State ex rel. Lockert v. Crowell Opinion and Dissenting Opinion

Public Court Documents

March 31, 1982

Cite this item

-

Case Files, Bozeman & Wilder Working Files. State ex rel. Lockert v. Crowell Opinion and Dissenting Opinion, 1982. 63722136-ee92-ee11-be37-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/3a1fa3fd-d7af-4f56-9f38-ae0baefba0cf/state-ex-rel-lockert-v-crowell-opinion-and-dissenting-opinion. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

IN TIID SUPREME COURT OF TtrNNESSEE

AT i.iASIJVILLE

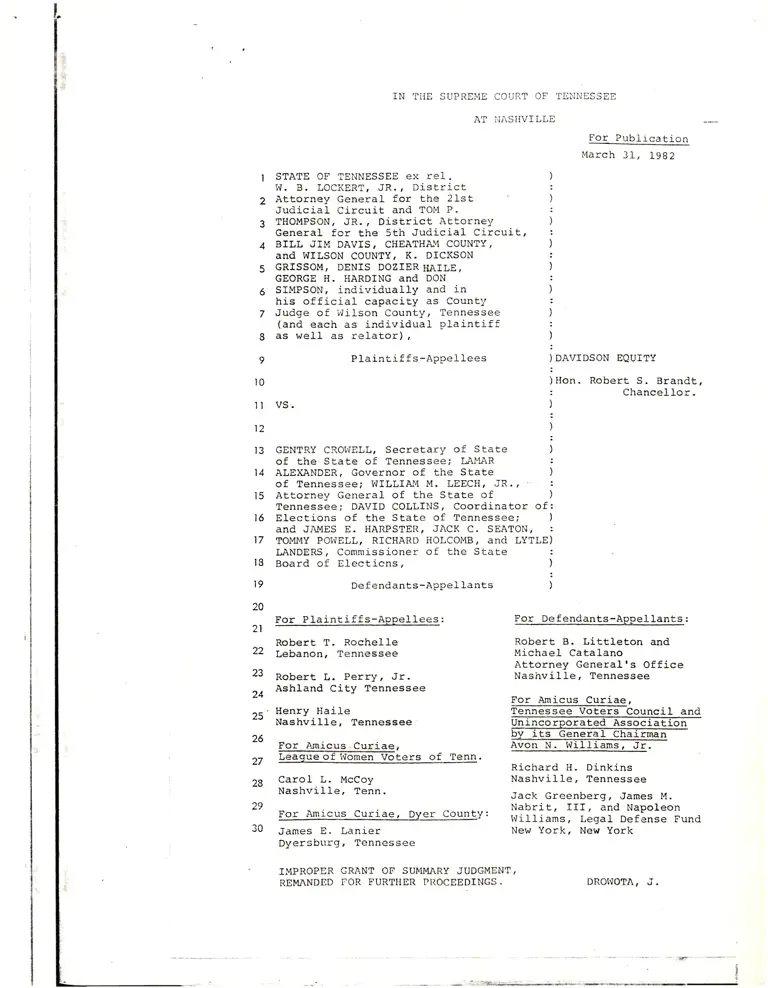

STATE OE TENNESSEE CX TCl.

w. B. LOCKERT, JR., District

At.torney General fpr the 21st

Judicial Circuit and TOI{ P.

THOMPSON, JR., District Attorney

General for the 5th Judicial Circui-t,

BILL JIM DAVIS, CHEATHAM COUN?Y,

And WILSON COUNTY, K. DICI(SON

GRISSOM, DENIS DOZIER TIAILE,

GEORGE H. HARDING and DON

SIMPSON, individually and in

his official capacity as County

Judge of l,iilson County, Tennessee

(and each as individual plaintiff

as well as relator),

P lainti. f f s -Appe1 Iees

Tennessee; DAVID COLLINS, Coordinator of:

Elections of the State of Tennessee; )

and JAI4ES E. HARPSTER, JACK C. SEATON, :

TOMT4Y POTVELL, RICHARD HOLCOMB, and LYTLE)

LANDERS, Commissi.oner of the State

Board of Electj.cns,

Def endants-Appel lants

For Plaintif f s-Appellees :

Robert T. Rochelle

Lebanon. Tennessee

Robert L. Perry, Jr.

Ashland City Tennessee

Henry Haile

Nashville, Tennessee

For Amicus Curiae,

GENIRY CROIVELL, Secretary of State

of the State of Tennessee, LAI'IAR

ALEXANDER, Governor of the State

of Tennessee; ITIILLIA]4 M. LEECH, JR.,

Attorney General of the State of

League of i^Iomen Voters of Tenn.

Carol L. Mccoy

Nashville, Tenn.

For Amicus Curiae, Dyer County:

James E. Lani-er

Dyersbnrg, Tennessee

IMPROPDR GRANT OF SUMMARY JUDGMENT,

REMANDBD IIOR F'URT}IER PIIOCEEDINGS.

For Publi.cation

March 31, 1982

DAVIDSON EQUITY

Hon. Robert S. Brandt,

Chancellor.

)

)

)

F or Def endants-Appellants :

Robert B. Littleton and

Michael Catalano

Attorney Generalrs Office

NashvilIe, Tennessee

For Amicus Curiae,

Tennessee Voters Council and

l0

1',t vs.

12

l5

l3

t4

t6

t7

t8

t9

20

2t

22

23

24

25

27

28

Unincorporated Association

Pv itt GSIgI?i chal

Avon N. hrilliams, ir.

Richard H. Dinkins

Nashville, Tennessee

Jack Greenberg, James M.

Nabrit, IIf , and l.Iapoleon

Irlilliams, Lega] Defense Fund

New York, New York

I

I+

DROI']OTA, J .

I

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

l0

il

t2

l3

t4

I5

r6

17

l8

I9

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

g_ 3_r_jJ_l_g- N

Thi-s case comes to us on direct .ppe.Il from the Chancell,or,s

-.grant of plaintiffs' motion for summary judgment. The primary

question presented is the constitutionality of the Senate

Reapportionment Act. of L}BL,2 which Act reapportioned the State

Senate in response to the 1980 federal decennial census, as

required by Art. fI, S 4 of the Tennessee Constitution. The

defendants cite as error the ChancelLor's holding that the Act

"contravenesArticle I1, S 6 of the Tennessee Constitution pro-

viding that no county sha11 be divided in forming a senate

di.strict, and the contraventi.on of Art. fI, S 6 is not neces-

sary to meet the 'one person, one vote' requirement of the

equal protection clause of the Fourteenth Amendment to the

United States Constitution" and is therefore unconstitutional.

The ChancelLor also enjoined the defendants from conducting any

prlmary.or general election under the Act.. For reasons set out

be1ow, we hold that this was not a proper case for summary judg-

ment and we remand this cause to the trial court for further

proceedings consistent hrith this opinion.

HISTORY And BACKGROUND

The action was brought on November 17, 1981, by the

following plaintiffs: the counties of Wilson and Cheatham, by

thej.r District Attorneys General; the Senator representing

District 27 under the prior apportionment act, whose incumbency

was in effect abolished by the Act; ancl citizens an<l registered

voters of Bedford, Cheatham and !,lilson Counties, one of whom was

a Wilson County Conunissioner and another of whom was Wilson

County Judge and ex officio Chairman of the County Commission.

The plaintffst standing to sue is not in issue. Defendants are

the Secretary of State, Governor, Attorney General, Co-ordinator

Jurisdiction of this appea] Is 1n Lhe Supreme Court pursuant

r.c.A. s 16-4-108.

Ch. 538, PubIic Acts of 1981; l.C.n. S :-f-fO2(I98I Supp.)

1.

to

2.

I of Electj-ons and Commissioners of the State Board of

2 Elections.

3

4 lhe amended complaint alleged three causes of action.

5 One of these was that in this reapportionment, district lines

6 were redrawn and voters were transferred from odd to even

, numbered districts, and vice versa. The effect of this would

, be to preclude many voters from voting in a Senate race as

, frequently as every four years, contrary to Art. I, S 5 of the

lO Constitut.ion. fhe Chancellor held that this was a necessary

ll by-product of reapportionment and did not violate the Constitu-

12 t.ion.

I3

14 Another cause of action hras that the Act violated

15 Art. If, S 3 of the ConsLitution in failing to number districts

l6r conseeutively in a connty having more than one senatorial district.

17 The Chancellor reserved this issue in vievr of his holding that

18 the Act was unconstitutional for another reason and that the

t9 Senate districts must be redrawn.

20

21 The third, and principal, cause of action was that the

22 AcX clearly violated Art. II, S 6 of the Constitution, which

23 reads:

24

The number of Senators shall be apportioned

25 by the General Assembly among the several

counties or districts substantially according

26 to population, ancl shall not exceed one-third

the number of Representatives. Counties having

27 two or more Senators shall be divided into

separate districts. In a district composed of2E two or more counties, each county sha1l adjoin

at least one other county of such dist,rict; and29 !C coung. shal1 be dividEcl in forming such a-

dTsEfdEI

30

The emphasized phrase was in our original Constitution of L796L

and found in the subsequent Constitutions of 1835, 1870 and 1956.

I

, Ti:e defendants moved for summary judgment based

3 upon exhibits which showed that the Act complied with the

, "one person, one vote" requirernements of the United States

, Constitution. Based upon population, the "ideaI" district size of

U a 33-member Senate is 139,114, under the 19b0 census. The

7 greatest positive variance from thls size rras +.738, and the

g greatest negative variance -.92\, for atotalmaximum variance

, of 1.658. Thus, the plan was close to mathemat.ical Perfection.

lO Defendants argued that if these requirements rreremet, there was

no basis under the Tennessee Constitution on which to hold the

Act invalid.

P1ai-ntiffs filed a crf,ss-motion for sunmary judgment

parties, and

II

t2

l3

l4

15 based upon the complaint, certain stipulations by the

'16 affidavits. The st,ipulations included the following

17 pertinent to the principal issue:

l8

matters

l9

20

21

22

23

24

27

28

29

l. A map of the districts established under the Act.

2- A statement that the optimum district size for

a 33-member Senate was I39,114.

3- Charts shovring the population of each district

under the Act, the population of each county and parts of coun-

ties in each district, the raw number and percentage variance

25

of each district from ideal size, the totaL maximum variance,

26

the distributj.on of variance, the average variance, and similar

statistics agreed to be true.

4. A 3O-member and a 3l-member plan proposed by

cross any county lines. The30 plaintiffs, which would not

I 30-member plan had an ideal district size of ]53,025, and the total

2 maximum variance was t4.46E and -5.988, or 10.448, The 3I-member

3 plan had an ideal district size of 148,101, with a total naximurn

4 variance of 13.82t.

5 s. A 33-member plan which crossed the lines of only

6 ,h"lby, Davidson, and Knox Counties. Ilamilton county was divided

7' j-nto trvo districts, but no part thereof was joined in a district

8- with any other county. The total maximum variance of this plan

I

was stipulated to be 9.992.

l0

6. A stipulati.on as to the instructi.ons given to Mr.

1I

Frank D. Hinton, Director of Local Government, OfficeofComp-

t2

troller of the Treasury, by the Senate for his guidance in pre-

't3

paring proposed reapportionment plans: "(a) that all- districts

14

should be as near to mathematj.cal perfecti-on as possible, but

l5

at the same time the districts should split as few counties as

t6

possible; " (b) that, disEricts should keep the same numbers they

t7

had previously had, or at least their odd or even numbered status;

I8

19 and "(c) that, if possible, no two (2) incumbents in the State

ZO Senate should be placed in the same district. "

2t

22 The defendants filed the affidavit of Frank D-

23 Hinton, addressj-ng tire dif ficuities of irarving a 33-inember

24 plan which did not cross county lines. It stated that the

25 primary problem arose in the four metropolitan counties because

26 their populations are not multiples of the ideal population

27 of 1391114. A chart set out the percentages of variance for

Zg each of these counties if no county Iines vrere crossed, from a

2g low variance of +3.419 in llarTLiltc:r County to a high of +14.893 in Knox

30 County. It conclucled that since each of these variances was

I

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

t0

ll

l2

t3

l4

t5

l6

t7

t8

l9

20

2t

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

posj-tive, with the lowest of the four figures being 3.411, "some

of the multi-county districts will have a negative variance from

optimum district size, Attempts to draw such a thirty-three

member plan result in a total gross variance (combining greatest,

positive and greatest negatj.ve variance) of over 221."3

The motions for summary judgment lvere argued February

9, L982. On February 18, the ChancelLor entered a Memorandum

opinion, and on February 23, his Decree.

In addition t,o the above-mentioned parties, the

following have participat.ed in the appeal fro:n this Court

as amj.ci curiae: the League of ilomen Voters, the Teanessee

Voters Council, and Dver Count7 tirrouEh i.gs County

Attorne-v.

JUSTICIABTLTTY

A threshold issue decided by the Chancellor and appealeC

by the defendants 1s thaE the complaint presented a justiciable

issue. The defendants charge that reapportionment is non-

justiciable because it is a political question and because j.t

is a legislative function under the Separation of por^rers Doctrj.ne.

They further argue that, should the courts declare the Act un-

constitutional and the General Assembly fail to pass a constitu-

t,j.onal act, the courts would be $rithout por.rer to grant the

ultimate remedy of formulating their orvn reapportionnent plan.

ffin=inton's f igures, and the manner Ln whrcn vre ccnclude

he arrived at. them, are di-scussed in footnote 5 of thii opinion.

I

2

2

4

5

6

7

8

9

IO

1l

12

I3

14

l5

l6

17

IB

19

20

2t

22

23

24

a<

26

27

28

29

30

fn view of the evolution in t-his area of constitu-

tional law which has taken place since the United States

Supreme Courtts decision in Baker v. Carr, 369 U.S. 186, 82

S. Ct. 69L,1 L. Ed. 2d 663 (1962), we disagree,and affirm the

Chancellor's holding that this is a justj.ciable issue. See

Egan v. Harunondt 502 P.2d 856, 865 (Alaska L972); Legi.slature

of the State of California v. Reinecke, 1I0 Ca1. Rptr.7L8,

516 P.2d 6 (1973); White v. Anderson, 394 P.2d 333 (Co1o. 1964)i

Guntert v. Richardscn, 47 Hawaii 662, 394 P.2d 444, 449 (1964);

Butcher v. Bloom, 4l-5 Pa. 438, 203 A.2d 556, 559-560 (1954);

Smith v. Craddick, 47L S.W.2d 375 (Tex. 1971); In re Senate

PIILfZ, 294 A.2d 653 (Vt. 1972) i State v. Zimmerman, 22 WLs.

2d 544, 126 N.W.2d 551, 560-563 (1964); 25 Am. Jur. 2d Elections

S 32 (1966); 15 C.J.S. Constitutional Law S 147 (1956). These

and other cases relied upon in this opinion are replete r.rith

statements that apportionment is primarily a legislative func-

tion, and that the courts should act only if the legislature

fails to act constitutionally after having had a reasonable

opportunity to do so. If the court were forced in such an

event to devise its own constitutional plan, it would not in

effect be preempting the General Assembly.

CONTE}.ITIONS OF TI{E PARTIES

Plaint.iffs contend that they made out a prima facie

case of unconst,itutionality, because the Act crossed the

boundarj.es of 16 of the State's 95 counties in setting up

the thirty-three Senate districts. plaintiffs take the positj.on

that. there is no unavoiclable conflict between the Tennessee

constltutional prohibition against. dividing counties in forming

Sonate districts and the one person, one vote requirement of the

I

2

3

4

5

6

7

I

9

l0

ll

t2

t3

l4

t5

l6

l7

'18

19

20

2t

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

federaL constitution, if the number of Senators is reduced.

Plaintiffs introduced two plans reducing the number of senatoriar

districts to 31 and 30, which plans had rnaximum total variances

of 13.82t and 10.44t respectively. Plaintiffs aver that neither of

these plans crosses any county lines and the variances in

both plans meet the equal protection requirements.

Defendants contend that the division of counties is

necessary to comply with the "one person, one vote" doctrine

under the equal protection

"1"r"" of the E'ourteenth Amendment

of the United States Constitutj-on, as enunciated in Baker v. Carr,

369 U. S. 186, 82 S. Ct. 69L,7 L. Ed. 2d 663 (L962), and as

applied to state legislative bodies by Reynolds v. Sims, 377

u. s. 533, 84 S. cr. L362, L2 L. Ed. 2d 506 (1963).

The Senate reapportionment plan with a maximum

variance of 1.65t is close to mathematical perfection. The

plan divides sixteen counties, A thirty-three Senator plan

which conforms to Art. II, S 6 and does not divide countj.es would

produce a total variance of over 22t- Such a variance, defendants

argue, is far above the maximurn deviation permitted by the egual

protection clause. Defendants submit that there is an unavoid-

able confLict betleen the egual protection clause and the pro-

visions of Art. II, S 6 of our State Constitution, and the

Senate chose a plan which complied with the equal protection

clause -

Defendants aver that the two proposed apportionment

plans submit.ted by the plaintiffs to the trial court substantially

increase disparities in population over the present p1an. Defen-

dants contend that reducing the size of the Senate may raise

serious. constitutional questions relative to the represent.ation

of rninorities within the Senate. Defendants further aver that

I

i

i

I

I

-.-a.

..\r''.:--'

I

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

l0

il

t2

t3

l4

l5

l6

t7

t8

t9

20

2l

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

the detennination of Lhc number or senators is vested solery

in EheGeneral- Assembly and impositj.on of such a plan woulcl

abridge the Doctrine of Separation of powers.

Amicus curiae, the Tennessee Voters Council, contends

that minority groups vrhich are concentrated within a specific

area of a county, which now have representation in the State

Senate, should not be stripped of representation, by the adoption

of a 30 or 3I member Senate plan.

Amici curiae, League of Women voters of Tennessee and

Dyer Countyr s€ek affirmance of the Chancellor's decision holding

the Act unconstit,utional.

STATE AND FEDERAL CONSTITUTIONAL

REQUIREMENTS FOR REAPPORTIONI"IENT PI,ANS

A. Equal Protection - "One person. One Vote"

Ihere are several constitutional standards which the

Legislature must consiclcr in adopting a reapportionment plan.

Pirst and foremost is the requirement of equality of population

among districts, insofar as is practicable. Gaffney v. Cummings,

412 u.S.735,93 S. cr.232L, 37 L. Ed. 2d 298 (1973); Mahan v.

Hor^rell, 410 U.S. 3I5, 93 S. Ct. 979, 35 L. Ed. 2d 320 (1973);

Reynolds v. Sims, Ap,rg; Clements y. Va11es, 620 S.W.2d 112 (Tex.

1981); Smj-th v. Craddick, 471 S.W.2d 375 (Tex. 1971). Not only

is this requi-red by the Fourteenth Amendment of the United States

Constitution, but also it is required by Art. II, SS 4 and 5 of

the Tennessee Constitution.

Under the Act, the General Assembly created senat.orial

districts with a maximum total variance between the largest

and smallest districts of only I.65t. It should be remembered

that variances larger than this would be constitutional.

Indeed, the United States Supreme Court in lihite v.

Regester, 412 U.S. 755, 93 S. Ct. 2332, 37 L. Ed. 2d 314

(1973), and Gaffney v. Cummings, ggpE, held that those attack-

ing the s Late apportionment plans had failed to show a prima

facie equal protection violation where the maximurn total variances

I

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

t0

II

t2

I3

t4

ra

16

t7

'I8

19

20

2t

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

were 9.93 in lrlhite, and 1.8I? for the Connecti.cut Senate and

7.838 for the House in Gaffney. In llahan v. Ilowell, supra, the

Court held that a larger total variance may be constitutional

if it is jusLified i-n order to further a rational state policy.

fn particular, a variance of 15.48 was validated for the Virginia

House of DeLegates when the state's purpose therefor had been

to maintain the integrity of traditional iounty and city bounda-

rj.es. The Court ir BuEofgg_yr_qirt, 9gPE, recognized the

validity of maintaining political subdivision lines as justifying

deviati.on from mathemeti.cal perfection i-n drawing state (as

opposed to congressional) legislative districts.

From these cases, a "rule of thumb" appears to have

developed, whereunder variances of 10t or less need not be

justified absent a'showing of invidious discrj-mination; and

greater variances rvill be constitutional if the s tate has a

rational poli-cy in support thereof. Virginia's 16.4t variance

is the greatest vrhich, to our knowledge, has been found consti-

tutional, and the court in Mahan speculated that this approached

the limit of constitutional variance. Apportionment statutes

with variarrces greater than this have been struck down, see

Whitcomb v. Chavis, 403 U.S. L24, 91 S. Ct. 1858,29 L. Ed. 2d

363 (197I); Kilgarlin v. HilI, 386 U.s. 120,87 S. ct. 820,

t7 L. Ed. 2d

ct. 569, 17

77]- (L967); Swann v. Adams, 385 U.s. 440, 87 S.

L. Ed. 2d 50r (:..s67) .4

That is not to say that a plan with less than IOt

variance must, automatically be upheld in the face of an equal

protectj.on challenge. When the variance is less than lot, the

United States Supreme Court has held that there is no prima

4. Idhitcomb v. Chavis, Indiana reapportionment AcE, 24.78t in

tfre ffi the senate; Kilgarlin v. Hi11, Texas

plan, 26.5896i Swann v. Adams, Florida p1an, 33.558 in the

House and 25. EsE*-i;-ihe-EZi-ate.

10

I

i

I

I

I

I facie showing of unconstitutionality. plai.ntiffs in such a case

2 would have to prove more3 that the plan invidiously discrimi-

3 nated. We also do not hold that any plan with a variance of

4 up to 16.49 would be upheld merely because it did not cross

5 county lines', and because 16.4E was upheld for Virginia. As

6 the Court held in Reynolds v. Sims, igplg, ,,I.Ihat i_s marginally

7 permissible in one State may be unsatisfactory in another,

6 depending on the particular circumstances of the case." 371-

9 U.S. at 578. It later noted in Mahan v. Howe11, supra,

l0 quoting from Swann v. Adams, supra, ',the fact that a 10* or

Il ]5t variation from the norm is approvecl in one State has rittl_e

12 bearing on the validity of a similar variation in another state.',

13 410 u.s. at 328. rt must be remembered that "the Equar protect.ion

14 clause requires that a state make an honest and good faith effort

l5 to construct districts, in both houses of its legislature, as

16 nearly of equal population as i.s practicabre." Reynolds v. sims,

17 supra, 377 U.S. at 577. "For a State's polj_cy urged in justi-

l8 fication of disparity in distrlct population, however rational,

19 cannot const,itutionally be permitted to emasculate the goal of

20 substantial equality." Mahan v. Howel1, 9gpl3, 4I0 U.S. at 325.

2l

22 Applying these principles to the reapport,ionment of

23 the Eennessee senate, we feel that the vari-ance betrueen rargest

24 and smallest districts could increase substantially in order to

25 preserve county boundaries and comply with other constitutional

26 standarcls. See Sullivan v. Crowell, 444 E. Supp. 606 ($I.D. Ienn.

27 1978), wherein a reapportionment among several House districts

28 increased the variance from 4.51E to12.519 in order to avoid

)s

having voting precincts wherein voters were in two clistricts.

30

The court held that this r.ras a valid reason for increasing the

'tr

11

I

2

I

5

6

7

I

9

l0

lr

12

I3

14

t5

l6

17

t8

l9

20

2l

22

aa

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

variance. Ilowever, if a plan couid be devised which would

achieve the same end while maintaining much Lower variances,

the 12.518 variance ivould be unconsitutional. Yet the equal

protection factor should certainly not be thrown to the winds.

Specifically, the record indicates that the best 33-Senator

plan which can be drawn without crossing any county lines vrould

have a maxi-mum Cotal vari-ance of over 22U.5 We cannot conceive

of such a plan being held constitutional. The one person, one

vote principle would require a variance of substantially less

than this.

B. Dilution of Minority Voting StrengLh

There is a second issue which, like the equal protec-

tion issue, falls under the United States Constitution. Ihis is

the issue, raised for the first time on appeaL to this Court by

aroicns curiae Tennessee voters Council, an unincorDorated asso-

ciation, by the General Chairman Avon N. l,Ii11iams, Jr. , of

ffiffi

problem with variance j.n a 33-member plan not crossing county

Iines is in the major metropolitan counties. Oividing their

populations under the I980 census by the ideal dj.strict popula-

tion of 139,114, the Court can see that She]by County would be

entitled to 5.6 Senators; Ilavidson County to 3.4; Knox County

to 2.3; and liarnilton County to 2.1. If Shelby @unty r.rere given 5

Senators, each would represent 155,423 people, or 11.72t above

the norm. If it were given 6, each would represent, 129,;519

people, or 5.9E below the norm. If Davidson County were given

3 Senators, each would represent l.59,270 people, or 14.49t

above the norm. If it were given 4 Senators, each would

represent 119,453 people, ot L4.l3t below the norm. ff

Knox County were given 2 Senators, each would represent

L59,847 people, or 14.90t above the norm. If it were given

3 Senators, each would represent 106,5G5 people, or 23.4$'

below the norm. Since Hamilton County would qualify for 2.I

Senators, obviously it would be given 2, each of whom would

represent 143,870 people, or 3.48 above the norm. These are

figures which we can derive, and they correspond to fi.gures

used in the Hinton affidavit. The affidavit does not explain

his conclusion that the least possible variance in such a plan

is some 228; however, all parties conceded this figure as the

lovrest possible total vari.ance dur;ng oral argument.

L2

I

I

I

2

3

1

5

6

7

I

9

t0

II

t2

t3

14

t5

16

t7

l8

I9

20

2t

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

whether or not the Act is "a necessary means for avoiding an

unlawful dilution of minority voting strength"' Many United

States Supreme Court cases have dealt with the argument that a

certain form of legiilative districting, usually at-large, multi-

membor districting, has resulted in unconstitutional dilution of

minority voting strength. 9e9, 9.g., @,

446 U.S.55, IOO S. Ct. 1490 ' 64 L. Ed. 2d 47 (f980); I'lhite v.

Eg g, 412 U.S. 755, 93 S. C8.2332, 37 L. Ed. 2d 314 (1973);

Whitcomb v. Chavis, 403 U.S. L24, 9L S. Ct. 1858, 29 L. Ed. 2d

363 (I971-); and cases cited therein. These cases contain instrrjc-

tive statements as to what constitutes invidious discrimination

in this area, and what does not.

At the hearing on remand, evidence should be heard

concerning whet.her or not minorities are invidiously discri-mi-

natecl against by any of the aPportionment plans before the

courti and whether, assuming that the Act does not invidiously

discriminate, any alternative apportionment plan can be drawn

which also does not invidiously discriminate and yet conforms

to the guidelines for constitutionality under the Tennessee

Constitution set forth herein.

C. Prohibition Against Crossing county

Linesr Article II, S6

Ehe first two requirements discussed in Sections

A and B dealt with st,ate and federal constitutional standards.

Not dividing county ]j.nes is sole1y a state requirernent' If

there i.s an unavoidable conflict between federal and state

requj.remcnts as <jef<:n(iarnts assert:, ti'len the state requirements

become secondary to tire necessit! of complying r+ith the equal

protection clause. A11 of t,he parties erroneously assumed

that the only constitutional aLternative to the present

Act, which crosses 16 county lines, is a plan which crosses no

13

I

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

l0

ll

12

I3

t4

l5

t6

t7

t8

l9

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

county lines whatsoever. It was shown in the t.rial court

that. at least one 33 Senator plan can be clevj-sed which

crosses significantly fewer county lrnes t.han does the

Act, and yet clearly meets the egual protection guide-

lines delineated above. The prohibition against cross-

ing county lines sirould be complied with insofar as is

possible under equal protection requirements. There are excel-

lent policy reasons for the presence of a provision that counties

must be represented in the Senate. Mahan,v. Howell, supra;

Reynolds v. Sims, supra. As the complaint in this case alleges:

. Counties are divided and thus their

citizens are denied their constitutional right

to be represented in the State Senate as a

politlcal group by senators subject to election

by all voters grithin t,hat polit,ical group. These

plaintiffs aver that the legal and political

framework of Tennessee allows and requires that

the legislature enact legislation having only a

loca1 application. Thus the legislature has the

ability through loca1 legislation to directly

affect citj.zens merely because those citizens

reside in a particular county. Therefore, the

Iegislature has the right to govern citizens

in one county differently from cj-tizens. in

another county.

We find very

in Texas under the cases

(fex. 1971) and Clements v. ValIes, 620 S.w.2d 112 (Tex. 1981)

lhe pertinent provi.sion

dictated as follows:

of the ?exas Constitution (Art III, S 25)

1. I{henever a county has sufficient population to be

entitled to a Representative, such county shall form a separate

district.

2. i,Ihen two or more counties are required to make

up sufficient population for a districtl they shall be contiguous.

persuasive the Iaw which has developed

of Smith v. Craddick, 47L S.lf .2d 375

I4

I 3. When any county has more than sufficient popula-

2 tion to be entitled to a Represent.at,ive or Representatives, he

3 or they shall be apportioned to that county. For any surplus

4 population, it may be joined in a district with any other

5 county or counties.

6

7 The court first held that the equal protection reguire-

I ment took precedence, and "any inconsistency therehrith in the

9 Texas Constitution is thereby vitiated." 47L S.W.2d at 371.

IO

ll When federal requirements were "superimposed," as it

12 r.rere, upon the above provisions, the following e.ifects upon the

I3 State Consti-tution were had:

l4

Clause I: This would be effective only so long as

I5

county populat.ion was within the permissible limits of variance,

t6

17 Clause 2: when two or more counties are needed to

18 make up a district, "the only i.rnpairment of this mandate is

19 that a county may be divided if to do so is necessary in order

20 to comply with" the Pourteenth Amendment.

2t

Clause 3: This was nulli-fied. It became permissible

22

to join the portion of a county in which there was surplus

ZJ

24 population not in a district wholly within the county, with

25 contiguous area or another county t.o form a district. It \ras

26 still necessary for a county to receive the number of districts

27 to which its own population was entitled when the "ideal"

2g population was equalled or exceeded-

29

30 It was clear that the court interpreted the language

of iLs Constitution to nean that counties must be dealt hrith

l5

I as a whol-e, and that it allowed t.hat meaning to be softened

federal consti-only to the extent necessary to comply with the

tuion.

The plan passed by the Texas Legislature in Smith

v. Crad{ick, supra, cut the boundaries of 33 counties. Forty-

three of one hundred. fi-fty dlstricts contai.ned a portion of a

g county.

9

10

ll

12

As the court held:

IDefendants] offered no evidence to establish

that the wholesale cutting of county lines - .

was either reguired or justified to comply with

the one-man, one-vote decisions. The burden is

on one attacking an act to establish its invalidity.

lCitations omitted.l IPlaintiffs] proved conclusively

that the statute fails to do what is required by the

constitution in those respects discussed . . ibove.

No presumption of validity remains in the face of

that showing. If these districting requirements

were excused by the requirements of equal repre-

sentation, the Idefendants] had the burden of

presenting that evidence. They presented none.

l5

l3

t4

l6

l7

t8

t9

Id. at 378

The apportionment pl-an struck down in Clements v.

Valles, qqpre, also sets out t,he way in which the division of20-

counties failed to comply with the Smith v. Craddick guidelines -

These are analogous to the Tennessee Act. The TexasActcut 34

count,ies, 24 with surplus population and 10 with insufficient

population to form a district. The plaj_ntiffs presented numerous

alternative p).ans which more closely followed county lines and

25 stilI maintained permissible population deviations.

In Gaffney v. Cummings, 4I2 U.S. 735,37 L. Ed. Zd 2gg,

93 S. Ct. 232L (L973), the Supreme Court. considered the consti-

tutionality of a plan apportioning the Connecticut House.

In Connecticut, towns rather than counties are the basic

unit of local government The state Constitution provides

that "no town shall be divided" for the purpose of creating

2l

22

,?

24

25

27

28

29

30

15

I

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

l0

II

t2

t3

14

l5

l6

t7

l8

l9

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

llouse districts, except where districts are formed "whol]y

within the toi'rn." The Constitution further provj.des, as does

our own, that the "establishment of districts shall be

consistent with federal constitutional standards." The House

plan under scrutiny in Gaffney cut 47 boundary lines of the

state's 169 torrns. As in the case at bar, an action was

brought seeking declaratory and injunctive relief against

impJ.ementation of the p1an.

The complaint alleged that the plan erroneously

applied the Fourteenth Amendment so as to achieve smaller

deviations from population equality for the districts than

were required under the Fourteenth Amendment. In achieving

such unnecessary mathematical precision, the plan segmented

an'excessi-ve number of towns in forming the districts. At the

hearing in the fecleral districtcotrr't, plaintiffs introduced

three alternative apportionment plans that requi'red fewer

town-line cuts, although all three plans involved total devia-

tions from population equality in excess of the 7.83E contained

in the House plan. A fourth alternative plan was submitted

which had a maximum variation of only 2.5Lt^, but had no regard

for the integrity of town lines.

The district court invalidated the plan and enjolned

its future use in elections. The Supreme Court stayed the

district court's iudgment and upheld the original plan, which

violated the Connecticut Constitution's prohibj-tion against

crossing town lines. The Court made the following pertinent

observations:

L't

I . . From the very outset, ure recognized that

the apportionment task, dealing as it must hrith

2 fundamental "choices about the nature of repre-

sentation" Icitation omitted], is prirnari.ly a

3 political and legislative process. .

I Politics and political considerations

are inseparable from districting and apportion-

5 ment.

6

z it ,.":..j*l}';:ffiH::r'il:I;:';.T3'olE^"illE!3ol3i ",the political process and their voting strength in-

8 vidiously minimized.

9 412 U.S. at 749, 753, 754, 37 L. Ed. 2d at 310, 3]2.

t0

Thls case illustrates the point that, where necessary

lt

to meet federal constit,utional requirements, a state constitu-

12

tional provision may be violated to an extent, but sti]l must

l3

be given due consideration and all possible effect.

l4

l5

D. Contiguous and Consecutively Numbered

16 Counties

t7

I8 In addition to the above requirements in Sections

19 A, B and C, the courts must of course consider other

20 factors in passing upon the constitutionality of a state

2l apportionment plan. The counties in each district must be

22 contiguous (Art. If, S 6). In a county having more than

23 one senatorial district, such districts shall- be numbered

24 consecutively (Art. If, S 3).

25

26

NUIIBER oF sENAToRs

27

28 Another matter which must be addressed when con-

29 sidering state constitutional standards is the number of

30

18

I

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

l0

ll

t2

l3

14

't5

I6

t7

l8

I9

20

2l

22

ZJ

24

25

zo

27

28

29

30

members which the Senate can contain under a constitutional

plan. The stipulations made to the trial court included

both a 30 and 3I Senator plan, neither of which crossed

county l1nes. The variances were I0.44t and 13.828

respectively. The Chancellor noted these plans approvingly.

we, however, see several problems which should be weighed

when the LegisJ.ature is considering the advisability of

changing the number of Senators.

Certainly, it would be constitut.ional for the

Senate t.o contain fewer than 33 members. The Constitution,

Art. II, S 6, sets only the maximum size of the Senate,

at one-third the number of Representatives. Ho!.rever, themaximum

number of Representatives has been set at 99 since the

Constitution of 18356 and the number of Senators has

remained j-n actuaL practice one-third the number of Repre-

sentatives. The Code of 1884 set the number of Repre-

sentatives at 99 and the number of Senators at 33,

and the same composit.j-on has existed in

6.

L796

1835

1870

19 66

Number of l'lembers of

House

@i-tu-Ei6l[--

i

I

I

i

I

I

I

t

t

t

I

t

not less than 22

not more than 26

(11 counties)

not greater than 75

population reaches

milIion, thereafter

greater than 99

stune as in 1835

99 members

Senate

not less than I,/3

not less Lhan L/2

not greater than I,/3

same as in 1835

same as in 1835

until

I.5

no

l9

I

I

I

l

I

I

I

2

3

1

5

6

7

8

9

l0

il

t2

l3

l4

I5

t6

t7

r8

t9

20

2l

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

the House and Senate since that date.7 The franers of the

constitution and the LeEislature as earry as lgg4 sought stability

in the Generar Assembry by fixing the specific number of senators

and Representatives. For nearly 100 years the composition of

the senate has not changed. underpraintiffs' theory the number

of senators urould li):c1y increase or decrease after each decennial

census. TCA S 3-1-101 expressly mandates that there shall be

33 Senators, and the validity of this statute has not been

challenged in this action. ClearIy, the statute evidences a

legislative intent as to the number of Senators.

We contemplate another problem in reducing the number

of Senators. Under either a 3d or 31 Senator plan, the Senator

elected in the 32nd senatorial district in 1980 for a 4 year term,

specified by Art. II, S 3 of our Constj.tution, would have his

senatorial district abolished during his term of office. A

more serious problem in reducing the number of Senators has.

been raised by amicus curiae, 'tbat is, that reducing

tire size of the Senate rai,ses . constit.utional questions

relative to the representation of minorities within the Senate.

They contend that plaj-ntiifs' 30 anci 31 Senator plans

unlawfully dilu-e minority voting strength, particularly in

Shelby and Davidson Counties.

7. Composj-tion of the GeneraL Assembly provided by stat,ut.e:

Code of 1858, Art, IV, 99 House Senate

(Acts of 1851-52, ch. 197, S 4) 75 25

Code of 1884, Art. III, 114 99 33

Code of 1896, Art. IIf, 123 99 33

Acts of 1901, Ch. L22, S 2 99 33

Acts of f965 (8.s.), Ch. 3, S 2 99 33

(rcA s 3-1-101)

20

I

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

l0

II

t2

l3

l4

l5

l5

17

I8

l9

20

2t

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

In our view, the decision as to the number of

Senators b€longs to the General Assernbly;

it is a political matter. Art. II, S 4. tle shall

not intrude upon the legislative prerogative, being nindful of

the Doctrine of separation of Powers under Art. II. SS I and 2

of our Constitution. rhe General Assembly is perfectly free

to reduce the number of Senators by amending TCA S 3-I-10I, or

keep the mernbership at 33, so long as the apportionnent plan

ryhich it adopts otherwise meets constj-tutional standards.

TENNESSEE FEDERAL COUR" CASBS FROM THE 1970'S

Mention.should be made of ferieral district court cases

decided during the 1970's and discussing Tennessee aPport.ionment

plans under the United states Constitution. These cases, in

chronological order, are: Kopald v. Carr, 343 F. SupP. 51

(M.D. Tenn. l9'72); Whiee v. CroweII, 434 F. SupP. tlI9 (w.D'

renn. 197'7\; 9.qfl3!__y:_gro$re.U, 444 P. Supp. 505 (hI-D. Tenn.

1978);'and Mader v. Crowell, 498 F. Supp. 226 (M.D. Tenn. 1980)

Interestingly, Ch. 3, S 2 of the Public Acts of 1965,

which was expressly designed as a resPonse to Baker v. Carr,

supgg, did not divide.counties. KoPald deaLt $rith the General

Assembly's first apportionment pLan after the 1970 census, which

r.ras enacted in L972 arri actually consiste.l of a princ:pa.1.ard an alternate

plan. rt $ras admitted that the principal p1an, which did not

cross county lines, was unconstitutional; and that the alternate

plan,which crossed county lines,had over a 21t variance in the

House, principally from malapportionment in Knox and Shelby

Counties. The court made certain changes in these and Rutherford

I Counties, whichbrought thevariance to well below 10?. It

2 noted that apportionment was primarily a legislative functj-on;

3 that plaintiffs had submitted plans even more mathematically

4 precise; but that the evidence showed that "the resser mathemati-

5 cal precision of the [court's] plan may be justified on the

5 basis of legitimate state policy considerations." 343 F. Supp.

7 at 53-54 (emphasis added).

8

9 The opinion was issued $iay 22, 7972. The court.'s

l0 modified plan was effective for the 1972 elections, with the

ll Legislature given until July 1, 1973, t.o devise a constltutional

12 p1an.

t3

14 It is reflected in Flhite v. Crowell , $pE, that the

l5 Legislature passed the court-devised apportionment plan prior to

16 July 1, Lg73, cleadline. This plan crossed county'lines. white

17 dealt with 1976 changes in three Senate ("ciIIock Amendrrent") and t}ree Hor:se

lB districts in Shelby County. After the changes, the variance from

l9 ideal district sj.ze was j-ncreased, although even then the largest

20 of the six variances was only +3.304t. The changes were chal-

2l lenged in May, 1975, so that court t.ook no action at that time

22

since primary elections were so c1ose. .Ihe court, found that

23

the Legislature's reasons for making the changes were unjustl-

24

fied,so they $rere held unconstitutional. The case held that the

25

variances of the six district,s l^rould have been constitutional if

26

they had been part of the general 1973 reapportionment ordered

27

in Kopald. However, the variances which resulted from the 1973

28

reapportionment were much smaller than the 19'76 variances, thus

29

demonst,rating that the 1976 variances could be improved upon.

30

Clearly the court vras concerned with equal protection mandated

) ))

by the federal constitution almost to the exclusion of all

other considerations.

Egfl!\/g, allPx3, was actuaLly t,hree consolidated

the county to whi-ch they a1l belong. " 444 F. Supp. at GIO.

The court did not accept such an argument in that

case because

the record does not show that these

reapportionment measures have significantly

reduced the division of magisterial districts

in the affected counties. Nor does the record

show an attempt by the State to effect a state-

wide policy of "puttj-ng the counties back together. "

On this record, the courE does not find any rela-

tionship between county unification and the re-

apportionment legislation before the court.

I

2

3

4

5 cases, referred to as "sfllygl." D4fggg" and ,,Ne1son." rhe

6 Sullivan case d6aJ.t with four House districts altered by a 1977

7 acLi AlgooSldeal:t wit.h nine House districts altered by two 1976

8 actsi and Nelson dealt with seven House districts altered by

9 a L976 act.

l0

II In Qg[ivqn, the maximum total variance of the dis-

12 tricts in guestion was increased from 2.34t to 21.7g8; in

13 A1good, it was increased from 2.398 to 35.57t. lhe court

14 recognized that apportionment of state regislative districts was

15 judged with a more flexj-ble standard than congressional appor-

16 tionment; and that fairly large variances are tolerated when

17 they result from the even-handed implementation of a rational

18 state policy. Here, thc State's justification tras to ,'rput the

19 counties back together' by taking a small number of magisterial

20 districts of a county and isolated in a legislative district

2l and combining them with the larger number of other districts in

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

23

I Id. at 61I. Sinilarly, in qgeod, there was "no discerni.ble

2 legitimate reason" advanced to justify so greatly increasing the

3 variance in the affected district.

1

5 We agree with the court's holding in that the

6 variances in Sullivan and 119ood vrere signifcantly Larger than

7 any figure which has been held constitutional. Secondly, the

g creatJ.on of a huge varJ.ance would not be acceptable if only a

9 few magisterial districts v/ere unified. Third, the language

lO implies that if the record had supported the argument that the

ll State was t,rul-y trying to keep counties together, and if the

12 variances had been smaller, the reapportionment could have been

13 held constitutional.

t4

15 In Nelson, maximum variance among the seven affected

16 House districts was increased from 4.51t to 12.51t, a much

17 smaller increase. Also, at least part of the justification for

l8 the change rras to eliminate "split precincts" - precincts where

19 voters from two legislative districts vote at the same polling

20 p1ace. There was no question that split precincts cause con-

2l fusion, delays, J-ong Iines, and expenses for additional voting

22 machines. Thus, the court, held that their elimination "wouLd

23 be a valid reason for increasing population disparities among

24 legisfative districts to the 12.51 Percent level demonstrated

25 here, if no alternative creating less severe imbalances is avail-

26 abLe." Id. at 614 (snphasis added). I', agpeared Crat the glainLiffs had a

27 plan which would also eliminate split precincts while maintain-

28 ing lower variances. The General Assembly was instructed to

,o1' study the matter and take appropriate action. "The elimination

30 of sptit precinct,s cannot serve as a justification for

I

I

I

I

I

r

I

I

I

It-

I malapportionment if it. is possible to eliminate split precincts

2 while maintaining Iegislative districts of more nearly equal

3 population. " Id.

4

The Mader case was brought in March, 1978, to challenge

6 the 1973 reapportionment ordered in the 5.opal<! case. The court

7 issued its initial holdinq January 15, 1979, which is reported

8 as Appendix A to the opinion of March 27, L980, published at

9 498 F. Supp. 226. The 1979 opinion held the 1973 apportionment

lO unconstitutional because the maximum total deviation thereunder

ll was 18.03t, far greater than the approximately 4B deviation

12 under the plan devised by the Kopald court, under which the

13 1972 elections had been he1d. The State was unable to justify

14 the 18.03t deviation under the Legislature's p1an. Ihe court

l5 observed:

t5

Although defendants point out that Article 2,

17 section 6 of the Tennessee Constitution "pre-

fers districts that contain whole contiguous

l8 counties," (Defendants' Reply Brief and

Argr.unent, f iled November 3, 1978 , aL 7) ,19 deiendants have failed to indicate how the plan

under attack furthers this preference or even

20 that the preference rises to the leve1 of an

established state policy. Tennessee Code

21 Annotated section :-f-l-OZ creates a number of

districts that cut across county lines, andzz several of these districts deviate markedly from

the optimum. Although ljlahan Isupra] teaches23 that ither poricy consiGiEEiotlifght justify

.t exceptions to a general policy of observing

'q exiscing political boundaries, no such justi-

25 fications have been identified for the non-

contiguous districts now exj.sting in this state.

26

27 498 F. Supp. at 234.

28

29

30

25

I

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

l0

II

'12

l3

l4

I5

l5

17

.18

t9

20

2t

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

The court gave the Legislat.ure until June 1, Lg.|g,

to devise a nee, plan, and this deadline was complied with.8

Undersuch nev, plan, maximum total variance was a mere .g9t.9

In the second case, plaintiffs made no equal protection challenge,

but challenged the plan on two grounds not relevant in this appeal;

5-n any case, their challenges were not upheld. Nothing further

was said about districts crossing county Iines.

'* "o,i$o8$*' T'rt*Sfrrtr'm'RY

J UDGMENT -

The Chancellor granted plaintiffs' motion for summary

judgment "because the defendants have not demonstrated an

unavoidable confllct between Ithe prohibition against dividing

counties] of t,he State Constitution and the one person, one

vote requirement of the federal Constitution. " We cannot

reach the same conclusion based upon the limited record before

us.

Plaintiffs shoued that the Act violates the

stat,e's constitutional prohibitions against crossing county

lines, Art. II S 6. The burden therefore shifted to the

defendants to shov, that the Legislature was justified in pass-

ing a reapportionment act which crossed county 1ines. ft hras

stipulated that the Senate reapportionment plan, whj.ch crosses

county lines, has a maximum variance of 1.65t. This variance

clearly meets the federal requirement of equality of population

among districts.

8. The State had appealed the January order to the United-

States Supreme Court. The Court in 1i9ht of the General

Assembly's action, ultimaEely remanded t,he cause to the

district court for such further pr:oceedings as might be

appropriate. EqqI_I v. t-tader, 44 U.s. 505, 100 S. Ct.

g-g1, -az L. Ed.U-7d'il8-8'6j.

9. Under the pIan, 22 county lines r.rerc crossed, and 20

Senate districts containecl part of at least one county joined

with at least one other county.

26

The defendants aver and the plaintiffs concede that

a 33 member apportionment plan, not crossing county fines, would

I

result in a total gross variance of over 22t. I,Ie hold such a

2

variance exceeds the maximum deviation permitted by the equal

3

protection clause of the pourteenth Amendment. We thus have

4

an unavoidable conflict, unless we were to holcl, based upon the

5

bare conclusory evidence presented, that the 31 and 30 member

6

plans, whi.ch cross no county lines, meet the federal constitu-

7

-tional requirements for reapportionment pJ.ans. It has beenI

stipulated that these plans have maximum total variances of

9

13.828 and 10.448 respectively, which plans would in all

l0

probability meet the equality of population requirement of theII

state and federal constitutions. Hohrever, the record fai.Ls to

t2

establish whether either plan dilutes minority voting strength.

I3

This is a serj.ous question, one which was raised by amicus curiae

t4

for the first time on this appeal, and one whj-ch has not been

l5

considered by the ChancelLor.

t6

t7

lg Whether the state made an honest and good fait.h

lgeffort to const.ruct senatorial districts which comply with both

^^

federal and state constitutions is an issue of fact which we

ZU

,, believe requires a fuII evidentiary hearing as does the questi.on

,rof iust.ification. The part.ies should also be allowed to properly

,, develop and present evidence on whether or not the Act is a

24 n€cessary means for avoiding an unlawful dilution of minorj_ty

25voting strength.

26

27 IrIe hold that this was not a proper case for summary

29 judgment,. There remained disputed questions of material fact

29as to whether the plan under the Act rsas actua]Iy necessary,

30in view of other action which the Legislature could have taken,

in order to comply wj-th paramount constitutional standards.

21

I This cause is therefore remanded to the chancery court of

2 Davidson county, the defendants shall fire their ansvrer, and

3 this cause sha11 proceed to a hearingr on the merits.

4

5 As a guide to the trial court and the General

6 Assembly we recapitulate our holding:

7

8 t. The popuJ.ation variance under the Act can be

9 i-ncreased and stil1 comply with equar protection standards.

l0 The variance should be as low as possible,because equarity of

'l I population is sti.lr the principal considerati.on. The vari_ance

lz certainly should not be greater than any figure which has been

13 approved by the United States Supreme Court; nor would such

14 maximum figure automatically be approved, because the variance

15 for any state will be judged solely by the circumstances present

16 in that state.

t7

l8 2. primary consideration must also be given to

19 preserving minority strength to the extent required by united

20 states supreme court, cases cited above. The chancerlor should

21 consider whether the reapport,ionment Act or any other plan

22 unconstitutionally dilutes the opportunity of minorities to

23 parti-cipate in the political process.

24

25 3. The provisions of the Tennessee Constitution,

26 although of secondary import to equar. protection requirements,

27 are nonetheless valid and must be enforced insofar as is

28 possible. rf the state is correct in its insistence that there

29 is no way to comply rvith the mandates of the federal and state

30 const.itut,ions without crossing'county rines, then we hold that

the plan adoptecl must cross as few county lines as is necessary

to compLy with the fcderal constit.utional requirements.

28

I

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

t0

II

t2

l3

14

l5

t6

t7

I8

t9

20

21

22

n)

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

4. In addition to equal protection, preserving

minority voting strength, and not crossing county 1ines,

constitutional standards which musL be dealt with in any

plan include contiguity of territory and consecutive numbering

of districts.

Although the law on this point is not fully developed,

the cases indicate that political considerations are a realiLy

and also have a place in the creation of legislative districts.

See White v. Weiser, 4L2 V.5.783, 79L' 93 S. Ct. 2348, 37 L.

Ed. 2d 335 (1973),' Gaffney v. Cummings, 9!!I1, 37 L- Ed. 2d at

3I2- But see Leqislature of State of California v. Reinecke,

110 Ca]. Rpt,r. 718, 516 P.2d 6, I0 (1973).

The order sustaining plaintiffsr moti-on for summary

judgment is overruled and the cause remanded to the Chancery

Court of Davidson County for further proceedings in accordance

with this opinion. The injunction issued by the Chancellor

enjoining the defendants from conducting any Primary or

general election under Chapter 538, Public Acts of I981, is

dissolved. The costs incident to this appeal will be divided.

equally betrveen the Partie5; all other costs will be assessed

by the trial judge.

Harbison, C. J.,

Fones and Brock,

Frank F. Drourota,

and Cooper, J., concur.

JJ., dissent.

iii,-i[ffiE;

IN THE SUPREME COURT OF TENNESSEE

AT NASHVILLE

2

I

9

t0

il

STATE OF TENNESSEE ex reI.

W. B. LOCKERT, JR., District

Attorney General for the 2lst

Judicial Circuit and TOM P.

THOMPSON, JR., District Attorney

General for the 5th Judicial Circuit,

BILI JIM DAVTS, CHEATHAM COT'NTY,

And WILSON COUNTY, K. DICKSON

GRISSOM, DENTS DOZIER HAILE,

GEORGE H. HARDING and DON

SII4PSON, individually and in

his official capacity as County

Judge of wi.lson County, Tennessee

(and each as individual plaintiff

as well as relator),

Pl ainti f fs-AppeI lees

vs

GENTRY CROWELL, Secretary of State

of the State of Tennessee, LAMAR

ALEXANDER, covernor of the State

of Tennessee; WILLIA!, M. LEECH, JR.,

Attorney General of the Staee of

Tennessee, DAVID COLLINS, Coordinator

of Elections of the State of Tennessee;

and JAMES E. HARPSTER, JACK C. SEATON,

TOMIT'IY POI,JELL, RICHARD HOLCOMB, and

LYTLE LANDERS, Commissioner of the

State Board of Elections,

Por Publication

March 31, 1982

Davidson Eguity

Hon. Robert S. Brandt

Chancellor

t2

l3

De f endants-Appel I ant s

DISSENTING OPINION

We respectfully disagree $rith the majority's action

in remanding this case for further proof on two issues. The

record before us, even though mealJer, is sufficient to

support, beyond dispute, the finding that Acts of 1991,

Chapter 538, i.s unconstitutional. Nothing beyond redundancy

-1-

I9

t4

l5

t6

l7

l8

20

2t

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

I

I

I

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

t0

II

t2

I3

l4

15

t6

t7

l8

l9

20

2t

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

can result from a remand for the purpose of obt,aining an

adjudication that it is possible or it is not possible to

meet federal population eguality guldelines without crossing

county lines or that chapter 538 does or does not unlawfully

dilute minority voting strength. No combination of find-

i.ngs on those isgues would result in validating chapter 53g.

The majority opinion contains a ful1 and accurate

analysis of all the lega1 principles relevant to this law-

suit. We are in fuLl accord vrith all of the conclusions

reached except those that are said to support a remand

for trial and dissolution of the injunction.

we would hold chapter 538 unconstitutional because

this record shorys, beyond dispute, that the Legislature has

not restricted its breach of county lines to the minimurn

necessary to comply witl-r federal population requirements.

The parties have stipulated and exhj.bited in this record

a thirty-three member plan with a total- variance of 9.99t

with districts numbered consecut,ively, that crosses only

three county lines. That plan meets aI1 constitutional

requirements, state and federal, except that a portion of

Shelby, Davidson and Knox Counties are combined with

adjoining districts. It is beyond question that the pri-

mary problem in complying with the equal population and the

county line mandates is the fact that the populations of

the four metropolitan counties are not exact rnultiples of

139,114. It follows that if it i-s impossible to draw a

thirty-three member plan that meets the equal population

mandate $rithout splitting counties, the minimum county

line violations would be obtained by combining with adjoj-ning

-2-

I counties an area of the metropolitan counties with the

largest fractional results obtained by divi.ding 139,1I4

into the total county population. That is exactly what the

thirty-three member, three split, county plan accomplishes.

the majority opinion holds that the Tennessee

county line mandate is secondary to equal protection

requirements, but cannot be breached beyond the extent

necessary to comply with the federal equal population

guidelines. That principle was implicitly if not explicitly

applied in Smith v. Craddick, 471 s.I,i.2d 375 (Tenn.I971),

and it is supported by unassailable reason and logic.

It was also sanctioned in Sul1j-van v. Crowell, 444 Feil.Supp.

606 at 514-

The State insists that it is impossible to comply

with the Federal Constitution as interpreted by Federal

Courts wit,hout, crossing county lines and the State relies

on Frank Hinton's affidavit of February 11, 1982, as

proof that a variance of 22X is the mlnimum obtainable,

without breaching a single county line. Hinton's

affidavit shows that Knox, Davidson and Shelby Counties

produce a variance of +14.898, +14.48E and +I1.718

respectively, from optimum district size, and that some

of the multi-county districts will have a negative variance

of approximately 7E, resulting in the gross variance

of 22*. As the majority opinion points out, the plaintiffs

concede the accuracy of Hinton's affidavit. Plaintiffs'

concession as to the accuracy of that affidavit establishes

as the Iaw of this case, that Federal population guidelines

cannot be met without crossing some county lines and Points

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

l0

ll

t2

l3

l4

I5

l6

t7

l8

t9

20

2t

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

I

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

l0

il

t2

l3

t4

t5

t6

17

t8

l9

2{

zl

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

clearly to the necessity of crossing three of the four metro-

politan county lines, Yet, the effect of the remand is

to take proof and determine the issue of whether there is

an unavoidable conflict between the.state county line

mandatd and the Federal equal protection requirements.

Upon establishing, as this record does, that

county lines must be breached to meet federaL poputation

requirements, the determinatj_ve issue of the constitu-

tionality of chapter 538 is rvhether or not the state has made

an honest and good faith effort to construct districts

breaching as few county lines as practicle to comply with

federal population guidelines. The thirty-three member

plan breaching only three county lines conclusively

answers that question in the negative. Thus, the conclusi.on

is inescapable that chapter 538 cannot meet the test of

minimum violation of the state constitution and iro finding

on remand can change or alter that result.

We fu11y agree with all that the majority has

said about avoiding unlawful dilution of minority voting

strength. What, we ask, will be the result of finding on

remand that chapter 538 was constitutional 0r unconstitutional,

in that respect? It seems clear to us that chapter 53g is

doomed and therefore its effect on minority voting strength

is moot. Such an inquiry, and judicial determination would

only be appropriate if all conceivable reapportj.onment

Plans that the Legislature might adopt rvould have an

identical effect on minority voting strength, a proposition

vre can judicially notice as fallacious.

-4-

I

2

3

I

5

6

7

8

9

IO

II

t2

l3

11

l5

t6

t7

t8

t9

20

2t

22

23

21

25

26

27

28

29

30

We agree that legislative reapportionment is

primarily a legtslative function and we.bslieve the

Iegislature wlll reapportion itself, conetltutionally

under the State guidelines in the maJority opinion and

the Pederal guldellnes, so wcII reviewed and s,,qluarLzed

thereln. we wourd tErmtnate thls rawsult vrith a Judgnnent

declaring chapter 538 unconst,itutional, enjoin the holding

of an electlon thereunder and give the Legislature the

opPortunity to accomplish that before the 1992 etections.

Ur. ilustice Brock concurs in this dissent.

:

a'

a

[,

g

t

I

i

I