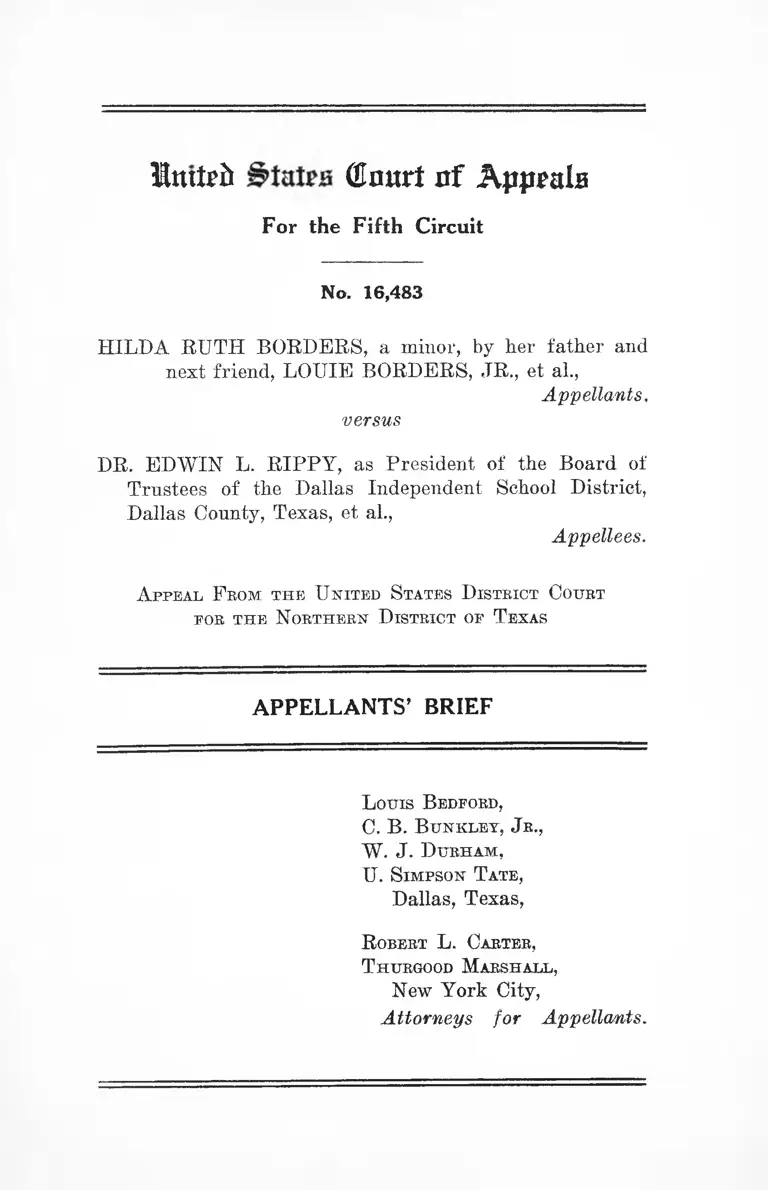

Borders v. Rippy Appellants' Brief

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1957

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Borders v. Rippy Appellants' Brief, 1957. b7fcb122-ca9a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/3c0f13a5-717e-4ae4-83f4-2295638bff1f/borders-v-rippy-appellants-brief. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

littteii (Enart of Appeals

For the Fifth Circuit

No. 16,483

HILDA RUTH BORDERS, a minor, by her father and

next friend, LOUIE BORDERS, ,TR., et al.,

Appellants,

versus

DR. EDWIN L. RIPPY, as President of the Board of

Trustees of the Dallas Independent School District,

Dallas County, Texas, et al.,

Appellees.

A ppeal F rom the U nited S tates D istrict Court

eor the N orthern D istrict of T exas

APPELLANTS’ BRIEF

L ouis B edford,

C. B. B unkley, J r.,

W . J . D u r h a m ,

U. S impson T ate,

Dallas, Texas,

R obert L. Carter,

T hurgood Marshall,

New York City,

Attorneys for Appellants.

Initefc States (Eourt nf Appeals

For the Fifth Circuit

No. 16,483

--------------------------------------------------- o ----------------------------------------- •—

H ilda R uth B orders, a m inor, by her fa th e r and

next friend , L ouie B orders, J r., et al.,

Appellants,

versus

Dr. E dwin L. R ippy , as President of the Board of Trustees

of the Dallas Independent School District, Dallas

County, Texas, et al.,

Appellees.

A ppeal F rom the U nited States D istrict Court

for the N orthern D istrict of T exas

— _ _ — ---------- --------------o — ------------------— — —

APPELLANTS’ BRIEF

For the second time this case is here on appeal from a

judgment denying appellants the relief, which they sought,

and dismissing the cause without prejudice. The claims of

the parties and the issues raised in their pleadings are

those which this Court described in its decision on the

earlier appeal. 233 F. 2d 796, rev‘g 133 F. Supp. 811.

On December 19, 1956, pursuant to this Court’s direc

tion, the parties were afforded a full hearing. The eviden

tiary facts there adduced are not in dispute: The Dallas

Independent School District consists of 134 school build

ings, a professional staff of 3,800 and 119,000 pupils—

2

16% percent of which are Negroes (R. 91, 95). One hun

dred twelve of the school buildings (9 senior high schools,

10 junior high schools, 1 vocational school and 92 elementary

schools) are operated for white pupils exclusively; the re

maining 22 (3 senior high schools, 19 elementary schools)

are for Negro pupils (R. 97, 98).

On September 5, 1955, a regular day for registration

in the Dallas public schools (R. 103), minor appellants

sought admission into elementary and secondary schools-—

all operated for white children only—which are the schools

closest to their homes (R. 61-62, 66-67, 70-71, 74-75, 77-78,

104-105). They were refused admission by the principals

of these schools, each of whom informed minor appellants’

parents that the refusals were pursuant to a directive of

the Board of Trustees (R. 62, 67, 71-72, 75, 78, 105), which

in July 1955, had passed a resolution ordering that neither

integration nor any alteration in the existing status of the

schools was to be effectuated during the 1955-56 term (R.

84-85). Subsequently, a similar resolution for the 1956-57

school year was passed by the Board (R. 90).

“ Consistent with the Board of Education’s adopted

policy, and pending further decrees of the court,” an

uncrowded white high school was converted to an all Negro

school beginning with the 1956-57 school year (R. 86) ; and

an uncrowded white elementary school had been previously

assigned to Negroes for the 1955-56 term (R. 89).

In the text accompanying the 1955 resolution, the Board

stated that months prior thereto it had instructed the

Superintendent of Schools to proceed with a detailed study

of the problems inherent in desegregation and that studies

3

in twelve areas1 were then in progress (R. 93-94), The

Board also insisted that it would not direct any change

until its study and understanding of the problems involved

were completed and its plans worked out to the minutest

detail (R. 94). A like statement accompanied the 1956

resolution and, in addition, reported that studies in six

of the twelve areas had been completed and presented to

the Board (R. 91).

The Superintendent, under whose supervision these

studies had been made, reported that, if there was immedi

ate desegregation, integration would occur in 8 (and pos

sibly 9) of the white and all 3 of the Negro senior high

schools; and that there would be nonsegregated classes in

about 37 of the white and 14 of the Negro elementary

schools (R. 109). The effectuation of nonsegregated school

ing, according to the Superintendent, would cause some

overcrowding in schools serving some communities; but no

1 “1. Scholastic boundaries of individual schools with relation to

racial groups contained therein.*

“2. Age-grade distribution of pupils.*

“3. Achievement and state of preparedness for grade-level assign

ment of different pupils.*

“4. Relative intelligence quotient scores.*

“5. Adaptation of curriculum.*

“6. The over-all impact on individual pupils scholastically when

all the above items are considered.

“7. Appointment and assignment of principals.

“8. The relative degree of preparedness of white and Negro

teachers; their selection and assignment.*

“9. Social life of the children within the school.

“10. The problems of integration of the Parent-Teacher Associa

tion and the Dads Club organization.

“11. The operation of the athletic program under an integrated

system.

“12. Fair and equitable methods of putting into effect the decree

of the Supreme Court” (R. 93-94).

* The asterisks indicate the studies which had been completed at the time

of the trial (R. 108).

4

overcrowding would result elsewhere (R. 110), including

the schools which had been transferred to Negro pupils

(R. 114-115).

He also stated that Negro students, on the average, were

less mature intellectually than white students on the same

grade levels (R. 111-113) and that, if Negro and white

children were placed together at the grade level where

they are presently enrolled, it would produce a confused

instructional pattern and create learning problems (R. 111-

113). Moreover, if Negro children were placed at grade

levels commensurate with their level of intellectual matur

ity, they would be over-age and over-sized for their social

group (R. 113)—ranging from being iy2 years older in the

first grade to 3y2 years older in the last year of senior high

school (R. 113). Be this as it may, the Superintendent

admitted that no white children were refused admission to

schools designated for them because of retardation (R. 114).

Upon consideration of this evidence and the pleadings,

the trial court issued an opinion and judgment immediately

after both sides closed (R. 129-132). Concluding that the

appellees had been seeking to integrate, but so far had not

succeeded, that appellees were doing their very best to

comply with the ruling of the Supreme Court of the United

States, and, that there was no equity here, the District

Judge denied an injunction and dismissed the suit without

prejudice “ in order that the School Board may have ample

time, as it appears to be doing, to work out this problem.”

(R. 132).

Specification of Errors Relied Upon

1. The District Court erred in refusing to apply the

standards set forth by the Supreme Court and this Court

to the facts in the instant case.

2. The District Court erred in dismissing the suit.

0

ARGUMENT

I. The D istrict Court E rred In Refusing To Apply

The S tandards Set Forth By The Suprem e Court And

This Court To The Facts In The Instan t Case.

In the School Segregation Cases the Supreme Court

set out certain criteria for action and limitations upon the

discretion of district courts considering cases involving

segregation in public education. Among these criteria and

limitations are: (1) that the school board “ make a prompt

and reasonable start toward full compliance with our May

17, 1954 ruling” ; (2) the school board has the burden of

proof in showing that time is necessary for “ good faith

compliance at the earliest practicable date” ; (3) that Dis

trict Courts enter such orders and decrees “ to admit to

public schools on a racially nondiscriminatory basis with

all deliberate speed” the parties in the cases; and (4)

“ [djuring this period of transition, the courts will retain

jurisdiction of these cases.” Brown v. Board of Educa

tion, 349 U. S. 294, 300-301.

In a case similar to the one at bar where school officials

were conducting studies, holding meetings, passing resolu

tions and appointing committees to work out plans for

integration the lower court dismissed the case as being

“ precipitate and without equitable justification.” 2 This

Court reversed, Jackson v. Rawden, 235 F. 2d 93, cert,

denied, 352 U. S. 925, and said at page 96:

“ We think it clear that, upon the plainest princi

ples governing cases of this kind, the decision ap

pealed from was wrong in refusing to declare the

2 “The School Board has shown that it is making a good faith

effort toward integration and should have a reasonable length of time

to solve its problems and end segregation in the Mansfield Second

School District. At this time this suit is precipitate and without

equitable justification." Jackson v. Rawden, 135 F. Supp. 936.

6

constitutional rights of plaintiffs to have the school

board, acting promptly, and completely uninfluenced

by private and public opinion as to the desirability

of desegregation in the community, proceed with

deliberate speed consistent with administration to

abolish segregation in Mansfield’s only high school

and to put into effect desegregation there.”

In the instant case the appellees have proceeded with

a study of twelve areas 3 which they allege embrace the

problems inherent in the desegregation of its school sys

tem. Of these twelve studies six had not been completed

at the time of trial,4 and the policy of the Board of Edu

cation is to maintain a segregated school system until these

studies have been completed and plans worked out to the

minutest detail (R. 94).

The areas of study which have been completed allegedly

involve various problems related to the administration of

nonsegregated schools. Although reports of the results

had been submitted to the Board (R. 109), the school

authorities have not formulated a plan to admit appellants

to the public schools on a nondiscriminatory basis and

contend that additional time is necessary to study prob

lems in other areas.

Since the burden rests upon the school authorities to

establish that additional time is necessary to carry out the

ruling of the Supreme Court, Brown v. Board of Educa

tion, supra, they had the burden of showing that the areas

of study to be completed were within the contemplation of

the Supreme Court as justification for delay. The appel

lees did not carry this burden but merely asserted that,

“ it will be impractical to attempt integration until the

studies have been completed” (R. 84); that, “ for the im

mediate future this Board feels that any change is prema-

3 See footnote 1, supra.

4 Id.

7

ture” (R. 90); and, that “ the information gained from

these analyses is indispensable for future planning” (R.

91). The appellants contend that the areas of study which

have not been completed 5 do not fall within the “ prob

lems ’ ’ which the court may consider 6 but are concerned

with public and private considerations which are not

grounds for delay. Brown v. Board of Education, supra,

Jackson v. Rawden, supra, Mitchell v. Pollock, Civil Action

No. 708 (W. D. Ky., Feb. 1957) unreported; Garnett v.

Oakley, Civil Action No. 721 (W. I). Ky., Feb. 1957) un

reported.

But, even if the remaining studies were found to be

of an administrative nature, a consideration of these prob

lems for this period of time 7 without taking some posi

tive action in the way of discontinuing segregation does

not constitute “ a prompt and reasonable start” toward

that objective. McSwain v. County Board of Education,

138 F. Supp. 570 (1956). In Willis v. Walker, 136 F.

Supp. 177, 181 (1955) where the plans for desegregation

were “ rather vague and indefinite and depended for their

ultimate success upon so many varied elements” , it was

said that, “ the court does not question the good faith of

the defendants but good faith alone is not the test. There

must be compliance at the earliest practicable date. ’ ’ Simi

larly, in The. School Board of the City of Charlottesville v.

Doris Marie Allen, 240 F. 2d 59 (4th Cir. 1957), cert.

5 See footnote 1, supra.

6 “ * * * the courts may consider problems related to administra

tion, arising from the physical condition of the school plant, the school

transportation system, personnel, revision of school districts and

attendance areas * * *, and revision of local laws and regulations. * * *

They will also consider the adequacy of any plans * * * to meet these

problems. * * *” Brown v. Board of Education. 349 U. S. 294,

300-301.

7 “ * * * this Board of Education months ago instructed Dr. W. T.

White * * * to proceed with a detailed study of the problems inherent

to desegregating a major school system. * * * ” (Emphasis added.)

Minutes of the Board of Education July 13, 1955 (R. 93).

8

denied, — U. S. —, 1 L. ed. 2d 664, the Court of Appeals

for the 4th Circuit said at page 64:

“ It had been two years since the first decision of

the Supreme Court in Brown v. Board of Education

and, despite repeated demands upon them, the

boards of education had taken no steps towards re

moving the requirement of segregation in the schools

which the Supreme Court had held violative of the

constitutional rights of the plaintiffs. This was not

“ deliberate speed” in complying with the law . . .

but was clear manifestation of an attitude of in

transigence which justified the issuance of the injunc

tions to dispel the misapprehension of school authori

ties as to their obligations under the law and to bring

about their prompt compliance with constitutional

requirements as interpreted by the Supreme Court.”

II. The Court Below Erred In Dismissing The Suit.

The court’s dismissal of the suit was not supported by

the evidence adduced at the trial and was contrary to pre

vailing authority.

The assertion of the court below that “ the state statute

requires separate schools for colored and white students”

(E. 131) is clearly erroneous. McKinney v. Blankenship,

154 Tex. 632, 282 S. W. 2d 691. Equally erroneous is the

attempt on the part of the court below to revive the doc

trine of “ separate but equal” (R. 130-131) to sustain the

view that appellants are not being denied a constitutional

right, Brown v. Board of Education, 347 U. 8. 483. In

deed, where facilities are “ equal” the administrative prob

lems are minimal, and there is little or no reason for

deferring desegregation.

The record shows that, although some of the school

buildings are completely filled, there are others which are

not. (R. 110.) This indicates that the school facilities are

9

adequate to house the total student population. If, how

ever, a crowded condition were to exist in some buildings,

this would not justify continued segregation. Clemons v.

Board of Education, 228 F. 2d 853 (6th Cir. 1956); Willis

v. Walker, swpra.

The change from a segregated school system to one that

is nonsegregated will require the revision of school districts

to achieve a system of determining admission on a non-

racial basis. A study of the scholastic boundaries of indi

vidual schools has been completed.8 The assignment of

students pursuant to revised districts would require the

transfer of some of them to schools in new attendance

areas. Such reassignment, however, would be a natural

result of the redistricting; and, contrary to the opinion of

the court below (R. 132), does not amount to an unthinkable

and unbearable wrong because some white students may

have to be assigned elsewhere in order to accommodate the

Negro students in the new district.

The judgment of the District Court is contrary to the

rules of equity and constitutes an improvident exercise of

judicial power. Brown v. Board of Education, 347 U. S.

483; Clemons v. Board of Education, supra; Jackson v.

Rawden, supra; Whitmore v. Stillwell, 227 F. 2d 187 (5th

Cir. 1955).

A trial court abuses its discretion when it fails or re

fuses properly to apply the law to conceded or undisputed

facts. Union Tool Go. v. Wilson, 259 IT. S. 107. In a suit

of this kind where admission to public schools is being-

denied plaintiffs solely on the basis of race, they have an

absolute right to have their constitutional rights declared.

Brown v. Board of Education, 349 IT. S. 294; Jackson v.

Rawden, supra; cf. Witmore v. Stillwell, supra; Alfred

Avery, Jr. v. Wichita Falls Independent School District

et al., 241 F. 2d 230 (5th Cir. 1957), cert, denied, — U. S. —,

April 22, 1957.

See footnote 1, supra.

10

The undisputed evidence plainly shows that the board

has not given serious consideration to its paramount duty

to proceed with integration “ with all deliberate speed”

but, quite to the contrary, has taken definite action to con

tinue segregation indefinitely. Indeed, it has declined to fix

or even give serious consideration to the time when it would

cease, and the only reason it has given for not desegregat

ing at once is the need of more time for studies. The failure

of the defendants to proceed “ with all deliberate speed”

toward desegregation brings the instant case squarely

within the holding of this court in Jackson v. Raivden,

supra. This is especially true in the light of the previous

decision of this court in the instant case. Brown v. Rippy,

233 F. 2d 796. In light of the history of this case, appel

lants’ only effective redress, it is respectfully submitted, is

an order of this Court instructing the District Court to issue

the injunction as prayed.

Conclusion

Wherefore, appellants pray that the judgment below be

reversed and that the court below be instructed to enter an

order requiring appellees to desegregate the schools under

their jurisdiction “ with all deliberate speed.”

Respectfully submitted,

Louis B edford,

C. B. B unkley, J r.,

W. J. D urham,

U. S impson T ate,

Dallas, Texas,

R obert L. Carter,

New York City,

Attorneys for Appellants.