Jett v. Dallas Independent School District Petitioner's Reply Brief

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1988

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Jett v. Dallas Independent School District Petitioner's Reply Brief, 1988. a6a40ff6-b59a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/3bb0a75a-793a-4e85-bf31-fc2198d02290/jett-v-dallas-independent-school-district-petitioners-reply-brief. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

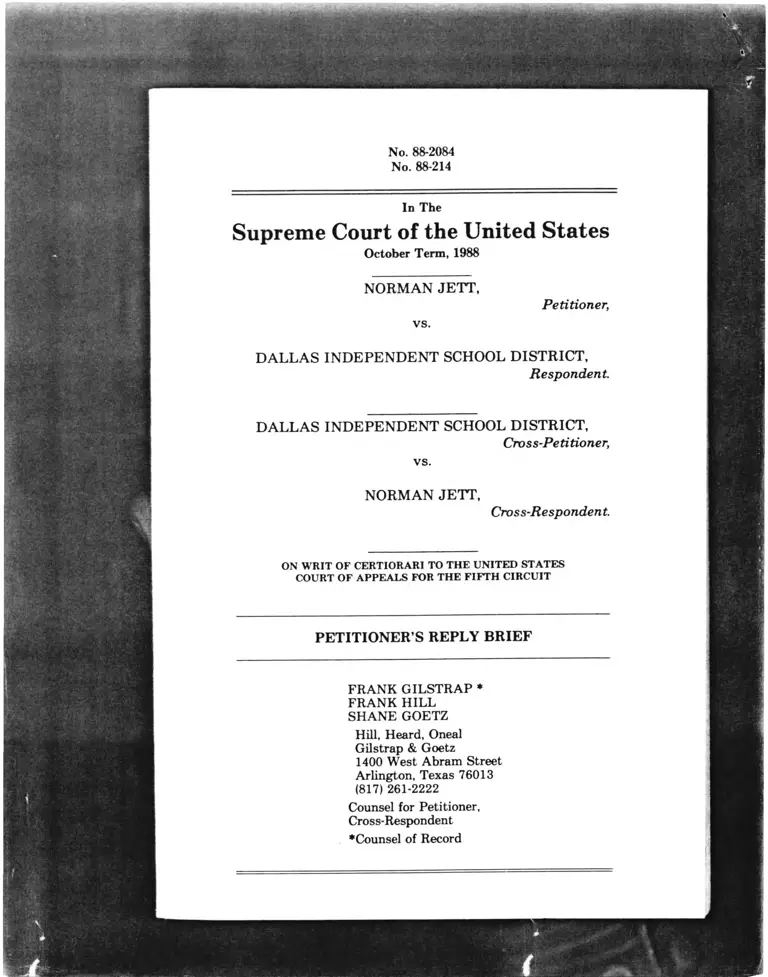

No. 88-2084

No. 88-214

In The

Supreme Court of the United States

October Term, 1988

NORMAN JETT ,

Petitioner,

vs.

DALLAS IN D EPEN D EN T SCHOOL DISTRICT,

Respondent.

DALLAS IN D EPEN D EN T SCHOOL DISTRICT,

Cross-Pe ti tioner,

vs.

NORMAN JETT ,

Cross-Respondent.

ON WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE UNITED STATES

COURT OF APPEALS FOR THE FIFTH CIRCUIT

PE TIT IO N ER ’S REPLY B R IE F

FRANK GILSTRAP *

FRANK HILL

SHANE GOETZ

Hill, Heard, Oneal

Gilstrap & Goetz

1400 West Abram Street

Arlington, Texas 76013

(817) 261-2222

Counsel for Petitioner,

Cross-Respondent

•Counsel of Record

INDEX

IN D E X ..........................................................................................1

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES.......................................................“

ARGUMENT.............................................................................. 1

I. Petitioner can sue directly under 42

U.S.C.§ 1981................................................................ 1

A. The court should not consider

Respondent’s new argument 1

B. Respondent’s argument is contrary

to longstanding precedent.................................... 3

1. Nineteenth Century precedent 3

2. Modern precedent 4

C. Civil suits against governmental

entities cannot be distinguished 6

1. Respondent’s position cannot be

squared with existing case law 6

2. The Court has already rejected

Respondent’s argument.................................. 7

3. Congress did not intend for

Section 1981 rights to be

enforced by Section 1983 suits 8

D. Congress intended that the 1866 Civil

Rights Act would be enforced by

civil su it...................................................................... I®

1. Statutory language 10

2. Legislative debates 13

E. Subsequent sessions of Congress have

approved the Section 1981 civil remedy 17

a. Section 1983 ...................................................... 1^

b. Refusal to amend Section 1981 18

c. The amendment to Section 1988 18

II. The rejection of the Sherman Amendment in

1871 is inapposite..................................................10

III. The assessment of the Monell facts in this

case should be dealt with on remand 20

CONCLUSION .......................................................................... 20

i

TABLE OF A U TH O RITIES

Cases P fl8e

Adickes v. Kress, 398 U.S. 144 (1970)................................. 3

Allen v. S ta te Board o f Elections,

393 U.S. 544 (1969) ....................................................... 12

Bell v. City o f Milwaukee,

746 F .2d 1205 (7th Cir. 1984).......................................... 5

Bell v. Hood, 327 U.S. 678 (1946)..........................................13

Bhandari v. First N at'l Bank o f Commerce,

829 F .2d 1343 (5th Cir.)(en b a n c ) ................................. 6

Blue Chip Stam ps v. Manor Drug Stores,

421 U.S. 723 (1975) ...........................................................18

Burnett v. Grattan, 468 U.S. 42 (1984) ............................... 9

Butner u. United States, 440 U.S. 48 (1979) 20

Bylew v. United States, 80 U.S. 638 (1872)........................ 12

Cannon v. University o f Chicago,

441 U.S. 677(1979)............................................... 11,12,18

Chapman v. Houston Welfare R ights Org.,

441 U.S. 600 (1979)..................................................... 8,12

City o f Canton v. Harris,

No. 86-1088, (February 28,1989) ................................. 3

City o f M emphis v. Green, 451 U.S. 100 (1981).................. 5

City o f Oklahoma City v. Tuttle,

471 U.S. 808 (1985)..................................................... 3,19

ii

City o f St. Louis v. Praprotnik,

485 U.S------- 108 S.Ct. 915 (1988)................... 3 ,10 ,19

Communications Workers o f Am erica v. Beck,

108 S.Ct. 2641,101 L .Ed.2d 634 (1988) ...................... 19

Deckert v. Independence Shares Corp.,

311 U.S. 282(1940) ..........................................................12

EEO C v. Gaddis, 733 F.2d 1373 (10th Cir. 1 9 8 4 ) ......... 5, 6

General Bldg. Contractors v. Pennsylvania,

458 U.S. 375 (1982) ......................................................... 5

Greenwood v. Ross, 778 F.2d 448 (8th Cir. 1 9 8 5 )............. 5

Hague v. C.I.O., 307 U.S. 496 (1939)................................... 1

Herman & MacLean v. Huddleston,

459 U.S. 375 (1983) ...........................................................18

H urd v. Hodge, 334 U.S. 24 (1948)........................................ 4

In re Hobbs, 12 Fed. Cas. 262 (C.C.D. Ga. 1971)............... 4

In re Turner, 24 Fed. Cas. 337

(C.C.D.Md. 1867).......................................................... 3,4

J.I.Case Co. v. Borak, 377 U.S. 426 (1964).......................... 12

J e tt v. Dallas I.S.D., 798 F.2d 748 (5th Cir. 1986),

on motion for rehearing, 837 F.2d 1244

(5th Cir. 1988)................................................................ 5,9

Johnson v. Railway Express Agency,

421 U.S. 454 (1976)............................................ 5 ,8 ,9 ,1 8

Jones v. A lfred H. M ayer Co.,

392 U.S. 409(1968)................................................... 4 ,7 ,8

iii

Leonard v. City o f Frankfort Electric & Water

Plant Board, 752 F.2d 189 (6th Cir. 1985).................... 5

Live Stock-Dealers' & Butchers' A ss 'n v.

Crescent City Live-Stock Land &

SlaughterH ouse Co., 15 Fed. Cas. 649

(C.C.D. La. 1 8 7 0 ).............................................................. 4

M ackey v. Lanier Collections Agency & Service, Inc.,

108 S.Ct. 2182,101 L.Ed. 634 (1988) .......................... 19

Mahone v. Waddle, 564 F.2d 1018 (3rd Cir. 1977) 5, 6,11

Marbury v. Madison, 5 U.S. 137 (1803)...............................^

Merrill Lynch, Pierce, Fenner & Smith, Inc. v.

Curran, 456 U.S. 353 (1982)...............................13,14,18

Metrocare v. W ashington Metropolitan Area

Transit Autho., 679 F .2d 922 (D.C. Cir. 1982) 5

McDonald v. Santa Fe Trail Transp. Co.,

427 U.S. 273 (1976) .........................................................

Meritor Savings Bank v. Vinson,

477 U.S. 57 (1986) ............................................................. iy

Miree v. DeKalb County, 433 U.S. 25 (1977) ......................3

Monell v. Dept, o f Social Services, n

4 3 6 U.S. 658 (1977)........................................ Z , U , L * , t v

Monessen Southwestern Ry. Co. v. Morgan,

108 S.Ct. 1837(1988).........................................................18

Moor v. County o f Alameda,

412 U.S. 693(1983).....................................................Ai’ 18

Runyon v. McCrary, 427 U.S. 160 (1976)...................... 5,18

IV

M iddlesex County Sewerage Authorities v.

Sea Clammers, 453 U.S. 1 (1981)................................... 13

Sethy v. Alameda County Water Dist.,

545 F .2d 1157 (9th Cir. 1976)...................................... 5 ,6

Shaare Tefila Congregation v. Cobb,

95 L.Ed.2d 5 9 4 (1987)..................................................... 5

Springer v. Seaman, 821 F.2d 871 (1st Cir. 1987)............. 5

St. Francis College v. Al-Khazraji,

107 S.Ct. 2022 (1987)....................................................... 5

Sullivan v. L ittle H unting Park,

396 U.S. 229 (1969)................................................. 4 ,5 ,12

Takahashi v. Fish & Game Comm'n,

334 U.S. 410 (1948)....................................................... 4 ,6

Taylor v. Jones, 653 F.2d 1193 (8th Cir. 1981) .................. 5

Texas v. Gaines, 23 Fed.Cas. 869,

(C.C.W.D.Tex. 1 8 7 4 ).........................................................12

Texas & Pacific Ry. Co. v. Rigsby,

241 U.S. 33, (1916)............................................................. 13

Thompson v. Thompson, 108 S.Ct. 513 (1988) 10

Tillman v. Wheaton-Haven Recreation A ss 'n,

410 U.S. 431 (1973) ......................................................... 4

Transamerica Mortgage Advisers, Inc. v. Lewis,

444 U.S. 11(1979) ............................................................. 13

Union Iron Co. v. Pierce, 24 Fed.Cas. 583

(C.C.D.Ind. 1969)............................................................... 13

United States v. Rhodes, 27 Fed.Cas. 785,

(C.C.D.Ky. 1866) ....................................................... 4,12

v

Statu tes

United S tates Code

42 U.S.C.

§ 1981..............................................................................passim

§ 1982 ............................................................................. 3-8,18

§ 1983.......................................................................1-10,18-20

§ 1985....................................................................................... 18

§ 1986....................................................................................... 18

§ 1988....................................................................................... 18

S ta tu tes a t Large

Civil Rights Act of 1866................................................. passim

§ 1 ............................................................................ 11,12

§ 2 ..................................................................................... 5

§ 3 .................................................................. 4 ,10 ,11 ,14 ,18

Civil Rights Act of 1 8 7 1 ........................................ 8 ,9 ,10 ,17

§ 7 ............................................................................................. 9

Civil Rights Act of 1964, Title V II ............................... 9 ,18

Miscellaneous

Cong. Globe, 39th Cong.,

1st Sess. (1866)................................................................. 13-16

Cong. Globe, 41st Cong.,

2d Sess. (1870)........................................................................17

Cong. Globe, 42nd Cong.,

1st Sess. (1 8 7 1 )......................................................................17

vi

ARGUMENT

I. Petitioner can sue directly under 42 U.S.C. § 1981.

The Fifth Circuit construed Section 1981 to include a “policy or

custom” requirement.1 We sought certiorari on that point,2 and

most of our brief addressed that issue.3 After we had briefed,

Respondent chose to raise what it calls “another — and more

serious — issue”.4 Respondent now says that local governments

are simply not subject to civil suit under Section 1981. According

to Respondent, a claim against a local government for depriva

tion of rights secured by Section 1981 can only be brought under

Section 1983. And, of course, Section 1983 contains a "policy or

custom” requirement.

There are three problems with this argument. First, it comes

too late (Part A below). Second, this Court has previously re

jected it (Parts B and C). Third, it fails on its merits (Parts C and

D).

A. The court should not consider

Respondent’s new argument.

Respondent’s claim that there is no civil cause of action under

Section 1981 is an afterthought, “and like most afterthoughts in

litigated matters it is without adequate support in the record.”5

The record contains no hint that Respondent has ever challenged

our right to sue directly under Section 1981. Indeed, Respondent

has conceded our right to sue under Section 1981 at all times.

In the District Court, The Respondent failed to contest our

right to sue in its Rule 12(b)6 motion to dismiss, its motion for

1 Pet. App. pp. 27A-30A.

2 Pet. pp. 9-29

3 Pet.Br. pp. 11-31.

4 Resp.Br. p. 14.

5 Hague v. C.I.O., 307 U.S. 496, 522 (1939) (Stone, J., concurring).

1

summary judgment, its portion of the proposed pretrial order, its

requested jury issues and instructions, its objections to the

jurycharge, Tr. 649-683, its motions for directed verdict, Tr.

597-612, 643-644, its motion for judgment n.o.v., and its motion

for new trial.

To the contrary, in its motion for directed verdict, Respondent

spoke of racial discrimination “for which Section 1981 was

adopted primarily and intended to redress.” Tr. 599. In its Rule

12(b)(6) motion, pp. 3-5, Respondent discussed the plaintiff’s

burden of proof under Section 1981 and concluded by suggesting

that Petitioner be required to replead “his 42 U.S.C.A. § 1981

claim.”

Before the Fifth Circuit, where Respondent was Appellant,

Respondent only argued that the rule of respondeat superior

should not apply to Section 1981.6 There is no suggestion that we

could not sue under Section 1981, and Respondent’s brief ex

pressly referred to “Section 1981 actions” on no less than eight

occasions.7

The Fifth Circuit accepted Respondent’s argument. It rejected

the application of respondeat superior and held that Section 1981

suits must meet a “policy or custom” standard. At the same

time, it accepted our right to bring suit directly under Section

1981.

The Respondent did not seek review of the Fifth Circuit’s deci

sion that we could sue directly under Section 1981. Nor did it sug

gest, either in its Response to our Petition or in its Cross-

Petition, that it had doubts as to whether such a suit could be

brought. Instead, it "acknowledg[ed] the need for further defini

tion of the ‘contours’ of municipal liability under 42 U.S.C. §

1981.” Reply to Pet., p.7, and said that the “Fifth Circuit correct

ly held that the requirements of Monell...would be extended to

claims for damages against municipalities based upon employ

ment decisions alleged to be in violation of 42 U.S.C.A. §1981.”

6 No. 85-1015, Brief of Appellants, pp. 2-3, 37-41, 60-68, and Brief of Appellants

in Response to Apellee’s Brief, pp. 6-7.

7 No. 85-1015, Brief of Appellants, pp. ii, 60, 61, 63, 64, 65, 66.

2

Cross Pet. p. 6. It was only after this Court granted certiorari —

and after we briefed — that Respondent first questioned the

longstanding precedent allowing civil suits directly under Sec

tion 1981.

The Court should decline to consider Respondent’s argument.

Instead it should decide the issue “squarely presented to and

decided by the Court of Appeals”8 9 and upon which this Court

granted certiorari.* “ It is most unfair to permit a defeated

litigant in a civil case tried to a verdict before a jury to advance

legal arguments that were not made in the district Court,

especially when that litigant agrees, both in its motions and its

proposed instructions, with its opponent’s view of the law.”10

B. Respondent’s argument is con

trary to longstanding precedent.

Respondent says Congress viewed the Civil Rights Act of 1366

"as limited to a criminal remedy.” Resp. Br„ p. 26. For 120 years,

however, the federal courts have allowed civil suits to enforce

that statute and its modern descendents, Section 1981 and 1982.

1. Nineteenth Century precedent.

Immediately after enactment of the 1866 Civil Rights Act,

three members of this Court, sitting as Circuit Justices, wrote

that the statute could be enforced by way of civil action in the

federal courts.

In In re Turner, 24 Fed. Cas. 337 (C.C.D.Md. 1867), a black ap

prentice sought release from her indenture because its terms did

not provide for the education which Maryland law guaranteed to

white apprentices. Chief Justice Chase granted her petition for

8 City of Oklahoma City u. Tuttle, 471 U.S. 808, 816 (1985).

9 See City of Canton v. Harris, No. 86-1088, (February 28, 1989), at n. 5; Miree v.

DeKalb County, 433 U.S. 25 (1977); and A diches u. Kress,

398 U.S. 144, 147 n. 2 (1970).

10 City of St. Louis v. Prapotnik, 485 U.S. ___ , 108 S.Ct. 915, 945-6 (1988)

(Stevens, J„ dissenting) (emphasis in opinion).

3

habeas corpus, holding that the indenture was “in contravention

of that clause of the first section of the civil rights law...which

assures to all citizens without regard to race or color, ‘full and

equal benefit of all laws and proceedings for the security of per

sons as is enjoyed by white citizens...’ ’’ 24 Fed. Cas., at 339.“

Three years later Justice Bradley permitted private parties to ob

tain injunctive and declaratory relief directly under the 1866 Act.

See Live Stock-Dealers' & Butchers' Ass'n v. Crescent City Live-

Stock Land & Slaughter-House Co., 15 Fed. Cas. 649, 655 (C.C.D.

La. 1870). Finally, in United States v. Rhodes, 27 Fed. Cas. 785,

786 (C.C.D.Ky. 1866), Justice Swayne construed the grant of

jurisdiction in Section 3 of the 1866 Act to include “causes of

civil action.”11 12

2. Modern precedent.

In Hurd v. Hodge, 334 U.S. 24 (1948), the Court used Section

1982 to strike down racially restrictive covenants in the District

of Columbia. While Section 1982 was raised as a defense in Hurd,

that was not the case less than a month later in Takahashi v. Fish

& Game Comm'n, 334 U.S. 410 (1948). There the court in

validated a California law denying fishing licenses to certain

aliens and allowed the plaintiff to obtain mandamus in state

court to enforce rights guaranteed by Section 1981. 334 U S at

419-420.

In Jones v. Alfred H. Mayer Co., 392 U.S. 409 (1968), the Court

held that Section 1982 reaches acts of private racial discrimina

tion in housing, and it allowed plaintiffs to obtain an injunction.

392 U.S., at 414 n. 14. Although Jones left open the issue of

damages, Id , that question was soon resolved. In Sullivan v Lit

tle Hunting Park, 396 U.S. 229 (1969), the court expressly allow

ed a plaintiff to recover damages under Section 1982, and in

Tillman v. Wheaton-Haven Recreation Ass'n 410 U.S. 431 (1973),

the Court allowed damages under both Sections 1982 and 1981.'

11 See also, In re Hobbs, 12 Fed. Cas. 262 (C.C.D. Ga. 1971), denying habeas

corpus because the state statute involvbd did not “conflict with the civil

rights bill.”

!2 In Jones v. Alfred H. Mayer Co., 392 U.S. 409, 457 n. 3, Justice Harlan read

Section 3 to give federal courts concurrent jurisdiction over "all cases in

which the specified rights were denied.’1

4

Finally, in 1976 the Court wrote ^ ^ g g ^ S l e d t o

establishes a cause of action un er [damages and

M t w r ,

C o - has

1 * 1 1 * * on - * « £ £ £ £ » “ \nZSStw o L e s

— g * “ i s

the 1866 Act. Private individuals do have a ngn

under Sections 1981 and 1982.

r> <197 it q 273 285 (1976);

13 McDonald v. Santa Fe shaare Tefila Congregation v.

Runyon v. McCrary, • • 160 ̂ L.Ed.2d 594 598 (1987); and St.

ZXi.Z*£L U.S. _ - 7 S.ct. 2022, 2026 ,1967).

14 In General Bldg. Con̂ r̂ o d t y h o U ^ ' that "a cause of ac-

U S., at 403 (emphasis added). In U ty I f plaintiff “had a

« » , . * . € » » « chm cteratd Sutouo “

cause of action under § 1982" <emphasis added). 451 U.S.,

phasis added)

„ s „ u. V fo.toa.oo M otop otoo Ar.tI Troo... AuU. « «

S d 922. 92, ID.C. CIT. 19821V S p r ie r u « U S.

198,1: Mahan, u. j ‘ K 2d , « l5th Cir. 19861. o» " toon for

904 1988,: an, o. City ™

rehearing, 837 r .2d 1244 iou , 74fi p od 1205 (7th Cir.

F.2d 189 (6 th Cir. igSS); BeM v CUy iw ^ l981); Greenwood v.

1984); Taylor v. Jones, 653 F.2d . A iameda County Water

S Z £ a r S . ' S i W i o C o. a — 133 «

1373, 1380 (10th Cir. 1984).

5

C. Civil suits against governmental

entities cannot be distinguished.

1. Respondent’s position cannot be

squared with existing case law.

Respondent attempts to distinguish our case because the

efendant is a local government. Respondent implies that this

court has limited its Section 1981 holdings to private parties.

Resp. Br. p. 17. Yet Section 1981 plaintiffs were allowed to

~ ? r st the State 0f California in Takahashi, supra, 334

Respondent also concedes that certain kinds of civil suits can

be brought against local governments under Section 1981. It

agrees that Congress intended to allow civil suits under the 1866

Act to obtain habeas corpus relief. Resp. Br. p. 29, and to enforce

e rights to sue, be parties, and give evidence...and to the full

and equal benefit of all la w s .”

Resp.Br pp. 26-27 n. 31. Additionally, Respondent conceded

before the Fifth Circuit that federal courts “have equitable power

to order remedial relief, where the discrimination occurs bv

employees, such as back pay, reinstatement, and injunctive

relief. These concessions render the Respondent’s position

untenable.

First, our claims are not limited to damages. Petitioner

16 All of the Circuit Court cases in the preceding footnote involved suits

against local governmental entities, except for Gaddis. Respondent

dismisses these as the result of “offhanded sub silentio assumptions”. Resp

Br. p 18. Yet, that is hardly a fair description of Sethy, where the en banc

Ninth Circuit allowed Section 1981 recovery against a municipal water

district, or Bhandan o. First Nat'l Bank of Commerce, 829 F.2d 1343 (5th

Cir.) (en banc, where the Fifth Circuit decided that a Section 1981 claim for

alienage discrimination can be brought only against the state. Nor does this

do justice to the Third Circuit's monumental effort in Mahone, whose dis

sent provides most of Respondent's arguments.

17 Brief of Appellants, No. 85-1015, p. 7.

6

also sought backpay and attorney’s fees ̂ J t -APP; P- 7 'J

«Wnnd it’s difficult to extract a coherent rule of la

£ and give evidence ' - plus claims ansmg under the full and

^ " p o n d e E s position will sub;ect * * » £ £ * « £

1866 Congress could not have intended such an anomaly.

2. The Court has already reject

ed Respondent’s argument.

S T S S ' £ £ £ £ . Ute Respondent Argued as foUows:

nowhere in this entire first section of the original

[1866 Civil rights Act] is there any mention of any

remedy or right to sue for any kind of relief . • • UF

does no more than make a general statement o fw

s ti tu t io n a l policy

, , , . f hc H„tp he •'resigned” rather than report to his18 Petitioner was paid through the da The jury found that

new assisgnment as ninth grade ia s set aside by

Petitioner . . . consmietiv.i,. « p ,tl,

the Fifth Circuit which concluded a. a matter ot ? Respon-

ordeal was chaUenged, but this is incor-

? r . on that question. we did preserve

it. Pet. App. p. i. Question 4.

7

purpose now served by [it] is an incomplete compendium of

rights the violation of which may give rise to civil suit under

. . . Section 1983 of 42 U.S.C. . . .

[T]he section of the Act out of which present Section 1982

was carved was simply a “general statement of constitu

tional policy” and by itself afforded no civil. . . remedy.. . .

[A]t the time of its enactment the Act contained no civil

remedy at all . . . . [A] civil remedy was added in 1871.19

The Court rejected this argument in Jones, 392 U.S., at 414 nn.

13-14 (citing cases). It is now settled that the 1871 Act “created a

new civil remedy, neither repetitive of nor entirely analogous to

any of the provisions of the earlier Civil Rights Acts.” Chapman

v. Houston Welfare Rights Org., 441 U.S. 600, 651 (1979) (White,

J. concurring).

3. Congress did not intend for

Section 1981 rights to be en

forced by Section 1983 suits.

a. Congress intended to provide for

different civil remedies under

Sections 1981 and 1983.

Respondent argues that the civil cause of action under Sections

1981 and 1982 is purely judge-made: it was necessary for the

Johnson Court to “create” such a remedy, since there was no ex

isting remedy for racial discrimination by private employers.

Therefore, we are told, there is no need for the Court also to

“create” a civil cause of action against government employers

under Section 1981, since Section 1983 is already available to

remedy employment discrimination by those defendants.

Resp.Br. pp. 16-17.

Respondent’s argument is premised on the notion that, when

Johnson was decided in 1976, there was no statute to remedy

racial discrimination by private employers. But this is simply

19 No. 645, Oct. term, 1967, Brief for Respondents, pp. 40-41 (emphasis omit

ted).

8

wrong. Twelve

Johnson the plaintiff brough t ^ &rgument that since the

VII. The Johnson Court 3 1 he could not sue under Sec-

employee could sue underTitl VI ^ empi0yee to have both

tion 1981. Congress 1 g;m,iarlv. Congress intended for the

remedies. 421 ? 1981 and 1983 to be independent of one

remedies under Sections 1981^ 42 (1984) (“ - th e in-

de^nX en^’oHhTremedi^^heme established by the reconstmc-

tion Era Acts.”)

b. Congress b T

„t action under the 1866 Act by

including a saving clause in the

1871 Act.

•f Pnn press intended to allow civil

Respondent says that, w en C J P changed ^ this by enac

t i o n s under Section 1981, it som ^ The Fi{th Circuit

ting Section 1983. The statute, Congress somehow

reasoned that by enactmg: tta J; ent onto the a c t in g

engrafted a pohcy or custo q mng brief, we showed

Section 1981 cause of acton- the knotty problems of “repeal bythat this argument ran afoul of the toot y p ^ ^

impUcation.’ Pet. Br- PP' DistricV The Applicability of

Dallas Independent S c h o o D ^ u S.C. Section 1981.

Municipal Vicarious Liability Un ^ 240.242 (1988).

Notre Dame Law Rev. Vo . . when Congress enacted the

Now the Respondent remedy under the 1866

1871 Act, it repealed the existing ^ Section 1983, as the

Act. This left the 18 Section 1981 violations, according to

exclusive civil reme y would be a repeal by implication,

in our opening brief appfy here

with equal force. through those arguments again.

Yet. there is no MedUo t dg ^ *g71 Act reads as follows:

The saving clause in bectio

the same may be repugnant thereto.

9

Jt.App. p. 106. Thus, Congress intended that the 1871 Act (Sec

tion 1983) would have no effect on the 1866 Act (Section 1981).

D. Congress intended that the 1866 Civil Rights Act

would be enforced by civil suit.

Although the 1866 Act contained no provision expressly grant

ing a right to sue, there is ample evidence that Congress “actual

ly had in mind the creation of a private cause of action.” Thomp

son v. Thompson, 108 S.Ct. 513, 516 (1988). We examine, as

always, the “language and history”20 of the statute.

1. Statutory language.

Section 3 of the 1866 Civil Rights Act is set forth below. The

various clauses are numbered for reference.

[FIRST CLAUSE]

The district court...shall have, exclusively of the courts of

the several states, cognizance of all crimes and offenses

committed against the provisions of this act, and also, con

currently with the circuit courts..., of all causes, civil and

criminal, affecting persons who are denied or cannot enforce

in [state courts] any of the rights secured to them by the

first section of this act;

[SECOND CLAUSE]

and if any suit or prosecution, civil or criminal [is] com

menced in any State court against any officer, civil or

military, or other person [for certain specified acts], such

defendant shall have the right to remove such cause for trial

to the proper district or circuit court in the manner pre

scribed by the [1863 Habeas Corpus Act],

20 City of St. Louis v. Praprotnik, 108 S.Ct. 915, at 923 (plurality).

10

[THIRD CLAUSE]

The jurisdiction in civil and be exercised and

red on the district and circui United States,

[FOURTH CLAUSE]

but in all cases where such ^ ^ ^ ^ t s s a r y to furnish

ject, or are deficient in th p g against the law, the

suitable remedies and pu ern said courts in the

common law shod be extended'andgovern &

" , S S r o \ t — on the <ound

guilty.

Jt. APP. P- 85 (emphasis added) y g ^ (l973)t the co u rt* .

In Moor v. County concluded that “]t]he in-

reviewed the Lablished federal jurisdiciton to

itial portion of § 3 of the . ., d brought to enforce § 1 ■

hear, among other things c italicized language in the

411 U.S. at 705 (emphasis addedb Individual “persons

First Clause is consistent w tQ enforCe “any of the rights

could bring suits (“c ^ cau ^ n0 other way to ex-secured by” section 1 of the Act.

plain this language. , t Section 3 merely "permit-

P It has been argued, f“ / M“ ° t r Ĉ th e? rig h ts in state court to

ted defendants who could not e n h ^ court.»., But, on-

remove the proceedings g Clause, however, does

ihe First

Clause included plaintiffs.

______ _______ _ _ . . . n c 677 736 n. 7 (1979)

21 s„ ^ , c

J- F 2d 1018. .010 Cir. 19771.

22 Mahone v. Waddle, 564

ting).

11

Respondent argues for another interpretation: this language

merely “was meant to allow a person to bring a state law claim in

to the federal courts when some state law requirement precluded

it from being litigated in the local system.” Resp.Br. p. 26 n. 31.

Specifically, we are told, Congress had in mind state statutes

which prohibited blacks from testifying against whites. Id. While

this view was advanced at one time23, it was ultimately rejected

by the Court.24

Additionally, such an approach would involve only part of the

rights secured by Section 1, i.e., the right “to sue, be parties, and

give evidence.” Congress, however, again spoke in broader terms.

The First Clause allows “civil causes” to “enforce” “any of the

rights ” secured by Section 1.

This Court has consistently construed this kind of broad,

jurisdictional language as evidencing Congressional intent to per

mit civil suits. Thus in Deckert v. Independence Shares Corp.,

311 U.S. 282 (1940), the Court construed a grant of jurisdiction

“over all suits in equity and actions at law brought to enforce any

liability or duty created” by a particular statute. The Court held

that this conferred a right to sue. 311 U.S., at 288.26

Similarly, the Court has also found evidence of Congressional

intent to create a civil cause of action in broad declarations of

rights, such as found in Section 1 itself.26

Moreover, in evaluating Congressional intent, the Court “must

take into account [the] contemporary legal context.”27 The 1866

C ongress had every reason to expect

23 C(, United States v. Rhodes, 27 FecLCas. 785, 787-788 (C.C.D.Ky. 1866), with

Texas v. Gaines, 23 Fed.Cas. 869, 870-871 (C.C.W.D.Tex. 1874).

24 See Bylew v. United States, 80 U.S. 638, 641 (1872). See also, Chapman v.

Houston Welfare Rights Org., 441 U.S. 600, 631 n. 11 (1979).

25 See also, J.I.Case Co. u. Borak, 377 U.S. 426, 428 n.2 (1964); Allen u. State

Board of Elections, 393 U.S. 544, 561 {1969);SuIlivan, 396 U.S., at 238.

26 In Cannon v. University of Chicago, 441 U.S. 677 (1979), the Court noted

that ‘‘this Court has never refused to imply a cause of action where the

language of the statute explicitly conferred a right directly on a class of per

sons that included the plaintiff in the case.” 441 U.S., at 690 n. 13. The Can

non Court cited the language of Sections 1981 and 1982 as its primary ex

ample.

27 Cannon. 441 U.S., at 698-699.

12

that the courts would pemut ^ & dvil remedy. The 39th

even absent specific languJ** i U rights, and in Marbury v.

Congress was c o n c e m ^ t h a 7 that “[t]he very

Madison, Chief Justice Mars the right of every in

essence of civil liberty certainly whenever he receives

dividual to claim the p r o t e c ^ ^ in the absence of

an injury”.28 The practice ^ ^ ^ X s t a b U s h e d by the Civil

specific statutory authorlzatl°n ^Ush comm0n law authorities.30

War29 and can be traced to E g following a common law tradi-

During this period federal court , a3 ^ exception rather than

tion regarded the denial of a y . that Congress omitted

the rule.”33 Thus it is hardy right to sue under the

statutory language expressly creating B

Civil Rights Act.

2. Legislative Debates

a. The 1866 Debates

On the day he .ntroduced the Civd Rights bill. Senator Trunv

bull declared:

Thle thirteenth, —

United States should be free-- bgtract truths and pnn-

tance in the g e n e r a d°L“ o X t , unless the per-

^ r j e " S W S T have some means o «

themselves of their benefits.

28 5 U.S., at 163. c.D.Ind. 1969). and cases

29 See Union Iron Co. v P i ‘ rCe' ^ \ j L j J ' 241 U.S. 33, 36 (1916). and Bell v.

cited at Texas & Pacific Ry ■ Co‘ V ^ . ' gg a/so, National Sea Clammers

r » z - 3M-375 4

nn' 53& 54' „ U 1 „ s at 689 n. 10; Transamencav.

• — t — > *s c t- “ 3,4 ”■

52.

31 & 32. Footnotes 31 & 32 deleted.

33 Curran, 456 U.S. at 375-376.

, „ , Sess 474 (1866) (emphasis added).

34 Cong. Globe, 39th Cong., 1st Ses

13

Trumbull described Section 3 as creating federal jurisdiction

over the cases of persons who are discriminated against by

State laws or customs".- In the subsequent debate, before the

t0 °Verride President Johnson’s veto, Trumbull

J v ! Z ° T n ° f SeCti°n 3 in which “Jurisdiction is given to the Federal courts of a case affecting the person that is

discriminated against.”38

Where for example, a discriminatory state law or custom was

being enforced against an individual:

then he could go into the Federal court---- If it be necessary

in order to protect the freedmen in his rights that he should

have the authority to go into the Federal courts in all cases

where a custom prevails in state, or where there is a statute-

law of the state discriminating against him, I think we have

the authority to confer that jurisdiction under the second

clause of the [Thirteenth] amendment. . . . That clause

authorizes us to do whatever is necessary to protect the

freedman in his liberty. The faith of the nation is bound to

do that; and if it cannot be done without, [we] would have

authority to allow him to come to the federal courts in all

cases.35 36 37

Opponents of the bill understood that it authorized a civil cause

of action.

[T]has bill sends the people with their causes into the courts

of the Umted States---- I am not so much afraid of any law

that sends the people to the courts as I am of a law which

places them under the control and power of irresponsible of

ficials------Sir, what is this bill? It provides, in the first

’ that the civd fights of all men, without regard to color

shall be equal; and, in the second place, that if any man shall

violate that principle by this conduct, he shall be responsi

ble to the court; that he may be prosecuted criminally and

punished for the crime, in a civil action and damages

recovered by the party wrongful Is that not broad

35 Id. at 475.

36 Id at 1759.

37 Id at 1759 (emphasis added).

14

enough?38

Senator Cowan criticized the provision for a civil remedy as

delusion and a snare”38 because the federal courts were located so

far from most claimants, and the cost of litigation there was so

high.

Respondent argues that Congress “rejected the right to a

damage action” when it disapproved a motion by Representati

Bingham to recommit the bill. Resp. Br. p. 25. Responden

describes Bingham as “one of the foremost supporters of civil

riehts” Reap Br. p. 24, but Bingham was in fact one of the

leading’opponents of the 1866 Civil Rights Bill, and he ultimate

ly voted against it. ... f

I t ’s inaccurate to describe Bingham’s p rop osa l as providing for

a civil action. Bingham moved to recommit the bill with two in

structions. First, he advocated deleting the general language pro

hibiting all forms of racial discrimination. See Resp. B r p. 44,

Cong. Globe, 39th Cong., 1st Sess. 1271-72, 1291. Second,

Bingham proposed

to strike out all parts of said bill which are penal and which

authorized criminal proceedings, and in lieu thereof to give

to all citizens injured by denial or violation of any of the

other rights secured or protected by said act an action in t e

United States courts with double costs in all cases of

recovery, without regard to the amount of damages.

Id (emphasis added). Respondent suggests that this was a pro

p e l™ add to the remedies in the 1866 Act, and that in consider

ing the Bingham motion Congress “grappled_with the availa

tygof a right of action to enforce section 1 and explicitly rejecte

it ” ResD. Br. d. 25 (emphasis added).

But neither Bingham, nor any member of the House w h o a -

dressed his motion, regarded it as a proposal to add anything to

the enforcement of the Act. It was regarded as a p ro p o s^ o

, emove the criminal remedy. Bingham s speech in support of his

38 Id at 601 (emphasis added).

39 Id at 1782-1783.

40 Footnote 40 deleted.

15

motion was a lengthy diatribe against the 1866 Act, particularly

the anti-discrimination provision.41 With regard to the second

part of his motion, quoted above, Bingham’s only explanation

was as follows:

You propose to make it a penal offense for the judges of the

States to obey the constitution and laws of their states, and

for their obedience thereto to punish them by fine and im

prisonment as felons. You cannot make an official act, done

under color of law, and without criminal intent and from a

sense of public duty, a crime.42

Bingham insisted that the effect of his proposal was “to take

from the bill what seems to me its oppressive and I might say its

unjust provisions.”43

Although the supports of the 1866 Act generally op

posed Bingham s proposal, none of them expressed any opposi

tion to the existence of civil remedy or suggested that such a

remedy was any less appropriate than the disputed penal provi

sion. On the contrary, Representative Shellabarger argued:

What difference in principle is there between saying that the

citizen shall be protected by the legislatie power of the

United States in his rights by civil remedy and declaring

that he shall be protected by penal enactments against

those who interfere with is rights? There is no difference in

the principle involved.44

Nothing in the debates on Bingham’s motion suggests that Con

gress thought it was *grappl[ing] with the availability of a right

of action to enforce section 1”. What Bingham intended to bring

about, and all that Congress “grappled with”, was the deletion of

the criminal sanctions for the enforcement of Section 1. No

representative who spoke in favor of or against Bingham’s mo

tion treated it as adding anything to the civil rights bill.

41 Id. at 1291-93.

42 Id at 1293; see also id. at App. 157 (Rep. Delano).

43 Id at 1291.

44 Id at 1295.

16

b. Subsequent Debates

Respondent also

of subsequent sessions g? 1070 "Itlhe remarks of

— - t ^ r a A V L A c t w a s

Senator Pool, . . . present ,, R Br p. 27 (em-

solely to be enforced as a Senator

phasis added). The word solely does not PP« ^ (1 8 m

that wheref ! J t sheUabarger did not say that the 1866 Act was (emphasis added). ShellaDa g P i st Sess App. 68

Amendment fox‘ d was the affirmative duty to stop

obligation to which he obj . r , t -795 quoted in

M 4 M U S ate67C13tyBU “ could not have meant, as Respon-

“ g g ^ ; that - n i c i p ^ a b m ^ b ^ o n = ? nr

superior was without a superior to claims against

1866 the application of respond P virtually every

muncipalities had been accepted by courts in virtu

state.46

E Subsequent sessions of Congress have

approved the Section 1981 cm l remedy

a. Section 1983

c t-nn 1 of the Ku Klux Klan Act of 1871 provided that defen- Section 1 of the tvu jmua to be prosecuted in

dants would be "liable in an rights of appeal,

the [federal courts], “ 1 “ ^ “ 'S In like c Z s in

review upon error, and oth Rights Act of

- h courts u n d e r I k e P—̂ * » - < * * ght t0 „

2 r S Z . Z "Ot exist, then why the reference to

“like cases”?

_ f thp N AACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund.45 Brief Amicus Curiae of the N AALr i>ega

Inc., et aL, at pp. 22-47.

17

b. Refusal to amend Section 1981

As shown, the courts have upheld the right to enforce Section

1981 by civil suit almost from the beginning. This fact, coupled

with Congress’ refusal to amend the statute, is itself evidence

that Congress approved the availability of a civil action under

Section 1981.48 Thus, when Congress enacted Title VII, it noted

“that the remedies available to an individual under Title VII are

co-extensive with the individual's right to sue under... § 1981.”

Johnson, 421 U.S., at 459. “Later in considering the Equal

Employment Opportunity Act of 1972, the Senate rejected an

amendment that would have deprived a claimant of any right to

sue under § 1981.” Id.

c. The amendment to Section 1988

In Moor v. County of Alameda, 411 U.S. 693 (1973), the Court

traced 42 U.S.C. § 1988 to the Fourth Clause of Section 3 of the

1866 Act. 411 U.S. Id., at 705. It was “plain on the face of the

statute” that section 1988 was “intended to complement the

various acts which do create federal causes of action for the viola

tion of federal civil rights,” 411 U.S., at 702, including “42 U.S.C.

§§ 1981, 1982, 1983, 1985,” 411 U.S., at 702, n. 13, and that

“Congress...directed that § 1988 would guide the courts in the en

forcement of a particular cause of action, namely that created in §

1981.” Id., at 705 n. 19.

In 1976, however, the Court refused to construe Section 1988 to

allow the award of attorneys fees in an action brought directly

under Section 1981.46 47 Four months later Congress passed the

Civil Rights Attorneys’ Fees Awards Act, which amended Sec

tion 1988 to allow recovery of attorneys fees “[i]n any action or

proceeding to enforce a provision of sections 1981, 1982, 1983,

1985 and 1986...” 42 U.S.C. § 1988.

46 Cannon, 441 U.S., at 703 & nn. 7 & 40; Blue Chip Stamps v. Manor Drug

Stores, 421 U.S 723, 732-733 (1975); Merrill Lynch, Pierce Fenner <£ Smith,

Inc. v. Curran, 456 U.S. 353, at 381-382 (1982); Herman & MacLean v. Hud

dleston, 459 U.S. 37511983), Monessen Southwestern Ry. Co. v. Morgan, 108

S.Ct. 1837, 1844 (1988).

47 Runyon, 427 U.S., at 184-185.

18

II The rejection of the Sherman

' Amendment in 1871 is inapposite.

In Part „ ot us

1981 4 “policy ° r custom"

from certain cru^ ^ ™ ! missing from Section 1981, it can-

Since those crucial terms are* nufs g t> pe(. Br pp. 2l-26.

not contain a "policy or_ cust jj custom-- requirement

Respondent replies hat the pohcy o ^ ^ ^ ^

does not depend entirely on p raprotnik, were "brac-

that while Monell, Tu* * ’ ê Section 1983, the language of theed...on the specific wording of Sectio ^ ^ C(mrt built.“

act was not the only f°un<jlat JJ there is another basis for

Resp.Br. p. 38. Respondent IJ on^ rejection

the “policy or custom req ’ at 53.39. o f course we

of the Sherman Amendment • ̂^ 1866i and this Court

are concerned mth the> ^ a^ubseqUent Congress form a

has often noted that intent of an earlier one. 48

hazardous basis for inferring glossing over a vital

Respondent ^ ^ ^ M ^ n e l t h e Court taught that the

distinction. In footnote ting the Sherman Amendment

1871 Congress intended- by rej^tm gtn ^ municipalities.

_ to reject respondeat sup rejecting the Sherman

However, it does not M ow that. by re)«t g ^ ^ ^

Amendment, Congress also ' superior simply

custom" standard. A rejec "policy or custom.” The

does not equate to an exclusive There are. in fact,

two concepts are ^ “ oHemof S o u s liability. Cf., e.g,several approaches to the problem 6? 10g S Ct 2399,

Meritor Savings Bank v. 1 , “policy or custom” merely

2410 (1986). Respondeat superior an p y

represent the two extremes. Sherman Amendment is

e J i r ^ S ^ / ' £ n o t hewant municipalities to

• s - — ..

a1 “ a '.08 sL“ 2e6«.tO,L.Ed,de34IWSSMB—

curring).

19

be held liable on a respondeat superior basis, it is not evidence

that that Congress also believed that the proper standard was

policy or custom. The “policy or custom” requirement can only

come from the “crucial terms” of Section 1983.

We have demonstrated that these crucial terms cannot apply to

Section 1981, and Respondent has not challenged this. Thus, the

“policy or custom” requirement cannot apply to Section 1981.

III. The assessment of the Monell Facts in

this case should be dealt with on remand

Respondent s only discussion of the Monell issue is found in a

series of scattered footnotes,4® which raise a fact-bound issue:

whether the General Superintendent of the Dallas Independent

School District is a policymaking official within the meaning of

Monell The Superintendent is the chief executive officer of a

large metropolitan school district. He directs 15,000 employees

and oversees the education of more than 100,000 students. In the

face of this Respondent insists, apparently seriously, that the

Superintendent “is not a policymaker”. Resp.Br. p. 7.

The fact specific issue of whether the Superintendent has

authority to make policy is not — particularly at this juncture —

an appropriate issue for resolution by this Court. First this simp

ly is not the issue which Respondent originally asked this Court

to review. Second, the Fifth Circuit expressly did not decide

whether the Superintendent had policymaking authority. That

issue should be resolved in the first instance by the lower courts

“who deal regularly with questions of state law in their respec

tive [courts] and [who] are in a better position than [this Court] to

determine how local courts would dispose of comparable issues.”

Butner v. United States, 440 U.S. 48, 58 (1979).

CONCLUSION

The Court should affirm Petitioner’s Section 1981 recovery

against Respondent. The Section 1983 portion of the case should

be remanded to the District Court.

Respectfully submitted,

FRANK GILSTRAP*

1400 West Abram Street

Arlington, Texas 76013

(817) 261-2222

•Counsel of Record for Petitioner

49 Brief for Respondent, p. 7 nn. 9-11, p. 8, nn. 12, 14, p. 36, n. 36.

20