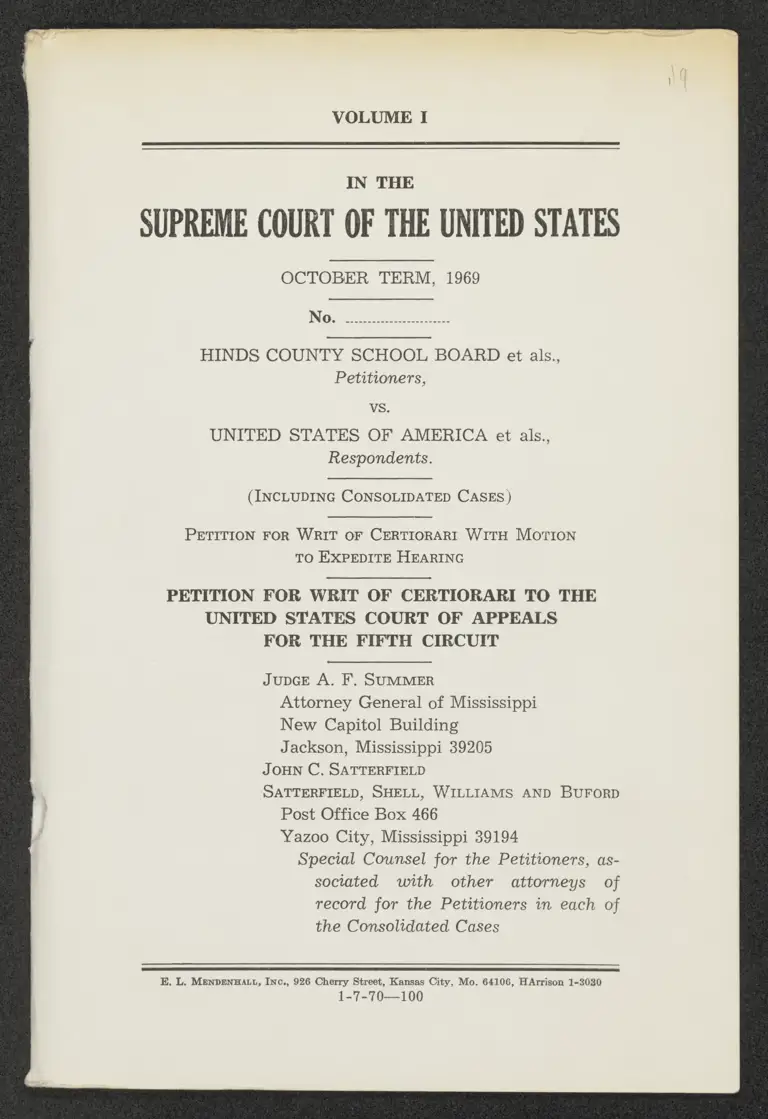

Petition for Writ of Certiorari to the US Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit

Public Court Documents

January 7, 1970

104 pages

Cite this item

-

Case Files, Alexander v. Holmes Hardbacks. Petition for Writ of Certiorari to the US Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit, 1970. 06697d43-cf67-f011-bec2-6045bdd81421. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/3ac67cd0-87b0-4689-9d38-8f7069de1472/petition-for-writ-of-certiorari-to-the-us-court-of-appeals-for-the-fifth-circuit. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

VOLUME I

SUPREME COURT OF THE UNITED STATES

OCTOBER TERM, 1969

HINDS COUNTY SCHOOL BOARD et als.,

Petitioners,

VS.

UNITED STATES OF AMERICA et als.,

Respondents.

(INCLUDING CONSOLIDATED CASES)

PETITION FOR WRIT OF CERTIORARI WITH MOTION

TO EXPEDITE HEARING

PETITION FOR WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE FIFTH CIRCUIT

JUDGE A. F. SUMMER

Attorney General of Mississippi

New Capitol Building

Jackson, Mississippi 39205

JOHN C. SATTERFIELD

SATTERFIELD, SHELL, WILLIAMS AND BUFORD

Post Office Box 466

Yazoo City, Mississippi 39194

Special Counsel for the Petitioners, as-

sociated with other attorneys of

record for the Petitioners in each of

the Consolidated Cases

E. L. MENDENHALL, INC., 926 Cherry Street, Kansas City, Mo. 64106, HArrison 1-3030

1-7-70—100

Volume I

MOTION-TO. ADVANCE ....looovininls wo siisbtidossidlen anemsss

PETITION FOR WRIT OF CERTIORARI ...............

. Judgment and Opinion Below

. Jurisdiction ..

. Questions Presented for Review

A. Constitutional Provisions

. Constitutional Provisions and Statutes Involved

B. Statutes Enacted by Congress under Section

5 of the Fourteenth Amendment to the Con-

stitution of the United States

Argument Amplifying the Reasons Relied On for

Allowance of the Writ of Certiorari ...................

1 The Decision of the Court of Appeals for the

Fifth Circuit Dated November 7, 1969, Mis-

construed and Improperly Implemented the

Decision of This Court Dated October 29,

1069, in Alexander «lh... oso soionenemincavsomeiszemen one

. The Decisions of the Court of Appeals in

These Consolidated Cases Dated November 7,

1969, and July 3, 1969, Conflict with Decisions

of the Court of Appeals of the Sixth Circuit

and the Decisions of the Courts of Appeal of

Other CIirClILs ...... ...ccomnescnmarommsraommessomsssssensuvenns

The Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit in

Its Decisions Dated November 7, 1969, and

July 3, 1969, Respectively, Has Applied Sec-

tion 1 of the Fourteenth Amendment to the

Administration of Public Schools So That It

Conflicts with Green, Raney, Monroe, Carr

anid CGriflin ..........cscosciestormisseniigasisiossassassenonowssabhmmnss

©

OO

CO

O

O

10

14

14

26

II INDEX

4. Section 1 of the Fourteenth Amendment, Con-

strued in Accordance with the “Appropriate

Legislation” Enacted by Congress under Sec-

tion 5 of Such Amendment, Does Not Require

Compulsory Integration of the Public Schools.

It Prohibits Compulsory Segregation Based

Hooh Bagel... in Sd aT

5. A Freedom of Choice Plan Properly Formu-

lated and Administered Fairly and Without

Discrimination, Which Permits Truly Free

and Uninfluenced Choice by Students and

Their Parents, Meets All Constitutional Guar-

antees. The Factors Utilized in the Judgment

of July 3 to Outlaw Freedom of Choice Are

Not Vestiges of the Dual System of Schools ...

6. The Application of a Disparate Rule to School

Systems “in This Circuit” Because of the

Former De Jure Character of the Earlier Sys-

tems Prior to Brown Amounts to a Judicial

Bill of Attainder and Denies Equal Treatment

Before the Law Required by the Constitution

of the Unite] States ol. lus. on bibiinmmms

7. The Petitioners Have Not Been Accorded Due

Process of Law. There Has Been No Hearing

on the Merits by Any Court nor Any Oppor-

tunity for the Litigants to Be Heard on the

Merits Through Their Attorneys ......cccoeee.........

Conclusion” lo. JF Bald dr 0 a ah a

Exhibit 2—Compilation from Reports to Department

of Health, Education and Welfare Described on Page

50 108ithe Pelition cu. omission sriilo iso iol ensibistitoneesn-

Exhibit 3--Chronology of Events .................................

Exhibit 4—Resume of Facts Concerning Four School

LB TS Cn

43

49

52

55

61

64

65

76

79

85

INDEX III

TABLE oF CASES

Adams v. Mathews, (1968) 403 F.2d 181 ......13, 20, 27, 28, 30

Alexander, et als. v. Holmes County Board of Educa-

tion, et als., (Supreme Court Docket Nos. 632 and

RL RA 6,7,13,21

Anthony v. Marshall Cty., (1969) 409 F.2d 1287 ............ 13

Armstrong v. Board of Education of the City of Birming-

hom, 333 W2A AT iii ii lini edi 24

Augustus v. Board of Public Instruction of Escambia

County, Florida, 3068 F.24:862 ...........cc. iit lieetidiness 24

Bell v. Gary, (7th Cir. 1963) 324 F.2d 209, cert. denied

STRODE Yo SRE nl LI Lo CRETE don LR on Sl 13

Broussard v. Houston Independent School District,

(May 30, 1968) 395 F.2d 817, petition for rehearing

en banc denied October 2, 1968, 403 F.2d 34 ........ 13, 43, 52

Brown v. Board of Education, 349 U.S. 294, 75 S.Ct. 753,

89 L.Bd. 1083 (1953) .....c.coccecoccciecenecnneess 12, 22, 23, 43, 44, 48

Brown (II) v. Board of Education, 347 U.S. 483, 74

SCL 0306, 98 1. 0d, 873 ..cveeoiccarrents cinvsiusszssevseesots 12, 23, 44

Bush v. Orleans Parish School Board, et al., 308 F.2d

EE RT OR a SL A RR Ee 24

Carr v. Montgomery Cty., 23 1.Ed.2d 263 ....12, 16,22,23, 40

Clark v. Board of Education, (8th Cir. 1966, 1967) 369

F.2d 661, rehearing denied 374 F.2d 569 ............... 12-13, 45

Cooper v. Aaron, 353 U.S. 1,.3 L.Ed.2d 5 (1958) ............ 12,23

Davis v. Mobile Cty., Nos. 26886, 27491, 27260 (1969)

hon B23 ee ED

Deal v. Cincinnati, (6th Cir. 1966) 369 F.2d 35 _.12, 29, 30, 53

Downs v. Bd. of Ed. of Kansas City, (10th Cir. 1964)

336 F.2d 988, cert. denied 380 U.S. 914, 85 S.Ct. 898,

13 1.8324 800 (1965) rn 12, 46

Duvol Vv. Broxton, (1963) 402 B24 000 .........................-. 13

East Baton Rouge Parish School Board v. Davis, 287 F.2d

EL I Thee Fe Ee Ce ta RN he eo 23

IV INDEX

Freeman v. Gould, (8th Cir. 1969) 405 F.24 1153 ............ 12

Gaines v. Daugherty County Board of Education, 334

Le eG ES a OAL Le Te 24

Goss v. Knoxville, (6th Cir. 1969) 406 F.2d 1133

se JE Ren A EO 12, 23, 30, 45, 53

Graves Vv. Wolton Cty., (1963) 403 F.24 189 ........ ........ 13

Green v. New Kent Co., (U.S. Supr. Ct. 1963) 391 U.S.

430,20 1. Bd.2d 716... 12, 16, 28, 29, 40, 42, 43

Griffin. School Board, 377.U.S. 218 (1964) .................... 36

Hall v. St. Helena, No. 26450 (1969) ....... Pad... 0... 13

Hampton v. Choctaw Cty., No. 27297 (1969) ........ F.2d

Henry v. Clorksdole, (1969) 409 F.24 632 ....................... 13

Hovey v. Elliott, 167 11.5. 40%, 42. 1.04. 415 ................... 99

Louisiana State Board of Education, et al. v. Allen, et al.,

EL EE 0 HR BL sn a 23

Louisiana State Board of Education, et al. v. Angel, et

IAAL Lt I I ER i ee Lh 23

Mapp v. Bd. of Ed. of Chattanooga, Tenn., 373 F.2d 75

BLL Ne EI CL Sa i Sb le 12,53

Monroe v. Board of Commissioners of the City of Jack-

son, Tenn, (1067) 330 F.2d 935... 0. ......... 33

Monroe v. Jackson, Tenn., (U.S. Supr. Ct. 19638) 391

U.S. 450, 20 L..Ed.2d 744 ........ 12, 23, 26, 28, 40, 42, 43, 45, 53

Morgan v. United States, 304 U.S. 13,82 1.E4. 1129 ........ 60

Plessy v. Ferguson, 163 U.S. 537, 16 S.Ct. 1138, 41 L.Ed.

258 (1886)... a 23

Powell v. Alubomu, 287 U.S. 45, 77 1.E4. 138 ................ 60

Raney v. Gould, (U.S. Supr. Ct. 1968) 391 U.S. 433, 20

LT AA eR 12, 23, 28, 40, 42, 43

St. Helena Parish School Board, et al. v. Hall, 287 F.2d

TR RS Ee hE aT WL lL LU 23

Singleton v. Jackson Municipal Separate School Dis-

trict, No. 26285, opinion rendered December 1, 1969 .. 20

Springfield v. Barksdale, (1st Cir. 1965) 348 F.2d 261 .... 12

INDEX V

United States v. Board of Ed., Polk County, 395 F.2d

BO iiiieicccnniicansiiininnss iosieni cms oi Aa dh on citin un tausa is nnonR si russ anes 27

U.S.A. Vv. Baldwin Cty., No. 27281 (1969)......... B24... 13

U.S.A. v. Cook County, (7th Cir. 1969) 404 F.2d 1125

EE SRS RA LA SETA 12, 32, 46

U.S.A. v. Crisp, No. 27445 (1969) ........ F2d. ...... 13

U.S.A. v. Greenwood, (1963) 406 7.24 1036... i. ...... 13

US.A. v. Hinds Cty. Nos. 28030, 23042 (1969) ........

BI ce oe a irr 13,20, 30,:55

U.S.4. v. Indienola, (1969) 410. 1.2d 626. ........50.ccneemm.is 13

U.S.A. v. Jefferson County Board of Education, 372 F.2d

U.S.A. v. Jefferson, 380 F.2Q 385. .....cosexsecss 10, 26, 47, 54, 55, 60

U.S.A. v. Jefferson 111, No. 27444 (1969) ........ Fad... 13

U.S.A. v. Jefferson IV, No. 26584 (1969) ........ Pod... 13

B38 (CA 5, 1008)... conc osiesoise a divesssostsssenss Sieh 26, 27, 47

CONSTITUTIONAL PROVISIONS

AND STATUTES

Constitution of the United States—

Article], § IX, Close J ........c.cuismmnmomisinsmvesnnsossihinumsesbysne 10

Fifth AMENAMBHL .......icceomsnsomnnsesngsssssarpvinsessesstomnisssssrs on 10

Fourteenth Amendment. .........cccoiciim dommes 9,44, 45, 46, 48

Civil Rights Act of 1964—

Section 401 (b) (Public L. 88-352, Title IV, § 401, 78

Stat. 246, Title 42, § 2000c-(b), US.C.A.) ........ 10, 46, 47

Section 407 (Public L. 88-352, Title IV, § 407, 78 Stat.

249, Title 42, 3 2000c-6(a), USCA.) ..........-oee.... 11, 47

Section 410 (Public L. 88-352, Title IV, § 410, 78

Stat. 249, Title 42. $ 2000c-3, USCA) .............. 11, 47

Section 604 (Public L. 88-352, Title VI, § 604, 78 Stat.

253, Title 42. § 20004-3, USCA) .......... 11

Section 702 (Public L. 88-352, Title VII, § 702, 78

Stat. 255, Title 42, £ 2000e-1, USCA.) ................... 11

Public Low 90-557, 82 Sint, 969 ...........cccoreeioeniee..... 12, 47

VI INDEX

Volume II

Appendix A—

Opinion of the Court of Appeals of July 3, 1969 ........ Al

Modification of Order of the Court of Appeals of July

29, 1009 ......onii ie re dn he ses vaas Al0

Letter Directive of the Court of Appeals of June 25,

BOBY vr. icacrrovinsiosinmssaniessivis vermis sos mageis ibs iatonns dant rinsteoiesiansee Al2

Appendix B—

Order of Court of Appeals of November 7, 1969 ........ Al6

Appendix C—

Opinion and Judgment of United States Supreme

Court of: October: 29, .1960..........c.coovccuncncnvoscnnss. A23

Appendix D—

Order of Court of Appeals of October 31, 1969 ............ A25

Appendix E—

Order of Court of Appeals of December 1, 1969 ....... A27

Appendix F—

Proceedings of Pre-Order Conference .........cccconveeernn- A46

Appendix G—

Letter of November 4, 1969 re Proposed Order ........ A58

PLOPOSER OPOBE init r--retielle sions fosiinsoeismsasbasasn sess ams azoasin A60

Appendix H—

Opinion of the District Court Approving Freedom of

Choice Plans... al ee 303

IN THE

SUPREME COURT OF THE UNITED STATES

OCTOBER TERM, 1969

HINDS COUNTY SCHOOL BOARD et als.,

Petitioners,

VS.

UNITED STATES OF AMERICA et als.,

Respondents.

(IncLUDING CONSOLIDATED CASES)

PETITION FOR WRIT OF CERTIORARI WITH MOTION

TO EXPEDITE HEARING

MOTION TO ADVANCE

Petitioners, by their undersigned counsel, move the

Court to advance consideration and disposition of this

case, and in support thereof would show that this case

presents an issue of national importance requiring prompt

resolution by this Court, for the reasons stated in the

annexed petition for writ of certiorari.

2

WHEREFORE, petitioners pray that the Court: 1)

consider this motion without delay; 2) shorten the time

for filing respondents’ response to 15 days; 3) consider

the petition as soon thereafter as possible; and 4) grant

certiorari and summarily reverse the judgment below or

set an expedited briefing schedule and advance the case

on the calendar for argument.

Respectfully submitted,

Junge A. F. SUMMER

Attorney General of Mississippi

New Capitol Building

Jackson, Mississippi 39205

JOHN C. SATTERFIELD

SATTERFIELD, SHELL, WILLIAMS AND BUFORD

Post Office Box 466

Yazoo City, Mississippi 39194

Special Counsel for the Petitioners,

associated with other attorneys of

record for the Petitioners in each of

the Consolidated Cases

PETITION FOR WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE FIFTH CIRCUIT

Petitioners are the defendants and appellees in the

appeals to the Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit con-

solidated under Docket No. 28030 and Docket No. 28042,

which consolidated appeal includes actions pending in the

United States District Court for the Southern District of

Mississippi being entitled and numbered in that Court as

follows: United States of America, Plaintiff-Appellant, v.

Hinds County School Board, et al., Defendants-Appellees

(Civil Action No. 4075(J)); Buford A. Lee, et al., Plain-

tiffs-Appellees, v. United States of America, Defendant-

Appellant, v. Milton Evans, Third Party, Defendant-Ap-

pellee (Civil Action No. 2034(H)); United States of

America, Plaintiff-Appellant, v. Kemper County School

Board, et al., Defendants-Appellees (Civil Action No.

1373 (E)); United States of America, Plaintiff-Appellant,

v. North Pike County Consolidated School District, et al.,

Defendants-Appellees (Civil Action No. 3807 (J)); United

States of America, Plaintiff-Appellant, v. Natchez Special

Municipal Separate School District, et al., Defendants-Ap-

pellees (Civil Action No. 1120(W)); United States of

America, Plaintiff-Appellant, v. Marion County School

District, et al., Defendants-Appellees (Civil Action No.

2178(H)); Joan Anderson, et al., Plaintiffs-Appellants,

United States of America, Plaintiff-Intervenor-Appellant,

v. The Canton Municipal School District, et al., and The

Madison County School District, et al., Defendants-Appel-

lees (Civil Action No. 3700 (J) ); United States of America,

Plaintiff-Appellant, v. South Pike County Consolidated

School District, et al., Defendants-Appellees (Civil Action

No. 3984(J)); Beatrice Alexander, et al., Plaintiffs-Appel-

4

lants, v. Holmes County Board of Education, et al., De-

fendants-Appellees (Civil Action No. 3779(J)); Roy Lee

Harris, et al., Plaintiffs-Appellants, v. The Yazoo County

Board of Education, et al., Defendants-Appellees (Civil

Action No. 1209(W)); John Barnhardt, et al., Plaintiffs-

Appellants, v. Meridian Separate School District, et al.,

Defendants-Appetlees (Civil Action No. 1300 (E)); United

States of America, Plaintiff-Appellant, v. Neshoba County

School District, et al., Defendants-Appellees (Civil Action

No. 1396 (E)); United States of America, Plaintiff-Appel-

lant, v. Noxubee County School District, et al., Defendants-

Appellees (Civil Action No. 1372(E)); United States of

America, Plaintiff-Appellant, v. Lauderdale County School

District, et al., Defendants-Appellees (Civil Action No.

1367 (E) ); Dian Hudson, et al., Plaintiffs-Appellants, United

States of America, Plaintiff-Intervenor-Appellant, v. Leake

County School Board, et al., Defendants-Appellees (Civil

Action No. 3382(J)); United States of America, Plaintiff-

Appellant, v. Columbia Municipal Separate School, et al.,

Defendants-Appellees (Civil Action No. 2199 (H)); United

States of America, Plaintiff-Appellant, v. Amite County

School District, et al., Defendants-Appellees (Civil Action

No. 3983(J)); United States of America, Plaintiff-Appel-

lant, v. Covington County School District, et al., Defend-

ants-Appellees (Civil Action No. 2148 (H) ); United States

of America, Plaintiff-Appellant, v. Lawrence County

School District, et al., Defendants-Appellees (Civil Action

No. 2216 (H)); Jeremiah Blackwell, Jr., et al., Plaintiffs-

Appellants, v. Issaquena County Board of Education, et al.,

Defendants-Appellees (Civil Action No. 1096 (W)); United

States of America, Plaintiff-Appellant, v. Wilkinson County

School District, et al., Defendants-Appellees (Civil Action

No. 1160 (W)); Charles Killinsgworth, et al., Plaintiff-Ap-

pellants, v. The Enterprise Consolidated School District

5)

and Quitman Consolidated School District, Defendants-Ap-

pellees (Civil Action No. 1302(E)); United States of

America, Plaintiff-Appellant, v. Lincoln County School

District, et al., Defendants-Appellees (Civil Action No.

4294(J)); United States of America, Plaintiff-Appellant,

v. Philadelphia Municipal Separate School District, et al.,

Defendants-Appellees (Civil Action No. 1368 (E)); United

States of America, Plaintiff-Appellant, v. Franklin County

School District, et al., Defendants-Appellees (Civil Action

No. 4256 (J)).

The petitioners pray that a Writ of Certiorari issue to

review the judgment of the United States Court of Appeals

for the Fifth Circuit dated and entered on November 7,

1969, and the original judgment dated and entered on July

3, 1969, as modified by such later judgment.

I. JUDGMENT AND OPINION BELOW

The original judgment with the opinion appended

thereto was dated and entered on July 3, 1969, a copy there-

of being attached as Appendix A, page Al. Included there-

with is Letter Directive of the Court of Appeals dated June

25, 1969. Thereafter, judgment was rendered by said court

on November 7, 1969, see copy thereof attached as Appendix

B, page Al16. Neither of said judgments have been re-

ported. Both judgments were entered in all of the twenty-

five cases consolidated in the Court of Appeals as Docket

No. 28,030 and Docket No. 28,042 and listed above.

II. JURISDICTION

The original judgment of the United States Court of

Appeals for the Fifth Circuit was dated and entered July 3,

1969. Opinion and mandate were issued on that date.

Petition for Rehearing in Banc was filed in the said Court

of Appeals in accordance with and within the time limited

6

by the Federal Rules of Appellate Procedure, being filed on

July 16, 1969. Such Petition for Rehearing in Banc was

overruled on October 9, 1969. Such judgment and Petition

for Rehearing in Banc applied to all of the twenty-five

cases as to which this Petition for Writ of Certiorari is filed

and which are captioned as stated above.

This is the first appearance in the Supreme Court of

the United States of any of the parties to sixteen of the

above suits, being all of the above listed actions in which

the United States of America was the only plaintiff-appel-

lant in the lower courts. Nine of the above captioned

cases’ were included in the Writ of Certiorari to the

United States Court of Appeals directed to the amendatory

order dated August 28, 1969, and docketed as Beatrice

Alexander, et als., Petitioners, v. Holmes County Board of

Education, et als., Respondents, No. 632 upon the docket of

the October, 1969, term of this Court. Such petition and

writ affected solely the order dated August 28, 1969, chang-

ing the time table included in the mandate under the opin-

ion and judgment dated July 3, 1969.

On October 29, 1969, this Court entered a judgment

vacating the order of said Court of Appeals dated August

28, 1969, insofar as it affected the nine cases included in

1. The nine cases included in Alexander, Docket Nos. 632

and 713 in this Court, are (District Court docket numbers in-

cluded for clarity): Beatrice Alexander, et als. v. Holmes County

Board of Education, et als. (District Court Docket No. 3779); Joan

Anderson, et als., United States of America v. Canton Municipal

School District, et als., and Madison County School District, et

als. (No. 3700); Roy Lee Harris, et als. v. Yazoo County Board of

Education, et als. (No. 1209); John Barnhardt, et als. v. Meridian

Separate School District, et als. (No. 1300); Dian Hudson, et als.,

United States of America v. Leake County School Board, et als.

(No. 3382); Jeremiah Blackwell, Jr., et als. v. Issaquena County

Board of Education, et als. (No. 1096); Charles Killingsworth,

et als. v. Enterprise Consolidated School District and Quitman

Consolidated School District, (No. 1302); United States of America,

George Magee, Jr. v. North Pike County Consolidated School Dis-

trict, et als. (No. 3807); United States of America, George Williams,

et als. v. Wilkinson County School District, et als. (No. 1160).

7

the writ of certiorari. A copy of the opinion and judgment

of this Court is attached hereto as Appendix C, page A23.

Petition for Rehearing thereof was filed in this Court on

November 22, 1969, and was overruled by this Court on

December 8, 1969.

Upon remand the said Court of Appeals entered an or-

der on October 31, 1969, vacating its order of August 28,

1969, as to all twenty-five of the consolidated cases, a copy

thereof being attached hereto as Appendix D, page A25.

Thereafter on November 7, 1969, the Court of Appeals

for the Fifth Circuit entered an opinion and judgment in

all of the twenty-five consolidated cases, copy of which is

attached hereto as Appendix B, page Al6. Petition for Re-

hearing in Banc by the Court of Appeals for the Fifth

Circuit of said judgment dated November 7, 1969, was filed

on November 20, and was denied by said court on Decem-

ber 5, 1969.

The decision of this Court dated October 29, 1969, in-

volved only “the Court of Appeals’ order of August 28,

1969”, which amended the original judgment of the Court

of Appeals dated July 3, 1969. This Court did not have

before it the original judgment of July 3, 1969, and the order

and mandate of this Court affected only the order dated

August 28, 1969, which changed a schedule of procedure

which had been set up by the Court of Appeals (pp. A23-

A24).

A Cross-Petition for Writ of Certiorari was filed by the

respondents to the Petition in Alexander v. Holmes County

Board of Education, and docketed as No. 713 on the docket

of this Court. It was filed on October 8 when there was

still pending before the Court of Appeals for the Fifth Cir-

cuit Petition for Rehearing in Banc as recited above and

as recited on page 29 of such Cross-Petition for Writ of

Certiorari. As the Petition for Writ of Certiorari in Cause

No. 632 was directed solely to the order dated August 28,

8

1969, and the Petition for Rehearing in Banc of the judg-

ment dated July 3, 1969, was pending, the Cross-Petition

was peremptorily denied by this Court the day after it was

filed under Rule 21(3) and Rule 20 of the Rules of this

Court.

The jurisdiction of this Court is invoked under the pro-

visions of 28 U.S.C. Section 1254 (1).

III. QUESTIONS PRESENTED FOR REVIEW

1. Does the decision of the Court of Appeals for the

Fifth Circuit dated November 7, 1969, properly construe

and implement the decision of this Court dated October 29,

1969, in the nine consolidated cases entitled Beatrice Alex-

ander, et als., Petitioners, vs. Holmes County Board of

Education, et als., Respondents, Docket No. 632 in the Oc-

tober, 1969, term of this Court?

2. Do the decisions of the Court of Appeals for the

Fifth Circuit in these consolidated cases dated November

7, 1969, and July 3, 1969, conflict with the decisions of the

Court of Appeals of the Sixth Circuit and the decisions of

the Courts of Appeals of other Circuits?

3. Has the Court of Appeals of the Fifth Circuit in its

decisions dated November 7, 1969, and July 3, 1969, re-

spectively, applied Section 1 of the Fourteenth Amendment

to the administration of public schools so that it has de-

cided a Federal question in a way which conflicts with

applicable decisions of this Court, or so as to determine

important questions of Federal law which have not been,

but should be, settled by this Court?

4. Does Section 1 of the Fourteenth Amendment, con-

strued in accordance with the “appropriate legislation” en-

acted by Congress under the provisions of Section 5 of such

Amendment, require compulsory integration of the public

schools?

9

5. Is a freedom of choice plan a proper vehicle to set

up and maintain schools conforming to all constitutional

guarantees, where such plan is properly formulated, com-

plies with all requirements laid down by the courts, is ad-

ministered fairly and without discrimination, and which

permits truly free and uninfluenced choice by students and

their parents? If so, what are the vestiges of a dual system

which must be eradicated in order to maintain a freedom

of choice plan?

6. Does the application of a disparate rule to school

systems “in this Circuit” because of the former de jure

character of the early systems prior to Brown amount to a

judicial Bill of Attainder or ex post facto law or does it

deny equal treatment before the law required by the Con-

stitution of the United States?

7. Have each of the petitioners been accorded due

process of law as required by the Fifth Amendment to the

Constitution of the United States by the rendition of the

judgment dated July 3, 1969, and the rendition of the judg-

ment dated November 7, 1969?

IV. CONSTITUTIONAL PROVISIONS AND

STATUTES INVOLVED

The following are the constitutional provisions and

statutes involved:

A. Constitutional Provisions

Fourteenth Amendment to the Constitution of the United

States:

Section 1. All persons born or naturalized in the

United States, and subject to the jurisdiction thereof,

are citizens of the United States and of the State

wherein they reside. No State shall make or enforce

any law which shall abridge the privileges or im-

munities of citizens of the United States; nor shall any

10

State deprive any person of life, liberty, or property,

without due process of law; nor deny to any person

within its jurisdiction the equal protection of the laws.

Section 5. The Congress shall have power to enforce,

by appropriate legislation, the provisions of this ar-

ticle.

Fifth Amendment to the Constitution of the United States:

No person shall be held to answer for a capital, or other-

wise infamous crime, unless on a presentment or in-

dictment of a Grand Jury, except in cases arising in

the land or naval forces, or in the Militia, when in

actual service in time of War or public danger; nor

shall any person be subject for the same offense to be

twice put in jeopardy of life or limb; nor shall be com-

pelled in any Criminal Case to be a witness against

himself, nor be deprived of life, liberty, or property,

without due process of law; nor shall private property

be taken for public use, without just compensation.

Article I, § IX, Clause 3 of the Constitution of the United

States:

3. No Bill of Attainder or ex post facto Law shall be

passed.

B. Statutes Enacted by Congress under Section 5 of the

Fourteenth Amendment to the Constitution of the

United States

Civil Rights Act of 1964, Subchapter IV.

Public Education

Section 401 (b) of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, being

Public L. 88-352, Title IV, § 401, July 2, 1964, 78 Stat. 246,

and appearing as Title 42, Section 2000c-(b), U.S.C.A.:

“Desegregation’” means the assignment of students to

public schools and within such schools without regard

to their race, color, religion, or national origin, but

“desegregation” shall not mean the assignment of stu-

dents to public schools in order to overcome racial

imbalance.

11

Section 410 of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, being

Public L. 88-352, Title IV, § 410, July 2, 1964, 78 Stat. 249,

and appearing as Title 42, Section 2000c-9, U.S.C.A.:

Nothing in this subchapter shall prohibit classification

and assignment for reasons other than race, color, re-

ligion, or national origin.

Section 407 of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, being Pub.

L. 88-352, Title IV, § 407, July 2, 1964, 78 Stat. 249, ap-

pearing as Title 42, Section 2000c-6 (a), U.S.C.A.:

. . . provided that nothing herein shall empower any

official or court of the United States to issue any

order seeking to achieve a racial balance in any school

by requiring the transportation of pupils or students

from one school to another or one school district to

another in order to achieve such racial balance or other-

wise enlarge the existing power of the court to insure

compliance with constitutional standards.

Civil Rights Act of 1964, Subchapter V.

Federally Assisted Programs

Section 604 of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, being

Pub. L. 88-352, Title VI, § 604, July 2, 1964, 78 Stat. 253,

and appearing as Title 42, § 2000d-3, U.S.C.A.:

Nothing contained in this subchapter shall be con-

strued to authorize action under this subchapter by

any department or agency with respect to any em-

ployment practice of any employer, employment

agency, or labor organization except where a primary

objective of the Federal financial assistance is to pro-

vide employment.

Civil Rights Act of 1964, Subchapter VI.

Equal Employment Opportunities

Section 702 of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, being Pub.

L. 88-352, Title VII, § 702, July 2, 1964, 78 Stat. 255, and

appearing as Title 42, Section 2000e-1, U.S.C.A.:

12

This subchapter shall not apply to an employer with

respect to the employment of aliens outside any State,

or to a religious corporation, association, or society

with respect to the employment of individuals of a

particular religion to perform work connected with

the carrying on by such corporation, association, or

society of its religious activities or to an educational

institution with respect to the employment of indi-

viduals to perform work connected with the educa-

tional activities of such institution.

Public Law 90-557, 82 Stat. 969, Which Includes

the Appropriation for the Departments of Health,

Education, and Welfare and Labor

The section relating to elementary and secondary edu-

cation contains the following prohibition:

No part of the funds contained in this Act may be

used to force bussing of students, abolishment of any

school or to force any student attending any elementary

or secondary school to attend a particular school

against the choice of his or her parents or parent in

order to overcome racial imbalance.

For the convenience of the Court we list references

to the several decisions of this Court and other courts

which will be referred to from time to time by name? All

2. Green V. New Kent Co., (U.S. Supr.. Ct. 1968) 391 U.S.

430, 20 1.Ed.2d 716; Monroe v. Jackson, Tenn., (U.S. Supr. Ct.

1968) 391 U.S. 450, 20 L.Ed.2d 744; Raney Vv. Gould, (U.S. Supr.

Ct. 1968) 391 U.S. 433, 20 L.Ed.2d 727; Brown v. Board of Educa-

tion, 349 U.S. 294, 75 S.Ct. 753, 99 L.Ed. 1083 (1955); Brown (II)

Vv. Bd. of .Ed., 347 U.S, 483, 74 S.Ct. 6386, 93 L.Ed. 373; Corr Vv.

Montgomery Cty., 23 L.Ed.2d 263; Cooper v. Aaron, 358 U.S. 1,

3 L.BEd.2d 5 (1953).

Goss v. Knoxville, (6th Cir. 1969) 406 F.2d 1183; Freeman V.

Gould, (8th Cir. 1969) 405 F.2d 1153; U.S.4. Vv. Cook County, (7th

Cir. 1969) 404 F.2d 1125; Deal v. Cincinnati, (6th Cir. 1966) 369

F.2d 35; Springfield v. Barksdale, (1st Cir. 1965) 348 F.24 261;

Downs v. Bd. of Ed. of Kansas City, 336 F.2d 988 (10th Cir. 1964),

cert. denied 380 U.S. 914, 85 S.Ct. 898, 13 L.Ed.2d 800 (1965);

Mapp Vv. Bd. of Ed. of Chattanooga, Tenn., 373 F.24 75 (1967);

Clark v. Board of Education, (8th Cir. 1966, 1967) 369 F.2d 661,

13

emphasis in this petition is ours unless otherwise indicated.

This Petition for Writ of Certiorari is filed in two vol-

umes, the appendices including decisions and opinions of

this Court, the Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit and

the District Court here, together with certain pertinent

proceedings in these causes, being bound separately as

Volume II of this Petition. There are on file with the

Clerk of this Court forty printed copies of Volume II of

the Response to Petition for Writ of Certiorari in nine of

these cases docketed as Cause No. 632, Alexander v. Holmes

County Board of Education, and the Cross-Petition for

Writ of Certiorari in such proceeding docketed as Cause

No. 713. To avoid prolixity and for the convenience of

the Court, said Volume II containing Appendices 1 through

rehearing denied 374 F.2d 569; Bell v. Gary, (7th Cir. 1963) 324

F.2d 209, cert. denied 377 U.S. 924; Broussard v. Houston Independ-

ent School District, May 30, 1968, 395 F.2d 817, Petition for Re-

hearing en banc (in the light of Green, Monroe and Raney) denied

October 2, 1968, 403 F.2d 34.

Adams v. Mathews, No. 26545, August 20, 1968, Judges Wisdom,

Goldberg and Morgan, 403 F.2d 181; Duval v. Braxton, No. 25479,

August 29, 1968, Judges Wisdom, Coleman and Rubin, 402 F.2d

900; Graves v. Walton Cty., No. 26452, September 24, 1968, Judges

Wisdom, Goldberg and Morgan, 403 F.2d 189; U.S.A. v. Greenwood,

No. 25714, February 4, 1969, Judges Brown, Thornberry and Tay-

lor, 406 F.2d 1086; Henry v. Clarksdale, No. 23255, March 6, 1969,

Judges Wisdom, Thornberry and Cox, 409 F.2d 682; U.S.A. v.

Indianola, No. 25655, April 11, 1969, Judges Dyer, Simpson and

Cabot, 410 F.2d 626; Anthony v. Marshall Cty., No. 26432, April

15, 1969, Judges Ainsworth, Simpson and Mitchell, 409 F.2d 1287;

Hall v. St. Helena, No. 26450, May 28, 1969, Judges Brown, God-

bold and Cabot; ........ P24 .....; Davis v.:- Mobile Cty., Nos. 2638386,

27491, 27260, June 3, 1969, Judges Brown, Dyer and Hunter, ________

B24 2. ; USA. Vv. Jefferson I11, No. 27444, June 26, 1969, Judges

Bell, Goldberg and Atkins, ..... Pod. .... : Hampton v. Choctaw

Cty., No. 27297, June 26, 1969, Judges Wisdom, Carswell and

Roberts, tec F.2d fathisy - Choctaw Cty. v. US.A., No. 25639, June

26, 1969, Judges Wisdom, Carswell and Roberts, lke EF 2d’ ee

USA. v. Jefferson IV, No. 26584, July 1, 1969, Judges Wisdom,

Bell and Godbold, ...... E24... 7 S.A. Hinds Cty., Nos. 28030,

28042, July 3, 1969, Judges Brown, Thornberry and Morgan, os

2d... lls 3A v Crisp, No. 27446, July 3, 1969, Judges Wisdom,

Morgan and Davis, ....... F.2d : U.S.A. v. Baldwin Cty., No.

27281, July 9, 1969, Judges Wisdom, Carswell and Roberts,

F248 -......s

14

4 is made a part hereof by reference. In directing the

Court’s attention to the original appendices thus filed, the

references will be “Orig. App. p. -....-.. 2

V. ARGUMENT AMPLIFYING THE REASONS

RELIED ON FOR ALLOWANCE OF THE

WRIT OF CERTIORARI

1. The Decision of the Court of Appeals for the Fifth

Circuit Dated November 7, 1969, Misconstrued and

Improperly Implemented the Decision of This Court

Dated October 29, 1969, in Alexander.

The Per Curiam order of this Court dated October 29,

1969, attached as Appendix C, page A23, granted a very

broad discretion to the Court of Appeals for the Fifth Cir-

cuit. Such discretion is stated as follows, p. A24:

The Court of Appeals may in its discretion direct the

schools here involved to accept all or any part of the

August 11, 1969, recommendations of the Department

of Health, Education and Welfare, with any modifica-

tions which that court deems proper. . ..

The clause which further describes this broad discretion

is as follows:

. . insofar as those recommendations insure a totally

unitary school system for all eligible pupils without

regard to race or color.

In the prior paragraph this Court directed the Court of Ap-

peals to issue its decree and order, effective immediately,

declaring that these school districts:

(a) ...no longer operate a dual school system based

on race or color, and

(b) . . . begin immediately to operate as unitary

school systems within which no person is to be ef-

fectively excluded from any school because of race or

color.

15

This Court did not, in this particular order, define a

“dual school system based on race or color”. It did define

a unitary school system as being one “within which no per-

son is to be effectively excluded from any school because

of race or color”. :

It is crystal clear that the Court of Appeals had the

authority to require the schools to accept any part of the

August 11, 1969, recommendations of HEW. It is also

crystal clear that any part put into effect might be “with

any modifications which the Court may deem proper”.

We feel it is inescapable that this Court would not have

referred to “any part” nor authorized “any modifications

which the Court may deem proper” if it had been intended

to prohibit the Court of Appeals from using only a part of

a HEW plan. This would include the use of alternate

steps, although they may have been called “interim steps”.

A terminal plan may go into effect immediately, at once,

now, today, whether it includes one or two or more steps.

The Per Curiam order either overlooked the fact that

the HEW plans had never been considered by any court

nor had any hearing been held concerning them by any

court, or assumed that the Court of Appeals would provide

due process of law. It granted this additional discretion, p.

A24:

The Court of Appeals may make its determination and

enter its order without further arguments or submis-

sions.

The Per Curiam order further provided that while the

school systems were being operated as unitary systems un-

der the order entered by the Court of Appeals, p. A24:

. . . the District Court may hear and consider objec-

tions thereto or proposed amendments thereof, pro-

vided, however, that the Court of Appeals’ order shall

16

be complied with in all respects while the District

Court considers such objections or amendments, if any

are made. No amendment shall become effective be-

fore being passed upon by the Court of Appeals.

The Court of Appeals misconstrued and misapplied the

Per Curiam order, holding (a) that the order required it to

enter the full HEW final and permanent plans without per-

mitting any alternate or interim steps except in the case of

three school districts; (b) that “meaningful and immedi-

ate progress toward disestablishing state-imposed segre-

gation” is not enough—complete compulsory integration

must be effectuated in a matter of weeks; (c) that such

action be taken without permitting any judicial hearing

of any kind either of evidence or argument on the merits

or submission of briefs; (d) that no modifications to the

plans nor hearing thereasto should be held by the District

Court “before March 1, 1970, and any such suggestion or

request shall contemplate an effective date of September,

1970”, pp. A20-A21.

One problem here had its genesis in the interpretation

placed upon words used in Green that a plan “promises”

to work “now”. The construction of Green inherent in the

November 7th order necessarily interprets the word “now”

to mean either something accomplished in the past and ex-

isting today or something to be accomplished today by the

stroke of a pen or by the entry of an order. This construc-

tion is wholly inconsistent with the word, “promises”.

It is contradictory to Green, as recognized and rein-

forced by Carr. In Carr the Court said that “as stated in

Green v. County School Board, supra, 391 U.S. at 439:”

It is incumbent upon the school board to establish that

its proposed plan promises meaningful and immediate

progress toward disestablishing state-imposed segre-

gation. It is incumbent upon the district court to

17

weigh that claim in light of the facts at hand and in

light of any alternatives which may be shown as feasi-

ble and more promising in their effectiveness.”

Furthermore, this Court said in Carr that an effort

should be made by the school authorities and the courts to

“expedite the process of moving as rapidly as practical to-

ward the goal of a wholly unitary system of schools, not

divided by race as to either students or faculty”.

The presiding Judge would not permit presentation of

any evidence nor any oral or written argument except for a

few questions concerning relatively minor details of the

plans. At the “pre-order conference” which was held on

Thursday, November 6, after oral notification to attorneys

for the petitioners by telephone and otherwise on Monday,

November 3, the order which had been drafted by the

panel was discussed from the bench. The proceedings

were limited by the presiding Judge as follows:

(p. A46) Ladies and gentlemen, we have called this

pre-order conference today for the purpose of making

some announcements and also to exchange views.

After we make some statements, we want everyone

to feel free to ask questions. We don’t intend to have

any legal arguments, as such, but we do think it would

be well for anyone that has questions, that you feel free

to make such inquiries as you may have. . ..

(p. A47) We have also studied the Supreme Court de-

cision in these cases and we are of the view that ac-

tion is required, and immediate action... .

(p. A48) We have prepared a draft order, it is not a

final Order. We hope to put the Order out tomorrow.

We did not want to put an order out until we had this

conference and we want to tell you generally what is

in the order now so that you will be advised as to

what questions you may wish to pose.

(pp. A48-A49) Now, we are going on then, and we

say to effectuate the conversion of these school systems

18

to unitary school systems within the context of the

Supreme Court order the following things have to be

done and then generally we are putting into effect

in every case, except the ones I will tell you about,

the recommended plan of the Office of Education,

HEW. And that is a permanent plan and not the in-

terim plan.

There appear in this appellate record a copy of each

of the thirty desegregation plans filed on August 11, 1969

by HEW. The Secretary of Health, Education, and Wel-

fare was mot permitted by the Court to withdraw such

plans nor to perfect them. They were put into effect as a

part of the judgment of November 7 without any hearing

in any court, without any opportunity of any testimony by

any party, without any opportunity of argument on the

merits either oral or written by any court at any level of

the federal judicial system.

In order not to burden this Petition, we attach as Ex-

hibit 1 hereto copies of material provisions of typical plans.

With a few minor exceptions, these “plans” were simply

a mathematical calculation of the number of students in

each school with a compulsory assignment of students to

attain as nearly as possible racial balance. The plans re-

quired that this be done either by individual assignment to

attain stated numbers, by pairing of grades, by pairing of

schools, by revisions in transportation (i.e., by bussing)

and, in a few instances, by zoning to obtain a numerical

racial result without regard to geographic location of the

lines. This is doubtless the major reason that the Secre-

tary of Health, Education and Welfare, acting in his official

capacity, contracted that if these plans were put into ef-

fect as drawn they must:

. . surely, in my judgment, produce chaos, confusion

and a catastrophic educational set-back to the 135,700

children, black and white alike, who must look to the

19

222 schools of these 33 Mississippi districts for their only

available educational opportunities.

The November 7 judgment mandated (pp. A19, A22):

No later than December 31, 1969, the pupil attendance

patterns and faculty assignments in each district shall

comply with the respective plans.

These judgments entered by the Court of Appeals con-

flict with the decisions of other Circuits, violate the de-

cisions of this Court, and depart from recognized judicial

precedents by requiring:

(a) Immediate compulsory integration of all teachers

and other staffs to a racial balance by the following pro-

vision in each plan, Exhibit 1, p. 65, infra:

For the 1969-70 school year the district shall assign

the staff described above so that the ratio of Negro

to white teachers in each school, and the ratio of other

staff in each, are substantially the same as each such

ratio is to the teachers and other staff, respectively,

in the entire school system.

(b) Compulsory integration by assignment of stu-

dents through either pairing, zoning or direct assignment

to approach a racial balance as nearly as can be accom-

plished in available facilities, with busing of students in

order to obtain such compulsory integration. This is dem-

onstrated by a mere glance at the “pupil attendance pat-

terns” contained in the “Composite Building Information

Form” attached as a part of Exhibit 1 hereto. The other

plans followed similar patterns.

(c) That freedom of choice be completely outlawed

in every school district, regardless of whether or not such

district had achieved a unitary school system and had

abolished all vestiges of the prior dual school system.

(d) By applying in these cases the rule first proposed

in Jefferson II (but not then implemented) that the Four-

20

teenth Amendment imposes a different and more stringent

duty upon states “in this Circuit” or states formerly main-

taining a de jure segregated school system than that which

it imposes upon states or school systems in which de

facto segregation exists.

(e) That the school boards comply with a “constitu-

tional duty” to balance the races in the schools in con-

formity with some mathematical formula.

(f) That all freedom of choice plans be abolished

(under the dicta first announced in Adams and repeated

in Hinds County) even though such plans are properly

and constitutionally formed and administered if in a school

district (1) there are all-Negro schools, or (2) only a small

fraction of Negroes have enrolled in white schools, or (3)

no substantial integration of faculties and school activities

has taken place, upon the legal assumption that each of

these factors constitutes a vestige of the dual school sys-

tem.

(g) That jurisdiction in these causes shall be divested

from the United States District Court for the Southern

District of Mississippi and vested in the Court of Appeals

for the Fifth Circuit as to all matters and proceedings which

“contemplate an effective date” prior to September, 1970,

and that no pleadings suggesting modifications of any

plans may be filed in such District Court prior to March 1,

1970.

That the Court of Appeals of the Fifth Circuit con-

strued the Per Curiam opinion in Alexander to mandate the

judgment it entered is demonstrated beyond the shadow of

a doubt by that Court’s opinion in the cases heard and dis-

posed of as Singleton v. Jackson Municipal Separate School

District, No. 26285, opinion rendered December 1, 1969, not

yet reported. As such case is now on the docket of this

Court upon Petition for Writ of Certiorari, we will quote

21

extracts from that opinion, demonstrating the erroneous

construction of Alexander by the Court of Appeals (pp. 8,

9, 10, 22 and 23 of the slip opinion):

Following our determination to consider these cases

en banc, the Supreme Court handed down its decision

in Alexander v. Holmes County Board of Education,

1969... Us... ,908Ct........ , 24 L.LEd.2d 19. That

decision supervened all existing authority to the con-

trary...

Because of Alexander v. Holmes County, each of the

cases here, as will be later discussed, must be con-

sidered anew, either in whole or in part, by the dis-

{rict courts... ..

Despite the absence of plans, it will be possible to

merge faculties and staff, transportation, services,

athletics and other extra-curricular activities during

the present school term. . . .

To this end, the district courts are directed to require

the respective school districts, appellees herein, to re-

quest the Office of Education (HEW) to prepare plans

for the merger of the student bodies into unitary sys-

fems. .,"

No. 28407—Bibb County, Georgia

. . . It is sufficient to say that the district court here

has employed bold and imaginative innovations in

its plan which have already resulted in substantial de-

segregation which approaches a unitary system. We

reverse and remand for compliance with the require-

ments of Alexander v. Holmes County and the other

provisions and conditions of this order. . .

No. 27863—Bay County, Florida

This system is operating on a freedom of choice plan.

The plan has produced impressive results but they fall

short of establishing a unitary school system.

22

We reverse and remand for compliance with the re-

quirements of Alexander v. Holmes County and the

other provisions and conditions of this order.

No. 27983—Alachua County, Florida

This is another Florida school district where impres-

sive progress has been made under a freedom of choice

plan. The plan has been implemented by zoning in

the elementary schools in Gainesville (the principal

city in the system) for the current school year. The

results to date and the building plan in progress should

facilitate the conversion to a unitary system.

We reverse and remand for compliance with the re-

quirements of Alexander v. Holmes County and the

other provisions and conditions of this order.

The November 7 judgment violates all the applicable

decisions of this Court from Brown I to this date by di-

vesting the district court of all jurisdiction from the date

of its entry to September 1970.

Such judgment violates Carr, in which this court sus-

tained the order of the district court concerning faculty

integration, for the reason that the racial ratio of one to

six teachers was found to be reasonable and that the

objective of a ratio in each school comparable to the ratio

in the entire school system was not required immediately,

but was set up as a goal to be accomplished as soon as

possible consistent with realistic administration of the

schools.

The Courts have overlooked the fact that “all deliber-

ate speed” was of judicial origin. The Court of Appeals

of the 5th Circuit held as late as 1965 and 1966 that ex-

tension of “freedom of choice” at the rate of four grades a

year resulted in the school district being “fully desegre-

gated”. The record shows that freedom of choice has al-

23

ready been extended to every grade in every school district

here.

We briefly trace the development of the rules laid

down by the Court of Appeals of the Fifth Circuit under

Brown I, Brown II, Cooper, Goss, Watson, Green, Monroe,

Raney, Carr and other cases. It is of vital importance to

remember that “hindsight is better than foresight”. The

Petitioners are urging that there be imposed “a judicial Bill

of Attainder” against school officials throughout the na-

tion and particularly within this Circuit.

Looking back over the years, we see that the over-

ruling of Plessy v. Ferguson, 163 U.S. 537, 16 S.Ct. 1138,

41 L.Ed. 256 (1896), and the myriad of supporting cases

has been broadened rather than narrowed. However, the

Court will take judicial notice of the fact that when there

is a revolutionary departure from Constitutional con-

struction which had been accepted for many generations,

it is reasonable for all citizens to await the gradual develop-

ment of decisional law in order to determine the exact

and true meaning of the broad principles originally an-

nounced.

On February 9, 1981, after Brown I, Brown HU,

Cooper and succeeding cases clarified the new Constitu-

tional principles, a group of cases was decided by the Court

of Appeals of the Fifth Circuit. These cases were St.

Helena Parish School Board, et.al. v. Hall, 287 P.24 376;

East Baton Rouge Parish School Board v. Davis, 287 F.2d

380; Louisiana State Board of Education, et al. v. Allen,

et al., 287 F.2d 32; and Louisiana State Board of Educa-

tion, et al. v. Angel, et al., 287 F.2d 33. These cases enjoined

the school boards from requiring racial segregation in pub-

lic schools but did not set up any time limit or schedule

of “desegregation”.

24

Then on July 24, 1962, the Fifth Circuit handed down

its decision in Augustus v. Board of Public Instruction of

Escambia County, Florida, 306 F.2d 862. In that decision

the Court found that the Board must amend its plan to

provide for one grade per year desegregation.

Again in August of 1962 the Court of Appeals of the

Fifth Circuit in Bush v. Orleans Parish School Board, et al.,

308 F.2d 491, held that a policy of desegregation of one

grade per year was proper and Constitutionally sufficient.

The District Court had earlier withdrawn an order for

desegregation of the first six grades by the fall of 1962.

The Board presented a long-range plan providing for

a grade a year desegregation and for redistricting of at-

tendance areas in future years. This long-range plan was

approved by the Court.

After approving several plans extending freedom of

choice to one grade each year, on June 18, 1964 the Fifth

Circuit handed down its decision in Armstrong v. Board

of Education of the City of Birmingham, 333 F.2d 47,

where the Court required desegregation to proceed at the

rate of two grades per year so as to accomplish complete

desegregation within six years, i.e., by 1970.

Then on July 31, 1964, the Fifth Circuit again took up

the case of Gaines v. Daugherty County Board of Educa-

tion; the opinion following this consideration is reported

in 334 F.2d 983. As a result of the Calhoun decision by the

Supreme Court, the Fifth Circuit directed the District Court

to enter an order in Gaines requiring immediate total deseg-

regation of vocational schools by giving any pupil the

choice of attending either the formerly Negro or formerly

white vocational school. Freedom of choice for the fall of

1964 for all children in the first, second and twelfth grades

and desegregation in the same manner of two additional

25

grades each year above the second grade and one additional

grade below the twelfth so that total desegregation would

be accomplished in four years.

During the years 1964, 1965, 1966 and 1967, the school

officials throughout the Fifth Circuit were looking to the

Court of Appeals for guidance and direction as to those ac-

tions which should be taken by them in order to be in

obedience to Constitutional principles. Through hindsight,

the Civil Rights activists are attempting to lay all blame

upon these officials for not having not only accomplished

desegregation as now required by the decisions of the

courts, but also for not having brought about many years

ago total integration or mixing of students.

It is both intriguing and alarming to observe the

change in terminology by the Court. At the time of

Brown, the constitutional safeguards were held to prohibit

“racial discrimination by segregation of the races in public

schools”. It was then found desirable to describe the con-

stitutional mandate as requiring “desegregation” of the

schools as distinguished from “compulsory integration”. As

the meanings of words were changed and the objectives

sought were disclosed, the removal of “racial imbalance”

or the attainment of “racial balance” has been changed to

compulsory action by public authorities so that schools and

faculties “are not identifiable as being maintained for mem-

bers of one race” (no consideration is given to the existence

of schools which are “identifiable as being attended by stu-

dents of one race”). Now the true and original meaning

of the term “a mondiscriminatory, unitary school system”

has been changed to mean (in fact if not in words) to

“a wholly racially integrated school system” resulting

from compulsory action by federal, state or local authori-

ties,

26

Finally, we now see the words “compulsory integra-

tion” changed to the word “merger”. Now, to compel ra-

cial integration, to assign students solely on the basis of

race, to remove racial imbalance or to attain racial balance,

is simply to “merge student bodies” or to “merge faculties

and staff’. We can never underestimate the power of

words.

But we must not forget that the use of governmental

force is legal compulsion which destroys the freedom of

those to whom it is applied.

2. The Decisions of the Court of Appeals in These Con-

solidated Cases Dated November 7, 1969, and July 3,

1969, Conflict with Decisions of the Court of Appeals

of the Sixth Circuit and the Decisions of the Courts

of Appeal of Other Circuits.

The decisions of November 7 and July 3 are bottomed

upon rules of law announced but not enforced in Jefferson

I and Jefferson II. The majority opinion in Jefferson I

covers sixty-nine pages of the Federal Reporters. The

majority and concurring opinions in Jefferson II cover four-

teen pages of the Federal Reporter. Because of the ex-

tended discussion of the many constitutional and legal

principles involved, these opinions may be considered “all

things to all men”, as pointed out in the dissenting opin-

ions. The judgments of July 3 and November 7 here have

finally judicially put into effect the construction of Jeffer-

son I by the Court of Appeals of the Sixth Circuit con-

tained in Monroe (decided June 21, 1967):

We are asked to follow United States v. Jefferson

County Board of Education, 372 F.2d 836 (CA 5, 1966),

which seems to hold that the pre-Brown biracial states

must obey a different rule than those which desegre-

gated earlier or never did segregate. This decision

decrees a dramatic writ calling for mandatory im-

mediate integration. . . . But to the extent that United

27

- States v. Jefferson County Board of Education, and the

decisions reviewed therein, are factually analogous and

express a rule of law contrary to our view herein and

in Deal, we respectfully decline to follow them.

The judgments entered here result in complete destruc-

tion of freedom of choice plans. They are also based upon

dicta first appearing in Adams and repeated in the July

3 judgment, page A2:

If in a school district there are still all-Negro schools,

or only a small fraction of Negroes enrolled in white

schools, or no substantial integration of faculties and

school activities then, as a matter of law, the existing

plan fails to meet constitutional standards as estab-

lished in Green

At one stroke the Fifth Circuit set up a test which,

under the Court’s own announcements, automatically out-

laws every freedom of choice system within the Circuit.

In Jefferson I it was held:

In this circuit white students rarely choose to attend

schools identified as Negro schools. (372 F.2d 836,

889).

On April 18, 1968, it was held in United States v.

Board of Ed., Polk County, 395 F.2d 66, 69:

The record here discloses what the courts have pre-

viously commented on, that is it is rare, almost to the

point of nonexistent, that a white child, under a

freedom of choice plan, elects to attend a “predomi-

nantly Negro” school. As this court said in the first

Jefferson case:

“In this circuit white students rarely choose to

attend schools identified as Negro schools. . . .”

Yet on August 20, 1968, only four months later, the

Adams dicta outlawed any freedom of choice plan “if

in a school district there are still all-Negro schools”.

28

Again on September 24, 1968, in Graves the panel

said:

In its opinion of August 20, 1968, this Court noted that,

under Green (and other cases), a plan that provides

for an all-Negro school is unconstitutional.

The entry of these judgments also arises from a misun-

derstanding of what constitutes a dual system of schools

and a misunderstanding of the clause “a unitary nondis-

criminatory school system”.

Through a misconstruction of the “trilogy of cases”,

Green, Monroe and Raney, this panel of the Court of Ap-

peals is now in direct conflict with decisions of other cir-

cuits. The panel in Adams had before it a docket setting

only. Yet, it seized upon numerous elements which were

considered in combination and separated them, so that

each separate element is now made the sine qua non of

continuance of freedom of choice. This is also true in the

varying definitions of what constitute the “vestiges of a

dual school system” that must be removed.

The Court of Appeals of the Sixth Circuit determined

on February 10, 1969, in Goss v. Board of Education of

Knoxville, Tennessee, 406 F.2d 1183, that the elimination

of all-Negro and all-white schools is not a condition pre-

cedent to either the establishment of a unitary, nonracial

school system, or to the continuation of a freedom of choice

plan of desegregation. In the Knoxville system there were

five all-Negro schools and twenty-nine schools having fa-

culties of only one race. It also found that in 1960 the dis-

trict had “a school system completely and de jure segre-

gated both as to students and faculty”. In holding that

the Knoxville school system was constitutionally accept-

able under Green, Raney and Monroe, the Court of Appeals

said:

29

Preliminarily answering question I, it will be sufficient

to say that the fact that there are in Knoxville some

schools which are attended exclusively or predomi-

nantly by Negroes does mot by itself establish that

the defendant Board of Education is violating the con-

stitutional rights of the school children of Knoxville.

Deal v. Cincinnati Bd. of Education, 369 F.2d 55 (6th

Cir. 1966), cert. denied, 389 U.S. 847, 88 S.Ct. 39, 19

L.Ed.2d 114 (1967); Mapp v. Bd. of Education, 373 F.2d

75, 78 (6th Cir. 1967). Neither does the fact that the

faculties of some of the schools are exclusively Negro

prove, by itself, violation of Brown.

The Court then discussed the rule set forth in Green,

including in the statement that the school boards are

“charged with the affirmative duty to take whatever steps

might be necessary to convert to a unitary system in which

racial discrimination would be eliminated root and branch”.

In applying this to the Knoxville District and discussing

its effect, the Court of Appeals of the Sixth Circuit said:

The Court further said that it would be their duty “to

convert to a unitary system in which racial discrim-

ination would be eliminated root and branch.” 391

U.S. at 437-438, 88 S.Ct. at 1694. We are not sure that

we clearly understand the precise intendment of the

phrase “a unitary system in which racial discrimina-

tion would be eliminated,” but express our belief that

Knoxville has a unitary system designed to eliminate

racial discriminaiton.

The Court brushed aside the position that different con-

stitutional principles should be applied to southern states

where there had been in the past de jure segregation as

contrasted to northern states where there had been in the

past de facto segregation. This was of particular impor-

tance as Deal involved formerly de facto segregation and

Goss involved formerly de jure segregation. The Court

said:

30

In Monroe v. Bd. of Commissioners, 380 F.2d 955, 958

(6th Cir. 1967), we expressed our view that the end

product of obedience to Brown I and II need mot be

different in the southern states, where there had been

de jure segregation, from that in morthern states in

which de facto discrimination was a fortuity. Our ob-

servations in that regard were not found invalid by

the Supreme Court’s opinion reversing our Monroe de-

cision. See Monroe v. Board of Commissioners, 391

U.S. 450, 88 S.Ct. 1700, 20 L.Ed.2d 733 (1968).

The constitutional principles thus found to be applica-

ble to both southern states and northern states were

stated by the Sixth Circuit in Deal, cited as supporting au-

thority in Goss. Deal involved the Cincinnati school sys-

tem in which de facto segregation had resulted in heavy

racial imbalance in the schools.® Racial discrimination

may be removed by different methods, including freedom

of choice plans, validly set up, properly administered, with

choices freely exercised without external pressures so that

the plan itself (without regard to the statistical results pro-

duced by choices thereunder) is constitutionally acceptable.

Adams and Hinds County are actually bottomed solely up-

on statistics and are in direct conflict with both Goss and

Deal. In Deal the Sixth Circuit said:

The cases recognize that the calculus of equality is not

limited to the single factor of “balanced schools”;

rather, freedom of choice under the Fourteenth Amend-

ment is a function of many variables which may be

manipulated differently to achieve the same result in

different contexts. . . .

This is in accord with our holding that bare statistical

imbalance alone is not forbidden. There must also be

3. The report of the Cincinnati school system to HEW for the

school year 1968 revealed that of the 106 schools in the Cincinnati

Public School System, forty were composed of students of one

race (i.e, more than 99 per cent negro or 99 per cent white

students), of which thirteen schools were Negro and twenty-

seven schools were white.

31

present a quantum of official discrimination in order

to invoke the protection of the Fourteenth Amend-

ment. ...

Finally, in the one case in which a district court ap-

parently accepted the appellants’ theory of racial

imbalance, Barksdale v. Springfield School Comm.,

237 F.Supp. 543 (D.Mass. 1965), the first Circuit, in

vacating the decision and dismissing the complaint

without prejudice specifically rejected any such as-

serted constitutional right. Springfield School Comm.

v. Barksdale, 348 F.2d 261, 264 (1st Cir. 1965).

These judgments are in direct conflict with Spring-

field School Committee V. Barksdale, 348 F.2d 361, ren-

dered by the Court of Appeals of the First Circuit in 1965.

The district court found that two of the elementary schools

had over 80 percent Negro pupils, that fourteen elementary

schools had no Negro pupils or less than one per cent Negro

pupils, and that the school system was racially imbalanced.

The Court of Appeals said:

Having reached its conclusions, the court ordered the

defendants to submit a plan to correct racial imbal-

ance in the Springfield schools.

The Court vacated the order of the district court and

reversed, stating the constitutional principles as follows:

Certain statements in the opinion, notably that “there

must be no segregated schools,” suggest an absolute

right in the plaintiffs to have what the court found to

be “tantamount to segregation” removed at all costs.

We can accept no such constitutional right. Cf. Bell

v. School City of Gary, 7 Cir., 1963, 324 F.2d 209, cert.

den. 377 U.S. 924, 84 S.Ct. 1223, 12 L.Ed.2d 216; Downs

v. Board of Education, 10 Cir., 1945, 336 F.2d 988, cert.

den. 380 U.S. 914,:85 S.Ct. 393. 13 L.E4A2d 300...

But more fundamentally, when the goal is to equalize

educational opportunity for all students, it would be no

32

better to consider the Negro’s special interests exclu-

sively than it would be to disregard them completely.

These statistically-based decisions conflict with United

States v. Cook County, 404 F.2d 1125, 1135, decided by the

Court of Appeals of the Seventh Circuit on December

17, 1968. The Fifth Circuit has brushed aside good faith.

They require hard and fast statistical results now. To the

contrary, the Court said in Cook County:

There is no hard and fast rule that tells at what point

desegregation of a segregated district or school occurs.

The court in Northcross said the “minimal require-

ments for non-racial schools are geographic zoning,

according to the capacity and facilities of the build-

ings and admission to a school according to residence

as a matter of right.” 333 F.2d at 662. On the other

hand, “The law does not require a maximum of racial

mixing or striking a rational balance accurately re-

flecting the racial composition of the community or

the school population.” United States v. Jefferson

County Board, 372 F.2d 836, 847, n. 5 (5th Cir. 1966)

aff'd en bane, 380 F.2d 385 (5th Cir.), cert. denied,

Cado Parish School Board v. United States, 389 U.S.

840, 88 S.Ct. 67, 19 L.Ed.2d 103 (1967).

By the entry of these judgments there arises a conflict

with the opinion of the United States Court of Appeals for

the Tenth Circuit in Downs v. Board of Education of Kan-

sas City, 336 F.2d 988 (1964), cert. denied 380 U.S. 914,

85 S.Ct. 898, 13 L.Ed.2d 800 (1965). This involved the

public schools of the Kansas City, Kansas, school system,

which was operated on a segregated basis prior to Brown

I. Thereafter the schools were integrated based chiefly up-

on zones and neighborhood school systems including the

right of transfer. The Court held:

There is, to be sure, a racial imbalance in the public

schools of Kansas City. , ..

33

Appellants also contend that even though the Board

may not be pursuing a policy of intentional segrega-

tion, there is still segregation in fact in the school

system and under the principles of Brown v. Board

of Education, supra, the Board has a positive and af-

firmative duty to eliminate segregation in fact as well

as segregation by intention. While there seems to be

authority to support that contention, the better rule is

that although the Fourteenth Amendment prohibits

segregation, it does not command integration of the

races in the public schools and Negro children have

no constitutional right to have white children attend

school with them. (Citing authorities).

See also Mapp v. Board of Education of Chattanooga,

Tennessee, 373 F.2d 75, rendered by the United States

Court of Appeals for the Sixth Circuit. This involved a

school system in which de jure segregation continued until

it was removed by a grade-to-grade extension of a free-

dom of choice plan resulting in “full integration of all

grades in September 1966”. In response to an attack upon

the plan by the plaintiffs, the Court upheld the plan and

said:

To the extent that plaintiffs’ contention is based on

the assumption that the School Board is under a con-

stitutional duty to balance the races in the school sys-

tem in conformity with some mathematical formula,

it is in conflict with our recent decision in Deal v.

Cincinnati Board of Education, 369 F.2d 55 (6th Cir.

1966).

Four months after the rendition of Jefferson II the

Court of Appeals of the Sixth Circuit had before it Monroe

v. Board of Commissioners of the City of Jackson, Tennes-

see, 380 F.2d 955, decided July 21, 1967. This involved

formerly racially segregated de jure school systems. Be-

cause of its significance here, its consideration of Jefferson

I and Jefferson II and its express repudiation of the con-

34

struction thereof later adopted by panels of this Court, we

quote at length from such decision:

Appellants argue that the courts must now, by recon-

sidering the implications of the Brown v. Board of Ed-

ucation decisions in 347 U.S. 483, 74 S.Ct. 686, 98 L.Ed.

873 (1954) and 349 U.S. 294, 75 S.Ct. 753, 99 L.Ed. 1083

(1955), and upon their own evaluation of the com-

mands of the Fourteenth Amendment, require school

authorities to take affirmative steps to eradicate that

racial imbalance in their schools which is the product

of the residential pattern of the Negro and white

neighborhoods. The District Judge’s opinion discusses

pertinent authorities and concludes that the Four-

teenth Amendment did not command compulsory in-

tegration of all of the schools regardless of an honestly

composed unitary neighborhood system and a freedom

of choice plan. We agree with his conclusion. We

have so recently expressed our like view in Deal et al.

v. Cincinnati Board of Education, 369 F.2d 55 (CA 6,

1966), petition for cert. filed, 35 LW 3394 (U.S. May 5,

1967) (No. 1358), that we will not here repeat Chief

Judge Weick’s careful exposition of the relevant law

of this and other circuits. He concluded “We read

Brown as prohibiting only enforced segregation.” 369

F.2d at 60. We are at once aware that we were there

dealing with the Cincinnati schools which had been

desegregated long before Brown, whereas we consider

here Tennessee schools desegregated only after and in

obedience to Brown. We are not persuaded, however,

that we should devise a mathematical rule that will

impose a different and more stringent duty upon states

which, prior to Brown, maintained a de jure biracial

school system, than upon those in which the racial im-

balance in its schools has come about from so-called

de facto segregation—this to be true even though the

current problem be the same in each state.

We are asked to follow United States v. Jefferson

County Board of Education, 372 F.2d 836 (CA 5, 1966),