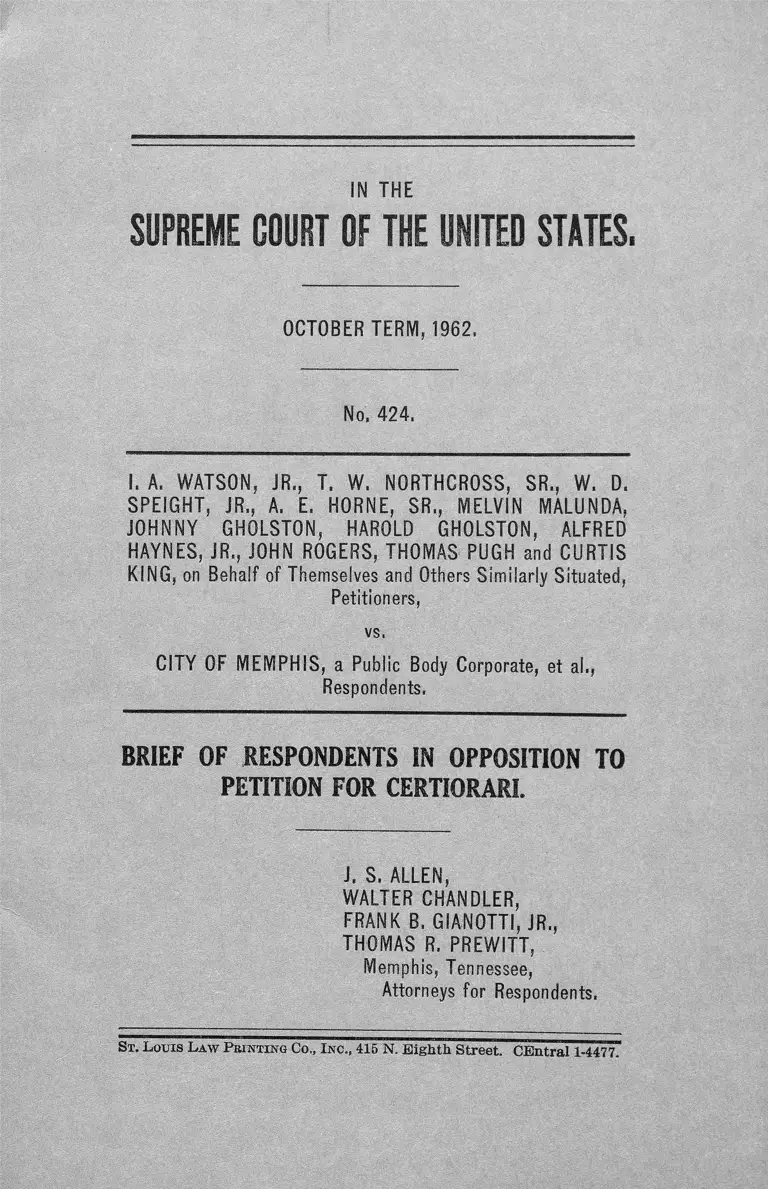

Watson v. City of Memphis Brief of Respondents in Opposition to Petition for Certiorari

Public Court Documents

October 1, 1962

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Watson v. City of Memphis Brief of Respondents in Opposition to Petition for Certiorari, 1962. 4bfbf8c7-c89a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/3bf78b89-2c0f-455f-ab22-afd55754b663/watson-v-city-of-memphis-brief-of-respondents-in-opposition-to-petition-for-certiorari. Accessed February 11, 2026.

Copied!

IN THE

SUPREME COURT OF THE UNITED STATES,

OCTOBER TERM, 1962,

No, 424.

I. A. WATSON, JR,, T. W, NORTHCROSS, SR,, W. D,

SPEIGHT, JR,, A, E, HORNE, SR,, MELVIN MALUNDA,

JOHNNY GHOLSTON, HAROLD GHOLSTON, ALFRED

HAYNES, JR,, JOHN ROGERS, THOMAS PUGH and CURTIS

KING, on Behalf of Themselves and Others Similarly Situated,

Petitioners,

vs,

CITY OF MEMPHIS, a Public Body Corporate, et al.,

Respondents,

BRIEF OF RESPONDENTS IN OPPOSITION TO

PETITION FOR CERTIORARI.

J, S, ALLEN,

WALTER CHANDLER,

FRANK B. GIANOTTI, JR.,

THOMAS R. PREWITT,

Memphis, Tennessee,

Attorneys for Respondents,

St. L ouis Law Pbinting Co„ Inc., 415 N. Eighth Street. CEntral 1-4477.

INDEX.

Page

Question Presented..............................., ........................, 1

Statement of the Case.................................... 2

‘ ‘ Pink Palace Museum ” ................................................ 9

Argument..................... 12

Pink Palace Museum.............. 17

Conclusion .................................................. 19

Appendix—Opinion of Trial Court................................ 21

Cases Cited.

Aaron v. Cooper, 243 Fed. 2d 361 (8th Cir., 1957 )..... 13

Board v. Baker, 124 Tenn. 39, 134 S. W. 863 (1910). . 17

Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka, 349 IT. S.

294, 75 S. Ct. 753, 99 L. Ed. 1083 (second decision

decided May 31, 1955)..................................12,13,16,17

Charlotte Park & Recreation Commission v. Barringer,

242 N. C. 311, 88 S. E. 2d 114 (1955)...................... 17

City of Montgomery v. Gilmore, 277 Fed. 2d 364 (5th

Cir., 1960)....................................................................... 15

Cummings v. City of Charleston, 288 Fed. 2d 817 (4th

Cir., 1961)............................... 15

Detroit Housing Commission v. Lewis, 226 Fed. 2d 180

(6th Cir., 1955)........................................................... 16

Florida ex rel. Hawkins v. Board of Control, 350 U. S.

413(1956)....................................................................... 12

Harrison v. NAACP (1959), 360 U. S. 167, 3 L. Ed,

2d 1152, 79 S. Ct. 1925..........................................,18,1.9

11

Kelley v. Board of Education of City of Nashville,

270 Fed. 2d 209 (6th Cir., 1959)..............................12,13

Meccano, Ltd. v. John Wanamaker, 253 U. S. 136, 141,

40 S. Ct. 463, 64 L. Ed. 822......................................... 16

Meridian v Southern Bell Telephone & Telegraph Co.

(1959), 358 U. S. 639, 3 L. Ed. 2d 562, 79 S. Ct. 455.. 18

National Fire Ins. Co. of Hartford v. Thompson, 281

U. S. 331, 338, 50 S. Ct. 288, 74 L. Ed. 8 8 1 . . . . . . . . . 16

Rippv v. Borders, 250 Fed. 2d 690 (5th Cir., 1957).... 16

Sweatt v. Painter, 339 H. S. 629............. ..................... 13

Thibodaux v. Louisiana Power & Light Co. (1959),

360 U. S. 25, 3 L. Ed. 2d 1058, 79 S. Ct. 1070............. 18

United States v. W. T. Grant Co., 345 U. S. 629, 633,

73 S. Ct, 894, 97 L. Ed. 1303..................................... . 16

Yarbrough v. Yarbrough, 151 Tenn. 221, 269 S. W. 36

IN THE

SUPREME COURT OF THE UNITED STATES.

OCTOBER TERM, 1962.

No. 424.

I. A, WATSON, JR., T. W. NORTHCROSS, SR., W. D.

SPEIGHT, JR., A. E. HORNE, SR., MELVIN MALUNDA,

JOHNNY GHOLSTON, HAROLD GHOLSTON, ALFRED

HAYNES, JR., JOHN ROGERS, THOMAS PUGH and CURTIS

KING, on Behalf of Themselves and Others Similarly Situated,

Petitioners,

vs.

CITY OF MEMPHIS, a Public Body Corporate, et al.,

Respondents.

BRIEF OF RESPONDENTS IN OPPOSITION TO

PETITION FOR CERTIORARI.

QUESTION PRESENTED.

No constitutional question is involved in this case. Re

spondents fully recognize and are actually applying the

established principle of constitutional law that Negroes

are entitled to make use, on a desegregated basis, of pub

lic parks and recreational facilities of the City of Memphis.

The only question presented in the lower courts in this

suit seeking injunction to require immediate and com

plete desegregation of the races in all the public parks

and recreational facilities operated by respondents was

whether the Trial Judge had the discretionary right, un

der the undisputed proof in this case, to deny the relief

sought and to approve plan of gradual integration.

STATEMENT OF THE CASE.

The Trial Court did hand down an Opinion (forming

part of the Judgment) and this Opinion is attached hereto

(App. lb). Petitioners make no attack on the correctness

of the Trial Court’s Findings of Fact; therefore, we as

sume that all Findings may be accepted as having been

sustained by competent proof. Reference to the Trial

Court’s Findings need be made for proper determination

of the question herein involved.

The City of Memphis has a population of approximately

five hundred thousand (500,000), thirty-seven per cent

(37%) of which are Negro, and sixty-three per cent

(63%) are White (1960 Census). Memphis is located in

the extreme southwest corner of Tennessee and is bounded

on the west by Arkansas and the south by Mississippi.

The population of the adjoining counties in Arkansas,

Mississippi and West Tennessee is predominantly Negro

(App. 106a).

There are 131 parks owned by the City of Memphis

and operated by Memphis Park Commission, 108 of which

are developed and in use. At the time of trial, 25 of these

parks were integrated, including Zoo, Art Gallery and

McKellar Lake Boat Dock. As respects the balance, with

very few exceptions, the parks reserved for Negroes are

in neighborhoods which are completely or predominantly

Negro; and likewise, the parks reserved for White people

are in neighborhoods which are completely or predomi

nantly White. In the City of Memphis, the races are sep

arated by neighborhoods, and the Park Commission has

consistently followed neighborhood patterns in providing

recreational facilities for members of both races; and it

has been its policy to remove restrictions applicable to

Negroes as neighborhoods are converted, by voluntary

action, from White to Negro, as early as practicable (App.

106a, 107a).

— 2 —

Recreational facilities operated by the Memphis Park

Commission were set out in the Trial Court’s Findings

of Fact. These facilities include 10 swimming pools—5

reserved for White use and 5 for colored; but since the

trial, the swimming pool in Malone Park has been changed

from White to Negro, leaving 6 swimming pools for Ne

groes and 4 for White. Respondents operate 61 play

grounds on City owned property—40 reserved for White

use and 21 for use by Negroes—together with 56 play

ground facilities operated by the Park Commission on

property owned by churches, private groups and the

School Board—30 of which are reserved for White use

and 26 for Negro. At the time of trial, there were 12

community centers with gymnasiums on City owned prop

erty—8 of which were reserved for White use and 4 for

colored; but, as pointed out by the Court of Appeals, the

Gaston Community Center, formerly reserved for White

use, has been changed since the date of trial in the Dis

trict Court. All 7 of the City owned golf courses, under

the plan as approved by the Trial Court, will be fully

desegregated by January 1, 1964. At the present time,

3 of the 7 golf courses are already integrated1 (App.

107a, 108a, 109a).

1 The fact that no Negro will be denied the privilege of play

ing golf during transition period is fully shown in the proof. At

time of trial in the District Court 5 o f the 7 golf courses were

reserved for White use and 2 for colored. In 1960, out of a total

o f 232,413 golf players on the 7 City courses less than 13,000 were

Negroes; thus, Negroes, comprising less than 6 % o f the golf play

ers, used approximately 30% of the public courses (App. 51a,

Exhibit 4 ), and Fuller Golf Course, formerly used only by Negroes,

but integrated, under the plan approved by the Trial Judge, on

February 1, 1962, is the finest in Memphis and potentially one of

the best in the United States (App. 74a).

A similar situation existed with respect to those Negro plaintiffs

who claimed discrimination in use of tennis courts. At the time

o f trial, those plaintiffs were playing tennis at Gooch Park and

others without charge, whereas, there was an admission fee at

John Rogers Tennis Courts (formerly reserved for Whites) ; and

the Gooch court was much closer to their homes (App. 32a. 34a,

4

In making the transition from a predominantly segre

gated park system to an integrated system, respondents

concluded, following much study, and after desegregation

of such city wide facilities (as distinguished from neigh

borhood parks and playgrounds), as the Zoo, Art Gallery

and McKellar Lake Boat Dock, that the 7 public golf

courses and Fairgrounds Amusement Park should be next

desegregated. This program was evolved because these fa

cilities involved areas which were less sensitive in the mat

ter of race relations than other areas, and which were less

likely to cause confusion and turmoil in the transition

period (App. 54a). Respondents’ plan as submitted to

the Trial Court took into account also that it would have

been unfair to desegregate Fairgrounds Amusement Park

in the middle of the year because of the effect it would

have had on rights of certain concession holders who op

erate under contract with the Park Commission (App.

49a). Other reasons in support of gradual integration are

set out in testimony of Harry Pierotti, Chairman of the

Park Commission, and H. S. Lewis, Director of Parks

(App. 54a, 55a, 56a, 75a, 82a, 83a, 84a).

The Recreational Department of the Memphis Park Com

mission is rated by competent authorities as the best in

the South. Its recreational program for Negroes is the

finest in the country. Approximately 100,000 children

participate in one or more of the recreational activities

sponsored by the Memphis Park Commission, and of this

number approximately 35,000 are Negroes. The Recrea

tional Department of the Park Commission sponsors many

and varied types of recreational activities, including, but

not limited to, competitive sports, such as baseball and

basketball, dancing, and many other activities. The Rec

reational Department headquarters itself is operated on

36a). Under the plan, John Rogers Tennis Courts were integrated

January 1, 1962, in accordance with suggestion of the Trial Court

(App. 111a).

5

an integrated basis, and all Negro Supervisors and Direc

tors are paid on the same salary schedule as the White

Supervisors and Directors; and the qualifications for such

Negro Supervisors and Directors are equal to or greater

than that of their White counterparts (App. 108a).

In finding that respondents were acting in good faith

in recognizing constitutional rights of Negroes to use of

public parks and facilities on an integrated basis, the

Trial Court gave consideration to the following:

(1) Importance of time to accomplish change-over from

a partially segregated system to an integrated one,

(2) Good will and understanding heretofore obtaining

between the races.

(3) The fact that, pending the transition period now in

progress, ample recreational facilities, under the operation

of the Park Commission, will be available to all Negro

citizens of Memphis, and no Negro will be denied the

right to avail himself of those facilities.

(4) Maintenance of law and order.

(5) Avoidance of confusion and turmoil in the com

munity.

(6) Revenues available from concessions operated on

park property.

(7) The fact that immediate integration would result

in a denial to a substantial number of citizens, both Negro

and White, of an opportunity to avail themselves of rec

reational facilities now afforded to all citizens of

Memphis.

(8) The constitutional and other legal rights of all citi

zens, both White and Colored (App. 110a).

The Trial Judge found as a fact that “ immediate forced

integration of all facilities of the Park Commission would

6

be unwise under all the circumstances as presented by the

proof. The plans and programs evolved by the Park Com

mission properly take into account the constitutional

rights of Negro citizens without overlooking many other

factors, as hereinabove set out” (App. 110a).

Although no attack is made on the correctness of the

lower court’s Findings of Fact, it is significant that the

proof showed, without dispute, that immediate forced in

tegration of all races in all parks and facilities would (1)

seriously impair the good will and understanding that has

heretofore obtained between the races in the City of Mem

phis2 (App. 50a); (2) result in a denial to a substantial

2 Marion Hale, Superintendent of Recreational Department of

Memphis Park Commission, with 36 years’ experience in field of

public recreation, testified :—

“ Q. Now, Mr. Hale, with reference to this integration prob

lem, and you recognize there is a problem you have to face

in your work, do you not?

A. Yes, sir.

Q. What effect, Mr. Hale,— and I want you to base your

answer on the years of experience you have had in the recrea

tion field dealing with both white and colored, would forced

integration, immediate integration, have on the recreation de

partment of the Memphis Park Commission ?

A. From my years of experience, Mr. Lawyer, sudden

recreation will create havoc.

Q. You mean sudden integration ?

A. I mean sudden integration.

I think we have a problem and me and my staff realize we

have a problem, and we are continually observing these prob

lems and trying to work them out, but if you were to order im

mediate integration of all our playgrounds no telling what

would happen.

I have heard it discussed about the violence and we all know

that is true.

I think there is another point that is important, is to see

the relationship broken down between the white and the col

ored. A relationship that we have worked so hard to build

up. A friendship, that through my thirty-six years has be

come increasingly fine, and I think that many, many play

grounds— I don’t think it, I know it,— would have to be closed

down and I think that you would need more supervision.

I think you would have lots and lots of violence, and irre-

gardless of who started it the violence will be there. I think

your playground system, if we integrate suddenly, would be

number of Negro citizens, as well as White, of recrea

t.ional facilities now available;3 (3) create great difficulties

ruined. I f we had a little time to give some deep thought

and consideration where we can work this thing out har

moniously for the good o f both races where we can work it

out and ponder over it and do it on a gradual basis. ..........

Q. Have you discussed this with your Negro supervisors?

A. I have discussed it many times.

Q. Are they in accord with your thinking?

A. Well, I have— I would hate to answer that question.

Yes, I would say they are in accord with my suggestion

here on the stand. Especially the supervisors."

(Transcript of Evidence, pp. 214-216.)

3 H. S. Lewis, Director of Parks, has been operating head of the

Memphis Park System for 16 years (App. 72a). Before that

time he had considerable experience in recreation work (App.

85a). He testified:—

"Q. If you are forced to integrate all of these recreational

facilities, in your opinion, Mr. Lewis, based on your dealings

with white and Negro alike, would that result in a denial to

these thirty-five thousand Negro children o f substantial recrea

tional facilities which they have been enjoying?

A. In my opinion, it will, yes.

Q. Why do' you think that is true, Mr. Lewis, and I will

ask you first if you are forced into that situation now without

being able to exercise any discretion o f your own, would you

have to have more or less supervisors and instructors?

A. You would have to have considerably more.

Q. What about policemen to patrol the various playgrounds

and parks?

A. In my opinion, we would have to have considerably

more policemen.

Q. Since opening up the Zoo, have you had to increase

the police protection there?

A. W e have.

Q. And if every other facility in Memphis were opened up,

in your opinion, would it also have to be increased ?

A. It would.

Q. And would that or not be a burden upon all the people

of the City of Memphis?

A. It would be a tremendous burden, yes.

Q. In your opinion, Mr. Lewis, is it going to take consid

erable time and a whole lot o f patience and understanding for

you and the other people who head the Park Commission to try

to work out this problem of racial integration in the public

parks ?

A. It will, quite a bit.

Q. Is it your desire to offer to every Negro child in Mem-

in maintaining law and order, while this difficulty will be

greatly diminished if integration is carried out on a grad

ual basis (App. 101a, 102a).

Petitioners introduced no proof whatever to refute the

showing made by respondents that harmful effects to both

phis the same treatment, the same facilities that are offered

to the white people?

A. That is what we try to do to the best of our ability.

Q. And is that the established policy of the Park Commis

sion ?

A. That is the policy, yes.

Q. Now. Mr. Lewis, have you worked with children quite

a bit in your capacity as head of the Park Commission ?

A. I have.

Q. And the Park Commission is necessarily closely related

and deals closely with many children, as you mentioned, about

a hundred thousand ?

A. Right.

Q. If the recreational program of the Memphis Park Com

mission is impaired by forced integration, what effect, in your

opinion, would that have on these thirty-five thousand Negro

children and sixty-five thousand white children ?

A. W e would have to ,. under the present budget, reduce

the number of playgrounds drastically in order to give them

full protection.

Q. And would that, or not, result in a denial of recreational

facilities to a great number of children, white and Negro?

A. It would.

Q. And in your opinion, would that have some relation to

juvenile delinquency then?

A. It certainly would.

Q. It speaks for itself, doesn’t it ?

A . Right.

Q. Do you try to keep as many children off the streets

as you can during the summer vacation period?

A. That is the purpose of our program, yes.

Q. And is one of the purposes of that to cut down on

juvenile delinquency?

A. It is, yes.

Q. For all children?

A. All children.

Q. Now, Mr. Lewis, you have studied this problem in other

cities in the country, both north and south ?

A. I have.

Q. And is your opinion based upon a survey of other cities

as well as your experience here in the City of Memphis for

the last sixteen years?

A. It is." (App. 83a to 83a.)

Negro and White people would follow if immediate in

tegration of the races in all parks and facilities were or

dered. As the Trial Judge, in his Opinion, so aptly

stated:

“No valid objection to this plan, in the Court’s

opinion, is offered in this case. The plaintiffs merely

say they want all these facilities fully integrated

now. Nothing else seems to matter.”

(App. 3b.)

-— 9 —

“PINK PALACE MUSEUM”.

The City of Memphis acquired “Pink Palace Museum”

and property on which it is located by deed dated August

2, 1926 from Garden Communities Corporation. This

deed provided that the property should be used for benefit

of White persons only and it reserved right of re-entry

for breach of such condition or covenant.4

4 Said deed provided:—

“ (c) Said building and grounds shall be devoted wholly and

exclusively to public uses for the benefit of persons of the

Caucasian race only and as a convervatory (sic), art gallery,

museum of art or natural histroy (sic), library and/or for

general recreational purposes in connection with the Memphis

Park System, including parks adjacent thereto; and said second

party, for itself and its successors, covenants and agrees that

it will not use, nor suffer or permit said property be (sic)

■ be used under its authority, for any other purpose that is ob

jectionable or offensive to the residents in said community;

and that in no event shall any part of said property be used

in connection with any business for private pecuniary profit,

but only and solely for public benefit, recreation and culture

as aforesaid.

(d ) In the event of a breach of either or any of the fore

going covenants or conditions in any substantial particular,

and such breaches shall continue for a period of ninety days

after written notice to Memphis Park Commission, or to the

commission, board or official to whom its functions may here

after be delegated, and after a copy of said notice shall be

delivered to the Mayor or other chief official of the party of

the second part, or its successor, such notice specifying the

breach complained of, and for which forfeiture is sought, then

the foregoing dedication or conveyance shall be and become

— 10

The “Advisory Board Memphis Museum” recom

mended to the Memphis Park Commission on January 6,

1959 that the Museum property be sold for residential

purposes and that a new Museum be built on other City

property. In response to this request, J. 8. Allen, Es

quire, the then Park Commission Attorney, submitted

comprehensive report and summary of titles to the prop

erty involved and stated in his report dated February 5,

1959 “that neither the City nor the Park Commission

could safely sell or cease the use for museum or park

purposes as to any of the respective properties conveyed

by these deeds.

Said report and opinion was made before the present

lawsuit was filed (App. 112a).

Respondents’ present policy with reference to “Pink

Palace Museum” is not based upon any effort to deny

Negro citizens of Memphis the right to use of this facility,

but rather is based upon a policy of attempting to pre

serve title to the property. Respondents have evinced

a willingness to remove all race restrictions obtaining at

said Museum, except for the fact that they feel a removal

of all restrictions based on race might result in a loss of

this valuable property to the City and the Park Commis

sion (App. 112a, 113a).

void at the option or election of said party of the first part,

or its assigns; and in such event if said breach is not remedied

and corrected within said period of ninety days, the party of

the first part, or its assigns may re-enter and take possession

of said mansion house and every part thereof, including the

aforedescribed parcel of land on which the same is located,

and hold the same as of its first and former estate therein,

with all additions or betterments, free of any claim of said

second party, or its successors. Provided, such forfeiture shall

not be permitted if such breach is wholly discontinued or

remedied within said period of ninety days. A waiver for any

period of time of a breach of either or any of the foregoing

covenants and conditions in any particular shall not preclude

a forfeiture for a continuance thereof after notice as above

specified.” (Exhibit 2.)

11 —

The lower Court, under doctrine of “abstention”, stayed

any adjudication with reference to said Museum and or

dered respondents to file action in the Chancery Court

of Shelby County, Tennessee, before September 15, 1961

to determine what effect integration of the races at said

Museum will have upon the City’s title (App. 120a). If

the State Court holds that the City’s title will not be

affected by integration of the races, the plan of respond

ents to integrate “Pink Palace Museum” can be carried

out and the District Court will not be called upon to make

any adjudication in regard thereto.5

5 Original Bill for Declaratory Judgment, pursuant to the lower

Court’s mandate, was filed in the Chancery Court of Shelby County.

Tennessee, on September 1, 1961, cause number 64064-2 R. D. The

relief therein sought is a declaratory judgment decreeing that re

spondents may remove all restrictions based on race in the use

and enjoyment of “ Pink Palace Museum" and certain adjacent

properties without jeopardizing or impairing title of the City of

Memphis to the properties in question.

ARGUMENT.

Petitioners perfected their appeal to the Court of Ap

peals before the Trial Court had an opportunity to pass

on respondents’ plan for integration of playgrounds and

community centers. The District Judge, in line with the

policy followed in Kelley v. Board of Education of City

of Nashville, 270 Fed. 2d 209 (6th Cir., 1959), cert. den.

361 U. S. 924, ordered respondents to submit a more com

plete plan by December 15, 1961. In view of the appeal,

of course, the hand of the Trial Judge has been stayed;

and in this state of the record it would, therefore, seem

that petitioners are not in any position to insist that

respondents’ plan for gradual desegregation is inadequate

or incomplete.

The question presented to the Court, of Appeals and to

this Court thus narrows itself to the proposition of whether

the District Judge, as a matter of law, was compelled to

enter an order requiring respondents to integrate the races

immediately in all public- parks and recreational facilities

of the City of Memphis, notwithstanding the undisputed

proof that it would be manifestly unwise to do so.

The crux of petitioners’ argument is that the Trial

Judge and the Court of Appeals had no discretion in

framing a decree in a suit of this character; and that the

traditional rules of equity, which obtain in injunction

cases and which are recognized in Brown v. Board of

Education of Topeka, 349 U. S. 294, 75 S. Ot. 753, 99 L. Ed.

1083 (second decision decided May 31, 1955), do not apply

in the field of public parks and recreation. The authority

cited by petitioners is Florida ex rel. Hawkins v. Board of

Control, 350 U. S. 413 (1956), in which the Court held

“ our second decision in the Brown case * * * had no

application to a case involving a Negro applying for ad

mission to a state law school.”

— 12 —

Petitioners also rely upon Sweatt v. Painter, 339 U. S.

629, which again involved the right of a Negro to attend

a state law school.

It is respectfully submitted that the authorities relied

upon by petitioners are not in point. No reason for

delay was advanced in the law school cases.

The principles announced in Brown v. Board of Educa

tion, supra, and further elaborated on in Aaron v. Cooper,

243 Fed. 2d 361 (8th Cir., 1957), and Kelley v. Board of

Education of City of Nashville, supra, seem most appro

priate here. In approving the Nashville plan of gradual

integration of the public schools, the Court in the Kelley

Case, said at 270 Fed. 2d at pages 225 and 227:

“ Cases involving desegregation, like other cases,

depend largely on the facts. While the law has been

stated, perhaps, as definitely as it can be stated at

the present time, by the Supreme Court, nevertheless,

its application depends upon the facts of each par

ticular case. ‘ [Because] of the great variety of local

conditions, the formulation of decrees in these cases

yjresents problems of considerable complexity.’ Brown

v. Board of Education, 347 U. S. 483, 495, 74 8. Ct.

686, 692, 98 L. Ed. 873. ‘Full implementation of these

constitutional principles may require solution of varied

local school problems. School authorities have the

primary responsibility for elucidating, assessing, and

solving these problems; courts will have to consider

whether the action of school authorities constitutes

good faith implementation of the governing constitu

tional principles. Because of their proximity to local

conditions and the possible need for further hearings,

the courts which originally heard these eases can best

perform this judicial appraisal.’ * # *

“ ‘ In fashioning and effectuating the decrees, the

courts will be guided by equitable principles. Tra-

ditionallv, equity has been characterized by a prac

tical flexibility in shaping its remedies and by a

facility for adjusting and reconciling public and pri

vate needs.’ Brown v. Board of Education, 349 U. S.

294, 299, 300, 75 S. Ct. 753, 765, 99 L. Ed. 1083. The

court further went on to say that at stake was the

personal interest of the plaintiffs in admission to the

public schools as soon as possible on a non-discrimina-

torv basis; that effectuating this interest may call for

elimination of a variety of obstacles in making the

transition; that courts of equity may properly take

into consideration the public interest in the elimina

tion of such obstacles; that, once a start is made, the

courts may find that additional time is necessary to

carry out the ruling in an effective manner.

-y. -y- I f i f _-V*

“ The complaint of appellants is that the plan does

not conform to the mandate that desegregation take

place with all deliberate speed. As Mr. Justice Frank

furter said in his concurring opinion in Cooper v.

Aaron, supra [358 IT. S. 1, 78 S. Ct. 1412]: ‘ Only the

constructive use of time will achieve what an ad

vanced civilization demands and the Constitution con

firms.’ In the Court of Appeals, in Aaron v. Cooper,

8 Cir., 243 F. 2d 361, it was observed that a reason

able amount of time to effect complete integration, in

certain places, might be unreasonable in other places.

It was said, in another case, that ‘ a good faith ac

ceptance by the school board of the underlying prin

ciple of equality of education for all children with

no classification of race might well warrant the allow

ance by the trial court of time for such reasonable

steps in the process of desegregation as appear to be

helpful in avoiding unseemly confusion and turmoil.’

Orleans Parish School Board v. Bush, 5 Cir., 242 F.

2d 156, 166.”

— 14 —

— 15

In City of Montgomery v. Gilmore, 277 Fed. 2d 364 (5th

Cir., 1960), the Court expressly held that the principles

announced in the second Brown decision should be used

by trial courts in formulating decrees with respect to

desegregation of public parks and recreational facilities.

In that case the Court of Appeals modified the lower

Court’s injunction so as to empower the Trial Court to

vacate injunction requiring the City of Montgomery to

operate all parks on a desegregated basis “ in the event

it should appear that the defendants may be able to plan

and act more effectively so as to reopen and operate the

parks within the framework of the Constitution if they

are freed from the restraining effects of the injunction.”

(277 Fed. 2d at p. 368.)

The principle of planned gradual integration in public

parks and recreational facilities is also recognized in

Cummings v. City of Charleston, 288 Fed. 2d 817 (4th

Cir., 1961). In that case Negro citizens of Charleston

sought immediate access to one municipal golf course. No

other public facilities were involved. In holding that no

delay (beyond six months from date of lower Court’s final

decision) was authorized, the Court said at 288 Fed. 2d at

p. 817:

“We have searched the record and have found no

evidence which would tend to explain the postpone

ment of the effective date of the injunction

order for what would seem to be an unreasonable

period of time. We do not hold or even intimate

that, if justifying circumstances were made to ap

pear, the trial court could not exercise its sound dis

cretion. But it is not apparent from the record that

any real administrative or other problems are here

involved such as are present in some of the school

desegregation cases. Indeed, the record discloses

nothing which would indicate that the injunction

16 —

could not have been made immediately effective.”

(Emphasis supplied.)

The principle of gradual integration, as announced by

this Court in the Brown case, has also been applied in the

field of public housing in the City of Detroit. Cf. Detroit

Housing Commission v. Lewis, 226 Fed. 2d 180 (6th Cir.,

1955).

In considering the action of the Trial Court in denying

the application for injunction, it should be borne in mind

that upon appeal the ruling of the lower Court will not

be disturbed unless contrary to some rule of equity or the

result of improvident exercise of judicial discretion.

Meccano, Ltd. v. John Wanamaker, 253 U. S. 136, 141,

40 S. Ct. 463, 64 L. Ed. 822; National Fire Ins. Co. of

Hartford v. Thompson, 281 U. S. 331, 338, 50 S. Ct. 288,

74 L. Ed. 881. The discretion of the District Judge is

necessarily broad and a strong showing of abuse must

be made to reverse it. United States v. W. T. Grant Co.,

345 U. S. 629, 633, 73 S. Ct. 894, 97 L, Ed. 1303.

It would seem that had the lower Court issued injunc

tion as prayed for, under the undisputed proof as shown

in this record, it would have been an abuse of discretion,

Cf. Rippy v. Borders, 250 Fed. 2d 690 (5th Cir., 1957),

Respondents recognize that the Memphis Park System

and its recreational facilities must under established law

be operated on a desegregated basis and that the former

system must be changed in compliance with the law as

announced by the Supreme Court. The only question

herein involved is the manner in which this desegrega

tion should take place. All of the proof introduced upon

the trial supports the conclusion that gradual integration,

as opposed to immediate integration, is in the best inter

est of all the citizens of Memphis, both White and Negro.

No proof was introduced by the petitioners to support

— 17

their contention that immediate integration is the proper

method of complying with the law as set forth in the

Brown and other cases.

Petitioners’ argument that a different rule of equity

practice should apply to public parks and recreational

systems, than is applied in public educational systems,

seems untenable on its face. Manifestly, in view of the

large numbers of people involved with respect to the

Memphis Park System, there will be problems inherent in

any transition from a segregated to a desegregated sys

tem. Those problems were carefully covered by the Trial

Court and the Court of Appeals.

Pink Palace Museum.

If the State Court declares, in suit now pending, that

integration of the races at “Pink Palace Museum” will

not jeopardize the City’s title to the property, there will

be no occasion for intervention of the Federal Court, with

respect to that facility, and respondents’ plan in regard

thereto can be carried out promptly.

Whether there now exists, in any person, firm or cor

poration a right of re-entry or right to claim a forfeiture

of the Museum property, for condition broken, is a ques

tion of State law. In Charlotte Park & Recreation Com

mission v. Barringer, 242 N. C. 311, 88 S. E. 2d 114 (1955),

a similar provision was held to be valid and the United

States Supreme Court denied certiorari, 350 U. S. 983

(1956).

Under applicable Tennessee decisions, however, it would

appear that probably no one has an enforceable right of

re-entry, for condition broken, with respect to the Museum

property. See Board v. Baker, 124 Tenn. 39, 134 S. W.

863 (1910); Yarbrough v. Yarbrough, 151 Tenn. 221, 269

S. W. 36 (1924). The question presented for determination

in the State Court, however, is, obviously, fraught with

complexities and difficulties, and cannot be safely resolved

without final adjudication.

If the State Court holds that there is presently an en

forceable right of re-entry, for condition broken, with

respect to the Museum, and the City is unable to acquire

such right of re-entry from the holder of such right, then

the constitutional question thereby presented can be deter

mined by the Federal courts.

The action of the Trial Judge in this case is in line with

many recent decisions of the United States Supreme Court,

including cases involving questions of civil rights. Harri

son v. NAACP (1959), 360 U. S. 167, 3 L. Ed. 2d 1152,

79 S. Ct. 1925; Thibodaux v. Louisiana Power & Light Co.

(1959), 360 U. S. 25, 3 L. Ed. 2d 1058, 79 S. Ct. 1070; Me

ridian v. Southern Bell Telephone & Telegraph Co. (1959),

358 U. S. 639, 3 L. Ed. 2d 562, 79 S. Ct. 455.

The authority of the District Judge to apply doctrine

of “ abstention” to present situation is exhaustively cov

ered in annotation entitled “ Discretion of federal court to

remit relevant state issues to state court in which no action

is pending.” 3 L. Ed. 2d 1827.

A clear statement of principle herein involved is set out

in the City of Meridian case, where the Court said at 358

U. S., pp. 640-641:

“ Proper exercise of federal jurisdiction requires

that controversies involving unsettled questions of

state law be decided in the state tribunals preliminary

to a federal court’s consideration of the underlying

federal constitutional questions. See Railroad Com.

v. Pullman Co., 312 U. S. 496, 85 L. Ed. 971, 61 S. Ct.

643. That is especially desirable where the questions,

of state law are enmeshed with federal questions..

— IS —

19 —

Spector Motor Service, Inc., v. McLaughlin, 323 U. S.

101,105, 89 L. Ed. 101,103, 65 S. Ct. 152. Here the state

law problems are delicate ones, the resolution of which

is not without substantial difficulty—certainly for a

federal court. Ct. Thompson v. Magnolia Petroleum

Co., 309 U. S. 478, 483, 84 L. Ed. 876, 880, 60 S. Ct.

628. In such a case when the state court’s interpreta

tion of the statute or evaluation of its validity under

the state constitution may obviate any need to con

sider its validity under the Federal Constitution, the

federal court should hold its hand, lest it render a

constitutional decision unnecessarily.”

In Harrison v. NAACP, supra, the Supreme Court held

that the District Court should have abstained from ruling

on constitutionality of Virginia statutes until a construc

tion of the statutes could be made by the Virginia courts

“ which might avoid in whole or in part the necessity for

federal constitutional adjudication, or at least materially

change the nature of the problem.” In that case the Court

said:

“ This principle does not, of course, involve the ab

dication of federal jurisdiction, but only the post

ponement of its exercise; it serves the policy of comity

inherent in the doctrine of abstention; and it spares

the federal courts of unnecessary constitutional adju

dication. See Chicago v. Fieldcrest Dairies, Inc., supra

(316 U. S. at 172, 173).”

(360 U. S. at p. 177.)

CONCLUSION,

The Trial Court and the Court of Appeals have found

that respondents have acted and are acting in good faith in

attempting to comply, in the field of recreation, with the

opinion of the Supreme Court in the Brown case.

The Court of Appeals has held that “ there was a proper-

exercise of discretion by the District Court in denying in

junctive relief, in providing for a plan of desegregation to

be filed by the Park Commission with the court, and in re

serving jurisdiction for further proceedings in the case;

* * Consequently, the petition for writ of certiorari

should be denied.

Respectfully submitted,

J. S. ALLEN,

WALTER CHANDLER,

FRANK B. GIANOTTI, JR.,

THOMAS R, PREWITT,

Attorneys for Respondents.

-— 21

APPENDIX FOR RESPONDENTS.

OPINION OF TRIAL COURT.

(Docket No. 9, Part of Judgment; Transcript of Evi

dence, p. 268 et seq., Docket No. 12.)

The Court: Gentlemen, we have had a full hearing today

of all the matters involved, and here briefly are the

Court’s views.

The plaintiffs, invoking the Court’s injunctive powers,

are asking in this proceeding that the defendants be en

joined forthwith from operating certain public facilities

under the jurisdiction of the Park Commission of the City

of Memphis, including golf courses, tennis courts, play

grounds, parks, and the Pink Palace Museum, upon a

racially segregated basis.

Restrictions on a number of the facilities here involved,

including the Brooks Memorial Art Gallery, the boat dock

at McKellar Lake, and the zoo, were lifted some time ago.

At least twenty-one parks, I believe, are now open to

general use without restriction.

Now, the defendants are voluntarily proposing in this

proceeding to remove the restrictions with respect to the

amusement facilities at the Fairgrounds, and all munici

pal golf courses, according to a plan which they claim

is necessary to an orderly transition of its heretofore seg

regated system to one which will admit all comers with

out regard to race or color.

The defendants seem to have no objection to a removal

of the restrictions with respect to the Pink Palace Mu

seum, but because of certain expressed conditions in the

deed conveying this property to the city over thirty-five

years ago, there is a risk which might result in a reverter

to the original grantor, or its successors. That is, in the

event of the integration of that facility. With respect to

— 22 —

this particular facility, the defendants are requesting of

the Court at this time that the legal questions involved

be left to the state courts for a ruling under the doctrine

of abstention.

Now, the City of Memphis, through its Park Commis

sion, carries on a very large and extensive operation in

the City of Memphis. Its activities are many and varied.

All things considered, the plan it proposes in this pro

ceeding to take care of the Fairgrounds amusement facil

ities and the golf courses the Court is convinced is about

as good as can be devised. In getting up this plan, many

things necessarily had to be considered. The effective

dates with respect to one or two of the golf courses are

projected into the future to some extent, but the whole

program under the plan, as the Court understands, may

and will be accelerated in the light of new developments.

The Court is well satisfied it is the purpose of the de

fendants to do this with all deliberate speed.

Of course, in passing upon this plan, local conditions

to be encountered with respect to maintenance of law and

order, the avoidance of violence and confusion in the

community, revenues available from concessions, though

not absolutely controlling, may, among many other things,

as practical matters be weighed and considered by the

Court on application for an injunction of the type here

sought. Time to organize the change-over to integration

after all of these years is to the Court important. The

legal rights of all citizens, white and colored, are not to be

overlooked in what we do here today.

Apparently the defendants have given consideration to

these matters. And they, as I say, are matters for the

Court to consider on application for the injunctive relief

sought.

It is true no ease dealing with a plan or program of

integration of facilities as here involved is cited, hut

we do know that onr Court of Appeals in Kelly against

the Nashville Board of Education, cited by the defend

ants, approved a so-called stairstep plan for integrating

the Nashville schools. The reason in that case seems to

the Court to have application in this case. The problems

here are somewhat comparable to the problems faced by

the Nashville schools.

No valid objection to this plan in the Court’s opinion

is offered in this case. The plaintiffs merely say they

want all of these facilities fully integrated now. Nothing

else seems to matter.

The Court believes that good will and understanding

between the races in this city can be best preserved and

promoted by the plan here suggested by the defendants.

The defendants, who are high minded public officials,

have put much thought and effort into this plan. It is

sound, fair, feasible and equitable. It is reasonable and

within the spirit of the law, and the Court is convinced

is proposed in utmost good faith. The Court approves

it in all things.

It should be stated here that pending the transition

period under the plan offered, no citizen will be deprived

of his right to play golf or to avail himself of other ac

tivities sponsored by the Memphis Park Commission.

With respect to the Pink Palace Museum, the Court

thinks it wise that it stay any adjudication which might

affect the title to this valuable property until the state

courts can have an opportunity to decide the complex

questions involved. The doctrine of abstention in mat

ters of this nature of course has been recognized by the

•courts, including the Supreme Court, many times.

The Court thinks the defendants, however, should take

the initiative on this particular matter and get a suit

under the declaratory judgment act of Tennessee filed in

24

the Shelby County Chancery Court. This should be done

within ninety days. Incidentally, it occurs to the Court

that additional parties will be necessary to a full adjudi

cation of the matter. But this, of course, will be left for

you lawyers to decide.

The John Rogers tennis courts on Jefferson Avenue

in all probability will be abandoned as such at an early

date before the year is out according to the proof, since

the ground upon which they stand, presently owned by

the City of Memphis, is too valuable for the purpose for

which they are presently being used and plans are on foot

to sell the property. The Court suggests to the defendants

under their over-all plan that they consider opening up

these particular facilities by January 1, 1962, on an inte

grated basis if the property has not been disposed of by

the City or the tennis courts at that location are not

abandoned.

Now, no plan is offered in this proceeding concerning

the integration of other recreational facilities of the Park

Commission. That is, the playgrounds and community

centers. The proof is that integration of the races and

utilization of these facilities is a matter which in the in

terest of all the citizens of Memphis calls for more study.

The defendants are not prepared to offer a plan to cover

this highly important phase of the Park Commission’s

activities at this time. The Superintendent of this depart

ment has been asked by the Park Commission to get up

a plan which will accomplish this objective. The proof

is that a target date for such integration of the races in

the use of these particular facilities cannot be set at this

time. As the Court understands, additional time is neces

sary for additional study and planning for an orderly

transition of these activities on an integrated basis.

The Court in the circumstances will not order through

injunction at this time the immediate integration of these

particular recreational facilities of the Memphis Park

Commission. It would be unwise for the Court to do so

for many reasons. Additional time in the Court’s opinion

is of the essence. It is absolutely necessary for a full con

sideration of this troublesome matter by the defendants

so that adequate plans for the transition may be devised

and agreed upon.

The Court will hold this case open so that these partic

ular matters can be given further study and consideration

by the Board of Park Commissioners. The proof is that

something in the way of a plan could be read}? for sub

mission to the Court in approximately one to two years.

The Court in the circumstances does invite the Depart

ment to submit such a plan in this proceeding, but thinks

this should be done within a period of six months.

Since the defendants have been acting for some time

on a voluntary basis and have desegregated a number of

its facilities, and are in perfect good faith proceeding-

in an orderly and effective manner to complete the whole

job with respect to those remaining which are here in

volved, the Court rules that an injunction is unnecessary.

So, gentlemen, get up a judgment right away approving

the plan submitted with respect to the Fairgrounds and

the golf courses and sustaining the defendants’ request

for stay with respect to the Pink Palace Museum, so that

the state courts may pass upon the questions there in

volved.

The judgment should also provide for the filing of a

plan with respect to the playgrounds and community

centers within six months.

The costs in this proceeding will be equally divided

between the plaintiffs and defendants.

Now, the Court in these remarks has only hit the high

spots. They will serve, at least temporarily, as the Court’s

— 26

findings and conclusions under the rules. Others in more

detail will probably be necessary, so the Court suggests

you gentlemen who represent the defendants might within

the next week get up additional ones to be filed with the

Court. The Court will need an original and about five

copies.

Counsel for the plaintiffs may if they desire also pro

pose findings and conclusions to the Court.

All right, if there is nothing further, Mr. Clerk, adjourn

court until tomorrow morning at nine-thirty.