NAACP v. Alabama Motion and Brief of Amici Curiae

Public Court Documents

October 3, 1957

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. NAACP v. Alabama Motion and Brief of Amici Curiae, 1957. 3fd5222e-bf9a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/3aaa5c44-d60b-4bc1-a6ee-e1c93a1e233f/naacp-v-alabama-motion-and-brief-of-amici-curiae. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

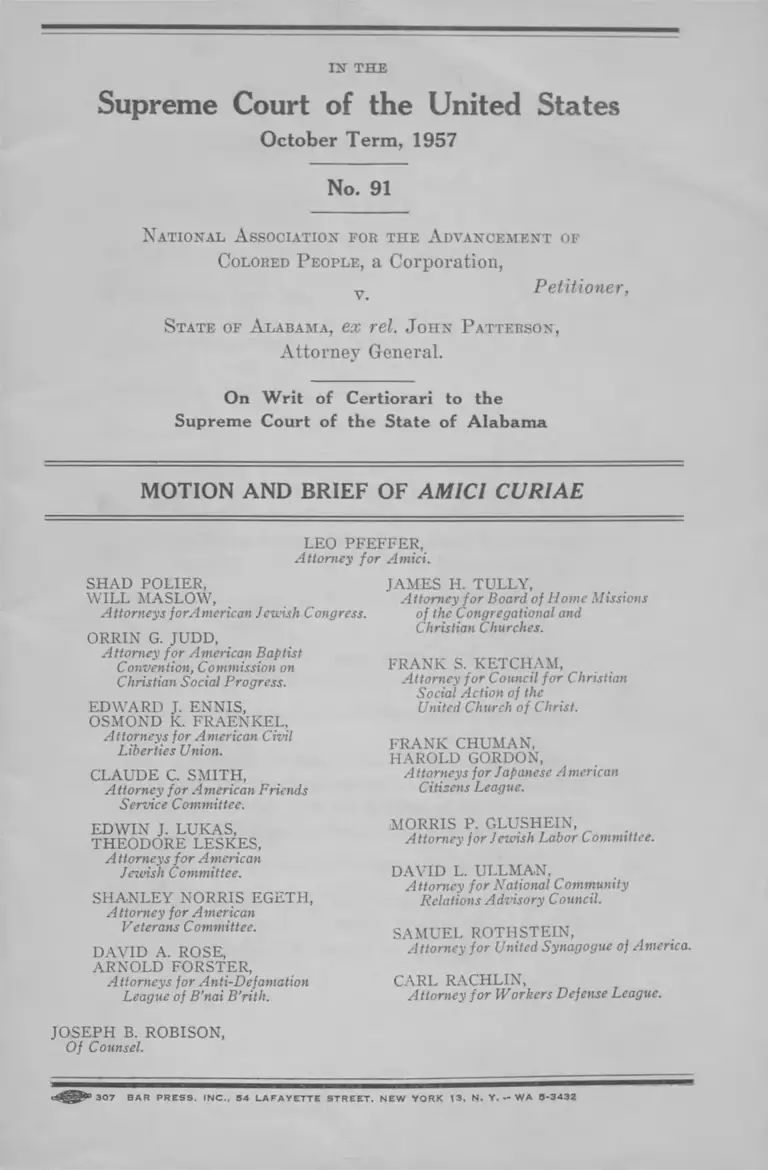

IN THE

Supreme Court of the United States

October Term, 1957

No. 91

National A ssociation fob the A dvancement of

Colored P eople, a Corporation,

v Petitioner,

State of A labama, ex rel. John P atterson,

Attorney General.

On Writ of Certiorari to the

Supreme Court of the State of Alabama

MOTION AND BRIEF OF AMICI CURIAE

LEO PFEFFER,

Attorney for Amici.

SHAD POLIER,

WILL MASLOW,

Attorneys forAmerican Jewish Congress.

ORRIN G. JUDD,

Attorney for American Baptist

Convention, Commission on

Christian Social Progress.

EDWARD J. ENNIS,

OSMOND K. FRAENKEL,

Attorneys for American Civil

Liberties Union.

CLAUDE C. SMITH,

Attorney for American Friends

Service Committee.

EDWIN J. LUKAS,

THEODORE LESKES,

A ttorneys for American

Jewish Committee.

SHANLEY NORRIS EGETH,

Attorney for American

Veterans Committee.

DAVID A. ROSE,

ARNOLD FORSTER,

Attorneys for Anti-Defamation

League of B ’nai B ’rith.

JOSEPH B. ROBISON,

Of Counsel.

JAMES H. TULLY,

A ttomey for Board of Home Missions

of the Congregational and

Christian Churches.

FRANK S. KETCHAM,

Attorney for Council for Christian

Social Action of the

United Church of Christ.

FRANK CHUMAN,

HAROLD GORDON,

A ttorneys for Japanese A meric an

Citizens League.

MORRIS P. GLUSHEIN,

Attorney for Jewish Labor Committee.

DAVID L. ULLMAN,

Attorney for National Community

Relations Advisory Council.

SAMUEL ROTHSTEIN,

Attorney for United Synagogue of America.

CARL RACHLIN,

Attorney for Workers Defense League.

3 0 7 B A R P R E S S . I N C . . 5 4 L A F A Y E T T E S T R E E T , N E W Y O R K |3 , N . Y . — W A 5 - 3 4 3 E

TABLE OF CONTENTS

MOTION FOE LEAVE TO FILE ............................. 1

BRIEF .............................................................................. 5

Statement of the Ca s e ............................................................ 6

Question Presented.................................................................. 7

S ummary of A rgument ............................................................ 8

A rgument ....................................................................................... 9

I. Freedom of Association is a Liberty Guaran

teed by the Fourteenth Amendment to the

United States Constitution and is one of the

Co-Equal Guarantees of the First Amendment

Applied to the States by the Fourteenth........ 9

A. Freedom to Associate as a Constitutional

“ Liberty” ................................................... 9

B. Freedom of Association Under the First

and Fourteenth Amendments .................. 13

C. The Association’s Freedom of Association 21

II. An Organization Whose Purpose and Activi

ties are the Protection of Federally Secured

Rights May Not be Subjected to Oppressive

and Burdensome State Restrictions ................ 22

A. The Nature of Petitioner’s Activity.......... 23

B. Petitioner’s Activities in Vindication of

Federally Secured Rights May Not Be

Unduly Burdened by the State ................ 23

PAGE

I I

III. The State of Alabama may not Directly De

stroy Petitioner or Forbid its Activities........ 27

A. The Special Nature of the Right Claimed 27

B. Alabama has not Demonstrated the Ne

cessity for Its Restrictive Action ............ 28

IV. The State of Alabama may not Indirectly

Destroy Petitioner or Frustrate its Activities

by Requiring it to Expose its Membership

Lists ..................................................................... 30

A. Indirect Destruction and Frustration by

Oppressive Burdens .................................. 30

B. The Oppressive Burden of Compulsory

Exposure ................................. 31

C. The Constitutional Right of Anonymity. .. 33

D. The Place of Anonymity in a Democratic

Society ......................................................... 34

E. Anonymity as an Aid to Free Expression 36

F. Secret Elections in Democracies.............. 38

G. The Absence of Justification for Compul

sory Disclosure ............................................ 38

PAG*

Conclusion 40

I l l

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

Decisions

Abrams v. United States, 250 U. S. 616 (1919).......... 31

Adler v. Board of Education, 342 U. S. 485 (1952).... 22

American Communications Association v. Douds, 339

U. S. 382 (1950)......................................................... 22

American Steel Foundries v. Tri-City Central Trades

Council, 257 U. S. 184 (1921)................................. 17

Barrows v. Jackson, 346 U. S. 249 (1953).................. 40

Beatty v. Gillbanks, 9 Q. B. D. 308 (1882).................. 16

Bolling v. Sharpe, 347 U. S. 497 (1954)...................... 10

Bowe v. Secretary of the Commonwealth, 320 Mass.

230 (1946)................................................................... 17

Bridges v. Wixon, 326 U. S. 135 (1945)........................ 15

Brown v. Topeka, 347 U. S. 483 (1954)...................... 30

Bryant v. Zimmerman, 278 U. S. 63 (1928).................. 39

Buck v. Kuykendall, 267 U. S. 307 (1925).................. 23

City of St. Louis v. Fitz, 53 Mo. 582 (1873)..............11,12

City of St, Louis v. Eoche, 128 Mo. 541 (1895).......... ’ 12

City of Watertown v. Christnacht, 39 S. D. 290

(1917) ......................................................................... 12

Coker v. Fort Smith, 162 Ark. 567 (1924).................. 12

Crandall v. Nevada, 73 U. S. (6 Wall.) 35 (1867).......24, 25

De Jonge v. Oregon, 299 U. S. 353 (1937).................. 14

Edwards v. California, 314 U. S. 160 (1941) .............. 24

Ex Parte Cannon, 94 Tex. Cr. R. 257 (1923) .......... 12

Ex Parte Smith, 135 Mo. 223 (1896).......................... 12

Farrington v. Tokushige, 273 U. S. 284 (1927)......... 30

Fidelity and Deposit Co. v. Tafoya, 270 U. S. 426

( l 926) ................................................................... 23,25,26

PAGE

I V

Gayle v. Browder, 352 IT. S. 903 (1956), a ff’g 142 F.

PAGE

Supp. 707..................................................................... 29

Hague v. CIO, 307 U. S. 496 (1939).............................. 14

Hannegan v. Esquire, 327 IT. S. 146 (1946).............. 30

Hanover Insurance Co. v. Harding, 272 H. S. 494

(1926) ......................................................................... 23

Hill v. Florida, 325 IT. S. 538 (1945).............................. 24

Joint Anti-Fascist Refugee Committee v. McGrath,

341 U. S. 123 (1951)...................................... 15,17,21,31

Kedroff v. St. Nicholas Cathedral, 344 IT. S. 94

(1952) 22

Kovacs v. Cooper, 336 U. S. 77 (1949).......................... 27

Meyer v. Nebraska, 262 IT. S. 390 (1923).................. 9,21

Morgan v. Virginia, 328 U. S. 373 (1946).................. 23

Murdock v. Pennsylvania, 319 U. S. 105 (1943)........... 30

People v. Belcastro, 356 HI. 144 (1934)....................... 12

People v. Pieri, 269 N. Y. 315 (1936).......................... 12

Pierce v. Society of Sisters, 268 IT. S. 510 (1925).......21, 30

Schneider v. New Jersey, 308 U. S. 147 (1939).......... 28

Slochower v. Board of Higher Education, 350 U. S.

551 (1956)................................................................... 24

Southern Pacific Company v. Arizona, 325 U. S. 761

(1945) ......................................................................... 23

Sterling v. Constantin, 287 U. S. 378 (1932).............. 30

Sweatt v. Painer, 339 U. S. 629 (1950)....................... 30

Sweezy v. New Hampshire, 354 IT. S. 234 (1957) ....15, 38, 39

Terral v. Burke Construction Co., 257 U. S. 529

(1922) ......................................................................... 24

Thomas v. Collins, 323 IT. S. 516 (1945)............14,15,28,29

V

United Public Workers v. Mitchell, 330 U. S. 75

(1947) ........................................................................ 15,22

United States v. Congress of Industrial Organiza

tions, 335 U. S. 106 (1948)...................................... 18

Watkins v. United States, 354 U. S. 178 (1957).... 32, 33, 39

Whitney v. California, 274 U. S. 357 (1927)................ 14,15

Statutes

Alabama Code, 1940, Title 10, Secs. 192, 193, 194........ 28

New York Penal Law, Section 722 ................................ 12

PAGE

Miscellaneous

Abernathy, Right of Association, 6 So. Car. L. Q. 32

(1953) 12,20

American Jewish Congress, Assault Upon Freedom

of Association (1957) .............................................. 29

American Law Institute, Statement of Essential Hu

man Rights (distributed by Americans United

for World Organization) ........................................ 16

1 Annals 759-761 ............................................................. 14

Blankenship, How to Conduct Consumer and Opinion

Research (1946) ....................................................... 36

Bleyer, Main Currents in the History of American

Journalism (1927) .................................................... 34

Bryce, The American Commonwealth, Third Edition

(1899), Yol. II ............................................................18,32

Cantril, Gauging Public Opinion (1944) ........................ 37

Chafee, The Blessings of Liberty (1956) ...................... 19

103 Congressional Record A 5882-9 (1957)................... 3

Cushman, Civil Liberties in the United States (1956) 14

V I

Defoe, Shortest Way with the Dissenters.................... 34

De Tocqueville, Democracy in America, Vintage Edi

tion (1954) Vols. I and I I ........................................13,18

Emerson & Haber, Political and Civil Rights in the

United States (1952) ............................................... 15

Fainsod, How Russia is Ruled (1954) .......................... 11

The Federalist, Henry Holt Edition (1898)................ 35

The Federalist, Modern Library Edition (1937)......... 35

Figgis, Churches in the Modern State (1951).............. 22

Foreign Affairs, Vol. 25, Nos. 1 & 4, Vol. 27, No. 2,

Vol. 36, No. 1 ............................................................. 35

Howe, Political Theory and the Nature of Liberty,

67 Harv. L. Rev. 91 (1953).................................. 22

Laski, The Personality of Associations, 29 Harv. L.

Rev. 404 (1916)......................................................... 22

Latham, The Group Basis of Politics (1952)................. 18

Locke, Letter Concerning Toleration (1689)................. 11

Lowell, Public Opinion and Popular Government

(1914) ......................................................................... 19

Maclver, ed., Conflict of Loyalties (1952)...................... 35

Minto, Daniel Defoe (1909)............................................ 34

National Opinion Research Center, Interviewing for

NORC (1945)............................................................. 36

Orwell, Nineteen Eighty-Four........................................ 38

Pound, The Development of Constitutional Guaran

tees of Liberty (1957).............................................. 10

Rose, Theory and Method in the Social Sciences

(1954) ..................................................................... 20

PAGE

V I I

PAGE

Schlesinger, Paths to the Present (1949).............. 18,26,35

State Control of Political Organizations: First

Amendment checks on powers of Regulation, 66

Yale L. J. 545 (1957)............................................. 22

Taylor, How to Conduct A Successful Employees’

Suggestion System................................................... 37

Thomas v. Collins, 1944 Term, No. 14, Brief of United

States, amicus curiae............................................... 33

Tolischus, They Wanted War (1940)............................ 11

Universal Declaration of Human Rights...................... 16

IN THE

Supreme Court of the United States

October Term, 1957

No. 91

National. A ssociation for the A dvancement of

Colored People, a Corporation,

Petitioner,

v.

S tate of A labama, ex rel. John Patterson,

Attorney General.

On Writ of Certiorari to the

Supreme Court of the State of Alabama

MOTION OF AMICI CURIAE

The undersigned, as counsel for American Jewish

Congress; American Baptist Convention, Commission on

Christian Social Progress; American Civil Liberties Union;

American Friends Service Committee; American Jewish

Committee; American Veterans Committee; Anti-Defama

tion League of B ’nai B ’rith; Board of Home Missions of

2

the Congregational and Christian Churches; Council for

Christian Social Action of the United Church of Christ;

Japanese American Citizens League; Jewish Labor Com

mittee; National Community Relations Advisory Council;

United Synagogue of America; and Workers Defense

League, and on their behalf, respectfully move this Court

for leave to tile the accompanying brief as amici curiae.

The organizations that propose to submit this brief are

private, voluntary associations of Americans formed to

achieve specific purposes, religious, civic, educational, and

others. As such, they have a direct interest in this

proceeding which raises the question whether a state may

constitutionally place prohibitions or crippling restrictions

on the operation of a voluntary association similarly or

ganized for a specific purpose, that of promoting equal

rights for all, without discrimination based on race.

The record in this case shows that public officials of

the respondent State of Alabama have attempted to frus

trate the efforts of the petitioner National Association for

the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) on behalf

of the rights of Negroes in Alabama and to outlaw it

from the state. We are concerned with the implications

of this assertion of governmental power irrespective of

whether or not we support the aims of the NAACP in

combatting racial inequality. It has become perfectly

obvious that Alabama not only is attempting to maintain

its statewide pattern of racial segregation but is also

working for the destruction of all organized opposition

to this policy. Alabama’s effort to expel the NAACP has

therefore placed in jeopardy the fundamental constitu

tional right of individuals to join together to form asso

ciations in order to express and advance their views.

The organizations that propose to submit the accom

panying brief are deeply disturbed by this assault on

freedom of association. Today, it is the NAACP that

is subjected to attack. Tomorrow, the same measures

3

may be taken against any group that supports a cause

opposed by state officials.1

In our complex society, the right individually to pro

test, individually to sue or to seek legislation is of but

limited practical value by itself. Particularly in an atmo

sphere of extreme hostility, such as that which now con

fronts Southern opponents of racial segregation, the right

to organize is protected, we believe, by the First, Fifth

and Fourteenth Amendments against interference by gov

ernment authorities.

In the accompanying brief, we argue that the order

affirmed by the court below unreasonably restrains not

only petitioner’s freedom of association as guaranteed by

the First and Fourteenth Amendments but also its lib

erty as guaranteed by the Fourteenth. The argument that

petitioner’s right to exist as an organization is a “ liberty”

within the meaning of that Amendment has not been de

veloped in petitioner’s brief.

We develop the argument that Alabama has unduly

restrained freedom of association, as guaranteed by the

First and Fourteenth Amendments, beyond its treatment

in petitioner’s brief, particularly showing that the right

to freedom of association necessarily includes the right

to preserve, as against unreasonable demands by the

state, the anonymity of those who associate. 1

1 That the N AACP is not the only possible target of oppressive

measures may be seen in a part of a speech made by the trial court

judge in this proceeding. In a speech made on July 11, 1957, Judge

Jones said that (103 Cong. Rec. A 5888-9) :

“ Many of our religious organizations, the NAACP, and it

has the financial and moral backing of the American Jewish

Congress in New York, committees of labor unions, and the

Supreme Court of the United States, and both of the Nation’s

chief political parties, are all working together to achieve com

plete integration of the races, and this we know is the first step

toward amalgamation, the consolidating and fusing into 1 race

the 2, the white and black races.”

4

We make the further argument, not made in petition

er’s brief, that the action of the State of Alabama denies

petitioner due process of law because it unduly burdens

petitioner’s exercise of Federal rights. Petitioner is an

association that was organized, in large part, to win for

Negroes equal protection of the laws as guaranteed by

the Federal Constitution and statutes. This activity, we

maintain, like other activities inherently protected by the

Federal Constitution and statutes, is protected against

undue restraint by the states.

Each of these arguments, if sustained, would require

reversal of the order below.

We respectfully urge that acceptance of this brief

amici curiae is especially appropriate. The organizations

joining in this motion are directly interested in the ques

tion whether the Federal Constitution stands as an effec

tive shield against oppressive action by a state designed

to exclude from its territory any organization it dislikes.

Furthermore, many of them have members in the State

of Alabama. Since the measures taken against the NAACP

here could be taken against any organization, the right

of each of these organizations to exist, as well as that

of the NAACP, is at stake.

We have sought the consent of counsel for both parties

to the filing of this brief. Counsel for petitioner consented

but counsel for the State of Alabama refused consent.

Respectfully submitted,

L eo Peefeer

Attorney for Amici

15 East 84th Street

New York 28, N. Y.

October 3, 1957

IN THE

Supreme Court of the United States

October Term, 1957

No. 91

National A ssociation for the A dvancement of

Colored P eople, a Corporation,

Petitioner,

v.

S tate of A labama, ex rel. J ohn Patterson,

Attorney General.

On Writ of Certiorari to the

Supreme Court of the State of Alabama

------------ m % m -----------

BRIEF OF AMICI CURIAE

The following organizations respectfully submit this

brief, as amici curiae, in support of the petitioner:

American Jewish Congress; American Baptist Conven

tion, Commission on Christian Social Progress; American

Civil Liberties Union; American Friends Service Com

mittee; American Jewish Committee; American Veterans

[ 5 ]

6

Committee; Anti-Defamation League of B ’nai B ’rith;

Board of Home Missions of the Congregational and Chris

tian Churches; Council for Christian Social Action of the

United Church of Christ; Japanese American Citizens

League; Jewish Labor Committee; National Community

Relations Advisory Council; United Synagogue of Amer

ica; and Workers Defense League. Our interest in the

issues raised by this case is set forth in the motion for

leave to file a brief amici curiae annexed hereto.

Statement of the Case

The proceedings in this case are fully detailed in peti

tioner’s brief (pp. 8-11) and will be only briefly sum

marized here.

The petitioner, National Association for the Advance

ment of Colored People (NAACP), is a New York member

ship corporation formed in part to promote equal rights

for Negro citizens of the United States. Petitioner has

maintained a Southeast Regional Office in Birmingham.

Alabama, and has organized local affiliates in that state

(R. 1-2, 6).

On June 1, 1956, the Attorney General of Alabama filed

a bill of complaint in the Circuit Court of Montgomery

County, Alabama, asking it to enjoin petitioner from con

ducting any business in that state. The bill of complaint

charged petitioner with, among other things, not having

registered as a foreign corporation as required by Alabama

law and with having furnished legal help and financial

assistance to persons challenging racial segregation at the

University of Alabama and on the buses in the State

capital (R. 1-2).

On the same day, the Circuit Court issued an ex parte

temporary restraining order and injunction prohibiting

petitioner from conducting any business, from maintaining

7

offices, organizing chapters or soliciting members, contribu

tions or dues in the state. The court also enjoined

petitioner—although the State’s bill of complaint did not

request it—from filing any document with Alabama officials

that would qualify it to do business in the state (R. 2-3,

18-20).

Subsequently, on motion by the State, the court issued

an order of discovery requiring petitioner to produce for

inspection by the State a large number of records and

documents including all correspondence in its Alabama

files concerning certain Federal court suits challenging

racial segregation and a list of all of its members in the

state (R. 6, 20-22). The order was issued over petitioner’s

objection that it violated its constitutional rights (R. 0).

Petitioner, in its answer to the complaint, offered to

comply at once with the registration statute (R. 7). There

after petitioner agreed to submit all the data required

except its correspondence and membership lists (R. 11-13).

The court held this to be insufficient compliance with its

order and fined petitioner $100,000 (R. 14-15). The court

never considered petitioner’s motion to dismiss the original

complaint and the restraining order issued thereunder

(R. 16). Its judgment was affirmed by the Supreme Court

of Alabama (R. 23-30). The proceeding is here on writ of

certiorari to review that decision.

Question Presented

We adopt the statement of the Question Presented as

set forth in petitioner’s brief (p. 2) :

“ Did the State of Alabama interfere with the freedom

of speech and freedom of association and deny due

process of law to petitioner, the NAACP, and its

8

members in violation of the Fourteenth Amendment in

interfering with and prohibiting the continuation of

the efforts of petitioner to secure and enforce rights

of Negro citizens guaranteed by the Constitution and

laws of the United States?”

Summary of Argument

Freedom of association is a liberty guaranteed against

Federal infringement by the Fifth Amendment to the

United States Constitution and against state infringement

by the Fourteenth. In addition it is one of the co-equal

guarantees of the First Amendment applied to the states by

the Fourteenth. It is a freedom secured not only to the

members of the association but to the association itself as

well. In any event, the association has the status to

assert and defend its members’ freedom to associate in it.

Besides the general right of freedom of association

enjoyed by petitioner, it is entitled to special Federal

protection against state interference by reason of the fact

that it is an organization whose purpose and activities are

the protection of Federally secured rights, and as such

may not be subjected to oppressive and burdensome state

restrictions.

For these reasons the State of Alabama may not

destroy petitioner or forbid its activities. Moreover, it may

not indirectly effect the same result by imposing restric

tions whose purpose and effect is to destroy petitioner or

frustrate its activities. In view of the nature of petitioner

and the climate in which it operates in the State of Ala

bama, a requirement that it make public its membership

records constitutes the imposition of an oppressive burden

whose effect is to prevent petitioner from carrying out its

activities in that state.

9

In any event, an association, like an individual, has a

constitutional right of anonymity which may not be gov-

ernmentallv impaired in the absence of some justification

in terms of a lawful governmental objective. No such

justification has been shown in this case and none in fact

exists.

Hence, the order of the Alabama court forbidding peti

tioner to carry on its activities in that state and requiring

it to disclose its membership is unconstitutional state action

in deprivation of rights guaranteed by the Federal Con

stitution and should therefore be reversed and set aside.

ARGUMENT

P O I N T O N E

Freedom of association is a liberty guaranteed by

the Fourteenth Amendment to the United States Con

stitution and is one of the co-equal guarantees of the

First Amendment applied to the states by the

Fourteenth.

A. Freedom to Associate as a Constitutional “ Liberty”

At least since this Court’s decision in Meyer v. Ne

braska, 262 U. S. 390 (1923), it has been recognized that

the liberty secured against state deprivation by the Four

teenth Amendment and Federal deprivation by the Fifth

extends far beyond mere freedom from bodily restraint.

The term “ liberty,” the Court said in that case (262 U. S.

at 399),—

“ denotes not merely freedom from bodily restraint,

but also the right of an individual to contract, to

10

engage in any of the common occupations of life, to

acquire useful knowledge, to marry, establish a home

and bring up children, to worship God according to

the dictates of his own conscience, and generally to

enjoy those privileges long recognized at common

law as essential to the orderly pursuit of happiness

by free men.”

This principle was re-asserted by this Court as

recently as 1954. In Bolling v. Sharpe, 347 U. S. 497, 499,

the Court, speaking through the Chief Justice, said:

“ Although the Court has not assumed to define

‘ liberty’ with any great precision, that term is not

confined to mere freedom from bodily restraint.

Liberty under law extends to the full range of con

duct which the individual is free to pursue, and it

cannot be restricted except for a proper govern

mental objective. ’ ’ 1

*

It is indisputable, we submit, that the associating to

gether by men to pursue a common objective or, indeed,

for no objective other than to enjoy each other’s com

pany is “ conduct which the individual is free to pursue”

in “ the orderly pursuit of happiness by free men.”

Civilized society contemplates free and voluntary asso

ciations among the people. So long as man remains a

gregarious being, his urge to associate with fellow men

will be as vital and as compelling as his urge to live. A

1 Dean Roscoe Pound has pointed out ( The Development of Con

stitutional Guarantees of Liberty (1957), p. 48) that the Constitu

tion was drafted by lawyers who took Lord Coke’s comments on

Magna Carta “ for a legal Bible” and that Coke there described the

word “ liberties” as “ meaning more than freedom of the physical

person from arrest or imprisonment” but as including “ the freedoms

that men have.”

11

constitutional provision protecting liberty against arbi

trary governmental deprivation would have little mean

ing if it did not encompass the freedom of men to asso

ciate with each other.

What John Locke, in his Letter Concerning Toleration

(1689), said about religious association has been recog

nized and accepted as part of our constitutional system

in respect to all associations. A “ society of members

voluntarily uniting to [a common] end” is entitled to

manage its own affairs and to be free from arbitrary

governmental restrictions and restraints. A totalitarian

state is by its nature suspicious of, if not actively hostile

to, all associations not dominated by the state and looks

to every such association as a potential rival if not

enemy.2 Our Anglo-American heritage on the other hand

welcomes voluntary associations as an indispensable as

pect of a democratic pluralistic society.

The state courts have uniformly recognized freedom

to associate as a liberty constitutionally protected from

arbitrary governmental restraint. As long ago as 1878, in

City of St. Louis v. Fits, 53 Mo. 582, a concurring opin

ion by Judge Sherwood of the Missouri Supreme Court

condemned as unconstitutional on its face an ordinance

making it a crime “ knowingly to associate with persons

having the reputation of being thieves and prostitutes.”

He declared that “ its direct effect is to invade and neces

sarily destroy one at least of those ‘ certain inalienable

rights’ of the citizen bestowed by the Creator and guar

anteed by the organic law, personal liberty.” Although

the majority of the court held only that the ordinance

was unconstitutional as construed, a similar ordinance

2 Suppression of independent associations is a normal and neces

sary feature of totalitarian regimes, both Communist (Fainsod. How

Russia is Ruled (1954), pp. 109, 127, 320) and Fascist (Tolischus,

They Wanted War (1940), pp. 143-4).

12

was subsequently declared unconstitutional on its face in

City of St. Louis v. Roche, 128 Mo. 541 (1895). At that

time, the Missouri court expressly approved Judge Sher

wood’s opinion in the Fitz case. In the Roche case, the

court said (128 Mo. at 546):

“ If it can he made a penal offense for a person to

associate with those of his own choosing, however

disreputable they may he, when not in furtherance

of some overt act of public indecency, or the per

petration of some crime, then it necessarily follows

that by the same authority he may be compelled to

associate with persons not of his own choosing.”

The Roche decision was followed in Ex Parte Smith,

135 Mo. 223 (1896). Subsequently, a number of state courts

followed the lead thus given by Missouri. Ex Parte Can

non, 94 Tex. Cr. E. 257 (1923); City of Watertown v.

Christnacht, 39 S. D. 290 (1917); Coker v. Fort Smith, 162

Ark. 567 (1924) and People v. Belcastro, 356 111. 144

(1934). In the last cited case, the court summed up the

holdings of the various cases in the statement that “ No

legislative body in this country possesses the power to

choose associates for citizens” (356 111. at 148).3

Even where a “ consorting with criminals” statute has

been upheld, it has been on the basis that the statute

required the association to be with intent to commit a

crime. Thus, in sustaining the validity of section 722 of

the New York Penal Law, which makes it a misdemeanor

to consort with thieves and criminals “ with intent to pro

voke a breach of the peace” and “ with an unlawful

purpose,” the Court of Appeals said (People v. Pieri, 269

N. Y. 315, 322, 324 (1936):

3 The cases are discussed in Abernathy, “ Right of Association,”

6 So. Car, L. Q. 32, 46-47 (1953).

13

“ The combination of intents, however, indicates that

the association of these evil-minded persons must be

to do or plan something unlawful. The consorting

alone is no crime * * *.

“ * * * Mere association of people of ill repute with

no intent to breach the peace or to plan or commit

a crime is too vague a provision to constitute an

offense.”

In sum, as de Tocqueville said more than a hundred

years ago (Democracy in America, Vintage Edition (1954),

Vol. I, p. 203) :

“ The most natural privilege of man, next to the right

of acting for himself, is that of combining his exertions

with those of his fellow creatures and of acting in

common with them. The right of association therefore

appears to me almost as inalienable in its nature as the

right of personal liberty. No legislator can attack

it without impairing the foundations of society.”

Of course, like all other constitutionally protected rights,

the right to associate is subject to reasonable restrictions

where necessary for the protection of a paramount com

munal interest. We discuss below whether the limitation

on petitioner’s freedom imposed by Alabama is a reason

able restriction on this constitutional right.

B. Freedom of Association Under the First and Four

teenth Amendments

The First Amendment provides that:

“ Congress shall make no law respecting an establish

ment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise there

o f; or abridging the freedom of speech or of the press;

14

or the right of the people peaceably to assemble and

to petition the Government for a redress of griev

ances.”

This Court has declared that, “ The right of peaceable

assembly is a right cognate to those of free speech and

free press and is equally fundamental.” DeJonge v. Ore

gon, 299 U. S. 353, 364 (1937). The three rights, indeed,

are “ inseparable.” Thomas v. Collins, 323 U. S. 516, 530

(1945). Thus the right of assembly is “ an independent

right similar in status to that of speech and press.” Cush

man, Civil Liberties in the United States (1956), p. 60.4

Like the other basic First Amendment freedoms, free

dom of assembly is protected by the Fourteenth Amend

ment against unreasonable impairment by the states.

DeJonge case, supra; Whitney v. California, 274 U. S. 357

(1927); Thomas v. Collins, supra; Hague v. Committee for

Industrial Organization, 307 U. S. 496 (1939).

It is now also well established that freedom of as

sembly is not limited to occasional meetings but includes

the organization of associations on a permanent basis.

4 The First Congress, while it was drafting the First Amendment,

was clearly reminded that the three rights were part of a seamless

web (1 Annals 759-761): At one point, Representative Sedgwick

objected to inclusion of assembly with speech and press as being too

trifling and obvious. “ If people freely converse together they must

assemble for that purpose; it is a self-evident, unalienable right which

the people possess; it is certainly a thing that never would be called

in question; * * * ” He likened it to listing the right to put on one’s

hat. Representative Page noted that the right of assembly and, in

deed, the right to wear a hat, had been infringed upon and it was

necessary to protect the right of assembly because “ If the people

could be deprived of the power of assembling under any pretext

whatsoever, they might be deprived of every other privilege contained

in the clause.”

15

Thus, “ freedom of association” may be viewed as a

right to conduct indefinitely continuing assemblies.5

Thus, in Thomas v. Collins, supra, this Court held

that the right to discuss labor unions and to urge people

to join them “ is protected not only as part of free speech,

but as part of free assembly” (323 U. S. at 532).

As early as 1927, this Court recognized freedom of

association as a separate and independent right in hold

ing that a California anti-syndicalism law was a restraint

upon “ the rights of free speech, assembly, and associa

tion” but that it was necessary to protect the state from

serious injury. Whitney v. California, supra, 274 U. S. at

372. Subsequently, in Joint Anti-Fascist Refugee Com

mittee v. McGrath, 341 U. S. 123, 141 (1951), the func

tioning of associations was described as “ a legally pro

tected right.” See also United Public Workers v. Mitchell,

330 U. S. 75 (1947); Bridges v. Wixon, 326 U. S. 135, 163

(1945).

The constitutional status of freedom of association

was most recently reaffirmed by this Court in Sweezy v-

New Hampshire, 354 U. S. 234, 250 (1957).

5 The constitutional synthesis is described in Emerson & Haber,

Political and Civil Rights in the United States (1952), p. 248:

“ This right of association is basic to a democratic society.

It embraces not only the right to form political associations but

also the right to organize business, labor, agricultural, cultural,

recreational and numerous other groups that represent the mani

fold activities and interests of a democratic people. In many of

these areas, an individual can function effectively in a modern

industrial community only through the medium of such or

ganization * * *

“ The United States Constitution nowhere explicitly recog

nizes a right to form political organizations. * * * Yet it is

generally accepted that the rights in the First Amendment to

freedom of speech, press and assembly, and to petition the gov

ernment for redress of grievances, taken in combination, estab

lish a broader guarantee to the right of political association.”

16

“ * * * Our form of government is built on the

premise that every citizen shall have the right to

engage in political expression and association. This

right was enshrined in the First Amendment of the

Bill of Rights. Exercise of these basic freedoms in

America has traditionally been through the media of

political associations. Any interference with the free

dom of a party is simultaneously an interference with

the freedom of its adherents.”

Freedom of association has also been given interna

tional recognition. On December 10, 1948, the General

Assembly of the United Nations, with the full approval

and support of the United States, adopted the Universal

Declaration of Human Rights, Article 20(1) of which de

clares :

“ Everyone has the right to freedom of peaceable

assembly and association.” 6

Thus, freedom of speech, press, assembly and asso

ciation are all part of one complex in which each supports

the others. I f any one is recognized, logic requires equal

recognition of the rest. Conversely, impairment of any

one necessarily impairs the effectiveness of the rest.

0 This provision came about as result of the activities of a com

mittee appointed in 1945 by the American Law Institute. The com

mittee, representing the “ principal cultures of the world,” published

a “ Statement of Essential Human Rights” (distributed by Americans

United for World Organization). That group took pains to spell out

the guarantee of freedom of association as distinct from freedom of

assembly. Article Four of the Statement guarantees freedom of

assembly. Article Five provides :

“ Freedom to form with others associations of a political, eco

nomic, religious, social, cultural, or any other character for pur

poses not inconsistent with these articles is the right of every

one.”

See also Beatty v. Gillbanks, 9 Q. B. D. 308 (1882).

17

While we do not believe that freedom of association

is limited to circumstances in which it is used to imple

ment assertion of the other freedoms, it is at least true

that it finds part of its justification in its ability to do so.

This was aply spelled out by the Supreme Court of Massa

chusetts in a decision condemning a statute curbing politi

cal activity of labor unions. In Bowe v. Secretary of the

Commonwealth, 320 Mass. 230, 252 (1946), the court said:

“ One of the chief reasons for freedom of the press

is to ensure freedom, on the part of individuals and

associations of individuals at least, of political dis

cussion of men and measures, in order that the elec

torate at the polls may express the genuine and in

formed will of the people. (Citations omitted) Indi

viduals seldom impress their views upon the elec

torate without organization. They have a right to

organize into parties, and even into what are called

‘ pressure groups,’ for the purpose of advancing

causes in which they believe.”

The late Mr. Justice Jackson, concurring in the Joint

Anti-Fascist case, supra (341 U. S. at 187), noted that

citizens must often

“ * * * pool their capital, their interests, or their ac

tivities under a name and form that will identify col

lective interests, * * * to permit the association or

corporation in a single case to vindicate the interests

of all.” 7

7 It was this same need to pool strength and resources that was

recognized by Chief Justice Taft in his classic defense of the right of

workers to organize unions. American Steel Foundries v. Tri-City

Central Trades Council, 257 U. S. 184, 209 (1921).

18

Mr. Justice Rutledge similarly noted (concurring in U. S.

v. Congress of Industrial Organizations, 335 U. S. 106,

143-4 (1948)):

“ The expression of bloc sentiment is and always

has been an integral part of our democratic elec

toral and legislative processes. They could hardly

go on without it. Moreover, to an extent not neces

sary now to attempt delimiting, that right is secured

by the guaranty of freedom of assembly, a liberty

essentially coordinate with the freedoms of speech,

the press, and conscience.”

Judicial recognition of freedom of association as a

constitutional right mirrors a fact of American life long

recognized by observers of the American scene.8 Alexis

de Tocqueville remarked in 1840 that Americans form

associations for every possible purpose. Noting that such

joint activity was necessary in a democracy, he concluded

that, “ If men living in democratic countries had no right

and no inclination to associate for political purposes,

their independence would be in great jeopardy; * * *”

(de Tocqueville, supra, Vol. II, p. 115).

Forty-eight years later, Lord Bryce similarly stressed

the importance of associations in this country. He said

(The American Commonwealth, Third Edition (1899), Vol.

II, pp. 278-279):

“ Such associations have great importance in the

development of opinion, for they rouse attention, excite

discussion, formulate principles, submit plans, em

bolden and stimulate their members, produce that im

pression of a spreading movement which goes so far

8 See the chapter, “ Biography of a Nation of Joiners,” in Schles-

inger, Paths to the Present (1949), pp. 23-50. The special impor

tance of the group as “ the basic political form” is stressed in Latham,

The Group Basis of Politics (1952), p. 10.

19

towards success with a sympathetic and sensitive

people * * * this habit of forming associations * * *

creates new centres of force and motion, and nourishes

young causes and unpopular doctrines into self-confi

dent aggressiveness.”

President Lowell of Harvard University said in 1914

(Public Opinion and Popular Government, American Citi

zen Series, p. 39):

“ Freedom of expressing dissent includes liberty of

organization, and in order that this may be completely

effective it must not be confined to purely political

objects, but must become a part of the popular customs,

covering all matters in which people are interested.”

This theme was reiterated most recently by the late Pro

fessor Chafee (The Blessings of Liberty (1956), pp. 150-

151):

“ If we look over our national history, we see that many

of the most significant political and social changes

began with the efforts of some small informal group

disliked by the ordinary run of citizens. The abolition

of slavery grew out of Garrison’s Anti-Slavery Society

and similar associations. The Nineteenth Amendment

is the culmination of the activities of a few unpopular

women in the middle of the last century. The popular

election of Senators, the federal income tax, and sev

eral other reforms largely originated with the Grangers

and the Populists * * *. Under modern conditions,

freedom of speech under the First Amendment is likely

to be ineffective if it means only the liberty of an

isolated individual to talk about his ideas. Indeed,

from the very beginning, freedom of speech has in

volved the liberty of a number of individuals to asso

ciate themselves for the advocacy of a common purpose

20

whether they exchange ideas in a hall or by mail like

the Committees of Correspondence before the Revolu

tion. Thus, freedom of speech and freedom of assem

bly fit into each other. They are both related to the

possibility of petitioning Congress and the state legis

latures for redress of grievances, which is only part

of the wider freedom to submit the views of the indi

vidual or the group to the people at large for judg

ment.”

An apt summary is supplied by a South Carolina political

scientist (Abernathy, “ Right of Association,” 6 So. Car.

L. Q. 32, 75-76 (1953)):

“ Associations have a place of particular importance

in a democracy, whether they are associations of

laborers, professional men, or electors and office-

seekers. They serve as a training ground for group

participation, organization and management of people

and programs, and for democratic acceptance of the

majority will. They can also serve as a potential

influence for improvement of communication between

the individual and the government. Concerted demands

for action by associations of people have a better

chance for accomplishing the desired governmental

action than do scattered individual requests. And the

information furnished to administrators and legisla

tors by private associations of various kinds is in many

instances vital to the intelligent treatment of particu

lar problems.”

It is not surprising therefore to find that at least 5,000

national associations exist in the United States. (Rose,

Theory and, Method in the Social Science (1954), pp. 52n,

55-56.)

C. The Association’s Freedom of Association

We submit that the freedom of association guaranteed

by the Constitution is enjoyed not merely by the individual

members of the association but by the association itself.

Indeed, freedom of association would be of little value if

only the individual members could assert judicially a claim

to its protection, for the justification for freedom of asso

ciation lies in the recognition that unorganized individuals

are frequently unable or unwilling to assert the rights that

lie at the foundation of a democratic society. Accordingly,

this Court has frequently recognized and acknowledged the

status of an association to assert its members’ right that

the association be permitted to exist and to conduct its

activities free of unreasonable and oppressive government

restrictions.

Pierce v. Society of Sisters, 268 U. S. 510 (1925), we sub

mit, is exactly in point. In that case, this Court, following

Meyer v. Nebraska, supra, held that the right of parents

to have their children educated in private schools was a

constitutionally protected liberty under the Fourteenth

Amendment. But the right was not asserted by any parent;

no parent was a party to the litigation between the private

association conducting the school and the State of Oregon.

Nevertheless, the Court expressly allowed the association to

assert the right.

Determinative too, we submit, is Joint Anti-Fascist

Committee v. McGrath, supra, wherein this Court recog

nized the constitutional right of associations to be free from

arbitrary governmental action whose “ effect is to cripple

the functioning and damage the reputation of those organi

zations in their respective communities and in the nation”

22

(341 U. S. at 139). In Kedroff v. St. Nicholas Cathedral,

344 U. S. 94 (1952), this Court recognized the right of a

religious association to assert judicially its members’ con

stitutionally protected freedom of worship and its own

right to freedom from arbitrary governmental interference

with its activities.9 These and other decisions of this Court

(e.g., Adler v. Board of Education, 342 U. S. 485 (1952);

American Communications Association v. Bonds, 339 U. S.

382 (1950); United Public Workers v. Mitchell, 330 U. S. 75

(1947)) expressly or implicitly recognize the status of an

association to assert in its own right the constitutional

freedom from arbitrary restraints upon its existence or its

activities.10

P O I N T T W O

An organization whose purpose and activities are

the protection of Federally secured rights may not be

subjected to oppressive and burdensome state re

strictions.

We have sought to show above that the petitioner herein

and its members enjoy a constitutionally protected freedom

of association immune from arbitrary and unreasonable

state restraints. It also has a right of narrower scope,

predicated on the particular nature of the organization and

the organized activity here affected. We here argue that

the activities of petitioner in seeking enforcement of

Federally secured rights are entitled to protection from

oppressive or burdensome state interference, wholly aside

from its rights as a lawful association.

9 See also: Howe, “ Political Theory and the Nature of Liberty,’’

67 Harv. L. Rev. 91 (1953) ; Figgis, Churches in the Modern State

(1951) ; Laski, “ The Personality of Associations,” 29 Harv. L. Rev.

404 (1916).

10 See also Comment: “ State Control of Political Organizations:

First Amendment Checks on Powers of Regulation,” 66 Yale L. T.

545, 546-550 (1957).

23

A. The Nature of Petitioner’s Activity

The formation, organization and structure of the

NAACP are described in its brief (pp. 2-7). As there clearly

appears, one of the primary purposes of the Association

and its principal activity is protection of the rights of

equality guaranteed by the United States Constitution and

by Federal statutes.

The State of Alabama has itself placed that fact beyond

dispute. One of its complaints against the Association, on

which it based its demand that its activities be terminated,

was the fact that the Association had supported efforts to

end state-enforced racial segregation (R. 2). This proceed

ing was thus avowedly designed to frustrate efforts to

vindicate Federally secured rights. The order issued by

the trial court has accomplished that aim. The barrier to

vindication of constitutional guarantees has been erected

by action of the state, through its executive and judicial

branches.

B. Petitioner’s Activities in Vindication of Federally Se

cured Rights May Not Be Unduly Burdened by the

State

We submit that the petitioner’s interest in the vindica

tion and enforcement of Federal constitutional and statu

tory guarantees stands on the same footing as other Feder

ally secured interests that this Court has protected from

undue burden by the states.

Thus, this Court has repeatedly invalidated state laws

burdening interstate commerce. See, for example, Buck v.

Kuykendall, 267 U. S. 307 (1925); Fidelity and Deposit Co.

v. Tafoya, 270 U. S. 426 (1926); Hanover Insurance Co. v.

Harding, 272 U. S. 494 (1926); Southern Pacific Company v.

Arizona, 325 U. S. 761 (1945); Morgan v. Virginia, 328

24

U. S. 373 (1946). It has similarly condemned limitations on

the movement of individuals from state to state. Crandall

v. Nevada, 73 U. S. (6 Wall.) 35 (1867); Edwards v. Cali

fornia, 314 U. S. 160 (1941). It has curbed state legislation

restraining exercise of rights created by Federal laws.

Hill v. Florida, 325 U. S. 538 (1945). In Slochower v.

Board of Higher Education, 350 U. S. 551 (1956), this

Court struck down a statute penalizing the exercise of the

Fifth Amendment privilege against self-incrimination, not

ing that (350 U. S. at 558):

“ The heavy hand of the statute falls alike on all who

exercise their constitutional privilege, the full enjoy

ment of which every person is entitled to receive.”

Particularly significant to the instant proceeding is the

protection that has been given to the right to invoke the

processes of the Federal courts. In Terral v. Burke Con

struction Co., 257 U. S. 529 (1922), that right was held para

mount to the very state interest involved here, regulation

of foreign corporations. This Court invalidated an Ar

kansas law that prohibited foreign corporations from doing

business in Arkansas if they availed themselves of the

right to start suits in a Federal court or have them removed

to such a court. In words clearly applicable here, Chief

Justice Taft said that condemnation of the statute (257

U. S. at 532-3)

“ * * * res ŝ on the ground that the Federal Consti

tution confers upon citizens of one State the right to

resort to federal courts in another, that state action,

whether legislative or executive, necessarily calculated

to curtail the free exercise of the right thus secured is

void because the sovereign power of a State in exclud

ing foreign corporations, as in the exercise of all others

25

of its sovereign powers, is subject to the limitations of

the supreme fundamental law.”

The mere fact that the State of Alabama has the right

to regulate the operation of foreign corporations within

its borders does not give it carte blanche to curb their

activities in asserting Federal rights. Justice Holmes

pointed this out in Fidelity v. Tafoya, supra (270 U. S.

at 434):

“ But it has been held a great many times that the

most absolute seeming rights are qualified, and in

some circumstances become wrong. One of the most

frequently recurring instances is when the so-called

right is used as part of a scheme to accomplish a

forbidden result. Frick v. Pennsylvania, 268 U. S.

473. American Bank and Trust Co. v. Federal Re

serve Bank of Atlanta, 256 U. S. 350, 358. Badders

v. United States, 240 U. S. 391, 394. United States v.

Reading Co., 226 U. S. 324, 357. Thus the right to

exclude a foreign corporation cannot be used to pre

vent it from resorting to a federal court, Terral v.

Burke Construction Co., 257 U. S. 529; or to tax it

upon property that by established principles the

State has no power to tax, Western Union Telegraph

Co. v. Kansas, 216 U. S. 1, * * *”

The Crandall case, supra, makes it clear that the

government and the citizen are equally entitled to de

mand protection against such interference. This Court

there pointed out that the Federal government frequently

has need to move its officials from state to state and could

not permit taxes on such movements. It went on (73

U. S. at 4 4 ):

26

“ But if the government has these rights on her own

account, the citizen also has correlative rights. He

has the right to come to the seat of government to

assert any claim he may have upon that government,

or to transact any business he may have with it. To

seek its protection, to share its offices, to engage in

administering its functions * * * and this right is in

its nature independent of the will of any State over

whose soil he must pass in the exercise of it.”

We submit that the State of Alabama denies petitioner

due process of law when it uses its courts to prevent or

deter the petitioner from furnishing legal counsel to an

Alabama citizen in a proceeding designed to test the

State’s “ policy of denying entrance to Negroes” (R. 2),

or to prevent it from supporting action “ to compel the

Capitol Motor Lines of Montgomery, Alabama, to seat

passengers without reference to race” (R. 2). These

allegations in the State’s complaint make it plain that

the proceeding instituted by Alabama was intended to halt

and has in fact halted legitimate efforts to invoke Federal

law. It was thus “ part of a scheme to accomplish a for

bidden result.” Fidelity v. Tafoya, quoted supra.

It is no answer to say that the State of Alabama has

not interfered with individuals seeking to vindicate

Federal rights but only with those who offer them or

ganized support. We have shown above that organization

is virtually essential to the advancement of unpopular

causes in today’s complex society. It is plain enough, as

Professor Arthur Schlesinger says (op. cit., supra, at

p. 49), that:

“ The burden of championing minority rights and un

popular causes has fallen on other types of associa

27

tions, notably humanitarian, labor and reform bodies.

These have helped educate the public to the need for

continuing change and improvement and in their as

pects as pressure groups have done much to keep

legislatures and political parties in step with the

times.”

Petitioner’s activities are designed to give reality to

Federal constitutional guarantees. The national interest

in the same end requires this Court to remove unwar

ranted restraints upon efforts to achieve it.

P O I N T T H R E E

The State of Alabama may not directly destroy pe

titioner or forbid its activities.

A. The Special Nature of the Right Claimed

We have shown that the right of association is pro

tected by the First and Fourteenth Amendments. We con

tend that this right, especially when, as here, it is exer

cised with a view to vindication of other constitutionally-

protected rights in the Federal courts, is among “ those

liberties of the individual which history has attested as

the indispensable conditions of an open as against a closed

society [and which therefore] come to this Court with a

momentum for respect lacking when appeal is made to

liberties which derive merely from shifting economic ar

rangements.” Mr. Justice Frankfurter, concurring in

Kovacs v. Cooper, 336 U. S. 77, 95 (1949).

The right of association, as exercised by petitioner and

as sought to be abridged by respondent, is one of the

rights which lie “ at the foundation of free government

by free men. * * * In every case, therefore, where legis-

2 8

lative abridgement of the rights is asserted, the courts

should be astute to examine the effect of the challenged

legislation. Mere legislative preference or beliefs respect

ing matters of public convenience may well support regu

lation directed at other personal activities, but be insuffi

cient to justify such as diminishes the exercise of rights

so vital to the maintenance of democratic institutions.”

Schneider v. New Jersey, 308 U. S. 147, 161 (1939).

In weighing the state action here attacked against the

right here asserted, it should be remembered that “ the

usual presumption supporting legislation is balanced by

the preferred place given in our scheme to the great, the

indispensable democratic freedoms secured by the First

Amendment.” Thomas v. Collins, 323 U. S. 516, 530

(1945). Much more than a mere “ rational basis” must

he shown to justify state interference with the funda

mental right sought to be exercised by petitioner.

B. Alabama Has Not Demonstrated the Necessity for Its

Restrictive Action

As against the societal interest in preserving freedom

of association, and the special Federal interest in pro

tecting activities for the vindication of Federally secured

rights, what can Alabama offer as justification for the

order it has sought and obtained from its courts pro

hibiting petitioner from functioning? The only apparent

goals of the proceeding initiated by the state are enforce

ment of its law requiring registration of foreign cor

porations11 and prevention of anti-segregation activity.

The first of these goals is manifestly insufficient to

justify the Draconian action taken here. As petitioner 11

11 We take no position on whether the Alabama statute dealing

with foreign corporations (Ala. Code, 1940, Title 10, Secs. 192, 193,

194) actually requires petitioner, a non-profit membership corpora

tion, to register or whether the statute is valid as so applied.

29

has amply shown in its brief (pp. 32-38), if Alabama

sought only the enforcement of its registration statute,

it was entirely unnecessary to put the Association out of

business by a judicial order, entered without notice or

hearing. Moreover, in view of petitioner’s assertion, early

in the proceeding, that it was prepared to comply with

the registration requirement (R. 7), the continuation of

the proceeding and the court’s order prohibiting the

Association from complying patently had a deeper

motivation.

This can be found in the allegations in the State’s orig

inal bill of complaint that petitioner was engaged in anti

segregation activities and that it was causing “ irreparable

injury to the property and civil rights of the citizens of

Alabama” (R. 2). The allegations of petitioner’s anti

segregation activity are the only part of the bill of com

plaint that can account for the State’s insistence that peti

tioner immediately cease operations. Moreover, the meas

ures taken against the NAACP here are part of a pattern

of similar steps taken by other states, all designed to make

it impossible for the NAACP to operate (Assault Upon

Freedom of Association, A Study of the Southern Attack

Upon the National Association for the Advancement of

Colored People, American Jewish Congress (1957)).

But Alabama’s interest in halting anti-segregation ac

tivity (presumably in order to “ protect the public against

false doctrine,” Mr. Justice Jackson concurring in Thomas

v. Collins, supra, 323 U. S. at 545) certainly cannot out

weigh the constitutional objective of protecting freedom

of association and protecting vindication of Federally se

cured rights. Indeed, that interest cannot even claim a

place in the scales. The segregation that Alabama seeks

to preserve at its State University and on the bus lines in

its State capital has been specifically condemned by this

and other Courts. Gayle v. Browder, 352 U. S. 903 (1956),

30

affirming 142 F. Supp. 707; Brown v. Topeka, 347 U. S. 483

(1954); Sweatt v. Painter, 339 U. S. 629 (1950). The obli

gation of the State of Alabama toward petitioner and its

members is to grant them “ protection in the lawful exer

cise of their rights as determined by the courts” and not

“ to make that exercise impossible.” Sterling v. Con

stantin, 287 IT. S. 378, 402 (1932).

P O I N T F O U R

The State of Alabama may not indirectly destroy

petitioner or frustrate its activities by requiring it to

expose its membership lists.

A. Indirect Destruction and Frustration by

Oppressive Burdens

If freedom to associate may not be directly forbidden,

the same result cannot constitutionally be achieved by im

posing burdensome conditions that effectually prevent or

unduly harass its exercise. Hannegan v. Esquire, 327 U. S.

146 (1946); Murdock v. Pennsylvania, 319 U. S. 105 (1943).

This was plainly established by this Court in its successive

decisions in Pierce v. Society of Sisters, supra and Far

rington v. Tokushige, 273 U. S. 284 (1927). In Pierce, this

Court held that a state could not constitutionally prohibit

the operation of private schools. Two years later, in Far

rington, it held equally unconstitutional minute and de

tailed government regulation that would have made their

operation difficult if not impossible. As the Pierce case

held that a private, voluntary educational association could

not constitutionally be outlawed, the Farrington case held

that the operations of such an association could not consti

tutionally be subjected to oppressive and burdensome

regulations.

31

B. The Oppressive Burden of Compulsory Exposure

The mantle of protection that the Constitution throws

over the right to hold and espouse political, religious and

other views is designed primarily for those who adhere to

unpopular causes, those who advance the “ opinions we

loathe.” (Justice Holmes dissenting in Abrams v. U. S.,

250 U. S. 616, 630 (1919).) No Bill of Rights is needed to

protect what is popular and conventional. Thus, we must

assume, in testing any proposed application of the consti

tutional guarantees, that the cause in question is repudi

ated and actively opposed by the majority of the commu

nity and, probably, by those who control the government

as well.

In this case, however, it is not necessary to hypothesize

the unpopularity of the cause. Here, not only unpopularity

but official hostility is plainly shown. We need not repeat

the ample demonstration made in petitioner’s brief (pp.

12-17) that any Negro in Alabama whose affiliation with

petitioner becomes public runs a substantial risk of eco

nomic retribution and even physical violence.

Indeed, in at least one respect, punishment is imposed

by agencies of the respondent itself. Under local laws

adopted by the State legislature, the boards of education

of two Alabama counties are authorized to discharge pub

lic school teachers who belong to organizations advocating

racial integration (R. 13). If petitioner produced its mem

bership lists containing the names of teachers in those

counties, their jobs would be forfeited under these laws.

In Joint Anti-Fascist Refugee Committee v. McGrath,

supra, it was recognized that the climate in which an or

ganization exists and carries on its activities is a reality

that must be considered in determining whether the organi

zation has been accorded due process of law. The Court

32

there sustained the legal sufficiency of a complaint which

alleged that the action of the Attorney General “ caused

many contributors, especially present and prospective civil

servants, to reduce or discontinue their contribution to

the organization; members and participants in its activi

ties have been ‘ vilified and subjected to public shame, dis

grace, ridicule and obloquy * * * ’ thereby inflicting upon

it economic injury and discouraging participation in its

activities; it has been hampered in securing meeting

places; and many people have refused to take part in its

fund-raising activities” (341 U. S. at 131).

The oppressive effect of exposure was also clearly rec

ognized in the recent case of Watkins v. U. S., 354 U. S.

178,197 (1957) wherein this Court stated that when “ forced

revelations concern matters that are unorthodox, unpopu

lar, or even hateful to the general public, the reaction in

the life of the witness may be disastrous.”

The very factors that justify protection of freedom of

association in a democracy require also that organizations

be protected from prying by an unfriendly government.

If association “ nourishes young causes and unpopular

doctrines into self-confident aggressiveness” (Bryce, su

pra), it is only after they have grown strong enough to

“ produce that impression of a separate movement which

goes so far towards success” (ibid). At the early critical

formative stage of a movement, anonymity may well mean

the difference between life and death.

The close relationship of anonymity to effective organi

zation has received express recognition under the Federal

statutes guaranteeing the right of employees to organize

labor unions. As petitioner’s brief clearly demonstrates

(pp. 27-29), the rights created by the Wagner Act would

be illusory if the employer were free to discover the names

of the first employees to join. Hence, the National Labor

Relations Board and the courts have held that the right

33

to organize necessarily includes the right to do so secretly,

as petitioner has shown in its brief.12

We submit, therefore, that state-compelled disclosure

of the membership of an unconventional or unpopular asso

ciation destroys its effectiveness and frustrates perform

ance of its constitutionally protected activities. Such state

compulsion is as violative of First and Fourteenth Amend

ment rights as is direct destruction of the association or

prohibition of its activities, unless it is necessary to achieve

a paramount state objective. We show below that no

such justification appears here.

C. The Constitutional Right of Anonymity

Aside from the harrassing aspect of the requirement

of exposure, we believe that it impairs a constitutional right

of anonymity that may not be infringed in the absence of an

overriding communal interest which the state is constitu

tionally competent to protect. The right of anonymity is

an incident of a civilized society and a necessary adjunct

to freedom of association and to full and free expression

in a democratic state.

In Watkins v. U. S., supra, this Court said (354 U. S.

at 187):

“ There is no general authority to expose the private

affairs of individuals without justification in terms

of the functions of Congress.”

What is true of individuals, we believe, is true of associa

tions; and what is true of Congress is true of all other

agencies of government, Federal and state. Government

may not, without justification, pierce the veil of anonymity.

12 The matter of union secrecy is dealt with in detail in the gov

ernment’s brief amicus curiae in Thomas v. Collins, supra, 1944 Term,

No. 14, pp. 21-31.

It is also worth noting that, despite the large number of state

statutes passed in the last fifteen years substantially restricting union

activities, none requires exposure of membership lists.

34

D. The Place of Anonymity in a Democratic Society

It is important to recognize that there is nothing in

herently wrong in desiring to keep one’s name from the

public. Anonymity has a long and honorable history and

may serve important social objectives. The cause of

civilized progress was greatly benefited by the fact that

Daniel Defoe could publish anonymously his Shortest Way

with the Dissenters, and it was correspondingly greatly

harmed when Defoe’s identity was discovered and he was

fined and pilloried for his offense (Minto, Daniel Defoe

(1909), pp. 38-40).

In this country, even before the founding of our re

public, the practice of speaking anonymously on social and

political matters was accepted as normal and proper.

Benjamin Franklin signed his first pieces for the New

England Courant as “ Silence Dogwood” (Bleyer, Main

Currents in the History of American Journalism (1927),

pp. 56-57). The use of names like “ Philanthrop,” “ Hu-

manus” and “ Cato” as signatures on articles on public

affairs was widespread (Id., pp. 43-100). In 1775, Thomas

Paine used the signature “ Humanus” in an article for

the Pennsylvania Journal; after Rev. William Smith,

president of the University of Philadelphia, used the name

“ Cato” in attacking Paine’s Common Sense, Paine re

plied under the name of “ Forester” (Id., p. 91). The

Neiv Hampshire and Vermont Journal or Farmers Weekly

Museum regularly published articles in the 1790’s written

by such persons as “ The Lay Preacher,” “ Peter Pencil,”

“ Simon Spunkey,” “ Peter Pendulum” and “ The Ped

lar” (Id., p. 128).

The most famous of all American political writings,

The Federalist, written by Alexander Hamilton, James

Madison and John Jay, was published anonymously. In-

35

deed, the attribution of several of the essays is still in

doubt. As Professor Earle points out (The Federalist,

Modern Library edition (1937), Introduction, p. ix), dur

ing the controversy over the endorsement of the Consti

tution, “ The press of the day was submerged with con

tributions from anonymous citizens.” Among those

anonymously opposing ratification was New York’s

Governor George Clinton, who wrote under the name

“ Cato.” (See the introduction by Paul Leicester Ford to

the Henry Holt edition of The Federalist (1898), pp.

xx-xxi.) i | |

Thus, in the early days of our Republic, persons who

were or were to become President of the United States,

Chief Justice of the Supreme Court, Secretary of the

Treasury and Governor of New York did not hesitnte to

maintain their anonymity in publishing weighty public

and political documents.

This practice is still used by public officials. Foreign

Affairs, the United States’ most influential periodical

dealing with international policy, has frequently in recent

years masked the names of its contributors, carrying

leading articles signed simply by single initials, including

the famous “ X ” article, “ The Sources of Soviet Con

duct,” which set forth the Government’s policy towards

the Soviet Union (Foreign Affairs, Vol. 25, Nos. 1 & 4,

Yol. 27, No. 2, Vol. 36, No. 1).

The millions of Americans who are members of secret

fraternal orders certainly believe firmly in their right to

operate anonymously (Schlesinger, op. cit., supra, at p. 44).

Professor Schlesinger describes them as playing a “ pos

itive and continuing role in society” {Id., p. 48).13

13A vigorous warning against the growing tendency to limit pri

vacy and force all our activities into the glare of government super

vision and public inspection is made by Professor Lasswell “ The

Threat to Privacy,” in Maclver, ed., Conflict of Loyalties (1952),

36

E. Anonymity as an Aid to Free Expression

In a number of ways modern society recognizes anonym

ity as a valuable aid in assuring free expression of

opinion. It is standard practice for newspapers to print

letters signed with initials or fictitious names. While the

editors require that the writer disclose his name to them,

they recognize that a freer expression of opinion can be