Hunter v. City of Los Angeles Corrected Brief for Plaintiffs-Appellees

Public Court Documents

June 16, 1993

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Hunter v. City of Los Angeles Corrected Brief for Plaintiffs-Appellees, 1993. 608fe8b5-b89a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/3c38b1f1-353e-4815-a531-3f9d7a91cfa9/hunter-v-city-of-los-angeles-corrected-brief-for-plaintiffs-appellees. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

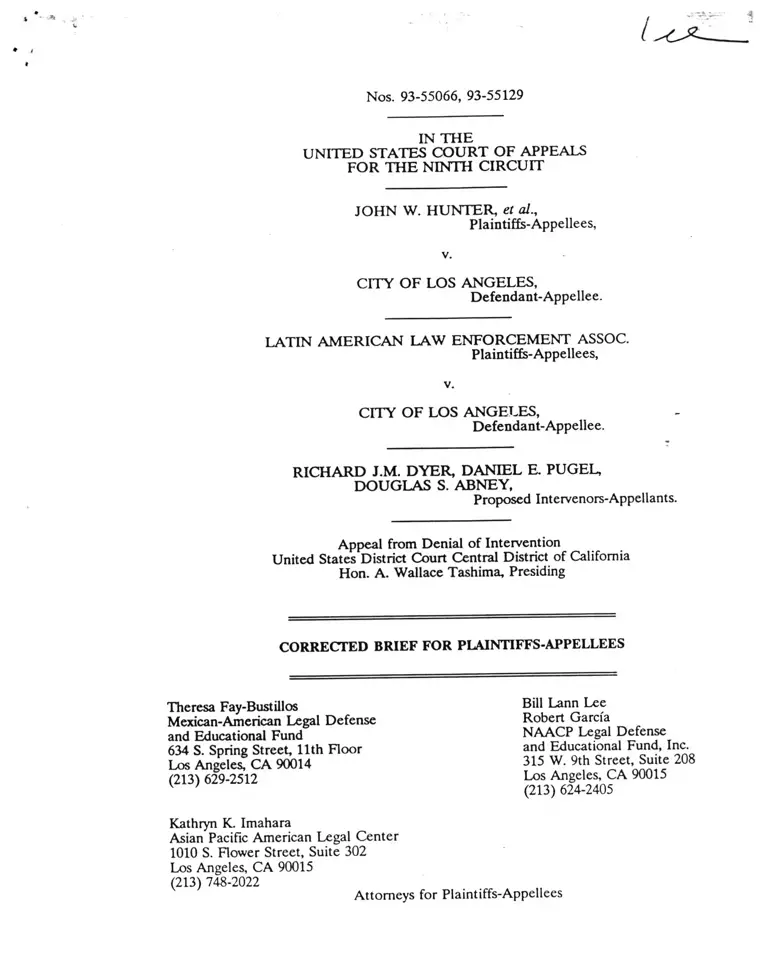

Nos. 93-55066, 93-55129

IN T H E

U N ITED STATES C O U R T O F APPEALS

FO R T H E NINTH CIRCU IT

JO H N W. H U N TER, et al.,

Plaintiffs-Appellees,

v.

CITY O F LOS ANGELES,

Defendant-Appellee.

LATIN AM ERICAN LAW ENFORCEM ENT ASSOC.

Plaintiffs-Appellees,

CITY O F LOS ANGELES,

Defendant-Appellee.

RICHARD J.M. DY ER, DA N IEL E. PUGEL,

DOUGLAS S. ABNEY,

Proposed Intervenors-Appellants.

Appeal from Denial of Intervention

United States District Court Central District of California

Hon. A. Wallace Tashima, Presiding

CORRECTED BRIEF FOR PLAINTIFFS-APPELLEES

Kathryn K. Imahara

Asian Pacific American Legal Center

1010 S. Flower Street, Suite 302

Los Angeles, CA 90015

(213) 748-2022

v.

Theresa Fay-Bustillos

Mexican-American Legal Defense

and Educational Fund

634 S. Spring Street, 11th Floor

Los Angeles, CA 90014

(213) 629-2512

Bill Lann Lee

Robert Garcia

NAACP Legal Defense

and Educational Fund, Inc.

315 W. 9th Street, Suite 208

Los Angeles, CA 90015

(213) 624-2405

Attorneys for Plaintiffs-Appellees

Nos. 93-55066, 93-55129

IN THE

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR TH E NINTH CIRCUIT

JOHN W. HUNTER, et al.L W * M i . j

Plaintiffs-Appellees,

v.

CITY OF LOS ANGELES,

Defendant-Appellee.

LATIN AMERICAN LAW ENFORCEMENT ASSOC.

Plaintiffs-Appellees,

CITY OF LOS ANGELES,

Defendant-Appellee.

RICHARD JM . DYER, DANIEL E. PUGEL,

DOUGLAS S. ABNEY,

Proposed Intervenors-Appellants.

Appeal from Denial of Intervention

United States District Court Central District of California

Hon. A. Wallace Tashima, Presiding

CORRECTED BRIEF FOR PLAINTTFFS-APPELLEES

Kathryn K. Imahara

Asian Pacific American Legal Center

1010 S. Flower Street, Suite 302

Los Angeles, CA 90015

(213) 748-2022

v.

Theresa Fay-Bustillos

Mexican-American Legal Defense

and Educational Fund

634 S. Spring Street, 11th Floor

Los Angeles, CA 90014

(213) 629-2512

Bill Lann Lee

Robert Garcia

NAACP Legal Defense

and Educational Fund, Inc.

315 W. 9th Street, Suite 208

Los Angeles, CA 90015

(213) 624-2405

Attorneys for Plaintiffs-Appellees

VII. CONCLUSION............................................................................................................... 26

STATEMENT OF RELATED CASES ................................................................................. 27

ATTORNEYS F E E S ................................................................................................................. 27

ii

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

Cases: Pages:

Aetna Life Ins. Co., v. Haworth,

300 U.S. 227, 57 S.Ct. 461, 811 L.Ed.2d 617 (1937)................................................... 25

Alaniz v. Tillie Lewis Foods,

572 F.2d 657 (9th Cir.), cert denied, 439 U.S. 837,

99 S.Ct. 123, 58 L.Ed.2d 134 (1 9 7 8 ).............................................................. 8-11, 14-17

Anderson v. City of Bessemer City,

470 U.S. 564, 105 S.Ct. 1504, 84 L.Ed.2d 518 (1985).............................................. 6, 25

Arizona v. California,

460 U.S. 605, 103 S.Ct. 1382, 75 L.Ed.2d 318 (1983)............................................ 22, 23

Buckley v. Valeo,

424 U.S. 11, 96 S.Ct. 612, 46 L.Ed.2d 659 (1976) ..................................................... 25

County of Fresno v. Andrus,

622 F.2d 436 (9th Cir. 1980) ......................................................................................7 18

County of Orange v. Air California,

799 F.3d 535 (9th Cir. 1986), cert denied,

480 U.S. 946, 107 S.Ct. 1605, 94 L.Ed.2d 791 (1987).............................. 6-9, 11, 13, 15

Doherty v. Rutgers School of Law-Newark,

651 F.2d 893 (3d Cir. 1 9 8 1 ).......................................................................................... 13

Donaldson v. United States,

400 U.S. 517, 91 S.Ct. 534, 27 L.Ed 2d 580 (1971) ................................ 17, 18, 20, 21

EEOC v. Pan American World Airways, Inc.,

897 F.2d 1499 (1990), U.S. cert denied, 498 U.S. 815,

111 S.Ct. 55 (1990) ............................................................................................... 7, 23-25

Farwest Steel Corp. v. Barge Sen-Span 241,

769 F.2d 620 (9th Cir. 1985) ........................................................................................ 24

Howard v. McLucas,

782 F.2d 956 (11th Cir. 1986)........................................................................................ 19

Howard v. McLucas,

871 F.3d 1000 (11th Cir. 1989)...................................................................................... 19

In re Birmingham Reverse Discrimination

Employment Litigation,

833 F.2d 1492 (11th Cir. 1987), U.S. rehearing denied,

492 U.S. 932, 110 S.C. 11, 106 L.Ed 628 (1989) ....................................................... 20

iii

Pages:

Yniquez v. Moffard, 130 F.R.D. 410 (D. Ariz. 1990), affd in part,

rev’d in part, 939 F.2d 727 (9th Cir. 1991)..................................................................... 9

Statutes: Pages:

28 U.S.C. § 1291 ................................................................................. 7 ................................. 2, 5

28 U.S.C. § 1343 ..................................................... 1

42 U.S.C. § 2000e........................................................................................................................ 19

42 U.S.C. § 2000e-2(n)............................................................................................................... 21

42 U.S.C. § 2000e-2(n)(l).......................................................................................................... 23

432 U.S. at 395-96 ...................................................................................................................... 10

Fed. R. Civ. P. 5 2 ....................................................................................................................... 6

Fed.R.Civ. P. 24(a)(2) ................................................................................................................. 2

42 U.S.C. § 2000e........................................................................................................................ 19

42 U.S.C. § 2000e-2(n)............................................................................................................... 21

42 U.S.C. § 2000e-2(n)(l).......................................................................................................... 23

Fed.R.Civ. P. 24(a)(2) ................................................................................................................. 2

FRCP Rule 2 4 ............................................................................................................................ 11

v

Nos. 93-55066, 93-55129

IN THE

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE NINTH CIRCUIT

JOHN W. HUNTER, et al.,

Plaintiffs-Appellees,

v. —

CITY OF LOS ANGELES,

Defendant-Appellee.

LATIN AMERICAN LAW ENFORCEMENT ASSOC.

Plaintiffs-Appellees,

v.

CITY OF LOS ANGELES,

Defendant-Appellee.

RICHARD JM . DYER, DANIEL E. PUGEL,

DOUGLAS S. ABNEY,

Proposed Intervenors-Appellants.

Appeal from Denial of Intervention

United States District Court Central District of California

Hon. A. Wallace Tashima, Presiding

CORRECTED BRIEF FOR PLAINTIFFS-APPELLEES

I.

STATEMENT OF JURISDICTION

The district court had subject matter jurisdiction pursuant to 28 U.S.C. § 1343 of this

employment discrimination class action brought by minority police officers. A final judgment

was entered on August 27, 1992, approving a consent decree. Supp. 71-73. The time to appeal

1

the approval of the consent decree ran on September 26,1992. The proposed intervenor white

officers did not file a motion to intervene until after the time to appeal had elapsed.

The instant appeal seeks review of the denial of a motion to intervene as of right

pursuant to Fed.R.Civ. P. 24(a)(2) that was originally filed on October 9, 1992, by the three

white officers, after the time to appeal the consent decree had elapsed. The motion was denied

by an order issued November 18,1992. Supp. 121. Notices of appeal were filed on December

17, 1992. Supp. 123-26. The appeal is proper under 28 U.S.C. § 1291 as an appeal from the

final order denying intervention.

II.

ISSUES PRESENTED FOR REVIEW

A. Whether the district court abused its discretion in denying as untimely a motion to

intervene as of right?

B. Whether the district court correctly denied a motion to intervene as of right because the

proposed intervenors have no direct, significant protectable interest in the outcome of the

litigation, any interest of proposed intervenors will not be impaired or impeded, and any

interest of proposed intervenors has been adequately represented by their own past

participation in prior proceedings as amici curiae?

C. Whether the district court’s findings that the proposed intervenors were accorded actual

notice and an opportunity to be heard concerning the underlying Consent Decree were clearly

erroneous?

III.

STATEMENT OF THE CASE

A. Prior Proceedings.

The underlying employment discrimination class action lawsuit was initiated on

September 12, 1988, with the filing of an administrative complaint of employment

discrimination by an organization of Latino Los Angeles Police Department ("LAPD") officers,

the Latin American Law Enforcement Association, and on October 11, 1988, with the filing of

2

a similar administrative complaint by an African-American LAPD officer, John W. Hunter, with

the California State Department of Fair Employment and Housing ("DFEH"). Supp. 19-31.

The substantially similar complaints alleged that minority LAPD officers were denied civil

service promotions, assignments to desirable mobility-enhancing positions, paygrade

advancements within those positions, and assignments to desirable mobility-enhancing positions

by the City of Los Angeles ("the City"). The DFEH certified the two complaints as class

actions on behalf of African-American and Latino LAPD officers. Supp., at pp. 20-31. In

December 1990 and January 1991, DFEH issued lengthy accusations in both cases finding

probable cause that minority officers had been subject to discrimination in promotions,

advancements and assignments based upon unrebutted statistical analyses and information

gathered during an extensive administrative investigation. Supp. 21-25, 32-36.

The minority officers and the City then entered into settlement negotiations.

Declaration of Theresa Fay-Bustillos at 18 in support of Plaintiffs’ Opposition to Amicus Curiae

Brief, filed July 27,1992 ("Declaration of Fay-Bustillos"). During the negotiations, the Korean

American Law Enforcement Association filed an administrative charge and joined the

negotiations on behalf of Asian-American LAPD officers. Plaintiffs’ Memorandum In Support

Of Proposed Consent Decree at 2. A settlement in the form of a proposed Consent Decree

was reached in late 1991. Declaration of Fay-Bustillos at 18. The proposed Consent Decree

was approved by the City Council on November 5, 1991. Id.

The administrative proceedings and the provisions of the proposed Consent Decree were

the subject of extensive media coverage. See, e.g., "LAPD Holds Back Black Officers, State

Says," LA . Times, Jan. 24,1991, at Bl; "Minority Officers Hail Bias Accord," L A . Times, Nov.

7, 1991, at Bl, Supp. 112-14. After the City Council approved the proposed Decree, the Los

Angeles Police Protective League, the collective bargaining agent for all LAPD officers,

published and distributed to its members a bulletin entitled "Proposed Consent Decree and

Agreement Resolving Litigation re Police Department Promotions, Paygrade Advancements,

and Assignments to Coveted Positions," dated December 24, 1991. The bulletin contained a

3

four-and-a-half page single-spaced summary of the proposed Decree. Supp. 115-20.

On March 27,1992, the minority officers filed two judicial complaints against defendant

City along with the proposed Decree. The district court, Hon. A. Wallace Tashima, presiding,

on April 6, 1992, consolidated the two cases, certified the class of minority officers, authorized

notice of the proposed settlement to the class and set a fairness hearing. Supp. 1-12. The

district court modified the order on April 15, 1992, making minor revisions to some of the

notice procedures and setting a new fairness hearing for July 13, 1992. Supp. 13-15.

At the fairness hearing, three white LAPD officers, Richard J.M. Dyer, Daniel E. Pugel,

and Douglas S. Abney, ("white officers") submitted an "Amicus Curiae Brief Opposing

Confirmation of Consent Decree and Agreement" on behalf of white LAPD officers. Supp. 53.

("July 13,1992, amicus brief'). The brief stated that the three officers ”ha[d] not made a formal

motion to intervene . . . as the likelihood of prevailing on FRCP Rule 24 action at this date

would be very unlikely." Supp. 55. The brief then made numerous arguments that the

provisions of the Consent Decree were unconstitutional and unfair to white officers. Id. In

order to consider the claims made by the white officers, the district court continued the fairness

hearing until August 10,1992, permitting the parties to respond and the white officers to reply.

Supp. 72. The white officers’ two briefs opposing approval of the Decree total 53 pages,

exclusive of exhibits.

At the continued fairness hearing, the white officers’ counsel made extensive oral

arguments. Supp. 57-70. When the district court judge stated that he would approve the

Consent Decree, the white officers’ counsel indicated that he intended to file a motion to

intervene as of right and requested a special hearing date. Supp. 69. The district court denied

the request. Supp. 69. Pursuant to C.D. Cal. Local Rules 7.2 and 7.4, a motion is heard

without special setting the first Monday, 21 days after the filing of the motion.

4

On August 27, 1992, the district court entered a Judgment and Order Approving

Consent Decree and Agreement. Supp. 71-73. In response to the white officers’ argument

that the term of the Decree was too long, the Court amended the fixed term of 12 to 15 years

to a maximum term of 15 years subject to the right of defendant City of Los Angeles to move

at any time to be relieved of its obligations upon a showing that the Decree’s objectives had

been accomplished. Supp. 65-67, 92. Otherwise the district court approved the Consent

Decree presented by the minority officers and the City.

The time to appeal the Consent Decree expired on September 26, 1992, see

28 U.S.C. § 1291, without the white officers filing an intervention motion or an appeal.

B. The Proposed Intervention.

On October 16, 1992 — 50 days after entry of judgment — the three white officers filed

a motion for intervention as of right pursuant to Fed. R. Civ. P. 24(a)(2) along with a

supporting memorandum, a proposed complaint-in-intervention and a declaration by proposed

intervenor Pugel.

As of the date of the intervention, it was too late to challenge the Consent Decree on

its face. No issues concerning implementation of the Decree were before the Court. None of

the proposed intervenors’ papers complain of any specific post-judgement act or conduct that

has adversely affected them or any other white officer.

C. The Decision Below.

The district court denied the motion to intervene on November 18,1992, on all grounds,

making specific findings that the motion was untimely.

The proposed intervenors had notice of this action well before the date

initially set for approval of the class settlement. They appeared at that hearing

and were granted amici status, permitted to file a brief in opposition to the

proposed settlement and the hearing was continued so that their objections could

be considered and responded to by the parties. That amici and proposed

intervenors were well acquainted with the issues is demonstrated by the lengthy

briefs they filed. The court adopted one of the changes requested by amici.

They never moved for intervention before the judgment was entered.

5

The final Judgment and Order Approving Consent Decree and

Agreement was entered on August 28, 1992, more than two months ago.

Proposed intervenors were aware of this because they were present at the final

hearing when the consent decree was approved. Having waited this long, until

after the time to appeal from the judgment has long expired, the proposed

complaint in intervention is nothing less than a bald collateral attack on the

judgment. The motion for intervention is not timely.

Supp. 122.

IV.

STANDARDS OF REVIEW

In assessing whether a motion for intervention as of right was properly denied as

untimely, the Court uses an abuse of discretion standard. NAACP v. New York, 413 U.S. 345,

366, 93 S.Ct. 2591, 37 L.Ed.2d 648 (1973) (Timeliness "is to be determined by the court in the

exercise of its sound discretion; unless that discretion is abused, the court’s ruling will not be

disturbed on review"); United States v. Covington Technologies, 967 F.2d 1391, 1394 (9th Cir.

1992); County o f Orange v. Air California, 799 F3d 535, 537 (9th Cir. 1986), cert denied, 480

U.S. 946, 107 S.Ct. 1605, 94 L.Ed3d 791 (1987).

In assessing whether the motion for intervention of right was otherwise properly denied,

the Court conducts a de novo review. Covington Technologies, 967 F.2d at 1394; Air California,

799 F.2d at 537.

In assessing whether the district court correctly found that proposed intervenors had

been accorded actual notice and an opportunity to be heard, the Court uses the clearly

erroneous rule of Fed. R. Civ. P. 52. Anderson v. City o f Bessemer City, 470 U.S. 564, 573-74,

105 S.Q. 1504, 84 L.Ed.2d 518 (1985).

V.

SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT

The district court did not abuse its discretion in finding that the motion for intervention

as of right was untimely filed. A post-judgment motion to intervene by the white officers was

not filed within the time allowed for the filing of an appeal notwithstanding the "‘general rule

that a post-judgment motion to intervene is timely if filed within the time allowed for the filing

6

of an appeal.’" Covington Technologies, 967 F.2d at 1394, quoting Yniquez v. Arizona, 939 F.2d

727, 734 (9th Cir. 1991). The lower court correctly denied the motion to intervene as untimely.

The Court should dismiss the appeal or summarily affirm on the basis of untimeliness.

The record fully supports the determination of the Court below that proposed

intervenors have no direct, substantial protectable interest, that no impairment of any interest

will result, and that any interest has been adequately represented by proposed intervenors’ past

participation as amici curiae. The lower court therefore correctly determined that intervention

as of right should be denied on these grounds.

The district court correctly found that proposed intervenors had notice of the Consent

Decree and were given an opportunity to be heard. These findings are not clearly erroneous.

They are fully supported by the record. There was no violation of the Due Process Clauses of

the Fifth and Fourteenth Amendments, Mullane v. Central Hanover Bank & Trust Co., 339 U.S.

306, 314, 70 S.Ct. 652, 94 L.Ed. 865 (1950); EEOC v. Pan American World Airways, Inc., 897

F.2d 1499, 1507-08 (1990), U.S. cert denied, 498 U.S. 815, 111 S.Q. 55 (1990) or of Title VII

of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, as amended, 42 U.S.C. § 2000e-2(n)(l).

VI.

ARGUMENT

The Court has adopted the following four-part test to resolve applications for

intervention of right under Fed. R. Civ. P. 24(a)(2):

An order granting intervention as of right is appropriate if (1) the

applicant’s motion is timely; (2) the applicant has asserted an interest relating

to the property or transaction which is the subject of the action; (3) the applicant

is so situated that without intervention the disposition may, as a practical matter,

impair or impede its ability to protect that interest; and (4) the applicant’s

interest is not adequately represented by the existing parties.

Covington Technologies, 967 F.2d at 1394; Air California, 799 F.2d at 537. For the reasons set

forth below, the district court correctly applied these standards in the instant case.

7

A. The District Court Correctly Exercised Its Discretion in Finding the Motion to Intervene

Untimely.

1. The Appropriate Legal Standard.

In determining whether a motion to intervene is timely, the Court evaluates three factors

to determine whether the lower court abused its discretion.

(1) the stage of the proceeding at which an applicant seeks to intervene; (2) the

prejudice to other parties; and (3) the reason for and length-of the delay.

Covington Technologies, 967 F.2d at 1394; Air California, 799 F.2d at 537; Alaniz v. Tillie Lewis

Foods, 572 F.2d 657, 658 (9th Cir.), cert denied, 439 U.S. 837, 99 S.Ct. 123, 58 L.Ed.2d 134

(1978). The alternative standard proffered by the white officers (length of time applicant knew

or should have known of their interest in the litigation, extent of prejudice to existing parties

if the intervention is granted, extent of prejudice to the applicants if intervention is denied, and

existence of any unusual factors that would militate for or against intervention) is unsupported

by citation to any legal authority and finds limited support for only a portion of the standard

in either of the cases the white officers cite generally. Appellants’ Opening Brief at 9 ("white

officers’ brief'). See United States v. Oregon, 745 F.2d 550, 552 (9th Cir. 1984)(three factors:

stage of the proceedings, prejudice to other parties and reason for and length of the delay.);

Western Water District v. United States, 700 F.2d 561, 563 (9th Cir. 1983).

2. The Motion to Intervene Was Untimely Because It Was Filed at the Post-judgment

Stage o f the Proceedings and After the Time to Appeal Had Expired.

The general rule is that a bona fide post-judgment motion to intervene is timely only

if filed within the time allowed for the filing of an appeal. United Airlines, Inc. v. McDonald,

432 U.S. 385, 396, 97 S.Ct. 2464, 53 L.Ed. 2d 423 (1977); Covington Technologies, 967 F.2d at

1394; Yniquez v. Arizona, 939 F.2d 727, 734 (9th Cir. 1991).

"Although post-judgment motions to intervene are generally disfavored, post

judgment intervention for purposes of appeal may be appropriate if certain

requirements are met, the first of which is that the intervenors must act promptly

after entry of judgment . . . The second requirement is that the intervenors must

meet traditional standing criteria."

8

Covington Technologies, 967 F.2d at 1395, quoting Yniquez v. Moffard, 130 F.R.D. 410, 414 (D.

Ariz. 1990), tiff'd in pan, rev’d in pan, 939 F.2d 727 (9th Cir. 1991).

If the proposed intervenor had reason to intervene earlier, post-judgment intervention

is generally disfavored because it creates delay and prejudice to the existing parties and

undermines the orderly administration of justice, particularly after the existing parties have

entered into a settlement agreement. See Air California, 799 F.2d at 538; Alaniz, 572 F.2d at

658; Ragsdale v. Tumock, 941 F.2d 501, 504 (7th Cir. 1991); cert denied,___U.S.___ , 112 S.Ct.

879, 116 L.Ed.2d 784 (1992) ("Once parties have invested time and effort into settling a case

it would be prejudicial to allow intervention . . . [Intervention at this time would render

worthless all of the parties’ painstaking negotiations because negotiations would have to begin

again and [the proposed intervenor] would have to agree to any proposed consent decree . . .

A case may never be resolved if another person is allowed to intervene each time the parties

approach a resolution of it.") (citations omitted). Under this line of cases, the filing of a post

judgment motion within the time for appeal is irrelevant. See, e.g, Alaniz, 572 F.2d at 858

(motion filed 17 days after judgment untimely).

The white officers knew or should have known long before the entry of judgment that

their interest might be affected by the consent decree. Nothing new happened after the entry

of judgment that adversely affected the proposed intervenors or any other white officer. The

white officers’ intervention therefore should have been filed before the entry of judgment. The

intervention was not a bona fide post judgment motion. The district court did not abuse its

sound discretion in so ruling.

Even assuming arguendo that the white officers’ motion was a bona fide post-judgment

application, it was untimely because the white officers failed to file within the time allowed for

filing an appeal. The general rule is that a post-judgment motion must be filed within the time

to appeal. The white officers’ brief, p. 12, seeks to dispute the applicable objective standard,

arguing for a subjective test that "the relevant circumstance as to whether the Appellants are

timely is when they first became aware that its interest could be adversely affected and was not

9

being protected adequately by the existing parties," citing McDonald, 432 U.S. at 394.

McDonald says no such thing. McDonald concerned a class member who "quickly sought to

enter the litigation" after discovering that class representatives would no longer protect her

interests. Id. The Supreme Court clearly stated as follows:

The critical inquiry in every [post-judgment] case is whether in view of all the

circumstances the intervenor acted promptly after the entry of final judgment.

Cf. NAACP v. New York, 413 U.S. 345, 366, 37 L.Ed.2d 648, 93 S.Ct. 2591.

Here, the [proposed intervenor] filed her motion within the time period in which

the named plaintiffs could have taken an appeal.

432 U.S. at 395-96. This Court has repeatedly so ruled as well. Covington Technologies, 967

F.2d at 1394; Yniquez, 939 F.2d at 734. There is no basis for the white officers’ subjective

standard for intervention. Indeed, the law requires an objective standard. See NAACP v. New

York, 413 U.S. at 366 ("appellants knew or should have known . . . ); Alaniz, 572 F.2d at_657

(proposed intervenors "either knew or should have known . . .").

In any event, the white officers disingenuously misstate the record of their subjective

knowledge. Although they argue to this Court that they intervened only because they learned

at the August 10,1992, fairness hearing that the City would not represent their interests, white

officers’ brief at 12, that argument is inconsistent with their position below. The July 13, 1992,

amicus brief submitted to the district court indicates that they harbored such feelings long

before the fairness hearing. The amicus brief expressly argued that ”[t]he Consent Decree and

Agreement can not [sic] be approved as the interests o f non-minority officers o f the Los Angeles

Police Department have not been represented by the City" (Supp. 54 (original emphasis)), and

questioned whether the City "in any way adequately represented the non-minority officers’

interest" (id. at 56) and whether they and the City "shared any identity of interest at all" (id.).

The brief concluded that the "City’s interests were antagonistic" to those of white officers. Id.

The amicus brief demonstrates that the white officers’ characterization of their late

subjective knowledge about the need to intervene is a complete fabrication. The amicus brief

clearly reflected the white officers’ contemporaneous knowledge that any intervention would

be untimely as of July 1992, when the amicus brief was submitted.

10

The non-minority officers of the Los Angeles Police Department have not made

a formal motion to intervene under the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure, Rule

24, as the likelihood of prevailing on FRCP Rule 24 action at this date would be

very unlikely.

Supp. 55. (citations omitted).

The white officers’ do not raise a bona fide post-judgment intervention because they

knew or should have known of any need to intervene much earlier than the entry of final

judgment. Extensive and well-publicized negotiations or settlement-are enough to trigger the

need to intervene under the law of this Circuit. Air California, 799 F.2d at 538 (intervention

untimely when motion was made only after a well-publicized settlement). As this Court held

in Alaniz, 572 F.2d at 659, "The crux of [proposed intervenors’] argument is that they did not

know the settlement decree would be to their detriment. But surely they knew the risks. To

protect their interests, [proposed intervenors] should have joined the negotiation before the suit

was settled. ...[Proposed intervenors] have not proved fraudulent concealment. It is too late

to reopen this action." Indeed, the Korean American Law Enforcement Association, on behalf

of Asian-American officers, began to participate after settlement negotiations were underway

between the Latino and African American plaintiffs and the City. Plaintiffs’ Memorandum in

Support of Proposed Consent Decree at 2. They recognized the significance of the issues for

Asian American officers. Unlike the white officers, they took the necessary steps in a timely

manner to participate.

In the instant case, the undisputed record demonstrates that the settlement reached in

administrative proceedings was extensively publicized in November and December of 1991

through newspaper coverage and the distribution by the Los Angeles Police Protective League

of a summary of the settlement agreement. A Los Angeles Times article, published after the

DFEH’s accusations were released, describes "’the pervasive and blatant pattern of

discrimination against minorities in the LAPD’." Supp. 112. According to that article, the

DFEH "wants the Police Department to revise its system of testing officers for promotion and

to follow affirmative action requirements in the way qualified candidates are selected for

11

promotion." Id. An article from the same paper, published after the City agreed to the

settlement, quotes one of plaintiffs’ counsel as follows: "‘The purpose of the settlement is to

build a promotion system at the department that is based on merit and open access to all

officers rather than to favoritism that favors Anglo officers."’ Supp. 114. The Police Protective

League, in consultation with its lawyers, provided its members a summary of the provisions of

the settlement, and explained that the settlement would be effectuated through a Consent

Decree. Supp. 115-20. The Police Protective League also put its membership on notice that

it would take a neutral position on the Decree:

"[BJecause the League must fairly represent all of its members without regard for

their sex, race, religious or national origin, the league cannot concur, oppose or

participate in the proposed Consent Decree and Agreement."

Supp. 115. The only white officer to submit a declaration, Mr. Pugel, stated that he was a

Protective League member. Supp. 105. The white officers, in short, knew or should have

known as of the beginning of 1992 that they should intervene in the administrative proceedings,

or as soon as the judicial action was filed in March 1992 to protect their interests. Yet they

delayed and did not seek to intervene for another ten and a half months.

Mr. Pugel swears in his declaration are that he was first "made aware" of the Consent

Decree in mid-May 1992, and that he "had an opportunity to review the twenty-five page

Consent decree on or about the end of May, 1992" at his LAPD station house. Supp. 104.

By his own admission, Mr. Pugel knew or should have known that he should intervene to

protect his purported interest in May 1992. Yet a month and a half went by before the white

officers filed their amicus brief, and four and a half months passed before they sought

intervention.

The white officers’ brief, p. 10, claims that they "have only known of their interest in the

litigation for a short period of time" and that the City "settled the case quietly and quickly

without alerting the non-minority officers". These unsupported statements are plainly

contradicted by the undisputed record of widespread publicity as of January 1992, and by Mr.

Pugel’s admission of having read the Consent decree in May 1992. Supp. 104, 112-20.

12

The white officers’ brief, p. 10, also argues, without a shred of factual support, that the

City failed to "consult" the white officers because of "heightened political and racial tensions

in Los Angeles," p. 10, that the City failed to adequately notify the Police Protective League

about the terms and ramifications of the Consent Decree, p. 11; that white officers had no

access to the Decree, id.; that the Protective League failed to "undertake a due diligence [sic]

investigation," id. These statements cannot be squared with the Pugel declaration or the

Protective League summary.

The white officers’ brief, pp. 10-11, argues that the fairness hearing notices were directed

only at minority LAPD officers, conveniently ignoring that the notices were posted at station

house bulletin boards for all officers to see, and read at successive roll calls for all officers to

hear. Indeed, Mr. Pugel admits that he personally "reviewed" a copy of the Consent Decree

posted at his station house. Supp. 104.

Finally, with respect to whether the white officers meet "traditional standing criteria" of

the post-judgment stage of proceeding inquiiy, Covington Technologies, 967 F.2d at 1394, none

assert a particularized claim of personal injury as a result of being denied either a promotion,

paygrade advancement or coveted assignment for which he was eligible through operation of

the Consent Decree. Standing to sue is absent. See, e.g., Doherty v. Rutgers School o f Law-

Newark, 651 F.2d 893, 899-900 (3d Cir. 1981). See also infra at 19-20.

3. Extreme Prejudice to the Existing Parties Would Result from Untimely Intervention.

After the post-judgment stage of proceedings, the Court considers prejudice to other

parties in order to assess timeliness. Serious prejudice has been found by this Court where

intervention would seriously disrupt a complex settlement that provides relief for long-standing

inequities. United States v. Oregon, 913 F.2d 576, 588-89 (9th Cir. 1990) ("the possibility of this

settlement unraveling is so prejudicial that to allow [intervention] at this late date would be

tantamount to disaster"), cert denied,_____U.S.____ , 111 S.Ct. 2889,115 L.Ed.2d 1054 (1991);

Air California, 799 F.2d at 538 (serious prejudice "‘results when relief from long-standing

inequities is delayed’" and from undoing of settlement after five years of protracted litigation);

13

Alaniz, 572 F.2d at 659 (serious prejudice results when "the decree is already being fulfilled; to

countermand it now would create havoc and postpone the needed relief).

In the instant case, the Consent Decree derives from administrative complaints of

classwide discrimination originally filed in September and October 1988, almost four years ago.

Accusations issued by the DEFH found probable cause to believe that pervasive discrimination

hobbled the advancement of minority officers into supervisory and initial level management

positions on the basis of extensive statistical disparities. Supp. 21-25, 32-26. For instance, the

following chart, based on data in the accusations, depicts the discriminatory impact of

promotional examinations under which white officers received promotions at much greater rates

than qualified minority applicants. Memorandum in Support of Proposed Consent Decree, at

4.

Examination Percentage Selection Rates

White Minority

Detective 1983 38.8 10.9

1985 24.9 12.6

1987 26.9 15.7

Sergeant 1984 16.1 10.5

1986 20.1 7.6

1989 26.9 193

Lieutenant 1987 23.5 15.2

The Decree, on its face, is a complex settlement of systemic allegations of discrimination in

LAPD sergeant, detective and lieutenant promotions, paygrade advancements and coveted

positions. The decree provides for goals, for changes in numerous personnel practices, and

monetary relief. Supp. 85-96. It has been in effect since September 1992.

The Decree also effectuates the recommendations of the Report of the Independent

Commission on the Los Angeles Police Department, known as the "Christopher Commission

Report," Supp. 44-52, which studied the operations of the LAPD in the wake of the Rodney

King beating. The Christopher Commission recommended that minority officers "be given full

and equal opportunity to assume leadership positions in the LAPD" (Supp. 49) and that

"minorities must be assigned on a nondiscriminatory basis to the so-called ‘coveted positions’

14

and promoted to supervisory and managerial positions on the same basis" as white officers,

(id.), noting that "‘if minority groups are to feel that they are not policed entirely by a white

police force they must see that [African-American] or other minority officers participate in

policy making and other crucial decisions’." Id. at 47, quoting President’s Commission on Law

Enforcement and the Administration o f Justice, Task Force Report (1967).

Permitting white officers at this late stage in the proceedings to challenge approval of

the settlement, given their across the board objections to the Consent Decree, which were

previously raised and considered by the district court, would impose extreme prejudice on

minority plaintiffs. Such a challenge would not only undo the lengthy negotiations which

resulted in the Consent Decree, but would also delay ongoing relief for long-standing

discriminatory patterns at the LAPD to the detriment not only of minority officers but minority

communities and the City of Los Angeles as a whole.

The white officers’ brief, p. 14, cites purported prejudice to their interests. Such

prejudice is not a criterion under the law of the Circuit. Eg., Covington Technologies, 967 F.2d

at 1394; Air California, 799 F.2d at 537. Moreover, their concerns are premature at best, no

white officer actually having complained of being denied a position or assignment because of

the operation of the Decree. The white officers’ brief, at p. 14, also claims that the City would

be prejudiced by the denial of intervention because it would be forced to defend "hundreds" of

reverse discrimination suits. Such a claim is hypothetical, has no factual support in the record

( no such claims having been filed to date) and is contrary to the evidence that only three white

officers have come forward to object to the Consent Decree.

4. The White Officers C annot"Convincingly Explain” Their Delay.

The third timeliness criteria is the reason for and length of the delay. The court stated

the heavy burden on a proposed intervenor to "convincingly explain its delay" when a district

court, as here, has exercised its discretion to find untimeliness. Air California, 799 F.2d at 538;

Alaniz, 572 F.2d at 659. In Air California, the Court rejected the claim that the City of Irvine

could wait to intervene until after reading the settlement decree because "Irvine should have

15

realized that the litigation might be resolved by negotiated settlement." Id. In Alaniz, 572 F.2d

at 659, the Court found that intervenors should have joined the negotiations of a settlement

rather than wait for the settlement to be completed.

In the instant case, the white employees delayed beyond the point when administrative

class actions were certified, the point of issuance of the DFEH accusations of probable cause

on classwide discrimination, the point of negotiation, the point of settlement, the point of filing

complaints in the trial court, all of which were well-publicized. They seek to explain their delay

because they only learned their interests were adversely affected by the defendant City’s

position at the fairness hearing. That, as we demonstrated above, is a fabrication. Even then,

the white employees cannot "convincingly explain" their continuing delay after the fairness

hearing. They delayed - with no explanation - yet another two months after the fairness

hearing before seeking to intervene, notwithstanding that in the interim the time to appeal the

merits of the Consent Decree expired. This lapse is even more inexplicable given the white

officers’ representation — demand for a hearing date for the motion for intervention — to the

district court at the fairness hearing that they would seek to intervene. Supp. 69.

The white officers’ brief argues that the passage of time alone is not dispositive, citing

United States v. Oregon, 745 F.2d at 552, where a delay of five years from the initiation of the

litigation was not detrimental. However, in Oregon, the intervenor "convincingly explained" that

the delay resulted from recent changed circumstances which affected intervenors for the first

time and created the possibility of new and expanded negotiations in a long-standing multiparty

dispute. See also Legal Aid Society o f Alameda County v. Dunlop, 618 F.2d 48, 50-51 (9th Cir.

1980) (change of circumstance resulting from a party’s change of position explained delay).

Here there were no changed circumstances and no new negotiations; the dispute concerns white

officers’ objections to the terms of a Consent Decree from which they can no longer appeal

because of their extensive delays in seeking intervention and failure to timely appeal. Contrary

to the white officers’ suggestion, the district court did not rely on the passage of time alone:

the lower court found that the delays were inexplicable: although they "were well acquainted

16

with the issues," the white officers "never moved for intervention before the judgment was

entered," and they then further delayed "until after the time to appeal from the judgment ha[d]

long expired." Supp. 122.

5. The Appeal Should Be Dismissed or the Order o f the Lower Court Summarily Affirmed

Because the Intervention was Untimely.

In Jenkins v. State o f Missouri, 967 F.2d 1245,1248 (8th Cir. 1992), cert denied by Clark

v. Jenkins, 113 S.Ct. 811,121 L.Ed.2d 684, 61 USLW 3433 (1992), the Eighth Circuit dismissed

an analogous appeal for lack of jurisdiction. Jenkins, a school desegregation case, concerned

an attempt by property owners within a school district to intervene to challenge an order raising

their property taxes. The Court held that "[i]n light of the . . . group’s failure to make a timely

motion to intervene and the consequent failure to file a timely notice of appeal," even ajate

order eventually granting intervention "cannot breathe life into rights already foregone^ 967

F.2d at 1247. The Eight Circuit noted that "[t]he chronology of events leading up to this appeal

is crucial to our holding." Id. Jenkins, of course, is a much closer case than the instant litigation

because the court below never granted intervention.

Alternatively, the Court may dispose of the appeal by summary affirmance because of

untimeliness without reaching the other Rule 24(a)(2) criteria. See, eg., Alaniz, 572 F.2d at 659

(per curiam affirmance of order denying intervention on lack of timeliness alone).

B. The White Officers Have Not Established "A Direct, Significant, Legally Protectable Interest

in the Transaction that is the Subject o f the Case.”

After consideration of timeliness, Fed.R.Civ.P. 24(a)(2) requires that the Court consider

whether would-be intervenors established "an interest relating to the property or transaction

which is the subject of the action." According to the Supreme Court, "[wjhat is obviously meant

[is that] there is a significantly protectable interest." Donaldson v. United States, 400 U.S. 517,

531, 91 S.Ct. 534, 27 L.Ed 2d 580 (1971). In Donaldson, the Court rejected a claim of sufficient

interest by a taxpayer in IRS enforcement proceedings to obtain business records concerning

the taxpayer’s financial transactions from an employer and the employer’s accountant because

17

any interest could be protected in separate proceedings. Id. ("And the taxpayer, to the extent

that he has such a protectable interest, as, for example, by way of privilege, or to the extent he

may claim abuse of process, may always assert that interest or that claim in due course at its

proper place in any subsequent trial."). The Court noted that "[w]ere we to hold otherwise, as

he would have us do, we would unwarrantedly cast doubt upon and stultify the Service’s every

investigatory move." Id.

In applying the Rule, as construed by Donaldson, this Court conducts an inquiry whether

proposed intervenors "possess the ‘direct, significant legally protectable interest in the property

or transaction required for intervention under Fed.R.Civ.P. 24(a)(2)’." Portland Audubon

Society v. Hodel, 866 F.2d 302, 309 (9th Cir. 1989) (rejecting as insufficient the economic

interest of an association of timber companies and independent contractors in a case brought

by environmental groups challenging a government sale for harvesting of old-growth fir timber

because their claim "has no relation to the interests intended to be protected by the

[environmental] statute at issue"). The Court explained that when the statute that is the subject

of the case provides no protection for the economic interest asserted, "[although the

intervenors have a significant economic stake in the outcome of the plaintiffs’ case, they have

pointed to no ‘protectable’ interest justifying intervention as of right." Id.; accord, Oregon

Environmental Council v. Oregon Department o f Environmental Quality, 775 F.Supp 353,358 (D.

Or. 1991). The Hodel Court noted, 866 F.2d at 309, that the "direct significant legally

protectable interest" test was consistent with the Court’s earlier ruling in Sagebrush Rebellion,

Inc, v. Watt, 713 F.3d 525, 526-28 (9th Cir. 1983), and County o f Fresno v. Andrus, 622 F.2d

436, 437-38 (9th Cir. 1980), because the proposed intervenors in those cases asserted interests

protected by the statutes at issue.

18

In the instant case, plaintiffs through the Consent Decree sought to vindicate the

protections of Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, as amended, 42 U.S.C. § 2000e, which

bars employment discrimination, inter alia, on the basis of race or national origin. The white

officers identify themselves as "non-minority LAPD sworn officers . . .[bjeing discriminatorily

denied employment opportunities by the operation of the discriminatory and illegal consent

decree," Complaint-in-Intervention 3, (Supp., 3) without any specification of how the Decree

has adversely affected their employment opportunities in any actual way. Thus, none of the

three white officers has alleged or can allege that he has actually been denied a promotion,

paygrade advance or coveted assignment because of the Decree. The white officers, in short,

contend only that the Decree is facially defective, a claim made and rejected by the district

court from which no timely appeal has been taken.

The white officers’ brief, at 15, cites Howard v. McLucas, 782 F.2d 956 (11th Cir._J986)

("Howard F), for the proposition that the white officers have a sufficient interest "because the

Consent Decree’s remedial provisions will adversely affect their rights.’" In Howard /, however,

white employees were found to have an interest in challenging the setting aside of "240 target

promotions" for black employees for which the white employees claimed to be eligible. 782

F2d at 959. In the instant case, the Consent Decree sets aside no positions or assignments for

minority employees, merely establishing flexible goals for qualified minority officers. Supp. 82-

83, 84-89. The Decree also specifically disclaims impairment of any collective bargaining rights

the white officers might have. Supp. 83. The white officers, as amici, presented the same

arguments they now mount to the remedial provisions of the Decree: their arguments, save

one, were rejected for good cause and that ruling is the law of the case, the white employees

not having filed a timely appeal from the approval of the Decree.

The Howard I, decision, moreover, was questioned by the Eleventh Circuit in a

subsequent opinion after the white employee intervenors were unable to show they were eligible

for any of the positions set aside for black employees. Howard v. McLucas, 871 F.3d 1000, 1005

(11th Cir. 1989) ("Howard IF) ("Employment, in and of itself, does not confer the right to

19

challenge an affirmative action plan. For example, in In re Birmingham Reverse Discrimination

Employment Litigation, 833 F.2d 1492 (11th Cir. 1987), U.S. rehearing denied, 492 U.S. 932, 110

S.C. 11, 106 L.Ed 628 (1989), an opinion that post dates our remand in this case, we held that

the claim that a consent decree resulted in reverse discrimination could not accrue until those

seeking redress were denied promotions. Id. at 1498-99.").

The interest asserted by the white officers is analogous to the interest of the taxpayer

found indirect and insubstantial in Donaldson, 400 U.S. at 531. It too should be asserted in due

course in separate proceedings after an actual case arises of an eligible white officer being

discriminatorily denied a promotion or assignment on account of the implementation of the

Decree. For instance, in United States v. City o f Chicago, 870 F.2d 1256, 1260 (7th Cir. 1989),

a case relied on in the white officers’ brief, at 17, white officers at the top of the lieutenant’s

promotion list were found to have a sufficient interest to challenge an order that racially altered

the prior promotion list. No such denial has occurred in the instant case. At this juncture, the

only conceivable interest the white officers can assert is the "purely economic" one found

insufficient in Portland Audubon Society: Title VII, like analogous environmental public law,

is concerned with the right to be free from discrimination, not with the generalized economic

impact of a valid remedial scheme. The white officers’ interest in safeguarding their economic

interest in the status quo at the LAPD is "not directly related to the litigation" for purposes of

Rule 24(a)(2). Oregon Environmental Council, 775 F.Supp. at 358 ("Plaintiffs do not attack the

validity of the individual permits under which the applicants for intervention operate. Rather,

plaintiffs seek an order requiring the [defendant] to comply with the Clean Air Act by enforcing

the terms of the implementation plan in issuing permits. Because the court finds that the

interests of the applicants for intervention in the outcome of this litigation is not directly

related to the litigation, any impairment of their economic interests is insufficient to give rise

to a right to intervene").

The white officers, therefore, have failed to establish a "direct, significant legally-

protectable interest," id., requiring intervention as of right.

20

C. No Impairment o f Any Interest o f the White Officers Results From the Approval o f the

Consent Decree.

An applicant for intervention must not only establish a direct, significant protectable

interest, but make the related showing that "disposition of the action may as a practical matter

impair or impede the applicant’s ability to protect their interest." Fed.R.Civ.P. 24(a)(2). As

noted above, Donaldson, 400 U.S. at 531, found no impairment or impediment when the

applicant "may always assert that interest or that claim in due course at its proper place in any

subsequent [litigation]."

In the instant case, the white officers’ brief, at 16-17, asserts that "approval and

implementation of the Consent Decree, will clearly impair the Non-minority Officers ability to

protect their interests because ‘factual and legal determinations’ regarding the Consent Decree’s

constitutionality will be made . . . [a]nd a judgment will allow the unconstitutional elements of

the consent decree to go into effect." The white officers conveniently ignore that their amicus

brief fully presented their claims of unconstitutionality, that their claims were rejected with one

exception by the court below, that they failed to file a timely intervention or notice of appeal

properly to raise the issue of the merits of the Decree in this Court, and that no issues

concerning implementation of the Decree that affect the white officers personally have arisen.

No impairment or impeding of the white officers’ ability to protect their interests, in short,

occurred. Any present discomfort of the white officers in the present posture of the case arises

from the fact that the arguments they now advance were rejected below for good cause and

they decided to acquiesce in that ruling, letting their right to appeal on the merits expire.

The white officers’ brief, at 24, also cites the 1991 amendments to Title VII, 42 U.S.C.

§ 2000e-2(n), which prevent post-judgment collateral attacks to a Consent Decree by those who

had prior notice and an opportunity to participate to establish that denial of intervention will

impair or impede their ability to protect any interest. Again, it is not the approval of the

Consent Decree that discomforts the white officers, but their acquiescence to the court’s

adverse ruling on their claims.

21

With respect to the district court’s findings, the white officers’ brief, 25, claims that they

did not receive "actual" notice of the fairness hearing or of facts indicating their need to

intervene because the fairness hearing notice "was not directed to the non-minority officers nor

were they apprised of the ramifications of the consent decree." As discussed above, the record

undermines any such claim. One of the white officers, Mr. Pugel, admitted that he had actual

notice of the fairness hearing notice and the Consent Decree, both of which were posted at his

station house. Supp. 104. In addition, the Police Protective League and newspaper coverage,

Supp. 112-20, reasonably put the white officers on notice that the white officers’ interests might

be affected. The plain fact of the matter is that the white intervenors had sufficient notice

because they knew enough to submit objections to the Decree at the fairness hearing which the

lower court did consider. As this Court held in analogous circumstances: "Actual knowledge

of the pendency of an action removes any due process concerns about notice of the litigation."

EEOC, 897 F.2d at 1508 ("While King and Keith claim they did not receive the EEOC’s notice,

the district court found that Keith had in fact received it, and that both objectors were familiar

with the substance of the notice."); Farwest Steel Corp. v. Barge Sen-Span 241, 769 F.2d 620, 623

(9th Cir. 1985) (acknowledgement of actual notice of lien "remove[es] any due process concerns

about notice); Lehner v. United States, 685 F.2d 1187, 1190-91 (9th Cir. 1982), cert denied, 460

U.S. 1039, 103 S.Ct. 1431, 75 L.Ed.2d 790 (1983) (claim of failure to notify a person of a

foreclosure sale in writing rejected where "the record reveals clearly that she knew the

foreclosure sale was imminent," "[h]er repeated efforts to delay the impending sale attest to her

knowledge," and "[s]he makes no suggestion that the written notice would have supplied

information not already known to her or that it would somehow facilitate judicial review of her

claims, nor did she allege that she never received actual notice of the foreclosure sale").

As to an opportunity to be heard, the white officers submitted objections to the Decree

as amici, the district court continued the fairness hearing to consider their objections, the lower

court permitted the white officers to extensively brief their objections, one of the objections was

accepted by the court and the Decree was modified. The plenary nature of the hearing

24

accorded the white officers is suggested by the extent to which their intervention papers merely

reiterate claims made by them as amici. The white officers, therefore were "affordjed] an

opportunity to present their objections," Mullane, 339 U.S. at 314; EEOC, 897 F.2d at 1508.

At best, the white officers merely present an alternative view of the evidence. "Where

there are two permissible views of the evidence, the factfinder’s choice between them cannot

be clearly erroneous." Bessemer City, 470 U.S. at 574.

With respect to the white officers’ effort to obtain an advisory opinion from the Court

permitting future collateral challenges under Title VII, Article III courts do not sit to provide

such advice where there is no "case or controversy." See Buckley v. Valeo, 424 U.S. 11, 96 S.Ct.

612, 46 L.Ed.2d 659 (1976); Aetna Life Ins. Co., v. Haworth, 300 U.S. 227, 240-41, 57 S.Q. 461,

811 L.Ed.2d 617 (1937). If such an opinion were appropriate, the record clearly establishes that

the white employees had both "actual notice" and "a reasonable opportunity to present

objections," as required by 42 U.S.C. § 20003-2(n)(l)(B), such that they may not collaterally

challenge the Decree, as approved, in the future.

25

VII.

CONCLUSION

For the above reasons, the Court should dismiss the appeal and/or affirm the district

court’s order denying intervention as of right.

Dated: June 16, 1993

Respectfully submitted,

BILL LANN LEE

ROBERT GARCIA

NAACP LEGAL DEFENSE AND

EDUCATIONAL FUND, INC.

THERESA FAY-BUSTILLOS

MEXICAN-AMERICAN LEGAL DEFENSE AND

EDUCATIONAL FUND

KATHRYN K. IMAHARA

ASIAN PACIFIC AMERICAN LEGAL CENTER.

By_________ ___________

Robert Garcia

Attorney for PKuptlffs-Appellees

26

STATEMENT OF RELATED CASES

Pursuant to Rule 28-2.6 of the Rules of this Court, counsel for plaintiffs-appellees know

of no related cases pending in this Court.

ATTORNEYS FEES

Pursuant to Rule 28-23 of the Rules of this Court, plaintiffs-appellees request an award

of reasonable attorneys fees, costs and expenses pursuant to 42 U.S.C. § 2000e-5(k).

27