer my prayers for them because it

must be difficult for them. But if I were to sit here and not

take an affirmative step, I could never live with myself for

(Walker v. County School Board of Brunswick County)

Findings of Fact and Conclusions of Law From the Bench

7a

the harm that would be done to the children of Brunswick

County. If I don’t do what I am about to do, then I have

hurt the children of Brunswick County because it would be

just one generation after another with this same problem.

As one witness said, it may be forever.

Now, that is too late.

All right. Is there any misunderstanding that the free

dom of choice as heretofore approved by this Court is

wiped out? I don’t want any doubt about it. It is gone,

so far as this Court is concerned, as of the end of this

school year.

I am satisfied that there are sufficiently mature Amer

icans of greater capacity for educational benefits than I,

who reside in Brunswick County; and I include the mem

bers of the School Board, the faculties, and the Superin

tendent of Schools. Hence, I am going to direct or grant

leave to the defendants to file with this Court a plan which

will accomplish that which has to be accomplished, and we

all know what it is. In the event that such a plan is not

forthcoming, and I would ask counsel to notify me imme

diately if there is any doubt that it is going to be forth

coming, then I shall have to draft one myself, which I don’t

want to do. I will need everyone’s help if I do it, but it is

going to be done.

I will direct that it be forthcoming within one month,

and within three days after it is filed the plaintiffs are to

file any exceptions, and within two days after that, unless

the two days fall on a Sunday, this Court will enter an ap

propriate order; and if you all wish to be here again you

can be here at eight o’clock that morning, whatever day it is,

and that includes Saturdays, and I will enter the order

on that day.

/ s / R obert R . M erh ige , J r .

United States District Judge

(Walker v. County School Board of Brunswick County)

Findings of Fact and Conclusions of Law From the Bench

8a

Order

(Walker v. County School Board of Brunswick County)

December 9, 1968

Whereas, under date of October 23, 1968, the defendants

were directed to file with the Court by November 4, 1968 a

detailed plan for total desegregation of the student body

and faculty of each school referred to in defendant’s An

swers to Interrogatories filed in this cause, and the defen

dants having failed to so do, the Court did after an ore

tenus hearing on November 8, 1968, dictate its Findings

of Fact and Conclusions of Law From the Bench, and did

grant leave to the defendants to file a plan which would best

result in the public school system of Brunswick County,

Virgina, being in compliance with the decision of the

Supreme Court of the United States in Green v. County

School Board of Neiv Kent County;

And, it appearing to the Court that the defendants have

not seen fit to file any such plan, but have instead on De

cember 6, 1968 filed what is styled a Report; and the Court

deeming it proper so to do for the reasons assigned from

the bench at the conclusion of the hearing on November 8,

1968, doth A djudge , Order and D ecree :

1. That the defendants herein, their successors, agents

and employees, be, and they are hereby mandatorily en

joined, permanently, to dis-establish the existing dual sys

tem of racially identifiable public schools being operated

in Brunswick County, Virginia, and to replace that system

of schools with a unitary system, the components of which

are not identifiable as either “White” or “Negro” schools.

2. The defendants are further directed to cause by Sep

tember 1, 1969, the assignment of the faculties of the

9a

(Walker v. County School Board of Brunswick County)

Order

schools of Brunswick County, Virginia, in such a manner

as to dissolve the historical pattern of segregated faculties.

3. The defendants are further enjoined to file with this

Court a detailed plan leading to the implementation of

pairing of classes in all schools in Brunswick County, Vir

ginia, to be effective as of the school term commencing in

September 1969, as suggested in the report attached to

defendants’ pleading of December 6, 1968.

4. The defendants are further ordered to report to the

Court by no later than May 15, 1969, the anticipated en

rollment of each school in Brunswick County, Virginia, as

well as the racial composition of the student body of each

school and the racial composition of the faculties of same.

Let the Clerk send copies of this order to all counsel of

record.

It is further ordered that copies of this order be served

by the United States Marshal on each of the defendants

herein.

/ s / R obert R . M ebhige , J r .

United States District Judge.

December 9, 1968.

10a

Order

(Hawthorne v. County School Board of Lunenburg County)

Pursuant to the Court’s announced Findings of Fact

and Conclusions of Law made from the bench at the hear

ing on this matter, and deeming it proper so to do, it is

A djudged , Ordered and D ecreed :

1. That the defendants herein, their successors, agents

and employees he, and they hereby are, mandatorily en

joined, permanently, to disestablish the existing dual sys

tem of racially identifiable public schools being operated in

the County of Lunenburg, and to replace that system of

schools with a unitary system the components of which are

not identifiable with either “white” or “Negro” schools, all

as of the commencement of the school year 1969-70.

2. The defendants are further directed to file with this

Court within thirty days from this date a plan of deseg

regation based on the pairings of grades in the school

system of Lunenburg County, to the end that a unitary

system be established and put into effect with the com

mencement of the school year 1969-70.

3. The defendants are further directed, commencing

with the school term September 1969-70, to cause the as

signment of the faculties of the schools in Lunenburg

County in such a manner as to dissolve the historical

pattern of segregated faculties and to cause the faculties

of each of the schools to be composed of at least 25% of a

race different from that of a majority of the students in

each respective school.

Let the Clerk send copies of this order to all counsel of

record.

Nunc pro tunc December 30, 1968.

* # *

11a

Findings of Fact and Conclusions of Law

as Stated From the Bench

(Hawthorne v. County School Board of Lunenburg County)

F I L E D

FEB 19 1969

CLERK, U. S. DISX. COURT

RICHM OND, VA.

Before: H onorable R obert R. Meehige, J r .

United States District Judge

T h e C o u r t : Gentlemen, the Court will attempt to give

its find ings of fact and conclusions of law.

This suit is brought by three infants by their father and

next friend, against the County School Board of Lunen

burg County, Virginia, the Superintendent of Schools, and

the members of the Board. Jurisdiction of this Court is

attained under the 14th Amendment to the Constitution,

and the Court has jurisdiction under Title 42, § 1981.

The Court treats this as a class action and rules that the

plaintiffs have an absolute right to maintain it. Plaintiffs

are Negro citizens of the Commonwealth of Virginia. Much

of the allegations is admitted in the Answer.

It is admitted by the defendants that prior to 1954, the

School Board established and operated a bi-racial school

system as was required by the laws of Virginia at that

time. The Court finds as a fact that Lunenburg County

School Board operates a total of seven schools, two of

which are high schools with grades 8 through 12, one of

which has grades 1 through 6, and the others grades 1

through 7.

In the seven schools, the Court finds that there are 1,385

White students and 1,567 Negro students. One of the

schools, Central High School, with a capacity of 600 stu-

12a

dents, jjresently has slightly over that attending, of whom

573 are White and 66 are Negro; with 33 White teachers

and 2 Negro teachers, who do not in fact teach academic

courses but are used either in the physical education de

partment or in an elective course. In Lunenburg High

School, which is an all-Negro school, there are no White

teachers at all. In Kenbridge Elementary there are 308

White and 41 Negro pupils; and there are 16 plus White

teachers and 2 part-time Negro members of the faculty,

one of whom is associated with the band. In any event,

there are two part-time teachers.

The Court finds there are no Negro teachers whatsoever

as regular classroom teachers in White schools. Nor are

there any White teachers as regular classroom teachers in

Negro schools.

The Court finds that there is no residential racial zoning

in the county; that members of both races live throughout

the entire county. The Court finds from the evidence be

fore it that a plan of zoning would not be feasible.

Each of the high schools teach generally the same sub

jects, one difference being that in Lunenburg High School

there is taught brick masonry, general music and business

law, which are not taught in the other school. In the Cen

tral High School there is taught Spanish Distributive Edu

cation and vocational drafting, which as the Court under

stands the evidence, are not taught in Lunenburg High

School. However, generally, the courses are the same.

The Court finds that the athletic programs are similar.

There is no baseball at Lunenburg High School because

of an apparent lack of enthusiasm on the part of the stu

dent body, and not because of any action of the defendants.

(Hawthorne v. County School Board of Lunenburg County)

Findings of Fact and Conclusions of Law

as Stated From the Bench

13a

The Court finds that there is no athletic competition be

tween the high schools.

The Court finds that the school operates a segregated

bus system. There are 41 busses that operate throughout

the county and pick up the children by schools arid not by

routes. For all practical purposes, there is a segregated

bus system operated in the County.

The Court finds that the defendants chose the freedom

of choice system in 1965-66, and in the first year 66 Negro

students chose to go to formerly all-White schools. The

number has now, going on four years later, increased to

140. Not the first White child has chosen to go to a for

merly all-Negro school. The Court finds there is no real

freedom of choice plan in Lunenburg County—there is

s im p ly a right to choose the school one wants to go to,

but no provision is made in the event an excess number of

children of a particular race choose a school of a different

race. No provision whatsoever has been made in that re

gard.

It has been suggested that if the freedom of choice plan

is not approved by this Court, and any other plan is or

dered by the Court, that there will be a mass exodus by

the White students by virtue of their parents’ transferring

them. That argument is not a viable argument and was

answered in the Monroe case wherein Justice Brennan

stated that it goes without saying that vitality of the

Constitutional principles cannot be allowed to yield simply

because of disagreement with them.

The Court finds that there has been no effort by the

defendant school board to do away with the dual school

system which is now operated in Lunenburg County.

(Hawthorne v. County School Board of Lunenburg County)

Findings of Fact and Conclusions of Law

as Stated From the Bench

14a

The Court finds that the school superintendent has a

right to assign teachers, under their contract, to any school

he sees fit, but he has not exercised that right, stating that

it is done only under extraordinary circumstances.

The Court finds there are no attendance zones for the

schools; each school serves the entire county.

The Court finds that the teachers are, in fact, assigned

in a racially discriminatory manner, which is a violation of

the mandate of the United States Supreme Court and can

not stand.

The burden is on the School Board to establish that

additional time is necessary in order to fully effectuate the

requirements of law and the rights of these plaintiffs and

all others in the county, and the Board has not sustained

that burden. There is not a scintilla of evidence before the

Court which the Court accepts as being factual which would

indicate that a freedom of choice would at any time within

the reasonably near future result in the abolition of the

dual system of schools. The fact that the School Board

opened the White schools to Negro children under their

freedom of choice was merely the beginning. It is merely

the first inquiry as to whether it will lead to the end of a

dual segregated system as required in the Green v. New

Kent case.

The Court finds no meaningful assurance of prompt or

effective disestablishment of the dual system, and that

there are no real prospects as it now exists. The Court

further finds that the best plan, in order to establish that

which is required, would require that the Court manda-

torily enjoin the defendants, and they are as of this day

enjoined from the operation of their school system under

(Hawthorne v. County School Board of Lunenburg County)

Findings of Fact and Conclusions of Law

as Stated From the Bench

15a

their present freedom of choice, effective with the Septem

ber term 1969.

In addition to the Court accepting the defendants’ tes

timony that the only other educational alternative is a

pairing, the Court directs that the defendants file with the

Court within thirty days from this date a plan of pairing

of classes, to the end that there is an abolition of White

and Negro schools, and that we attain only schools, neither

White nor Negro.

In addition, the Court requires that the defendants file a

plan concerning the assignment of faculty, which will result

in an assignment in such a manner that at least twenty-five

percent of the faculty are assigned to schools formerly

composed of a majority of the opposite race. These things

are not easy for the people to accept, and I understand

that. I am not unsympathetic with their plight, but this

condition was brought about by virtue of the State impos

ing segregation, and it does no good to do it piecemeal

because in this instance the Court finds it wouldn’t work,

it simply would never come about. The only way it is going

to come about is to do it promptly and meaningfully. I do

not wish to be the Superintendent of Schools of Lunenburg

County, but the United States Supreme Court has issued

a mandate, gentlemen, and we are going to abide by it.

If we have to, we have to.

I thank you all for your help.

(Hawthorne v. County School Board of Lunenburg County)

Findings of Fact and Conclusions of Law

as Stated From the Bench,

ME1LEN PRESS INC. — N. Y, C. -'tjv..- 219