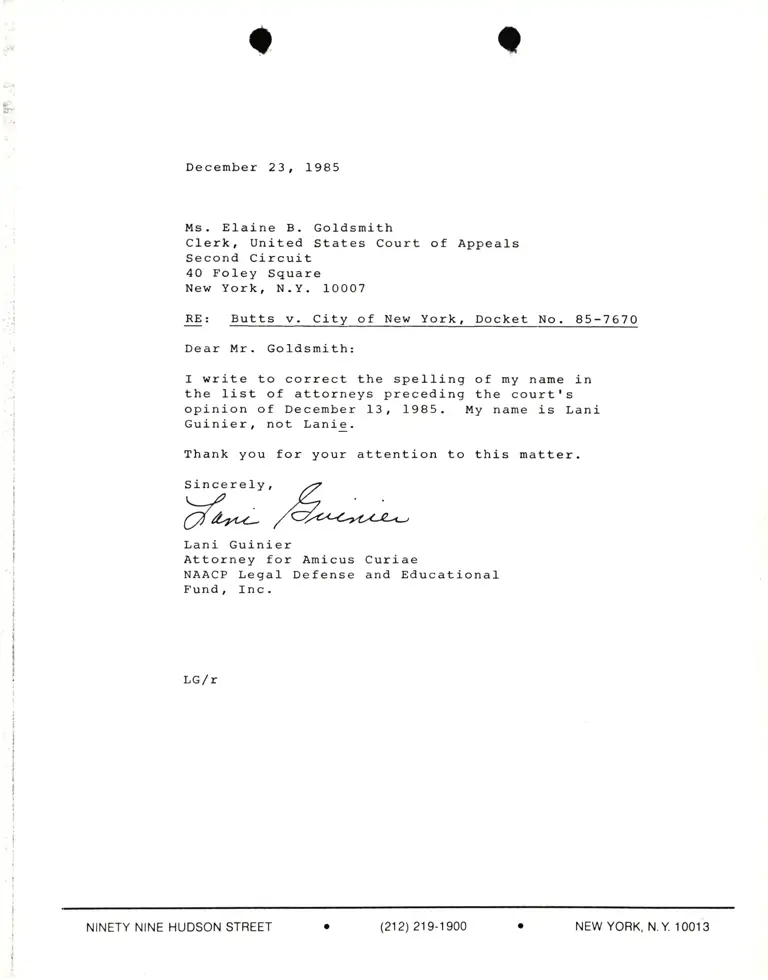

Correspondence from Lani Guinier to Elaine B. Goldsmith (Clerk) Re: Butts v. City of New York

Public Court Documents

December 23, 1985

Cite this item

-

Legal Department General, Lani Guinier Correspondence. Correspondence from Lani Guinier to Elaine B. Goldsmith (Clerk) Re: Butts v. City of New York, 1985. 3c6fe34b-e792-ee11-be37-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/3b466845-1bfe-42b1-82f5-685a34e611e6/correspondence-from-lani-guinier-to-elaine-b-goldsmith-clerk-re-butts-v-city-of-new-york. Accessed February 23, 2026.

Copied!

.!+

December 23, 1985

Ms. EIaine B. Goldsnith

Clerkr United States Court of Appeals

Second Circuit

40 FoJ.ey Square

New York, N.Y. 10007

RE: Butts v. City of New York, Docket No. 85-7670

Dear llr. Goldsmith:

I write to correct the

the list of attorneys

opinion of December 13

Guinier, not Lanie.

spelling of my name in

preceding the court I s

, 1985. My name is Lani

Thank you for your attention to this matter.

S;:V'"1Y, Z,

dd."z- /*<*4tu

Lani Guinier

Attorney for Amicus Curiae

NAACP Legal Defense and Educational

Fund, Inc.

LG/r

NINETY NINE HUDSON STREET (212) 21 9-1 900 NEW YORK, N.Y. 10013