Bivins v. Board of Public Education and Orphanage for Bibb County Brief for Plaintiffs-Appellants

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1973

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Bivins v. Board of Public Education and Orphanage for Bibb County Brief for Plaintiffs-Appellants, 1973. 57e1a0ec-c99a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/3a4622e9-5e52-4cf7-a9d3-627b7cc2e91e/bivins-v-board-of-public-education-and-orphanage-for-bibb-county-brief-for-plaintiffs-appellants. Accessed February 15, 2026.

Copied!

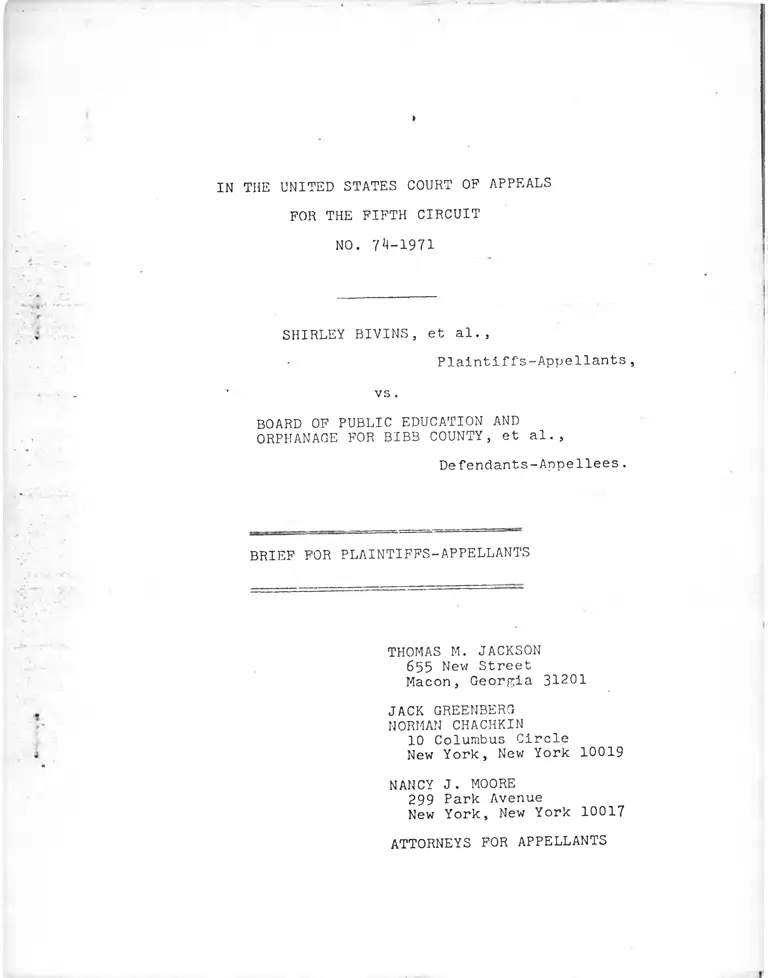

IN THE UNITED STATES COURT OP APPEALS

FOR THE FIFTH CIRCUIT

NO. 7*1-1971

SHIRLEY BIVINS, et al.,

Plaintiffs-Appellants,

v s .

BOARD OF PUBLIC EDUCATION AND ORPHANAGE FOR BIBB COUNTY, et al.,

Defendants-Appellees.

BRIEF FOR PLAINTIFFS-APPELLANTS

THOMAS M. JACKSON

655 New Street

Macon, Georgia 31201

JACK GREENBERG

NORMAN CHACHKIN10 Columbus Circle New York, New York 10019

NANCY J. MOORE 299 Park Avenue New York, New York 10017

ATTORNEYS FOR APPELLANTS

»

IN THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE FIFTH CIRCUIT

NO. 74-1971

SHIRLEY BIVINS, et al.,

Plaintiffs-Appellants,

v s .

BOARD OF PUBLIC EDUCATION AND -

ORPHANAGE FOR BIBB COUNTY, et al. ,

Defendants-Appellees.

Appeal from the United States District Court

for the Middle District of Georgia, Macon Division

CERTIFICATE REQUIRED BY LOCAL RULE 13(a)

The undersigned, counsel of record for the

plaintiffs Shirley Bivins, et al., certifies that the fol

lowing listed parties have an interest in the outcome of

this case. These representations are made in order that

the Judges of this Court may evaluate possible disquali

fication or recusal pursuant to Local Rule 13(a):

• - Vs* £ J» iV

i >i

1. The original plaintiffs who commenced this

action in 1963 include Shirley Bivins, James Bivins, Larry

Bivins and Franklin Bivins, minors, by Hester L. Bivins,

their mother and next friend; Solomon Bouie, Glory Ann

Bouie and Dorothy Mae Bouie, minors, by Rev. Willie R.

Bouie, their father and next friend; Joyce Dickey, minor,

by Rev. E. Grant Dickey, her father and next friend;

Helen Goodrum, Lela Goodrum, Thomas Goodrum, John Goodrum

and Jo Ann Goodrum, minors, by Thomas Goodrum, their

father and next friend; Patricia Ann Harper, minor, by

Abe Harper, her father and next friend; Charlie Bell

Williams, Sara Jeanette Williams and Tommie Lee Williams,

minors, by Mrs. Vada D. Harris, their mother and next

friend; Alice Marie Hart, minor, by Mrs. Willie Mae Hart,

her mother and next friend; Paul Hill, Jr., Clyne Hill,

Bernestine Hill and Lucie Mae Hudson, minors, by Inez

Hill, their mother and next friend; Carolyn Holston,

Melvin Holston, Lyre Holston, Maxine Holston, and Earnes-

tine Holston, minors, by Henry Holston, their father and

next friend; Solomon Hughes III, minor, by Solomon Hughes

Jr., his father and next friend; Billy Joe Lewis, Harold

Martin Lewis, Yvonne Dianne Lewis, Ray Charles Lewis and

Estella Marie Lewis, minors, by Ray Lewis, their father

2

*

and next friend; Merrit Johnson, Jr. and Pamela Sue

Johnson, minors, by Merrit Johnson, their father and

next friend; Willie Howard, Jr., Delores Howard and

Randolph Howard, minors, by Gertrude Howard, their mother

and next friend; Delmarie McDow, minor, by Wyatt J. McDow,

her father and next friend; Lois Farmer, Larry Stewart,

Maxine Stewart, Joe L. Stewart and Lolita Rutland, by

Dorothea Stewart, their mother and next friend.

2. The original plaintiffs above named com

menced and maintained this action pursuant to F.R. Civ. P.

23 on behalf of "all other Negro children and their parents

in Bibb County who are similarly situated."

3. The parties joined as plaintiffs and repre

sentatives of the original plaintiff class by the District

Court in its order of March 13, 197^> include Mr. and Mrs.

Julius C. Adams; Mr. Andrew Dillard; Mrs. Mary E. Deshazler;

Mrs. Minnie Seabrooks; Mrs. Jacquelyn Turner; Mr. Alfred

L. Sandlfer; Mrs. Lillian Nixon; Mrs. Jennie M. Harris;

Mr. and Mrs. Melvin Cheney; Mr. and Mrs. James Mays;

Mrs. Lucille Wells; Mr. and Mrs. Albert Hill; Mrs. Mary

C. Jones; Mrs. Thelma Bradley; Mr. and Mrs. Charles Blackmon;

Mrs. Grade Sandifer; Mrs. Irene Mallory; Mr. and Mrs.

Joseph Rodgers; Mr. and Mrs. J. C. Walker; Mr. Walter

Williams; Mrs. Lillie M. White.

3

The parties joined as plaintiffs and rep

resentatives of a new class of white elementary students

and their parents by the District Court in its order of

March 13, 1974, include Mr. and Mrs. Lee A. Adams;

Mrs. Gloria W. Harden; Mr. and Mrs. Tommy Joe Neyman;

Mrs. L. H. Matthews; Mr. and Mrs. Wilson Reich, Jr.;

Mr. and Mrs. Marvin P. Wilson; Mr. and Mrs. D. H. Ethridge;

Mrs. Margaret Paircloth; Mr. and Mrs'. George Crutchfiled;

Mr. and Mrs. Eddie Battle; Mr. and Mrs. W. R. Woodall;

Mr. and Mrs. C. J. Peacock, Jr.; Mr. and Mrs. J. D. Daniel;

Mr. and Mrs. Joseph B. Stanley; Mr. and Mrs. George R.

Small; Mr. and Mrs. John E. Avera; Mr. John B. Sheppard;

Mr. and Mrs. Glenn R. Wiseman; Mr. and Mrs. Roy G. Miller;

Mr. and Mrs. Blois C. Grissom; Mrs. Frances Blackburn;

Mr. and Mrs. Edward Moskaly; Mr. and Mrs. Hubert R. Moody;

Mr. and Mrs. Ernest L. Smith; Mr. and Mrs. D. F. Hidle;

Mr. William C. Mauder; Mr. W. Elliott Dunwody, III, Mr.

and Mrs. R. L. Merritt; Mr. and Mrs. Tommy C. Wood, Sr.;

Mrs. H. L. Land; Mrs. Linda Kay Bracewell; Mr. and Mrs.

Richard J. Story.

5. The defendants include Board of Public Edu

cation and Orphanage for Bibb County; F. Emory Greene;

R. Lanier Anderson, III; Bruce A. Hettel; William S.

Hutchings; Mrs. Sigfried Dayon; Dr. R. J. Martin; Mrs.

»

Dolores J. Cook; Larry G. Justice; Mayor Ronnie Thompson;

T. Louie Wood, Jr.; Grover C. Combs; Joseph E. Taylor;

Dr. L. Linton Deck, Jr.

6. The unsuccessful applicants for Interven

tion as plaintiffs and representatives of the original

plaintiff include Rev. Julius C. Hope, next friend of

Tonya Hope, minor; Ralph Wesley, next friend of Peggie

Wesley and Theresa Wesley, minors; Leonard Ussery, next

friend of Arleen Ussery, Carolyn Ussery, Jamie Ussery and

Leonard Ussery, Jr., minors; Matthew Hamilton, next

friend of Matthew Hamilton and Keith Hamilton, minors;

Mrs. Edna Rozier, next friend of David Rozier, minor;

Rev. A. F. Holloway, next friend of Arthur Holloway

and Faye Holloway, minors; Mrs. Annie Smart, next friend

of Charles Smart, Cornelius Smart and Camille Smart,

minors; Mrs. Betty Willis, next friend of Venessa Willis,

Vincent Willis and Victor Willis, minors; Rev. Cornelius

Demps, next friend of Beverly Ann Demps, Carolyn Marie

Demps, Keith Dwayne Demps and Lashelle Denice Demps,

minors; William Ellis, Jr., next friend of Valerie Ellis,

Theresa Ellis and Angela Ellis, minors; George Cornelius,

next friend of Anthony George Cornelius and Phillip Keith

Cornelius, minors; Mrs. Betty Henderson, next friend of

Alton Leon Henderson, minor; Edgar Harrison, next friend

5

t

of Dwayne Harrison, minor; Mrs. Marjorie Moore, next

friend of Carol Louise Moore, minor; Solomon Hughes,

next friend of Elaine Hughes, Pamela Renee Hughes,

Jerome Hughes, Michael Hughes, Derrick Hughes and Sheila

Faye Hughes, minors; Mrs. Hertha Mims, next friend of

Anthony C. Pitts, Cherlyne E. Pitts and Andrea Joel

Mims, minors; William C. Randall, next friend of Dav/n

Randall, Jeffrey Randall and Allison Randall, minors;

Mrs. Josephine May, next friend of Christan May, minor;

Mrs. Willie J. May, next friend of Reginald May, miner;

Mrs. Mary Horton, next friend of Angelia Horton and

Tommy Horton, minors; Ervin H. White, next friend of

Tony White and Liza White, minors; Arthur Stephens, next

friend of Lisa Stephens, Mark Stephens and Cherry Stephens,

minors; Mrs. Mary Harvey, next friend of Vanessa Harvey

and Agnes Harvey, minors.

/s/ Nancy J. Moore__________

Attorney of Record for Plaintiffs-Appellants.

6

»

I N D E X

Page

Table of Authorities............................ iii

Preliminary Statement.............................. 1

Issues Presented for Review. . .................... 3

Statement of Facts ................................ ^

History of the Case.......................... ^

Proceedings Since This Court's

Last Remand............................... 6

The Procedural Issues Raised Below............ 10

ARGUMENT —

I. The district court erred ir. holding

that the original named plaintiffs are no longer adequate representatives

of the plaintiff class................. 15

A. Once the court determined that the

suit could be maintained as a class action, the mooting of the claims

of most of the named plaintiffs did not render them inadequate repre

sentatives of the class............... 18

B. Assuming that the original named student-plaintiffs no longer enrolled

in the school system are not adequate class representatives, the remaining

plaintiff currently enrolled In the

system can properly represent the

entire class ........................ 22

1. Plaintiff Bivins' current

status as a high school

student does not render him an inadequate representative

of the entire class.............. 23

i

II.

III.

»

2. Applying established standards

for determining adequacy, plain

tiff Bivins is a proper repre

sentative of the class............

Assuming that the original named student-plaintiffs are no longer

adequate representatives of the class ,

the district court erred in joining additional court-selected black plain

tiffs and denying the motion of

petitioners to intervene ..............

A. The district court had no powerto order the random selection of

members of the class and to join

such randomly selected persons as

involuntary parties plaintiff........

B. If the original named student-

plaintiffs are no longer adequate

representatives of the class,

petitioners were entitled to inter

vene as a matter of right.............

C. Even if petitioners were not entitled to intervene as a matter of

right , and even if the court had the power to join randomly selected

class members as parties , the district court abused its discretion in denying petitioners* application

to intervene in favor of joining such randomly selected persons as parties and representatives of the

class..............................

The district court erred in joining

on its own initiative a class of white students and their parents as

parties to this action, whether as

plaintiffs or defendants..............

A. The district court had no power

to join, on its own initiative,

a class of white students and their parents as parties to this action. .

Page

26

29

32

38

40

47

48

ii

I

Page

B, Even if the district court had

the power to join a class of white

students and their parents asparties to this action, there was

no basis for ordering joinder at

this late stage of the litigation. . . 54

IV. The district court should be ordered

to comply with this Court's mandate

cf May 3, 1972, by immediately pass

ing on the merits of the three plans

before it at that time and ordering

the implementation of one of those

three plans before the 1974-1975

school t e r m ............................ 57

Conclusion...................................... ^

Table of Authorities

Cases:

Acree v. County Bd. of Educ., 458 F.2d 486 (5th

Cir.), cert, denied, 409 U.S. 1006 (1972) . .

Alexander v. Holmes County Bd. of Educ., 396

U.S. 19 (1 9 6 9)..............................

Barr̂ Rubber Products Co. v. Sun Rubber Co. ,425 F.2d 1114 (2d Cir. 1970). . . . . . . . .

Bivins v. Bibb County Bd. of Educ., 424 F.2d

97 (5th Cir. ................................

Bivins v. Bibb County Bd. of Educ., 460 F.2d

430 (5th Cir. 1972) ........................

Bivins v. Board of Public Educ. , 342 F.2d 229

(5th Cir. 1965) ............................

Boykins v. Fairfield Bd. of Educ. , 421 F.2d

1330 (5th Cir. 1970)...................... .

62

8 ,

55

4

6 ,

4

60

59

58

, 61

iii

1 PaRe

Brown v. Board of Educ., 446 F.2d 75 (5th Cir.

1971). ...................................... 6 0 , 61

Brown v. Gaston County Dyeing Machine Co.,

457 F. 2d 1377 (4th Cir.), cert, denied,

409 U.S. 982 (1972).......................... 18

Clark v. Board of Educ., 465 F.2d 1044 (8th

Cir. 1972), cert, denied, 413 U.S. 923

(1973) ...................................... 61

Coleman v. Humphreys County Memorial Hospitals,

55 F.R.D. 507 (N.D. Miss. 1972).............. 24, 25

Cooper v. Aaron, 358 U.S. 1 (1958).. . . . . . . . . 61

Crosby Steam, Gage & Valve Co. v. Manning,Maxwell & Moore, 51 F.Supp. 972 (D. Mass.

1 9 4 3 ) ................................ . . . . 55

Cypress v. Newport News Gen'l & Nonsectarian

Hospital Ass'n, 375 F.2d 648 (4th Cir.

1967)........................................ 18

Dolgow v. Anderson, 43 F.R.D. 472 (E.D.N.Y. 1968) . 41

Eisen v. Carlisle & Jacquelin, 391 F.2d 555

(2d Cir. 1968) .............................. 46

English v. Seaboard Coast Line R.R. Co.,

465 F.2d 43 (5th Cir. 1972).................. 49, 50

Fair Housing Development Fund Corp. v. Burke,55 F.R.D. 414 (E.D.N.Y. 1972)................

Gatling v. Butler, 52 F.R.D. 389 (D. Conn. 1971). • 19

General Time Investment Co. of Conn. v. Ackerman,

37 F.R.D. 38 (S.D.N.Y. 1964) ................ 35

Hatton v. County Bd. of Educ., 422 F.2d 457

(6th Cir. 1970). . . ........................ 50, 51, 56

Jenkins v. United Gas Corp., 400 F.2d 28

(5th Cir. 1968).................. . 23, 25

iv

I

»

Johnson v. Georgia Highway Express, Inc.,

417 P.2d 1122 (5th Cir. 1969)..............

Joseph v. House, 353 F.Supp. 367 (E.D. Va. 1973).

Kelley v. Metropolitan County Bd. of Educ.,463 P•2d 732 (6th Cir.), cert, denied,

409 U.S. 1001 (1972) ......................

Kelly v. Wyman, 294 F.Supp. 887 (S.D.N.Y. 1968) .

Lamb v. Hamblin, 57 F.R.D. 58 (D. Minn. 1972) . .

Martin v. Kalvar Corp. , 4ll F.2d 552 (5th Cir.

1969) ....................................

McSwain v. County Bd. of Educ., 1 8 F.Supp.

570 (E.D. Tenn. 1956)......................

Mersay v. First Republic Corp., 43 F.R.D. 465

(S.D.N.Y. 1968)...................... . . .

Moore v. Tangipahoa Parish School Bd., 298

F.Supp. 288 (E.D. La. 1969)................

Moss v. The Lane Co., 50 F.R.D. 122 (W.D. Va.

1970) . . . ...............................

Moss v. The Lane Co., 471 F.2d 853 (4th Cir.

1973).............. ........................

Nuesse v. Camp, 385 F.2d 694 (D.C. Cir. 1 9 6 7) • •

Peterson v. United States, 4l F.R.D. 131

(D. Minn. 1966)............................

Potts v. Flax, 313 F•2d 284 (5th Cir. 1963) . . •

Rackley v. Board of Trustees, 310 F.2d 141

(4th Cir. 1962)............................

Reyes v. Missouri-Kansas-Texas R.R. Co.,

53 F.R.D. 293 (D. Kan. .1971)..............

Schutten v. Shell Oil Co., 421 F.2d 869

(5th Cir. 1969)............................

Page

2 3 , 26

55

1 8 , 19, 20

18

19

51

18

4l

41, 5 0 , 51

28

19

51

52

22

25

19

33, 54

v

»

Page

Singleton v. Jackson Municipal Separate School

Dist., 419 F.2d 1211, 1222 (5th Cir. 1969), rev'd in part sub nom. Carter v. West

Feliciana Parish School Bd., 396 U.S.

290 (1970)..................................

St. Helena Parish School Bd. v. Hall, 287 F.2d

376 (5th Cir.), cert, denied, 368 U.S.

830 (1 9 6 1).......... .. . . "................

Sullivan v, Houston Independent School Dist.,

307 F.Supp. 1328 (S.D. Tex. 1969) ..........

Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Bd. of Educ.,

402 U.S. 1 (1971) ..........................

Thomas v. Clarke, 54 F.R.D. 245 (D. Minn. 1971). •

1

United States v. Board of School Comm'rs,

466 F.2d 573 (7th Cir. 1972), cert, denied,

410 U.S. 909 (1973) ........................

United States v. Jefferson County Bd. of Educ.,

372 F.2d 836 (5th Cir. 1966) , aff'd on

rehearing en banc, 380 F.2d 385 (5th Cir.),

cert, denied sub nom., Caddo Parish School

Bti. vT United States, 389 U.S. 840 (1967) • •

United States v. Texas Educ. Agency, 467 F .2d

848 (5th Cir. 1972)........ ................

Vaughan v. Bower, 313 F.Supp. 37 (D. Ariz.),aff’d, 400 U.S. 884 (1970)..................

Wymelenberg v. Syman, 54 F.R.D. 198 (E.D. Wise.

1972) ......................................

Statutes and Rules:

F.R. Civ.

F.R. Civ.

7, 15

50

28

4, 61, 62

19

50, 51, 56

22

7

18

19, 21

F.R. Civ. P. 20

vi

34, 49

34, 35, 49

35, 53

»

P,R. Civ. P. 21

Page

34, 48

F.R. Civ. P. 23.................................. 32

F.R. Civ. P. 24.................................. 34, 38

Other Authorities:

Advisory Committee's Note: "Proposed Amendments

to Rules of Civil Procedure for the United States

District Courts," 39 F.R.D. 69 (1966). . . . . .

3A Moore Federal Practice (2d Ed. 1974)..........

3B Moore Federal Practice (2d Ed. 1974)..........

7 Wright & Miller, Federal Practice and

Procedure (1970) ..............................

32, 38, 50

35

33, 36, 41

33, 34, 35

54, 55

vii

IN THE UNITED STATES COURT OP APPEALS

FOR THE FIFTH CIRCUIT

NO. 74-1971

SHIRLEY BIVINS, et al.,

Plaintiffs-Appellants,

vs.

BOARD OF PUBLIC EDUCATION AND

ORPHANAGE FOR BIBB COUNTY, et al.,

Defendants-Appellees.

Appeal from the United States District Court

for the Middle District of Georgia, Macon Division

BRIEF FOR PLAINTIFFS-APPELLANTS

PRELIMINARY STATEMENT

This action was initially filed in August 1963

in the Middle District of Georgia, Macon Division, by

fifteen black adult citizens of Bibb County and their 45

minor children enrolled in the Bibb County school system.

It sought to enjoin the defendant Board of Public Educa

tion and Orphanage for Bibb County (the "Board") from con

tinuing to operate and maintain a dual school system

based on race. On October 26, 1973, in response to a

)

motion filed by the Board, the district court entered an

order ruling that because all but one of the original

student-plaintiffs are no longer enrolled in the public

schools, as a result of graduations and otherwise, plain

tiffs are no longer adequate representatives of the class.

The court also directed the Board to use a computer to make

a random selection of members of the class and announced

its intention to join such randomly selected members as

parties plaintiff and class representatives. In addition,

the district court, sua sponte, announced its Intention to

join as parties and representatives of a class white stu

dents and their parents, to be selected in the same manner

as the proposed new black plaintiffs. Shortly thereafter

petitioners Hope et al., members of the plaintiff class,

filed an application to Intervene and serve as represen

tatives of the class. On the same day plaintiffs filed a

motion requesting that the district court grant petitioners’

application to intervene and reconsider and vacate its

order of October 26, 1973* On March 13> 197^ the dis

trict court entered an order denying petitioners appli

cation to intervene and plaintiffs' motion to reconsider

and vacate the order of October 26, 1973. In a second

order entered the same day, the court also added the compu

ter-selected parties as representatives of the class of

2

>

black elementary students and their parents, and as rep

resentatives of a new class of white students and their

parents. This brief is submitted in support of plain

tiffs' appeal from such orders.

ISSUES PRESENTED FOR REVIEW

1. Did the district court err in holding that the origi

nal plaintiffs are no longer adequate representatives of

the class because all but one of the original student-

plaintiffs are no longer enrolled in the public schools

as a result of graduations and otherwise?

2. Assuming that the original plaintiffs are no longer

adequate representatives of the class, did the district

court err in denying the petitioners' application to in

tervene in favor of joining as parties plaintiff and

representatives of the class randomly—selected members

of the class?

3. Did the district court err in Joining, sua sponte,

randomly selected white students and their parents as

parties plaintiff and representatives of a class in a

suit which has been pending more than ten years insti

tuted by black students and their parents to desegregate

the public schools?

3

I

M. Should the district court be ordered to comply with

the mandate of this Court issued May 3s 1972 by immediately

passing on the merits of plans then before it and ordering

the implementation of one of such plans before the commence

ment of the next school term?

STATEMENT OF FACTS

History of the Case

This school desegregation suit was initially

filed as a class action in August, 1963. At that time,

the Board admittedly was operating and maintaining a com

pulsory biracial school system perpetuated through the

use of dual school zones based on race. See Bivins v.

Board of Public Educ., 3^2 F.2d 229, 230 (5th Cir. 1965).

The case has been before this Court on numerous

occasions. Most recently, in May 1972, this Court decided

an appeal from the district court's action on remand from

1/an earlier Fifth Circuit ruling. The district court had

entered an order approving a plan of desegregation proposed

by the Board, over the objection of plaintiffs, shortly

before the Supreme Court decided Swann v. Charlotte-

Mecklenburg Board of Education, A02 U.S. 1 (1971)> and com—

“ Bivins v. Bibb County Bd. of Educ., *424 F.2d 97 (5th

Cir. 1970). _

k

>

panion cases. Plaintiffs filed a motion for further re

lief in light of Swann, alleging that within the Bibb

County school system there continued to exist a substan

tial number of schools attended either entirely or pre-

dominantely by pupils of one race. In response to a

show-cause order issued by the district court, the Board

submitted a "sector-proximity" plan which was objectionable

to plaintiffs on the ground that it placed an unequal

burden on black students by closing black neighborhood

schools and by assigning black students outside their

residential neighborhoods on a disproportionate basis.

Plaintiffs contended that a "sector-bumping" plan previous

ly submitted more equally distributed the burden of de

segregation among black and white children.

At an evidentiary hearing the district court,

without hearing argument, read Its memorandum opinion

from the bench in which it refused to consider the merits

of the plans presently before it. The court held that

implementation by the Board of its prior remand order

converted the Bibb County school system into a unitary

system and that additional busing would be "unreasonable,

impractical and unwarranted". Pursuant to such opinion,

an order denying plaintiffs' motion for further relief

was entered.

5

I

On appeal, this Court held that the district

court erred in failing to pass upon the relative merits

of the plans presented to it, ruling (1) that its prior

order of February 5, 1970 was designed merely to expe

dite the disestablishment of the dual school system in

Bibb County, and (2) that the Supreme Court decision in

Swann required school authorities and the courts to make

every effort to eliminate or minimize one-race schools.

Bivins v. Bibb County Bd. of Educ., 460 F.2d *130, *432—33

(5th Cir. 1972). The opinion concluded:

Upon remand, the district court should con

sider the relative merits of the plans submitted

by the parties designed to eliminate or minimize

the number of one-race elementary schools in

Bibb Co. and should frame his order with that in

objective - compliance with Swann - beai'lng in

mind that the burdens of closed schools and being

bussed should not fall unequally on the minority

race. . . .

The judgment of the district court is reversed and

the cause is remanded for further proceedings not

inconsistent with this opinion. 460 F.2d at *4 33 -

Proceedings Since This Court’s Last Remand

On remand, the district judge ordered the Board

to proceed with "deliberate speed" to formulate a plan

for the desegregation of the Bibb County elementary schools

2/ An acceptable plan of secondary school desegregation

is in effect in Bibb County.

6

I

in compliance with the May 3, 1972 order of this Court

3/and Swann. (See R. 26.) On January 11, 1973, the Board

filed a "Supplementary Response of Defendants" in which it

informed the court that it could not recommend any one

of the three updated plans then before the court, on the

grounds that all three plans would necessitate increased

transportation of students requiring more funds than were

currently available, that all three plans would have an

extremely disruptive effect on the educational process,

that none of the plans would receive the support of the

community, md that the decision of this Court in United

States v. Texas Educ. Agency, 467 F.2d 848 (5th Cir. 1972)

mitigated against the adoption of the plans. (See R. 26-

27.) The Board requested the district court to approve

its recommendation that none of the three plans be adopted

and to make findings identifying the schools which are

segregated as the result of discrimination in accordance

with the Texas Education Agency decision. (See R. 14.)

The district court denied the request of the

Board, and on February 28, 1973, entered an order again

directing the Board to submit recommendations. (R. 14.)

3/

Citations are to the reproduced Record on Appeal in

this matter. See Singleton v. Jackson Municipal Separate School Dlst. , TO" F.2d 1211, 1222 (5th Cir. 1 9 6 9).

7

»

On May 1, 1973, the Board submitted a "New Plan" which

proposed. Inter alia, that the elementary students "con

tinue to attend schools located In the geographic zones

where they live", that no child "be bussed involuntarily

to a school outside his or her zone", and that "[f]or

the 1973-7^ school year, at least, all existing elementary

schools will continue in operation" with the possible ex

ception of one school. (R. 17.) In a motion filed

May 2*J, 1973, plaintiffs objected to this plan on the

grounds that it totally disregarded plaintiff's right to

immediate relief, failed to comply with the May 3, 1972

mandate of this Court, and ignored this Court's reliance

on Swann and Alexander v. Holmes County Bd. of Educ. ,

396 U.S. 19 (1969), by failing to eliminate immediately

the vestiges of the dual system reflected in the numer

ous racially identifiable schools left untouched. (R. 29-

30.) Plaintiffs further objected to the Board's refusal

to recommend for adoption any of the three plans previous

ly submitted, contending that none of the Board's objec

tions provided a constitutional basis for the continued

existence of racially identifiable schools. (R. 30-^1.)

Following a hearing held on July 27, 1973, the

district court yet again directed the Board to file, on

or before August 17, 1973, a definitive plan for the further

8

I

desegregation of the elementary schools. (See R. 8 7 .)

In response, the Board submitted the "Trotter Plan".

This plan, like previous plans submitted by the Board,

assigns pupils to schools on the basis of residence, re

jects the use of busing to achieve maximum desegregation,

and leaves untouched a substantial number of racially

identifiable schools. (R. 40, 43-46.)

Despite this Court's order of May 3, 1972 that

the district court immediately consider the relative

merits of the updated plans then before it, there have

been no prcceedings in the district court with respect

to the merits of this case since the submission of the

"Trotter Plan" in August 1973- Two years have elapsed

since this Court's mandate issued, yet the district

court has failed to order the implementation of a plan

to desegregate the elementary schools of Bibb County.

Rather, the only order of any consequence entered by the

district judge since May 3, 1972, the order from which

this appeal is taken, will not expedite a decision on the

merits but will further delay the substantive proceedings

through an unnecessary and unwarranted interference with

the structure of the parties to this litigation.

9

1

»

The Procedural Issues Raised Below

On May 24, 1973, shortly after it had announced

that it would not recommend any of the plans before the

court, the Board filed a "Motion by Defendants for Order

Adding Additional Parties as Plaintiffs and Defendants .

The motion requested the district court, inter alia, to add

additional parties plaintiff, alleging that as a result

of graduations and otherwise, almost all of the original

named student-plaintiffs are no longer enrolled in the

school system. (R. 22.) ^

Plaintiffs objected to the Board’s proposal on

the grounds (1) that a class action, such as this, which

alleges continuous constitutional violations should not

become moot because of years of delay— attributable in

large part to the Board itself— which occasioned the grad

uation of most of the original named students; and (2)

that the motion was untimely because it was made subse

quent to the mandate of this Court ordering the district

court immediately to consider the relative merits of

"Motion to Dismiss Defendants' Motion to Add Parties

(R. 96).

10

1

5/plans presently before it. (R. 96-101.)

On October 26, 1973, the district court entered

an order granting the Board's motion. The court found

that none of the original named plaintiffs could ade

quately represent the class, because all but one of the

original named student-plaintiffs are no longer enrolled

in the public schools and because the one remaining plain

tiff is not enrolled in the elementary schools, and that

it was the "duty" of the court to "fashion a procedure

to select from the plaintiff class representative parties

who will fairly and adequately protect the interests of

the plaintiff class". (R. 105-106.) In addition, the

court sua sponte determined that it was necessary to add

a class of white students and parents as additional parties

defendant, on the ground that the Board "should no longer

5/ At a hearing held on October 24, 1973, plaintiffs

further objected to the motion, claiming that no useful

purpose would be served by redetermining the issue of

class representation at this stage of the litigation

and that the motion was a "diversive tactic" on the part of the Board designed to turn the district court's at

tention away from what should have been its paramount concern: the immediate implementation of a plan toeliminate all vestiges of the dual school system in

Bibb County. R. 128-129. Plaintiffs also suggested

that any alleged inadequacy in the representation of

the class could be satisfied by voluntary intervention,

pursuant to notice sent by the court to the members of

the class. R. 147.

11

»

be expected to be the advocate of the interests of the

white students and parents" but instead should be "freed

of the assumptions of the past and placed in a position

to impartially operate the public schools of this county

for the benefit of all the students and parents of Bibb

County". (R. 104.)

The court proceeded to fashion the following

procedure for selection of the additional parties: (1)

each class (white and black) was to be represented by at

least one student from each elementary school and that

student's parents; (2) the total number of representa

tives from each school should be in proportion to the total

number of students of each race now enrolled in each school;

(3) the Board was directed to use its computer facilities

to make a random selection of black and white students from

each school and to supply the court with names and addresses

(4) following the receipt of such names and addresses, the

court would communicate with each student and parent to

determine whether each was willing to be a representative

of his particular class. (R. 106-107.) The court further

noted its "expectation" that plaintiffs' present lawyer,

Thomas M. Jackson, Esq., would continue to represent the

6/plaintiff class. (R. 107.)— The Board produced the com

puter listings and the district judge, at separate meetings

6/ Later the court noted that the new plaintiffs could

"fire" Mr. Jackson at any time. R. 198.

12

I

held with black and white parents on December 11 and 12,

1973, informed these parents that unless they notified

the court of their unwillingness to serve as class repre

sentatives, they would be added as parties to the litiga

tion. (R. 179, 206.)

On December 28, 1973, petitioners Hope, et al.

filed an application to intervene as plaintiffs, and to

serve as representatives of the class of plaintiffs which

the district court by its order of October 26, 1973 de

clared was inadequately represented. Petitioners alleged

that they are black citizens and residents of Bibb County,

Georgia, that they have children presently enrolled in one

or more of the Bibb County elementary schools, and that

all are subject to the Jurisdiction of the court; that

they are members of the plaintiff class, have interests

to protect in the litigation, and can adequately represent

the class. (R. 159-16^.)

On the same day, the original plaintiffs filed

a "Motion to Reconsider Order of October 26, 1973, and to

Vacate Same and to Order a Plan for Further Desegregation",

requesting that the district court grant petitioners'

application to intervene and reconsider and vacate its

order establishing a computer selection process for new

plaintiffs, since the addition of court-appointed parties

13

would no longer be necessary or desirable. (R. 165-)~~

On March 13, 197*1, the district court entered

an order denying petitioners' application to intervene

and plaintiffs' motion to reconsider and vacate the

order of October 26, 1973. In a second order entered

the same day, the court also added the computer-selected

parties as representatives of the class of black ele

mentary students and their parents, and as representatives

of a new class of white students and their parents.

8 /(R. 217-20.)

Plaintiffs timely noticed aheir appeal from

such orders.

Plaintiffs also requested that the court not add a

class of white parents as parties, since white parents

and students have neither the constitutional right to

oppose desegregation nor the power or authority to formu

late and implement a desegregation plan for the school

system. R. 168-69-

8/ At this time the court amended its order of October

2 8 , 1973, which added the class of white parents and students as parties defendant, to add them as parties

plaintiff.

I

ARGUMENT

I. THE DISTRICT COURT ERRED IN HOLD

ING THAT THE ORIGINAL NAMED PLAIN

TIFFS ARE NO LONGER ADEQUATE REPRE-

SENTATIVES OF THE PLAINTIFF CLASS.

On August 14, 1963, fifteen black adult citi-

zents of Bibb County and their 45 minor children enrolled

In the Bibb County School System filed this action on be

half of themselves and "on behalf of all other Negro

children and their parents in Bibb County who are simi

larly situated and affected," against the defendant Board

of Public Education of Bibb County, Georgia, its indi

vidual members and its Superintendent, to enjoin them

"from continuing their policy, practice, custom and usage

of operating a dual school system in Bibb County, Georgia

based wholly on the race and color of the children attend

ing schools in said county". (R. 102.) Since the filing

of the original complaint, there have been numerous pro-

t

ceedings in the district court, many of which have been

reviewed by this Court, and, on one occasion, by the

United States Supreme Court.2/ On May 3, 1972, this

9/ Reported opinions in this case include 342 F.2d 229

(5th Cir. 1 9 6 5); 284 F. Supp. 888 (M.D. Ga. 1967); 419 F.2d 1211 (5th Cir. 1969), rev1d in part sub nom. Carter

v. West Feliciana Parish School Bd. ,* 396 U.S. 290 (1970);

331 F. Su p p . 9 (M.D. Ga. 1971), re'v'd, 460 F.2d 430 (5th

Cir. 1972).

15

»

Court issued a mandate to the district court to consider

the relative merits of plans which had been submitted

to it, in order to "eliminate or minimize the existence

of one-race elementary schools in Bibb County," and to

frame a decree "with that objective— compliance with

Swann— in mind". *160 F.2d at *4 33 -

IJow, more than ten years since the initial fil

ing of this action and two years since the issuance of

the mandate from this Court directing the district court

to consider and implement a plan of desegregation in com

pliance wi'.h Swann, the defendant Board has yet to ful

fill its constitutional duty to immediately eliminate the

vestiges of its dual system reflected in the numerous

racially identifiable elementary schools. Instead, the

Board has repudiated previously submitted plans, on the

clearly unacceptable grounds that such plans necessitated

the use of busing and might therefore be unpopular in the

community, and it has submitted two new plans which fail

either to eliminate or justify the continued existence of

numerous racially identifiable elementary schools, as re

quired by Swann. In addition, the Board has interjected

into this action totally unwarranted and unnecessary pro

ceedings with respect to the adequacy of representation

by the existing plaintiffs in this litigation, the sole

16

I

effect of which has been and will continue to be to dis

rupt the proceedings on the merits and to further delay

the elimination of continuous constitutional violations

by the Board.

Since the filing of the complaint in this ac

tion, it is not surprising that most of the *)5 original

named student-plaintiss have either been graduated or

are otherwise no longer enrolled in.the Bibb County School

System. However, one original named plaintiff (Larry

Bivins) is still enrolled, as a high school senior.

(R. 102.) Plaintiffs submit that even if all the origi

nal named plaintiffs were no longer enrolled in the school

system they would still be adequate class representatives

and, in any event, the student-plaintiff who is in fact

presently enrolled in the school system can adequately

represent the class without the addition of court-ap

pointed parties.

17

A. ONCE THE COURT DETERMINED THAT

THE SUIT COULD BE MAINTAINED AS

A CLASS ACTION, THE MOOTING OF

THE CLAIMS OF MOST OF THE NAMED

PLAINTIFFS DID NOT RENDER THEM INADEQUATE REPRESENTATIVES OF

THE CLASS.__________________

It is well-settled, as both the Board and the

district court concede, that the mooting of the claim

of a named representative does not moot the claims of

the remaining members of the class. See , e.g. , Kelley __v.

Metropolitan County Bd, of Educ., 463 F.2d 732, 743

(6th Cir.), cert, denied, 409 U. S, 1001 (1972); Brown_v.

Gaston County Dyeing Machine Co., 457 F.2d 1377, 1380

(4th Cir.), cert. denied, 409 U.S. 982 (1972); Cypress _v .

Newport News Gen'l & Nonsectarian Hospital Ass'n, 375 F.2d

648 (4th Cir. 1967); Vaughan v. Bower, 313 F. Supp. 37,

40 (D. Ariz.), aff'd, 400 U.S. 884 (1970); Kelly v. Wyman,

294 F. Supp. 887, 890 (S.D.N.Y. 1968); McSwaln v. County

Bd. of Educ., 138 F. Supp. 570 (E.D. Tenn. 1956). This

is particularly true in a school desegregation case,

which involves continuing constitutional violations and

in which the delay in reaching a decision on the merits is

in great part, attributable to the defendant Board itself.

10/ R. 124, 134.

18

)

Kelley v. Metropolitan County Bd. of Educ., supra, 463

F.2d at 743. Were this not the case, the Board would

Improperly benefit from Its own wrongful conduct. See

Reyes v. Mlssourl--Kansas-Texas R.R. Co., 53 F.R.D. 293,

298 (D. Kan. 1971).

While the Board and the district court concede

that this action is not moot with respect to the members

of the plaintiff class still enrolled in the public

schools, it is their contention that because nearly all

of the original named student plaintiffs are no longer

enrolled in such schools they cannot adequately represent

the class. However, once it has been determined that a

suit may proceed as a class action, the mooting of the

claim of the named party does not render him or her an

inadequate representative of the class. See Moss v. The

Lane Co. , Inc. , 471 F.2d 853, 855 (4th Cir. 1973); Wymelen-

berg v. Syroan, 54 F.R.D. 198, 200 (E.D. Wis. 1972); Lamb

v. Hamblin, 57 F.R.D. 58 (D. Minn. 1972); Thomas v. Clarke,

54 F.R.D. 245, 252 (D. Minn. 1971); Gatling v. Butler, 52

F.R.D. 389, 394-95 (D. Conn. 1971).— /

11/

Moreover, in those cases in which it was held that the

mooting of the claims of the named parties did not warrant

dismissal of the action, the implication was clear that

the named plaintiffs could continue to act as representa

tives for the class. See Kelley and other cases cited in text, supra.

19

I

The rationale for allowing persons whose claims

have become moot to continue to represent the claims of

the members of the class is to avoid the inevitable delay

which would be occasioned if a court were forced to con

tinually redetermine the adequacy of representation in

a class action. This is of particular importance when,

as in the present case, because of the lengthy history

of litigation, continuous redetermination is not only

impractical but also works an injustice on the members

of the class by delaying a decision on the merits. Thus,

the Sixth Circuit’s opinion in Kell ay, supra, adopting

that of the district judge, stated:

This Court does not feel once a class

action has been adjudicated and the action of

the trial court has been reviewed by the Court

of Appeals, that it is necessary or proper to

continue to redetermine the standing of the

plaintiffs to represent a class. The United

States Supreme Court in its order implementing

the amendment to Rule 23 states:

”. . . the foregoing amendments and

additions to the Rules of Civil Pro

cedure shall take effect on July 1,

1966, and shall govern all proceed

ings in actions then pending except to the extent that in the opinion of

the Court their application in a par

ticular action then pending would not

be feasible or would work injustice in which event the former procedure

applies."

This clearly indicates an intent that there should

not be a continuous readjudication of this question

20

1

I

in cases where there has been a lengthy history of

litigation, both in the district and the appellate

courts. Frankly, this Court feels that it is not

feasible or practical to have continuous adjudica

tion of such items. 463 F.2d at 750.

So long as the named plaintiffs' current status does not

create interests antagonistic to those of the class and

so long as plaintiffs' counsel is competently and vigor

ously pursuing the interests of the class, the named

plaintiffs continue adequately to represent the class.

Wymelenberg v. Syman, supra, 54 F.R.D. at 200.

Here there is nothing antagonistic in the named

plaintiffs' status as graduates of the public school

system, and the competency and vigor of representation

by plaintiffs' counsel has been expressly recognized by

the district court. (R. 107.) Thus the court below

clearly erred in holding that the fact that most of the

original named student-plaintiffs are no longer enrolled

in the public schools renders them inadequate representa

tives of the plaintiff class.

21

B. ASSUMING THAT THE ORIGINAL NAMED

STUDENT-PLAINTIFFS NO LONGER EN

ROLLED IN THE SCHOOL SYSTEM ARE

NOT ADEQUATE CLASS REPRESENTATIVES,

THE REMAINING PLAINTIFF CURRENTLY

ENROLLED IN THE SYSTEM CAN PROPER

LY REPRESENT THE ENTIRE CLASS.

The district court held that one of the origi

nal plaintiffs, Larry Bivins, who is currently a high

school senior, is not an adequate representative of the

class on the ground that he has no direct interest in

the operation of the elementary schools in Bibb County,

the remaining area of dispute in this litigation. Plain

tiffs submit that the district court erred in so holding

and that, upon proper application of the standards announced

by this Court with respect to adequate representation, it

is clear that plaintiff Bivins can adequately represent

the interests of the class without the joinder of court-

12/appointed parties.

12/

Any other determination would in fact conflict with the long-settled principle of this Circuit that minor plaintiffs in school desegregation cases are entitled

to decrees having school system-wide effect. Potts v.

Flax, 313 F.2d 2o4 (5th Cir. 1963); United States v. Jefferson County Bd. of Educ., 372 F.~2d 8 3 6 , 864-70

(5th Cir. 1 9 6 6) , aff'd on rehearing en banc, 380 F.2d

385 (5th Cir.), cert, denied sub nom. Caddo Parish School

Bd. v. United States , 389 U. S7HJ4(TTl9577T

22

>

1. Plaintiff Bivins' Current Status

as a High School Student does not Render

Him an Inadequate Representative of the

Entire Class._____ ___________— --------

As this Court has consistently held, in an ac

tion to enjoin racially discriminatory policies and prac

tices, a single plaintiff affected by such discriminatory

policies and practices may represent all persons so af

fected, regardless of the particular area of discrimina

tion. Thus in the leading case of Jenkins v. United Gas

Corp. , MOO F.2d 28 (5th Cir. 1968), an employee who had

been denied a promotion was allowed to maintain a class

action on behalf of all past, present and future employees

in an action alleging plant-wide racial discrimination.

Simlarly, in Johnson v. Georgia Highway Express, Inc.,

H17 F .2d 1122 (5th Cir. 1969), a discharged employee was

allowed to represent a class consisting of "all other

similarly situated Negroes seeking equal employment op

portunities without discrimination on the grounds of race

or color" in an "across the board" attack on unequal em

ployment practices in the areas of hiring, firing, pro

motion, and maintenance of facilities. 417 F.2d at 1123-

24. There this Court stated, with respect to the differ

ent fact situations of different employees:

23

I

[T]he "Damoclean threat of a racially dis

criminatory policy hangs over the racial

class [and] is a question of fact common to

all members of the class." 417 F.2d at 1124.

In cases such as the present one involving pub

lic facilities and Institutions, the ability of a small

number of plaintiffs to represent all persons affected

by unconstitutional racially discriminatory policies and

practices, regardless of their particular contact with

the institutions, is of particular Importance. Thus, in

Coleman v. Humphreys County Memorial Hospitals, 55 F.R.D.

507, 510-11 (N.D. Miss. 1972), plaintiffs who had used

the waiting rooms and outpatient facilities of the defen

dant hospital were held to have standing to bring a class

action on behalf of all black residents and citizens of

the area served by the hospital to attack "all phases of

the institution's operations" including employment prac

tices and policies:

It is quite clear to the court that

in the area of public facilities and In

stitutions, such as schools, hospitals, li

braries and the like, where the facility or

institution is one maintained for the bene

fit of the general public, any member of a

race which is subjected to unlawful racially

discriminatory policies, and who has suffered

a deprivation of any rights, privileges, or

Immunities secured by the Constitution and

laws of the United States by reason- thereof,

has standing to bring a class action against

such facilities or institutions for the elimi-

24

I

nation of such discriminatory policies and to

attack all phases of the institution's opera

tions where such discriminatory practices

exist.

See also, Rackley v. Board of Trustees, 310 F.2d 1^1 (^th

Cir. 1962).

The failure of the defendant Board to eliminate

the vestiges of a dual system has been a discrimination

affecting all members of the class, including high school,

junior high school and elementary students. The fact

that at this late stage, the remaining critical area of

concern is the desegregation of the elementary schools,

does not render plaintiff Bivins (who was enrolled in the

elementary schools at the commencement of this litigation)

an inadequate representative of the class.

Even if Bivins' claims as to elementary schools

are considered mooted, this does not render him an inade

quate representative of the class. Thus, in Jenkins— v.

United Gas Corp., supra, this Court held that an employee

who had been offered and who had accepted a promotion sub

sequent to the filing of the action could continue to

represent the class. Similarly, in Coleman v._Humphreys

County Memorial Hospitals, supra, the court rejected the

contention of defendants that because they had remedied

the discriminatory treatment to which named plaintiffs

had been subjected, they had no standing to challenge the

25

»

defendant hospital’s'discriminatory employment practices

since none alleged that they had sought or obtained em

ployment with the hospital. The court held that plaintiffs

could continue to represent a class including "all black

residents of the area served by the hospital who have been

victims of the hospital's racially discriminatory policies.’

55 F.R.D. at 510.

2. Applying Established Standards

for Determining Adequacy, Plaintiff Bivinsis a Proper Representative of the Class.

In the leading case on adequacy of representation

i<n this Circuit, Johnson v. Georgia Highway Express, Inc., ,

supra, this Court announced the following standard to be

applied with respect to the plaintiffs' ability to protect

the interests of the class:

"An essential concomitant of adequate

representation is that the party's attorney

be qualified, experienced, and generally able

to conduct the proposed litigation. Addi

tionally, it is necessary to eliminate so far

as possible the likelihood that the litigants

are involved in a collusive suit or that plain

tiff has interests antagonistic to those of

the remainder of the class." ^17 F.2d at 1125.

As noted above, the competency and vigor of

representation of plaintiff's counsel in this action has

been expressly recognized by the district court. Seie p. 19,

supra.

26

I

With respect to the second criterion established

by Johnson, there has been no suggestion of collusion in

this action, nor could there be in view of the history

of this litigation.

Finally, there has been no suggestion that plain

tiff Bivins has interests antagonistic to those of the

remainder of the class, other than a vague assertion by

the Board that the "interests” of the members of the class

"vary widely” and "[t]here is no single point of view as

to what is the best way to desegregate the elementary

schools further in accordance with the Fifth Circuit man

date." (R. 13^-5.) Thus, while the Board concedes that

”it is technically possible for one or only a few persons

to represent a class", it argues that "the adequate repre

sentation of a class of this magnitude in a case of such

importance to all of the citizens of Bibb County requires

that a substantial number of additional named plaintiffs

be added as parties to this action." (R. 23.) However,

in an action seeking to eliminate constitutional violations

(applicable per se to a class), in which the very nature

of the right plaintiffs seek to vindicate requires that

the decree run to the benefit of all persons similarly

situated, the possibility that some members of the class

may disagree with the particular views expressed by the

27

J

I

plaintiff is irrelevant in considering whether or not the

plaintiff is an adequate representative of the class.

Thus, in Sullivan v. Houston Independent School Dlst.,

307 F. Supp. 1328 (S.D. Tex. 1969), the court stated:

Plaintiffs have designated a class com

posed of all the students presently enrolled

in the secondary schools of the Houston Inde

pendent School District. Defendants contend

that this designation is not proper under Rule 23 because the majority of Houston secon

dary students are not in sympathy with the views

or methods of these plaintiffs and are, therefore not 'similarly situated'. This contention

misses the point. All of the members of the

class are subject to the same regulations of the Houston School District which have been alleged

to be unconstitutional on their face. It is irrelevant to speculate how many students might

need to invoke the first amendment as protection

from official sanctions; the fact that each mem

ber is subject to the same specific sort of de

privation of constitutional rights as the repre

sentative parties is enough. This case is

clearly maintainable as a class action. . . .

307 F. Supp. at 1337-8.

See also Moss v. The Lane Co., Inc., 50 F.R.D. 122 (W.D.

Va. 1970). Thus the mere fact that some members of the

class may hold different views on the best way to further

desegregate the schools in Bibb County does not render

plaintiff an inadequate representative under Johnson.

Were this so, there could never be adequate representa

tion In a class action unless all of the members of a

class were in complete unanimity at every stage of the

litiation. Such was clearly not the intent of the framers

of Rule 23-

28

I

II. ASSUMING THAT THE ORIGINAL NAMED

STUDENT-PLAINTIFFS ARE NO LONGER

ADEQUATE REPRESENTATIVES OF THE

CLASS, THE DISTRICT COURT ERRED

IN JOINING ADDITIONAL COURT-SELEC

TED BLACK PLAINTIFFS AND DENYING

THE MOTION OF PETITIONER TO IN

TERVENE^_________________________

In its preliminary order of October 26, 1973

the district court, having found that the original named

plaintiffs were no longer adequate representatives of

the class, held that It was "the duty of the court to

fashion a procedure to select from the plaintiff class

representative parties who will fairly and adequately pro

tect the interests of the plaintiff class. (R. 106.)

The court then directed the Board, "using its computer

facilities, to make a random selection of the number of

Negro . . . students of each elementary school . . . and

to supply the court as soon as reasonably possible with

a list of the names and mailing addresses of those selec

ted and their parents." (R. 107.) The court then indi

cated Its intent, upon receipt of such list to "communi

cate with each student and his parents and determine

whether or not each will be willing to be a representa

tive of his particular class." (Ibid.)

Upon receipt of the list of computer-selected

students, the district judge convened a meeting of the

29

I

parents of such students, where the parents were informed

by the court that unless they affirmatively indicated

their desire not to become parties to the litigation,

they would automatically be joined as plaintiffs and

representatives of the class:

THE COURT: . . . I hope that each one

of you will discuss this with your husband or

your wife and your students (sic) and, in the

event you do not wish to participate, in the

next couple of days I wish you would telephone

our Clerk's Office. You remember at the bottom

of the letter we put the number of the Clerk's

Office, and just say "I was at the meeting but

I do not want to be involved." Now— if we— do not hear from you we are going to leave your

name upon the ' 1ist of those who are willing to

be Involved. CR- 179*) (Emphasisadded.)

On December 28, petitioners filed their appli

cation to intervene as parties plaintiff and to serve as

representatives of the plaintiff class, alleging that theyI

are black citizens and residents of Bibb County, that their

children are enrolled in the Bibb County public schools,

that they are members of the plaintiff class with inter

ests to protect in the litigation and that they can ade

quately protect the interests of the class. (S®J1 P* -̂3>

supra.)

March 13, 1974, the district court denied peti

tioners' application to intervene. Instead, having ex

cluded "a very small number of parents [who] advised that

30

they are unwilling to represent the children"of the pub- ''

lie schools of this county in this lawsuit” (R. 218), the

court added as parties and representatives of the plain

tiff class those randomly selected persons who had indi

cated by silence alone their willingness to join in the

litigation and serve as representatives.— ^

Plaintiffs' submit that this highly unorthodox

method of expanding the litigation through the addition

of court-appointed parties was beyond the power of the

court. Even assuming that the court had the power to

join such persons, once members of the class actively

sought to intervene in the action and act as representa

tives of the class, the district court erred in denying

their application in favor of the joinder of court-appointed

parties who at no time indicated by more than passive

silence their willingness either to join as parties or

to protect the Interests of the remaining members of the

class.

13/ The court also denied plaintiffs’ motion to reconsider

and vacate its October order that directed the Board to

randomly select members of the class to be joined as new

class representatives, which plaintiffs suggested would be appropriate once the court granted the petitioners’

motion to intervene (R. 168).

31

A. THE DISTRICT COURT HAD NO

POWER TO ORDER THE RANDOM

SELECTION OF MEMBERS OF THE

CLASS AND TO JOIN SUCH RAN

DOMLY SELECTED PERSONS AS IN-

VO LUNTARYPARTIESPLAINTIFF^

In Its order of October 26, 1973, the district

court cited Rule 23, Fed. R. Civ. P., as the source of its

authority to add as named representatives of the plain

tiff class, those randomly selected members who did not

expressly indicate their unwillingness to join. (R. 105.)

However, nowhere does Rule 23 expressly grant the district

judge the power to appoint as representatives members of

the class who have not soubht to intervene as parties.

Nor can such a grant of power be reasonably implied in

view of the legislative history of amended Rule 23, which

clearly indicates that the proper remedy to be applied

by the court when faced with the problem of inadequate

representation by the named plaintiffs is to condition

the maintenance of a class action on the intervention of

additional parties who can adequately protect the in

terests of the class:

An order embodying a determination [that

an action may be maintained as a class action]

can be conditional; the court may rule, for

example, that a class action may be maintained

only if the representation is improved through

Intervention of additional parties of a stated ̂

type. A determination once made can be altered

32

or amended before the decision on merits if, upon

fuller development of the facts, the original

determination appears unsound. A negative de

termination means that the action should be

stripped of its character as a class action.

See subdivision (d)(4). Although an action

thus becomes a nonclass action, the court may

still be receptive to interventions before the

decision on the merits so that the litigation may

cover as many interests as can be conveniently handled. [Advisory Committee's Note: "Proposed

Amendments to Rules of Civil Procedure for the

United States District Courts, 39 F.R.D. 69, 104

(1966).] (Emphasis added.)

As the Advisory Committee's Note clearly indicates, in the

absence of the intervention by persons who can adequately

represent the class, the court has no power to add parties

of its own volition, but rather is limited solely to con

ditioning the maintenance of the class action on the in

tervention of proper parties pursuant to Rule 23 (d)(3)

or dismissing the class action. See 3B Moore, Federal

Practice (2d Ed. 1974) H 23-73, PP- 23-1441 to 1443-

The procedure contemplated by the drafters of

amended Rule 23 is in accordance with the traditionally

limited role of the trial court in shaping the litigation.

Ordinarily, the plaintiff has the right "to decide who

shall be parties to a lawsuit", 7 Wright & Miller, Federal

Practice and Procedure (1970), § 1602 , p. 17- See_ also_

Schutten v. Shell Oil Co., 421 F.2d 8 6 9, 873 (5th Cir.

1969). In recognition of this fundamental proposition,

33

' the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure provide for only a

few limited exceptions when justice requires. Thus per

sons not already parties, who affirmatively seek to join

in the litigation, may intervene in certain situations

pursuant to Rule 24. When, as in the case at bar, the

defendant seeks to compel the joinder of persons not al

ready parties who have not sought to intervene, the au

thority of the court to compel such.joinder is governed

by Rules 17, 19 and 21.

Rule 21 provides in relevant part that:

Misjoinder of parties is not grounds for dis

missal of an action. Parties may be dropped

or added by order of the court on motion of

any party or of its own initiative at any

stage of the action and on such terms as are

j ust.

Its purpose is to provide a "mechanism for remedying either

the misjoinder or non-joinder of parties." 7 Wright and

Miller, supra, § 1683, p. 322. The rule does not delimit

the circumstances under which additional persons should

be made parties to the litigation, but "simply describes

the procedural consequences of failing to do so and makes

it clear that the defect can be correct." Id. at 324.

Any requirement that particular individuals be added to

an action must flow from Rule 17 (which provides that the

"action shall be prosecuted in the name of the real party

3̂

in interest” and is thus clearly inapplicable in the

present case) or from Rule 19, which provides for the

"Joinder of Persons Needed for Just Adjudication."

I VIbid.-

rtule 19(a) provides that a person is to be

joined if feasible if

(1) in his absence complete relief cannot be

accorded among those already parties, or

(2) he claims an interest relating to the

subject of the action and is so situated that

the disposition of the action in his absence

may (i) as a practical matter impair or im

pede his ability to protect that interest or

(ii) leave any of the persons already parties

subject to a substantial risk of incurring

double, multiple, or otherwise Inconsistent

obligations by reason of his claimed interest.

Such persons, termed "necessary" or "indispensable" parties,

must be joined if the action is to be continued unless

they are not subject to service or process or their joinder

I V Although Rule 20 provides that

[a]ll persons may Join in one action as

plaintiffs if they assert any right to relief jointly, severally, or in the al

ternative in respect of or arising out of

the same transaction, occurrence, or series

of transactions or occurrences and if any

question of law or fact common to all these

persons will arise in the action,

(emphasis added)

and thus members of the class in a class action may qualify for permissive joinder, such joinder would be

at their option and cannot be compelled by defendants.

See General Investment Co. of Conn, v. Ackerman, 37 F.R.D.

38, 41 (S.D.N.Y. 1964)'. See also 3A Moore, supra, 20.05,

p. 2774.

35

would deprive the court of subject matter jurisdiction.

See 3B Moore, supra, 11 19.02.

Members of the class in a suit which has been

determined to be a valid class action pursuant to Rule

23 are clearly not "necessary" parties under Rule 19(a).

It is not contended that "in [their] absence complete re

lief cannot be accorded among those already parties."

Nor is it contended that their absence would "leave any

of the persons already parties subject to a substantial

risk of incurring double, multiple or otherwise inconsis

tent obligations," since the relief afforded runs to the

entire class.

Finally, it is clear that members of the class

are not "so situated that the disposition of the action

in [their] absence may impede [their] ability to protect

that interest" even when it has been held that the original

named plaintiffs are no longer adequate representatives,

since until a proper representative intervenes, the action

cannot continue as a class action and thus no binding

adjudication will be made with respect to the claims of

such absent members.

Conceding that "the court cannot compel partic

ular students and their parents to serve as representative

36

parties," (R. 107), the district district court errone

ously characterized its highly unorthodox procedure of

section and appointment as merely a "renam[ing] of the

plaintiff class." (R. 132.) But the court has in fact

ordered the Joinder, as parties, of members of the class

who have at no time sought to Intervene in this action,

but who merely remained silent in the face of the strong

urging of the district Judge that they show "an interest 15/

in [their] schools" and Join in the litigation. R. 17 .

There can be no doubt that the "opt-out" pro

cedure adopted by the district court is not the equiva

lent of voluntary intervention, and, therefore, Joinder

of such persons is governed by the Rules which provide

for compulsory Joinder. For the reasons set forth above,

it is clear that under those rules, the district court

had no authority to add randomly selected members of the

class as parties plaintiff.

Thus, at the meeting o f December 1 1 , e v e n e d by the

c l a s ^ r e p r e s e n t a t i v e s . S j j . ” .13^ S S g | - £

was f o r m a l l y ad° p^ d J j . y - ^ c o u n s e l ’ i n th e March 13 o r d e r

o f ^ h e 1 d i s t r i c t c o u r t , from w h i c h ’ t h i s a p p e a l was t a k e n .

37

B. IF THE ORIGINAL NAMED STUDENT-

PLAINTIFFS ARE NO LONGER ADEQUATE

REPRESENTATIVES OF THE CLASS, PETI

TIONERS WERE ENTITLED TO INTERVENE

AS A MATTER OF RIGHT.

Rule 24(a)(2), F. R. Civ. P. provides that persons

directly interested In the subject matter of a lawsuit may

intervene as a matter of right

when the applicant claims an Interest relating to

the property or transaction which is the subject of the action and he is so situated that the dis

position of the action may as a practical matter

impair or impede his ability to protect that in

terest, unless the applicant *s'Interest is adequately represented by existing parties.

Since all members of a class are bound by the

judgment in a class action, each member has clearly satis

fied the prerequisites of Rule 24(a)(2) "unless his interest

is adequately represented by the existing parties". This

was expressly recognised by the authors of amended Rule

24(a):

A class member who claims that his "representative"

does not adequately represent him, and is able to

establish that proposition with sufficient probability, should not be put to the risk of having a

judgment entered in the action which by its terms

extendes to him, and be obliged to test the validity

of the judgment as applied to his interest by a later

collateral attack. Rather he should as a general

rule, be entitled to intervene in the action! ["Ad

visory Committee's Note, supra, at 110.1 (Emphasis added.)

38

It is not disputed that petitioners are bona

fide members of the plaintiff class, as alleged in their

application (R. 163.) Moreover, there can be no doubt that

neither petitioners' interests in the litigation, nor those

of the plaintiffs, can be adeuately represented within the

meaning of Rule 24(a) by parties randomly selected and ap

pointed by the court who at no time sought to intervene in

the action and serve as class representatives or even af

firmatively indicated their desire to do so. Once the dis

trict court found that the original named plaintiffs were

no longer adequate representatives of the class, therefore,

petitioners were entitled to intervene as a matter of right

and the district court clearly erred in denying their appli

cation.

The fact that at the time petitioners sought to

intervene there was an order in effect directing the Board

to make a random selection of members of the class, in con

templation of naming such members as parties and represen

tatives of the class, does not alter petitioners' absolute

right to Intervene under Rule 24(a)(2). In fact, when

petitioners filed their application on December 28, 1974,

no new parties had been formally joined or named as repre

sentatives. It was not until March 13, 1974 that the dis-

39

trict court joined the additional parties and simultaneously

denied petitioners’ application.

C. EVEN IP PETITIONERS WERE NOT ENTITLED TO INTER

VENE AS A MATTER OF RIGHT, AND EVEN IF THE COURT

HAD THE POWER TO JOIN RANDOMLY SELECTED CLASS

MEMBERS AS PARTIES, THE DISTRICT COURT ABUSED

ITS DISCRETION IN DENYING PETITIONERS' APPLI

CATION TO INTERVENE IN FAVOR OF JOINING SUCH

RANDOMLY SELECTED PERSONS AS PARTIES AND REP-

RESENTATIVES OF THE CLASS.______________________ _

On October 26, 1973, the district court entered

its order holding that the original named plaintiffs were

no longer adequate representatives of the class and simul

taneously directing the Board to randomly select members of

the class in contemplation of naming such members as parties

and representatives of the class. As the members of the class

had received no prior notice that the representation by the

existing parties was inadequate, it is not surprising that

at that time there were no members actively seeking to inter

vene in the litigation. However, within a short time after

the entering of the October 26 order, and before the dis

trict court had joined additional parties and named them

as representatives, petitioners filed their application to

intervene. Simultaneously plaintiffs filed a motion re

questing the district court to grant petitioners' applica

tion and to reconsider its announced intention of joining

40

as additional parties persons selected by the court. Plain

tiffs submit that even if the district court in the first

instance had the authority to name additional court-appointed

parties to serve as representatives, once members of the

class actively sought to intervene, the district court

abused its discretion in denying such application in favor

of naming its own appointees as representatives of the

class.

The primary factor in determining whether a party

will adequately represent the class is "the forthrightness

and vigor with which the representative party can be ex

pected to assert and defend the interests of the members of

the class". Mersay v. First Republic Corp., 43 F.R.D. 465,

470 (S.D.N.Y. 1 9 6 8). See also e.&., Dolgov; v. Anderson, 43

F.R.D. 472, 493-94 (E.D.N.Y. 1968); cf. Moore v. Tangipahoa

Parish School Bd., 298 F. Supp. 288, 294 (E.D. La. 1 9 6 9).

See generally 3B Moore, supra, f 23.07C1]. There can be no

doubt that as between members of the class actively seeking

to intervene in the litigation, and randomly selected mem

bers of the class who have neither sought to intervene in

the action nor affirmatively indicated their willingness or

desire to do so, the former are more likely to vigorously

"assert and defend the interests of the member of the class"

and are therefore more adequate representatives.

41

ts.

The position of the Board, adopted by the dis

trict court, is that the parties selected and appointed by

the court are better able to represent the class than are

petitioners for two reasons: 1) the failure of plaintiffs

to supply additional representatives prior to the decision

of the court to fashion its own procedure; and 2) the "ab

solutely fair and impartial manner in which the additional

parties named were selected". (R. 214-5.) Such arguments

misapprehend the proper role to be played both by plaintiffs

and by the court in structuring the lawsuit.

Failure of Plaintiffs to Supply Additional