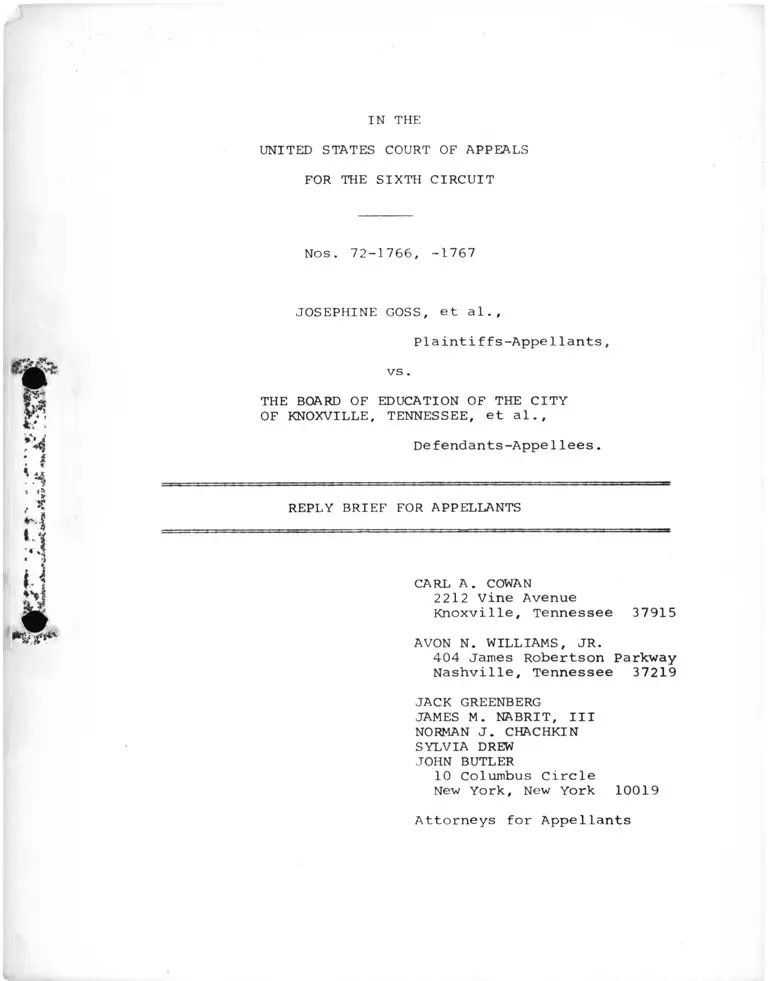

Goss v. Knoxville, TN Board of Education Reply Brief for Appellants

Public Court Documents

December 20, 1972

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Goss v. Knoxville, TN Board of Education Reply Brief for Appellants, 1972. e9addbc5-b39a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/3b4f9525-2a78-414c-aae0-31fe61ad98d9/goss-v-knoxville-tn-board-of-education-reply-brief-for-appellants. Accessed February 06, 2026.

Copied!

IN THE

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE SIXTH CIRCUIT

Nos. 72-1766, -1767

JOSEPHINE GOSS, et al.,

Plainti f f s-AppeHants ,

vs.

THE BOARD OF EDUCATION OF THE CITY

OF KNOXVILLE, TENNESSEE, et al.,

Defendants-Appellees.

REPLY BRIEF FOR APPELLANTS

CARL A. COWAN2212 Vine Avenue

Knoxville, Tennessee 37915

AVON N. WILLIAMS, JR.404 James Robertson Parkway Nashville, Tennessee 37219

JACK GREENBERG

JAMES M. NABRIT, III

NORMAN J. CHACHKIN SYLVIA DREW

JOHN BUTLER10 Columbus CircleNew York, New York 10019

Attorneys for Appellants

IN THE

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE SIXTH CIRCUIT

Nos. 72-1766, -1767

JOSEPHINE GOSS, et al.,

Plainti ffs-Appellants,

vs .

THE BOARD OF EDUCATION OF THE CITY

OF KNOXVILLE, TENNESSEE, et al.,

Defendants-Appellees.

REPLY BRIEF FOR APPELLANTS

I

We should like to limit this reply brief insofar as

possible to a short discussion of the substantive legal errors

made by appellees; however, in light of their charge at pages

10-12 of their brief to the effect that plaintiffs' statement

of facts in our opening brief misrepresented the record, we

feel constrained to add one or two statements in this regard.

We respectfully invite the Court to examine the portions

of the Appendix cited in our original brief for we are confi

dent that they are supportive of the propositions we advanced.

A few illustrations regarding matters specifically mentioned

by appellees may be helpful.

At page 11 of their brief, appellees insist that Dr.

Bedelle "did not agree that black principals made schools

racially identifiable as stated on page 13 of the brief."

Dr. Bedelle's testimony is as follows:

Q. All right. Then we come down to Park Lowry,

Now that is a predominant black school and it

has a black principal doesn't it?

A. Yes.

Q. And go on down to Sam Hill — well, just keep

your finger on the last column and you can find

the formerly black schools in this system, can't

you, Dr. Bedelle?

A. Yes.

Q. Isn't that a matter of racial identifiability,

everyone of them, Austin-East, Beardsley, every

black school has a black principal?

A. And has a black principal with a lot of tenure

in a relatively secure salary category. (A. 146)

On page 12 appellees do correctly note that because of

counsel's error in transcription from his own notes, the wrong

pages were cited for Mr. Lawler's testimony. The proper

reference is to page 375 where he testified as follows:

Q. When you locate public housing in close proximity

to schools segregated by race, and the public

housing is segregated by race, what — would that

or not have a reinforcing effect on segregation in the schools?

A. I would think so.

Q. And if you located schools, on the other hand,

in an area adjacent — an area close to a public

housing pro3ect that was segregated by race,

would that, or not, have a tendency to create or

strengthen segregation in those schools?

-2-

A. If you consider the neighborhood concept, I am

sure it would.

Examination of other claimed inaccuracies would merely be cumu

lative .

II

Appellees at pages 22-26 of their brief criticize us

for our discussion of transfer policies and contend that the

district court did not, as we suggested, "conveniently ignore"

the evidence because it was not pointed out to the judge. We

agree with appellees that Dr. Bedelle produced the transfer

request but was not examined in detail about them. However,

Dr. Stolee testified that his own analysis of the requests

indicated that they had been used to perpetuate segregation.

Whether or not any further emphasis before the district court

was placed upon the transfer requests, the court states in its

opinion (A. 1667-68) that it looked at the forms and disagreed

with Dr. Stolee's conclusions. It was only because the district

court purported to have examined the formswith sufficient

thoroughness to rebut Dr. Stolee's conclusions that we discuss

them in the brief at all.

Ill

The Board argues that Knoxville is somehow different

from Swann because all of the parties (namely, the Board itself)

do not agree that prior to the 1972 hearings, Knoxville had

not attained a unitary nondiscriminatory school system. What-

-3-

t

ever may be the merits of such an essentially picayune distinc

tion, it is clearly inapplicable to Davis v. Board of School

Comm1rs of Mobile, 402 U.S. 33 (1971), the companion case to

Swann before the Supreme Court. The Board would conveniently

overlook the repeated charge by the Supreme Court that desegre

gation efforts are to be tested by their effectiveness just

as it would like to rewrite the Swann decision to relieve it

of the obligation of measuring its desegregation results With

a consciousness of the system-wide pupil distribution. It is

interesting that the discussion of this novel proposition in

the brief (pp. 15-16) does not contain a single case citation.

IV

With respect to the counsel fee issue, we wish to bring

to the Court's attention the November 29, 1972 decisions of the

United States Court of Appeals for the Fourth Circuit in

Bradley v. School Bd. of Richmond, No. 71-1774 (rev1g 53 F.R.D.

28 (E.D. Va. 1971], cited in our opening Brief); Thompson v.

School Bd. of Newport News, Nos. 71-2032-33; Copeland v. School

Bd. of Portsmouth, Nos. 71-1993-94; and James v. Beaufort County

Bd. of Educ., No. 72-1065, which are attached hereto as an

Appendix for the convenience of the Court. In those school

or teacher desegregation cases, the Fourth Circuit rejected

arguments relating to the award of counsel fees that were

essentially the same as those made here by appellants. We urge

-4-

this Court not to follow the Fourth Circuit; we respectfully

refer it to the dissenting opinions of Judge Winter, which we

believe present the proper view as to both the applicability

of §718 of the Education Amendments of 1972 and as to whether a

private-attorneys-general standard should apply in §1983 school

desegregation cases.

We have discussed at length in our main brief the reasons

why §718 applies to this case, and here we will simply reiterate

some of those points in response to the arguments of appellees.

Appellees' discussion of Thorpe v. Housing Authority of

Durham, 393 U.S. 268 (1969) is simply incorrect. There, the

North Carolina Supreme Court had applied what it held to be a

general proposition, namely that statutes are never presumed to

have retroactive effect but only to operate prospectively, when

it held that the HUD regulation at issue did not apply. 393

U.S. at 273-74. The Supreme Court unequivocally rejected that

view and held that, in federal courts, the general rule was that

the law as it existed at the time of decision must govern. Thus,

in Citizens to Preserve Overton Park v. Volpe, 401 U.S. 402 (1971),

the petitioners argued, relying on Thorpe, that a Department of

Transportation regulation issued after the approval of the

highway route in question governed:

-5-

. . . even though the order was not in

effect at the time . . . and even though

the order was not in tended to have

retrospective effect . . . .

401 U.S. at 418 (emphasis supplied). The Supreme Court, after

discussing Thorpe at some length, stated that it does "not

question that . . . [the] order . . . constitutes the law in

effect at the time of our decision . . . ." Id. at 419. No

hint was given that Thorpe was a limited holding arising from

the fortuity that Mrs. Thorpe had obtained stays of her eviction

notice pending the disposition of her petition for writ of

certiorari.

The significant fact, common to Thorpe, Volpe and this

case, is that in the earlier stages of litigation substantive

rights were governed by a rule of law that was subsequently

changed before a final determination of the merits. It is this

factor that distinguishes Greene v. United States, 376 U.S. 149

(1964), cited by appellees, which was specifically relied upon

by the North Carolina Supreme Court in Thorpe, and which

reliance was discussed and rejected by the United States Supreme

Court.

We recognize that the Fourth Circuit, in the attached

decisions, relies on this purported principle of prospective

application. However, we note, as does Judge Winter, that the

majority simply states the principle with no discussion what-

-6-

soever of the meaning or applicability of Thorpe.

Appellees' argument that the private-attorneys-general

theory is inapplicable because of possible HEW enforcement or

the right of the Attorney General to commence suit is also

inapposite. This lawsuit was filed prior to the passage of

the Civil Rights Act of 1964 which established such mechanisms.

At no time during its pendency has the Attorney General sought

to intervene (as that officer has done in some other school

desegregation cases) to effectuate the rights of plaintiffs'

class. And as the United States District Court for the District

of Columbia recently held in Adams v. Richardson, Civ. No.

3095-70 (Nov. 16, 1972)[copy attached as appendix], there has

been no HEW enforcement of desegregation in districts under

judicial supervision.

Moreoever, the Attorney General may also bring and inter

vene in suits to enforce rights protected by Titles II and VII

of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 (see, 42 U.S.C. §§2000a-3, 2000a-

2000e-5 and 2000e-6); nevertheless, it is clear that the private

parties bringing such suits will receive attorneys' fees pursu

ant to Newman v. Piggie Park Enterprises, Inc., 390 U.S.

42 U.S.C. §2000c(6)(b) does indeed permit the Attorney

General to institute a legal action to desegregate a school

district when he has received a complaint in writing, believes

it is meritorious, and deems the complainant "unable, either

directly or through other interested persons or organizations,

to bear the expense of the litigation or to obtain effective

legal representation." The language makes it clear that Congress

intended enforcement of school desegregation to rest not only,

or even principally, upon the activities of the federal govern

ment but rather upon a combination of federal action and

continued vigorous private litigation. Cf. 42 U.S.C. §2000c-(8).

Finally, we submit there is no problem with the "final

order" language of §718. The purpose of that provision is to

prevent collusive lawsuits, not to postpone the assessment of

attorneys' fees until a case is stricken from the docket. We

do not seek to have this Court award fees for services which

will be required upon a remand; rather, we seek direction to

the district court to make an award of reasonable counsel fees

for the period of the litigation which has pushed Knoxville

toward, although not achieving, full desegregation of its school

system.

CONCLUSION

Plaintiffs respectfully repeat their request for relief

contained at pp. 60-61 of the opening Brief for Appellants herein.

-8-

Respectfully submitted,/, /

, ( \ //

CARL A. COWAN

2212 Vine Avenue

Knoxville, Tennessee 37915

AVON N. WILLIAMS, JR.

404 James Robertson Parkway

Nashville, Tennessee 37219

JACK GREENBERG

JAMES M. NABRIT, III

NORMAN J. CHACHKIN

SYLVIA DREW

JOHNNY J. BUTLER

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

Attorneys for Appellants

CERTIFICATE OF SERVICE

I hereby certify that on this 20th day of December,

1972, I served two copies of the foregoing Reply Brief for

Appellants upon counsel for the appellees herein, by depao iting

same in the United States mail, first class postage prepaid,

addressed to each as follows: Sam F. Fowler, Jr., 1412

Hamilton National Bank Building, Knoxville, Tennessee 37902,

and W. P. Boone Dougherty, 1200 Hamilton National Bank Building,

Knoxville, Tennessee 37902.

// , /( c ■

-9-

UNITED STATES CC'JilT GF AFrEAlS

FOR THE FOURTH CIRCUIT

No. 71-1774

Carolyn Bradley and Michael Bradley,

infants, by Minerva Bradley, their

mother and next friend, et al. , Appellees,

-versus-

The School Board of the City of

Richmond, Virginia, et al.. Appellant.

Appeal from the United States District Court for the

Eastern District of Virginia, at Richmond. Robert R.

Merhige, Jr., District Judge.

Section III of the opinion, dealing with the application of

Section 710 to the proceedings, heard October 2, 1972,

Before HAYNSWORTH, Chief Judge, WINTER, CRAVEN, RUSSELL and

FIELD, Circuit Judges (Butrner, Circuit Judge, being dis

qualified) sitting en banc;

Other parts of the cause heard March 7, 1972,

Before WINTER. CRAVEN and RUSSELL, Circuit Judges.

Decided November 29, 1972.

George B. Little (John H. O'Brion, Jr., James K. Cluverius,

and Browder, Russell, Little and Morris, and Conrad B. Mattox,

Jr., City Attorney for the City of Riclur.ond, on briof) for

Appellant, and Louis R. Lucas (Jack Greenberg, James Nabrit,

III, Norman J. Chachkin, James R. Olphin, and M. Ralph Page

on brief) for Appellees.

RUSSELL, Circuit Judge:

This appeal challenges an award of attorneys fees

. nlaintiffs in the school desegregationmade to counsel for plamtins

suit filed against the School Board of the City of Richmond.

Virginia. Though the action has been pending for a nunber

of years/ the award covers services only for a perrod fro*

March, 1970. to January 29. 1971. It is predicated on two

grounds, U) that the actions tahen and defenses entered by

the defendant School Board during such period represented

unreasonable and obdurate refusal to 1 * 1 — * clear consti

tutional standards, and (2) apart from any consideration of

1See Note 1 in majority

School poard of̂ the £.i£X

june 5. 1972. for history of

opinion of Bradley

Richmond, Virginia,

this litigation.

v . The

decided

- 2-

obduracy on the part of the defendant School Board since 1970,

it is appropriate in school desegregation cases, for policy

reasons, to allow counsel for the private parties attorney's

fees as an item of costs. The defendant School Board con

tends that neither ground sustains the award. We agree.

We shall consider the two grounds separately.

I.

This Court has repeatedly declared that only in

"the extraordinary case" where it has been "'found that the

bringing of the action should have been unnecessary and was

compelled by the school board's unreasonable, obdurate obsti

nacy' or persistent defiance of law", would a court, in the

exercise of its equitable powers, award attorney's fees in

school desegregation cases. Brewer v. School Board of. City

of Norfolk, V irginia (4th Cir. 1972) 456 F.2d 943, 949.

Whether the conduct of the School Board constitutes "obdurate

obstinacy" in a particular case is ordinarily committed to

the discretion of the District Judge, to be disturbed only

"in the face of compelling circumstances", Bradley v. School

Boa rd o_f City q£ Richmond, Vi rginia (4th Cir. 1965) 345 F.2d

310, 321. A finding of obduracy by the District Court, like

-3-

any other finding of fact made by it, should bo reversed

however, if "the reviewing Court on the entire evidence is

left with the definite and firm conviction that a mistake

has been committed." United States v. Gypsum Co. (1948) 333

U. S. 364, 395, 68 S. Ct. 525, 92 L. Ed. 746; Wright-Miller.

Federal Practice end Procedure. Vol. 9, p. 731 (1971). We

are convinced that the finding by the District Court of

"obdurate obstinacy" on the part of the defendant School

Board in this case was error.

Fundamental to the District Court's finding of

obduracy ia its conclusion that the litigation, during the

period for which an allowance wao made, was unnecessary and

only required because of the unreasonable refusal of the

defendant School Board to accept in good faith the clear

standards already established for developing a plan for a

non-racial unitary school system. This follows from the

pointed statements of the Court in the opinion under review

that, "Because the relevant legal standards were clear it is

not unfair to say that the litigation (in this period) was

unnecessary", and that, "When parties must institute litiga

tion to secure what is plainly due them, it is not unfair to

characterize a defendant's conduct as obstinate and unreason

able ana as a perversion of the purpose of adjudication, which

- 4-

is to settle actual disputes.- At another point in Its

opinion, the Court uses similar language, declaring that

-the continued litigation herein (has) been precipitated

by the defendants' reluctance to accept clear legal direc

tion, * * *."* 3 It would appear, however, that these criti

cisms of the conduct of the Board, upon which, to such a

large extent, the Court's award rests, represent exercises

in hindsight rather than appraisal of the Board's action in

4the light of the law as it then appeared. The District

Court itself recognized that, during this very period when

it later found the Board to have been unreasonably dilatory

there was considerable uncertainty with reference to the

Hoard's obligation, so much so that the Court had held in

denying plaintiffs' request for mid-school year relief in

2

See, 53 FRD at p. 39.

3 53 FRD at p. 40.

^ See Monroe v. Board of Com' rs. of City of. Jackson.

Tenn. (6th Cir. 1972) 453 F.2d 259, 263:

"In determining whether this Board's conduct

war,, as found by the District Court, unduly

obstinate, we must consider the state of the

law as it then existed."

-5-

the fall of 1970, that "it would not be reasonable to require

further steps to desegregate * * giving as its reason:

"Because of the nearly universal silence at appellate levels,

which the Court interpreted as reflecting its own hope that

authoritative Supreme Court rulings concerning the desegrega

tion of schools in major metropolitan systems might bear on

the extent of the defendants' duty." In fact, in July,

1970, the Court was writing to counsel that, "In spite of the

guidelines afforded by our Circuit Court of Appeals and the

United States Supreme Court, there are still many practical

problems left open, as heretofore stated, including to what

extent school districts and zones may or must be altered as

a constitutional matter. A study of the cases shows almost

limitless facets of study engaged in by the various school

authorities throughout, the country in attempting to achieve

the necessary r e s u l t s . T h e District Court had, also, earlier

defended the School Board's request of a stay of an order

entered in the proceedings on August 17, 1970, stating:

"Their original (the School Board's) requests to the Fourth

53 FRD at p. 33.

^ See, Joint Appendix 74-75.

- 6 -

Circuit that the matter lie in abeyance were undoubtedly based

on valid and compelling reasons, and ones which the Court has

no doubt were at the time both appropriate and wise, since

defendants understandably anticipated a further ruling by

the United States Supreme Court in pending cases; * * *."7

Earlier in 1970, too, the Court had taken note of the legal

obscurity surrounding what at that time was perhaps the crit—

ical issue in the proceeding, centering on the extent of the

Board's obligation to implement desegregation with transpor

tation. Quoting from the language of Chief Justice Burger in

his concurring opinion in Norcross v. Board of Education o_f

Memphis, Tenn. City Schools. (1970) 397 U. S. 232, 237, 90

S. Ct. 091, 25 L. Ed. 2d 426, the District Court observed

that there are still practical problems to be determined,

not the least of which is "to what extent transportation may

or must be provided to achieve the ends sought by prior hold

ings of the Court."8 In fact, the District Court had during

this very period voiced its own perplexity, despairingly com

menting that "no real hope for the dismantling of dual school

systems (in the Richmond school system) appears to be in the

7 325 F. Supp. at p. 032.

8 317 F. Supp. at p. 575.

- 7 -

offing unless and until there is a dismantling of the all

Black residential areas.”9 At this time, too. as the Dis

trict Court pointed out, there was some difficulty in apply

ing even the term "unitary school system".10 In summary, it

was manifest in 1970, as the District Court had repeatedlyI

stated, that, while Brown and other cases had made plain

that segregated schools were invalid, and that it was the

duty of the School Board to establish a non-racial unitary

system, the practical problems involved and the precise

standards for establishing such a unitary system, especially

for an urbanized school system- which incidentally were the

very issues involved in the 1970 proceedings- had been neither

resolved nor settled during 1970; in fact, the procedures are

still matters of lively controversy.11 It would seem, there

fore, manifest that, contrary to the promise on which the

9 317 F. Supp. at p. 560.

10 That this tern "unitary" is imprecise, the District

Court stated in 325 F. Supp. at p. 044:

"The law establishing what is and what is not

a unitary school system lacks the precision

which men like to think imbues other fields

of law; perhaps much of the public reluctance

to accept desegregation rulings is attributable

to this indefiniteness."

11 Bradley v. The School Board of the City of Richmond.

Virginia. decided June 5, 1972, supra.

-8-

District Court proceeded in itr. opinion, the legal standards

to be followed by the Richmond School Board in working out an

acceptable plan of desegregation for its system were not clear

and plain at any time in 1970 or even 1971.

It is true, as the District Court indicates, that

the Supreme Court in 1960 had. in Green v. County. School Board

(I960) 391 U. S. 430. 88 S. Ct. 1689. 20 L. Ed. 2d 716. found

" f reedorn-o f-cho i cc “ plans that were not effective unacceptable

instruments of desegregation, and that the defendant Board,

following that decision, had taken no affirmative steps on

its own to vacate the earlier Court-approved "freedom-of-

choice" plan for the Richmond School system, or to submit a

new plan to replace it. In Green, the Court had held that.

••if there are reasonably available other ways, such for illus

tration as zoning, promising speedier and more effective con

version to a unitary, nonracial school system, 'freedom of

choice’ must be held unacceptable."12 In suggesting zoning.

Green offered a ready and easily applied alternative to

•• freedom-of-choice” for a thinly populated, rural school

district such as Old Kent, but other than denying generally

legitimacy to freedom-of-choice plans, Green set forth few.

12 391 U.S. at p. 441.

if any, standards or benclimaiks for fashioninq a unitary system

in an urbanized school district, with a majority black student

constituency, such as the Richmond school system. In fact, a

commentator has observed that "Green raises more questions than

it answer*;". Perhaps the School Board, despite the obvious

difficulties, should have acted promptly after the decis

ion to prepare a new plan for submission to the Court. Because

of the vexing uncertainties that confronted the School Board

in framing a new rdan of desegregation, problems which, inci

dentally, the District Court itself finally concluded could

only be solved by the drastic and novel remedy of merging

independent school districts,14 and pressed with no local

complaints from plaintiffs or others, it was natural that the

School Board would delay. Mere inaction under such circum

stances, however, and in the face of the practical difficulties

as reflected in the later litigation, cannot be fairly charac

terized as obdurateness. Indeed the plaintiffs themselves were

in some apparent doubt as to how they wished to proceed in the

period immediately after Green and took no action until March,

H2 r. Rev. lib.

14 A measure found inapprooriate by this Court in Bradley

v* lllS School, Board o£ the_ City of Richmond, Virqinia. decided June 5, 1 972 , suora.

-10-

1070. Even then they offered no real plan, contenting them-

se 1 vc- s with demand i ng that the School Board formulate a uni

tary plan, and with requesting an award of attorney's fees.

It is unnecessary to pursue this matter, however, since the

District. Court does not seem to have based its award upon the

inaction of the School Board prior to March 10, 1970, but

predicated its award on the subsequent conduct of the School

Boa rd.

The proceedings, to which this award applies, began

with the filing by the plaintiffs of their motion of March 10,

1970, in which they asked the District Court to "require the

defendant school board forthwith to put into effect a method

of assigning children to public schools and to take other

appropriate steps which will promptly and realistically con

vert the public schools of the City of Richmond into a unitary

non-racial system from which all vestiges of racial segregation

will have been removed; and that the Court award a reasonable

fpe to their counsel to be assessed as costs. With the filing

of this motion, the Court ordered the defendant School Board

to "advise the Court if it is their position that the public

schools of the City of Richmond, Virginia are being operated

in accordance with the constitutional requirements to operate

-11-

unitary schools as enunciated by the United states Supreme

Court." it added that, should the defendant School Board not

contend that its present operations were in compliance, it

should advise the Court the amount of time' needed "to sub

mit a plan." Promptly, within less than a week after the

Court issued this order, the School Board reported to the

Court that (1) it had been advised that it was not operating

"unitary schools in accordance with the most recent enuncia

tions of the Supreme Court of the United States" and (2) it

had requested HEW. and HEW had agreed, to make a study and

recommendations that would "ensure" that the operation of the

Richmond Schools was in compliance with the decisions of the

Supreme Court. This HEW plan was to be made available "on or

about May 1, 1970" and the Board committed itself to submit a

proposed plan "not later than May 11, 1970". A few days later,

the District court held a pre-trial hearing and specifically

inquired of the School Board as to the necessity for "an evi

dentiary hearing" on the legality of the plan under which the

schools were then operating. The defendant School Board can

didly advised the court that, so far as it was concerned, no

hearing was required since it "admitted that their (its) free-

dom-of-choice plan, although operating in accord with this

- 12-

- — T r * » « *

***'*•' c > :.-

Court's order o.f M&jfth 30 » I960, was opefat

„15contrary to const i tut iona lifdfpj irdments

Court characterizes this concession by the

"reluctantly" given, and its finding of re

early stage in the proceeding is an element

Court's conclusion that the School Board ha

The record, however, provides no basis for

zation of the conduct of the School Board,

had manifested no reluctance to concede that

pla n of operation did not comply with Green

m g in a manner*

The District

School Board as

l.p eta nee at this

in the District

s been obdurate,

this characteri-

by the Court for a response to plaintiffs'

acted with becoming dispatch to enlist the

agency of Government supposed to have expe

of school desegregation and charged by law

assisting school districts with such problem

of the School Board at this stage could be

ably calculated to facilitate the progress

and to lighten the burdens of the Court.

The School Board

its existing

When called on

ihotion, it had

Th

supported by the fact that what the Board d

found acceptable and helpful by both the Co4

tiffs. Neither contended that the proposed

assistance of that

rtise in the area

Vith the duty of

s. Every action

said to be reason-

f the proceedings

is conclusion is

• d was apparently

rt and the plain-

time-table was

15 333 F. jupp. 71.

-1 3-

/• *

dilatory or that the use of HEW was an inappropriate agency

to prepare an acceptable plan. As a matter of fact, the

utilization of the services of HEW under these circumstances

was an approved procedure at the time, one recommended by

courts repeatedly to school districts confronted with the

same problem as the Richmond schools.^

On May 4, 1970, HEW submitted to the School Board

its desegregation plan, prepared, to quote HEW, in response

to the Board's own "expressed desire to achieve the goal of

a unitary system of public schools and in accordance with

our interpretation of action which will most soundly achieve

this objective." In formulating its plan, HEW received no

Green v. School Board of City of Roanoke, Virginia

(4th Cir. 1970) 428 F.2d 811, 812; Monroe v. County Bd. of

Educat ion of Madison Co., Tenn. (6th Cir. 1971) 439 F.2d 804,

806; Note, The Courts, HEW and Southern School Desegregation,

77 Yale L. J. 321 (1967).

During oral argument, counsel for the plaintiffs con

tended that HEW had in recent months become a retarding factor

in school desegregation actions, citing Norcross v. Board of

Education of Memphis, Civ. No. 3931, (W.D. Tenn., Jan. 12, 1972

____ F. Supp. ____, ____. Without passing on the justice of

the criticism, it must be borne in mind this was not the view

in 1970, as is evident in the decisions cited. This argument

emphasizes again, it may be noted, the erroneous idea that the

reasonableness of the Board's conduct in 1970 is to be tested,

not by circumstances as they were understood then, but in the

light of 197? circumstances.

-14-

instructions from the School Board. "Except to try our best

to meet the directive of the Court Order and they gave me the

Court Order." There were no meetings of the School Board and

HEW "until the plan had been developed in almost final form."

Manifestly, the Board acted throughout the period when HEW was

preparing its plan, in utmost good faith, enjoining HEW "to

meet the directive” of the Court and relying on that special

ized agency to prepare an acceptable plan. The Board approved,

with a slight, inconsequential modification, the plan as pre

pared by HEW and submitted it to the Court on May 11, 1970.

The District Court faults the Board for submitting this plan,

declaring that the plan "failed to pass legal muster because

those who prepared it were limited in their efforts further

to desegregate by self-imposed restrictions on available tech

niques"17 and emphasizing that its unacceptability "should have

been patently obvious in view of the opinion of the United

States Court of Appeals for the Fourth Circuit in Swann v.

Chari ott e-Mock lonburg Boa rd of Education , 4 31 F.2d (13B) (4th

Cir. 1970), which had been rendered on May 26, 1970." ^ The

See, 53 F.R.D. at p. 31.

See, 3 38 F. Supp. at p. 71.

1 7

-15-

failure to use "available techniques" such as "busing and

satellite zonings" and whatever "self-imposed limitations"

may have been placed on the planners were not the fault of

the School hoard but of MEW, to whom the School Board, with

the seeming approval of the Court and the plaintiffs, had

committed without any restraining instructions the task of

preparing an acceptable plan. Moreover, at the time the plan

was submitted to the Court by the School Board, '-wann had not

been decided by this Court. And when the Court disapproved

the HEW plan, the hoard proceeded in good faith to prepare on

its own a new plan that was intended to comply with the ob

jectives stated by the Court.

The Court did find some fault with the Board because,

"Although the School Board had stated, as noted, that the free

choice system failed to comply with the Constitution, produc

ing as it did segregated schools, they declined to admit during

the June (1970) hearings that this segregation was attributable

to the force of law (transcript, hearing of June 20, 1970, at

322)" and that as a result, "the plaintiffs were put to the

time and expense of demonstrating that governmental action lay

behind the segregated school attendance prevailing in Richmond".1

See, 53 FR at p. 30.

-16-

This claim of obstruction on the part of the Board is based

on the latter’s refusal to concede, in reply to the Court's

inquiry, "that free choice did not work because it was de

20facto segregation". it is somewhat difficult to discern

the importance of determining whether the "free choice" plan

represented "de facto segregation" or not: It was candidly

conceded by the School Board that "free choice", as applied

to the Richmond schools, was impermissible constitutionally,

and this concession was made whether the unacceptability was

21due to ”de facto" segregation or not. in a school system

such as that of Richmond, where there had been formerly de

■jure segregation. Green imposed on the School Board the "duty

to eliminate racially identifiable schools even where their

preservation results from educationally sound pupil assignment

22policies." The School Board's duty was to eliminate, as far

20

See Joint Appendix 47, Tr. p. 322.

21

See 345 F. 2d 322.

2202 Mar. h. Rev. Ill; rf., Fills v. Board of Public

Instruction o_f Orange C o . , F1 a . (5th Cir. 1970) 423 F. 2d 203,

204 .

-17-

as feasible, "racially identifiable schools” in its system.

The real difficulty with achieving this result was that,

whatever may have been the reasons for its demographic and

24residential patterns, there was, as the Court later 23 24

23

23

The very term racially identifiable" has received no

standard definition. in Beckett v. School Board of City of

Norfojk (D.C.Va. 1969) 308 F. Supp. 1274. 1291,r e ~ o^ other

grounds, 434 F. 2d 408, the Court found that a school in which

f-he representation of the minority group was 10 per cent or

bottor was not 'racially identifiablo". Dr. Pettigrew, the

expert witness on whom the District Court in this proceeding

relied heavily and who testified in Beckett, used 20 per cent

in determining 'racially identifiable" school population.

See 306 F. Supp. 1291. The recent case of Yarbrough v.

Hu 1hert-West Memphis School pist. No. 4 (8th Cir. 1972)

457 F. 2d 333, 334, apparently would define as "racially

identifiable" any school where the minority, whether white or

black, was less than 30 per cent. The District Court in this

proceeding would, in its application of the term "racially

identifiable", construe the term as embracing the idea of a

"viable racial mix" in the school population, which will not

lead to a desegregation of the system. 330 F. Supp. at pp. 194

Actually, as Dr. Pettigrew indicated, it would seem the term

"racially identifiable" has no fixed definition and, its

application, will v^ry with the circumstances of the particular

situation, just as a plan of desegregation itself will vary,

since, as the Court said in Green, supra, at p. 439, "There is

no universal answer to complex problems of desegregation; there

is obviously no one plan that will do the job in every case. "

24That school policy is generally a minimal factor in

such, situation, see 65 liar. I,. Rev. 77. m fact, the use of

zoning and restrictive covenants as instruments of segregation

is far more typical of northern than southern communities. See

McCloskey, The Modern Supreme Court (Mar.,1972), pp.109-10;

"In fac.t, the maintenance of 'black ghettos'

in tlie- cities was the north's substitute for

th' segregation laws of the south * * *. The

- If -

reluctantly recognized, no practical way to achieve a

racially balanced mix, whatever plan of desegregation

was adopted, with a school population approximately

65 per cent black, it was not possible to avoid having schools

25that would be heavily black. The constitutional obligation

thus could, in that setting, only have as its goal the one

stated by the District Court, i.e., "to the extent feasible

26within the City of Richmond." Indeed, it was the very

intractability of the problem of achieving a "viable racial

mix" that prompted the Court to suggest in July, 1970, that it 25 26

24(Continued)

president's Committee on Civil Rights reported

in 1947 that the amount of land covered by

racial restriction in Chicago was as high as

80 per cent and that, according to students

of the subject, virtually all new subdivisions

are blanketed by these covenants."

25Cf.. United states v. Choctaw County Board of Education

(D.C.Ala. 1971) 339 F. Supp. 901, 903.

26

See 325 F. Supp. 835.

- 19-

might be appropriate for the def<ndant School Board to discuss

with the school officials of the contiguous counties the

feasibility of consolidation of the school districts, "all

27of which may tend to assist them in their obligation".

The Court's finding of obstruction particularly

centers on the substitute plan which the School Board

proposed on July 23, 1970, in accordance with the Court's

previous directive. It found two objections to the plan. The

objections are actually part of one problem, i.c.,

transportation. The Hirst objection was that the plan did not

require as much integration in the elementary grades as in

the higher grades. Such a difference in treatment, however.

28 29the Court found had some support in both Swann and Brewer.

An increase in the desegregation of the elementary grades,

however, depended upon the purchase and use of a considerable

amount of transportation equipment by the Board; and this was t

basis of the second criticism that 'the School Board had in

27See Joint Appendix 74

2B

431 F. 2d 13R.

29

In 321 F. Supn. ‘“68, the Court said;

"Lanauan and holdinas in both Swann and

Bjrewer v-. School I ioa r d of c i t y of Norfolk ,

4 34 F. 2d 408 (4 th C i r . Juno 22, 1970),

indicate that a schorl board's duty to

desegregate at the secondary level is some

what-more categori-M than at the elementary level,

August 0.970) still taken no steps to acquire the necessary

equipment. ,,3° The Court repeated this criticism with refer

ence to the plaintiffs' mid-term motion made in the fall of

1970 for an amendment of defendant's approved interim plan

which, for implementation, "required the purchase of trans

portation facilities which the School Board still would only

say it would acquire if so ordered."30 31 Yet at the very time

when the action of the School Board in failing to buy buses

was thus being found to be "unreasonably obdurate", the Court

itself was declaring on August 7, 1970, that "it seems to me

it would be completely unreasonable to force a school system

that has no transportstion, and you all don't have any to

any great extent, to go out and buy new busses when the

United States Supreme Court may say that is wrong. Again,

as late as January 29. 1971. the Court, in refusing to order

the immediate implementation of a plan submitted by the

plaintiffs, which "would require the acquisition of additional

transportation facilities not then available", found that "the

30 53 FRU 32.

31 53 FRD 32-3.

Joint Appendix 92-3.

- 21-

possibility that forthcoming rulings (by the Supreme Court,"

might make such acquisition unnecessary and a needless expense

induced "the court to decide that Mediate reorganisation

Of the Richmond system would be •unreasonable, under Swann "33

“ thC C°Urt Jid "0t fCCl - — reasonable in January. l97l

to require the Board to purchase additional buses, it certain-

t be said that, m the period of uncertainty in 1970

the failure of the School Board to propose such acquisition.'

lustifies any charge of unreasonableness, much less obdurate

ness or action "in defiance of law" or taken in "bad faith".

The conclusion of the District Court that the Board

was "unreasonably obdurate", it seems was • ,,ctrTIS' was influenced by the

feeling, repeated in a number of the Court's opinions, that

"Each move (by the Board, in the agonisingly slow process of

desegregation has been taken unwillingly and under coercion".34

The record, as we read it. though, does not indicate that the

Board was always halting, certainly not obstructive, in its

efforts to discharge its legal duty to desegregate, nor does

it seem that the Court itself had always so construed the

3 3

34

Sec, Joint Appendix 132, 13/j, 135

338 1 . Supp. 103; see. also. 53 FRD 39.

- 22-

action of the Board. In June, 1970, the Court remarked, that

while not satisfied "that every reasonable effort has been

made to explore" all possible means of improving its plan,

it was "satisfied Dr. Little and Mr. Adams (the school admin

istrators) have been working day and night diligently to do

the best they could, the School Board too."^^ It may be that

in the early years after Brown the School Board was neglect

ful of its responsibility, but, beginning in the middle of

1965, it seems to have become more active. Moreover, the

promptness and vigor with which the Board adopted and pressed

the suggestion of the Court that steps be considered in con

nection with a possible consolidation of the Richmond schools

with those of Chesterfield and Henrico Counties must cast

doubt upon any finding that the Board was unwilling to explore

any avenue, even one of uncharted legality, in the discharge

of its obligation. The Court wrote its letter suggesting a

discussion with the other counties looking to such possible

consolidation on July 6 , 1970. The letter was addressed to

the attorneys for the plaintiffs but a copy went to counsel

for the School Board. Nothing was done by counsel for the

plaintiffs as a result of this letter but on July 23, 1970,

35 See , Joint Appendix 92.

-23-

the Board moved the Court for leave to make the School Boards

of Chesterfield and Henrico Counties parties and to serve on

them a third-party complaint wherein consolidation of their

school systems with that of the Richmond systems would be

required. The Board thereafter took the -laboring oar" in

that proceeding. Neither it nor its counsel has been halting

m pressing that action, despite substantial local disapproval.36 37

It is clear that the Board, in attempting to develop

a unitary school system for Richmond during 1970, was not

operating in an area where the practical methods to be used

were plainly illuminated or where prior decisions had not

left a "lingering doubt" as to the proper procedure to be

37

followed. Even the District Court had its uncertainties.

All parties were awaiting the decision of the Supreme Court

in Swann. Before Swann was decided, however, the parties

were engaged in an attempt to develop a novel method of

desegregating the Richmond school system for which there was

not as the time legal precedent. Nor can it be said that

there was not some remaining confusion, at least at the District

36

See, 338 F. Supp. 67, 100-1.

37Sec, Lora! No. 149 A.& A. I .W.

I*I£Lk<I Co_j_ (4t h Cir. 1902) 298 F. 2d 212,

369 II. S. 873, 82 S. Ct. 1142, 8 L.Ed.2d 276.

v. American

216, cert. den.

In ivrer on v. Ra^, 380 u.S. 547, 557 (1967), it was

stated that "a police officer is not charged with predicting

the future course of constitutional law " nv like -

seem a school board should not be required, under penalty of’beiS

charged with obdurateness and being saddled with onerous attorneys

law" * i n°t h^murky^’i'rod 0^ ^ course of "const i tut iona

1 no murKy <<ioa of school desegregation. 2 4

30 Thr frustrationslevel, about the scope of Swann tt-el •

Of the District court in its commendable attempt to arrive

at a school Plan that would protect the constitutional rights

of the plaintiffs and others in their class, are understand

able. but. to some extent, the School Board itself was also

v fp. Find undo r the sc c i. it frustrated. It seems to us unfair to find un

cumstances that it was unreasonably obdurate.

The District court enunciated an alternative ground

for the award it made. It concluded that school desegregation

actions serve the ends of sound public policy as expressed in

Congressional acts and are thus actually public actions,

carried on by •■private-attorneys general", who are entitled

to be compensated as a part of the costs of the action. Specif

ically. it held that "exercise of equity power requires the

Court to allow counsels' fees and expenses, in a field in

which congress has authorised broad equitable remedies 'unless

special circumstances would render such an award unjust.'"

Apparently, though, the District Court would limit the appli

cation of this alternative ground for the award to those

3H winstnn-Falem/Forsyth County Board _°I Education

v. Scott^ opi^ori'of-Chief Justice Burger, dated August 31.

1 971 . ____U S . -----*

39 See 53 FRD at p. 42.

-2 5-

frn

r

situations where the rights of the claim,rrplaintiff were plain and

the defense manifestly without merit This en , ■• mis conclusion fol-

lows from the fact that the Court finds this right of an

item previous expressions in the opinion, the Court concluded

that all doubts about how to achieve a non-racial unitary

schc.1 system had been resolved, and any failure of a school

system to inaugurate such ^e such a system was obviously in bad faith

and in defiance of law That- fmiiThat follows from this statement made

by way of preface to its exposition of its alternatis alternative ground:

oraSli^ingC'f^sSon°th:Clih0 *">ropri.t„n...

equitable standa, '̂ h e ^ I r Y 1V ', d i t ; ! 1that in 1970 and ini, It “ 15 persuaded

full^and'ai0n “ ‘^ “ i o n ^ s ^ ^ s u c h ^

alternative ground for today's ruling."40

If this is the basis for the Court's alternative

ground, it realiy does not differ from the rule that has

heretofore been followed consistently by this Court that.

where a defendant defends in bad faith or in defiance of law.

equity will award attorney’a foes The diff ny ees. The difficulty with the

application of l ho ConrPe -> ,,Court s alternative ground for an award on

40

S & c , 5 3 FRD at p. 41.

-2 6-

this basis, though, is its assumption that by 1970 the law

°n the standards to be applied in achieving a unitary school

system had been clearly and finally determined. As we have

seen, there was no such certainty in 1970; indeed it would

not appear that such certainty exists today. And it is this

very uncertainty that is the rationale of the decision in

Kelly, v. Guinn (9th cir. 1972) 456 F.2d 100. 111. where the

Court, citing both the District Court’s opinion involved in

this appeal (53 FRD 26). and Lee v. Southern Home sites Coro,

(5th Cir. 1970) 429 F.2d 290. 295-296.41 sustained a denial

of attorney’s fees in a school integration case, because.

"First, there was substantial doubt as to

the school district's legal obligation in

the circumstances of this case; the dis

trict s resistance to plaintiffs’ demands

rested upon that doubt, and not upon an

obdurate refusal to implement clear consti

tutional rights. Second, throughout the

proceedings the school district has evinced

a willingness to discharge its responsibili

ties under the law when those duties were made clear."

If, however, an award of attorney's fees is to be

made as a means of implementing public policy, as the District

Court indicates in its exposition of its alternative ground of

award, it must normally find its warrant for such action in

See, also, lyse v. Soul hern Homo Sites C o m 1971) A 44 F . 2d 143. ‘ ^ (5th Cir.

-27-

pro-statutory authority. Congress, however, has made no

vision for such award in school desegregation cases. Legis

lation to such effect, included in a bill to assist in the

integration of educational institutions, was introduced in

1971 in Congress but it was not favorably considered. More

over, in the Civil Rights Act of 1964, it expressly provided

for such award in both the equal employment opportunity^ and

44tne public accommodations sections but pointedly emitted to

include such a provision in the public education section.

In giving effect to this contrast in the several titles of

the Civil Rights Act of 1904, and in affirming that any award

of attorney’s fees in a school desegregation case must be pred

icated cn traditional equitable standards, the Court in Kemp v.

Beasley (8th Cir. 1965) 352 F. 2d 14, 23, said:

42

42See Fleischmann v. Maier Brewing Co. (1967) 386 U. S.

> 87 S. Ct. 1404, 18 L. Ed. 2d 475; see, also. Brewer

v ' Schoo1 Board of City of Norfolk, Virginia, supra, note 22. at p. 950.

43

See, Section 2000 e-5(k), 42 U.S.C.

44

See, Section 2000 a-3(b), 42 U.S.C.

45

Section 2000 c-7, 42 U.S.C.; and see. United States

v. Gray (D.C.R.I. 1970) 319 F. Supp. 871, 872-3. SeT^

however. Note 57, post.

-28-

"Congress by specifically authorizing attorney's

fees in Public Accommodation cases and not making

allowance in school segregation cases clearly

indicated that insofar as the Civil Rights Act

is concerned, it does not authorize the sanction

of legal fees in this type of action. The doc

trine of Expressio uniuw est exclusio alterius

applies here and is dispositive of this conten-

t ion. "

The same conclusion was reached in Monroe v. Board of Com'rs.

of City of Jackson, Tenn. (6th Cir. 1972) 453 F.2d 259, 262-3,

note 1 , where an award, though sustained, was sustained on the

ground of "unreasonable, obdurate obstinacy" as enunciated in

Bradley v. School Boa rd ojf Richmond, Vi rginia (4 th Cir. 1965)

345 F.2d 310, 321, and not as a vehicle for the enforcement of

public policy. To the same effect is United States v. Gray.

supra .

It is suggested that Mills v. Electric Auto-Lite

(1970) 396 U. S. 375, 90 S. Ct. 616, 24 L. Ed. 2d 593, and

Lee v. Southern Home Sites Corp. (5th Cir. 1971) 444 F.2d 143,

sustain this alternative award as in the nature of a sanction

designed to further public policy. Any reliance on Mills is

“misplaced, however, because conferral of benefits, not policy

enforcement, was the Mills Covi rt ' s stated justification for

46its holding." 50 Tex. L. Rev. 207 (1971). In fact, the

See, also, Ka ha n v. Rosenst iel (3d Cir. 1970) 424 F.2d

161, 166:

"In the Mills opinion. Justice Harlan noted that

the plaintiffs' suit conferred a benefit on all

the shareholders * * (Italics added.)

-29-

award in MiJ_l^ wan based on the same concept of benefit as

was used to support the award in Trustees v. Greenouoh (1081)

105 U. S. 527. 36 Mo. L. Rev. 137 (1971). Equally inapposite

is Lee. Though filed under Section 1982, it was like unto,

and, so far as relief was concerned, should be treated sim

ilarly as an action under Section 3612(c), 42 U.S.C., in

which attorneys fees are allowable/ 7 By this reasoning,

the Court sought to bring the award within the umbrella of

a parallel specific statutory authorization/ 8 There is no

basis for such a rationale here.

If, however, the rationale of Mills is to be

stretched so as to provide a vehicle for establishing judi

cial power justifying the employment of award of attorney's

47

See, particularly note 2, p. 147, 444 F. 2d.

This case has been criticized in bo Tex

Thus, it finds untenable its attempt to identify its award

with the statutory authorization provided in Section 3612(c)

because, "Under the latter statute (section 3612) the court

may not award attorney's fees to a plaintiff financially able to pay his own fees." (Page 208).

48

ISniallt V. Auciello (1st Cir. 1972) 453 F. 2d

a similar case, involving discrimination proscribed tion 1982, 42 U.S.C.

852, is

by Sec-

-30-

fcco to promote and encourage private litigation in support of

public policy as expressed by Congress or embodied in the Con

stitution, it will launch courts upon the difficult and complex

task of determining what is public policy, am issue normally

reserved for legislative determination, amd, even more difficult,

which public policy warrants the encouragement of award of

fees to attorneys for private litigants who voluntarily

49

take upon themselves the character of private attorneys-general.

Counsel in environmental cases would claim such a role for

50their services. The protection of historical houses and

monuments against the encroachment of highways has been

cloaked within the mantle of public interest and it would be

51

argued should receive the encouragement of an award. Con-

52suraers' suits are clearly to be considered. Apportionment

See, Note, The Allocation of Attorney's Fees After

Mills v. Electric Auto-Lite Co., 38 University of Chicago L.

Rev. 316, at pp. 329-30 (1971).

50See, Section 4332(2), et seq., 42 U.S.C.; Environmental

Defense Fund v. Corps of Eng. of U.» S. Ax my, (D.C. Ark. 1971)

325 F. Supp. 749; Environmental Defense Fund, Inc. v. Corps of,.

Engineers (D.C.D.C. 1971) 324 F. Supp. 878; Businessmen

Affected Severely, etc, v. D.C. City Counci1 (D.C.D.C. 1972)

339 F. Supp. 793.

Sec. Section 461, 16 U.S.C., and Section 4331(b)(4),

42 U S C * West Virginia Highlands Conserv. v. Island Creek

Coal/Co." (4th~Cir. 1971) 441 F. 2d' 232; Cf., Ely v. Velde (D.C.

Va. 1971) 321 F. Supp. 1008.

5 2 g e e, 38 U n i v e r s i t y o f Chicago, L. Rev. 316.

scnts would justify awards und.-r this th-ory.5 ’ First

Amendment rights arc* often spoken of as preferred

constitutional rights. Attacks upon statutes infringing free

speech would, under this theory, command an allowance. nut

it must be emphasized that whether the enforcement of

Congressional purpose in all these cases commands an award of

rncy s fees is a matter for legislative determination. And

Congress has not been reticent in expressing such purpose in

those cases where it conceives that such special award is

appropriate. in many instances, where Congress has enacted

statutes designed to further public purpose, it has bulwarked

their enforcement with provisions for the allowance of counsel

fees to attorneys for private parties invoking such statutes; in

54other cases it has denied such awards Tawards. In some of the statute,

authorizing such allowances, the award is, as in the

statute involved in Newman v. Piggie Park Enterprises

(l')6R) 390 u. S. 400, 80 S. Ct. 964. 19 L . Ed. 2d 1263.

cither mandatory or practically so; in others it is

a- 55discretionary and the granting of awards is generally made * 54 55

Actually, an alternative award has been made in such

a case. Sims v. Amos (3-judge ct. Ala. 1972) F Sudd

(filed March 17, 1972). ---- " P P ‘----- '

54

See Annotation, 8 L. Ed. 2d 894, at pp. 922-32. for a

listing of statutes authorizing an award of attorney's fees

Lending a cU Sh°U ld a<Wod S,‘ctio" 1640. 15 U.S.C. (Truth-in-

55

See, for instance. Section 1 5 3 , 4 3 U.S c • i i n i f - o r i

T x a n ^ pi tgtion Uni»n_v. Soo Li no RR eg. (7th*cir. T 9 7 2 ) ~ 4 5 7 F 2d

through the use of the same guidelines as motivate courts in

making awards under the traditional equity rule. Should the

courts, in those instances where Congress has failed to grant

the right, review the legislative omission and sustain or

correct the omission as the court's judgment on public policy

suggests? This, it seems to us. would be an unwarranted exercise

of judicial power. After all. Courts should not assume that

Congress legislates in ignorance of existing law, whether

statutory or precedential. Accordingly, when Congress omits

to provide specially for the allowance of attorney's fees in

a statutory scheme designed to further a public purpose, it

may be fairly accepted that it did so purposefully, intending

that the allowance of attorney's fees in cases brought to

enforce the rights there created or recognized should be

allowed only as they may be authorized under the traditional

and long-established principles as stated in Sprague v.

Ticonic Bank (1939) 307 U. S. 161, 166, 59 S. Ct. 777,

83 L. Ed. 1184. Such consideration, it would seem, was

the compelling reason that prompted one commentator to

offer the apt caveat that the determination of public policy

as a predicate for such awards should be more 9afely left with

Congress and not undertaken by the Courts. Thus in 50 Tex. L.

Rev. 209 (1971), it is stated:

-33-

The decision, (referring to Lee) however,

sanctions excessive judicial discretion that

may emasculate the general rule against fee

awards and inject more unpredictability into

the judicial process. The legislature should

formulate a rule that would promote predicta

bility and utilize the power inherent in fee

allocation to pursue the goals it desires to

achieve, one of which would be equal access

to the courts."

Even the author of the Note, The Allocation of Attorney’s

Fees After Mills v. Electric Auto-Lite Co.. 38 University of

Chicago Rev,. , 316, though sympathetic to the extension of

cover awards of attorney's fees in support of public

policy, recognizes that a general policy, applicable to all

cases, on the award of attorney's fees should be adopted,

concluding its review of the subject with this comment:

Logically, one of two things must happen:

either judicial discretion to grant fees on

policy grounds will result in universal fee

shifting from the successful party, or the

courts will withdraw to the traditional posi

tion, denying any fee transfer without specific

statutory authorization. Mills represents an

uneasy half-way house between these two

extremes." (Page 336)

We find ourselves in agreement with the conclusion

that if such awards are to be made to promote the public

policy expressed in legislative action, they should be

-3d-

authorized by Congress and not by the courts. This is

especially true in school cases, where the guidelines are

murky and where harried, normally uncompensated School

Boards must tread warily their way through largely uncharted

and shadowy legal forests in their search for an acceptable

plan providing what the courts will hopefully decide is a

unitary school system.

Accordingly, until Congress authorizes otherwise

awards of attorney's fees in school desegregation cases must 56

56

56

It is interesting that in all the cases where the

right to make an award for policy reasons has been stated,

it has been stated simply as an alternative ground to a

finding of unreasonable obduracy. See, 53 FRD at pp. 39-42,

40(1 supra, at p. 144. In Sims, supra. at p. ____, the

Court found that, "The history of the present litigation is

replete with instances of the Legislature's neglect of, and

even total disregard for, its constitutional obligation to

reapportion." In short, no court has yet predicated an award

exclusively upon the promotion of public policy.

-35-

i.co«. upwn uaiiiuuiwi equiianie sLdnaaros as stated in

Bradley v. Richmond School hoard (4th Cir. 1965) 345 F.2d 310,.

which provide ample scope for the award in appropriate cases.

Ill.

After the above opinion had been prepared but not

issued, the Congress enacted Section 71R of the Emergency

School Aid Act. The appellees promptly called to the Court’s

attention this Section, suggesting that it provided an

alternative basis for the award made. They construed the

reference in the Section to "final order” to embrace any

appealable order dealing with any issue raised i.s a school

desegregation case. Any order which had been appealed and

was pending on appeal, unresolved, on the effective date of

the Section (i.e., July 1, 1972), they argued, could provide

a proper vehicle for an award under the Section.56(a)

Since this issue of the application of Section 71R

was raised simultaneously in a number of other pendinq appeals,

it was determined to withhold the above opinion for the time

beinq, and to consider on lane the reach of Section 71R,

as applied both to this c.ir;p and to the other related appeals.

Such banc hearing has been had and the Court has concluded

56*a^Durinq the course of the oral argument counsel for the

appellees was asked to define the term "final order" as used in

Section 7 1R. His reply v;a s ,

"* * there is mention of final order in the legisla

tive material- they use that term rather than a final

judgment because in recognition of the peculiar nature

of school cases,- that in you may have a wave of litiga

tion that would end up in a final decision by this court

or the Supreme Court and then the case would again be re-

litigated later-- that order which is appealable is a final order." -36-

that Section 710 does not reach services rendered prior to

June 30, 1972.

Were it to be construed as extending to any "final

order", entered as "necessary to secure compliance", and

pending unresolved on the effective date of the Act (which

is the plaintiffs* construction of the sweep of the Section),

such Section could not be used as a vehicle to validate this

award. This is so because there was no "final order" pending

unresolved on appeal on June 30, 1972. to which this award

could attach. The only proceeding pending unresolved in this

case on May 26. 1971. when the District Court issued its order

allowing attorney's fees, was the action begun on motion of

the School Board itself to require the merger of the Richmond

schools with those of the contiguous counties of Chesterfield

and Henrico. All orders issued prior to that date in this

desegregation action had long since become final and were not

pending on appeal either on May 26 or on the date Section 718

became effective. Thus, on August 17. 1970. the District Court

had approved the School Board’s interim plan for the school

57 James

Cope 1 <•> nd , e t

V i roj ni«i , ot

School Board

(Nos. 71-2032

v . The Beaufort County Board of Education (72-1065)

1 V- fjrhoql Hoard of the Citv of Portsmouth,

iTl"7 (NosTTl -19~)3 and 71-1994); Thompson v. The

of the City of Newport News, Virginia, e_t a 1_._

_and~71-203 3) , filed October____ , 1972.

-37-

year 1970-1. There was no appeal perfected from that order.

The plaintiffs had moved on December 9, 1970, for additional

relief but that motion had been denied by an order dated

January 29, 1970, which, incidentally, was the same date

used by the District Court for the cut-off of its allowance

of attorney's fees. Again, there was no appeal from that

order dismissing plaintiffs' application for relief, and,

even if it be assumed that plaintiffs' attorneys are to be

granted attorneys' fees when they do not prevail (an assump

tion clearly not psrmitted under the language of Section 718) ,

the proceeding under which that order was entered was not

58pending when Section 718 became effective. To restate*

The only proceedings pending undetermined by an order that

had not become final on the date Section 718 became effective

was the action begun by the School Board and resulting in the

59order of the District Court dated January 10, 1972. That

order, which, it may be assumed, is still pending since the

58 is true that on January 29, 1971, the School Board

submitted to the District Court its proposed plan for the

operation of the Richmond schools for the school year 1971-2.

There seems to have been either no dispute over this plan or

the proposal was swallowed up in the more expansive merger

action.

59 338 F. Supp. 67.’

-38-

• V -

School Board is presently seeking certiorari, was reversed

by this Court60 and. unless the decision of this Court is

in turn reversed, it will not support any allowance of

attorneys' fees, since Section 71B authorises allowance only

when plaintiffs have prevailed.

REVERSED

60 462 F.2d 1058.

WINTER, Circuit Judge, dissenting:

The in biinc court holds that this case is not governed

by § 718 of Title VII, "Emergency School Aid Act," of the

Education Amendments of 1972. P.L. 92-318; 86 Stat. 235;

1972 U.S. Code and Admin. News 1908, 2051. The panel concludes

I<oth that the Richmond School Board was not guilty of "un

reasonable, obdurate obstinacy" and that plaintiffs were not

entitled to recover counsel fees under the private attorney

general concept. On all issues, 1 would conclude otherwise

and I therefore respectfully dissent.

I .

Because 1 conclude not only that § 718 is applicable to

this litigation, but also that, as a matter of statutory

construction, its terms arc met, 1 place my dissent from the

panel's decision piimarily on that ground. If, however, § 718

is treated as inapplicable to this case, I would affirm the

district court, preferably on my concurring views in Brewer

v. School Board of City of Norfolk, Virginia, 456 F.2d 943,

952-54 (4 Cir. 1972) cert. den. ____ U.S.____ (1972). Even

- 40 -

r~ ̂

if the obdurate obstinacy test controls, I would still affirm.

As I read the record, I can only conclude that for the period

for which an allowance of fees was made, the Richmond School

Board was obdurately obstinate. Commendably, it seized the

initiative in vindicating plaintiffs' rights by seeking to

sustain a consolidation of school districts; but this was a

latter-day conversion that occurred after the district couvc

suggested that consolidation be explored. Until that time the

record reflects the Board's stubborn reluctance to implement

Brown 1 (Brown v. Board of Education, 347 U.S. 483 (1954) in

the light of Green v. County School Board of New Kent County,

Va., 391 U.S. 430 (1968); Alexander v. Holmes County Board of

Education, 396 U.S. 19 (1969); Carter v. West Feliciana Parish

School Board, 396 U.S. 226 (1969); and, while the litigation was

progressing, Swann v. Char lotte-Mecklenburg Board of Education,

402 U.S. 1 (1971). The history of the litigation, as set forth

in the opinion of the district court, is sufficient to prove

the point. Bradley v. School Board of City of Richmond,

Virginia, 53 l'.R.D. 28, 29-33 (E.D. Va. 1971).

-41-

11 .

] turn to the more important questions of the scope and

application of § 710. Neither in the instant case, nor in

James v. The Beaufort County Board of Education. ----F.2d----

(4 cir. decided simultaneously herewith), does the majority

articulate in other than summary form why § 710 should not

apply to cases pending on its effective date (July 1. 1972).

1 conclude that it does apply, and in the face of the majority's

silence, I must discuss the pertinent authorities at some

long th .

The text of § 710 is set forth in the margin.1 Its

Attorney Fees

S(»c. 7 18. Upon the entry of a final order by a court

of the Unite;) States against a local educational agency,

a State (or any agency thereof), or the United States

(or any agency thereof), for failure to comply with any

provision of this title or for discrimination on the basis

of race, color, or national origin in violation of title VI

of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, or the fourteenth amend

ment to the Constitution of the United States as they

pertain to elementary and secondary education, the court,

in its discretion, upon a finding that the proceedings

wore necessary to bring about compliance, may allow the

prevailing party, other than the United States, a reasonable

atloi i icy ‘ s fee as part of t he costs.

-42-

enactment presents no question of retroactive application to

this litigation. As 1 shall show, the issue of the allowance

of counsel fees has been an issue throughout every stage of

the proceedings; and the proceedings were not terminated when

§ 71B became effective on July 1, 1972, because this appeal

was pending before us. This is not a case where a subsequent

statute is sought to be applied to events long past and to

issues long finally decided. Rather, it is a case which

presents the concurrent application of a statute to an issue

still in the process of litigation at the time of its enactment.

United States v. Schooner Peggy, 1 Cranch 103 (1801), and

Thorpe v. Housing Authority of Durham, 393 U.S. 268 (1969),

are the significant controlling authorities.

In Peggy, while an appeal was pending from a decision of

the lower court in a prize case, the United States entered

into a treaty with France, which if applicable would have

required level sal. The treaty explicitly contemplated that it

would lie applicable to seizures that had taken place prior to

the treaty's ratification where litigation had not been

terminated prior to ratification. On the basis of the new

-4 3-

treaty, the Supreme Court reversed the decision of the lower

court. In the opinion of Mr. Justice Marshall, it was said:

It is in the general true that the province of an

appellate court is only to inquire whether a judgment

when rendered was erroneous or not. But if, subse

quent to the judgment, and before the decision of the

appellate court, a law inteivenes and positively

changes the rule which governs, the lav/ must be obeyed,

or its obligation denied. If the law be constitutional,

. . . 1 know of no court which can contest its obligation

It is true that in mere private cases between individuals

a court will and ought to struggle hard against a con

struction which will, by a retrospective operation,

affect the rights of parties, but in great national

concerns, where individual rights, acquired by war,

are sacriiied for national purposes, the contract

making the sacrifice ought always to receive a con

struction conforming to its manifest import; and if the

nation his given up the vested rights of its citizens,

it is not for the court, but for the government, to

consider whether it be a case proper for compensation.

In such a case the court must decide according to

existing laws, and if it he necessary to set aside a

judgment, rightful when rendered, but which cannot be

affirmed but in violation of law, the judgment must be

set as i de.

United States v. Schooner Peggy, supra, 1 Cranch at 109.

Peggy may be interpreted in two ways: Under a narrow

interpretation the Court held only that, where the law changes

between the decision of the lower court and an appeal, the

appellate court must apply the new law if, by its terms, it

-44-

p u r p o r t s t o be a p p l i c a b l e t o p e n d i n g c a s e s . T h e d e c i s i o n a l

process, under this interpretation, requires the appellate

court to examine the intervening law and to determine whether

it was intended to apply to factual situations which trans

pired prior to the law's enactment. Since the treaty in Peggy

explicitly applied to situations where the controversy was

still pending, it followed that the statute should be applied

in deciding the case. Certainly the facts of Peggy and much of

the language of the opinion of Mr. Justice Marshall support

this interpretation.

By a broader interpretation, Peggy may be considered to

hold that where the law has changed between the occurrence of

the facts in issue and the decision of the appellate court and

where the controversy is still pending, the appellate court

must apply the new law, unless there is a positive expression

that the new law is not to apply to pending cases. This is

the interpretation of Peggy which found its final expression in

Thorpe. But before turning to Thorpe it is well to consider

intervening decisions.

- 4 5 -

In Vandenbark v. Owens-111ino)s Glass Co.. 311 U.S. 530

(1941), the Court held that a federal appellate court in

exercisir.q diversity jurisdiction must follow a state court

decision which was subsequent to and contradicted the district

court decision. In Carpenter v. Wabash Ry. Co., 309 U.S. 23

(1940), the Court held that the appellate court must apply an

intervening federal statute where the case is pending on appeal.

However, in Carpenter, the statute explicitly indicated that it

was to apply to pending cases. In United States v. Chambers,

291 U.S. 217 (1934), the Court held that indictments returned

pursuant to the eighteenth amendment, and before the adoption of

the twenty-first amendment, must be dismissed after passage of

the twenty-fiist amendment even though the acts when committed

were crimes. See also Ziffrin v. United States, 31R U.S. 73

(1943). Then, in Linkletter v. Walker, 381 U.S. 618 (1965),