Ford v. Wainwright Joint Appendix

Public Court Documents

December 9, 1985

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Ford v. Wainwright Joint Appendix, 1985. ddcfaa1b-b29a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/3b18db7c-d86f-4e67-90a6-8d201b4e71f3/ford-v-wainwright-joint-appendix. Accessed February 22, 2026.

Copied!

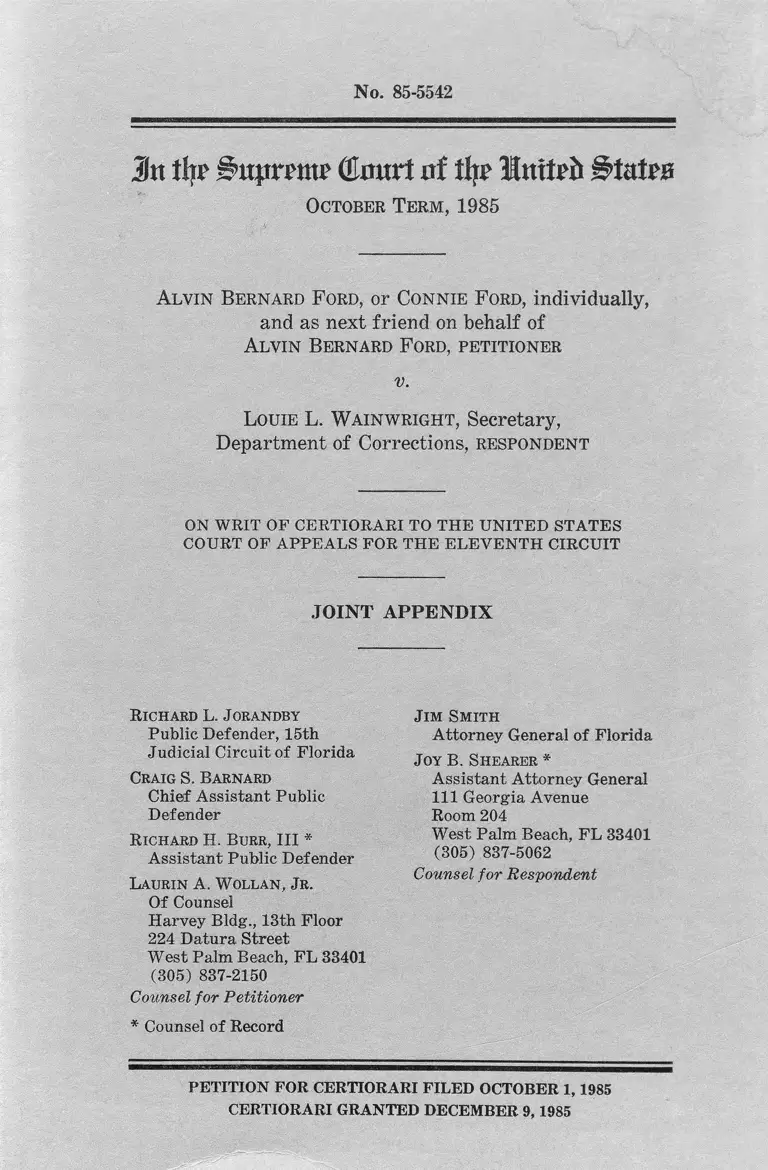

No. 85-5542

Jin tl?i> £nt}trntu' (Emu*! of % l&mtfb Btatw

October Term, 1985

Alvin Bernard F ord, or Connie F ord, individually,

and as next friend on behalf of

Alvin Bernard F ord, petitioner

v.

Louie L. Wainwright, Secretary,

Department of Corrections, respondent

on writ of certiorari to the united states

court of appeals for the eleventh circuit

JOINT APPENDIX

Richard L, J orandby

Public Defender, 15th

Judicial Circuit of Florida

Craig S. Barnard

Chief Assistant Public

Defender

R ichard H. Burr, III *

Assistant Public Defender

Laurin A. Wollan, J r.

Of Counsel

Harvey Bldg., 13th Floor

224 Datura Street

West Palm Beach, FL 33401

(305) 837-2150

Counsel for Petitioner

* Counsel of Record

J im Smith

Attorney General of Florida

J oy B. Shearer *

Assistant Attorney General

111 Georgia Avenue

Room 204

West Palm Beach, FL 33401

(305) 837-5062

Counsel for Respondent

PETITION FOR CERTIORARI FILED OCTOBER 1,1985

CERTIORARI GRANTED DECEMBER 9,1985

TABLE OF CONTENTS

DOCUMENT Page

Relevant Docket Entries in the Courts Below ................. 1

State v. Ford, No. 74-2159 CF, Circuit Court for the

Seventeenth Judicial Circuit of Florida, Order, May

21, 1984 ..................................... 4

Ford v. Wainwright, 451 So.2d 471 (Fla. 1984) ............ 5

Petition for W rit of Habeas Corpus, Ford v. Wain

wright, No. 84-6493-Civ-NCR, United States District

Court for the Southern District of F lorida ................. 11

Excerpts from Appendix to Petition for W rit of Habeas

Corpus in No. 84-6493-Civ-NCR:

Report of Dr. Jamal Amin, June 9, 1983 ................ 87

Report of Dr. Harold Kaufman, December 14,

1983 .................................... ..................... .................. 93

Report of Dr. Peter Ivory, December 20, 1983 ....... 97

Report Dr. Umesh Mhatre, December 28, 1983 __ 102

Report of Dr. Walter Afield, January 19, 1984___ 105

Supplemental Report of Dr. Harold Kaufman, May

24, 1984.................. 107

Affidavit of Dr. Seymour Halleck, May 21, 1984 109

Affidavit of Dr. George Barnard, May 21, 1984 115

Response to Petition for W rit of Habeas Corpus, Ford

v. Wainwright, No, 84-6493-Civ-NCR, United States

District Court for the Southern District of Florida.... 125

Excerpt from Transcript of Hearing before United

States District Court, Ford v. Wainwright, No. 84-

6493-Civ-NCR, May 29, 1984........... .............................. 141

Order of the United States District Court, Ford v. Wain

wright, No. 84-6493-Civ-NCR, May 29, 1984 ....... . 158

Fordv. Strickland, 734 F,2d 538 (11th Cir. 1984) ........ 166

Wainwright v. Ford, 104 S.C't. 3498 (1984) ........... ........ 180

ii

TABLE OF CONTENTS—Continued

DOCUMENT Page

Ford v. Wainwright, 752 F.2d 526 (11th Cir. 1985) ..... 183

Order of the Eleventh Circuit denying rehearing in

Ford v. Wainwright............. 202

Section 922.07, Florida Statutes (1983), as amended

(1985) .............................................. 204

Order of the Supreme Court of the United States grant

ing leave to proceed in forma pauperis and the peti

tion for a w rit of certiorari, December 9, 1985........ 207

RELEVANT DOCKET ENTRIES

IN THE COURTS BELOW

DATE___ PROCEEDINGS

[Circuit Court of the Seventeenth Judicial

Circuit of Florida]

May 21,1984 F IL E D : [Mr. Ford’s] Motion for Hear-

May 21,1984

ing and Appointment of Experts for

Determination of Competency To Be Ex

ecuted, and for Stay of Execution Dur

ing the Pendency Thereof

ORDER denying said motion

May 22,1984 FILED : Notice of Appeal

May 23,1984

[Supreme Court of Florida]

FILED : Brief of Appellant [Ford] or

Application for Extraordinary Relief

May 24,1984 FILED : Answer Brief of Appellee or

Response to Application for Extraor

dinary Relief

May 25,1984 ORAL ARGUMENT

May 25,1984 OPINION denying Mr. Ford’s applica

tion for a hearing to determine com

petency

[United States District Court for the

Southern District of Florida]

May 25,1984 FIL E D : Petition for W rit of Habeas

Corpus

May 25,1984 F IL E D : Response to Petition for W rit

of Habeas Corpus

May 29,1984 HEARING: argument on petition and

request for stay of execution

(1)

2

DATE PROCEEDINGS

May 29,1984 ORDER denying Petition for W rit of

Habeas Corpus and stay of execution

May 29,1984 F IL E D : Notice of Appeal

[United States Court of Appeals

for the Eleventh Circuit]

May 30,1984 ORAL ARGUMENT on Mr. Ford’s ap

plication for stay of execution and for

certificate of probable cause

May 30,1984 ORDER and OPINION granting stay of

execution and certificate of probable

cause

[Supreme Court of the United States]

May 31,1984 F IL E D : Application of the State of

May 31,1984

Florida to Vacate Order of Eleventh Cir

cuit Granting Stay of Execution

FIL E D : Response to Application of

Louie L. W ainwright to Vacate Order of

Eleventh Circuit Granting Stay of Exe

cution

May 31,1984 ORDER denying application to vacate

stay of execution

[United States Court of Appeals

for the Eleventh Circuit]

July 30,1984 F IL E D : Brief for Petitioner-Appellant

August 27,1984 F IL E D : Brief for Respondent-Appellee

September 18,1984 ORAL ARGUMENT

January 17,1985 OPINION affirming the denial of habeas

corpus relief

February 6,1985 F IL E D : Suggestion for Rehearing En

Banc

3

DATE PROCEEDINGS

June 3,1985 ORDER denying rehearing en banc

June 20,1985 ORDER denying stay of mandate and

issuing mandate

[Supreme Court of the United States]

August 20,1985 ORDER extending time to file petition

October 1,1985

for w rit of certiorari

F IL E D : Petition for W rit of Certiorari

October 23,1985 F IL E D : Respondent’s Brief in Oppo

sition to Petition for W rit of Certiorari

October 31,1985 FILED : Motion of National Associa

tion of Criminal Defense Lawyers for

leave to file brief as amicus curiae

October 31,1985 F IL E D : Motion of Office of Capital

Collateral Representative for the State

of Florida, et al. for leave to file brief

as amici curiae

December 9,1985 ORDER granting petition for w rit of

certiorari and motions for leave to> file

briefs as amici curiae

4

IN THE CIRCUIT COURT OF THE

SEVENTEENTH JUDICIAL CIRCUIT

IN AND FOR BROWARD COUNTY, FLORIDA

Case No. 74-2159cf

State of F lorida

vs.

Alvin Bernard F ord, defendant

ORDER

THIS CAUSE having come on before the court upon

the Defendant’s Motion for Hearing and Appointment of

Experts for Determination of Competency to be Executed,

and for Stay of Execution During the Pendency Thereof,

it is hereby

ORDERED AND ADJUDGED that the Defendant’s

motion be and it hereby is Denied.

DONE AND ORDERED in Chambers, Broward

County, Florida, this 21st day of May, 1984.

/%/ John G. Ferris

Circuit Judge

For and at the Direction of:

J. Cail Lee, Circuit Judge

5

SUPREME COURT OF FLORIDA

Nos. 65335, 65343

Alvin Bernard F ord, or Connie F ord, individually, and

acting as next friend on behalf of Alvin Bernard

F ord, petitioner

v.

Louie L. Wainwright, Secretary, Dept, of Corrections,

State of Florida, respondent

Alvin Bernard F ord, etc., appellant

v.

State op F lorida, etc., appellee

May 25, 1984

ADKINS, Justice.

We have before us a petition for habeas corpus and an

application for stay of execution in order to allow a

hearing to determine petitioner’s competency. We have

jurisdiction. Art. V, § 3(b) (7), (9), Fla. Const.

The petitioner was convicted in the Circuit Court of

the Seventeenth Judicial Circuit on December 17, 1974,

for the first-degree murder of a Fort Lauderdale police

officer. The jury recommended death, and the trial court

imposed a sentence of death on January 6, 1975. This

6

Court affirmed petitioner’s conviction and sentence of

death in Ford v. State, 374 So.2d 496 (Fla. 1979), cert,

denied, 445 U.S. 972, 100 S.Ct. 1666, 64 L.Ed.2d 249

(1980).

Petitioner then filed a motion to vacate or set aside the

judgment pursuant to Florida Rule of Criminal Proce

dure 3.850. The circuit court denied the motion, and its

denial was affirmed by this Court. Ford v. State, 407

So.2d 907 (Fla.1981).

Petitioner’s subsequent petition for writ of habeas

corpus was denied by the United States District Court for

the Southern District of Florida. Upon appeal, a divided

panel of the United States Court of Appeals for the

Eleventh Circuit affirmed the district court’s denial of

relief. Ford v. Strickland, 676 F.2d 434 (11th Cir.1982).

Rehearing en banc was granted, and the en banc court

affirmed the district court’s judgment. Ford v. Strickland,

696 F.2d 804 (11th Cir.1983). Certiorari was denied in

Ford v. Strickland, ----- U.S. ------, 104 S.Ct. 201, 78

L.Ed,2d 176 (1983).

Thereafter proceedings to determine petitioner’s mental

competency were instituted pursuant to section 922.07,

Florida Statutes (1983). As required by this statute,

Governor Graham appointed a commission of three psy

chiatrists to evaluate petitioner’s sanity. The reports of

the psychiatrists were submitted to the Governor, and he

signed a death warrant for petitioner on April 30, 1984,

requiring petitioner to be executed between noon on May

25, 1984, and noon on June 1, 1984. Petitioner is cur

rently scheduled to be executed on May 31, 1984.

In addition to the proceedings that were instituted on

behalf of petitioner pursuant to section 922.07, peti

tioner’s counsel also filed a motion in the trial court for a

hearing to determine petitioner’s competency and for a

stay of execution during the pendency thereof. The trial

court denied the motion on May 21, 1984.

Petitioner raises two issues in his petition for writ of

habeas corpus. The first of these concerns a jury instruc

7

tion given to the jury in the sentencing phase that its

advisory verdict of either life imprisonment or death must

be reached by a majority vote of the jury. Specifically,

petitioner argues that intervening law has established

that such an instruction is erroneous, and that but for the

erroneous instruction the jury’s verdict “most probably”

would have been for life imprisonment.

This alleged error occurred during the sentencing pro

ceeding in the trial court and therefore, the explicit pro

scription contained in Florida Rule of Criminal Procedure

3.850 applies here:

An application for writ of habeas corpus in behalf

of a prisoner who is authorized to apply for relief by

motion pursuant to this rule, shall not be entertained

if it appears that the applicant has failed to apply

for relief, by motion, to the court which sentenced

him, or that such court has denied him relief, unless

it also appears that the remedy by motion is inade

quate or ineffective to test the legality of his deten

tion.

In his first motion for post conviction relief in late

1981, petitioner raised other challenges to the instructions

given during the sentencing phase, but did not raise this

issue. Thus, petitioner is not entitled to raise the issue

here. See Johnson v. State, 185 So.2d 466, 467 (Fla.

1966) ; Finley v. State, 394 So.2d 215, 216 (Fla. 1st DCA

1981) ; Darden v. Wainwright, 236 So.2d 139 (Fla. 2d

DCA 1970).

Furthermore, petitioner’s reliance on Rose v. State, 425

So.2d 521 (Fla.), cert, denied,------U.S. -------, 103 S.Ct.

1883, 76 L.Ed.2d 812 (1983), and Harich v. State, 437

So.2d 1082 (Fla.1983), cert, denied, ----- U.S. ------- , 104

S.Ct. 1329, 79 L.Ed.2d 724 (1984), is misplaced. This

Court has recently clarified that the error which peti

tioner alleges here requires an objection at trial before

relief can be granted on direct appeal. See Rembert v.

State, 445 So.2d 337, 340 (Fla.1984) ; Jackson v. State,

8

438 So.2d 4, 6 (Fla.1983). The excerpt from the tran

script of the sentencing phase of petitioner’s trial which

is appended to the instant petition shows that there was

no objection to the instruction in the trial court. Thus,

any alleged error in the contested jury instruction has

been waived by the lack of a contemporaneous objection at

trial, and any relief in this proceeding is precluded by the

well-established rule that habeas corpus may not be used

as a vehicle to raise for the first time issues which could

or should have been raised at trial and on appeal. McCrae

v. Wainwright, 439 So.2d 868, 870 (Fla.), cert, denied,

___ U.S. -------, 103 S.Ct. 2112, 77 L.Ed.2d 315 (1983) ;

Hargrave v. Wainwright, 388 So.2d 1021 (Fla.1980).

Additionally, the instructions given to the jury accu

rately tracked the statute that was in effect at the time

and that remains unchanged. It was a change in the

standard jury instructions which prompted our decision

in Harich. However, this Court has held that the Harich

case does not constitute a change in the law which will

merit relief in a collateral proceeding under the rule of

Witt v. State, 387 So.2d 922 (Fla.), cert, denied, 449 U.S.

1067, 101 S.Ct. 796, 66 L.Ed.2d 612 (1980). Jackson, 438

So.2d at 6.

Moreover, as we held in Harich and Jackson, the record

in this case does not establish that petitioner was prej

udiced by the instructions as delivered. Petitioner at

tempts to construct his claim of prejudice based almost

entirely upon the response by one juror as the jury was

being polled regarding whether the verdict was by a ma

jority vote of the jury, one juror responded: “The second

time it was.” From this response petitioner reasons that

initially a majority of the jury did not vote for the death

penalty, and then builds to a conclusion that “the errone

ous instruction was determinative of the outcome. . . .”

However, it is well known that juries often take an

initial vote to see where the members stand in order to

channel their discussion. The mere fact that a second

vote was taken does not establish anything in this record

9

to indicate that the jury felt compelled to reach a conclu

sion that they would not otherwise have reached. Peti

tioner’s assertion to that fact is based purely upon conjec

ture, but this Court has stated that reversible error can

not be predicated on conjecture. See Sullivan v. State,

303 So.2d 632, 635 (Fla. 1974), cert, denied, 428 U.S.

911, 96 S.Ct. 3226, 49 L.Ed.2d 1220 (1976).

Petitioner’s second claim in this proceeding is that the

death penalty is applied in Florida in an arbitrary and

discriminatory manner on the basis of race, geography,

etc., in violation of the eighth and fourtenth amendments.

This claim has never been raised by petitioner in a motion

for post-conviction relief; therefore, it cannot be raised

for the first time in this original habeas corpus proceed

ing. See Johnson v. State, 185 So.2d 466, 467 (Fla.1966) ;

Finley v. State, 394 So.2d 215, 216 (Fla. 1st DCA 1981) ;

Darden v. Wainwright, 236 So.2d 139 (Fla. 2d DCA

1970). Further, this same issue, based upon the same

data, has been presented to and rejected by this Court in

Sullivan v. State, 441 So.2d 609 (Fla.1983), and most

recently in Adams v. State, 449 So.2d 819 (Fla.1984).

Petitioner concedes as much, but requests that this Court

reconsider its prior holdings on this issue. We decline to

do so.

Petitioner’s counsel has also filed a separate brief in

this proceeding requesting this Court to remand for a

hearing in the circuit court to determine whether peti

tioner is presently insane. Petitioner argues that a sepa

rate judicial determination of sanity must be made apart

from the statutory procedure in section 922.07, Florida

Statutes (1983), which directs the governor to make such

a determination. This is so, petitioner contends, because

Florida has an established common law right to a deter

mination of a prisoner’s competency to be executed. How

ever, when the early Florida decisions held that an appli

cation to the trial court must be made for a determination

of sanity, section 922.07 had not been enacted. It is an

accepted rule of statutory construction that the legislature

10

is presumed to be acquainted with judicial decisions on

the subject concerning which it subsequently enacts a

statute. Main Insurance Co. v. Wiggins, 349 So.2d 638,

642 (Fla. 1st DCA 1977) ; Bermudez v. Florida Power

and Light Co., 433 So.2d 565, 567 (Fla. 3d DCA 1983),

review denied, 444 So.2d 416 (Fla.1984). Thus, the statu

tory procedure is now the exclusive procedure for deter

mining competency to be executed.

In Goode v. Wainwright, 448 So.2d 999 (Fla.1984), we

addressed this issue, agreed “that an insane person cannot

be executed,” and held that section 922.07 sets forth “the

procedure to be followed when a person under sentence of

death appears to be insane. The execution of capital

punishment is an executive function and the legislature

was authorized to prescribe the procedure to be followed

by the governor in the event someone claims to be insane.”

Thus, in Goode we held that under section 922.07 the gov

ernor can make the determination; Goode does not stand

for the proposition that the issue of sanity to be executed

can be raised independently in the state judicial system.

As we recognized in Goode, the United States Supreme

Court in Soleshee v. Balkcom, 339 U.S. 9, 70 S.Ct. 457, 94

L.Ed.2d 604 (1950), has held that a procedure like

Florida’s whereby the governor determines the sanity of

an already convicted defendant does not offend due

process. Like Goode, the petitioner has exercised his right

to use the full processes of the judicial system. Therefore,

Goode is dispositive of the instant case.

Accordingly, petitioner’s application for a hearing to

determine competency and a stay of execution is hereby

denied. The petition for writ of habeas corpus is also

denied.

It is so ordered.

ALDERMAN, C.J., and BOYD, MCDONALD and

EHRLICH, JJ., concur.

11

UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

FOR THE SOUTHERN DISTRICT OF FLORIDA

[Title Omitted in Printing]

PETITION FOR WRIT OF HABEAS CORPUS

BY PERSON IN STATE CUSTODY

To the Honorable Norman C. Roettger, Jr., Judge of

the District Court for the Southern District of Florida.

1. The Circuit Court of the Seventeenth Judicial Cir

cuit, in and for Broward County, Florida entered the

judgment under attack. The Court is located in Fort

Lauderdale, Florida.

2. Mr. Ford entered a plea of not guilty, and a judg

ment thereon was entered on December 7, 1974. After

advisory sentence of death was returned by the jury, the

court entered a death sentence on January 6, 1975.

3. Mr. Ford was sentenced to death by electrocution.

4. Mr. Ford was indicted for first degree murder of

Dimitri Ilyankoff.

5. Mr. Ford entered a plea of not guilty.

6. Mr. Ford’s trial was before a jury.

7. Mr. Ford did not testify at his trial.

8. Mr. Ford appealed his conviction and sentence.

9. The Supreme Court of Florida affirmed the convic

tion and death sentence on July 18, 1979, and denied

rehearing on September 24, 1979. Ford v. State, 374

So.2d 496 (Fla. 1979). Certiorari was denied on April

14, 1980. Ford v. Florida, 445 U.S. 972.

10. Thereafter, Mr. Ford pursued state post-conviction

and federal habeas corpus remedies. His motion for post

conviction relief pursuant to Florida Rule of Criminal

Procedure 3.850 was denied by the Circuit Court in

Broward County, and its denial was affirmed by the

12

Supreme Court of Florida. Ford v. State, 407 So.2d 907

(Fla. 1981). Mr. Ford’s subsequent petition for a writ of

habeas corpus in the United States District Court for the

Southern District of Florida was denied in an unreported

opinion, and Mr. Ford appealed. On April 15, 1982, a

divided panel of the United States Court of Appeals for

the Eleventh Circuit affirmed the district court’s denial

of relief. Ford v. Strickland, 676 F.2d 484 (11th Cir.

1982). Rehearing en banc was granted, and the en banc

court affirmed the district court’s judgment. Ford v.

Strickland, 696 F.2d 804 (11th Cir. 1982). Certiorari

was thereafter denied. Ford v. Strickland, ----- U.S.

------, 104 S.Ct. 201 (1983).

11. On October 20, 1983, the undersigned counsel

invoked the procedures of Fla. Stat. § 922.07 (1983) on

behalf of Mr. Ford. Pursuant to this statute, Governor

Graham appointed a commission of three psychiatrists to

evaluate Mr. Ford’s current sanity in light of the statu

tory standards for determining sanity at the time of

execution. The commission members each thereafter re

ported their findings to Governor Graham, and on April

30, 1984, Governor Graham signed a Death Warrant for

Mr. Ford. No findings were made by Governor Graham

with respect to Mr. Ford’s sanity, but the signing of the

Death Warrant signified that the Governor had concluded

that in his view Mr. Ford was sufficiently sane to be

executed. The Death Warrant signed by Governor

Graham permits the execution of Mr. Ford during the

week beginning noon, Friday, May 25, 1984, and ending

noon, Friday, June 1, 1984. The Superintendent of Flor

ida State Prison has scheduled Mr. Ford’s execution for

Thursday, May 31, 1984, at 7 :Q0 a.m.

12. On May 21, 1984, a “motion for a hearing and

appointment of experts for determination of competency

to be executed, and for a stay of execution during the

pendency thereof” together with a supporting memoran

dum of law and an appendix containing documentation of

Mr. Ford’s present incompetency was filed in the state

trial court on behalf of Mr. Ford. The motion set out in

13

detail the facts relating to Mr. Ford’s mental status and

was certified under oath to be made in good faith by the

undersigned counsel. Because of his mental condition, the

motion was presented by Mr. Ford’s mother, Connie Ford,

individually and as next friend to her son Alvin Bernard

Ford. Connie Ford’s affidavit setting forth next friend

allegations was attached to the motion. Within four hours

of filing the motion, memorandum, and appendix and

although the trial judge was out of town, the judge denied

the motion without findings:

This cause having come before the Court upon the

defendant’s Motion for Hearing and Appointment of

Experts for Determination of Competency to Be

Executed and for Stay of Execution During the

Pendency thereof, it is hereby

ORDERED AND ADJUDGED that the defendant’s

motion is Denied.

DONE AND ORDERED in Chambers at Broward

County, Florida this 21st day of May, 1984.

13. Review of the lower court’s order was sought in

the Supreme Court of Florida by the filing of a notice of

appeal on May 22, 1984 and the filing of a brief or appli

cation for extraordinary relief on May 23, 1984. Oral

argument was heard on May 25, 1984. On May —, 1984

the Supreme Court denied relief. Ford v. S ta te ,----- So.

2d ----- , No. — (Fla. 1984).

14. In addition to the aforementioned action, Mr. Ford

also filed an original petition for writ of habeas corpus

in the Supreme Court of Florida on May 22, 1984. This

petition was denied by the opinion of May —, 1984.

Next Friend Allegations

15. Movant, CONNIE FORD, is the mother of Alvin

Bernard Ford, who is presently incarcerated on death row

at Florida State Prison and is scheduled to be executed on

May 31, 1984, at 7 :00 a.m.

14

16. Mrs. Ford brings the present proceeding individ

ually and acting as next friend on behalf of her son,

because he is presently incompetent and is incapable of

maintaining the proceedings himself, or of protecting his

own right not to be subjected to the execution of his death

sentence when he is incompetent.

17. Mrs. Ford alleges the following facts and incor

porates the averments in her attached affidavit (Attach

ment A) in support of her status as next friend acting on

behalf of Alvin Bernard Ford in this litigation:

A. Until sometime during the first six months of 1982,

Alvin Bernard Ford suffered from no mental illness or

disorder known to Mrs. Ford. However, sometime during

this period in 1982, Alvin Ford began to develop a serious

mental illness or disorder which, in the intervening time,

has become so severe that he no longer is competent to

protect his own legal interests, to understand why he is to

be executed, or to assist himself in the face of his impend

ing execution.

B. As demonstrated in Attachment A, during the

period of time since the summer of 1982, Alvin Ford has

grown increasingly distant from his mother and his

family. At the same time, he has begun having delusions

about the relationship between himself and his family and

about what he is experiencing and is capable of carrying

out while he is incarcerated on death row. In particular,

Mr. Ford has come to believe that he has the power to

communicate with persons outside prison through various

devices such as radios and has the power to know what is

happening in the world outside the prison by his own

mental and perceptual powers. Because of his exercise of

these powers, Mr. Ford has come to believe that his family

and numerous other persons are being held hostage in

Florida State Prison. As his illness has worsened, Mr.

Ford has maintained these and other delusions but has

also begun to feel he has the power to resolve the crises

which face him. Accordingly, Mr. Ford has indicated that

he has taken care of the corruption which caused the hos

15

tage crisis and has, in the course of recent months,

married ten women upon whom he is relying for finan

cial support.

C. During the course of Mr. Ford’s deterioration over

the past two years, Mrs. Ford’s contact with her son has

led her to the conclusion that he is unable to understand

and appreciate the reality of his incarceration on death

row and his impending execution.

18. Accordingly, Mrs. Ford believes that her son is

incapable of protecting his rights as those rights must

now be exercised, and she thus asserts his rights upon

his behalf as his next friend.

Grounds Upon Which Habeas Corpus Relief

Should Be Granted

Introduction

Since Mr. Ford has previously filed a petition for a

writ of habeas corpus, the petition now before the Court

is a “successive” or subsequent” petition, However, this

fact alone does not permit the Court to decline to enter

tain the merits of the grounds presented. Only if the

Court finds in addition (1) that a ground or the grounds

raised herein were raised in the first petition and were

at that time adjudicated on the merits, and the ends of

justice would not be served by reconsideration of such

grounds; or (2) that although a ground or the grounds

raised herein were not raised in the first petition, the

failure to raise the grounds in the first petition consti

tuted abuse of the writ, see Sanders v. United States,

373 U.S. 1 (1963); Potts v. Zant, 638 F.2d 727 (5th

Cir. 1981), can the Court decline to entertain the merits

of the grounds presented.

Because the “abuse of the writ” doctrine has been so

broadly applied in recent cases, see, e.g., Sullivan v.

Wainwright, 721 F.2d 316 (11th Cir. 1983); Goode v.

Wainwright, ----- F.2d ------ (11th Cir. April 4, 1984)

(No. 84-3224), it is crucial that the Court carefully

analyze Mr. Ford’s position that none of the three grounds

he presents herein can be dismissed under that doctrine

16

or the related “prior adjudication on the merits” doc

trine. For this reason, Mr. Ford has filed a separate

memorandum along with the petition in which he fully

demonstrates why these doctrines do not apply. As set

forth in full in the separate memorandum, the doctrines

do not apply to the first ground (U 19, infra) because

that ground was not previously raised; and further, be

cause the facts in support of the ground were not in

existence at the time the first, petition was filed, the

failure to raise the ground cannot be deemed an abuse of

the writ. The doctrines do not apply to the second

ground (Tf 20, infra), because that ground was not pre

viously raised, and because the law in support of the

ground did not support the assertion of that ground at

the time the first petition was filed. Finally, the doc

trines do not apply to the third ground (U 21 infra),

because that ground as well was not previously raised;

further, because the statistical evidence necessary to sup

port the ground was not in existence at the time the

first petition was filed, the failure to raise the ground

cannot be deemed an abuse of the writ.

Accordingly, for these reasons—as fully documented

and supported in the separate memorandum directed to

the “abuse” issue-—the Court cannot decline to entertain

the merits upon “abuse of the writ” or related doctrines.

The Grounds for Relief

19. At the present time, Mr. Ford is mentally incompe

tent and his execution would thus violate the eighth

amendment’s proscription against cruel and punishment

and the fourteenth amendment’s guarantee of substan

tive and procedural due process of law.

A. Mr. Ford is presently severely psychotic. Counsel

believes that Mr. Ford is so psychotic that he no longer

has the capacity to understand his execution—i.e., the

nature and effect of execution and why he is to be exe

cuted—or to communicate to counsel any fact heretofore

not communicated which would make his execution unjust

17

or unlawful, While the facts material to the question of

Mr. Ford's competency are set forth in detail infra.

a summary of these facts at the outset is helpful in

order to help the Court understand the process of Mr.

Ford’s deterioration which has led to the instant action.

(1) Mr. Ford’s current illness has been the result of

a process of deterioration for more than two years. Until

late December 1981 or early January, 1982, Mr. Ford

seemed to be in relatively good mental health. However,

since that time Mr. Ford has gradually developed what

has become by now grossly debilitating psychosis, Mr.

Ford began having delusions in early 1982. Thereafter,

as his delusions took hold, some auditory and olfactory

hallucinations began accompanying the delusions. Grad

ually the delusions took over his entire conscious exist

ence. The delusions centered on his belief that the Ku

Klux Klan was holding his family and other people

hostage in Florida State Prison in order to drive him

to commit suicide. By the summer of 1983 Mr. Ford’s

delusions seemed to have changed somewhat. He seemed

to have gained the power to free the hostages, to fire

and prosecute the officers responsible, and to replace the

justices of the Florida Supreme Court. At one point he

referred to himself as Pope John Paul III. Thereafter,

Mr. Ford’s mental processes began to make “less sense”

to those of us in communication with him. He began

speaking in such a disjointed fashion that, while phrases

could be understood, no sensible communication could be

had. At some point during this time, Mr. Ford began to

believe that he had won his case and that the state could

no longer execute him. He seemed amused that the state

might “try” to execute him anyway. By December of

1983, however, Mr. Ford seemed no longer able to com

municate at all by the same words and syntax that inform

conventional modes of communication. There has been no

apparent improvement in his mental status since De

cember, 1983.

18

(2) Through much of the time that Mr. Ford has

been ill, he has periodically refused to meet with his

lawyers. When the current death warrant was signed,

we were in the midst of such a period. Mr. Ford had

refused to see us since mid-December, 1983. While he

still refuses to see us, we have obtained information,

recounted infra, which confirms that Mr. Ford’s mental

health is today no better—and is probably worse*—than it

was when we were last with him on December 19, 1983.

B. The facts concerning Mr. Ford which must be taken

into account in connection with the motion sub judice

come from six sources: testimony in his tria l; his written

correspondence over the last two-and-one-half years; a

series of psychiatric interviews and evaluations of Mr.

Ford by Dr. Jamal Amin, from July, 1981 through

August, 1982; a psychiatric interview and evaluation of

Mr. Ford by Dr. Harold Kaufman on November 3, 1983;

an interview with Mr. Ford by his attorney Laurin

Wollan and paralegals Gail Rowland and Margaret

Vandiver on December 15, 1983; the interview with

Mr. Ford on December 19, 1983 by the commission of

three psychiatrists appointed by the Governor pursuant

to Fla. Stat § 922.07; and the facts reported about Mr.

Ford’s mental state at the present time. The facts pre

sented by these sources are set forth in the pages that

follow.

Mr. Ford’s Correspondence

C. During Mr. Ford’s period of incarceration on

death row, he has been a prolific correspondent—with

his attorneys, his family, his friends, his newly-developed

(sometimes by correspondence only) acquaintances. His

letters reveal a very bright, caring, principled person

who is concerned not only about the events in his l i f e -

pertaining to his case and to the conditions and treat

ment of prisoners at Florida State Prison—but also

about the events in the lives of the people with whom,

he corresponds and the major events that shape the lives

19

of people collectively. His letters also reveal, and dra

matically document, his gradual decline into the serious

mental illness from which he now suffers. Because

Mr. Ford has spent so much of his time writing and has

written so articulately, his letters thus provide an extraor

dinary window into his mental and emotional state and

how it has changed over recent years. Accordingly, they

are a unique source of material facts which show the

gradual but unrelenting deterioration of Mr. Ford’s

mental health, and of equal importance, which show that

Mr. Ford’s illness is genuine, not merely a contrivance

to avoid his fate.

D. Prior to December 5, 1981, Mr. Ford’s letters re

vealed a seemingly healthy, “normal” human being. For

example, on August 7, 1981, he wrote to Gail Rowland,

a staff member of the Florida Clearinghouse on Criminal

Justice (who served as a paralegal on his case and in the

course of her work with Mr. Ford became a close and

trusted friend), as follows:

Dear Rowland:

Content in knowing you and members of the Clear

inghouse, had a safe trip to and back, from South

Carolina. Relieved to know, we are still friends.

Well I wasn’t sure, after, all I’ve said, but it was

only the truth.

Yea, I did receive your letter explaining you and

members of the Clearinghouse, would be in a week

of meetings, in South Carolina. You should have

gotten, my last letter, showing I understood, you

would be busy.

Content in knowing the meetings went well. I can

understand your missing your family, happy you’re

home. Also, and you were able, to be at the beach.

Will be looking forward, to seeing you. I’m still not

sure, about some things, especially if I should write,

about what happens, inside the Prison Walls. Think

20

I’m more lazy, than anything else, think a lot of

times, how easy this would be, if I had a tape re

corder. I still stress, the point. No one, should read

anything I write, about the Prison. I’m still not

sure, if I should, though. Hope to talk to you, if I

feel better about this. I may have started, but I

won’t promise.

Well you need a car, if you don’t have one. Do be

sure to inform me, when you think you’ll be back at

Florida State Prison. I am not unreasonable, even if

I seem, so.

Haven’t received any word, on the Parole Commis

sion Interview of 31 July 81, from relatives, but will

inform you, as soon as I do. My sister had men

tioned, talking with Wollan, by phone earlier, in

July. I’m sure the interview had them, somewhat,

not knowing what to think.

Thanks for sending the Amnesty Newsletter, back.

I will most likely write Williamson, sometime soon.

Will truly be content, in seeing this summer end.

Hope those days are over, wherein it was near or

over 100°.

Know you’ll be busy, at home as well as work. Hope

you’ll be able to visit your family in New York, in

December.

You are a good friend, so stay in touch. Will think

about writing about some of the things we discussed.

So take care.

Sincerely, Alvin B. Ford.

Appendix I (submitted herewith), Letters, A. Another,

longer letter, dated August 31, 1981, to Gail Rowland

was quite sim ilar-sharing Mr. Ford’s feelings about

various events in his life, discussing the stresses and the

boredom of life on death row, expressing his concern for

21

various friends and acquaintances, and mentioning his

fondness for Dr. Jamal Amin, who was conducting an on

going psychiatric evaluation for use in Mr. Ford’s clem

ency and post-clemency proceedings. Appendix I, Let

ters, B. Again several months later, on December 1,

1981, three weeks after Mr. Ford’s death warrant had

been signed and less than one week before his scheduled

execution, Mr. Ford wrote Gail Rowland a letter typical

of all his correspondence to that point—expressing his

gratitude for the hard work people were putting into

his legal efforts, his special gratitude for Ms. Rowland

and her daughter, and his happiness that Ms. Rowland

had a good Thanksgiving holiday. Appendix I, Letters, C.

E. On December 5, 1981, however, health and nor

malcy began to give way. The first sign of Mr. Ford’s

break with reality appeared: he wrote in a letter to Ms.

Rowland on this date that the staff of a radio station in

Jacksonville, WJAX-FM (often referred to by Mr. Ford

as “95X”), “have been talking to me, the pass few

weeks,” not by visiting in person or on the telephone,

but in their broadcasts.

Dear Rowland:

Thought I would write about WJAX, and the staff

at 95X-FM, who I had informed you, have been

talking to me, the pass few weeks.

I wrote and informed them, their names will go in

my file, so send Fins Esq, Hill Esq., a copy of this

letter. Plus send Hill Esq. a copy of the letters,

concerning death watch.

Well a friend Clyde Holmes, use to call 95X

(WJAX) and ask Otis Gamble to play different

songs for me. This went on for months.

I would tell Holmes, to give Otis Gamble a message

(he calls himself, “the Greatest,” the name I gave

him, but usually Gambini) which would be, a mes

sage in a joking manner.

22

Then Gambini would get on the radio, and tell me,

what he would do to me, by his being 6’4”, and 230

pounds. So I would send a message I lift 400 pounds,

easy. So this is how it started.

Then the guy who does the news, Scott, would get

on and talk about 400 pounds. So for whatever, I

had sent the message, they would let me know, they

got the message. All this was in kidding.

I never wrote the radio station until a few days after

the death warrant was signed. This guy Scott got

on the radio, and was asking could I talk, “What’s

the matter with you, you can’t talk,” so I wrote.

From the time prison officials gave me the radio,

Scott has been selling out, so much so. I couldn’t let

him get the last word in. So Scott and Gambini, has

kept me laughing.

The guards know, they talk to me over the radio.

Scott gets on the radio 5:30 A.M. in the mornings,

and says, “is he up, wake him up,” and the guard

wakes me up, and I say, “Damn Scott is talking that

crazy shit, this early in the morning.”

The lady who does the news, Peggy, kids me because

I kid her. Then while doing the weather, tell me no

good news. She calls Bob Graham, the “gritch”

(spell wrong) that stole X-mas. They tell me, all

sorts of stories. Funny ones.

Then there’s a lady name Destiny. Who takes over

where they leave off, she said her name was Gail

Adams, the other night.

The people at the radio station has really, made the

situation more easier. They told me good luck, be

fore the hearing Friday. Peggy, the newslady, said

she hadn’t heard anything about 5:00 P.M., asked

had I one day I could hear them, turning the pages

23

of the newspaper, someone would ask, “any good

news,” the other, “I don’t see anything.”

They the four people have said, so much over the

radio, to me. They told me it was (11) secretaries

typing the weekend the after the hearing was denied

in Fort Lauderdale, and so many other things I can’t

even begin to write.

So I thought I would like in the file, they were

special people to me. They say, they will be with me,

until 8 December 81. So I would like to have this

in the file, if ever its read, by others.

Thank you, Alvin B. Ford.

Appendix I, Letters, D.

F. In a letter to Ms. Rowland nearly three months

later, February 24, 1982, Mr. Ford again discussed his

developing relationship with the staff of WJAX. In the

intervening period since the December 5 letter, it is clear

that Mr. Ford’s delusional relationship with WJAX had

become much more complex and more central to his on

going life. Moreover, this letter introduced what was to

become an overriding obsession: Mr. Ford’s preoccupa

tion with, and personal battle against the Ku Klux Klan.

Dear Rowland:

The leader of the Jacksonville NAACP was on the

noon news, on Channel 4 (of Jacksonville) 23 Febru

ary 82.

He asked that on one, show up at the Klan rally 25

February 82. The Klan will feel real strange.

On 21 February 82, I sent the radio station the

article that was in the February 82 issue of Match

box (Amnesty International). Also an article on

this lady from Ireland, who won the Nobel Peace

Prize, five years ago.

24

Candy Markman of Nashville, Tenn., mailed the arti

cles, or article her father writes sometimes. He lives

in St. Petersburg, Florida.

Mailed the article to Big “0 ” (Otis Gamble). That’s

what I call him. I saw him on television once. He

runs the opinion line. So guess I’ll start back writ

ing.

I don’t think Jacksonville, is ready to know, I’ve been

writing most of the topics for the opinion line.

All except for three programs, this month. The

reason, missed two this week, because I told the staff,

at the radio station, I wouldn’t be around this week,

to hear the people call, and talk of hate, for the

Klan, and people because of the races.

Destiny was crying Monday night. Guess Big “0 ”

showed her the picture by Doug Magee, of the Gas

Chamber.

I have a plan, in this opinion line, if the station

keeps using the ideas which leads to votes, and gun

control. But it will take months of the opinion

line. . . .

Will be in touch.

Sincerely, Alvin B. Ford.

Appendix I, Letters, E.

G. By February 28, 1982, just four days later, Mr.

Ford’s delusional system had taken a quantum leap. On

February 25, 1982, two events occurred in Jacksonville

which took on extraordinary significance for Mr. Ford:

the Ku Klux Klan held a rally; and fire destroyed the

house and lives of a black family, killing the father and

six children and leaving only the mother alive, because

she was pushed out a window by her husband to run for

help. In a very long letter to “Destiny,” one of the staff

25

members of WJAX, Mr. Ford explained the significance

and interrelationship between these two events—i.e., the

Klan started the fire—and explained how God had re

vealed these facts to him. Because this delusion is of

central importance to the subsequent development of Mr.

Ford’s delusional system, and because the way in which

Mr. Ford reports having discovered that the Klan started

the fire is so revealing of his increasingly psychotic state

—in which delusions, loosening of associations and

hallucinations are manifest1—the letter is reproduced

here in substantial part.

Destiny:

Please read my letter of 24 February 82, again.

Then make copies, of both, that letter, and this one.

Then I want Ed Austin, to read the letter of 24

February 82. Also this letter. Make him a copy

of both. I’ll need him at the end of this letter. I

always call him, Ed.

The letter of 24 February 82, was a thought, ques

tion, answer, letter in a sense. I will just go over it.

1 See American Psychiatric Association, Diagnostic and Statisti

cal Manual (Third Edition, 1980), a t 182-183 [excerpted in rele

vant part in Appendix I submitted herewith] [hereafter referred

to as “DSM-1I1” ]. See also the definitions of these term s:

“Delusions” are “false personal belief[s] based upon incorrect in

ferences about external reality [which are] firmly sustained in

spite of what almost everyone else believes and in spite of what

constitutes incontrovertible and obvious proof or evidence to the

contrary.” DSM-III, a t 356.

“Loosening of associations” is a form of “ [t]hinking characterized

by speech in which ideas shift from one subject to another that is

completely unrelated or only obliquely related without the speaker’s

showing any awareness that the topics are unconnected.” DSM-III,

a t 362.

“Hallucinations” are “sensory perception[s] without external stim

ulation of the relevant sensory organ.” DSM-III, a t 359.

26

Now that you have read that letter of 24 February

82.

I didn’t get the 25 February 82, newspaper, Florida

Times Union. So guess something was in there.

Then have the feeling, more people are waiting for

this letter, than in the pass.

Even heard Reagan over 95X talking about the light

by the plant. That light, is something I can only see

it, when he is ready. I’m waiting on it now. Have

saw many things, and didn’t start understanding

until the newscast 4:20 P.M. by Peggy 95X FM, on

25 February 82.

There’s times when I write about things, as to when,

or what date, they will happen. If I can’t see the

light from the sun, I’m lost. Then it’s not the sun,

someone much Stronger. Those who read this letter

will see the light I’m talking about, and know, this

is the light, I see by, when he wants me to, I have

no control, it’s only when he wants me to see. I

I never forget, what has happened this pass week, to

ten days.

I was very content in hearing, the leader of the

Jacksonville, NAACP (on Channel 4) ask that no

form of protest be given to the Klan Rally 25 Feb

ruary 82. (This was aired 23 February 82, on Chan

nel 4 noon).

I wondered how the Klan members would feel, with

no one, there to hate. Also was content, some tele

vision stations, showed little coverage of the Klan

members, up until 25 February 82.

Was more concerned, as to, how the young students

and children, would react, to such hate. I learned

about love, and people, in my own way, and had the

27

best teacher. Everyone, will see that teacher, who

reads, this letter.

The light, that shines, through the window, to the

floor, you’ll see it, it’s in the light. It’s no one, but

God. That’s how, I see things, in the outside world.

It may seem strange, but he, is much powerful, than

any of us have ever, conceived, or rather much more

powerful, than any man, ever conceived.

He showed me, the past seven days, and I will tell

you how. It really frightens me, once I begin to

remember.

This all started, when Destiny asked, if I knew her

age, 95X, the night of 24 February 82. Then asked

how, I knew, there was a living plant, in the room,

(at her apartment) with the Bird.

I informed her, the light was shining, on the floor,

she must have turned, and saw the light while on the

phone, when she called the radio station, 95X, that

morning. Guess she didn’t know, he was there, in the

light. Don’t know, the reason, for her calling, but

that’s why he was there (God). That’s how, I saw

the plant. She is a special Friend. As all the mem

bers of the staff at 95X.

In the 24 February 82, letter, I tried, to explain, to

Destiny about the light, without mentioning God,

was the light, because he knows, I know. Already.

In my trying to explain, I mentioned a few things.

As how sometimes, I can see things, days, sometimes

weeks ahead, of time. There’s times, when I’m

wrong. That’s God’s, not with me, or rather I’m

not with God, because he, is always there.

4:20 P.M. 25 February 82, Peggy’s first news story

was of the Klan rally. But she sound, so frightened,

28

I’ll never forget the cold chill, I got as if she was

talking to Death, itself, her voice never has ever

sound, so frightening, and chilling.

During the second story on the fire (the man and

six children) I saw three black images, standing

behind her, in or black images as the outline of

someone, in the Klan hood and gown. The chill was

so cold, that it frightened me.

After the newscast, I thought of the letter of 24

February 82 and somehow, just hoped, Peggy wasn’t

afraid of me. I didn’t understand what had hap

pened, until later that evening about 6:00 P.M.

matter of fact, I didn’t understand what had hap

pened, until about 6:00 P.M. 25 February 82 (Fri

day), and still didn’t know, everything, until I saw

the sunlight, the morning of 27 February 82, with

Sandy.

He showed me everything, and left something, so

you’ll know how great he is. He only let me look in

the window once, I wanted to look again, but he said

it’s there. Soon you’ll see what I saw, and know.

I know the Klan members, burned that house.

Rather than tell someone, what I was thinking, I

wrote 95X, and asked Peggy to let me know, if she,

hear the news, on the cause of the fire. The morn

ing of 25 February 82.

Watched the 6:00 P.M. news on Channel 4, then

saw the faces of the Klan members, who, burned the

house (on pages eleven and twelve). [Mr. Ford is

here referring to * * * two newspaper articles, * * *.]

They were Bill Wilkson, the leader, Robert McMul

len, and the Klan member, with the reddish brown

beard (holding the two signs) with the wood part

29

in his hand. That’s in the 6:00 P.M. Channel 4,

newscast, 28 February 82.

I was wondering, who I could inform. But I see now,

someone’s waiting on this letter.

Peggy made some type of noise, in her throat, while

mentioning, the gun law, had pass, as stated in the

28 February 82, paper, and letter of 24 February 82.

This made me take a closer look at everything. As

far as what I had written, in the letter of 24 Feb

ruary 82, and what had happen.

* * * *

I sat down and looked at that picture on page twelve

[the picture reported in the Florida Times Union

edition of February 26, 1982, supra], and went over

it many times. I saw the man, Robert McMullen,

pouring something on the roof of the house on page

twelve. The man with the reddish beard, through

fire, in the first window on the corner of the house,

where the meter is, it’s marked (X).

There was a man inside the house, this is why “the

little girl, said the house frightened her.”

The man pushed the lady out the window, nearest

to the meter, so she get help, and she called God.

As I did, after seeing, all this. I asked God to help

me, with the light, I had saw, by the plant because,

the investigators couldn’t find the evidence.

Then the sunlight, arrived, in the window, by the

meter, I saw something in the ashes, I still don’t

know the name of it, because seemed, as one corner,

was in the ashes, I wanted, to move it, but couldn’t

touch, it, to get a better look, it looked like this:

[Drawings Omitted in Printing]

30

The brown picture, is the first one I put on paper,

so I wouldn’t forget what I saw. This was the only

thing, I saw with the light through the window.

I didn’t know, what either of the pictures, on page

fifteen [the diagrams, supra] was, because it looked

silver, around the edges, and black engrave, with

one edge in the ashes, covered, looked as though.

I looked and looked, this is the only thing that looks

close to it. (on page seventeen) [Mr. Ford is re

ferring here to page seventeen of his letter, which

contains the picture of the Klan member, infra.]

Turn the drawing on page fifteen [diagrams, supra],

see how it fits, there’s only one thing missing, the

last corner (as in the house on page twelve).

The lady in the newscast, 6:00 P.M., on Channel 4,

is the other corner.

The evidence, is in the path, of the light, on the

floor mark the path of the light, from the window

on the floor.

I only saw in the window once, and would like to

see, what the window, showed.

He said, the lady, in the blond or with the blond

hair, who was in the Klan outfit, go get her (only)

for now.

* * * *

Then let her read the letters, of 24 February 82,

Then take her to the house, to see what God left, as

his mark. Then give her the money, and make sure,

she is safe, and free to go, wherever she wish to go.

She will see the light, also, and she will continue

to, until she does the right thing. That will be the

only way she can stop his power.

31

I don’t know you, but saw you at the Klan Rally,

pretty blonde hair. God, will be talking to you, so

don’t be afraid. Be still listen, and think, that’s

how he talks, when you see the light, look at it,

spinning, on the floor.

Look at your feet, when you get inside, he will make

you remember, standing right at the fourth end of

the picture you saw, I saw the light through the

same window.

The lady, pushed through the window, called God,

as the house was burning, and he answered. I don’t

know what you’ll see inside that house, when you

get there.

But don’t be afraid, you will see what I saw, through

the window, but you’ll see the light God only allowed

me to look in the window on page twelve once.

Ed Austin, you may know me, I met you in the

Fourth Judicial Circuit, Nassau County, Fernandina

Beach, in 1980.

You remember, in the case of the young white kid,

who killed the convenient store worker. Judge

Adams, I know you fear God, this five days pass, I

learned, how great he is.

He said, give you a copy of this letter, and get one

of the 24 February 82. Then know, he is God, writ

ing this, for me.

He said, go get the lady, in the Klan outfit, and

bring her back alone. Her picture is in the Channel

4 newscast 6:00 P.M., 25 February 82. Blonde hair.

Let her read the letters, then take her to the house,

and let her, see his mark.

To tell you the truth, I wanted to see it again, but

I’m frightened of the glow.

32

I don’t know, what you’ll see, but God help you.

He also said, to mark the area, whatever it is he

wants you to see, also. So be there early, and wait

on him, he will come in the window, by the meter,

slowly in the light.

Whatever is there, no matter what, they are to look,

and mark the light. I saw something, in the ashes,

in the light, looks like on page fifteen (the drawing).

He said, to tell you to look at the light, as it comes

through the window, then come back, when the lines

are marked, from the light on the floor, from the

windows.

Then know, she went for his help. Also, no matter,

what’s there, go get the girl (blond hair, Klan gown)

and let her read these letters. Then take her to the

house. He will do the rest.

He said, give her the money, and make sure, she

is safe, and give her, a little time, to think, after

she, see whatever, he left there in the house. Also

make sure she is free to go.

God bless the staff at 95X, and those who saw this,

work of God.

Sherlock.

[“Sherlock” is Mr. Ford’s nickname in the prison.]

Appendix I, Letters, F.

H. During the month that followed the writing of

this letter, Mr. Ford seemed to return to a relatively

healthier state. His loosening of associations and hal

lucinations, so clearly evident in the February 28 letter,

seemed to have subsided. As evidenced in his letters to

Gail Rowland of March 8, 9, and 13, 1982 (Appendix I,

Letters, G, H, and I), Mr. Ford continued to believe his

delusion about the Ku Klux Klan—e.g., “ [t]he letters

33

concerning the Klan has bothered me some what, because

I want the Grand-Wizard” (Appendix I, Letter, G)— and

his delusion about his ability to interact with the WJAX

staff, but he also seemed to be communicating in the

“normal” style and about the “normal” subjects he for

merly wrote about.

I. Mr. Ford continued to communicate in this fashion

until April 17, 1982, when a letter to Ms. Rowland on

that date showed some further advance in his delusional

systems, accompanied by the injection of paranoia into his

delusions as well as the re-emergence of his loosening of

associations. In the first half of this letter, Mr. Ford

wrote matter of factly and “normally” about Ms. Row

land’s family and associates, the decision by the panel

of the United States Court of Appeals in his case, and

an upcoming meeting with one of his attorneys. Then

abruptly, he wrote:

I saw Graham on television, with water in his eyes,

talking about that letter I sent the lady D-Miami,

with the words, unlined. Wait until you read the

letters, Destiny has at WJAX.

The people at the radio station, Destiny, has in

formation, on some things that happen, the follow

ing day, after I had written her. I haven’t been

writing for their opinion line, because trying to keep

up, with the Ku Klux Klan, has gotten me tired.

Thank you for nice Easter card. I have stop writ

ing about anything, as to when or where, it will

happen, because this whole thing, leaves me very

tired, and the people at the radio station, keep asking

for more, when I haven’t rest.

Haven’t wrote Candy Markman’s father, yet because

the talk about war, scares me. So I just stop, writ

34

ing anyone, who may seem to ask some strange or

unusual question.

I have to see what Destiny has done, with all the

letters. Doug Magee [a writer from New York who

has published books about death row] is at that radio

station saying his name is Dale Taylor. I haven’t

received a letter, from him, so I’m about ready to

stop writing that station.

Well hope to see you soon. Think I’ll just rest some.

Tell Geoff and Tao [Ms. Rowland’s husband and

child] hello for me. I don’t know much about the

book, but whatever, I write, I don’t plan on sending

to WJAX, until I find out, what happened to the

other things I have written so far.

So take care, and hope to see you soon.

Sincerely, Alvin B. Ford.

Appendix I, Letters, J.

J. Over the next three months, Mr. Ford again seemed

to have “gotten better,” as evidenced in his letters. Ap

pendix I, Letters, K and L. To be sure, his delusion about

the Ku Klux Klan remained intact, and he reported

devoting much effort to seeing that Bill Wilkinson (the

leader of the Klan) would eventually be prosecuted and

convicted for the arson-murders in Jacksonville. He also

took care to be sure that Ms. Rowland and her colleague,

Scharlette Holdman, knew about what he was doing and

understood the “evidence” he had against the Klan. And

his concern for his “Klan work” was so pervasive that he

reported little concern about anything else, even the legal

proceedings related to his conviction and sentence:

I have the briefs from the lawyers, Burr III and

Fins Esq. I’ve been so busy I haven’t had the chance

to read them, but will this weekend. I don’t worry

too much about the ruling that will be from the 11th

35

Circuit, on the rehearing. Have many other things

to keep me busy.

Appendix I, Letters, L. However, he also was able to

communicate about everyday matters concerned with his

and Gail Rowland’s friendship, Appendix I, Letters, K,

and his manner of writing was more coherent, reflecting

another remission of his loosening of associations.

K. By July 8, 1982, Mr. Ford’s remission ended. On

that date, he wrote Scharlette Holdman (Florida Clear

inghouse on Criminal Justice) a letter reporting a sig

nificant advance in his delusional system: he had just

discovered that Gail Rowland was “Destiny,” and he

wanted to know why she had been trying to fool him

for the many months she had been seeing him.

Dear Holdman:

As soon as, you have time, do reply to this letter.

I’ve been writing WJAX some time now, to an

A/K/A Destiny.

Most recently I found out she is Gail Rowland. This

is because she mentioned, something, I told her, in

prison, at the prison, during a visit.

A while back this Martin, was sending me messages,

threatening to kill her. So I asked Angela [news

person from Channel 4, Jacksonville] to ask Ed

Austin to put a wire tap on her phone, and watch

her home. This fraud case came, up. The police,

was looking for Martin. I wrote Angela and told

her he was more than likely at Destiny’s. This where,

police, picked him up, the following morning.

Gail Rowland, has, been writing from this address.

Granda Apartments, 2131 North Meridian Road.

Apartment #111, Tallahassee, Florida 32303.

19 June 82 there was a wedding. I put Gail Row

land’s name on the letter, sent it to Channel 4.

36

The reason I think she (Destiny) is in fact Gail

Rowland, is she mentioned some things, I have told

her in prison. Now to the serious part. Destiny

has been playing games, with me, for three months.

Most recently, threats.

I’ve been so angry, I had the thought in mind of

hurting another prisoner. Seriously, I couldn’t be

lieve this was Gail Rowland.

Haven’t had a reply, from her, in quite a while. I

have a 50-page letter on her. Threats, etc. . . . she

can cause me, to get another murder charge.

She always mention, she has been help you. So tell

me what you know about her. I don’t want to hurt

her, in any way, or the efforts in the fight against

the death penalty.

She has caused me, a lot of confusion. There was,

well, I’ll wait on reply. Do be in touch as soon as

possible.

Sincerely, Alvin B. Ford.

Appendix I, Letters, M.

L. That Mr. Ford’s July 8 letter was a sign that his

illness was worsening was powerfully confirmed some

two months later, in a letter to Deborah Fins, an attorney

who formerly represented him. By the date of this letter

to Ms. Fins, September 11, 1982, Mr. Ford’s delusional

system had become all-pervasive and all-encompassing.

Because of his work against the Klan, he believed that he

had become the target of a complex scheme of torture

ultimately designed to force him to commit suicide. Al

though this delusion has undergone some change from

September, 1982 to the present, this is the central de

lusion which has governed Mr. Ford’s daily existence

since its onset in September, 1982. There have been no

remissions—from the grip of the delusion, the loosening

37

of associations, and the hallucinations—since then. Be

cause this delusion has been so dominating, Mr. Ford’s

entire September 11 letter has been reproduced, for it

is the critical stepping stone from the past to the present

in Mr. Ford’s life.

Dear Fins. Esq.:

Thank you for your letter of 22 July 82, as of this

date, I still want my, files closed to Doug Magee,

and no one is to have access other than lawyers.

Also I do not in any way, want Dr. Amin, or Gail

Rowland, associated with my case in any manner, as

of this date.

Fm sorry I haven’t replied to your letter, until this

date. I have had a number of problems, at Florida

State Prison, over the pass three months, with

guards, the KKK, and Owl Society or organization.

I really wanted to see you, it’s been such a long

time, Deborah. I wasn’t able to leave the cell, hope

fully you got the refusal slips, and the messages, I

wrote on them, to you.

If you receive any affidavits concerning what has

been going on inside the prison, do hold them, and

make sure all persons, attorneys, etc . . . receive

copies. Do excuse, my saying you were missing, this

was the only way I could get the prisoners interested

enough to write, wherein I could get some help.

Dennis Balske of the Southern Poverty Law Center,

should be sending copies of letters written prison

officials, and lawyers, concerning the problems, I’ve

had here over the pass months, mailed them, to the

Poverty Law Center, because of their Klan-Watch.

Then asked that they send letters, to or copies, to the

lawyers.

My situation needs a solution, as soon as, humanly

possible. I have been threatened 24 hours a day, for

38

the pass three months, by guards and Bill Wilkinson

of the KKK. He has been working here, under the

name of Officer McKenzie, Q-Wing.

When you do visit again bring a tape which can play

six to eight hours. There’s so much has happened,

until I don’t know where to start.

My life is in danger, by these guards and the KKK,

and Owl Society, or organization, plus this labor

union, you should be receiving, copies of letters, to

this effect.

Other than threats, I have been, okay. Have been

more less, trying to gather information, and review

the situation.

Please call Wollan, and Dennis Balske of the Poverty

Law Center, to get a full report. Wollan, Burr III,

and Craig Barnard with Vandiver, was at Florida

State Prison on 11 September 82.

I’ve been hounded by Bill Wilkinson and the KKK,

24 hours a day, the guards, in the labor union, and

Owl Society.

They put me on DC for quite some time, for no

reason. Just got some stamps and Wollan, brought

some. Just got some pens and paper to write with.

Things have been the same continuous hounding.

They are at my door now and in the pipe alley at

the cell, vent.

The story is too long to write, but it’s the truth.

A lady is being held in the pipe alley on Q-Wing,

third floor, behind the cell, I’m in.

I’m told the man holding her name is Crooks, the

only Crooks I know of is one who works at WJAX

95X, 4:00 P.M. to 6:00 P.M. Sundays.

While waiting to see, the lawyers 10 September 82,

the Counselor, Harrington, said I’ll be moved to

39

R-Wing, the working week of 9/13-17/82. While in

the Cage, by the Control Room.

As soon as I got back to Q-Wing, I was told Crooks,

is to murder me on R-Wing or S-Wing, and either

make it look as a suicide, or murder. This lady has

been held in the pipe alley since, well about two

months, being raped by guards as well as prisoners.

This is the reason, I haven’t gotten very much help.

Guards are allowing prisoners to rape this lady, to

keep things quiet, and no one knows she is in this

prison.

I hear her now, asking this man, “Please don’t kill

me.” I have been on Q-Wing since 2 August 82, and

hounded every day for 24 hours, by the KKK and

guards. Can’t even eat, without them at the door

way and cell vent saying they put, “Semen in the

food, by having this lady, perform oral sex,” this

is every day, for the pass three months.

While on S-Wing, guards have tried to ease my door

open in the A.M. hours. Luckily, I was not asleep,

3:30 A.M., because this plantigraph was waiting to

enter the cell with a knife and hatchet, this is the

truth, whole truth, and nothing but the truth, so

help me God.

Doug Magee, published a book, and changed the

authors sold for $680,000. I wrote that book. Paul

Robeson, All American, author Dorothy Butler Gil

liam. He nor Destiny said a word about it, but I

found out, the plan was to try to run me insane,

and make me commit suicide.

This why I don’t want Dr. Amin, on my case, and

Gail Rowland. No one can get the money from the

book unleses, Pm dead. As soon as possible I’ll write

the whole thing. I had but being threatened by the

KKK, in prison, I had to pass the evidence.

40

I’ve never told you a lie, and this is the truth.

Deborah, I think these guards, have been killing

people, and putting the bodies, in these concrete

enclosures, used for beds, on Q-Wing. Deborah, this

is the truth.

These concrete enclosures are used for beds, about six

feet long, four feet wide, and three feet high, just

a concrete block. The one inside the cell, I’m housed

in was open from the pipe alley I think, and the

smell was awful, decomposed bodies.

Do know I’ve never lied to you. While I was out to

see Wollan, Burr III, Craig Barnard, and Vandiver,

I was afraid they may try to clean these things out.

I don’t know what happened, but the lady is still in

the pipe alley, and at this very moment someone

outside my cell door, with threats, the voice sounds

as Bill Wilkinson of the KKK.

Before I moved to Q-Wing to DC, 2 August 82, I

was on DC on S-Wing-l-North-17. There was a gun

on the floor, that was pointed at me, told guards.

No one, did a thing, was a shake down 17 July 82,

led by Bill Wilkinson.

Got a UCI-666 (Form) (sent to Dennis Balske of

the Southern Poverty Law Center, asked he send

all the lawyers copies, notarized) which was written

by Bill Wilkinson, which said, one altered ink pen,

and 5 bundles of paper.

That five bundles of paper was evidence on the book,

mentioned on page five [of this letter], and on the

KKK, and the hounding by this Destiny at WJAK

95X Radio Station. The five bundles of paper was

going to Jim Smith, State Attorney General. They

were trying to get me, to throw them, away, because

guards names were mentioned. I wouldn’t throw

these papers away, so they gave me a DR, for having

41

a knife, when do you know of me having a weapon,

since being in prison. 17 July 82.

15 July 82, the lady who does ABC radio news,

told me not to give those same bundles of paper

(letters) to Classification Officer Dan. I gave them

to him, after some thought asked for them back.

As soon as I did, you need a haircut, another DR

(the letters were four brown envelopes to Jim Smith

on the KKK, the book, and guards, and hounding by

this Destiny).

This lady in the pipe alley said, Sergeant Combs, had

a gun to her head telling her, she better never tell,

she was beaten and raped, with Officer Adams. In

the stairwell of S-Wing I heard them, and told her,

she can tell anyone, because they had no business,

with her in the pipe alley.

When I said that, they cut off my water to the sink

and commode. Orders of Bill Wilkinson, on S-Wing.

Then I was given a DR, saying I threatened to kill

a guard, by Officer Adams.

So Deborah, I’ve been on DC, quite a while. They

have been trying to kill me. Their plan was to do

so on Q-Wing, took everything I owned 2 August 82,

Had no stamps, pens, paper or envelopes, until Sep

tember, although I borrowed a pen and paper. Had

no stamps, but found some reusable ones on old

envelopes and mailed a letter out.

Didn’t get a slip concerning my property until 8

September 82. Had over $25.00 stamps, 400 enve

lopes, 500-600 sheets of paper, 30 pens. Not sure

where my personal property is, but guess I’ll find

out when they take me off DC. More than likely will

have to file suit, under High Risk Management.

These people who have been threaten me, told me,

they murdered all my family. Hopefully you can, get

42

back down here, and bring a full tape, that will play

six to eight hours, each day. No haven’t heard a

word from my relatives.

Channel 4 of Jacksonville has been helping. Keeping

the guards from killing me. The evidence, I wrote

to Jim Smith, State Attorney General, concerning

that book was written over the cell walls of Q-3-

West-3, the cell I’m in now. (That evidence on the

book, was removed from my cell, from S-Wing in

the month of July 82.)

Bill Wilkinson says he has my address book, and is

killing everyone in there, by address. So I wouldn’t

have anyone to help me. Guards wouldn’t mail my

letters, only beat this lady whenever I tried to write

the outside, for help.

So I’ve had to fight the KKK, guards, and prisoners.

Also, because the KKK, and guards, has been using

the prisoners against me, as well allowing to rape

this lady, being held hostage.

So my life is in danger, and need help. Please send

a copy of this letter to the FBI, as soon as possible,