Craven v. Carmical Petition for Writ of Certiorari to the US Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1972

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Craven v. Carmical Petition for Writ of Certiorari to the US Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit, 1972. 45282197-ae9a-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/3c443075-e717-47e0-b6c1-8b783a26eb99/craven-v-carmical-petition-for-writ-of-certiorari-to-the-us-court-of-appeals-for-the-ninth-circuit. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

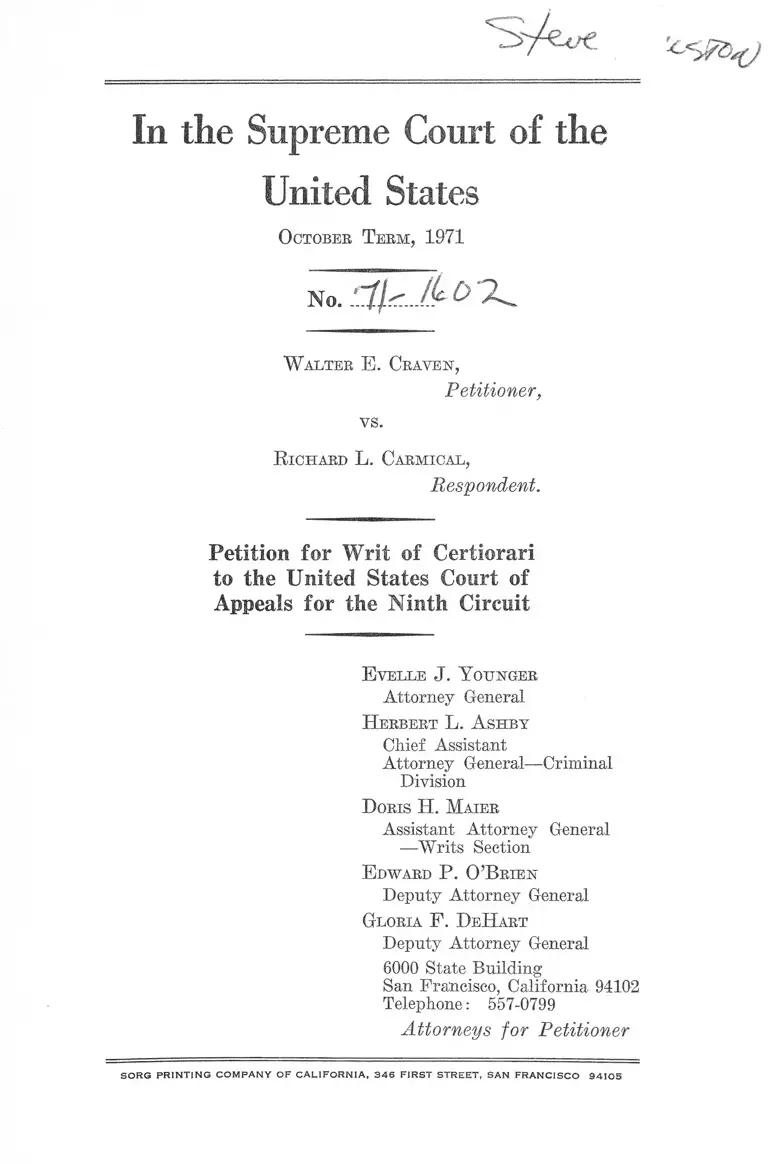

In the Supreme Court of the

United States

October T erm, 1971

No. & X .

W alter E. Graves',

Petitioner,

vs .

R ichard L. Carmical,

Respondent.

Petition for Writ of Certiorari

to the United States Court of

Appeals for the Ninth Circuit

E velle J. Y ounger

Attorney General

H erbert L. A shby

Chief Assistant

Attorney General— Criminal

Division

Doris H. Maier

Assistant Attorney General

—Writs Section

E dward P. O’B rien

Deputy Attorney General

Gloria F. DeH art

Deputy Attorney General

6000 State Building

San Francisco, California 94102

Telephone: 557-0799

Attorneys for Petitioner

S O R G P R IN T IN G C O M P A N Y O F C A L IF O R N IA , 3 4 6 F IR S T S T R E E T , S A N F R A N C IS C O 9 4 1 0 5

SUBJECT INDEX

Page

Opinions Below ... ...........-.................................................. 1

Jurisdiction .............................................................-......... 2

Questions Presented ........................-............................... 2

Statutes Involved ............................................................ - 2

Statement of the Case................................ ..................... 3

A. Proceedings in the State Courts.......................... 3

B. Proceedings in the Federal Courts...................... 4

Statement of Facts................ ...................—-......-.......- 4

Reasons for Granting the Writ............. - ....— ............. 6

Argument ........................................................................... 8

I. The Doctrine of Deliberate By-Pass Should Pre

clude a Defendant Convicted in a Fair Criminal

Trial from Raising on Federal Habeas Corpus

a Claim That the Jury Panel Was Unconstitu

tionally Selected Where the Issue Was Not

Raised at the Appropriate Time in State Court

Proceedings and the Jury Selected Was Ac

cepted by Counsel.................................... -............. 8

II. While a Showing of Disproportional Racial Rep

resentation May Suggest a Prima Facie Case,

on the Further Showing That Such Dispropor

tion Is Not Due to Purposeful Racial Discrimi

nation, No Unconstitutional Selection Is Shown 11

Conclusion — ......................................—- ....... ......... - 16

Appendices

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES CITED

Cases Pages

Carmical v. Craven, 314 F. Snpp. 580 (N.D. Calif.

1970) ............................................................................. 2

Carter v. Jury Commission, 396 U.S. 320 (1970) ....... 13

Donaldson v. California, 404 U.S. 968 (1971) ............ 7

Eubanks v. Louisiana, 356 U.S. 584 (1958) ................. - 11

Fay v. New York, 332 U.S. 261 (1947) .................. 10,12,15

Fay v. Noia, 372 U.S. 391 (1963)............................ ...... 6, 8

Griggs v. Duke Power Company, 401 U.S. 424 (1971) 11

Henry v. Mississippi, 379 U.S. 443 (1965) .................. 8,10

Lattimore v. Craven, 453 F.2d 1249 (9th Cir. 1972) .... 7

People v. Carmical, 258 Cal. App. 2d 103; 65 Cal.

Rptr. 504 (1968) .................... ...................................- 3, 7

People v. Craig, No. 41750 ............................................ 4, 5, 6

People v. Neal, 271 Cal. App. 2d 826; 77 Cal. Rptr. 56

(1969) ........................................................................... 8

Swain v. Alabama, 380 U.S. 202 (1965) ........................ 6,11

Turner v. Fouche, 396 U.S. 346 (1970) ....................13,14,15

Statutes

28 U.S.C.:

Section 1254(1) ............................................................ 2

Sections 2241-2255 ...................................................... 2

California Penal Code:

Section 1060 ................................................................. 3,8

Section 12021 ................................................................ 3

California Code of Civil Procedure, Section 198 ....... 3, 5

California Health and Safety Code, Section 11500 ....... 3

In the Supreme Court of the

United States

October Term, 1971

No................

W alter E. Craven,

Petitioner,

vs.

R ichard L. Carmical,

Respondent.

Petition for Writ of Certiorari

to the United States Court of

Appeals for the Ninth Circuit

Petitioner, Walter E. Craven, Warden of the California

State Prison at Folsom, appellee below, respectfully peti

tions that a Writ of Certiorari issue to the United States

Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit to review the deci

sion of that Court entered on November 4, 1971, reversing

and remanding the order of the United States District

Court.

OPINIONS BELOW

The opinion of the Court of Appeals is appended hereto

as Appendix A.1 The opinion of the United States District 1

1. The opinion was reported in the Advance Reports at 451

F. 2d B99. The index of the bound volume contains the notation

“ Withdrawn by Order of Court.”

Court is reported, Carmical v. Craven, 314 F. Supp. 580

(N.D. Calif. 1970), and is appended hereto as Appendix B.

JURISDICTION

On November 4,1971, the United States Court of Appeals

for the Ninth Circuit reversed the order of the United

States District Court for the Northern District of Cali

fornia denying Richard L. Carmical’s petition for Writ of

Habeas Corpus. Petitioner-appellee’s petition for rehearing

and suggestion for rehearing en banc was denied on May

11, 1972, two judges voting for a rehearing en banc. A copy

of the order is appended hereto as Appendix C. The juris

diction of this Court is invoked under Title 28, United

States Code, section 1254(1).

QUESTIONS PRESENTED

1. Whether the doctrine of deliberate by-pass precludes

a state prisoner from raising on federal habeas corpus an

allegation of an unconstitutionally selected jury panel

where he has not raised the issue in accordance with state

procedures, where counsel at trial accepted the jury after

voir dire, and where there is no allegation of unfairness in

the trial.

2. Whether a case of unconstitutional jury selection is

shown by allegations that a disproportionate number of

blacks were excluded from the jury panel when the allega

tions also establish that the disproportion resulted from

the application of an objective, if imperfect, standard and

did not result from intentional or purposeful racial dis

crimination.

2

STATUTES INVOLVED

This case arises under the Federal Habeas Corpus Act,

28 U.S.C. sections 2241-2255, but does not directly bring any

section into question. Also involved are California Penal

Code section 1060 and California Code of Civil Procedure

section 198 reproduced in Appendix D.

STATEMENT OF THE CASE

A. Proceedings In tie State Courts,

Richard L. Carmieal, the petitioner for Writ of Habeas

Corpus in the District Court, appellant below, and respond

ent here, was convicted in the Alameda County court by

jury verdict of violations of California Health and Safety

Code section 11500 (possession of heroin) and Penal Code

section 12021 (convicted felon in possession of firearm)

and, on November 4, 1966, was sentenced to state prison

for the term prescribed by I aw, the sentences to run con

currently.

Respondent appealed his conviction, which was affirmed

on January 22, 1968, by the California Court of Appeal.

People v. Carmieal, 258 Cal.App.2d 103; 65 Cal. Rptr.

504 (1968). Petitions for rehearing in the Court of Appeal

and for hearing in the California Supreme Court were

denied on February 21, 1968, and March 20, 1968, respec

tively. At trial and on appeal, petitioner urged that his

arrest, the seizure of the weapon, and the subsequent search

and seizure of the heroin were unlawful. No challenge was

made to the jury panel at trial or on appeal.2

Subsequently, Carmieal filed petitions for Writ of Habeas

Corpus in the state courts alleging that he was unconstitu

tionally convicted by a jury panel from which potential

jurors had been unconstitutionally excluded. The petitions

were denied without opinion.

2. Carmieal also argued on Ms state appeal that the amount of

heroin was insufficient to sustain the conviction and that the court

erred in re-reading testimony and instructions. These issues were

not urged in subsequent federal court proceedings.

3

B. Proceedings in the Federal Court's.

On September 17, 1969, Carmical filed a petition for Writ

of Habeas Corpus in the United States District Court for

the Northern District of California alleging that his convic

tion was based on evidence seized in an illegal search and

that potential jurors had been unconstitutionally excluded

from the jury panel. The court issued its Order to Show

Cause on January 22, 1970, a timely return was filed, and

on March 20, 1970, a hearing was held at which counsel for

Carmical and for the Warden appeared. Following the filing

of supplemental memoranda, the court on July 9, 1970, filed

its order denying the petition, finding that there was no

purposeful discrimination on grounds of race in the selec

tion of the jury panel and that the seizure of evidence was

lawful. Carmical appealed to the Court of Appeals for the

Ninth Circuit on the issue of the selection of the jury panel.

On November 4,1971, that court issued its opinion reversing

the order of the District Court and remanding the case for

further proceedings.

STATEMENT OF FACTS

The issues herein were framed and decided on the basis

of the allegations of the petition and its exhibits filed in

the District Court. Carmical filed as an exhibit and relied

on the facts noted in the decision of an Alameda County

Superior Court judge who in 1968 found the jury selection

procedure unfair. People v. Craig, No. 41750. A copy is

appended hereto as Appendix E. The state accepted the

allegations as true for the purpose of testing their suffici

ency to sustain Carmical’s claim that the jury panel uncon

stitutionally excluded members of his race.

At the time of Carmical’s trial in 1966, the County of

Alameda used a “ clear-thinking” test to select master jury

panels from voter registration lists, in accordance with the

4

requirement of California Code of Civil Procedure section

198 that a juror be in “possession of his natural faculties,

and of ordinary intelligence and not decrepit.” The test

consisted of 25 multiple choice questions which had to be

answered in ten minutes.3 In order to qualify for the master

jury panel, prospective jurors had to give correct answers

to 21 of the questions, but were not told about the time limit.

For the purposes of the hearing on the issue in the Craig

case, a special analysis of test results was made for areas

of Oakland selected by defendant Craig’s counsel, one an

area of predominantly black and low income persons, the

other one an area of predominantly white and middle or

higher income persons. The analysis disclosed that in the

former (West Oakland) area the failure rate was 81.5%,

and in the latter (Montclair) area the failure rate was

14.5%. Testimony of a psychologist at this hearing indi

cated that the test, while giving the appearance of being an

intelligence test, contained some items reflecting the cultural

bias of the author; that it was too short to take into con

sideration the subcultures of a heterogeneous population;

that the time allowed for taking the test was too short; that

it was poor procedure not to inform those that were taking

it that there was a time limit; and that the grade required

forpassing the test was too high. See Appendix E at 27.

In an affidavit filed with the District Court, this psycholo

gist concluded that because it was “difficult” to come to the

conclusion that such a high percentage of “non-white” per

sons are below the level of average in intelligence, the test

must measure something else. Questions with a “ cultural

bias” such as numbers 20, 21 and 25 “ could account” for this

percentage. The psychologist stated that in his opinion,

“ the test was evidently made up without considering cultu

ral differences between persons taking it with the apparent

5

3. A copy of the test is appended hereto as Appendix F.

result that an extraordinarily high percentage of non-white

persons failed it.”

The analysis made also revealed, as noted in the Craig

opinion (Appendix E at 25) that in the categories of exclu

sions where conscious or even subsconscious bias could

operate, substantially equal numbers from each area were

excused. These persons were excluded during an initial

screening process for reasons such as health, hardship or

occupational exemption before the objective test was admin

istered.

Thus, the “ facts” stated in the petition and exhibits

established that there wTas a disproportionate exclusion of

low income blacks, that it was due to an objective test ad

ministered to all potential jurors, and that such dispropor

tion was inadvertent, not purposeful.

REASONS FOR GRANTING THE WRIT

The Court of Appeals on this record erroneously decided

two important constitutional questions, holding: (1) that

the doctrine of deliberate by-pass does not apply to a

defendant who fails to challenge the composition of the jury

panel in the state proceedings and is fairly tried by a jury

with which he is satisfied unless the record shows an affirma

tive waiver; and (2) that a prima facie case of unconstitu

tional selection of the jury panel is sufficiently established

by alleging that disproportionate numbers of poor minority

groups were excluded, despite further allegations showing

that the exclusion wTas the result of an objective test and

that there was no purposeful discrimination based on race.

The decision of the Court of Appeals incorrectly inter

prets the decisions of this Court in Fay v. Noia, 372 U.S.

391 (1963) and Swain v. Alabama, 380 U.S. 202 (1965) and

is in conflict with the decision of another panel of the Court

of Appeals which cited Swain v. Alabama, supra, for a con-

6

Aiding proposition and apparently reached an opposite

result on the by-pass issue. See, Lattimore v. Craven, 453 ( t,

F.2d 1249 (9th Cir. 1972).4 We also invite this Court’s

attention to Donaldson v. California, 404 U.S. 968 (1971)

. . . f> i lin which this Court denied certiorari to review a case up

holding a selection procedure similar to that at issue here.

The ruling in this case could result in the retrial of every ,

minority group defendant sentenced to state prison in / /V£«.

Alameda County since 1957,4 5 although the defendants were ? / ,

satisfied with their juries at the time of trial, there may

have been any number of their minority group on the juries "t&u* -

which convicted them, there was no unfairness or denial of

+ in,.

due process in the trials, there was no purposeful discrimi

nation practiced by Alameda County, and the use of the®6̂ -

test at issue was discontinued in 1968. We submit that the

ruling of the Court of Appeals is not required by the con

stitution, as interpreted by this Court, and that the poten

tial effect of the court’s ruling on final, fairly tried state

criminal cases is unconscionable.

4. In Carmical, the court states:

“ The object of the constitutional mandate is to produce

master jury panels from which identifiable classes have not

been systematically excluded. The object is neither to reward

jury commissioners with good motives nor to punish those

with bad intentions. When a jury selection system actually

results in master jury panels from which identifiable classes

are grossly excluded, the subjective intent of those who

develop and enforce the system is immaterial.” App. A at 5.

In Lattimore, in contrast, the court stated:

“ The absence of persons of a particular race on a jury

panel is no indication of discrimination. To challenge a jury

panel on the grounds of racial discrimination, there must be a

purposeful discrimination proven by systematic exclusion

of eligible jurors of the proscribed race or by unequal

application of the law to such an intent, as to show inten

tional discrimination.” 453 F.2d at 1251.

n sc , .£•

K | T v ?*

5. There were 1,161 defendants convicted in jury trials between

February 1957 and April 1968; of these, 583 were sent to state

prison. Although the race of those defendants is unknown, and a

number of them have undoubtedly completed their terms, it is

evident that retrials in the hundreds may be required by this

opinion.

ARGUMENT

I. The Doctrine of Deliberate By-Pass Should Preclude a Defend

ant Convicted in a Fair Criminal Trial front Raising on Federal

Habeas Corpus a Claim That the Jury Panel W as Unconsti

tutionally Selected Where the Issue Was Not Raised at the

Appropriate Time in State Court Proceedings and the Jury

Selected Was Accepted by Counsel.

At Ms trial in the Superior Court, petitioner did not

challenge the composition of the jury panel on any grounds

whatever, nor did he raise on appeal any issue concerning

the jury. He was represented by competent counsel at all

times.

Under California law, a challenge to the composition of

the jury panel must he made before the panel Is sworn.

Calif. Pen. Code § 1060; See, People v. Neal, 271 Cal. App.

2d 826, 836-837; 77 Cal. Rptr. 56 (1969). The right to an

impartial jury drawn from a cross section of the community

has been long recognized. Petitioner was represented by

counsel. Thus, petitioner failed to assert a known right in

accord with reasonable state procedure and was apparently

satisfied with the jury selected. See CT-7.

It is well established that a federal court may refuse to

consider a constitutional claim on its merits when a deliber

ate by-pass is shown. Fay v. Noia, 372 U.S. 391, 438 (1963).

The deliberate by-pass by counsel of a state procedural

rule serving a legitimate state interest will preclude an

accused from asserting his constitutional claim unless the

circumstances are exceptional. Henry v. Mississippi, 379

U.S. 443 (1965). (Contemporaneous objection rule.)

In ruling against respondent on the question of deliberate

by-pass the court below stated: “ There is nothing in either

the state court proceedings or the record below suggesting

that Carmical’s attorney declined to raise the issue for

some strategic purpose.” App. A at 1. We submit that this

8

conclusion overlooks the nature of the right at issue and the

compelling state interest in the procedural :rule involved.

The right at issue here is the right to challenge the com

position of and the process for selecting the jury panel

from which the jury to try the case is drawn. There are

obviously two aspects to permitting such a challenge; one

is the right of the defendant not to have members of his

race purposefully excluded, the other is the right of mem

bers of the excluded group to serve on juries. We point out

that the latter interest is not involved here; the test is no

longer being used.

The defendant’s right to have his race represented on the

panel is fully served by requiring that the challenge be

made before the jury is sworn. In any case of general dis

proportionate representation in the entire jury panel, it is

obvious that any single panel may contain substantial num

bers of the minority group. Conversely, even when general

representation is proportionate any single panel might not

contain any members of the minority group. Thus, counsel

could reasonably conclude that no useful purpose as far as

his client was concerned would be served by challenging

the panel.

The court below, in holding that there was no strategic

purpose evident for failing to raise the issue below, com

pletely failed to consider that no strategic purpose, except

delay, would be served by making such a challenge. Indeed,

if substantial members of Negroes were on the panel, a

challenge would risk getting a panel with fewer Negroes.

Counsel’s concern in any case is selecting a jury which he

believes will give his client a fair trial. After examining and

accepting a jury, counsel has affirmatively indicated his

belief that his client can be fairly tried by it. If he does not

so believe, his challenge should be made at the time, not

held in reserve to be used if his client is convicted. Either

9

course of action, however, provides the strategic purpose

for finding deliberate by-pass.®

Finally, we note that this Court has implicitly accepted

the concept that failure to challenge the jury before trial

precludes relief. In Fay v. New York, 332 U.S. 261, 266

(1947) in discussing a challenge to the “ blue ribbon” jury,

this Court notes that if the challenge was good, all con

victions by special juries “would be set aside if the question

had been properly raised at or before trial.” (Emphasis

added.)

The right to challenge a jury is a particularly appro

priate right to which to apply a rule that failure to properly

raise the issue precludes subsequent relief without a show

ing of affirmative waiver, and a particularly inappropriate

one to apply a rule that personal waiver is required. In this

respect, it is analogous to the right to present witnesses for

the defense, the right of the defendant to testify, or the

right to cross-examine any witness. That these rights have

been waived is implicit in the failure to exercise them.

Moreover, the right to challenge the jury panel, while im

portant, has no necessary effect on the fairness of the en

suing trial, and no effect on the validity of the fact finding

process.

We submit that the acceptance of the jury should be a

sufficient showing of an affirmative waiver of the right to

challenge the panel without further inquiry into knowledge,

reasons or trial strategy. Where neither defendant nor

counsel expresses any dissatisfaction with the jury and

there is no question that the trial was fair, no legitimate

interest of the accused is protected by permitting collateral

attack, and the legitimate, indeed compelling, interest of

the state in the finality of fair convictions is destroyed.

6. See Henry v. Mississippi, supra, at 451. Any right of the

excluded group is equally fully served by requiring the challenge to

be made at this point. Moreover, the excluded group may bring

an action independent of any criminal case.

10

||. While a Shewing of Disproportionol Racial Representation

May Suggest a Prima Facie Case, on the Further Showing a

That Such Disproportion Is Not Due to Purposeful Racial Dis- ..

crimination, No Unconstitutional Selection Is Shown. ) ( , ^

The allegations of the petitioner established that dis- ' f j,

proportionate numbers of minority and low income persons W l .

were excluded from the master jury panel; that the exclu-

sion resulted from the use of a “ clear thinking” test of 25

objective questions used to select juries of “ ordinary” in

telligence; and that the test did not accurately measure

average intelligence and may have been culturally biased.

The allegations also established, however, that there was

no purposeful discrimination based on race.

The decisions of this Court involving jury selection have

uniformly held that while mere disproportion may establish

a prima facie case of racial discrimination it is only pur

poseful exclusion on grounds of race which is unconstitu

tional. See, e.g., Swain v. Alabama, 380 U.S. 202 (1965);

Eubanks v. Louisiana, 356 U.S. 584 (1958).

The court below held, however, despite the uncontested

showing that no purposeful discrimination took place and

the disproportion was due to the application of an objective

standard, that a prima facie case of unconstitutional dis

crimination was shown. The reasons for the court’s holding

were that the test did not measure “average intelligence,”

that it was culturally biased, and that purposeful discrim

ination is not a factor. The court noted that Griggs v. Duke

Power Company, 401 U.S. 424 (1971), epitomizes a trend

toward the proscription of devices that result in the ex

clusion of minority groups.7 App. A at 7, N.3.

7. Griggs involved the interpretation of a statute, and held

invalid the use of intelligence tests which were not job related and

resulted in the disqualification of disproportionate numbers of

minority group job applicants. The purpose of the statute was to

mitigate the effects of previous discrimination.

11

Whatever the trend of the decisions may he in other

areas, this Court has always found purposeful discrim

ination the sine qua non of unconstitutional jury selection.

That the test at issue here did not measure “average”

intelligence and might have been “ culturally biased” does

not make it unconstitutional. In Fay v. New York, supra, at

291, the Court notes:

“ Even in the Negro cases, this Court has never

undertaken to say that a want of proportional repre

sentation of groups, which is not proved to be delib

erate and intentional, is sufficient to violate the Con

stitution.”

In Fay v. New York, this Court considered the validity

of New York special juries on charges that their use un

fairly narrowed the choice of jurors. The criteria used in

selecting the general panel from which the special juries

were selected on the basis of further qualifications were:

citizen; 21-70 years old; the owner or the spouse of the

owner of property of value of $250.00; not convicted of

felony or misdemeanors involving moral turpitude; intel

ligent; of sound mind and good character; well informed;

able to read and write the English language understand-

inglv. Fay at 266-267.

This Court noted (at 291) :

“At most the proof shows lack of proportional

representation and there is an utter deficiency of

proof that this was the result of a purpose to discrim

inate against this group as such. The uncontradicted

evidence is that no person was excluded because of

his occupation or economic status. All were subjected

to the same tests of intelligence, citizenship, and under

standing of English. The state’s right to apply these

tests is not open to doubt even though they disqualify,

'1 especially in the conditions that prevail in New York,

a disproportionate number of manual workers. A fair

1 2

application of literacy, intelligence and other tests

would hardly act with proportional equality on all

walks of life.” (Emphasis added.)

As in the instant case, the disproportion only raised the

question of unlawful representation. Since it resulted from

the application of an objective standard, it was constitu

tional.

In two recent cases, the Supreme Court has stated that

a state may properly use tests of intelligence or education

to select jurors. Carter v. Jury Commission, 396 U.S. 320

(1970); Turner v. Fouche, 396 U.S. 346 (1970). What it

may not do is extend the right or duty of jury service to

some of its citizens and deny it to others on racial grounds.

Carter, supra at 330.

In Carter this Court considered the validity on its face

of a statute which required the selection for jury service

“ those persons who are ‘generally reputed to be honest and

intelligent and . . . esteemed in the community for their

integrity, good character, and sound judgment. . . Carter

at 331. The Court declined to hold the statute invalid:

“ It has long been accepted that the Constitution does

not forbid the States to prescribe relevant qualifica

tions for their jurors. The States remain free to

confine the selection to citizens, to persons meeting

specified qualifications of age and educational attain

ment, and to those possessing good intelligence, sound

judgment, and fair character. ‘Our duty to protect the

federal constitutional rights of all does not mean we

must or should impose on states our conception of the

proper source of jury lists, so long as the source rea

sonably reflects a cross-section of the population suit

able in character and intelligence for that civic duty.’ ”

Carter at 332-33 (Footnotes omitted).

This Court subsequently commented:

“ The provision is devoid of any mention of race. Its

antecedents are of ancient vintage, and there is no

13

suggestion that the law was originally adopted or sub

sequently carried forward for the purpose of fostering

racial discrimination.” (Footnotes omitted). Carter

at 336.

In Turner v. Fou-che, supra, the Court also declined to

strike down similar provisions as invalid. However, in

Turner, the record disclosed that of 178 potential jurors

rejected by the jury commissioner “ as not conforming to

the statutory qualifications for juries either because of

their being unintelligent or because of their not being up

right citizens,” 171 were Negroes. The court held that the

district court should have responded to this fact and to the

fact that 225 potential jurors (9% of the county popula

tion) who were unknown to the commissioner were ex

cluded without further inquiry:

“ In sum, the appellants demonstrated a substantial

disparity between the percentages of Negro residents

in the county as a whole and of Negroes on the newly

constituted jury list. They further demonstrated that

the disparity originated, at least in part, at the one

point in the selection process where the jury commis

sioners invoiced their subjective judgment rather than

objective criteria. The appellants thereby made out a

prima facie case of jury discrimination, and the burden

fell on the appellees to overcome it.

“ The testimony of the jury commissioners and the

superior court judge that they included or excluded

no one because of race did not suffice to overcome the

appellants’ prima facie case. So far the appellees have

offered no explanation for the overwhelming percent

age of Negroes disqualified as not ‘upright’ or ‘intel

ligent,’ nor for the failure to determine the eligibility

of a substantial segment of the county’s already regis

tered voters. No explanation for this state of affairs

appears in the record. The evidentiary void deprives

the District Court’s holding of support in the record as

14

presently constituted. ‘If there is a ‘vacuum’ it is one

which the State must fill, by moving in with sufficient

evidence to dispel the prima facie case of discrimina

tion.’ ” (Footnotes omitted.) Turner at 360-61.

Applying the standards of these cases to the facts in the

instant case, it is clear that there is no discrimination based

on race. Here, in contrast to Turner, the facts disclose that

the “disparity” in percentages occurred at the point in the

process where completely objective criteria were used. At

the point in the selection process where even unconscious

bias could contribute to the result, proportionately equal

numbers of jurors were excluded.

We note that any test of education or even “ ordinary”

intelligence is going to be culturally biased. One becomes

educated by absorbing the wisdom and language of the pre

vailing culture. “ Ordinary,” too, may be interpreted as the

prevailing level of intelligence and education among the

general population and thus connotes cultural understand

ing. While the state may not exclude persons because of

their race or economic status, it need not change its stand

ards to insure proportional representation of any particular

group.

Finally, standards used to insure that minority group

members have equal opportunities for jobs have no nec

essary application to the problem of jury selection.8 The

reason for allowing challenges to the jury by the defendant

is because he may well say that a community which dis

criminates against all Negroes discriminates against him.

See, Fay v. New York, supra, at 293. Where there is no pur

8. If the rule on jury selection is to be changed, then it is an

obvious rule for completely prospective operation. Trials under the

old standard were completely fair and the validity of the fact

finding process is not affected. In contrast, the effect on the states

would be catastrophic.

15

poseful discrimination, no such prejudice exists. Such is

the case here. We submit that the court below has errone

ously interpreted governing case law, and has reached a

conclusion with a potentially devastating effect.

CO N CLUSIO N

Because of the importance of the two cpiestions involved,

and the potential effect on the state’s system of justice, we

respectfully request that the Writ of Certiorari be granted.

E velle J. Y ounger

Attorney General

H erbert L. A shby

Chief Assistant

Attorney General— Criminal

Division

D oris H. Mater

Assistant Attorney General

—Writs Section

E dward P. O’Brien

Deputy Attorney General

Gloria F. D eH art

Deputy Attorney General

6000 State Building

San Francisco, California 94102

Telephone: 557-0799

Attorneys for Petitioner

16

(Appendices Follow)

Appendix A

United States Court of Appeals

for the Ninth Circuit

No. 26,236

Richard L. Carmical,

Petitioner-Appellant,

vs.

Walter E. Craven, Warden, California

State Prison at Folsoin,

Respondent-Appellee.

[November 4,1971]

Appeal From the United States District Court

for the Northern District of California

Before: BARNES, HAMLEY, and HUFSTEDLER,

Circuit Judges

HUFSTEDLER, Circuit Judge:

Appellant Carmical appeals from an order denying his

petition for a writ of habeas corpus. His petition charged

that his state court conviction was invalid because he was

tried by a jury drawn from a jury panel unconstitutionally

selected.

Before we discuss the merits of the petition, we dispose

of appellee’s contention that Carmical had waived his jury

discrimination claim by his failure to raise the question at

the time he was tried in the state court in November 1966.

The state court record contains no indication of any affirm

ative act on Carmical’s part evidencing his deliberate re

jection of his constitutional guaranty. (McNeil v. North

Carolina (4th Cir. 1966) 368 F.2d 313, 315.) There is noth

ing in either the state court proceedings or the record

2 Appendix

below suggesting that Carmical’s attorney declined to raise

the issue for some strategic purpose. As the district court

impliedly found, the ingredients for deliberate bypass spec

ified in Fay v. Noia (1963) 372 U.S. 391 are lacking, and

the issue is not foreclosed on collateral attack. (Cobb v.

Balkcom (5th Cir. 1964) 339 F.2d 95; cf. Fernandez v.

Meier (9th Cir. 1969) 408 F.2d 974.)

For the purpose of testing the sufficiency of Carmical’s

averments, prima facie, to sustain his claim for habeas

relief, the appellee admitted the truth of the matters set

forth in the petition and exhibits filed in support of it. The

petition and the exhibits include the following facts: Car-

mical was tried and convicted for possessing heroin and

for illegally possessing a firearm. At the time of his trial

in Oakland, California, Oakland used a “ clear thinking”

test to select a master jury panel from the voter registra

tion lists. The test purportedly winnowed voters of below

“ ordinary intelligence,” leaving only those who satisfied

California’s statutory commandment that a juror be “ [i]n

possession of his natural faculties and of ordinary intelli

gence and not decrepit.” (Cal. Civ. P. Code § 198 (2) (West

1954).) The test consisted of 25 multiple-choice questions

which had to be answered in 10 minutes. Prospective jurors

were not told about the time limit before they took the

test. To qualify for the master jury panel, prospective

jurors were required to give “ correct” answers to at least

80 percent of the questions.1

The use of this test excluded a substantial majority of

otherwise eligible minority and low income persons from 1 2 3

1. “ Correct” answers were those supplied by the manufacturer

of the test. We use “ correct” pejoratively because we cannot

describe as “ right” any of the choices given for some of the

questions asked. Here are three simples from the test:

“ 4. Why is a man suprior to a productive machine?

1. A man has a sense of humor.

2. A man can think.

3. A machine requires repairs. ’ ’

Appendix 3

the master jury roll. In the second half of 1967, 81.5 per

cent of registered voters from predominantly black and low

income areas of Alameda County who took the test failed

to pass it. In contrast, only 14.5 percent of those eligible

jurors from predominantly white areas taking the test

failed to pass it. A total of 29 percent of all persons tested

failed the examination. At the time of Carmical’s prosecu

tion in 1966, registered voters from predominantly white

areas were nearly four times as likely to pass the test as

were voters from black and low income areas.

A psychologist who is an expert on reliable testing meth

ods declared by affidavit that: (1) the test contained many

administrative flaws; (2) the high failure rate indicated

that the test was excluding persons of ordinary intelli

gence; and (3) certain cpiestions measured cultural rather

than intelligence factors.

In 1968, the Superior Court for the County of Alameda

prohibited further use of the test because it separated ex

aminees on some basis other than “ ordinary intelligence.”2

The facts accepted as true for purposes of this appeal

established a prima facie case of class exclusion from the

jury selection process. In Whitus v. Georgia (1967) 385 U.S.

545, jurors were selected from tax digests previously main

tained on a segregated basis. Blacks constituted 27.1 per

cent of persons potentially eligible for jury service. Only

9.1 percent of the grand jury venire and 7.8 percent of the * 1

“ 23. If a person asks you for something you do not have,

you should:

1. Tell him to mind his own business.

2. Say you don’t have it.

3. Walk away.”

‘ £ 25. If it rains when you are starting to go for the doctor,

should you :

1. Stay at home.

2. Take an umbrella.

3. Wait until it stops raining. ’ ’

2. People v. Craig (Super Ct. of Alameda County 1968) No.

41750.

4 Appendix

petit jury venire were blacks. There was no evidence that

any of the 27.1 percent eligible black jurors were disquali

fied from jury service. There existed a 3-to-l disparity

between blacks eligible for jury service and those on the

grand jury venire and a 3.5-to-l disparity on the petit jury

venire. Ten out of 123 persons on both venires, or 8.1 per

cent, were blacks, a disparity of 3.3-to-l. Here, the test

excluded from jury service 81.5 percent of the registered

voters from black and low income neighborhoods, leaving

19.5 percent. The state offered no evidence that any voter

disqualified by the test was disqualified for other reasons.

The ratio of eligible black and low income persons to those

placed on the master list was 4.2-to-l, a disparity greater

than that condemned in Whitus.

Once Carmical has presented his prima facie case, the

state must adduce evidence sufficient to rebut it. (E.g.,

Coleman v. Alabama (1967) 389 U.S. 22; Hill v. Texas

(1942) 316 U.S. 4001; Norris v. Alabama (1935) 294 U.S.

587.)

The sole issue on appeal is a narrow question of law: Is

proof alone that the “ clear thinking” test in fact resulted

in large-scale exclusion of identifiable classes of veniremen

otherwise eligible for jury service sufficient to make out a

prima facie case of constitutionally impermissible jury

selection, or, as the state contends, must Carmical also

have offered evidence that the “ clear thinking” test was

intentionally designed to produce that result?

The narrowness of the question does not obscure its con

stitutional importance. Trial by jurors selected from the

broad spectrum of society is a constitutional mandate.

{E.g., Carter v. Jury Commission (1970) 396 U.S. 320, 330;

Smith v. Texas (1940) 311 U.S. 128, 130.) A state may not

systematically exclude persons from the jury selection

process on the basis of their race, color, national origin,

or on other identifiable group characteristics. {E.g., Whitus

Appendix 5

v. Georgia, supra; Hernandez v. Texas (1954) 347 U.S.

475; Strauder v. West Virginia (1879) 100 IT.S. 303.) Token

inclusion of members of the affected class in the selection

process does not satisfy that fundamental command. (See

Jones v. Georgia (1967) 389 U.S. 24; Whitus v. Georgia,

supra; Smith v. Texas, supra.) Although petitioner is not

constitutionally required to be tried by a jury including

persons from his race or class or by a jury proportionately

representative of the community (e.g., Swain v. Alabama

(1965) 380 IT.S. 202, 208; Thomas v. Texas (1909) 212 U.S.

278), he is entitled to a jury selected from a master list

drawn from the community as a whole.

It is true that almost all of the cases that have come be

fore the Supreme Court challenging the constitutionality

of jury selection systems have been cases in which the

methods of selection were explicitly or implicitly designed

to exclude Negroes from jury service. {E.g., Whitus v.

Georgia, supra [segregated tax returns]; Eubanks v. Lou

isiana (1958) 356 U.S. 584 [judges interviewed prospective

jurors]; Avery v. Georgia (1953) 345 U.S. 559 [segregated

jury tickets]; Hill v. Texas, supra [jury commissioners

failed to search out qualified blacks] ; Smith v. Texas, supra

[blacks placed last on jury list]; Bush v. Kentucky (1882)

107 U.S. 110 [blacks excluded by law ]; Neal v. Dela

ware (1880) 103 U.S. 370 [blacks presumed incompetent

to serve as jurors].) The opinions take into account the

historical prevalence of intentional discrimination against

Negroes, but the Court has never implied that the absence

of that factor destroys a prima facie case. Rather, the

Court has charged state officials with an affirmative duty

to seek, and include within the jury selection process, all

persons qualified under state law. As the Court stated in

Avery v. Georgia, supra, 345 U.S. at 561:

“ The Jury Commissioners, and the other officials

responsible for the selection of this panel, were under

6 Appendix

a constitutional duty to follow a procedure—‘a course

of conduct’—which would not ‘operate to discriminate

in the selection of jurors on racial grounds.’ Hill v.

Texas, 316 U.S. 400, 404 (1942). If they failed in that

duty, then this conviction must be reversed—no mat

ter how strong the evidence of petitioner’s guilt. That

is the law established by decisions of this Court span

ning more than seventy years of interpretation of the

meaning of ‘equal protection.’ ”

(Accord, Eubanks v. Louisiana, supra, 356 U.S. at 587,

quoting from Patton v. Mississippi (1947) 332 U.S. 463,

469; Cassell v. Texas (1950) 339 U.S. 282, 289.)

To support its argument that the Constitution does not

forbid a system of jury selection that substantially ex

cludes identifiable classes of prospective jurors, but only

forbids systems deliberately designed to accomplish that

result, the state relies on a passage from Swain v. Ala

bama, supra, 380 U.S. at 209:

“Undoubtedly the selection of prospective jurors was

somewhat haphazard and little effort was made to en

sure that all groups in the community were fully rep

resented. But an imperfect system is not equivalent to

purposeful discrimination based on race.”

Swain will not carry the burden the state puts upon it.

The object of the constitutional mandate is to produce

master jury panels from which identifiable community

classes have not been systematically excluded. The object

is neither to reward jury commissioners with good motives

nor to punish those with bad intentions. When a jury selec

tion system actually results in master jury panels from

which identifiable classes are grossly excluded, the subjec

tive intent of those who develop and enforce the system

is immaterial. For example, in Norris v. Alabama, supra,

294 U.S. at 598, the Court related testimony by jury offi

cials that they had not considered race or color in prepar

ing the jury roll. The Court then observed:

“ If, in the presence of such testimony as defendant

adduced, the mere general assertions by officials of

their performance of duty were to be accepted as an

adequate justification for the complete exclusion of

negroes from jury service, the constitutional provision

—adopted with special reference to their protection—

would be but a vain and illusory requirement.”

{Accord, Turner v. Fouche (1970) 396 U.S. 346, 361; Sims

v. Georgia (1967) 389 U.S. 404, 407-08; Hernandez v. Texas,

supra, 347 U.S. at 481-82; Smith v. Texas, supra, 311 U.S.

at 131-32.) The lack of specific intent to discriminate on

the part of Alameda County’s jury officials cannot offset

the grossly discriminatory effect of their jury selection

process. (Cf. Griggs v. Duke Poiver Co. (1971) 401 U.S.

424 f Gaston County v. United States (1969) 395 U.S. 285;

Gomillion v. Lightfoot (1960) 364 U.S. 339.)

However, proof of deliberate intent to discriminate may

be relevant when, as in Swain, the percentage of excluded

classes is not gross enough unequivocally to establish dis

crimination. Evidence that the system was designed to

discriminate invidiously may add enough strength to such

statistical data to make out a prima facie case. In short,

subjective intent may be relevant to prove that a particu-

3. In Griggs the Court struck down the use of a seemingly

objective test that resulted in inadvertent discrimination, holding

that Title V II of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 proscribed the use

of a standardized intelligence test that was not job related and

operated to disqualify a disproportionate number of black job

applicants. There was no evidence that the test was adopted for a

discriminatory purpose. Although the Act appeared to sanction

testing methods that were not used to discriminate, the Court

found from the legislative history that Congress intended to pro

scribe unintentional as well as intentional discriminatory hirings.

Griggs epitomizes a clearly discernible trend toward the pro

scription of devices that result in the disproportionate exclusion of

minority groups. (See Gaston County v. United States (1969)

395 U.S. 285; Labat v. Bennett (5th Cir. 1966) 365 F.2d 698,

719-20, cert, denied (1967) 386 U.S. 991.)

In Griggs, as well as here, the test was not related to the purpose

for which it was administered. The examiners’ good faith was not

questioned. The resulting discrimination was conclusive.

Appendix . 7

8 Appendix

lar system is invidiously discriminatory, but that evidence

is not an element of the constitutional test.

The Fifth Circuit has squarely held that purposefulness

is not an element of a prima facie case. After discussing a

number of Supreme Court cases in United States ex rel.

Seals v. Wiman (5th Cir. 1962) 304 F.2d 53, 65, cert, denied

(1963) 372 U.S. 924, the court concluded:

“ Those same cases, however, and others, recognize a

positive, affirmative duty on the part of the jury com

missioners and other state officials, and show that it

is not necessary to go so far as to establish ill will,

evil motive, or absence of good faith, but that objec

tive results are largely to be relied on in the applica

tion of the constitutional test.”

In Mobley v. United States (5th Cir. 1967) 379 F.2d 768,

772, the court stated:

“ There is, therefore, an affirmative duty imposed by

the Constitution and laws of the United States upon

the jury selection officials . . . to know the availability

of potentially qualified persons within significant ele

ments of the community, including those which have

been the object of state discrimination, to develop and

use a system that will result in a fair cross section of

qualified persons in the community being placed on

the jury rolls and to follow a procedure which will not

operate to discriminate in the selection of jurors on

racial grounds.”

(Accord, Salary v. Wilson (5th Cir. 1969) 415 F.2d 467,

472; Vanleeward v. Rutledge (5th Cir. 1966) 369 F.2d 584,

586-87.)

The state asserts that Alameda County’s system oper

ated fairly. The Supreme Court approved the use of in

telligence or education as a criterion for jury service in

Carter v. Jury Commission (1970) 396 U.S. 320 and Turner

v. Touch (1970) 396 U.S. 346. The state says that the jury

commissioner utilized the purely objective and proper

Appendix 9

standard of intelligence as indicated by the test results in

preparing the master jury list and that that standard did

not measure race or minority status and could not result

in discrimination.

The state’s argument ignores the record. For the purpose

of the district court’s ruling and upon this appeal, the

state assumed the truth of the contents of the complaint

and the accompanying affidavits. The state has thus con

eeded that the test did not measure average intelligence

for the purpose of posing the legal issue.

In Turner v. Fouche, supra, the Court expressly disap

proved the elimination of 171 blacks on the ground that

they were not intelligent or upright. Although intelligence

was a valid requirement for jury service, the mere asser

tion that a large number of blacks were not intelligent did

not justify their exclusion. Because Alameda County’s test

did not measure intelligence, any reliance on test results

is no more than an unsupported assertion that those per

sons excluded were not intelligent. We perceive no mean

ingful distinction between Turner and this case.

Moreover, the state has also assumed at this juncture

that the test reflected cultural bias. The use of a test that

was culturally biased and that resulted in the substantial

exclusion of those classes against whom the bias existed

is itself prima facie proof that the selection process vio

lated the Fourteenth Amendment. “ An accused is entitled

to have charges against him considered by a jury in the

selection of which there has been neither inclusion nor ex

clusion because of race” or other identifiable minority char

acteristics. (Cassell v. Texas, supra, 339 TJ.S. at 287.)

The order is reversed and the cause is remanded for fur

ther proceedings consistent with the views herein ex

pressed. Upon remand, the state shall have the opportunity

to disprove each of the averments that it has conceded for

the purpose of the prior district court ruling and for the

purpose of this appeal.

10 Appendix

Appendix B

In the United States District Court

for the Northern District of California

No. 52246

Filed—Jul 9 1970

C. C. Evensen, Clerk

Richard L. Carmical,

Petitioner,

vs.

Walter E. Craven, Warden,

California State Prison at Folsom,

Respondent. ,

Charles Stephen Ralston

Oscar Williams

1095 Market St., Snite 418

San Francisco, Calif. 94103

Judith Ann Ciraolo

160 Taurus Avenue

Oakland, California

Attorneys for Petitioner

Thomas C. Lynch

Attorney General of the

State of California

Deraid E. Granberg

Deputy Attorney General

Gloria F. DeHart

Deputy Attorney General

Attorneys for Respondent

OPINION AND ORDER DENYING PETITION

FOR WRIT OF HABEAS CORPUS

GERALD S. LEVIN, District Judge

Appendix 11

Petitioner was convicted and sentenced on November 4,

1966, by the Superior Court in Alameda County, California,

for violations of California Health & Safety Code § 11500

(possession of heroin) and California Penal Code § 12021

(convicted felon in possession of a firearm). He petitioned

this Court for a writ of habeas corpus and on January 22,

1970, this Court issued an Order to Show Cause. Petitioner

bases his petition upon two grounds: First, that the “ clear

thinking” test used in the screening of prospective jurors

at the time of petitioner’s trial “was a gross discrimination

along racial, economic and cultural grounds,” and Second,

that the evidence used to convict petitioner was obtained

as a result of an illegal search and seizure made in the

course of an arrest, which arrest wTas unlawful because of

lack of probable cause for the arrest.1

The Test Used to Screen Prospective Jurors

At the time of petitioner’s trial in 1966, a clear thinking

test was used to select a master jury panel from the voter

registration lists. This test consisted of twenty-five mul

tiple-choice questions which had to be answered in ten

minutes. In order to qualify for the master jury panel

prospective jurors were required to give correct answers

to at least 80 per cent of the questions.

The jury for petitioner’s trial was drawn from this

master jury panel. Petitioner, a Negro, claims that this

clear thinking test excluded a disproportionate number of

1. Although the court is cognizant of its obligation to make an

independent determination of this ground, the court notes that

this contention was passed upon by the California Court of Appeal

and found to be without merit. People v. Carmical, 258 Cal.App.2d

103, 65 Cal.Rptr. 504 (1968); hearing denied by the California

Supreme Court March 20,1968.

12 Appendix

Negroes and low income persons. In People v. Craig,2 adju

dicated subsequent to the trial of petitioner, the Court con

sidered this test as used to screen prospective jurors and

found that it excluded a disproportionate number of

Negroes and persons of low economic income. The expert

testifying in that case expressed the opinion that the test

had a tendency to exclude people from the ghettoes because

of “ inadvertent discrimination.” The Court did not hold

this test to be unconstitutional or unfair but merely directed

the Jury Commissioner to summon a panel of jurors “ in a

manner consistent with this decision.”

Assuming that this test excluded proportionately more

Negroes and more persons of low economic income as com

pared to persons in middle or upper income classes, there

is no evidence or showing that there was any purpose to

exclude a disproportionate number of Negroes or low in

come persons. Furthermore, this test was administered

equally to all persons regardless of race or income.

In Swain v. Alabama, 380 U.S. 202 (1965), the Court

affirmed petitioner’s conviction despite his allegation of

racial discrimination in the selection of jurors. While

Negroes constituted 26% of the males over 21 in that

county, only 10% to 15% of the grand and petit jury panels

were Negroes. Alabama law required the jury commis

sioners to place on the jury roll all male citizens in the

community over 21 who are reputed to be honest, intelligent

men and are esteemed for their integrity, good character

and sound judgment. The Court found that in practice the

commissioners do not place on the jury roll all such citizens,

2. The Court found in People v. Craig (Alameda County Supe

rior Court, No. 41750, April 18, 1968) that 81.5% of the registered

voters of West Oakland, who are predominantly black and of low

economic income, failed the test while only 14.5% of the registered

voters of Montclair, who are predominantly white and of middle

or higher economic income, failed the test.

Appendix 13

either white or Negro. The Court referred to this jury selec

tion procedure and held (pp. 208-209):

Venires drawn from the jury box made up in this

manner unquestionably contained a smaller proportion

of the Negro community than of the white community.

But a defendant in a criminal case is not constitu

tionally entitled to demand a proportionate number of

Ms race on the jury which tries him nor on the venire

or jury roll from which petit jurors are drawn.. . .

There is no evidence that the commissioners applied

different standards of qualifications to the Negro com

munity than they did to the white community.. . . Un

doubtedly the selection of prospective jurors was some

what haphazard and little effort was made to ensure

that all groups in the community were fully repre

sented. But an imperfect system is not equivalent to

purposeful discrimination based on race.

Accord: Akins v. Texas, 325 U.S. 398 (1945); and Thomas

v. Texas, 212 U.S. 278 (1909).

The decision in Swain fairly controls the contentions here.

Petitioner does not have a constitutional right to have a

proportionate number of his race or economic class on the

jury or the master jury panel. Swain, supra at p. 208. The

test given to Negroes was exactly the same as that given

to others and it was administered and graded on equal

terms with respect to all persons. Although this test may

have been imperfect and resulted in excluding a dispropor

tionate number of Negroes and persons of low economic

income, this does not amount to purposeful discrimination

based on race or income.

Objective criteria were used to select the members of the

jury panel. The criteria were designed to test the intelli

gence of the prospective jurors. The Supreme Court of the

United States recently has given approval of such a test.

Carter v. Jury Commission, 396 U.S. 320 (1969); Turner v.

14 Appendix

United States, 396 U.S. 398 (1969). In Carter the District

Court refused to invalidate the Alabama law requiring the

jury commissioners to select for jury service those persons

who are “generally reputed to be honest and intelligent and

. . . esteemed in the community for their integrity, good

character and sound judgment. . . .” In affirming the judg

ment of the District Court, the Supreme Court said (pp.

332-333):

It has long been accepted that the Constitution does

not forbid the States to prescribe relevant qualifica

tions for their jurors, The States remain free to

confine the selection to citizens, to persons meeting

specified qualifications of age and educational attain

ment, and to those possessing good intelligence, sound

judgment, and fair character. “ Our duty to protect the

federal constitutional rights of all does not mean we

must or should impose on states our conception of the

proper source of. jury lists, so long as the source

reasonably reflects a cross-section of the population

suitable in character and intelligence for that civic

duty.”

Turner follows Carter in upholding the constitutionality

of the jury selection law which gives the jury commissioners

the right to eliminate from grand-jury service anyone they

find not “upright” and “ intelligent.” The distinguishing

feature of Turner vis-a-vis the instant case is contained in

the opinion of the court as follows (pp. 360-361):

In sum, the appellants demonstrated a substantial

disparity between the percentages of Negro residents

in the county as a whole and of Negroes on the newly

constituted jury list. They further demonstrated that

the disparity originated, at least in part, at the one

point in the selection process where the jury commis

sioners invoked their subjective judgment rather than

objective criteria. The appellants thereby made out a

prima facie case of jury discrimination, and the burden

fell on the appellees to overcome it.

Appendix 15

The testimony of the jury commissioners and the

superior court judge that they included or excluded

no one because of race did not suffice to overcome the

appellants’ prima facie case. So far the appellees have

offered no explanation for the overwhelming percen

tage of Negroes disqualified as not “upright” or “ in

telligent,” or for the failure to determine the eligibility

of a substantial segment of the county’s already regis

tered voters.

There is no showing in the instant case of purposeful

exclusion from jury service because of race. Negroes of low

economic income were treated in the same manner as whites

and members of other minority groups who are persons of

low economic income. Even though the use of the clear

thinking test may have resulted in a high proportion of

persons of petitioner’s racial and social background failing

the test, that is not adequate proof that persons of peti

tioner’s or any other race were purposefully excluded from

the master jury panel in Alameda County because of the

employment of the test, and it is not sufficient to demon

strate a violation of petitioner’s constitutional rights.

Petitioner’s Arrest and the Search and Seizure

Petitioner alleges that police officers searched him in the

course of an arrest which was unlawful because there was

no probable cause to make an arrest. The following facts

are either admitted or not controverted by petitioner.

Officer Alves and Agent Woishnis were aware of the fact

that petitioner had been arrested on previous occasions for

using narcotics, that he had been under an investigation

since 1964, and that he had been convicted of a felony in

1957. Officer Alves received a call at 2 :30 P.M. on January 7,

1966, from an anonymous caller who told him that petitioner

was known as “Black Richard” and that he was parked in

front of 1007-45th Street in Emeryville with “more nar-

16 Appendix

cotics than he [could] swallow.” The agent and officer pro

ceeded immediately to the area in two cars.

After they had “ staked-out” 1007-45th Street for two

hours, petitioner came out and walked toward a 1957 Cadil

lac sedan parked in front. Agent Woishnis had previously

observed petitioner in that vehicle. Petitioner opened the

car door and sat behind the wheel with the door ajar. He

then stepped out of the car and looked over the top toward

two other persons coming from the porch. Agent Woishnis,

communicating by radio, told Officer Alves that they should

now go and talk with petitioner. Agent Woishnis drove his

car and slowed it down for a stop as it passed petitioner.

As the car was slowing for a stop Agent Woishnis observed

petitioner pulling what appeared to be a pistol in a holster

from his waistband. Agent Woishnis immediately jumped

from his car and ran toward petitioner, and as he did he

saw petitioner put the pistol on the car seat.

Meanwhile, Officer Alves had parked his car and was

walking toward petitioner who was standing beside his car

talking with the persons on the porch. When Officer Alves

was about ten feet away, petitioner brought into view his

right hand holding an object which appeared to be a pistol

and a holster. Petitioner then made a movement as if to

throw something into the car.

Agent Woishnis placed petitioner under arrest and im

mediately “ patted him down.” In the left front pocket of

petitioner’s trousers Agent Woishnis found a balloon con

taining a powder which he believed to be heroin and that is

what it subsequently turned out to be. Officer Alves took

the loaded pistol and holster from the car.

At the trial Agent Verbrugge testified that about a month

prior to this arrest he conversed with petitioner concerning

a sale of heroin by petitioner.

Appendix 17

A police officer may in appropriate circumstances and

manner approach a person for purposes of investigating

suspected criminal behavior even though there is no prob

able cause to make an arrest. Terry v. Ohio, 392 U.S. 1,

22 (1968); Lowe v. United States, 407 F.2d 1391, 1394 (9th

Cir. 1969). The actions by Agent Woishnis and Officer Alves

in approaching petitioner in order to talk with him about

possible criminal behavior were lawful.

An arrest by officers can be supported by their reasonable

cause to believe that a felony was being committed in their

presence. Rios v. United States, 364 U.S. 253, 262 (1960);

Morales v. United States, 344 F.2d 846 (9th Cir. 1965). In

the present case petitioner was not arrested until the officers

had seen him place a pistol on the seat of his car. This

together with their knowledge that he had been convicted

of a felony was sufficient to justify the officers’ belief that a

felony was being committed in their presence.3 Conse

quently, the arrest of petitioner was lawful.

The search of petitioner’s person was lawful because it

was “ incident to a lawful arrest.” Harris v. United States,

331 U.S. 145 (1947); United States v. Rabinoivitz, 339 U.S.

56 (1950). The Court is of the opinion that Chimel v. Cali

fornia, 395 U.S. 752 (1969) is not applicable here,4 but even

if it were, the search of petitioner would be lawful because

it was in an area “within his immediate control” as defined

by that case.

3. Cal.Pen.Code § 12021 provides in part as follows:

Any person who is not a citizen of the United States and

any person who has been convicted of a. felony under the laws

of the United States, of the State of California, or any other

state, government-, or country . . . is guilty of a public

offense. . . .

4. The rule of Chimel does not apply to searches conducted

before June 23, 1968, the date of the Chimel decision. Heffley v.

Hocker, 420 F.2d 881 (9th Cir. 1969); William v. United States,

418 F.2d 159 (9th Cir. 1969).

18 Appendix

After arresting petitioner the officers seized the pistol

from the seat of the car and in the trunk of the car they

found a raincoat with a balloon containing milk sugar in

one of the pockets. The warrantless search and seizure of

this evidence is lawful under the circumstances because

there was probable cause and because the car could have

been removed quickly from the locality or jurisdiction in

which the warrant would have been sought, or the evidence

could have been removed from the car and destroyed ox-

concealed. Carroll v. United States, 267 U.S. 132, 153

(1925); Brinegar v. United States, 338 U.S. 160 (1949);

Call v. United States, 417 F.2d 462, 465-466 (9th Cir. 1969);

and Travis v. United States, 362 F.2d 477 (9th Cir. 1966).

Accordingly, it is hereby ordered as follows: the petition

for a writ of habeas corpus is denied; the order to show

cause is discharged and the proceeding is dismissed.

Dated: Jul 9 1970

/ s / Gerald S. L evin

United States District Judge

Appendix C

United States Court of Appeals

for the Ninth Circuit

Appendix 19

No. 26,236

Filed—May 10 1972,

Clerk

Richard L. Carmical,

Petitioner-Appellant,

VS.

Walter E. Craven, Warden,

California State Prison at Folsom,

Respondent-Appellee.

ORDER

Before: BARNES, HAMLEY and HUFSTEDLER,

Circuit Judges

All members of the court in active service, together with

the two senior judges who served on the original panel,

have considered the suggestion of a rehearing en banc. A

majority of said judges have voted against a rehearing en

banc. The votes of Chief Judge Chambers and of Judge

Wright in favor of rehearing en banc are recorded.

The petition for a rehearing is denied. The suggestion of

a rehearing en banc is rejected.

Appendix D

PENAL CODE SECTION 1060

Time for challenge to panel; method of making

WHEN AND HOW TAKEN. A challenge to the panel

must be taken before a juror is sworn, and must be in writ

ing or be noted by the Phonographic Reporter, and must

plainly and distinctly state the facts constituting the ground

of challenge.

CODE OF CIVIL PROCEDURE SECTION 198

Competency

A person is competent to act as juror if he be:

1. A citizen of the United States of the age of twenty-

one years who shall have been a resident of the state and of

the county or city and county for one year immediately

before being selected and returned;

2. In possession of his natural faculties and of ordinary

intelligence and not decrepit;

3. Possessed of sufficient knowledge of the English

language.

20 Appendix

Appendix 21

Appendix E

In the Superior Court of the State of California

In and for the County of Alameda

BEFORE THE HONORABLE

SPURGEON AVAKIAN, JUDGE

Filed—Apr 18 1968

Jack G. Blue, County Clerk

T. J. Chamberlin

Deputy

DEPARTMENT NO. 6

No. 41750

The People of the State of California,

Plaintiff,

vs.

Mark Twain Craig,

Defendant. * 1

MEMORANDUM DECISION ON CHALLENGE TO

JURY PANEL

By a timely challenge to the jury panel drawn for the

trial of his case, Defendant questions the whole process by

which trial jurors are selected in Alameda County. Four-

days of testimony were devoted to developing the factual

basis for the challenge.

The grounds of challenge consist essentially of the fol

lowing :

1. The jury selection process results in the dis

proportionate exclusion of identificable groups (specif

ically, racial minorities and lower income citizens) and

consequently produces a master panel which is not

representative of the community at large, in violation

of the clue process and equal protection clauses of the

Fourteenth Amendment;

2. The jury selection process departs from the

legislative pattern by eliminating persons who possess

“ ordinary intelligence,” particularly by use of a written

test which is not geared directly to the measurement of

“ ordinary intelligence” ;

3. The Jury Commissioner grants excuses from

jury service under oral instructions instead of under

written rules adopted by the Court under C.C.P. sec

tion 201a.

The master panel of trial jurors is compiled by the Jury

Commissioner for half-year periods at a time. The current

master panel was processed during the second half of 1967.

Tnit.ifl.11y, 6,336 names were selected at random from the

list of registered voters of the county. The selection was by

a formula designed to provide an equal number of men and

women, and a number from every precinct in the county

substantially proportionate to the number of voters regis

tered in such precinct. Notices were then sent to these per

sons to report at stated times for interview and inquiry into

qualifications. Such contact was actually made with 5,079

of the total group. The remaining 1,257 are accounted for as

22 Appendix

follows:

Letters returned by Post Office .............. 608

Failure to Respond to Notice .................. 175

Deceased ................................... —-....... - 79

Moved out of County.................. ......... ..... 395

1,257

From the 5,079 who were actually processed by the Jury

Commissioner, 1,659 were found to be qualified and not ex

cused. Service of 113 of these was deferred, at their request,

to a later period, and 1,546 were certified to, and approved

Appendix 23

by, the Court as the master panel for jury trials during the

first half of 1968. The men numbered 790, and the women,

756.

With respect to the number who were processed but

either excused or found not qualified, the total of 3,420 is

made up of the following groupings:

Poor health ...................................... 704

Occupational exemption................... 542

"Women with small children ......... ............. 454

Lack of understanding of English............ 112

Prior jury service ................................... 244

Poor hearing ....................... 125

Business and personal hardship ............. . 161

Travel ............................................. 17

Conviction of high crime ........................ 68

Lack of transportation ............................. 34

Mental instability .................................. 19

Failed written test ...... 940

3,420

As indicated below, the main thrust of the contention that

the master panel is not a fair cross-section of the popula

tion of the county is aimed at the written test. There is no

indication in the record of any racial or socio-economic

discrimination by the Jury Commissioner’s office in the

other categories of elimination listed above.

The statutory qualification for jury service, insofar as

the validity of the written test is concerned, is that jurors

be “ of ordinary intelligence” and “ possessed of sufficient

knowledge of the English language.” C.C.P. 198. No defini

tion of those terms is set forth in the statute, but the deci

sional law requires non-discriminatory selection from a

broad base of the community and forbids a so-called “blue

ribbon” approach. Thiel v. Southern Pacific Co., 328 U.S.

217 (1946). The use of written tests in applying this stand

ard is neither uniform nor unusual in this state.

24 Appendix

In Alameda County, the test currently in use was adopted

by the Court in 1956, after having been prepared by a

psychologist for this particular use. It consists of 25 mul