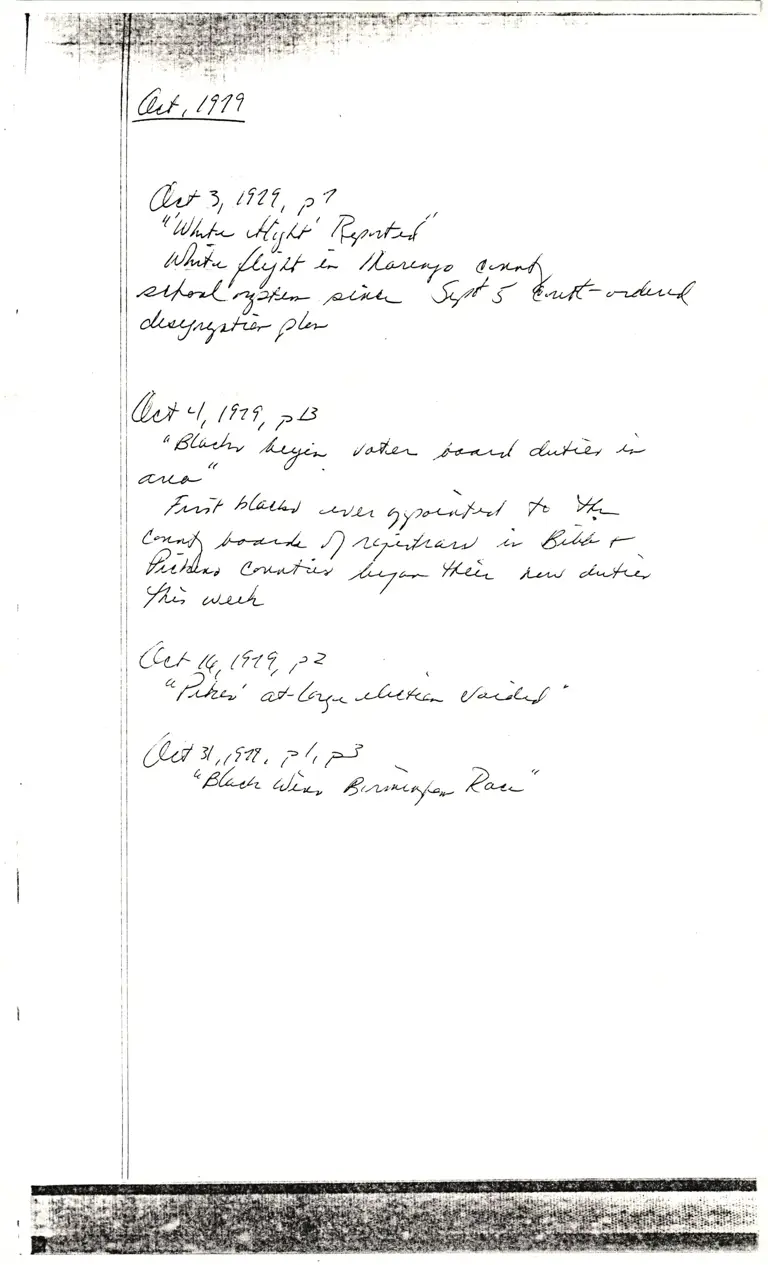

Attorney Notes 3

Working File

October 31, 1979

Cite this item

-

Case Files, Bozeman & Wilder Working Files. Attorney Notes 3, 1979. f3fe10e7-ed92-ee11-be37-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/3adb3c7e-ff2e-4a25-aa62-fc1d617d2e01/attorney-notes-3. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

l,l{l*, -,, 1rzr, p/3

il

a6h;-tA'

% nn''-- dJ'L

il tu*-k"

,14-

,A-""7 ,ob-u*l 2yz*H . /, ?

/.--4 //*-d-^J- O .tr);in4-L/ .zy /frlZ n-

finlL, 0.^r/;; /-,*- //-14 /r4^/ leL

fr; c,t r/2 /

acal 4(( tfz 7 /' z

(

"d4"- a/-LT-. -z/4y',.-* fa)z.l t