E-mail From Smiley to Stein RE: McMahan, Weber, and Cohen Depositions

Administrative

September 1, 1999

1 page

Cite this item

-

Case Files, Cromartie Hardbacks. E-mail From Smiley to Stein RE: McMahan, Weber, and Cohen Depositions, 1999. 4f5d00a5-f10e-f011-9989-002248226c06. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/3bea2f5a-a71a-480a-a472-3377fcbaca53/e-mail-from-smiley-to-stein-re-mcmahan-weber-and-cohen-depositions. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

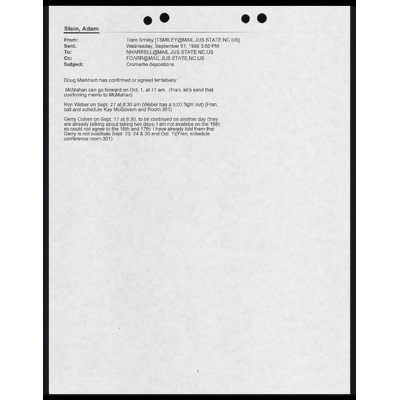

From: Tiare Smiley [TSMILEY@MAIL.JUS.STATE.NC.US]

Sent: Wednesday, September 01, 1999 3:50 PM

To: NHARRELL@MAIL.JUS.STATE.NC.US

Cc: FCARR@MAIL.JUS.STATE.NC.US

Subject: Cromartie depositions

Stein, Adam

Doug Markham has confirmed or agreed tentatively:

McMahan can go forward on Oct. 1, at 11 am. (Fran, let's send that

confirming memo to McMahan)

Ron Weber on Sept. 27 at 8:30 am (Weber has a 5,03 flight out) (Fran,

call and schedule Kay McGovern and Room 301)

Gerry Cohen on Sept. 17 at 8:30, to be continued on another day (they

are already talking about taking two days; | am not availabe on the 16th,

so could not agree to the 16th and 17th: | have already told them that

Gerry is not availbale Sept. 23, 24 & 30 and Oct. 1)(Fran, schedule

conference room 301)