Wells v. Reynolds Jurisdictional Statement

Public Court Documents

October 4, 1965

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Wells v. Reynolds Jurisdictional Statement, 1965. cbc13ad4-c89a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/3bd09328-c51f-4989-8511-6ae71dc905b9/wells-v-reynolds-jurisdictional-statement. Accessed February 22, 2026.

Copied!

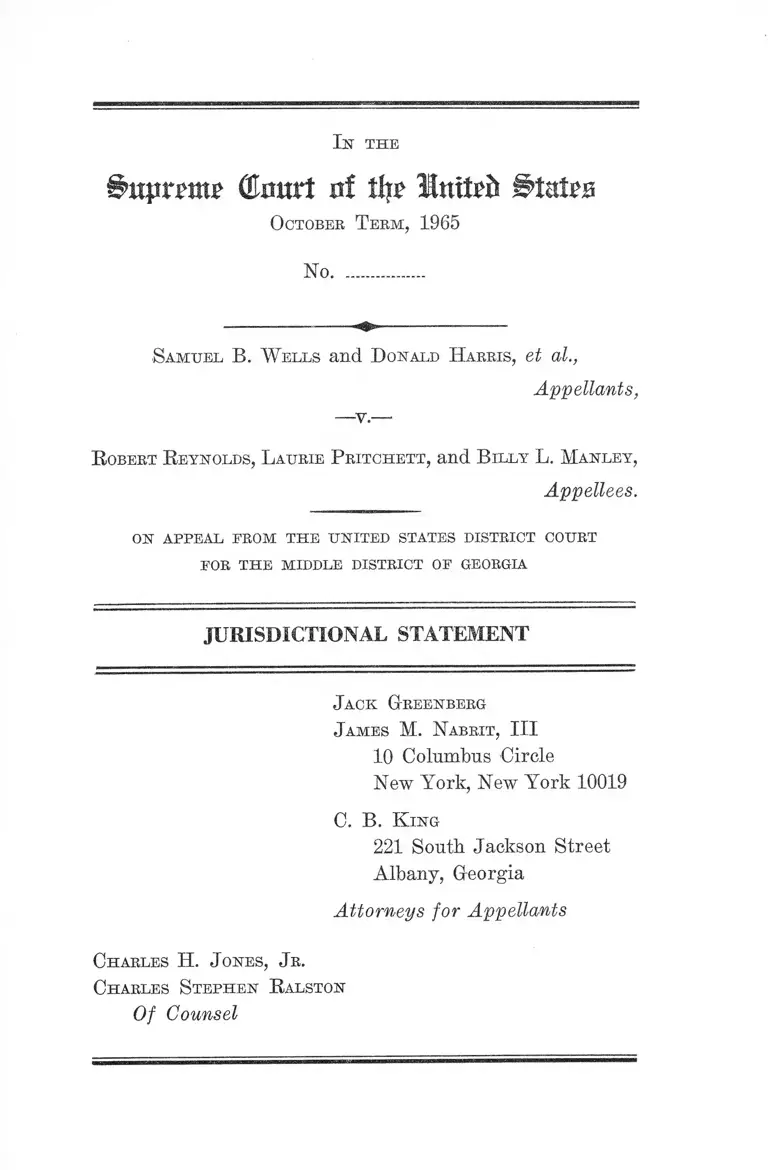

In t h e

&vipvmz (tort of tfyt Imtrlt Stairs

October T erm, 1965

No..................

Samuel B. W ells and D onald Harris, et al.,

Appellants,

—v.—

R obert R eynolds, L aurie P ritchett, and B illy L. Manley,

Appellees.

ON a p p e a l p r o m t h e u n it e d s t a t e s d is t r ic t c o u r t

FOR THE MIDDLE DISTRICT OF GEORGIA

JURISDICTIONAL STATEMENT

Jack G r e e n b e r g

James M. Nabrit, III

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

C. B. K ing

221 South Jackson Street

Albany, Georgia

Attorneys for Appellants

Charles H. J ones, J r.

Charles Stephen R alston

Of Counsel

I N D E X

Opinion Below ............. ............................... —~------------- 1

Jurisdiction ................... ....... ...........................---- -------- 2

Questions Presented........... ................... ..... ...............—- 3

Statutes Involved .......... .............................. .............— 3

Statement ................. ................ .... ............-.................... - 4

The Questions Are Substantial ...................... ............... 12

Conclusion ......................................................................... 28

Appendix: Opinion Below ................... ................. ......... la

Table op Cases

Aelony v. Pace,------F. Supp.------- , 8 R. Eel. L. Eep.

1355 (M. D. Ga., Nos. 530, 531, 1963) ...................... 16

Butts v. Merchants & M. Transp. Co., 230 U. S. 126 .... 22

Cameron v. Johnson, ------U. S. ------- , 33 U. S. L. W.

3395 ............................ ................ ........................ --2 ,14 , 27

Carr v. State, 176 Ga. 55, 166 S. E. 827 (1932) ___ 23

Chaplinsky v. New Hampshire, 315 U. S. 568 23

Dalton v. State, 176 Ga. 645, 169 S. E. 198 (1933) ----- 23

Dombrowski v. Pfister, 380 U. S. 479 ..... .....2,11,12,13,14,

17,18, 20, 25, 27

PAGE

Douglas v. Jeannette, 319 U. S. 157 ............................... 2

Gitlow v. New York, 268 U. S. 652 ............................... 23

Herndon v. Lowry, 301 U. S. 242 ...................12,14,15,16,

18,19, 20, 23

Jones v. Opelika, 316 IJ. S. 584 (dissenting opinion),

adopted per curiam on rehearing, 319 U. S. 103 .... 22

Loomis v. State, 78 Ga. App. 336, 51 S. E. 2d 33 (1948) .. 22

Statham v. State, 84 Ga. 17, 10 S. E. 493 (1889) ....... 22

Thornhill v. Alabama, 310 U. S. 88 ............................... 21

United States v. Eaines, 362 U. S. 17 ........................... 21

Wells v. Hand, 238 F. Supp. 779 ..... ................................. 1

Williams v. Standard Oil Co., 278 U. S. 235 ......... ..... 21, 22

Winters v. New York, 333 U. S. 507 ............................... 20

Federal Statutes:

28 U. S. C. §§1253, 2101(b) ........................................... 2

28 U. S. C. §1343 ................................................ 2

28 U. S. C. §§2281, 2284 ..... 2

42 U. S. C. §§1971, 1981, 1983 ......................................... 2

ii

PAGE

State Statutes:

Ga. Code Ann. §26-901

Ga. Code Ann. §26-902

....................3,15,16

....3, 9,10,11,15,16,

18, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27

I ll

Ga. Code Ann. §26-903 ....... ....... ......... ........ ................ 4, 9,15

Ga. Code Ann. §26-904 ........................ ...3, 4, 9,10,11,12,13,

15,16,17,18,19, 21,

22, 23, 24, 25, 26

Ga. Code Ann. §26-5320 ................ .................................... 22

Other Authority:

Note, 61 Harvard Law Review 1208 ............ .............. 22

PAGE

I n t h e

(Emtrt of tlj£ linxtvft States

October T erm, 1965

No..................

Samuel B. W ells and D onald H arris, et al.,

Appellants,

— v .—

R obert R eynolds, L aurie P ritchett, and B illy L. Manley,

Appellees.

ON APPEAL FROM THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

FOR THE MIDDLE DISTRICT OF GEORGIA

JURISDICTIONAL STATEMENT

Appellants appeal from the judgment of the United

States District Court for the Middle District of Georgia

entered on February 24, 1965, denying their prayer for

injunctive relief, and submit this statement to show that

the Supreme Court of the United States has jurisdiction of

the appeal and that substantial questions are presented.

Opinion Below

The opinion of the District Court for the Middle Dis

trict of Georgia, Albany Division, is reported in 238 F.

Supp. 779, under the name Samuel B. Wells, Donald

2

Harris, et al. v. Fred Hand, Jr., et al. A copy of the opin

ion, including findings of fact, conclusions of law and judg

ment, is attached hereto as an Appendix.

Jurisdiction

This suit was brought under 28 U. S. 0 . '§<§,1343(3) and

(4) and 42 U. S. C. <§§1971, 1981 and 1983. A three-judge

court was convened pursuant to Title 28 U. S. C. '§‘§2281

and 2284. The suit was brought to enjoin threatened crimi

nal prosecutions under Georgia statutes alleged to be un

constitutional on their face and as applied as abridging

freedom of speech, assembly, and the right to petition.

The judgment of the District Court was entered on Febru

ary 24, 1965 and notice of appeal was filed in that court

on March 27, 1965. Subsequently, a motion to reconsider

its opinion was filed in that court on May 17, 1965. On

May 22, 1965, an application for an extension of time to

docket the appeal and file the record was made to the

presiding judge of the District Court pursuant to Supreme

Court Rule 13(1), and said application was granted on

May 24,1965. The order provided that the time for docket

ing the appeal was extended until June 15, 1965. The juris

diction of the Supreme Court to review this decision by

direct appeal is conferred by Title 28 U. S. C. <§<§1253 and

2101(b). The following decisions sustain the jurisdiction

of the Supreme Court to review the judgment on direct

appeal to this court: Dombrowski v. Pfister, 380 U. S. 479;

Douglas v. Jeannette, 319 U. S. 157; Cameron v. Johnson,

—— u. S .------ , 33 U. S. L. W. 3395.

3

Questions Presented

1. Where appellants have alleged that a criminal statute

under which prosecutions are threatened is unconstitutional

on its face, in that it abridges freedom of speech, expression,

assembly and the right to petition for redress of grievances,

was the District Court in error in denying injunctive re

lief on the ground that appellants would sustain no ir

reparable injury by having their constitutional claims

adjudicated by the state courts?

2. Was the District Court in error in failing to hold

that section 26-904 of the Georgia Code, which makes it a

felony to circulate papers, pamphlets or circulars for the

purpose of inciting insurrection, riot, conspiracy, or re

sistance against the lawful authority of the state, is uncon

stitutional on its face?

3. Was the District Court in error in failing to hold that

section 26-904 of the Georgia Code was unconstitutional as

applied to the activities of the appellants, as established

by the evidence in this case?

Statutes Involved

Georgia Code Ann. Chapter 26-9.

26-901. Definition.- Insurrection shall consist in any

combined resistance to the lawful authority of the State,

with intent to the denial thereof, when the same is mani

fested or intended to be manifested by acts o f violence.

26-902. Attempt to incite insurrection.— Any attempt, by

persuasion or otherwise, to induce others to join in any

4

combined resistance to the lawful authority of the State

shall constitute an attempt to incite insurrection.

26-903. Punishment.—Any person convicted of the of

fense of insurrection, or an attempt to incite insurrection,

shall be punished with death; or, if the jury recommend to

mercy, confinement in the penitentiary for not less than

five nor more than 20 years.

26-904. Circulating insurrectionary papers.—-If any per

son shall bring, introduce, print, or circulate, or cause to

be introduced, circulated, or printed, or aid or assist, or

be in any manner instrumental in bringing, introducing,

circulating, or printing within this State any paper, pam

phlet, circular, or any writing, for the purpose of inciting

insurrection, riot, conspiracy, or resistance against the

lawful authority of the State, or against the lives of the

inhabitants thereof, or any part of them, he shall be pun

ished by confinement in the penitentiary for not less than

five nor longer than 20 years.

Statement

Appellants Samuel B. Wells and Donald Harris were

involved in civil rights activities in Albany, Georgia, in

1964. Samuel B. Wells is an official of the Southern Chris

tian Leadership Conference and Donald Harris is a mem

ber of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee,

organizations with headquarters in Atlanta, Georgia. These

organizations were acting together with the Albany Move

ment, a group composed of citizens of Albany, Georgia, in

a program designed to obtain equal, rights for Negro citi

zens of that city.

5

On Saturday, August 15, 1964, a Negro man, Wilmon

Jones, was shot and killed by a member of the Albany

Police Force at the Albany City dump (238 F. Supp. 780).

When appellant Wells heard of the shooting, he conducted

a brief inquiry and concluded that the killing was unjus

tified (R. 290). Together with appellant Harris and others,

he wrote and distributed two leaflets urging Negro citizens

to attend a meeting that evening at a local church in order

to take some action to protest the killing1 (R. 291-92).

1 Original copies of the leaflets were introduced as Plaintiffs

Exhibits A and B in the hearing below (R. 32-33). Their text

is as follows:

Leaflet number one:

“ A L B A N Y P O L I C E H A V E

M U R D E R E D A N O T H E R N E G R O !

THIS AFTERNOON ANOTHER ONE OF PRITCHETT’S

GUNMEN SLAUGHTERED A NEGRO MAN, WILBERT

JONES, OF FRONT STREET.

THIS BLACK MAN, LIKE THE LONG LIST OF OTHERS

KILLED BY PRITCHETT’S MURDEROUS MOB . . . IN

CLUDING ONE GUNNED DOWN TWO WEEKS AGO

IN C.M.E. . . . PLUS HARRIS, ASBURY, MILLER

AND OTHERS, WAS UNARMED AND IN NO W AY

BREAKING THE LAW WHEN HE WAS SHOTGUNNED

IN THE BACK-

TONIGHT IS THE TIME TO ACT

BLACK MAN * * AREN’T YOU TIRED OF GOING TO

FUNERALS ?

AREN’T YOU READY TO ACT?

BE AT EUREKA BAPTIST CHURCH * * IN HARLEM * *

ON JACKSON STREET AT 8 :00 TONIGHT

BE AT EUREKA BAPTIST CHURCH

TONIGHT IN HARLEM

JACKSON ST. NEXT TO GILES 8:00 p.m.”

(The Pritchett referred to is the Chief of Police in Albany.)

(footnote continued on following gage)

6

In response to the leaflets a crowd, variously estimated

as between 100 and 300 persons, gathered at the Eureka

Baptist Church in the Negro section of Albany, known as

Harlem (R. 313, 319). The church was selected as a meeting

place because it had been the scene of an earlier killing of

a Negro by the Albany Police (R. 316-17). Rev. Wells

spoke briefly at the meeting, telling the people that he

was going to go down to the police station to present a

petition protesting the killing of that afternoon and that

anyone who wished to might follow him for that purpose2

(R. 350-51).

Leaflet number two:

“ A L B A N Y P O L I C E H A V E

M U R D E R E D A N O T H E R N E G R O !

ALBANY POLICE HAVE KILLED

TOO MANY NEGROES . . .

. . . REMEMBER HARRIS?

. . . REMEMBER ASBURY?

. . . REMEMBER MILLER?

2 W E E K A G O A N E G R O W A S S H O T

I N T H E B A C K I N C M E . . .

I T I S T I M E T O A C T !

BE AT EUREKA BAPTIST CHURCH

TONIGHT IN HARLEM

JACKSON ST. NEXT TO GILES 8 :00 P.M.”

2 The petition taken to the police station was introduced as ap

pellants’ Exhibit “ C” (R. 34) and reads as follows:

To Chief of Police Lauri Pritchett:

Today another Negro was shot and killed brutally by an

Albany policeman.

The people of Albany have protested many times the bru

tality of the men who are supposed to enforce the law of

our city. The result has always been inaction and evasion,

all meant to excuse murder.

(footnote continued on following page)

7

Reverend Wells and Donald Harris began walking down

the street towards the police station, accompanied by ap

proximately twelve to sixteen persons (R. 307-09). The

District Court said that a “ considerable number” of the

audience went with appellants, and that the “ throng” was

“ sizeable” and was a “multitude.” 238 F. Supp. at 782.

However, there is no evidence to support these character

izations. Rev. Wells testified repeatedly that twelve, four

teen, or sixteen persons accompanied him (Plaintiffs’ Ex

hibit D, p. 75). The only evidence rebutting this was in

an affidavit by appellant Harris in which he said there were

thirty-five to forty persons. At all times, however, this

group was orderly (R. 6).

When they had proceeded approximately one block, and

were near the city’s bus station, a number of bottles and

other missiles were thrown by persons unknown (R. 307-08).

The testimony conflicted as to the direction from which

Black citizens and thoughtful whites of Albany are angered

by this latest incident, and we demand that further incidents

be prevented.

We of the Albany Movement and the Student Nonviolent

Coordinating Committee have faith and confidence in the phi

losophy of nonviolence as a means of social protest. We have

petitioned the city officials of Albany time and time again to

thoroughly investigate and fairly prosecute those responsible

for these acts, but our pleas for justice and eradication of

the brutal and savage tactics used by the Albany Police De

partment have gone unheard.

What little influence that the nonviolent leaders of this

community have is quickly ebbing. For the sake of Albany—

the total community— we demand a complete and thorough

investigation of this killing and prosecution of the officers

involved.

THE ALBANY MOVEMENT

SOUTHWEST GEORGIA STUDENT

NONVIOLENT COORDINATING COMMITTEE

8

these missiles came. Reverend Wells testified that they

came from a group of persons across the street from his

group and not associated with them (R. 308, 314-15). A

police officer at whom some of the missiles were thrown

testified that they seemed to have come from the direction

of Reverend Wells’ group, although he could not say for

certain that they came from any one of the sixteen persons

carrying the petition to the Chief of Police (Pis. Ex. F,

pp. 14-16). When a number of bottles broke at the feet of

Reverend Wells, he decided that it would be dangerous for

the group to continue walking. Therefore, he immediately

turned them around and the sixteen persons walked back

in the direction from which they had come, got into auto

mobiles, and went by different routes to the police station

(R. 309-10).

At the station they asked to see Chief of Police Laurie

Pritchett but were informed that he was out of town. They

did see the assistant chief and presented him the petition.

He asked who had written the petition and requested that

appellants Wells and Harris sign their name to it, which

they did (R. 299). The group then left the police sta

tion. Reverend Wells and Donald Harris went to their

homes and did not participate in any of the events in

Harlem later that evening (R. 311).

Between the time that appellants turned around at the

bus station and the time of their discussion with the as

sistant chief of police, disturbances had broken out in the

Harlem area. A large group of persons, mostly Negroes,

had assembled in the street and were throwing bricks and

bottles, breaking in windows of stores and looting some of

them (Pis. Ex. D, pp. 14-15). News of these events arrived

at the police station at the time appellants and their group

were there. The assistant chief of police asked them about

9

the events and inquired as to whether they were responsible

for them. Reverend Wells told him that they had nothing to

do with it (R. 341). The police were finally able to restore

order in the Harlem area about two hours later (Pis. Ex. I),

p. 16).

The District Court said that “ it is clear that the acts were

being committed by those marching with them [appellants]

or by sympathizers accompanying the marchers.” 238 F.

Supp. at 782. However, there is no evidence to support this

statement, either as to the disturbances near the bus sta

tion or the one later that evening. The officer at the station

testified that he was not sure from whom the missiles came

from (see supra). And an officer at the scene of the later

riot testified that he did not see Rev. Wells at the scene

(Pis. Ex. D, p. 64) and did not know where the rioters had

come from (Id., p. 67). Not only is the record devoid of

evidence that the disturbances were caused by appellants’

actions, but Rev. Wells’ testimony was to the effect that he

feared that the outbreak of violence was imminent because

of the people’s resentment over what they believed to be

unwarranted acts of police brutality, and he was trying to

give them an alternative, peaceful, and nonviolent means of

protesting to the authorities (R. 329, 344-45).

On the morning of August 18, 1964, appellant Wells was

arrested upon a warrant sworn out by the appellee, Laurie

Pritchett, Chief of Police of Albany, Georgia, charging him

with violations of section 26-902 of the Georgia Code (at

tempting to incite insurrection) and §26-904 (circulating

insurrectionary papers) (Pis. Ex. E ). Appellant Wells was

held in confinement for thirteen days without bail on the

charge under §26-902, which is an unbailable capital offense

under Georgia law (see Georgia Code §26-903). On Au

gust 24, 1965, a commitment hearing was held on the

10

charges against appellant Wells and he was bound over to

the grand jury on both charges. Subsequently, the charge

under §26-902 was “no billed” by the grand jury at the

request of Fred Hand, Jr., Solicitor General, on the ground

that the statute was unconstitutional. Rev. Wells was then

admitted to $2,500 bail on the charge under §26-904 (R.

198). An indictment against Wells for circulating in

surrectionary papers was handed down by the Dougherty

County grand jury on May 10, 1965. (See n. 6 infra.)

On August 17, 1964, a warrant was issued upon the affi

davit of appellee Pritchett for the arrest of appellant Don

ald Harris on a charge under §26-904 (Pis. Ex. L). To date,

Harris has not been arrested and during such time as he

may be present within the State of Georgia he is subject

to arrest.

On September 15, 1964, after having two petitions for

removal denied, inter alia, on the ground that no criminal

prosecution had been begun, appellants filed their complaint

in this case seeking to enjoin prosecutions under §§26-902

and 26-904 on the grounds that they were unconstitutional

on their face and as applied to the activities of the appel

lants (R. 25). The defendants remaining after changes

in the parties during the course of the hearing were Fred

Hand, Jr., Solicitor General of the Albany Judicial Cir

cuit, for whom has been substituted Robert Reynolds, the

present Solicitor General; G. S. Thornton, Justice of the

Peace in the county who issued the warrants involved and

who has subsequently died (238 F. Supp. 779 at 783);

Laurie Pritchett, Chief of Police of the City of Albany,

under whose direction the investigation leading up to the

issuance of the warrants was conducted and who swore out

the warrants; and Billy L. Manley, Captain of Detectives

11

in the Albany Police Department, who is responsible for

the conduct of investigations including the one leading up

to the warrants and arrests herein.

A three-judge court was convened and a hearing, which

by stipulation was on a motion for permanent injunction

(R. 162), was held. The court denied injunctive relief

on the grounds that:

(1) All parties agreed that no prosecution could be had

under §26-902 because of its unconstltutionality and that

charges under it had been dismissed and assurances made

that no further prosecutions would be made;

(2) There had been a failure by appellants to show that

the prosecutions were instigated for the purpose of inter

fering with the constitutional rights of appellants; and

(3) That even if §26-904, the only section under which

prosecutions were still pending, were unconstitutional either

on its face or as applied, the court would refrain from inter

fering with the state prosecutions since no irreparable in

jury had been shown. The denial of injunctive relief was

conditioned on a reduction of the bail required to $1,000,

which reduction has been made.

A timely notice of appeal from the decision below was

filed and a subsequent motion to reconsider the court’s

judgment in light of this court’s opinion in Dombrowski v.

Pfister, 380 TJ. S. 479, was denied (Supplemental Record,

p. 9).

12

The Questions Are Substantial

The initial question involved in this appeal is substan

tially the same as that raised and decided in the case of

Dombrowski v. Pfister, 380 U. S. 479, decided by this Court

on April 26, 1965. In Dombrowski this Court held that

it was error for a federal three-judge court to refrain from

deciding a claim that a state statute was unconstitutional

on its face as abridging freedom of speech. Here, the

District Court, although it held a hearing, denied injunctive

relief for reasons similar to those advanced by the lower

court in Dombrowski in dismissing the complaint. The

second question involved, whether §26-904 of the Georgia

Code Annotated is unconstitutional on its face and as ap

plied, is governed largely by this Court’s determination in

Herndon v. Lowry, 301IJ. S. 242, that a companion statute,

§26-902, was unconstitutional.

1. The complaint in this case alleged, inter alia, that:

Sections 26-902 and 26-904 of the Georgia Code are

unconstitutional both on their face and as applied to

plaintiffs. Specifically, these statutes and the actions

of the defendants in enforcing and executing them

violate the First, Fifth, Eighth and Fourteenth Amend

ments to the Constitution of the United States in that:

# # # # *

(b) They abridge plaintiffs’ freedom of speech, press

and assembly, and their rights to petition lawful au

thority for a redress of grievance; . . . (R. 25).

In their memoranda of law, plaintiffs argued that §26-904

was overly broad and vague. Appropriate relief, including

13

an injunction against the threatened prosecutions of plain

tiffs under these statutes, was requested.

Despite these allegations, however, the court below, in

refusing the relief requested, declined to express any view

concerning the constitutionality of §26-904 and stated:

Even if it should ultimately be determined that Georgia

Code §26-904 as applied to these Plaintiffs is uncon

stitutional, the Plaintiffs are not without adequate rem

edy and protection short of the issuance of this Court’s

injunction. Federal courts of equity have traditionally

been loathe to restrain criminal proceedings in the

state courts even on constitutional grounds and all of

the constitutional issues can be decided in the first

instance as a matter of course by the state courts.

(238 F. Supp. 779 at 785.)

The court went on to say that the threat of prosecution

under a statute alleged to be unconstitutional on its face

because it abridged freedom of speech, assembly, and the

right to petition for redress of grievance did not consti

tute irreparable injury sufficient to warrant injunctive

relief. Therefore, the case was an appropriate one to

withhold relief because an indictment could be narrowly

drawn and the Georgia courts could construe the statute

so that it would be constitutional.

This conclusion is in direct conflict with this Court’s

decision in Dombrowski. There, as here, persons threatened

with prosecution under a state criminal statute attacked it

on the ground that it was unconstitutional as an abridg

ment of First Amendment rights. This Court held:

The District Court also erred in holding that it

should abstain pending authoritative interpretation

14

of the statutes in the state courts, which might hold

that they did not apply to SCEF, or that they were

unconstitutional as applied to SCEF. We hold the

abstention doctrine is inappropriate for cases such as

the present one where, unlike Douglas v. City of Jean-

nette, statutes are justifiably attacked on their face

as abridging free expression, or as applied for the

purpose of discouraging protected activities.

# # * * *

Second, appellants have challenged the statutes as

overly broad and vague regulations of expression. We

have already seen that where, as here, prosecutions are

actually threatened, this challenge, if not clearly friv

olous, will establish the threat of irreparable injury

required by traditional doctrines of equity. We believe

that in this case the same reasons preclude denial of

equitable relief pending an acceptable narrowing con

struction. 380 U. S . ------ , 14 L. Ed. 2d 22, 30-31.

Under this holding, therefore, the District Court was

obliged to decide the substantive question raised, and its

decision must be reversed or vacated and the cause re

manded on this ground alone. Cameron v. Johnson, ----- -

U. S. - — , 33 U. S. L. Week 3395.3

3 In Cameron, the Court in a per curiam order of five justices

remanded for reconsideration in light of Dombrowski. Justices

Black, Harlan, and Stewart would have affirmed, while Justice

White would have set the case for argument. One of the main

bases for the dissents was that the justices felt that the statute

involved in Cameron was clearly constitutional. This case, how

ever, presents a statute about which there are undeniable questions

of constitutionality because of Herndon v. Lowry, 301 U. S. 242.

15

2. Appellants also contend that this court should find that

§26-904 is unconstitutional on its face as abridging freedom

of speech, assembly and petition in violation of the First

and Fourteenth Amendments and that it is unduly vague,

uncertain and broad. This contention raises the question as

to the extent this case is controlled by this Court’s decision

in Herndon v. Lowry, 301 U. S. 242. That case held that

the precursor of §26-902 of the Georgia Code was uncon

stitutional as violating the First and Fourteenth Amend

ments.

Both sections 26-902 and 26-904 are part of Chapter 26-9

of the Georgia Code which deals with insurrection and

attempts to incite insurrection. Section 26-901 defines in

surrection to ‘ 'consist in any combined resistance to the

lawful authority of the State, with intent to the denial

thereof, when the same is manifested or intended to be

manifested by acts of violence.” Section 26-902 defines an

attempt to incite insurrection as an attempt “ to induce

others to join in any combined resistance to the lawful

authority of the State.” Section 26-903 provides that insur

rection and the attempt to incite insurrection shall be a

capital offense, and finally, section 26-904 makes it a crime

to “bring, introduce, print, or circulate,” or cause or aid

or assist in introducing, circulating, or printing any writing

for “ the purpose of inciting insurrection, riot, conspiracy,

or resistance against the lawful authority of the State.” 4

4 At the time of Herndon, these provisions appeared as sections

55 to 58 of the Georgia Penal Code. The full texts of sections 26-902

and 26-904 are as follows:

26-902. Attempt to incite insurrection.— Any attempt, by

persuasion or otherwise, to induce others to join in any com

bined resistance to the lawful authority of the State shall con

stitute an attempt to incite insurrection.

(footnote continued on following page)

16

In Herndon v. Lowry the Court found that the words

“ to incite insurrection,” found in §26-902 and defined there

and in §26-901, were overly broad and vague, giving no

warning of the conduct proscribed. Therefore, the section

was unconstitutional because it seriously impinged on legiti

mate free speech activities.

In the present ease, the court and the parties below recog

nized that §26-902 was clearly unconstitutional because of

the decision in Herndon.5 Thus it necessarily recognized

that that part of §26-904 which made it a crime to circulate

any writing for the purpose of inciting insurrection was

also unconstitutional. Despite this, the court indicated that

§26-904 could be upheld because the part of the section mak

ing it a crime to circulate papers for the purpose of incit

ing riot, conspiracy or resistance against the lawful au

thority of the state could be construed to be independent of

the insurection provision and thus could be found to be

constitutional. Although the warrants under which Rever

end Wells was arrested and Donald Harris was threatened

with arrest were for “ circulating insurrectionary papers”

the court said that the prosecutor still might prepare an

26-904. Circulating insurrectionary papers.— If any person

shall bring, introduce, print, or circulate, or cause to be intro

duced, circulated, or printed, or aid or assist, or to be in any

manner instrumental in bringing, introducing, circulating, or

printing within this State any paper, pamphlet, circular, or

any -writing, for the purpose of inciting insurrection, riot, con

spiracy, or resistance against the lawful authority of the State,

or against the lives of the inhabitants thereof, or any part of

them, he shall be punished by confinement in the penitentiary

for not less than five nor longer than 20 years.

5 Another district court reached the same conclusion and enjoined

criminal prosecutions under §26-902 in Aelony v. Pace, ------ F.

Supp. -------, 8 Race Rel. L. Rep. 1355 (M. D. Q-a., Nos. 530, 531,

1963).

17

indictment which charged only incitement to riot, and such

an indictment and a conviction under it -would be valid.

238 F. Supp. at 785.6

6 The court below, by discussing the statute in terms of such hypo

thetical occurrences, was in conflict with the decision in Domirow-

ski. There, this Court said:

In considering whether injunctive relief should be granted

a federal district court should consider the statute as of the

time its jurisdiction is invoked, rather than some hypothetical

future date. 380 U. S. — —, 14 L. Ed. 2d 22, 31.

During the time this jurisdictional statement was being prepared

by counsel for appellants, it came to their attention that on May

10, 1965, the following indictment was handed down solely against

appellant Wells by the Dougherty County grand jury, charging

him under §26-904:

The grand jurors, selected, chosen and sworn for the County

of Dougherty, to w it: [names of grand jurors omitted] In the

name and on behalf of the citizens of Georgia, charge and ac

cuse S. B. Wells with the offense of circulating insurrection

papers for that the said accused, in the county aforesaid, on

the 15th day of August, in the year of our Lord, Nineteen

Hundred Sixty-Four, with force and arms, and unlawfully, did

then and there introduce, bring, print and circulate, and did

cause the same to be brought, introduced, printed and circu

lated, and did assist in bringing, introducing, printing and

circulating, within the county and State aforesaid certain

papers, pamphlets, cards, sheets, circulars, magazines, books,

and writing for the purpose of inciting insurrection, riot, con

spiracy, and combined resistance to and against the lawful

authority of the State of Georgia and against the lives of the

inhabitants thereof, with intent to incite insurrection and to

abolish, defeat, and overthrow by acts of violence the lawful

authority of the State of Georgia, said insurrectionary litera

ture being as follows, to w it:

Attached are exhibits “A ” and “B” all contrary to the laws

of said State, the good order, peace and dignity thereof.

Robert W. Reynolds

Solicitor General

Exhibits “A ” and “B” are copies of the leaflets introduced in this

case as plaintiffs’ exhibits “A ” and “B” and reproduced in n. 1,

18

In view of the actual basis of its decision, the lower

court’s discussion of the statute was dicta. However, it

indicates clearly the conclusion that would be reached were

this case merely remanded for reconsideration in light of

Dombrowski. This is particularly true since the lower court

has already denied a request by appellants to reconsider

its opinion because of Dombrowski and to decide the con

stitutional issue. Therefore, this court should reach and

decide the questions raised; first, whether the entire statute

is unconstitutionally vague on its face; and second, assum

ing that the statute without the words “ inciting insurrec

tion” would be valid, whether those words can constitu

tionally be severed from the rest of the statute and the re

mainder upheld.

A. Appellants argue that §26-904 in its entirety is un

constitutional for the same reasons §26-902 was so found

in Herndon v. Lowry. There, the court said:

The Act does not prohibit incitement to violent inter

ference wtih any given activity or operation of the

state. By force of it, as construed, the judge and jury

trying an alleged offender cannot appraise the circum

stances and characterization of the defendant’s utter

supra. The name of appellee Laurie Pritchett, as well as that of

appellee Reynolds appears on the indictment.

A motion for a stay of any prosecution under the indictment,

pending final disposition of this ease, was filed in the court below

on June 14, 1985, with a certified copy of the indictment attached.

Notice has been given to the court below to make the motion part

of the record in the case in this court.

The handing down of the indictment by the grand jury is not a

bar to the federal courts granting relief since it was done after the

filing of the complaint herein. Dombrowski v. Pfister, 380 U. S. 479,

14 L. Ed. 2d 22, 27, n. 2. To date, there is no indictment against

appellant Harris.

19

ances or activities as begetting a clear and present

danger of forcible obstruction of a particular state

function. Nor is any specified conduct or utterance of

the accused made an offense.

The statute, as construed and applied, amounts merely

to a dragnet which may enmesh anyone who agitates

for a change of government if a jury can be persuaded

that he ought to have foreseen his words would have

some effect in the future conduct of others. No reason

ably ascertainable standard of guilt is prescribed. So

vague and indeterminate are the boundaries thus set

to the freedom of speech and assembly that the law

necessarily violates the guarantees of liberty embodied

in the Fourteenth Amendment. 301 U. S. 261-264.

This criticism, which clearly applies to the words “ inciting

insurrection” in §26-904, applies with equal force to the

rest of the statute. The statute cannot reasonably be

construed to reach riot or conspiracy per se, as contended

by the lower court. Bather, what was intended was to pun

ish “ riot, conspiracy or resistance against the lawful au

thority of the state,'” with the final clause modifying “ riot”

and “ conspiracy” as well as “ resistance.”

Therefore, the basic element involved in all crimes pun

ishable under the section, as well as in all crimes punishable

under chapter 26-9 as a whole, is the incitement of violent

resistance against the lawful authority of the state. And,

as the court held in Herndon, the statute is therefore im

permissibly vague since it is not directed toward any

specific state function or activity. It leaves it to the specu

lation of persons engaged in free expression, and of prose

20

cutors and juries, what kind of speech is intended to be

reached.

It is the uncertainty as to scope and the resulting in

hibitory effect on free speech that renders the statute

unconstitutional. As this Court has stated, citing Herndon

v. Lowry:

It is settled that a statute so vague and indefinite,

in form and as interpreted, as to permit within the

scope of its language the punishment of incidents

clearly within the protection of the guarantee of free

speech is void, on its face, as contrary to the Four

teenth Amendment . . . A failure of a statute limiting

freedom of expression to give fair notice of what acts

will be punished and such a statute’s inclusion of pro

hibitions against expressions, protected by the prin

ciples of the First Amendment, violates an accused’s

rights under procedural due process and freedom of

speech or press. Winters v. New York, 333 U. S. 507,

509-10.

Section 26-904 falls clearly under this rule, since in this

case appellants are threatened with prosecution under it,

although they have been guilty of nothing more than dis

tributing leaflets calling a meeting to protest what they

believed to be police brutality, and subsequently peacefully

presenting a petition calling for corrective action to the

public authorities.

In addition, because the statute encompasses constitu

tionally protected speech, it can be challenged by appellants

even if it were assumed their acts might have been validly

proscribed by a statute more narrowly drawn. Dombrowski

21

v. Pfister, 380 IT. S. 479, 14 L. Ed. 2d 22, 28; Thornhill v.

Alabama, 310 II. S. 88, 97-98.

B. Appellants further contend that §26-904 cannot be

construed so as to sever its unconstitutional and constitu

tional provisions. It should be noted that the District Court

advanced the argument that the unconstitutional part of

§26-904 might be severed from constitutional ones on the

assumption that an indictment might be drawn up for dis

tributing writings for the purpose of inciting riot. As noted

in n. 6, supra, the state subsequently indicted appellant

Wells for distributing papers for the purpose of inciting

an insurrection. This demonstrates that Georgia does not

consider the statute to be severable, but rather to be a

unitary statute directed, as are the other sections of Chap

ter 26-9, against “ insurrection.” Thus, §26-904 should be

held unconstitutional as a whole for the reasons advanced

above.

However, assuming as did the court below, that an indict

ment for inciting to riot might still be handed down against

appellant Harris, appellants maintain that the unconstitu

tional incitement to insurrection language cannot be severed

from the remainder, and the entire section must fall. To

allow severability would result in a construction which

would itself render the section unconstitutionally vague

and incapable of giving sufficient warning of the conduct

proscribed. Cf. United States v. Raines, 362 U. S. 17, 22-23.

It is established law that there is. a presumption against

the severability of a statute, and that the legislature in

tended that a statute operate in its. entirety, unless it has

indicated otherwise by a severability clause. Such a clause

is not present in §26-904. Williams v. Standard Oil Co., 278

22

IT. S. 235, 241-242. The presumption obtains even where, by

severing one provision of a criminal statute, the rest of it

might be upheld, since penal provisions must be construed

strictly.7 See Butts v. Merchants & M. Transp. Co., 230

U. S. 126. Cf. Williams v. Standard Oil Co., supra.

As shown supra, §26-904 is part of a chapter whose pur

pose is to deal specifically with insurrection and attempts

to incite insurrection. Therefore, the section itself, on its

face and from its context, demonstrates a clear legislative

intent to deal in all its parts with First Amendment activi

ties which it was believed would promote insurrectionary

acts. Similarly, it is clear that the statute was not intended

to reach riot or conspiracy per se. Rather, it seeks to punish

the incitement of riots “ against the lawful authority of the

state,” i.e., those that are part of an insurrection.8 * 10

The conclusion that 26-904 is in its entirety inextricably

bound up with the offense of insurrection is supported by

7 The presumption of nonseverability is particularly strong in the

ease of a statute which infringes in part on the rights of free ex

pression. It has been held by this court that where part of a statute

violates First Amendment rights and its sections are so interrelated

as to be substantially one, they should be judged on their face as a

unit. See Jones v. Opelika, 316 U. S. 584, 611, 615, n. 5 (dissenting

opinion), adopted per curiam on rehearing, 319 U. S. 103; Note,

61 Harvard Law Review 1208 n. 3.

8 An entirely separate section of the Georgia Code reaches riot

per se. Georgia Code Annotated §26-5320 states: “Riot—Any two

or more persons who shall do an unlawful act of violence or any

other act in a violent and tumultuous manner, shall be guilty of

a riot and punished as for a misdemeanor.” Prosecutions have

been brought for incitement to riot under this section whereas none

have been brought under 26-904. See Loomis v. State, 78 Ga. App.

336, 346, 51 S. B. 2d 33, 43 (1948); Statham v. State, 84 Ga. 17,

10 S. E. 493 (1889).

23

the construction of the statute (then section 58 of the

Georgia Penal Code) by the Supreme Court of Georgia in

the eases of Dalton v. State, 176 Ga. 645, 169 S. E. 198

(1933), and Carr v. State, 176 Ga. 55, 166 S. E. 827 (1932).

In the latter case the court adopted as part of its opinion

the opinion in Gitlow v. New York, 268 U. S. 652, and quoted

in part:

“ And a state may penalize utterances which openly

advocate the overthrow of the representative and con

stitutional form of government of the United States

and the several States, by violence or other unlawful

means. . . . By enacting the present statute the State

has determined, through its legislative body, that utter

ances advocating the overthrow of organized govern

ment by force, violence and unlawful means, are so

inimical to the general welfare and involve such danger

of substantive evil that they may be penalized in the

exercise of its police power.” Carr v. State, 166 S. E.

827, 829.

Thus, the Supreme Court of Georgia has held that §26-

904 as a whole is part of the same statutory scheme of regu

lation as that struck down in Herndon v. Lowry, and it must

fall along with §26-902.® 9

9 The Georgia Court’s interpretation precludes any construction

by a federal court that severs the provision of the section, since

it is a settled rule of law that a federal court cannot disregard

the interpretation of a state statute by a state court, even if it

might thereby save the statute. Therefore, cases such as Chaplinsky

v. State of New Hampshire, 315 U. S. 568, are not in point. There

the state court had said that the provisions of the state statute

were severable.

24

3. The final question presented by this appeal is whether

the District Court erred in not holding that §26-904 was ap

plied for the purpose of discouraging constitutionally pro

tected rights. Appellants alleged in their complaint:

Defendants are well aware that §26-902 has been de

termined unconstitutional, by the United States Su

preme Court and this Court [see Herndon v. Lowry,

301 U. S. 242 (1937); Harris, et al. v. Pace, et a l , ------ -

F. Supp.------ (1963)] but, nevertheless have arrested

and threatened the arrest of the plaintiffs Harris and

Wells. This threatened attempt to enforce and execute

this statute, as well as §26-904 against plaintiffs, is . . .

part of an overt scheme and plan by defendants, and

others, acting in concert, and in violation of 42 U. S. C.

§§1971, 1981 and 1983 to oppress, threaten and intimi

date citizens of the United States, including plaintiffs,

who are engaged in the exercise of rights, privileges

and immunities guaranteed by the Constitution and

laws of the United States (R. 26).

The lower court decided, after considering the constitu

tionality of the application of §§26-902 and 26-904, “ [I]t is

apparent that this court’s injunction to restrain these de

fendants, or any of them, from the further use of §26-902 is

neither necessary nor needed.” 238 F. Supp. at p. 785.

Further, that “ [e]ven if it should ultimately be determined

that Georgia Code §26-904 as applied to these plaintiffs is

unconstitutional, the plaintiffs are not without adequate

remedy and protection short of the issuance of this Court’s

injunction.” [Id.] Appellants were thus required to submit

their federal constitutional claims to state court determi

nation.

25

The lower court’s opinion, in refusing to enjoin further

enforcement of §26-904, as unconstitutionally applied,

squarely rejects this court’s decision in Dombrowshi v.

Pfister, supra. There, it was decided that where state stat

utes were unconstitutionally applied for the purpose of

discouraging protected conduct, federal injunctive relief

against further state prosecution was appropriate. A con

trary view, as this court pointed out in Dombrowshi, would

subject appellants to continued bad faith prosecution, even

after substantial federal rights had been invaded.

Appellants’ contentions, that both §§26-902 and 26-904

were being applied in bad faith, and to discourage engage

ment in protected activity, were wholly supported by the

record below.

First, the record clearly shows that the handbill distribu

tion by appellants Wells and Hand was not to urge “ riot

ing” or “ insurrection,” as charged in the warrant,10 but, as

even the lower court states, merely to urge a meeting at

Eureka Baptist Church (283 F. Supp. p. 782). No handbills

were distributed during the meeting (R. 323), nor even

referred to (R. 323), and only the petition, later presented

to Assistant Chief Summerford, was read by Wells during

Ms speech (R. 350). Wells at no time advocated destrue-

10 The state arrest warrant charged Wells with both offenses

(26-902 and 26-904),in essentially the same language:

26-902 Ga. Code. Attempt to incite insurrection; and

26-904 Ga. Code, Circulating insurrectionary papers.

Subject did circulate papers attempting to incite insurrec

tion Ga. Code 26-902 also attempting to incite insurrection

at a meeting at Eureka Baptist Church on South Jackson

Street 8/15/64. Subject did incite enough to the extent riot

ing in Harlem, breaking windows out of several store fronts

and causing considerable damage by Rock and Bottle:

Throwing (Pis. Ex. E).

26

tion of property, and his uncontradicted testimony was that

he advocated only the petition’s presentation as an appro

priate form of protest:

I would rather for them to go down and peacefully pro

test than to do anything otherwise. That’s what causes

other things, is because you don’t have any way to let

out your expressions; . . . (E. 329).

Nor, during the procession from the church to the police

station, did Wells or Harris advocate or commit any vio

lence (see findings 283 F. Supp. at p. 782). And, although

the lower court found that violence was committed by those

marching with appellants, or sympathizers, there was no

evidence in the record to support that conclusion. (See

Statement, supra, pp. 7-9.)

Second, with full knowledge of these facts, gathered from

“ reports” received from officers (R. 220), Chief Pritchett

caused the arrest of appellants Wells and Harris, and Nick

Louketas under §§26-902 and 26-904, and although there

were numerous arrests on charges of looting, burglary and

“ for investigation,” there were no other arrests under

either of these statutes. In fact, only these three, who made

the actual presentation of the petition at the police station,

were charged under'§§26-902 and 26-904 (Wells and Harris

had signed the petition at the insistence of the assistant

chief of police).

Wells and Louketas served 13 and 5 days respectively,

awaiting state prosecution under 26-902 which was known

by the Chief of Police to be invalid.11 And, although the

11 In the commitment hearing of appellant Wells, conducted

before defendant G. S. Thornton, Chief Pritchett was asked by

27

lower court found that evidence that the arrests were made

with “ some information” of the invalidity of one of the

statutes (26-902) it concluded that this did not establish

that appellant’s constitutional rights had been deprived

with “ deliberate intent.” But, the initial prosecution under

both statutes, combined with Wells’ continued incarceration

after Chief Pritchett had been placed on notice of the stat

ute’s invalidity, were obviously designed to discourage

further presentations of the kind Wells had made.

Thus, on the record, remission of appellants to state trial

would subject them to the same continued harassment pros

ecution which this court condemned in Dombrowski v.

Pfister, supra; and, Cameron v. Johnson, —— U. S. ------ ,

33 U. S. L. Week 3395.

one of plaintiffs’ counsel whether he wasn’t aware that the statute

(26-902), under which the warrant issued, had been declared

unconstitutional:

Q. Now the fact that you have read that the holding of

the Federal Tribunal has declared that this law is unconsti

tutional, would that make any difference with reference with

reference [sic] to your deciding to withdraw the warrant?

A. With Judge Tuttle—did he sign it—Judge Tuttle ruling

it was unconstitutional. I suppose he did, I didn’t see him

sign it,—it wouldn’t make any difference to me.

Q. Even if this was true, it would make no difference to

you? A. As I say, attorney, I don’t know whether it is

unconstitutional or not when the Courts rule on it.

Q. But you didn’t answer my question, Chief, would it

make any difference to you? A. It wouldn’t make any dif

ference to me (Pis. Ex. D, p. 8).

28

CONCLUSION

It is respectfully prayed that the Court should review

the judgment o f the District Court and enter a judg

ment reversing the decision below.

Respectfully submitted,

Jack Greenberg

James M. Nabrit, III

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

C. B. K ing

221 South Jackson Street

Albany, Georgia

Attorneys for Appellants

Charles H. J ones, J r.

C ttart.e s Stephen R alston

Of Counsel

A P P E N D I X

la

APPENDIX

Opinion of the Court Below

UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

Middle District Georgia, Albany Division

Feb. 24, 1965

Civ. A. No. 821

Samuel B. W ells, D onald H arris et al.,

Plaintiffs,

— v .—

F red H and, Jr., individually and as Solicitor General,

Albany Judicial Circuit, et al.,

Defendants.

B e f o r e :

B ell, Circuit Judge,

and B ootle and E lliott, District Judges.

E lliott, District Judge:

In attempting to make an arrest of a Negro man on

August 15, 1964 a member of the City Police force of the

City of Albany, Georgia fired a shot which resulted in the

death of the man sought to be arrested. Neither the Plain

tiff Wells nor the Plaintiff Harris witnessed this incident,

but, based on “ reports” which they heard concerning the

matter, they concluded that the officer was guilty of

2a

“murder” and they decided that they would do something

about it. During that afternoon they prepared two hand

bills and distributed them widely in the Negro community

in the City of Albany. The first handbill was as follows:

“ALBANY POLICE HAVE MURDERED

ANOTHER NEGRO!

THIS AFTERNOON ANOTHER ONE OF PRITCH

E T T ’S GUNMEN SLAUGHTERED A NEGRO MAN,

W ILBERT JONES, OF FRONT STREET.

THIS BLACK MAN, LIKE THE LONG LIST OF

OTHERS KILLED BY PRITCH ETT’S MURDER

OUS MOB . . . INCLUDING ONE GUNNED DOWN

TWO W EEKS AGO IN C.M.E____ PLUS HARRIS,

ASBURY, MILLER AND OTHERS, W AS UN

ARMED AND IN NO W AY BREAKING THE LAW

WHEN HE WAS SHOTGUNNEDIN THE BACK.

TONIGHT IS THE TIME TO ACT

BLACK MAN * * AREN’T YOU TIRED OF

GOING TO FUNERALS ?

AREN’T YOU READY TO ACT!

BE AT EUREKA BAPTIST CHURCH * * IN

HARLEM * * ON JACKSON STREET

AT 8:00 TONIGHT

BE AT EUREKA BAPTIST CHURCH

TONIGHT IN HARLEM

JACKSON ST. NEXT TO GILES 8:00 p.m.”

(The Pritchett referred to is the Chief of Police of

Albany.)

3a

The other handbill was in this fashion:

“ ALBANY POLICE HAVE MURDERED

ANOTHER NEGRO!

ALBANY POLICE HAVE KILLED TOO MANY

NEGROES . . .

. . . REMEMBER HARRIS'?

. . . REMEMBER ASBURY?

. . . REMEMBER M ILLER!

2 W EEKS AGO A NEGRO W AS SHOT IN THE

BACK IN CME . . .

IT IS TIME TO ACT!

BE AT EUREKA BAPTIST CHURCH

TONIGHT IN HARLEM

JACKSON ST. NEXT TO GILES 8:00 P.M.”

In response to the urging of the handbills a crowd gath

ered at the street corner near the Baptist Church mentioned

at the appointed hour of 8 :00. This was on Saturday night

near the center of what is known as “ Harlem” and in an

area where there is normally considerable pedestrian and

automobile traffic and at a time when a street corner orator

would be likely to attract attention. The Plaintiff Wells

rented a microphone and loud speaker and addressed the

crowd assembled, which he estimated to be between 200 and

300 persons. The gist of his speech was to remind the

crowd of the details of what he considered to be police

atrocities against members of the Negro race and his re

marks were in the same general tone as suggested by the

handbills previously distributed. He urged the crowd to do

4a

something about it and he stated that he had prepared a

petition which he was going to present to the Chief of

Police at the City Hall and that he was going to march

from the meeting place down to the City Hall for that pur

pose, and he invited the crowd to go with him. He then set

out on foot to march to the City Hall and a considerable

number of his audience, being thus agitated and urged, pro

ceeded to go with him. From the evidence it is difficult to

determine with any degree of certainty how many there

were in this throng, but it is clear that the number was

sizeable. The Plaintiff Wells led the march and the Plain

tiff Harris brought up the rear. Being thus shepherded the

multitude set out for the City Hall, which was some blocks

away. As might be expected, the march was attended by

considerable commotion, and before reaching the an

nounced destination bottles, stones and bricks were being

hurled, plate glass windows in business establishments

were being knocked out, citizens were being threatened and

the peace and security of the entire area through which the

procession was passing was being disrupted. There is no

evidence that the Plaintiffs Wells and Harris committed

any of these acts of violence but it is clear that the acts

were being committed by those marching with them or by

sympathizers accompanying the marchers. After having

proceeded some distance on the way the Plaintiff Wells

and the Plaintiff Harris decided for some reason to go

back to the original meeting place and make the trip by

automobile and this they did with a small group. After they

withdrew, acts of vandalism and looting were widespread

in the area into which the crowd had been led and these

acts were directed toward business establishments either

owned or operated by white persons. Principal victims

5a

were a jewelry store, a liquor store, a loan company, a drug

store and a bus station. Physical damages amounted to

several thousand dollars. It was not until some two and

a half hours later that a semblance of order was restored

in that section of the community. A number of arrests were

made for burglary, looting, assaults and related offenses.

In the meantime Plaintiffs Wells and Harris, together with

a small group, had gone to the City Hall where the Police

Headquarters are located to present their written com

plaint to the Chief of Police, Mr. Pritchett. They learned

that the Chief was out of town and they presented their

complaint to the Assistant Chief, Mr. Summerford. He

received the complaint and stated to the group that he

would hand it to Chief Pritchett upon his return to the

city. It was during the time when the Plaintiffs Wells and

Harris were in conference with the Assistant Chief that the

reports began coming in to headquarters concerning the

damage and looting in the area from whence the Plaintiffs

had recently come and the Assistant Chief inquired of Wells

and Harris whether their group was responsible for that

activity. The Plaintiffs disavowed any responsibility in the

circumstances.

Based upon subsequent investigation the Chief of Police,

Mr. Pritchett, made affidavit before G. S. Thornton, Justice

of the Peace, that a warrant might issue for the arrest of

the Plaintiff Wells for violation of § 26-902 of the Georgia

Code, attempting to incite insurrection, and also for viola

tion of § 26-904 of the Georgia Code, charging him with

circulating insurrectionary papers.1 By virtue of the war

1 “ § 26-902. Attempt to incite insurrection.—Any attempt, by

persuasion or otherwise, to induce others to join in any combined

resistance to the lawful authority of the State shall constitute an

attempt to incite insurrection.”

“ § 26-904. Circulating insurrectionary papers.—If any person

shall bring, introduce, print, or circulate, or cause to be introduced,

6a

rants so issued the Plaintiff Wells was taken into custody

and he was detained for thirteen days without bond, the

offense described in § 26-902 being a non-bailable offense.

Upon investigation, the Solicitor General, Mr. Hand,

who would be the state prosecutor of the offenses, con

cluded that the Plaintiff Wells could not be prosecuted

under §26-902 and he directed that the Plaintiff Wells be

released from any charge under that section, whereupon

the Plaintiff Wells was released on $2,500.00 bond with

respect to the charge pending against him under the provi

sions of § 26-904. No charge has ever been made against

the Plaintiff Harris for violating § 26-902. He has been

charged by warrant with violating § 26-904 and bond has

been set at $2,500.00. The Plaintiff Harris has never been

taken into custody under this warrant, so the Plaintiff

Harris has never been jailed and the Plaintiff Wells has not

been in custody since August, 1964. As heretofore indi

cated, all of the matters related took place in August, 1964.

On September 15, 1964 the Plaintiffs filed the complaint

which is now before us under the provisions of Title 42

U. S. C. §§1971, 1981 and 1983, by which they sought to

have a three-judge district court convened pursuant to

Title 28 U. S. C. §§ 2281 and 2284. By subsequent amend

ment Plaintiffs also invoked the provisions of Title 28

U. S. C. §1343(3) and (4).

circulated, or printed, or aid or assist, or be in any manner in

strumental in bringing, introducing, circulating, or printing within

this State any paper, pamphlet, circular, or any writing, for the

purpose of inciting insurrection, riot, conspiracy, or resistance

against the lawful authority of the State, or against the lives of

the inhabitants thereof, or any part of them, he shall be punished

by confinement in the penitentiary for not less than five nor longer

than 20 years.”

7a

This complaint as originally filed contained a number of

allegations for which there is no support in the record and

joined a number of defendants who have since been stricken

as parties. Originally the Mayor and all of the members of

the City Council of the City of Albany were named as

parties defendant. The City of Albany itself as a body

corporate was also named a party defendant. The Sheriff

of Dougherty County was also named. No evidence of any

nature connected these defendants with the matter under

consideration and the City of Albany and the Mayor and

the several members of the City Council were stricken as

parties Defendant on motion of the Defendants and the

Sheriff of Dougherty County was stricken as a party De

fendant on motion of the Plaintiffs. One additional Defen

dant, Billy L. Manly, Captain of Detectives, was added by

amendment to the original complaint. The Defendants re

maining in the case are Fred Hand, Jr., Solicitor General

of the Albany Judicial Circuit,2 G. S. Thornton, Justice of

the Peace in Dougherty County,3 Laurie Pritchett, Chief

of Police of the City of Albany and Billy L. Manly, Captain

of Detectives in the Albany Police Department. As orig

inally filed, the complaint prayed for an injunction to issue

restraining the Defendants “ from denying plaintiffs, or

members of the class on whose behalf plaintiffs sue, the

right to participate in the solicitation, promotion, and en

couragement of others to register and vote” . It also asks

this Court’s injunction to restrain the Defendants “ from

denying plaintiffs, and the members of their class the right

2 We judicially notice the fact that Mr. Hand no longer holds

office as Solicitor General of the Albany Judicial Circuit.

3 We judicially notice the fact that Judge Thornton is now

deceased.

8a

to conduct peaceful public assemblies, or meetings to pro

test against state-enforced segregation, or any unlawful,

unwarranted or arbitrary abuses of state power” .

Upon the hearing on this matter no evidence whatever

was presented showing any denial on the part of these

Defendants, or anyone else for that matter, of the right

of the Plaintiffs to participate in political activities, includ

ing the right to register and vote, and at no time during

the hearing was any evidence offered or any suggestion

made that there was any issue of segregation of the races

involved here. This leads us to conclude that these allega

tions were either made carelessly or for the purpose of

window dressing, and no further consideration will be given

to those contentions.

The only matter of substance in this case is the contention

made by the Plaintiff s that Georgia Code §§ 26-902 and

26-904 are unconstitutional and that all of these Defendants

were well aware of that fact, but nevertheless the De

fendants entered into an “ overt scheme and plan” , “ acting

in concert” , to deprive the Plaintiffs of their constitutional

rights and privileges, using these statutes for that purpose.

Assuming the burden of proving this contention, the

Plaintiffs ask that this Court enjoin the Defendants from

further enforcement of these statutes and from further

prosecution of the criminal actions against the Plaintiffs

Wells and Harris based upon the warrants issued as here

tofore described.

It appears to be conceded by all concerned that no prose

cution may be had under Georgia Code § 26-902 in the light

of the decision by the United States Supreme Court in

Herndon v. Lowry, 301 U. S. 242, 57 S. Ct. 732, 81 L. Ed.

1066 (1937), but the evidence before us would not justify a

9a

finding that the Defendants were well aware of that decision

and nevertheless entered into a scheme between themselves

to cause an arrest to be made for the purpose of depriving

the Plaintiff Wells of his constitutional rights. The Chief

of Police who swore out the warrant based on Code § 26-902

against Plaintiff Wells may have had some information

concerning the invalidity of that Code Section, but he is

not a person versed in the law and it would require specu

lation on our part to conclude that his action in using an

invalid statute was with deliberate intent to deprive the

person arrested of some constitutional right. The Defen

dant Manly simply made an investigation in his capacity as

Chief of Detectives and the Justice of the Peace, Judge

Thornton, issued the warrant in the same routine fashion

in which warrants are usually issued by a Justice of the

Peace and the Defendant Hand, the Solicitor General, is

not shown to have even had any connection with the matter

until several days after the warrant had been issued when

it became a state court concern, and when he determined

that § 26-902 had been held to be unconstitutional he di

rected that the charges pending against the Plaintiff Wells

based upon § 26-902 be abandoned, and subsequently he

caused the Grand Jury to return a no-bill in that connec

tion. As soon as the Solicitor General advised Mr. Pritchett

that proceedings could not be had under § 26-902 the Police

Chief abandoned any thought of further prosecution and

the Plaintiff Wells was released from custody. All of this

was. accomplished before this complaint was filed and none

of these circumstances indicate to us the existence of a

scheme or a plan among these Defendants as charged in

the complaint. Further, during the course of the hearing

on this matter Chief Pritchett testified that he had no inten

10a

tion of making any further arrests based upon § 26-902, and

Solicitor General Hand has made it clear to this Court from

the inception of this matter that he has no intention of

prosecuting any such case. It is apparent that this Court’s

injunction to restrain these Defendants, or any of them,

from the further use of § 26-902 is neither necessary nor

needed.4

With regard to the charges pending against the Plaintiffs

Wells and Harris based upon the alleged violation of

Georgia Code § 26-904, we are asked by the Plaintiffs to en

join further prosecution in the state court based on this

Code Section on the ground that this section is also uncon

stitutional. The theory of the Plaintiffs is that § 26-904 is

related to § 26-902 and since § 26-902 is unconstitutional it,

therefore, follows that § 26-904 is likewise invalid. We do

not think that this necessarily follows. It is true that both

of these sections relate to the subject of “ insurrection” , but

these Code sections were not enacted at the same time as

companion measures, they do not prescribe the same penal

ties and § 26-904 embraces matters not dealt with by § 26-

902.

Under the provisions of § 26-904 prosecution can be had

for matters having to do with subjects other than insurrec

tion and the offense is not simply the circulating of papers

but the doing of those acts for the purpose of inciting in

surrection, riot, conspiracy or resistance against the lawful

authority of the state, or against the lives of the inhabitants

thereof. Assuming a properly prepared indictment under

this section, the prosecutor would only have to prove the

4 The facts recited in this memorandum opinion are to be con

sidered as findings of fact within the meaning of Rule 52, F. R.

Civ. P.

11a

purpose of inciting one of those proscribed activities. It

could be simply riot. It is true that the warrant which was

issued in these cases by the Justice of the Peace refers to

“ insurrectionary papers” by which it is claimed the De

fendants “ attempted to incite insurrection” , but in Georgia

the true character of a criminal accusation or indictment is

not fixed by the denomination of the crime given to it by the

pleader, but rather by the particular allegations of the in

dictment, that is to say, the name which is given to the crime

which is charged in the accusation or indictment does not

characterize the offense but the nature of the crime is de

termined from the description of the crime alleged to have

been committed. Owens v. State, 92 Ga. App. 61, 87 S. E.

2d 654; Brusnighan v. State, 86 Ga. App. 340, 71 S. E. 2d

698. Neither of these Plaintiffs has yet been indicted by

the Grand Jury. If they are indicted that part of the indict

ment which would ultimately control would be the factual

allegations set out in support of the alleged violation of the

statute and that portion of the indictment could just as well

establish a charge of inciting a riot as inciting to insurrec

tion. This Court at this stage of this matter refrains from

expressing any view concerning the constitutionality of

Georgia Code § 26-904 having in mind that a presumption

of constitutionality attaches to all state statutes and if any

state of facts reasonably can be conceived that will sustain

the statute as against an alleged violation of the federal

Constitution the existence of that state of facts, must be

presumed. Spahos v. Mayor, etc. of Savannah Beach, 207

F. Supp. 688 (D. C. Ga., 1962), affirmed 371 U. S. 206, 83

S. Ct. 304, 9 L. Ed. 2d 269.

Even if it should ultimately be determined that Georgia

Code § 26-904 as applied to these Plaintiffs is Unconstitu

12a

tional, the Plaintiffs are not without adequate remedy and

protection short of the issuance of this Court’s injunction.

Federal courts of equity have traditionally been loathe to

restrain criminal proceedings in the state courts even on

constitutional grounds when all of the constitutional issues

can be decided in the first instance as a matter of course by

the state courts. Douglas v. City of Jeanette, 319 U. S. 157,

63 S. Ct. 877, 87 L. Ed. 1324 (1943). In the absence of an

affirmative showing to the contrary this Court cannot an

ticipate erroneous action by the state trial and appellate

courts and we should not do so for considerations of both

law and policy, the policy referred to being the desirability

of avoiding wherever possible conflicts between the state

and federal judicial systems.

.. “ Ordinarily, there should be no interference with such

(state) officers; primarily, they are charged with the

duty of prosecuting offenders against the laws of the

state, and must decide when and how this is to be done.

The accused should first set up and rely upon his de

fense in the -state courts, even though this involves a

challenge of the validity of some statute, unless it

plainly appears that this course would not afford ade

quate protection. The Judicial Code provides ample

opportunity for ultimate review here in respect of fed

eral questions. An intolerable condition would arise,

if, whenever about to be charged with violating a state

law, one were permitted freely to contest its validity

by an original proceeding in some federal court.” Fen

ner v. Boykin (1926), 271 U. S. 240, 243, 46 S. Ct. 492,

493, 70 L. Ed. 927.

13a

There has been no showing here that these Plaintiffs will

not be afforded adequate protection with respect to their

contentions in the state court. As already noted, the alleged

invalidity of a state law is not of itself grounds for equi

table relief in a federal court. The controlling question is

whether the Plaintiffs have made a sufficient showing that

the need for equitable relief by injunction is urgent in order

to prevent great and irreparable injury. American Fed

eration of Labor v. Watson, 327 U. S. 582, 66 S. Ct. 761, 90

L. Ed. 873 (1946). The injunctive relief sought in this com

plaint against the enforcement of a state penal statute, even

if that statute is contrary to the federal Constitution, must

be measured by the extraordinary circumstances rule and

considerations of whether the danger of irreparable loss is

both great and immediate. The mere fact that the Plaintiffs

may be convicted in the state court does not create such

extraordinary circumstances as would justify an injunction

and it has been frequently held that a federal court should

not ordinarily interfere with state officers charged with the

duty of prosecuting offenders against state law.

“ That equity will stay its hand in respect to criminal

proceedings, always when they are pending, and ordi

narily when they are threatened, is a rule of wide and

general application under our legal system. * * It is

a principle expressing a sound policy that the processes

of the criminal law should be permitted to reach an

orderly conclusion in the criminal courts where they

belong.” Ackerman v. International Longshoremen’s

& Warehousemen’s Union, 187 F. 2d 860, 868 (9 Cir.,

1951), cert. den. 342 U. S. 859, 72 S. Ct. 85, 96 L. Ed.

646.

14a

There are no circumstances in this case which create a

great and immediate danger of irreparable loss to the

Plaintiffs Wells and Harris. Neither of them is being held

without bond, neither of them is in jail, neither of them is

without remedy in the state court, neither of them has been

deprived of any right of defense in the state court. Indeed,

there is no showing that either of them will be damaged in

any way beyond the normal concomitants of a criminal

prosecution. The plaintiffs simply desire that this Court

determine a constitutional question which, in the view of

this Court, should be first considered by the state court.

We note that the Plaintiffs suggest that although the